Published online Aug 26, 2020. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i8.776

Peer-review started: February 28, 2020

First decision: April 25, 2020

Revised: May 17, 2020

Accepted: June 20, 2020

Article in press: June 20, 2020

Published online: August 26, 2020

Processing time: 179 Days and 16.5 Hours

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been widely exploited as promising candidates in clinical settings for bone repair and regeneration in view of their self-renewal capacity and multipotentiality. However, little is known about the mechanisms underlying their fate determination, which would illustrate their effectiveness in regenerative medicine. Recent evidence has shed light on a fundamental biological role of autophagy in the maintenance of the regenerative capability of MSCs and bone homeostasis. Autophagy has been implicated in provoking an immediately available cytoprotective mechanism in MSCs against stress, while dysfunction of autophagy impairs the function of MSCs, leading to imbalances of bone remodeling and a wide range of aging and degenerative bone diseases. This review aims to summarize the up-to-date knowledge about the effects of autophagy on MSC fate determination and its role as a stress adaptation response. Meanwhile, we highlight autophagy as a dynamic process and a double-edged sword to account for some discrepancies in the current research. We also discuss the contribution of autophagy to the regulation of bone cells and bone remodeling and emphasize its potential involvement in bone disease.

Core tip: Autophagy is a dynamic recycling mechanism that fuels cellular renovation and homeostasis. Recent studies have shed light on an essential role of autophagy in orchestrating self-renewal and the multilineage differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), thus coordinating bone homeostasis. This review outlines the effects of autophagy on MSCs fate determination and cytoprotection under different kinds of stresses. Moreover, we emphasize that the involvement of autophagy ensures balanced bone remodeling, which will be of significance in facilitating its application as a therapeutic target in bone repair and regeneration.

- Citation: Chen XD, Tan JL, Feng Y, Huang LJ, Zhang M, Cheng B. Autophagy in fate determination of mesenchymal stem cells and bone remodeling. World J Stem Cells 2020; 12(8): 776-786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v12/i8/776.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v12.i8.776

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous cellular population that can be detected in and isolated from bone marrow, adipose, vascular, umbilical cord, placenta, skin, and kidney[1-3]. Characterized by their potential of self-renewal and differentiation into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages, they are considered promising therapeutic agents that confer a positive benefit to bone maintenance, repair, and regeneration[4]. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the underlying mechanisms regulating MSCs function would offer great promise in the field of bone regenerative medicine.

Autophagy is a conserved degradation process during which proteins and damaged organelles are engulfed by autophagosomes and then fused with lysosomes to be degraded for intracellular recycling to fuel cellular renovation[5,6]. There are three types of autophagy in mammals, including macroautophagy[7], microautophagy[8], and chaperone-mediated autophagy[9], among which macroautophagy is in the spotlight for its crucial effects on cell biology and will be henceforth referred to as “autophagy” in this review.

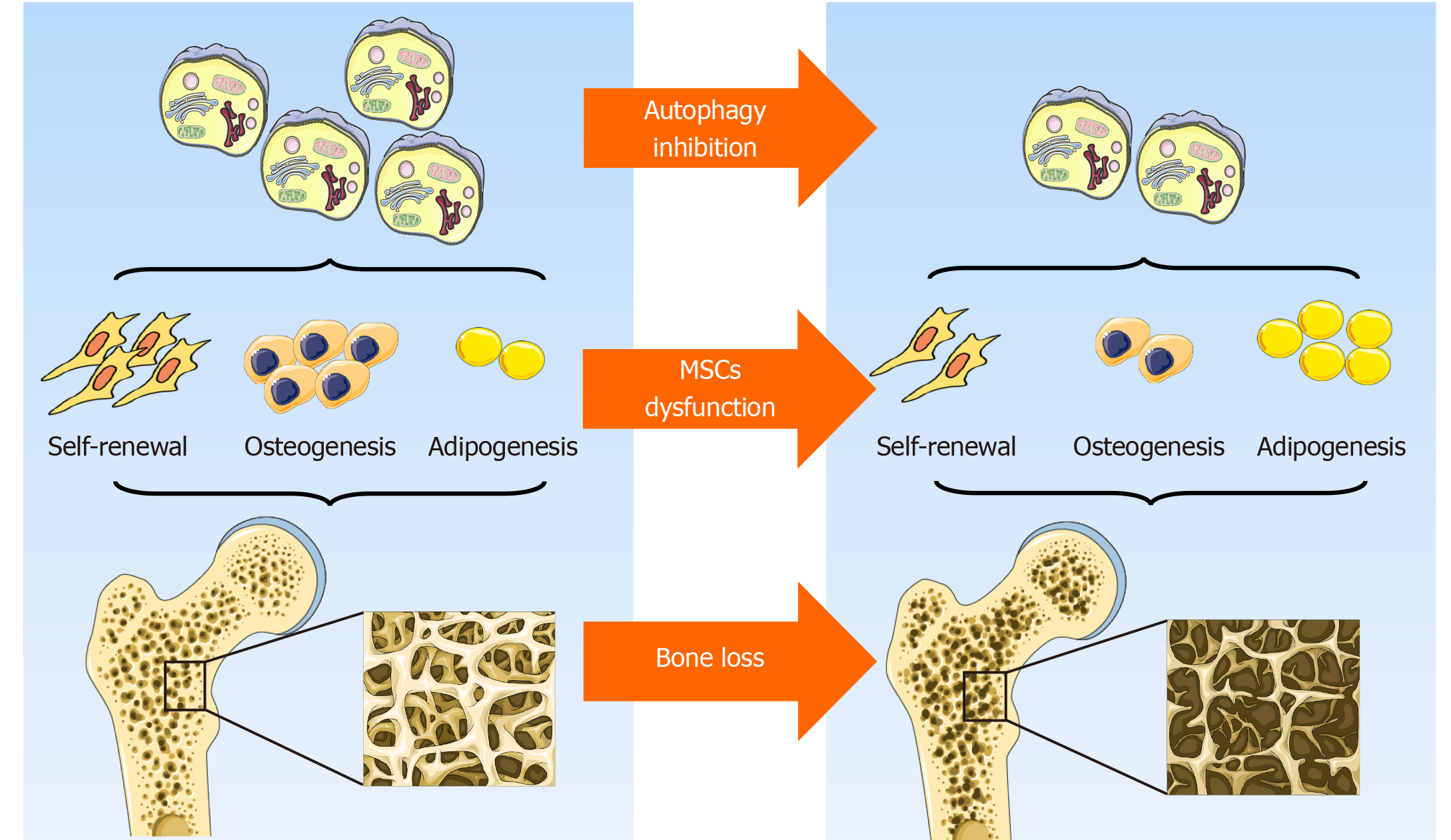

Recent evidence has shed light on a fundamental role of autophagy in the fate determination of MSCs and the maintenance of bone homeostasis. In addition, autophagy has also been implicated as an immediately available cytoprotective mechanism in MSCs against stress[10,11]. Dysfunction of autophagy would impair the function of MSCs, leading to imbalances of bone remodeling and thus inducing a wide range of aging and degenerative bone diseases. Further delineation of the relationships among autophagy, MSCs function, and bone homeostasis would uncover new avenues for novel therapeutic strategies for bone repair and regeneration.

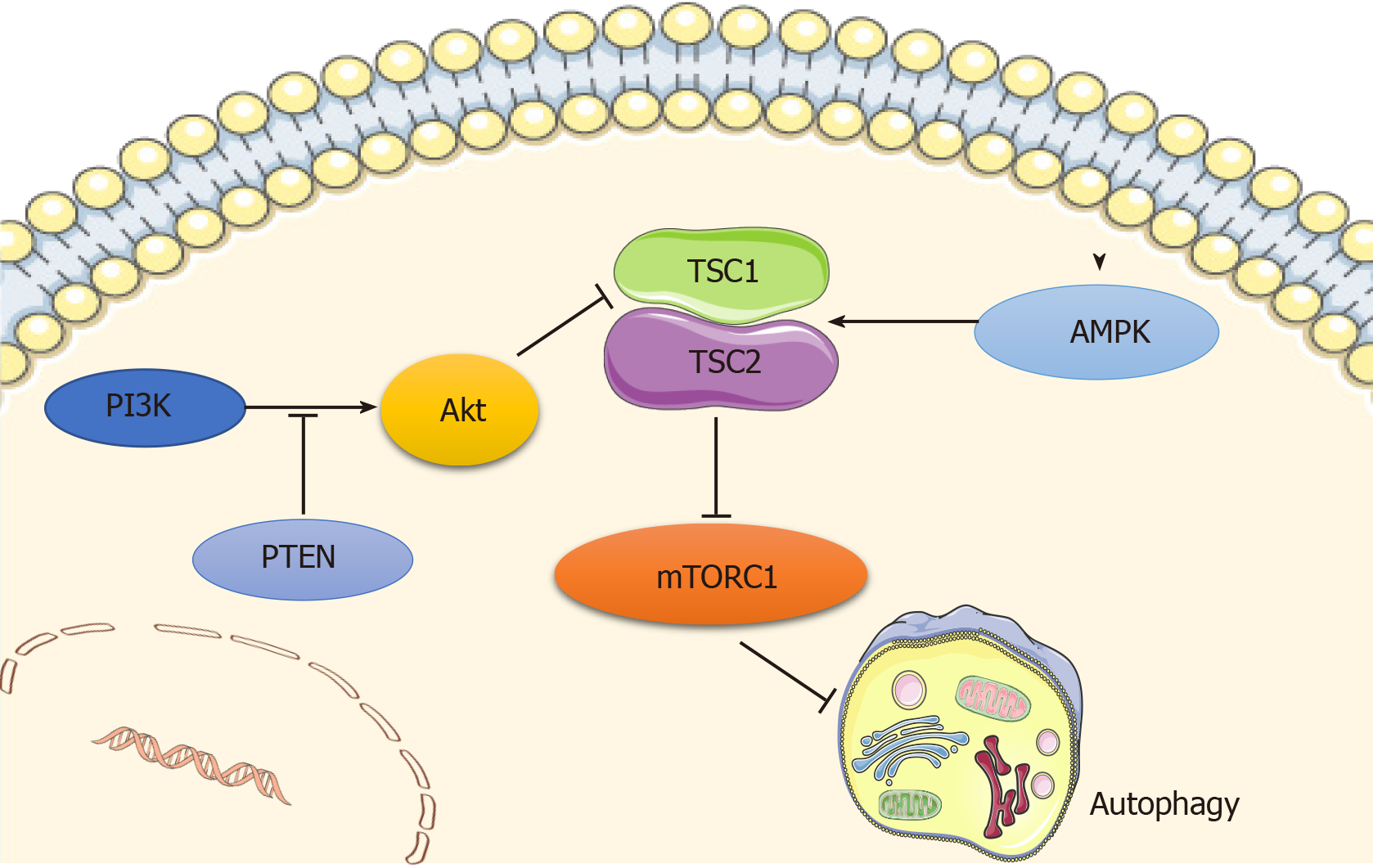

Autophagy is regulated by a number of signaling pathways, among which the most well-known are the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and the phosphoinositide3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways, which converge on mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a well-recognized negative regulator of autophagy that integrates nutrient signals[12] (Figure 1). mTOR recruits other regulatory proteins to form two distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, and mTORC1 is involved in autophagy regulation[13].

AMPK is a principal intracellular energy sensor, which conserves energy by inhibiting mTOR[14] by phosphorylating and potentiating tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) or by directly binding to RAPTOR, a key subunit of mTORC1[15], and consequently inducing autophagy[16]. Furthermore, the PI3K/AKT pathway is also an important mTOR modulator that inhibits the mTOR repressor TSC[17], activates mTOR, and then blocks autophagy activity[12]. In addition, wnt/β-catenin has been shown to be a negative regulator of autophagy, while PTEN induces autophagy by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and activated EGFR/Ras/MEK/ERK, JUK/c-Jun, and p38 MAPK signaling pathways have also been revealed as stimulators of autophagy[18].

Considerable evidence has shown a pivotal regulatory role of autophagy in self–renewal capacity and lineage determination of MSCs. Induction of autophagy in bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) may account for a decrease in their S-phase population and trigger their differentiation into neurons[19]. Despite some controversy, Isomoto et al[20] clarified that rapamycin does not have a spontaneous osteogenic effect on MSCs, while most studies have confirmed that autophagy contributes to the switch between osteogenesis and adipogenesis of BMSCs. More specifically, MSCs tend to accumulate undergraded autophagic vacuoles and undergo little autophagic turnover, while osteogenic differentiation of MSCs results in more autophagic turnover[21]. Induction of osteogenic differentiation of human gingiva-derived MSCs (HGMSCs) potentiates autophagy signaling, while inhibition of autophagy precludes osteoblast differentiation of HGMSCs[22]. The autophagy inducer rapamycin promotes osteoblast differentiation in human embryonic stem cells (ESC) by interfering with mTOR while augmenting the BMP/Smad signaling pathway[23].

Osterix-expressing cells with a specific deletion of TSC1, a positive regulator of autophagy, have shown that TSC1 deficiency is responsible for the reduction of bone mass, as characterized by inhibition of osteogenesis, enhancement of osteoclastogenesis, and elevation of bone marrow adiposity[24]. Consistently, TSC1 deficiency in BMSCs results in decreased proliferation and a tendency to differentiate into adipocytes instead of osteoblasts[24].

Other studies have provided evidence that early mTOR suppression accompanied by late Akt/mTOR activation contributes to osteoblast differentiation of MSCs[25]. Accordingly, activation of autophagy by mTOR inhibition facilitates osteoblast differentiation[25], though whether late mTOR induction and subsequent autophagy inhibition would stimulate or interfere with osteogenesis remains to be elucidated. Another study in MC3T3 cells also revealed that early activation and subsequent inhibition of AMPK are indispensable for osteoblast differentiation[26]. Given that mTOR functions as an inhibitor and AMPK as a stimulator of autophagy, these two studies coincide in that autophagy is fueled at first and then abrogated during osteoblast differentiation. We theorized that such time-dependent catabolic dynamics seem fundamental to ensure the ever-changing energy demands during all stages of osteogenesis.

Although several studies have revealed that autophagy is activated during aging in cells such as fibroblasts[27] and BMSCs[28], the mainstream view currently is that with aging, autophagy decreases in different kinds of tissues, ranging from the kidney to the brain[29,30]. Indeed, it has been reported that autophagy activity is significantly reduced in aged BMSCs compared with their young counterparts[31]. Basal autophagy has a crucial role in the maintenance of the young state of satellite cells, and dysfunction of autophagy leads to cell senescence as indicated by the decrease in satellite cell number and function[32]. In addition, blockage of autophagy converts young BMSCs to a relatively aged state by impairing their osteoblast differentiation and proliferation potential while promoting their adipocyte differentiation ability. Correspondingly, activation of autophagy turns aged BMSCs into a young state by strengthening osteoblast differentiation and proliferation potential while impairing adipocyte differentiation capacity[31]. Likewise, pretreatment with rapamycin remarkably alleviates MSC aging induced by D-gal and decreases of p-JNK, p-38, and ROS generation, supporting the concept that autophagy exerts a protective role in MSCs senescence[33]. This protective effect of rapamycin on MSCs senescence can be abolished by increasing the ROS level, and inhibition of p38 can rescue the H2O2-induced MSCs senescence, which suggests that ROS/JNK/p38 signaling contributes to mediating autophagy-delayed MSCs senescence[33].

Collectively, autophagy is a surveillance pathway that tightly controls fate decisions of MSCs, and therefore it should be considered when searching for methods to maintain the pluripotency of MSCs.

Autophagy is known to exert cytoprotection for MSCs under stress conditions[34]. It has been demonstrated that hypoxia-pretreated MSCs exhibit AMPK/mTOR signaling activation, autophagy enhancement, and pro-angiogenic effect improvements[35]. Similarly, Zhang et al[36] showed that the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA) promotes hypoxia-induced apoptosis, while a positive inducer of autophagy, rapamycin, decreases hypoxia-induced apoptosis, suggesting that autophagy seems to be a protective element in MSCs under hypoxic stress and that atorvastatin could improve BMSCs survival during hypoxia by enhancing autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR pathway. However, there are also studies showing that hypoxia activates the autophagic flux of BMSCs through the AMPK/mTOR pathway and that activation of the latter process plays an important role in hypoxia-induced apoptosis[37-39]. This complicated scenario might be due to the heterogeneity and site-specific properties of the MSCs. For instance, BMSCs derived from the mandible have higher expression of the stemness markers Nanog, Oct-4, and Sox2, as well as stronger autophagy and anti-aging capacities under normoxia or hypoxia, when compared to those derived from the tibia[40].

A recent study showed that oxidative stress-induced MSCs death could be prevented by carbon monoxide, and this protective effect is due to an increase of autophagy[41]. Autophagy facilitates the turnover of damaged cellular components, which may result in improved cellular survival in the setting of oxidative injury. Therefore, depletion of autophagy in MSCs exacerbates oxidative stress-induced MSCs death[41]. Augmenting autophagy by JNK activation also protects MSCs against oxidative damage, thereby improving MSCs survival[42]. Preconditioning or coconditioning with rapamycin alleviates, while 3-MA aggravates, H2O2-induced cell apoptosis[34]. Likewise, H2O2-treated human MSCs (hMSCs) activates FOXO3 and then induces autophagy in response to the elevated ROS level, thus preventing oxidative injury. In line with this, suppression of autophagy impairs ROS elimination and the osteogenic capacity of hMSCs[43]. However, it is worth noting that these cytoprotective effects of autophagy on MSCs in the context of oxidative damage seem to act in a stress severity- and duration-dependent manner. Autophagy flux is considered to be a self-defensive process during the early stage of MSCs injury induced by H2O2, and this protective effect would be abolished after sustained oxidative exposure (i.e., 6 h), as demonstrated by increased levels of caspase-3 and caspase-6[34], which indicates that adaptive autophagy contributes to an improved survival rate of MSCs under stress, while destructive autophagy is induced when it fails to manage excessive stress[44].

As the main mechanism by which cells initiate self-protection in a radiation microenvironment[45,46], autophagy triggers a DNA damage response by regulating DNA repair and checkpoint protein levels[47]. Some studies have reported that autophagy decreases after irradiation, suggesting an impairment in eliminating damaged cellular components[48]. Activation of autophagy in MSCs reduces radiation-generated ROS and DNA damage, leading to the maintenance of stemness and differentiation potential[34,49], while suppression of autophagy results in more ROS generation, DNA damage, and worsening of self-renewal ability[49]. This radio-protective role of autophagy on MSCs is further supported by the observation that hypoxia increases both the autophagy level and MSCs radioresistance via ERK1/2 and mTOR signaling[50-52], suggesting a positive relationship between autophagy and the radioresistance of MSCs.

Increasing evidence has shown that autophagy provides a crucial line of induction and modulation of the inflammatory status of MSCs. In a TNF-α/cycloheximide-induced inflammatory environment, enhancement of autophagy reverses the decreased survival rate of MSCs, while inhibition of autophagy aggravates apoptotic progression[53]. Nevertheless, there have been reports of the adverse regulatory effects of autophagy in MSCs. The inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ synergistically enhance autophagy in MSCs, as evidenced by increased expression of BECN-1/Beclin-1. Knockdown of Beclin1 improves the therapeutic effects of MSCs and increases their survival by promoting Bcl-2 expression via the ROS/MAPK1/3 pathway[54,55]. Wang et al[56] showed that autophagy is triggered in MSCs in response to a liver fibrosis (LF) microenvironment. Of note, autophagy suppression can improve the antifibrotic potential of MSCs and this contributes to their inhibitory effects on T lymphocyte infiltration as well as the production of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ[56]. Additionally, inhibition of autophagy increases ROS accumulation and MAPK 1/3 activation in MSCs, which are essential for prostaglandin E2 expression to exert an immunoregulatory function, thus resulting in enhanced suppression upon activation and expansion of CD4+ T cells and leading to upregulation of the immunosuppressive function of MSCs[54]. This implies that autophagy may not always be beneficial in protecting the reparative effect of MSCs. Hence, modulating the multifaceted effects of autophagy in MSCs would provide a novel strategy to improve MSCs-based therapy.

Bone remodeling is dynamic process that helps to maintain bone integrity and mineral homeostasis. There are three kinds of cell types involved in bone remodeling: Osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and osteocytes[57]. Among them, both osteoblasts and osteocytes are derived from BMSCs, while osteoclasts have a hematopoietic origin[58]. Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells that initiate bone remodeling by digesting old bone, whereas osteoblasts are responsible for synthesizing and secreting bone matrix to form new bone[58]. Osteocytes, as the most abundant cell type in bone tissue, are pivotal in bone remodeling by coupling osteoblasts and osteoclasts activities[59] via the receptor activator of NF-kappa B (RANK)/receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) system[57]. Though still in its infancy, growing evidence has clarified that autophagy is closely related to bone remodeling mediated by osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and osteocytes, by which it exerts a critical role in coupling bone formation and bone resorption, thus maintaining normal postnatal bone homeostasis[60].

Previous research has demonstrated that activation of autophagy by AMPK signaling inhibits osteoclast differentiation[61]. Moreover, autophagy induced by OPG attenuates osteoclast bone resorption via the AKT/mTOR/ULK1 axis[62]. Similarly, autophagy favors OPG-mediated inhibition of osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption through the AMPK/mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway[63]. These data highlight a negative regulation of autophagy in osteoclastogenesis. However, Cao et al[64] showed that inhibiting autophagy suppresses TRPV4-induced osteoclast differentiation and osteoporosis via the Ca2+-calcinertin-NFATc1 pathway. In addition, JNK1-induced autophagy decreases apoptosis of osteoclast progenitors and stimulates RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis[65], which shows a positive effect of autophagy on osteoclast activity, suggesting a potential role of autophagy in initiating bone remodeling.

Moreover, autophagy promoted by estradiol protects osteoblasts from apoptosis via the ER-ERK-mTOR axis[66]. Interestingly, both early proliferation and differentiation are not interfered by inactivation of autophagy by FIP200 ablation, a fundamental element of mammalian autophagy, while osteoblast terminal differentiation is adversely affected, as shown by defective nodule formation[67], which suggests a positive role of autophagy in nodule formation. Consistently, osteoblastic mineralization is found to be accompanied by activation of autophagy, in which vacuoles could act as vehicles for crystals secretion. Thus, osteoblast specific autophagy deficient mice exhibit a significant reduction of mineralization and bone mass[68]. Bone mass in osteoblast-specific Atg7 conditional knockout (cKO) mice is significantly decreased compared with the control, the phenotype of which is caused by a decrease of osteoblast number and mineralization, as well as an increase of osteoclast number and osteoclast activity[60]. These results mean that autophagy exerts a critical role in osteoblast differentiation.

Yang et al[69] suggested a negative correlation between osteocyte autophagy and an ovariectomy (OVX) induced oxidative stress condition and bone loss. Reduction of autophagy by estrogen deficiency promotes the apoptosis of osteocytes, whereas restoration of autophagy strengthens the anti-apoptotic effects to improve osteocyte viability[70]. Osteocytes-specific cKO of Atg7, a key gene involved in autophagy, results in reduced bone mass, decreased cancellous and cortical bone thickness, and increased cortical bone porosity at 6 mo for both male and female mice, which contributes to decreases in osteoblast number, bone formation rate, and osteoclast number[71]. In addition, EphrinB2 in osteocytes limits autophagy to ensure bone quality by controlling mineral accumulation, while dysfunction of the osteocytic EphrinB2-autophagy signal results in bone fragility[72]. These findings emphasize a central role of autophagy in regulating osteocyte biology as well as bone remodeling.

Increasing numbers of studies have revealed a crucial role of autophagy in the development and progression of many kinds of bone disease, such as osteopetrosis, Paget's disease, and osteoporosis[73-75]. Recently, a genome-wide association study of wrist bone mineral density caught our attention since it revealed a close relationship between osteoporosis and autophagy[76]. Further research demonstrated that MSCs from an osteoporosis mouse model induced by estrogen deficiency exhibit reduced autophagy, which is associated with abnormal regenerative function[73]. Interestingly, restoration of autophagy by administrating rapamycin rescues the regenerative function of MSCs and protects OVX mice from osteoporotic development[73]. A similar decreased level of autophagy is also observed in OVX rats, while restoration of autophagy in osteoblasts by overexpressing autophagy gene damage-regulated autophagy modulator (DRAM) inhibits osteoblast proliferation and promotes their apoptosis[77]. In addition, activation of autophagy restored bone loss in aged mice[31], whereas blockade of autophagy alleviated glucocorticoid-induced and OVX-induced bone loss by interfering with osteoclastogenesis[75]. What’s more, defective autophagy in osteoblasts results in mouse osteopenia[67]. In experimental models of arthritis, rapamycin treatment can reduce the number of osteoclasts and osteoclast formation, thus inhibiting bone absorption in young rats[78]. Furthermore, rapamycin reduces bone resorption in renal transplant patients[79], enhances osteogenic differentiation in a mouse model of osteopenia[80,81], and ameliorates age-induced bone defects in aged rats[82]. Further study is warranted to explore the potential application of autophagy modulators as preventive or therapeutic strategies in bone disease.

In general, although the prevailing views currently support the hypothesis that autophagy contributes to the maintenance of MSCs integrity by preserving their self-renewal and osteoblast differentiation potential while inhibiting adipocyte differentiation, thus orchestrating bone homeostasis (Figure 2), some data are still somewhat controversial. To some extent, autophagy is a dynamic process that depends on immediate cellular energy demands. Thus, it is necessary to investigate its biological role along a timeline instead of at a single isolated time point. In addition, autophagy may act as a double-edged sword, the effects of which are modified in response to the features, severity, and duration of a specific stress. Furthermore, the latest study emphasizes a critical role of mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, in stem cell fate plasticity and determination[83,84]. Effects of an underlying crosstalk between autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress in MSCs and bone biology regulation is also beginning to be uncovered[85]. Further study is needed to lift the veil on the pleiotropy of autophagy, its reciprocal and functional interactions with other organelles, and their role in MSCs functional orchestration and bone biology modulation.

| 1. | Murray IR, West CC, Hardy WR, James AW, Park TS, Nguyen A, Tawonsawatruk T, Lazzari L, Soo C, Péault B. Natural history of mesenchymal stem cells, from vessel walls to culture vessels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:1353-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parolini O, Alviano F, Bagnara GP, Bilic G, Bühring HJ, Evangelista M, Hennerbichler S, Liu B, Magatti M, Mao N, Miki T, Marongiu F, Nakajima H, Nikaido T, Portmann-Lanz CB, Sankar V, Soncini M, Stadler G, Surbek D, Takahashi TA, Redl H, Sakuragawa N, Wolbank S, Zeisberger S, Zisch A, Strom SC. Concise review: isolation and characterization of cells from human term placenta: outcome of the first international Workshop on Placenta Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:300-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 758] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Levi B, Longaker MT. Concise review: adipose-derived stromal cells for skeletal regenerative medicine. Stem Cells. 2011;29:576-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chanda D, Kumar S, Ponnazhagan S. Therapeutic potential of adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in diseases of the skeleton. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:249-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1502] [Cited by in RCA: 1694] [Article Influence: 105.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3678] [Cited by in RCA: 5130] [Article Influence: 342.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gomes LC, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial morphology in mitophagy and macroautophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dubouloz F, Deloche O, Wanke V, Cameroni E, De Virgilio C. The TOR and EGO protein complexes orchestrate microautophagy in yeast. Mol Cell. 2005;19:15-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Majeski AE, Dice JF. Mechanisms of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2435-2444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salemi S, Yousefi S, Constantinescu MA, Fey MF, Simon HU. Autophagy is required for self-renewal and differentiation of adult human stem cells. Cell Res. 2012;22:432-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oliver L, Hue E, Priault M, Vallette FM. Basal autophagy decreased during the differentiation of human adult mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2779-2788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1287-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1471] [Cited by in RCA: 1721] [Article Influence: 107.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang H, Liu Y, Wang D, Xu Y, Dong R, Yang Y, Lv Q, Chen X, Zhang Z. The Upstream Pathway of mTOR-Mediated Autophagy in Liver Diseases. Cells. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shaw RJ. LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase control of mTOR signalling and growth. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2009;196:65-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang Y, Zhang H. Regulation of Autophagy by mTOR Signaling Pathway. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1206:67-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1403] [Cited by in RCA: 1624] [Article Influence: 95.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 593] [Cited by in RCA: 607] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu Z, Han X, Ou D, Liu T, Li Z, Jiang G, Liu J, Zhang J. Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mediated autophagy for tumor therapy. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:575-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li B, Duan P, Li C, Jing Y, Han X, Yan W, Xing Y. Role of autophagy on bone marrow mesenchymal stem-cell proliferation and differentiation into neurons. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:1413-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Isomoto S, Hattori K, Ohgushi H, Nakajima H, Tanaka Y, Takakura Y. Rapamycin as an inhibitor of osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12:83-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nuschke A, Rodrigues M, Stolz DB, Chu CT, Griffith L, Wells A. Human mesenchymal stem cells/multipotent stromal cells consume accumulated autophagosomes early in differentiation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vidoni C, Ferraresi A, Secomandi E, Vallino L, Gardin C, Zavan B, Mortellaro C, Isidoro C. Autophagy drives osteogenic differentiation of human gingival mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2019;17:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee KW, Yook JY, Son MY, Kim MJ, Koo DB, Han YM, Cho YS. Rapamycin promotes the osteoblastic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells by blocking the mTOR pathway and stimulating the BMP/Smad pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Choi HK, Yuan H, Fang F, Wei X, Liu L, Li Q, Guan JL, Liu F. Tsc1 Regulates the Balance Between Osteoblast and Adipocyte Differentiation Through Autophagy/Notch1/β-Catenin Cascade. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:2021-2034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pantovic A, Krstic A, Janjetovic K, Kocic J, Harhaji-Trajkovic L, Bugarski D, Trajkovic V. Coordinated time-dependent modulation of AMPK/Akt/mTOR signaling and autophagy controls osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Bone. 2013;52:524-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xi G, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR. IGF-I and IGFBP-2 Stimulate AMPK Activation and Autophagy, Which Are Required for Osteoblast Differentiation. Endocrinology. 2016;157:268-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Demirovic D, Nizard C, Rattan SI. Basal level of autophagy is increased in aging human skin fibroblasts in vitro, but not in old skin. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zheng Y, Hu CJ, Zhuo RH, Lei YS, Han NN, He L. Inhibition of autophagy alleviates the senescent state of rat mesenchymal stem cells during long-term culture. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:3003-3008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kume S, Uzu T, Horiike K, Chin-Kanasaki M, Isshiki K, Araki S, Sugimoto T, Haneda M, Kashiwagi A, Koya D. Calorie restriction enhances cell adaptation to hypoxia through Sirt1-dependent mitochondrial autophagy in mouse aged kidney. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1043-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lipinski MM, Zheng B, Lu T, Yan Z, Py BF, Ng A, Xavier RJ, Li C, Yankner BA, Scherzer CR, Yuan J. Genome-wide analysis reveals mechanisms modulating autophagy in normal brain aging and in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14164-14169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 578] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ma Y, Qi M, An Y, Zhang L, Yang R, Doro DH, Liu W, Jin Y. Autophagy controls mesenchymal stem cell properties and senescence during bone aging. Aging Cell. 2018;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | García-Prat L, Martínez-Vicente M, Perdiguero E, Ortet L, Rodríguez-Ubreva J, Rebollo E, Ruiz-Bonilla V, Gutarra S, Ballestar E, Serrano AL, Sandri M, Muñoz-Cánoves P. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature. 2016;529:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 791] [Cited by in RCA: 1059] [Article Influence: 105.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhang D, Chen Y, Xu X, Xiang H, Shi Y, Gao Y, Wang X, Jiang X, Li N, Pan J. Autophagy inhibits the mesenchymal stem cell aging induced by D-galactose through ROS/JNK/p38 signalling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47:466-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Song C, Song C, Tong F. Autophagy induction is a survival response against oxidative stress in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:1361-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Liu J, Hao H, Huang H, Tong C, Ti D, Dong L, Chen D, Zhao Y, Liu H, Han W, Fu X. Hypoxia regulates the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells through enhanced autophagy. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang Q, Yang YJ, Wang H, Dong QT, Wang TJ, Qian HY, Xu H. Autophagy activation: a novel mechanism of atorvastatin to protect mesenchymal stem cells from hypoxia and serum deprivation via AMP-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1321-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Molaei S, Roudkenar MH, Amiri F, Harati MD, Bahadori M, Jaleh F, Jalili MA, Mohammadi Roushandeh A. Down-regulation of the autophagy gene, ATG7, protects bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from stressful conditions. Blood Res. 2015;50:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhang Z, Yang M, Wang Y, Wang L, Jin Z, Ding L, Zhang L, Zhang L, Jiang W, Gao G, Yang J, Lu B, Cao F, Hu T. Autophagy regulates the apoptosis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells under hypoxic condition via AMP-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Cell Biol Int. 2016;40:671-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2430] [Cited by in RCA: 2861] [Article Influence: 150.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Dong W, Zhang P, Fu Y, Ge J, Cheng J, Yuan H, Jiang H. Roles of SATB2 in site-specific stemness, autophagy and senescence of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:680-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ghanta S, Tsoyi K, Liu X, Nakahira K, Ith B, Coronata AA, Fredenburgh LE, Englert JA, Piantadosi CA, Choi AM, Perrella MA. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Deficient in Autophagy Proteins Are Susceptible to Oxidative Injury and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:300-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Liu GY, Jiang XX, Zhu X, He WY, Kuang YL, Ren K, Lin Y, Gou X. ROS activates JNK-mediated autophagy to counteract apoptosis in mouse mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:1473-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gómez-Puerto MC, Verhagen LP, Braat AK, Lam EW, Coffer PJ, Lorenowicz MJ. Activation of autophagy by FOXO3 regulates redox homeostasis during osteogenic differentiation. Autophagy. 2016;12:1804-1816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Hu C, Zhao L, Wu D, Li L. Modulating autophagy in mesenchymal stem cells effectively protects against hypoxia- or ischemia-induced injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Braunstein S, Badura ML, Xi Q, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Regulation of protein synthesis by ionizing radiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5645-5656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8204-8209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 861] [Cited by in RCA: 947] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Alexander A, Cai SL, Kim J, Nanez A, Sahin M, MacLean KH, Inoki K, Guan KL, Shen J, Person MD, Kusewitt D, Mills GB, Kastan MB, Walker CL. ATM signals to TSC2 in the cytoplasm to regulate mTORC1 in response to ROS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4153-4158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 530] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Alessio N, Del Gaudio S, Capasso S, Di Bernardo G, Cappabianca S, Cipollaro M, Peluso G, Galderisi U. Low dose radiation induced senescence of human mesenchymal stromal cells and impaired the autophagy process. Oncotarget. 2015;6:8155-8166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Hou J, Han ZP, Jing YY, Yang X, Zhang SS, Sun K, Hao C, Meng Y, Yu FH, Liu XQ, Shi YF, Wu MC, Zhang L, Wei LX. Autophagy prevents irradiation injury and maintains stemness through decreasing ROS generation in mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sugrue T, Lowndes NF, Ceredig R. Hypoxia enhances the radioresistance of mouse mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2188-2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wu J, Niu J, Li X, Li Y, Wang X, Lin J, Zhang F. Hypoxia induces autophagy of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells via activation of ERK1/2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:1467-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lee Y, Jung J, Cho KJ, Lee SK, Park JW, Oh IH, Kim GJ. Increased SCF/c-kit by hypoxia promotes autophagy of human placental chorionic plate-derived mesenchymal stem cells via regulating the phosphorylation of mTOR. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:79-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 53. | Yang R, Ouyang Y, Li W, Wang P, Deng H, Song B, Hou J, Chen Z, Xie Z, Liu Z, Li J, Cen S, Wu Y, Shen H. Autophagy Plays a Protective Role in Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Apoptosis of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2016;25:788-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Dang S, Xu H, Xu C, Cai W, Li Q, Cheng Y, Jin M, Wang RX, Peng Y, Zhang Y, Wu C, He X, Wan B, Zhang Y. Autophagy regulates the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Autophagy. 2014;10:1301-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Dang S, Yu ZM, Zhang CY, Zheng J, Li KL, Wu Y, Qian LL, Yang ZY, Li XR, Zhang Y, Wang RX. Autophagy promotes apoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells under inflammatory microenvironment. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Wang HY, Li C, Liu WH, Deng FM, Ma Y, Guo LN, Kong H, Hu KA, Liu Q, Wu J, Sun J, Liu YL. Autophagy inhibition via Becn1 downregulation improves the mesenchymal stem cells antifibrotic potential in experimental liver fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:2722-2737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hadjidakis DJ, Androulakis II. Bone remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 989] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Jaber FA, Khan NM, Ansari MY, Al-Adlaan AA, Hussein NJ, Safadi FF. Autophagy plays an essential role in bone homeostasis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:12105-12115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Yan Y, Wang L, Ge L, Pathak JL. Osteocyte-Mediated Translation of Mechanical Stimuli to Cellular Signaling and Its Role in Bone and Non-bone-Related Clinical Complications. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18:67-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Li H, Li D, Ma Z, Qian Z, Kang X, Jin X, Li F, Wang X, Chen Q, Sun H, Wu S. Defective autophagy in osteoblasts induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes remarkable bone loss. Autophagy. 2018;14:1726-1741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tong X, Zhang C, Wang D, Song R, Ma Y, Cao Y, Zhao H, Bian J, Gu J, Liu Z. Suppression of AMP-activated protein kinase reverses osteoprotegerin-induced inhibition of osteoclast differentiation by reducing autophagy. Cell Prolif. 2020;53:e12714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Zhao H, Sun Z, Ma Y, Song R, Yuan Y, Bian J, Gu J, Liu Z. Antiosteoclastic bone resorption activity of osteoprotegerin via enhanced AKT/mTOR/ULK1-mediated autophagic pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:3002-3012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Tong X, Gu J, Song R, Wang D, Sun Z, Sui C, Zhang C, Liu X, Bian J, Liu Z. Osteoprotegerin inhibit osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by enhancing autophagy via AMPK/mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 2018;Online ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Cao B, Dai X, Wang W. Knockdown of TRPV4 suppresses osteoclast differentiation and osteoporosis by inhibiting autophagy through Ca2+ -calcineurin-NFATc1 pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:6831-6841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Ke D, Ji L, Wang Y, Fu X, Chen J, Wang F, Zhao D, Xue Y, Lan X, Hou J. JNK1 regulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via activation of a novel Bcl-2-Beclin1-autophagy pathway. FASEB J. 2019;33:11082-11095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Yang YH, Chen K, Li B, Chen JW, Zheng XF, Wang YR, Jiang SD, Jiang LS. Estradiol inhibits osteoblast apoptosis via promotion of autophagy through the ER-ERK-mTOR pathway. Apoptosis. 2013;18:1363-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Liu F, Fang F, Yuan H, Yang D, Chen Y, Williams L, Goldstein SA, Krebsbach PH, Guan JL. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion leads to osteopenia in mice through the inhibition of osteoblast terminal differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2414-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Nollet M, Santucci-Darmanin S, Breuil V, Al-Sahlanee R, Cros C, Topi M, Momier D, Samson M, Pagnotta S, Cailleteau L, Battaglia S, Farlay D, Dacquin R, Barois N, Jurdic P, Boivin G, Heymann D, Lafont F, Lu SS, Dempster DW, Carle GF, Pierrefite-Carle V. Autophagy in osteoblasts is involved in mineralization and bone homeostasis. Autophagy. 2014;10:1965-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Yang Y, Zheng X, Li B, Jiang S, Jiang L. Increased activity of osteocyte autophagy in ovariectomized rats and its correlation with oxidative stress status and bone loss. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;451:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Florencio-Silva R, Sasso GRS, Sasso-Cerri E, Simões MJ, Cerri PS. Effects of estrogen status in osteocyte autophagy and its relation to osteocyte viability in alveolar process of ovariectomized rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;98:406-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Onal M, Piemontese M, Xiong J, Wang Y, Han L, Ye S, Komatsu M, Selig M, Weinstein RS, Zhao H, Jilka RL, Almeida M, Manolagas SC, O'Brien CA. Suppression of autophagy in osteocytes mimics skeletal aging. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:17432-17440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 72. | Vrahnas C, Blank M, Dite TA, Tatarczuch L, Ansari N, Crimeen-Irwin B, Nguyen H, Forwood MR, Hu Y, Ikegame M, Bambery KR, Petibois C, Mackie EJ, Tobin MJ, Smyth GK, Oakhill JS, Martin TJ, Sims NA. Increased autophagy in EphrinB2-deficient osteocytes is associated with elevated secondary mineralization and brittle bone. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Bo T, Yan F, Guo J, Lin X, Zhang H, Guan Q, Wang H, Fang L, Gao L, Zhao J, Xu C. Characterization of a Relatively Malignant Form of Osteopetrosis Caused by a Novel Mutation in the PLEKHM1 Gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:1979-1987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Rea SL, Walsh JP, Layfield R, Ratajczak T, Xu J. New insights into the role of sequestosome 1/p62 mutant proteins in the pathogenesis of Paget's disease of bone. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:501-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Lin NY, Chen CW, Kagwiria R, Liang R, Beyer C, Distler A, Luther J, Engelke K, Schett G, Distler JH. Inactivation of autophagy ameliorates glucocorticoid-induced and ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1203-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Zhang L, Guo YF, Liu YZ, Liu YJ, Xiong DH, Liu XG, Wang L, Yang TL, Lei SF, Guo Y, Yan H, Pei YF, Zhang F, Papasian CJ, Recker RR, Deng HW. Pathway-based genome-wide association analysis identified the importance of regulation-of-autophagy pathway for ultradistal radius BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1572-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Tang N, Zhao H, Zhang H, Dong Y. Effect of autophagy gene DRAM on proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis, and autophagy of osteoblast in osteoporosis rats. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5023-5032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Cejka D, Hayer S, Niederreiter B, Sieghart W, Fuereder T, Zwerina J, Schett G. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling is crucial for joint destruction in experimental arthritis and is activated in osteoclasts from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2294-2302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Westenfeld R, Schlieper G, Wöltje M, Gawlik A, Brandenburg V, Rutkowski P, Floege J, Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Impact of sirolimus, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil on osteoclastogenesis--implications for post-transplantation bone disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:4115-4123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Darcy A, Meltzer M, Miller J, Lee S, Chappell S, Ver Donck K, Montano M. A novel library screen identifies immunosuppressors that promote osteoblast differentiation. Bone. 2012;50:1294-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Shimada M, Greer PA, McMahon AP, Bouxsein ML, Schipani E. In vivo targeted deletion of calpain small subunit, Capn4, in cells of the osteoblast lineage impairs cell proliferation, differentiation, and bone formation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21002-21010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Luo D, Ren H, Li T, Lian K, Lin D. Rapamycin reduces severity of senile osteoporosis by activating osteocyte autophagy. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:1093-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Chandel NS. Evolution of Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles. Cell Metab. 2015;22:204-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Martínez-Reyes I, Diebold LP, Kong H, Schieber M, Huang H, Hensley CT, Mehta MM, Wang T, Santos JH, Woychik R, Dufour E, Spelbrink JN, Weinberg SE, Zhao Y, DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. TCA Cycle and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Are Necessary for Diverse Biological Functions. Mol Cell. 2016;61:199-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Cinque L, Forrester A, Bartolomeo R, Svelto M, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Polishchuk E, Nusco E, Rossi A, Medina DL, Polishchuk R, De Matteis MA, Settembre C. FGF signalling regulates bone growth through autophagy. Nature. 2015;528:272-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arufe MC S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH