Published online Feb 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.116007

Revised: December 1, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: February 7, 2026

Processing time: 89 Days and 18.3 Hours

The clinical outcomes of endoscopic rubber band ligation (ERBL), injection sclerotherapy (IS), and endoscopic polidocanol sclerobanding (ESB) have not yet been well studied.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ERBL, IS, and ESB for treating grade I-III in

This retrospective cohort study was performed on 201 patients, who were gr

The patient distribution across the ERBL, IS, and ESB groups was 70, 66, and 65, respectively. Both the ERBL and ESB groups demonstrated lower overall recu

The three treatments evaluated (ERBL, IS, and ESB) provide durable clinical outcomes for grade I hemorrhoids, with no significant differences in postoperative adverse events. For grade II-III hemorrhoids, ESB possesses the dual advantages of lower recurrence rates and reduced postoperative pain compared with IS and ERBL.

Core Tip: The clinical outcomes of endoscopic rubber band ligation (ERBL), injection sclerotherapy (IS), and endoscopic polidocanol sclerobanding (ESB) for treating grade I-III internal hemorrhoids have been limited in previous research. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of these three methods, revealing that all provided long-term clinical benefits for grade I hemorrhoids. For grade II-III hemorrhoids, ESB demonstrated superior outcomes, including lower recurrence rates and minimal postoperative pain compared with IS and ERBL.

- Citation: Zu N, Jing X, Zhou XY, Ma BB, Wang SJ, Qi XS, Liu LB. Endoscopic rubber band ligation, injection sclerotherapy, and sclerobanding for the treatment of internal hemorrhoids. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(5): 116007

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i5/116007.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.116007

Internal hemorrhoids, one of the most common anorectal conditions, result from the pathological displacement of anal cushions above the dentate line, clinically manifesting as painless rectal bleeding and/or prolapse[1,2]. Epidemiological studies have reported a high prevalence of hemorrhoids in the adult population. In the United States, approximately 10 million people reportedly experience hemorrhoid-related symptoms, with healthcare costs for hemorrhoids exceeding 800 million dollars annually[3,4]. Thus, hemorrhoidal diseases represent a remarkable public health burden.

For grade I-III internal hemorrhoids that do not respond to conservative treatments (e.g., dietary modifications, medications, and sitz baths), minimally invasive endoscopic therapies have become the first-line intervention. Endoscopic rubber band ligation (ERBL) and injection sclerotherapy (IS) are utilized as the primary treatments for grade I-III internal hemorrhoids, owing to their simplicity and favorable safety profiles[1]. Recently, a hybrid technique known as endoscopic polidocanol foam sclerobanding (EFSB), integrating ERBL with sclerotherapy, has been proposed by Qu et al[5], who reported satisfactory clinical outcomes using EFSB, identifying it as another viable therapeutic option. Compared with polidocanol foam, polidocanol liquid is also widely used for internal hemorrhoids because of its higher practical clinical efficacy[6,7]. However, the clinical outcomes of these three techniques [ERBL, IS, and endoscopic polidocanol sclerobanding (ESB)] have not yet been sufficiently evaluated systematically. To address this knowledge gap, in the present study, a retrospective cohort analysis was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic treatments, specifically ERBL, IS, and ESB, in patients with grade I-III internal hemorrhoids.

This single-center retrospective cohort study was performed at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (Qingdao, Shandong Province, China). Patients diagnosed with grade I-III internal hemorrhoids based on the Goligher classification, who had not responded to conservative treatment and agreed to undergo endoscopic intervention, were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Severe cardiopulmonary insufficiency or coagulopathy; (2) A history of malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, or other perianal conditions; (3) Autoimmune disorders; (4) Pregnancy; (5) Prior hemorrhoidectomy or endoscopic treatments within the preceding three years; (6) Allergy to polidocanol; and (7) Loss to follow-up or incomplete clinical data. All patients were treated by the same endoscopic physician.

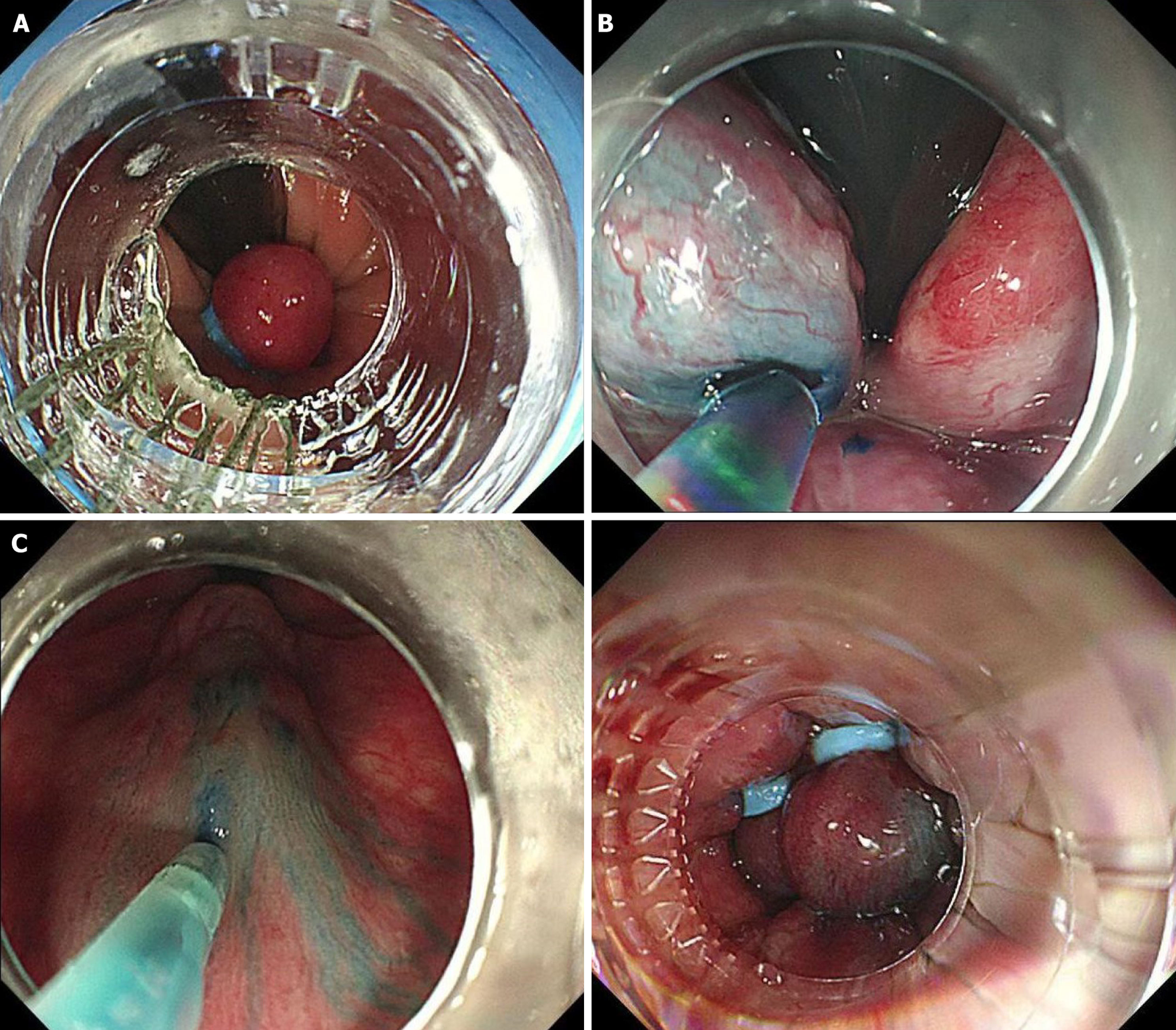

Before inserting the endoscope, prolapsed internal hemorrhoids were manually repositioned. Subsequently, endoscopic intestinal examination and polypectomy were performed prior to hemorrhoidal treatment. The operative field was sufficiently exposed to identify the dentate line, anorectal line, and hemorrhoidal base, enabling an assessment of the extent and size of the internal hemorrhoids. Using an anteflexed or retroflexed view, the next steps were implemented as follows.

ERBL: A gastroscope (Olympus GIF-Q260J, Japan) with a ligation device (Cook MBL-6-F, United States) was used. The ligation device was placed at the rectal mucosa or hemorrhoidal base. Continuous suction was maintained until the target tissue was drawn into the ligation chamber, indicated by a “full red” sign, and the rubber band was thereafter released.

IS: A 23G, 5-mm endoscopic injection needle (Boston Scientific, United States) prefilled with polidocanol liquid was used to select 1-6 injection sites above the dentate line. The needle was inserted at an angle into the submucosa of the hem

ESB: The sclerosant was injected continuously during slow endoscope withdrawal until white foam accumulation or mild mucosal elevation was observed. After sclerotherapy, the ligation device was reattached to the endoscope and reinserted. Once clear whitening of the sclerosed area was confirmed, band ligation was applied to the base of the hemorrhoid (Figure 1).

Postoperative follow-up was carried out via structured telephone interviews, outpatient visits, or endoscopic re-evaluations. Clinical efficacy, recurrence, and postoperative adverse events were assessed by separate researchers, each blinded to the treatment method throughout the trial. Since there are no standardized criteria for assessing hemorrhoid symptoms, patient-reported symptom relief and the need for retreatment were utilized as the primary measures of treatment success and recurrence. The following post-surgery adverse events were systematically evaluated at the 1-month follow-up: (1) Presence or absence of pain; (2) Pain severity on the visual analog scale (VAS), with 0 indicating no pain; (3) Pain duration in days, recorded as 0 for asymptomatic patients; (4) Bleeding episodes; (5) Fever; and (6) Dysuria. At 3 months postoperatively, clinical efficacy was categorized as “cured” (complete symptom resolution), “improved” (notable symptom relief), or “ineffective” (no change from the preoperative status). Recurrence was defined as the reap

The primary outcome was the overall recurrence during the follow-up period. The secondary outcomes included treatment efficacy, short-term recurrence at 6 months after surgery, and adverse reactions.

Based on previous research studies[2,8], recurrence rates for ERBL, IS, and ESB were estimated to be 20%, 35%, and 10%, respectively. With a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05 and 80% power, 52 participants were required per group. To account for a 15% dropout rate, at least 60 patients per group were recruited to ensure an adequate sample size. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Normally distributed data were presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using analysis of variance. Non-normally distributed data were reported as median with interquartile ranges [median (Q1, Q3)]. The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed for non-normal continuous variables and ordinal categorical data. The χ2 test was applied to count data with count outcomes. Post-hoc analyses were conducted when P < 0.05, with Bonferroni’s correction applied for multiple comparisons (P’). Statistical significance was set at P or P’ < 0.05 (two-sided).

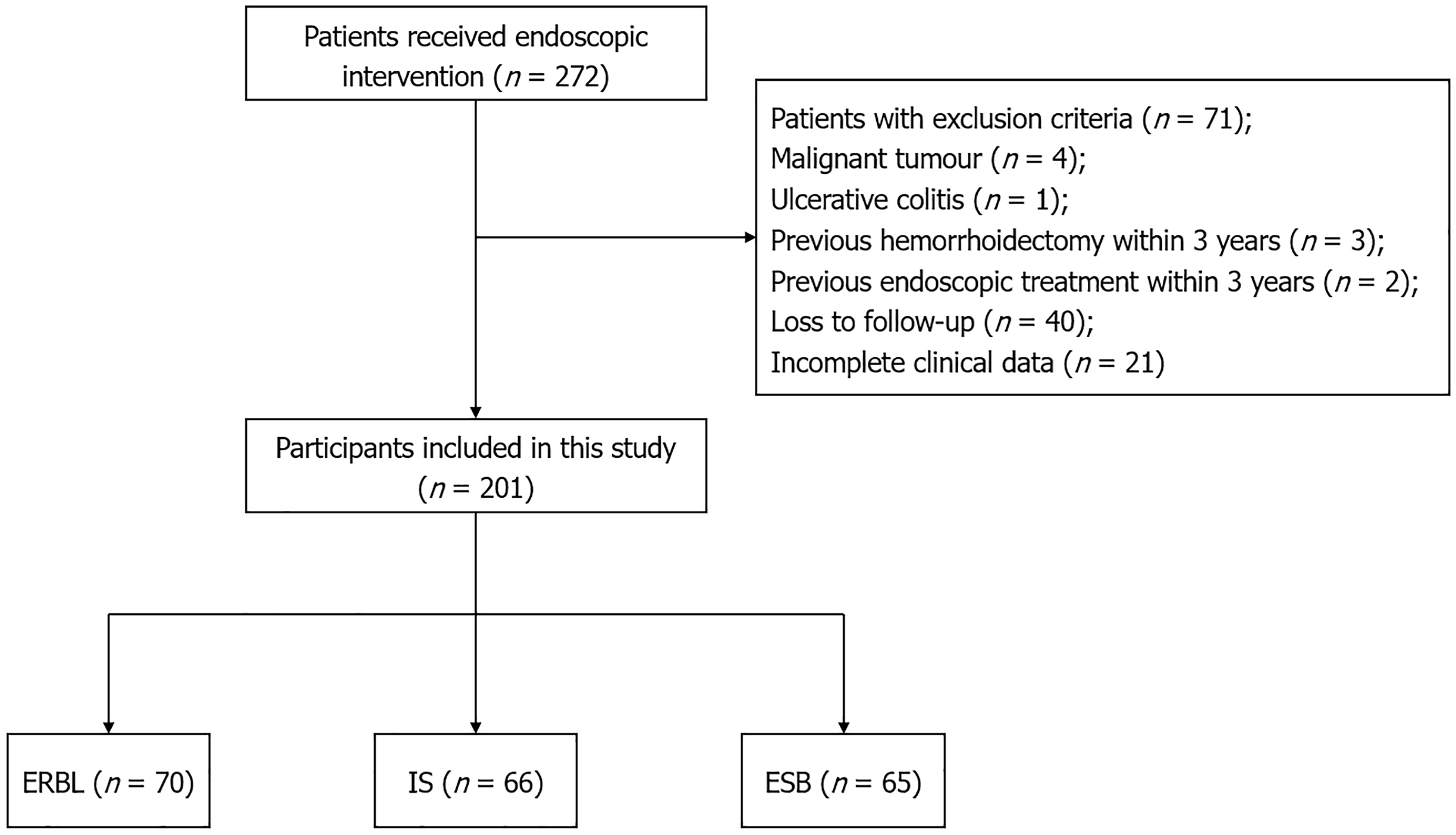

From July 1, 2019, to December 31, 2024, 272 patients received treatment for internal hemorrhoids at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. After applying the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, 201 patients were finally enrolled in the study and categorized into the following groups: ERBL (n = 70), IS (n = 66), and ESB (n = 65) (Figure 2). The study population included a high proportion of men (126, 62.69%), with an average age of 49.94 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24.19 kg/m2. The median duration of the disease was 36 months. Among 201 patients, 61 (30.35%) had grade I, 65 (32.34%) had grade II, and 75 (37.31%) had grade III hemorrhoids. Baseline characteristics, such as sex, age, disease duration, BMI, and hemorrhoid severity, were well-balanced across all the groups (Table 1).

| Subgroup | Gender (female/male) | Age (years) | Disease duration [months, median (Q1, Q3)] | BMI (kg/m2) | Hemorrhoid grade | ||

| Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | |||||

| ERBL | 26/44 | 49.00 ± 11.59 | 30.00 (6.00, 61.50) | 24.46 ± 3.24 | 22 (31.43) | 22 (31.43) | 26 (37.14) |

| IS | 19/47 | 49.94 ± 12.74 | 36.00 (11.25, 120.00) | 23.59 ± 2.54 | 25 (37.88) | 22 (33.33) | 19 (28.79) |

| ESB | 30/35 | 50.59 ± 12.60 | 48.00 (12.00, 120.00) | 24.49 ± 3.02 | 14 (21.54) | 21 (32.31) | 30 (46.15) |

| Total | 75/126 | 49.94 ± 12.27 | 36.00 (12.00, 120.00) | 24.19 ± 2.97 | 61 (30.35) | 65 (32.34) | 75 (37.31) |

| Statistic | χ2 = 4.224 | F = 0.425 | H = 4.140 | F = 1.996 | H = 5.527 | ||

| P value | 0.121 | 0.655 | 0.126 | 0.139 | 0.063 | ||

The median number of rubber bands used in the ERBL and ESB groups was 4. For the IS group, the median sclerosant dose was 9.5 mL, while it was 8 mL for the ESB group. A total of 129 (64.18%) cases received endoscopic treatment under local anesthesia. The median follow-up time was 20 months. No significant differences were found among the three groups regarding the number of bands, sclerosant amount, anesthesia method, or follow-up time (Table 2). As the base

| Subgroup | Rubber bands [number, median (Q1, Q3)] | Sclerosant dosage [mL, median (Q1, Q3)] | Anesthesia method (local/intravenous anesthesia) | Follow-up duration [months, median (Q1, Q3)] |

| ERBL | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 42/28 | 20.50 (9.00, 24.00) | |

| IS | 9.5 (6.75, 10.00) | 42/24 | 23.50 (13.00, 24.00) | |

| ESB | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 8.00 (6.00, 10.00) | 45/20 | 18.00 (11.25, 24.00) |

| Total | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 8.00 (6.00, 10.00) | 129/72 | 20.00 (12.00, 24.00) |

| Statistic | Z = -0.901 | Z = -1.496 | χ2 = 1.262 | H = 0.909 |

| P value | 0.367 | 0.135 | 0.532 | 0.635 |

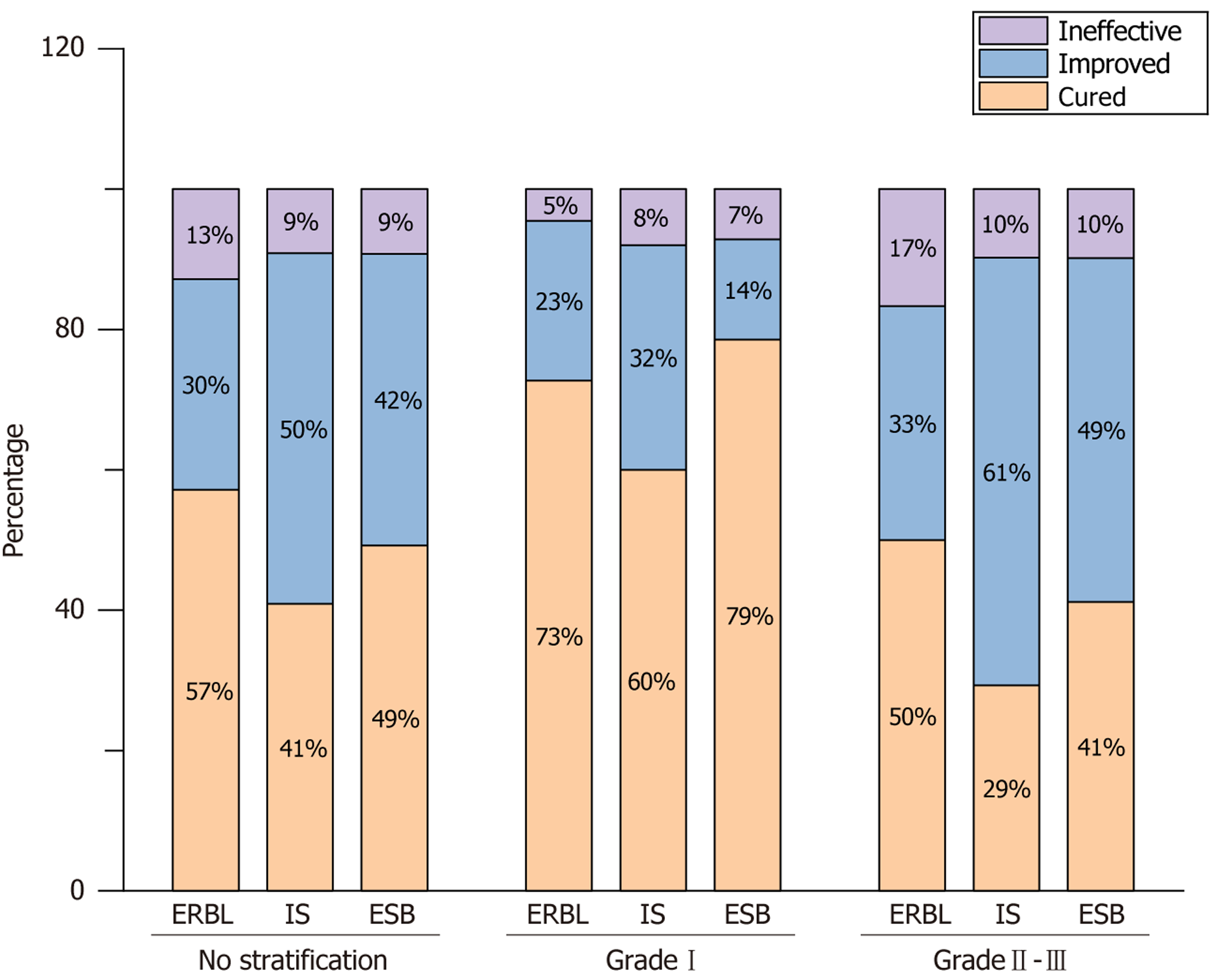

At the 3-month follow-up, the effective rates for the ERBL, IS, and ESB groups were 87.14%, 90.91%, and 90.77%, res

| Subgroup | Efficacy (no stratification) | Efficacy (grade I) | Efficacy (grade II-III) | ||||||

| Cured | Improved | Ineffective | Cured | Improved | Ineffective | Cured | Improved | Ineffective | |

| ERBL | 40 (57.14) | 21 (30.00) | 9 (12.86) | 16 (72.73) | 5 (22.73) | 1 (4.54) | 24 (50.00) | 16 (33.33) | 8 (16.67) |

| IS | 27 (40.91) | 33 (50.00) | 6 (9.09) | 15 (60.00) | 8 (32.00) | 2 (8.00) | 12 (29.27) | 25 (60.97) | 4 (9.76) |

| ESB | 32 (49.23) | 27 (41.54) | 6 (9.23) | 11 (78.57) | 2 (14.29) | 1 (7.14) | 21 (41.18) | 25 (49.02) | 5 (9.80) |

| Total | 99 (49.25) | 81 (40.30) | 21 (10.45) | 42 (68.85) | 15 (24.59) | 4 (6.56) | 57 (40.72) | 66 (47.14) | 17 (12.14) |

| Statistic | H = 1.999 | H = 1.527 | H = 1.682 | ||||||

| P value | 0.368 | 0.466 | 0.431 | ||||||

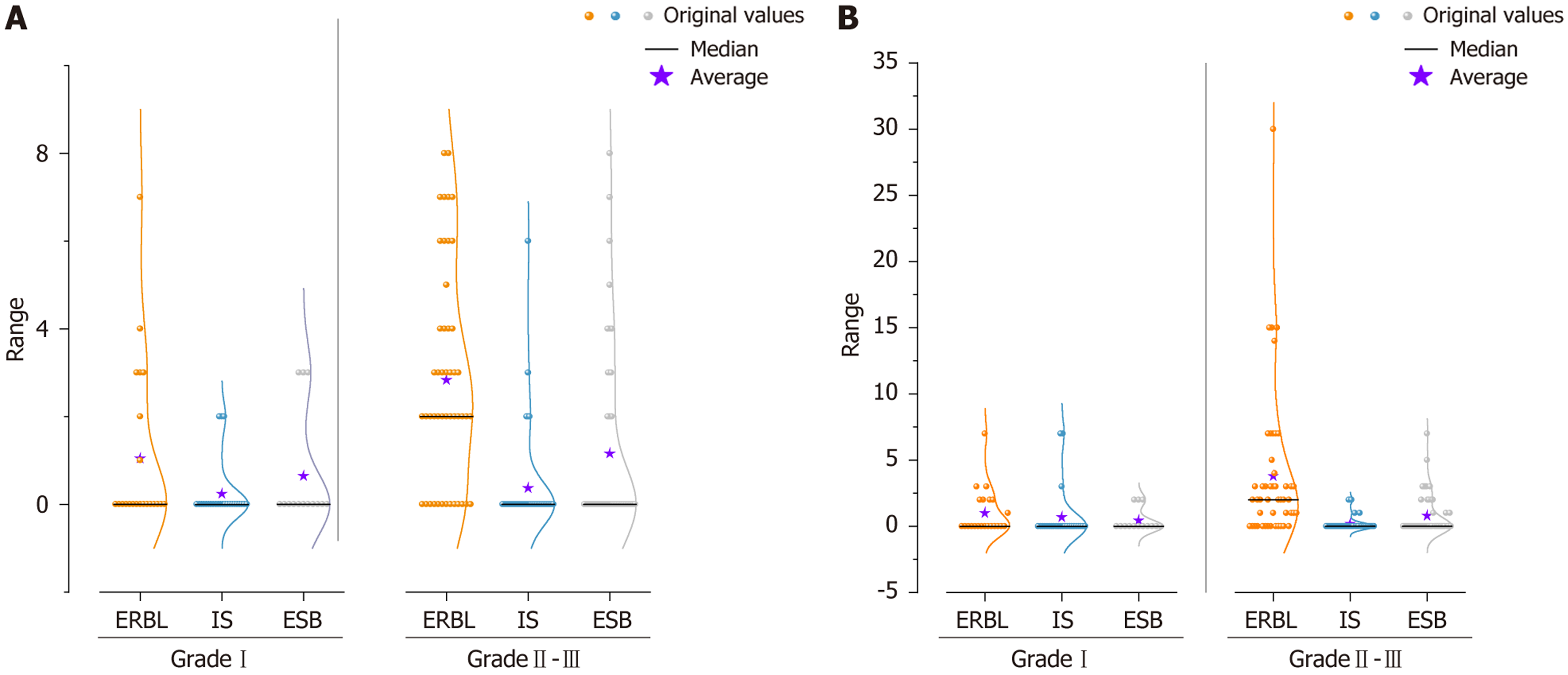

Pain was found as the most common postoperative adverse reaction. The ERBL group exhibited a significantly higher incidence of pain (58.57%), a higher median VAS score of 2, and a longer median pain duration of 2 days compared with those observed for the IS and ESB groups (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Additionally, no significant differences were identified among the three groups regarding bleeding, fever, or dysuria (Table 5). While pain outcomes were similar across all techniques for grade I hemorrhoids (Table 6), the ERBL group had a higher prevalence rate of pain (72.92%), a greater number of high VAS scores, and longer pain durations (median pain duration, 2 days) for grade II-III hemorrhoids than those of the other two groups (Table 7 and Figure 4).

| Subgroup | Pain | VAS [median (Q1, Q3)] | Pain duration [days, median (Q1, Q3)] |

| ERBL | 41 (58.57)a | 2.00 (0.00, 3.25)a | 2.00 (0.00, 3.00)a |

| IS | 8 (12.12)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)a,b |

| ESB | 18 (27.69)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00)a,b |

| Total | 67 (33.33) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00) |

| Statistic | χ2 = 34.359 | H = 36.950 | H = 38.365 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Subgroup | Bleeding | Fever | Dysuria |

| ERBL | 1 (1.43) | 2 (2.86) | 3 (4.29) |

| IS | 0 (0.00) | 2 (3.03) | 0 (0.00) |

| ESB | 1 (1.54) | 1 (1.54) | 3 (4.62) |

| Total | 2 (1.00) | 5 (2.49) | 6 (2.99) |

| Statistic | |||

| P value | 0.770 | 1.000 | 0.221 |

| Subgroup | Pain | VAS [median (Q1, Q3)] | Pain duration [days, median (Q1, Q3)] |

| ERBL | 6 (27.27) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.25) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00) |

| IS | 3 (12.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| ESB | 3 (21.43) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.75) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.50) |

| Total | 12 (19.67) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Statistic | H = 3.308 | H = 2.182 | |

| P value | 0.426 | 0.191 | 0.336 |

| Subgroup | Pain | VAS [median (Q1, Q3)] | Pain duration [days, median (Q1, Q3)] |

| ERBL | 35 (72.92)a | 2.00 (0.00, 4.00)a | 2.00 (0.00, 3.75)a |

| IS | 5 (12.20)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00)a,b |

| ESB | 15 (29.41)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00)a,b | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00)a,b |

| Total | 55 (39.29) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.75) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00) |

| Statistic | χ² = 37.461 | H = 35.553 | H = 41.352 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

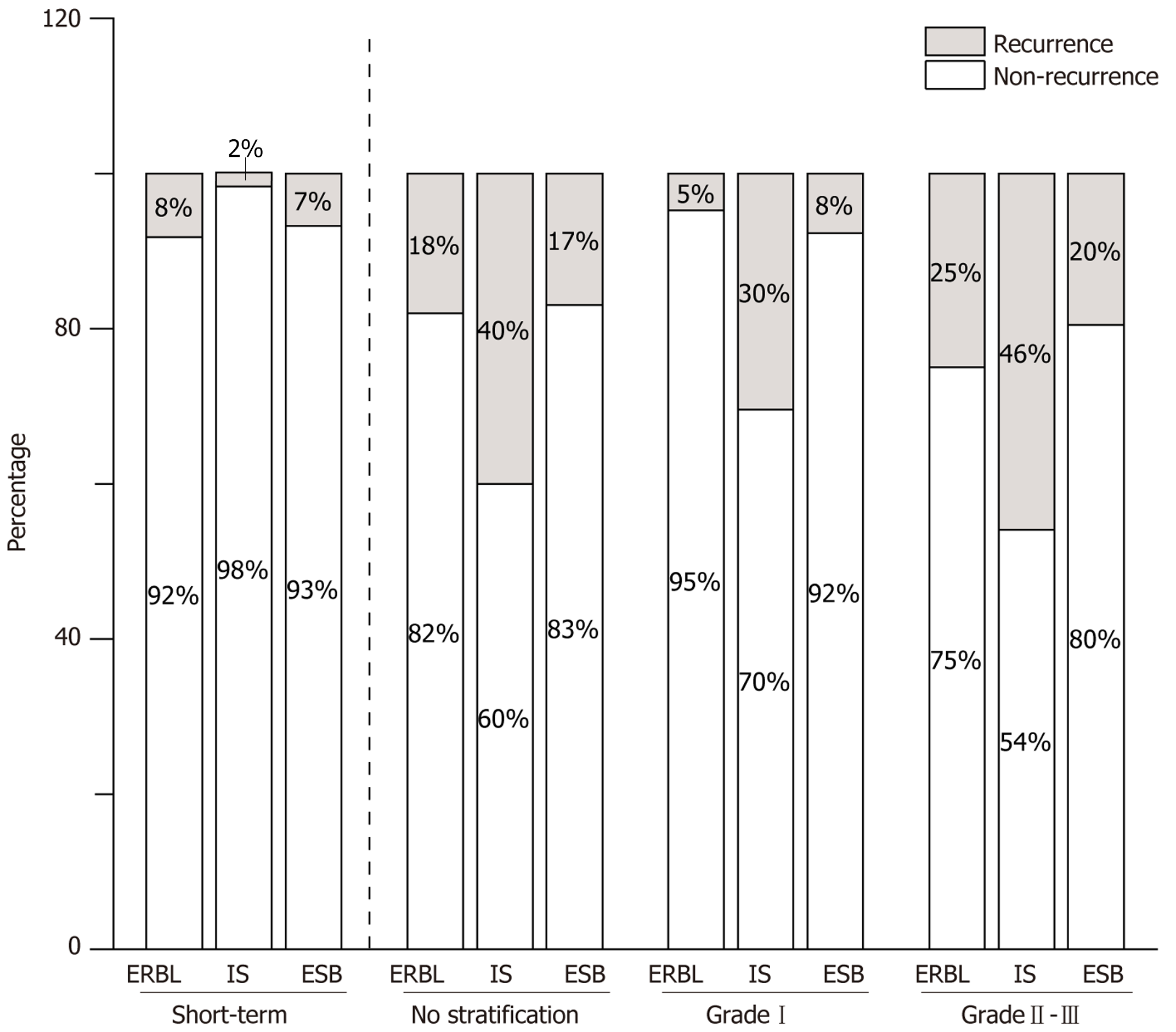

Among 180 patients who received adequate treatment, 10 experienced disease recurrence within 6 months post-operation. No statistically significant difference was observed among the three groups. The total recurrence rate during the follow-up period was 25%, with the ERBL, IS, and ESB groups showing the recurrence rates of 18.03%, 40%, and 16.95%, respectively. Both the ERBL and ESB groups demonstrated significantly lower total recurrence rates compared with the IS group (P’ = 0.024 and 0.015, respectively). For grade I internal hemorrhoids, the total recurrence rates were not significantly different among the three groups. The total recurrence rates of grade II-III internal hemorrhoids in the three groups were 25% (ERBL), 45.95% (IS), and 19.57% (ESB), respectively (Figure 5). The IS group had a higher recurrence rate than that of the ESB group (P’ = 0.03) (Table 8).

| Subgroup | Short-term recurrence (no stratification) | Total recurrence (no stratification) | Total recurrence (grade I) | Total recurrence (grade II-III) | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| ERBL | 5 (8.20) | 56 (91.80) | 11 (18.03)b,c | 50 (81.97)b,c | 1 (4.76) | 20 (95.24) | 10 (25.00)a | 30 (75.00)a |

| IS | 1 (1.67) | 59 (98.33) | 24 (40.00)b | 36 (60.00)b | 7 (30.43) | 16 (69.57) | 17 (45.95)a | 20 (54.05)a |

| ESB | 4 (6.78) | 55 (93.22) | 10 (16.95)b,c | 49 (83.05)b,c | 1 (7.69) | 12 (92.31) | 9 (19.57)a,c | 37 (80.43)a,c |

| Total | 10 (5.56) | 170 (94.44) | 45 (25.00) | 135 (75.00) | 9 (15.79) | 48 (84.21) | 36 (29.27) | 87 (70.73) |

| Statistic | χ2 = 10.819 | χ2 = 7.415 | ||||||

| P value | 0.284 | 0.004 | 0.050 | 0.025 | ||||

A deeper comprehension of the role of anal cushions has led to a shift in hemorrhoid treatment from traditional radical surgery to an emphasis on symptom relief while preserving the integrity of the anal cushions[9,10]. The advancement of endoscopic therapies has provided novel clinical options. Both ERBL and IS procedures use rubber bands or sclerosants to induce fibrosis in the hemorrhoidal tissues and occlude vessels, thereby controlling bleeding and reducing prolapse, contributing to symptom improvement. Recently, studies have introduced EFSB as an innovative method, combining 1% or 3% polidocanol foam sclerotherapy with rubber band ligation, applied in two ways: “Ligation followed by sclerotherapy” or “sclerotherapy followed by ligation”[5,11,12]. In the present study, sclerotherapy was initially performed using 1% polidocanol liquid, followed by ligation. The use of a liquid sclerosant eliminated the need for foam pre

This retrospective comparative study assessed the effectiveness and safety of ERBL, IS, and ESB in treating internal hemorrhoids. All three treatments showed significant short-term success at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Although IS provides adequate short-term control of hemorrhoidal bleeding, it exhibits poorer long-term efficacy and higher recurrence rates for grade II-III hemorrhoids[8,13]. Similar findings were reported by Abiodun et al[14], that is, the IS requires a greater number of retreatments. The present study also indicated that IS was associated with a higher recu

This study reported postoperative pain as the most common adverse reaction post-surgery. The ERBL group exhibited a higher occurrence rate, increased severity, and a longer duration of pain compared with the other groups, while the ESB group did not experience too many adverse reactions. In addition to common pain sources such as anal sphincter spasm and individual differences in pain threshold, key factors contributing to the higher pain levels in the ERBL group included the placement of rubber bands too close to the dentate line and mucosal ischemia between the bands[17,18]. Notably, the local nerve-blocking effect of polidocanol has been shown to reduce postoperative pain associated with IS and ESB treatments[2]. Postoperative pain typically resolves within 7 days in 97% of cases. Other common adverse reactions include: (1) Localized bleeding resulting from trauma to the anal mucosa; (2) Low-grade fever due to inflammatory mediators released in response to the sclerosant or rubber bands; and (3) Temporary dysuria caused by neuro

Various evaluation criteria, including different symptom scores and follow-up durations, have been used to determine the optimal treatments for different hemorrhoid stages. However, research findings and conclusions remain inconsistent. It is widely accepted that ERBL, causing ischemic necrosis of the hemorrhoidal tissue through mechanical ligation at the hemorrhoid base, is more appropriate for prolapsed grade II-III internal hemorrhoids[20,21]. The IS, which induces localized sterile inflammation and fibrosis to secure prolapsed cushions and occlude vessels, demonstrates more fav

Compared with traditional single therapies, ESB achieves a synergistic effect of “chemical stimulation by sclerosant” and “mechanical ligation by rubber bands”. This dual approach obstructs blood flow and elevates hemorrhoidal tissue, leading to more effective therapeutic outcomes. In addition to its primary role in symptom improvement, the local ane

This study has some limitations. Firstly, its retrospective design could introduce potential biases, including selection bias due to the single-center cohort and non-randomized treatment assignments, as well as information bias arising from less precise variables during follow-up and missing data resulting from the extended follow-up period. Secondly, although key confounding factors were accounted for, recurrence and postoperative pain could still be influenced by unmeasured variables, such as individual healing capacity, dietary factors, or adherence to postoperative instructions. Notably, the recurrence rates were higher than initially anticipated. The sample size was calculated based on recurrence rates reported in previous studies, which may not fully reflect the experience at our single-center institution. At the same time, the relatively long-term follow-up allowed for a more thorough recording of recurrence events. While the initial sample size calculation indicated the need for 52 patients per group, over 60 patients per group were recruited (actual n = 65-70) to compensate for potential dropouts. Consequently, the final analyzable sample size in each group exceeded the minimum requirement, further strengthening the reliability of the findings. Moreover, post-hoc analyses confirmed the ability to detect significant differences among the three groups. Future multi-center, prospective studies with stan

For the treatment of grade I internal hemorrhoids, ERBL, IS, and ESB all demonstrated comparable and sustained long-term efficacy, without significant differences in the rates of adverse reactions. ESB exhibited to be the most effective endoscopic approach for managing grade II-III internal hemorrhoids, yielding a significantly lower recurrence rate than IS and fewer postoperative adverse events than ERBL. Preoperative decision-making plays a notable role in the mana

| 1. | Ma W, Guo J, Yang F, Dietrich CF, Sun S. Progress in Endoscopic Treatment of Hemorrhoids. J Transl Int Med. 2020;8:237-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mou AN, Wang YT. Endoscopic polidocanol foam sclerobanding for treatment of internal hemorrhoids: A novel outpatient procedure. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:4583-4586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang JY, Peery AF, Lund JL, Pate V, Sandler RS. Burden and Cost of Outpatient Hemorrhoids in the United States Employer-Insured Population, 2014. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ashburn JH. Hemorrhoidal Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Qu CY, Zhang FY, Wang W, Gao FY, Lin WL, Zhang H, Chen GY, Zhang Y, Li MM, Li ZH, Cai MH, Xu LM, Shen F. Endoscopic polidocanol foam sclerobanding for the treatment of grade II-III internal hemorrhoids: A prospective, multi-center, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:3326-3335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mishra S, Sahoo AK, Elamurugan TP, Jagdish S. Polidocanol versus phenol in oil injection sclerotherapy in treatment of internal hemorrhoids: A randomized controlled trial. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2020;31:378-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xie YT, Yuan Y, Zhou HM, Liu T, Wu LH, He XX. Long-term efficacy and safety of cap-assisted endoscopic sclerotherapy with long injection needle for internal hemorrhoids. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:1120-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tutino R, Massani M, Jospin Kamdem Mambou L, Venturelli P, Della Valle I, Melfa G, Micheli M, Russo G, Scerrino G, Bonventre S, Cocorullo G. A Stepwise Proposal for Low-Grade Hemorrhoidal Disease: Injection Sclerotherapy as a First-Line Treatment and Rubber Band Ligation for Persistent Relapses. Front Surg. 2021;8:782800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | van Oostendorp JY, Grossi U, Hoxhaj I, Kimman ML, Kuiper SZ, Breukink SO, Han-Geurts IJM, Gallo G. Limitations of the Goligher classification in randomized trials for hemorrhoidal disease: a qualitative systematic review of selection criteria. Tech Coloproctol. 2025;29:133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gallo G, Picciariello A, Pietroletti R, Novelli E, Sturiale A, Tutino R, Laforgia R, Moggia E, Pozzo M, Roveroni M, Bianco V, Realis Luc A, Giuliani A, Diaco E, Naldini G, Trompetto M, Perinotti R, D'Andrea V, Lobascio P. Sclerotherapy with 3% polidocanol foam to treat second-degree haemorrhoidal disease: Three-year follow-up of a multicentre, single arm, IDEAL phase 2b trial. Colorectal Dis. 2023;25:386-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. |

Pata F, Bracchitta LM, D'Ambrosio G, Bracchitta S. Correction: Pata et al. Sclerobanding (Combined Rubber Band Ligation with 3% Polidocanol Foam Sclerotherapy) for the Treatment of Second- and Third-Degree Hemorrhoidal Disease: Feasibility and Short-Term Outcomes. |

| 12. | Bracchitta S, Bracchitta LM, Pata F. Combined rubber band ligation with 3% polidocanol foam sclerotherapy (ScleroBanding) for the treatment of second-degree haemorrhoidal disease: a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:1585-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wald A, Bharucha AE, Limketkai B, Malcolm A, Remes-Troche JM, Whitehead WE, Zutshi M. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Management of Benign Anorectal Disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1987-2008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Abiodun AA, Alatise OI, Okereke CE, Adesunkanmi AK, Eletta EA, Gomna A. Comparative study of endoscopic band ligation versus injection sclerotherapy with 50% dextrose in water, in symptomatic internal haemorrhoids. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2020;27:13-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Figueiredo MN, Campos FG. Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal dearterialization/transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization: Technical evolution and outcomes after 20 years. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Gallo G, Grossi U, De Simone V, Picciariello A, Diaco E, Fan P, He H, Li J, Lin H, La Torre M, Laforgia R, Lobascio P, Ma H, Pata F, Perinotti R, De Parades V, Pozzo M, Realis Luc A, Salgueiro P, Skowronski A, Sun P, Trompetto M, Tutino R, Wang C, Wang Z, Wang Z, Wu J, Zhang Y, Zhao S, Zeng X, Fernandes V, Moser KH, Ren D, Sileri P, Gravante G. Real-world use of polidocanol foam sclerotherapy for hemorrhoidal disease: insights from an international survey and systematic review with clinical practice recommendations. Updates Surg. 2025;77:1439-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rubbini M, Tartari V. Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation with hemorrhoidopexy: source and prevention of postoperative pain. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:625-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Watson EGR, Qin KR, Smart PJ, Burgess AN, Mohan HM, Proud DM. Local anaesthetic infiltration in rubber band ligation of rectal haemorrhoids: study protocol for a three-arm, double-blind randomised controlled trial (PLATIPUS trial). BMJ Open. 2023;13:e067896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Albuquerque A. Rubber band ligation of hemorrhoids: A guide for complications. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:614-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | van Tol RR, Kleijnen J, Watson AJM, Jongen J, Altomare DF, Qvist N, Higuero T, Muris JWM, Breukink SO. European Society of ColoProctology: guideline for haemorrhoidal disease. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:650-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Davis BR, Lee-Kong SA, Migaly J, Feingold DL, Steele SR. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:284-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Rao AG, Nashwan AJ. Redefining hemorrhoid therapy with endoscopic polidocanol foam sclerobanding. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:4021-4024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/