Published online Feb 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i2.420

Peer-review started: October 26, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 1, 2022

Accepted: January 29, 2022

Article in press: January 29, 2022

Published online: February 27, 2022

Processing time: 118 Days and 23 Hours

We have recently shown that the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (EASL-CLIF) criteria showed a better sensitivity to detect acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) with a better prognostic capability than the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease criteria.

To simplify EASL-CLIF criteria for ease of use without sacrificing its sensitivity and prognostic capability.

Using the United Network for Organ Sharing data (January 11, 2016, to August 31, 2020), we modified EASL-CLIF (mEACLF) criteria; the modified mEACLF criteria included six organ failures (OF) as in the original EASL-CLIF, but renal failure was defined as creatinine ≥ 2.35 mg/dL and coagulation failure was defined as international normalized ratio (INR) ≥ 2.0. The mEACLF grades (0, 1, 2, and ≥ 3) directly reflected the number of OF.

Of the 40357 patients, 14044 had one or more OF, and 9644 had ACLF grades 1-3 by EASL-CLIF criteria. By the mEACLF criteria, 15574 patients had one or more OF. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) for 30-d all-cause mortality by OF was 0.842 (95%CI: 0.831-0.853) for mEACLF and 0.835 (95%CI: 0.824-0.846) for EASL-CLIF (P = 0.006), and AUROC for 30-d transplant-free mortality by OF was 0.859 (95%CI: 0.849-0.869) for mEACLF and 0.851 (95%CI: 0.840-0.861) for EASL-CLIF (P = 0.001). The AUROC of 30-d all-cause mortality by ACLF grades was 0.842 (95%CI: 0.831-0.853) for mEACLF and 0.793 (95%CI: 0.781-0.806) for EASL-CLIF (P < 0.0001). The AUROC of 30-d transplant-free mortality by ACLF was 0.859 (95%CI: 0.848-0.869) for mEACLF and 0.805 (95%CI: 0.793-0.817) for EASL-CLIF (P < 0.0001).

Our study showed that EASL-CLIF criteria for ACLF grades could be simplified for ease of use without losing its prognostication capability and sensitivity.

Core Tip: There is no consensus on the best definition for acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). The most common definition used in the literature is the one proposed European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (EASL-CLIF) consortium. One problem with those criteria is that it is not very user-friendly. We have shown that EASL-CLIF criteria for ACLF could be simplified without losing its sensitivity and ability to prognosticate 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality. We believe that modified EASL-CLIF criteria; the modified criteria that we propose are easier to use than the EASL-CLIF criteria and also have a better prognostic capability.

- Citation: Thuluvath PJ, Li F. Modified EASL-CLIF criteria that is easier to use and perform better to prognosticate acute-on-chronic liver failure. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(2): 420-428

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i2/420.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i2.420

Acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) is associated with one or more organ failures (OF) and a very high short-term mortality[1-4]. Although more than 13 different definitions of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) have been proposed, the three commonly used criteria were those proposed by the Asian Pacific Association for Study of Liver Diseases (APASL), the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (EASL-CLIF) and the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD)[5-9]. In a recent study, we have clearly shown that EASL-CLIF criteria have a better sensitivity and a better ability to predict short-term, all-cause, and transplant-free mortality when compared to the NACSELD criteria[10]. In that study, only 15.3% of those with EASL-CLIF ACLF grade 1-3 met ACLF by NACSELD criteria. Moreover, only less than half of those with EASL-CLIF ACLF grade 3 had ACLF by NACSELD criteria. In addition, the 30-d transplant-free mortality in those with no organ failure by NACSELD was 2.7%, but when the same group was stratified by EASL-CLIF grades 0-3, the mortality rates were 1.5%, 10.5%, 43.5%, and 86%, respectively. There has been a comparative study of EASL-CLIF and APASL criteria using a large Veteran Affairs administrative dataset. In that study, 76.1% of patients with EASL-CLIF ACLF did not fulfill APASL criteria for ACLF[11]. In the same study, the 30-d mortality was 37.6% in those who met the EASL-CLIF criteria suggesting that the APASL criteria missed 75% of patients with ACLF with a very high short-term mortality. Based on the above observations, we believe that EASL-CLIF criteria are superior to NACSELD or APASL criteria to identify ACLF with a very high 30-d mortality.

One of the major criticisms of the EASL-CLIF criteria is that it is not very user-friendly. The EASL-CLIF stratifies patients into four grades (0-3) based on the number of OF, including liver, kidney, brain, coagulation, respiration, or circulation. The differences between EASL-CLIF ACLF grades and EASL-CLIF OF scoring can also result in some confusion, especially with the interpretation of no ACLF and ACLF-grade 1. The objective of our study was to determine whether EASL-CLIF grades of ACLF could be simplified without sacrificing its sensitivity and prognostic capabilities.

We utilized the national data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) for all adults (≥ 18 years) who were listed (n = 53765) for liver transplantation (LT) in the United States between January 11, 2016, to August 31, 2020. During this study period, MELD-Na (model for end-stage liver disease-sodium) was utilized for organ allocation on January 11, 2016, and there were no major policy changes. Patients were excluded if they were listed as status 1, 1A, or 1B (n = 1264), for multi-organ transplantation (n = 3179), re-transplantation (n = 607) or for live donor LT (n = 1421). We also excluded those who received MELD- exception points (n = 8886) and those with missing information on MELD-Na or serum sodium (n = 14) or hepatic encephalopathy stage (n = 53) (Supplementary Figure 1).

We collected clinical characteristics, biochemical parameters such as albumin, bilirubin, international normalized ratio, creatinine, MELD-Na, and the prevalence of OF as defined by EASL-CLIF criteria. We graded ACLF as described by EASL-CLIF into Grade 0, or those patients without any OF or single non-kidney OF, Grade 1a (renal failure), Grade 1b (single non-kidney OF, creatinine 1.5-1.9 mg/dL, and/or mild hepatic encephalopathy), Grade 2 (two OFs), and Grade 3 (three or more OFs)[3]. For this study, we combined 1a and 1b grades as 1. The only deviation of our definition from EASL-CLIF criteria was on respiratory failure as we did not have access to PaO2 or FIO2 and hence used mechanical ventilation as evidence of respiratory failure. We initially assessed the prevalence of type and frequency of OF using EASL-CLIF. Using the same dataset, we developed modified criteria as described later under 'model development'. Patients were followed until the event date or were censored at the end of 30-ds after listing. Our primary objective was to develop an 'easy to use' model, by modifying the EASL-CLIF criteria, with a better short-term (30-d mortality) prognostic capability.

The primary outcomes of interest were the differences in the prevalence of ACLF grades by EASL-CLIF and mEACLF criteria and the observed 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality rates using EASL-CLIF criteria and newly developed modified EASL-CLIF (mEACLF) criteria.

To improve the EASL-CLIF criteria, we determined the best cutoff values for serum creatinine and international normalized ratio (INR) associated with higher mortality. We used a subset of patients (n = 1445) with information on glomerular filtrations rate (GFR) to determine the best cutoff values for serum creatinine levels. The inclusion of GFR data in the UNOS registry was proposed for those with GFR less than 20 mL/min by the Simultaneous Liver Kidney working group in 2015[12]. We used those GFR values to identify the best cutoff values of serum creatinine by smooth regression analysis. The smooth regression analysis showed that serum creatinine ≥ 2.35 mg/dL is the optimal cutoff value (Supplementary Figure 2).

After identifying the best serum creatinine value, we identified the optimal INR cutoff; INR 2.0 had an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) of 0.842 (95% confidence interval 0.831-0.853) to prognosticate 30-d all-cause mortality for coagulation failure by logistic regression after fixing serum creatinine values at ≥ 2.35. We further confirmed the best INR value for the coagulation failure by fixing other organ failures as follows (bilirubin ≥ 12 mg/dL, creatinine ≥ 2.35 mg/dL, HE = 3-4, circulation support = yes, respiration support = yes) by logistic regression. Based on these results, INR ≥ 2.0 was chosen to diagnose coagulation failure.

Using the above values, we then developed a modified 6-organ failure criteria mEACLF (Table 1). In the mEACLF, renal failure was defined as serum creatinine ≥ 2.35 mg/dL (instead of ≥ 2.0 mg/dL of EASL-CLIF criteria) or on renal dialysis. Coagulation failure was defined as INR ≥ 2.0 (instead of 2.5 as per EASL-CLIF criteria). We further simplified the mEACLF grades to directly reflect the number of OF without over-emphasizing serum creatinine levels and without sub-classifying grade 1 into 1a and 1b. The proposed mEACLF grade are as follows: Grade 1 = 1 OF, Grade 2 = 2 OF and Grade 3 = 3 or more OF (Table 1).

| Definition of mEACLF organ failures | |

| Liver | Bilirubin ≥ 12 mg/dL |

| Coagulation | INR ≥ 2.0 |

| Brain | Hepatic encephalopathy grade 3-4 |

| Kidney | Serum creatinine ≥ 2.35 mg/dL or renal replacement |

| Heart | On vasopressors |

| Respiration | On mechanical ventilation |

| Definition of mEACLF grades | |

| Grade 1 | Any one organ failure |

| Grade 2 | Any 2 organ failures |

| Grade 3 | Any 3 or more organ failures |

We compared our new mEACLF criteria with the original EASL-CLIF criteria by looking at the distribution of OF, ACLF grades, and 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality rates.

The demographic characteristics are summarized as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables or frequency for categorical variables. Logistic regression was performed to compare AUROC for 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality based on the EASL-CLIF and mEACLF criteria.

Being a de-identified national dataset, institutional review board (IRB) approval was waived.

Of the 40357 patients who were eligible for the study, 14044 had one or more OF and 9644 ACLF grades 1-3 by EASL-CLIF criteria. Patients’ characteristics stratified by ACLF and no ACLF are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Using the mEACLF criteria, 15574 patients had one or more OF. The comparative clinical characteristics of patients with and without ACLF stratified by mEACLF criteria are shown in Table 2. The direct comparison of patients with one or more OF identified by mEACLF (n = 15574) and EASL-CLIF (n = 14044) is shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Response | All (n = 29618) | EASL-CLIF (n = 14044) | mEACLF (n = 15574) | P value |

| Age | mean ± SD | 52.9 ± 11.6 | 52.9 ± 11.7 | 52.9 ± 11.8 | 0.46 |

| Gender, n (%) | Female | 11803 (40) | 5601 (40) | 6202 (40) | 0.92 |

| Race, n (%) | White | 20059 (68) | 9484 (68) | 10575 (68) | 0.95 |

| Black | 2530 (9) | 1215 (9) | 1315 (8) | ||

| Hispanic | 5242 (18) | 2496 (18) | 2746 (18) | ||

| Asian | 1129 (4) | 540 (4) | 589 (4) | ||

| Others | 658 (2) | 309 (2) | 349 (2) | ||

| Etiology, n (%) | HCV | 3661 (12) | 1730 (12) | 1931 (12) | 0.87 |

| Alcohol | 12537 (42) | 5909 (42) | 6628 (43) | ||

| HCV + Alcohol | 353 (1) | 165 (1) | 188 (1) | ||

| Cryptogenic | 1507 (5) | 712 (5) | 795 (5) | ||

| Others | 11560 (39) | 5528 (39) | 6032 (39) | ||

| Bilirubin | mean ± SD | 13.8 ± 12.5 | 14.1 ± 12.7 | 13.4 ± 12.3 | 0.001 |

| Creatinine | mean ± SD | 2.11 ± 1.79 | 2.19 ± 1.81 | 2.03 ± 1.77 | < 0.001 |

| INR | mean ± SD | 2.30 ± 1.12 | 2.29 ± 1.15 | 2.30 ± 1.08 | < 0.001 |

| Encephalopathy, n (%) | Grade 3-4 | 7088 (24) | 3544 (25) | 3544 (23) | < 0.001 |

| Respiration, n (%) | Yes | 1598 (5) | 799 (6) | 799 (5) | 0.03 |

| Circulatory, n (%) | Yes | 2684 (9) | 1342 (10) | 1342 (9) | 0.005 |

| MELD-Na | mean ± SD | 29.9 ± 8.1 | 30.2 ± 8.2 | 29.7 ± 8.0 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | mean ± SD | 3.10 ± 0.74 | 3.12 ± 0.74 | 3.08 ± 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| Ascites, n (%) | Moderate | 13357 (45) | 6456 (46) | 6901 (44) | 0.02 |

The comparative prevalence of OF by EASL-CLIF and mEACLF criteria are shown in Table 3. There were some differences in the number of patients with OF between EASL-CLIF and mEACLF; 2086 patients with no OF by EASL-CLIF criteria were identified with one OF by mEACLF, and this resulted from a lower threshold for INR with the revised criteria. The 30-d mortality in these 2086 (one OF by mEACLF) patients was 3.4% compared to 1.4% in the EASL-CLIF no OF (n = 26313) group. Similarly, 556 patients with one OF by EASL-CLIF were identified with no OF by the revised criteria, and this resulted from a higher threshold for serum creatinine with the new criteria. The 30-d mortality in these 556 patients was 4.1% compared to 5.8% in the EASL-CLIF one OF (n = 7699) group.

| Number of OF by EASL-CLIF | Number of OF by mEACLF criteria | |||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Total | |

| 0 | 24227 | 2086 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26313 |

| 1 | 556 | 5748 | 1395 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7699 |

| 2 | 0 | 229 | 2875 | 653 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3757 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 152 | 1193 | 215 | 0 | 0 | 1560 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 52 | 458 | 96 | 0 | 606 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 238 | 63 | 311 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 103 | 111 |

| Total | 24783 | 8063 | 4422 | 1898 | 683 | 342 | 166 | 40357 |

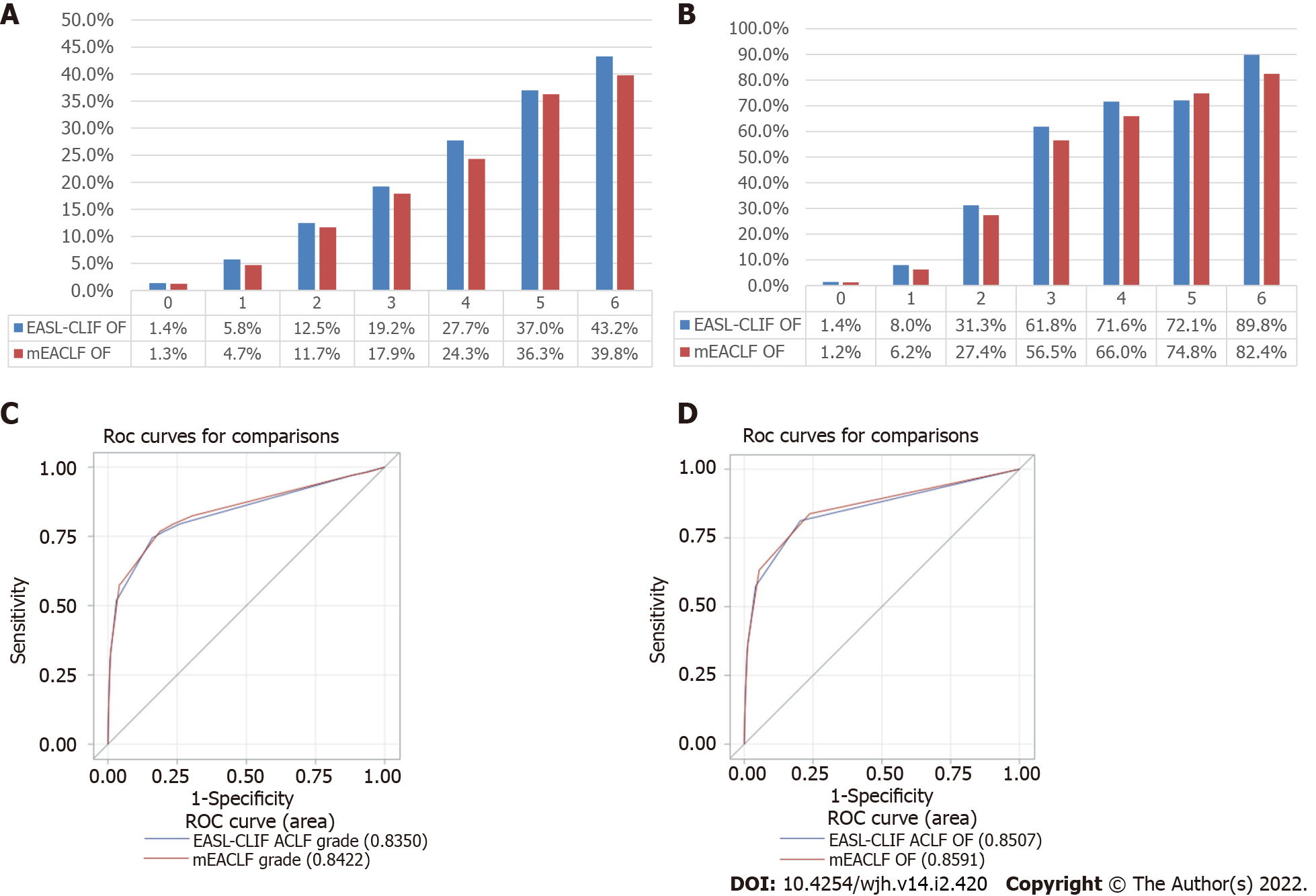

The 30-d mortality rates by OF by both criteria are shown in Figure 1A. The 30-d transplant free mortality rates are shown in Figure 1B. The AUROC for 30-d all-cause mortality by OF was 0.842 (95%CI: 0.831-0.853) for mEACLF and 0.835 (95%CI: 0.824-0.846) for EASL-CLIF (AUROC contrast estimation 0.0072, 95%CI: 0.00208 - 0.0123, P = 0.006) (Figure 1C). AUROC for 30-d transplant-free mortality by OF was 0.859 (95%CI: 0.849-0.869) for mEACLF and 0.851 (95%CI: 0.840-0.861) for EASL-CLIF (AUROC contrast estimation 0.0085, 95%CI: 0.00329 - 0.0136, P = 0.001) (Figure 1D).

There were some discrepancies between the EASL-CLIF grades and mEACLF grades and their corresponding 30-d all-cause mortality rates. 1372 patients who were classified as grade 0 by the EASL-CLIF ACLF were grades mEACLF grade 2, and 30-d all-cause mortality of these 1372 patients was 10.2% as compared to 2.0% in those with EASL-CLIF grade 0 group (n = 30,713) (Table 4). There were outliers in the mEACLF group in terms of 30-d mortality, including 229 patients with grade 1 (EASL-CLIF grade 2) with a mortality of 13.1%, which was higher than grade 1 mEACLF mortality of 4.7% and 152 patients with mEACLF grade 2 (grade 3 by EASL-CLIF) with a mortality of 21.7% which was higher than mEACLF grade 2 mortality of 11.7%.

| EASL-CLIF grade | Number of patients mEACLF Grade (all-cause mortality%) | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | |

| 0 | 24227 (1.2) | 5114 (3.3) | 1372 (10.2) | 0 | 30713 (2.0) |

| 1 | 556 (4.1) | 2720 (6.5) | 23 (10.2) | 0 | 3299 (6.1) |

| 2 | 0 | 229 (13.1) | 2875 (11.8) | 653 (15.0) | 3757 (12.5) |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 152 (21.7) | 2436 (24.5) | 2588 (24.4) |

| Total | 24783 (1.3) | 8063 (4.7) | 4422 (11.7) | 3089 (22.5) | 40357 (4.7) |

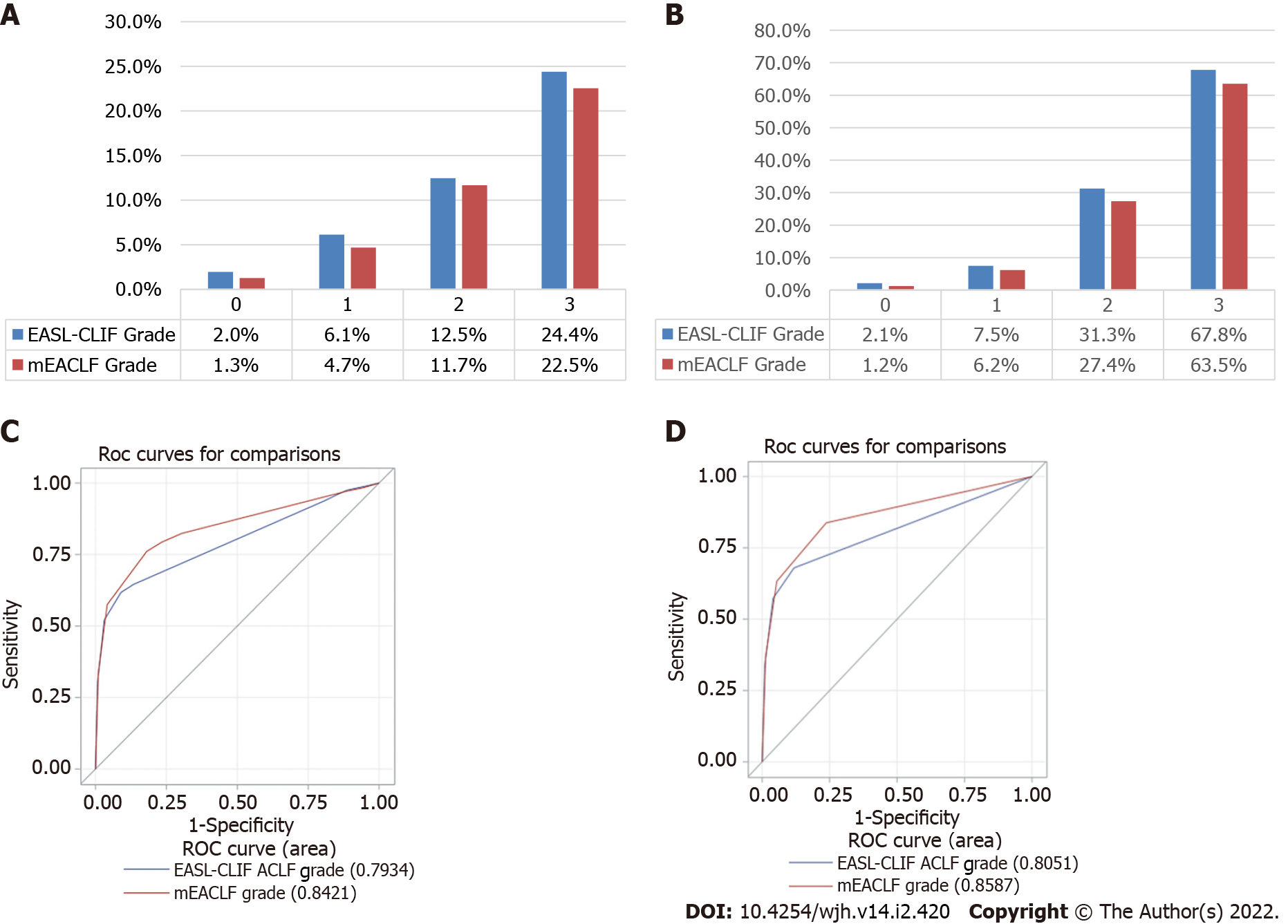

The 30-d mortality rates by grades by both criteria are shown in Figure 2A. The 30-d transplant-free mortality rates are shown in 2B. The AUROC of 30-d all-cause mortality by grades was 0.842 (95%CI: 0.831-0.853) for mEACLF and 0.793 (95%CI: 0.781-0.806) for EASL-CLIF. These differences were highly significant (P < 0.0001, Figure 2C). The AUROC of 30-d transplant-free mortality was 0.859 (95%CI: 0.848-0.869) for mEACLF and 0.805 (95%CI: 0.793-0.817) for EASL-CLIF (P < 0.0001, Figure 2D).

Our study showed that EASL-CLIF criteria for ACLF grades could be simplified for ease of use without losing its sensitivity. The mEACLF criteria that we propose are also better than the EASL-CLIF grades to prognosticate 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality. Both criteria showed low 30-d mortality in those with 0-1 OF, and the mortality increased progressively with an increase in the number of OF. Similar observations were also made for ACLF grades with low mortality with grade 1 and a two-fold difference in mortality between grades 2 and 3.

Few patients in our study will be graded zero by EASL-CLIF but grade 1-2 by mEACLF. This discrepancy is mainly because the EASL-CLIF will grade a single non-kidney organ failure patient as EASL-CLIF grade zero if the serum creatinine < 1.5 mg/dL. The differences in the threshold for INR to classify as coagulation failure also may have contributed to some of the discrepancies. Interestingly, the 30-d all-cause mortality in the group (n = 1372) with grade 2 mEACLF and grade 0 by EASL-CLIF was 10.2%, 5-fold higher than the mortality rates of 2.0% for the cohort with EASL-CLIF grade 0. The number of outliers with higher mortality than their group mortality was fewer in the mEACLF cohorts when stratified by EASL-CLIF grades. These observations may suggest that mEACLF is perhaps as accurate or perhaps better in terms of mortality risk stratification. The AUROC showed consistently better prognostic ability with mEACLF than EASL-CLIF by organ failures or grades for both 30-d all-cause mortality and transplant-free mortality.

There are a few limitations to our study. Our observations are based on a retrospective analysis of an administrative dataset. Therefore, our observations need to be corroborated in a large and independent dataset. Nevertheless, we had an opportunity to develop the model based on approximately 15000 patients with organ failures from a prospectively maintained administrative dataset that included approximately 40000 patients with end-stage liver disease awaiting a liver transplant. It could be argued that these patients were selected after extensive workup for liver transplantation and may not be a true reflection of ACLF patients seen in the community. Moreover, liver transplantation is a confounder in this study. We believe that these are legitimate limitations of our study and it is also true for most studies of ACLF as they are done in mostly academic centers. It is also challenging to do a study of this nature in patients who are not listed for liver transplantation. Our study population came from the entire country and therefore truly reflects the transplant population with ACLF. The UNOS dataset did not have information about PaO2, FIO2, or mean arterial pressure (MAP), and we had to use the predefined variables in the UNOS dataset for the respiratory and circulatory system failure. We do not believe that the availability of those data would have made any meaningful differences in our observations[10].

In summary, we have shown that EASL-CLIF criteria for ACLF could be simplified without losing its sensitivity and its ability to prognosticate 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality. We and others have recently shown that EASL-CLIF criteria are far more sensitive to detect ACLF than both APASL and NACSELD criteria. We believe that the mEACLF criteria that we propose are easier to use than the EASL-CLIF criteria and also have a better prognostic capability. We hope our mEACLF criteria could be adopted by the hepatology community to advance this field.

There is no consensus on the definition of acute on chronic liver failure. We had recently shown that the definition proposed by the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (EASL-CLIF) is more sensitive to identify acute on chronic liver failure and has a better ability to predict all-cause and short-term mortality than that were proposed by the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease.

One of the major criticisms of EASL-CLIF criteria is that it is more complicated to use in clinical practice.

In this study, using a large dataset, our objective was to develop an easier to use model that will be easier to use in clinical practice.

We initially assessed the prevalence of type and frequency of organ failures (OF) using EASL-CLIF. Using the same dataset, we developed modified criteria as described later under 'model development'. Patients were followed until the event date or were censored at the end of 30-ds after listing. To improve the EASL-CLIF criteria, we determined the best cutoff values for serum creatinine and international normalized ratio (INR) that were associated with higher mortality. We used a subset of patients (n = 1445) with information on glomerular filtrations rate to determine the best cutoff values for serum creatinine levels. After identifying the best serum creatinine value, we identified the optimal INR cutoff. Using the above values, we then developed a modified 6-organ failure criteria modified EASL-CLIF (mEACLF). We compared our new mEACLF criteria with the original EASL-CLIF criteria by looking at the distribution of OF, acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) grades, and 30-d all-cause and transplant-free mortality rates.

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) of 30-d all-cause mortality by ACLF grades was 0.842 (95%CI: 0.831-0.853) for mEACLF and 0.793 (95%CI 0.781-0.806) for EASL-CLIF (P < 0.0001). The AUROC of 30-d transplant-free mortality by ACLF was 0.859 (95%CI: 0.848-0.869) for mEACLF and 0.805 (95%CI: 0.793-0.817) for EASL-CLIF (P < 0.0001).

Our study showed that EASL-CLIF criteria for ACLF grades could be simplified for ease of use without losing its prognostication capability and sensitivity.

To advance ACLF research in a meaningful manner, it is essential to have easy-to-use criteria. We believe that the modified EASL-CLIF criteria are an important step in that direction.

| 1. | Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2137-2145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 77.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Hernaez R, Solà E, Moreau R, Ginès P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: an update. Gut. 2017;66:541-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Zaccherini G, Weiss E, Moreau R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Definitions, pathophysiology and principles of treatment. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thuluvath PJ, Thuluvath AJ, Hanish S, Savva Y. Liver transplantation in patients with multiple organ failures: Feasibility and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2018;69:1047-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST; Garg H et al Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol Int 2009; 3:269-282. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Alessandria C, Laleman W, Zeuzem S, Trebicka J, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL–CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426-1437, 1437.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1720] [Cited by in RCA: 2279] [Article Influence: 175.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 7. | Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, Amoros A, Moreau R, Ginès P, Levesque E, Durand F, Angeli P, Caraceni P, Hopf C, Alessandria C, Rodriguez E, Solis-Muñoz P, Laleman W, Trebicka J, Zeuzem S, Gustot T, Mookerjee R, Elkrief L, Soriano G, Cordoba J, Morando F, Gerbes A, Agarwal B, Samuel D, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC study investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1038-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 781] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Bajaj JS, O'Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Biggins SW, Patton H, Fallon MB, Garcia-Tsao G, Maliakkal B, Malik R, Subramanian RM, Thacker LR, Kamath PS; North American Consortium For The Study Of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD). Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014;60:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | O'Leary JG, Reddy KR, Garcia-Tsao G, Biggins SW, Wong F, Fallon MB, Subramanian RM, Kamath PS, Thuluvath P, Vargas HE, Maliakkal B, Tandon P, Lai J, Thacker LR, Bajaj JS. NACSELD acute-on-chronic liver failure (NACSELD-ACLF) score predicts 30-day survival in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2018;67:2367-2374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Li F, Thuluvath PJ. EASL-CLIF criteria outperform NACSELD criteria for diagnosis and prognostication in ACLF. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1096-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mahmud N, Kaplan DE, Taddei TH, Goldberg DS. Incidence and Mortality of Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Using Two Definitions in Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2019;69:2150-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mark Aeder, Nicole Turgeon. OPTN/UNOS Kidney Transplantation Committee Meeting Summary. November 16, 2015 Conference Call. Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1643/kidney_meetingsummary_20151116.pdf. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: de Mattos ÂZ, Ferrarese A S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ