Published online May 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i5.417

Peer-review started: February 3, 2018

First decision: March 8, 2018

Revised: April 23, 2018

Accepted: May 11, 2018

Article in press: May 11, 2018

Published online: May 27, 2018

Processing time: 114 Days and 4 Hours

To characterize isolated non-obstructive sinusoidal dilatation (SD) by identifying associated conditions, laboratory findings, and histological patterns.

Retrospectively reviewed 491 patients with SD between 1995 and 2015. Patients with obstruction at the level of the small/large hepatic veins, portal veins, or right-sided heart failure were excluded along with history of cirrhosis, hepatic malignancy, liver transplant, or absence of electrocardiogram/cardiac echocardiogram. Liver histology was reviewed for extent of SD, fibrosis, red blood cell extravasation, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, hepatic peliosis, and hepatocellular plate atrophy (HPA).

We identified 88 patients with non-obstructive SD. Inflammatory conditions (32%) were the most common cause. The most common pattern of liver abnormalities was cholestatic (76%). Majority (78%) had localized SD to Zone III. Medication-related SD had higher proportion of portal hypertension (53%), ascites (58%), and median AST (113 U/L) and ALT (90 U/L) levels. Nineteen patients in our study died within one-year after diagnosis of SD, majority from complications related to underlying diseases.

Significant proportion of SD and HPA exist without impaired hepatic venous outflow. Isolated SD on liver biopsy, in the absence of congestive hepatopathy, requires further evaluation and portal hypertension should be rule out.

Core tip: We identified 88 patients with diagnosis of non-obstructive sinusoidal dilatation (SD) over the period of twenty years. Inflammatory conditions (32%) were the most common cause identified. Medication related SD was associated with higher proportion of portal hypertension, ascites, and elevated transaminases. The finding of non-obstructive SD on liver biopsy should prompt a review of patient’s medical history and drug exposure. Additionally, portal hypertension should be rule out either clinically, endoscopically, or radiographically. There does not appear to be any relationship between histological patterns and medical conditions, which may suggest overlapping biological pathways in the development of non-obstructive sinusoidal dilatation.

- Citation: Sunjaya DB, Ramos GP, Braga Neto MB, Lennon R, Mounajjed T, Shah V, Kamath PS, Simonetto DA. Isolated hepatic non-obstructive sinusoidal dilatation, 20-year single center experience. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(5): 417-424

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i5/417.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i5.417

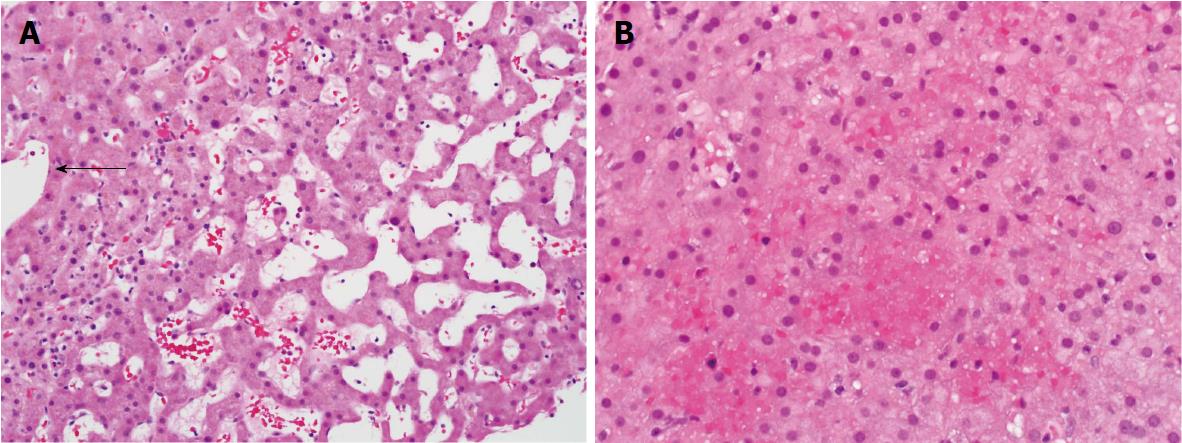

Hepatic sinusoidal dilatation (SD) is usually attributed to either hepatic venous outflow obstruction at the level of small or large hepatic veins, supra-hepatic inferior vena cava, or right-sided heart failure. A proportion of patients demonstrate SD in the absence of post-sinusoidal venous outflow impairment or portal vein thrombosis and the clinical significance of this finding is unclear[1]. Histologically, non-obstructive SD is often characterized by distended sinusoidal spaces, most evident in zone III and, sometimes accompanied by hepatocellular plate atrophy, and/or red blood cell (RBC) extravasation (Figure 1). These findings are non-specific and have been reported with systemic inflammatory states, hematological malignancies, granulomatous disease, medications, and inflammatory bowel disease[2-10]. Sinusoidal dilatation may also be seen on wedge biopsies of the liver obtained intraoperatively. The long-term outcomes of patients with SD are not known. Moreover, there is no clear guidance on how such patients are to be investigated.

The purpose of this study was to better characterize non-obstructive SD by: (1) identifying associated conditions, such as: Vascular disorder, neoplastic disease, inflammatory disease, infections, surgery, or medications; (2) describing the long-term outcomes of these patients; and (3) identifying distinct laboratory or histological patterns that may identify the potential cause or disease association of the SD.

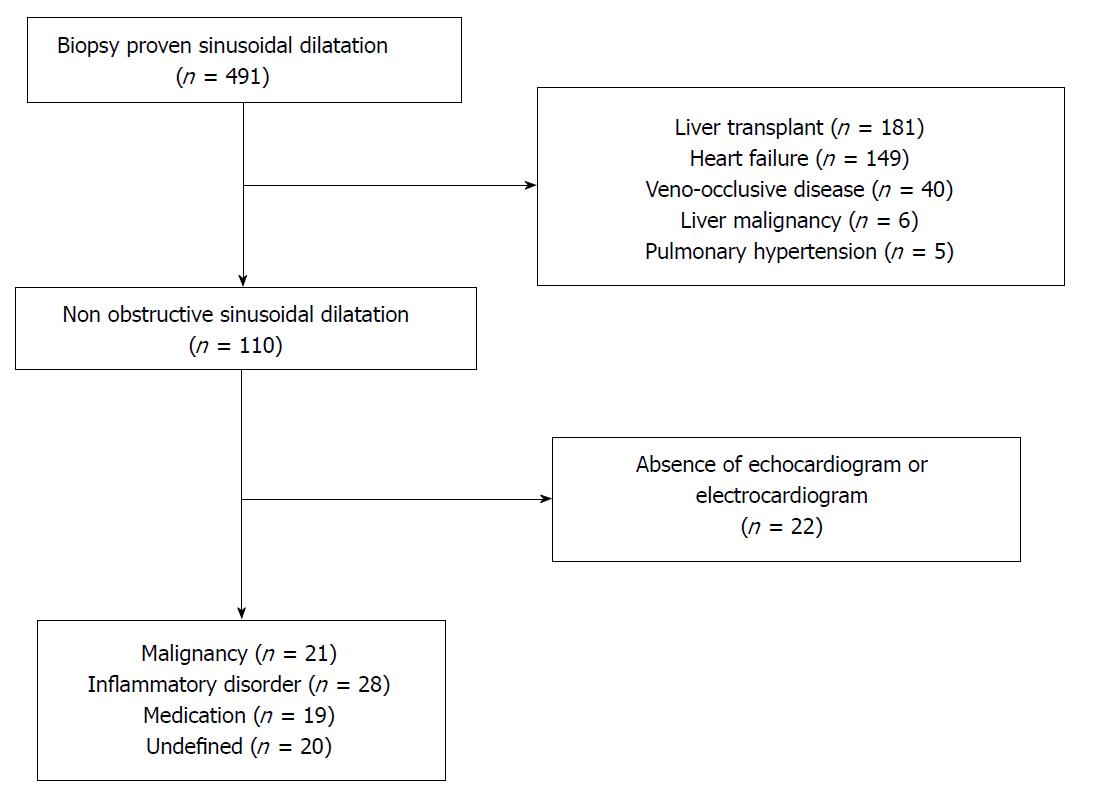

We identified 491 patients from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minnesota electronic medical record between 1995 and 2015 with histological findings consistent with SD on high quality liver biopsy. SD was defined as sinusoidal lumen greater than one liver cell plate wide, observed in several lobules in a high-quality liver specimen devoid of artefactual tearing[9]. We defined high quality liver specimen by the presence of seven or more portal tracts from either needle or wedge biopsy. Patients with confirmed obstruction at the level of the small hepatic veins (veno-occlusive disease or sinusoidal obstruction syndrome), large hepatic veins/inferior vena cava (Budd-Chiari syndrome), portal vein thrombosis, evidence of vascular infiltration (sickle cell, hemophagocytic syndrome, or malignancy) or right-sided heart failure (moderate to severe tricuspid regurgitation, constrictive pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, or elevated right ventricle systolic pressure on echocardiogram) were excluded from the study (Figure 2). In addition, patients with cirrhosis, hepatic malignancy, liver transplant recipients, or absence of electrocardiogram or echocardiogram on medical records (to rule out heart failure) were also excluded from our study. Liver transplant recipients were excluded from the study due to the high likelihood of anastomotic vascular complications resulting in sinusoidal dilatation in this group.

The remaining cases were investigated for associated medical conditions. The electronic records were reviewed for clinical, laboratory values and imaging data (Supplementary Table 1). Imaging studies include abdominal ultrasound, abdominal/ pelvis CT with or without contrast, and abdominal/ pelvis MRI if available. Patients were classified into 1 out of 4 possible categories: inflammatory/auto-immune disorder, malignancy, medication, or undefined based on review of clinical history, histological findings, history of medication exposure, and laboratory findings. Patients with diagnosis of long standing inflammatory/ auto-immune disorder in the absence of other plausible etiology were categorized to the inflammatory/auto-immune category. Patients with history of malignancy without previous exposure to medications associated with SD (including chemotherapy drugs) were assigned to the malignancy group. Patients with exposure to medications known to be associated with SD, such as oxaliplatin or estrogen, in the absence of other plausible etiology were categorized into the medication-related category. Patients without history of inflammatory/auto-immune disorder, malignancy, or exposure to medications associated with SD were assigned to the undefined category.

| Variables | n = 88 |

| Age | 56 (6-85) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 48 (54.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 75 (85.2) |

| Mortality within 1 yr | 19 (21.6) |

| Portal hypertension | 31 (35.2) |

| Radiological Findings | |

| Hepatic nodule(s) | 15 (17.0) |

| Splenomegaly | 35 (39.8) |

| Ascites | 29 (33.0) |

| Pattern of liver injury | |

| Hepatocellular | 8 (9.1) |

| Cholestatic | 67 (76.1) |

| Mixed | 9 (10.2) |

| Normal | 4 (4.5) |

| Primary medical condition | |

| Malignancy | 21 (23.9) |

| Inflammatory disorder | 28 (31.8) |

| Medication | 19 (21.6) |

| Undefined | 20 (22.7) |

We reviewed the quality of liver biopsies by evaluating for the number of samples, size of biopsies, and number of portal tracts. Standard histologic staining such as: trichrome and reticulin, were performed on all samples. Special staining, such as PAS- diastase, Congo red, and copper, were performed on select samples based on the degree of clinical or histologic suspicion. The following information was recorded: (1) Extent of SD; (2) extent of fibrosis; (3) RBC extravasation; and presence of (4) hepatocellular plate atrophy. For this study, RBC extravasation was defined as the presence of red blood cells in the space of Disse. Extent of fibrosis was staged using the METAVIR system, which assigns 0 = no fibrosis, 1 = portal fibrosis without septa, 2 = portal fibrosis with few septa, 3 = numerous septa without cirrhosis or 4 = cirrhosis. Histopathological data on nodular regenerative hyperplasia and peliosis hepatis were also obtained. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia was defined as the presence of regenerative nodules on reticulin stain, and no or minimal fibrosis on trichrome staining[11]. Peliosis hepatis was defined as presence of round or oval cavities randomly distributed between areas of normal hepatic parenchyma[12].

Although early sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) cannot be entirely ruled out in patients exposed to chemotherapy drugs, those with typical histologic features of SOS including centrilobular fibrosis and hepatocyte necrosis were not included in this study. Therefore, we defined possible SOS based on liver injury arising within 20 d of chemotherapy exposure with at least two of the following: (1) Rise of serum bilirubin above 2.0 mg/dL; (2) hepatomegaly and/or right upper quadrant tenderness; and (3) sudden weight gain (> 2% of body weight) attributable to fluid accumulation.

The presence of portal hypertension was identified by either: (1) hepatic vein pressure gradient > 6 mmHg; (2) splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia (< 150000); (3) Serum Ascites Albumin Gradient > 1.1 g/dL; or (4) porto-systemic venous collaterals identified on ultrasound, CT, or MRI scans.

The pattern of liver test abnormality was categorized as either as: (1) hepatocellular; (2) cholestasis; (3) mixed; or (4) normal. Normal was defined as the absence of liver test abnormality. The pattern of liver injury was classified using the R factor score[13]. An R value of > 5.0 is used to define hepatocellular injury, R < 2.0 as cholestatic injury, and R between 2.0 to 5.0 as mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic injury. If serum ALT level was not available for R factor score calculation, we utilized our best clinical judgment based on serum AST, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin level.

Overall mortality and death within one year of diagnosis of non-obstructive SD were collected.

Statistical review of this study was performed by a biomedical statistician from the Mayo Clinic division of biomedical statistics and informatics. Dichotomous data were expressed as frequency (percentage). Continuous data were expressed as median and range. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables between different groups. For nominal variables, chi-square test was used. All tests were two-sided and a P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis were done using SPSS version 20.0.

We identified a total of 88 patients with non-obstructive SD, which accounts for 17.9% of all cases with histologic evidence of SD in our center (Figure 2). Abnormal liver enzymes and presence of ascites were the most common indications for the liver biopsy. Needle biopsy accounts for majority of samples (97%). The median number of tissue sample collected was 2 (1-10) with a median number of 8 portal tracts identified and a median biopsy dimension of 1.5 cm (0.5-3.9). The majority of patients were female (55%) and Caucasian (85%) with a median age of 56 years old (6-85) at diagnosis. The most common medical conditions associated with SD were inflammatory conditions or autoimmune disorder (32%) followed by malignancy (24%) and medications (22%). We were not able to identify a potential etiology for twenty patients (23%) (Table 1). The list of complete medical conditions identified in our cohort can be found on Table 2. The most common autoimmune or inflammatory conditions identified were granulomatous hepatitis (n = 4), mixed connective tissue disease (n = 3), and inflammatory bowel disease (n = 3). Hematological malignancies and myeloproliferative diseases, accounted for the majority of the neoplasms in our study cohort. Oxaliplatin based chemotherapy (n = 7) was the most common medication identified in our study cohort followed by purine analogs (n = 3). Oral contraceptive use was identified as a probable cause of non-obstructive SD in two patients.

| Variables | n |

| Malignancy | |

| Hematological malignancies | |

| Leukemia | |

| AML | 2 |

| CLL | 1 |

| CML | 1 |

| Lymphoma | |

| B-cell lymphoma | 4 |

| T-cell lymphoma | 1 |

| Solid organ tumor | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 2 |

| Angiosarcoma | 1 |

| Myeloproliferative disorder | 9 |

| Inflammatory condition | |

| Granulomatous hepatitis | 4 |

| Connective tissue disorder | 3 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 |

| Castleman’s disease | 2 |

| Polyarthritis nodosa | 2 |

| Other1 | 15 |

| Medications | |

| Oxaliplatin | 7 |

| Purine Analogs | 3 |

| Other2 | 9 |

The most common radiological findings associated with SD were splenomegaly (40%) followed by ascites (33%), and hyperechoic liver lesion or hepatic nodule(s) (17%). Portosystemic collateral veins were identified in five patients (6%). Medication related non-obstructive SD had a significantly higher proportion of ascites (58%, P = 0.044) than the other associated clinical conditions (Table 3).

| Malignancy (n = 21) | Inflammatory state (n = 28) | Medication (n = 19) | Not specified (n = 20) | P | |

| Hepatic nodules | 4 (19) | 4 (14) | 4 (21) | 3 (15) | 0.922 |

| Portal hypertension | 10 (48) | 8 (29) | 11 (58) | 6 (30) | 0.144 |

| Ascites | 7 (33) | 5 (18) | 11 (58) | 6 (30) | 0.04 |

| Splenomegaly | 9 (43) | 11 (39) | 9 (47) | 6 (30) | 0.719 |

The median serum AST was 43 U/L, ALT was 44 U/L, total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 271 IU/L, GGT 123 U/L, serum protein 6.4 g/dL, albumin 3.2 g/L, and INR 1.1. Median ESR and CRP were 45.5 mm/h and 5.1 mg/L respectively. ESR and CRP were collected in a subset of patients where clinical suspicion for inflammatory disorder was high. We found medication-related non-obstructive SD was associated with higher median serum AST (113 U/L, P < 0.008) and ALT level (90 U/L, P = 0.002). Five of the thirteen patients (39%) in the medication related SD group had serum total bilirubin greater than 2.0 mg/dL. Four out of five patients in this subgroup had ascites and splenomegaly on imaging suggesting a possible diagnosis of early SOS. We also found lower median platelet counts in medication related SD group (80 x 103, P = 0.022), consistent with higher prevalence of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (Table 4). Malignancy related non-obstructive SD had higher median total bilirubin (1.6 mg/dL, P = 0.008).

| Malignancy | Inflammatory state | Medication | Not specified | P | |

| AST (U/L) | 46 (14-120) | 43 (9-222) | 113 (21-2351) | 36 (14-80) | 0.008 |

| ALT (U/L) | 36 (15-283) | 46 (6-237) | 90 (23-785) | 28 (13-84) | 0.002 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.6 (0.3-28) | 0.6 (0.2-9.1) | 1.3 (0.4-12.8) | 0.5 (0.3-8) | 0.008 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.1-24) | 0.3 (0.1-6.2) | 0.6 (0.1-8.2) | 0.3 (0.1-5.8) | 0.141 |

| Alk Phosphotase (IU/L) | 323 (71-1616) | 355 (50-2288) | 313 (104 - 1905) | 135 (50-801) | 0.057 |

| GGT (U/L) | 140 (82-1856) | 106 (51-1066) | 233 (50-418) | 125 (N/A) | 0.881 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3.2 (1.7-4.3) | 3.3 (2.1-4.1) | 3.1 (2.5-4.5) | 3.6 (1.2-4.3) | 0.826 |

| INR | 1.2 (1-2.4) | 1.1 (0.9-1.7) | 1.1 (0.9-1.9) | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) | 0.106 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.8 (1.6-9.2) | 6.4 (4.7-8.6) | 5.8 (4.8-8.2) | 7.1 (5.2-10) | 0.111 |

| Platelets (103) | 161 (25-907) | 187 (10-708) | 80 (17-339) | 188 (78-352) | 0.022 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 59 (3-132) | 43 (0-121) | 24 (13-117) | 35 (6-127) | 0.687 |

The most common pattern of liver abnormalities was cholestasis (76%) followed by mixed (10%) and hepatocellular (8%) (Table 5). We did not identify a difference in the pattern of liver test abnormalities between varying causes of non-obstructive SD (P = 0.54). The majority of patients (78.4%) had SD localized to Zone III. Fibrosis was found in 37 patients and 17 of them were limited to portal fibrosis without septa involvement (stage 1/4) (Table 6). Patients with autoimmune or inflammatory diseases had higher proportion of fibrosis on liver biopsy (39%) followed by medication (32%) and malignancy (19%) (Table 6). Hepatocellular plate atrophy and RBC extravasation were found in 58% and 32% of the study population respectively. Patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disorder also had higher proportion of hepatocellular plate atrophy (75%) followed by malignancy (52%) and medication related (42%). Nodular regenerative hyperplasia and hepatic peliosis were identified on histopathology in nine patients (10%) and one patient (1%) respectively. Lymphocytic infiltration was identified in twenty-four patients (27%) (Table 6).

| Malignancy | Inflammatory state | Medication | Not specified | P | |

| Liver injury | 0.536 | ||||

| Hepatocellular | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |

| Cholestasis | 16 | 21 | 14 | 16 | |

| Mixed | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Normal | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Malignancy (n = 21) | Inflammatory state (n = 28) | Medications (n = 19) | Not specified (n = 20) | Total | P | |

| Zone III II and III I, II, and III Other | 0.82 | |||||

| 17 (81) 1 (5) 1 (5) 2 (10) | 22 (79) 3 (11) 0 (0) 3 (11) | 16 (84) 1 (5) 1 (5) 1 (5) | 14 (70) 3 (15) 0 (0) 3 (15) | 69 8 2 9 | ||

| METAVIR score | 0.60 | |||||

| 0 | 15 (71) 3 (14) 1 (5) 0 (0) | 14 (50) 6 (21) 4 (14) 1 (4) | 13 (68) 3 (16) 1 (5) 2 (11) | 9 (45) 5 (25) 3 (15) 2 (10) | 51 17 9 5 | |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| 3 | ||||||

| Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | 1(5) | 2 (7) | 4 (21) | 2 (10) | 9 | 0.33 |

| Hepatic peliosis | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.36 |

| Lymphocytic infiltration | 6 (29) | 8 (29) | 6 (32) | 4(20) | 24 | 0.77 |

| RBC extravasation | 8 (38) | 8 (29) | 7 (37) | 5 (25) | 28 | 0.76 |

| Hepatocellular plate atrophy | 11 (52) | 21 (75) | 8 (42) | 11 (55) | 51 | 0.13 |

The median follow up for all patients was 437 d (0-5616 d). Thirty seven patients (42%) died during the study follow up. Nineteen patients in our study died within one year after diagnosis of SD. The one-year mortality was highest in the medication related group (47%) followed by malignancy group (19%) and inflammatory group (14%). Ten patients died from complications of their respective underlying disease, such as: High burden of malignancy or infections related to immunosuppression. Four patients died from conditions unrelated to the cause of non-obstructive SD and in five patients the cause of death was not identified. Fifty out of sixty-nine patients (72%) that survived had at least 1 year of follow-up with a median follow-up time of 1943 d (370-5616 d).

Our cohort included 20 patients with unspecified cause of non-obstructive SD. The median age of diagnosis in this subgroup was 53 years (range: 16-85 years) with a median follow up of 636 d (range: 11-4120 d). Six patients (30.0%) from this subgroup died with median time to death of 2711 d (range: 146-5518 d) and 2 patients (10%) died within one-year of SD diagnosis.

The main findings of this study are that a significant proportion of SD occurs in the absence of impaired hepatic venous outflow. Twenty-eight percent (19/69) of patients with follow-up of at least one year died within one year after non-obstructive SD diagnosis, which might reflect poor clinical status or high disease burden in this study population. Medication related non-obstructive SD was associated with elevated serum AST and ALT levels but lower platelet counts compared to other causes. This observation correlates with a higher prevalence of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension in this group. A subset of these patients may have developed early SOS in the setting of recent chemotherapy exposure, such as oxaliplatin, despite the lack of typical histologic features. No patients had a history of stem cell transplantation. We did not identify a relationship between the extent of SD, hepatocellular plate atrophy, lymphocytic infiltration, or RBC extravasation with a specific etiology of non-obstructive SD. Our findings suggest that non-obstructive SD likely occurs through a common pathway associated with various medical conditions. Several studies have suggested the role of both IL-6 and VEGF overexpression in the development of SD[2,3]. Furthermore, the same IL-6 and its soluble receptor (sIL-6R) have been shown to be upregulated in chronic inflammatory or autoimmune conditions. In our cohort, one patient had a markedly elevated serum IL-6 level (249.1 pg/mL, normal range: 0-12.2 pg/mL). This was obtained as part of his extensive rheumatological work up. Unfortunately, this patient was not included in our final analysis due to the absence of echocardiogram to exclude right-sided heart failure, although he had no suggestive cardiac symptoms. Furthermore, the median serum CRP in our cohort was significantly elevated suggesting a role of chronic inflammatory state in the development of SD.

The prevalence of SD without hepatic venous outflow impairment has been reported in several small case series[1,14]. Bruguera et al[14] reported the a 2.9% incidence of non-obstructive SD on consecutive liver biopsy, while Kakar et al[1] reported one in three patients with diagnosis of SD occurred in the absence of venous outflow impairment. In our study, we found that 18% of all cases of sinusoidal dilatation occurred in the absence of venous outflow obstruction, or hepatic malignancy. This supports the previous studies indicating that non-obstructive SD may be more common than expected. The clinical significance of non-obstructive SD on histopathology is unclear, although we identified a high one-year mortality rate in our cohort. The majority of patients that died had coexisting malignancy (58%) and/or an autoimmune/inflammatory condition (29%). Seventy nine percent of patients died from either high burden of disease or complications of their underlying medical condition, such as malignancy. This brings forward a question of whether or not asymptomatic patients with abnormal liver enzymes and non-obstructive SD on biopsy require further evaluation for occult malignancy or inflammatory conditions. In our cohort of patients with undefined cause of SD, the one year mortality rate was low and interestingly all patients died from systemic infections. Future studies should evaluate the utility of screening for inflammatory/autoimmune condition or malignancy in patients with abnormal liver enzymes without an obvious cause of non-obstructive SD.

We were also interested in determining whether or not there is distinct biochemical, radiological, or histological patterns associated with specific medical conditions in patients with non-obstructive SD. We found that medication associated non-obstructive SD, such as previous exposure to platinum-based chemotherapy or purine analogs, were associated with higher median serum AST (113 U/L, P = 0.008) and ALT (90 U/L, P = 0.002) levels. This was consistent with previously reported findings highlighting the hepatotoxic nature of both oxaliplatin and 5-FU even after cessation of treatment[10,15-20].

We did not identify a relationship between the presence of hepatic nodules on imaging with nodular regenerative hyperplasia or peliosis hepatis on histopathology.

The strengths and weaknesses of our study merit further discussion. The major strength of our study was that this is the largest study to date on isolated non-obstructive SD. Previous studies were limited to case reports or small case series[1,14]. In addition, we have longitudinal data, up to 10 years after the initial diagnosis in majority of the patients. There were several limitations to our study: (1) As a tertiary center, a significant proportion of our cohort was referred for a second opinion of abnormal liver enzymes and had significant medical comorbidities, which may affect our one-year mortality rates and duration of follow up; (2) follow up data was not available in all patients, but the majority (69 out of 88 patients) had at least one-year follow up; (3) there were a large proportion of undefined causes of non-obstructive sinusoidal dilatation, which reflects the need for high quality prospective studies on this condition; and (4) we utilized our best clinical judgment based on available clinical data and histologic findings when selecting the primary etiology of non-obstructive SD in the setting of multiple medical conditions and/or history of medication exposure.

In conclusion, the finding of non-obstructive SD on liver biopsy should prompt a review of patient’s medical history and drug exposure. Additionally, portal hypertension should be rule out either clinically, endoscopically or radiographically. There does not appear to be a relationship between histological patterns and medical conditions, which may suggest overlapping biological pathways in the development of non-obstructive sinusoidal dilatation.

A proportion of patients demonstrate (SD) in the absence of post-sinusoidal venous outflow impairment or portal vein thrombosis and the clinical significance of this finding is unclear. Long-term outcomes of patients with SD are not known. Moreover, there is no clear guidance on how such patients are to be investigated.

To better understand the clinical relevance and long-term outcomes of patients with non-obstructive SD.

To better characterize isolated non-obstructive SD by identifying associated conditions, laboratory findings, and histological patterns.

Retrospective chart review of patients with isolated non-obstructive SD.

Inflammatory conditions (32%) were the most common cause identified. The most common pattern of liver abnormalities was cholestatic (76%). The majority (78%) had localized SD localized to Zone III. Medication-related SD had higher proportion of portal hypertension (53%), ascites (58%), and median AST (113 U/L) and ALT (90 U/L) levels. Nineteen patients in our study died within one-year after diagnosis of SD. Ten patients died from complications related to underlying diseases associated with SD.

Significant proportion of SD may exist without impaired hepatic venous outflow. There does not appear to be any relationship between histological patterns and medical conditions. High one-year mortality rate in our cohort may suggest relationship between clinical status and development of SD. Isolated SD on liver biopsy, in the absence of congestive hepatopathy, requires further evaluation and portal hypertension should be rule out.

Future studies should evaluate the utility of screening for inflammatory/autoimmune condition or malignancy in patients with non-obstructive SD without an obvious cause.

| 1. | Kakar S, Kamath PS, Burgart LJ. Sinusoidal dilatation and congestion in liver biopsy: is it always due to venous outflow impairment? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:901-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schirmacher P, Peters M, Ciliberto G, Blessing M, Lotz J, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Rose-John S. Hepatocellular hyperplasia, plasmacytoma formation, and extramedullary hematopoiesis in interleukin (IL)-6/soluble IL-6 receptor double-transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:639-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Maione D, Di Carlo E, Li W, Musiani P, Modesti A, Peters M, Rose-John S, Della Rocca C, Tripodi M, Lazzaro D. Coexpression of IL-6 and soluble IL-6R causes nodular regenerative hyperplasia and adenomas of the liver. EMBO J. 1998;17:5588-5597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Dill MT, Rothweiler S, Djonov V, Hlushchuk R, Tornillo L, Terracciano L, Meili-Butz S, Radtke F, Heim MH, Semela D. Disruption of Notch1 induces vascular remodeling, intussusceptive angiogenesis, and angiosarcomas in livers of mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:967-977.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Croquelois A, Blindenbacher A, Terracciano L, Wang X, Langer I, Radtke F, Heim MH. Inducible inactivation of Notch1 causes nodular regenerative hyperplasia in mice. Hepatology. 2005;41:487-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marzano C, Cazals-Hatem D, Rautou PE, Valla DC. The significance of nonobstructive sinusoidal dilatation of the liver: Impaired portal perfusion or inflammatory reaction syndrome. Hepatology. 2015;62:956-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Scoazec JY, Marche C, Girard PM, Houtmann J, Durand-Schneider AM, Saimot AG, Benhamou JP, Feldmann G. Peliosis hepatis and sinusoidal dilatation during infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). An ultrastructural study. Am J Pathol. 1988;131:38-47. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Fiorillo A, Migliorati R, Vajro P, Pellegrini F, Caldore M. Hepatic sinusoidal dilatation in the course of histiocytosis X. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1983;2:332-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saadoun D, Cazals-Hatem D, Denninger MH, Boudaoud L, Pham BN, Mallet V, Condat B, Brière J, Valla D. Association of idiopathic hepatic sinusoidal dilatation with the immunological features of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Gut. 2004;53:1516-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lu QY, Zhao AL, Deng W, Li ZW, Shen L. Hepatic histopathology and postoperative outcome after preoperative chemotherapy for Chinese patients with colorectal liver metastases. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hartleb M, Gutkowski K, Milkiewicz P. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: evolving concepts on underdiagnosed cause of portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1400-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Crocetti D, Palmieri A, Pedullà G, Pasta V, D'Orazi V, Grazi GL. Peliosis hepatis: Personal experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13188-13194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | DeLeve LD, Kaplowitz N. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1995;24:787-810. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bruguera M, Aranguibel F, Ros E, Rodés J. Incidence and clinical significance of sinusoidal dilatation in liver biopsies. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:474-478. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Rubbia-Brandt L, Audard V, Sartoretti P, Roth AD, Brezault C, Le Charpentier M, Dousset B, Morel P, Soubrane O, Chaussade S. Severe hepatic sinusoidal obstruction associated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:460-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 752] [Cited by in RCA: 774] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Mehta NN, Ravikumar R, Coldham CA, Buckels JA, Hubscher SG, Bramhall SR, Wigmore SJ, Mayer AD, Mirza DF. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pawlik TM, Olino K, Gleisner AL, Torbenson M, Schulick R, Choti MA. Preoperative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: impact on hepatic histology and postoperative outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:860-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kandutsch S, Klinger M, Hacker S, Wrba F, Gruenberger B, Gruenberger T. Patterns of hepatotoxicity after chemotherapy for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1231-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peppercorn PD, Reznek RH, Wilson P, Slevin ML, Gupta RK. Demonstration of hepatic steatosis by computerized tomography in patients receiving 5-fluorouracil-based therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:2008-2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Agostini J, Benoist S, Seman M, Julié C, Imbeaud S, Letourneur F, Cagnard N, Rougier P, Brouquet A, Zucman-Rossi J. Identification of molecular pathways involved in oxaliplatin-associated sinusoidal dilatation. J Hepatol. 2012;56:869-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiu KW, Kamimura K, Snyder N, Tajiri K S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW