Published online Sep 26, 2023. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v15.i9.931

Peer-review started: May 31, 2023

First decision: June 14, 2023

Revised: June 22, 2023

Accepted: August 23, 2023

Article in press: August 23, 2023

Published online: September 26, 2023

Processing time: 116 Days and 15.6 Hours

Umbilical cord (UC) mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation is a potential therapeutic intervention for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Integrin beta 3 (ITGB3) promotes cell migration in several cell types. However, whether ITGB-modified MSCs can migrate to plaque sites in vivo and play an anti-atherosclerotic role remains unclear.

To investigate whether ITGB3-overexpressing MSCs (MSCsITGB3) would exhibit improved homing efficacy in atherosclerosis.

UC MSCs were isolated and expanded. Lentiviral vectors encoding ITGB3 or green fluorescent protein (GFP) as control were transfected into MSCs. Sixty male apolipoprotein E-/- mice were acquired from Beijing Vital River Lab Animal Technology Co., Ltd and fed with a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 wk to induce the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. These HFD-fed mice were randomly separated into three clusters. GFP-labeled MSCs (MSCsGFP) or MSCsITGB3 were transplanted into the mice intravenously via the tail vein. Immunofluorescence staining, Oil red O staining, histological analyses, western blotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction were used for the analyses.

ITGB3 modified MSCs successfully differentiated into the “osteocyte” and “adipocyte” phenotypes and were characterized by positive expression (> 91.3%) of CD29, CD73, and CD105 and negative expression (< 1.35%) of CD34 and Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR. In a transwell assay, MSCsITGB3 showed significantly faster migration than MSCsGFP. ITGB3 overexpression had no effects on MSC viability, differentiation, and secretion. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that ITGB3 overexpression substantially enhanced the homing of MSCs to plaque sites. Oil red O staining and histological analyses further confirmed the therapeutic effects of MSCsITGB3, significantly reducing the plaque area. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction revealed that MSCITGB3 transplantation considerably decreased the inflammatory response in pathological tissues by improving the dynamic equilibrium of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

These results showed that ITGB3 overexpression enhanced the MSC homing ability, providing a potential approach for MSC delivery to plaque sites, thereby optimizing their therapeutic effects.

Core Tip: Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation is considered a new treatment for atherosclerosis. However, research regarding homing of MSCs to atherosclerotic lesions is insufficient. Here, we transplanted integrin beta 3 (ITGB3)-overexpressing MSCs into a mouse model of atherosclerosis. ITGB3-overexpressing MSCs were more greatly accumulated in atherosclerotic plaques. These MSCs prevented plaque progression by shifting the local cytokine profile. The use of ITGB3-overexpressing MSCs may be a novel tool to treat atherosclerosis.

- Citation: Hu HJ, Xiao XR, Li T, Liu DM, Geng X, Han M, Cui W. Integrin beta 3-overexpressing mesenchymal stromal cells display enhanced homing and can reduce atherosclerotic plaque. World J Stem Cells 2023; 15(9): 931-946

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v15/i9/931.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v15.i9.931

Atherosclerosis is a serious public health problem and the most commonly diagnosed cardiovascular disease in the general population[1]. Implementing early detection of atherosclerosis[2] with systemic pharmacological treatments[3] and percutaneous coronary intervention[4] has contributed to substantial progress in the treatment of atherosclerosis-related diseases[5,6]. Despite medical improvements, the incidence of atherosclerosis-related diseases remains high[7]. Atherosclerotic plaques are still associated with high mortality rates in patients with high-risk or visible advanced plaque disease. Therefore, more studies are needed to discover and explore effective molecules and targets for treatments.

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation accomplished improvements in experimental studies of atherosclerosis[8-11]. MSCs have the ability to secrete many cytokines that mitigate vascular inflammation and regulate the local microenvironment owing to the effects of their secreted anti-inflammatory factors within the vascular plaque[12-14]. However, some limitations preclude the translation of stem cell therapy into clinical applications[15,16], such as stem cells accurately homing to plaques. To determine this, we need to understand the specific mechanisms that underlie the migration and adhesion of MSCs under physiological and pathological conditions. Some studies have attempted to genetically decorate MSCs with specific receptors required for efficient homing. For example, Shahror et al[17] found that overexpression of fibroblast growth factor 21 considerably increased MSC migration to and adhesion in the injured brain tissue. Moreover, overexpression of C-X-C chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5) increased the migratory capability of MSCs toward CXCL13, which changed most substantially in animal models of contact allergy, accompanied by decreases in inflammatory cellular infiltration and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine production[18]. It is well established that damaged tissues release specific types of cytokines and chemokines. Therefore, elucidating the interrelationships between tissue-specific chemokines and matching receptors on MSCs could offer novel ways of promoting homing and treatment effects of these cells.

The integrin family of receptors, a major family of migration-promoting receptors, plays an important role in the crosstalk between cells and their surroundings[19,20]. Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) site-containing proteins and corresponding integrin receptors constitute the primary recognition system for cell adhesion[21,22]. Many inflammatory cytokines, such as intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), osteopontin (OPN), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), contain an RGD motif in their structure[23,24]. The primary sequence of integrin beta 3 (ITGB3), a well-preserved region in all integrin beta subunits, has been called the RGD crosslinking region[25]. Based on this information, we genetically modified MSCs using ex vivo lentiviral transduction to overexpress ITGB3. In the current study, we first demonstrated that ITGB3-overexpressing MSCs (MSCsITGB3) showed enhanced chemotaxis toward plaque tissues in vivo and inflammatory cells in vitro. Compared with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled MSCs (MSCsGFP), MSCsITGB3 reduced the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in homozygous apolipoprotein-E (ApoE)-/- mice, suggesting that ITGB3 enhances homing of modified stem cells to plaque tissue, thereby promoting their therapeutic efficacy in the ApoE-/- mouse model of atherosclerosis.

Human umbilical cord (UC) samples were collected from three healthy donors. All the donors provided written informed consent. MSCs were isolated and cultured from the UCs as reported previously[26]. Briefly, the UC tissue was collected from healthy pregnant women undergoing labor. After removing the UC tissue's arteries and veins, the remaining Wharton's jelly was cut into small pieces for patch cultures. The tissue fragments were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in mesenchymal stem cell medium (MSC medium; Sciencell, Carlsbad, CA, United States) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), stem cell growth supplements, penicillin, and streptomycin. After 10-15 d, fibroblast-like MSCs migrated out of the tissue patches. The studies involving pregnant participants were reviewed and approved by The Ethical Committee of The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (approval number: 2021-R496).

The murine macrophage cell line Raw264.7 was purchased from the Cell Resource Center of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). Vascular smooth muscle cells were isolated from mouse aortas and cultured in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% FBS. Lung primary microvascular endothelial cells were obtained from the lungs of 4-week-old C57 mice through two series of immunoselection with CD31- and CD102-conjugated magnetic beads using a previously described procedure[27] and subsequently cultured in endothelial cell medium containing 5% FBS and endothelial cell growth supplements.

Lentiviral vector (LV) encoding ITGB3 and GFP as control were generated and packaged by Hanbio Biosciences (Shanghai, China). All LVs were used for MSC transfection with an infection multiplicity of 30-40. MSCs were plated at a density of 3-5 × 105 cells/cm2 in each six-well plate, depending on the subsequent use. When MSCs reached 40%-50% confluence, the transfection was performed in the presence of polybrene (Cyagen Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Following transfection for 72 h, the transfection effectiveness of the virus was checked through fluorescent staining.

ApoE-/- mice (7–8-week-old) were acquired from Beijing Vital River Lab Animal Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Sixty male ApoE-/- mice were housed in Hebei Medical University and fed with standard chow and drinking water for 1 wk to adapt to the new surroundings. Then, all animals were fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 wk to induce the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. These HFD-fed mice were randomly separated into three clusters and received the following treatment: (1) HFD mice (n = 20) were injected 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the caudal vein every week from week 9, four times in total; (2) MSCGFP mice (n = 20) receiving 200 μL of PBS containing 1 × 106 MSCsGFP intravenously through the tail vein every week from week 9; and (3) MSCITGB3 mice (n = 20) receiving 200 μL of PBS containing 1 × 106 MSCsITGB3 intravenously through the tail vein every week from week 9. The animals were euthanized after 12 wk of HFD, the aorta and aortic sinus were collected, and histological samples were processed for subsequent atherosclerosis assessment. At the same time, blood samples were collected to determine lipid levels. All animal procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care Committee of The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No. 2021-R496).

At the end of week 12, 10 mice were gas-anesthetized via a facemask and kept on a minimal dose of isoflurane (1.0%-2.0%). The mice were placed in a supine position and maintained spontaneous breathing with isoflurane insufflation throughout the echocardiographic assessment. Echocardiographic data were recorded by a VisualSonics Vevo2100 Imaging System (Fujifilm Visual Sonics Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with an EZ-SA800 Single Animal System (E-Z Systems Inc., Bethlehem, PA, United States). Ascending aorta functions were evaluated from the parasternal view of the long axis. The diameter of the systolic aorta was measured at the peak anterior movement point of the ascending aorta, and the diameter of the diastolic aorta was measured using a Q-wave (end-diastolic) echocardiogram. The average diameter measurements of five consecutive heart cycles were selected for data analysis. Meanwhile, left ventricle function and heart chamber dimensions were also evaluated, including the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) and left ventricular fractional shortening (FS), using accompanying software. The data were recorded and analyzed.

Murine aortic rings were cultured as described previously[28]. Briefly, after 12 wk of HFD, external organs and tissues were removed. Then, the whole aortic vessel was separated from the adipose and surrounding tissue. The aorta was divided into 2-4 mm rings and cultured in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 5% FBS. Aortic rings were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 24 h for further experiments.

The aortic arch and aortic valve were harvested after 12 wk of HFD. The animals were euthanized, and the left ventricles were cannulated and injected with PBS containing heparin. Thereafter, the aortic arch and aortic valve were separated, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, shortly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and sliced. Subsequently, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was performed to assess plaque size. The cross-sectional areas of the plaque were measured with Image-Pro Plus (IPP) 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Corp., Rockville, MD, United States). Collagen depositions were assessed using Masson's trichrome staining. Average values were determined from at least three sections in each sample.

For oil red O (ORO) staining, the fixed whole aorta was incubated with 0.3% ORO solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) for 20 min and, then, washed with 60% isopropanol. Frozen aortic arch and aortic valve sections were incubated with ORO for 5 min, washed with PBS, and counterstained with hematoxylin. The atherosclerotic lesions were photographed using a light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and quantified using IPP 6.0 software.

The effects of LV transfection on MSC viability were evaluated using cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8) assays as described previously[29]. Briefly, MSCs, MSCsITGB3, and MSCsGFP were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well, respectively. After 24 h, CCK-8 was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a VersaMax (Ocean Springs, MI, United States) microplate scanner.

Chemotaxis assays were operated in 24-well transmembrane chambers with 8-µm pore filters. To test the ability of stem cells to migrate toward defined chemokines, Raw264.7, vascular smooth muscle cells, and primary microvascular endothelial cells were separately seeded into the lower chamber (1 × 105 cells/well). After achieving confluence, serum-free cells were stimulated with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, 20 ng/mL) for 24 h. Then MSCs, MSCsGFP, and MSCsITGB3 were respectively plated into the upper chamber at 2 × 104 cells/well. After incubation for 24 h, the upper layer of cells was removed, and the lower layer was stained with crystal violet.

For the vascular atherosclerotic plaque, mice were sacrificed after week 12. Aortic rings were separately cultured for 24 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 5% FBS. Next, MSCs, MSCsGFP, and MSCsITGB3 were respectively plated into the upper chamber at 2 × 104 cells/well. The medium for re-suspending MSCs matched the medium in the lower chamber. After incubation for 24 h, non-migrated cells were removed from the upper surface, and the cells that had migrated across the membrane to the lower surface were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. For each membrane, five fields of view were imaged and analyzed. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and the number of migrated cells was expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of total cell counts per field.

Total RNA of cells or tissue samples was extracted using TRIzol reagent, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using the M-MLV First Strand Kit. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix were performed using an ABI 7500. qRT-PCR analyses were repeated at least three times. The qRT-PCR data were standardized to β-actin expression, using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The average threshold cycle for each gene was determined from at least three independent experiments.

Cell or tissue lysates were extracted with lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature, incubated with specific antibodies against VCAM-1, ICAM-1, OPN, and GAPDH at 4 °C overnight, and, then, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G for 1 h at room temperature. Antigen-antibody complexes were assessed using the GE ImageQuant™ LAS 4000 detection system (GE Healthcare Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The protein bands of interest were quantified with IPP 6.0 software.

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States). Data are displayed as mean ± SEMs, and each independent experiment was repeated three times. The statistical significance of differences between two groups was determined using the unpaired Student’s t-test, and comparisons of more than two groups were performed using a one-way analysis of variance. For all statistical comparisons, significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arteries with high expression of adherence molecules. We tested the expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and OPN because studies have shown that they contain the RGD motif that can bind to the ITGB3 receptor[19,20,30]. Our results demonstrated that the protein expression levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and OPN were six to eight times higher in atherosclerotic than in control blood vessels (Figure 1A). Similarly, qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence staining also confirmed that the three adhesion factors considerably increased at sites of inflammation (Figure 1B–D).

Inflammatory factors that are highly expressed at plaque sites and matching receptors expressed on the surface of MSCs play an important role in guiding stem cells. Thus, we analyzed the expression of the ITGB3 receptor using western blot, qRT-PCR, and fluorescence staining methods. First, human MSCs at the third passage had very low expression of the ITGB3 receptor at the protein and mRNA levels (Figure 2A and B). Second, immunofluorescence staining confirmed that MSCs barely expressed the ITGB3 receptor (Figure 2C and D). To further determine whether overexpression of ITGB3 receptor in MSCs can promote their homing capability toward plaque tissues, MSCs were transfected with LVs encoding ITGB3 and GFP (MSCsITGB3 for short) or GFP (MSCsGFP for short). We found that both MSCsITGB3 and MSCsGFP highly expressed GFP, confirming the stable expression of the GFP reporter gene (Figure 2C). In contrast to MSCsGFP and MSCs, MSCsITGB3 showed substantially stronger expression of ITGB3 at the protein, mRNA, and fluorescence staining levels (Figure 2A–D). Moreover, ITGB3 overexpression did not affect stem cell viability according to CCK8 analyses (Figure 2E). To further verify whether transfection of ITGB3 affects the differentiation properties of MSCs, we observed several typical stem cell markers using flow cytometry and qRT-PCR analyses. The results showed that in MSCsITGB3, MSC-specific markers (CD73, CD105, and CD29), but not hemopoietic stem cell antigens (CD34 and human leukocyte antigen-DR), were highly expressed (Figure 2F and G). The differentiation of MSCsITGB3 into adipocytes and osteoblasts was separately evaluated using ORO and Alizarin red staining (Figure 2H and I). Moreover, marker genes in induced adipocytes and osteoblasts were verified through qRT-PCR (Figure 2J and K). These findings confirmed that transfected MSCs still have stem cell properties.

ITGB3 is vital for cell migration, adhesion, and invasion[20-22,31]. Therefore, we next checked whether MSCsITGB3 could promote MSC migration in vitro and in vivo. The in vitro cell chemotaxis assay showed that in the presence of TNF-α, MSCsITGB3 displayed a significantly increased migration toward the bottom chamber, especially if it contained macrophages (Figure 3A and B). However, in the absence of TNF-α, all cells showed similar, very low, nonspecific migration toward the lower, cell-containing chamber (Figure 3A and B). We also performed transwell-based chemotaxis assays using atherosclerotic aorta samples in vitro (Figure 3C and D). MSCsITGB3 had the highest migratory activity, indicating that the atherosclerotic plaque secreted inflammatory factors which were chemoattractants for MSCsITGB3, but not for MSCsGFP (Figure 3C and D). Next, we observed whether MSCs migrate to plaque sites in vivo following intra

To explore the effects of MSCsITGB3 on the progression of atherosclerosis, the whole aorta, aortic root, and aortic arch were stained with 0.5% ORO, and the stained areas were quantified to determine the atherosclerotic plaque area. The stained area in the aorta was substantially decreased in the MSCITGB3 group when compared with that of the HFD and MSCGFP groups (Figure 4A and B). The stained areas in the aortic root and aortic arch decreased in the MSCITGB3 group compared with the corresponding in the HFD and MSCGFP groups (Figure 4C). HE and Masson's trichrome staining analyses of sections taken from the aortic root and aortic arch demonstrated that MSCsITGB3 inhibited aortic plaque formation and collagen deposition more effectively than MSCsGFP (Figure 4D and E). Aortic stiffness is the earliest detectable evidence of changes in arterial wall function. Echocardiographic results showed that both systolic and diastolic diameters were considerably increased while the vessel wall thickness was decreased in the MSCITGB3 group (Figure 4F). However, left ventricular EF and FS were not different among the three groups (Supplementary Figure 2). The number of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques at the aortic arch was determined by F4/80 staining. The F4/80 staining-positive areas were notably reduced in the MSCITGB3 group compared with the HFD group (Figure 4G).

To evaluate the effects of MSCsITGB3 on biochemical features in vivo, we recorded changes in mouse body weight and measured blood lipid concentrations. The results showed that the body weight did not vary among the three groups during the experiment (Supplementary Figure 3A). Plasma lipid analyses, including those measuring total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, were performed on terminal blood samples obtained by cardiac puncture but showed no statistical differences among the HFD, MSCGFP, and MSCITGB3 groups (Supplementary Figure 3B). These results suggest that intravenous injection of stem cells did not interfere with lipid metabolism in mice receiving an HFD.

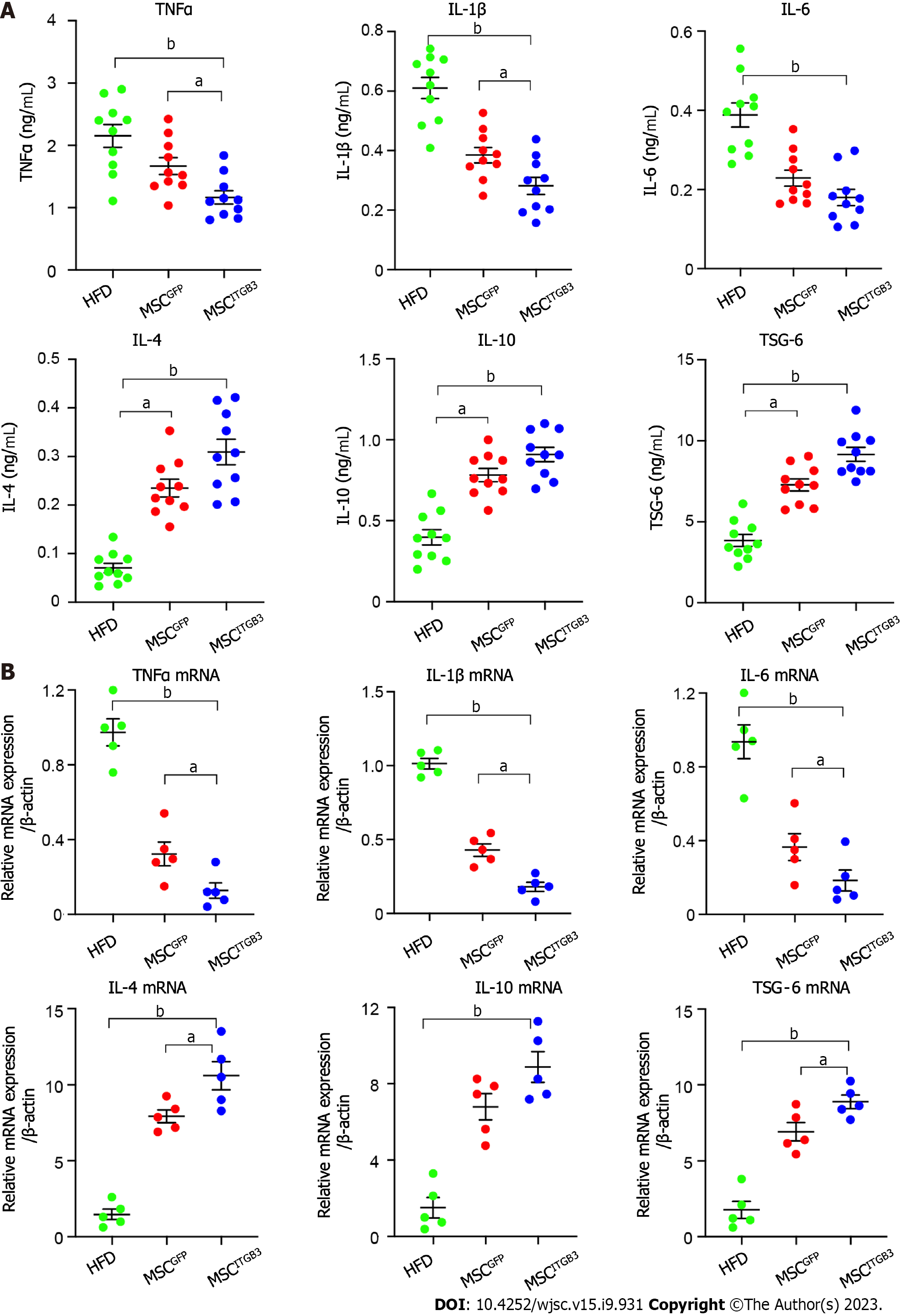

The levels of inflammatory factors are positively correlated with the degree of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Cytokines play a pivotal role in chronic inflammatory diseases[31]. They affect the expression of adherence molecules, permeability of endothelial cell, as well as proliferation and migration of inherent cells in blood vessels, all of which are associated with atherosclerosis. Interleukin (IL)-1β, an established driver of atherosclerotic disease[32], is involved in the entire process of atherosclerotic lesion progression[33]. Advanced atherosclerotic plaques can be alleviated and stabilized through IL-1β inhibition. After observing that MSCITGB3 treatment can reduce the plaque area, we further investigated whether MSCITGB3 infusion can decrease the levels of pro-inflammatory factors or increase the levels of anti-inflammatory factors in the serum and aorta tissue. Our results showed that pro-inflammatory factors, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, showed a significant downward trend in mice who had received MSCITGB3 or MSCGFP treatment. However, the treatment effect of MSCsITGB3 was more pronounced than that of MSCsGFP. Likewise, mice receiving MSCsITGB3 or MSCsGFP showed significantly increased levels of anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-4, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 in the serum and aorta tissue (Figure 5). These results indicate that MSCITGB3 treatment primarily reduces pathological inflammatory responses by improving the balance between secreted pro- and anti-inflammatory factors.

In this study, adhesion molecules containing the RGD motif were highly expressed in an atherosclerosis model, and transfection of ITGB3 into MSCs improved their targeting capability. As expected, intravenous injection of MSCsITGB3 substantially reduced atherosclerotic plaque in the ApoE-/- HFD mouse model.

Owing to their adaptive immunomodulatory properties and superior secretory potential, MSCs have attracted extensive attention in the treatment of atherosclerotic diseases[8,14]. The route of MSC administration is critical for their therapeutic efficiency, and systemic delivery via intravenous infusion is the primary approach for many cell therapies. However, several problems occur with this approach, and one of the major hurdles is insufficient cell engraftment into the damaged tissue[34]. It is well known that the therapeutic level of MSCs mainly depends on intercellular interactions and their regulation by the local microenvironment. Therefore, the therapeutic effect of intravenously injected MSCs may be closely related to their localization. It is predicted that the effectiveness of cell therapy can be improved by increasing local recruitment, further promoting tissue repair. However, methods to increase intercellular interactions that promote local engraftment of MSCs remain unclear.

Integrins, as transmembrane receptors, mediate cell connections by integrating Ig superfamily counterreceptors (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) on adjacent cells[20]. Adhesion molecules and integrin receptors have been identified to facilitate cell migration toward target organs and adhesion in target tissues. Therefore, intravenous injection of MSCsITGB3 may provide a new approach to improve stem cell homing. Previous studies have also verified that MSCs with altered chemokine receptors, such as CXCR5[18], integrin α4[35], and CCR5 and CXCR6[36], significantly increased cell motion to lesion sites and enhanced the therapeutic effect of MSCs. MSC homing to a target organ requires the proper integration of interactions of chemokines secreted by injured tissue and adhesion molecules with matching receptors on MSCs. Therefore, determining disease-specific ligand expression profiles will provide the precise signal necessary for MSC homing. In our study, we elucidated that the ITGB3/RGD motif axis is a specific regulator for MSC homing in atherosclerosis. Adhesion molecules containing the RGD motif, such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and OPN, are highly expressed in atherosclerotic plaque and are involved in a variety of immune functions, including T cell activation, migration, and extravasation[37]. High VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression levels have also been reported in the inflamed tissue, including vascular plaque[38]. We found that the RGD structure acts as an important feature of the plaque tissue that chemoattracts the migration of MSCsITGB3 to lesions in vivo. Moreover, our findings demonstrated that the ITGB3-RGD motif axis is the atherosclerosis-specific regulator for MSC homing. Factors containing RGD structures can be observed in various inflammatory tissues, including the site of atherosclerotic lesions[39]. However, the expression of ITGB3 was almost absent on the surface of MSCs. Thus, MSCsITGB3 may serve as a disease-specific therapeutic tool to improve MSC homing when treating atherosclerosis. MSC transplantation and homing appear to improve atherosclerosis via different mechanisms. There is a substantial amount of evidence indicating that transplanted MSCs primarily promote local microenvironmental improvement through their paracrine secretory effects[40-42]. The anti-inflammatory cytokines secreted by MSCs can reduce inflammation and modulate immune response while enhancing normal cell survival and differentiation[9,11]. It has also been documented that the anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs are primarily mediated by extracellular vesicles (EVs)[8,43]. Various disease models, such as those involving endothelial cell senescence[44], autoimmune diseases[45], arterial stiffness and hypertension[46], and lung injury[47], have demonstrated that EVs derived from MSCs can mitigate cell death, prevent apoptosis, and enhance recovery. In this regard, as a result of the continuous release of EVs in the vicinity of the damage site, transplantation of MSCs overexpressing ITGB3 with improved migratory capability could play a more effective role in treating atherosclerotic disease.

A previous study found that ITGB3 stimulated the progression of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via activation of the STAT3 pathway[48]. Furthermore, ITGB3 promoted cell senescence and profibrotic changes through p53 signaling activation and secretion of transforming growth factor beta in cultured tubular cells[49]. However, these studies have not examined the specific effect of ITGB3 overexpression on MSC migration and homing in vivo. Further research is necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of how overexpression of ITGB3 intensifies homing abilities of MSCs.

This study has certain limitations. First, the MSCsITGB3 were generated by lentiviral infection. As lentiviral vectors can randomly integrate into the genome resulting in deleterious mutations, their therapeutic application in humans is limited by an inherent risk of tumorigenesis. Second, other suitable methods are needed to increase the expression of ITGB3. Third, the current experiment did not specifically investigate the survival time of MSCsITGB3in vivo. The next step will be to trace the target location and lifespan of MSCsITGB3 through in vivo imaging technology.

Collectively, we genetically modified MSCs in vitro and found that ITGB3 overexpression substantially upregulated MSC migration, aggregation in plaque sites, and immunomodulatory properties of MSCs in vivo. Although the therapeutic potential of modified MSCs in atherosclerosis has not yet been translated into clinical practice, our work improves our understanding of the adhesion molecule–integrin receptor axis, as well as of stem cell features, and may provide novel insights into the rapid and targeted delivery of MSCs to disease sites, thereby optimizing their therapeutic effects.

Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation is a potential therapeutic intervention for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Integrin beta 3 (ITGB3) promotes cell migration in several cell types. However, whether ITGB3-modified MSCs can migrate to plaque sites in vivo and play an anti-atherosclerotic role remains unclear.

Atherosclerosis is a serious public health problem and more treatment options are needed to explore and identify effective molecules and targets.

The objective of our study was to evaluate the chemotaxis ability of ITGB3-overexpressing MSCs toward inflammatory cells in vitro and plaque tissues in vivo, promoting their therapeutic efficacy in the atherosclerosis mouse model.

Umbilical cord MSCs were isolated and expanded. Lentiviral vectors encoding ITGB3 or green fluorescent protein (GFP) as control were transfected into MSCs. Male apolipoprotein E-/- mice were fed with a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 wk to induce the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. The HFD-fed mice were randomly separated into three clusters. GFP-labeled MSCs (MSCsGFP) or MSCsITGB3 were transplanted into the mice intravenously via the tail vein. Immunofluorescence staining, Oil red O staining, histological analyses, western blotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction were used for the analyses. Statistical evaluation between two groups was determined using the unpaired Student’s t-test, and comparisons of more than two groups were performed using a one-way analysis of variance.

MSCsITGB3 successfully differentiated into the “osteocyte” and “adipocyte” phenotypes and were characterized by positive expression (> 91.3%) of CD29, CD73, and CD105 and negative expression (< 1.35%) of CD34 and human leukocyte antigen-DR. MSCsITGB3 showed significantly faster migration than MSCsGFP. ITGB3 overexpression had no effects on MSC viability, differentiation, and secretion. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that ITGB3 overexpression substantially enhanced the homing of MSCs to plaque sites. Oil red O staining and histological analyses further confirmed the therapeutic effects of MSCsITGB3, significantly reducing the plaque area. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction revealed that MSCITGB3 transplantation considerably decreased the inflammatory response in pathological tissues by improving the dynamic equilibrium of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

The study demonstrated that ITGB3 overexpression enhanced the MSC homing ability, providing a potential approach for MSC delivery to plaque sites, thereby optimizing their therapeutic effects.

The ITGB3-modified MSCs can migrate the plaque sites and play an anti-inflammation role, which may be an effective strategy to treat vascular atherosclerotic related diseases.

| 1. | Mäkinen PI, Ylä-Herttuala S. Therapeutic gene targeting approaches for the treatment of dyslipidemias and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:116-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jenkins A, Januszewski A, O'Neal D. The early detection of atherosclerosis in type 1 diabetes: why, how and what to do about it. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2019;8:14-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gragnano F, Calabrò P. Role of dual lipid-lowering therapy in coronary atherosclerosis regression: Evidence from recent studies. Atherosclerosis. 2018;269:219-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Prpic R, Teirstein PS, Reilly JP, Moses JW, Tripuraneni P, Lansky AJ, Giorgianni JA, Jani S, Wong SC, Fish RD, Ellis S, Holmes DR, Kereiakas D, Kuntz RE, Leon MB. Long-term outcome of patients treated with repeat percutaneous coronary intervention after failure of gamma-brachytherapy for the treatment of in-stent restenosis. Circulation. 2002;106:2340-2345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | He L, Zhao R, Wang Y, Liu H, Wang X. Research Progress on Catalpol as Treatment for Atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:716125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tang J, Rakshit M, Chua HM, Darwitan A, Nguyen LTH, Muktabar A, Venkatraman S, Ng KW. Liposome interaction with macrophages and foam cells for atherosclerosis treatment: effects of size, surface charge and lipid composition. Nanotechnology. 2021;32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kobiyama K, Ley K. Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2018;123:1118-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 60.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takafuji Y, Hori M, Mizuno T, Harada-Shiba M. Humoral factors secreted from adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate atherosclerosis in Ldlr-/- mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115:1041-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang X, Huang F, Li W, Dang JL, Yuan J, Wang J, Zeng DL, Sun CX, Liu YY, Ao Q, Tan H, Su W, Qian X, Olsen N, Zheng SG. Human Gingiva-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Modulate Monocytes/Macrophages and Alleviate Atherosclerosis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Golpanian S, Wolf A, Hatzistergos KE, Hare JM. Rebuilding the Damaged Heart: Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Cell-Based Therapy, and Engineered Heart Tissue. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:1127-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li Q, Sun W, Wang X, Zhang K, Xi W, Gao P. Skin-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Atherosclerosis via Modulating Macrophage Function. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1294-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Colmegna I, Stochaj U. MSC - targets for atherosclerosis therapy. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;11:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang W, Yin R, Zhu X, Yang S, Wang J, Zhou Z, Pan X, Ma A. Mesenchymal stem-cell-derived exosomal miR-145 inhibits atherosclerosis by targeting JAM-A. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;23:119-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lin Y, Zhu W, Chen X. The involving progress of MSCs based therapy in atherosclerosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barbash IM, Chouraqui P, Baron J, Feinberg MS, Etzion S, Tessone A, Miller L, Guetta E, Zipori D, Kedes LH, Kloner RA, Leor J. Systemic delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted myocardium: feasibility, cell migration, and body distribution. Circulation. 2003;108:863-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 916] [Cited by in RCA: 903] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin P, Correa D, Kean TJ, Awadallah A, Dennis JE, Caplan AI. Serial transplantation and long-term engraftment of intra-arterially delivered clonally derived mesenchymal stem cells to injured bone marrow. Mol Ther. 2014;22:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shahror RA, Ali AAA, Wu CC, Chiang YH, Chen KY. Enhanced Homing of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 to Injury Site in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang X, Huang W, Chen X, Lian Y, Wang J, Cai C, Huang L, Wang T, Ren J, Xiang AP. CXCR5-Overexpressing Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Exhibit Enhanced Homing and Can Decrease Contact Hypersensitivity. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1434-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6323] [Cited by in RCA: 6691] [Article Influence: 278.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ross TD, Coon BG, Yun S, Baeyens N, Tanaka K, Ouyang M, Schwartz MA. Integrins in mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:613-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | D'Souza SE, Ginsberg MH, Burke TA, Lam SC, Plow EF. Localization of an Arg-Gly-Asp recognition site within an integrin adhesion receptor. Science. 1988;242:91-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | D'Souza SE, Ginsberg MH, Matsueda GR, Plow EF. A discrete sequence in a platelet integrin is involved in ligand recognition. Nature. 1991;350:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dashdulam D, Kim ID, Lee H, Lee HK, Kim SW, Lee JK. Osteopontin heptamer peptide containing the RGD motif enhances the phagocytic function of microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;524:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang JH, Stehle T, Pepinsky B, Liu JH, Karpusas M, Osborn L. Structure of a functional fragment of VCAM-1 refined at 1.9 a resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1996;52:369-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | D'Souza SE, Haas TA, Piotrowicz RS, Byers-Ward V, McGrath DE, Soule HR, Cierniewski C, Plow EF, Smith JW. Ligand and cation binding are dual functions of a discrete segment of the integrin beta 3 subunit: cation displacement is involved in ligand binding. Cell. 1994;79:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Han YF, Tao R, Sun TJ, Chai JK, Xu G, Liu J. Optimization of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell isolation and culture methods. Cytotechnology. 2013;65:819-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nie L, Guo X, Esmailzadeh L, Zhang J, Asadi A, Collinge M, Li X, Kim JD, Woolls M, Jin SW, Dubrac A, Eichmann A, Simons M, Bender JR, Sadeghi MM. Transmembrane protein ESDN promotes endothelial VEGF signaling and regulates angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5082-5097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sonou T, Ohya M, Yashiro M, Masumoto A, Nakashima Y, Ito T, Mima T, Negi S, Kimura-Suda H, Shigematsu T. Mineral Composition of Phosphate-Induced Calcification in a Rat Aortic Tissue Culture Model. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22:1197-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang D, Tian L, Wang Y, Gao X, Tang H, Ge J. Circ_0001206 regulates miR-665/CRKL axis to alleviate hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury in myocardial infarction. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9:998-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Barry ST, Ludbrook SB, Murrison E, Horgan CM. Analysis of the alpha4beta1 integrin-osteopontin interaction. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:342-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Warnatsch A, Ioannou M, Wang Q, Papayannopoulos V. Inflammation. Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science. 2015;349:316-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 678] [Cited by in RCA: 1015] [Article Influence: 92.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vromman A, Ruvkun V, Shvartz E, Wojtkiewicz G, Santos Masson G, Tesmenitsky Y, Folco E, Gram H, Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Sukhova GK, Libby P. Stage-dependent differential effects of interleukin-1 isoforms on experimental atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2482-2491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Libby P. Interleukin-1 Beta as a Target for Atherosclerosis Therapy: Biological Basis of CANTOS and Beyond. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2278-2289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 56.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nystedt J, Anderson H, Tikkanen J, Pietilä M, Hirvonen T, Takalo R, Heiskanen A, Satomaa T, Natunen S, Lehtonen S, Hakkarainen T, Korhonen M, Laitinen S, Valmu L, Lehenkari P. Cell surface structures influence lung clearance rate of systemically infused mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2013;31:317-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kumar S, Ponnazhagan S. Bone homing of mesenchymal stem cells by ectopic alpha 4 integrin expression. FASEB J. 2007;21:3917-3927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pesaresi M, Bonilla-Pons SA, Sebastian-Perez R, Di Vicino U, Alcoverro-Bertran M, Michael R, Cosma MP. The Chemokine Receptors Ccr5 and Cxcr6 Enhance Migration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells into the Degenerating Retina. Mol Ther. 2021;29:804-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Singh M, Thakur M, Mishra M, Yadav M, Vibhuti R, Menon AM, Nagda G, Dwivedi VP, Dakal TC, Yadav V. Gene regulation of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1): A molecule with multiple functions. Immunol Lett. 2021;240:123-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhong L, Simard MJ, Huot J. Endothelial microRNAs regulating the NF-κB pathway and cell adhesion molecules during inflammation. FASEB J. 2018;32:4070-4084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kitagawa T, Kosuge H, Uchida M, Iida Y, Dalman RL, Douglas T, McConnell MV. RGD targeting of human ferritin iron oxide nanoparticles enhances in vivo MRI of vascular inflammation and angiogenesis in experimental carotid disease and abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45:1144-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Seo Y, Kang MJ, Kim HS. Strategies to Potentiate Paracrine Therapeutic Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ogay V, Sekenova A, Li Y, Issabekova A, Saparov A. The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;16:897-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Liu X, Wei Q, Lu L, Cui S, Ma K, Zhang W, Ma F, Li H, Fu X, Zhang C. Immunomodulatory potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: Targeting immune cells. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1094685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Guo Z, Zhao Z, Yang C, Song C. Transfer of microRNA-221 from mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles inhibits atherosclerotic plaque formation. Transl Res. 2020;226:83-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Xiao X, Xu M, Yu H, Wang L, Li X, Rak J, Wang S, Zhao RC. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles mitigate oxidative stress-induced senescence in endothelial cells via regulation of miR-146a/Src. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Xu F, Fei Z, Dai H, Xu J, Fan Q, Shen S, Zhang Y, Ma Q, Chu J, Peng F, Zhou F, Liu Z, Wang C. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles with High PD-L1 Expression for Autoimmune Diseases Treatment. Adv Mater. 2022;34:e2106265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Feng R, Ullah M, Chen K, Ali Q, Lin Y, Sun Z. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles mitigate ageing-associated arterial stiffness and hypertension. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9:1783869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wang J, Huang R, Xu Q, Zheng G, Qiu G, Ge M, Shu Q, Xu J. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Alleviate Acute Lung Injury Via Transfer of miR-27a-3p. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e599-e610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cheng C, Liu D, Liu Z, Li M, Wang Y, Sun B, Kong R, Chen H, Wang G, Li L, Hu J, Li Y, Zhao Z, Zhang T, Zhu S, Pan S. Positive feedback regulation of lncRNA TPT1-AS1 and ITGB3 promotes cell growth and metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:2986-3001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Li S, Jiang S, Zhang Q, Jin B, Lv D, Li W, Zhao M, Jiang C, Dai C, Liu Z. Integrin β3 Induction Promotes Tubular Cell Senescence and Kidney Fibrosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:733831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kotlyarov S, Russia; Liao Z, Singapore; Shalaby MN, Egypt; Ventura C, Italy; Ventura C, Italy S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD