Published online Oct 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i10.863

Peer-review started: May 20, 2020

First decision: July 29, 2020

Revised: August 2, 2020

Accepted: August 26, 2020

Article in press: August 26, 2020

Published online: October 27, 2020

Processing time: 155 Days and 6.8 Hours

Kratom is a psychoactive substance that is isolated from the plant Mitragyna speciosa. The leaves can be chewed fresh or dried, smoked, or infused similar to herbal teas. The plant leaves have been used by natives of Southeast Asia for centuries. The substance has been used for its stimulant activity at low doses, and as an opium substitute at higher doses due to a morphine like effect.

A 37-year-old female with a history of depression and obesity (body mass index: 32) presented to emergency room with a week-long history of nausea, decreased appetite, fatigue, and two days of jaundice. On admission bilirubin was markedly elevated. Her condition was thought to be due to consumption of Kratom 2 wk before onset of symptoms. Liver biopsy showed changes mimicking primary biliary cholangitis. Patient’s symptoms and jaundice improved quickly.

The use of Kratom has been on the rise in recent years across the United States and Europe. Several case reports have associated adverse health impact of Kratom-containing products including death due to its ability to alter levels of consciousness. Only a few case reports have highlighted the hepatotoxic effects of Kratom. Even fewer reports exist describing the detailed histopathological changes.

Core Tip: Kratom induced liver injury is an important differential diagnosis for physicians to consider in any patient presenting with acute liver injury. As observed in our patient, this manifestation of Kratom consumption may occur even at low doses. Further, this case report demonstrates that a thorough history is essential for an accurate and timely diagnosis. Patients may consider dietary and herb supplements to be natural and risk-free products, not realizing the potential for harm. In addition to asking their patients about consumption of any supplements, it is imperative that physicians update themselves so as to be able to discuss the benefits and risks, and counsel their patients effectively. Identifying use of supplements helps in early diagnosis and treatment, while also preventing future harm. From the pathology perspective, biliary changes associated with Kratom injury can mimic primary biliary cholangitis.

- Citation: Gandhi D, Ahuja K, Quade A, Batts KP, Patel L. Kratom induced severe cholestatic liver injury histologically mimicking primary biliary cholangitis: A case report. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(10): 863-869

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i10/863.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i10.863

Acute liver failure is a severe condition which may rapidly become fatal[1]. In the United States, a significant number of these cases occur due to drug-induced liver injury[2]. Apart from prescribed medications, consumption of herbal and dietary supplements also plays an important role in causing liver injury[2]. We present here a case of a 37-year-old female, with drug induced liver injury mimicking as antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) negative primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), secondary to consumption of an herbal supplement, Kratom. Derived from the leaves of Mitragyna speciosa, a plant found in Southeast Asia and Africa, this supplement is used for its stimulant properties, as a substitute for opioids, and to help opioid withdrawal symptoms[3]. People in the United States report using this supplement predominantly for pain relief, and also report increased levels of energy and focus with consumption[4]. Our patient learned of this herbal supplement from a friend and reported consuming it in order to boost her energy levels. Although uncommon, this herbal supplement is associated with the risk of hepatotoxicity, making it imperative for physicians to be aware of its harmful effects and caution their patients against its use[4].

A 37-year-old female with a history of depression and obesity (body mass index: 32) presented to emergency room with a week-long history of nausea, decreased appetite, fatigue, and two days of jaundice.

Four days prior to admission, she noticed that her stools were becoming tanner and eventually turned white. She also reported that her urine was dark. Two days prior to admission the patient noticed jaundice and scleral icterus which prompted her to seek treatment. Her only home medication was venlafaxine, which she had been taking for several years. She has no history of alcohol abuse.

On further questioning about new medications or supplement use, the patient reported using an herbal supplement containing Kratom two weeks prior to the onset of her symptoms. She used the supplement for the first time in her life. Encouraged by a friend to use the supplement to “boost energy levels,” she believed it was safe because it was “all natural”. She consumed approximately three grams in total over the course of three days in the form of powder (which she dissolved in water) and tablets. During her hospitalization, the patient’s liver enzymes continued to rise. On day 3 of her hospitalization, a liver biopsy was performed.

History of depression and obesity.

Unremarkable except jaundice.

On admission, the patient had markedly elevated liver enzymes (Table 1). Other basic laboratory findings including blood count, basic metabolic panel, coagulation panel, serum thyroid stimulating hormone and antinuclear antibody were within normal range. Viral and autoimmune hepatitis studies were normal. Ceruloplasmin level was also normal. AMA was negative.

| HD1 | HD2 | HD3 | HD4 | HD5 | Six days post- discharge | Normal values | |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 10.3 | 12.0 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 19.5 | 5.7 | < 1.0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 672 | 677 | 744 | 817 | 839 | 507 | 50-160 |

| ALT (U/L) | 578 | 585 | 600 | 608 | 591 | 323 | 0-30 |

| AST (U/L) | 455 | 461 | 437 | 401 | 385 | 101 | 0-40 |

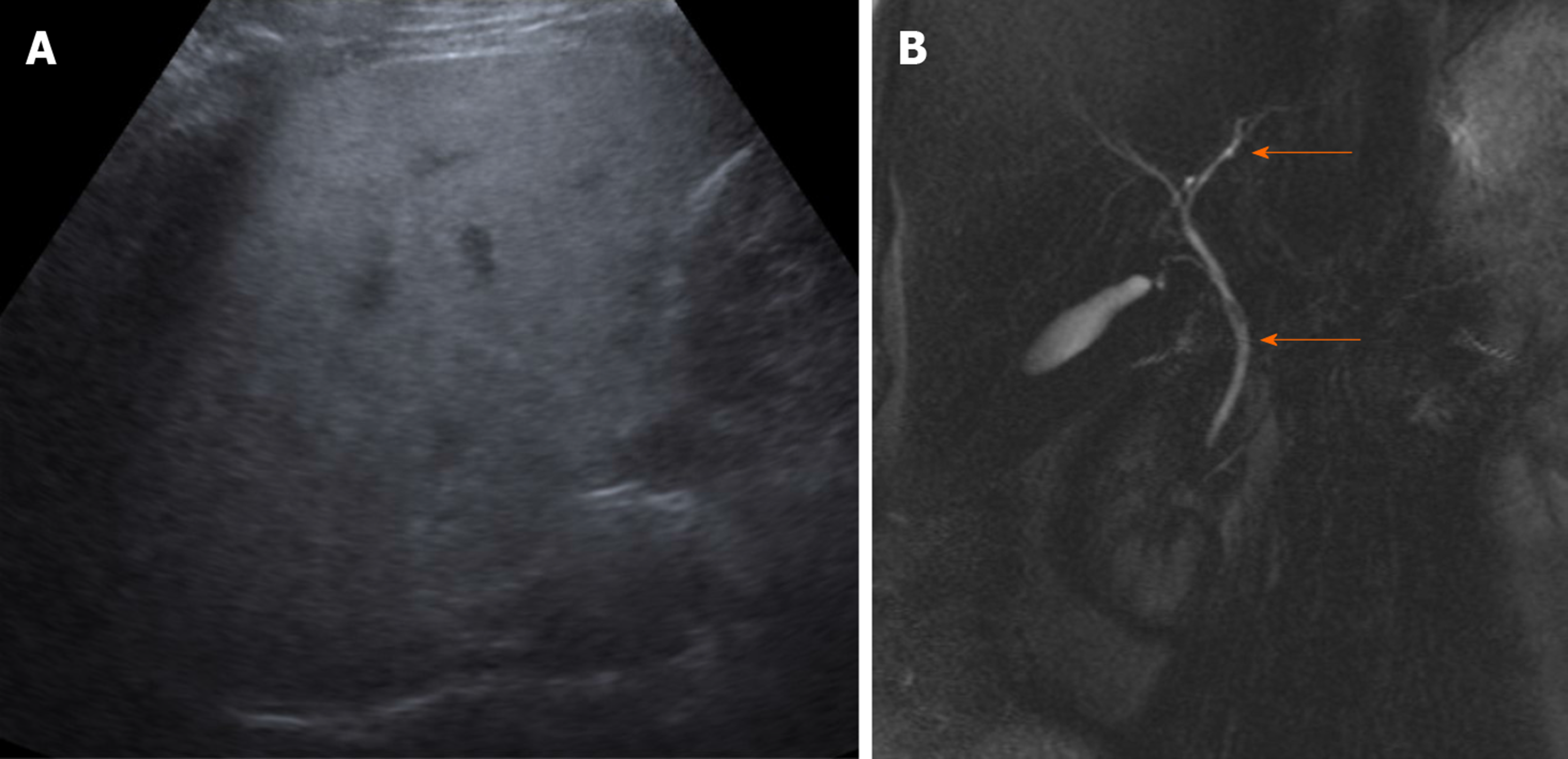

An abdominal ultrasound showed diffuse increased echogenicity of the liver with normal liver size and contour suggests diffuse hepatic steatosis (Figure 1). No intrahepatic or common biliary duct dilation or gall stones seen. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed similar findings. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography did not demonstrate any further abnormalities.

Kratom induced severe liver injury histologically mimicking PBC.

The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg daily. Advised to avoid any new medications or over the counter products with the potential risk of liver injury till her liver enzymes normalized.

The patient was discharged on day 5 of hospitalization and follow up was arranged with gastroenterology clinic. The patient had liver enzymes checked six days after discharge; her symptoms and liver enzymes showed marked improvement. Steroids were stopped. Patient was lost to further lab follow up with gastroenterology clinic but reported feeling back to her normal on follow up phone call 2-wk post hospitalization.

The herbal supplement Kratom is a psychoactive substance derived from the leaves of Mitragyna speciosa, a plant native to Southeast Asia[3]. Its leaves are used for a variety of purposes, such as pain relief, enhancing energy levels, substituting opioids, managing opioid withdrawal[3,4]. The psychoactive compounds of Kratom, mitragynine, and 7-hydroxymitragynine may also result in altered consciousness, particularly at high doses of consumption[3]. As a result, Kratom is a controlled drug in several countries and illegal in several others[5]. The Drug Enforcement Administration of the United States considers it a Drug and Chemical of Concern[6]. While Kratom products are legal in most parts of the United States, a few states and cities have banned them[4]. With concerns regarding its safety, the Food and Drug Administration warns consumers against the use of these products[4,7].

Further, studies have shown that patients reporting Kratom use may present with confusion, lethargy, irritability, agitation, nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, hypertension or in severe cases, bradycardia, seizures, increased bilirubin, renal failure and even coma[4]. Further, Kratom is also reported to exert effects similar to opioids, such as sedation, hypnosis, nausea, stupor and respiratory depression[3,4,8]. In addition to this, the Food and Drug Administration has recalled Kratom supplements due to contamination with Salmonella[9].

Although Kratom induced liver injury is described, reports with detailed description of histopathological changes are rare which are mentioned below in Table 2. Rapid clinical and liver enzyme improvement supports the diagnosis of Kratom induced liver injury.

| Ref. | Age, sex | Clinical findings | Form, amount, duration of Kratom consumed | Peak bilirubin (mg/dL) | Disease pattern | Radiological findings | Histological findings |

| Kapp et al[11] | 25, M | Abdominal pain, brown urine, jaundice, pruritus | Powder, 1 to 2 teaspoon twice a day and increased to 4-6 teaspoon over 2 wk (1 teaspoon approximately 2-3 g) | Direct bilirubin 29.3 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | USG, CT-hepatic steatosis | Cholestatic injury, no hepatocellular damage, canalicular cholestasis |

| Drago et al[14] | 23, M | Jaundice, pale stool, brown urine for 4 d | Powder, 85 g total over 6 wk | Direct bilirubin 5.8 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | USG, CT-normal | Cholestatic liver injury |

| Bernier et al[15] | 41, F | Jaundice, diarrhea, pruritus | Form not available, 1 teaspoon twice daily for 1 wk | Direct bilirubin 15 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | - | Intralobular bile duct destruction with cholestatic overload |

| Shah et al[16] | 30, F | Abdominal pain, jaundice, dark urine, pruritus | Tea containing Kratom, dose not available | Direct bilirubin 18 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | MRI-normal, ERCP–no bile duct obstruction | Intrahepatic cholestasis |

| Riverso et al[13] | 38, M | Dark urine, light stools, fever | Not available | Total bilirubin 5.6 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | USG-normal | Acute cholestatic injury, mild bile duct injury, portal inflammation |

| Mackenzie et al[17] and De Francesco et al[18] | 27, M | Vomiting, epigastric pain, diarrhea with associated heavy alcohol intake | Powder, 3-4 teaspoon multiple times weekly for several wk | Total bilirubin 11.2 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | - | Widespread hepatocellular necrosis with extracellular cholestasis |

| Fernandes et al[12] | 52, M | Mild fatigue, jaundice | Crushed leaves with water, 1 teaspoon (approximately 1.5 g) once or twice a day for 2 mo | Total bilirubin 28.9 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, ALP; slightly increased AST, ALT) | MRI - normal | Canalicular cholestasis, bile duct injury, hepatic lobule injury, mixed inflammation in portal tracts |

| Aldyab et al[10] | 40, F | Abdominal pain, fever | Form not available, once a week for 1 mo | Total bilirubin 5.1 | Mixed cholestatic and hepatocellular (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | CT, MRCP–mild, nonspecific periportal edema | Granulomatous duct injury |

| Pronesti et al[19] | 30, M | Dark urine and pale stool for 1 wk, scleral icterus for 1 d | Powder with water, for 4-6 wk | Total bilirubin 5.7, direct bilirubin 4.5 | Cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | USG–coarse hepatic echotexture | Hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis with inflammation and focal prominent eosinophils. No fibrosis |

| LiverTox case 6972[20] | 25, M | Abdominal pain, fever, jaundice, dark urine, pruritus | Powder, for 23 d | Total bilirubin 22.4 | Mixed Hepatocellular and cholestatic (increased bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP) | USG, CT–gall bladder wall thickening with increased perihepatic lymph nodes | Cholestatic injury with mild necrosis and inflammation |

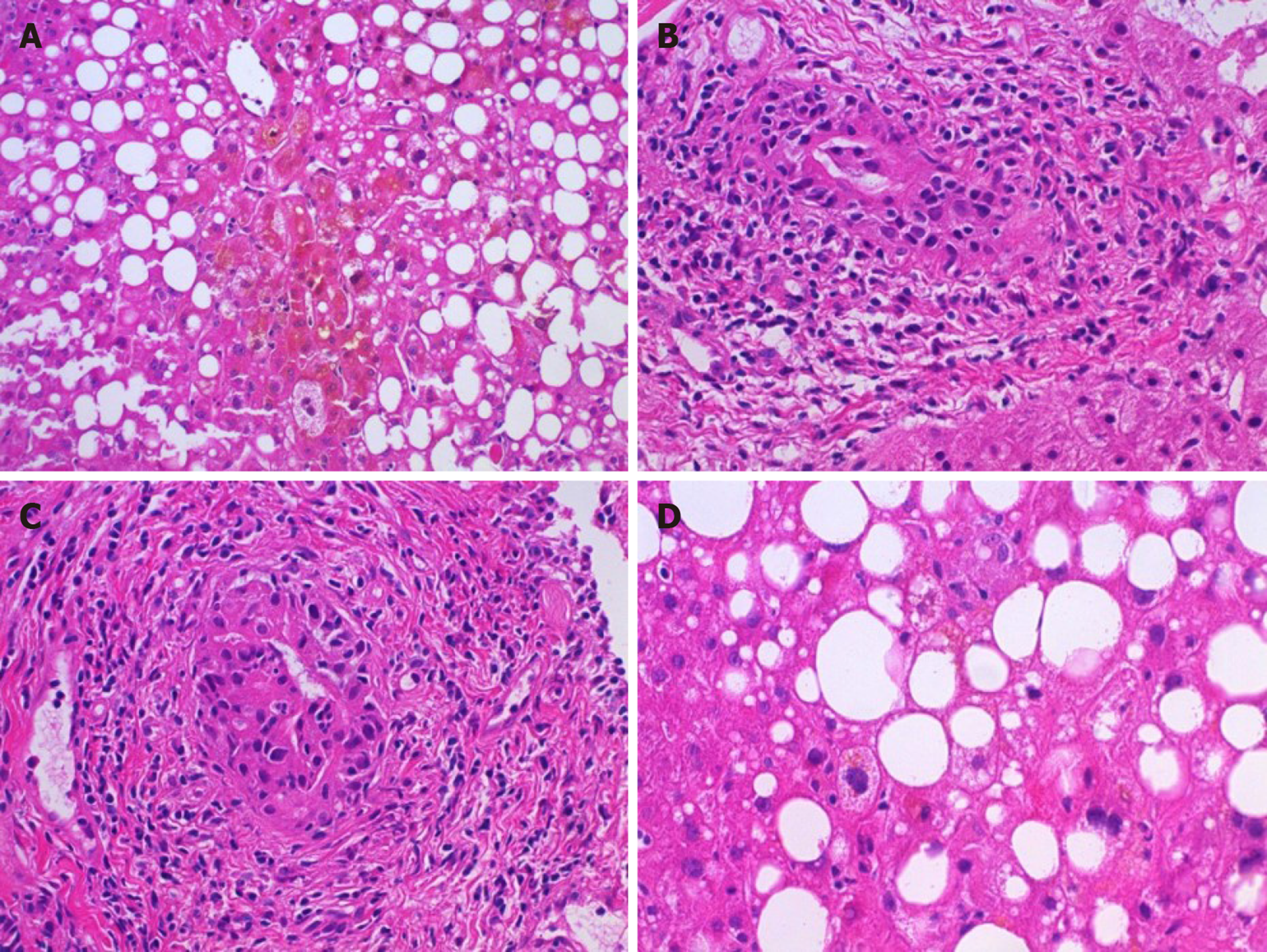

An interesting aspect of our case is the pathological features of liver injury (Figure 2). The zone 3 cholestasis was felt to reflect drug effect; zone 3 cholestasis is a common finding in cholestatic drug reactions but not a feature of early stage PBC. The lymphocytic cholangitis, a typical feature of PBC and unusual medication-injury finding, raised initial concern for underlying early stage PBC. This is of lesser concern given her negative antinuclear antibody and AMA status, trend toward rapid resolution of liver enzymes, and a case report by Aldyab et al[10] in 2019 that reported a case of kratom toxicity with granulomatous cholangitis (another form of florid duct lesion) that mimicked PBC. This was from a 40-year-old female presenting with liver injury after Kratom use who initially perceived to have AMA-negative PBC but diagnosed with Kratom induced liver injury after rapid normalization of liver enzymes.

In the first published case report of intrahepatic cholestasis due to consumption of Kratom, the patient’s laboratory results showed a peak bilirubin of 29.3 mg/dL with prolonged elimination based on known half-life of the drug and analysis of urine samples[11]. It was speculated that this could be due to the patient’s underlying steatohepatitis[11]. Similarly, our patient also had steatohepatitis observed on imaging and pathology, which could explain why even the relatively low doses of Kratom used by our patient compared to other cases discussed in the literature led to such profound liver injury.

As Kratom use appears to be on the rise in the United States, physicians need to be aware of its potential for adverse effects[4,9]. This case highlights how even small amounts of the supplement can be hepatotoxic. Physicians need to be able to discuss safety concerns of over-the-counter supplements with their patients. Moreover, the rising use of supplements and recreational substances can pose diagnostic challenges for clinicians when their use is not reported. Medical providers always need to consider the use of supplements when patients present with possible drug-induced liver injury.

Kratom induced liver injury is an important differential diagnosis for physicians to consider in any patient presenting with acute liver injury. As observed in our patient, this manifestation of Kratom consumption may occur even at low doses. Further, this case report demonstrates that a thorough history is essential for an accurate and timely diagnosis. Patients may consider dietary and herb supplements to be natural and risk-free products, not realizing the potential for harm. In addition to asking their patients about the consumption of any supplements, it is imperative that physicians update themselves so as to be able to discuss the benefits and risks and counsel their patients effectively. Identifying use of supplements helps in early diagnosis and treatment, while also preventing future harm. From the pathology perspective, biliary changes associated with Kratom injury can mimic PBC.

| 1. | Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, McCashland TM, Shakil AO, Hay JE, Hynan L, Crippin JS, Blei AT, Samuel G, Reisch J, Lee WM; U. S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1562] [Cited by in RCA: 1483] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J; Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924-1934, 1934.e1-1934.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 34.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Pantano F, Tittarelli R, Mannocchi G, Zaami S, Ricci S, Giorgetti R, Terranova D, Busardò FP, Marinelli E. Hepatotoxicity Induced by "the 3Ks": Kava, Kratom and Khat. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Veltri C, Grundmann O. Current perspectives on the impact of Kratom use. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2019;10:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA and Kratom. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-kratom. |

| 6. | Drug Enforcement Administration-U.S Department of Justice. Drugs of Abuse: A DEA Resource Guide. 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.dea.gov/pr/multimedia-library/publications/drug_of_abuse.pdf#page=84. |

| 7. | U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA issues warnings to companies selling illegal, unapproved kratom drug products marketed for opioid cessation, pain treatment and other medical uses. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-warnings-companies-selling-illegal-unapproved-kratom-drug-products-marketed-opioid. |

| 8. | Prozialeck WC, Jivan JK, Andurkar SV. Pharmacology of kratom: an emerging botanical agent with stimulant, analgesic and opioid-like effects. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112:792-799. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Post S, Spiller HA, Chounthirath T, Smith GA. Kratom exposures reported to United States poison control centers: 2011-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:847-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Aldyab M, Ells PF, Bui R, Chapman TD, Lee H. Kratom-Induced Cholestatic Liver Injury Mimicking Anti-Mitochondrial Antibody-Negative Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Gastroenterology Res. 2019;12:211-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Kapp FG, Maurer HH, Auwärter V, Winkelmann M, Hermanns-Clausen M. Intrahepatic cholestasis following abuse of powdered kratom (Mitragyna speciosa). J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fernandes CT, Iqbal U, Tighe SP, Ahmed A. Kratom-Induced Cholestatic Liver Injury and Its Conservative Management. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2019;7:2324709619836138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Riverso M, Chang M, Soldevila-Pico C, Lai J, Liu X. Histologic Characterization of Kratom Use-Associated Liver Injury. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11:79-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Drago JZ, Lane B, Kochav J, Chabner B. The Harm in Kratom. Oncologist. 2017;22:1010-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bernier M, Allaire M, Lelong-Boulouard V, Rouillon C, Boisselier R. Inserm. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) “phyto-toxicomania": about a case of acute hepatitis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2017;31:19-211. |

| 16. | Shah SR, Basit SA, Orlando FL. Kratom-induced severe intrahepatic cholestasis: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S1190. |

| 17. | Mackenzie C, Thompson M. Salmonella contaminated Kratom ingestion associated with fulminant hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation. Clin Toxicol. 2018;56:947. |

| 18. | De Francesco E, Lougheed C, Mackenzie C. Kratom-induced acute liver failure. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2019;72:69. |

| 19. | Pronesti V, Sial M, Talwar A, Aoun E. Cholestatic liver injury caused by kratom ingestion: 2426. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S1344. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | LiverTox, NIH. Summary of case 6972. [cited 25 Apr 2019]. Available from: https://livertox.niddk.nih.gov/Home/Reference Cases/kratom/6972. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jiang W, Liu J S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH