Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v18.i2.113694

Revised: October 13, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 165 Days and 15.8 Hours

Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) hold significant therapeutic potential for regenerative medicine, particularly in wound healing, owing to their multipo

To investigate the mechanistic role of HIF-1α in mediating the enhanced survival and regenerative capacity of α-KG-preconditioned ADSCs in an acid burn wound model. Specifically, we sought to determine whether HIF-1α activation drives complementary adaptations in glutamine and glycogen metabolism to maintain redox and energy homeostasis, respectively, under the multifactorial stress con

Human ADSCs were isolated from lipoaspirates and preconditioned with dime

α-KG preconditioning significantly enhanced the survival of ADSCs both in vitro under stress and in vivo in burn wounds. This was concomitant with HIF-1α stabilization. Mechanistically, HIF-1α orchestrated a dual metabolic adaptation: (1) It promoted glutaminolysis via GLS1, increasing glutamate and GSH synthesis, which enhanced antioxidant capacity and reduced ROS levels; and (2) It simultaneously stimulated glycogen storage (Gys1 upregulation) and mobilization (Pygl upregulation), preserving energy (ATP:AMP ratio) during glucose deprivation. Genetic inhibition of GLS1 abrogated the ROS detoxification benefit, while PYGL knockdown abolished the energy maintenance advantage, both reducing survival. Crucially, combined inhibition of both pathways completely negated the prosurvival effect of α-KG, confirming their synergistic role. In vivo, α-KG-preconditioned ADSCs accelerated wound closure, improved re-epithelialization, and enhanced angiogenesis compared to controls, effects that were HIF-1α-dependent.

This study demonstrates that α-KG preconditioning significantly enhances ADSC survival and therapeutic efficacy in burn wound healing through HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming. HIF-1α activation coordinately upregulates glutamine-driven GSH synthesis for redox homeostasis and glycogen storage for bioenergetic resilience, providing a dual mechanism of cytoprotection. These findings establish metabolic preconditioning as a potent, translatable strategy to improve the efficacy of stem cell-based therapies not only in wound healing but potentially in other ischemic and inflammatory conditions characterized by poor cell survival.

Core Tip: This study reveals that preconditioning adipose-derived stem cells with α-ketoglutarate enhances their survival in burn wounds through hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-mediated dual metabolic adaptations. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α activation simultaneously promotes glutamine metabolism for antioxidant glutathione synthesis and enhances glycogen storage for energy maintenance under stress. This metabolic reprogramming strategy significantly improves cell viability and wound healing efficacy, offering a novel approach to enhance stem cell-based therapies in regenerative medicine.

- Citation: Dilimulati D, Dilimulati D, Cui L. Alpha-ketoglutarate enhances adipose-derived stem cells survival in wound healing by hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha-mediated redox homeostasis and glycogen-dependent bioenergetics. World J Stem Cells 2026; 18(2): 113694

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v18/i2/113694.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v18.i2.113694

Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) have emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for skin wound healing due to their accessibility, multipotency, and paracrine effects[1-3]. However, the clinical efficacy of stem cell therapy remains limited by the poor survival rate of transplanted cells in hostile wound environments, where hypoxia, nutrient dep

To enhance the therapeutic potential of cell-based therapies, preconditioning strategies have been developed to prepare cells ex vivo for the harsh in vivo environment, thereby improving their survival and functional performance after transplantation[11,12]. Hypoxic preconditioning, for instance, has shown beneficial outcomes in preclinical models of ischemic diseases affecting the brain, heart, and muscle[11,12]. These improvements have been attributed to altered cell behavior, including enhanced secretion of pro-angiogenic factors, recruitment of host cells, and autocrine signaling that promotes cell survival[11,12]. Recent advances in cancer research have highlighted the critical role of metabolic adaptations in enabling cell survival under hypoxic and nutrient-deprived conditions[13-15]. In hypoxic tumor cells, increased activity of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), particularly HIF-1α, orchestrates metabolic reprogramming to preserve energy and redox balance[16,17]. However, such metabolic adaptations remain understudied in the context of cell transplantation strategies for regenerative medicine, let alone the special research field of skin wound healing, despite their potential to significantly improve therapeutic outcomes.

In our previous work, we found that preconditioning ADSCs with α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) accelerated the healing of acid burn wounds and prolonged the survival of transplanted cells in mice[18]. This beneficial effect was associated with increased expression of HIF-1α and pro-angiogenic factors (vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2), leading to enhanced extracellular matrix deposition and microvascular density[18,19]. While this prior study established the therapeutic potential of α-KG preconditioning, the fundamental metabolic mechanisms underpinning the enhanced survival of ADSCs remain largely unexplored. Specifically, it is unknown whether and how HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming contributes to redox homeostasis and bioenergetic adaptation in the hostile wound microenvironment. To address this critical knowledge gap, the present study was designed to mechanistically dissect the role of α-KG preconditioning in ADSC survival. We selected α-KG as the preconditioning agent based on its dual role as a key metabolic intermediate and a known regulator of HIF-1α stability, positioning it as an ideal candidate to probe the link between metabolism and cell resilience.

Therefore, in this study, we systematically investigate the hypothesis that α-KG preconditioning enhances ADSC survival through HIF-1α-mediated coordination of complementary metabolic pathways. Utilizing a combination of genetic, pharmacological, and advanced metabolomic approaches, we aim to delineate the role of glutamine metabolism in maintaining redox balance via glutathione (GSH) synthesis, and elucidate the contribution of glycogen storage and mobilization in sustaining bioenergetics during nutrient stress. Our findings provide novel insights into the metabolic basis of stem cell survival, offering a rational strategy to optimize ADSC-based therapies for wound healing and beyond.

A total of eighteen specific pathogen-free BALB/c mice (male, 6-week-old, weighing 20 ± 2 g) were obtained from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). To ensure adequate statistical power and minimize bias, the sample size was determined based on preliminary data and power analysis (α = 0.05, β = 0.20, power = 80%), which indicated that n = 6 per group would be sufficient to detect a 30% difference in cell survival rates. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups using a computer-generated randomization sequence to avoid selection bias. All surgical and analytical procedures were performed by investigators blinded to the group assignments. Upon arrival, the animals were acclimatized for one week prior to experimentation in the specific pathogen-free-grade animal facility at the Experimental Animal Center of Tongji University School of Medicine. The mice were housed in standard polycarbonate cages

Human subcutaneous adipose tissue samples were obtained from healthy donors (n = 8, age range 23-56 years, body mass index range 22-30 kg/m2) undergoing elective abdominal liposuction procedures at the Department of Plastic Surgery of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University. All tissue collection procedures were performed after obtaining written informed consent from the donors, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Research Committee of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (Approval No. 25KN267).

For isolation of ADSCs, fresh lipoaspirates were processed within 2 hours of collection. The adipose tissue was extensively washed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4, Gibco, MA, United States) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin to remove blood cells and debris. The washed tissue was then enzymatically digested with an equal volume of 0.2% collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, NJ, United States) at

Mouse ADSCs were isolated from the inguinal adipose tissue of the BALB/c mice used in this study. Briefly, mice were euthanized, and the inguinal fat pads were aseptically excised. The adipose tissue was minced thoroughly and digested using 0.2% collagenase type I at 37 °C for 45-60 minutes with gentle agitation. The digestion was neutralized with complete culture medium (DMEM-LG with 10% FBS), and the cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer to remove debris. The SVF was collected by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 minutes. The SVF pellet was resuspended and seeded in culture dishes at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2. The culture medium was changed after 24 hours to remove non-adherent cells, and subsequently every 3 days. Mouse ADSCs were expanded and subjected to the same α-KG preconditioning protocol (3.5 mmol/L DM-αKG for 48 hours) as human ADSCs prior to in vivo transplantation.

Lentiviral transduction: To modulate gene expression in ADSCs, lentiviral-mediated transduction was performed. For silencing HIF-1α, GLS1, and PYGL expression, ADSCs were cultured in complete medium supplemented with 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States) and transduced with lentiviral particles carrying specific shRNAs: ShHIF-1α, shGLS1, and shPYGL (MISSION™, Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States). For ectopic overexpression, ADSCs were transduced with a lentivirus carrying a human GLS1 overexpression vector. In all experiments, a non-targeting scrambled shRNA sequence was used as a negative control. After 24 hours of transduction, the virus-containing medium was replaced with fresh culture medium, and the cells were maintained for an additional 48 hours before being utilized for subsequent experiments.

Inhibitors and intermediates of metabolic pathways: For metabolic pathway modulation in ADSCs, the following compounds were utilized: Bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,2,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES), glutamate, DM-α-KG, and 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-arabinitol (DAB) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MA, United States). For inhibitor treatments, ADSCs were exposed to DAB and BPTES at a final concentration of 10 μM. In metabolic rescue experiments, glutamate and DM-α-KG were supplemented at 0.5 mmol/L. All compounds were reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions and sterile filtered prior to addition to cell cultures.

Cell viability assay: Cell viability assessment was performed utilizing annexin V-propidium iodide (AnxV-PI) dual staining methodology (Annexin V Alexa Fluor® 488 & propidium iodide Dead Cell Apoptosis kit, Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States)[20]. For single-parameter stress conditions, cellular specimens were maintained for 72 hours under hypoxic conditions (0.5% O2) or in glucose-restricted medium (0.5 mmol/L glucose), or alternatively exposed to oxidative stress via hydrogen peroxide treatment (H2O2, 25 μM; Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States) for 12 hours. To evaluate cellular responses to multifactorial stress conditions, specimens were cultured under moderate hypoxia (1% O2) combined with glucose limitation (1 mmol/L) for 72 hours, with supplementation of H2O2 (12 μM) during the final 12-hour period. Following appropriate stress exposure, cells were harvested, subjected to PBS washing, and subsequently incubated with 1 × Annexin V conjugate and propidium iodide (1 μg/mL) at ambient temperature for 15 minutes in binding buffer. Quantitative analysis was conducted via flow cytometry (Gallios, Beckman Coulter, IN, United States), and the proportion of viable cells (AnxV-PI-) was determined using Kaluza™ analytical software (Beckman Coulter, IN, United States)[21].

Glycolysis assessment: For quantitative assessment of glycolytic flux, ADSCs were subjected to metabolic labeling through incubation for 2 hours in complete growth medium supplemented with 0.4 μCi/mL [5-3H]-D-glucose (PerkinElmer, CT, United States). Following the incubation period, culture medium was carefully transferred into hermetically sealed glass vials fitted with rubber stoppers. Tritiated water (3H2O), generated as a byproduct of glycolysis, was captured via vapor phase transfer using a hanging well apparatus containing Whatman filter paper (GE Healthcare, IL, United States) saturated with deionized H2O. The equilibration process was conducted over 48 hours at 37 °C to ensure complete isotopic saturation. Radioactivity accumulated in the filter paper was subsequently quantified via liquid scintillation spectroscopy (Tri-Carb; PerkinElmer, CT, United States), and the resultant values were normalized to total cellular DNA content to account for variations in cell number between experimental conditions[22].

Glucose oxidation assessment: Glucose oxidation was assessed by incubating cells for 5 hours in complete growth medium supplemented with 0.55 μCi/mL [6-14C]-D-glucose (PerkinElmer, CT, United States). Cellular metabolism was subsequently terminated by the addition of 250 μL of 2 M perchloric acid solution (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States). The wells were immediately sealed with Whatman filter paper (GE Healthcare, IL, United States) pre-saturated with 1 × hyamine hydroxide (Millipore Sigma, Germany) to capture the evolved 14CO2. Following overnight absorption at ambient temperature (22-24 °C), the radioactivity trapped in the filter paper was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, IN, United States). The resultant values were normalized to cellular DNA content to account for variations in cell number between experimental conditions.

Oxygen consumption assessment: Cellular oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was quantitatively determined utilizing an XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience Europe, Denmark). Cells were precisely seeded onto Seahorse XF24 tissue culture microplates at optimal density. Measurements were conducted in unbuffered DMEM (Gibco, MA, United States) supplemented with 5 mmol/L D-glucose and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, with pH adjusted to 7.4. The OCR assessment protocol consisted of sequential measurement cycles, each comprising a 2-minute mixing phase, a 2-minute recovery period, and a 6-minute measurement interval, continued over a 3-hour experimental duration. To account for potential variations in cell density between wells, all obtained OCR values were normalized to total DNA content per well, providing standardized metabolic measurements across experimental conditions[23].

Fatty acid oxidation assessment: Palmitate β-oxidation capacity was assessed by incubating cells with 2 μCi/mL [9,10-3H]-palmitic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, MO, United States) for 2 hours under standard culture conditions. Following the incubation period, the culture medium was carefully transferred into specialized glass vials equipped with rubber septum caps (Wheaton, NJ, United States). 3H2O, produced as a direct metabolic product of palmitate oxidation, was captured in hanging wells containing Whatman filter paper (GE Healthcare, IL, United States) saturated with deionized H2O during a 48-hour equilibration period at 37 °C in a temperature-controlled environment. The radioactivity trapped in the filter paper was subsequently quantified using a liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard Instrument, IL, United States). To standardize results across experimental conditions, all values were normalized to cellular DNA content, providing a precise measure of fatty acid oxidation capacity per unit of cellular material.

Glucose uptake, and glucose, lactate, and glutamine consumption assessment: Cellular glucose uptake was evaluated using the fluorescent D-glucose analogue 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States). Cells were incubated with 50 μmol/L 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxy-D-glucose for 2 hours under standard culture conditions, followed by thorough washing with PBS (Gibco, MA, United States) to remove extracellular fluorescent probe. Fluorescence intensity was subsequently quantified via flow cytometric analysis using a Gallios™ Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, IN, United States). Mean fluorescence intensity, representing cellular glucose uptake capacity, was calculated using Kaluza™ analytical software (Beckman Coulter, IN, United States). For extracellular metabolite quantification, glucose, lactate, and glutamine concentrations in conditioned medium were precisely determined using commercially available Glucose Assay kit, Lactate Assay kit, and Glutamine Colorimetric Assay kit (BioVision, CA, United States), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. All metabolic parameters were normalized to cellular DNA content to account for variations in cell number between experimental conditions, ensuring standardized metabolic measurements[24].

Energy level assessment: For the assessment of cellular energy status, cells were harvested and extracted in ice-cold 0.4 M perchloric acid containing 0.5 mmol/L EDTA. Nucleotide levels (ATP, ADP, and AMP) were quantified via ion-pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. The cellular energy status was evaluated by calculating the ATP:AMP ratio. Complementary analysis of intracellular ATP concentrations was performed using the ATPlite lumi

GSH level assessment: Cellular GSH content was evaluated through a rigorous extraction protocol in which cells were homogenized directly into freshly prepared 5-sulfosalicylic acid solution (5% w/v) to prevent oxidation artifacts. Following centrifugation at 10000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C, the supernatant was carefully collected for the quantitative determination of reduced GSH, GSH disulfide (GSSG), and total GSH levels using the Glutathione Fluorometric Assay Kit (BioVision Inc., CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Spectrofluorometric measurements were performed using a microplate reader with excitation/emission wavelengths of 340/420 nm, respectively. All GSH measurements were normalized to total protein content as determined by the Bradford assay to ensure accurate cross-sample comparisons and account for variations in cellular density.

Reactive oxygen species level assessment: Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were detected by the use of a fluorescent probe dye, CM-H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States). Briefly, periosteal cells were incubated with 10 μmol/L CM-H2DCFDA for 30 minutes at 37 °C, and fluorescence was detected by flow cyto

Glycogen content assessment: Intracellular glycogen concentrations were quantitatively assessed utilizing the Glycogen Assay Kit (BioVision Inc., CA, United States). In brief, cells were homogenized in 200 μL of ultrapure water on ice, followed by thermal denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes to inactivate endogenous enzymes. The homogenates were subsequently centrifuged at 13000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were subjected to enzymatic analysis according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All measurements were normalized to total protein content to ensure standardization across experimental conditions.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry GSH analysis: Samples were subjected to extraction using 150 μL of 5% trichloroacetic acid, followed by centrifugation at 20000 × g for 10 minutes to precipitate proteins. The resulting supernatant was carefully transferred to analytical vials, and 80 μL aliquots were chromatographically separated on an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, particle size 1.8 μm; Waters Corporation, MA, United States) main

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of glycolytic and tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates: Cells were cultured for 24 hours in glucose- and glutamine-free culture medium (Gibco, MA, United States) supplemented with dialyzed FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States) and appropriate isotopic tracers. [U-13C]-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States) and [U-13C]-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, MA, United States) were employed as metabolic precursors to facilitate downstream flux analysis through mass spectrometric determination of isotopomer distributions in cellular metabolites. Samples were extracted and analyzed as follows.

Cellular metabolites were harvested using a rapid quenching procedure in liquid nitrogen, followed by extraction with a cold two-phase methanol-water-chloroform system. Phase separation was achieved by centrifugation at 4 °C, and the methanol-water phase containing polar metabolites was isolated, evaporated to dryness using a vacuum concentrator (Eppendorf, Germany), and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Prior to instrumental analysis, polar metabolites underwent a two-step derivatization process: First with 7.5 μL of methoxyamine hydrochloride (20 mg/mL in pyridine; Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States) for 90 minutes at 37 °C, followed by silylation with 15 μL of N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-N-methyl-trifluoroacetamide containing 1% tert-butyldimethylchlorosilane (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States) for 60 minutes at 60 °C. Isotopomer distributions and metabolite abundances were determined using a 7890A gas chromatography system coupled to a 5975C Inert mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies, CA, United States). Chromatographic separation was performed on a DB35MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm film thickness; Agilent Technologies, CA, United States). One microliter of derivatized sample was introduced via splitless injection at an inlet temperature of 270 °C. Helium served as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/minute. The gas chromatography oven temperature was programmed as follows: Initial hold at 100 °C for 3 minutes, followed by a temperature ramp of

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction: Cultured ADSCs were subjected to fixation with 1% formaldehyde, followed by washing and harvesting via centrifugation. The resultant cell pellet underwent resuspension in RIPA lysis buffer (composition: 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH = 8, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Triton-X100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% SDS, supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail; Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States), homogenization, incubation on ice for 10 minutes, and subsequent sonication for chromatin shearing. Post-centrifugation, an aliquot (1/30) of the supernatant containing sheared chromatin was reserved as “input” control, while the remaining fraction was immunoprecipitated with anti-ARNT/HIF-1β monoclonal antibody (NB100-124, Novus Biologicals, CO, United States) at a 1:300 dilution at 4 °C overnight. Immune complexes were captured using Pierce Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (Life Technologies, CA, United States), followed by enzymatic digestion of RNA and protein contaminants. DNA purification was performed utilizing Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, IN, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative analysis was conducted via reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) employing SYBR® GreenER™ qPCR SuperMix Universal (Life Technologies, CA, United States) and gene-specific primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Belgium) targeting HIF binding sites. Validation of the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) procedure incorporated positive controls amp

Acid burn wound mouse model and ADSCs treatment: Male mice were anesthetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital via intraperitoneal injection. The dorsal skin was carefully shaved and prepared for wound creation. Chemical burns were induced by applying a 15 mm diameter filter paper saturated with hydrochloric acid to the dorsal skin for precisely 12 minutes. After 24 hours of wound development, necrotic tissue was meticulously debrided under sterile conditions.

Then, a cell suspension (2 × 106 cells/wound in 1 mL) was administered via intradermal injection around the wound perimeter, with 0.25 mL delivered per quadrant to ensure uniform distribution. The mice were divided into particular groups according to different experimental designs and given differently treated ADSCs. Wound healing progression was documented photographically on days 0, 1, 4, 7, 10, and 14 post-operation under standardized lighting and posi

Tissue hematoxylin-eosin staining and analysis: Cutaneous tissue specimens from the mouse wound sites were excised and immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours at ambient temperature. Following fixation, the specimens were dehydrated in 70% ethanol for 48 hours before being embedded in paraffin blocks. Serial 5-μm-thick transverse sections were obtained from the central region of each wound. The sections were subsequently subjected to hematoxylin-eosin staining as described previously for histomorphological evaluation. Digital micrographs were captured using a BX53 microscope (Olympus, Japan) and quantitatively analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0). For each specimen, ten view fields were randomly selected and evaluated by two independent researchers.

In vivo cell survival evaluation: Mouse cutaneous tissue was fixed, processed, and sectioned as described previously. Apoptotic cells were detected via terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) immunohistochemical staining, which identifies DNA fragmentation characteristic of programmed cell death. For quantitative assessment of cell viability, we performed ex vivo AnxV-PI flow cytometry analysis. The cellular components were isolated by enzymatic digestion using collagenase-dispase (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, United States). The dissociated cells were subsequently collected by centrifugation (300 × g, 5 minutes) and stained with 1 × annexin V-allophycocyanin conjugate (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States) and 1 μg/mL PI (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

To discriminate between implanted ADSCs and in-situ cells, the host cells were pre-labeled with CellTracker CM-FDA (5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate) (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States) prior to ADSCs trans

Tissue immunofluorescence staining and analysis: To assess cellular apoptosis, TUNEL was performed utilizing the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Belgium). Hypoxic tissue regions were visualized following intraperitoneal administration of pimonidazole hydrochloride to mice, with subsequent immunohistochemical detection using the Hypoxyprobe-1 PLUS Kit (Natural Pharmacia International, MA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For evaluation of oxidative DNA damage, immunohistochemical analysis was conducted using a monoclonal antibody against 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (1:200 dilution; Abcam, United Kingdom), a well-established biomarker of oxidative stress-induced DNA modification.

In vivo cell metabolic evaluation: To evaluate the significance of in vivo metabolic adaptations during burn wound healing in mice, we used the ectopic ADSCs implantation model. Before implantation, cells were labeled with CellTracker CMRA (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, CA, United States) to distinguish them from host cells. Three days after implantation, cells were collected by enzymatic digestion (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland), and CMRA+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry (BD FACSAria III, BD Biosciences, NJ, United States). Then, cytoplasmic ROS levels, GSH redox status (GSH:GSSG ratio), and glycogen content were determined as previously described.

Statistical results were analyzed and visualized using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.1.1; GraphPad Software, CA, United States). Data were presented as means ± SEM in bar graphs. All experiments were designed with consideration of statistical power, and sample sizes were chosen based on preliminary experiments or published studies in the field to ensure reproducibility. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using two-sided, two-sample Student’s t-tests, while multi-group comparisons employed one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests. Randomization was applied to animal grouping and cell treatment assignments, and blinding was implemented during data collection and analysis to minimize observer bias. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

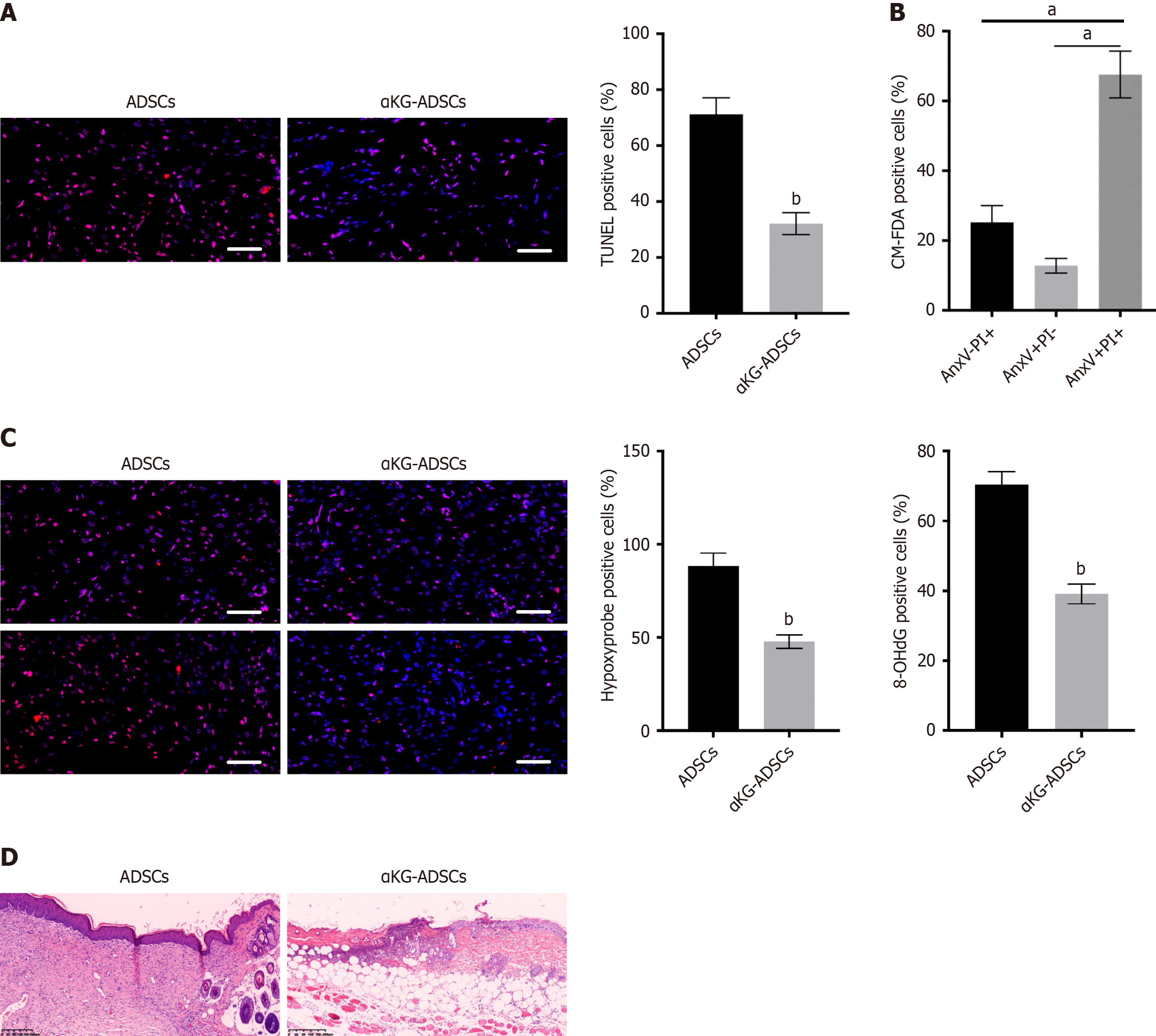

We utilized a validated burn wound model to investigate the in vivo survival rate of implanted ADSCs. Mouse ADSCs were either pre-treated with α-KG or left untreated before being transplanted into the acid burn wounds on the dorsal skin of mice. Three days post-transplantation, a substantial proportion of untreated ADSCs underwent apoptosis. This was detected via TUNEL staining of histological sections and further confirmed by AnxV-PI flow cytometry of the implanted CM-FDA-labeled cells (Figure 1A and B). Apoptotic cells were evident throughout the burn wound sites (Figure 1A). Furthermore, this cell death was associated with tissue hypoxia and ROS-mediated oxidative DNA damage, as respectively indicated by hypoxyprobe and 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine staining on histological sections (Figure 1C).

To test whether the increased survival of αKG-ADSCs improved their regenerative potential, we evaluated the wound healing process 14 days after ADSCs transplantation. Histomorphometric analysis of wound area and epithelial gap in hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections revealed that αKG-ADSCs significantly enhanced wound closure and re-epithelialization compared to the control ADSC group (Figure 1D). Furthermore, qualitative histological assessment indicated that αKG-ADSC-treated wounds exhibited better-organized granulation tissue architecture, with a less dense and more cellular stromal appearance, alongside reduced inflammatory cell infiltration. In contrast, control ADSC-treated wounds showed incomplete healing with thicker, more densely stained areas suggestive of immature or disorganized tissue deposition. These histomorphological observations are consistent with an accelerated and potentially higher-quality healing process in the αKG-ADSCs group.

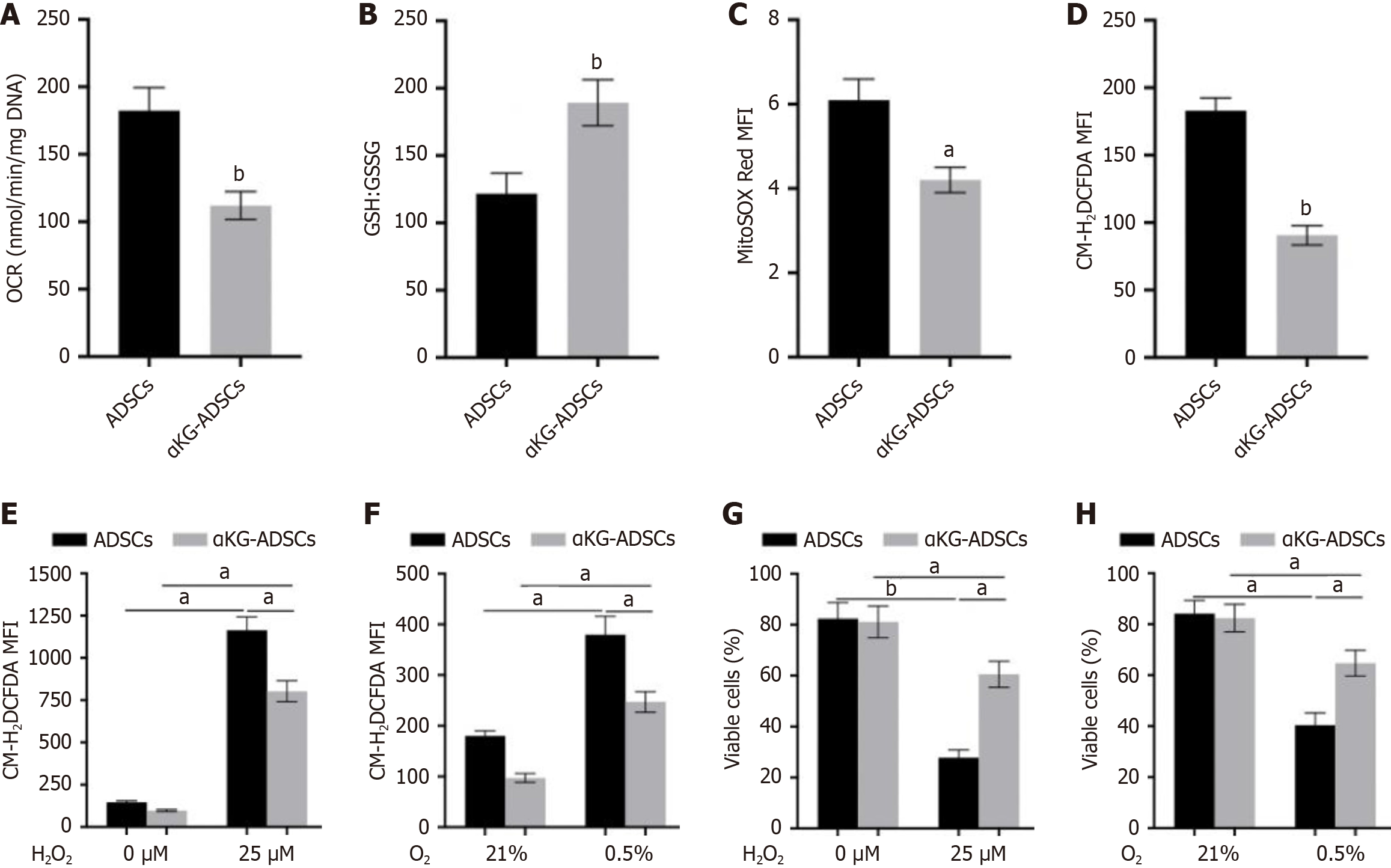

A fundamental requirement for cell survival in stress conditions like the hypoxic environment of burn wounds is the precise regulation of redox state to prevent oxidative damage. While mitochondrial respiration constitutes a primary source of ROS, cells employ an array of enzymatic and non-enzymatic scavenging mechanisms to ensure these reactive species are tightly regulated. α-KG treatment of ADSCs resulted in a reduced OCR (Figure 2A). Furthermore, αKG-ADSCs exhibited elevated total GSH levels and an increased GSH:GSSG ratio (Figure 2B). Eventually, these adaptations resulted in decreased mitochondrial and total intracellular ROS levels (Figure 2C and D). To evaluate the biological relevance of these changes, we examined the ability of αKG-ADSCs to survive during oxidative stress by adding exogenous ROS or by hypoxia exposure, which increases complex III-dependent superoxide generation. When exposed to H2O2 or cultured under 0.5% oxygen, αKG-ADSCs exhibited a markedly attenuated rise in intracellular ROS levels relative to untreated ADSCs (Figure 2E and F). Consequently, their survival rate was significantly better maintained under these stressful conditions (Figure 2G and H). Taken together, α-KG treatment enhances ROS detoxification mechanisms in ADSCs, resulting in improved cell survival under oxidative stress conditions that mimic the harsh environment of burn wounds.

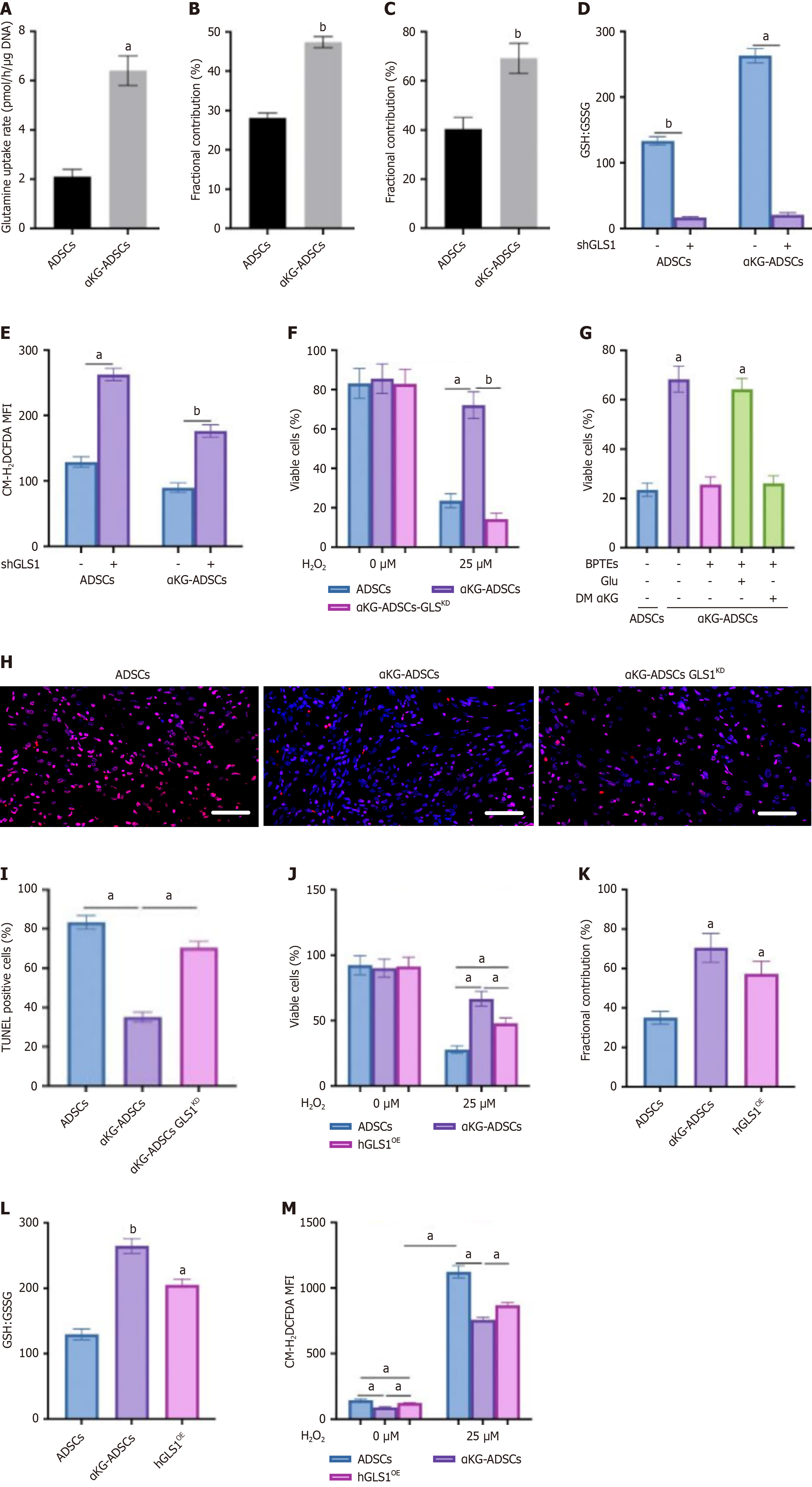

Since total GSH levels were elevated in α-KG-treated ADSCs, we questioned whether GSH synthesis was altered in these cells. Glutamine is an important precursor for GSH, after being converted into glutamate by GLS. We found that α-KG-treated ADSCs displayed a significant increase in glutamine uptake from the culture medium (Figure 3A). We next traced the metabolic conversion of glutamine using [U-13C]-glutamine to quantify its contribution to glutamate and GSH biosynthesis. This analysis showed that α-KG preconditioning significantly increased the isotopic enrichment from [U-13C]-glutamine into these metabolites compared to untreated cells, demonstrating a redirected glutamine flux (Figure 3B and C).

To determine the biological role of GLS1 in maintaining redox homeostasis in α-KG-ADSCs, we assessed the effect of genetic interference with GLS1 on GSH-mediated ROS detoxification. GLS1 knockdown (shGLS1) reduced the GSH:GSSG ratio to equally low levels in ADSCs and α-KG-ADSCs (Figure 3D), leading to elevated ROS (Figure 3E) and abolishing the cytoprotective effect of α-KG during oxidative stress (Figure 3F). Consistent with this, the GLS1 inhibitor BPTES also decreased the GSH:GSSG ratio and increased ROS. The viability loss in H2O2-exposed, BPTES-treated cells was spe

To validate the in vivo relevance of GLS1 upregulation for the prosurvival effect of α-KG, we implanted αKG-ADSCs-GLSKD cells into mouse burn wounds. Mirroring our in vitro findings, GLS1 silencing markedly increased apoptosis among the α-KG-ADSCs (Figure 3H and I). Moreover, knocking down GLS1 in untreated ADSCs further exacerbated their inherently poor survival in vivo, underscoring the critical role of glutamine metabolism in sustaining cell viability under nutrient-deprived wound conditions.

To determine if increased GLS1 expression alone is sufficient to sustain redox homeostasis and survival under stress, we engineered ADSCs to ectopically overexpress human GLS1 (hGLS1OE). These hGLS1OE cells recapitulated key phenotypes of α-KG-ADSCs, demonstrating enhanced resistance to H2O2-induced oxidative damage (Figure 3J). Further

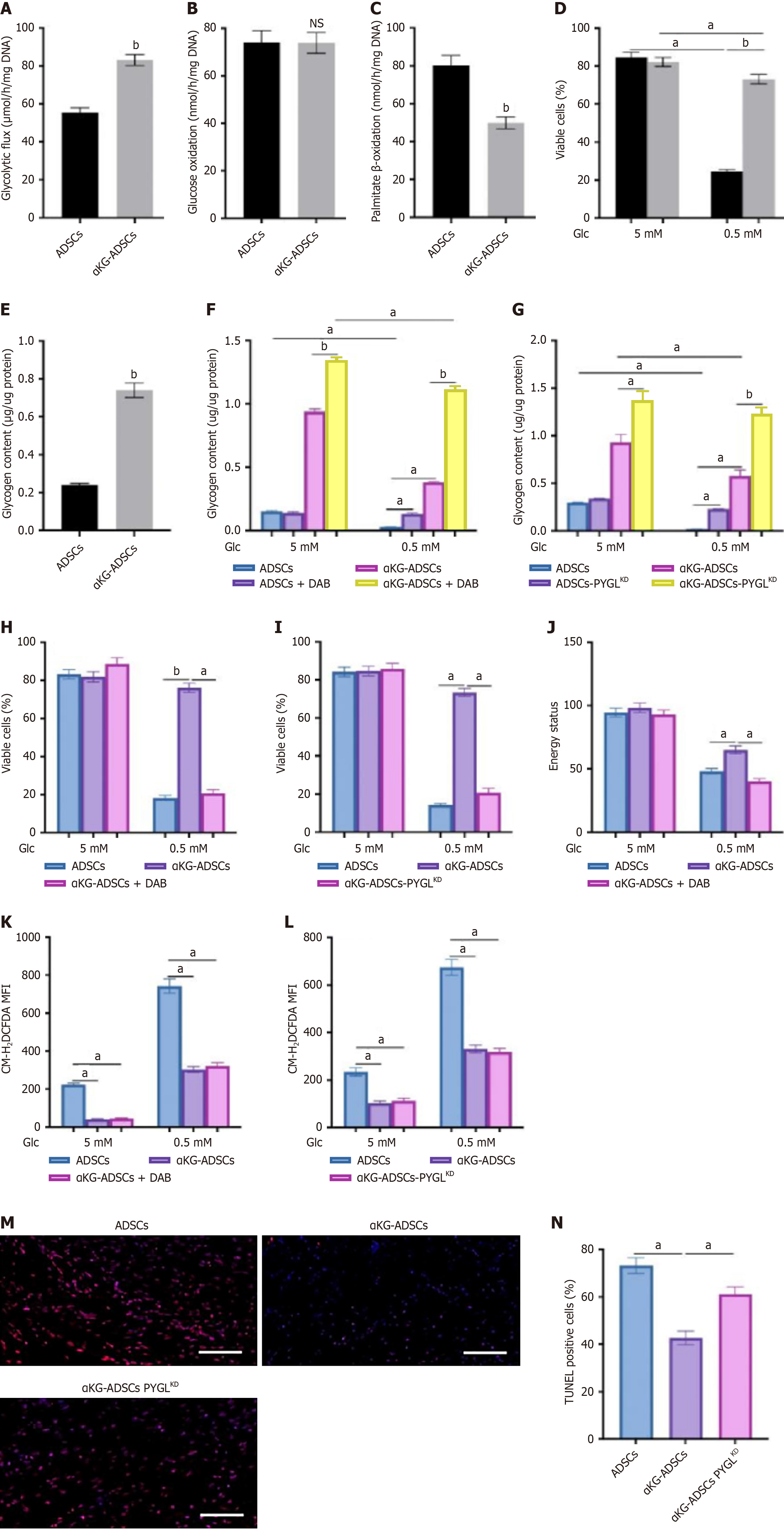

Beyond redox balance, cellular survival under stress is critically dependent on energy status, frequently necessitating metabolic reprogramming. In αKG-ADSCs, this adaptation involved enhanced glucose uptake and glycolytic flux (Figure 4A). Notably, while oxygen consumption was reduced (Figure 2A), glucose oxidation remained unchanged (Figure 4B). Instead, the diminished OCR was attributable to a decline in fatty acid oxidation, as demonstrated by suppressed palmitate β-oxidation (Figure 4C). This metabolic reprogramming may contribute to the enhanced survival of αKG-ADSCs in the hypoxic wound environment by reducing oxygen dependency while maintaining adequate energy production.

Although αKG-ADSCs exhibit decreased fatty acid oxidation (Figure 4C) and channel increased glutamine uptake toward GSH synthesis (Figure 3C), indicating a heightened reliance on glucose, they paradoxically display greater resistance to glucose deprivation (Figure 4D). This apparent paradox can be explained by an elevated conversion of glucose into intracellular glycogen, creating a reserve for rapid mobilization during nutrient stress. Direct biochemical measurement confirmed a significant accumulation of cytoplasmic glycogen in these cells (Figure 4E).

In contrast to untreated ADSCs, which exhausted their glycogen reserves completely during glucose deprivation, αKG-ADSCs mobilized a significantly greater amount of glycogen while still retaining substantial reserves (Figure 4F and G). The importance of glycogen usage was investigated by treating cells with DAB, an inhibitor of glycogen phosphorylase (PYGL), or silencing PYGL using shRNA (αKG-ADSCs-PYGLKD), which prevented glycogen breakdown (Figure 4F and G). This strategy significantly abrogated the improved viability of αKG-ADSCs during glucose deprivation (Figure 4H and I). Inhibition of PYGL using DAB even resulted in an energy deficit: The energy status, measured as the ratio of ATP to AMP levels, was better preserved in αKG-ADSCs compared to control ADSCs during glucose deprivation, but this advantage was lost upon PYGL inhibition (Figure 4J). On the other hand, compared to untreated cells, αKG-ADSCs showed a smaller increase in ROS levels during glucose deprivation, which was, however, not affected by inhibition of PYGL (Figure 4K and L). This suggests that the enhanced antioxidant capacity of αKG-ADSCs is independent of glycogen metabolism, while energy production during nutrient deprivation relies on glycogen breakdown. Consistent with this model, PYGL knockdown also compromised the survival of implanted αKG-ADSCs in vivo (Figure 4M and N), un

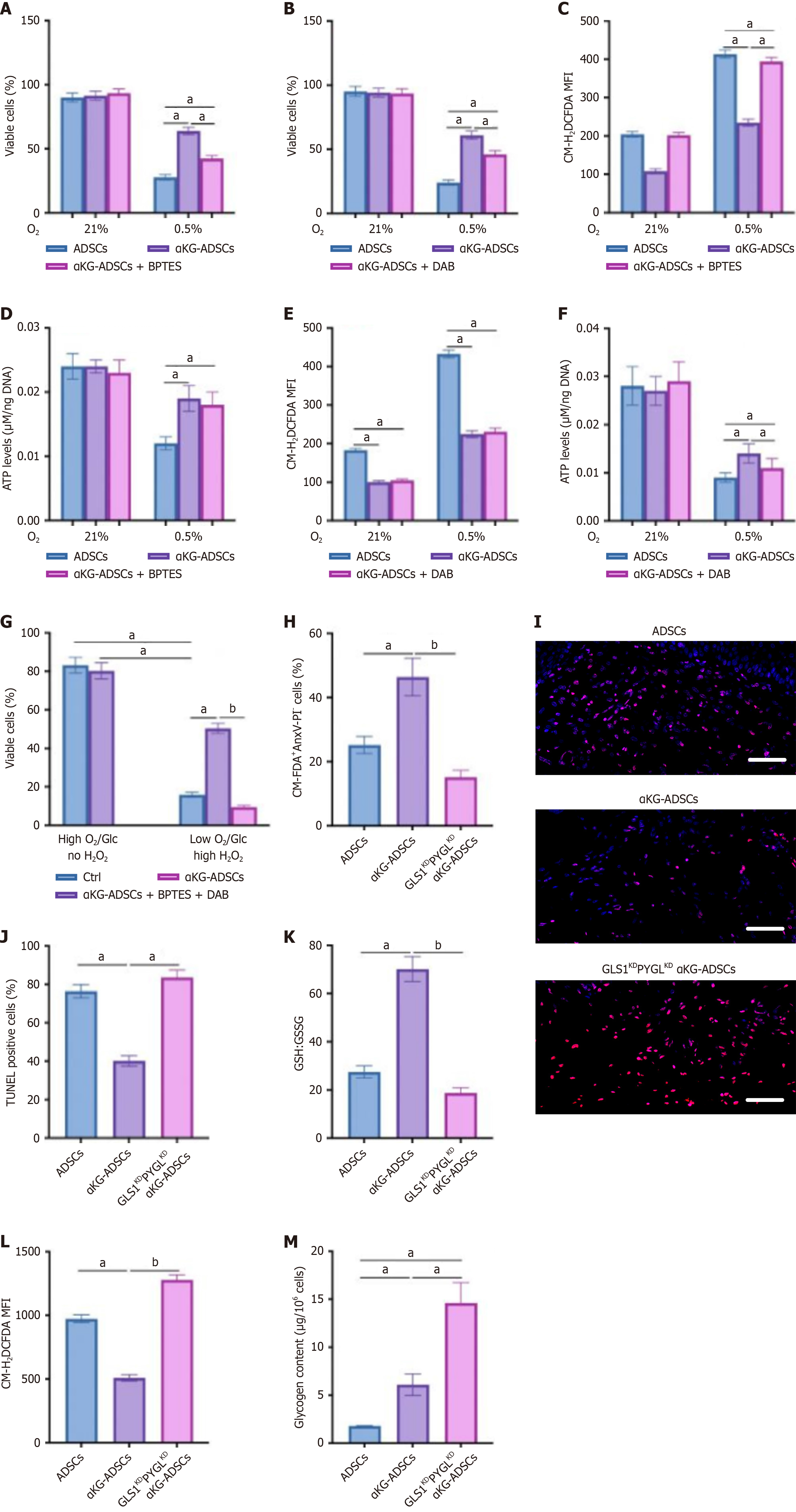

Given the enhanced hypoxic survival of αKG-ADSCs (Figure 2H), we dissected the contributions of glutamine and glycogen metabolism. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of GLS1 or PYGL partially reduced the viability of αKG-ADSCs under hypoxia, though not to the level of untreated cells (Figure 5A and B), implying both pathways are involved. Mechanistically, each pathway served a distinct purpose: Glutamine metabolism was essential for ROS suppression, whereas glycogen storage was critical for maintaining ATP levels, with no functional overlap observed (Figure 5C-F). Consequently, while GLS1 inhibition specifically compromised survival under oxidative stress and PYGL inhibition under glucose deprivation, their combined action is vital for hypoxic survival, integrating antioxidant defense with bioenergetic support.

To recapitulate the multifactorial stress of the burn wound microenvironment in vivo, we subjected cells to a combination of hypoxia, glucose deprivation, and oxidative stress in vitro. Under these conditions, concurrent pharmacological blockade of both GLS1 and PYGL with BPTES and DAB profoundly compromised αKG-ADSC survival (Figure 5G). The in vivo relevance of this metabolic synergy was validated in the burn wound model. Dual knockdown of GLS1 and PYGL in implanted αKG-ADSCs (GLS1KDPYGLKD αKG-ADSCs) induced a more severe compromise in viability than individual silencing, as measured by AnxV-PI flow cytometry and TUNEL staining (Figure 5H-J compared to earlier single knockdown results). Mechanistically, the GLS1KDPYGLKD αKG-ADSCs implanted in vivo were incapable of elevating the GSH:GSSG ratio, resulting in heightened ROS levels (Figure 5K and L), and could not metabolize glycogen to avoid energy distress (Figure 5M). The inability to maintain redox balance and energy homeostasis compromised the survival advantage conferred by α-KG treatment.

Thus, a synergistic interplay between glutamine and glycogen metabolism collectively ensures αKG-ADSC survival within the hypoxic and nutrient-deficient milieu of burn wounds. These findings demonstrate that α-KG treatment enhances HIF-1α stabilization, which orchestrates multiple metabolic adaptations to simultaneously improve redox homeostasis through glutamine metabolism and energy supply through glycogen storage, collectively contributing to enhanced ADSC survival and improved wound healing capacity.

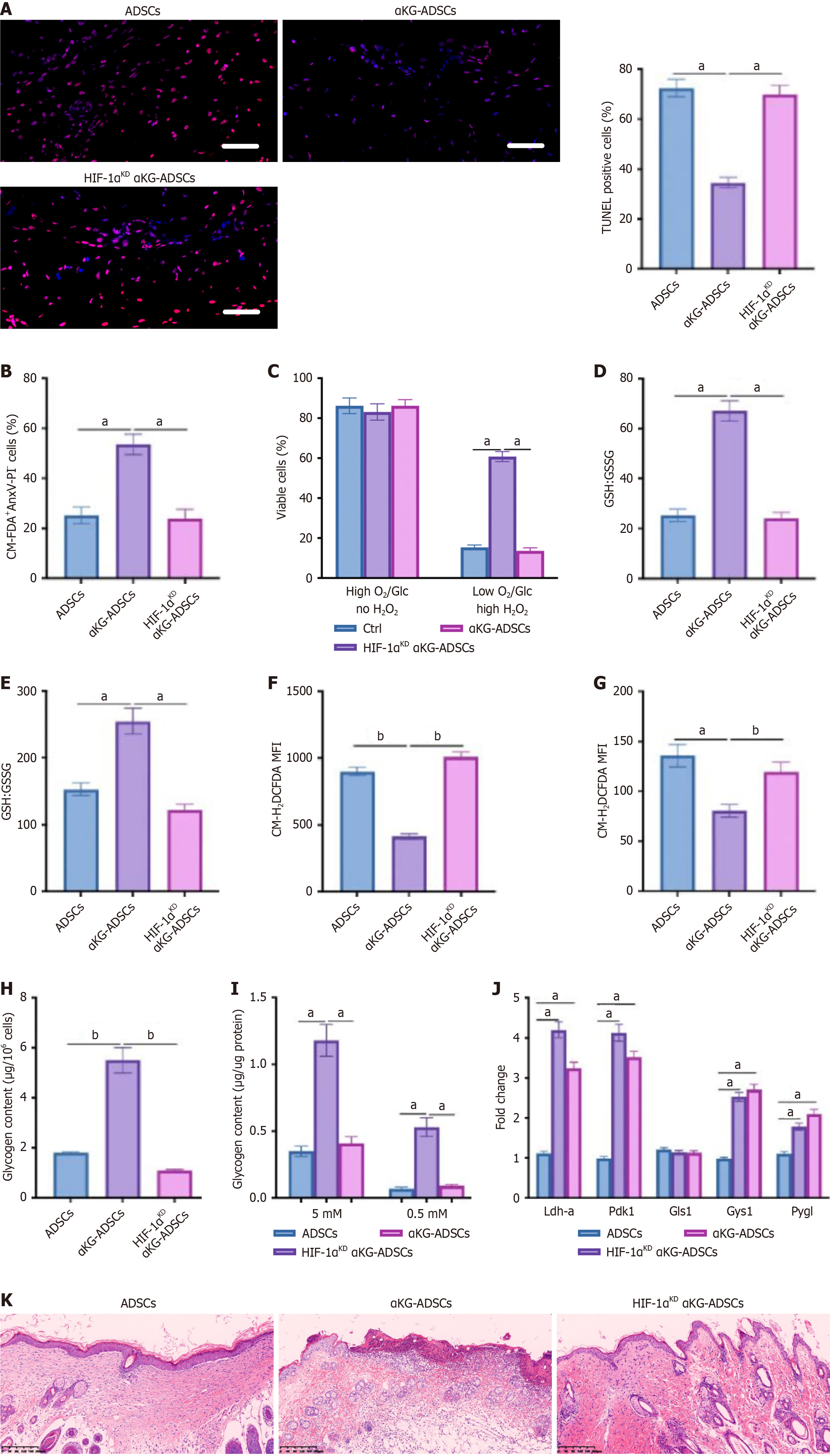

To investigate whether HIF-1α mediates the beneficial effects of α-KG treatment on ADSC survival and function, we silenced HIF-1α in αKG-ADSCs (HIF-1αKD αKG-ADSCs). Genetic knockdown of HIF-1α abolished the survival advantage of αKG-ADSCs in the burn wound model, reverting their viability to the baseline level of control cells. This was con

To determine the direct transcriptional targets of HIF-1α in αKG-ADSCs, we performed HIF-1β ChIP followed by qPCR on key metabolic genes. The analysis revealed significant HIF-1β enrichment at promoters of established HIF-1α targets

In this study, we demonstrate that α-KG pretreatment significantly enhances the survival of implanted ADSCs in burn wounds, resulting in improved wound healing outcomes. This enhanced survival is achieved through comprehensive metabolic reprogramming that enables ADSCs to withstand the harsh microenvironment of burn wounds characterized by hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and oxidative stress. We believe that the metabolic adaptations orchestrated by HIF-1α stabilization provide α-KG-treated ADSCs with dual protective mechanisms: Enhanced ROS detoxification through glutamine metabolism and improved energy reserves through glycogen storage.

Our findings establish HIF-1α as the central regulator orchestrating the metabolic reprogramming in α-KG-preconditioned ADSCs. A key question arising from our study is the precise molecular mechanism by which α-KG leads to HIF-1α stabilization. While our data clearly demonstrate the functional outcome of HIF-1α activation, the initial triggering event warrants further discussion. It is well-established that the stability of HIF-1α is primarily controlled by a family of prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing proteins (PHDs), which use α-KG as an essential co-substrate for the oxygen-dependent hydroxylation that targets HIF-1α for proteasomal degradation[27,28]. This creates a seemingly paradoxical situation where an intermediate of the TCA cycle could potentially regulate its own enzymatic reaction.

However, previous research provides a plausible explanation for our observations. Several studies have shown that certain cell-permeable α-KG analogs, such as dimethyl-2-ketoglutarate, can act as competitive inhibitors of PHDs, thereby stabilizing HIF-1α[27,28]. The mechanism is thought to involve the alteration of the intracellular α-KG/succinate ratio or the direct competition with endogenous α-KG for the enzyme’s active site, effectively mimicking a hypoxic state even under normoxia. We postulate that a similar mechanism is at play in our model, where the supplementation of DM-αKG leads to the competitive inhibition of PHD2, the primary HIF-1α regulatory hydroxylase, resulting in HIF-1α accumulation. This is further supported by our observation of HIF-1α upregulation under normal culture conditions following α-KG pretreatment.

That said, we cannot rule out the contribution of other, more indirect, metabolic pathways. The increase in intracellular α-KG could influence the NAD+/NADH ratio, mitochondrial ROS signaling, or the activity of other α-KG-dependent dioxygenases, all of which have been implicated in modulating HIF-1α stability through non-canonical pathways. The indirect regulation of Gls1 expression by HIF-1α, as suggested by our ChIP followed by qPCR data, also hints at a more complex regulatory network that may involve feedback loops or intermediary transcription factors.

Therefore, while our data strongly support the role of HIF-1α stabilization as a critical event, the detailed molecular initiation - specifically the direct interaction between supplemented α-KG and PHDs, and the potential crosstalk with other metabolic regulators - remains an exciting area for future investigation. Subsequent studies should employ techniques such as in vitro PHD activity assays, measurement of intracellular α-KG/succinate ratios, and the use of specific PHD inhibitors or mutants to dissect this precise initiating step.

A key finding of our study is that α-KG-treated ADSCs exhibit enhanced glutamine metabolism specifically directed toward GSH synthesis rather than TCA cycle anaplerosis. This metabolic adaptation significantly improves cellular redox balance, allowing α-KG-ADSCs to withstand oxidative stress in burn wounds better. The increased glutamine uptake and its conversion to GSH through GLS1 activity were essential for maintaining low ROS levels and promoting cell survival. This pattern of glutamine utilization differs from what is typically observed in cancer cells, where glutamine primarily serves anaplerotic functions in the TCA cycle and supports reductive carboxylation for biosynthesis[29,30]. In α-KG-ADSCs, glutamine was predominantly channeled toward GSH synthesis for ROS detoxification, highlighting the context-specific nature of metabolic adaptations. The critical role of this pathway was demonstrated by the complete loss of the prosurvival effect when GLS1 was inhibited, and the rescue of cell viability by glutamate supplementation, which bypassed the need for GLS1 activity.

Our results demonstrated that α-KG pretreatment significantly increases glycogen storage in ADSCs, providing them with a crucial energy reserve during nutrient deprivation in the wound environment. This finding aligns with obser

The importance of glycogen metabolism was confirmed by the inhibition of PYGL, which prevented glycogen bre

A novel aspect of our study is that we demonstrated the necessity of combined adaptations in glutamine and glycogen metabolism for optimal survival of ADSCs under the multiple stressors present in burn wounds. While each pathway addressed specific aspects of cellular stress - glutamine metabolism for redox balance and glycogen metabolism for energy supply - their combined action was required for maximal protection against the complex stress conditions in vivo[35,36]. This was particularly evident when cells were exposed to combined stressors (hypoxia, glucose deprivation, and oxidative stress) that mimic the burn wound environment. Under these conditions, simultaneous inhibition of GLS1 and PYGL completely abolished the survival advantage of α-KG-ADSCs, while individual pathway inhibition had partial effects.

The enhanced survival of α-KG-treated ADSCs translated into significantly improved wound healing outcomes, cha

The detailed mechanism by which α-KG stabilizes HIF-1α in ADSCs likely involves inhibition of PHDs, as suggested by previous studies showing that dimethyl-2-ketoglutarate can inhibit PHD2 activity[27,28]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which α-KG regulates HIF-1α stability and the indirect regulation of GLS1 expression still need further investigation. Future studies should also focus on optimizing the α-KG pretreatment protocol, investigating the long-term effects of metabolically reprogrammed ADSCs on wound healing outcomes, and exploring the potential of combining α-KG pretreatment with other approaches to further enhance cell survival and regenerative capacity.

Taken together, our study establishes α-KG pretreatment as an effective strategy to enhance ADSC survival and function in burn wounds through HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming. The dual protective mechanisms of enhanced ROS detoxification through glutamine metabolism and improved energy reserves through glycogen storage provide α-KG-treated ADSCs with comprehensive stress resistance capabilities. These findings have significant implications for enhancing cell-based therapies not only for burn wounds but also potentially for other ischemic and hypoxic tissue injuries where cell survival remains a major challenge. By enhancing the metabolic fitness of therapeutic cells prior to implantation, we can significantly improve the efficacy of regenerative medicine approaches across various clinical applications.

While our study provides compelling evidence for the efficacy of α-KG preconditioning in enhancing ADSC survival and wound healing, we acknowledge that it is primarily based on a single murine model (BALB/c mice). This focus was instrumental in allowing a deep, mechanistic investigation into the role of HIF-1α and associated metabolic pathways. However, we recognize that the generalizability of our findings to other physiological or pathological contexts requires further validation. Future studies are warranted to confirm the therapeutic potential of α-KG preconditioning in other animal models, such as diabetic or aged mice, which exhibit impaired wound healing and represent more clinically challenging scenarios. Furthermore, extending this investigation to human-derived ADSCs in advanced humanized mouse models or in 3D skin-equivalent cultures would be a critical step toward clinical translation. Such studies would help to verify whether the HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming observed in our model is conserved in human cells and remains effective in a more complex, human-like microenvironment. We believe that the mechanistic insights gained here, specifically the dual enhancement of redox homeostasis and energy reserves, provide a strong rationale for its broader applicability. Confirming this in diverse models will be a key objective of our subsequent research.

Besides, the long-term efficacy and safety profile of α-KG-preconditioned ADSCs, a crucial aspect for clinical tran

The compelling efficacy of α-KG preconditioning in our study naturally prompts consideration of its clinical translation for stem cell-based wound therapies. Several practical aspects require systematic investigation to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and clinical application. First, determining the optimal dosing and timing of α-KG preconditioning is paramount. Future work should establish a detailed dose-response relationship and identify the minimal effective con

Our study demonstrates that α-KG pretreatment enhances the survival and regenerative capacity of ADSCs in burn wounds through HIF-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming. This approach simultaneously enhances ROS detoxification through glutamine metabolism and improves energy reserves via glycogen storage, enabling ADSCs to withstand the hypoxic, nutrient-deprived, and oxidative stress conditions characteristic of burn wounds. The enhanced survival of α-KG-treated ADSCs results in accelerated wound closure and improved tissue regeneration. This metabolic preconditioning strategy presents a promising solution to the challenge of poor cell survival in regenerative medicine applications, establishing α-KG as a valuable tool for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of stem cell treatments for burn wounds and potentially other ischemic tissues.

| 1. | Ma T, Fu B, Yang X, Xiao Y, Pan M. Adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote cell proliferation, migration, and inhibit cell apoptosis via Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:10847-10854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li P, Guo X. A review: therapeutic potential of adipose-derived stem cells in cutaneous wound healing and regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Ding H, Bai R, Li Q, Ren B, Lin P, Li C, Chen M, Xu X. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells accelerate wound healing by increasing the release of IL-33 from macrophages. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shimizu Y, Ntege EH, Takahara E, Matsuura N, Matsuura R, Kamizato K, Inoue Y, Sowa Y, Sunami H. Adipose-derived stem cell therapy for spinal cord injuries: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Regen Ther. 2024;26:508-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aggarwal P, Oza RR, Solanki H, Charan J, Kaur RJ, Deora S, Saini L, Kumar D, Choudhary R, Bhardwaj P, Kanchan T, Dutta S. Efficacy & safety of stem cell therapy for treatment of acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Indian J Med Res. 2025;161:647-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Karam JP, Muscari C, Montero-Menei CN. Combining adult stem cells and polymeric devices for tissue engineering in infarcted myocardium. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5683-5695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aguado BA, Mulyasasmita W, Su J, Lampe KJ, Heilshorn SC. Improving viability of stem cells during syringe needle flow through the design of hydrogel cell carriers. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:806-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kang Y, Kim S, Fahrenholtz M, Khademhosseini A, Yang Y. Osteogenic and angiogenic potentials of monocultured and co-cultured human-bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and human-umbilical-vein endothelial cells on three-dimensional porous beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffold. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:4906-4915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Robey TE, Saiget MK, Reinecke H, Murry CE. Systems approaches to preventing transplanted cell death in cardiac repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:567-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lovett M, Lee K, Edwards A, Kaplan DL. Vascularization strategies for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2009;15:353-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 673] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hu C, Li L. Preconditioning influences mesenchymal stem cell properties in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:1428-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Noronha NC, Mizukami A, Caliári-Oliveira C, Cominal JG, Rocha JLM, Covas DT, Swiech K, Malmegrim KCR. Priming approaches to improve the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 429] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vettore L, Westbrook RL, Tennant DA. New aspects of amino acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:150-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vander Heiden MG, DeBerardinis RJ. Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology. Cell. 2017;168:657-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1112] [Cited by in RCA: 1663] [Article Influence: 184.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Eales KL, Hollinshead KE, Tennant DA. Hypoxia and metabolic adaptation of cancer cells. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nagao A, Kobayashi M, Koyasu S, Chow CCT, Harada H. HIF-1-Dependent Reprogramming of Glucose Metabolic Pathway of Cancer Cells and Its Therapeutic Significance. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee P, Chandel NS, Simon MC. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factors and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:268-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 887] [Article Influence: 147.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 18. | Li S, Zhao C, Shang G, Xie JL, Cui L, Zhang Q, Huang J. α-ketoglutarate preconditioning extends the survival of engrafted adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells to accelerate healing of burn wounds. Exp Cell Res. 2024;439:114095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang D, Li T, Li X, Zhang L, Sun L, He X, Zhong X, Jia D, Song L, Semenza GL, Gao P, Zhang H. HIF-1-mediated suppression of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and fatty acid oxidation is critical for cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1930-1942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rieger AM, Nelson KL, Konowalchuk JD, Barreda DR. Modified annexin V/propidium iodide apoptosis assay for accurate assessment of cell death. J Vis Exp. 2011;2597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Frezza C, Zheng L, Folger O, Rajagopalan KN, MacKenzie ED, Jerby L, Micaroni M, Chaneton B, Adam J, Hedley A, Kalna G, Tomlinson IP, Pollard PJ, Watson DG, Deberardinis RJ, Shlomi T, Ruppin E, Gottlieb E. Haem oxygenase is synthetically lethal with the tumour suppressor fumarate hydratase. Nature. 2011;477:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wu M, Neilson A, Swift AL, Moran R, Tamagnine J, Parslow D, Armistead S, Lemire K, Orrell J, Teich J, Chomicz S, Ferrick DA. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C125-C136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 686] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zou C, Wang Y, Shen Z. 2-NBDG as a fluorescent indicator for direct glucose uptake measurement. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2005;64:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Crouch SP, Kozlowski R, Slater KJ, Fletcher J. The use of ATP bioluminescence as a measure of cell proliferation and cytotoxicity. J Immunol Methods. 1993;160:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 673] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kalyanaraman B, Darley-Usmar V, Davies KJ, Dennery PA, Forman HJ, Grisham MB, Mann GE, Moore K, Roberts LJ 2nd, Ischiropoulos H. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1346] [Cited by in RCA: 1373] [Article Influence: 98.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Buescher JM, Antoniewicz MR, Boros LG, Burgess SC, Brunengraber H, Clish CB, DeBerardinis RJ, Feron O, Frezza C, Ghesquiere B, Gottlieb E, Hiller K, Jones RG, Kamphorst JJ, Kibbey RG, Kimmelman AC, Locasale JW, Lunt SY, Maddocks OD, Malloy C, Metallo CM, Meuillet EJ, Munger J, Nöh K, Rabinowitz JD, Ralser M, Sauer U, Stephanopoulos G, St-Pierre J, Tennant DA, Wittmann C, Vander Heiden MG, Vazquez A, Vousden K, Young JD, Zamboni N, Fendt SM. A roadmap for interpreting (13)C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;34:189-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hou P, Kuo CY, Cheng CT, Liou JP, Ann DK, Chen Q. Intermediary metabolite precursor dimethyl-2-ketoglutarate stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1α by inhibiting prolyl-4-hydroxylase PHD2. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koivunen P, Hirsilä M, Remes AM, Hassinen IE, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases by citric acid cycle intermediates: possible links between cell metabolism and stabilization of HIF. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4524-4532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fendt SM, Bell EL, Keibler MA, Olenchock BA, Mayers JR, Wasylenko TM, Vokes NI, Guarente L, Vander Heiden MG, Stephanopoulos G. Reductive glutamine metabolism is a function of the α-ketoglutarate to citrate ratio in cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang L, Venneti S, Nagrath D. Glutaminolysis: A Hallmark of Cancer Metabolism. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2017;19:163-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 720] [Cited by in RCA: 659] [Article Influence: 73.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Favaro E, Bensaad K, Chong MG, Tennant DA, Ferguson DJ, Snell C, Steers G, Turley H, Li JL, Günther UL, Buffa FM, McIntyre A, Harris AL. Glucose utilization via glycogen phosphorylase sustains proliferation and prevents premature senescence in cancer cells. Cell Metab. 2012;16:751-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pescador N, Villar D, Cifuentes D, Garcia-Rocha M, Ortiz-Barahona A, Vazquez S, Ordoñez A, Cuevas Y, Saez-Morales D, Garcia-Bermejo ML, Landazuri MO, Guinovart J, del Peso L. Hypoxia promotes glycogen accumulation through hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-mediated induction of glycogen synthase 1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hamanaka RB, Chandel NS. Cell biology. Warburg effect and redox balance. Science. 2011;334:1219-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Vazquez A, Kamphorst JJ, Markert EK, Schug ZT, Tardito S, Gottlieb E. Cancer metabolism at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:3367-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zois CE, Harris AL. Glycogen metabolism has a key role in the cancer microenvironment and provides new targets for cancer therapy. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94:137-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Altman BJ, Stine ZE, Dang CV. From Krebs to clinic: glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:619-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1308] [Cited by in RCA: 1427] [Article Influence: 142.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Peng Y, Huang S, Wu Y, Cheng B, Nie X, Liu H, Ma K, Zhou J, Gao D, Feng C, Yang S, Fu X. Platelet rich plasma clot releasate preconditioning induced PI3K/AKT/NFκB signaling enhances survival and regenerative function of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in hostile microenvironments. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:3236-3251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Choi JK, Chung H, Oh SJ, Kim JW, Kim SH. Functionally enhanced cell spheroids for stem cell therapy: Role of TIMP1 in the survival and therapeutic effectiveness of stem cell spheroids. Acta Biomater. 2023;166:454-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Nie C, Yang D, Xu J, Si Z, Jin X, Zhang J. Locally administered adipose-derived stem cells accelerate wound healing through differentiation and vasculogenesis. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/