Published online Apr 26, 2014. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i2.248

Revised: December 14, 2013

Accepted: January 13, 2014

Published online: April 26, 2014

Processing time: 222 Days and 18.8 Hours

AIM: To find a safe source for dopaminergic neurons, we generated neural progenitor cell lines from human embryonic stem cells.

METHODS: The human embryonic stem (hES) cell line H9 was used to generate human neural progenitor (HNP) cell lines. The resulting HNP cell lines were differentiated into dopaminergic neurons and analyzed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and immunofluorescence for the expression of neuronal differentiation markers, including beta-III tubulin (TUJ1) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). To assess the risk of teratoma or other tumor formation, HNP cell lines and mouse neuronal progenitor (MNP) cell lines were injected subcutaneously into immunodeficient SCID/beige mice.

RESULTS: We developed a fairly simple and fast protocol to obtain HNP cell lines from hES cells. These cell lines, which can be stored in liquid nitrogen for several years, have the potential to differentiate in vitro into dopaminergic neurons. Following day 30 of differentiation culture, the majority of the cells analyzed expressed the neuronal marker TUJ1 and a high proportion of these cells were positive for TH, indicating differentiation into dopaminergic neurons. In contrast to H9 ES cells, the HNP cell lines did not form tumors in immunodeficient SCID/beige mice within 6 mo after subcutaneous injection. Similarly, no tumors developed after injection of MNP cells. Notably, mouse ES cells or neuronal cells directly differentiated from mouse ES cells formed teratomas in more than 90% of the recipients.

CONCLUSION: Our findings indicate that neural progenitor cell lines can differentiate into dopaminergic neurons and bear no risk of generating teratomas or other tumors in immunodeficient mice.

Core tip: The use of pluripotent cells as a source for the generation of neuronal tissue for transplantation suffers from the risk of teratoma formation. To circumvent this problem, we have developed a simple and fast protocol to obtain human neural progenitor (HNP) cell lines from embryonic stem cells. These HNP cell lines have the potential to differentiate in vitro into dopaminergic neurons. After injection into immunodeficient SCID/beige mice, they did not form tumors even after 6 mo. These findings indicate that HNP cell lines can differentiate into dopaminergic neurons and bear no risk of generating teratomas in immunodeficient mice.

- Citation: Liao MC, Diaconu M, Monecke S, Collombat P, Timaeus C, Kuhlmann T, Paulus W, Trenkwalder C, Dressel R, Mansouri A. Embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitors as non-tumorigenic source for dopaminergic neurons. World J Stem Cells 2014; 6(2): 248-255

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v6/i2/248.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v6.i2.248

The derivation of human embryonic stem (hES) cells from human embryos[1] has opened new perspectives for stem cell-based therapies of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, and for the development of new drug screening platforms. These scenarios have been stimulated by the recently established procedures to generate induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from human fibroblasts or other tissues[2,3]. In fact, iPS cells may help to circumvent major ethical problems related to human embryonic stem cells. Similar to hES cells, iPS cells are pluripotent and therefore capable of differentiation into tissues of all three germinal layers in vitro[2] and also in vivo as they can give rise to teratomas when injected into immunodeficient mice[2].

In order to assess the potential of hES cells as a source for the derivation of tissues for cell replacement, several protocols have been established to generate various cell types from human embryonic stem cells, including subtypes of neuronal cells. However, it remains a matter of concern whether transplantation of hES cell-derived progenitors or even more differentiated cell types may lead to the formation of teratomas, a characteristic feature of pluripotent cells. It is assumed that most of these tumors observed following experimental transplantation of such in vitro differentiated cells are caused by a minor population or even single still pluripotent cells contaminating the grafts[4,5]. Therefore we established a simple and fast protocol to derive human neural progenitors (HNP) from hES cells. These neural progenitors can be maintained in culture for several weeks and can be stored for at least five years in liquid nitrogen without losing their capacity to differentiate into midbrain dopaminergic neurons.

To examine whether hES cell-derived neural progenitor cells still have the risk to form teratomas, cells were injected subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice. Remarkably, no tumors were detected even six months after injection of up to 2 × 106 HNP cells.

The Robert-Koch Institute in Berlin has approved working with hES cell lines H1 and H9 imported from WiCell (Madison, Wisconsin, United States) in compliance with German law (AZ. 1710-79-1-4-5). Human ES cells H9 were cultured as described previously[1]. Briefly, cells were plated on mitomycin C-inactivated mouse fibroblasts (1.9 × 104 cells/cm2) in KnockOut medium (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 20% KnockOut serum replacement (KSR) (Life Technologies), 2 mmol/L glutamine, 1 mmol/L non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (Life Technologies), 0.1 mmol/L beta-mercaptoethanol, 5 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Pepro Tech, Hamburg, Germany) and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Life Technologies). Cells grown to 70% confluence were dissociated using accutase (PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany) in the presence of Rock Inhibitor Y27632 (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), and split 1 to 3 or 1 to 5. The neural induction medium consisted of KnockOut medium containing 15% KSR (Gibco, Life Technologies), 2 mmol/L glutamine, 200 ng/mL noggin (R and D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) or 2 μmol/L dorsomorphin (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mmol/L NEAA, 0.1 mmol/L beta-mercaptoethanol, and P/S. The HNP medium consisted of Neurobasal medium (Life Technologies) containing N2 and B27 supplements (Life Technologies), 20 ng/mL bFGF, 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Pepro Tech GmbH), 0.2 mmol/L ascorbic acid, and 2000 U/mL human leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany).

HNP cells [(5-7.5) × 105] were seeded on matrigel coated 3.5 cm culture dishes. The next day the cells were fed with neural differentiation medium (Neurobasal medium, 1 mmol/L NEAA, 1 × P/S, 2 mmol/L glutamine, N2 and B27 supplements minus Vitamin A, 0.2 mmol/L ascorbic acid, 100 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) (R and D Systems), 100 ng/mL Sonic hedgehog (SHH) (R and D Systems) or 1-2 μmol/L purmorphamine (Cayman Chemical, Biomol, Hamburg, Germany). Medium was changed every other day. After two weeks, the cells were fed with neural differentiation medium containing 20 ng/mL glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (Pepro Tech), 20 ng/mL brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Pepro Tech), 1 ng/mL transforming growth factor (TGF)-β3 (R and D Systems), and 0.5 mmol/L dibutyryl-cAMP (dbcAMP) (Sigma Aldrich) without FGF8, SHH or purmorphamine to induce neuron maturation. Cells were analyzed after day 30 of the differentiation procedure. The HNP freezing medium consisted of the HNP medium with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Medium for culture of PA6 cells was Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Life Technologies).

For immunofluorescence staining, cells grown on glass coverslips (BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed for 10 mo in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Primary antibodies were used to detect nestin (MAB1259, 1:750; R and D Systems), musachi (ab21628, 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), CD133 (ab 19898, 1:200; Abcam), beta-III tubulin (TUJ1) (MMS-435P, 1:1000; Covance, Princeton, NJ, United States), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (AB152, 1:300; Millipore), and paired box protein 6 (PAX6) (PRB278P, 1:300; Covance). As secondary antibodies, we used Alexa 488-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A-21206, 1:750; Life Technologies), Alexa 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-11008, 1:750; Life Technologies), Alexa 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (A-11001, 1:750; Life Technologies), Alexa 594-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A-21207, 1:750; Life Technologies), and Alexa 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-11012, 1:750; Life Technologies).

Neural progenitors and differentiated neurons were collected and total RNA extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA (1 μg) was used for cDNA synthesis with the QuantiTect Rev Transcription Kit (Qiagen) in 20 μL reaction volume. 20 μL cDNA were diluted in 60 μL RNase-free water and subsequently 2 μL were used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (q-RTPCR) amplification. Each q-RTPCR reaction was run in a 10 μL reaction volume containing 1 μL of the QuantiTect Primers (Qiagen) and 5 μL 2 × qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystem, Woburn, MA, United States). The following QuantiTect Primers were used: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (QT01192646), LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 (LMX1A) (QT00048055), pituitary homeobox 3 (PITX3) (QT01006047), nuclear receptor related 1 protein (NURR1) (QT00037716), neurogenin-2 (NGN2) (QT00020447), paired box protein 6 (PAX6) (QT00071169), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (QT00081151), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (QT00067221), and dopamine transporter (DAT) (QT00000231). All q-RTPCRs were performed with a Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Animal experiments were approved by the local government. Rats (LOU/c) were conventionally housed in the central animal facility of the University Medical Center Göttingen. Severe combined immunodeficient SCID/beige (C.B-17/IcrHsd-scid-bg) mice were kept under pathogen-free conditions as they lack T and B-lymphocytes and have no functional natural killer (NK) cells. A subgroup of rats received daily intraperitoneal injections of cyclosporine A (CsA) (10 mg/kg, Sandimmune, Novartis Pharma, Nürnberg, Germany) commencing two days before grafting. For the analysis of subcutaneous tumor growth, the cells were injected in 100 μL PBS into the flank of the animals. Tumor growth was monitored regularly by palpation. Animals were sacrificed 3 or 6 mo after injection and autopsies were performed. Tumor tissue or subcutaneous tissue at the site of injection was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, later placed in phosphate-buffered 4% formalin for 16 h and then embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections (2.5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological examination.

Teratoma frequencies were analyzed with contingency tables using WinSTAT software (R. Fitch Software, Bad Krozingen, Germany).

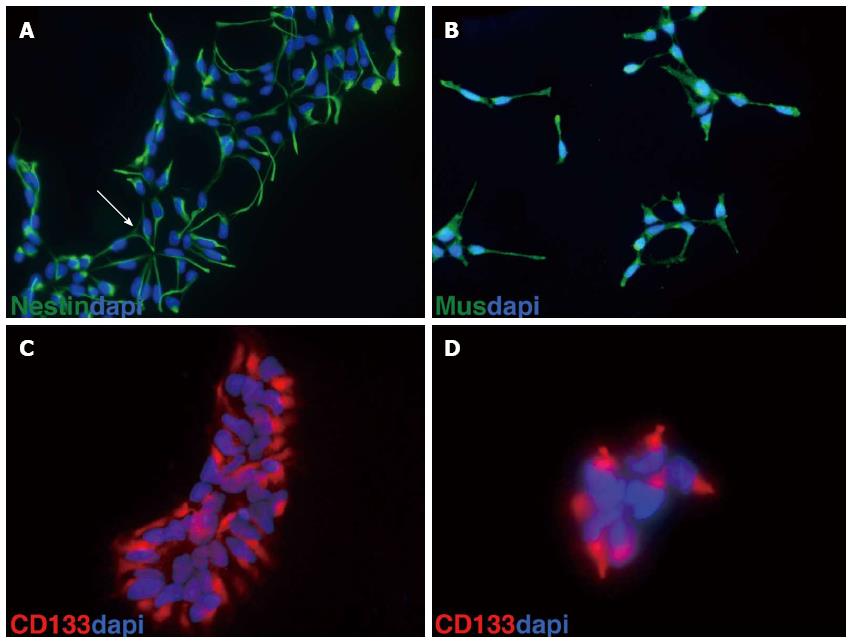

Using a monolayer of the stromal cell line PA6, mouse and human ES cells can be differentiated into neuronal cells with a high proportion of neurons displaying mesencephalic dopaminergic fate[6]. We have established a procedure to culture mouse ES cells on PA6 cells to generate mouse neuronal progenitors (MNP) that can be frozen or maintained in culture for several passages[7,8]. Human ES cells were first cultured for two passages in hES medium[1] before subjection to neural differentiation. Cells were passaged using accutase in the presence of the Rock Inhibitor Y27632[9]. Then, 9 × 104 hES cells were plated on a feeder layer of mitomycin C-inactivated PA6 cells on a 3.5 cm dish and cultured for 36 h in hES medium[1]. Afterwards, the medium was replaced by neural induction medium containing noggin (200 ng/L) or dorsomorphin (2 μmol/L)[10]. Half of the medium was replaced every other day. The onset of neuronal differentiation was monitored by the appearance of neural rosettes, the first of which was usually recognized at day 11 after plating hES cells on PA6 stromal cells. Neural rosettes were individually picked under the stereomicroscope. Cell aggregates were transferred to gelatinized 24-well-plates and cultured in HNP medium consisting of Neurobasal medium containing N2 and B27 supplements, ascorbic acid, NEAA, 10 ng/mL bFGF, 10 ng/mL EGF, and 2000 U/mL LIF. After 4-5 d, cells from each well were treated with accutase and passaged on two gelatinized wells of a 24-well-plate. When cells reached 60%-70% confluence, they were passaged to one gelatinized 3.5 cm plate. Only those cells were further processed that continuously formed neural rosettes. When confluent (60%-70%), cells were further treated with accutase and stored in 1 mL of HNP freezing medium containing 10% DMSO in liquid nitrogen. Cells can be stored for years in liquid nitrogen. So far our cells have been in storage for 5 years. When thawed, frozen cells were brought to 37 °C in a water bath, transferred into 9 mL of HNP medium, and centrifuged for 5 mo at 200 g. The cell pellet was resuspended in 2 mL of HNP medium and plated on a gelatin-coated 3.5 cm dish. Cells were usually split 1 to 3 every 4-5 d. So far, HNP cells were kept in culture for about two months (16 passages) without losing their capacity to differentiate into dopaminergic neurons. However, the percentage of dopaminergic neurons varied between different HNP clones. Each HNP clone originated from one neural rosette. HNP cells usually consist of a homogenous population expressing the stem cell markers nestin, musachi and CD133 (prominin 1) (Figure 1).

In order to generate dopaminergic neurons, HNP cells were dissociated into single cells and plated at a density of (5-7.5) × 105 cells onto matrigel-coated 3.5 cm culture dishes or glass coverslips in HNS medium. At the second day after plating, the HNP medium was supplemented by FGF8 and SHH (or purmorphamine). After 2 wk, neuron maturation was induced by replacing FGF8 and SHH by GDNF, BDNF, TGF-β3 and dbcAMP. Cells were analyzed after day 30 of the differentiation procedure.

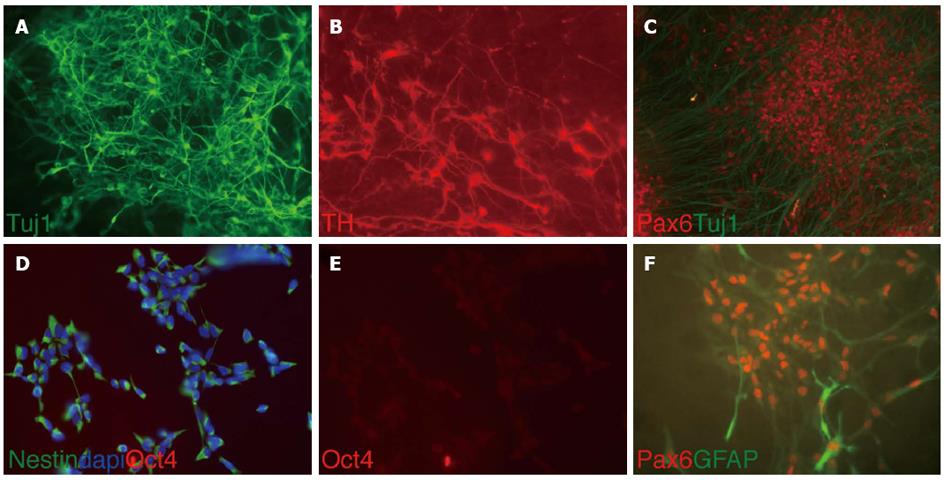

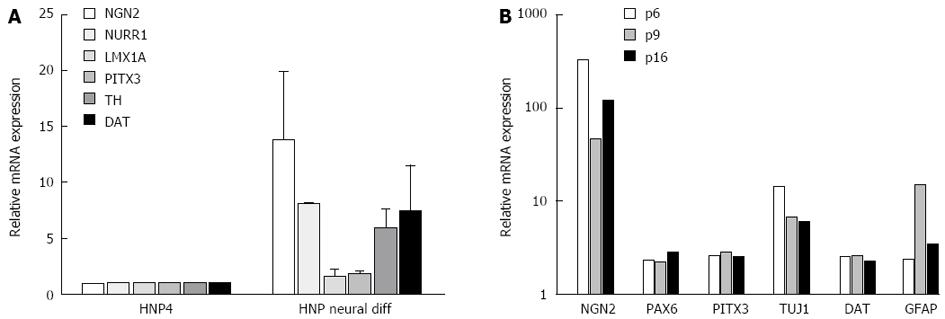

The majority of the differentiated cells obtained from HNP4 cells at passage 16 expressed the neuronal marker TUJ1 and a high proportion of these were positive for TH, indicating the development of dopaminergic neurons as shown in Figure 2. In addition, PAX6, a marker of midbrain tegmentum, was detected. Moreover, we performed q-RTPCR to analyze the expression of several neuronal markers that were previously described to label midbrain dopaminergic neurons, such as NGN2, PITX3, TH and DAT[11-13] (Figure 3A).

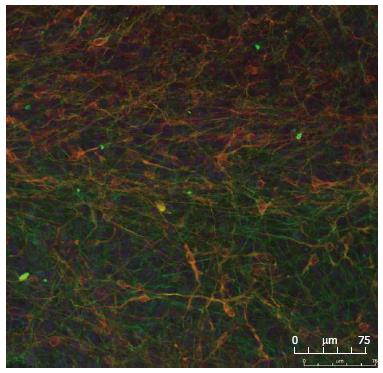

It has been reported that the number of dopaminergic neurons may decrease when progenitor cells are maintained for longer periods in culture. We therefore monitored midbrain dopaminergic markers in cultures obtained at different passages of HNP4 cells by q-RTPCR. Neuronal marker genes, such as NGN2, PITX3, PAX5, TUJ1 and DAT, were expressed at a similar level in cultures obtained from HNP4 cells at passages 6, 9 and 16 (Figure 3B). The expression of TUJ1 and TH proteins in neuronal cells differentiated from HNP4 cells at passage 16 were detected by confocal microscopy (Figure 4). Thus, HNP cells retain their capacity to differentiate into dopaminergic neurons even after a higher number of passages.

To determine the risk of tumor growth after transplantation of mouse neural progenitor cells, we injected 1 × 106 MNP cells subcutaneously into B, T and NK cell deficient SCID/beige mice (n = 9). No tumors developed after injection of MNP cells (at passage 20) derived from mES cells (MPI-II) in the following 3 mo (Table 1). Importantly, injection of 1 × 106 mES cells or neuronal cells differentiated from mES cells resulted in teratoma growth in more than 90% of the recipients[4]. Thus, the teratoma frequencies were significantly different after injection of these cell types (P = 1.47 × 10-7). Our previous studies revealed that the risk of teratoma growth could be higher after injection of differentiated cells as compared to undifferentiated mES cells when CsA-treated rats were used as recipients[4]. Therefore, we also injected the MNP cells into rats receiving CsA (10 mg/kg per day) for immunosuppression. Again, no tumors were observed after three months (Table 1), indicating a significantly reduced risk for tumor formation after injection of MNP cells compared to mES cells and neuronal cells differentiated from mES cells (P = 1.9 × 10-6). Similarly, two human HNP cell lines (HNP1 and HNP4) at passages between 10 and 21 did not form tumors in immunodeficient SCID/beige mice even within 6 mo after subcutaneous injection in contrast to hES cells H9 (Table 2). The teratoma frequencies were significantly different comparing mice injected with HNP1 or HNP3 and hES H9 cells (P = 0.00013). We did not find leftovers of the injected HNP cells, such as neural rosettes, in the subcutaneous tissue at the site of injection (data not shown), suggesting that the HNP cells did not survive.

| SCID/beige | LOU/c + CsA | |

| MNP | 0% (0/9) | 0% (0/9) |

| mES cells | 93% (13/14) | 0% (0/25) |

| Neuronal cells differentiated from mES cells | 94% (17/18) | 61% (11/18) |

| SCID/beige | |

| HNP1 p9, 1 x 106 | 0% (0/6) |

| HNP1 p19, 2 x 106 | 0% (0/3) |

| HNP4 p10, 1 x 106 | 0% (0/3) |

| HNP4 p21, 2 x 106 | 0% (0/9) |

| hES cells (H9) | 75% (3/4) |

The formation of tumors, either teratomas and teratocarcinomas or tumors with a more restricted tissue composition, after transplantation of cells or tissues derived from pluripotent stem cells remains a major problem for the therapeutic application of these cells in regenerative medicine[14]. The assessment of the tumorigenicity of stem cell-derived grafts is complicated by the fact that it depends heavily on the immune response of the recipient[5,15]. Grafts that do not form tumors in xenogeneic or allogeneic hosts due to immune rejection might form tumors in syngeneic recipients[4]. The finding that cellular grafts derived from ES cells do not form tumors in xenogeneic recipients[16] must not indicate that the graft is safe in an allogeneic or even syngeneic recipient[4]. Moreover, in a previous study, we found that grafts obtained after neuronal differentiation of mES cells (MPI-II) for 14 d formed teratomas in CsA-treated rats (Table 1). Surprisingly, undifferentiated mES cells did not form tumors in these hosts[4]. Mouse ES cells turned out to be highly susceptible to NK cells and were rejected by NK cells[4,17]. Thus, differentiation cultures of mES cells apparently can give rise to cells that have, in certain hosts, an even stronger tumorigenic capacity than undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells.

It is a major challenge to produce cellular grafts directly from pluripotent stem cells and to avoid a contamination with tumorigenic cells. Strategies to remove tumorigenic cells from grafts include prolonged differentiation[18], cell sorting or selection[19-21], introduction of suicide genes[22,23], and killing of remaining undifferentiated cells before transplantation[24-26]. However, all grafts that are derived from pluripotent stem cells are in principle at risk of containing tumor-forming cells[14]. As few as 2 mouse ES cells[27] or 245 human ES cells[28] were reported to form teratomas in immunodeficient mice.

Therefore, it might be a more promising alternative to differentiate therapeutic grafts from pre-differentiated progenitor cell lines, which are not able to form tumors even in immunodeficient hosts. We have shown that mouse and human neural progenitor cells do fulfill this prerequisite. Both did not form tumors after injection in SCID/beige mice, which are deficient for T and B cells and that do not have functional NK cells. The mice were observed for 3 mo after injection of MNP cells and even 6 mo after injection of HNP cells before autopsy. MNP cells[8] were compared with mES cells and neuronal cells directly differentiated from these mES cells (Table 1). Only MNP cells were safe and failed to form teratomas. Moreover, MNP cells also did not form tumors in CsA-treated rats, in which neuronal cells directly differentiated from mES cells formed teratomas in 61% of the animals[4]. In this study, subcutaneous injections were performed to assess the tumor risk after injection of neuronal progenitor cell lines. The subcutaneous tissue usually does not promote the survival of neuronal cells over several months and we indeed did not detect leftovers of the HNP cells at the site of injection. Importantly, the results indicate that MNP and HNP cell lines do not have the capacity to form tumors. Thus, these cells are apparently a much safer cell type for differentiation of neuronal grafts than ES cells, even without any selection strategy to remove the progenitor cells from differentiation cultures. The HNP cell lines were tested at passages between 9 and 21 for their capability to differentiate into dopaminergic neurons in vitro and to form tumors in vivo. The HNP cell lines differentiated with similar efficacy and did not form tumors at earlier and later passages. These data now encourage the testing of cell survival and therapeutic efficacy of dopaminergic neurons differentiated from these neuronal progenitor cell lines after intrastriatal transplantation in models of Parkinson’s disease. The potential therapeutic efficacy of dopaminergic neurons derived from human ES cells has been recently demonstrated in xenotransplantation models using rats and rhesus macaques[29]. However, this experimental setting cannot exclude a tumor risk after an allogeneic or even autologous transplantation of stem cell-derived human grafts[5].

In conclusion, our findings clearly indicate that neural progenitor cells derived from mouse and human embryonic stem cells do not have the potential to generate teratomas or other tumors even up to six months following injection into immunodeficient animals. We think that this may also apply to iPS cell-derived neural progenitors. Our ongoing experiments using iPS cells derived from patients with Parkinson’s disease support this notion. Thus, such hES cell-derived neural progenitors represent a strategy to circumvent safety concerns when used for potential future stem cell-based therapies. Moreover, HNP cells from iPS cells of patients with Parkinson’s or other neurological diseases may be used for assessing alterations in neural differentiation properties or other defects that cannot be analyzed in patients.

We would like to thank Thomas Schulz, Angelika Mönnich and Leslie Elsner for excellent technical assistance.

The establishment of human embryonic stem cells has opened new perspectives for the development of cell-based therapies for treatment, e.g., of neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease. The use of pluripotent cells as a source for the generation of tissue for transplantation suffers from the risk of teratoma formation, an inherent feature of pluripotent cells.

Numerous strategies were suggested in the literature to deplete tumor-forming cells before grafting, including prolonged differentiation cultures. However, the authors of this study have shown previously that the risk of teratoma formation can even increase during differentiation culture due to an alteration of the immunological properties of the cells. To circumvent these problems, the authors of this study have developed mouse and human embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitor cell lines.

The authors describe a new protocol to obtain human neural progenitor cell lines from embryonic stem cells which is fast and simple. These cell lines, which can be stored for several years, are shown to differentiate in vitro into dopaminergic neurons. Notably, human as well as mouse neuronal progenitor cell lines did not form any tumors in immunodeficient mice.

Neural progenitor cell lines might be useful to differentiate dopaminergic neurons in vitro for transplantation in patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease. The neural progenitor cell lines appear to be a safer alternative for the generation of grafts compared to embryonic stem cells since they did not form tumors in immunodeficient mice.

Neural progenitor cell lines are cell lines derived from embryonic stem cells which can differentiate into neuronal cells, including dopaminergic neurons. Dopaminergic neurons are the neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain that are lost in Parkinson’s disease. Teratomas are tumors containing derivatives of all three germinal layers which can occur after transplantation of pluripotent stem cells.

In this manuscript, the authors generated both human and mouse neural precursor cell lines from embryonic stem cells. This study is very interesting and the writing style in this study was easy to follow.

| 1. | Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145-1147. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14327] [Cited by in RCA: 14570] [Article Influence: 809.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7589] [Cited by in RCA: 7335] [Article Influence: 386.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dressel R, Schindehütte J, Kuhlmann T, Elsner L, Novota P, Baier PC, Schillert A, Bickeböller H, Herrmann T, Trenkwalder C. The tumorigenicity of mouse embryonic stem cells and in vitro differentiated neuronal cells is controlled by the recipients’ immune response. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dressel R. Effects of histocompatibility and host immune responses on the tumorigenicity of pluripotent stem cells. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33:573-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kawasaki H, Mizuseki K, Nishikawa S, Kaneko S, Kuwana Y, Nakanishi S, Nishikawa SI, Sasai Y. Induction of midbrain dopaminergic neurons from ES cells by stromal cell-derived inducing activity. Neuron. 2000;28:31-40. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Conti L, Pollard SM, Gorba T, Reitano E, Toselli M, Biella G, Sun Y, Sanzone S, Ying QL, Cattaneo E. Niche-independent symmetrical self-renewal of a mammalian tissue stem cell. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 696] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mansouri A, Fukumitsu H, Schindehütte J, Krieglstein K. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2009;Chapter 3:Unit3.6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Watanabe K, Ueno M, Kamiya D, Nishiyama A, Matsumura M, Wataya T, Takahashi JB, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Muguruma K. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:681-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1505] [Cited by in RCA: 1593] [Article Influence: 83.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Morizane A, Doi D, Kikuchi T, Nishimura K, Takahashi J. Small-molecule inhibitors of bone morphogenic protein and activin/nodal signals promote highly efficient neural induction from human pluripotent stem cells. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:117-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Perrier AL, Tabar V, Barberi T, Rubio ME, Bruses J, Topf N, Harrison NL, Studer L. Derivation of midbrain dopamine neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12543-12548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in RCA: 715] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roybon L, Hjalt T, Christophersen NS, Li JY, Brundin P. Effects on differentiation of embryonic ventral midbrain progenitors by Lmx1a, Msx1, Ngn2, and Pitx3. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3644-3656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Daadi MM, Grueter BA, Malenka RC, Redmond DE, Steinberg GK. Dopaminergic neurons from midbrain-specified human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells engrafted in a monkey model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Knoepfler PS. Deconstructing stem cell tumorigenicity: a roadmap to safe regenerative medicine. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1050-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bifari F, Pacelli L, Krampera M. Immunological properties of embryonic and adult stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2010;2:50-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baier PC, Schindehütte J, Thinyane K, Flügge G, Fuchs E, Mansouri A, Paulus W, Gruss P, Trenkwalder C. Behavioral changes in unilaterally 6-hydroxy-dopamine lesioned rats after transplantation of differentiated mouse embryonic stem cells without morphological integration. Stem Cells. 2004;22:396-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dressel R, Nolte J, Elsner L, Novota P, Guan K, Streckfuss-Bömeke K, Hasenfuss G, Jaenisch R, Engel W. Pluripotent stem cells are highly susceptible targets for syngeneic, allogeneic, and xenogeneic natural killer cells. FASEB J. 2010;24:2164-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brederlau A, Correia AS, Anisimov SV, Elmi M, Paul G, Roybon L, Morizane A, Bergquist F, Riebe I, Nannmark U. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cells to a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: effect of in vitro differentiation on graft survival and teratoma formation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1433-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chung S, Shin BS, Hedlund E, Pruszak J, Ferree A, Kang UJ, Isacson O, Kim KS. Genetic selection of sox1GFP-expressing neural precursors removes residual tumorigenic pluripotent stem cells and attenuates tumor formation after transplantation. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1467-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fukuda H, Takahashi J, Watanabe K, Hayashi H, Morizane A, Koyanagi M, Sasai Y, Hashimoto N. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based purification of embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursors averts tumor formation after transplantation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:763-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kolossov E, Bostani T, Roell W, Breitbach M, Pillekamp F, Nygren JM, Sasse P, Rubenchik O, Fries JW, Wenzel D. Engraftment of engineered ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes but not BM cells restores contractile function to the infarcted myocardium. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2315-2327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schuldiner M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Benvenisty N. Selective ablation of human embryonic stem cells expressing a “suicide” gene. Stem Cells. 2003;21:257-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cao F, Lin S, Xie X, Ray P, Patel M, Zhang X, Drukker M, Dylla SJ, Connolly AJ, Chen X. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006;113:1005-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bieberich E, Silva J, Wang G, Krishnamurthy K, Condie BG. Selective apoptosis of pluripotent mouse and human stem cells by novel ceramide analogues prevents teratoma formation and enriches for neural precursors in ES cell-derived neural transplants. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:723-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Choo AB, Tan HL, Ang SN, Fong WJ, Chin A, Lo J, Zheng L, Hentze H, Philp RJ, Oh SK. Selection against undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells by a cytotoxic antibody recognizing podocalyxin-like protein-1. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1454-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hewitt Z, Priddle H, Thomson AJ, Wojtacha D, McWhir J. Ablation of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells: exploiting innate immunity against the Gal alpha1-3Galbeta1-4GlcNAc-R (alpha-Gal) epitope. Stem Cells. 2007;25:10-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lawrenz B, Schiller H, Willbold E, Ruediger M, Muhs A, Esser S. Highly sensitive biosafety model for stem-cell-derived grafts. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:212-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hentze H, Soong PL, Wang ST, Phillips BW, Putti TC, Dunn NR. Teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells: evaluation of essential parameters for future safety studies. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2:198-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kriks S, Shim JW, Piao J, Ganat YM, Wakeman DR, Xie Z, Carrillo-Reid L, Auyeung G, Antonacci C, Buch A. Dopamine neurons derived from human ES cells efficiently engraft in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2011;480:547-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1289] [Cited by in RCA: 1461] [Article Influence: 97.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers: Hwang DY, Petyim S S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN