Published online May 26, 2024. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v16.i5.512

Revised: January 29, 2024

Accepted: April 1, 2024

Published online: May 26, 2024

Processing time: 162 Days and 23.2 Hours

Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology is a valuable tool for generating patient-specific stem cells, facilitating disease modeling, and investigating disease mechanisms. However, iPSCs carrying specific mutations may limit their clinical applications due to certain inherent characteristics.

To investigate the impact of MERTK mutations on hiPSCs and determine whether hiPSC-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) influence anomalous cell junction and differentiation potential.

We employed a non-integrating reprogramming technique to generate peripheral blood-derived hiPSCs with and hiPSCs without a MERTK mutation. Chromo

The generated hiPSCs, both with and without a MERTK mutation, exhibited normal karyotype and expressed pluripotency markers; however, hiPSCs with a MERTK mutation demonstrated anomalous adhesion capability and differentiation potential, as confirmed by transcriptomic and proteomic profiling. Furthermore, hiPSC-derived EVs were involved in various biological processes, including cell junction and differentiation.

HiPSCs with a MERTK mutation displayed altered junction characteristics and aberrant differentiation potential. Furthermore, hiPSC-derived EVs played a regulatory role in various biological processes, including cell junction and differentiation.

Core Tip: Patient-specific human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology is a valuable tool for disease modeling and the investigation of disease mechanisms, but altered biological properties caused by pathogenic genes may limit hiPSC applications. Through transcriptomics and proteomics, this study revealed cell junction abnormalities and aberrant cellular differentiation potential in hiPSCs with a MERTK mutation. Furthermore, the profiles of hiPSC-derived extracellular vesicles collected for transcriptomic and proteomic analysis indicated their involvement in the changes of biological characteristics occurring in hiPSCs.

- Citation: Zhang H, Wu LZ, Liu ZY, Jin ZB. Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells with a MERTK mutation exhibit cell junction abnormalities and aberrant cellular differentiation potential. World J Stem Cells 2024; 16(5): 512-524

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v16/i5/512.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v16.i5.512

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are a type of stem cells that are generated from adult somatic cells, typically peripheral blood or fibroblasts, through different reprogramming processes. iPSCs possess similar potential for division and differentiation as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and can be induced to differentiate into various cell types, tissues, and even organs[1,2]. The groundbreaking research on human iPSCs that has significant implications in the fields of regenerative medicine and stem cell research was first demonstrated by Takahashi et al[3] in 2007. Since then, numerous research teams have aimed to develop iPSC-derived products for the treatment of various diseases, with some already undergoing clinical trials[4]. Currently, there are high expectations for multiple applications of iPSCs, although there remain many challenges to overcome.

Autologous iPSC-based therapy offers several advantages, such as personalized drug discovery via patient-derived iPSC models that share the same genetic characteristics as the patient, thereby avoiding the need for immunosuppressants and reducing transplantation-related immune risks. Biologically, patient-specific iPSCs are derived from the patient’s own cells, thereby avoiding ethical controversies and legal constraints[5]. However, for patients with specific gene mutations, iPSCs derived from somatic cell reprogramming usually carry the same gene mutations[6]. Although these iPSCs or ESCs with mutations may appear to be similar to healthy controls, with unlimited proliferative potential, they may differ in various aspects, such as cell apoptosis, metabolism, proliferation, and directed differentiation potential, compared to healthy PSCs[7,8].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are tiny membrane-wrapped structures that are released by cells into the extracellular environment[9]. EVs contain various molecules, including nucleic acids, proteins, and metabolites, which allow them to function in signal transduction and cell-cell communication[10-12]. Recipient cells can take up the EVs that donor cells have released to achieve intracellular signal transmission and self-regulation[13]. Autocrine EVs can carry information required for cell signaling pathway activation or cell self-regulation, which contributes to the cell’s adjustment of its intrinsic state and functionality as it adapts to different environmental and physiological demands. Furthermore, EVs can be released by neighboring cells and taken up by nearby target cells, thereby enabling intercellular signal transduction. Paracrine EVs play a crucial role in regulating cellular differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, immune response, cellular migration, and tissue repair[10,13].

Although mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been studied extensively in the context of EVs, the composition and functions of iPSC-derived EVs remain largely unknown[14,15]. In this study, we proposed that iPSCs with specific gene mutations will exhibit differences in their transcription and protein levels, as well as their ability to regulate their own and neighboring cells’ proliferation and differentiation capacities through the secretion of EVs. Investigating iPSCs and their secreted EVs is crucial for achieving a comprehensive understanding and effective utilization of iPSCs.

Mutations in the MERTK gene, which is responsible for encoding a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in cellular signal transduction, particularly in immune regulation, apoptotic debris clearance, cell survival, proliferation, and migration, have become a particular focus of interest[16-18]. Although MERTK receptors are typically expressed in immune cells[19], our observations during cultivation revealed that iPSCs carrying MERTK gene mutations exhibited altered cell junctions compared to the control iPSCs. Furthermore, they exhibited lower efficiency in directed cellular differentiation induced by small molecular compounds compared to that of the control iPSCs.

A recent study also reported altered bioenergetics and aberrant differentiation potential occurring in patient-specific iPSCs carrying mitochondrial mutations[8]. Similar to MSC-derived EVs, iPSC-derived EVs contain abundant com

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in 6 mL peripheral blood were collected from healthy donors or patients who provided written informed consent, with approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. PBMCs were cultured in StemSpan™ Serum-Free Expansion Medium II supplemented with StemSpanTM Erythroid Expansion Supplement (STEMCELL Technologies) for 7 d to expand the erythroid cells. A total of 1 × 106 erythroid progenitors were nucleofected with episomal plasmids encoding reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Myc, Nanog, Lin28, and Klf4[20]. Nucleofection was executed using the Amaxa P3 Primary Cell 4D Nucleofector X Kit and program EA-100 (LONZA). Transfected erythroid progenitors were cultured in ReproTeSR™ xeno-free reprogramming medium and later tran

Genomic DNA was extracted from iPSC cell lines using a DNA extraction kit (QIAGEN) and amplified through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR). MERTK gene mutation was verified via Sanger sequencing using forward primer GGAAGACCACATACAGGAA and reverse primer TGAAGGAAGCGATTATTGC.

Human iPSCs (hiPSCs) were treated for 2 h with colchicine to arrest cells in mitotic metaphase, followed by cell harvesting. Cells were then swollen via incubation in a pre-warmed 75 mmol/L KCl hypotonic solution at 37 °C for 15 min. Following cell swelling, cells were fixed using a freshly prepared methanol/acetic acid fixative solution. Cell suspensions were dropped and evenly spread onto pre-chilled glass slides. After air-drying the slides, they were stained with Giemsa working solution for 20-30 min, followed by rinsing and drying. Chromosome analysis was performed using a Zeiss Metafer chromosome automated scanning and imaging system.

For in vitro differentiation of three germ layers, iPSC aggregates were cultured in suspension within DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco) with 20% KSR (Gibco), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (Sigma), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Life Technologies), 10 mM Y-27632 (Selleck), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) supplement for 8 d to form embryoid bodies. Then the embryoid bodies were transferred into DMEM/F12 medium with 10% foetal bovine serum (Gibco), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 2 mM GlutaMAX 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin supplement, and attached to glass slides coated with 0.1% gelatin (Millipore) for 10 d.

The generated hiPSCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde after digestion into single cells. Following a 5-min incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100, the cells were blocked with a 3% fetal bovine serum solution for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with mouse monoclonal antibodies against human SSEA4 (Abcam, ab16287) or TRA-1-81 (Milli

EVs obtained through the EXODUS system were incubated with fluorescently labeled antibodies in the dark for 30 min. After resuspension in DPBS, the samples were centrifuged at 4 °C, 110000 g for 70 min twice to remove excess dye. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the samples were resuspended in PBS for analysis using a N30E Nano

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips at an appropriate density, fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min, and washed with PBS. Permeabilized and blocked cells with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 4% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody, then incubated with secondary antibody and DAPI solution for 1 h at room temperature. Following primary antibodies were used: OCT4 (Cat. #ab18976; Abcam), SOX2 (Cat. #sc-365823; Santa Cruz), NANOG (Cat. #ab80892; Abcam), SSEA4 (Cat. #ab16287; Abcam), GFAP (Cat. #HPA056030; Sigma), α-SMA (Cat. #A5228; Sigma), AFP (Cat. #MAB1368; R&D System). Images were acquired using an Olympus confocal system (SpinSR10, Japan).

Cells were seeded on plates at a density of 5.0 × 104 cells/cm2, and the supernatant was collected until the cells reached approximately 90% confluence. The supernatant was centrifuged at 4 °C 300 g for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 4 °C, 3000 g for 20 min, and temporary storage at -80 °C. Prior to EV separation, the supernatant was thawed at 4 °C, centrifuged at 4 °C 12000 g for 30 min, then filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. The EXODUS platform was employed for EV isolation, and after the program was run, the EVs were resuspended in DPBS and restored at -80 °C for subsequent steps.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis was employed to assess the size distribution and concentration of EVs using a NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern). The analysis settings were optimized, and each sample was diluted 1000- to 2000-fold with DPBS before measurement. Each sample was diluted in triplicate, and each diluted sample was measured three times with a capture time of 30 s to ensure measurement accuracy (Supplementary Figure 1B).

EVs were diluted to an appropriate concentration and then dripped on carbon-coated copper grids for 90 s. Subsequently, negative staining was performed with uranyl acetate dye for 30 s; excess dye was removed; and the sample was dried. Images were captured using a Tecnai G2 12 transmission electron microscope (FEI, United States) (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Library preparation and sequencing of iPSCs were executed as previously described[22]. Briefly, total RNA from lysed samples was extracted using TRIzol™ Reagent, while the total RNA from EVs was extracted using the exoRNeasy Serum/Plasma Maxi Kit (Qiagen). The purity and integrity of RNA in the samples were assessed, and mycoplasma contamination detection was performed. Libraries were constructed using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II RNA Library Prep Kit and NEBNext Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set (NEB, United States). High-throughput sequencing was conducted on the Illumina PE150 and SE50 platform. Data were aligned to the human genome (version hg38), and miRNA and target genes were predicted using TargetScan and miRanda databases. Additionally, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and co-expression target gene correlations were calculated using cor.test R (version 4.3.0) for data analysis and visualization. Library construction and sequencing were conducted by Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd.

The total protein was extracted from the samples, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method. Specimen separation was achieved using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by 4D label-free detection and quantification analysis using the timsTOF pro2 platform (Novogene Bioin

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) analysis was conducted using previously published protocol[23]. Briefly, 2000 cells per well were seeded on a 96-well plate. After 12-h culture, 10-μL CCK-8 solution was added to each well. After incubation in the dark for 1 h, the absorbance value at 450 nm was detected by a microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 and R Studio software (version 4.3). All data are presented as the mean ± standard error. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups.

A young proband presenting with night blindness and progressive vision loss was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), while neither parent exhibited similar symptoms (Figure 1A). Exon sequencing targeting 164 recognized genes associated with retinal diseases was executed[24], revealing a homozygous MERTK gene mutation (c.296_297delCA). Sanger sequencing confirmed the mutation (Figure 1B). This deletion caused a frameshift mutation, resulting in the substitution of the 99th threonine with serine and the appearance of a new reading frame. Translation terminated at the 8th codon downstream (Figure 1C)[25]. Protein tertiary structure prediction showed that the normal MERTK protein exhibited complex protein domains, while the mutant MERTK protein retained only a short peptide chain (Figure 1D). The Single Cell Portal database indicated that the MERTK gene was expressed in various cell types found in ophthalmic tissue, such as rods, cones, bipolar cells, microglia, retinal pigment epithelium, etc. (Figure 1E).

Fresh peripheral blood obtained from the MERTK patient and healthy individuals was used to generate iPSC lines using a non-viral, non-integrating method (Figure 2A). The generated iPSC clones displayed clear edges and close-packed cells (Figure 2B) and exhibited a normal karyotype (Figure 2C). More than 90% of cells expressed stem cell markers SSEA4 and TRA-1-81 (Figure 2D). Both iPSC lines were subjected to immunofluorescence staining for pluripotency markers SSEA4, OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG (Figure 2E and F). In vitro differentiation demonstrated that the iPSCs from the patient and control were capable of differentiation into three germ layers (Figure 2G and H). These results demonstrated the successful construction of patient-specific iPSCs with a homozygous MERTK mutation.

Despite their similar appearance, MERTK-mutated iPSCs showed slight deviations from the control iPSCs under the same culture conditions. On the 2nd to 3rd d after passage, the robust proliferative capability of the stem cells resulted in gradual expansion of the cell clones. On the VTN-coated culture plate, the majority of iPSC clones from the control group adhered tightly to the plate and exhibited extensive growth, with only a few small clones or individual cells floating on the surface of the culture medium (Figure 3A). However, iPSCs with the MERTK mutation showed both large and small clones floating on the surface of the culture medium (Figure 3B). Furthermore, during the directed induction of epithelial cell differentiation, control cells displayed neat and close arrangement on the culture plate (Figure 3C), whereas cells with a MERTK mutation tended to float on the surface of the culture medium, resulting in large voids and reduced differentiation efficiency (Figure 3D). CCK-8 detection confirmed that there was no significant difference in the proliferation ability of the two groups (Figure 3E). The cadherin family is a group of transmembrane proteins that play an important role in cell junction or adhesion[26]. RNA-seq data suggested that the expressions of the cadherin subfamily members DCHS1 and CELSR2 were downregulated in iPSCs with a MERTK mutation, and quantitative PCR approved this result (Figure 3F, Supplementary Figure 2A).

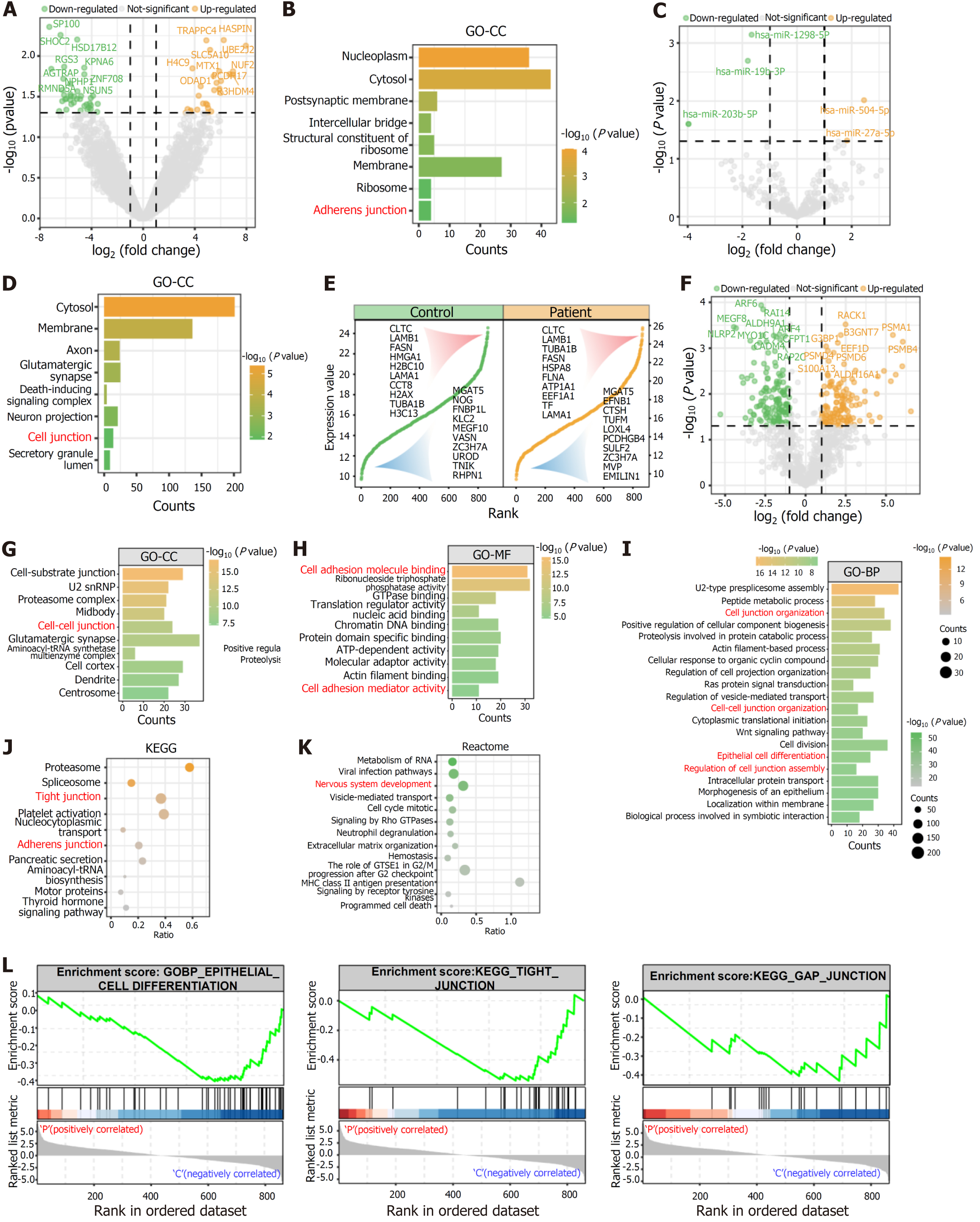

Principal component analysis displayed certain differences between the gene expressions of two iPSC lines (Figure 4A). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of differentially expressed mRNA revealed differences in cell differentiation and cell adhesion (Figure 4B-D). A total of 121 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified, and GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of their predicted target genes indicated their involvement in cell adhesion, cell-cell junction, and cell differentiation (Figure 4E-G). Additionally, these target genes were significantly associated with central nervous system development, the extracellular matrix, and extracellular exosome. Similarly, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the predicted target genes of differentially expressed lncRNA showed similar results (Supplementary Figure 3). The number of DEPs in iPSCs was significantly fewer than that of RNA (Figure 4H). GO and Reactome pathway enrichment analyses of these DEPs suggested that MERTK-mutated iPSCs exhibited reduced mesodermal development potential and lower protein expressions of gap junction trafficking and regulation compared to the control (Figure 4I). These findings indicated that MERTK-mutated iPSCs had reduced cell adhesion capacity and differentiation potential.

EVs played a crucial role in regulating the extracellular microenvironment, and the transcriptomics and proteomics profiles indicated that MERTK-mutated iPSCs displayed different gene and protein expressions in the extracellular matrix and extracellular exosomes compared to the control (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure 3D). Compared to the intracellular RNA components, the amount of differentially expressed RNA cargos in the EVs was significantly lower (Figure 5A and C). GO-cellular component enrichment analysis revealed that the differentially expressed mRNA cargo in MERTK-mutated iPSC-derived EVs was significantly enriched in the adherens junction (Figure 5B). GO enrichment analysis of the predicted target genes of differentially expressed miRNAs and lncRNAs indicated that MERTK-mutated iPSC-derived EVs might regulate cell junctions (Figure 5D, Supplementary Figure 4).

Using a 4D-label free proteomics platform, we detected more than 800 proteins in the two types of vesicles and found an overlap between some of the top 10 and bottom 10 expressed proteins between patient iPSCs and control iPSCs (Figure 5E). DEPs were more abundant compared to RNA cargos in the two types of EVs (Figure 5F). GO analysis revealed that these DEPs were significantly enriched in cell-cell junctions, cell junction organization, regulation of cell junction assembly, and cell adhesion activity (Figure 5G-I). Additionally, these DEPs potentially impact epithelial cell differentiation (Figure 5I). KEGG and Reactome pathway enrichment analyses revealed that DEPs were significantly enriched in tight junction, adherens junction, and signaling by Rho GTPases (Figure 5J and K). Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that patient-specific iPSC-derived EVs might be involved in downregulated tight junction, gap junction, and epithelial cell differentiation potential (Figure 5L).

The invention of iPSC technology has provided new opportunities for the treatment of degenerative diseases. Patient-specific iPSCs facilitate personalized treatment. In this study, iPSCs were generated from fresh peripheral blood rather than skin fibroblasts to minimize UV exposure-associated DNA damage[27]. The non-integrating plasmid repro

Strict criteria and specific standards are required for validating iPSCs as genuine and appropriate entities for research and clinical purposes. These characteristics are crucial for ensuring the dependability, replicability, and security of iPSC-derived products. In previous publications, researchers typically control the quality of iPSCs through several aspects. First, iPSCs need possess the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers, ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm, which is typically confirmed by in vitro differentiation experiments or by the establishment of teratoma formation in vivo. Here, we performed in vitro differentiation and completed immunofluorescence staining for typical markers AFP, α-SMA, and GFAP of three germ layers[20], which demonstrated the pluripotency of generated iPSCs (Figure 2G and H). Second, iPSCs must express pluripotency markers, such as OCT4, SOX2, SSEA-4, TRA-1-81, and NANOG, which have been confirmed in this study by immunofluorescence staining or flow cytometry. Third, iPSCs need display similar biological and functional characteristics to ESCs, such as similar morphology, proliferation ability, gene expression patterns, or typical markers. In this study, CCK-8 analysis demonstrated similar division and proliferation under the same laboratory circumstance. This study lacked a more in-depth comparison between iPSCs and ESCs. G-banding chromosome karyotype analysis was commonly used for evaluating the genetic stability of PSCs, and detecting structural and numerical variations in chromosomes. However, it has limited detection sensitivity, which makes it difficult to identify variations below the threshold through the microscope. Therefore, pre-clinical or clinical study requires whole exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing to reach a higher diagnostic efficiency[28-30]. Episomal iPSC reprogramming plasmids used in this study are a non-viral, non-integrating system that allows reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs in feeder-free conditions. After about 10 cell cycles, most episomal plasmids are lost, leading to the generation of iPSCs free of genomic integration or genetic alterations. Generated iPSCs by this system even can be utilized for pre-clinical research and human gene therapy according to manual (catalog# SC900A-1). Chemical reprogramming provides an innovative approach, with higher controllability and ease of standardization, holding promising prospects for future clinical applications, although it has not been widely applied[31]. Furthermore, we are exploring the directed differentiation into several cell types in a controlled setting using these iPSC lines.

The establishment of iPSCs is a prerequisite for subsequent directed differentiation, requiring iPSCs to have good proliferative capabilities and multidirectional differentiation potential. However, there is no clear assessment index for the differentiation potential of stem cells. During the differentiation process of retinal epithelial cells, in the early stage of directional induction, large-scale detachment of MERTK mutant cells led to the appearance of a large space at the bottom of the culture plate, and the cells along the edge of the space exhibited morphology alterations, from tightly connected round cells to spindle cells with irregular edges, which were similar to the characteristics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Figure 3). These cells usually cannot be further induced into terminal cells. Our statistics demonstrated that the probability of differentiation failure is approximately 50%, although this phenomenon has never been reported to have occurred in healthy iPSCs or ESCs. A previous study indicated that cell adhesion and cell junctions influence differentiation and development[27,32-34]. Furthermore, cell differentiation and cell-cell adhesion are influenced by disparities in protein expressions[35,36]. We investigated this phenomenon by examining RNA and protein expression. Our systematic transcriptomics and proteomics analyses revealed that iPSCs carrying a MERTK mutation exhibited differential expression of genes that are significantly involved in the regulation of cell junction, adherens junction, tight junction, gap junction, focal adhesion, and cell differentiation (Figure 4). Additionally, a recent study reported that defects in mitochondrial gene expression led to reduced stem cell differentiation potential[18]. In our study, the expression of representative mitochondrial genes, MT-ND1, MT-ND2, and MT-ND4, were significantly reduced in MERTK mutant cells (Supplementary Figure 2), which might have caused aberrant differentiation potential. However, the specific mechanism by which energy metabolism affects cell differentiation potential through epigenetics is the focus of attention in the field and requires further exploration.

iPSCs transcriptomics analysis suggested differences in gene expression related to EV secretion between the two types of iPSCs. EVs contain various bioactive substances and play an important role in regulating cell junction, adhesion, cell growth, development, and differentiation. Xie et al[37] reported that EVs from nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells containing miR-455 could target reducing zonula occludens 1 expression. Chai et al[38] found that BCR-ABL1-driven exosome-miR130a-3p interacted with gap-junction Cx43, thereby affecting gap junctional intercellular communications. Moreover, circulating EVs from sickle cell patients have been shown to regulate endothelial gap junctions[39]. EVs act as important paracrine mediators, providing biochemical cues for inducing stem cell differentiation[40,41]. Therefore, we collected the supernatants of the two types of iPSCs to isolate EVs and conducted transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. The systematic analysis revealed that differential RNA expression was significantly enriched in neural system development, adhesion connection, and cell cycle regulation. Using 4D label-free high-throughput sequencing technology, we found that the DEPs in EVs were more abundant and prominently clustered in cell connections, adhesion connections, as well as cell cycle and programmed cell death. While there were fewer differential RNAs in the exosomes, there were more differential proteins compared to cells. EVs derived from iPSCs with a MERTK mutation exhibited poorer ability to regulate cell adhesion, greater ability to regulate apoptosis or programmed cell death, and poorer ability to regulate cell differentiation. These results suggested that proteins in EVs play a more important role in regulating stem cell proliferation and differentiation, and the biological property of EVs is an important dimension for more fully characterizing iPSCs.

However, this research has some limitations. The phenotypic differences among iPSCs, such as differentiation potential and cell morphology, have a 5%-46% possibility of being attributed to individual variations[42]. In addition to genetic background, donor-specific epigenetics after reprogramming may influence stem cell variability[36], and the expression of quantitative trait loci might also contribute to the maintenance of iPSC lines and their differentiation capability[36,43]. Due to the extremely low incidence of this homozygous mutation on the second exon, we lacked the additional samples necessary for validating the phenotype. Nevertheless, this research provides evidence indicating that iPSCs carrying a MERTK gene mutation may exhibit altered junctions and aberrant differentiation potential.

In this study, we reported for the first time a homozygous mutation in the MERTK gene (c.296_297delCA, p.T99Sfs*8) and established an iPSC line associated with this mutation. We also reported, for the first time, that iPSCs with a MERTK mutation show impaired adhesion capabilities, tight junctions, and directional differentiation potential. By combining cellular RNA and protein expression with EV components, we revealed that intracellular components and EVs colle

We first reported a homozygous mutation in the MERTK gene (c.296_297delCA, p.T99Sfs*8) and established an iPSC line associated with this mutation. We demonstrated that iPSCs with a MERTK mutation exhibited impaired adhesion capabilities, tight junctions, and directional differentiation potential. Our findings elucidated the collective regulation of intracellular components and EVs on cell tight junctions and cellular differentiation. These findings highlighted the importance of repairing the pathogenic gene mutations prior to stem cell therapy.

| 1. | Doss MX, Sachinidis A. Current Challenges of iPSC-Based Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Implications. Cells. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yan YW, Qian ES, Woodard LE, Bejoy J. Neural lineage differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells: Advances in disease modeling. World J Stem Cells. 2023;15:530-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14327] [Cited by in RCA: 14574] [Article Influence: 809.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamanaka S. Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapy-Promise and Challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:523-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 815] [Article Influence: 163.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Mandai M, Watanabe A, Kurimoto Y, Hirami Y, Morinaga C, Daimon T, Fujihara M, Akimaru H, Sakai N, Shibata Y, Terada M, Nomiya Y, Tanishima S, Nakamura M, Kamao H, Sugita S, Onishi A, Ito T, Fujita K, Kawamata S, Go MJ, Shinohara C, Hata KI, Sawada M, Yamamoto M, Ohta S, Ohara Y, Yoshida K, Kuwahara J, Kitano Y, Amano N, Umekage M, Kitaoka F, Tanaka A, Okada C, Takasu N, Ogawa S, Yamanaka S, Takahashi M. Autologous Induced Stem-Cell-Derived Retinal Cells for Macular Degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1038-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 910] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 114.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liang Y, Sun X, Duan C, Tang S, Chen J. Application of patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells and organoids in inherited retinal diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles as a cell-free therapy for traumatic brain injury via neuroprotection and neurorestoration. Neural Regen Res. 2024;19:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6920] [Cited by in RCA: 7557] [Article Influence: 1259.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Manai F, Smedowski A, Kaarniranta K, Comincini S, Amadio M. Extracellular vesicles in degenerative retinal diseases: A new therapeutic paradigm. J Control Release. 2024;365:448-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen N, Wang YL, Sun HF, Wang ZY, Zhang Q, Fan FY, Ma YC, Liu FX, Zhang YK. Potential regulatory effects of stem cell exosomes on inflammatory response in ischemic stroke treatment. World J Stem Cells. 2023;15:561-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Gao X, Gao H, Shao W, Wang J, Li M, Liu S. The Extracellular Vesicle-Macrophage Regulatory Axis: A Novel Pathogenesis for Endometriosis. Biomolecules. 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Keshtkar S, Azarpira N, Ghahremani MH. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: novel frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 675] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bi Y, Qiao X, Liu Q, Song S, Zhu K, Qiu X, Zhang X, Jia C, Wang H, Yang Z, Zhang Y, Ji G. Systemic proteomics and miRNA profile analysis of exosomes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DeRyckere D, Huelse JM, Earp HS, Graham DK. TAM family kinases as therapeutic targets at the interface of cancer and immunity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:755-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou S, Li Y, Zhang Z, Yuan Y. An insight into the TAM system in Alzheimer's disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;116:109791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mikolajczyk A, Mitula F, Popiel D, Kaminska B, Wieczorek M, Pieczykolan J. Two-Front War on Cancer-Targeting TAM Receptors in Solid Tumour Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang H, Jiang J, Chen R, Lin Y, Chen H, Ling Q. The role of macrophage TAM receptor family in the acute-to-chronic progression of liver disease: From friend to foe? Liver Int. 2022;42:2620-2631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Meshrkey F, Scheulin KM, Littlejohn CM, Stabach J, Saikia B, Thorat V, Huang Y, LaFramboise T, Lesnefsky EJ, Rao RR, West FD, Iyer S. Induced pluripotent stem cells derived from patients carrying mitochondrial mutations exhibit altered bioenergetics and aberrant differentiation potential. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li YP, Liu H, Jin ZB. Generation of three human iPSC lines from a retinitis pigmentosa family with SLC7A14 mutation. Stem Cell Res. 2020;49:102075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Deng WL, Gao ML, Lei XL, Lv JN, Zhao H, He KW, Xia XX, Li LY, Chen YC, Li YP, Pan D, Xue T, Jin ZB. Gene Correction Reverses Ciliopathy and Photoreceptor Loss in iPSC-Derived Retinal Organoids from Retinitis Pigmentosa Patients. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10:1267-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gao ML, Zhang X, Han F, Xu J, Yu SJ, Jin K, Jin ZB. Functional microglia derived from human pluripotent stem cells empower retinal organ. Sci China Life Sci. 2022;65:1057-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu ZH, Zhang H, Zhang CJ, Yu SJ, Yuan J, Jin K, Jin ZB. REG1A protects retinal photoreceptors from blue light damage. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2023;1527:60-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang XF, Huang F, Wu KC, Wu J, Chen J, Pang CP, Lu F, Qu J, Jin ZB. Genotype-phenotype correlation and mutation spectrum in a large cohort of patients with inherited retinal dystrophy revealed by next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2015;17:271-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4254] [Cited by in RCA: 4079] [Article Influence: 151.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hudson JD, Tamilselvan E, Sotomayor M, Cooper SR. A complete Protocadherin-19 ectodomain model for evaluating epilepsy-causing mutations and potential protein interaction sites. Structure. 2021;29:1128-1143.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang H, Jin ZB. A rational consideration of the genomic instability of human-induced pluripotent stem cells for clinical applications. Sci China Life Sci. 2023;66:2198-2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Goffinet AM, Tissir F. Seven pass Cadherins CELSR1-3. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;69:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang H, Su B, Jiao L, Xu ZH, Zhang CJ, Nie J, Gao ML, Zhang YV, Jin ZB. Transplantation of GMP-grade human iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells in rodent model: the first pre-clinical study for safety and efficacy in China. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sun L, Li X, Tu L, Stucky A, Huang C, Chen X, Cai J, Li SC. RNA-sequencing combined with genome-wide allele-specific expression patterning identifies znf44 variants as a potential new driver gene for pediatric neuroblastoma. Cancer Control. 2023;30:10732748231175017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sampson JK, Sheth NU, Koparde VN, Scalora AF, Serrano MG, Lee V, Roberts CH, Jameson-Lee M, Ferreira-Gonzalez A, Manjili MH, Buck GA, Neale MC, Toor AA. Whole exome sequencing to estimate alloreactivity potential between donors and recipients in stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:566-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liuyang S, Wang G, Wang Y, He H, Lyu Y, Cheng L, Yang Z, Guan J, Fu Y, Zhu J, Zhong X, Sun S, Li C, Wang J, Deng H. Highly efficient and rapid generation of human pluripotent stem cells by chemical reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30:450-459.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Li MY, Miao WY, Wu QZ, He SJ, Yan G, Yang Y, Liu JJ, Taketo MM, Yu X. A Critical Role of Presynaptic Cadherin/Catenin/p140Cap Complexes in Stabilizing Spines and Functional Synapses in the Neocortex. Neuron. 2017;94:1155-1172.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lodge EJ, Xekouki P, Silva TS, Kochi C, Longui CA, Faucz FR, Santambrogio A, Mills JL, Pankratz N, Lane J, Sosnowska D, Hodgson T, Patist AL, Francis-West P, Helmbacher F, Stratakis C, Andoniadou CL. Requirement of FAT and DCHS protocadherins during hypothalamic-pituitary development. JCI Insight. 2020;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Moore KS, Moore R, Fulmer DB, Guo L, Gensemer C, Stairley R, Glover J, Beck TC, Morningstar JE, Biggs R, Muhkerjee R, Awgulewitsch A, Norris RA. DCHS1, Lix1L, and the Septin Cytoskeleton: Molecular and Developmental Etiology of Mitral Valve Prolapse. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mirauta BA, Seaton DD, Bensaddek D, Brenes A, Bonder MJ, Kilpinen H; HipSci Consortium, Stegle O, Lamond AI. Population-scale proteome variation in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Elife. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Volpato V, Webber C. Addressing variability in iPSC-derived models of human disease: guidelines to promote reproducibility. Dis Model Mech. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Xie L, Zhang K, You B, Yin H, Zhang P, Shan Y, Gu Z, Zhang Q. Hypoxic nasopharyngeal carcinoma-derived exosomal miR-455 increases vascular permeability by targeting ZO-1 to promote metastasis. Mol Carcinog. 2023;62:803-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chai C, Sui K, Tang J, Yu H, Yang C, Zhang H, Li SC, Zhong JF, Wang Z, Zhang X. BCR-ABL1-driven exosome-miR130b-3p-mediated gap-junction Cx43 MSC intercellular communications imply therapies of leukemic subclonal evolution. Theranostics. 2023;13:3943-3963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 39. | Gemel J, Mao Y, Lapping-Carr G, Beyer EC. Gap Junctions between Endothelial Cells Are Disrupted by Circulating Extracellular Vesicles from Sickle Cell Patients with Acute Chest Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Roballo KCS, Ambrosio CE, da Silveira JC. Protocol to Study the Role of Extracellular Vesicles During Induced Stem Cell Differentiation. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2273:63-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Wu Y, Gu S, Cobb JM, Dunn GH, Muth TA, Simchick CJ, Li B, Zhang W, Hua X. E2-Loaded Microcapsules and Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Injectable Scaffolds for Endometrial Regeneration Application. Tissue Eng Part A. 2024;30:115-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kilpinen H, Goncalves A, Leha A, Afzal V, Alasoo K, Ashford S, Bala S, Bensaddek D, Casale FP, Culley OJ, Danecek P, Faulconbridge A, Harrison PW, Kathuria A, McCarthy D, McCarthy SA, Meleckyte R, Memari Y, Moens N, Soares F, Mann A, Streeter I, Agu CA, Alderton A, Nelson R, Harper S, Patel M, White A, Patel SR, Clarke L, Halai R, Kirton CM, Kolb-Kokocinski A, Beales P, Birney E, Danovi D, Lamond AI, Ouwehand WH, Vallier L, Watt FM, Durbin R, Stegle O, Gaffney DJ. Common genetic variation drives molecular heterogeneity in human iPSCs. Nature. 2017;546:370-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Carcamo-Orive I, Hoffman GE, Cundiff P, Beckmann ND, D'Souza SL, Knowles JW, Patel A, Papatsenko D, Abbasi F, Reaven GM, Whalen S, Lee P, Shahbazi M, Henrion MYR, Zhu K, Wang S, Roussos P, Schadt EE, Pandey G, Chang R, Quertermous T, Lemischka I. Analysis of Transcriptional Variability in a Large Human iPSC Library Reveals Genetic and Non-genetic Determinants of Heterogeneity. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:518-532.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0