Published online Feb 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.114773

Revised: November 17, 2025

Accepted: December 29, 2025

Published online: February 21, 2026

Processing time: 130 Days and 3.5 Hours

Organ failure (OF) is a frequent and critical feature of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP). However, the association between OF patterns and mortality is still a subject of debate.

To compare the clinical profiles of SAP cases with and without new-onset OF (NOOF) and identify adverse outcome predictors.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with SAP at a tertiary referral hospital to assess OF patterns. Based on the observed OF episodes, the cohort was categorized into OF (n = 113) and NOOF (n = 38) groups, with the latter further subdivided into new-onset single OF (n = 17) and new-onset multi-OF (n = 21). Independent predictors of mortality were identified through multivariable logistic regression and Cox proportional-hazards models.

Significant differences were observed between the OF and NOOF groups in clinical severity and adverse outcomes, characterized by prolonged OF, extended organ support, and increased hospital length of stay. Binary logistic regression revealed significant associations with major complications [odds ratio (OR) = 13.2, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.1-83.5, P = 0.006], NOOF (OR = 7.4, 95%CI: 1.3-42.5, P = 0.024), and Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis score (OR = 4.0, 95%CI: 1.3-12.0, P = 0.013). The 90-day mortality Cox proportional-hazards regression showed similar results [new-onset single OF hazard ratio (HR) = 6.8, 95%CI: 1.4-33.5, P = 0.019; new-onset multi-OF HR = 33.2, 95%CI: 9.4-117.3, P < 0.001; Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis score HR = 2.5, 95%CI: 1.3-4.6, P = 0.005].

New-onset persistent OF, particularly multi-OF, substantially increases mortality after multivariable adjustment in patients with SAP, highlighting the need for further investigation.

Core Tip: The relationship between organ failure (OF) patterns and mortality in severe acute pancreatitis (AP) remains controversial. In this retrospective cohort of 151 patients with severe AP, we found that, after adjusting for initial multi-OF, the duration of OF, and infected pancreatic necrosis, the occurrence of new-onset OF - especially new-onset multi-OF - significantly increased both in-hospital and 90-day mortality rates. This novel perspective expands the theoretical framework linking OF patterns to adverse outcomes in AP and may prove pivotal for future pancreatitis grading systems and the design of related clinical trials.

- Citation: Zhang XT, Zhu H, Chen XC, Gao T, Chen M, Zhu ZH, Zhang BY, Yu WK. New-onset persistent organ failure predicts adverse outcomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(7): 114773

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i7/114773.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.114773

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a prevalent gastrointestinal disease with varied clinical courses. Most patients experience a mild form of the disease that improves with conservative treatment[1]. However, approximately 20% of patients develop severe AP (SAP)[2,3], which is characterized by persistent (> 48 hours) organ failure (OF). SAP requires intensive care and organ support, and its mortality rate can reach 40%[1,3].

Early-stage OF (≤ 1 week) is driven by an excessive inflammatory response and presents as a sudden-onset event with a relatively small therapeutic window[4]. In late-stage OF (> 1 week), infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN) is a major cause of organ dysfunction[3]. Additionally, interventions such as percutaneous, endoscopic, or surgical drainage of necrotic material[5-7], as well as complications, including bleeding, gastrointestinal fistula, and pancreatic duct rupture[8,9], may lead to new-onset single OF (NOSOF) or new-onset multi-OF (NOMOF), which can increase the risk of adverse outcomes.

A substantial knowledge gap remains regarding the incidence and prognostic significance of new-onset OF (NOOF) that develops during the late phase of SAP. In this retrospective cohort study at a tertiary referral center, we aimed to compare the clinical profiles of patients with and without NOOF to identify predictors of adverse outcomes.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a large tertiary teaching hospital in Eastern China between December 2019 and December 2024. The inclusion criteria were inpatients diagnosed with SAP whose hospitalization lasted > 48 hours. The exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, pregnancy, disease onset > 7 days before admission, and incomplete data. Structured electronic medical records with detailed data on vital signs, fluid accumulation, and organ support parameters were reviewed.

The diagnosis of AP required fulfilment of at least two of the following three criteria: (1) Acute, persistent, and severe upper abdominal pain; (2) Serum amylase or lipase levels ≥ 3 times the upper limit of normal; and (3) Imaging findings [computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound] showing pancreatic inflammation or necrosis. According to the modified Marshall scoring system[10], OF was diagnosed when a score of ≥ 2 was attained in any of the respiratory, circulatory, or renal systems. Multiple OF (MOF) was defined as the occurrence of two or more types of OF, and persistent OF (POF) as OF lasting > 48 hours. SAP was defined as AP with POF, in accordance with the 2012 Atlanta Classification[11]. Major complications included intra-abdominal hemorrhage, enterocutaneous fistula, and pancreatic fistula, as defined in previous research[12]. The 90-day mortality was defined as death from any cause within 90 days following admission. Mortality was ascertained through a combination of in-hospital medical records and post-discharge follow-up via telephone interviews.

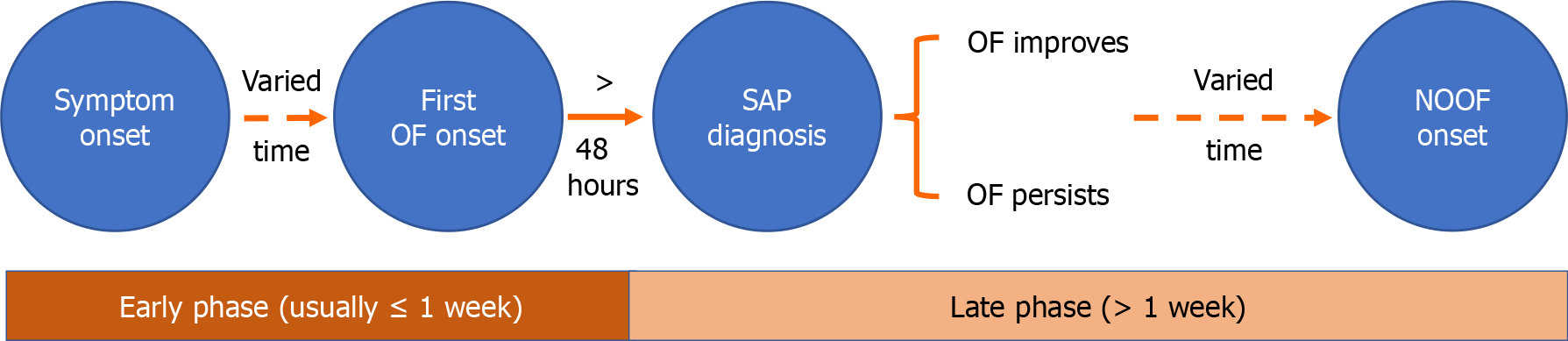

NOOF was defined as the occurrence of any new OF after SAP diagnosis and > 1 week after symptom onset. A schematic diagram depicting the onset and progression of OF in patients with AP is shown in Figure 1. The > 1-week threshold for NOOF is aligned with the 2012 Atlanta Classification, which delineates the early phase of AP as typically lasting the first week but potentially extending into the second. We established the 1-week cutoff to capture all relevant patients. NOOF did not require the prior absence of OF and could coexist with ongoing OF, given the difficulty in distinguishing whether staggered MOF results from the initial systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or a new insult (e.g., relatively early abdominal compartment syndrome). Patients without NOOF were classified into the OF group.

Standardized management - including fluid resuscitation, analgesic medications, and enteral nutrition - was instituted for patients with SAP[13]. Gastroenterologists performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for acute biliary pancreatitis. When clinical manifestations or CT imaging suggested IPN, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics were immediately administered, and a fine-needle biopsy was not routinely performed[14]. Appropriate organ support, including invasive mechanical ventilation, administration of vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy (RRT), was also provided as clinically indicated. A novel minimally invasive step-up drainage approach was used for pancreatic necrosis or other drainage needs, as previously described[15]. In accordance with guidelines, drainage was considered delayed if performed after ≥ 4 weeks, until necrosis was encapsulated[14].

Given the retrospective study design and absence of previous reports estimating effect size, a formal sample size calculation was not feasible. Therefore, we adopted a comprehensive enrollment approach by including all accessible eligible participants for robust analysis. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed and approved by the Medical Statistics Center of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital. We employed single imputation using central tendency measures to manage the missing data, given their low proportion (Supplementary Table 1) and presumed random nature. Specifically, missing body mass index values were imputed with the cohort mean, whereas missing Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) scores were imputed using the median value of the cohort.

Categorical variables are summarized using frequencies and percentages and were compared using the χ2 test, continuity-corrected χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD or median and interquartile range (P25-P75), depending on their distribution normality. Independent samples t-test, Student’s t-test, or the Mann-Whitney U test was applied based on the data distribution. Binary logistic regression, including both univariate and multivariate analyses, and Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses were used to assess the risk factors for in-hospital and 90-day mortality. Correlations between variables were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation analysis. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05.

For sensitivity analysis, we performed propensity score matching to control for potential confounding effects associated with invasive procedures. Specifically, the “step-up approach” and “open pancreatic necrosectomy” were used as matching covariates. A 1:2 nearest-neighbor matching algorithm was applied with a caliper width of 0.2. Given that “live discharge” represented a competing risk event for “90-day mortality”, we constructed both cause-specific and Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard models to verify the robustness of the results. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and R version 4.5.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

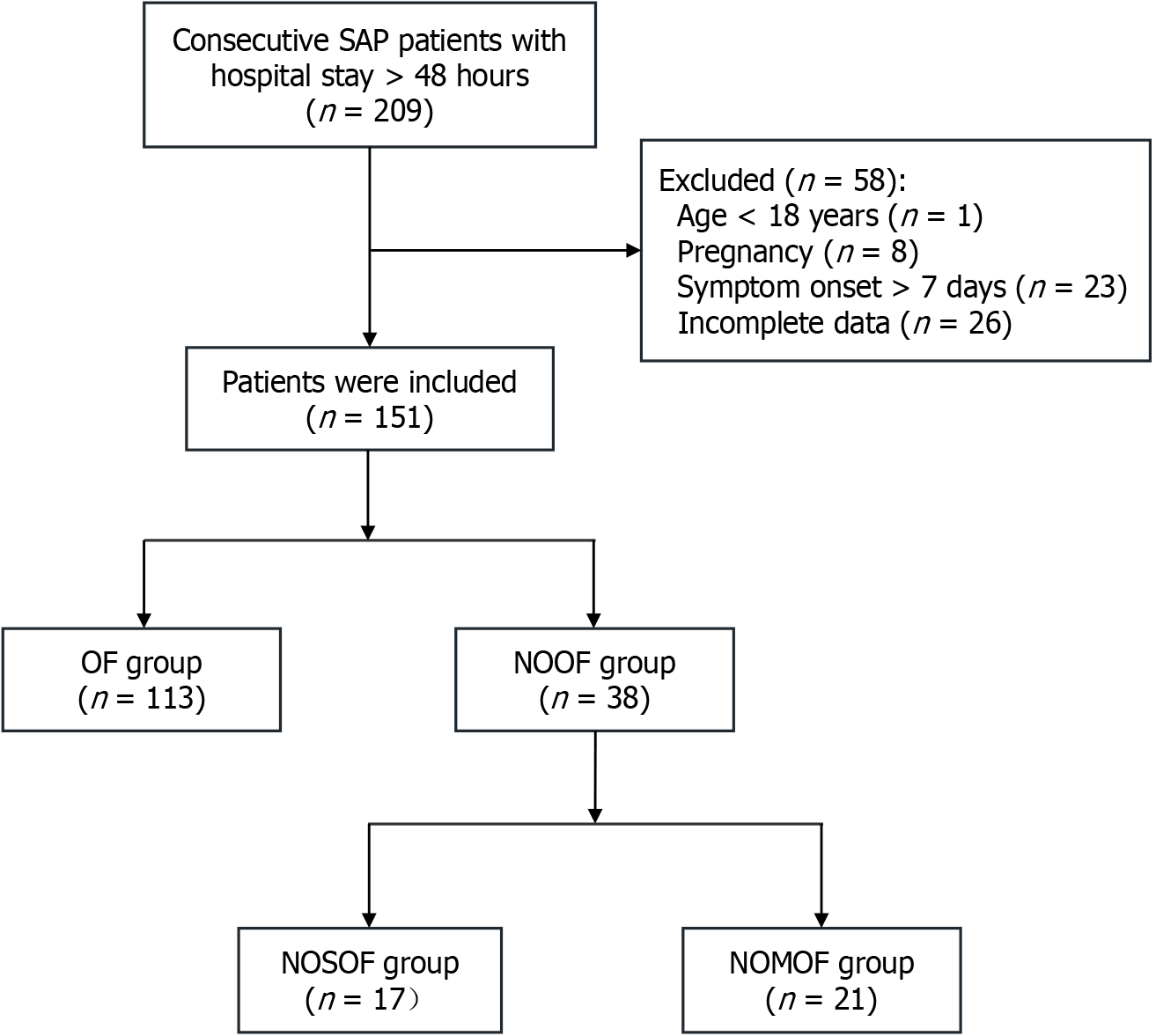

A total of 198 consecutive patients with SAP were screened, and 151 were ultimately included in the final analysis. The flowchart of patient enrollment is presented in Figure 2. Baseline characteristics and clinical features of the participants are presented in Table 1. The median age was 47 years (interquartile range, 35-61), with a nearly balanced sex distribution (males: 50.3%, females: 49.7%). Hyperlipidemia (n = 67, 44.4%) and cholelithiasis (n = 50, 33.1%) were the predominant etiologies, accounting for approximately 80% of the cases. Among participants, 113 experienced a single episode of POF during their index hospitalization (OF group). In addition, 38 patients (25.2%) developed new-onset POF (NOOF group), which included 21 (55.3%) with NOMOF and 17 (44.7%) with NOSOF.

| Characteristics | NOOF (n = 38) | OF (n = 113) | P value1 | P value2 | |

| NOMOF (n = 21) | NOSOF (n = 17) | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 42 (35, 67) | 48 (35, 59) | 48 (37, 59) | 0.663 | 0.791 |

| Male | 10 (47.6) | 11 (64.7) | 55 (48.7) | 0.482 | 0.292 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 25.6 ± 2.8 | 26.5 ± 2.8 | 26.4 ± 3.1 | 0.466 | 0.332 |

| Etiology | 0.186 | 0.652 | |||

| Biliary | 10 (47.6) | 7 (41.2) | 33 (29.2) | ||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 7 (33.3) | 8 (47.1) | 52 (46.0) | ||

| Others | 4 (19.0) | 2 (11.8) | 28 (24.8) | ||

| Severity | |||||

| APACHE II score, median (IQR) | 14 (11, 19) | 16 (13, 20) | 11 (8, 14) | < 0.001a | 0.263 |

| BISAP score, median (IQR) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (2, 3) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.001a | 0.117 |

| CTSI score, median (IQR) | 8 (8, 10) | 8 (6, 10) | 4 (4, 6) | < 0.001a | 0.348 |

| MOF on admission | 12 (57.1) | 9 (52.9) | 19 (16.8) | < 0.001a | 0.796 |

| OF duration > 2 weeks | 19 (90.5) | 10 (58.8) | 17 (15.0) | < 0.001a | 0.058 |

| IPN | 19 (90.5) | 14 (82.4) | 19 (16.8) | < 0.001a | 0.800 |

| Major complications | 15 (71.4) | 11 (64.7) | 13 (11.5) | < 0.001a | 0.658 |

| Interventions | |||||

| Step-up approach | 14 (66.7) | 11 (64.7) | 20 (17.7) | < 0.001a | 0.899 |

| OPN | 5 (23.8) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0) | < 0.001a | 0.950 |

Overall, the NOOF group demonstrated significantly greater severity in the early stages than the OF group, as evidenced by higher APACHE II (median 15 vs 11, P < 0.001), BISAP (median 3 vs 2, P = 0.001), and CT severity index (CTSI) (median 8 vs 4, P < 0.001) scores. Notably, over 50% of patients in the NOOF group presented with MOF (21/38) on admission, compared with 19 patients (16.8%) in the OF group.

Most patients in the NOOF group experienced OF lasting over 2 weeks (n = 29, 76.3%), with an even more pronounced trend in the NOMOF subgroup (n = 19, 90.5%). In contrast, only 15% (n = 17) of the patients in the OF group demon

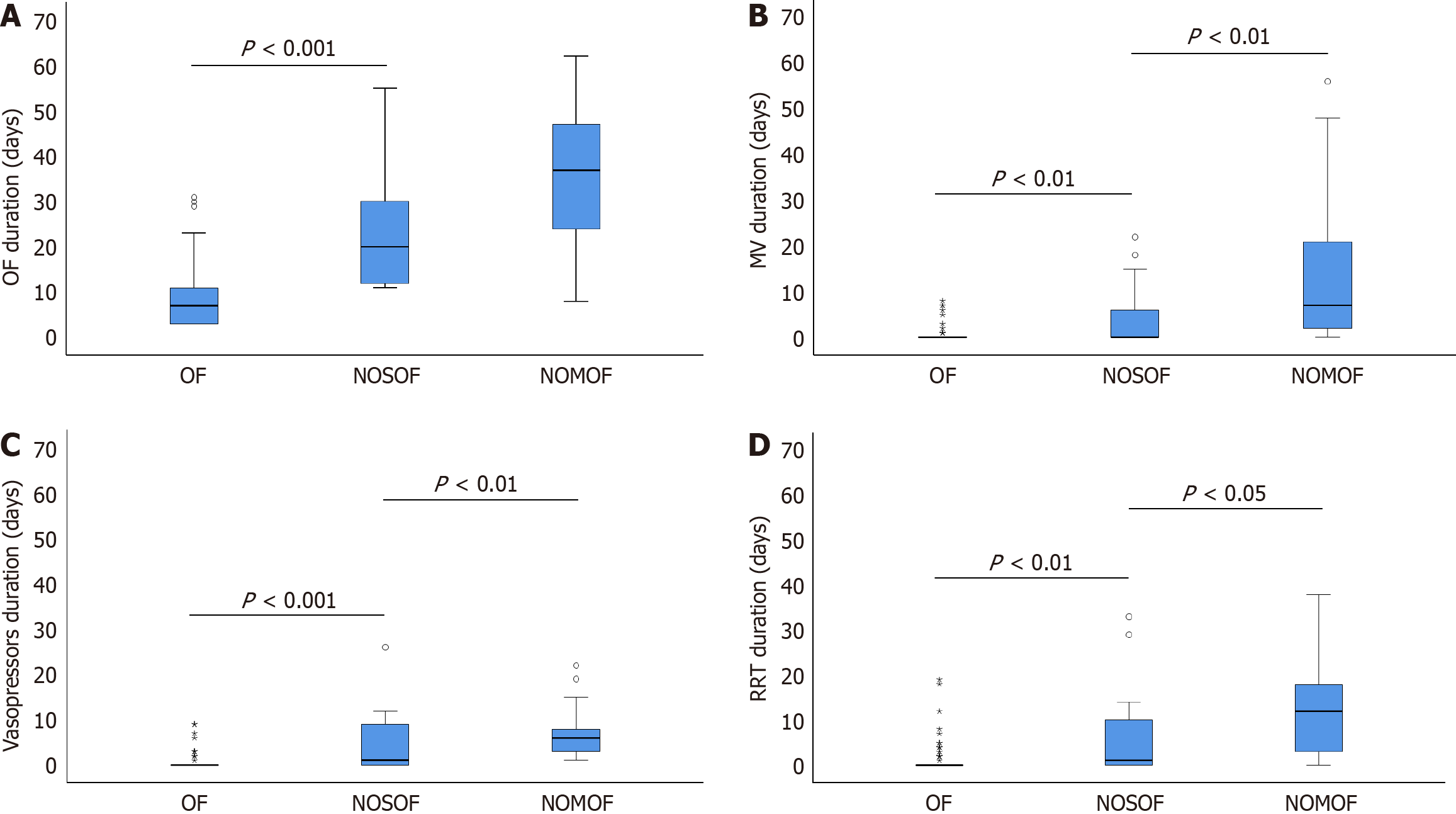

Clinical outcomes for both patient groups are detailed in Table 2. The NOOF group had a significantly prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, extended total hospitalization duration, and substantially higher total medical expenditure than the OF group. However, no significant differences were observed between the NOOF subgroups. In addition, the NOOF group had markedly longer durations across several key clinical parameters, including total OF, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drug administration, and RRT (Figure 3). These parameters were particularly pronounced in the NOMOF subgroup and significantly surpassed those in the OF group. Furthermore, the NOOF group demonstrated substantially higher mortality rates: In-hospital mortality was 34.2% vs 1.8% (P < 0.001) in the OF group, and 90-day mortality was 52.6% compared with 2.7% (P < 0.001) in the OF group. This increased mortality rate was predominantly driven by the NOMOF subgroup, highlighting the critical prognostic implications of NOMOF.

| Characteristics | NOOF (n = 38) | OF (n = 113) | P value1 | P value2 | |

| NOMOF (n = 21) | NOSOF (n = 17) | ||||

| ICU admission | 21 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 88 (77.9) | 0.002a | - |

| ICU LOS, median days (IQR) | 45 (24, 58) | 30 (13, 51) | 8 (3, 13) | < 0.001a | 0.347 |

| Hospital LOS, median days (IQR) | 50 (35, 62) | 93 (44, 117) | 29 (21, 40) | < 0.001a | 0.086 |

| Hospital care costs, thousand CNY, median (IQR) | 538 (309, 690) | 553 (273, 772) | 83 (55, 144) | < 0.001a | 0.941 |

| OF duration, median days (IQR) | 37 (21, 47) | 20 (12, 30) | 7 (3, 11) | < 0.001a | 0.015a |

| MV duration, median days (IQR) | 7 (2, 21) | 0 (0, 6) | 0 (0, 0) | < 0.001a | 0.016a |

| Vasopressors duration, median days (IQR) | 6 (3, 8) | 1 (0, 9) | 0 (0, 0) | < 0.001a | 0.028a |

| RRT duration, median days (IQR) | 12 (3, 18) | 1 (0, 10) | 0 (0, 0) | < 0.001a | 0.039a |

| In-hospital mortality | 12 (57.1) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (1.8) | < 0.001a | 0.001a |

| 90-day mortality | 17 (81.0) | 3 (17.6) | 3 (2.7) | < 0.001a | < 0.01a |

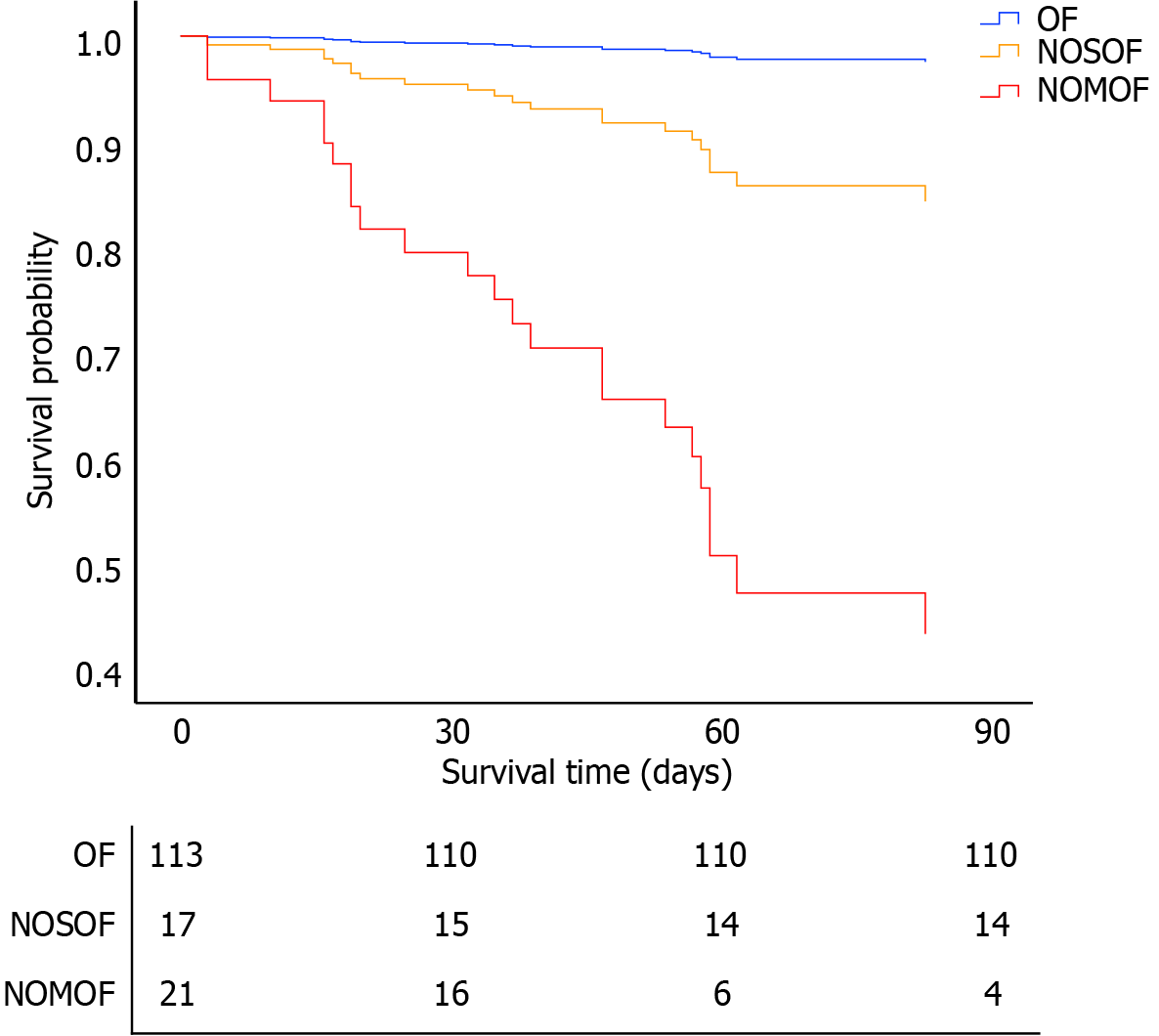

For analysis of adverse outcomes, a comprehensive set of single-factor variables were included in the multivariate regression model. These variables were age, sex, BISAP score, CTSI score, IPN, open pancreatic necrosectomy, major complications, MOF on admission, OF duration > 2 weeks, and NOOF (Table 3). The events-per-variable for this model was 1.5 (15 events/10 variables). The independent predictors of in-hospital mortality were major complications [odds ratio (OR) = 13.2, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.1-83.5, P = 0.006], NOOF (OR = 7.4, 95%CI: 1.3-42.5, P = 0.024), and the BISAP score (OR = 4.0, 95%CI: 1.3-12.0, P = 0.013). Similarly, the Cox proportional-hazards model, after adjusting for the aforementioned variables (events-per-variable was 2.3), showed that the risk factors for 90-day mortality were NOOF [NOSOF hazard ratio (HR) = 6.8, 95%CI: 1.4-33.5, P = 0.019; NOMOF HR = 33.2, 95%CI: 9.4-117.3, P < 0.001] and BISAP score (HR = 2.5, 95%CI: 1.3-4.6, P = 0.005) (Figure 4).

| Variables | Died (n = 15) | Survived (n = 136) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 47 (39, 61) | 47 (35, 61) | 1.1 (0.9-1.1) | 0.497 | ||

| Male | 8 (53.3) | 68 (50) | 1.1 (0.4-3.3) | 0.807 | ||

| BISAP score, median (IQR) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (2, 3) | 3.3 (1.6-6.8) | 0.002a | 4.0 (1.3-12.0) | 0.013a |

| CTSI score, median (IQR) | 8 (8, 10) | 4 (4, 6) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) | < 0.001a | ||

| IPN | 12 (80.0) | 40 (29.4) | 9.6 (2.6-35.9) | 0.001a | ||

| OPN | 4 (26.7) | 4 (2.9) | 12.0 (2.6-54.7) | 0.001a | ||

| MC | 13 (86.7) | 26 (19.1) | 27.5 (5.8-129.4) | < 0.001a | 13.2 (2.1-83.5) | 0.006a |

| MOF on admission | 10 (66.7) | 30 (22.1) | 7.1 (2.2-22.3) | 0.001a | ||

| OF duration > 2 weeks | 12 (80.0) | 34 (25) | 12.0 (3.2-45.1) | < 0.001a | ||

| NOOF | 13 (86.7) | 25 (18.4) | 28.9 (6.1-136.1) | < 0.001a | 7.5 (1.3-42.6) | 0.024a |

The baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. After adjusting for sex, age, BISAP score, CTSI score, IPN, major complications, MOF on admission, and OF duration > 2 weeks in a binary multivariable logistic regression model (Supplementary Table 3), only NOOF remained an independent risk factor (OR = 19.3, 95%CI: 2.3-126.3, P = 0.006). Similarly, in a Cox regression analysis of 90-day mortality, after adjusting for the same set of covariates, NOSOF (HR = 9.9, 95%CI: 1.0-95.3, P = 0.047), NOMOF (HR = 43.7, 95%CI: 5.6-341.5, P < 0.001), and BISAP score (HR = 2.2, 95%CI: 1.0-4.9, P = 0.001) were identified as independent risk factors. To account for discharge as a competing risk, we further performed a competing risk analysis. The results of the cause-specific and Fine-Gray proportional-hazards models were broadly consistent with those obtained from the Cox model (Supplementary Table 4).

This single-center retrospective cohort study identified new-onset POF and BISAP score as independent predictors of in-hospital and 90-day mortality. A significantly higher mortality rate was observed in the high-risk subgroup, which was characterized by the longest duration of organ dysfunction and intensive supportive care. Earlier research suggested that AP mortality has a two-peak progression: The early phase (≤ 1 week) resulting from SIRS and the late phase (> 1 week) primarily due to IPN[11]. However, this classic biphasic pattern cannot be observed clinically, which may be attributed to advancements in supportive care and targeted drainage strategies for pancreatic necrosis[16-19].

The occurrence and duration of OF and IPN are currently recognized as indicators of AP severity under the Revised Atlanta Classification and Determinant-Based Classification[11,20]. However, the relationship between OF, IPN, and mortality in patients with AP remains unclear. A prospective multicenter study of 1655 patients with AP across 23 hospitals in Spain revealed that POF was the most significant determinant of mortality. In the presence of POF, IPN is associated with morbidity rather than mortality[21]. However, in the ICU setting, a global observational study of 374 patients with SAP in 46 ICUs found that POF with IPN had the highest mortality risk (59.09%) compared with POF without IPN (41.46%)[22].

The role of OF is well established, but the prognostic contribution of IPN requires further clarification. In our study, after including NOOF in the multivariate regression analysis, the significant impact of IPN on adverse outcomes attenuated. Combined with our findings, we can infer that the positive results of previous studies on the association between IPN and adverse outcomes may be attributed to the development of NOOF secondary to initial POF during the later stages of the disease, a point that has been overlooked but is highly significant. Understanding the interplay among OF, IPN, and adverse outcomes is essential for accurate severity assessment, guiding clinical decisions regarding infectious necrotic material drainage, and improving patient counselling.

Building on their detailed characterization of OF, Schepers et al[23] performed a post-hoc analysis of 639 patients with necrotizing pancreatitis in the Netherlands and found that the timing, duration, and coexistence of IPN were not associated with mortality; however, an increase in the number of concurrent OFs significantly increased mortality. Similar findings were observed in a large Chinese cohort of over 3000 patients with AP, in which prolonged OF (≥ 2 weeks) was associated with mortality[24]. In addition to the number and duration of organ dysfunction, the timing of occurrence is also important. In our OF group, a significant proportion of patients experienced either MOF (n = 19, 16.8%) or POF lasting > 2 weeks (n = 17, 15%). The onset of MOF during the course of AP and the prolongation of OF may be influenced by the intensity and persistence of the initial SIRS, and supportive therapy may mitigate these adverse effects. After adjusting for NOOF, POF lasting > 2 weeks did not significantly affect mortality, which is consistent with the results of a recent global multicenter observational study[25]. Additionally, in our results, the incidence of NOMOF, rather than initial MOF, was significantly associated with mortality, reflecting the importance of the timing of OF occurrence. This conclusion further enriches the theoretical understanding of the adverse effects of OF in patients with AP.

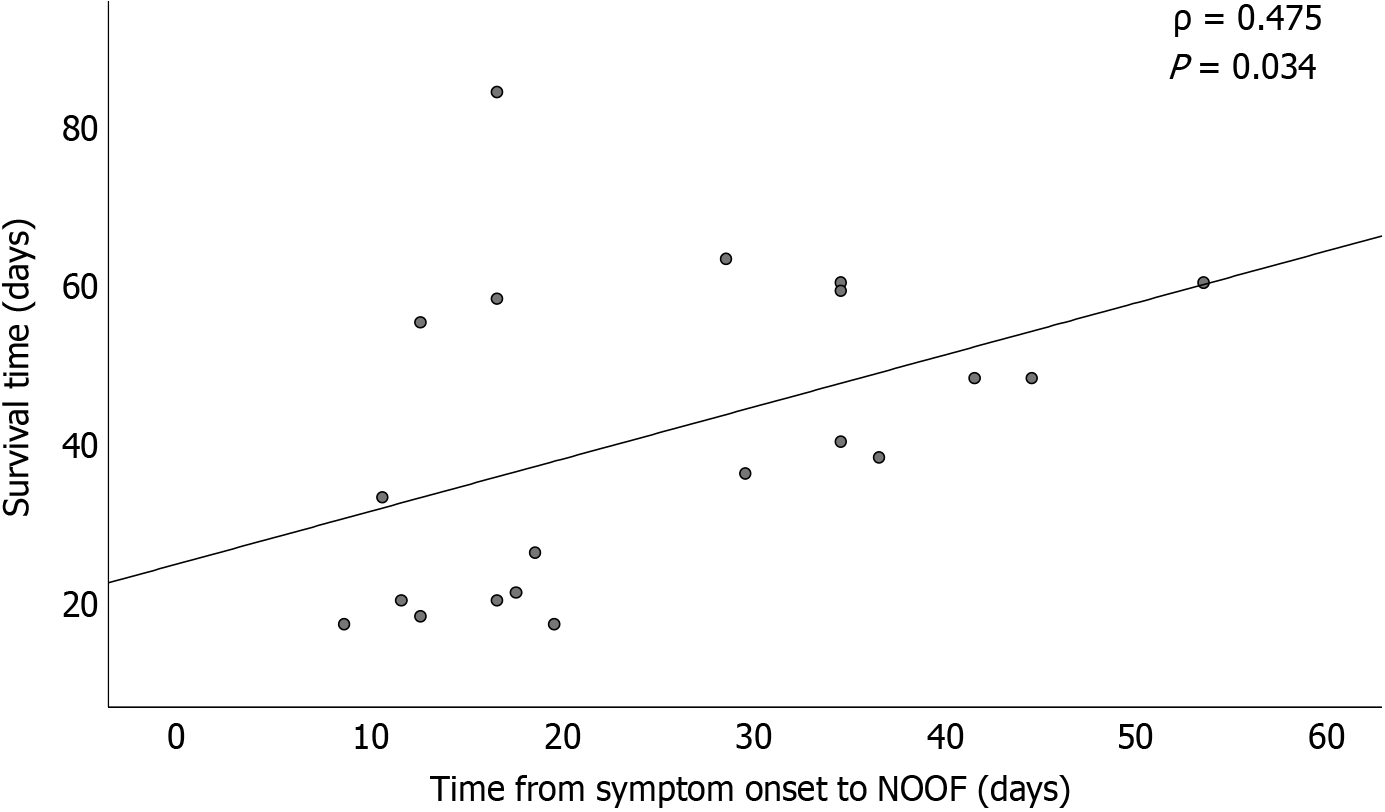

The research populations of previous studies were different, and the conclusions were controversial. In our cohort with at least one episode of POF, after adjusting for initial MOF, POF duration (> 2 weeks), and IPN, NOOF remained an independent risk factor for mortality. This finding suggests that, based on a POF event, late-onset, new-onset, and persistent MOF may cause the most adverse effects in this population. Moreover, Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation between NOOF onset time and 90-day survival (Figure 5), indicating that earlier NOOF may be more detrimental.

Of note, both major complications and BISAP score were significantly associated with adverse outcomes. Major complications often involve alterations in anatomical structures and/or physiological functions, necessitating active intervention or surgical management. These complications may lead to early organ dysfunction or NOOF, thereby increasing the risk of in-hospital mortality. NOMOF has been deemed a severe complication in previous studies[12,26]. However, the causes of NOOF are often complex, multifactorial, and difficult to determine[23]. The BISAP is a validated clinical scoring system comprising five assessment criteria: Serum creatinine level, altered mental status, SIRS score, age, and pleural effusion. It effectively identifies patients with AP at high risk of in-hospital mortality[27], with its prognostic value well-established in clinical practice. While other scoring systems (e.g., Ranson criteria and APACHE II) have also been used, BISAP is noted for its simplicity and clinical utility and is currently used as a comparator in AP prognostic studies[28,29]. However, its application may be limited by the need for timely assessment of specific parameters (e.g., pleural effusion) within 24 hours[30].

The current study has some limitations. First, the single-center retrospective design may have introduced referral and confounding biases, and the small sample size may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the single-center nature of this study cannot capture the heterogeneity in clinical management across different regions, particularly late-phase intervention strategies, such as step-up drainage protocols, which are largely dependent on local standards of care. This limitation should be addressed in future prospective multicenter studies. Second, the wide confidence intervals around the large effect sizes reflect uncertainty in the estimates. Nevertheless, the consistency across multiple sensitivity analyses supports the robustness of our findings. Third, the suitability of modified Marshall scoring system for defining OF may be questioned, as it does not include patients receiving vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, or RRT[23]. Nevertheless, our study analyzed specific organ support durations across different groups (Figure 3), demonstrating the practical discriminative value of this scoring system in a real-world cohort. Fourth, the study did not include patients with newly diagnosed transient OF; nonetheless, the potential impact of such a subgroup may have been mitigated by the clinical features observed in the OF group. Lastly, disentangling the multifactorial causes of NOOF and determining their individual roles in its pathogenesis remain a significant clinical challenge. To address this challenge and clarify the complex causal pathways in SAP, we employed a directed acyclic graph to map the relationships between key variables and clinical outcomes (Supplementary Figure 1). This approach is essential for advancing patient care by informing targeted interventions.

In patients with SAP, we identified a new high-risk subgroup that requires attention. Newly emergent POF, particularly NOMOF, significantly increases mortality and warrants greater emphasis. These findings may play a pivotal role in future grading systems for the severity of pancreatitis and in the design of clinical trials. To facilitate the translation of our findings into clinical practice, we have included a clinical practice box (Figure 6) that summarizes the key actionable points for clinicians.

| 1. | Boxhoorn L, Voermans RP, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Verdonk RC, Boermeester MA, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:726-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 114.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Capurso G, Ponz de Leon Pisani R, Lauri G, Archibugi L, Hegyi P, Papachristou GI, Pandanaboyana S, Maisonneuve P, Arcidiacono PG, de-Madaria E. Clinical usefulness of scoring systems to predict severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis with pre and post-test probability assessment. United European Gastroenterol J. 2023;11:825-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Garg PK, Singh VP. Organ Failure Due to Systemic Injury in Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:2008-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Padhan RK, Jain S, Agarwal S, Harikrishnan S, Vadiraja P, Behera S, Jain SK, Dhingra R, Dash NR, Sahni P, Garg PK. Primary and Secondary Organ Failures Cause Mortality Differentially in Acute Pancreatitis and Should be Distinguished. Pancreas. 2018;47:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Keshavarz P, Azrumelashvili T, Yazdanpanah F, Nejati SF, Ebrahimian Sadabad F, Tarjan A, Bazyar A, Mizandari M. Percutaneous catheter drainage of pancreatic associated pathologies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2021;144:109978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bosscha K, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Cappendijk VC, Consten EC, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, Erkelens WG, van Goor H, van Grevenstein WMU, Haveman JW, Hofker SH, Jansen JM, Laméris JS, van Lienden KP, Meijssen MA, Mulder CJ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Poley JW, Quispel R, de Ridder RJ, Römkens TE, Scheepers JJ, Schepers NJ, Schwartz MP, Seerden T, Spanier BWM, Straathof JWA, Strijker M, Timmer R, Venneman NG, Vleggaar FP, Voermans RP, Witteman BJ, Gooszen HG, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 588] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 63.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Luckhurst CM, El Hechi M, Elsharkawy AE, Eid AI, Maurer LR, Kaafarani HM, Thabet A, Forcione DG, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Lillemoe KD, Fagenholz PJ. Improved Mortality in Necrotizing Pancreatitis with a Multidisciplinary Minimally Invasive Step-Up Approach: Comparison with a Modern Open Necrosectomy Cohort. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:873-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Timmerhuis HC, van Dijk SM, Hollemans RA, Sperna Weiland CJ, Umans DS, Boxhoorn L, Hallensleben NH, van der Sluijs R, Brouwer L, van Duijvendijk P, Kager L, Kuiken S, Poley JW, de Ridder R, Römkens TEH, Quispel R, Schwartz MP, Tan ACITL, Venneman NG, Vleggaar FP, van Wanrooij RLJ, Witteman BJ, van Geenen EJ, Molenaar IQ, Bruno MJ, van Hooft JE, Besselink MG, Voermans RP, Bollen TL, Verdonk RC, van Santvoort HC; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Short-term and Long-term Outcomes of a Disruption and Disconnection of the Pancreatic Duct in Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Multicenter Cohort Study in 896 Patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:880-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu Z, Ke H, Xiong Y, Liu H, Yue M, Liu P. Gastrointestinal Fistulas in Necrotizing Pancreatitis Receiving a Step-Up Approach Incidence, Risk Factors, Outcomes and Treatment. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:5531-5543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1638-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1949] [Cited by in RCA: 1771] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4719] [Article Influence: 363.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 12. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM, Poley JW, van Ramshorst B, Vleggaar FP, Boermeester MA, Gooszen HG, Weusten BL, Timmer R; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tenner S, Vege SS, Sheth SG, Sauer B, Yang A, Conwell DL, Yadlapati RH, Gardner TB. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:419-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 104.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update: Management of Pancreatic Necrosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:67-75.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Zhang B, Gao T, Wang Y, Zhu H, Liu S, Chen M, Yu W, Zhu Z. A novel mini-invasive step-up approach for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis with extensive infected necrosis: A single center case series study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e33288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Crosignani A, Spina S, Marrazzo F, Cimbanassi S, Malbrain MLNG, Van Regenmortel N, Fumagalli R, Langer T. Intravenous fluid therapy in patients with severe acute pancreatitis admitted to the intensive care unit: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Podda M, Murzi V, Marongiu P, Di Martino M, De Simone B, Jayant K, Ortenzi M, Coccolini F, Sartelli M, Catena F, Ielpo B, Pisanu A. Effectiveness and safety of low molecular weight heparin in the management of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2024;19:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hollemans RA, Bakker OJ, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bosscha K, Bruno MJ, Buskens E, Dejong CH, van Duijvendijk P, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, van Goor H, van Grevenstein WM, van der Harst E, Heisterkamp J, Hesselink EJ, Hofker S, Houdijk AP, Karsten T, Kruyt PM, van Laarhoven CJ, Laméris JS, van Leeuwen MS, Manusama ER, Molenaar IQ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, van Ramshorst B, Roos D, Rosman C, Schaapherder AF, van der Schelling GP, Timmer R, Verdonk RC, de Wit RJ, Gooszen HG, Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Superiority of Step-up Approach vs Open Necrosectomy in Long-term Follow-up of Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1016-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Khizar H, Zhicheng H, Chenyu L, Yanhua W, Jianfeng Y. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic drainage versus percutaneous drainage for pancreatic fluid collection; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2023;55:2213898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dellinger EP, Forsmark CE, Layer P, Lévy P, Maraví-Poma E, Petrov MS, Shimosegawa T, Siriwardena AK, Uomo G, Whitcomb DC, Windsor JA; Pancreatitis Across Nations Clinical Research and Education Alliance (PANCREA). Determinant-based classification of acute pancreatitis severity: an international multidisciplinary consultation. Ann Surg. 2012;256:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Sternby H, Bolado F, Canaval-Zuleta HJ, Marra-López C, Hernando-Alonso AI, Del-Val-Antoñana A, García-Rayado G, Rivera-Irigoin R, Grau-García FJ, Oms L, Millastre-Bocos J, Pascual-Moreno I, Martínez-Ares D, Rodríguez-Oballe JA, López-Serrano A, Ruiz-Rebollo ML, Viejo-Almanzor A, González-de-la-Higuera B, Orive-Calzada A, Gómez-Anta I, Pamies-Guilabert J, Fernández-Gutiérrez-Del-Álamo F, Iranzo-González-Cruz I, Pérez-Muñante ME, Esteba MD, Pardillos-Tomé A, Zapater P, de-Madaria E. Determinants of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis: A Nation-wide Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2019;270:348-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zubia-Olaskoaga F, Maraví-Poma E, Urreta-Barallobre I, Ramírez-Puerta MR, Mourelo-Fariña M, Marcos-Neira MP; Epidemiology of Acute Pancreatitis in Intensive Care Medicine Study Group. Comparison Between Revised Atlanta Classification and Determinant-Based Classification for Acute Pancreatitis in Intensive Care Medicine. Why Do Not Use a Modified Determinant-Based Classification? Crit Care Med. 2016;44:910-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schepers NJ, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Ahmed Ali U, Bollen TL, Gooszen HG, van Santvoort HC, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Impact of characteristics of organ failure and infected necrosis on mortality in necrotising pancreatitis. Gut. 2019;68:1044-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shi N, Liu T, de la Iglesia-Garcia D, Deng L, Jin T, Lan L, Zhu P, Hu W, Zhou Z, Singh V, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Windsor J, Huang W, Xia Q, Sutton R. Duration of organ failure impacts mortality in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2020;69:604-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Machicado JD, Gougol A, Tan X, Gao X, Paragomi P, Pothoulakis I, Talukdar R, Kochhar R, Goenka MK, Gulla A, Gonzalez JA, Singh VK, Ferreira M, Stevens T, Barbu ST, Nawaz H, Gutierrez SC, Zarnescu NO, Capurso G, Easler JJ, Triantafyllou K, Pelaez-Luna M, Thakkar S, Ocampo C, de-Madaria E, Cote GA, Wu BU, Conwell DL, Hart PA, Tang G, Papachristou GI. Mortality in acute pancreatitis with persistent organ failure is determined by the number, type, and sequence of organ systems affected. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:139-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Timmer R, Laméris JS, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Harst E, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, van Leeuwen MS, Buskens E, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1078] [Article Influence: 67.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell DL, Banks PA. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1698-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 28. | Villasante S, Fernandes N, Perez M, Cordobés MA, Piella G, Martinez M, Gomez-Gavara C, Blanco L, Alberti P, Charco R, Pando E; Pancreatia Study Collaborators. Prediction of Severe Acute Pancreatitis at a Very Early Stage of the Disease Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques, Without Laboratory Data or Imaging Tests: The PANCREATIA Study. Ann Surg. 2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chang CH, Chen CJ, Ma YS, Shen YT, Sung MI, Hsu CC, Lin HJ, Chen ZC, Huang CC, Liu CF. Real-time artificial intelligence predicts adverse outcomes in acute pancreatitis in the emergency department: Comparison with clinical decision rule. Acad Emerg Med. 2024;31:149-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Song LJ, Xiao B. Medical imaging for pancreatic diseases: Prediction of severe acute pancreatitis complicated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:6206-6212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/