Published online Oct 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i10.109770

Revised: June 26, 2025

Accepted: September 29, 2025

Published online: October 27, 2025

Processing time: 145 Days and 4.5 Hours

In recent years, the number of pediatric patients with unexplained liver disease has been increasing. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) technology has played a significant role in the diagnosis; however, related studies remain limited.

To investigate the clinical characteristics and genetic causes of unexplained pediatric liver disease to improve the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

Eighty children with unexplained liver disease were divided into two groups: The liver enzyme elevation group (Group A) and the cholestasis group (Group B). Children with both elevated liver enzymes and cholestasis were assigned to Group B. The clinical characteristics of the patients were retrospectively summa

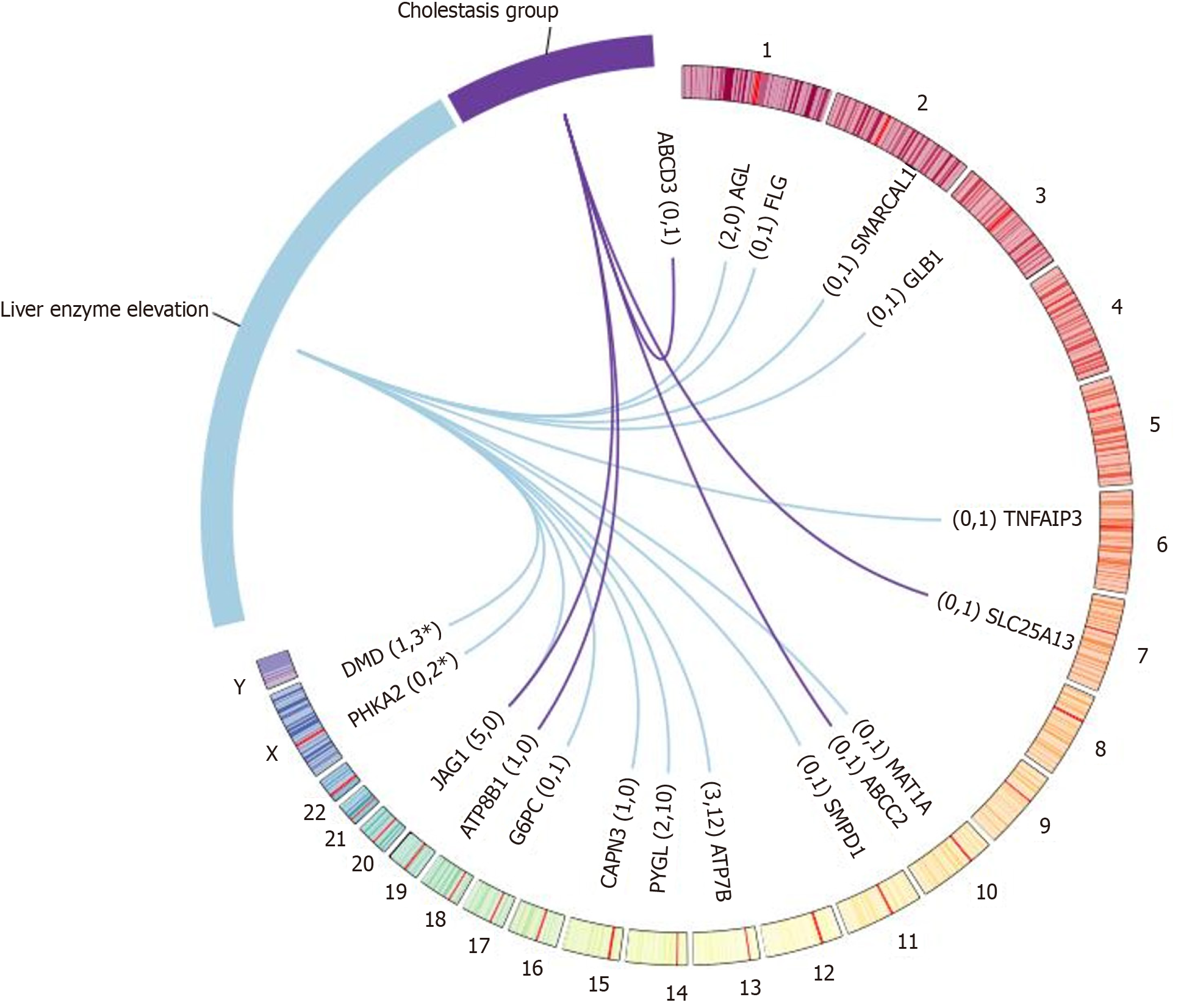

Genetic results were obtained in 46 patients (46/80, 57.5%), including 38 in Group A (38/65, 58.5%) and 8 in Group B (8/15, 53.3%). A total of 53 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 42 patients (42/80, 52.5%), including 40 previously reported variants and 13 novel variants. Seven variants of uncertain significance were identified in 7 patients (7/80, 8.8%), of which 4 were novel variants. A total of 19 gene mutations were identified: 2 cases of AGL, 15 cases of ATP7B, 1 case of CAPN3, 4 cases of DMD, 1 case of FLG, 1 case of G6PC, 5 cases of JAG1, 2 cases of PHKA2, 2 cases of PYGL, 1 case of SMARCAL1, 1 case of SMPD1, 1 case of TNFAIP3, 1 case of GLB1, and 1 case of MAT1A in Group A; and 1 case of SLC25A13, 3 cases of JAG1, 1 case of ATP8B1, 1 case of ABCC2, 1 case of ABCD3, and 1 case of 45X in Group B.

WES significantly improved the etiological diagnosis of unexplained pediatric liver disease, helping guide individualized treatment and improve prognosis.

Core Tip: In recent years, the number of pediatric patients with unexplained liver disease has been increasing. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) technology has played a significant role in the diagnosis; however, related studies remain limited. We found that WES significantly increased the diagnosis rate of liver diseases of unknown cause in children, guided personalized treatment, and improved prognosis. The mutation spectra of genes such as ATP7B and JAG1 provide important references for the molecular diagnosis of inherited liver diseases in Chinese children. In the future, functional studies and multi-omics integration will be required to elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms of novel variants and to advance the application of precision medicine in the field of pediatric hepatology.

- Citation: Chen Y, Wang ZY, Chen BQ, Qi YJ, Liu HY, Shi WX, Guo L, Liu Z, Sun LF. Clinical characteristics and genetic causes of unexplained pediatric liver disease. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(10): 109770

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i10/109770.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i10.109770

In recent years, with the advancement of medical services, parents have become increasingly concerned regarding the physical health of their children. Physical examinations for admission to kindergartens and schools have become more common, and the number of children under the age of 16 years seeking medical treatment for liver damage has risen. The cause of liver damage in a large proportion of these children is unknown, with hereditary liver diseases being the main cause[1,2]. Currently, whole-exome sequencing (WES) is widely used in clinical practice and has played a crucial role in diagnosing unexplained liver damage in children. The genetic results can accurately identify the type of disease, and timely diagnosis allows for targeted treatment, leading to better outcomes. The present study was conducted in order to improve the diagnosis and treatment of children with unexplained liver damage.

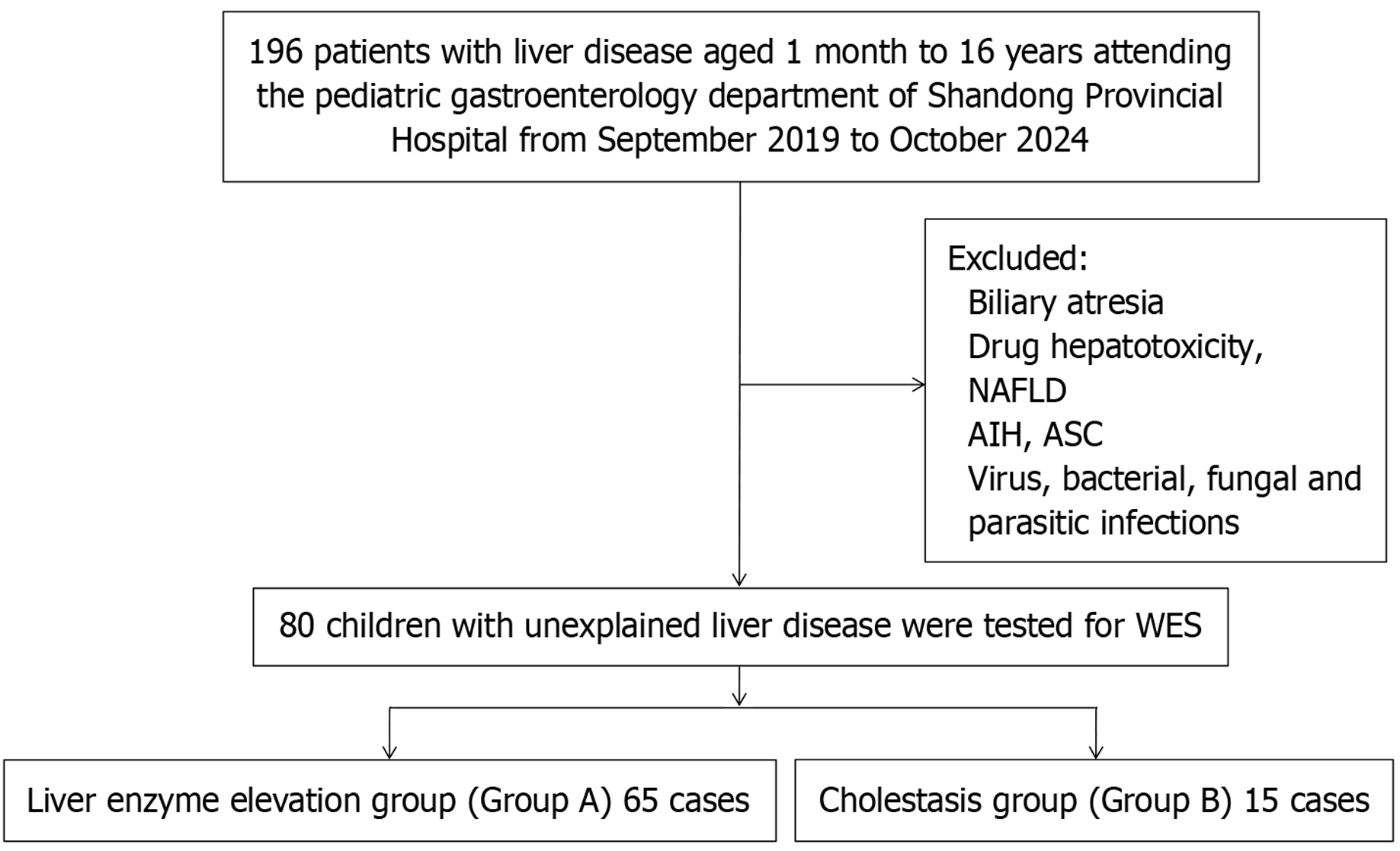

Patients aged from one month to 16 years with liver disease were retrospectively recruited from the Pediatric Gastroenterology Department of Shandong Provincial Hospital from September 2019 to October 2024. Exclusion criteria included: Biliary atresia, drug-induced hepatotoxicity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis, and infectious causes that could lead to elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, such as viral hepatitis (A, B, C, and E), as well as other viral infections like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus, human herpesviruses (HHV6, HHV7, HHV8), herpes simplex virus, and bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections. All children had completed biochemical tests for liver injury markers, including ALT, AST, and alkaline phosphatase. Children with unexplained liver disease were divided into two groups: The liver enzyme elevation group (Group A) and the cholestasis group (Group B). Elevated liver enzymes were defined as increased levels of aminotransferases (ALT and AST)[3]. Cholestasis was defined as a direct bilirubin level above 1.0 mg/dL[4].

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital (SWYX: No. 2022-210). Informed written consent was obtained from at least one parent.

Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes isolated from peripheral blood samples of patients and their parents using the QIAamp DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Shanghai, China). Whole-genome DNA was fragmented into 150-200 bp fragments by enzymatic digestion. Exons of genes, along with 20 bp upstream and downstream flanking regions, were enriched using biotinylated capture probes (McKinnon, Beijing, China) to construct targeted genomic libraries. Paired-end sequencing (approximately 150 bp) was performed using the DNBSEQ-T7 sequencing platform (BGI, Shenzhen, China). FASTQ files were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA software (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/), and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and Indel variants were identified using Sentieon software (https://www.sentieon.com/) with parameter-driven workflows. Identified SNPs and Indels were annotated using ANNOVAR (http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/Latest/), with reference to databases including 1000 Genomes, ESP6500, dbSNP, ExAC, and HGMD. Pathogenicity was predicted using tools such as REVEL, MutationTaster, SIFT, PolyPhen-2, SPIDEX, and dbscSNV.

According to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics[5], the pathogenicity of variants was evaluated and classified into five categories: Pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), variants of uncertain significance (VUS), Likely Benign, and Benign. The variants classified as P/LP related to disease were defined as P variants.

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD or as median with interquartile range (IQR), while qualitative data are expressed as percentages or proportions. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States).

From September 2019 to October 2024, a total of 216 children with liver disease, ranging in age from one month to 16 years, were enrolled from the Pediatric Gastroenterology Department of Shandong Provincial Hospital. After excluding 136 cases (8 cases of biliary atresia, 9 cases of drug-induced liver disease, 23 cases of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, 1 case of AIH, 63 cases of EBV infection, 17 cases of CMV infection, and 15 cases of mycoplasma infection), 80 children remained in the study, with 65 children in group A and 15 children in group B (Figure 1).

At the time of enrollment, 72.5% (58/80) of the patients were under six years of age, and 42.5% (34/80) were under two years of age. The median age at enrollment was 36.0 months (IQR: 8.8, 73.5 months), and the median duration of liver disease was 2.0 months (IQR: 1.0, 6.0 months). No consanguineous marriages were found in the cohort. Detailed patient information for both groups is provided in Table 1. All patients survived during the follow-up; and one underwent liver transplantation.

| Characteristics | Group A (n = 65) | Group B (n = 15) |

| Male gender | 36 (55.4) | 6 (40.0) |

| Age (median, IQR), (months) | 36.0 (11.0, 84.0) | 13.0 (4.0, 49.5) |

| History of liver disease (median, IQR), (months) | 2.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) |

| Loss to follow-up | 5 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Liver function recovery | 48 (73.8) | 7 (46.7) |

| liver transplantation | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) |

Genetic results were found in 46 patients (46/80, 57.5%), including 38 patients (38/65, 58.5%) in Group A and 8 patients (8/15, 53.3%) in Group B. A total of 53 P/LP variants were identified in 42 patients (42/80, 52.5%), including 40 reported variants and 13 novel variants.

The reported variants included 17 missense variants, 5 splicing variants, 4 nonsense variants, 3 deletion variants, 2 whole-frame variants, 3 frame-shift variants, 1 deletion-insertion variant, 1 duplication variant, 2 synonymous variants and 1 case of 45X. The novel variants included 5 frameshift variants, 1 missense variants, 4 nonsense variants, 2 splicing variants and 1 deletion variant. Seven VUS variants were identified in seven patients (7/80, 8.8%), including 5 missense variants, 1 synonymous variant, 1 intronic variant, and 4 novel variants. Some of these VUSs may potentially be reclassified as LP if parental and additional family member samples are available for co-segregation studies. Detailed information on all variants is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

A total of 19 gene mutations were identified in 46 patients, including 2 AGL, 15 ATP7B, 1 CAPN3, 4 DMD, 1 FLG, 1 G6PC, 5 JAG1, 2 PHKA2, 2 PYGL, 1 SMARCAL1, 1 SMPD1, 1 TNFAIP3, 1 GLB1, and 1 MAT1A in Group A. Gene mutations in Group B included 1 SLC25A13, 3 JAG1, 1 ATP8B1, 1 ABCC2, 1 ABCD3, and 1 45X (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

According to the health industry standard WS/T 780-2021, Reference Intervals for Common Clinical Biochemical Tests in Children, issued by the National Health Commission of China[6], the reference intervals for ALT, AST, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) in children vary by age and gender, as detailed in Table 2[6]. ALT, AST, and GGT levels were classified as follows: (+) if less than 3 times the upper limit of the reference range, (++) if between ≥ 3 and < 6 times, and (+++) if ≥ 6 times. Conjugated bilirubin (CBIL) levels exceeding 17.1 μmol/L were similarly categorized: (+) if less than 3 times higher, (++) if between ≥ 3 and < 6 times, and (+++) if ≥ 6 times higher. The results are presented in Table 2.

| Items | Age | Reference interval, U/L | |

| Male | Female | ||

| Alanine transaminase | 28 days to < 1 year | 8-71 | |

| 1 year to < 2 years | 8-42 | ||

| 2 years to < 13 years | 7-30 | ||

| 13 to 18 years | 7-43 | 6-29 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 28 days to < 1 year | 21-80 | |

| 1 year to < 2 years | 22-59 | ||

| 2 years to < 13 years | 14-44 | ||

| 13 to 18 years | 12-37 | 10-31 | |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase | 28 days to < 6 months | 9-150 | |

| 6 months to < 1 year | 6-31 | ||

| 1 year to < 13 years | 5-19 | ||

| 13 to 18 years | 8-40 | 6-26 | |

Early diagnosis using WES impacted the clinical management of 39 patients and has the potential to improve patient outcomes. Following diagnosis, 15 patients with Wilson's disease (WD) caused by mutations in the ATP7B gene received treatment with D-penicillamine, zinc supplements, vitamin B6, a low-copper diet, and other supportive therapies. During follow-up, liver function normalized in all patients. Six patients with significantly increased GGT and two patients with normal GGT lacked specific clinical symptoms (special facial features in 5 cases, butterfly vertebrae in 2 cases, posterior embryotoxon in 2 cases, and heart murmurs in 3 cases). However, due to the presence of P mutations in the JAG1 gene and consistent findings from multiple auxiliary examinations, these patients were ultimately diagnosed with Alagille syndrome. Among them, three cases were in the cholestasis group, and none underwent liver transplantation during the follow-up period.

One patient with glycogen storage disease (GSD)-Ia caused by a G6PC mutation, two patients with GSD-III caused by AGL mutations, two patients with GSD-VI caused by PYGL mutations, and two patients with GSD-IXa1/IXa2 caused by PHKA2 mutations were managed with dietary interventions and the use of uncooked cornstarch to maintain glucose homeostasis. No cases of liver failure were observed during the follow-up period.

One patient with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy caused by a CAPN3 mutation, one patient with Niemann-Pick disease caused by a SMPD1 mutation, one patient with methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency caused by a MAT1A mutation, one patient with Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia caused by a SMARCAL1 mutation, and one patient with citrin deficiency caused by a SLC25A13 mutation all had persistently elevated transaminase levels during the follow-up period. Four patients with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy (DMD/BMD) caused by DMD mutations were followed up, and in two of them, transaminase levels returned to normal during the follow-up period. One patient with Familial Behçet-Like Autoinflammatory Syndrome caused by a TNFAIP3 mutation received infliximab treatment and one patient with hereditary atopic dermatitis caused by a FLG mutation received topicalcorticosteroid treatment. Both patients showed normalization of transaminase levels during the follow-up period.

One patient with Dubin-Johnson syndrome (DJS) caused by an ABCC2 mutation showed normalization of transaminase levels during the follow-up period but experienced intermittent jaundice. One patient with Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis Type 1 (PFIC1) caused by an ATP8B1 mutation underwent liver transplantation at the age of 1.5 years. During the follow-up period, the patient exhibited extrahepatic clinical manifestations including growth retardation, pancreatitis, and hypothyroidism. One patient with GM1 gangliosidosis caused by a GLB1 mutation was lost to follow-up.

It is worth noting that one patient with cholestasis presented with hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, and pruritus. Biochemical features included elevated transaminases, CBIL, and total serum bile acids, while GGT levels remained normal. Liver transient elastography showed an average liver stiffness of 9.2 kPa, indicating mild to moderate fibrosis. Genetic sequencing analysis identified suspected P variants associated with the disease phenotype. Compound heterozygous mutations were found in the ABCD3 gene at exon 10: C.846C>G (p.Y282Ter) and intron 21: C.1845+9G>A (p.?). Both variants have not been previously reported.

Pediatric liver disease is a common disease in children, including hepatocellular damage and cholestasis[7,8]. With the increasing application of molecular diagnostic technology in the diagnosis of pediatric diseases[9-11], more and more non-infectious factors are considered to be the main cause of liver dysfunction or cholestasis in children, and hereditary liver diseases caused by genetic defects are increasing[1,12,13]. WES includes sequencing of all 20000 protein-coding genes in humans. Currently, there are few studies on the application of WES in the diagnosis of children with unexplained liver disease.

In this study, WES was performed on 80 pediatric patients with unexplained liver disease. Genetic analysis revealed that 57.5% (46/80) of the patients carried P/LP variants, further supporting the critical role of genetic factors in pediatric liver disease[1]. This proportion is highly consistent with recent findings from international multicenter studies (55.8%)[8], suggesting the widespread presence of inherited liver diseases among children with unexplained liver dysfunction. Notably, this study is the first to systematically characterize the mutation spectrum of genes such as ATP7B, JAG1, and AGL in a Chinese pediatric population, and identified 13 novel variants, including compound heterozygous mutations in the ABCD3 gene (exon 10: C.846C>G and intron 21: C.1845+9G>A), providing new insights for the molecular diagnosis of inherited liver diseases.

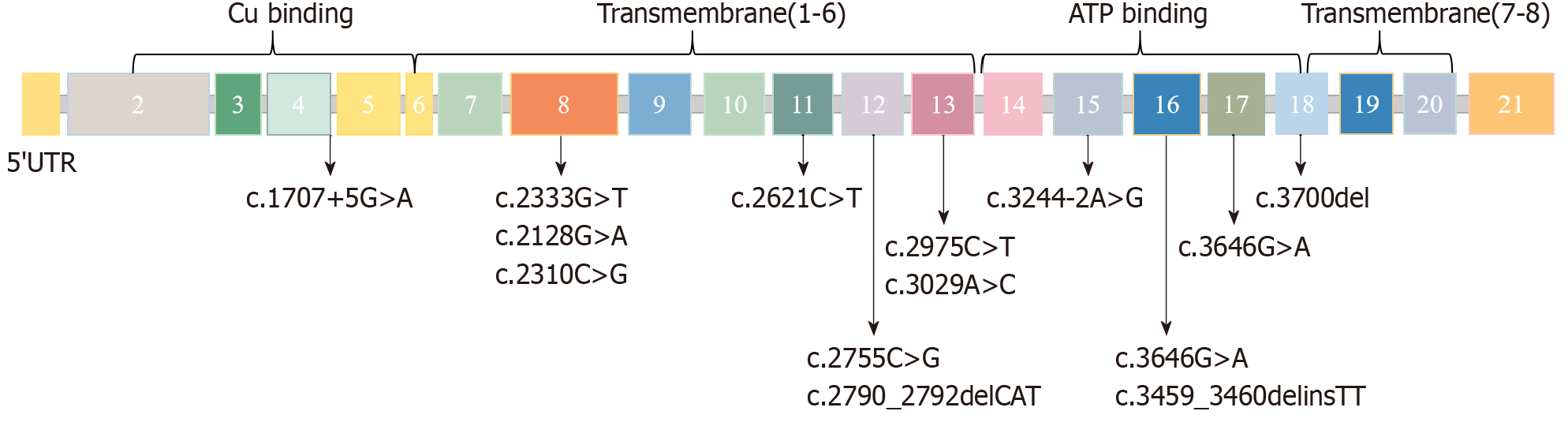

WD caused by ATP7B gene mutations was the most common genetic cause in this cohort (15/80, 18.8%). The age at diagnosis (7.0 ± 3.5 years) was significantly earlier than that in the French cohort (10.7 ± 4.2 years)[14]. This may be due to the early application of WES. ATP7B mutations lead to hepatic copper accumulation and oxidative damage by interfering with the function of copper transporters[15,16]. The c.2333G>T (R778 L) (Asian hotspot mutation) and c.3207C>A (H1069Q) (European hotspot mutation) found in this study affect copper transmembrane transport and ATP binding domain function, respectively[17,18], which is consistent with previous mechanistic studies. The schematic diagram of the ATP7B gene mutation sites in this study is shown in Figure 3. In the era of personalized medicine, it is essential to incorporate the ATP7B genotype into the management of patients with liver WD[19]. Following early diagnosis, in this study, the children's liver function returned to normal after copper chelators (such as D-penicillamine) and low-copper diet intervention, highlighting the guiding value of genetic diagnosis for precision treatment.

JAG1 mutations were identified in both Group A (5 cases) and Group B (3 cases) in our study, aligning with previous literature[8] which highlights Alagille syndrome as the second most common cause of cholestatic liver disease. Approximately 94% to 95% of Alagille syndrome cases are caused by mutations in the JAG1 gene, while 2% to 4% are attributed to NOTCH2 mutations[20,21]. No NOTCH2 mutations were detected in this study. Alagille syndrome is a multisystem disorder that impacts the liver, heart, eyes, bones, kidneys, and vascular system, presenting with a wide range of phenotypic variations[22,23]. Studies investigating the correlation between specific genetic P variations and phenotypic manifestations have yet to establish a clear link between gene mutations and clinical disease outcomes[24,25]. Among the six children with Alagille syndrome in this cohort, GGT levels were markedly elevated in four cases; however, two children carrying JAG1 mutations had normal GGT levels, underscoring the need for clinicians to be vigilant for atypical presentations. Of the JAG1 mutations identified, four were de novo, and four were inherited from asymptomatic parents. All affected children were managed with nutritional support and bile acid modulation therapy (ursodeoxycholic acid and cholestyramine), and none progressed to liver transplantation. These findings suggest that genetic testing can play a critical role in refining clinical decision-making and management strategies[26].

Mutations in GSD-related genes (G6PC, AGL, PYGL, PHKA2) accounted for 8.8% (7/80) and were closely associated with elevated liver enzymes[2]. Maintaining blood glucose homeostasis through dietary adjustments (such as raw corn starch) effectively prevented liver failure[27], which is consistent with the management strategy recommended by international guidelines[28].

The discovery of gene mutations in SLC25A13 (Citrin deficiency), ATP8B1 (PFIC1), and ABCC2 (DJS) in the cholestatic group is consistent with the complex etiology of cholestatic liver disease reported in the literature[8,29]. Among them, one child with ATP8B1 mutation had extrahepatic manifestations (pancreatitis and hypothyroidism), suggesting that PFIC1 requires multi-system management[30].

It is noteworthy that a cholestatic child carrying a novel ABCD3 mutation showed a unique phenotype (liver fibrosis with normal GGT). Studies have found that ABCD3 knockout mice show significant accumulation of bile acid intermediates and that ABCD3 is associated with a novel bile acid biosynthesis defect[31,32].

This study showed that WES increased the diagnostic rate to 57.5%, which is higher than a previous literature report (approximately 50%)[26]. In particular, for atypical or overlapping phenotypes (such as muscular dystrophy combined with liver damage), WES can simultaneously identify genetic causes of multi-system involvement (such as DMD, CAPN3 mutation). However, only VUSs were detected in 8.8% (7/80) of cases, some of which may not be upgraded to P due to insufficient family data. In addition, a child with FLG mutation had atopic dermatitis and liver damage. The P mechanism of this disorder is still unclear and needs to be combined with skin-liver axis mechanism research[33].

The single-center design and relatively small sample size of this study may limit the generalizability of the results. Since WES does not capture non-coding regions (such as introns and intergenic regions) that may have important regulatory functions and is unable to detect structural variations or chromosomal rearrangements, some genetic disorders may be missed or insufficiently diagnosed, which adds to the limitations of this study[34,35]. In addition, the number of cases involving certain rare genes (such as SLC25A13 and SMARCAL1) was limited, highlighting the need for multicenter collaboration to enhance the genotype-phenotype database. Functional validation of VUS and novel mutations will be a key focus in the future-for example, through the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to construct mutant cell models[36] or RNA sequencing to evaluate splicing effects[37]. Moreover, integrating metabolomics (such as bile acid profiling) and proteomics data could further elucidate downstream pathway abnormalities associated with these mutations[4].

WES has significantly improved the diagnostic yield for unexplained pediatric liver diseases, guiding personalized treatment and improving prognosis. The mutation spectra of genes such as ATP7B and JAG1 provide important references for the molecular diagnosis of inherited liver diseases in Chinese children. In the future, functional studies and multi-omics integration will be essential to elucidate the P mechanisms of novel variants and to advance the application of precision medicine in the field of pediatric hepatology.

| 1. | Li LT, Wang JS. [Common childhood genetic liver disease]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2021;59:615-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu YC, Xiang XL, Yong JK, Li M, Li LM, Lv ZC, Zhou Y, Sun XC, Zhang ZJ, Tong H, He XY, Xia Q, Feng H. Immune remodulation in pediatric inherited metabolic liver diseases. World J Hepatol. 2024;16:1258-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vimalesvaran S, Samyn M, Dhawan A. Liver disease in adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2023;108:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen HL, Wu SH, Hsu SH, Liou BY, Chen HL, Chang MH. Jaundice revisited: recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of inherited cholestatic liver diseases. J Biomed Sci. 2018;25:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26738] [Cited by in RCA: 24766] [Article Influence: 2251.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. WS/T 780-2021 Reference Intervals for Commonly Used Biochemical Test Items in Pediatric Clinical Practice. 2021. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/wsbzxx/wsbz.shtml. |

| 7. | Zou YG, Wang H, Li WW, Dai DL. Challenges in pediatric inherited/metabolic liver disease: Focus on the disease spectrum, diagnosis and management of relatively common disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2114-2126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fang Y, Yu J, Lou J, Peng K, Zhao H, Chen J. Clinical and Genetic Spectra of Inherited Liver Disease in Children in China. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:631620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gan C, Nie Y, Zheng G. A novel mutation site in STAT in a chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis pediatric patient with disseminated cryptococcosis: Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Discov. 2024;2:e58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang M, Xiao J, Liu X, Zhang Z, Li X, Shi M, Wang P, Zhang X, Yao H. Primary lymphoma of bone in children: Three case reports and literature review. Pediatr Discov. 2023;1:e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xianhao W, Hongcheng Q, Meiling L, Xianmin G. Novel homozygous mutation in the FANCA gene (c.2222G>A) in a Chinese girl of Fanconi anemia. Pediatr Discov. 2024;2:e63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang J, Yang Y, Gong JY, Li LT, Li JQ, Zhang MH, Lu Y, Xie XB, Hong YR, Yu Z, Knisely AS, Wang JS. Low-GGT intrahepatic cholestasis associated with biallelic USP53 variants: Clinical, histological and ultrastructural characterization. Liver Int. 2020;40:1142-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Overeem AW, Li Q, Qiu YL, Cartón-García F, Leng C, Klappe K, Dronkers J, Hsiao NH, Wang JS, Arango D, van Ijzendoorn SCD. A Molecular Mechanism Underlying Genotype-Specific Intrahepatic Cholestasis Resulting From MYO5B Mutations. Hepatology. 2020;72:213-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Couchonnal E, Lion-François L, Guillaud O, Habes D, Debray D, Lamireau T, Broué P, Fabre A, Vanlemmens C, Sobesky R, Gottrand F, Bridoux-Henno L, Dumortier J, Belmalih A, Poujois A, Jacquemin E, Brunet AS, Bost M, Lachaux A. Pediatric Wilson's Disease: Phenotypic, Genetic Characterization and Outcome of 182 Children in France. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;73:e80-e86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Członkowska A, Litwin T, Dusek P, Ferenci P, Lutsenko S, Medici V, Rybakowski JK, Weiss KH, Schilsky ML. Wilson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 605] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ghosh U, Sen Sarma M, Samanta A. Challenges and dilemmas in pediatric hepatic Wilson's disease. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:1109-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chang IJ, Hahn SH. The genetics of Wilson disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;142:19-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cheng N, Wang H, Wu W, Yang R, Liu L, Han Y, Guo L, Hu J, Xu L, Zhao J, Han Y, Liu Q, Li K, Wang X, Chen W. Spectrum of ATP7B mutations and genotype-phenotype correlation in large-scale Chinese patients with Wilson Disease. Clin Genet. 2017;92:69-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nayagam JS, Jeyaraj R, Foskett P, Dhawan A, Ala A, Joshi D, Bomford A, Thompson RJ. ATP7B Genotype and Chronic Liver Disease Treatment Outcomes in Wilson Disease: Worse Survival With Loss-of-Function Variants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1323-1329.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ayoub MD, Kamath BM. Alagille Syndrome: Diagnostic Challenges and Advances in Management. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kohut TJ, Gilbert MA, Loomes KM. Alagille Syndrome: A Focused Review on Clinical Features, Genetics, and Treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2021;41:525-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Halma J, Lin HC. Alagille syndrome: understanding the genotype-phenotype relationship and its potential therapeutic impact. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;17:883-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Habash N, Ibrahim SH. The Global Alagille Alliance study: Redefining the natural history of Alagille syndrome. Hepatology. 2023;77:347-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vandriel SM, Li LT, She H, Wang JS, Gilbert MA, Jankowska I, Czubkowski P, Gliwicz-Miedzińska D, Gonzales EM, Jacquemin E, Bouligand J, Spinner NB, Loomes KM, Piccoli DA, D'Antiga L, Nicastro E, Sokal É, Demaret T, Ebel NH, Feinstein JA, Fawaz R, Nastasio S, Lacaille F, Debray D, Arnell H, Fischler B, Siew S, Stormon M, Karpen SJ, Romero R, Kim KM, Baek WY, Hardikar W, Shankar S, Roberts AJ, Evans HM, Jensen MK, Kavan M, Sundaram SS, Chaidez A, Karthikeyan P, Sanchez MC, Cavalieri ML, Verkade HJ, Lee WS, Squires JE, Hajinicolaou C, Lertudomphonwanit C, Fischer RT, Larson-Nath C, Mozer-Glassberg Y, Arikan C, Lin HC, Bernabeu JQ, Alam S, Kelly DA, Carvalho E, Ferreira CT, Indolfi G, Quiros-Tejeira RE, Bulut P, Calvo PL, Önal Z, Valentino PL, Desai DM, Eshun J, Rogalidou M, Dezsőfi A, Wiecek S, Nebbia G, Pinto RB, Wolters VM, Tamara ML, Zizzo AN, Garcia J, Schwarz K, Beretta M, Sandahl TD, Jimenez-Rivera C, Kerkar N, Brecelj J, Mujawar Q, Rock N, Busoms CM, Karnsakul W, Lurz E, Santos-Silva E, Blondet N, Bujanda L, Shah U, Thompson RJ, Hansen BE, Kamath BM; Global ALagille Alliance (GALA) Study Group. Natural history of liver disease in a large international cohort of children with Alagille syndrome: Results from the GALA study. Hepatology. 2023;77:512-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ayoub MD, Kamath BM. Alagille Syndrome: Current Understanding of Pathogenesis, and Challenges in Diagnosis and Management. Clin Liver Dis. 2022;26:355-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nicastro E, D'Antiga L. Next generation sequencing in pediatric hepatology and liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:282-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vimalesvaran S, Dhawan A. Liver transplantation for pediatric inherited metabolic liver diseases. World J Hepatol. 2021;13:1351-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Gümüş E, Özen H. Glycogen storage diseases: An update. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:3932-3963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 29. | Ibrahim SH, Kamath BM, Loomes KM, Karpen SJ. Cholestatic liver diseases of genetic etiology: Advances and controversies. Hepatology. 2022;75:1627-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mkarem LE, Batika MAH, Bitar R. New hope in treating progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis in children. World J Hepatol. 2025;17:108253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Ferdinandusse S, Jimenez-Sanchez G, Koster J, Denis S, Van Roermund CW, Silva-Zolezzi I, Moser AB, Visser WF, Gulluoglu M, Durmaz O, Demirkol M, Waterham HR, Gökcay G, Wanders RJ, Valle D. A novel bile acid biosynthesis defect due to a deficiency of peroxisomal ABCD3. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tawbeh A, Gondcaille C, Trompier D, Savary S. Peroxisomal ABC Transporters: An Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Marani M, Madan V, Le TK, Deng J, Lee KK, Ma EZ, Kwatra SG. Dysregulation of the Skin-Liver Axis in Prurigo Nodularis: An Integrated Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Population-Based Analysis. Genes (Basel). 2024;15:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ku CS, Naidoo N, Pawitan Y. Revisiting Mendelian disorders through exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2011;129:351-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Taneri B, Asilmaz E, Gaasterland T. Biomedical impact of splicing mutations revealed through exome sequencing. Mol Med. 2012;18:314-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Limanskiy V, Vyas A, Chaturvedi LS, Vyas D. Harnessing the potential of gene editing technology using CRISPR in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2177-2187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Chiang CC, Yeh H, Lim SN, Lin WR. Transcriptome analysis creates a new era of precision medicine for managing recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:780-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/