Published online Feb 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.113505

Revised: September 18, 2025

Accepted: December 15, 2025

Published online: February 7, 2026

Processing time: 154 Days and 15.3 Hours

Low drug concentrations have been linked to antidrug antibody (ADA) forma

To explore the predictive value of initial IFX clearance on outcomes and assess the impact of Bayesian model (iDose)-guided IFX dosing on clearance and outcomes during induction and early maintenance treatment.

Data from a Phase 3 study of 220 CT-P13/originator IFX-treated patients with Crohn’s disease were used to develop probability models for outcomes including mucosal healing (MHEAL), biomarker response [C-reactive protein (CRP)], ADA development, a composite endpoint and time to first ADA formation, based on initial clearance. Subsequently, patients with characteristics suggesting rapid ini

In the CT-P13 study, population pharmacokinetic was consistent with previously published models. Initial clearance was a significant predictor of several outcomes including MHEAL, CRP normalization, a composite

endpoint ((1) CDAI at week 54 was at least 150 points less than baseline; (2) MHEAL at week 54; (3) CRP was in normal range at week 54; and (4) FCP was less than 250 at week 54) and ADA formation. In the proof-of-concept study, 10 patients received iDose-guided IFX treatment. Initial clearance ranged from 0.017 L/day to 1.11 L/day, prompting up to three IFX infusions within the first 2 weeks. Two patients were discontinued due to ADA. Gene

Initial IFX clearance correlates with efficacy metrics and ADA formation. These probability curves may be useful to identify patients at risk of treatment failure or ADA who may benefit from individualized therapy. iDose-guided treatment successfully achieved targeted serum IFX concentrations, reducing risk of ADA formation. Proactive therapeutic drug monitoring and targeted dosing based on early IFX clearance may improve treatment outcomes for patients with IBD.

Core Tip: There have been several evaluations of the relationship between therapeutic antibody clearance and outcomes. Data from a large study in patients administered infliximab at the labeled dose were used to assess the probability of antidrug antibodies, C-reactive protein normalization, and mucosal healing based on baseline clearance. A compassionate use study further evaluated these correlations, and clearance often decreased from baseline due to individualized dosing, suggesting improvements in the probability of all outcomes. While this study was small, the results are encouraging and suggest that further research on the use of clearance as a therapeutic endpoint is warranted in this area.

- Citation: Mould DR, Kutschera M, Primas C, Reinisch S, Novacek G, Lichtenberger C, Dervieux T, Bae Y, Lee SH, Lee JH, Reinisch W. Identification of strong correlations of clearance with clinical outcomes for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(5): 113505

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i5/113505.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.113505

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is viewed as a system-level perturbation at the interface of the intestinal mucosal immune system and the commensal ecosystem[1]. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a key cytokine contributing to IBD pathogenesis[2]. Anti-TNF-α therapy has become a mainstay of IBD treatment, with drugs such as infliximab (IFX) proven to induce and maintain remission, induce mucosal and fistula healing, and achieve significant clinical im

Low IFX concentration is a major risk factor for PNR and SLR during induction and maintenance treatment[8,9]. Exposure-response relationships have consistently demonstrated that low troughs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Crohn’s disease (CD), and ulcerative colitis (UC) are predictive of SLR[10,11]. Consequently, antidrug antibodies (ADAs) and accelerated clearance (CL) are major factors contributing to SLR[12]. Therefore, one of the goals during induction should be avoiding subtherapeutic IFX exposure[13,14]. This can be achieved through adequate therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), enabling proactive dose adjustment to maintain effective IFX concentrations[15]. There have been many papers written on the benefits of prospective TDM[15,16]. However, data on proactive TDM during induction with biologics are scarce[17] although this has been tested in clinical trials[18] in patients with IBD and is becoming more common in patients with acute severe UC where studies investigated accelerated induction regimen where patients received 3 induction doses of IFX within a median period of 24 days[19] or evaluated dose intensification to re-establish clinical response[20] and is becoming more common owing to accelerated IFX CL in these patients[21].

Personalized dosing has become an important research topic[22-25]. Bayesian dashboard systems, which enable personalized dosing, make use of pre-existing population pharmacokinetic (PPK) models combined with information acquired from TDM and patient factors to develop a personalized dosing program[26]. Individual PK behavior is inferred from patient data including patient factors, the administered dose, and post-dose time course of IFX concentration[26-28]. A Bayesian dashboard system has been developed for IFX[27]. The software (iDose®) (Baysient LLC, Fort Myers, FL, United States) is a Bayesian dashboard system using these concepts developed to facilitate IFX dosing by determining individualized regimens that would meet or exceed physician-selected serum troughs for each dose[27,28].

The present work aimed to develop a PPK model using the original data from 220 patients with CD who were treated either with originator IFX or biosimilar CT-P13 in a randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov No. NCT02096861). Logistic regression was conducted to correlate individual initial IFX CL (estimated by the PPK model) with the probability of mucosal healing (MHEAL), CRP normalization, a composite endpoint (1) CDAI at week 54 was at least 150 points less than baseline; (2) MHEAL at week 54; (3) CRP was in normal range at week 54; and (4) FCP was less than 250 at week 54 and ADA formation among other endpoints using individual outcomes data from this study. The second part of this evaluation was to conduct a proof-of-concept evaluation using a small compassionate use protocol to treat patients with IBD who were expected to have fast clearance. iDose was then used prospectively in 10 patients, using iDose to forecast appropriate dosing intervals to avoid underdosing, providing clearance estimates for each patient at each dose to see if appropriate dosing would improve the probability of MHEAL and CRP outcomes and reduce the initial probability of ADA formation during induction and early maintenance treatment with IFX.

Data from the CT-P13 3.4 randomized, Phase 3 trial comparing biosimilar and originator patients in IFX with active CD, herein referred to as the CT-P13 study (ClinicalTrials.gov No. NCT02096861), were obtained with permission from Celltrion, Inc. (Incheon, South Korea). The study design, ethics approval, and eligibility criteria, as well as baseline characteristics of randomized patients, have been published previously[29]. In summary, 220 biologic-naive patients with moderately to severely active CD (CD Activity Index [CDAI]: 220 to 450) were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms, with treatment switches occurring at week 30: CT-P13 followed by CT-P13; CT-P13 followed by originator IFX; originator IFX followed by originator IFX; and originator IFX followed by CT-P13. In total, 214 randomly assigned patients (as per 107 patients initiating each drug[29]) were required to achieve at least 85% power for a non-inferiority margin of -20% with a one-sided α level of 0.025. In the sample size calculation, the therapeutic non-inferiority of CT-P13 to IFX was based on a response rate of 64.5%, as defined by CDAI-70 at week 6. The non-inferiority margin was defined as -20% to preserve 50% effectiveness of IFX and was selected based on data from previous randomized controlled trials. Non-inferiority of CT-P13 to IFX with respect to response rates would be met for the primary endpoint if the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the difference between CT-P13 and IFX was greater than the non-inferiority margin of -20%. IFX concentrations were evaluated using an in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) utilizing the bioaffy 1000 HC compact-disc microfluidic cartridges using Gyrolab xP workstation (Gyros Protein Technologies, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to measure the concentration of CT-P13 in human serum. The lower limit of quantitation of the assay was 200 ng/mL. The assay was validated according to regulatory guidance.

Patients were treated with 5 mg/kg intravenous IFX infusions following standard induction (weeks 0, 2, and 6) and maintenance regimens (every 8 weeks). The study duration was 54 weeks, with baseline and end-of-study ileo-colonoscopies that were centrally read.

A detailed description of procedures for the CT-P13 study has been published previously[29]; procedures are summarized in Supplementary Figure 1. Briefly, serum samples for ADA testing were collected before study drug administration at weeks 0, 14, 30, and 54. Blood samples for PK analysis were collected on dosing days at weeks 2, 6, 14, and 22, before drug administration (Cmin) and within 15 minutes after the end of the IFX infusion at weeks 0, 2, 6, and 14 (Cmax). Stool samples for FCP testing were collected on weeks 0, 6, 14, 30, and 54, and blood samples for assessment of CRP were drawn prior to study drug administration at the same time points. MHEAL was defined in the CT-P13 study as a simplified endoscopic activity score for CD (SES-CD) ≤ 2, i.e. absence of mucosal ulcers. Clinical remission was defined as CDAI < 150.

The PPK model was developed using data from the CT-P13 study with an approach similar to those described previously[30-33]. Data were fitted using NONMEMTM version 7.4.4 (Icon Development Solutions, Dublin, Ireland)[34]. The model was qualified by assessment of goodness of fit plots, a visual predictive check, and a nonparametric bootstrap.

The first estimated individual CL (i.e. from the first sample taken for serum IFX concentration measurement) for each patient in the final CT-P13 model was merged with baseline demographic data as well as selected clinical endpoints. The data were fitted with binary logistic regression analyses using R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and complete case analysis was undertaken. The probability of outcome at week 54 vs predictors of interest (sex, age, body weight, disease duration, IFX dose, and initial IFX CL) were evaluated, and for endpoints that were statistically significantly associated with initial CL, logistic plots along with 95%CI were created. Following this, a time to first ADA detection model was developed with data from the CT-P13 study, using a Cox proportional-hazards model in R. For this evaluation, 7 patients with ADAs present at baseline were excluded. Baseline covariates evaluated in this analysis comprised sex, age, body weight, disease duration, IFX dose, initial IFX CL, and concomitant immunomodulator use. Continuous covariates were divided into quartile bins. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were binned based on identified covariates and then Kaplan-Meier plots were evaluated by covariate bin. Hazard ratios and probability of ADA formation at time points of interest were calculated for significant covariates.

At the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna (Vienna, Austria) patients were enrolled: (1) With an established diagnosis of IBD; (2) Who were IFX-naive; and (3) Who had evidence suggesting rapid initial IFX CL, such as low serum albumin and/or high serum CRP levels that, at the discretion of the treating physician, reduced the likelihood of response to a standard IFX induction regimen (5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6). Eligible patients participated in a compassionate use program of iDose-guided early individualized dosing of IFX, based on dense TDM. Per advice from the institutional review board of the Medical University of Vienna, up to 10 patients could be treated in this compassionate use program to comply with the Austrian Medicinal Products Act. All patients gave informed consent prior to treatment. There was no control arm in this study, all patients were dosed using the iDose system recommendations, patients 2 and 10 were not included, thus patient numbering is not continuous.

The primary objective of the compassionate use program was to determine the probabilities associated with baseline CL for these patients, and to determine if initial clearance defines the outcome or whether the outcomes could be changed with appropriate dosing. A secondary objective was to achieve targeted serum IFX concentrations during induction and early maintenance treatment in patients with IBD with factors suggesting rapid initial drug CL.

The first IFX dose was between 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, at the discretion of the treating physician. The timing and doses of subsequent doses were calculated by iDose, using measured serum IFX concentrations (Supplementary Figure 2) to achieve targeted serum concentrations over a pre-defined duration of up to 120 days. Between 3 days and 6 days after the first IFX dose, two samples were collected on two consecutive days, which were used by iDose to determine the timing and dose of the second infusion. Selected dose regimens were between approximately 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, the dose intervals were adjusted to maintain the target troughs. Three IFX target trough thresholds were determined for different time intervals: ≥ 27 μg/mL for days 3-14, ≥ 17 μg/mL for days 15-42, and 7-10 μg/mL for days 43-120. These thr

Free serum IFX was determined by ELISA (IDKmonitor® IFX drug level ELISA, Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany) using an automated ELISA processor (Dynex DS2®; Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA, United States). The assay was limited to IFX concentrations up to 45 μg/mL; samples with higher IFX serum concentrations were diluted to allow quantification. FCP levels were determined by ELISA (BÜHLMANN fCAL® ELISA; BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG, Schönenbuch, Switzerland) using an automated ELISA processor (Dynex DS2®). Sample preparation was performed using a manual extraction procedure, with sample dilution expanded by a factor of 3 to give a working range of 30-1800 μg/g. ADA levels were determined using a drug tolerant homogenous mobility shift assay at Prometheus Laboratories (San Diego, CA, United States), as previously described[37].

Agreement between observed and iDose predicted IFX concentrations was assessed by median absolute percentage error (MDAPE), which is used to evaluate the performance of machine learning algorithms or Bayesian systems such as iDose. MDAPE is the median of all absolute percentage errors calculated between predictions and corresponding actual values. For the CT-P13 data, the median MDAPE value was 5% (range 0%-63%), with the upper limit of the range being associated with an apparent dose error; The next highest MDAPE in the database was 19%. The probability models from CT-P13 were used to calculate the probabilities of MHEAL, CRP normalization and developing ADAs for the iDose-guided patients. CRP and FCP values were also graphically examined, allowing assessment of whether individualized therapy might reduce the probability of a poor outcome for patients with high initial IFX CL.

The PPK model developed using the data from CT-P13 was a two compartment models with linear clearance. The model included the effect of albumin, weight, ADA, CRP, serum glucose and concomitant immunomodulator use on CL. Weight was found to be influential of the central and peripheral volumes of distribution and inter-compartmental clearance. These results were consistent with previously published models of IFX in both pediatric[38,39] and adult[40-42] patients with IBD. There was no difference between the biosimilar and originator IFX. Model evaluation was conducted using standard approaches and the model was judged to adequately describe the data.

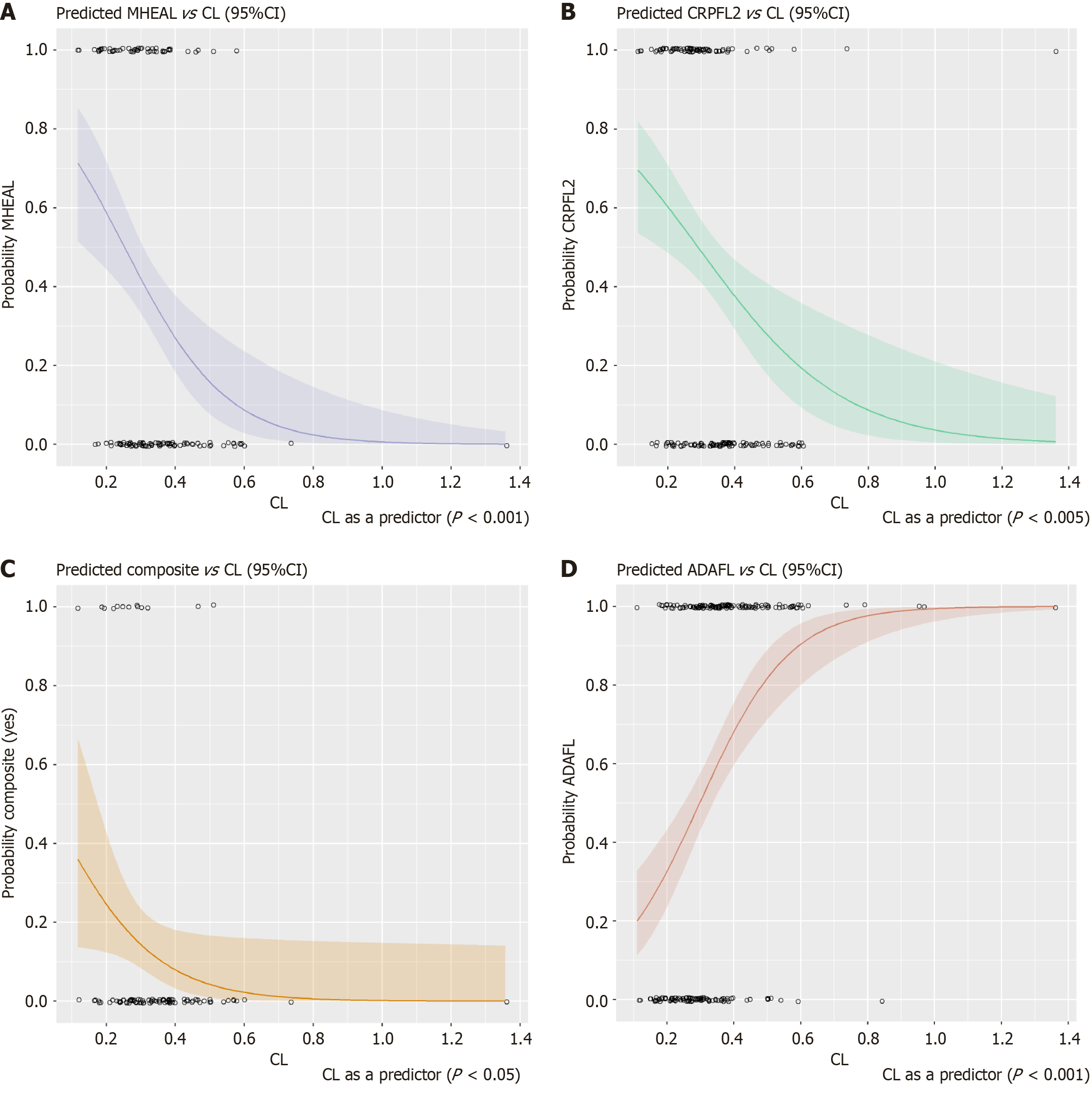

In total, 22% of patients in the CT-P13 study achieved MHEAL (SES-CD ≤ 2) at week 54. The final PK model was used to estimate initial IFX CL, which was identified as the only significant predictor for MHEAL (P = 0.000697) (Figure 1A). The probability of MHEAL significantly decreases as CL increases. On average, the odds of MHEAL decreases about half for every 0.1 increase in CL. Overall, 90% of patients had serum CRP levels within the normal range (< 10 mg/L) at week 54, and this was significantly associated initial IFX CL (P = 0.00276) (Figure 1B). On average the probability of CRP normalization at week 54 decreases by more than half for every 0.1 increase in CL. Patient age (P = 0.129) and disease duration (P = 0.0878) were also identified but were not significant. For clinical remission (CDAI < 150), no significant predictors were identified at either week 30 or week 54. FCP normalization to < 250 μg/g, among patients with FCP ≥ 250 μg/g at baseline, was not predicted by initial IFX CL. However, a composite endpoint comprised of 4 endpoints [(1) CDAI at week 54 was at least 150 points less than baseline; (2) MHEAL at week 54; (3) CRP was in normal range at week 54; and (4) FCP was less than 250 at week 54] was also tested. Only IFX CL was a statistically significant predictor of achieving this composite endpoint (P = 0.0461). The logistic regression plot for the combined endpoint is shown in Figure 1C.

Overall, 57% of all patients had developed ADAs at week 50 of the CT-P13 study. Initial IFX CL (P = 0.000000467), patient age (P = 0.0897), and IFX dose (P = 0.105) were identified as being predictive of ADA formation, although IFX CL was the only significant predictor of developing ADA at any time point analyzed (weeks 14, 30, 54, and end-of-study) with the probability of ADA more than doubling for every 0.1 L/day increase in CL (Figure 1D). The logistic regression parameters for these four logistic models are provided in Supplementary Tables 1-4. A box and whisker plot of quartiles of CL by responder status is shown in Supplementary Figure 3. The sizes of each box reflect the numbers of patients in each category (quartile and responder status).

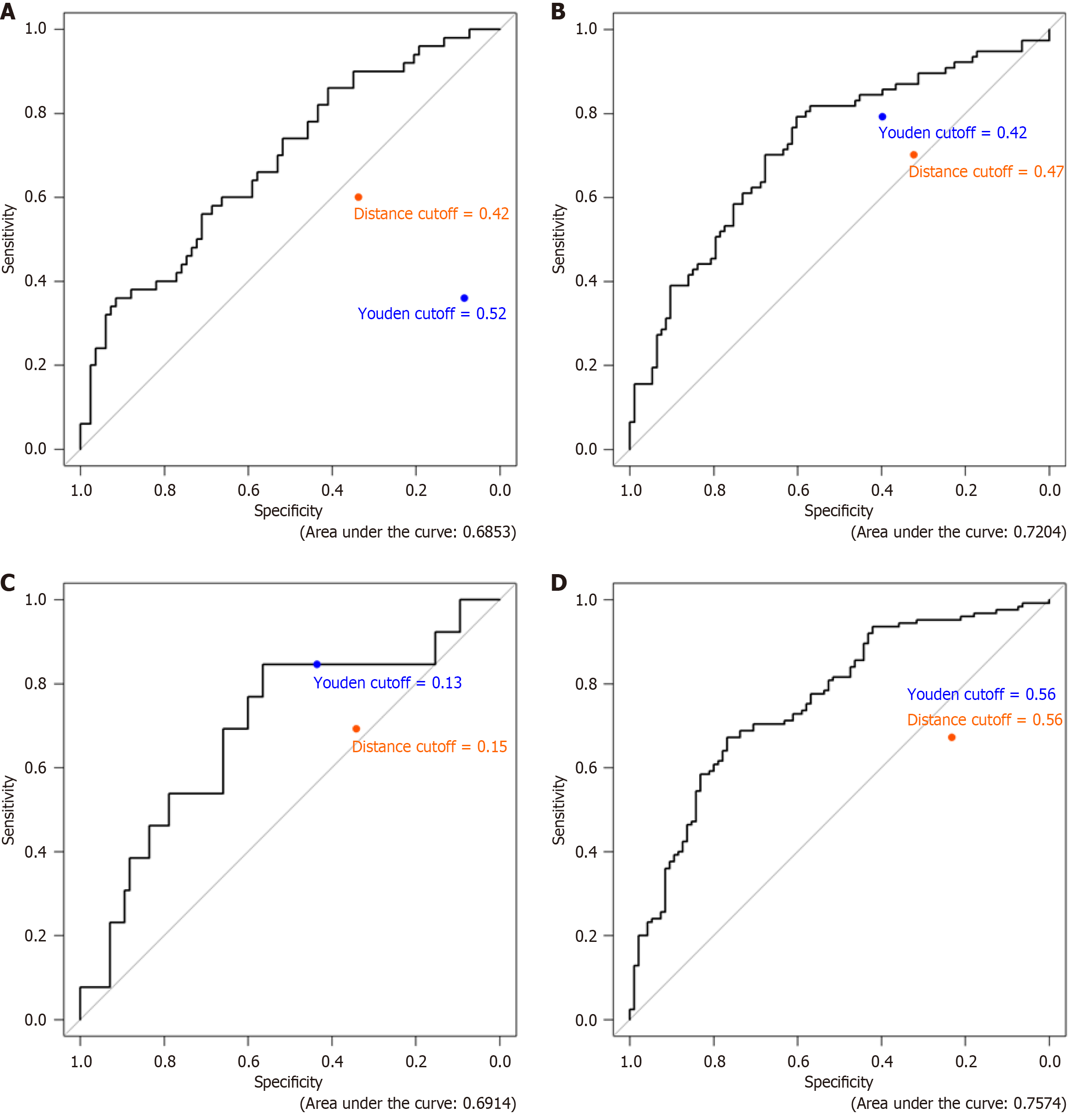

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis was performed on all four endpoints. The ROC for MHEAL is shown in Figure 2A, the ROC for CRP is shown in Figure 2B, the ROC for the combined endpoint is shown in Figure 2C and the ROC for ADA is shown in Figure 2D. The cut-off in a ROC refers to the threshold value that determines the classification of a test result as positive or negative. This value is crucial as it affects the sensitivity and specificity of the test. The ROC curve plots the sensitivity (true positive rate) against 1-specificity (false-positive rate) at various cut-off points. The optimal cut-off point is determined by the point on the ROC curve closest to (0, 1), which represents a test with perfect sensitivity and specificity. The area under the curve (AUC) is a measure of the overall performance of the diagnostic test, with a higher AUC indicating better predictive power. This process involves maximizing Youden’s index or minimizing Euclidean distance which is shown on each figure and reflects the ‘cutoff value’ for CL for each of these endpoints.

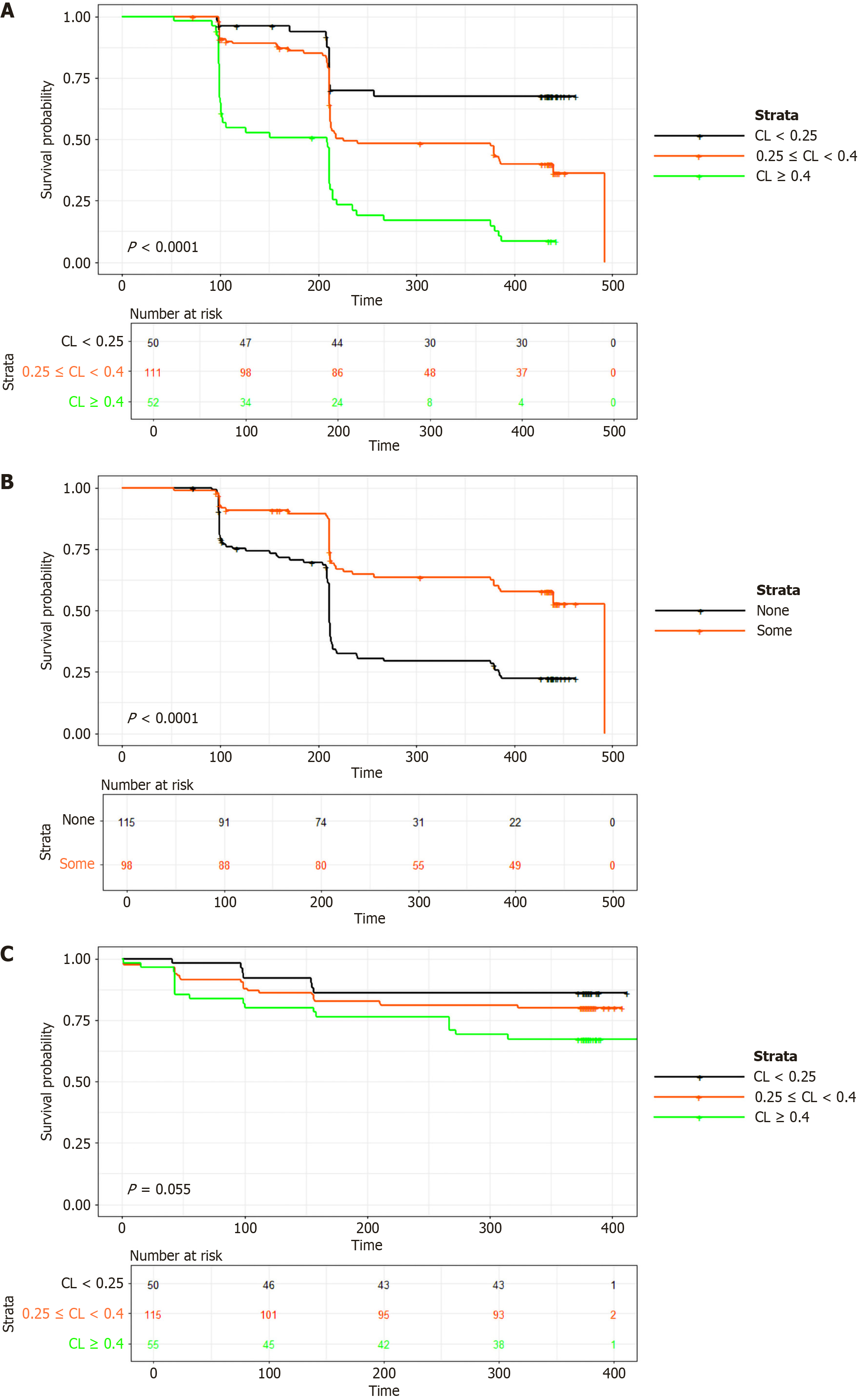

Initial IFX CL (P = 0.0001), and concomitant immunomodulator use (P = 0.0001) were identified as significant predictors of time to first ADA formation (Figure 3A and B respectively). Dose was identified as a predictor but was not significant (P = 0.29). The model suggested that the hazard ratio for developing ADAs increased by 61% for every 0.1 L/day increase in CL, and decreased by 41% with concomitant immunomodulator use. For dose, the hazard decreased by 29% for every 100 mg increase in dose. A lower initial CL was associated (P = 0.055) with a longer IFX treatment duration (Figure 3C). Low initial CL was defined as < 0.25 L/day, the mid-range of initial CL was defined as ≥ 0.25 L/day to ≤ 0.4 L/day, and high initial CL was defined as > 0.4 L/day. The Cox proportional hazard function and its associated parameters are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Between October 5, 2018 and December 9, 2019, 10 adults (7 with UC and 3 with CD) were consecutively enrolled for proactive iDose-guided IFX dosing. Detailed baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Two patients had undergone major surgery (patient 1: Permanent ileostomy, patient 9: Proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis) prior to treatment. All patients had active disease with elevated CRP and/or FCP levels. Patient 6 who previously had increased FCP concentrations, however, presented with normal CRP and only slightly increased FCP levels on the day of first IFX administration. Five patients had prior exposure to ≥ 2 biologics.

| Patient number | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 |

| Baseline | ||||||||||

| Sex | M | F | F | F | M | F | M | F | M | M |

| Age (years) | 49 | 18 | 32 | 19 | 39 | 22 | 45 | 36 | 62 | 23 |

| Body weight (kg) | 44 | 55 | 58 | 50 | 99 | 53 | 95 | 63 | 84 | 63 |

| Diagnosis | CD | UC | UC | UC | CD | CD | UC | UC | UC | UC |

| CD disease location | Ileocolonic | NA | NA | NA | Upper GI ileal | Ileocolonic | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| UC disease extent | NA | Extensive | Left-sided | Extensive | NA | NA | Left-sided | Extensive | Extensive | Left-sided |

| Disease duration (years) | 31 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.86 | 11.71 | 5.36 | 1.79 | 0.27 | 3.98 | 4.56 | 3.07 | 0.32 | 4.78 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 27.3 | 37.5 | 33.4 | 34.1 | 41.6 | 35.4 | 35.9 | 38.8 | 39.6 | 34.9 |

| FCP (μg/g) | 1560 | 3888 | 4360 | 3572 | 113 | 13024 | 1659 | 502 | 1597 | 12295 |

| Concomitant steroids/immunosuppressants | PRED 20 mg/day; AZA 100 mg/day | AZA 100 mg/day | AZA 100 mg/day | PRED 20 mg/day | None | MTX 15 mg/week | PRED 10 mg/day | None | PRED 10 mg/day | PRED 15 mg/day; 6-MP 50 mg/day |

| Prior biologic exposure | Yes (IFX, ADL, UST) | No | No | No | No | Yes (UST, IFX, ADL, GOL, VDZ) | Yes | Yes (VDZ, IFX, ADL, GOL) | Yes (ADL, VDZ) | Yes (ADL, GOL) |

| First IFX dose (mg/kg) | 4.5 | 5.4 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| Day 120 | ||||||||||

| Observation period (months) | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 31 |

| Body weight (kg) | 67 | 58 | 60 | 53 | 98 | 104 | 82 | 77 | ||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.7 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 1.19 | 2.35 | 0.26 | ||

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.0 | 50.8 | 45.9 | 45.1 | 43.5 | 47.9 | 34.2 | 43.8 | ||

| FCP (μg/g) | 35 | 246 | 60 | 138 | 112 | 2690 | 467 | 176 | ||

| Number of IFX doses received | 7 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

The highest initial IFX CL was 0.652 L/day (Table 2), prompted five IFX doses to be administered within 60 days. The lowest initial IFX CL of 0.202 L/day resulted in five infusions administered in line with the standard IFX regimen (5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, and every 8 weeks thereafter). Up to day 14, 31 of the 36 serum IFX concentration measurements were above the target (≥ 27 μg/mL). The first trough concentration of patient 1 was below the threshold, as were those from patients 7 and 9, in whom ADAs were detected early during induction treatment (at days 9 and 12, respectively; Table 1). Both patients 7 and 9 discontinued treatment early during induction, after 20 and 12 days, respectively. Patient 9 reported previously failed exposure to IFX only after receiving the first IFX dose during the compassionate use program; ADAs were subsequently identified in the baseline serum sample from that patient.

| Patients | CL (L/day) | Probability of MHEAL | Probability of CRP normalization | Probability of ADA |

| 1 | 0.6236 | 7.42 | 19.19 | 94.47 |

| 3 | 1.1102 | 0.73 | 3.95 | 100.00 |

| 4 | 0.3160 | 39.44 | 47.78 | 56.62 |

| 5 | 0.0168 | 73.32 | 70.22 | 18.14 |

| 6 | 0.2722 | 46.50 | 52.49 | 47.96 |

| 7 | 0.3937 | 28.18 | 39.42 | 71.38 |

| 8 | 0.6329 | 7.07 | 18.56 | 94.78 |

| 9 | 0.6095 | 7.94 | 20.15 | 93.99 |

| 11 | 0.4288 | 23.95 | 35.99 | 76.34 |

| 12 | 0.5125 | 14.82 | 28.13 | 86.66 |

From days 15-42, 20 of the 22 serum IFX concentration measurements were above the target (≥ 17 μg/mL), with patient 7 accounting for one of the below-threshold concentrations. Finally, 27 of the 39 serum IFX concentration measurements between day 43 and day 120 were in the target range (7-10 μg/mL). The majority of the low serum concentrations were only marginally inferior to the target levels, and were mostly attributed to delays in dosing, apart from patient 5 who had a concomitant congenital hematological disorder that may have represented an unknown covariate and led to a more rapid CL than predicted.

When comparing observed with iDose-predicted serum IFX concentrations, the overall median MDAPE was 18% (range 6-28, 5.37%). Comparative courses for observed and predicted serum IFX concentrations and MDAPE values and the CRP over time for individual patients are shown in Supplementary Figure 4. The highest MDAPE was from one of the two patients that developed ADAs early in treatment and had a sudden, large increase in IFX CL for their second (and last) PK sample. The next highest MDAPE was an ID that had an unexpectedly low trough concentration, but otherwise the MDAPE was lower. For patients developing ADAs, the observed values were generally lower than the predicted values; ADA status was not available during the compassionate use program. Overall, the agreement between observed and predicted values was acceptable.

At baseline, probabilities of ADA formation ranged from 18.14% to 100%, probabilities of MHEAL ranged from 7.3% to 73.32% and the probability of CRP normalization ranged from 3.95% to 70.22% (Table 2). As described, ADA formation was observed in 2 of the 10 patients, both of whom developed ADAs early during induction treatment. These patients had initial IFX CL of 0.394 L/day (patient 7) and 0.610 L/day (patient 9).

Patient 1 saw a reduction in CL and this effected the probability outcomes leading to a stabilization in all 3 measurements: CRP normalization, MHEAL and ADA. However careful consideration needs to be given to how albumin levels can impact CL. Patient 1 had albumin levels ranging from 27.3-41.3 g/L. Patient 3 had albumin levels ranging from 36.1-51.4 g/L and serve as good examples of CL effect over time on these probability outcomes.

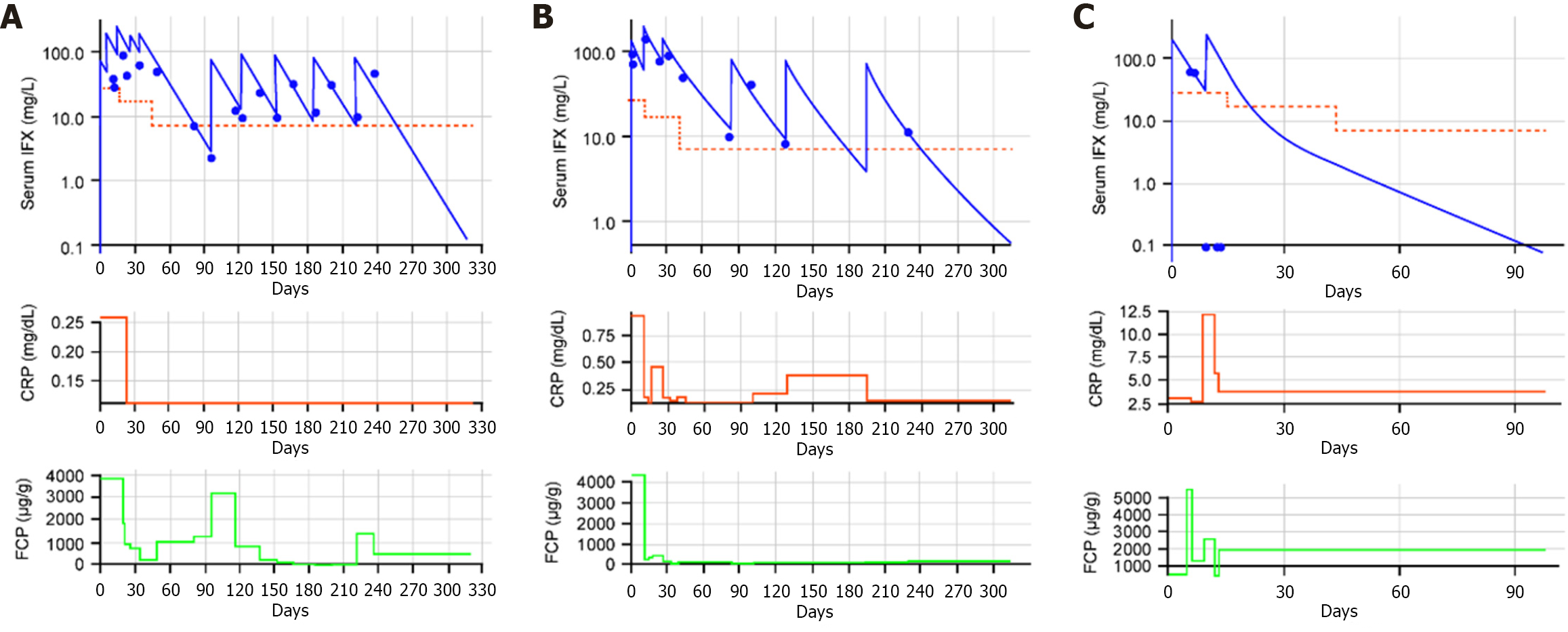

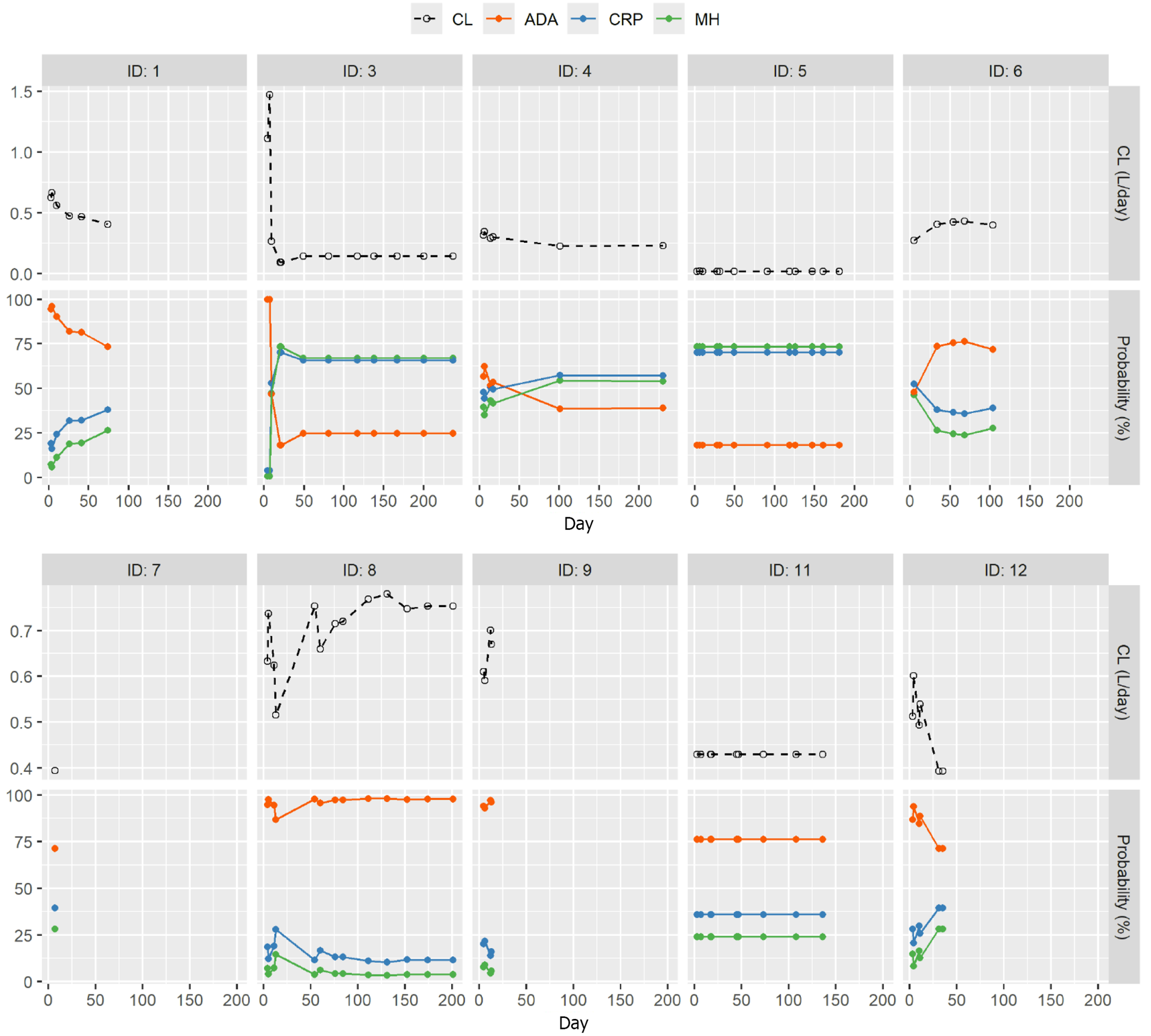

The individual courses of IFX CL, serum CRP levels, and FCP levels are shown in Figure 4 for three patients, and Supplementary Figure 4 shows the individual PK data and CRP for all patients. Patients with serum IFX concentrations exceeding targeted thresholds in addition to rapidly reduced initial CL showed early improvements in inflammatory biomarker levels, as demonstrated for patients 1 and 12. Both patients had a high initial CL that was substantially slowed by adapted iDose-guided dosing, resulting in rapid and significant decreases in CRP and FCP levels. Interestingly, on occasions when IFX dosing was delayed relative to the infusion day recommended by iDose, subsequent increases in CRP and FCP levels were identified. In addition, as shown in Figure 5, as patient clearance slowed (e.g., patients 1, 3 and 12) the probability of MHEAL and CRP normalization improved and the probability of ADA decreased. For those patients whose CL increased (e.g., patients 6, 8 and 9) the reverse trends in probability were seen. This suggests that the probability of both good and bad outcomes seen with baseline clearance may be changed with appropriate or inappropriate dosing.

iDose-guided IFX treatment was well tolerated. Despite two patients discontinuing the compassionate use program owing to ADA development, no other adverse effects were reported and there were no serious infections, cardiovascular events, thromboses, malignancies or deaths.

Approximately 3 years after starting iDose-guided IFX treatment, 4 of the 10 patients (patients 1, 3, 4, and 12) included in the compassionate use program remained on IFX. Four patients discontinued the treatment within a year: Two patients owing to SLR (patients 8 and 11), and two due to ADA formation (patients 7 and 9). Two patients were lost to follow-up (patients 5 and 6).

While IFX is a highly effective therapy for many patients with IBD, a significant proportion are either PNR or develop SLR[5,19]. In many cases, treatment failure may be a consequence of low drug exposure, secondary to the development of ADAs and/or high drug CL[43-46]. As such, the potential roles of proactive TDM[47] and dashboard-driven dosing have been recognized as increasingly important in the management of IBD[48-50], with the PRECISION trial demonstrating that Bayesian dashboard-guided dosing significantly reduced the rate of loss of response during maintenance IFX treatment for patients in clinical remission[27].

Data from the CT-P13 study were used to assess the prognostic value of initial IFX CL in patients with CD. This analysis found that initial IFX CL was a major predictor of MHEAL, in keeping with previous reports in patients with UC[44]. Initial CL was a predictor of CRP normalization and was the only predictor for the combined endpoint. Initial IFX CL was also a major predictor of ADA formation, with higher baseline CL associated with an increased risk, as well as time to first ADA formation. In contrast, higher IFX dose and concomitant immunosuppressant use decreased the risk of ADA formation. The association between initial IFX CL and ADA formation aligns with findings from a recent study evaluating IFX PK using data from clinical studies of CT-P13 in patients with RA and ankylosing spondylitis[43]. Studies analyzing the PK of IFX in patients with IBD have identified various factors predictive higher IFX CL, including presence or ADAs, higher body weight, and lower albumin[33,37-39]. Predicting initial IFX CL from parameters at baseline, before the first IFX treatment, might help to identify patients at higher risk of developing ADA. This may, therefore, reduce the risk of ADA and subsequent loss of response.

Since there were evaluations (e.g., 27 and 28) that indicated the use of individualized dosing would work, this proof-of-concept study was developed using a Bayesian dashboard system (iDose)-guided IFX dosing. iDose was utilized for induction and early maintenance therapy in 10 patients with IBD, demonstrating the potential of this approach for avoiding underdosing, reducing initial rapid IFX CL, and facilitating improved clinical outcomes. This hypothesis was tested in 10 patients with IBD considered to have a reduced likelihood of response to a standard IFX induction regimen and included in a compassionate use program. Baseline parameters were assessed before the first IFX dose and were longitudinally measured for up to 120 days. The exact date of IFX administration was forecast by iDose based of different assessments (e.g., albumin, weight, concomitant immunomodulators, disease severity) using a dense sampling approach. Longitudinal measurement of these assessments, including serum IFX levels, allowed calculation of IFX CL both initially and at subsequent time points. Furthermore, the use of TDM meant underdosing of patients could be proactively avoided, aiming to improve the chance of achieving better clinical outcomes. Indeed, by using TDM and iDose-guided dosing, therapeutic treatments were individually tailored to account for patient CL and to maintain a target trough concentration determined by the treating physician. CL was shown to impact outcomes: When CL decreased in individual patients, the probability of CRP normalization, MHEAL and ADA improved. When CL increased the probability of MHEAL and CRP also declined while ADA increased. Patient 1 had an initial CL of 0.6236 L/day and probability outcomes of MHEAL 7.42%, CRP healing 19.19% and ADA 94.47%. By the end of treatment this patient’s CL fell to 0.41 with probabilities of MHEAL increased to 26.01%, CRP healing increased to 37.71% and ADA decreased to 73.99%. All improvements over the initial estimated probabilities. This suggests that a patient’s initial CL is not definitive in how it effects probability outcomes. Therefore, monitoring patient CL may be a useful indicator of patient response.

Overall, iDose-guided dosing was effective in maintaining target IFX concentrations, with corresponding reductions in inflammatory biomarkers, and an acceptable safety profile. These findings are further supported by the long-term outcomes for these patients, with 4 of the 10 patients remaining on IFX approximately 3 years after starting iDose-guided treatment. This is a notable finding, given that these patients had a high probability of either losing response or developing ADAs owing to their baseline characteristics, particularly initial CL. A larger prospective study is currently being conducted to evaluate individualized dosing which may confirm these findings[51].

The strengths of this analysis include the large CT-P13 study dataset, which was analyzed to identify predictors for the probability of ADA formation, and the time of onset of ADA, and was also used to establish a link between initial IFX CL and markers of therapeutic response (e.g., MHEAL and CRP and the combined endpoint). Another strength was the rigorous and frequent follow-up of the 10 patients proactively treated using an iDose-guided approach, starting before the first IFX induction dose and continuing to follow a strict individual timeline. However, as this was a proof-of-concept compassionate use study, the number of patients enrolled was limited making this a major limitation of this study. In addition, one of the patients had normal CRP and FCP levels at first IFX administration, thus would not have been eligible for iDose-guided treatment in retrospect; however, the inflammatory biomarker data were not available at the time of first IFX treatment. Future studies should investigate outcomes of iDose-guided treatment in larger IBD patient populations together with monitoring of individual patient CL.

In summary, correlations between IFX CL were identified for MHEAL, CRP, and the combined endpoint as well as ADA and time to first ADA. In the compassionate use study. proactive use of iDose may decreased high initial IFX CL in patients with IBD, leading to improved serum IFX exposure and, consequently, improving chances of a good long-term response. The software had a good level of accuracy in predicting the best date for IFX treatment to avoid serum IFX concentrations falling below a pre-set threshold, so underdosing was avoided and the risk of ADA formation reduced. Although the compassionate use study was small, this approach may lead to improved clinical outcomes for patients with IBD receiving IFX treatment, through slowing rapid IFX CL.

The authors thank all patients, staff, and investigators involved in the CT-P13 study and compassionate use program. Editorial support, including reviewing and copyediting, was provided by Tyrrell B at Aspire Scientific (Bollington, United Kingdom), and funded by Celltrion, Inc. (Incheon, South Korea).

| 1. | Graham DB, Xavier RJ. Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2020;578:527-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 85.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, Domènech E, Pouillon L, Siegmund B, Danese S, Ghosh S. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in inflammatory bowel disease: the story continues. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211059954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P; ACCENT I Study Group. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in RCA: 3102] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE, Rachmilewitz D, Rutgeerts P, Wild G, Wolf DC, Marsters PA, Travers SB, Blank MA, van Deventer SJ. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1588] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, Colombel JF. Loss of Response to Anti-TNFs: Definition, Epidemiology, and Management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Minar P, Saeed SA, Afreen M, Kim MO, Denson LA. Practical Use of Infliximab Concentration Monitoring in Pediatric Crohn Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:715-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Katz L, Gisbert JP, Manoogian B, Lin K, Steenholdt C, Mantzaris GJ, Atreja A, Ron Y, Swaminath A, Shah S, Hart A, Lakatos PL, Ellul P, Israeli E, Svendsen MN, van der Woude CJ, Katsanos KH, Yun L, Tsianos EV, Nathan T, Abreu M, Dotan I, Lashner B, Brynskov J, Terdiman JP, Higgins PD, Chaparro M, Ben-Horin S. Doubling the infliximab dose versus halving the infusion intervals in Crohn's disease patients with loss of response. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2026-2033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, Hamilton B, Bewshea C, Walker GJ, Thomas A, Nice R, Perry MH, Bouri S, Chanchlani N, Heerasing NM, Hendy P, Lin S, Gaya DR, Cummings JRF, Selinger CP, Lees CW, Hart AL, Parkes M, Sebastian S, Mansfield JC, Irving PM, Lindsay J, Russell RK, McDonald TJ, McGovern D, Goodhand JR, Ahmad T; UK Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pharmacogenetics Study Group. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn's disease: a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:341-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 73.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wong U, Cross RK. Primary and secondary nonresponse to infliximab: mechanisms and countermeasures. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ternant D, Paintaud G. Pharmacokinetics and concentration-effect relationships of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5 Suppl 1:S37-S47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hanauer SB, Wagner CL, Bala M, Mayer L, Travers S, Diamond RH, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P. Incidence and importance of antibody responses to infliximab after maintenance or episodic treatment in Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:542-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maser EA, Villela R, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Association of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1248-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Seow CH, Newman A, Irwin SP, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Trough serum infliximab: a predictive factor of clinical outcome for infliximab treatment in acute ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2010;59:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Papamichael K, Afif W, Drobne D, Dubinsky MC, Ferrante M, Irving PM, Kamperidis N, Kobayashi T, Kotze PG, Lambert J, Noor NM, Roblin X, Roda G, Vande Casteele N, Yarur AJ, Arebi N, Danese S, Paul S, Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Cheifetz AS, Peyrin-Biroulet L; International Consortium for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: unmet needs and future perspectives. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:171-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Patel S, Yarur AJ. A Review of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Receiving Combination Therapy. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gil Candel M, Gascón Cánovas JJ, Urbieta Sanz E, Gómez Espín R, Nicolás de Prado I, Iniesta Navalón C. Usefulness of therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab during the induction period in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112:360-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Céspedes-Martínez E, Robles-Alonso V, Serra-Ruiz X, Herrera-De Guise C, Mayorga-Ayala L, García-García S, Larrosa-García M, Casellas F, Borruel N. Dashboard-Guided Anti-TNF Induction: An Effective Strategy to Minimize Immunogenicity While Avoiding Immunomodulators-A Single-Center Cohort Study. Crohns Colitis 360. 2025;7:otaf023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gibson DJ, Heetun ZS, Redmond CE, Nanda KS, Keegan D, Byrne K, Mulcahy HE, Cullen G, Doherty GA. An accelerated infliximab induction regimen reduces the need for early colectomy in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:330-335.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Colman RJ, Xiong Y, Mizuno T, Hyams JS, Noe JD, Boyle B, D'Haens GR, van Limbergen J, Chun K, Yang J, Rosen MJ, Denson LA, Vinks AA, Minar P. Antibodies-to-infliximab accelerate clearance while dose intensification reverses immunogenicity and recaptures clinical response in paediatric Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:593-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fiske J, Conley T, Sebastian S, Subramanian S. Infliximab in acute severe colitis: getting the right dose. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;11:427-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ananthakrishnan AN. Precision medicine in inflammatory bowel diseases. Intest Res. 2024;22:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhu K, Ding X, Xue L, Liu L, Wang Y, Li Y, Xi Q, Pang X, Chen W, Miao L. Optimising infliximab induction dosing to achieve clinical remission in Chinese patients with Crohn's disease. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1430120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tucker GT. Personalized Drug Dosage - Closing the Loop. Pharm Res. 2017;34:1539-1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Barrett JS. Asking More of Our EHR Systems to Improve Outcomes for Pediatric Patients. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mould DR, Upton RN, Wojciechowski J. Dashboard systems: implementing pharmacometrics from bench to bedside. AAPS J. 2014;16:925-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Strik AS, Löwenberg M, Mould DR, Berends SE, Ponsioen CI, van den Brande JMH, Jansen JM, Hoekman DR, Brandse JF, Duijvestein M, Gecse KB, de Vries A, Mathôt RA, D'Haens GR. Efficacy of dashboard driven dosing of infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease patients; a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:145-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dubinsky MC, Mendiolaza ML, Phan BL, Moran HR, Tse SS, Mould DR. Dashboard-Driven Accelerated Infliximab Induction Dosing Increases Infliximab Durability and Reduces Immunogenicity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:1375-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ye BD, Pesegova M, Alexeeva O, Osipenko M, Lahat A, Dorofeyev A, Fishman S, Levchenko O, Cheon JH, Scribano ML, Mateescu RB, Lee KM, Eun CS, Lee SJ, Lee SY, Kim H, Schreiber S, Fowler H, Cheung R, Kim YH. Efficacy and safety of biosimilar CT-P13 compared with originator infliximab in patients with active Crohn's disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2019;393:1699-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Eser A, Primas C, Reinisch S, Vogelsang H, Novacek G, Mould DR, Reinisch W. Prediction of Individual Serum Infliximab Concentrations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease by a Bayesian Dashboard System. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58:790-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Olson A, Strauss R, Davis HM. Serum albumin concentration: a predictive factor of infliximab pharmacokinetics and clinical response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:297-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Ford J, Hernandez D, Johanns J, Hu C, Davis HM, Zhou H. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:1211-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Blank M, Zhou H, Davis HM. Pharmacokinetic properties of infliximab in children and adults with Crohn's disease: a retrospective analysis of data from 2 phase III clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2011;33:946-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sheiner LB, Beal SL. Evaluation of methods for estimating population pharmacokinetic parameters. II. Biexponential model and experimental pharmacokinetic data. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1981;9:635-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Papamichael K, Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Gils A, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring During Induction of Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Defining a Therapeutic Drug Window. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1510-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Vande Casteele N, Jeyarajah J, Jairath V, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Infliximab Exposure-Response Relationship and Thresholds Associated With Endoscopic Healing in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1814-1821.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang SL, Ohrmund L, Hauenstein S, Salbato J, Reddy R, Monk P, Lockton S, Ling N, Singh S. Development and validation of a homogeneous mobility shift assay for the measurement of infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab levels in patient serum. J Immunol Methods. 2012;382:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bauman LE, Xiong Y, Mizuno T, Minar P, Fukuda T, Dong M, Rosen MJ, Vinks AA. Improved Population Pharmacokinetic Model for Predicting Optimized Infliximab Exposure in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:429-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shiga H, Abe I, Onodera M, Moroi R, Kuroha M, Kanazawa Y, Kakuta Y, Endo K, Kinouchi Y, Masamune A. Serum C-reactive protein and albumin are useful biomarkers for tight control management of Crohn's disease in Japan. Sci Rep. 2020;10:511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Schräpel C, Kovar L, Selzer D, Hofmann U, Tran F, Reinisch W, Schwab M, Lehr T. External Model Performance Evaluation of Twelve Infliximab Population Pharmacokinetic Models in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bevers NC, Keizer RJ, Wong DR, Aliu A, Pierik MJ, Derijks LJJ, van Rheenen PF. Performance of Eight Infliximab Population Pharmacokinetic Models in a Cohort of Dutch Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2024;63:529-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hemperly A, Vande Casteele N. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Infliximab in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Eser A, Reinisch W, Schreiber S, Ahmad T, Boulos S, Mould DR. Increased Induction Infliximab Clearance Predicts Early Antidrug Antibody Detection. J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;61:224-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Deyhim T, Cheifetz AS, Papamichael K. Drug Clearance in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Biologics. J Clin Med. 2023;12:7132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Brandse JF, Mould D, Smeekes O, Ashruf Y, Kuin S, Strik A, van den Brink GR, DʼHaens GR. A Real-life Population Pharmacokinetic Study Reveals Factors Associated with Clearance and Immunogenicity of Infliximab in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:650-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Dreesen E, Berends S, Laharie D, D'Haens G, Vermeire S, Gils A, Mathôt R. Modelling of the relationship between infliximab exposure, faecal calprotectin and endoscopic remission in patients with Crohn's disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87:106-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Irving PM, Gecse KB. Optimizing Therapies Using Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Current Strategies and Future Perspectives. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1512-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Scaldaferri F, D'Ambrosio D, Holleran G, Poscia A, Petito V, Lopetuso L, Graziani C, Laterza L, Pistone MT, Pecere S, Currò D, Gaetani E, Armuzzi A, Papa A, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini A. Body mass index influences infliximab post-infusion levels and correlates with prospective loss of response to the drug in a cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients under maintenance therapy with Infliximab. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Passot C, Mulleman D, Bejan-Angoulvant T, Aubourg A, Willot S, Lecomte T, Picon L, Goupille P, Paintaud G, Ternant D. The underlying inflammatory chronic disease influences infliximab pharmacokinetics. MAbs. 2016;8:1407-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Stockmann C, Barrett JS, Roberts JK, Sherwin C. Use of Modeling and Simulation in the Design and Conduct of Pediatric Clinical Trials and the Optimization of Individualized Dosing Regimens. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2015;4:630-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Papamichael K, Jairath V, Zou G, Cohen B, Ritter T, Sands B, Siegel C, Valentine J, Smith M, Vande Casteele N, Dubinsky M, Cheifetz A. Proactive infliximab optimisation using a pharmacokinetic dashboard versus standard of care in patients with Crohn's disease: study protocol for a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label study (the OPTIMIZE trial). BMJ Open. 2022;12:e057656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/