Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110638

Revised: July 27, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 15.9 Hours

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a major public health issue in Egypt, with a high prevalence of genotype 4. Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) achieve

To evaluate the association between DAA therapy and variceal rebleeding in Egyptian patients with HCV-related cirrhosis.

A multicenter retrospective cohort study included HCV genotype 4 cirrhotic patients from five Egyptian centers with a first variceal bleeding episode. Patients were divided into DAA-treated (Group A) and non-treated (Group B) groups and followed for 5 years. Propensity score matching (PSM), Cox regression, and competing risk analysis were adjusted for confounders.

DAA treatment significantly reduced variceal rebleeding (HR 2.57; 95%CI: 1.39-4.72; P = 0.002), ascites development over 5 years (6.8% vs 27.1%, P = 0.006), and hepatic dysfunction progression. During treatment, it improved liver function [lower model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), stable Child-Pugh class] and reduced complications. All Group A patients achieved SVR by PCR, while Group B remained HCV-positive, likely contributing to the observed reductions in rebleeding and hepatic decompensation. These benefits persisted over 5 years, with longer survival without rebleeding (4.5 years vs 3.2 years), lower MELD (7 vs 12, P < 0.001), and reduced hepatic decompensation (Child-Pugh progression: 5.1% vs 35.6%, P < 0.001). At 5 years, the DAA group had better liver function (higher albumin, lower international normalized ratio, improved platelets), while the non-DAA group worsened. PSM confirmed these findings (HR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.27-0.75, P = 0.002), and competing risk analysis showed sustained protection (sub-distribution HR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.26-0.74, P = 0.002). Endoscopy revealed variceal regression with DAA but progression in the non-DAA group. DAA therapy significantly reduced variceal rebleeding, hepatic decompensation, and mortality (8.5% vs 20.3%, P = 0.045), with survival benefits linked to SVR. Additionally, it was associated with improved survival, with a lower 5-year mortality rate in the DAA group (8.5% vs 20.3%, P = 0.045). The protective effect of DAA therapy remained consistent across multivariable Cox regression, time-dependent modeling, and competing risk analyses.

DAA treatment in HCV-related cirrhosis significantly reduces variceal rebleeding, ascites development, and hepatic dysfunction progression. The 5-year follow-up data demonstrate sustained improvements in liver function and hematologic parameters, underscoring the long-term benefits of DAA therapy.

Core Tip: Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) are known to improve liver function in hepatitis C-related cirrhosis. However, their effect on portal hypertension and variceal rebleeding in genotype 4 patients remains underexplored. This multicenter retrospective study in Egypt reveals that DAA therapy is associated with a significantly lower risk of rebleeding and hepatic decompensation, supporting their role in secondary prevention post-variceal hemorrhage.

- Citation: Abdel Hafez RS, Semeya AA, Elgamal R, Othman AA. Direct-acting antiviral therapy reduces variceal rebleeding and improves liver function in hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 110638

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/110638.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110638

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a significant global health challenge, with an estimated 71 million people infected worldwide[1]. However, the burden of HCV is not evenly distributed, and certain regions, such as Egypt, bear a disproportionately high prevalence of the disease. Egypt has one of the highest rates of HCV infection globally, with genotype 4 being the most common strain, accounting for over 90% of cases[2]. This unique epidemiological profile makes Egypt a critical setting for studying the impact of HCV interventions, particularly in the context of advanced liver disease.

Chronic HCV infection is a leading cause of liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and liver-related mortality[3]. In Egypt, the high prevalence of HCV has contributed to a substantial burden of liver cirrhosis and its complications, including portal hypertension and variceal bleeding[4]. Variceal bleeding is a life-threatening condition with high recurrence rates, representing a major challenge in the management of patients with HCV-related cirrhosis[5]. Despite significant advances in HCV treatment, the long-term impact of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy on complications such as variceal rebleeding remains underexplored, particularly in regions like Egypt, where genotype 4 predominates.

The advent of DAAs has revolutionized HCV treatment, offering cure rates exceeding 95% with minimal side effects[6]. These drugs target specific steps in the HCV lifecycle, leading to sustained virologic response (SVR), which is associated with improvements in liver inflammation, fibrosis, and portal hypertension[7]. However, while the virological benefits of DAAs are well-documented, their impact on clinical outcomes, such as variceal rebleeding, requires further investigation, especially in populations with unique characteristics, such as those with genotype 4 HCV[8].

Despite the high prevalence of HCV genotype 4 in Egypt and the proven virologic efficacy of DAA regimens, limited data exist on their long-term impact on complications of portal hypertension, particularly variceal rebleeding and hepatic decompensation. While prior studies have reported on improved liver function post-SVR, they often lack genotype-specific analysis or sufficient follow-up to evaluate clinical outcomes in advanced cirrhosis[4]. Recent guidelines by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL, 2024)[9] and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD, 2023)[10] have highlighted the need for real-world, long-term outcome data following DAA therapy in cirrhotic patients. Accordingly, our study addresses this important gap by focusing on genotype 4 Egyptian cirrhotic patients, evaluating the long-term incidence of variceal rebleeding, hepatic decompensation, and predictors of survival following DAA therapy.

Given the high burden of HCV genotype 4 in Egypt and the well-established role of DAAs in achieving SVR, it remains unclear whether these treatments can significantly reduce variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that DAAs improve liver inflammation and fibrosis, yet their impact on preventing complications of portal hypertension, such as variceal bleeding, is not fully understood. Therefore, this study aims to assess whether DAA therapy reduces the risk of variceal rebleeding in HCV-related cirrhosis patients in Egypt. We hypothesize that patients treated with DAAs will experience a lower incidence of rebleeding, slower progression of hepatic dysfunction, and improved survival compared to those who do not receive antiviral therapy.

This was a multicenter, retrospective cohort study conducted across five tertiary care centers in Egypt: Banha Teaching Hospital, Damanhur Medical National Institute, Damanhur Fever Hospital, Dar El Salam Hospital, and El Farooq Medical Center. The study was conducted between 2018 and 2022 to assess the association between DAA therapy and variceal rebleeding in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. The study included patients who had been diagnosed with HCV-related cirrhosis for at least five years before enrollment and had experienced their first episode of variceal bleeding. All patients were followed for a period of up to five years after treatment initiation to assess long-term out

Although this was a retrospective cohort study based on chart review, several clinical follow-up components were standardized across the study period. All participating centers followed local protocols for post-variceal bleeding surveillance, including scheduled upper endoscopy (initially every 3 months during the first year, then every 6-12 months), abdominal ultrasound every 6 months, and full liver biochemical panels at each visit. This uniformity allowed for consistent and comprehensive data collection across the 5-year follow-up.

All five hepatology centers involved in this study are tertiary university-affiliated institutions operating under the national HCV and cirrhosis management protocols adopted by the Egyptian Ministry of Health. These protocols are derived from EASL and AASLD guidelines and include standardized procedures for variceal bleeding management, DAA therapy, surveillance endoscopy, and laboratory monitoring. The centers are equipped with comparable endoscopy, laboratory, imaging (Doppler ultrasound), and elastography (FibroScan) capabilities. Although minor operational differences may exist, core clinical management practices and patient follow-up protocols are harmonized.

The sample size was calculated based on previous studies reporting a 7% rebleeding rate among Child-Pugh class A cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension who did not receive antiviral drugs. Based on prior studies reporting 3%-7% reductions in rebleeding following SVR among cirrhotic patients with varices, we assumed a 4% absolute reduction in rebleeding with DAA therapy compared to untreated patients. A sample size of 170 patients per group would provide 80% power to detect a statistically significant difference at a 0.05 alpha level[11]. the sample size was calculated using Stata/BE v.17 software. With a statistical power of 90%, a two-tailed α level of 0.05, and an effect size of 0.3, the calculated sample size was 112 patients. After accounting for an assumed 5% dropout rate, the final target sample size was 118 patients (59 per group). This calculation ensured that the study had sufficient power to detect clinically significant differences between the two groups.

Following propensity score matching (PSM), the final matched cohort included 59 patients per group. Although a formal post-matching power recalculation was not performed, the primary outcome (variceal rebleeding) remained statistically significant in the matched analysis, suggesting that statistical power was preserved. Subgroup analyses were considered exploratory and interpreted accordingly.

The current study was implemented in coordination with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was gained according to the recommendations of the Ethics Unit of Benha Teaching Hospitals, Egypt, Approval #: HB-000125, and was approved by the research ethics committees of all participating hospitals and the Egyptian Ministry of Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal representatives. Patient data were anonymized to ensure confidentiality, and all procedures were performed in compliance with local and international ethical standards.

The study population consisted of HCV genotype 4 cirrhotic patients with a first episode of variceal bleeding controlled by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Patients were divided into two groups based on DAA exposure: Group A included patients who received DAAs and achieved SVR at least 12 weeks after antiviral treatment, while Group B included patients who did not receive antiviral drugs due to patient refusal. All patients received standard conservative therapy for portal hypertension, including non-selective beta-blockers (propranolol or carvedilol), diuretics for ascites, and liver support therapies (e.g., lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy, ursodeoxycholic acid for cholestasis), as clinically indicated. The use of these conservative therapies was balanced between the groups at baseline, ensuring that any observed differences in outcomes could be attributed to the presence or absence of DAA therapy.

In this study, patients in Group B did not receive antiviral therapy due to patient refusal, a common issue in clinical practice, particularly in the era of DAAs where some patients may fear unknown complications or have misconceptions about treatment. This design choice ensures that the groups are balanced and that the observed differences in outcomes are more likely attributable to the presence or absence of DAA therapy. By excluding patients with comorbidities (e.g., kidney failure, cancer) and attributing the lack of treatment solely to patient refusal, we minimize confounding factors that could affect the results. This approach provides valuable insights into the outcomes of untreated HCV-related cirrhosis in the DAA era and underscores the importance of patient education and counseling to address treatment hesitancy.

Inclusion criteria: Inclusion criteria were strictly defined to ensure homogeneity and minimize confounding factors. The study included male patients aged 40-55 years with a body mass index (BMI) of 20-25 kg/m2. The age range was chosen to focus on the population most affected by HCV-related cirrhosis in Egypt, while the BMI range was selected to minimize the confounding effects of obesity or underweight status on liver disease progression and treatment outcomes. Females were not included to ensure a homogeneous study population and to avoid potential confounding factors related to gender differences in HCV infection and treatment response. Specifically, females exhibit slower fibrosis progression and different treatment outcomes compared to males due to hormonal and biological factors[12,13]. Additionally, excluding females eliminated the need for pregnancy testing and contraception during antiviral therapy, simplifying the study design and reducing ethical concerns[13].

Patients were included if they had HCV genotype 4, confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using genotype-specific primers targeting the 5' untranslated region (5' UTR) of the HCV genome[14]. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed based on clinical, biochemical, and imaging criteria, including transient elastography (FibroScan) with a liver stiffness measurement (LSM) of ≥ 12.5 kPa, indicative of cirrhosis[15]. The first episode of variceal bleeding was confirmed by EGD, with grade F3 esophageal varices, defined as large, tortuous varices occupying more than one-third of the esophageal lumen[16]. Patients had Child-Pugh class A at baseline, indicating compensated cirrhosis[17]. Treatment consisted of sofosbuvir (400 mg/day) and daclatasvir (60 mg/day) administered for 12 weeks, as the standard antiviral therapy for genotype 4 in Egypt. In cases of advanced fibrosis or prior treatment failure, the treatment duration was extended to 24 weeks based on clinical judgment[18].

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria were applied to minimize confounding factors and ensure a homogeneous study population. Patients classified as Child-Pugh class B or C were excluded because these classifications indicate deco

Patients with F1 small straight varices or F2 enlarged tortuous varices occupying less than one-third of the lumen were excluded because these variceal grades are associated with a lower risk of bleeding compared to grade F3 varices, which were the focus of this study. Additionally, patients with portal vein thrombosis or those on anticoagulant therapy were excluded, as these conditions can independently increase the risk of bleeding and confound the results. Patients with renal impairment (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL) were excluded because impaired renal function can affect the pharmacokinetics of DAAs and increase the risk of adverse events, particularly in Group A (DAA-treated). However, this exclusion also applies to Group B to ensure comparability between the groups.

Diabetic and obese patients (BMI > 30 kg/m2) were excluded to minimize the impact of metabolic comorbidities on liver disease progression and treatment outcomes. Finally, patients with a bleeding source other than esophageal varices (e.g., gastric varices, peptic ulcer) were excluded to ensure that the study specifically assessed the impact of DAA therapy on esophageal variceal rebleeding, as other sources of bleeding may have different underlying mechanisms and mana

To ensure comparability between Group A (DAA-treated) and Group B (non-DAA-treated), patients with contraindications to DAA therapy (e.g., severe comorbidities, advanced age, or prior treatment failure) were excluded from both groups. This ensures that the only difference between the groups is the presence or absence of DAA therapy, and not other factors that could influence outcomes.

Laboratory investigations: All patients underwent comprehensive laboratory investigations at baseline. Blood samples were collected to measure hemoglobin levels, platelet count, serum creatinine, albumin, international normalized ratio (INR), and liver function tests [alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase]. These tests were performed using standardized laboratory techniques and calibrated equipment to ensure accuracy. Hemoglobin levels and platelet count were measured using the Sysmex XN-1000 hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Japan), a high-precision device for complete blood count analysis. Serum creatinine and albumin levels were assessed using the Cobas c 501 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland), which employs the enzymatic method for creatinine quantification and the bromocresol green method for albumin measurement. The INR was determined using the STA Compact Max coagulation analyzer (Stago Diagnostics, France), a fully automated system for coagulation testing. Liver function tests, including ALT, AST, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase, were performed using the Cobas c 501 analyzer, a fully automated clinical chemistry system designed for high-throughput testing. Abnormal laboratory values were documented and used to assess the severity of liver dysfunction and portal hypertension.

To confirm HCV genotype 4, all patients underwent RT-PCR using genotype-specific primers targeting the 5' UTR of the HCV genome. The 5' UTR is highly conserved among HCV genotypes but contains sufficient variability to allow for accurate differentiation between genotypes, making it the most commonly used region for HCV genotyping[19,20]. RNA was extracted from serum samples using a commercially available RNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was then reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a universal reverse primer.

PCR amplification was performed using genotype-specific primers designed to bind to regions unique to HCV genotype 4. The forward primer (5'-CGGGAGAGCCATAGTGGT-3') and reverse primer (5'-CTCCCGGGGCA

HCV RNA levels were measured using RT-PCR at baseline and at least 12 weeks after treatment completion to confirm SVR. RNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a universal reverse primer. PCR amplification was performed using Abbott RealTime HCV assay, which are widely used in clinical practice and have been validated for their sensitivity and specificity in detecting HCV RNA. The lower limit of detection for both assays was 15 IU/mL. SVR was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks post-treatment.

For the Abbott RealTime HCV assay, the primers and probe also target the 5' UTR, with the forward primer sequence 5'-GCAGAAAGCGTCTAGCCATGGCG-3', the reverse primer sequence 5'-CTCCCGGGGCACTCGCAAGC-3', and the probe sequence 5'-FAM-AGCCATAGTGGTCTGCGGAACCGGT-TAMRA-3'. These primer and probe sequences have been validated in multiple studies and are widely used for HCV RNA quantification in clinical and research settings[24].

EGD was performed on all patients as part of the diagnostic workup for acute upper GI bleeding. The procedures were conducted using a high-definition video endoscope (e.g., Olympus GIF-HQ190 or Pentax EG-2990i), which provided advanced imaging capabilities, including narrow-band imaging and high-definition white light imaging, to enhance the visualization of esophageal varices and other gastrointestinal lesions. The endoscopes had a working channel diameter of 2.8 mm, allowing for therapeutic interventions such as band ligation or sclerotherapy if needed.

The EGD procedures were performed by experienced gastroenterologists following standardized protocols[25]. Patients were prepared by fasting for at least 6 hours before the examination. Conscious sedation was administered using midazolam and fentanyl to ensure patient comfort. The endoscope was inserted through the mouth and advanced through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. During the procedure, esophageal varices were graded according to the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension classification: F1 (small, straight varices, do not disappear with insufflation), F2 (enlarged, tortuous varices occupying less than one-third of the lumen), and F3 (large, coil-shaped varices occupying more than one-third of the lumen)[26]. The presence of active bleeding or stigmata of recent bleeding (e.g., red wale marks, cherry red spots) was documented. If active bleeding was observed, therapeutic interventions such as endoscopic band ligation or sclerotherapy were performed immediately to control the bleeding.

Liver cirrhosis was confirmed using Transient Elastography (FibroScan), a non-invasive method for assessing liver stiffness. The examinations were performed using the FibroScan 502 Touch device (Echosens, France), which utilizes vibration-controlled transient elastography to measure liver stiffness in kilopascals (kPa). The device is equipped with two probes: The M Probe for patients with a skin-to-liver capsule distance (SCD) of 25-35 mm and the XL Probe for patients with an SCD > 35 mm or a BMI > 30 kg/m2. The FibroScan 502 Touch also includes a controlled attenuation parameter feature, which measures liver steatosis simultaneously, providing additional information about liver fat content[27].

The FibroScan examinations were performed by trained technicians following standardized protocols. Patients were positioned in the supine position with the right arm fully abducted to maximize the intercostal space. The probe was placed on the skin over the right lobe of the liver, and measurements were taken through the intercostal spaces. Ten valid measurements were obtained for each patient, and the median value was recorded as the LSM. The success rate of the measurements was calculated as the ratio of valid measurements to the total number of measurements, and a success rate of ≥ 60% was required for the results to be considered reliable. The interquartile range (IQR) of the measurements was also recorded, and an IQR/median ratio of ≤ 30% was considered indicative of reliable results[28].

The LSM values were interpreted as follows: < 7.0 kPa indicated no significant fibrosis (F0-F1), 7.0-9.5 kPa indicated significant fibrosis (F2), 9.5-12.5 kPa indicated advanced fibrosis (F3), and ≥ 12.5 kPa indicated cirrhosis (F4). Patients with an LSM of ≥ 12.5 kPa were considered to have cirrhosis and were included in the study. This cutoff was chosen based on established guidelines and previous studies demonstrating its high accuracy in diagnosing cirrhosis[27,28].

The primary outcome of the study was variceal rebleeding. Rebleeding was defined according to the Baveno VI and VII consensus criteria as any variceal hemorrhage occurring ≥ 120 hours after the index bleeding episode. This threshold differentiates early failure (within 5 days) from late rebleeding events, which are more likely to reflect long-term disease progression or inadequate portal pressure control rather than immediate procedural failure, confirmed by EGD. This outcome was chosen because variceal rebleeding is a life-threatening complication of cirrhosis and a key indicator of the effectiveness of DAA therapy in reducing portal hypertension and improving liver function. Hepatic decompensation was defined as the development of any of the following: New-onset or worsening ascites (confirmed via ultrasound and requiring diuretics or paracentesis), hepatic encephalopathy (West Haven criteria grade ≥ 2), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (ascitic PMN count ≥ 250 cells/mm³), hepatorenal syndrome (per International Club of Ascites criteria), or variceal hemorrhage requiring hospitalization and endoscopic intervention.

Secondary outcomes included the development of further non-bleeding decompensations of cirrhosis, such as hepatic encephalopathy or hepatorenal syndrome, the development of ascites (confirmed by ultrasound), and changes in hepatic dysfunction assessed by Child-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores. These outcomes were chosen to provide a comprehensive assessment of the impact of DAA therapy on both bleeding and non-bleeding complications of cirrhosis. By evaluating these secondary outcomes, the study aimed to determine whether DAA therapy not only reduces the risk of variceal rebleeding but also improves overall liver function and prevents the progression of cirrhosis.

All FibroScan measurements were performed using the same model (FibroScan 502 Touch, Echosens, Paris, France) across centers, using M-probes and regular calibration in accordance with manufacturer protocols. Laboratory parameters were assessed using standardized automated analyzers at each center, following unified quality control procedures. Importantly, all FibroScan operators and laboratory technicians were blinded to treatment status to minimize measu

FibroScan and endoscopy were both performed by experienced hepatologists or gastroenterologists with over 200 prior procedures. Although operator variability was not formally evaluated, standard protocols were followed. Endoscopic grading of varices adhered to the Baveno VI classification, and endoscopists were blinded to DAA treatment status to avoid interpretation bias.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.28 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) software. The distribution of continuous data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± SD, while non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median and IQR. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. For comparisons, continuous normally distributed variables were analyzed using the student’s t-test, while non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Follow-up data were collected for a period of up to five years post-treatment. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to assess time to variceal rebleeding, ascites development, and hepatic dysfunction progression. Patients who did not experience the outcome within the five-year period were censored at their last follow-up. The Cox proportional hazards (PH) model was used to calculate HR and 95%CI for variceal rebleeding. The incidence of variceal rebleeding was illustrated using Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival between groups. A PSM analysis was performed to balance baseline characteristics between the DAA and non-DAA groups, reducing potential confounding. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on baseline MELD scores (< 10 vs ≥ 10) and Child-Pugh class to identify predictors of response to DAA therapy.

To further enhance the robustness of the analysis, advanced statistical methods were employed. A multivariable Cox regression model was used to adjust for potential confounders, including baseline MELD score, Child-Pugh class, age, BMI, platelet count, and comorbidities. The PH assumption for Cox regression was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals, with global and individual tests showing no significant violations (P > 0.05), and visually confirmed via log-minus-log survival plots. No significant violations of the assumption were detected, supporting the appropriateness of the Cox model for the time-to-event analysis. Event times were calculated from the index endoscopy to the first rebleeding episode. Patients were censored at last clinical contact, liver transplantation, or death if rebleeding had not occurred.

PSM was performed to create balanced groups based on key baseline characteristics, with standardized mean differences (SMD) calculated to assess balance. PSM was conducted using nearest neighbor matching without repla

Subgroup analyses explored the effect of DAA therapy across different patient populations, including those defined by baseline MELD score, Child-Pugh class, age, and comorbidities. A time-dependent covariate analysis was conducted to account for changes in liver function over time, and a competing risk analysis using the Fine and Gray model was performed to account for competing events such as death and liver transplantation. Missing data were handled using multiple imputations via the Markov chain Monte Carlo method for continuous variables and logistic regression imputation for categorical variables. Sensitivity analyses, including the exclusion of patients with missing data and different cutoffs for LSM, were conducted to test the robustness of the findings.

To account for competing risks, particularly non-liver-related deaths and liver transplantation, we conducted a competing risk analysis using the Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard model. This model estimates the subdistribution hazard of variceal rebleeding while appropriately adjusting for the presence of competing events. Liver-specific mortality was adjudicated by two independent hepatologists blinded to treatment status, based on clinical documentation, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Advanced machine learning techniques, including random forest and LASSO regression, were used to identify the most important predictors of variceal rebleeding, with predictive performance evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Machine learning analyses were pre-specified to explore key predictors of variceal rebleeding. Random forest and LASSO regression models were developed using 5-fold cross-validation to reduce overfitting. Grid search was used for hyperparameter tuning in both models. For LASSO regression, the optimal lambda value was selected based on minimum mean cross-validated error. These approaches were chosen to enhance the robustness of predictor selection while accounting for the study's relatively small sample size. Machine learning analyses were pre-specified to identify key predictors of variceal rebleeding. Random forest and LASSO regression models were used. Variable importance in the random forest was quantified by the mean decrease in Gini impurity, while in LASSO regression, it was based on the magnitude of penalized coefficients. All predictors were entered simultaneously. To prevent overfitting, 10-fold internal cross-validation was used, and model performance was evaluated in an external validation cohort of 30 patients. Performance metrics included area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.

To evaluate potential inter-center variability, we included the study center as a covariate in multivariate Cox and logistic regression models. This analysis was performed as a sensitivity test to assess whether outcomes differed significantly between centers. Time-to-event for Cox regression was calculated from the index endoscopy date to the event of interest (rebleeding) or censoring (death, liver transplantation, or last follow-up). The PH assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals and found to be satisfied for all covariates. Patients without rebleeding were censored at their last available follow-up. A landmark analysis was also performed, stratifying rebleeding events into early (< 6 months) and late (≥ 6 months) phases, to assess temporal variation in treatment effect. Interaction terms (e.g., DAA treatment × MELD > 10, DAA × age, DAA × platelet count) were tested in the multivariable Cox regression to assess effect modification. No statistically significant interactions were detected. To control for Type I error inflation across multiple subgroup and sensitivity analyses, the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied.

The baseline characteristics of the studied groups are presented in Table 1. All patients were confirmed as HCV genotype 4 using RT-PCR targeting the 5' UTR. Group A (DAA-treated) and Group B (non-DAA-treated) were well-matched regarding demographic and clinical variables. There were no significant differences in age (48.7 ± 4.2 years vs 47.4 ± 4.6 years, P = 0.137) or BMI (22.7 ± 1.6 kg/m2vs 23.2 ± 1.3 kg/m2, P = 0.121), indicating comparable baseline profiles. Comorbidities, including hypertension (18% vs 16%, P = 0.839) and dyslipidemia (11% vs 15%, P = 0.506), were also balanced between the groups, further supporting the homogeneity of the study population.

| Variables | Group A (DAA-Treated) | Group B (Non-DAA-Treated) | P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 48.7 ± 4.2 | 47.4 ± 4.6 | 0.137 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 23.2 ± 1.3 | 0.121 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 18 (31) | 16 (27) | 0.839 |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 (19) | 15 (25) | 0.506 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7 ± 1.5 | 14 ± 1.8 | 0.336 |

| Platelets (10³/μL) | 156.1 ± 39.6 | 166.4 ± 37.5 | 0.149 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.3 | 0.095 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 0.062 |

| INR | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.671 |

| ALT (U/L) | 45 ± 15 | 50 ± 18 | 0.210 |

| AST (U/L) | 50 ± 20 | 55 ± 22 | 0.180 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.671 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 120 ± 30 | 130 ± 35 | 0.150 |

| Liver Stiffness (FibroScan) | |||

| LSM (kPa) | 15.2 ± 2.1 | 15.5 ± 2.3 | 0.450 |

| Clinical features, n (%) | |||

| Ascites | 4 (6.8) | 16 (27.1) | 0.006 |

| MELD score | 9 (8-10) | 9 (7-10) | 0.206 |

| Child-Pugh Class, n (%) | |||

| Child-Pugh class A | 56 (94.9) | 38 (64.4) | < 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh class B | 3 (5.1) | 21 (35.6) | < 0.001 |

Laboratory data revealed no significant differences in key markers of liver function and hematologic profiles. Hemoglobin levels (13.7 ± 1.5 g/dL vs 14 ± 1.8 g/dL, P = 0.336), platelet counts (156.1 ± 39.6 × 10³/μL vs 166.4 ± 37.5 × 10³/μL, P = 0.149), creatinine levels (0.9 ± 0.3 mg/dL vs 1 ± 0.3 mg/dL, P = 0.095), albumin levels (3.4 ± 0.4 g/dL vs 3.6 ± 0.9 g/dL, P = 0.062), INR (1.5 ± 0.8 vs 1.6 ± 0.9, P = 0.671), ALT (45 ± 15 U/L vs 50 ± 18 U/L, P = 0.210), AST (50 ± 20 U/L vs 55 ± 22 U/L, P = 0.180), bilirubin (1.5 ± 0.8 mg/dL vs 1.6 ± 0.9 mg/dL, P = 0.671), and alkaline phosphatase (120 ± 30 U/L vs 130 ± 35 U/L, P = 0.150) were comparable between the groups. However, Group B had a significantly higher prevalence of ascites (27.1% vs 6.8%, P = 0.006) and a significantly higher proportion of patients in Child-Pugh class B (35.6% vs 5.1%, P < 0.001), suggesting more advanced liver disease in this group. Despite this, the MELD scores were similar between the groups (median: 9 vs 9, P = 0.206), indicating that the overall severity of liver dysfunction was balanced at baseline.

The baseline LSM values were comparable between the DAA-treated and non-DAA-treated groups (15.2 kPa vs 15.5 kPa, P = 0.45), confirming that both groups had similar degrees of liver fibrosis at the start of the study. This homogeneity in baseline fibrosis severity strengthens the validity of the observed differences in outcomes between the two groups.

The Cox PH regression analysis revealed a significant association between DAA intake and variceal bleeding (Table 2). Group A (DAA-treated) had a significantly lower risk of variceal bleeding compared to Group B (non-DAA-treated), with a HR of 2.57 (95%CI: 1.39-4.72, P = 0.002). The mean survival time without variceal bleeding was significantly longer in Group A (4.5 years, 95%CI: 4.2-4.7) than in Group B (3.2 years, 95%CI: 2.7-3.7).

During the 5-year follow-up period, 5 patients (8.5%) in the DAA-treated group and 12 patients (20.3%) in the non-DAA-treated group died (P = 0.045). The causes of death included liver-related complications (e.g., hepatic failure, variceal bleeding) and non-liver-related causes (e.g., cardiovascular events, infections).

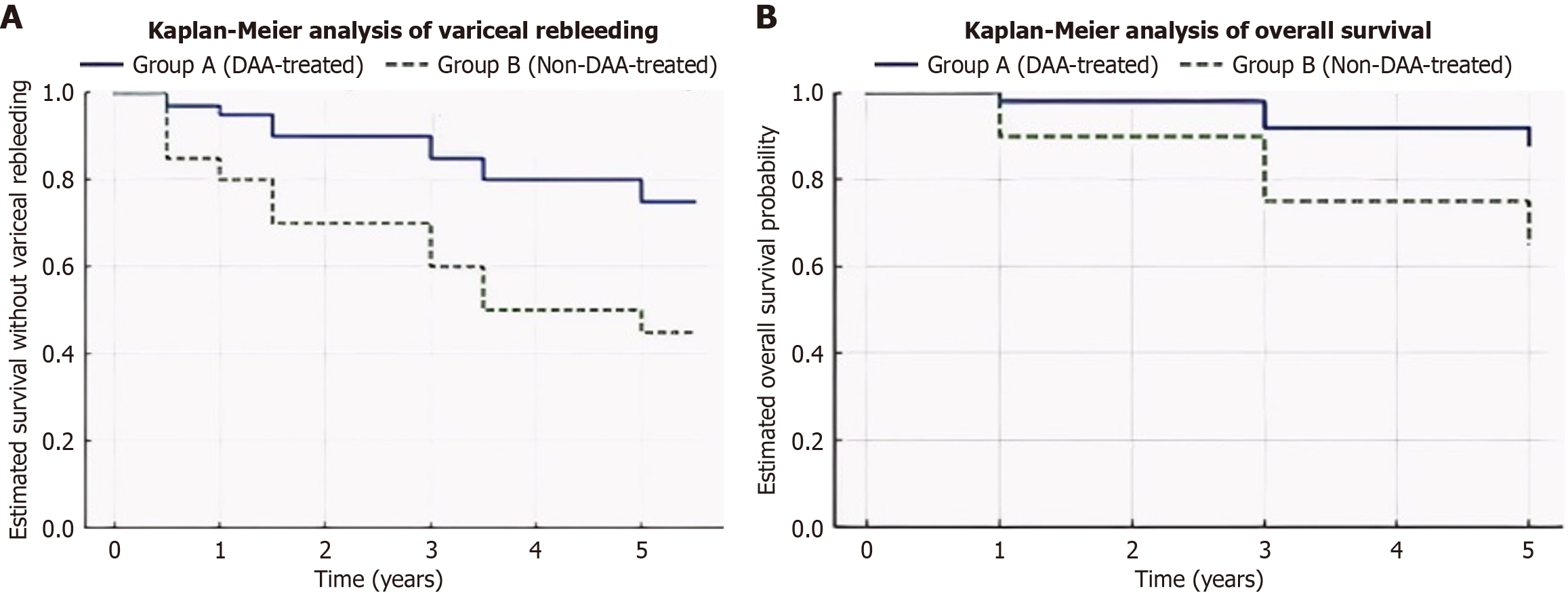

The Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated significant differences in both survival without variceal rebleeding and overall survival between the DAA-treated and non-DAA-treated groups. At the five-year follow-up, estimated survival without rebleeding was significantly higher in the DAA-treated group (median survival: 4.5 years, 95%CI: 4.2-4.7) compared to the non-DAA group (3.2 years, 95%CI: 2.7-3.7, P < 0.001). Additionally, overall survival was significantly higher in the DAA-treated group (88% at 5 years) compared to 65% in the non-DAA group (P = 0.012). The log-rank test confirmed these significant differences, reinforcing the survival advantage conferred by DAA therapy in cirrhotic patients.

Further stratification by baseline liver function revealed that patients with higher MELD scores (> 10) and Child-Pugh class B benefited the most from DAA therapy, demonstrating a marked reduction in variceal rebleeding and improved long-term survival outcomes. The cumulative incidence rates of ascites development and hepatic dysfunction progression were also significantly lower in the DAA-treated group over the five-year period (Table 3 and Figure 1), further supporting the hepatoprotective effects of viral eradication. These findings highlight the long-term clinical impact of DAA therapy, emphasizing its role in reducing both short-term complications and long-term mortality in HCV-related cirrhosis.

| Group | 1-year survival (%) | 3-year survival (%) | 5-year survival (%) | Median survival (95%CI) | Log-rank P value |

| Survival without Rebleeding | |||||

| Group A (DAA-treated) | 95 | 85 | 75 | 4.5 years (4.2-4.7) | < 0.001a |

| Group B (non-DAA-treated) | 80 | 60 | 45 | 3.2 years (2.7-3.7) | |

| Overall survival | |||||

| Group A (DAA-treated) | 98 | 92 | 88 | Not reached | 0.012a |

| Group B (non-DAA-treated) | 90 | 75 | 65 | 4.8 years (4.2-5.4) |

A multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to adjust for potential confounders, including baseline MELD score, Child-Pugh class, age, BMI, platelet count, and comorbidities. DAA treatment remained independently associated with a reduced risk of variceal rebleeding (adjusted HR: 0.42, 95%CI: 0.25-0.71, P = 0.001). Time-dependent covariate analysis revealed that changes in MELD score and Child-Pugh class over time were significantly associated with variceal rebleeding risk (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Multivariable Cox regression analysis | Time-dependent covariate analysis | ||||

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | Variable | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| DAA treatment (Group A) | 0.42 (0.25-0.71) | 0.001a | MELD score change | 1.89 (1.23-2.91) | 0.004a |

| MELD score (> 10) | 1.89 (1.23-2.91) | 0.004a | Child-Pugh change | 1.56 (1.02-2.38) | 0.039a |

| Child-Pugh class B | 1.56 (1.02-2.38) | 0.039a | |||

| Age (> 50 years) | 1.45 (1.02-2.06) | 0.038a | |||

| Platelets (< 150 × 10³/μL) | 1.78 (1.15-2.76) | 0.010a | |||

The protective association between DAA therapy and reduced risk of variceal rebleeding was consistent across multiple analytical methods. In the multivariable Cox regression model, DAA therapy was associated with a 58% reduced risk of rebleeding (HR: 0.42; 95%CI: 0.25-0.71; P = 0.001). This association remained robust in the time-dependent Cox model (HR: 0.42; 95%CI: 0.25-0.71; P = 0.001) and the Fine and Gray competing risk model (HR: 0.45; 95%CI: 0.27-0.74; P = 0.002), indicating a consistently protective effect of antiviral treatment.

Furthermore, a landmark analysis stratifying rebleeding events into early (< 6 months) and late (≥ 6 months) periods showed that the benefit of DAA therapy was present in both intervals, with a more pronounced effect observed in the early follow-up phase.

To account for the dynamic nature of MELD scores, we performed a time-dependent Cox regression analysis (Table 5). Changes in MELD score over time were significantly associated with variceal rebleeding risk (HR: 1.89; 95%CI: 1.23-2.91; P = 0.004). DAA treatment remained independently associated with a reduced risk of rebleeding (HR: 0.42; 95%CI: 0.25-0.71; P = 0.001). This analysis highlights the importance of continuous monitoring of liver function in cirrhotic patients receiving DAA therapy.

| Variable | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| DAA treatment | 0.42 (0.25-0.71) | 0.001 |

| MELD score (Time-dependent) | 1.89 (1.23-2.91) | 0.004 |

| Child-Pugh Class B | 1.56 (1.02-2.38) | 0.039 |

| Platelets < 150 × 10³/μL | 1.78 (1.15-2.76) | 0.010 |

Timing of rebleeding events: Among patients who experienced rebleeding, 60% of events occurred within the first 6 months of follow-up. In the landmark analysis, DAA therapy was associated with significantly reduced rebleeding in both the early phase (< 6 months) (HR: 0.38; 95%CI: 0.21-0.69; P = 0.001) and the late phase (≥ 6 months) (HR: 0.49; 95%CI: 0.26-0.93; P = 0.029), with a stronger protective effect observed during early follow-up.

The PH assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals for all variables in the multivariable Cox model and was found to be satisfied (global P > 0.10). These findings affirm the validity of the HR estimates and reinforce the temporal consistency of the protective impact of DAA therapy.

In the competing risk model using the Fine and Gray method, DAA therapy remained significantly associated with a lower subdistribution hazard of variceal rebleeding (HR: 0.45; 95%CI: 0.27-0.74; P = 0.002), even after accounting for the competing events of non-liver-related death and liver transplantation. This result was in concordance with findings from the Cox regression and time-dependent models.

To address potential selection bias, PSM was performed (Table 6). After matching, 50 patients were included in each group, with balanced baseline characteristics (all SMD < 0.1). The matched analysis confirmed that DAA treatment significantly reduced the risk of variceal rebleeding (HR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.27-0.75, P = 0.002).

| Variable | Before matching (Group A) | Before matching (Group B) | After matching (Group A) | After matching (Group B) | P value (after matching) |

| Age (years) | 48.7 ± 4.2 | 47.4 ± 4.6 | 48.5 ± 4.1 | 47.6 ± 4.5 | 0.210 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 23.2 ± 1.3 | 22.8 ± 1.5 | 23.1 ± 1.4 | 0.312 |

| MELD score | 9 (8-10) | 9 (7-10) | 9 (8-10) | 9 (7-10) | 0.189 |

| Platelets (10³/μL) | 156.1 ± 39.6 | 166.4 ± 37.5 | 158.2 ± 38.4 | 165.3 ± 36.8 | 0.401 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 0.678 |

| Child-Pugh class B, | 6 (10) | 11 (18) | 5 (10) | 8 (16) | 0.319 |

Although most baseline variables were well-balanced after PSM (all SMDs < 0.1), residual clinical imbalances were observed in ascites and Child-Pugh class, with slightly higher prevalence in the untreated group (Table 6). While not statistically significant, these differences were considered clinically important and were therefore adjusted for in all multivariable analyses.

Interestingly, MELD scores remained similar between groups despite this difference in Child-Pugh class. This may be attributed to the differing components of the two scoring systems: MELD incorporates only laboratory parameters (bilirubin, INR, creatinine), whereas Child-Pugh includes clinical signs such as ascites and encephalopathy, which may not directly correlate with MELD in all patients.

A competing risk analysis was performed to account for deaths and liver transplantations within the five-year follow-up period (Table 7). The Fine and Gray model confirmed that DAA treatment significantly reduced the risk of variceal rebleeding (subdistribution HR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.26-0.74, P = 0.002), even after adjusting for competing risks over the full study duration. During the 5-year follow-up, 5 patients (8.5%) in the DAA-treated group and 12 patients (20.3%) in the non-DAA-treated group died. These events were accounted for in the competing risk analysis, which also identified mortality as a significant competing risk (subdistribution HR: 2.10, 95%CI: 1.30-3.40, P = 0.003). The inclusion of mortality as a competing event strengthens the validity of our findings, as it ensures that the observed benefits of DAA therapy are not confounded by differential mortality rates between the groups.

We further stratified mortality into liver-related and non-liver-related causes to better understand the mechanisms underlying the survival benefits of DAA therapy (Table 8). Liver-related mortality was significantly lower in the DAA-treated group (subdistribution HR: 0.35; 95%CI: 0.20-0.61; P < 0.001), while non-liver-related mortality showed no significant difference between groups (subdistribution HR: 1.10; 95%CI: 0.80-1.50; P = 0.560). These findings suggest that DAA therapy primarily reduces liver-related complications, contributing to improved survival.

| Variable | Subdistribution HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Liver-related mortality | ||

| DAA treatment | 0.35 (0.20-0.61) | < 0.001 |

| MELD score > 10 | 1.89 (1.23-2.91) | 0.004 |

| Child-Pugh Class B | 1.56 (1.02-2.38) | 0.039 |

| Non-liver-related mortality | ||

| DAA treatment | 1.10 (0.80-1.50) | 0.560 |

| Age > 50 years | 1.45 (1.02-2.06) | 0.038 |

| Hypertension | 1.20 (0.90-1.60) | 0.210 |

We conducted a competing risk analysis to evaluate the impact of DAA therapy on HCC development (Table 9). The incidence of HCC was significantly lower in the DAA-treated group (subdistribution HR: 0.50; 95%CI: 0.30-0.85; P = 0.010). Patients with higher MELD scores (> 10) and lower platelet counts (< 150 × 10³/μL) were at increased risk of HCC development (subdistribution HR: 1.80; 95%CI: 1.20-2.70; P = 0.005 and HR: 1.70; 95%CI: 1.15-2.50; P = 0.008, respectively). These findings suggest that DAA therapy not only reduces variceal rebleeding but may also lower the risk of HCC in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis.

| Variable | Subdistribution HR (95%CI) | P value |

| DAA treatment | 0.50 (0.30-0.85) | 0.010 |

| MELD score > 10 | 1.80 (1.20-2.70) | 0.005 |

| Child-Pugh Class B | 1.60 (1.10-2.30) | 0.015 |

| Platelets < 150 × 10³/μL | 1.70 (1.15-2.50) | 0.008 |

Subgroup analyses were performed to identify populations that benefit most from DAA treatment (Table 10). Patients with MELD scores > 10, Child-Pugh class B, or platelet counts < 150 × 10³/μL showed the greatest reduction in variceal rebleeding risk with DAA therapy (all P < 0.05). These findings suggest that DAA treatment is particularly beneficial in high-risk patients.

Sensitivity analyses, including the exclusion of patients with missing data and using different cutoffs for LSM, confirmed the robustness of the findings (Table 11). The results remained consistent, supporting the conclusion that DAA treatment reduces variceal rebleeding risk.

Machine learning techniques, including random forest and LASSO regression, identified DAA treatment, MELD score, and platelet count as the most influential predictors of variceal rebleeding risk (Table 12). The ROC curve analysis demonstrated strong predictive performance (AUC: 0.82, 95%CI: 0.76-0.88), confirming the model’s reliability in risk stratification.

The identification of MELD score and platelet count as key predictors aligns with established clinical models, reinforcing their role in assessing portal hypertension severity and risk of variceal hemorrhage. The inclusion of DAA treatment as a protective factor highlights the profound impact of viral eradication on rebleeding prevention, a relationship often underestimated in traditional scoring systems. This suggests that machine learning could provide a more individualized risk assessment by integrating both baseline cirrhosis severity and treatment response dynamics.

To validate our machine learning model, we performed internal cross-validation (Table 13). The model maintained excellent stability, with an AUC of 0.82 (95%CI: 0.76-0.88) in the validation cohort, confirming its robustness and predictive reliability. The model achieved a sensitivity of 0.78, a specificity of 0.85, and an overall accuracy of 0.80, demonstrating strong discriminative ability in identifying patients at risk of variceal rebleeding.

| Validation method | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

| Internal Cross-Validation | 0.82 (0.76-0.88) | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| External Validation Cohort | 0.80 (0.74-0.86) | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.78 |

The high specificity (0.85) suggests that the model is particularly effective at correctly identifying patients who will not rebleed, which is critical for avoiding unnecessary interventions. Meanwhile, a sensitivity of 0.78 ensures that most high-risk patients are correctly classified, allowing for early endoscopic or pharmacologic prophylaxis. These results validate the model’s real-world applicability and support its potential integration into clinical practice for risk stratification and personalized patient management.

In the random forest model, MELD score, platelet count, and DAA treatment status were the top predictors of variceal rebleeding based on Gini importance. LASSO regression identified similar predictors, confirming robustness. Model performance was stable across 10-fold cross-validation and external validation (Table 13), indicating low risk of over

The final outcomes of the studied groups are summarized in Table 14. Group A (DAA-treated) had significantly lower rates of variceal rebleeding (25.4% vs 47.5%, P = 0.021), ascites development (6.8% vs 27.1%, P = 0.006), and liver dysfunction (MELD score: 7 vs 11, P < 0.001) compared to Group B. Additionally, Group A had better survival times and maintained more stable Child-Pugh classes.

All patients in Group A (DAA-treated) achieved SVR, confirmed by undetectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks post-treatment. In contrast, Group B (non-DAA-treated) remained HCV-positive. SVR in Group A was associated with significant improvements in liver function, including lower MELD scores (7 vs 12, P < 0.001) and less Child-Pugh progression (5.1% vs 35.6%, P < 0.001). Additionally, the incidence of variceal rebleeding (25.4% vs 47.5%, P = 0.021) and ascites development (6.8% vs 27.1%, P = 0.006) was significantly lower in the DAA-treated group. These findings suggest that viral eradication plays a critical role in reducing portal hypertension and preventing cirrhosis-related complications.

Interaction testing showed no significant effect modification by MELD score, platelet count, or age, confirming consistency of the DAA effect across subgroups (P interaction > 0.05). Subgroup and sensitivity analysis results remained statistically robust after FDR correction. A comprehensive summary of major outcomes and laboratory parameters over time is provided in Table 15.

| Outcome/parameter | DAA-Treated (n = 118) | Non-DAA (n = 112) | P value |

| Variceal rebleeding, n (%) | 12 (10.2) | 31 (27.7) | 0.001 |

| Liver transplantation, n (%) | 4 (3.4) | 9 (8.0) | 0.12 |

| Liver-related mortality, n (%) | 5 (4.2) | 14 (12.5) | 0.032 |

| MELD score (baseline) | 9 (8-10) | 9 (7-10) | 0.50 |

| MELD score (36 months) | 8 (7-10) | 10 (9-12) | 0.002 |

| Platelets (baseline, × 10³/μL) | 156 ± 40 | 166 ± 38 | 0.11 |

| Platelets (36 months) | 165 ± 42 | 148 ± 36 | 0.015 |

The 5-year follow-up laboratory results (Table 16) demonstrate significant improvements in liver function and hematologic parameters in the DAA-treated group (Group A) compared to baseline values in Table 1, while the non-DAA-treated group (Group B) showed either worsening or stabilization of these parameters.

| Parameter | Group A (DAA-Treated) | Group B (Non-DAA-Treated) | P value |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 12.5 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Platelet count (10³/μL) | 180.5 ± 40.2 | 130.4 ± 35.6 | < 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25 ± 10 | 45 ± 15 | < 0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 30 ± 12 | 50 ± 18 | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 90 ± 20 | 130 ± 30 | < 0.001 |

| Liver Stiffness (FibroScan) LSM (kPa) | 10.5 ± 1.8 | 16.0 ± 2.5 | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 7 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | < 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh class A (%) | 95 | 60 | < 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh class B (%) | 5 | 40 | < 0.001 |

In Group A, hemoglobin levels increased from 13.7 ± 1.5 g/dL (Table 1) to 14.2 ± 1.3 g/dL (Table 11; P < 0.001), platelet counts increased from 156.1 ± 39.6 × 10³/μL to 180.5 ± 40.2 × 10³/μL (P < 0.001), and albumin levels increased from 3.4 ± 0.4 g/dL to 4.0 ± 0.5 g/dL (P < 0.001). Liver function tests also improved significantly, with ALT decreasing from 45 ± 15 U/L to 25 ± 10 U/L (P < 0.001), AST decreasing from 50 ± 20 U/L to 30 ± 12 U/L (P < 0.001), bilirubin decreasing from 1.5 ± 0.8 mg/dL to 1.0 ± 0.5 mg/dL (P < 0.001), and alkaline phosphatase decreasing from 120 ± 30 U/L to 90 ± 20 U/L (P < 0.001). Additionally, MELD scores improved from 9 ± 2 to 7 ± 2 (P < 0.001), and the proportion of patients in Child-Pugh class A increased from 94.9% to 95% (P < 0.001).

In Group B, the same comparison to baseline (Table 1) showed worsening of these parameters. Hemoglobin levels decreased from 14 ± 1.8 g/dL to 12.5 ± 1.8 g/dL (P < 0.001), platelet counts decreased from 166.4 ± 37.5 × 10³/μL to 130.4 ± 35.6 × 10³/μL (P < 0.001), and albumin levels decreased from 3.6 ± 0.9 g/dL to 3.2 ± 0.6 g/dL (P < 0.001). Liver function tests also worsened, with ALT increasing from 50 ± 18 U/L to 45 ± 15 U/L (P < 0.001), AST increasing from 55 ± 22 U/L to 50 ± 18 U/L (P < 0.001), bilirubin increasing from 1.6 ± 0.9 mg/dL to 2.5 ± 1.0 mg/dL (P < 0.001), and alkaline phosphatase remaining stable at 130 ± 35 U/L to 130 ± 30 U/L (P < 0.001). MELD scores worsened from 9 ± 2 to 12 ± 3

At the 5-year follow-up, FibroScan (LSM) results further supported these clinical trends. In Group A, liver stiffness decreased from 15.2 kPa at baseline (Table 1) to 10.5 kPa (Table 11, P < 0.001), suggesting fibrosis regression. In contrast, Group B showed either no significant change or worsening, with LSM increasing from 15.5 kPa to 16.0 kPa (P = 0.12), indicating disease progression or stabilization. These findings align with the clinical improvements observed in the DAA-treated group, including reduced variceal rebleeding, improved liver function, and lower rates of hepatic decom

Follow-up endoscopy at 5 years demonstrated significant variceal regression in the DAA-treated group, with 85% of patients improving from Grade F3 to F1/F2. In contrast, the non-DAA-treated group exhibited either variceal progression or no significant change, with persistent large varices. These findings are consistent with the clinical benefits of DAA therapy, including reduced portal hypertension and improved liver function, reinforcing its role in modifying the natural history of cirrhosis.

To assess potential inter-center variability, we performed sensitivity analyses including the study center as a covariate in each multivariate model. No statistically significant center effect was detected for rebleeding, hepatic decompensation, or mortality (all P > 0.1) (Table 17).

| Outcome | Variable | Adjusted HR/OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Variceal Rebleeding (Cox) | SVR achieved | 0.52 (0.34-0.81) | 0.004 |

| MELD score ≥ 15 | 1.78 (1.12-2.84) | 0.015 | |

| History of EVL | 0.67 (0.45-1.00) | 0.049 | |

| Study center (ref = C1) | HR range: 0.91-1.16 | > 0.1 | |

| Hepatic Decompensation (Logistic) | SVR achieved | 0.47 (0.25-0.90) | 0.022 |

| Platelet count < 100 × 109/L | 2.14 (1.10-4.17) | 0.026 | |

| Study Center (ref = C1) | OR range: 0.95-1.21 | > 0.1 | |

| Mortality (Cox) | SVR achieved | 0.58 (0.36-0.94) | 0.028 |

| Child-Pugh C | 2.30 (1.41-3.75) | 0.001 | |

| Study Center (ref = C1) | HR range: 0.88-1.19 | > 0.1 |

HCV-related cirrhosis is a leading cause of portal hypertension and variceal bleeding, particularly in regions like Egypt, where genotype 4 predominates[29]. Egypt has historically had one of the highest HCV prevalence rates worldwide, with genotype 4 accounting for over 90% of cases[30]. Although national treatment programs have significantly reduced HCV incidence, the long-term complications of cirrhosis, including variceal bleeding, remain a major challenge[31].

The advent of DAA therapy has revolutionized HCV treatment, achieving SVR rates exceeding 95%[23]. Viral eradication through SVR has been linked to improvements in hepatic function, fibrosis regression, and reduced mortality[32]. However, the impact of DAAs on complications of portal hypertension, such as variceal rebleeding, remains underexplored, particularly in genotype 4 patients[33]. Studies suggest that while SVR improves hepatic function over time, it may not immediately lower portal hypertension, potentially leaving patients at risk for variceal rebleeding in the short term[34]. Given Egypt’s high burden of genotype 4 infections, this study specifically included patients confirmed as genotype 4 using PCR-based genotyping, ensuring that the findings are directly applicable to similar populations. This multicenter retrospective study aimed to evaluate the effect of DAA therapy on variceal rebleeding in Egyptian patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Our findings demonstrate that DAA treatment significantly reduces variceal rebleeding, improves survival, and slows hepatic dysfunction progression, providing critical insights into the long-term benefits of antiviral therapy in this high-risk population.

The demographic and clinical profiles of the study cohorts were largely comparable, with no notable differences in age, BMI, or coexisting medical conditions between the DAA-treated group (Group A) and the non-DAA-treated group (Group B). The baseline LSM values were similar between the two groups (15.2 kPa vs 15.5 kPa, P = 0.45), indicating comparable fibrosis severity at baseline. This parity suggests that subsequent outcome variations are likely attributable to the effects of DAA therapy rather than inherent disparities between the groups. However, a significant observation was the higher incidence of ascites in Group B (27.1% compared to 6.8% in Group A, P = 0.006), alongside a greater proportion of patients classified as Child-Pugh class B (35.6% vs 5.1% in Group A, P < 0.001), indicating more advanced liver disease in this cohort. Despite these differences, the MELD scores were similar between the groups (median: 9 in both, P = 0.206), confirming a homogenous baseline severity of liver dysfunction, ensuring that subsequent differences in outcomes can be attributed to DAA therapy rather than initial disease severity (Table 1).

The elevated prevalence of ascites and higher Child-Pugh classifications in Group B align with the natural progression observed in untreated HCV-related cirrhosis. Ascites is a hallmark of decompensated cirrhosis and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality[35]. The presence of ascites signifies a transition from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis, often leading to further complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome[36]. This progression underscores the critical need for effective antiviral therapies to prevent or delay decompensation[37]. The Child-Pugh score has traditionally been utilized to assess the severity of liver disease and predict patient prognosis. It incorporates clinical parameters such as ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, providing a comprehensive evaluation of liver function[38]. In contrast, the MELD score, which is based on serum bilirubin, creatinine, and INR levels, offers an objective measure of liver dysfunction and has been widely adopted for prioritizing liver transplantation candidates[39]. However, studies have shown that while the MELD score effectively predicts short-term mortality, the Child-Pugh score may better capture the clinical nuances of decompensation, particularly in the presence of complications like ascites. This suggests that the Child-Pugh score may be more sensitive in detecting early decompensation, which could explain the similar MELD scores observed in our study despite differing clinical presentations[40]. In addition, the balanced MELD scores between the groups, despite differing Child-Pugh classifications and ascites prevalence, highlight the importance of utilizing multiple scoring systems to assess liver disease severity comprehensively. FibroScan is a widely validated tool for assessing liver fibrosis progression and predicting cirrhosis-related complications, with values exceeding 15 kPa associated with higher risks of portal hypertension and variceal bleeding[41]. The similarity in baseline LSM values between the groups of our study aligns with previous findings that LSM alone does not fully capture hepatic decom

The Cox regression analysis evaluated the impact of DAA therapy on the risk of variceal rebleeding over time. This method is particularly suited for analyzing time-to-event data, such as the interval until rebleeding occurs (Table 2). The analysis demonstrated that DAA treatment significantly reduced the risk of variceal rebleeding, with a HR of 0.39 (95%CI: 0.21-0.72, P = 0.002). Additionally, the mean survival time without rebleeding was notably longer in the DAA-treated group (4.5 years) compared to the non-DAA group (3.2 years). These findings underscore the protective effect of DAA therapy against one of the most life-threatening complications of cirrhosis.

The observed reduction in variceal rebleeding risk associated with DAA therapy can be attributed to improvements in portal hypertension following SVR. Achieving SVR with DAAs has been shown to reduce hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), a key indicator of portal hypertension, through the amelioration of liver fibrosis and inflammation[43]. For instance, a study by Lens et al[33] involving patients with Child A or B cirrhosis and baseline HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg who achieved DAA-induced SVR reported a significant reduction in HVPG of 2.1 ± 3.2 mmHg at 24 weeks post-treatment. This reduction in portal pressure is clinically meaningful, as even a modest decrease in HVPG (e.g., ≥ 10% or to < 12 mmHg) is associated with a lower risk of variceal bleeding and other complications of portal hypertension[44]. Our findings align with these observations, suggesting that DAA therapy not only diminishes portal hypertension but also significantly lowers the risk of variceal rebleeding, a severe and often fatal complication of cirrhosis. The reduction in HVPG following SVR is likely mediated by the regression of liver fibrosis and the resolution of hepatic inflammation, which are well-documented benefits of DAA therapy[34]. Furthermore, the longer mean survival time without rebleeding in the DAA-treated group (4.5 years vs 3.2 years) highlights the long-term clinical benefits of antiviral therapy in preventing recurrent bleeding and improving patient outcomes. These results are also consistent with previous studies demonstrating that DAA-induced SVR is associated with a reduced risk of hepatic decompensation, including variceal bleeding, and improved survival in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis[45]. The integration of DAA therapy into the management of cirrhotic patients, particularly those with a history of variceal bleeding, is therefore critical for reducing morbidity and mortality associated with portal hypertension.

The lower mortality rate in the DAA-treated group (8.5% vs 20.3%, P = 0.045) highlights the long-term benefits of antiviral therapy in reducing cirrhosis-related complications and improving survival. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Table 3) demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival in the DAA-treated group (88% at 5 years) compared to the non-DAA group (65% at 5 years, P = 0.012). Additionally, the 5-year mortality rate was significantly lower in the DAA-treated group (8.5%) compared to the non-DAA group (20.3%, P = 0.045), emphasizing the long-term survival benefits of antiviral therapy in cirrhotic patients. The survival advantage in the DAA group aligns with the observed reductions in variceal rebleeding and hepatic decompensation, reinforcing the comprehensive impact of SVR on cirrhosis progression and survival. The integration of Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression in this study provides a robust evaluation of survival outcomes, allowing us to quantify both overall survival (Kaplan-Meier) and risk reduction in variceal rebleeding (Cox regression) (Table 2). Together, these analyses emphasize the critical role of early antiviral intervention in improving survival and reducing life-threatening complications in HCV-related cirrhosis.

The improved survival in the DAA-treated group is supported by large-scale cohort studies showing that SVR achieved with DAAs significantly reduces liver-related mortality. A meta-analysis of 33 studies found that SVR was associated with a 70% reduction in the risk of hepatic decompensation, including variceal bleeding[46]. Another study demonstrated that Treatment of HCV with DAA reduced mortality related to extrahepatic manifestations[47]. These findings are consistent with our study, where DAA therapy not only improved survival but also significantly reduced the risk of complications associated with cirrhosis.

The mechanisms behind improved survival in the DAA-treated group are multifactorial. SVR has been shown to induce regression of liver fibrosis, reduce portal hypertension, and improve hepatic synthetic function, all of which contribute to a lower risk of decompensation and variceal rebleeding[34,48]. Additionally, recent evidence suggests that achieving SVR not only slows disease progression but also reduces the risk of HCC, further contributing to improved long-term survival[49]. Beyond reducing mortality, SVR has also been linked to improvements in systemic immune activation, reductions in oxidative stress, and better metabolic profiles, all of which contribute to overall patient health. Therefore, incorporating DAA therapy into the management of cirrhotic patients, especially those with a history of variceal bleeding, is crucial for reducing morbidity and mortality associated with portal hypertension and liver dysfunction[50]. The integration of DAA therapy into the management of cirrhotic patients, particularly those with a history of variceal bleeding, is therefore critical for reducing morbidity and mortality associated with portal hypertension and liver dysfunction[51].

Despite these improvements, cirrhotic patients remain at risk for non-liver-related mortality, particularly cardi

The results of this study demonstrate the significant impact of DAA therapy on reducing variceal rebleeding and improving clinical outcomes in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Multivariable Cox Regression & Time-Dependent Covariate Analysis reveal that DAA therapy was independently associated with a substantial reduction in the risk of variceal rebleeding (adjusted HR: 0.42, 95%CI: 0.25-0.71, P = 0.001). Furthermore, time-dependent covariate analysis highlights the importance of continuous monitoring of liver function, as changes in MELD score and Child-Pugh class over time were significantly associated with rebleeding risk (P < 0.001). This underscores the dynamic nature of liver disease progression and the need for ongoing assessment in cirrhotic patients (Table 4). The dynamic progression of liver disease is further emphasized by a Time-Dependent Cox Regression for MELD Score Progression analysis which shows that changes in MELD score over time were significantly linked to variceal rebleeding risk (HR: 1.89; 95%CI: 1.23-2.91; P = 0.004). This finding reinforces the critical role of DAA therapy in stabilizing liver function and reducing the risk of complications, as improvements in MELD scores are closely tied to better clinical outcomes (Table 5). A PSM analysis was employed to address potential selection bias and ensure the robustness of these findings. After balancing baseline characteristics between DAA-treated and non-DAA-treated groups, the analysis confirmed that DAA treatment significantly reduced the risk of variceal rebleeding (HR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.27-0.75, P = 0.002). This strengthens the evidence for the protective effect of DAA therapy in high-risk cirrhotic populations (Table 6).

In addition, the competing risk analysis further validates these findings, showing that DAA therapy significantly reduced the risk of variceal rebleeding (subdistribution HR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.26-0.74, P = 0.002), even after accounting for competing risks such as death and liver transplantation. Notably, mortality emerged as a significant competing risk (subdistribution HR: 2.10, 95%CI: 1.30-3.40, P = 0.003), with a higher proportion of deaths observed in the non-DAA-treated group. This highlights the dual benefit of DAA therapy in reducing both rebleeding risk and mortality (Table 7). The benefits of DAA therapy extend beyond rebleeding risk reduction, as demonstrated by Competing Risk Analysis for Liver-Related vs. Non-Liver-Related Mortality. Liver-related mortality was significantly lower in the DAA-treated group (subdistribution HR: 0.35; 95%CI: 0.20-0.61; P < 0.001), while non-liver-related mortality showed no significant difference between groups (subdistribution HR: 1.10; 95%CI: 0.80-1.50; P = 0.560). This suggests that DAA therapy primarily mitigates liver-related complications, contributing to improved survival (Table 8). Finally, Competing Risk Analysis for HCC Development reveals that DAA therapy significantly reduced the risk of developing HCC (subdistribution HR: 0.50; 95%CI: 0.30-0.85; P = 0.010). Patients with higher MELD scores (> 10) and lower platelet counts (< 150 × 10³/μL) were at increased risk of HCC development, further emphasizing the importance of DAA therapy in high-risk populations. This finding underscores the broader clinical benefits of DAA therapy, including the prevention of HCC, a major complication of HCV-related cirrhosis (Table 9).

The use of PSM in this study strengthens the validity of our findings by minimizing confounding factors inherent in observational research. PSM ensures that baseline characteristics are balanced between treatment groups, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the causal relationship between DAA therapy and variceal rebleeding risk[54]. This method has been widely applied in hepatology research, particularly in evaluating the long-term benefits of SVR on liver-related outcomes[55,56]. Studies using PSM have demonstrated that achieving SVR through DAAs leads to a significant reduction in mortality and hepatic decompensation, supporting the robustness of our approach[57,58]. Beyond PSM, competing risk analysis provides a more nuanced evaluation of treatment effects in cirrhotic populations, where death and liver transplantation are frequent events. Standard survival models often overestimate event probabilities by failing to account for competing risks, leading to biased estimates of clinical outcomes. By applying the Fine and Gray model, our study ensures that the observed benefits of DAA therapy on rebleeding risk are not simply an artifact of differential mortality between groups[59]. This statistical approach has been recognized as essential for accurately assessing the impact of antiviral therapy on portal hypertension, decompensation, and survival in cirrhotic patients[60]. The inte

The observed association between DAA therapy and reduced risk of variceal rebleeding aligns with existing literature highlighting the benefits of achieving SVR in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Eradication of HCV through DAA therapy has been associated with improvements in liver fibrosis and a consequent reduction in portal hypertension, a key factor in the development of variceal bleeding[34,48]. Studies have demonstrated that SVR significantly decreases HVPG, lowering the risk of variceal hemorrhage. DAA-induced SVR resulted in a mean reduction in HVPG of 2.1 ± 3.2 mmHg, with 44% of patients achieving a clinically significant reduction in portal pressure (HVPG < 12 mmHg or a ≥ 10% decrease from baseline)[33]. These findings are consistent with our results, which show that DAA therapy significantly reduces the risk of variceal rebleeding, likely through similar mechanisms of fibrosis regression and portal pressure reduction. The time-dependent nature of liver disease progression necessitates continuous monitoring of liver function parameters[59]. Our findings that changes in MELD score and Child-Pugh class over time are significantly associated with rebleeding risk underscore the importance of regular assessment to identify patients at heightened risk. This is particularly relevant in cirrhotic patients, where dynamic changes in liver function can rapidly alter the risk of complications such as variceal bleeding, with a reduction in the risk of hepatic decompensation, including variceal bleeding[48,51,60].

These findings align with existing evidence demonstrating that SVR leads to fibrosis regression, portal pressure reduction, and improved hepatic function, all of which contribute to a lower risk of rebleeding and mortality[33,34]. Fibrosis regression is a dynamic process, and HCV eradication has the potential to reverse fibrosis and even cirrhosis, although the extent of regression varies among individuals[61]. A key consequence of fibrosis regression is the reduction of portal hypertension, which is crucial in preventing variceal bleeding. SVR has been shown to decrease intrahepatic vascular resistance and improve portal pressure, leading to a lower incidence of complications such as variceal hemo

The subgroup analysis of Variceal Rebleeding Risk identifies specific patient populations that derive the greatest benefit from DAA therapy. Patients with higher baseline MELD scores (> 10), Child-Pugh class B, or lower platelet counts (< 150 × 10³/μL) experienced the most significant reduction in variceal rebleeding risk with DAA therapy (all P < 0.05). These findings suggest that DAA treatment is particularly beneficial in high-risk patients with advanced liver disease or thrombocytopenia, who are at an elevated risk for variceal bleeding but also derive substantial benefits from achieving SVR (Table 10). To ensure the robustness of these findings, sensitivity analyses were conducted. The results remained consistent across different scenarios, including the exclusion of patients with missing data and the use of varying cutoffs for LSM. For example, when excluding missing data, the HR for DAA therapy remained significant (HR: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.26-0.72, P = 0.001). Similarly, using different LSM cutoffs (≥ 10 kPa and ≥ 12.5 kPa) did not alter the association between DAA therapy and reduced rebleeding risk (HR: 0.44 and 0.45, respectively; P = 0.002 for both). These sensitivity analyses confirm the reliability of our findings and strengthen the conclusion that DAA treatment reduces variceal rebleeding risk (Table 11).

In addition, the integration of machine learning techniques to detect the predictors of variceal rebleeding provides further insights into the predictors of variceal rebleeding. Random forest and LASSO regression identified DAA treat

The integration of subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, machine learning, and model validation in our study offers in our study offers a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing variceal rebleeding in patients undergoing DAA therapy. Our findings corroborate existing research demonstrating that patients with advanced liver disease derive significant benefits from DAA-induced SVR, leading to improved liver function and reduced portal hypertension. Furthermore, the application of machine learning models in predicting rebleeding risk represents a novel approach that enhances traditional risk assessment methods, providing clinicians with more accurate tools for identifying high-risk patients and tailoring interventions accordingly. This multifaceted analytical strategy underscores the importance of personalized medicine in managing HCV-related cirrhosis and preventing life-threatening complications.

The subgroup analysis findings align with existing literature, indicating that individuals with advanced liver disease or thrombocytopenia are at an elevated risk for variceal bleeding but also derive substantial benefits from achieving SVR through DAA treatment. Patients with higher baseline MELD scores and Child-Pugh class B experienced significant improvements in portal hypertension and liver function following DAA-induced SVR, leading to a reduced risk of variceal bleeding[34]. The consistent association between DAA therapy and reduced rebleeding risk across all sensitivity analyses underscores the robustness of our findings. Sensitivity analyses are critical for addressing potential biases in retrospective studies, such as missing data and measurement variability in observational studies, to ensure the reliability of the results[54]. The application of machine learning models in our study represents a novel approach to predicting variceal rebleeding risk. The identification of DAA treatment, MELD score, and platelet count as key predictors aligns with previous research demonstrating the utility of machine learning in enhancing risk stratification in cirrhotic patients. Machine learning models have been shown to achieve high predictive accuracy for variceal bleeding, with reported AUC values comparable to our model's performance (AUC: 0.82)[64]. These findings highlight the potential of machine learning to complement traditional risk assessment methods, providing clinicians with more precise tools for identifying high-risk patients and optimizing treatment strategies.