Published online Nov 26, 2024. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v16.i11.956

Revised: August 29, 2024

Accepted: October 16, 2024

Published online: November 26, 2024

Processing time: 172 Days and 4.3 Hours

Recent advancements in nanomedicine have highlighted the potential of exosome (Ex)-based therapies, utilizing naturally derived nanoparticles, as a novel app

To explore the targetability and anticancer effectiveness of small interfering peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 RNA (siPIN1)-loaded soluble a proliferation-inducing ligand (sAPRIL)-targeted Exs (designated as tEx[p]) in the treatment of colon cancer models.

tEx was generated by harvesting conditioned media from adipose-derived stem cells that had undergone transformation using pDisplay vectors encoding sAPRIL-binding peptide sequences. Subsequently, tEx[p] were created by incorporating PIN1 siRNA into the tEx using the Exofect kit. The therapeutic efficacy of these Exs was evaluated using both in vitro and in vivo models of colon cancer.

The tEx[p] group exhibited superior anticancer effects in comparison to other groups, including tEx, Ex[p], and Ex, demonstrated by the smallest tumor size, the slowest tumor growth rate, and the lightest weight of the excised tumors observed in the tEx[p] group (P < 0.05). Moreover, analyses of the excised tumor tissues, using western blot analysis and immunohistochemical staining, revealed that tEx[p] treatment resulted in the highest increase in E-cadherin expression and the most significant reduction in the mesenchymal markers Vimentin and Snail (P < 0.05), suggesting a more effective inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition tEx[p], likely due to the enhanced delivery of siPIN1.

The use of bioengineered Exs targeting sAPRIL and containing siPIN1 demonstrated superior efficacy in inhibiting tumor growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, highlighting their potential as a therapeutic strategy for colon cancer.

Core Tip: This study investigated the potential of bioengineered exosomes (Exs), specifically small interfering peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 RNA-loaded soluble a proliferation-inducing ligand-targeted Exs, in treating colon cancer. By targeting soluble A proliferation-inducing ligand and delivering small interfering peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1, these modified Exs demonstrated superior efficacy in inhibiting tumor growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition compared to standard Ex treatments. The findings highlight the promise of the novel targeted Exs, offering insights into the enhanced targetability and anticancer effectiveness of Ex-based therapies in oncological applications.

- Citation: Kim HJ, Lee DS, Park JH, Hong HE, Choi HJ, Kim OH, Kim SJ. Exosome-based strategy against colon cancer using small interfering RNA-loaded vesicles targeting soluble a proliferation-inducing ligand. World J Stem Cells 2024; 16(11): 956-973

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v16/i11/956.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v16.i11.956

Colorectal cancer, a prevalent digestive malignancy, often leads to patient mortality due to metastasis. Traditional chemotherapy is limited by considerable challenges, including cytotoxicity and non-specific effects that negatively impact healthy tissues, consequently diminishing the quality of life for patients[1]. This underscores the urgent need for targeted cancer therapies, which are capable of delivering a diverse range of therapeutic agents, not only including conventional chemotherapeutic regimens but also therapeutic proteins and genetic materials, offering a more precise and less harmful approach to cancer treatment.

Recent advancements have introduced drug-loaded exosomes (Ex) as a promising drug delivery system[2,3]. These Ex are capable of traversing complex biological barriers and mitigate several safety concerns associated with traditional drug delivery, including cytotoxicity, limited biodistribution, and inefficient targeted delivery. Especially, they offer an efficient means to transport chemical drugs and biological molecules (RNA, DNA, proteins) directly to the cytoplasm of target cells while avoiding degradation in endosomal and lysosomal pathways. Moreover, the composition and targeting specificity of these Ex can be customized by manipulating the cells that produce them or through in vitro drug loading, making them adaptable for various therapeutic purposes, including cancer treatment and tissue regeneration.

A proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily, recognized for its role as a soluble factor[4]. This ligand is predominantly produced by hematopoietic cells and is instrumental in the survival of B cells and the activation of T cells[5,6]. In contrast to its minimal expression in normal tissues, APRIL is significantly upregulated in various cancers, including digestive, hematological, and urothelial malignancies[7-10]. Its elevated expression is particularly notable in colorectal cancer, where it is associated with increased tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouridine (5-FU)[11,12]. APRIL’s contribution to cancer development is multifaceted, encompassing the promotion of tumor cell proliferation and survival across multiple cancer types. This study proposes that Ex designed to target soluble APRIL (sAPRIL) and carrying small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific to peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1) - an enzyme critically involved in cancer progression - may serve as an effective vehicle for delivering siPIN1 to colon cancer cells, thereby potentially amplifying anticancer outcomes. Our study is anticipated to offer insights into harnessing Ex-based delivery systems’ distinct properties, including their biocompatibility and capacity to penetrate biological barriers, for treating malignant diseases.

Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) were generously provided by Hurim BioCell Co. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). These ASCs were propagated in DMEM/low glucose medium (GibcoBRL, Carlsbad, CA, United States) that contained 1% penicillin-streptomycin (GibcoBRL), and were kept at a constant temperature of 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. In parallel, HCT116 cell lines (No. 30038; KCLB, Seoul, Republic of Korea), sourced from the Korea cell line bank (KCLB) were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT, United States). This growth medium was enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (GibcoBRL) under similar incubation conditions of 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified environment.

Colon cancer cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well spheroid plate. After an initial incubation period of 24 hours to allow spheroid formation, the cells were treated with the experimental drug Ex[p] and its control, sAPRIL-targeted Exs loaded with siPIN1 (tEx[p]), for a duration of 4 days. Following treatment, the spheroids were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C with 2 μM Calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI) using the LIVE/DEAD viability/cytotoxicity kit from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, United States). Calcein-AM is a non-fluorescent compound that is cleaved by intracellular esterases in living cells to produce intensely fluorescent Calcein, which is retained within cells that maintain membrane integrity. PI, on the other hand, penetrates cells with compromised membranes, marking dead cells with red fluorescence. The fluorescence signals were then observed using a Zeiss Axio Observer.A1 microscope, allowing for the assessment of cell viability and cytotoxicity within the spheroids.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the HCT116 colorectal cancer cells using G-DEX genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Intron Biotechnology, Sungnam, Repubulic of Korea). DNA fingerprinting analysis was conducted using the AmpFlSTR Identifiler PCR Amplification Kit from Applied Biosystems Inc. (ABI, Waltham, MA, United States). This process involved a single polymerase chain reaction cycle to amplify nine short tandem repeat markers - CSF1PO, D3S1358, D5S818, D7S820, D13S317, FGA, TH01, TPOX, and vWA - along with the Amelogenin marker for sex identification, all situated within highly polymorphic microsatellite regions. The amplified products were subsequently subjected to analysis with the ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer, also by Applied Biosystems. Following polymerase chain reaction, the products were treated with 95% formamide and then separated via electrophoresis on a 7 M urea polyacrylamide gel, which was run for 2 hours at 60 W. After drying, the gels were examined through autoradiography to visualize the DNA profiles.

Conditioned medium was obtained from ASC cultures with 90% confluency, post a 24-hour starvation period (absence of fetal bovine serum) and subsequent transfection with 4 μg of pDisplay-AP (sAPRIL-targeted peptide) for 24 hours. This medium was then centrifuged at 2500 × g for 15 minutes at 4 °C to eliminate cellular debris. Exo-Quick-TC reagent was added to the conditioned medium, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C. The isolation of Exs was conducted using differential centrifugation, initially at 10000 × g for 60 minutes at 4 °C. The resultant precipitate was further centrifuged at the same conditions to collect the pellet, which was then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To create siPIN1-loaded sAPRIL-targeting Exs, referred to as tEx[p], 25 nM PIN1 siRNA (procured from SantaCruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, United States) was encapsulated into Ex using the ExofectTM kit (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, United States), finalizing the cargo-loading step.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis was performed using the Zetaview instrument (Particle Metrix GmbH, Ammersee, Bavaria, Germany). During each analysis, 11 videos of 1 cycle each were recorded. The measurements adhered to the quality standards of having 50-150 particles per frame, a concentration of 107 particles/mL, and more than 20% valid tracks. The captured videos were then processed and analyzed with the integrated Zeta-view Software.

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, Ex suspended in PBS were placed on Formvar carbon-coated grids for 10 minutes, with any surplus liquid being absorbed using filter paper. These samples were then negatively stained using a 1% uranyl acetate solution for 10 minutes, followed by the removal of excess liquid with filter paper. The grids were then left to dry at ambient temperature. Finally, the prepared EVs were observed using a JEM1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operating at 60 kV.

Cell viability of HCT116 and HT29 cells were evaluated using Ez-cytox Cell viability assay kit (Itsbio, Seoul, Republic of Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer, which provided a quantitative assessment of cell viability across various treatment conditions involving escalating doses of 5-FU alone and in combination with tEx[p].

Flow cytometry was utilized to verify the proportion of tEx in the total Ex population. Ex derived from ASCs, transfected with 4 μg of pDisplay-sAPRIL, were labeled with an anti-myc antibody (supplied by R&D Pharmingen, San Francisco, CA, United States). To identify Ex markers, Exs produced from ASC cells were tagged with anti-CD63 antibodies and anti-CD81 antibodies, both sourced from BD Pharmingen. These samples were then incubated in darkness for 120 minutes at 5 °C. Subsequent analysis was performed using an Attune xT acoustic focusing cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA. United States).

HCT116 cells (1 × 10³) were seeded to form spheroids. After 24 hours, the spheroids were treated with siPIN1-loaded Exs and sAPRIL-targeted Exs loaded with siPIN1. Cell viability was evaluated using the LIVE/DEAD cytotoxicity assay (Invitrogen) after a 30-minute incubation at 37 °C. In this assay, live cells with intact membranes convert the non-fluorescent Calcein-AM into a brightly fluorescent Calcein, which was measured using a Cell Voyage CQ1 microscope (Yokogawa Electron Co., Musashino, Japan) to quantify spheroid viability.

Samples were processed using the EzRIPA Lysis kit (ATTO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for lysing, with protein concentrations determined via Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For western blot analysis, primary antibodies at a 1:1000 dilution were used from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, United States), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at a 1:2000 dilution from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, United States). The detection of specific immune complexes was performed using the Western Blotting Plus Chemiluminescence Reagent (Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States). The study employed primary antibodies targeting E-cadherin, Vimentin, Snail, PIN1, and β-actin, along with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, all sourced from Cell Signaling Technology.

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis began by permeabilizing spheroids using PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. Following permeabilization, the spheroids were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CD44 and CD133 (both from Abcam). After three washes with PBS, the samples were treated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:150 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI-containing VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories) for 1 minute. The expression of CD44 and CD133 was then visualized and analyzed using a Cell Voyage CQ1 microscope (Yokogawa Electron Co., Musashino, Japan). Immunohistochemistry analysis was performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections, which were first subjected to deparaffinization and rehydration through a graded ethanol series. Epitope retrieval was conducted following established protocols. The sections were then stained using specific antibodies against E-cadherin and Snail (supplied by Cell Signaling Technology). Finally, the stained sections were examined for antibody expression using a laser-scanning microscope (Eclipse TE300; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) to assess the expression levels of the targeted markers.

For the subcutaneous tumor growth study, 5-week-old male BALB/c nude mice, weighing 20-22 g and obtained from Orient Bio, Seongnam, Republic of Korea, were used. Following the guidelines of the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, the Catholic University of Korea, with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under permit number CUMC-2020-0119-05, the experiments were conducted. The mice were maintained in conditions of 20 °C to 26 °C under a light/dark cycle of 12 hours (lights on between 8:00 a.m. and 8:00 p.m.), housed in a ventilated cage system (37.9 cm × 19.9 cm × 13 cm) with an occupancy of five individuals per cage. Nutritional needs were met with a gamma-irradiated diet (TD 20182; Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, United States) and sterilized reverse osmosis water. Environmental enrichment for the mice included nesting materials and play tunnels to mitigate stress, with the uppermost cage tier shielded from intense illumination to accommodate the preference of mice for lower light levels (< 65 Lux). For the establishment of the xenograft model, each mouse received a subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 HCT116 cells. Body weights were recorded twice weekly, and measurable tumors were observed 3 days post-injection. Two weeks after generating the xenograft model, the mice were then divided into groups of five for in vivo treatment efficacy assessment, receiving intravenous treatments with PBS (control), Ex, tEx, Ex[p] + 25 nM siPIN, and tEx[p], each at 2 × 106 Ex particles in 100 μL PBS, administered thrice weekly for 21 days. Tumor sizes were measured twice weekly, calculating volume with the formula: Length × width2 × 0.5236. At the study’s conclusion, all mice were humanely euthanized, employing anesthesia via a gas mixture of oxygen and nitrous oxide followed by euthanasia with 100% carbon dioxide gas, ensuring minimal distress. Confirmation of death was via the cessation of respiratory and cardiovascular functions in room air for a minimum of 10 minutes. The study was designed considering humane endpoints for euthanasia, such as significant weight loss or inability to eat, and included welfare considerations like environmental enrichment and controlled housing conditions to minimize stress, adhering to the ARRIVE guidelines for responsible animal research practices.

Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA was performed to assess statistical differences between group means. Following ANOVA, Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for potential type I errors due to multiple testing, with adjusted P values indicating the significance levels between group comparisons. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed for statistical comparisons between groups. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

sAPRIL-targeted Ex were produced through a series of steps, fundamentally involving the genetic modification of ASCs, which functioned as donor cells (Figure 1A). Briefly, the sAPRIL-targeting peptide’s DNA sequence[4] was integrated into the pDisplay vector, which included a segment of the platelet-derived growth factors receptor transmembrane domain, utilizing specific restriction enzymes. This altered vector was subsequently utilized to transfect the ASCs. The transfected ASCs subsequently displayed the sAPRIL-targeting peptide on their cell membranes, ultimately secreting Ex bearing sAPRIL peptides (tEx) on their surfaces, a consequence of cell membrane’s budding process. In the final step, siPIN1 was encapsulated within the sAPRIL-targeted Exs (tEx), culminating in the creation of siPIN1-loaded sAPRIL-targeting Exs, designated as tEx[p]. Zetaview analysis revealed that these nanoparticles had an average size of 187.9 ± 105.3 nm, aligning with the typical size range of Exs, as corroborated by the TEM images (Figure 1B).

In colon cancer cells, PIN1 is known to regulate key proteins such as β-catenin and cyclin D1, contributing to increased cell proliferation, tumor growth, and possibly influencing resistance to therapy. The expression of PIN1 was compared using western blot analysis across various colon cancer cell lines, including HT29, HCT116, SW480, and SW620 cells. Among these cell lines, an increased expression of PIN1 was observed in HCT116 and SW620 cells (Figure 1C). To verify the successful expression of the sAPRIL peptide in tEx, flow cytometric analysis was conducted using Ex markers (CD63 and CD81) and tEx marker (myc) (Figure 1D) Ex and tEx did not exhibit significant differences in the expression of Ex markers CD63 (70.0% vs 72.9%) and CD81 (83.7% vs 82.0%), respectively. However, tEx showed a marked increase in the targeted Ex marker myc compared to Ex in both CD63-positive (61.3% vs 3.2%) and CD81-positive (78.1% vs 2.2%) cells, respectively (P < 0.05).

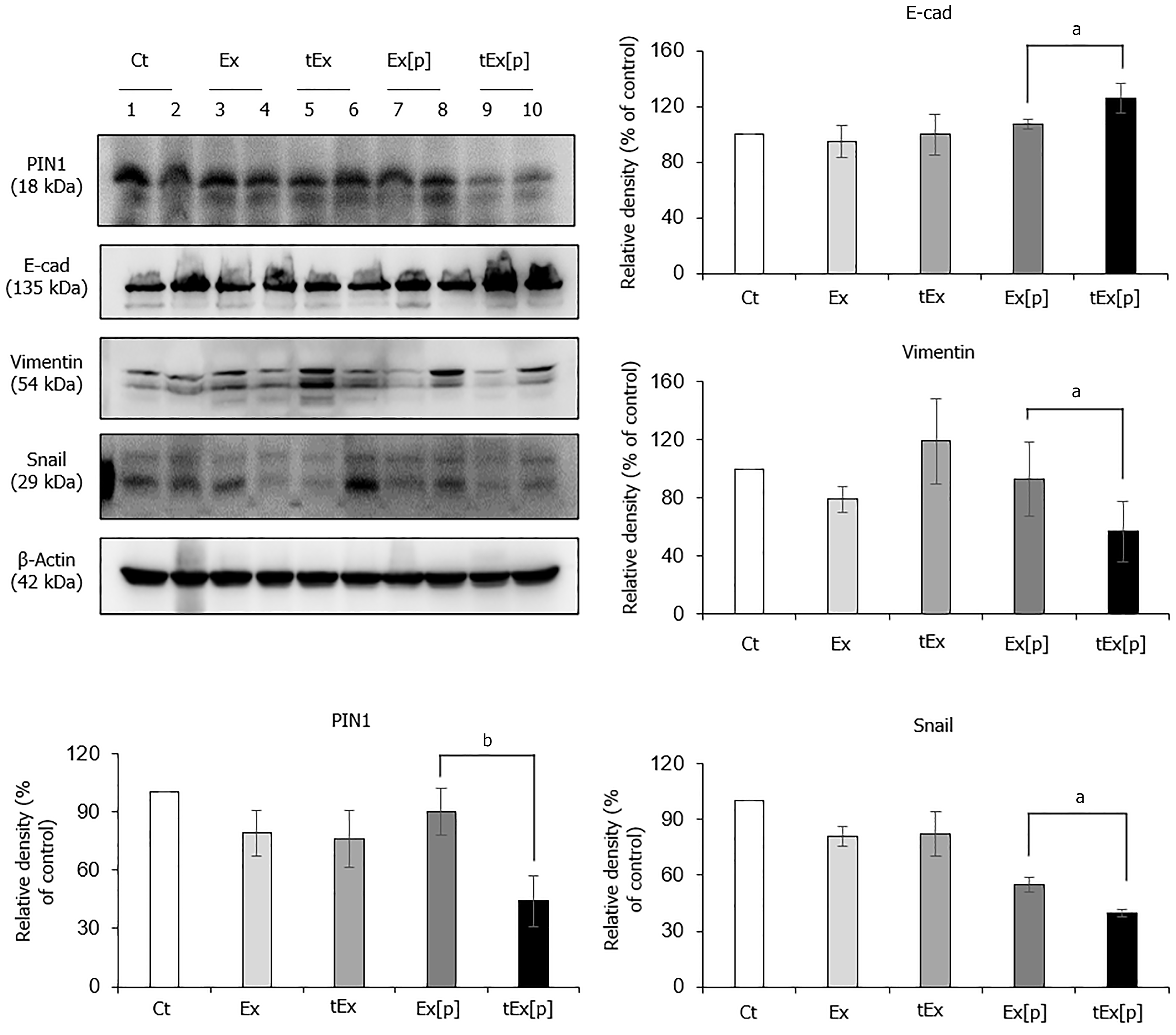

Western blot analysis was employed to evaluate the impact of different treatments on epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers in HCT116 colon cancer cells across five groups: Control (Ct), Exs without cargo (Ex), Exs loaded with siPIN1 (Ex[p]), sAPRIL-targeted Exs (tEx), and tEx[p]. Among these, the tEx[p] group showed the most significant increase in the epithelial marker E-cadherin (P < 0.05). Compared to the Ct group, the tEx[p] group also demonstrated a notable decrease in mesenchymal markers Snail and Vimentin, indicating the highest EMT inhibition effect across all groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). Subsequently, the impact of each treatment on the migration and invasion of HCT116 cells was analyzed using a wound healing assay. The tEx[p] group demonstrated the most notable reduction in HCT116 cell migration, with statistically significant results (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B).

Subsequently, the impact of tEx[p] on 5-FU chemosensitivity in colon cancer cell lines was evaluated. A significant decrease in cell viability was observed in both HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with escalating doses of 5-FU. Notably, the addition of tEx[p] to the treatment significantly enhanced the cytotoxic effects of 5-FU. In HCT116 cells, the combination of tEx[p] with 5-FU resulted in a marked reduction in cell viability across doses from 1 μmol/L to 25 μmol/L, more so than with 5-FU alone (Figure 3A left). In HT29 cells, this combined treatment also led to a significant decrease in viability at concentrations from 10 μmol/L to 100 μmol/L (Figure 3A right). These findings indicate that tEx[p] potentially boosts the chemotherapeutic efficacy of 5-FU, possibly by improving drug uptake or increasing the sensitivity of cancer cells to 5-FU-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, to compare the effects of API-1 (a PIN inhibitor) and tEx[p], IF analyses for EMT markers in HCT116 cells treated with API-1, Ex[p], and tEx[p], respectively, were performed. Our findings reveal that tEx[p] effectively influences EMT markers similarly to the known PIN1 inhibitor API-1, suggesting its potential as novel anticancer therapeutics inhibiting PIN1 expression (Figure 3B).

HCT116-derived spheroids were treated with Ex[p] and tEx[p] to assess their effects on spheroid viability. Fluorescence microscopy following LIVE/DEAD staining revealed a noticeable increase in cell death in the tEx[p] treated groups compared to those treated with Ex[p]. The analysis quantified a higher dead/live cell ratio in tumor spheroids treated with tEx[p], as indicated in (Figure 4A), suggesting that tEx[p] enhances cytotoxicity in tumor spheroids, possibly impacting cancer stem cell populations. Subsequently, IF analysis was conducted to assess the expression of cancer stem cell markers CD44 and CD133. The expression of these markers was notably reduced in spheroids treated with tEx[p] compared to Ex[p], suggesting that tEx[p] not only increases cell death but also effectively targets cancer stem cells within the spheroids (Figure 4B).

In a controlled in vivo study, male BALB/c nude mice, 5-weeks-old, were utilized to establish a comparative model for subcutaneous tumor growth. HCT116 cells (5 × 106) were injected subcutaneously into each mouse. Three days after the initial injection, the mice were allocated into five groups, each consisting of five individuals. Each group received an injection of 100 μL of either normal saline (Ct), Ex, tEx, Ex[p], or tEx[p], respective to their group assignment. Each group received their respective treatment thrice weekly for 3 weeks, totaling nine administrations. Figure 4C displays the external appearance of mice, highlighting the xenograft masses and a comparison of the sizes of the excised xenograft masses from each group. Measurements of body weight and tumor volume were conducted biweekly until the 20th day after initial treatment. There was no significant variation in body weight among the groups (Figure 4D). From day 18 post-treatment, tEx[p] group exhibited the smallest tumor volume (Figure 4E). On the 20th day post-treatment, the tEx[p] group also recorded the smallest tumor weight among all groups (Figure 4F).

To determine the anticancer effects of each material, western blot analysis was conducted on the excised tumor tissues (Figure 5). The tEx[p] group showed the lowest expression of PIN1 in the excised tumor tissues (P < 0.05). Additionally, concerning EMT markers, this group exhibited the highest expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and the lowest expression of mesenchymal markers Vimentin and Snail (P < 0.05). These results suggest that tEx[p] was the most efficient in delivering siPIN1 to target tumor cells, leading to the greatest inhibition of PIN1 expression and, conse

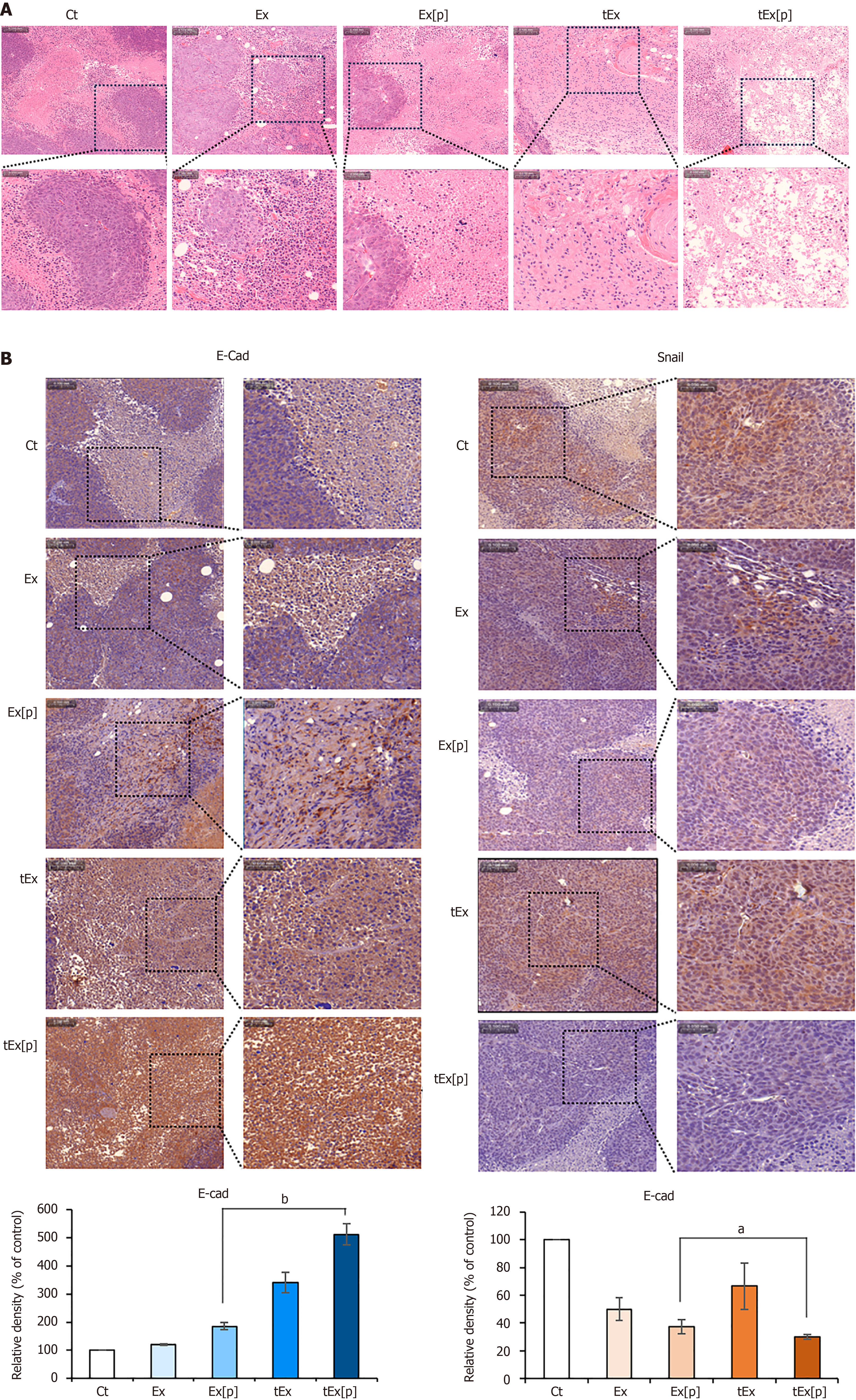

Histological examinations were carried out on excised tumor tissues from different treatment groups in a mouse model of colorectal cancer xenografts. The tumor masses, once removed, were processed for analysis. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed that the tEx[p] group had a significantly reduced density of tumor cells (Figure 6A). Further analysis was conducted on the expression of epithelial markers in the excised tissues using immunohistochemistry. The tEx[p] group showed a marked increase in E-cadherin immunoreactivity and a substantial decrease in Snail immunoreactivity, indicating its superior efficacy in inhibiting EMT compared to other groups (Figure 6B).

Exs, recognized for their biocompatibility, show promise as vehicles for drug and gene delivery, with genetic engineering methods enhancing their specificity for targeted cell types. This study explored the application of bioengineered Ex in treating colon cancer, conducting experiments with both in vitro and in vivo models of the disease. A comparative analysis was conducted to assess the therapeutic efficacy of siPIN1-loaded sAPRIL-binding Ex, designated herein as tEx[p]. The tEx[p] group exhibited superior anticancer effects in comparison to other groups, including tEx, Ex[p], and Ex, demonstrated by the smallest tumor size, the slowest tumor growth rate, and the lightest weight of the excised tumors observed in the tEx[p] group. Moreover, analyses of the excised tumor tissues, using western blot analysis and immunohistochemical staining, revealed that tEx[p] treatment resulted in the highest increase in E-cadherin expression and the most significant reduction in the mesenchymal markers Vimentin and Snail, suggesting a more effective inhibition of EMT tEx[p], likely due to the enhanced delivery of siPIN1. Overall, these results strongly support the use of bioengineered Ex that both target sAPRIL and contain siPIN1 as effective agents in colon cancer therapy.

Inhibiting APRIL’s activity is a promising strategy to combat colorectal cancer. APRIL plays a crucial role in cancer progression by interacting with several receptors, including B-cell maturation antigen, transmembrane activator and CAML interactor, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans[4]. These interactions trigger molecular events that enhance cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis, facilitating tumor growth. They activate nuclear factor-kappa B, upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein, and modulate cell cycle proteins[4]. Research shows that disrupting APRIL expression in colorectal cancer cells impedes transforming growth factor-β1 signaling and extracellular regulated protein kinases activation, halting cell growth and inducing apoptosis[13]. Reducing APRIL expression decreases cell proliferation and metastasis, increases apoptosis rates, and improves responsiveness to 5-FU chemotherapy. The use of anti-APRIL monoclonal antibodies effectively curbs tumor growth in vitro and in vivo, while recombinant or mutant sAPRIL receptors can also demonstrate anticancer effects, highlighting the potential of these strategies in cancer treatment[14,15].

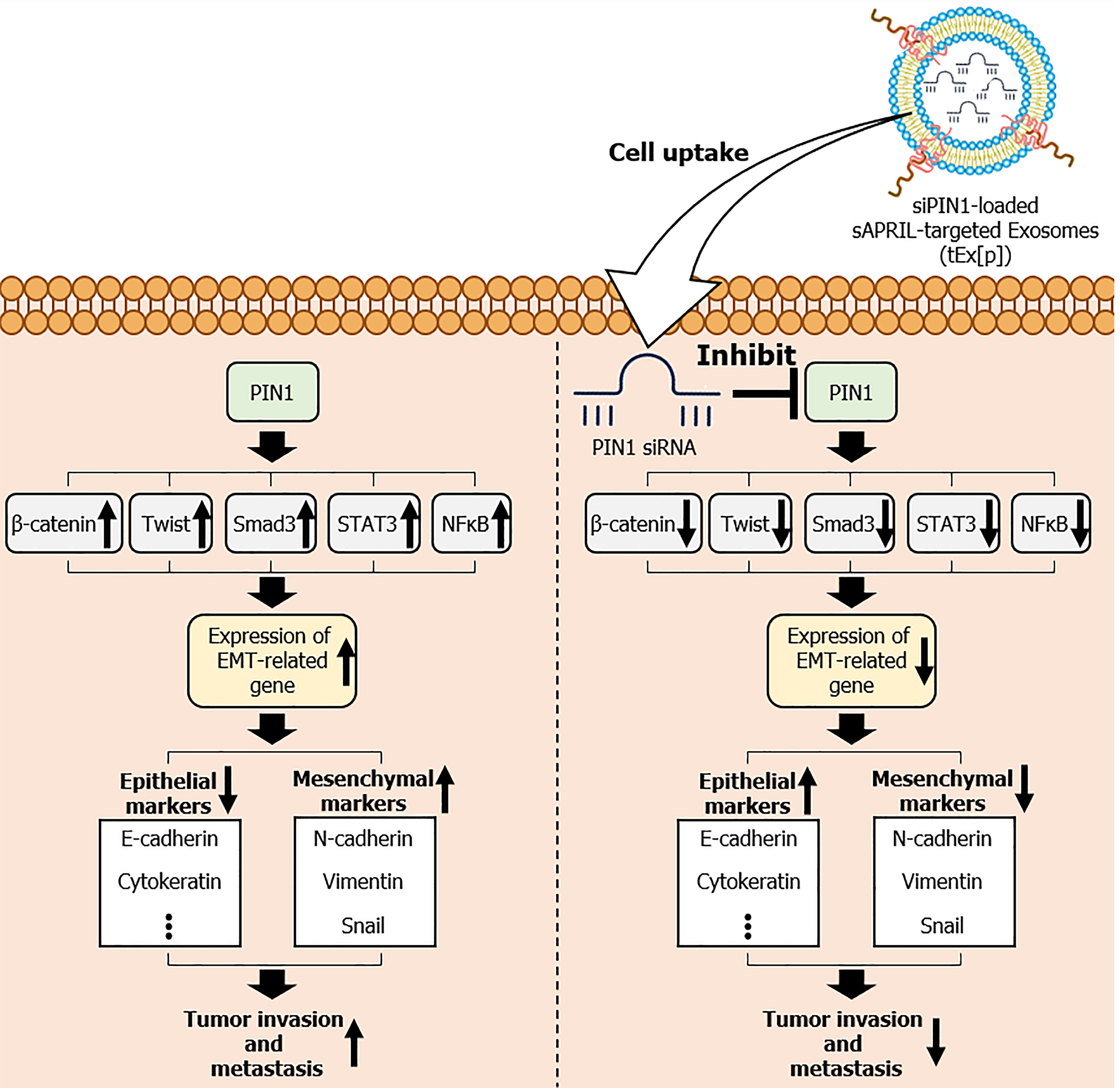

PIN1, known for its regulatory role in cell signaling, is closely associated with colon cancer progression due to its involvement in promoting cell proliferation, survival, and resistance to therapy[16,17]. It primarily functions by altering the conformation of specific proteins, which can influence various cellular processes such as cell cycle regulation, signal transduction, and gene expression. In the context of cancer, PIN1 has been found to be overexpressed in various types of tumors, and its elevated levels are often associated with advanced disease stages, aggressive tumor phenotypes, and poor prognosis. Overexpression of PIN1 results in decreased expression of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin and cytokeratin, and increased expression of mesenchymal markers like N-cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail, thereby promoting EMT[18]. This process is facilitated by the activation of signaling pathways involving β-catenin[19,20], Twist[21], small mothers against decapentaplegic 3[22], signal transducer and activator of transcription 3[23,24], and nuclear factor-kappa B[24], all of which contribute to increased cell migration and invasiveness (Figure 7). Our study demonstrates that tEx[p] effectively counteract the effects of PIN1 overexpression. By delivering siPIN1 directly to tumor cells, these engineered Exs inhibit PIN1 activity, thereby reducing EMT and exhibiting strong antitumor effects. The tEx[p] group showed the most significant reduction in tumor size, growth rate, and weight compared to other treatment groups. Additionally, western blot and immunohistochemical analyses revealed the highest increase in E-cadherin expression and the most substantial decrease in mesenchymal markers Vimentin and Snail in the tEx[p] group, confirming the effective inhibition of EMT. These results underscore the potential of using bioengineered Exs that target sAPRIL and encapsulate siPIN1 as a novel and effective therapeutic strategy in colon cancer treatment. By leveraging the specificity and delivery efficiency of these Exs, this approach offers a promising avenue for reducing tumor progression and enhancing treatment outcomes.

The potential clinical application of tEx[p] holds significant promise in improving cancer treatment outcomes, particularly by addressing the limitations of traditional chemotherapy[25,26]. One of the key advantages of tEx[p] is their ability to minimize the cytotoxicity associated with conventional chemotherapeutic regimens. By specifically targeting PIN1-positive tumor cells, these engineered Exs can deliver therapeutic agents directly to the cancer cells, reducing the impact on healthy tissues and thereby minimizing adverse side effects. Furthermore, tEx[p] could be effectively utilized as an adjuvant treatment following surgical resection, especially in cases where pathology reports indicate the presence of PIN1-positive tumor cells. This targeted approach could help eliminate residual cancer cells, potentially reducing the risk of recurrence and improving long-term patient outcomes. However, several challenges must be addressed for the successful clinical translation of tEx[p]. These include ensuring the scalability and reproducibility of Ex production, establishing standardized protocols for Ex isolation and characterization, and overcoming potential immunogenicity and biodistribution issues in patients. Additionally, extensive clinical trials will be necessary to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing strategies for tEx[p] in diverse patient populations. Addressing these challenges will be critical to unlocking the full potential of tEx[p] as a novel therapeutic modality in cancer treatment.

Recent studies have underscored the potential of targeting cancer stem cells and utilizing Exs in cancer therapy, which aligns with our development of tEx[p] as a promising treatment strategy. Targeting cancer stem cells has been shown to significantly reduce tumor recurrence and metastasis[27], supporting the efficacy of our approach in inhibiting critical pathways for cancer cell survival. Exs offer substantial advantages as delivery vehicles due to their ability to cross biological barriers and specifically target tumor cells[28], enhancing the precision and effectiveness of therapeutic delivery. Furthermore, Exs play a pivotal role in modulating the tumor microenvironment and are capable of delivering therapeutic nucleic acids and proteins[29], which broadens their application in cancer treatment. The surface modification of Exs can improve targeting specificity[30], a key component of our strategy to engineer Exs that express sAPRIL-binding peptides for precise targeting of PIN1-positive tumors. However, despite their promise, Ex-based therapies face challenges such as the need for standardized production and characterization[31]. These challenges must be addressed to fully realize the clinical potential of Ex-based treatments. Collectively, these insights highlight both the innovative potential and current challenges of Ex and cancer stem cell targeting, reinforcing the rationale for developing tEx[p] as a novel therapeutic strategy for colorectal cancer.

The advantage of using Ex as a drug delivery system platform lies in their ability to bind various materials both internally and externally[2,3]. This study involved the genetic engineering of ASCs (donor cells) to express sAPRIL-binding peptides on the surface of Ex and encapsulate siPIN1 within them. This flexibility allows for diversifying and optimizing the ligands expressed on the surface and cargoes carried inside, according to specific needs. Numerous studies have shown that Ex can act as safe and effective drug delivery vehicles targeting specific tissues[32-38]. Promising outcomes have been observed in various animal models relevant to human diseases, and the clinical application of Ex has begun, with their safety being affirmed[32,34,36,38,39]. Despite these advancements, Ex research is still at an early stage, facing significant clinical translation challenges. Variability among Exs necessitates precise control over their sourcing, production, and disease-specific modifications. Addressing the need for scalable production, consistent isolation, and stringent quality standards is critical for their therapeutic use. Furthermore, customizing Exs for targeted therapies adds complexity, requiring advanced modification techniques. These obstacles highlight the importance of focused research to overcome these barriers for successful clinical applications.

Our study has several limitations. One limitation of this study involves the use of mouse models, which may not fully replicate the complexity of human colon cancer, potentially affecting the translatability of our findings to human clinical settings. Additionally, the application of our approach in clinical settings necessitates the standardization of processes, a challenging task given the inherent heterogeneity of Exs. Finally, gene-based therapies like siRNA are specific to certain genetic targets, making them less broadly effective than chemotoxic drugs, which may impact their overall utility in cancer treatment.

In summary, the study demonstrated that tEx[p] had superior anticancer effects compared to other treatment groups, both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, tEx[p] showed the most significant increase in the epithelial marker E-cadherin and a decrease in mesenchymal markers, indicating effective inhibition of EMT. In vivo, the tEx[p] treatment resulted in the smallest tumor size, slowest tumor growth rate, and lightest tumor weight. These findings suggest tEx[p]’s enhanced delivery of siPIN1 as a potent strategy for colorectal cancer therapy. Research on bioengineered Exs is not as extensive as that on artificial nanoparticles like lipid nanoparticles. Exs, being natural nanoparticles, offer superior biocompatibility. Additionally, once stable engineered cell lines are established, they could enable the long-term production of biotherapeutics without complex chemical reactions, offering a significant advantage over traditional methods. This highlights the potential of Exs in the development of novel therapeutic strategies. These research findings warrant further validation through larger animal studies to facilitate their transition into clinical trials.

We express our gratitude to Jeong-Yeon Seo for manuscript processing and to Jennifer Lee for the contributions in illustration work.

| 1. | Alrushaid N, Khan FA, Al-Suhaimi E, Elaissari A. Progress and Perspectives in Colon Cancer Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatments. Diseases. 2023;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee CS, Lee M, Na K, Hwang HS. Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Cancer Therapy and Tissue Engineering Applications. Mol Pharm. 2023;20:5278-5311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sonbhadra S, Mehak, Pandey LM. Biogenesis, Isolation, and Detection of Exosomes and Their Potential in Therapeutics and Diagnostics. Biosensors (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | He XQ, Guan J, Liu F, Li J, He MR. Identification of the sAPRIL binding peptide and its growth inhibition effects in the colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mackay F, Schneider P, Rennert P, Browning J. BAFF AND APRIL: a tutorial on B cell survival. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:231-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 714] [Cited by in RCA: 751] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Medema JP, Planelles-Carazo L, Hardenberg G, Hahne M. The uncertain glory of APRIL. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1121-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moreaux J, Veyrune JL, De Vos J, Klein B. APRIL is overexpressed in cancer: link with tumor progression. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Munari F, Lonardi S, Cassatella MA, Doglioni C, Cangi MG, Amedei A, Facchetti F, Eishi Y, Rugge M, Fassan M, de Bernard M, D'Elios MM, Vermi W. Tumor-associated macrophages as major source of APRIL in gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:6612-6616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pelekanou V, Notas G, Theodoropoulou K, Kampa M, Takos D, Alexaki VI, Radojicic J, Sofras F, Tsapis A, Stathopoulos EN, Castanas E. Detection of the TNFSF members BAFF, APRIL, TWEAK and their receptors in normal kidney and renal cell carcinomas. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2011;34:49-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang F, Chen L, Ding W, Wang G, Wu Y, Wang J, Luo L, Cong H, Wang Y, Ju S, Shao J, Wang H. Serum APRIL, a potential tumor marker in pancreatic cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:1715-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Petty RD, Samuel LM, Murray GI, MacDonald G, O'Kelly T, Loudon M, Binnie N, Aly E, McKinlay A, Wang W, Gilbert F, Semple S, Collie-Duguid ES. APRIL is a novel clinical chemo-resistance biomarker in colorectal adenocarcinoma identified by gene expression profiling. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang F, Ding W, Wang J, Jing R, Wang X, Cong H, Wang Y, Ju S, Wang H. Identification of microRNA-target interaction in APRIL-knockdown colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011;18:500-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang F, Chen L, Ni H, Wang G, Ding W, Cong H, Ju S, Yang S, Wang H. APRIL depletion induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through blocking TGF-β1/ERK signaling pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;383:179-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao Q, Li Q, Xue Z, Wu P, Yang X. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a humanized anti-APRIL antibody. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:464-465. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bonci D, Musumeci M, Coppola V, Addario A, Conticello C, Hahne M, Gulisano M, Grignani F, De Maria R. Blocking the APRIL circuit enhances acute myeloid leukemia cell chemosensitivity. Haematologica. 2008;93:1899-1902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | He S, Li L, Jin R, Lu X. Biological Function of Pin1 in Vivo and Its Inhibitors for Preclinical Study: Early Development, Current Strategies, and Future Directions. J Med Chem. 2023;66:9251-9277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu W, Xue X, Chen Y, Zheng N, Wang J. Targeting prolyl isomerase Pin1 as a promising strategy to overcome resistance to cancer therapies. Pharmacol Res. 2022;184:106456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim MR, Choi HK, Cho KB, Kim HS, Kang KW. Involvement of Pin1 induction in epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1834-1841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pang R, Yuen J, Yuen MF, Lai CL, Lee TK, Man K, Poon RT, Fan ST, Wong CM, Ng IO, Kwong YL, Tse E. PIN1 overexpression and beta-catenin gene mutations are distinct oncogenic events in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:4182-4186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ryo A, Nakamura M, Wulf G, Liou YC, Lu KP. Pin1 regulates turnover and subcellular localization of beta-catenin by inhibiting its interaction with APC. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lu KP, Zhou XZ. The prolyl isomerase PIN1: a pivotal new twist in phosphorylation signalling and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:904-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Aoyama S, Kido Y, Kanamoto M, Naito M, Nakanishi M, Kanna M, Yamamotoya T, Asano T, Nakatsu Y. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 promotes extracellular matrix production in hepatic stellate cells through regulating formation of the Smad3-TAZ complex. Exp Cell Res. 2023;425:113544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lufei C, Koh TH, Uchida T, Cao X. Pin1 is required for the Ser727 phosphorylation-dependent Stat3 activity. Oncogene. 2007;26:7656-7664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nakada S, Kuboki S, Nojima H, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Takayashiki T, Takano S, Miyazaki M, Ohtsuka M. Roles of Pin1 as a Key Molecule for EMT Induction by Activation of STAT3 and NF-κB in Human Gallbladder Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:907-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Longley DB, Johnston PG. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. J Pathol. 2005;205:275-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 966] [Cited by in RCA: 1162] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Van der Jeught K, Xu HC, Li YJ, Lu XB, Ji G. Drug resistance and new therapies in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3834-3848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 27. | Novoa Díaz MB, Carriere P, Gentili C. How the interplay among the tumor microenvironment and the gut microbiota influences the stemness of colorectal cancer cells. World J Stem Cells. 2023;15:281-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yang L, Li N, Xue Z, Liu LR, Li J, Huang X, Xie X, Zou Y, Tang H, Xie X. Synergistic therapeutic effect of combined PDGFR and SGK1 inhibition in metastasis-initiating cells of breast cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:2066-2080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liu C, Zhang Y, Gao J, Zhang Q, Sun L, Ma Q, Qiao X, Li X, Liu J, Bu J, Zhang Z, Han L, Zhao D, Yang Y. A highly potent small-molecule antagonist of exportin-1 selectively eliminates CD44(+)CD24(-) enriched breast cancer stem-like cells. Drug Resist Updat. 2023;66:100903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xie J, Zheng Z, Tuo L, Deng X, Tang H, Peng C, Zou Y. Recent advances in exosome-based immunotherapy applied to cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1296857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lin S, Li K, Qi L. Cancer stem cells in brain tumors: From origin to clinical implications. MedComm (2020). 2023;4:e341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liao Y, Zhang Z, Ouyang L, Mi B, Liu G. Engineered Extracellular Vesicles in Wound Healing: Design, Paradigms, and Clinical Application. Small. 2024;20:e2307058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nair S, Ormazabal V, Carrion F, Handberg A, McIntyre HD, Salomon C. Extracellular vesicle-mediated targeting strategies for long-term health benefits in gestational diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond). 2023;137:1311-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ding JY, Chen MJ, Wu LF, Shu GF, Fang SJ, Li ZY, Chu XR, Li XK, Wang ZG, Ji JS. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in skin wound healing: roles, opportunities and challenges. Mil Med Res. 2023;10:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang S, Du C, Li G. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: emerging concepts in the treatment of spinal cord injury. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:4425-4438. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Zhang X, Wang C, Yu J, Bu J, Ai F, Wang Y, Lin J, Zhu X. Extracellular vesicles in the treatment and diagnosis of breast cancer: a status update. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1202493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bhujel B, Oh SH, Kim CM, Yoon YJ, Kim YJ, Chung HS, Ye EA, Lee H, Kim JY. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for Corneal Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kumar SK, Sasidhar MV. Recent Trends in the Use of Small Extracellular Vesicles as Optimal Drug Delivery Vehicles in Oncology. Mol Pharm. 2023;20:3829-3842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shen J, Cao J, Chen M, Zhang Y. Recent advances in the role of exosomes in liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:1083-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/