Published online Feb 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.113024

Revised: October 15, 2025

Accepted: December 8, 2025

Published online: February 7, 2026

Processing time: 164 Days and 20.1 Hours

The Danggui-Baishao herb pair is the foundation of a traditional Chinese medi

To uncover the mechanisms underlying the anti-colitis effects of the Danggui-Bai

The chemical composition of the herb pair was characterized by high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole/time of flight mass spectrometry analysis. A mouse model of colitis was induced by administering 2.5% dextran sulfate sodi

The herb pair improved body weight, colon length, intestinal inflammation, and barrier function. Additionally, the herb pair upregulated the expression of inte

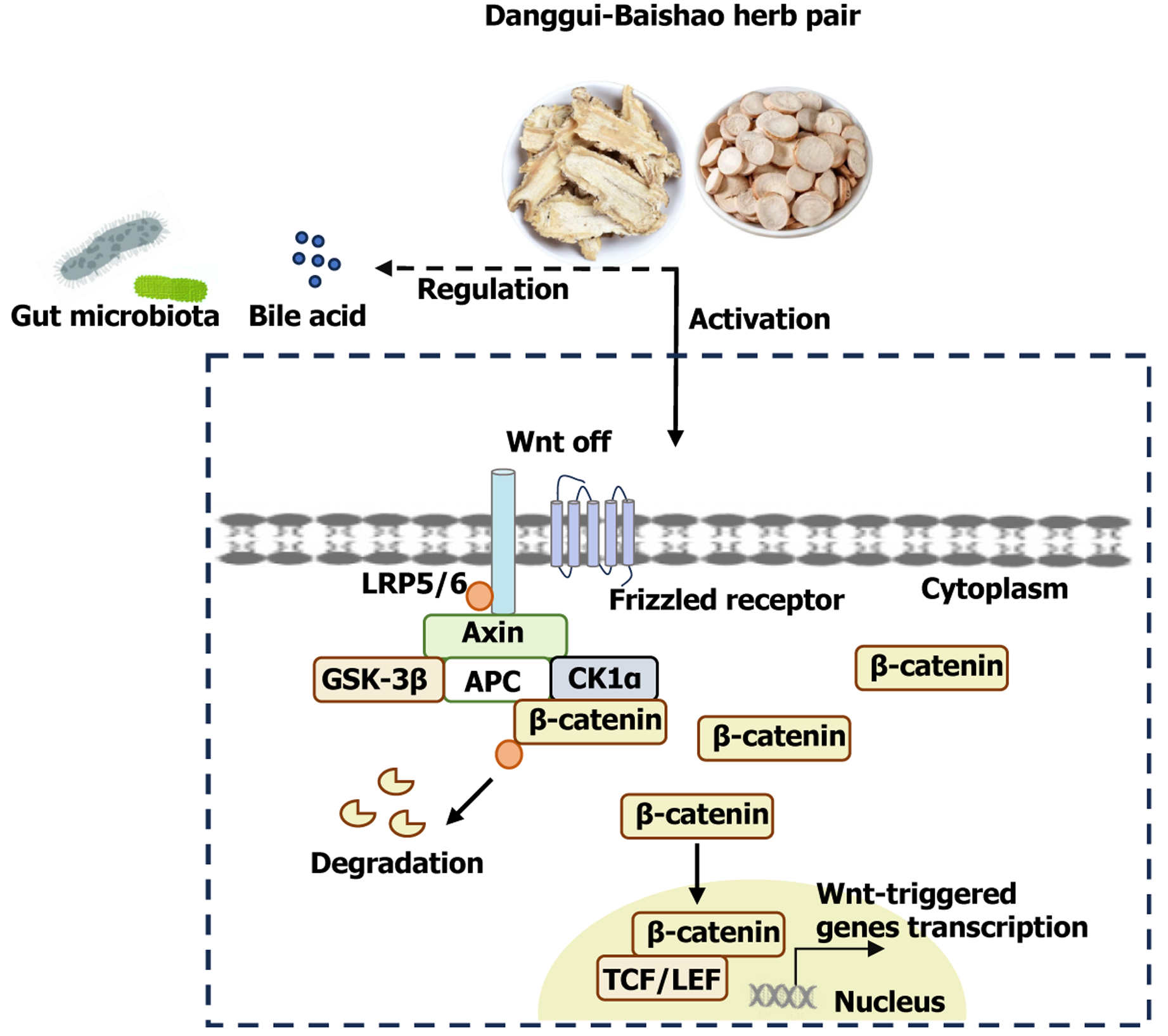

The herb pair effectively reduces colonic inflammation and maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Moreover, the anti-colitis efficacy of the herb pair is closely associated with activation of the Wnt/β-catenin path

Core Tip: The Danggui-Baishao herb pair has shown definite anti-colitis effects in traditional Chinese medicine. By detecting the active ingredients of the herb pair and using transcriptome sequencing for mechanism prediction, our results show that the herb pair protects against colitis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in vivo, yet this effect is diminished by the β-catenin antagonist ICG-001. Through metabolomics, 16S rRNA, and metagenomic further revealed that the herb pair regulates bile acids metabolism and gut microbiota composition. Finally, molecular docking revealed that benzoylpaeoniflorin has a structural basis for binding to β-catenin. Benzoylpaeoniflorin can activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in vitro and diminished by the ICG-001. This study provides experimental evidence for research on anti-colitis drugs.

- Citation: Xu T, Hou WX, Yang ST, Shao YP, Wang J, Han TT, Li JN. Danggui-Baishao herb pair protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(5): 113024

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i5/113024.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.113024

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the primary clinical subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and is characterized by intestinal damage, loss of intestinal barrier integrity, and an expanded inflammatory response[1]. Approximately 5 million people worldwide are affected by UC, and the incidence rate is on the rise[2]. This has thus imposed a significant burden on healthcare systems. The etiopathogenesis of UC remains complex and enigmatic, involving a multifaceted interplay of factors that disrupt intestinal barrier function, impair immune regulation, cause dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, and induce genetic alterations. Despite the existence of multiple therapeutic approaches that have yet to achieve clinical efficacy, the majority of currently available treatments for IBD primarily focus on suppressing inflammation. Patients may experience residual symptoms during disease remission due to defective wound healing processes[3], and the use of immunosuppressants can also increase the risk of infection and various cancers. Consequently, in-depth research on the pathogenesis of UC and the pursuit of new intervention drugs are of vital importance.

The intestinal barrier, recognized as the body’s internal defense, can effectively prevent the entry of detrimental substances and pathogens. It is widely recognized that persistent injury to the intestinal barrier is the main pathological mechanism underlying the early onset of IBD[4]. The intestinal epithelial cells constitute the fundamental component of mucosal barrier function. It has been reported that all the cell types derived from intestinal stem cells (ISCs) reside at the crypt base and are shielded from the influence of soluble metabolites in the intestinal lumen, including intestinal microbiota-derived metabolites that have an inhibitory effect on the proliferation potential of stem cells[5]. Studies have shown that in a colitis model, the leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) gene in ISCs is almost completely depleted by the third day[6]. Moreover, scientists have focused on mucosal barrier healing as a therapeutic approach to treating UC, with the modulation of induced ISCs emerging as the most promising strategy[7].

The precise mechanisms governing the regulation of ISCs expression or stability remain a subject of ongoing research and debate. It is well-established that microbiota-related mucosal barrier injury plays a pivotal role in colitis and that the subsequent mucosal barrier injury facilitates the dysregulation of microbiota-induced inflammatory cascades[8,9]. A recent study demonstrated that microbiota-derived tyramine from Enterococcus suppresses the proliferation of ISCs, thereby impairing epithelial regeneration and exacerbating dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis through the activation of adrenergic receptor alpha 2[10]. Lactobacillus-derived lactate activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling through Gi-protein-coupled receptor 81, thereby promoting the proliferation of ISCs epithelium[11]. Researchers also identified that the subsequent activation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) by microbiota-derived deoxycholic acid triggered Wnt signal-dependent ISCs maintenance[12]. Wnt/β-catenin is a well-documented regulator of ISCs proliferation and fate control. Disorders in Wnt signaling can reduce the number of intestinal secretory cells, further impairing the mucus barrier and ultimately resulting in integrity damage[13]. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) degrades β-catenin through pho

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has a long history of treating UC and plays a crucial role in its management. Herb pair (referred to as “yao dui” or “dui yao” in TCM) represent the simplest and fundamental form of multiple herbal preparations. Compared with individual plants, they exhibit significantly enhanced pharmacological efficacy, a broader therapeutic range, and reduced toxicity. Danggui and Baishao are derived from the dried root of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels and Paeonia lactiflora Pall, respectively. The Danggui-Baishao herb pair (hereafter referred to as “herb pair”) is the central component of the classic anti-colitis formula, Shaoyao decoction, and is extensively used in clinical practice for colitis treatment[15] and was recently confirmed to restore the mucus layer in colitis mice[16]. Yin and blood deficiency are important pathological mechanisms of UC, and the herb pair has the function of regulating yin and blood[17]. In the Song dynasty, Dou Cai initially used the herb pair for treating diarrhea accompanied by blood or pus and abdominal pain, which are the primary symptoms of UC. Experimental research has also demonstrated that Angelica sinensis polysaccharide exhibits substantial efficacy in improving body weight loss, colon shortening, and the disease activity index score[18]. Paeonia lactiflora Pall. extract showed positive effects on colon length and cytokine levels in a colitis model[19]. Given the favorable outcome of the herb pair, its underlying mechanism requires further investigation.

In the present study, we initially explored the restorative effects of the Danggui-Baishao herb pair on intestinal mucosal barrier integrity and ISCs proliferation. Then, we investigated its potential in influencing the microbiota, bile acids (BAs) metabolism, and the colonic Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Furthermore, we elucidated the potential mechanism of action of the herbs in the treatment of colitis with the aid of the β-catenin inhibitor ICG-001. Finally, molecular docking and in vitro model were conducted to explore the protective mechanisms of benzoylpaeoniflorin.

According to the ancient Chinese book Bianquexinshu by Dou Cai during the Song dynasty, the herb pair is composed of Danggu and Baishao (1:1, w/w), and the granules used in this study were acquired from Tianjiang Pharmaceuticals (Jiangsu, China). A Shimadzu LCMS-9050 system was employed for high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole/time of flight mass spectrometry analysis to characterize the chemical composition of the herb pair. Chromatographic separation was carried out at 35 °C with the mobile phase composed of water (A) and acetonitrile (B) using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 chromatographic column. The injection volume was set at 1 μL and the flow rate at 0.3 mL/minute, following the gradient elution procedure below: 0-5 minutes, 10% B; 5-30 minutes, 15% B; 30-50 minutes, 30% B; 50-65 minutes, 50% B; 65-80 minutes, 70% B; 80-90 minutes, 90% B; 90-95 minutes, 95% B; 95-100 minutes, 10% B. The quadrupole/time of flight mass spectrometry detection was carried out using the positive/negative ion switch mode, and the m/z scanning range was set at 100-1200. Key instrumental parameters included: The desolvation pipeline temperature at 250 °C, the interface temperature at 300 °C, the hot block temperature at 400 °C, the atomizer gas flow rate at 1 L/minute, and the drying gas flow rate at 10 L/minute. Real-time mass axis calibration was carried out using a 400 mg/L sodium iodide solution. Finally, data collection and analysis were carried out using Labsolution software (Shi

All specific pathogen-free male C57BL/6J mice (six-to-eight-week-old) were purchased from Sipeifu Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. All mice were kept in specific pathogen-free facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, humidity at 50% ± 15%, and free access to clean water and food. The Animal Care Ethics and Use Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, No. XHDW-2024-37-1 approved the experimental design and procedures in this study.

After one week of adaptive feeding, 54 mice were randomly divided into the following six groups: Control, control + herb pair-high, DSS, herb pair-low, herb pair-high, and mesalazine (A79809, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States). Both the control and the control + herb pair-high groups were given clear water. The other four groups of mice received 2.5% DSS (36000-50000 MW, CAS: 216011080, MP Biomedicals, CA, United States) in their drinking water for five days, then switched to clean drinking water for two days in order to induce the acute colitis model. Mice in the herb pair groups and the mesalazine group were administered 5.2 g crude drug/kg or 10.4 g crude drug/kg and mesalazine 50 mg/kg by oral gavage daily for seven days, respectively. The same volume of normal saline was administered to mice in the control group and the DSS group by gavage.

In the inhibitor experiment, we randomly divided 24 mice into four groups: DSS, DSS + herb pair, DSS + ICG-001 (HY-14428, MCE, NJ, Unites States), and DSS + ICG-001 + herb pair. Mice in the DSS + herb pair and DSS + ICG-001 + herb pair groups received the herb pair (10.4 g crude drug/kg) by oral gavage daily for seven consecutive days. Mice in the DSS + ICG-001 and DSS + ICG-001 + herb pair groups were administered ICG-001 (20 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection every other day. The same volume of control saline was administered to mice in the DSS and DSS + herb pair groups by intraperitoneal injection.

HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium (11875093, Gibco, NY, United States) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10099141C, Gibco, NY, United States). The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. To establish an in vitro model, the cells were treated with 2% DSS. Benzoylpaeoniflorin (HY-N0852, MCE, NJ, Unites States) was applied at three different concentrations: Low (Ben-L, 25 μM), medium (Ben-M, 50 μM), and high (Ben-H, 100 μM), and co-treated with 2% DSS for 24 hours. In inhibitor experiments, ICG-001 (38 μM) is an inhibitor of β-catenin/T-cell factor-mediated transcription.

Colon tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Alcian blue (AB), and AB-periodic acid Schiff (PAS) according to standard protocols, respectively.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (CSBE13066m) kit obtained from Wuhan Huamei Biological Engineering Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) was used to detect the content of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in serum samples following the manufa

The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran method was used to evaluate intestinal permeability. In brief, food and water were withheld for 8 hours before the mice were sacrificed. Subsequently, FITC-dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States, 4 kDa, 600 mg/kg) was intragastrically administered. Blood was collected under isoflurane anesthesia after 4 hours, and the supernatant was centrifuged (avoiding light).

The colon tissue sections underwent antigen repair and were blocked with 5% goat serum. They were incubated with anti-CD11b (1:500, ab133357, ABCAM, United Kingdom), anti-F4/80 (1:500, ab111101, ABCAM, United Kingdom), anti-Lgr5 (1:500, ab75850, ABCAM, United Kingdom), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (1:500, 60097-1-Ig, Proteintech, IL, United States), anti-Ki67 (1:100, MA514520, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States), and anti-β-catenin (1:500, ab32572, ABCAM, United Kingdom) overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, secondary antibodies were applied, and the sections were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Finally, the sections were dehydrated, rendered transparent, and sealed with neutral resin.

The HiPure Total RNA Plus Kit (R4111, Magen, Beijing, China) was used to extract total RNA from colon tissues and the RevertAid First Standard cDNA Synthesis Kit (K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States) was subsequently used to complete reverse transcription. Finally, the ABI 7500 system (Life Technologies, CA, United States) was used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection. The quantitative analysis of all genes was compared to β-actin. Primer se

The protein expression of Occludin (1:1000, ab216327, ABCAM, United Kingdom), Claudin1 (1:1000, ab15098, ABCAM, United Kingdom), Claudin2 (1:1000, 26912-1-AP, Proteintech, IL, United States), E-cadherin (1:1000, 3195S, CST, MA, Unites States), β-catenin (1:1000, ab32572, ABCAM, United Kingdom), p-GSK-3β (1:1000, 5558S, CST, MA, Unites States), GSK-3β (1:1000, 12456S, CST, MA, Unites States), Cyclin D1 (1:1000, ab134175, ABCAM, United Kingdom), Lgr5 (1:1000, ab75850, ABCAM, United Kingdom), FXR (1:1000, 417200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States), β-tubulin (1:5000, ab179513, ABCAM, United Kingdom), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:5000, 10494-1-AP, Proteintech, IL, United States) in colon tissues was detected by western blot analysis. The total protein in colon tissues was extracted and homogenized, and protein concentrations were then determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (KGP902, KeyGEN, Nanjing, China). Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PG112, Epizyme, Shanghai, China) was used to separate an equal amount of sample protein and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, MA, United States). 5% skim milk (P1622, APPLYGEN, Beijing, China) was used to block the membranes for 90 minutes, and the indicated primary antibody was used to incubate the membranes for 60 minutes. Subsequently, all membranes underwent five washings with Tris-buffered saline with Tween (PS103, Epizyme, Shanghai, China), and then incubated with secondary antibody for 90 minutes. Binding signals were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system.

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) was used to extract total RNA from colon tissues. RNA sequencing analysis was performed on an Illumina HiSeq platform. The analysis was conducted using the R package edgeR, and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with an adjusted P value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Colon contents were resuspended, and then the sample was diluted with water. The diluted sample (100 μL) was mixed with 300 μL of acetonitrile/methanol (8:2) and placed on ice for 30 minutes. The supernatant was subsequently removed by centrifugation, and testing was carried out. The Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column was used to complete the separation which was maintained at 50 °C. 0.1% formic acid and 5 mmol/L ammonium consisted of the mobile phase and then acetate in water (A) and acetonitrile (B), the transport flow rate was set at 0.35 mL/minute. The solvent gradient was set as follows: 0.5 minute, 5% B; 1.5 minutes, 5%-30% B; 4 minutes, 30%-37% B; 5 minutes, 37%-38% B; 5.5 minutes, 38%-39% B; 6 minutes, 39%-42% B; 6.5 minutes, 42%-43% B; 9.5 minutes, 43%-50% B; 11 minutes, 50%-60% B; 12 minutes, 60%-95% B; 13.1 minutes, 95%-5% B; 15 minutes, 5% B. The mass spectrometer operating parameters were as follows: Curtain gas (30 psi), ion spray voltage (-4500 V), ion source temperature (550 °C), ion source gases 1 and 2 (60 psi).

Fresh colon contents were extracted for DNA using standard protocols. Subsequently, the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene was amplified and sequenced in accordance with the Illumina 16S metagenomic sequencing library protocol. Data analysis was performed utilizing the online platform (https://magic-plus.novogene.com).

DNA was extracted from colon contents using standard protocols. The DNA library preparation and metagenomic sequencing of all samples were performed using Illumina NovaSe™ X Plus. In brief, quality control and host filtering of the raw data were carried out to obtain clean data. Subsequently, the assembly was processed to generate scaffolds, followed by gene prediction and the removal of redundant gene catalogs. The samples were annotated with species, function, and resistance gene annotations. Finally, diversity analysis of species and function was conducted.

First, the three-dimensional crystal structure of the β-catenin protein (Protein Data Bank: 1JDH) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. Subsequently, the structure of benzoylpaeoniflorin was obtained from the Pubchem database, and then converted into a pdbqt file via Open Babel software. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina. Finally, the docking results were visualized and analyzed using PyMOL software.

The clinical safety of the herb pair was assessed by a maximum dose test. The survival rate and body weight of 20 mice were monitored. The anatomical structures of all mice were then examined, and any alterations in their major organs were observed. Peripheral blood was collected to evaluate liver and kidney function.

GraphPad Prism software, version 10.0 (San Diego, CA, United States) was used to analyze all experimental data. Following normality and homogeneity of variance analyses, the mean ± SD was expressed as quantitative data. When the data were normally distributed, the Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for three or more groups, and the Dunnett post-test was employed for statistical analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Based on the high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole/time of flight mass spectrometry results, eight compounds were identified: Catechin, mudanpioside E, albiflorin, paeoniflorin, ferulic acid, galloylpaeoniflorin, benz

The protective effects of the herb pair on the intestinal barrier were subsequently assessed. Western blot analysis showed that DSS treatment decreased the expression levels of tight junction proteins such as Occludin and Claudin1, adherens junction protein E-cadherin, and increased the expression level of Claudin2. Conversely, the herb pair prevented all of these changes (Figure 3A-E), indicating the protective effect of the herb pair on the intestinal barrier. Subsequently, the FITC-dextran fluorescence assay and serum LPS concentration were conducted to determine any increases in intestinal permeability. Our results indicated that the FITC-dextran-positive signal and expression level of LPS were elevated in the DSS group, but reduced by treatment with the herb pair (Figure 3F and G). Furthermore, AB staining and AB-PAS staining demonstrated that mucus production decreased and goblet cells shrank in the DSS group, while treatment with the herb pair improved these manifestations (Figure 3H-J).

An investigation into the effects of the herb pair on ISCs and proliferation-related markers found that the herb pair increased the expression of the ISCs marker Lgr5 (Figure 4A and B). Subsequent qPCR experiments indicated that colitis decreases the mRNA relative expression of stem cell and proliferation-related genes, including Lgr5, SRY-box transcription factor 9 (Sox9), homeodomain-only protein homeobox, achaete scute-like 2 (Ascl2), and telomerase reverse transcriptase (Tert). Administration of the herb pair significantly restored the expression levels of these genes (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we analyzed the relative expression of ISCs differentiation-related genes in colon tissues, and the herb pair increased the levels of genes associated with secretory cells, including Mucin 2, lysozyme 1, and Chromogranin A (Figure 4C). Additionally, IHC analysis showed that Lgr5, PCNA and Ki67 were increased in the herb pair group compared with the DSS group (Figure 4D-G). These results suggest that the herb pair stimulated the proliferation of ISCs, thereby promoting intestinal repair following DSS exposure.

Through RNA sequencing, we elucidated the underlying mechanisms of the herb pair in combating colitis. An overlap analysis identified 830 overlapping DEGs between the two sets of DEGs, and their expression patterns were visualized in a heatmap (Figure 5A and B). Gene set enrichment analysis and the heatmap revealed that the herb pair activated the Wnt signal (Figure 5C and D). Subsequently, we examined the mRNA expression of Wnt signal-related genes. We found that DSS reduced the relative expression of Wnt5b, Wnt9a, and Wnt10a, while the herb pair upregulated the expression of porcupine, Wnt5b, Wnt9a, and Wnt10a (Figure 5E). Furthermore, the relative expression of Wnt4 and Wnt6 showed no statistical difference, but the herb pair exhibited a tendency to increase their expression (Figure 5E). Western blot analysis of colon tissues demonstrated that the herb pair activated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which was manifested as the upregulation of β-catenin, p-GSK-3β, and Cyclin D1 (Figure 5F-I). Furthermore, IHC analysis showed that β-catenin was elevated following administration of the herb pair (Figure 5J and K). In summary, these data initially confirm that the herb pair activated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby promoting repair of the intestinal barrier.

The gene set enrichment analysis based on colonic RNA-seq revealed that the herb pair activated the FXR pathway (Figure 6A). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the herb pair increased the expression of FXR (Figure 6B and C). The qPCR indicated that the relative expression of nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 4, fibroblast growth factor 15, and nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 2 were increased in the herb pair group (Figure 6D). To elucidate the metabolomic phenotypes, we employed targeted metabolomics to determine the BAs in colon contents. Compared to the DSS group, the herb pair did not significantly alter primary BAs. However, there were notable changes in secondary BAs, including tauroursodeoxycholic acid and 7-ketolithocholic acid (7-keto-LCA) (Figure 6E and F). To ascertain whether the therapeutic effects of the herb pair involved regulating the microbiota, 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomic sequencing were used to analyze the microbiota. To further understand the composition of the gut mic

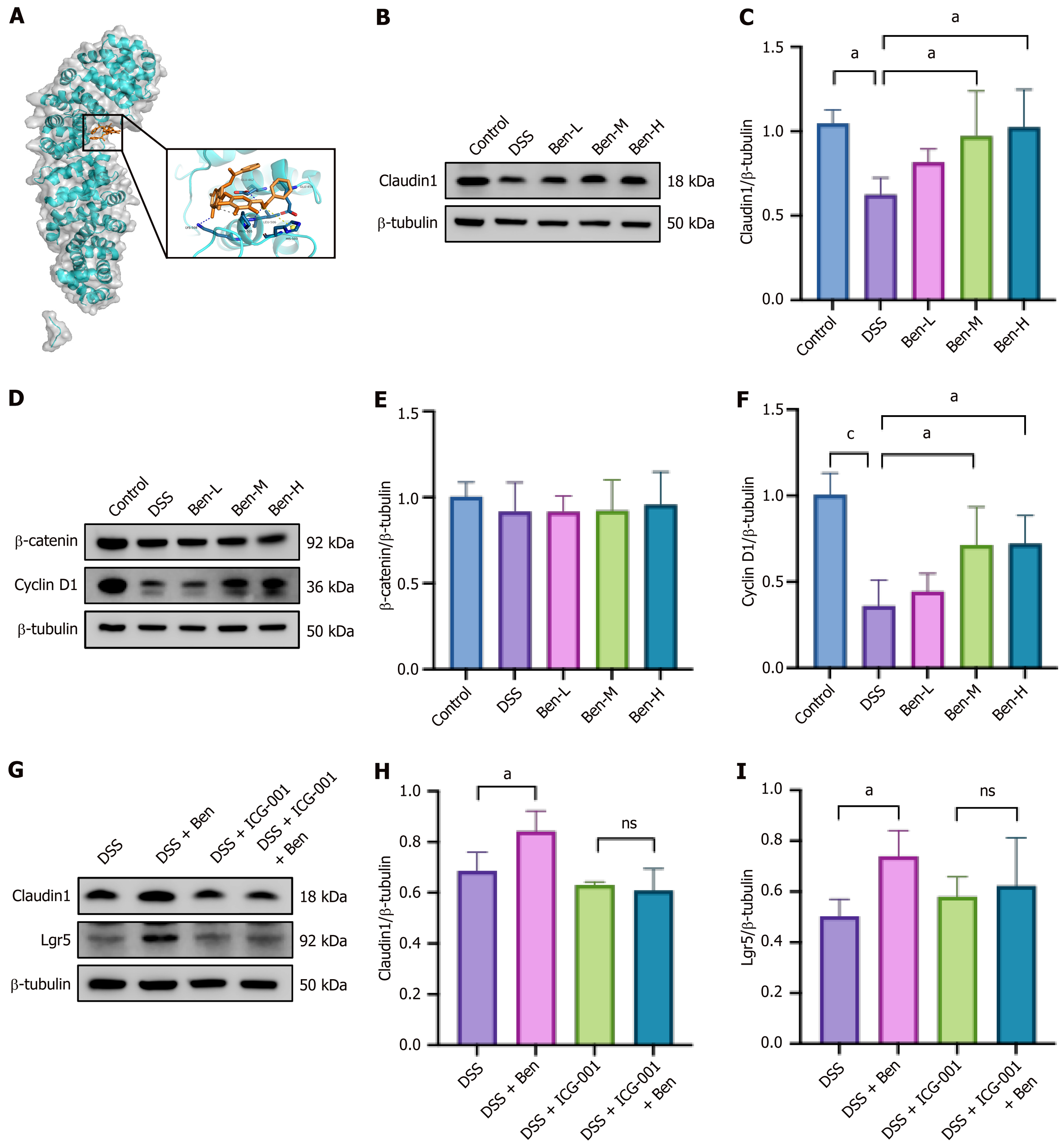

To understand the potential biological mechanism of the herb pair in alleviating intestinal epithelial barrier damage, the

We performed molecular docking to evaluate the potential binding of the main compounds to the β-catenin protein. A potential binding pocket was obtained from a previous study which identified notoginsenoside r1 as an agonist of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and which bound to β-catenin protein with relatively low binding energies of -7.29 kcal/mol[21]. The present study showed that benzoylpaeoniflorin, galloylpaeoniflorin, benzoylalbiflorin, mudanpioside E, paeoniflorin, catechin, albiflorin, and ferulic acid can bind to the β-catenin protein with relatively low binding energies of -8, -8, -7.8,

UC is a chronic non-specific intestinal inflammatory disease with diarrhea accompanied by blood or pus, abdominal pain and tenesmus as the main clinical manifestations. However, improvement of clinical symptoms does not alter disease progression. Approximately 39% to 60% of patients with a clinical response still exhibit endoscopic active status, underscoring the progressive importance of mucosal barrier healing as the primary therapeutic objective[22]. Given that ISCs can differentiate into multiple cell types, the management of dysfunctional ISCs to promote mucosal barrier healing represents an effective alternative therapy. The herb pair has been extensively utilized in TCM for over a millennium to alleviate symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal discomfort. The majority of medical practitioners believe that this herb pair facilitates the regeneration of injured intestinal tissue and restores its functionality. We established a colitis model to investigate the efficacy of the herb pair treatment in reversing weight loss, colon shortening, alleviating histopathological damage, and reducing the inflammation in colon tissues. It was observed that the herb pair significantly enhanced the intestinal barrier, as assessed by a fluorescence assay using FITC-dextran and by measuring the expression of serum LPS and colonic junction proteins. The AB staining and AB-PAS staining showed that the herb pair enhanced the goblet cell count. Goblet cells are highly expressed and have normal secretory function in physiological conditions. They are mainly responsible for producing and secreting glycoproteins, which are the main components of the mucous layer, anti-microbial peptides are enriched in the mucosal layer[5]. Both clinical data and experimental evidence have shown a correlation between elevated intestinal tight junction permeability and adverse outcomes in active UC[23], and has been shown to generate vital therapeutic effects in relieving intestinal inflammation by reducing intestinal per

Our study verified that the herb pair elevated the expression of Lgr5, which serves as a crucial marker gene for ISCs. Additionally, we assessed other ISCs markers, including Sox9, homeodomain-only protein homeobox, Ascl2, Tert, Chromogranin A, and lysozyme 1. The herb pair exhibited a consistent upregulation of these genes, suggesting an elevated expression of ISCs. This finding was corroborated by IHC for Lgr5, PCNA, and Ki67. The Wnt pathway is a signal transduction route that is activated by the binding of Wnt proteins to membrane protein receptors, triggering a cascade reaction from upstream to downstream and regulating various biological behaviors. During embryogenesis and adult tissue homeostasis, it is crucial for the proliferation, differentiation and renewal of stem cells[25]. The Wnt signal target genes act as intercellular signals and regulate a diverse range of cellular processes, such as stem cell maintenance and proliferation[26]. Through RNA-seq and qPCR analyses, we identified Wnt5b, Wnt9a, and Wnt10a as upregulated genes in response to the herb pair treatment. Five publicly available IBD datasets were integrated to identify a molecular subtype associated with the WNT5B+ cell type[27]. It has been well documented that the self-renewal activities of mesenchymal stem-like cells were stimulated by recombinant Wnt5a[28]. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 knockdown results in a decrease in Wnt10a and nuclear β-catenin protein levels, as well as the downregulated of Lgr5 and c-Myc mRNA expression, furthermore, this treatment delayed wound healing after 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid administration[29]. Our data revealed that the herb pair treatment substantially elevated cellular levels of total β-catenin and concurrently increased the p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β ratio. This suggests a significant reduction in the non-phosphorylated form of GSK-3β, which plays an important role in the phosphorylation of β-catenin and its subsequent degradation. To elucidate the precise role of Wnt/β-catenin activation in the herb pair treatment, we administered ICG-001 by intraperitoneal injection[21]. The results showed that ICG-001 diminished the protective effects of the herb pair in terms of junction protein expression and ISCs marker gene levels. These findings indicated a Wnt signal-dependent mechanism through which the herb pair alleviated colon shortening and facilitated intestinal mucosal healing. Our findings also echo previous research, where berberine and notoginsenoside R1 were also highlighted as novel and effective strategies in anti-colitis by restoring mucosal barrier and regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway[21,30].

The close connection between IBD and intestinal ecological imbalance has received extensive attention from res

Our study confirmed that the herb pair treatment can effectively modulate the structure of the gut microbiota, promote the proliferation and activity of ISCs and activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. A key question is whether the gut mic

The herb pair effectively alleviated experimental colitis through the following mechanisms: Modulating the microbiota, facilitating the restoration of Lgr5+ ISCs, and safeguarding epithelial integrity. Furthermore, the beneficial impact of the herb pair on colitis was, at least in part, facilitated by activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Figure 10).

| 1. | Gros B, Kaplan GG. Ulcerative Colitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:951-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Le Berre C, Honap S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2023;402:571-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 931] [Reference Citation Analysis (104)] |

| 3. | Otte ML, Lama Tamang R, Papapanagiotou J, Ahmad R, Dhawan P, Singh AB. Mucosal healing and inflammatory bowel disease: Therapeutic implications and new targets. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1157-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | An J, Liu Y, Wang Y, Fan R, Hu X, Zhang F, Yang J, Chen J. The Role of Intestinal Mucosal Barrier in Autoimmune Disease: A Potential Target. Front Immunol. 2022;13:871713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Villablanca EJ, Selin K, Hedin CRH. Mechanisms of mucosal healing: treating inflammatory bowel disease without immunosuppression? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:493-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Harnack C, Berger H, Antanaviciute A, Vidal R, Sauer S, Simmons A, Meyer TF, Sigal M. R-spondin 3 promotes stem cell recovery and epithelial regeneration in the colon. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Majumder S, Santacroce G, Maeda Y, Zammarchi I, Puga-Tejada M, Ditonno I, Hayes B, Crotty R, Fennell E, Shivaji UN, Abdawn Z, Hejmadi R, Parigi TL, Nardone OM, Murray P, Burke L, Ghosh S, Iacucci M. Endocytoscopy with automated multispectral intestinal barrier pathology imaging for assessment of deep healing to predict outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2024;73:1603-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lo BC, Kryczek I, Yu J, Vatan L, Caruso R, Matsumoto M, Sato Y, Shaw MH, Inohara N, Xie Y, Lei YL, Zou W, Núñez G. Microbiota-dependent activation of CD4(+) T cells induces CTLA-4 blockade-associated colitis via Fcγ receptors. Science. 2024;383:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Federici S, Kredo-Russo S, Valdés-Mas R, Kviatcovsky D, Weinstock E, Matiuhin Y, Silberberg Y, Atarashi K, Furuichi M, Oka A, Liu B, Fibelman M, Weiner IN, Khabra E, Cullin N, Ben-Yishai N, Inbar D, Ben-David H, Nicenboim J, Kowalsman N, Lieb W, Kario E, Cohen T, Geffen YF, Zelcbuch L, Cohen A, Rappo U, Gahali-Sass I, Golembo M, Lev V, Dori-Bachash M, Shapiro H, Moresi C, Cuevas-Sierra A, Mohapatra G, Kern L, Zheng D, Nobs SP, Suez J, Stettner N, Harmelin A, Zak N, Puttagunta S, Bassan M, Honda K, Sokol H, Bang C, Franke A, Schramm C, Maharshak N, Sartor RB, Sorek R, Elinav E. Targeted suppression of human IBD-associated gut microbiota commensals by phage consortia for treatment of intestinal inflammation. Cell. 2022;185:2879-2898.e24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 92.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li C, Zhang P, Xie Y, Wang S, Guo M, Wei X, Zhang K, Cao D, Zhou R, Wang S, Song X, Zhu S, Pan W. Enterococcus-derived tyramine hijacks α(2A)-adrenergic receptor in intestinal stem cells to exacerbate colitis. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32:950-963.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu H, Mu C, Li X, Fan W, Shen L, Zhu W. Breed-Driven Microbiome Heterogeneity Regulates Intestinal Stem Cell Proliferation via Lactobacillus-Lactate-GPR81 Signaling. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2400058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim TY, Kim S, Kim Y, Lee YS, Lee S, Lee SH, Kweon MN. A High-Fat Diet Activates the BAs-FXR Axis and Triggers Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Properties in the Colon. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13:1141-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lin YJ, Li HM, Gao YR, Wu PF, Cheng B, Yu CL, Sheng YX, Xu HM. Environmentally relevant concentrations of benzophenones exposure disrupt intestinal homeostasis, impair the intestinal barrier, and induce inflammation in mice. Environ Pollut. 2024;350:123948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu H, Mu C, Xu L, Yu K, Shen L, Zhu W. Host-microbiota interaction in intestinal stem cell homeostasis. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2353399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang S, Cai L, Ma Y, Zhang H. Shaoyao decoction alleviates DSS-induced colitis by inhibiting IL-17a-mediated polarization of M1 macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;337:118941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fang YX, Liu YQ, Hu YM, Yang YY, Zhang DJ, Jiang CH, Wang JH, Zhang J. Shaoyao decoction restores the mucus layer in mice with DSS-induced colitis by regulating Notch signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;308:116258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang Z, Wu G, Yang J, Liu X, Chen Z, Liu D, Huang Y, Yang F, Luo W. Integrated network pharmacology, transcriptomics and metabolomics to explore the material basis and mechanism of Danggui-Baishao herb pair for treating hepatic fibrosis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;337:118834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cheng F, Zhang Y, Li Q, Zeng F, Wang K. Inhibition of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Experimental Colitis in Mice by Angelica Sinensis Polysaccharide. J Med Food. 2020;23:584-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yan BF, Chen X, Chen YF, Liu SJ, Xu CX, Chen L, Wang WB, Wen TT, Zheng X, Liu J. Aqueous extract of Paeoniae Radix Alba (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice by tunning the intestinal physical barrier, immune responses, and microbiota. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;294:115365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ma Y, Lang X, Yang Q, Han Y, Kang X, Long R, Du J, Zhao M, Liu L, Li P, Liu J. Paeoniflorin promotes intestinal stem cell-mediated epithelial regeneration and repair via PI3K-AKT-mTOR signalling in ulcerative colitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;119:110247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yu ZL, Gao RY, Lv C, Geng XL, Ren YJ, Zhang J, Ren JY, Wang H, Ai FB, Wang ZY, Zhang BB, Liu DH, Yue B, Wang ZT, Dou W. Notoginsenoside R1 promotes Lgr5(+) stem cell and epithelium renovation in colitis mice via activating Wnt/β-Catenin signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024;45:1451-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kotla NG, Rochev Y. IBD disease-modifying therapies: insights from emerging therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29:241-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Horowitz A, Chanez-Paredes SD, Haest X, Turner JR. Paracellular permeability and tight junction regulation in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:417-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li J, Niu C, Ai H, Li X, Zhang L, Lang Y, Wang S, Gao F, Mei X, Yu C, Sun L, Huang Y, Zheng L, Wang G, Sun Y, Yang X, Song Z, Bao Y. TSP50 Attenuates DSS-Induced Colitis by Regulating TGF-β Signaling Mediated Maintenance of Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Integrity. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2305893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Shu G, Yin G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 1605] [Article Influence: 401.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Merenda A, Fenderico N, Maurice MM. Wnt Signaling in 3D: Recent Advances in the Applications of Intestinal Organoids. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30:60-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang J, Guay H, Chang D. Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis Share 2 Molecular Subtypes With Different Mechanisms and Drug Responses. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19:jjae152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cao M, Chan RWS, Cheng FHC, Li J, Li T, Pang RTK, Lee CL, Li RHW, Ng EHY, Chiu PCN, Yeung WSB. Myometrial Cells Stimulate Self-Renewal of Endometrial Mesenchymal Stem-Like Cells Through WNT5A/β-Catenin Signaling. Stem Cells. 2019;37:1455-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cosín-Roger J, Ortiz-Masiá D, Calatayud S, Hernández C, Esplugues JV, Barrachina MD. The activation of Wnt signaling by a STAT6-dependent macrophage phenotype promotes mucosal repair in murine IBD. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:986-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dong Y, Fan H, Zhang Z, Jiang F, Li M, Zhou H, Guo W, Zhang Z, Kang Z, Gui Y, Shou Z, Li J, Zhu R, Fu Y, Sarapultsev A, Wang H, Luo S, Zhang G, Hu D. Berberine ameliorates DSS-induced intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction through microbiota-dependence and Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:1381-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Buttar J, Kon E, Lee A, Kaur G, Lunken G. Effect of diet on the gut mycobiome and potential implications in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2399360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lin YF, Sung CM, Ke HM, Kuo CJ, Liu WA, Tsai WS, Lin CY, Cheng HT, Lu MJ, Tsai IJ, Hsieh SY. The rectal mucosal but not fecal microbiota detects subclinical ulcerative colitis. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mills RH, Dulai PS, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Sauceda C, Daniel N, Gerner RR, Batachari LE, Malfavon M, Zhu Q, Weldon K, Humphrey G, Carrillo-Terrazas M, Goldasich LD, Bryant M, Raffatellu M, Quinn RA, Gewirtz AT, Chassaing B, Chu H, Sandborn WJ, Dorrestein PC, Knight R, Gonzalez DJ. Multi-omics analyses of the ulcerative colitis gut microbiome link Bacteroides vulgatus proteases with disease severity. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7:262-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wang C, Guo H, Bai J, Yu L, Tian F, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W, Zhai Q. The roles of different Bacteroides uniformis strains in alleviating DSS-induced ulcerative colitis and related functional genes. Food Funct. 2024;15:3327-3339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nie Q, Luo X, Wang K, Ding Y, Jia S, Zhao Q, Li M, Zhang J, Zhuo Y, Lin J, Guo C, Zhang Z, Liu H, Zeng G, You J, Sun L, Lu H, Ma M, Jia Y, Zheng MH, Pang Y, Qiao J, Jiang C. Gut symbionts alleviate MASH through a secondary bile acid biosynthetic pathway. Cell. 2024;187:2717-2734.e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 86.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Le HH, Lee MT, Besler KR, Comrie JMC, Johnson EL. Characterization of interactions of dietary cholesterol with the murine and human gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7:1390-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yan Y, Lei Y, Qu Y, Fan Z, Zhang T, Xu Y, Du Q, Brugger D, Chen Y, Zhang K, Zhang E. Bacteroides uniformis-induced perturbations in colonic microbiota and bile acid levels inhibit TH17 differentiation and ameliorate colitis developments. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2023;9:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Xu P, Xi Y, Kim JW, Zhu J, Zhang M, Xu M, Ren S, Yang D, Ma X, Xie W. Sulfation of chondroitin and bile acids converges to antagonize Wnt/β-catenin signaling and inhibit APC deficiency-induced gut tumorigenesis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14:1241-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yao Y, Li X, Xu B, Luo L, Guo Q, Wang X, Sun L, Zhang Z, Li P. Cholecystectomy promotes colon carcinogenesis by activating the Wnt signaling pathway by increasing the deoxycholic acid level. Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fan Q, Guan X, Hou Y, Liu Y, Wei W, Cai X, Zhang Y, Wang G, Zheng X, Hao H. Paeoniflorin modulates gut microbial production of indole-3-lactate and epithelial autophagy to alleviate colitis in mice. Phytomedicine. 2020;79:153345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Liu C, Wu Y, Wang Y, Yang F, Ren L, Wu H, Yu Y. Integrating 16 S rRNA gene sequencing and metabolomics analysis to reveal the mechanism of Angelica sinensis oil in alleviating ulcerative colitis in mice. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2024;249:116367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wang Y, You K, You Y, Li Q, Feng G, Ni J, Cao X, Zhang X, Wang Y, Bao W, Wang X, Chen T, Li H, Huang Y, Lyu J, Yu S, Li H, Xu S, Zeng K, Shen X. Paeoniflorin prevents aberrant proliferation and differentiation of intestinal stem cells by controlling C1q release from macrophages in chronic colitis. Pharmacol Res. 2022;182:106309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li Y, Wu Y, Liang J, Chen P, Xu S, Wang Y, Jiang Z, Zhu X, Lin C, Yu Y, Tang H. Ligustilide Suppresses Macrophage-Mediated Intestinal Inflammation and Restores Gut Barrier via EGR1-ADAM17-TNF-α Pathway in Colitis Mice. Research (Wash D C). 2025;8:0864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dong J, Li L, Zhang X, Yin X, Chen Z. CtBP2 Regulates Wnt Signal Through EGR1 to Influence the Proliferation and Apoptosis of DLBCL Cells. Mol Carcinog. 2025;64:959-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tang Y, Wang Z, Zhou F, Li L, Sun C, Li L, Tang F, Huang D, Li Z, Tan Y, Pei G. Benzoylpaeoniflorin alleviates ulcerative colitis by inhibiting ferroptosis through targeting phosphogluconic dehydrogenase. Phytomedicine. 2025;147:157111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhao Y, Chen C, Xiao X, Fang L, Cheng X, Chang Y, Peng F, Wang J, Shen S, Wu S, Huang Y, Cai W, Zhou L, Qiu W. Teriflunomide Promotes Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity by Upregulating Claudin-1 via the Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway in Multiple Sclerosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61:1936-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/