Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110946

Revised: July 6, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 161 Days and 18.4 Hours

Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH) is an increasingly recognized phenotype within the spectrum of drug-induced liver injury. Several drugs, including nitrofurantoin, minocycline, hydralazine, methyldopa and infliximab, have a well-documented capacity to induce DI-ALH. Distinguishing DI-ALH from classic de novo autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) can be challenging due to overlapping clinical, biochemical, and serological features. Accurate distinction from classic AIH is crucial, as management and prognosis differ. While some DI-ALH cases resolve spontaneously after drug withdrawal, others show persistent or worsening liver injury. Histological studies have shown that fibrosis and cirrhosis are more prevalent in classic AH. Unfortunately, there are no patho

Core Tip: Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis is a challenging issue in clinical practice. Although some parts of the puzzle have been put in place, there are still several events to be solved. These include the lack of a clear classification of the disease, the role of liver pathology and how treatment should be approached in terms of corticosteroid dosage, for how long it should be prescribed and when to stop therapy.

- Citation: Bessone F, Bjornsson ES. Autoimmune-like hepatitis induced by drugs: Still many unanswered questions. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 110946

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/110946.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110946

Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH) can be triggered by a broad range of agents, including prescription drugs, herbal supplements, and vaccines. Among these, several coronavirus diseases 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have been well-documented as potential inducers of autoimmune-like hepatitis[1]. DI-ALH shares overlapping features with classical autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), particularly in histological, biochemical, and serological profiles, mainly by the presence of autoantibodies and elevated serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels. Consequently, distinguishing between

However, recent studies suggest that some patients may be at risk of a relapse, indicating the potential need for long-term clinical follow-up[4,5]. A recent analysis from the Spanish/Latin American registries reported a 50% relapse rate at 4 years, in contrast with the absent or very low relapse rates described in most other studies, suggesting that this finding may represent an outlier. One plausible explanation is that some patients who relapse after treatment may, in fact, have had underlying classic AIH from the outset, with the implicated drug acting only as an innocent bystander. However, the follow-up period in the Spanish/Latin American registry study was longer than in many other DI-ALH studies, suggesting that relapse can indeed occur in this patient population over time.

Interestingly, the COVID-19 vaccine has been convincingly associated with the development of DI-ALH in several reports[6-8]. Furthermore, the administration of high doses of methylprednisolone has also been implicated as a potential trigger for DI-ALH[9,10].

Unfortunately, there are currently no reliable predictive markers to identify which patients will require corticosteroid therapy, nor are there clear guidelines regarding the optimal dosage or duration of treatment. The vast majority of patients with DI-ALH have a favorable prognosis; however, in some cases, patients have developed clinically acute liver failure (ALF), occasionally necessitating liver transplantation (LT)[11]. The aim of the present review is to examine the most recent literature on DI-ALH, following the publication of the consensus statement[1]. This review is intended to address the ongoing controversies and introduce emerging concepts that may contribute to a more effective management of this complex and heterogeneous patient population.

At a consensus meeting held in Nerja, near Málaga, Spain, experts in drug-induce liver injury (DILI) and AIH agreed upon a definition of DI-ALH. In this context, DI-ALH was defined as acute liver injury, induced by drug exposure, characterized by laboratory and histological features suggestive of autoimmunity[1]. It is, however, quite variable, some patients exhibit both autoantibodies - such as antinuclear antibody (ANA)/smooth muscle antibodies (SMA) along with elevated IgG levels, while others may present with only autoantibodies or isolated IgG elevation. In most well-documented cases, the latency period between drug exposure and onset of liver injury spans a few weeks. However, there are exceptions, for instance, nitrofurantoin, which has been reported to induce DI-ALH after more than a year of use[1]. The histological features observed in DI-ALH are not specific and often overlap with those seen in AIH, rendering histological distinction between the two conditions challenging[1-5,12]. In one of the initial studies describing DI-ALH, the histological grade and stage were found to be similar between patients with DI-ALH and those with AIH. However, none of the patients with DI-ALH had cirrhosis at baseline, in contrast to 20% of the AIH patients in whom cirrhosis was already present[2]. In a study published in 2022, a systematic analysis was conducted to identify drugs and herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) associated with well-documented cases that met the proposed criteria for DI-ALH[13]. In that study, the definition of DI-ALH was based on 5 criteria: (1) Evidence that the drug in question could act as a potential trigger of liver injury with autoimmune features, supported by both serological and histological findings consistent with AIH. This included elevation in any of the following: ANAs, SMAs and IgG, along with a liver biopsy compatible with AIH. Thus, the presence of either positive ANA/SMA/IgG or a compatible liver biopsy alone was not considered sufficient to meet the definition[1-3]. Implication of drugs known to potentially induce DI-ALH with a chronic disease course[13]; (2) Absence or incomplete recovery or worsening of liver function tests following discontinuation of the suspected drug; (3) Requirement of corticosteroid therapy to achieve spontaneous recovery. In some cases of spontaneous resolution, recovery was prolonged over several weeks, not contradicting the second criterion; (4) Absence of relapse during follow- up of at least 6 months after discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy; and (5) Exposure to drugs previously reported to induce DI-ALH with a prolonged or chronic disease course[13].

Prior to that systematic analysis, nitrofurantoin, minocycline, methyldopa, and infliximab had all been associated with well-documented cases of DI-ALH[2,3,14-17]. The most frequently reported agents implicated in DI-ALH were interferons, statins, methylprednisolone, adalimumab, imatinib, and diclofenac[13]. Interestingly, additional reports have been identified describing cases of methylprednisolone-induced DI-ALH[10], including convincing reports from Germany and Japan[9,18]. Among HDS, only Catha edulis and Tinospora cordifolia were found to be able to induce DI-AILH[13]. While a large number of other HDS have been associated with suspected cases of DI-ALH, these agents did not fulfill the established criteria[13].

Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors with convincing reports of association with DI-ALH were imatinib and pazopanib[13]. Furthermore, in addition to infliximab and adalimumab, other biologic agents that modulate the immune system - such as etanercept and efalizumab, have also been implicated in the development of DI-ALH[13]. However, infliximab remains by far the most frequently implicated immunomodulatory agent associated with the development of DI-ALH[3,15-17]. In a recent study based on data from the Spanish and the Latin American DILI registries, patients meeting the criteria for DI-ALH (n = 33) were identified. The most implicated agents were statins (24%), nitrofurantoin (15%), and minocycline (12%). In addition, a number of cases were associated with other drugs including cyproterone, ciprofloxacin, isotretinoin, dexketoprofen, ibuprofen, meloxicam, orlistat, irbesartan, infliximab, efalizumab, and herbalife products[4]. Surprisingly, two cases of DI-ALH were attributed to amoxicillin-clavulanate, a phenotype that, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported in association with the use of this agent. The relapse rate among patients diagnosed with DI-ALH was higher than previously reported, with the likelihood of relapse increased over time - from 17% at 6 months to 50% 4 years after biochemical normalization[4]. In line with earlier reports, statins were the most implicated drug class associated with relapse[13]. However, in contrast with previous studies, nitrofurantoin and minocycline were also associated with relapse following normalization of liver function tests[4], a finding not observed in the previously mentioned study conducted at the Mayo Clinic[2]. In the systematic analysis of DI-ALH, no relapses of AIH were observed following the discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy in cases associated with interferons, imatinib, diclofenac, or methylprednisolone[13]. In a recent study from England, a variety of drugs were implicated in patients with DI-ALH, with the most frequently reported being nitrofurantoin, tetracyclines, and amoxicillin. Notably, no cases were attributed to amoxicillin-clavulanate[19]. Furthermore, 4/28 cases (14%) were associated with anti- tumor necrosis factor α agents, specifically infliximab (n = 3)[19]. However, in the Spanish/Latin American DILI registry, only 1/33 cases (3%) were attributed to infliximab, but no other biologic agents were implicated[4]. The most frequent drugs associated with DI-ALH are shown in Table 1.

| Drug | Therapeutic indication | Association with DI-AIH |

| Minocycline | Acne vulgaris, rosacea | Frequently reported in young females |

| Nitrofurantoin | Recurrent UTIs | Often presents with ANA and ASMA positivity |

| Methyldopa | Hypertension (especially in pregnancy) | Classical example of DI-AIH |

| Hydralazine | Hypertension, heart failure | Can induce lupus-like syndrome and DI-AIH |

| Statins (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin) | Hyperlipidemia | Increasingly reported; often presents with mild phenotype |

| Infliximab | Rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis | Anti-TNFα-induced AIH described in several cases |

| Adalimumab | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, ulcerative colitis | Rare, but documented in literature |

| Interferon-α | Chronic hepatitis B/C, certain cancers | May trigger or unmask autoimmune hepatitis |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., imatinib) | CML, GIST | Rare cases reported |

The proportion of patients with AIH and DILI who present with either drug-induced AIH or DILI with autoimmune features has not extensively studied. However, in a well-defined cohort of patients with AIH at the Mayo Clinic, 24/261 cases (9.2%) had DI-ALH, almost exclusively attributed to two drugs, nitrofurantoin and minocycline[2]. In a study conducted by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) in the United States, the prevalence of DILI cases with autoimmune features-most associated with nitrofurantoin, minocycline, methyldopa, and hydralazine, was 6.7%[14]. In contrast, data from the Spanish and the Latin America DILI registries indicated a lower frequency of DI-ALH, at only 2.3%. Similarly, in the prospective European DILI study (Pro-Euro-DILI), 4.2% of cases exhibited features consistent with DI-ALH[20], a rate comparable to that observed in the DILIN cohort[14].

Drugs that have convincingly been shown to cause DI-ALH can be classified into two categories: (1) Agents that interfere with the immune system; and (2) Other drugs, with a diverse pharmacological property. Category A includes immunomodulatory agents such as interferons, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, efalizumab, imatinib, masitinib, pazopanib, methylprednisolone, and COVID-19 vaccines[1,13]. Category B comprises drugs associated with DI-ALH, including statins, diclofenac, and HDS[13]. Examples of well-documented HDS that have been shown to induce DI-ALH are Khat (Catha edulis) and Tinospora cordifolia, marketed under various names or brands, most commonly as Giloy[13].

In early studies on DI-ALH, based on well-characterized cases identified among patients with AIH[2] and DILI[14], a marked female predominance was observed, with 92% and 91% of cases occurring in women, respectively[2,14]. Among patients with methylprednisolone- induced DI-ALH, a systematic analysis of four studies reported a striking female predominance, with 94% of cases occurring in women[13]. Similarly, a recent study from Greece found that 12/13 patients (92%) were female[10]. Furthermore, a strong female predominance was also observed in DI-ALH cases associated with (86%) and with biologic agents such as adalimumab, etanercept, and efalizumab (93%)[13]. In contrast, the female predominance was less pronounced - approximately 70% - in cases linked to statins and diclofenac[13]. Interestingly, in a recent study of infliximab-induced liver injury 28 of the affected patients (78%) were females, although they accounted for only 49% of those treated with infliximab during the study period[3]. In contrast, only 58% were female, among DILI patients with autoimmune features in the Spanish and Latin America DILI registries[4]. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear; however, it may reflect the greater heterogeneity of that cohort[4] as not all drugs included had been previously associated with DI-ALH in earlier studies. In a recent study from England, 76% of patients with DI-ALH were female compared to 74% of patients with AIH[19]. These findings are consistent with previously published data, in which female predominates across most DI-ALH studies and for most implicated drugs.

Demographic characteristics, clinical features, autoimmune markers, and laboratory parameters were comparable between patients with DI-ALH and those with AIH with non-drug-related etiology[2]. The only difference observed between the two groups was the absence of relapse among all DI-ALH patients following withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy, whereas relapse was commonly observed in the classic AIH group[2].

In the DILIN cohort, among patients with DILI attributed to nitrofurantoin, minocycline, methyldopa, and hydralazine, 72% exhibited autoimmune features[14]. No significant differences were observed between patients with or without the autoimmune features in terms of sex, age, race, body mass index, clinical presentation, liver biochemistry, or disease severity[14]. However, latency to onset was longer in patients with the autoimmune features compared to those without, particularly in cases of minocycline- and nitrofurantoin-induced DI-ALH[14]. This was also observed in the Spanish/Latin American cohort, where the duration of treatment with the implicated agent was more prolonged in DI-ALH patients than in other DILI cases[4]. In the Mayo clinic cohort, similar proportions of DI-ALH and AIH patients presented with jaundice, a finding also observed in the DILIN study when comparing DI-ALH to other DILI patients[14]. However, more recent studies have reported conflicting findings. In one study, patients with DILI lacking autoimmune features were more likely to present with jaundice (66%) than those with DI-ALH (58%)[4], whereas in the United Kingdom cohort, jaundice was significantly more common among DI-ALH patients[20]. Thus, these discrepancies may be attributed to differences in cohort composition, particularly the heterogeneity in terms of the number and types of drugs implicated in the DI-ALH across studies.

The clinical, biochemical, and immunological features of DI-ALH appear to be more closely associated with the distinct signature of individual drugs such as nitrofurantoin, minocycline, methylprednisolone, or infliximab[2,3,13,14] rather than with broader drug categories defined by their association with autoimmune-like features[4,19]. The same likely applies to the risk of relapse, which appears to be more dependent on the specific drug involved rather than the broader diagnostic category of “DI-ALH”. As mentioned above, no relapses of AIH were observed after the withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy in patients who develop DI-ALH following treatment with interferons, imatinib, diclofenac, or methylprednisolone[13]. Moreover, infliximab-induced ALH has not been associated with relapses following normalization of liver function tests, according to the current literature[3].

Relapse after the normalization of liver function tests has been rarely reported in cases of nitrofurantoin- and minocycline-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis, with no relapses documented in two published studies[2,19]. However, in the Spanish/Latin American study, a relapse was reported in one case of each minocycline- and nitrofurantoin-induced DI-ALH, occurring after 4 years and 7 years of remission, respectively[4]. This finding is clinically relevant, as it underscores the need for prolonged follow-up in these patients, or at least, informing them that relapse remains a theoretical possibility.

Several proposed mechanisms contributing to the development of DI-ALH are outlined below[1,3,5]: (1) The hapten hypothesis suggests that reactive drugs or their metabolites covalently bind (“haptenate”) to hepatocyte proteins, resulting in the formation of neo-antigens that are subsequently presented on Major Histocompatibility Complex molecules. This process triggers a T cell-mediated immune response directed against the modified self-proteins; (2) The danger hypothesis, also referred to as the bystander hypothesis, posits that drug-induced hepatocyte stress or injury leads to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns. These molecules activate antigen-presenting cells and lower the threshold for the activation of autoreactive T cells against native hepatocyte antigens; (3) The concepts of molecular mimicry and heterologous immunity refer to structural similarities between a drug or its metabolite and a self-antigen, which may lead to cross-reactive immune responses. The immune system may initially target the drug, but the response can subsequently spread to recognize and attack native hepatocyte epitopes; (4) Neo-antigen formation and CD8+ T cell activation occurs when reactive drug metabolites covalently bind to phase I/II metabolic enzymes (e.g., cytochrome p-450) on the hepatocyte surface. This modification produces neo-antigens that elicit CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxic responses, often accompanied by the production of autoantibodies; (5) Genetic predisposition, particularly human leucocyte antigen (HLA) associations, has been implicated in DI-ALH. Certain HLA alleles (e.g., DRB103, DRB104, A3, and B8) may present drug-derived peptides more efficiently, thereby predisposing carriers to the development of DI-ALH following exposure to specific agents such as nitrofurantoin or minocycline; (6) Epigenetic dysregulation may arise when drugs or their metabolites induce DNA demethylation or histone modifications in immune regulatory genes. These changes can impair immune tolerance and promote autoimmune responses directed against hepatocytes; and (7) Cytokine imbalance and Th17/Treg dysregulation represent another proposed mechanism, whereby certain drugs may shift the immune balance toward pro-inflammatory Th17 responses or impair the function of regulatory T cells, thereby promoting autoimmunity within the hepatic microenvironment.

It has also been proposed that DI-ALH likely arises from a combination of drug-driven neoantigen formation or cell injury that exposes hepatic autoantigens and a permissive immune environment shaped by the gut-liver axis. Gut dysbiosis increased intestinal permeability, altered microbial metabolites (bile acids, short-chain fatty acids), and translocation of microbial products (lipopolysaccharides, bacterial DNA) amplify hepatic innate immune activation (Kupffer cells, dendritic cells) and bias adaptive responses toward autoreactivity (loss of tolerance, altered regulatory T cells/follicular helper T cells balance), promoting an autoimmune-like hepatic injury when a drug provides the initiating antigenic/inflammatory trigger[21].

It is likely that DI-ALH results from a combination of these mechanisms. Future research aimed at identifying reliable biomarkers may provide valuable opportunities to predict susceptibility and prevent this form of liver injury.

As previously discussed, liver histology lacks distinctive features that reliably differentiate classic AIH and DI-ALH. Although several studies have failed to reach definitive conclusions, some pieces of the puzzle seem to be falling into place. In line with this concept, the pioneering study by Björnsson et al[2] reported an absence of fibrosis and cirrhosis in cases of DI-ALH vs a 20% prevalence among patients who developed classic AIH. However, a subsequent small-scale study[12] found comparable degrees of fibrosis between AIH and DI-ALH. Notably, another investigation[22] observed a higher prevalence of advanced fibrosis in liver biopsies from DI-ALH patients, a finding consistent with the earlier observations reported by the Mayo Clinic group[2].

Interesting results were also recently published by Alkashash et al[23], who analyzed 15 Liver biopsies assessed by two blinded pathologists unaware of clinical parameters, focusing on final diagnoses and outcomes. Pathologists evaluated portal tract inflammation, interface hepatitis, lobular inflammation, central perivenular inflammation, central vein endothelitis, and central perivenular necrosis, using a semi-quantitative scoring system ranging from 0 to 3, corresponding to none, mild, moderate, or severe involvement. Classic AIH exhibited greater portal, interface, and central perivenular inflammation, as well as a higher prevalence of plasma cells compared to DI-ALH (all P < 0.05). All nine cases of classic AIH demonstrated moderate to severe interface hepatitis, whereas this pattern was observed in only one case of DI-ALH. Eosinophils were observed in both classical AIH and DI-ALH. Among the cases of classic AIH cases, four showed no fibrosis, three exhibited portal/periportal fibrosis, and two demonstrated bridging fibrosis. In contrast, two cases of DI-ALH revealed bridging fibrosis, while one case showed extensive perisinusoidal fibrosis[22]. However, the presence or absence of fibrosis was not statistically significant between the groups.

These authors did not clarify how DI-ALH was defined within their database, nor did they specify which medications were suspected of triggering this phenotype. It is plausible that DI-ALH does not represent a single entity and that the histopathological features may vary depending on the causative agent. For instance, patients with nitrofurantoin-induced autoimmune liver disease exhibited significantly higher necroinflammatory activity, more prominent interface and lobular hepatitis, and a greater prevalence of rosette formation compared to those with minocycline-induced DI-ALH[24].

Codoni et al[25] collected case data from 18 countries on liver lesions occurring after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination. The most frequent histological pattern was lobular hepatitis, observed in 76% of cases (45/59 patients). Portal hepatitis was identified at 17%, while cholestatic and steatohepatitis patterns were observed in the remaining 7%. Interface activity - defined as periportal inflammation involving hepatocytes of the limiting plate - was observed in both lobular and portal hepatitis cases. Severe interface activity was more common in patients with advanced fibrosis (Ishak stage ≥ 3). Necrosis and confluent necrosis, characterized by extensive hepatocyte death, was observed in 84% of lobular hepatitis cases and in 30% of portal hepatitis cases. Severe lobular necroinflammation (grade 4) was identified in 31% of lobular hepatitis cases, whereas none of the portal hepatitis cases exhibited this severity. Most patients had minimal or no fibrosis. However, advanced fibrosis (Ishak ≥ 3) was identified in 7% of lobular hepatitis and in 30% of portal hepatitis cases. Plasma cell aggregates were present in 62% of lobular hepatitis cases, while portal hepatitis was observed in 80% of cases. Eosinophils were detected in 40% of lobular hepatitis cases and in 50% of portal hepatitis cases. These histological features resemble those of classic AIH, which is typically characterized by prominent lobular inflammation and interface hepatitis associated with plasma cell-rich infiltrates and varying degrees of liver fibrosis. In addition, these findings also support the hypothesis of an immune-mediated mechanism possibly triggered by the vaccine in susceptible individuals. In the systematic analysis by Efe et al[8] this seemed to occur with different types of vaccines. Of the reported cases, 59% were attributed to the Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccine, 23% to the AstraZeneca (ChAdOX1 nCoV-19) vaccine and 18% cases to the Moderna (mRNA-1273) vaccine[7].

It remains unclear whether these cases represent true AIH, a vaccine-induced variant of AIH, or a self-limited immune-mediated reaction[24]. However, most reported cases of COVID vaccine-induced ALH, have not experienced relapse following discontinuation of vaccination[7]. In a collaborative study involving the LATINDILI network and the Spanish Registry of Hepatotoxicity, liver biopsies were performed in seven out of 23 female patients, aged 20 years to 70 years, diagnosed with nitrofurantoin-induced DI-ALH[26]. Two patients presented with asymptomatic hypertransaminasemia, whereas the remaining five exhibited with jaundice, indicative of overt liver disease.

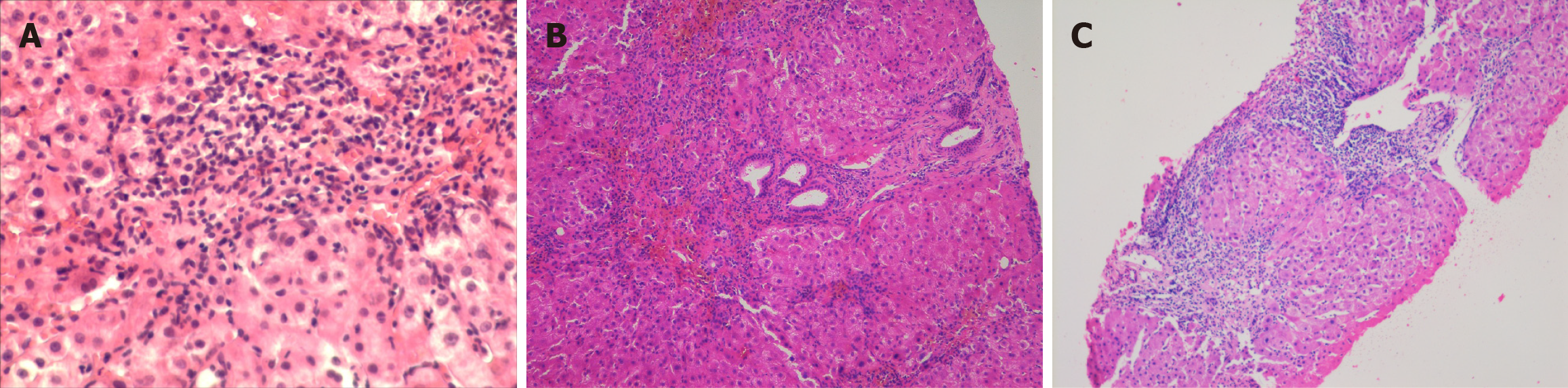

Histological examination revealed that four patients exhibited interface hepatitis accompanied by lymphocytic infiltration while three of them demonstrated advanced fibrosis. Notably, within the two asymptomatic patients, only inflammatory changes without evidence of fibrosis were observed in one of them, whereas portal-portal bridging fibrosis with a tendency toward cirrhotic nodularity was documented in the remaining case. These findings underscore the variability in histopathological presentations among patients with DI-ALH, highlighting the importance of liver biopsy in assessing disease severity. Reinforcing this concept we describe here three different histological patterns, two of which demonstrated varying degrees of hepatic fibrosis. While in Figure 1A an intense interphase hepatitis was observed, advanced fibrosis is described in Figure 1B, whereas features consistent with active cirrhosis were documented in the remaining case (Figure 1C). The histological patterns observed in these three cases reinforce the concept of the broad spectrum of hepatocellular injury that may be exhibited by these patients. Patterns of liver injury can range from mild piecemeal necrosis to an unusual picture of active cirrhosis with a tendency toward parenchymal nodulation, likely related to a long-standing disease.

Several authors have studied the cellular composition of liver biopsies to identify distinguishing histological features between classic AIH and DI-ALH (Table 2).

| Ref. | Design and cohort | Main histological findings |

| Chung et al[19], 2024 | Retrospective cohort; 28 DI-ALH vs 39 idiopathic AIH cases | DI-ALH exhibited significantly fewer plasma cell aggregates (61% vs 97%, P < 0.001), more eosinophilic aggregates (18% vs 3%), and lower portal inflammation and fibrosis (mean Ishak 1.9 vs 3.5) |

| de Boer et al[14], 2017 | Immunohistochemical profiling of autoimmune-DILI, idiopathic AIH, viral hepatitis | Infiltrates were predominantly CD8+ T cells across all groups. Idiopathic AIH showed significantly more CD20+ B cells and plasma cells compared to DILI-AILH, which had fewer of both |

| Tsutsui et al[27], 2020 | Comparative clinicopathological study: Acute AIH vs DILI (Japan) | Acute AIH demonstrated greater lobular necrosis, hepatocellular rosettes, and dense plasma-cell infiltrates than DILI (all P < 0.01), supporting these as discriminating features |

| Suzuki et al[12], 2011 | Histological scoring (DDWJ 2004) in AIH vs DILI | AIH scored significantly higher for portal inflammation, interface hepatitis, and plasma-cell infiltration than DILI (P < 0.012), confirming DDW-J scale’s diagnostic value. DI-ALH often showed portal-lobular inflammation |

| Björnsson et al[13], 2022 | Systematic review of 186 DI-ALH case reports | DI-ALH often shows portal-lobular lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, hepatocyte rosettes, and focal necrosis, mirroring AIH histology |

Chung et al[19] retrospectively compared 28 patients with DI-ALH to 39 patients with idiopathic AIH using updated histological criteria. They observed that DI-ALH was associated with a higher frequency of eosinophilic aggregates (18% vs 3%) and a significantly lower prevalence of plasma cell aggregates (61% vs 97%; P < 0.001). Portal inflammation and fibrosis (Ishak score) were significantly less severe in DI-ALH compared to idiopathic AIH (mean fibrosis 1.9 vs 3.5;

Interesting findings were reported by de Boer et al[14], who conducted immunohistochemical profiling of liver biopsies from patients with DILI with autoimmune features, classic AIH, and viral hepatitis. While CD8+ T cells constituted the predominant infiltrating population across all groups, CD20+ B cells and plasma cell infiltrates were significantly more prevalent in classic AIH compared to DILI with autoimmune features and were rarely observed intrinsic DILI. These authors concluded that the presence of plasma cells and B cells may serve as useful markers to differentiate idiopathic AIH from DI-ALH.

In contrast, Tsutsui et al[27] identified ten key histological features that differentiate acute-onset classic AIH from DI-ALH. Acute AIH was more frequently characterized by lobular necrosis, hepatocellular rosettes, and prominent plasma cell infiltrates compared to DI-ALH (P < 0.01). These findings support the use of these morphological features - especially hepatocellular rosettes and plasmacytosis - as valuable markers for distinguishing idiopathic AIH from drug-related autoimmune liver injury.

Suzuki et al[12] applied the Japanese Digestive Disease Week 2004 scoring system from Japan differentiate AIH from DI-ALH[12]. They reported significantly higher scores in AIH for portal inflammation, interface hepatitis, and plasma cell infiltration (P < 0.012), thereby validating the scoring system’s diagnostic utility. These histological features were underscored as key discriminators in distinguishing AIH from DI-ALH.

Conversely, Björnsson et al[2] analyzed 186 published case reports of DI-ALH to establish diagnostic criteria. They highlighted frequent portal-lobular lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, hepatocyte rosette formation, and focal necrosis as key histopathological features of DI-ALH. This study reinforces the fact that severe inflammatory patterns in DI-ALH can mirror classic AIH histology.

Both DI-ALH and classic AIH exhibit similar patterns of interface hepatitis and plasma-cell infiltration. However, cases reported in Asian populations - particularly those associated with herbal agents - tend to present with more acute or cholestatic features, likely reflecting regional differences in the types of compounds implicated.

The expert meeting hold in Nerja (Spain) reinforced the value of liver biopsy in future studies, particularly using immunohistochemical and molecular techniques. Also incorporating immune cell phenotyping may further aid in identifying immunohistochemical markers useful for the diagnosis of DI-ALH. A well-designed biopsy-based study, along with the identification of novel molecular markers, could provide greater clarity in distinguishing DI-ALH from AIH[1].

In summary, case series and reports describe variable histological features as typical autoimmune features: Interface hepatitis, portal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, and hepatocyte rosettes. Regarding fibrosis patterns, some patients already present with bridging fibrosis or even cirrhosis at diagnosis, especially in long-term nitrofurantoin users. Overlap features described lobular hepatitis, cholestatic injury and granulomas.

The pathological heterogeneity of DI-ALH is acknowledged but poorly studied. Especially in nitrofurantoin-associated cases, the presence of advanced fibrosis (bridging fibrosis, cirrhosis) at diagnosis raises the possibility of a drug-triggered chronic AIH rather than a purely reversible injury[2]. The absence of subgroup analyses in published cohorts limits our ability to differentiate these phenotypes and to predict prognosis or treatment needs.

Further research involving large, well-defined cohort of patients - using rigorous diagnostic criteria and longitudinal follow-ups is warranted. In the near future, omics-based approaches are expected to play a pivotal role by enabling the identification of drug-specific associations with DI-ALH, offering a promising avenue for advancing understanding and improving diagnostic accuracy.

To date, no randomized controlled trials have directly compared corticosteroid dosing or treatment duration between classic AIH and DI-ALH. However, several observational studies and expert consensus guidelines offer valuable insights into the management of these conditions. Unlike classic AIH, which typically requires long-term immunosuppressive therapy, DI-ALH may sometimes resolve completely once the offending agent is withdrawn. As mentioned above, the optimal corticosteroid dosage and treatment duration remain subjects of ongoing debate.

According to the LiverTox database, short-term corticosteroid therapy is recommended when liver enzymes fail to improve, within 1-2 weeks following drug withdrawal. Prednisone at doses of 20-60 mg/day may be initiated, with discontinuation advised once liver enzyme levels normalize[28]. In some cases, the drug may act as a trigger rather than the direct cause of AIH, leading to a self-sustaining immune response, requiring long-term immunosuppressive therapy. Once improvement occurs, corticosteroids should be gradually tapered, aiming for discontinuation within 3-6 months. A follow-up period of at least six months after therapy cessation is recommended to monitor for potential relapse[28].

Intermediate-term therapy (approximately 6 months) has been reported in cases of liraglutided-induced DI-ALH, with clinical and biochemical resolution observed between 3 months and 8 months[29]. Therefore, therapy may need to be continued for at least 6 months beyond the normalization of clinical and laboratory parameters (Table 3)[29]. With respect to long-term therapy exceeding 6 months, Ueno et al[30] examined the outcomes of patients with DI-ALH treated with pulse corticosteroid therapy. While specific duration of corticosteroid therapy was not specified, the study emphasized the importance of ongoing follow-up and monitoring for relapses. These findings suggest that a subset of patients may require extended immunosuppressive therapy beyond 6 months[30].

| Parameter | Classic AIH | DI-ALH |

| Initial steroid dose | Prednisone 30-60 mg/day (or equivalent) | Prednisone 20-40 mg/day (or equivalent) |

| Induction strategy | Often combined with azathioprine | Monotherapy with steroids usually sufficient |

| Tapering schedule | Gradual taper over months based on biochemical response | Faster taper once liver enzymes normalize |

| Duration of treatment | Long-term (often > 2 years, sometimes lifelong) | Short-term (typically < 6-12 months) |

| Need for maintenance therapy | Common (azathioprine or other immunosuppressants) | Rare; usually not required after resolution |

| Relapse after withdrawal | Frequent (up to 50%-80%) | Rare |

| Histologic recovery | Slower, often incomplete even after biochemical remission | Usually complete. Once drug is withdrawn inflammation resolves |

| Outcome/prognosis | Good with treatment, but risk of chronic disease or cirrhosis | Excellent prognosis; usually resolves without chronic sequelae |

| Lifelong monitoring needed | Yes | Case by case assessment |

Martínez-Casas et al[31] conducted a retrospective study comparing 178 patients with classic AIH to 12 patients with DI-ALH. Patients with DI-ALH achieved biochemical remission significantly faster (median: 2 months) than those with classic AIH (median: 17 months). No relapses were observed in the DI-ALH group, whereas the classic AIH group had a relapse rate of 18%[31]. Only 8.3% of DI-ALH patients required ongoing immunosuppressive therapy, compared to 66% in the classic AIH cohort[31].

Similar findings were reported by Björnsson et al[3] in 9 out of 18 patients with infliximab-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis-induced. All patients demonstrated a favorable biochemical response to immunosuppressive therapy, with normalization of aminotransferase levels achieved after a mean of 154 days (range: 80-300 days). Corticosteroids were successfully discontinued in all cases, and no biochemical relapses were observed during a median follow-up period of approximately 4 years (range: 0.5-6.0 years)[16].

Recent expert recommendations emphasize that DI-ALH should be included in the differential diagnosis of AIH, and prompt withdrawal of the suspected offending agent is crucial. Glucocorticoid therapy should be initiated in DI-ALH cases presenting severe symptoms, such as jaundice, or if there is no clinical or biochemical improvement following the discontinuation of the causative agent[1]. A short course of corticosteroid therapy - typically spanning a few months - may be appropriate in cases where aminotransferase abnormalities persist or progressively worsen despite withdrawal of the offending agent. The optimal timing for initiating corticosteroid therapy remains uncertain and is currently based on clinical judgement. Corticosteroids can also be utilized when a rapid biochemical response is needed, particularly to allow timely substitution of the causative drug with an alternative therapy.

A biochemical flare following glucocorticoid withdrawal may indicate underlying AIH, indicating the need for continued immunosuppressive therapy[1]. However, clinicians should remain aware that certain chronic forms of drug-induced hepatitis, especially those with marked autoimmune features, may also relapse following the withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy. The patient should be informed about probability of a relapse and told to keep in contact if symptoms of AIH might occur. Also, in selected cases based on clinical judgment, long-term monitoring with liver tests might be advisable for several years after discontinuation of corticosteroid treatment.

The current body of evidence on DI-ALH is constrained by significant methodological limitations. Most of the available data derive from isolated case reports and small retrospective case series, which represent the lowest tiers of the evidence hierarchy. These publications often lack standardized diagnostic criteria, uniform follow-up protocols, and appropriate control groups, thereby limiting their generalizability and weakening the strength of the inferences that can be drawn. Critically, the absence of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials precludes definitive conclusions regarding causality, disease progression, relapse risk, and optimal management strategies. Moreover, heterogeneity in diagnostic approaches and the predominantly retrospective design of available reports further contribute to variability in case definitions and outcome assessments.

The prognosis of DI-ALH is generally favorable, especially when the causative agent is promptly identified and discontinued. Although clinical presentation can range from mild to severe, most cases are mild to moderate in severity[32]. Compared to classic AIH, DI-ALH carries a lower risk of progression to cirrhosis and a higher likelihood of achieving complete remission without the need for prolonged immunosuppressive therapy[13,32]. In addition, DI-ALH can be associated with potentially fatal outcomes including ALF and the need for LT as has been previously reported[11].

In a population-based study among patients with infliximab-induced DILI, jaundice was present in only 11% of cases[3]. Liver injury was categorized as mild in 75% and moderate in 25% of patients[3]. Approximately 50% required corticosteroid therapy, but no cases progressed to liver failure, and no fatalities were reported[3]. Consistent with these findings, among 458 patients enrolled in the LATINDILI registry, only nine cases (2%) met the diagnostic criteria for DI-ALH[33]. Of these, six were classified as moderate and three as mild in severity. No severe presentations or cases of ALF were identified. During a median follow-up period of 60 months, only one patient experienced a relapse[33]. All these results suggest that ALF is a rare clinical manifestation of DI-ALH at presentation.

In contrast, a single-center study from England involving 28 patients with DI-ALH and 39 with classic AIH reported that LT was required in four patients across both cohorts[19]. However, the time from diagnosis to LT was significantly shorter in those with DI-ALH compared to the classic AIH group (35 days vs 1424 days, P = 0.03). The four DI-ALH patients who underwent LT presented with significantly higher serum bilirubin levels (406 μmol/L vs 160 μmol/L,

In line with these findings, Bessone and Björnsson[11] compiled nine well-documented cases of infliximab-induced DI-ALH that required LT. Interestingly, Hisamochi et al[34] reported a Japanese cohort of 23 DI-ALH cases, most of them associated with herbal or traditional medicines. Patients typically presented with acute disease characterized by prominent cholestatic features and moderate autoantibody expression (IgG/ANA), suggesting more severe jaundice at presentation with lower levels of autoimmune serology compared to Western cohorts[34].

In summary, the long-term prognosis of DI-ALH is generally favorable, with reported survival rates ranging from 90% to 100% and a low incidence of ALF and LT. This contrasts with classic AIH, which is characterized by a high relapse rate following therapy discontinuation and a substantial risk of progression to cirrhosis, particularly if treatment is delayed. In some cases, this can lead to ALF, often necessitating LT. However, in rare instances DI-ALH can be associated with liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and ALF but also we have to keep in mind that relapses can rarely occur after stopping immunosuppressive therapy.

The lack of rechallenge evidence means that DI-ALH rests on circumstantial, retrospective-level evidence, not on causal proof. This is a key limitation and explains why the entity is still debated: In many cases, what we call DI-ALH may be drug-triggered AIH rather than purely drug-induced autoimmunity.

Certain limitations arise from the reliance on retrospective studies, including variability in the definitions of DI-ALH and inconsistencies in inclusion and exclusion criteria across studies. Although long-term follow-up in DI-ALH has been emphasized because of the potential risk of relapse, specific post-withdrawal monitoring protocols remain poorly standardized. Drawing on existing clinical experience with DI-ALH, we propose a pragmatic follow-up strategy that includes extended monitoring of liver function tests for up to 5 years after normalization of biochemical parameters following corticosteroid withdrawal.

Future research in this field should focus on several priority areas. First, there is a need for more precise phenotypic characterization and the development of standardized diagnostic criteria, including the harmonization of definitions for drug-induced AIH, AIH unmasked by drugs, and autoimmune-like DILI. Regarding liver pathology, advances will require more detailed and systematic histological subgrouping.

Second, efforts toward biomarker development should encompass immunogenetic markers such as HLA genotyping (e.g., HLA-DRB1 alleles) to help differentiate DI-ALH from idiopathic AIH. Additional promising approaches include serological and cytokine profiling to identify immune signatures capable of distinguishing transient drug-induced reactions from self-sustaining AIH, as well as microbiome and metabolomic profiling to elucidate the role of the gut-liver axis in susceptibility to autoimmune-like drug responses.

Third, research should emphasize mechanistic pathways of liver injury. This includes the use of animal models, specifically drug exposure in genetically susceptible backgrounds to reproduce DI-ALH phenotypes. Moreover, systems immunology approaches - such as single-cell transcriptomics and T cell receptor and B cell receptor repertoire analysis - are needed to characterize mechanisms of tolerance breakdown. Finally, integration of the gut microbiome-liver axis into experimental frameworks will be critical to understanding the complex interplay between environmental triggers, host genetics, and immune dysregulation.

Finally, and regarding long-term outcomes and relapse risk, controlled trials are needed, since current management is largely anecdotal. Establish longitudinal registries to clarify whether DI-ALH patients are at risk of chronic AIH, relapse after steroid withdrawal, or long-term progression to cirrhosis.

DI-ALH is a distinct clinical entity that mimics idiopathic AIH but is precipitated by specific drugs, HDS or vaccines. A thorough drug history is essential for diagnosis, as it represents the main differentiating factor from classic AIH. Early recognition and withdrawal of the offending agent are critical to prevent disease progression and minimize the need for long-term immunosuppression. Liver biopsy and autoantibody testing can support the diagnosis but are insufficient to distinguish DI-ALH from idiopathic AIH on their own. Most patients experience favorable outcomes, with low relapse rates when the trigger is removed and appropriate treatment is administered. Long-term immunosuppression is rarely required, particularly when complete resolution occurs after drug discontinuation. Although no consensus exists, several studies suggest that short-term immunosuppression, typically for no longer than 6 months, may be sufficient to induce remission with a low risk of relapse. Nevertheless, clinical vigilance remains essential, as late relapses have been reported.

We would like to thank Dr Merecedes Cortese for her assistence with this manuscript.

| 1. | Andrade RJ, Aithal GP, de Boer YS, Liberal R, Gerbes A, Regev A, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Schramm C, Kleiner DE, De Martin E, Kullak-Ublick GA, Stirnimann G, Devarbhavi H, Vierling JM, Manns MP, Sebode M, Londoño MC, Avigan M, Robles-Diaz M, García-Cortes M, Atallah E, Heneghan M, Chalasani N, Trivedi PJ, Hayashi PH, Taubert R, Fontana RJ, Weber S, Oo YH, Zen Y, Licata A, Lucena MI, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Björnsson ES; IAIHG and EASL DHILI Consortium. Nomenclature, diagnosis and management of drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH): An expert opinion meeting report. J Hepatol. 2023;79:853-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, Neuhauser M, Lindor K. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2040-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Björnsson HK, Gudbjornsson B, Björnsson ES. Infliximab-induced liver injury: Clinical phenotypes, autoimmunity and the role of corticosteroid treatment. J Hepatol. 2022;76:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | García-Cortés M, Ortega-Alonso A, Matilla-Cabello G, Medina-Cáliz I, Castiella A, Conde I, Bonilla-Toyos E, Pinazo-Bandera J, Hernández N, Tagle M, Nunes V, Parana R, Bessone F, Kaplowitz N, Lucena MI, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Robles-Díaz M, Andrade RJ. Clinical presentation, causative drugs and outcome of patients with autoimmune features in two prospective DILI registries. Liver Int. 2023;43:1749-1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Weber S, Gerbes AL. Relapse and Need for Extended Immunosuppression: Novel Features of Drug-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis. Digestion. 2023;104:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bril F, Al Diffalha S, Dean M, Fettig DM. Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine: Causality or casualty? J Hepatol. 2021;75:222-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ansari N, Shokri S, Pirhadi M, Abbaszadeh S, Manouchehri A. Epidemiological Study of COVID-19 in Iran and the World: A Review Study. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2022;22:30-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Efe C, Uzun S, Matter MS, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B. Autoimmune-Like Hepatitis Related to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Towards a Clearer Definition. Liver Int. 2025;45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carrier P, Godet B, Crepin S, Magy L, Debette-Gratien M, Pillegand B, Jacques J, Sautereau D, Vidal E, Labrousse F, Gondran G, Loustaud-Ratti V. Acute liver toxicity due to methylprednisolone: consider this diagnosis in the context of autoimmunity. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:100-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kounatidis D, Vallianou NG, Kontos G, Kranidioti H, Papadopoulos N, Panagiotopoulos A, Dimitriou K, Papadimitropoulos V, Deutsch M, Manolakopoulos S, Vassilopoulos D, Koskinas J. Liver Injury Following Intravenous Methylprednisolone Pulse Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis: The Experience from a Single Academic Liver Center. Biomolecules. 2025;15:437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bessone F, Björnsson ES. Drug-Induced Liver Injury due to Biologics and Immune Check Point Inhibitors. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107:623-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Suzuki A, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Miquel R, Smyrk TC, Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Castiella A, Lindor K, Björnsson E. The use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2011;54:931-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Björnsson ES, Medina-Caliz I, Andrade RJ, Lucena MI. Setting up criteria for drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis through a systematic analysis of published reports. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:1895-1909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Boer YS, Kosinski AS, Urban TJ, Zhao Z, Long N, Chalasani N, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH; Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Features of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Patients With Drug-induced Liver Injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:103-112.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Appleyard S, Saraswati R, Gorard DA. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by nitrofurantoin: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Björnsson ES, Bergmann O, Jonasson JG, Grondal G, Gudbjornsson B, Olafsson S. Drug-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis: Response to Corticosteroids and Lack of Relapse After Cessation of Steroids. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1635-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Harmon EG, McConnie R, Kesavan A. Minocycline-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Rare But Important Cause of Drug-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2018;21:347-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kimura H, Takeda A, Kikukawa T, Hasegawa I, Mino T, Uchida-Kobayashi S, Ohsawa M, Itoh Y. Liver injury after methylprednisolone pulse therapy in multiple sclerosis is usually due to idiosyncratic drug-induced toxicity rather than autoimmune hepatitis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;42:102065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chung Y, Morrison M, Zen Y, Heneghan MA. Defining characteristics and long-term prognosis of drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis: A retrospective cohort study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:66-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Björnsson ES, Stephens C, Atallah E, Robles-Diaz M, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Gerbes A, Weber S, Stirnimann G, Kullak-Ublick G, Cortez-Pinto H, Grove JI, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ, Aithal GP. A new framework for advancing in drug-induced liver injury research. The Prospective European DILI Registry. Liver Int. 2023;43:115-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu Q, Ge Z, Lv C, He Q. Interacting roles of gut microbiota and T cells in the development of autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1584001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Febres-Aldana CA, Alghamdi S, Krishnamurthy K, Poppiti RJ. Liver Fibrosis Helps to Distinguish Autoimmune Hepatitis from DILI with Autoimmune Features: A Review of Twenty Cases. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Alkashash A, Zhang X, Vuppalanchi R, Lammert C, Saxena R. Distinction of autoimmune hepatitis from drug-induced autoimmune like hepatitis: The answer lies at the interface. J Hepatol. 2024;81:e45-e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Björnsson ES, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Reply to: "Distinction of autoimmune hepatitis from drug-induced autoimmune like hepatitis: The answer lies at the interface". J Hepatol. 2024;81:e48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Codoni G, Kirchner T, Engel B, Villamil AM, Efe C, Stättermayer AF, Weltzsch JP, Sebode M, Bernsmeier C, Lleo A, Gevers TJ, Kupčinskas L, Castiella A, Pinazo J, De Martin E, Bobis I, Sandahl TD, Pedica F, Invernizzi F, Del Poggio P, Bruns T, Kolev M, Semmo N, Bessone F, Giguet B, Poggi G, Ueno M, Jang H, Elpek GÖ, Soylu NK, Cerny A, Wedemeyer H, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ, Zen Y, Taubert R, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B. Histological and serological features of acute liver injury after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bessone F, Ferrari A, Hernandez N, Mendizabal M, Ridruejo E, Zerega A, Tanno F, Reggiardo MV, Vorobioff J, Tanno H, Arrese M, Nunes V, Tagle M, Medina-Caliz I, Robles-Diaz M, Niu H, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Stephens C, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Nitrofurantoin-induced liver injury: long-term follow-up in two prospective DILI registries. Arch Toxicol. 2023;97:593-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tsutsui A, Harada K, Tsuneyama K, Nguyen Canh H, Ando M, Nakamura S, Mizobuchi K, Baba N, Senoh T, Nagano T, Shibata H, Aoki T, Takaguchi K. Histopathological analysis of autoimmune hepatitis with "acute" presentation: Differentiation from drug-induced liver injury. Hepatol Res. 2020;50:1047-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Autoimmune Hepatitis. 2019 May 4. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012– . [PubMed] |

| 29. | Kern E, VanWagner LB, Yang GY, Rinella ME. Liraglutide-induced autoimmune hepatitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:984-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ueno M, Takabatake H, Kayahara T, Morimoto Y, Notohara K, Mizuno M. Long-term outcomes of drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis after pulse steroid therapy. Hepatol Res. 2023;53:1073-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Martínez Casas OY, Díaz Ramírez GS, Marín Zuluaga JI, Santos Ó, Muñoz Maya O, Donado Gómez JH, Restrepo Gutiérrez JC. Autoimmune hepatitis - primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome. Long-term outcomes of a retrospective cohort in a university hospital. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:544-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tan CK, Ho D, Wang LM, Kumar R. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: A minireview. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:2654-2666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 33. | Bessone F, Hernandez N, Medina-Caliz I, García-Cortés M, Schinoni MI, Mendizabal M, Chiodi D, Nunes V, Ridruejo E, Pazos X, Santos G, Fassio E, Parana R, Reggiardo V, Tanno H, Sanchez A, Tanno F, Montes P, Tagle M, Arrese M, Brahm J, Girala M, Lizarzabal MI, Carrera E, Zerega A, Bianchi C, Reyes L, Arnedillo D, Cordone A, Gualano G, Jaureguizahar F, Rifrani G, Robles-Díaz M, Ortega-Alonso A, Pinazo-Bandera JM, Stephens C, Sanabria-Cabrera J, Bonilla-Toyos E, Niu H, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Drug-induced Liver Injury in Latin America: 10-year Experience of the Latin American DILI (LATINDILI) Network. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:89-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hisamochi A, Kage M, Ide T, Arinaga-Hino T, Amano K, Kuwahara R, Ogata K, Miyajima I, Kumashiro R, Sata M, Torimura T. An analysis of drug-induced liver injury, which showed histological findings similar to autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:597-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/