Published online Feb 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.113804

Revised: October 27, 2025

Accepted: December 9, 2025

Published online: February 14, 2026

Processing time: 151 Days and 22.8 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is among the most prevalent chronic liver conditions globally and is closely linked with a range of metabolic disorders. Recently, the high-protein diet (HPD) has garnered attention for its potential benefits in weight management and metabolic health; however, its impact on MASLD remains a subject of debate. This article provided a systematic review of epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and foundational research concerning the role of HPD in MASLD. It examined the mechanisms by which HPD influences liver metabolism, inflammatory responses, and gut mic

Core Tip: High-protein diets have dual effects on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, depending on protein source and amount. Plant-based proteins may benefit liver metabolism, inflammation, and gut microbiota, whereas excessive animal proteins could worsen outcomes. Patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease should favor plant proteins and limit animal proteins; personalized dietary strategies require further mechanistic research.

- Citation: Yin HY, You QH, Zhang WJ, Ji G, Dang YQ. High-protein diets and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A double-edged sword in liver health. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(6): 113804

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i6/113804.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.113804

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly referred to as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), encompasses a spectrum of liver disorders acquired through metabolic stress[1]. MASLD represents a substantial public health concern and is now acknowledged as the most widespread chronic liver disease worldwide, impacting over 30% of the adult population[2,3]. Histopathologically, MASLD manifests as a continuum of disease states, including metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), and associated fibrosis and cirrhosis[4]. The condition is intricately associated with various metabolic derangements, such as central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose tolerance. These metabolic disturbances not only exacerbate the progression of liver disease but also elevate the risk of developing other severe health complications, including cardiovascular diseases and specific malignancies[1,5]. Despite its increasing prevalence therapeutic options for MASLD remain limited beyond lifestyle interventions, underscoring the critical need for the development of effective pharmacological treatments and strategies[6,7].

Recent studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between diet quality, physical activity, and the prevalence of MASLD[8-11]. MASLD is characterized by inflammation, metabolic disturbances, and intestinal microbiota disorders, which result from hepatic steatosis caused by the accumulation of adipose tissue originating from the gastrointestinal tract and within hepatocytes[12]. The accumulation of lipids in the liver is primarily attributed to diets high in added sugars and saturated fats, leading to excessive lipid deposition[13]. Adherence to healthier dietary patterns has been associated with a reduced risk of MASLD with vegetables and whole grains being the primary contributors to this as

Within the general population of the United States, individuals with MASLD are more frequently adhering to special diets, suggesting an increased awareness and interest in utilizing dietary modifications to improve health outcomes. Certain nutritional factors, such as vitamins E and K, may offer protective effects against MASLD, but increased intake of macronutrients, including carbohydrates, cholesterol, total saturated fatty acids, and overall caloric intake, may facilitate the progression of MASLD[15]. Moreover, an unhealthy diet plays a crucial role in the development of obesity, a pro

High-protein diets (HPD) have gained modern popularity in the general population for its putative benefits in weight control and fat reduction. The International Nutrition Association recommends a protein intake of 0.8 g/kg/day for healthy adult individuals. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data indicate that current mean protein intakes in the United States already reach 1.2-1.4 g/kg/day, comfortably exceeding this benchmark[18]. Although there is no universally accepted definition for an HPD, most definitions delineate a range from 1.2 g/kg/day to 2.0

Nonetheless, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential adverse effects associated with HPD. High protein consumption may lead to intraglomerular hypertension, which can result in renal hyperfiltration, glomerular damage, and the onset of proteinuria. There exists a potential risk that prolonged high protein intake may contribute to the development of de novo chronic kidney disease (CKD)[23]. The recent Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes commentary clearly states that high animal protein is an independent risk for diabetes complicated with CKD, emphasizing that the source of protein is more important than the total amount[24]. Estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 is regarded by most guidelines as a “high-protein potential risk area,” and it is recommended to start protein restriction[18]. Furthermore, HPD has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk due to the activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) in macrophages that subsequently inhibits mitophagy[25]. Despite these concerns HPD can be beneficial for weight management and metabolic health enhancement. It is essential, however, to carefully balance these benefits against the potential risks, particularly for individuals with pre-existing conditions, and to customize dietary plans to meet individual needs.

Recent studies have indicated that a healthy diet combined with planned exercise constitutes the most fundamental treatment for most MASLD. Optimizing dietary composition, particularly protein intake, alongside increasing physical activity, has been shown to be advantageous for liver health and the management of metabolic complications. In light of this, the present article examined the pathogenesis and influencing factors of MASLD and reviewed recent research on the relationship between HPD and MASLD. The aim was to generate novel insight for the prevention and treatment of MASLD and to provide a foundation for precise nutritional intervention strategies.

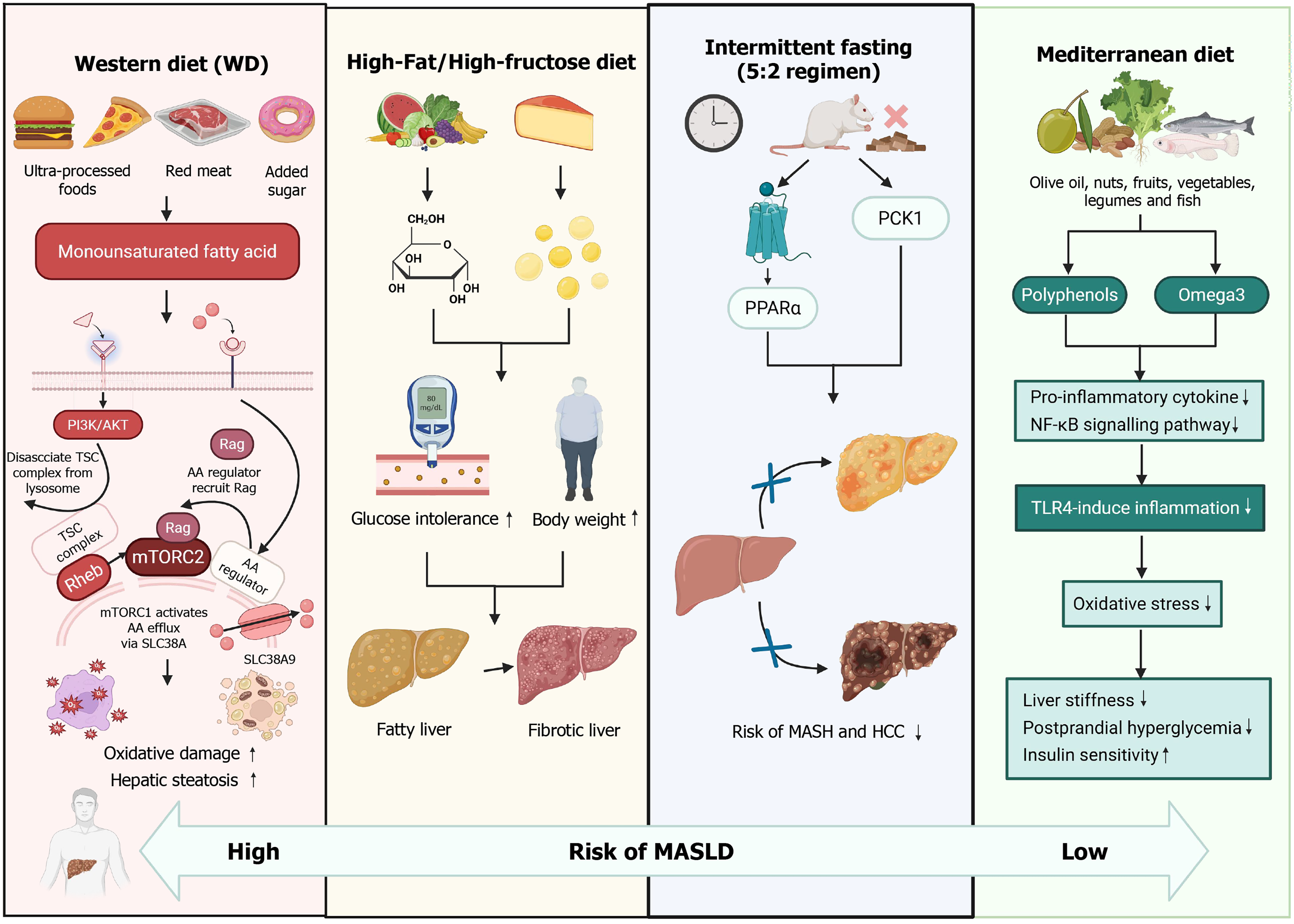

Currently, diverse dietary patterns have been identified to exert varying effects on MASLD. The Western diet, characterized by a high intake of processed foods, refined cereals, high-sugar products, high-fat dairy products, and processed meats, is correlated with an elevated risk of MASLD[26]. For example, research has demonstrated that a diet rich in fats and fructose results in increased body and liver weight, glucose intolerance, and liver abnormalities, which are indicative of a transitional state between fatty liver and liver fibrosis[27,28]. Additionally, the Western diet, which is high in monounsaturated fats, may exacerbate oxidative damage and hepatic steatosis during the early stages of MASLD, potentially contributing to its progression[29]. This dietary pattern is also associated with an increased production of proinflammatory cytokines and a reduction in anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Conversely, the traditional Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes the consumption of olive oil, nuts, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and fish while limiting the intake of red meat and sweets, has been demonstrated to be advantageous for patients with MASLD. It can significantly lower total cholesterol and liver stiffness, mitigate inflammation induced by oxidative damage, and attenuate toll-like receptor 4-mediated hepatic inflammation[30]. Insulin resistance is currently acknowledged as a fundamental pathogenic feature of MASLD and a critical contributor to the progression of hepatic inflammation[31]. The Mediterranean diet has been identified as the most effective dietary intervention for alleviating postprandial hyperglycemia and improving insulin sensitivity without necessitating weight loss[27]. Furthermore, research conducted by Yaskolka Meir et al[32] has demonstrated that the green-Mediterranean diet, characterized by reduced consumption of red and processed meats and increased intake of green plants and polyphenols, results in a two-fold reduction in intrahepatic fat compared with other healthful dietary approaches and decreases the prevalence of MASLD by 50%.

Another promising dietary approach is intermittent fasting, often termed “the next significant trend in weight management,” which is also known as periodic prolonged fasting or intermittent calorie restriction. Common variations of intermittent fasting involve fasting for up to 24 h once or twice a week with unrestricted eating on non-fasting days[32,33]. The 5:2 intermittent fasting regimen has been shown to ameliorate MASH and fibrosis while also reducing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma through the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1[34].

In terms of protein characteristics, the Western diet is predominantly characterized by a high intake of animal protein, primarily derived from processed meats and dairy products[35,36]. Conversely, the Mediterranean diet is recognized as a health-promoting dietary pattern, noted for its numerous health benefits. It is distinguished by the consumption of moderate amounts of fish and seafood, which are rich in omega-3 fatty acids and provide high-quality protein. Additionally, poultry and eggs are consumed in moderate quantities while red meat and processed meats are limited[37,38] (Figure 1).

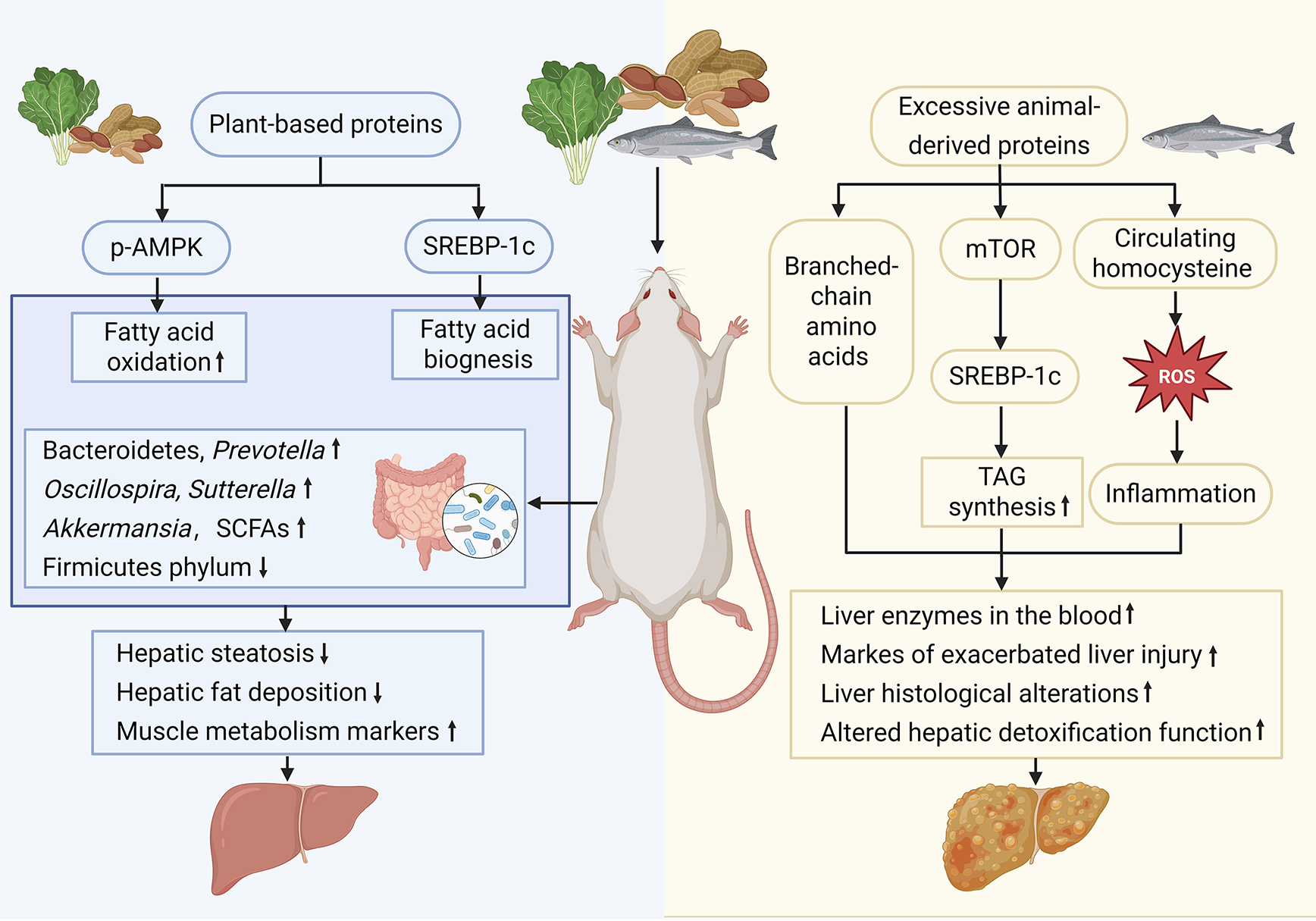

Recent animal studies have begun to clarify the double-sided role of dietary protein in MASLD. Over the past 10 years, experiments in genetically modified mice and obese rats have shown that precisely dosed high-protein regimens rapidly reduce hepatic lipid stores and improve systemic metabolism. Conversely, some research has revealed that feeding mice with protein intake beyond a threshold, even for as little as 2 weeks, unleashes macrophage and neutrophil activation, spikes circulating liver enzymes, and aggravates steatosis. Investigations using gnotobiotic and sequencing approaches further demonstrate that these dietary manipulations trigger immediate gut microbiota shifts, thereby modulating the microbiota-gut-liver axis and dictating whether the net effect is protection or progression of MASLD (Figure 2).

The latest experimental studies have highlighted the significant advantages of HPD in animal models of MASLD. For example, research by Santos-Sánchez et al[39] demonstrated that legume protein hydrolysate effectively reduces abdominal adiposity and ameliorates MASLD in ApoE(-/-) mice fed a Western diet. Similarly, plant-derived bioactive peptides and protein hydrolysates have been identified for their potential beneficial effects on MASLD-related parameters, likely due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and lipid-lowering properties[40]. Abbate et al[41] demonstrated that a 12-week administration of protein hydrolysates derived from anchovy waste significantly alleviates the severity of MASLD in ApoE-deficient mice. This finding reinforces the hypothesis that protein hydrolysates can positively influence liver health.

Furthermore, HPD in general has been shown to be more effective in reducing hepatic fat compared with low-protein diets. French et al[42] revealed that HPD effectively mitigates weight gain and food intake while reducing liver fat deposition and enhancing markers of muscle metabolism in obese Zucker rats. Protein derived from beans can diminish hepatic fat deposition and prevent MASLD, and the biological sex of mice determines the amount of beans in the diet required to prevent hepatic lipid accumulation[43]. Collectively, these studies underscore the potential of HPD and related compounds in managing MASLD in animal models, suggesting promising avenues for further research and potential therapeutic strategies for combating this metabolic disorder.

Other research has indicated that HPD may have adverse effects on MASLD. For instance, administering diets with exceptionally high protein content to mice for a duration of 2 weeks has been demonstrated to activate macrophages and neutrophils, subsequently resulting in a marked elevation of liver enzymes in the bloodstream and precipitating acute liver injury. This finding implies that HPD may pose a risk of liver damage and be detrimental to MASLD. Additionally, prolonged consumption of HPD has been observed to enhance pathways associated with liver triacylglycerol accumulation and exacerbate hepatic injury markers in rats, suggesting that sustained intake of HPD could contribute to liver damage and potentially aggravate MASLD[44].

Research conducted by Monteiro et al[45] has demonstrated that a diet rich in protein and low in carbohydrates induces cellular and histopathological damage in the livers of laboratory rodents, harming the liver and potentially worsening MASLD. Furthermore, Liao et al[46] identified that within the context of obesity, the upregulation of de novo lipogenesis is a critical feature of MASLD with amino acids playing a crucial role as a major carbon source for hepatic lipogenesis. Low-protein diets have been demonstrated to confer a range of benefits in obese mice, notably preventing excessive body weight gain and reducing hepatic lipid accumulation and subsequent liver damage. This evidence indicates that dietary protein intake may significantly influence the metabolic pathways involved in the development and progression of MASLD.

The relationship between amino acids and MASLD is intricate and multifaceted. Certain amino acids, such as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), have been shown to positively impact liver health. BCAAs have been employed in the treatment of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and have been found to ameliorate hepatic steatosis and liver injury in mice with MASH induced by a choline-deficient high-fat diet[47]. This suggests that BCAAs may play a protective role in certain liver diseases. Conversely, elevated levels of certain amino acids have been associated with an increased risk of liver disease.

For example, a meta-analysis has revealed that individuals with MASLD tend to exhibit higher serum homocysteine levels, which is correlated with a heightened risk of hyperhomocysteinemia, indicating that elevated homocysteine levels may be a risk factor for the development of MASLD[48]. Glutamine, an essential amino acid, has been shown to prevent hepatic lipid accumulation in mice on a high-fat diet by influencing lipolysis and oxidative stress. Zhang et al[49] found that glutamine improved lipid storage, liver damage, and oxidative stress in obese mice on a high-fat diet. However, while glutamine may prevent high-fat diet-induced MASLD in mice, it does not reverse the condition once established. These findings underscore the varied roles amino acids play in MASLD.

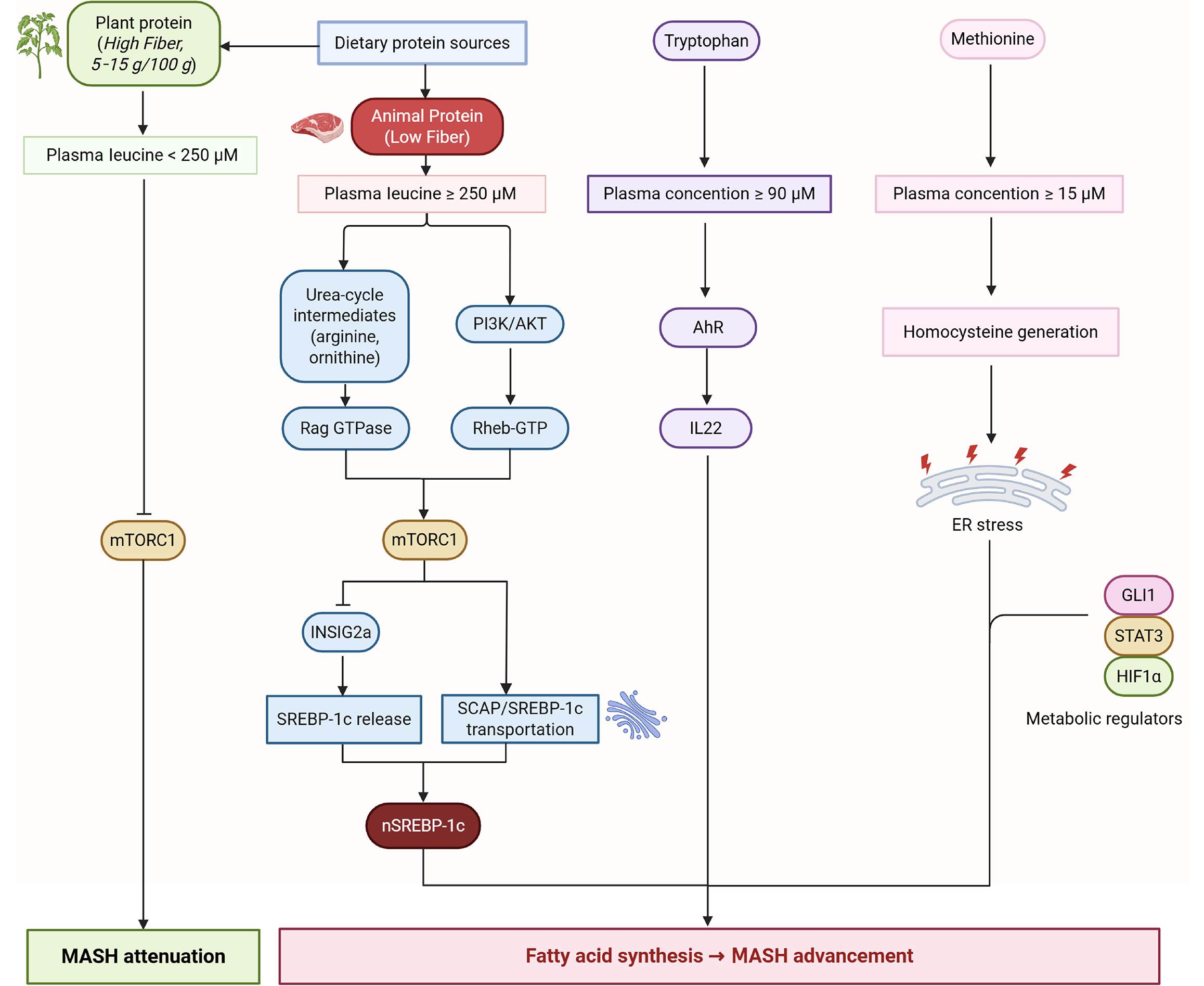

While amino acids like BCAAs and glutamine may offer protective effects, elevated levels of others, such as homocysteine, may increase disease risk. The latest research has found that amino acids are the main carbon source for liver fat production and are related to the following multiple pathways, such as leucine-mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)-sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), tryptophan-aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interleukin 22, and methionine-homocysteine-endoplasmic reticulum stress branches, etc.

For example, arginine or leucine is sufficient for mTORC1 lysosomal translocation and subsequent nuclear translocation of SREBP1c, leading to fatty acid synthesis in primary hepatocytes[50]. In addition, mTORC1 inhibition (rapamycin) can abolish insulin-induced maturation of SREBP1c and reduce hepatic triglycerides (TG) secretion[51]. Urea-cycle intermediates (arginine, ornithine) are not mere metabolites but mTORC1 agonists driving hepatocyte growth and lipid synthesis. mTORC1 is highly phosphorylated in early MASLD and is accompanied by upregulation of lipid synthesis genes. When entering the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis stage, mTORC1 has a certain protective effect on the initiation and progression of MASH[52].

Additionally, plant protein foods come bundled with 5-15 g fiber/100 g, acting as a major positive confounder. A sensitivity analysis in the 2025 cohort showed the apparent diabetes protection by plant protein lost significance after additionally adjusting for fiber intake[53]. Cellulose can affect the intestinal absorption process. Even if the same amount of leucine is consumed compared with a meal high in animal protein, usually with extremely low fiber, a plant-based protein meal may not be able to rapidly increase the plasma leucine concentration to the threshold for activating mTORC1 in a short period of time. Further research is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which amino acids affect liver health and to explore their potential therapeutic applications in MASLD management (Figure 3).

Quantitative and qualitative alterations in the gut microbiota are crucial determinants in the onset and progression of MASLD[54-56]. Animal studies utilizing various microbiome-sequencing platforms and MASLD diagnostic tools have consistently supported the causal involvement of the intestinal microbiota in hepatic steatosis[57]. In a controlled study conducted by Liu et al[58], rats fed an HPD showed a notable increase in Bacteroidetes, Prevotella, Oscillospira, and Sutterella along with a concurrent decrease in the Firmicutes phylum. Interestingly, hepatic steatosis induced by high-fat and high-sugar diets was independent of total caloric intake, suggesting that these compositional changes are mechanistic drivers of MASLD pathogenesis.

Plant protein is usually consumed together with high fiber and resistant starch. These components are the main driving factors for the enrichment of beneficial bacteria such as Bacteroidetes. A diet pattern that increases plant intake promotes changes in the intestinal flora[59]. Shi et al[60] demonstrated that a high-protein quinoa-enriched yogurt restored gut microbial equilibrium, activated the microbiome-gut-liver axis, and subsequently mitigated hepatic steatosis in MASLD by inhibiting lipogenesis and enhancing fatty acid oxidation. Furthermore, these dietary interventions are believed to exert protective effects through microbiome-derived metabolites that function as epigenetic effectors, influencing intestinal permeability, insulin signaling pathways, and immune responses, thereby mitigating the progression of MASLD[61]. Cumulatively, emerging evidence suggests that targeted dietary interventions involving specific micronutrients or bioactive compounds can alter gut microbial composition, thereby attenuating the disease trajectory of MASLD.

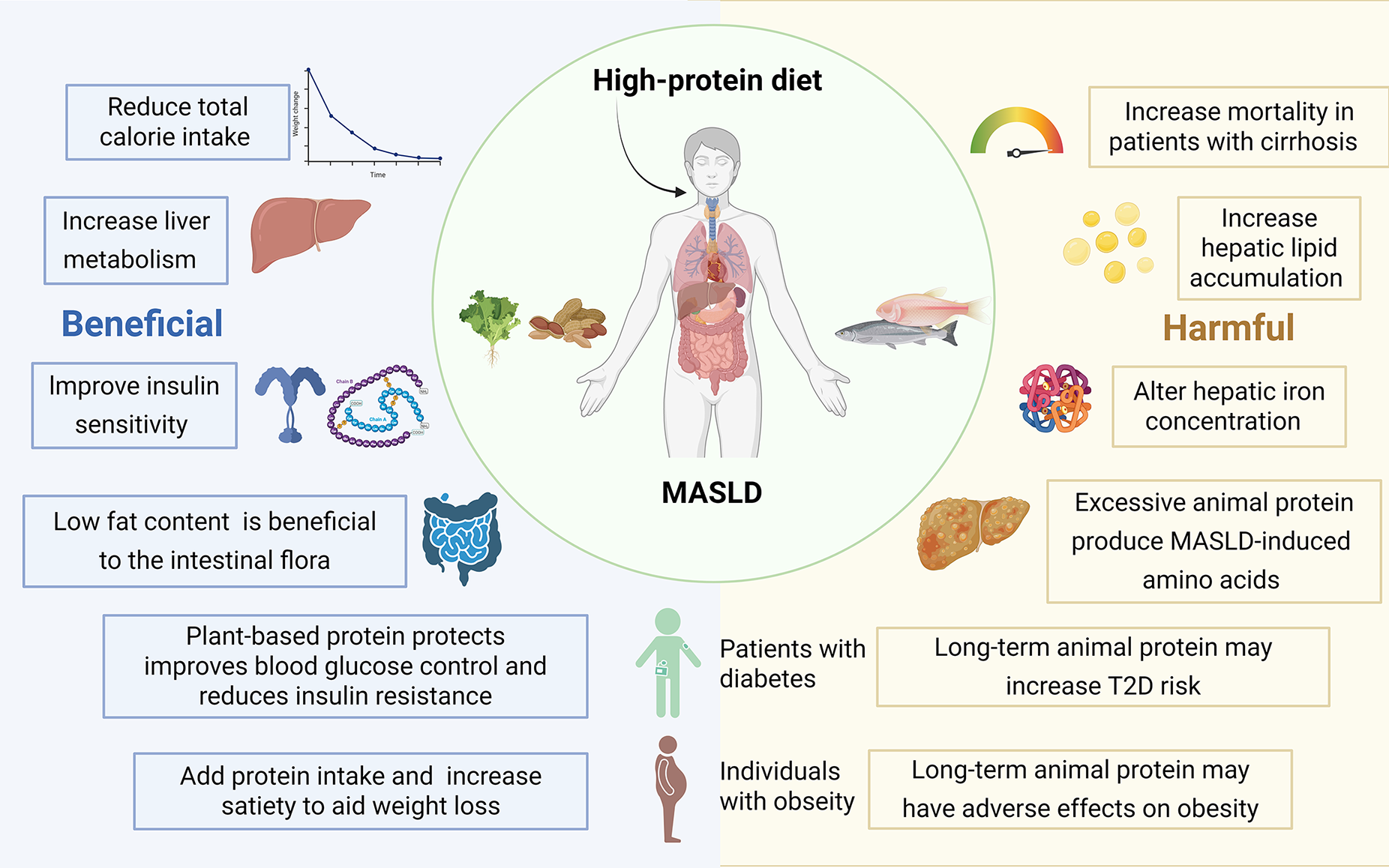

Rapidly expanding clinical evidence now frames dietary protein as both ally and adversary in MASLD. Across randomized controlled trials and prospective cohorts, higher-protein diets, especially those rich in plant or dairy sources, consistently reduce hepatic fat, preserve lean mass, and improve glycemic control. Yet when the dominant sources shift toward processed red meats and specific amino-acid profiles, the same macronutrient intensifies histological activity, necroinflammation, and hepatic iron dysregulation. Importantly, it appears to be tied less to absolute quantity than to quality, highlighting the need for a deliberate, source-focused strategy when leveraging protein to prevent or manage MASLD (Figure 4).

A considerable body of evidence from human studies indicates that HPD may have beneficial effects on MASLD. For example, a randomized controlled trial by Feng et al[62] proved that diets with high protein and lower carbohydrate could contribute to reducing liver steatosis and MASLD. A multicenter randomized controlled trial conducted in China[63] demonstrated that compared with a normal or low-protein diet HPD significantly reduced liver fat content, offering additional benefits for MASLD outcomes. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that excessive protein intake may also lead to elevated serum creatinine levels.

A case-control study by Chaturvedi et al[64] confirmed that a protein-rich diet provided a protective effect against MASLD. This finding suggests that increasing protein intake in the daily diet may serve as a preventive measure against the development of MASLD. Daftari et al[65] conducted a prospective cohort study and demonstrated that a higher intake of total protein and milk protein, coupled with a lower intake of animal protein, was associated with a reduced risk of mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. This finding underscores the significance of protein type, suggesting that plant-based and dairy proteins may confer greater benefits than animal proteins.

In an analysis of individuals aged 40-69 years, Lee et al[66] identified a significant negative correlation between higher dairy protein intake and the risk of developing MASLD in both males and females. Further investigation indicated that regular consumption of milk and other dairy products may contribute positively to MASLD prevention. Moreover, HPD was found to be more effective in reducing hepatic fat compared with a low-protein diet despite lower levels of autophagy and fibroblast growth factor 21. The data suggest that this reduction in liver fat is primarily attributable to the suppression of fat uptake and lipid biosynthesis pathways[67].

A randomized controlled trial revealed that a protein-rich diet was associated with the maintenance of lean body mass and a reduction in hepatic lipid accumulation[68]. The evidence indicates that HPD may be instrumental in preserving muscle mass while reducing liver fat deposition, thereby benefiting metabolic regulation in individuals with MASLD. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial involving individuals with type 2 diabetes who maintained stable body weight demonstrated that a low-carbohydrate, HPD significantly improved glycemic control as reflected by enhanced glycated hemoglobin levels while simultaneously decreasing liver fat accumulation[69].

A case-control study by Khazaei et al[70] found that a higher proportional contribution of dietary protein to total energy intake was associated with lower MASLD risk, and this inverse gradient was accentuated when the incremental protein was derived predominantly from plant rather than animal sources. In a prospective study of individuals with type 2 diabetes, it was found that diets high in protein, regardless of whether the protein was derived from animal or plant sources, substantially reduced liver fat content independently of body weight changes. Additionally, these HPDs were associated with a decrease in markers indicative of hepatic necroinflammation[71]. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of HPD to play a pivotal role in the management of MASLD by mitigating liver fat accumulation and enhancing metabolic control.

The relationship between HPD and MASLD is characterized by complexities and potential adverse effects. Empirical evidence suggests that a high protein intake, particularly when it constitutes 17.3% or more of daily caloric consumption, is associated with increased histological disease activity in patients with MASLD. This association is primarily influenced by specific amino acids, including serine, glycine, arginine, proline, phenylalanine, and methionine[72]. Research conducted by Wehmeyer et al[73] indicated that MASLD was more strongly correlated with an overall excessive caloric intake rather than a specific dietary pattern. Notably, individuals with MASLD tended to consume a greater amount of protein per 1000 kcal of energy intake compared with those without the condition. This observation implies that while dietary composition is significant, the quantity of protein intake also plays a crucial role in the onset and progression of MASLD.

Furthermore, the source of animal protein appears to have varying effects on liver health in individuals with MASLD and obesity. Specifically, the consumption of processed meats has been associated with alterations in hepatic iron concentration, which may have deleterious effects. In contrast, the consumption of fish has been linked to enhanced ferritin levels, which are advantageous for liver health. These findings highlight the necessity of considering not only the quantity but also the quality and type of protein sources in the diet when assessing their impact on MASLD[74]. In conclusion, although HPD may confer certain benefits, it can also lead to negative outcomes in individuals with MASLD, particularly when consumed in excess or derived from less healthy sources. Therefore, a balanced and judicious approach to protein intake is crucial in managing and mitigating the risks associated with this metabolic condition.

The type of protein consumed appears to significantly influence the development and progression of MASLD. An international multidisciplinary expert consensus recommends that patients with MASLD should prioritize the consumption of healthy protein sources, primarily from plants while reducing the intake of red meat and processed meats[75]. This recommendation is corroborated by a case-control study that identified a significant association between plant protein intake and a reduced risk of MASLD, whereas increased meat protein intake was positively correlated with a higher risk[70]. Further evidence is provided by a comprehensive cross-sectional study conducted on the general adult population in the Netherlands in which Rietman et al[76] identified a negative correlation between plant protein intake and the characteristics of MASLD. Conversely, the intake of animal protein was positively associated with increased lipid accumulation in the liver, indicating that the dietary source of protein may differentially affect liver health.

In a separate cross-sectional study involving 505 participants aged 6 years to 18 years, a higher consumption of animal protein was significantly correlated with an increased likelihood of developing MASLD in pediatric and adolescent populations. In contrast, a greater intake of plant-based protein was significantly associated with a reduced risk of MASLD. Notably, this study did not find any significant association between total protein intake and the risk of MASLD, underscoring the importance of the type of protein consumed[77].

Furthermore, the intake of specific dietary amino acids, such as aromatic amino acids, BCAAs, and sulfur amino acids, has been shown to potentially exert a negative impact on the liver condition of individuals with MASLD, underscoring the importance of not only the type of protein but also the specific amino acid composition in the diet[78]. In conclusion, the evidence indicates that plant-based proteins may confer protective effects against MASLD, whereas animal proteins, particularly those derived from red and processed meats, may elevate the risk. Consequently, dietary modifications that prioritize plant-based protein sources and restrict the consumption of animal proteins, especially those rich in saturated fats, could be advantageous for the prevention and management of MASLD.

The preceding sections have thoroughly analyzed the association between diet and MASLD, demonstrating that both the quantity and source of protein intake are critical factors influencing this condition. Both excessive and insufficient protein consumption can potentially have detrimental effects on liver health. Furthermore, the source of protein is of significant importance as plant-based proteins generally appear to be more advantageous than animal proteins, especially those from red and processed meats[79]. The specific amino acid composition of proteins adds complexity to this issue with certain amino acids, such as BCAAs and glutamine, offering protective benefits for liver health, whereas elevated levels of others, such as homocysteine, can increase the risk of disease. Furthermore, the effects of various protein types differ across populations. For example, in individuals with obesity, low-protein diets have been shown to reduce hepatic lipid accumulation and liver damage. Conversely, in individuals with type 2 diabetes, HPD can significantly improve glycemic control and decrease liver fat accumulation.

These complex findings suggest that tailored dietary recommendations are warranted. For individuals at risk of or suffering from MASLD, HPD may be beneficial, particularly if the protein is primarily derived from plant sources. Plant-based proteins, such as those found in legumes, have been shown to exert favorable effects on liver health and overall metabolic regulation[80-82]. This recommendation is further substantiated by evidence indicating that plant-based proteins can reduce the risk of CKD, a condition frequently associated with MASLD. Research has demonstrated that substituting one serving of red meat with plant-based proteins like beans is linked to a 31.0%-62.4% reduction in the risk of developing CKD[83].

Additionally, MASLD is a complex condition influenced by a multitude of risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, gut microbial dysbiosis, and genetic predispositions[84,85]. Obesity, particularly characterized by visceral adiposity, constitutes a major risk factor for MASLD due to its association with various metabolic disturbances[86]. Insulin resistance plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of MASLD; when the body fails to utilize insulin effectively, it results in elevated blood glucose levels, contributing to hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation[87]. The presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus further exacerbates the risk of MASLD as chronic hyperglycemia and related metabolic abnormalities inherent in diabetes promote the development of fatty liver[88]. Additionally, metabolic syndrome, which encompasses a constellation of conditions such as obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, markedly elevates the risk of MASLD[89,90]. Dyslipidemia, characterized by elevated TG, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased small, dense low-density lipoprotein particles, is prevalent in MASLD and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, thereby contributing to liver fat deposition[91,92].

Sarcopenia, characterized by the loss of muscle mass and strength, constitutes an independent risk factor for MASLD. Notably, sarcopenic obesity is particularly associated with an elevated risk of MASLD compared with obesity alone[93,94]. Additionally, CKD is correlated with an increased risk of MASLD, potentially due to shared metabolic abnormalities and the influence of renal dysfunction on systemic metabolism[95]. Certain ethnic groups, such as South Asians, may exhibit a heightened predisposition to MASLD, attributable to genetic factors and lifestyle patterns[96]. Consequently, when evaluating dietary interventions for patients with MASLD, it is imperative to consider other coexisting medical conditions, advocating for personalized dietary regimens.

Personalized nutrition (PN) is transitioning from a conceptual framework to clinical application by integrating multilayered individual data to provide dietary recommendations that surpass generic guidelines[97,98]. For example, a recently conducted 12-week randomized controlled trial involving Chinese adults with overweight or obesity demonstrated that a PN intervention resulted in significantly greater reductions in body mass index, body fat percentage, waist circumference, and atherogenic lipids, mediated largely by improved diet quality and higher physical-activity levels[99].

Recent evidence highlighted the critical need for PN interventions in the management of MASLD. Vrentzos et al[100] argued that the efficacy of nutraceuticals was significantly influenced by host genetics, microbiome composition, and metabolic phenotype. Consequently, they advocated for the abandonment of “one-size-fits-all” approaches in favor of precision strategies. Technological advancements are enhancing the precision and applicability of these models. Innovations such as next-generation sequencing and point-of-care microfluidic genotyping facilitate the rapid and cost-effective identification of genetic variants pertinent to nutrient metabolism. Concurrently, artificial intelligence systems integrate these genetic variants with phenotypic and lifestyle data to generate personalized meal plans[101,102]. Clinical Nutritional Information Systems are being implemented in healthcare settings to standardize these processes, alleviate documentation burdens, and ensure real-time updates as patient parameters evolve.

Metabotyping approaches, which categorize individuals based on comprehensive profiles of metabolomics, microbiome, and habitual diet, enable the precise prevention of cardiometabolic diseases without necessarily revealing genetic risks[103,104]. Defining safe and effective protein quantities will require large, well-designed randomized controlled trials followed by meta-analyses that incorporate rigorous quality assessment. Future work should prioritize such randomized controlled trials, synthesize their findings through systematic reviews, and then integrate nutrigenomics, microbiome profiling, and real-time metabolomics to build adaptive algorithms capable of matching each patient with MASLD with the most effective nutraceutical combination and dietary pattern[105].

While this review provided a consolidated map of the research on HPD and MASLD over the past 5 years, its scope and interpretation are subject to inherent constraints. First, due to differences among research in protein thresholds (1.2-2.0

The existing body of evidence presents a somewhat inconsistent narrative concerning the influence of protein intake on MASLD. Several studies have underscored the advantages of plant-based proteins, whereas other research suggests that excessive protein consumption, irrespective of its source, may have adverse effects. Consequently, it is imperative to ascertain an optimal level of protein intake that maximizes benefits while minimizing potential risks. Animal studies could be particularly instrumental in this context as they may clarify whether the deleterious effects of HPD are dose dependent.

Further research into the specific mechanisms by which various types of proteins and amino acids affect liver health is also necessary. This research could include examining the interactions between proteins and metabolic pathways as well as the potential involvement of gut microbiota in mediating these effects. For instance, plant protein shows promise against MASLD, and future work should pinpoint the bioactive peptides responsible. Given the variable impacts of protein intake across different populations, future research should also emphasize personalized dietary recommendations based on individual characteristics such as obesity status, presence of diabetes, and genetic predispositions. For example, the current definition of HPD remains ambiguous with wide variation in its thresholds. Future animal and clinical studies could incorporate a graded series of protein levels to clarify how dietary protein concentration influences MASLD risk. By addressing these research gaps, we can develop more effective and tailored dietary strategies for the prevention and management of MASLD.

| 1. | Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut. 2024;73:691-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 133.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chan WK, Chuah KH, Rajaram RB, Lim LL, Ratnasingam J, Vethakkan SR. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2023;32:197-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 149.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Han SK, Baik SK, Kim MY. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Definition and subtypes. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S5-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Powell EE, Wong VW, Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet. 2021;397:2212-2224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 1932] [Article Influence: 386.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 5. | Hutchison AL, Tavaglione F, Romeo S, Charlton M. Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1524-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ciardullo S, Muraca E, Vergani M, Invernizzi P, Perseghin G. Advancements in pharmacological treatment of NAFLD/MASLD: a focus on metabolic and liver-targeted interventions. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2024;12:goae029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huttasch M, Roden M, Kahl S. Obesity and MASLD: Is weight loss the (only) key to treat metabolic liver disease? Metabolism. 2024;157:155937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Heredia NI, Zhang X, Balakrishnan M, Daniel CR, Hwang JP, McNeill LH, Thrift AP. Physical activity and diet quality in relation to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A cross-sectional study in a representative sample of U.S. adults using NHANES 2017-2018. Prev Med. 2022;154:106903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang P, Liu J, Lee A, Tsaur I, Ohira M, Duong V, Vo N, Watari K, Su H, Kim JY, Gu L, Zhu M, Shalapour S, Hosseini M, Bandyopadhyay G, Zeng S, Llorente C, Zhao HN, Lamichhane S, Mohan S, Dorrestein PC, Olefsky JM, Schnabl B, Soroosh P, Karin M. IL-22 resolves MASLD via enterocyte STAT3 restoration of diet-perturbed intestinal homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2024;36:2341-2354.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tessier AJ, Wang F, Korat AA, Eliassen AH, Chavarro J, Grodstein F, Li J, Liang L, Willett WC, Sun Q, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Guasch-Ferré M. Optimal dietary patterns for healthy aging. Nat Med. 2025;31:1644-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Cho E, Kim S, Kim S, Kim JY, Kim HJ, Go Y, Lee YJ, Lee H, Gil S, Yoon SK, Chu K. The Effect of Mobile Lifestyle Intervention Combined with High-Protein Meal Replacement on Liver Function in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2024;16:2254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu J, Li C, Yang Y, Li J, Sun X, Zhang Y, Liu R, Chen F, Li X. Special correlation between diet and MASLD: positive or negative? Cell Biosci. 2025;15:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1658] [Cited by in RCA: 1781] [Article Influence: 593.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang X, Gan D, Fan Y, Fu Q, He C, Liu W, Li F, Ma L, Wang M, Zhang W. The Associations between Healthy Eating Patterns and Risk of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients. 2024;16:1956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nemer M, Osman F, Said A. Dietary macro and micronutrients associated with MASLD: Analysis of a national US cohort database. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29:101491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sun B, Ding X, Tan J, Zhang J, Chu X, Zhang S, Liu S, Zhao Z, Xuan S, Xin Y, Zhuang L. TM6SF2 E167K variant decreases PNPLA3-mediated PUFA transfer to promote hepatic steatosis and injury in MASLD. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2024;30:863-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lambert JE, Ramos-Roman MA, Valdez MJ, Browning JD, Rogers T, Parks EJ. Weight loss in MASLD restores the balance of liver fatty acid sources. J Clin Invest. 2025;135:e174233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ko GJ, Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Joshi S. The Effects of High-Protein Diets on Kidney Health and Longevity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1667-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Simonson M, Boirie Y, Guillet C. Protein, amino acids and obesity treatment. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2020;21:341-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cava E, Yeat NC, Mittendorfer B. Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:511-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moon J, Koh G. Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced Weight Loss. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2020;29:166-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tettamanzi F, Bagnardi V, Louca P, Nogal A, Monti GS, Mambrini SP, Lucchetti E, Maestrini S, Mazza S, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Scacchi M, Valdes AM, Invitti C, Menni C. A High Protein Diet Is More Effective in Improving Insulin Resistance and Glycemic Variability Compared to a Mediterranean Diet-A Cross-Over Controlled Inpatient Dietary Study. Nutrients. 2021;13:4380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kramer HM, Fouque D. High-protein diet is bad for kidney health: unleashing the taboo. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cheng Y, Zheng G, Song Z, Zhang G, Rao X, Zeng T. Association between dietary protein intake and risk of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1408424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang X, Sergin I, Evans TD, Jeong SJ, Rodriguez-Velez A, Kapoor D, Chen S, Song E, Holloway KB, Crowley JR, Epelman S, Weihl CC, Diwan A, Fan D, Mittendorfer B, Stitziel NO, Schilling JD, Lodhi IJ, Razani B. High-protein diets increase cardiovascular risk by activating macrophage mTOR to suppress mitophagy. Nat Metab. 2020;2:110-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lin M, Long J, Li W, Yang C, Loughran P, O'Doherty R, Billiar TR, Deng M, Scott MJ. Hepatocyte high-mobility group box 1 protects against steatosis and cellular stress during high fat diet feeding. Mol Med. 2020;26:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mambrini SP, Grillo A, Colosimo S, Zarpellon F, Pozzi G, Furlan D, Amodeo G, Bertoli S. Diet and physical exercise as key players to tackle MASLD through improvement of insulin resistance and metabolic flexibility. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1426551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bozzetto L, Annuzzi G, Ragucci M, Di Donato O, Della Pepa G, Della Corte G, Griffo E, Anniballi G, Giacco A, Mancini M, Rivellese AA. Insulin resistance, postprandial GLP-1 and adaptive immunity are the main predictors of NAFLD in a homogeneous population at high cardiovascular risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26:623-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Simoes ICM, Karkucinska-Wieckowska A, Janikiewicz J, Szymanska S, Pronicki M, Dobrzyn P, Dabrowski M, Dobrzyn A, Oliveira PJ, Zischka H, Potes Y, Wieckowski MR. Western Diet Causes Obesity-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Development by Differentially Compromising the Autophagic Response. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9:995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kwon YJ, Choi JE, Hong KW, Lee JW. Interplay of Mediterranean-diet adherence, genetic factors, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease risk in Korea. J Transl Med. 2024;22:591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsitsou S, Bali T, Adamantou M, Saridaki A, Poulia KA, Karagiannakis DS, Papakonstantinou E, Cholongitas E. Effects of a 12-Week Mediterranean-Type Time-Restricted Feeding Protocol in Patients With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Randomised Controlled Trial-The 'CHRONO-NAFLD Project'. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61:1290-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yaskolka Meir A, Rinott E, Tsaban G, Zelicha H, Kaplan A, Rosen P, Shelef I, Youngster I, Shalev A, Blüher M, Ceglarek U, Stumvoll M, Tuohy K, Diotallevi C, Vrhovsek U, Hu F, Stampfer M, Shai I. Effect of green-Mediterranean diet on intrahepatic fat: the DIRECT PLUS randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2021;70:2085-2095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stockman MC, Thomas D, Burke J, Apovian CM. Intermittent Fasting: Is the Wait Worth the Weight? Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:172-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gallage S, Ali A, Barragan Avila JE, Seymen N, Ramadori P, Joerke V, Zizmare L, Aicher D, Gopalsamy IK, Fong W, Kosla J, Focaccia E, Li X, Yousuf S, Sijmonsma T, Rahbari M, Kommoss KS, Billeter A, Prokosch S, Rothermel U, Mueller F, Hetzer J, Heide D, Schinkel B, Machauer T, Pichler B, Malek NP, Longerich T, Roth S, Rose AJ, Schwenck J, Trautwein C, Karimi MM, Heikenwalder M. A 5:2 intermittent fasting regimen ameliorates NASH and fibrosis and blunts HCC development via hepatic PPARα and PCK1. Cell Metab. 2024;36:1371-1393.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Christ A, Lauterbach M, Latz E. Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection. Immunity. 2019;51:794-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 98.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yang M, Qi X, Li N, Kaifi JT, Chen S, Wheeler AA, Kimchi ET, Ericsson AC, Rector RS, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, Li G. Western diet contributes to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in male mice via remodeling gut microbiota and increasing production of 2-oleoylglycerol. Nat Commun. 2023;14:228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1110] [Cited by in RCA: 1062] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, Golan R, Fraser D, Bolotin A, Vardi H, Tangi-Rozental O, Zuk-Ramot R, Sarusi B, Brickner D, Schwartz Z, Sheiner E, Marko R, Katorza E, Thiery J, Fiedler GM, Blüher M, Stumvoll M, Stampfer MJ; Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT) Group. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1379] [Cited by in RCA: 1316] [Article Influence: 73.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 39. | Santos-Sánchez G, Cruz-Chamorro I, Álvarez-Ríos AI, Fernández-Santos JM, Vázquez-Román MV, Rodríguez-Ortiz B, Álvarez-Sánchez N, Álvarez-López AI, Millán-Linares MDC, Millán F, Pedroche J, Fernández-Pachón MS, Lardone PJ, Guerrero JM, Bejarano I, Carrillo-Vico A. Lupinus angustifolius Protein Hydrolysates Reduce Abdominal Adiposity and Ameliorate Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) in Western Diet Fed-ApoE(-/-) Mice. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10:1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Santos-Sánchez G, Cruz-Chamorro I. Plant-derived bioactive peptides and protein hydrolysates for managing MAFLD: A systematic review of in vivo effects. Food Chem. 2025;481:143956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Abbate JM, Macrì F, Capparucci F, Iaria C, Briguglio G, Cicero L, Salvo A, Arfuso F, Ieni A, Piccione G, Lanteri G. Administration of Protein Hydrolysates from Anchovy (Engraulis Encrasicolus) Waste for Twelve Weeks Decreases Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease Severity in ApoE(-/-)Mice. Animals (Basel). 2020;10:2303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | French WW, Dridi S, Shouse SA, Wu H, Hawley A, Lee SO, Gu X, Baum JI. A High-Protein Diet Reduces Weight Gain, Decreases Food Intake, Decreases Liver Fat Deposition, and Improves Markers of Muscle Metabolism in Obese Zucker Rats. Nutrients. 2017;9:587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lutsiv T, McGinley JN, Neil ES, Foster MT, Thompson HJ. Thwarting Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) with Common Bean: Dose- and Sex-Dependent Protection against Hepatic Steatosis. Nutrients. 2023;15:526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Díaz-Rúa R, Keijer J, Palou A, van Schothorst EM, Oliver P. Long-term intake of a high-protein diet increases liver triacylglycerol deposition pathways and hepatic signs of injury in rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;46:39-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Monteiro ME, Xavier AR, Oliveira FL, Filho PJ, Azeredo VB. Apoptosis induced by a low-carbohydrate and high-protein diet in rat livers. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5165-5172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Liao Y, Chen Q, Liu L, Huang H, Sun J, Bai X, Jin C, Li H, Sun F, Xiao X, Zhang Y, Li J, Han W, Fu S. Amino acid is a major carbon source for hepatic lipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2024;36:2437-2448.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Honda T, Ishigami M, Luo F, Lingyun M, Ishizu Y, Kuzuya T, Hayashi K, Nakano I, Ishikawa T, Feng GG, Katano Y, Kohama T, Kitaura Y, Shimomura Y, Goto H, Hirooka Y. Branched-chain amino acids alleviate hepatic steatosis and liver injury in choline-deficient high-fat diet induced NASH mice. Metabolism. 2017;69:177-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dai Y, Zhu J, Meng D, Yu C, Li Y. Association of homocysteine level with biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2016;58:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zhang Y, Wang Y, Liao X, Liu T, Yang F, Yang K, Zhou Z, Fu Y, Fu T, Sysa A, Chen X, Shen Y, Lyu J, Zhao Q. Glutamine prevents high-fat diet-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in mice by modulating lipolysis and oxidative stress. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2024;21:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Yecies JL, Zhang HH, Menon S, Liu S, Yecies D, Lipovsky AI, Gorgun C, Kwiatkowski DJ, Hotamisligil GS, Lee CH, Manning BD. Akt stimulates hepatic SREBP1c and lipogenesis through parallel mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways. Cell Metab. 2011;14:21-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | He J, Lin M, Zhang X, Zhang R, Tian T, Zhou Y, Dong W, Yang Y, Sun X, Dai Y, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Xu M, Lei QY, Xu Y, Lv L. TET2 is required to suppress mTORC1 signaling through urea cycle with therapeutic potential. Cell Discov. 2023;9:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Uehara K, Sostre-Colón J, Gavin M, Santoleri D, Leonard KA, Jacobs RL, Titchenell PM. Activation of Liver mTORC1 Protects Against NASH via Dual Regulation of VLDL-TAG Secretion and De Novo Lipogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13:1625-1647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Xu M, Zheng J, Ying T, Zhu Y, Du J, Li F, Chen B, Liu Y, He G. Dietary protein and risk of type 2 diabetes: findings from a registry-based cohort study and a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2025;15:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Benedé-Ubieto R, Cubero FJ, Nevzorova YA. Breaking the barriers: the role of gut homeostasis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2331460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Dong L, Lou W, Xu C, Wang J. Naringenin cationic lipid-modified nanoparticles mitigate MASLD progression by modulating lipid homeostasis and gut microbiota. J Nanobiotechnology. 2025;23:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Canfora EE, Meex RCR, Venema K, Blaak EE. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:261-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 1021] [Article Influence: 145.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 57. | Aron-Wisnewsky J, Vigliotti C, Witjes J, Le P, Holleboom AG, Verheij J, Nieuwdorp M, Clément K. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:279-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 129.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Liu JP, Zou WL, Chen SJ, Wei HY, Yin YN, Zou YY, Lu FG. Effects of different diets on intestinal microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease development. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7353-7364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 59. | Lee AH, Jha AR, Do S, Scarsella E, Shmalberg J, Schauwecker A, Steelman AJ, Honaker RW, Swanson KS. Dietary enrichment of resistant starches or fibers differentially alter the feline fecal microbiome and metabolite profile. Anim Microbiome. 2022;4:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Shi L, Tianqi F, Zhang C, Deng X, Zhou Y, Wang J, Wang L. High-protein compound yogurt with quinoa improved clinical features and metabolism of high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. J Dairy Sci. 2023;106:5309-5327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Li D, Li Y, Yang S, Lu J, Jin X, Wu M. Diet-gut microbiota-epigenetics in metabolic diseases: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Feng X, Lin Y, Zhuo S, Dong Z, Shao C, Ye J, Zhong B. Treatment of obesity and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease with a diet or orlistat: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023;117:691-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Liu Z, Jin P, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Wu X, Weng M, Cao S, Wang Y, Zeng C, Yang R, Liu C, Sun P, Tian C, Li N, Zeng Q. A comprehensive approach to lifestyle intervention based on a calorie-restricted diet ameliorates liver fat in overweight/obese patients with NAFLD: a multicenter randomized controlled trial in China. Nutr J. 2024;23:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Chaturvedi S, Tripathi D, Bhatia N, Vikram NK, Pandey RM. Protein-rich diet shields against MASLD, while saturated fatty acids (SFA) intake elevates MASLD risk: Findings of a case-control investigation. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2024;63:1203. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 65. | Daftari G, Tehrani AN, Pashayee-Khamene F, Karimi S, Ahmadzadeh S, Hekmatdoost A, Salehpour A, Saber-Firoozi M, Hatami B, Yari Z. Dietary protein intake and mortality among survivors of liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Lee JH, Lee HS, Ahn SB, Kwon YJ. Dairy protein intake is inversely related to development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:5252-5260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Xu C, Markova M, Seebeck N, Loft A, Hornemann S, Gantert T, Kabisch S, Herz K, Loske J, Ost M, Coleman V, Klauschen F, Rosenthal A, Lange V, Machann J, Klaus S, Grune T, Herzig S, Pivovarova-Ramich O, Pfeiffer AFH. High-protein diet more effectively reduces hepatic fat than low-protein diet despite lower autophagy and FGF21 levels. Liver Int. 2020;40:2982-2997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Gillingham MB, Elizondo G, Behrend A, Matern D, Schoeller DA, Harding CO, Purnell JQ. Higher dietary protein intake preserves lean body mass, lowers liver lipid deposition, and maintains metabolic control in participants with long-chain fatty acid oxidation disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42:857-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Skytte MJ, Samkani A, Petersen AD, Thomsen MN, Astrup A, Chabanova E, Frystyk J, Holst JJ, Thomsen HS, Madsbad S, Larsen TM, Haugaard SB, Krarup T. A carbohydrate-reduced high-protein diet improves HbA(1c) and liver fat content in weight stable participants with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2019;62:2066-2078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Khazaei Y, Dehghanseresht N, Ebrahimi Mousavi S, Nazari M, Salamat S, Asbaghi O, Mansoori A. Association Between Protein Intake From Different Animal and Plant Origins and the Risk of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Case-Control Study. Clin Nutr Res. 2023;12:29-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Markova M, Pivovarova O, Hornemann S, Sucher S, Frahnow T, Wegner K, Machann J, Petzke KJ, Hierholzer J, Lichtinghagen R, Herder C, Carstensen-Kirberg M, Roden M, Rudovich N, Klaus S, Thomann R, Schneeweiss R, Rohn S, Pfeiffer AF. Isocaloric Diets High in Animal or Plant Protein Reduce Liver Fat and Inflammation in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:571-585.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Lang S, Martin A, Farowski F, Wisplinghoff H, Vehreschild MJGT, Liu J, Krawczyk M, Nowag A, Kretzschmar A, Herweg J, Schnabl B, Tu XM, Lammert F, Goeser T, Tacke F, Heinzer K, Kasper P, Steffen HM, Demir M. High Protein Intake Is Associated With Histological Disease Activity in Patients With NAFLD. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:681-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Wehmeyer MH, Zyriax BC, Jagemann B, Roth E, Windler E, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Lohse AW, Kluwe J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with excessive calorie intake rather than a distinctive dietary pattern. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Recaredo G, Marin-Alejandre BA, Cantero I, Monreal JI, Herrero JI, Benito-Boillos A, Elorz M, Tur JA, Martínez JA, Zulet MA, Abete I. Association between Different Animal Protein Sources and Liver Status in Obese Subjects with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Fatty Liver in Obesity (FLiO) Study. Nutrients. 2019;11:2359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Zeng XF, Varady KA, Wang XD, Targher G, Byrne CD, Tayyem R, Latella G, Bergheim I, Valenzuela R, George J, Newberry C, Zheng JS, George ES, Spearman CW, Kontogianni MD, Ristic-Medic D, Peres WAF, Depboylu GY, Yang W, Chen X, Rosqvist F, Mantzoros CS, Valenti L, Yki-Järvinen H, Mosca A, Sookoian S, Misra A, Yilmaz Y, Kim W, Fouad Y, Sebastiani G, Wong VW, Åberg F, Wong YJ, Zhang P, Bermúdez-Silva FJ, Ni Y, Lupsor-Platon M, Chan WK, Méndez-Sánchez N, de Knegt RJ, Alam S, Treeprasertsuk S, Wang L, Du M, Zhang T, Yu ML, Zhang H, Qi X, Liu X, Pinyopornpanish K, Fan YC, Niu K, Jimenez-Chillaron JC, Zheng MH. The role of dietary modification in the prevention and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international multidisciplinary expert consensus. Metabolism. 2024;161:156028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Rietman A, Sluik D, Feskens EJM, Kok FJ, Mensink M. Associations between dietary factors and markers of NAFLD in a general Dutch adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Nikparast A, Sohouli MH, Forouzan K, Farani MA, Dehghan P, Rohani P, Asghari G. The association between total, animal, and plant protein intake and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in overweight and obese children and adolescents. Nutr J. 2025;24:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Galarregui C, Cantero I, Marin-Alejandre BA, Monreal JI, Elorz M, Benito-Boillos A, Herrero JI, de la O V, Ruiz-Canela M, Hermsdorff HHM, Bressan J, Tur JA, Martínez JA, Zulet MA, Abete I. Dietary intake of specific amino acids and liver status in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: fatty liver in obesity (FLiO) study. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:1769-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Aimutis WR. Plant-Based Proteins: The Good, Bad, and Ugly. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2022;13:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Pinckaers PJM, Trommelen J, Snijders T, van Loon LJC. The Anabolic Response to Plant-Based Protein Ingestion. Sports Med. 2021;51:59-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Rashwan AK, Osman AI, Abdelshafy AM, Mo J, Chen W. Plant-based proteins: advanced extraction technologies, interactions, physicochemical and functional properties, food and related applications, and health benefits. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2025;65:667-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, Prochaska J, Leischow S, Nides M, Blumenstein B, Clarke A, Cain D, Jacobs C. Cytisinicline for Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330:152-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Zhang R, Zhang H, Wang Y, Tang LJ, Li G, Huang OY, Chen SD, Targher G, Byrne CD, Gu BB, Zheng MH. Higher consumption of animal organ meat is associated with a lower prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2023;12:645-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Huang DQ, Wong VWS, Rinella ME, Boursier J, Lazarus JV, Yki-Järvinen H, Loomba R. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in adults. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;11:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 101.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Yang A, Zhu X, Zhang L, Ding Y. Transitioning from NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD: Consistent prevalence and risk factors in a Chinese cohort. J Hepatol. 2024;80:e154-e155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Simon TG, Wilechansky RM, Stoyanova S, Grossman A, Dichtel LE, Lauer GM, Miller KK, Hoshida Y, Corey KE, Loomba R, Chung RT, Chan AT. Aspirin for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Without Cirrhosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024;331:920-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Bo T, Gao L, Yao Z, Shao S, Wang X, Proud CG, Zhao J. Hepatic selective insulin resistance at the intersection of insulin signaling and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cell Metab. 2024;36:947-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Price JK, Owrangi S, Gundu-Rao N, Satchi R, Paik JM. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1999-2010.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 94.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4273] [Cited by in RCA: 4610] [Article Influence: 219.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Pustjens J, van Kleef LA, Janssen HLA, de Knegt RJ, Brouwer WP. Differential prevalence and prognostic value of metabolic syndrome components among patients with MASLD. JHEP Rep. 2024;6:101193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Harrison SA, Rolph T, Knott M, Dubourg J. FGF21 agonists: An emerging therapeutic for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and beyond. J Hepatol. 2024;81:562-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Stefan N, Yki-Järvinen H, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: heterogeneous pathomechanisms and effectiveness of metabolism-based treatment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13:134-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 140.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Crişan D, Avram L, Morariu-Barb A, Grapa C, Hirişcau I, Crăciun R, Donca V, Nemeş A. Sarcopenia in MASLD-Eat to Beat Steatosis, Move to Prove Strength. Nutrients. 2025;17:178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Mai Z, Chen Y, Mao H, Wang L. Association between the skeletal muscle mass to visceral fat area ratio and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: A cross-sectional study of NHANES 2017-2018. J Diabetes. 2024;16:e13569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Handelsman Y, Anderson JE, Bakris GL, Ballantyne CM, Bhatt DL, Bloomgarden ZT, Bozkurt B, Budoff MJ, Butler J, Cherney DZI, DeFronzo RA, Del Prato S, Eckel RH, Filippatos G, Fonarow GC, Fonseca VA, Garvey WT, Giorgino F, Grant PJ, Green JB, Greene SJ, Groop PH, Grunberger G, Jastreboff AM, Jellinger PS, Khunti K, Klein S, Kosiborod MN, Kushner P, Leiter LA, Lepor NE, Mantzoros CS, Mathieu C, Mende CW, Michos ED, Morales J, Plutzky J, Pratley RE, Ray KK, Rossing P, Sattar N, Schwarz PEH, Standl E, Steg PG, Tokgözoğlu L, Tuomilehto J, Umpierrez GE, Valensi P, Weir MR, Wilding J, Wright EE Jr. DCRM 2.0: Multispecialty practice recommendations for the management of diabetes, cardiorenal, and metabolic diseases. Metabolism. 2024;159:155931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Aboona MB, Faulkner C, Rangan P, Ng CH, Huang DQ, Muthiah M, Nevah Rubin MI, Han MAT, Fallon MB, Kim D, Chen VL, Wijarnpreecha K. Disparities among ethnic groups in mortality and outcomes among adults with MASLD: A multicenter study. Liver Int. 2024;44:1316-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Donovan SM, Abrahams M, Anthony JC, Bao Y, Barragan M, Bermingham KM, Blander G, Keck AS, Lee BY, Nieman KM, Ordovas JM, Penev V, Reinders MJ, Sollid K, Thosar S, Winters BL. Personalized nutrition: perspectives on challenges, opportunities, and guiding principles for data use and fusion. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2025;65:7151-7169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Kolodziejczyk AA, Zheng D, Elinav E. Diet-microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:742-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 85.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Kan J, Ni J, Xue K, Wang F, Zheng J, Cheng J, Wu P, Runyon MK, Guo H, Du J. Personalized Nutrition Intervention Improves Health Status in Overweight/Obese Chinese Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Nutr. 2022;9:919882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Vrentzos E, Pavlidis G, Korakas E, Kountouri A, Pliouta L, Dimitriadis GD, Lambadiari V. Nutraceutical Strategies for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Path to Liver Health. Nutrients. 2025;17:1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Singar S, Nagpal R, Arjmandi BH, Akhavan NS. Personalized Nutrition: Tailoring Dietary Recommendations through Genetic Insights. Nutrients. 2024;16:2673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Galekop MMJ, Uyl-de Groot CA, Ken Redekop W. A Systematic Review of Cost-Effectiveness Studies of Interventions With a Personalized Nutrition Component in Adults. Value Health. 2021;24:325-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Pigsborg K, Kalea AZ, De Dominicis S, Magkos F. Behavioral and Psychological Factors Affecting Weight Loss Success. Curr Obes Rep. 2023;12:223-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Delgado-Lista J, Alcala-Diaz JF, Torres-Peña JD, Quintana-Navarro GM, Fuentes F, Garcia-Rios A, Ortiz-Morales AM, Gonzalez-Requero AI, Perez-Caballero AI, Yubero-Serrano EM, Rangel-Zuñiga OA, Camargo A, Rodriguez-Cantalejo F, Lopez-Segura F, Badimon L, Ordovas JM, Perez-Jimenez F, Perez-Martinez P, Lopez-Miranda J; CORDIOPREV Investigators. Long-term secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet and a low-fat diet (CORDIOPREV): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1876-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 94.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Jiang F, Wang L, Ying H, Sun J, Zhao J, Lu Y, Bian Z, Chen J, Fang A, Zhang X, Larsson SC, Mantzoros CS, Wang W, Yuan S, Ding Y, Li X. Multisystem health comorbidity networks of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Med. 2024;5:1413-1423.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/