Published online Jan 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i4.115040

Revised: November 21, 2025

Accepted: December 29, 2025

Published online: January 28, 2026

Processing time: 108 Days and 16.6 Hours

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, gastrointestinal condition in

To analyze the antibiotic consumption of IBD inpatients and project future re

We retrospectively collected the demographic and antibiotic usage data from the IBD patients hospitalized between 2015 and 2024. The antibiotics were classified, and the consumption intensity was calculated. The appropriate statistical methods were applied to compare the differences between groups. The Monte Carlo simulation was used to forecast the antibiotic consumption from 2025 to 2027.

A total of 1985 hospitalizations and 372 antibiotic prescriptions were included in this work. The antibiotic-exposed patients were older, had longer hospital stays, and higher costs. Males and ulcerative colitis patients showed a higher antibiotic usage. The highest consumption was observed in 2019, 2022, and 2024. The common indications were intestinal infections and perioperative prophylaxis. Cephalosporins and β-lactam antimicrobials were most commonly used, while carbapenems and glycopeptide antibacterials increased during 2022-2024. Although the antibiotic usage rates decreased in 2020-2024 when compared to 2015-2019, the consumption intensity significantly increased. The Monte Carlo simulation projected a 170.0% (95% uncertainty interval: -42.1% to 689.7%) consum

These findings highlight the need to strengthen antibiotic stewardship and infection control strategies in IBD inpatient management to prevent further escalation of antimicrobial resistance.

Core Tip: This retrospective study analyzed antibiotic consumption of hospitalized Inflammatory bowel disease patients and predicted future trends. Among hospitalized patients, the usage of antibiotics was higher in elderly patients, male patients, and those with ulcerative colitis. The study also found that although the overall usage rate has declined in recent years, the use of “last-resort” antibiotics has significantly increased. The Monte Carlo simulation predicts that antibiotic consumption will double by 2027. These findings indicate an urgent need for targeted antimicrobial management.

- Citation: Zeng W, Zhang WK, Xu D, He K, Huang YP, Liu YX, Yang HF. Antibiotic consumption of inpatients with inflammatory bowel disease during 2015-2024 and future prediction: Evidence from a general hospital. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(4): 115040

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i4/115040.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i4.115040

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a non-infectious, chronic intestinal disorder involving a complex diagnostic and therapeutic process and typically categorized into two subtypes: Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)[1]. The IBD treatment includes amino-salicylates, glucocorticoids, immunomodulators, biologics and small-molecule drugs[1]. IBD is thought to develop as a result of the interactions between environmental, microbial, and immune-mediated factors in a genetically susceptible host. Studies on IBD and gut microbiota are currently gaining increasing attention. Several studies showed that the gut microbiota in patients with IBD differ from that in healthy individuals[2-5]. Specifically, patients with IBD are typically characterized by an increased ratio of potentially pathogenic (e.g., Fusobacterium) to beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium longum), as well as a lower overall diversity[3]. Antibiotics are not therapeutic IBD medications, but they are frequently used to reverse the dysbiosis between hosts and gut microbiota or treat bacterial infections occurring secondary to immunosuppressive therapies. Hence, the antibiotic consumption in patients with IBD is tremendous.

Patients with IBD are at a high risk for opportunistic infections. A previous study reported that in the IBD population, the incidence rate of serious infections ranged from 10 to 100 events per 1000 person-years, which was more than 10-fold higher than that for opportunistic infections in the general population[6]. Moreover, approximately 4% of patients with IBD would die from serious infections[6]. An overall infection incidence rate of 172.7 per 100 person-years was reported among patients with IBD[7]. Extensive antibiotic use will lead to another global public health issue: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR). A systematic analysis presented that 4.95 million deaths in 2019 were associated with the bacterial AMR[8]. This situation becomes even more serious without proper management. Abdominal infections, which are common in IBD, are especially reported as one of the main contributors to the global AMR burden[8].

In the past, greater attention was paid to the adverse infection events related to the clinical management of patients with IBD: The infected patients with IBD would face a higher disease burden, including a higher rate of 6-month re

This work was a retrospective, longitudinal study covering a 10-year period. The inclusion criteria were defined as patients who were diagnosed with IBD[10], and hospitalized at the Central Hospital of Shaoyang from January 2015 to December 2024. Patients with severe liver impairment (alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase higher than 3 times upper limit of normal), renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 90 mL/minute per 1.73 m2), as well as those with IBD who are pregnant or breastfeeding, were excluded. We meticulously recorded every hospitalization course of each IBD patients.

The patients’ demographic and clinical data were systematically collected via the electronic medical records system. The collected information included age, gender, IBD classification (i.e., UC or CD), and antibiotic treatment prescriptions during hospitalization. All data were de-identified and subsequently transferred to a specialized database for further analysis.

Physicians have strictly adhered to guidelines when prescribing antibiotics to IBD patients who required them[11,12]. A comprehensive review of the patients’ medical orders and prescription records was performed to systematically collect and record antimicrobial drug use during hospitalization. The specific information recorded included the drug name, daily dosage, administration route, treatment duration, and indications for antibiotics. According to the consensus, the indications for antibiotics among IBD patients could generally be classified such as intestinal infection, extra intestinal infection, perianal infection, perioperative prophylaxis and so on[11]. All antibiotics were classified and labeled according to the World Health Organization (WHO)’s classification system[13].

We accurately assessed the antibiotics consumption by using the defined daily dose (DDD) as the measurement unit and calculating the DDD per 100 bed-days, as recommended by the WHO. The calculation formula is as follows: The total antibiotic consumption divided by the total number of patient bed-days multiplied by 100 afterward. The specific DDD values for the medications can be found in the previous studies[14].

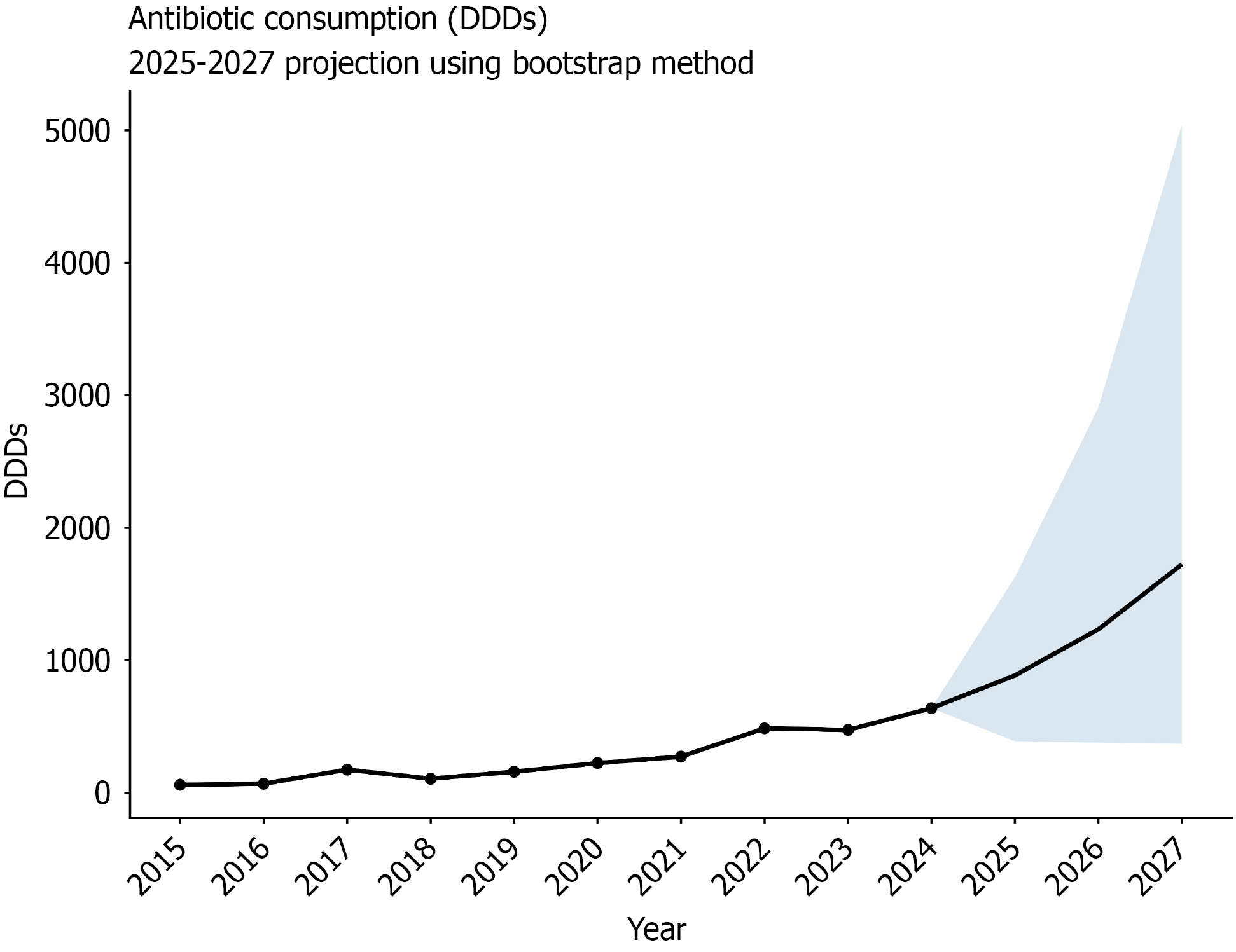

According to previous studies[15], and data from the past ten years on antibiotic consumption (2015-2024), the Monte Carlo simulation was used herein to predict the antibiotic consumption in the next three years. An empirical bootstrap of the year-to-year growth rates for 2016-2023 was employed (5000 of iterations, random seed 123); the random variable was set as the year-on-year growth rate (n = 8). Model validation showed that the 95% prediction interval covered 100% of the historical data from 2020-2023 (4/4 years), indicating that the interval width was appropriate (Supplementary Figure 1). Using 2024 as the baseline, the same bootstrap distribution was rolled forward to generate probabilistic prediction for 2025-2027.

Data cleaning and statistical analysis were performed using R software. The continuous variables with a normal distribution were described using the mean ± SD, while the non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range). The categorical variables were presented as n (%). The between-group comparisons were conducted using t tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, χ2 tests, or Fisher’s tests. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shaoyang Central Hospital (No. KY 2025-002-10). In view of the retrospective nature of this study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

A total of 1985 admissions were recorded from 2015 to 2024. The count of antibiotic prescriptions was 372. The antibiotic exposure rate in the IBD population was approximately 18.7% over the past 10 years. Table 1 shows all characteristics of the subjects along with their records.

| Variables | Antibiotics exposure (n = 372) | Non-antibiotics exposure (n = 1613) | P value |

| Age, year, median IQR | 50.00 (33.00, 62.00) | 37.00 (25.00, 53.00) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.020 | ||

| Male | 264 (20.5) | 1024 (79.5) | |

| Female | 108 (15.9) | 571 (84.1) | |

| Subtypes | < 0.001 | ||

| UC | 192 (23.8) | 615 (76.2) | |

| CD | 180 (15.3) | 998 (84.7) | |

| Length of stay, day(s), median (IQR) | 11.00 (7.00, 14.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 4.00)1 | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization costs, 1000 CNY, median (IQR) | 8.94 (5.81, 15.74) | 3.15 (0.33, 6.14) | < 0.001 |

The comparisons were analyzed from the following aspects: Age, gender, disease subtypes, length of stay, and hospitalization costs. The results showed that patients with IBD in the antibiotic-exposed group were older (P < 0.001), and there was a higher proportion of males (20.5%) compared to females (15.9%) (P = 0.020). The antibiotic exposure rates were significantly higher in patients with UC (23.8%) compared to those with CD (15.3%) (P < 0.001). The study also revealed that patients with IBD with antibiotic consumption had significantly longer hospital stays (P < 0.001) and spent higher hospitalization costs (P < 0.001) compared to those without antibiotic consumption (Table 1).

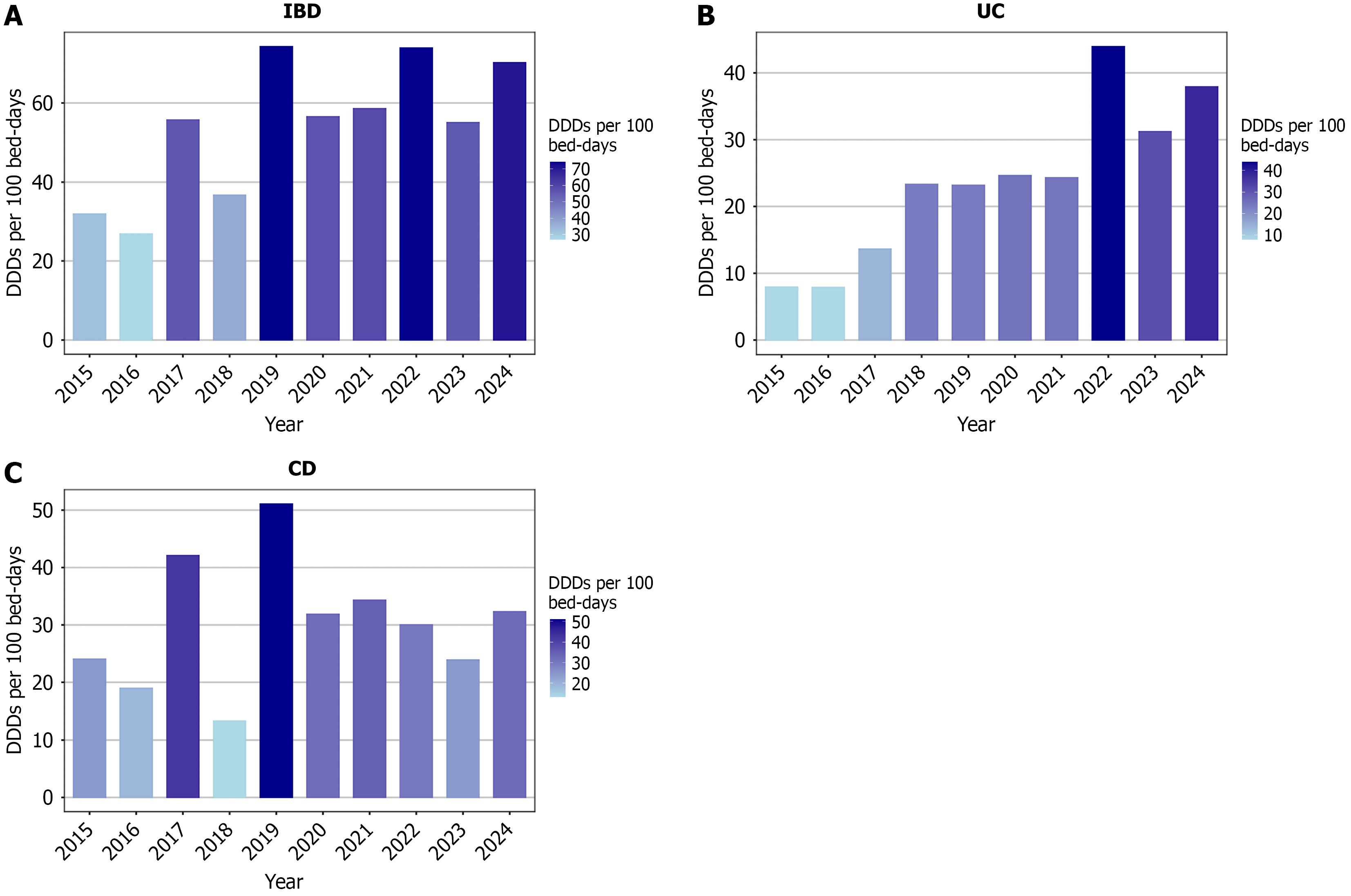

This study revealed the variations across the years in the analysis of annual antibiotic consumption. The highest antibiotic consumption was observed in 2019, 2022, and 2024, with the DDDs per 100 bed-days exceeding 70 in all these years. In contrast, the lowest consumption was observed in 2015, 2016, and 2018, with the DDDs per 100 bed-days being less than 40 (Figure 1A).

Moreover, the subgroup analysis indicated differences between patients with UC and CD. Patients with UC showed antibiotic consumption that presented three phases: (1) A low-consumption phase from 2015 to 2017, with DDDs per 100 bed-days being consistently below 15; (2) A moderate-consumption phase from 2018 to 2021, with values being approximately 24; and (3) A high-consumption phase from 2022 to 2024, with the consumption being higher than 30 DDDs per 100 bed-days, peaking at approximately 44 in 2022 (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, no clear temporal trend was observed among the CD patients. The lowest and highest consumptions were recorded in 2018 and 2019. After 2020, the consumption generally remained within the range of the 30-35 DDDs per 100 bed-days, except for 2023 (Figure 1C).

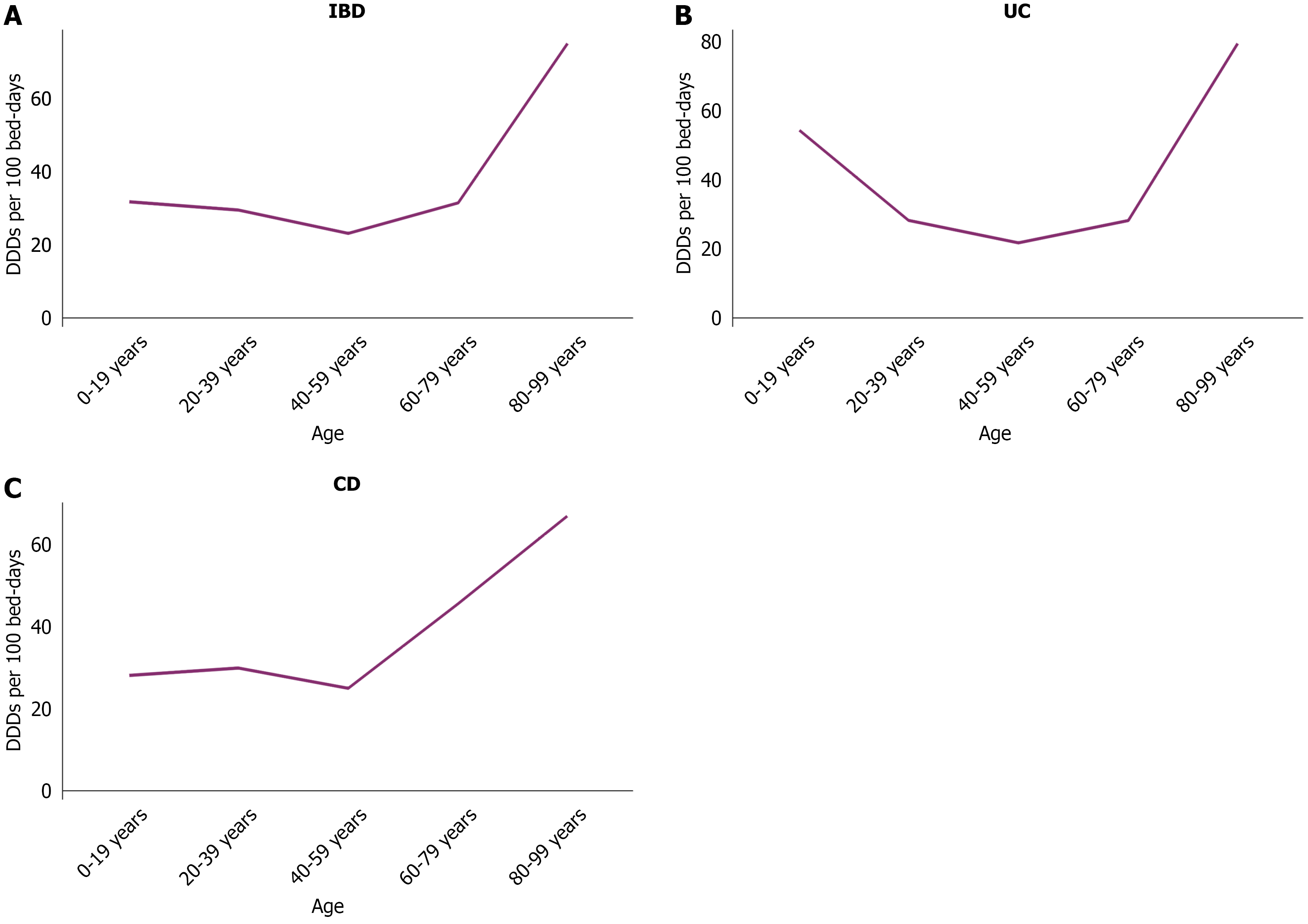

Overall, in the IBD population, the highest antibiotic consumption was observed in the oldest age group (80-99 years), with 75.16 DDDs per 100 bed-days. The consumption in the other age groups remained in the range of the 20-30 DDDs per 100 bed-days (Figure 2A). A further analysis by the disease subtype revealed that patients with UC exhibited a higher antibiotic consumption in the two age groups of 0-19 years and 80-99 years with a relatively lower consumption in the intermediate age groups (Figure 2B). Among patients with CD, the antibiotic consumption remained at approximately 30 DDDs per 100 bed-days before the age of 60 and increased markedly thereafter, peaking at 67.12 DDDs per 100 bed-days in the 80-99 years group (Figure 2C).

The indications for the antibiotic usage in this study were recorded and classified in UC and CD. The results showed that the most common reason for the antibiotic consumption in patients with UC was intestinal infection, accounting for 58.21% of the cases, including 19 (9.45%) cases of Clostridium difficile infection. The other indications included pulmonary tract infection (20.40%), perioperative prophylaxis (7.46%), and intestinal obstruction (3.98%) (Figure 3A). Among patients with CD, perianal disease was the most common indication that accounted for 21.84% of cases, followed by intestinal infection (16.99%), perioperative prophylaxis (16.50%), and intestinal obstruction (16.02%) (Figure 3B). Overall, the antibiotic consumption indications were similar in both IBD subtypes.

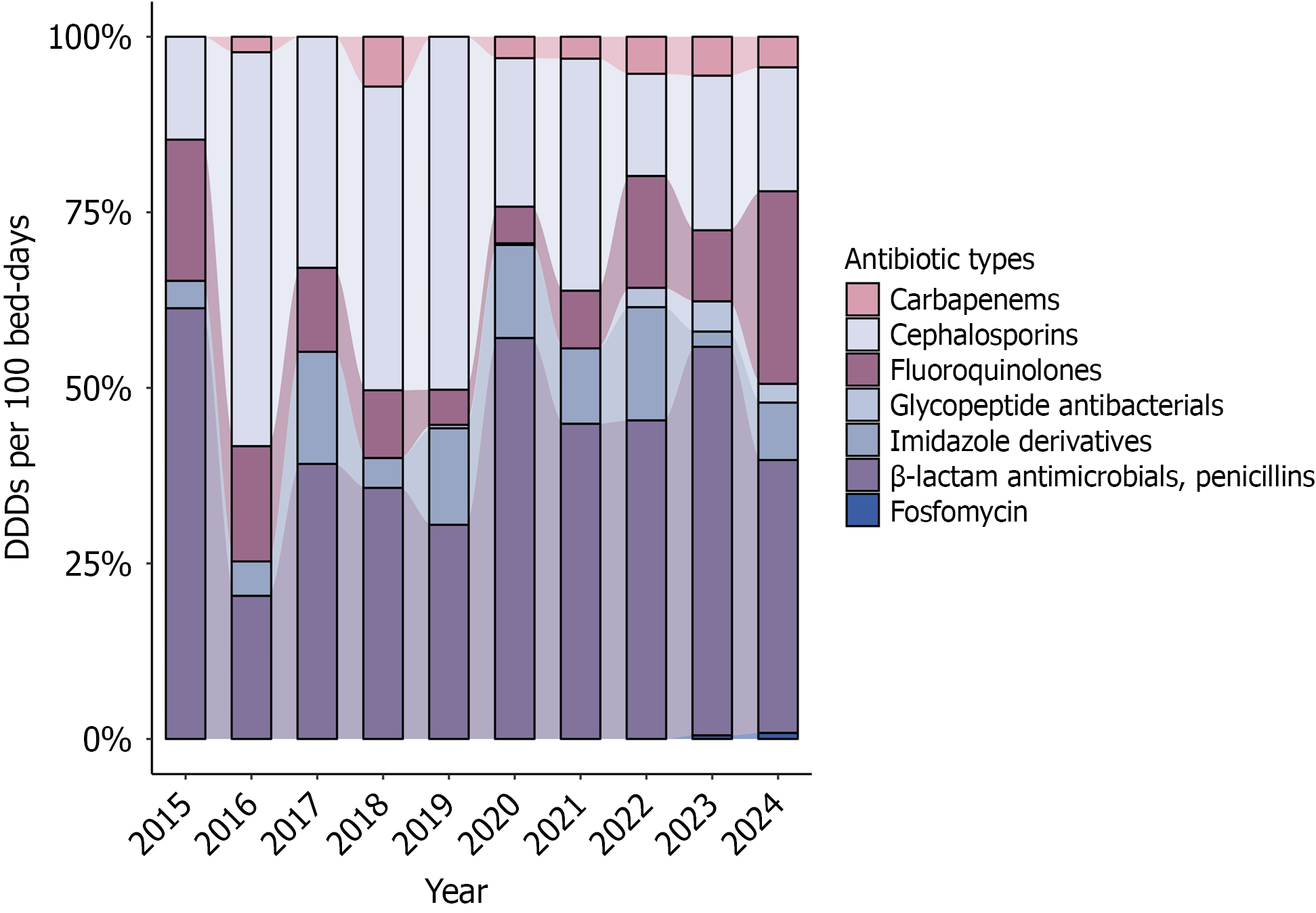

The antibiotic prescriptions in this study were categorized into the following seven classes based on the WHO classification system: Cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, β-lactam antimicrobials/penicillins, imidazole derivatives, carbapenems, glycopeptide antibacterials, and other antibacterials (i.e., only fosfomycin). All the glycopeptide antibacterial prescriptions in this work were vancomycin. Over the ten-year period, the β-lactam antimicrobials were the most consumed, with the cephalosporins being the second most used. The fluoroquinolones and imidazole derivatives also substantially contributed to the overall consumption. Notably, the usage of the “last-resort” antibiotics, carbapenems, and vancomycin showed a gradual increase in their proportion, especially in the last 3 years (2022-2024). Fosfomycin was also applied in one patient with CD in xx and one patient with UC in 2024 (Figure 4).

This study compared the antibiotic uses in patients with IBD across two time periods: 2015-2019 and 2020-2024. The results showed no significant differences in the age of patients who received antibiotics between these two periods and in the length of stay and hospitalization costs. Although the antibiotic exposure rate decreased in 2020-2024 compared with the earlier 5-year period, the antibiotic use intensity significantly increased. As for the antibiotic classifications, the use of imidazole derivatives significantly decreased (12.7% vs 3.8%, P = 0.001), while the usage rates of the β-lactam antimicrobials, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones were similar. Moreover, the carbapenem, vancomycin, and fosfomycin prescriptions were recorded in 2020-2024, an observation not found during 2015-2019 (Table 2). The comparisons in the UC and CD populations are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

| Variables | 2015-2019 (n = 102) | 2020-2024 (n = 270) | P value |

| Age, year, median (IQR) | 49.50 (37.00, 61.00) | 50.00 (31.50, 62.00) | 0.887 |

| Length of stay, day(s), median (IQR) | 10.00 (6.00, 14.00) | 11.00 (7.00, 15.00) | 0.379 |

| Hospitalization costs, 1000 CNY, median (IQR) | 7.63 (5.27, 15.11) | 9.72 (5.94, 16.36) | 0.812 |

| Rate, % | 33.89 | 15.93 | < 0.001 |

| DDDs per 100 bed-days, median (IQR) | 49.54 (24.29, 78.57) | 68.73 (43.75, 85.96) | < 0.001 |

| Classifications | |||

| β-lactam antimicrobials/penicillins | 44 (43.2) | 140 (51.8) | 0.134 |

| Cephalosporins | 34 (33.3) | 68 (25.2) | 0.116 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 11 (10.8) | 39 (14.4) | 0.356 |

| Imidazole derivatives | 13 (12.7) | 10 (3.8) | 0.001 |

| Carbapenems | 0 (0) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Glycopeptide antibacterials | 0 (0) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Other antibacterials | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) |

In 2025, the estimated antibiotic consumption of patients with IBD was 885.67 DDDs [95% uncertainty interval (UI): 388.55 DDDs to 1627.69 DDDs], depicting an increase of 459.6% (95%UI: 145.5% to 928.4%) compared to 2019, and a 38.7% (95%UI: -39.1% to 164.9%) increase compared to 2024. Assuming the future consumption within the current ranges of the study period and assuming no policy changes, our projections suggest that the IBD-related antibiotic consumption in 2026 could increase by 93.2% (95%UI: -40.6% to 355.4%) compared to 2024, approaching 1233.86 DDDs (95%UI: 379.06 DDDs to 2908.11 DDDs), and by 170.0% (95%UI: -42.1% to 689.7%) in 2027, approximately 1723.95 DDDs (95%UI: 369.80 DDDs to 5042.61 DDDs) (Figure 5).

This study retrospectively analyzed the details of the antibiotic consumption of hospitalized patients with IBD over the past 10 years, including the annual consumption levels, age-related characteristics, indications and antibiotic classes. A comparative analysis was also performed between 2015-2019 and 2020-2024. Finally, the Monte Carlo simulation was applied to predict the antibiotic consumption levels in patients with IBD for the next 3 years. Overall, this was the first study to systematically describe the antibiotic consumption in the IBD population.

We recorded all detailed information on antibiotic usage among IBD patients, reflecting the various challenges faced by individuals with IBD. In our study, the rate of antibiotic usage was 18.7% (372 of 1985), which was lower than the 30.3% (19303 of 63759) observed in another study[16]. This might be different from the data sources of the two studies, and also reflected differences in infection risk of IBD population of different race. The analysis results as regards the subjects’ hospitalization data revealed that advanced age is an independent risk factor for antibiotic exposure in patients with IBD. This finding was correlated with the infection risks observed across different age groups of patients with IBD. A previous study indicated that compared to younger patients, patients aged 65 years and older have a significantly increased risk of severe infections when using thiopurine drugs and when undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy, increasing the treatment requirement for antibiotics in this population[17]. In terms of gender, males exhibited higher antibiotic usage rates, which might be associated with the lower incidence rate of intestinal perforation and abdominal surgery in females reported in previous studies[18,19]. After all, intestinal perforation and surgery were high demand for antibiotics. As for the different disease subtypes, the antibiotic usage rates were significantly higher among patients with UC than among patients with CD. This variation might be related to the predilection locations of the two diseases: UC predominantly affected the rectum and the sigmoid colon, whereas CD primarily affected the terminal ileum[20,21]. The composition of the gut microbiota and the associated infection risks were significantly different across these intestinal locations, consequently influencing the frequency of the antibiotic administration[22,23]. Additionally, patients with IBD who have concurrent infections must suppress the infection before safely initiating immunosuppressive agents or biologic treatments, resulting in significantly higher overall hospitalization durations and expenses for patients exposed to antibiotics.

According to the annual analysis, the antibiotic usage intensity exhibited periodic increases. This trend might be attributed to both enhanced disease awareness among patients with IBD and changes in the spectrum of infectious pathogens, as well as adjustments in the antimicrobial selections. This study showed that from 2022 to 2024, the use of “last-resort” antibiotics significantly increased, accounting for up to 5% of all antibiotic prescriptions, similar to the global antibiotic consumption trends[15]. This increase was partly caused by the fact that Clostridium difficile and AMR bacteria relied on these medications to improve the clinical outcomes for patients with IBD. Given the use of antibiotics without prescription in several countries which might be the main cause lead to AMR[24], educational campaigns need to enhance. Regarding indications for antibiotics, the reasons for the antibiotic administration in patients with IBD include intestinal infections, perianal diseases, pulmonary and urinary tract infections, and perioperative prophylaxis, consistent with previous epidemiological findings[7]. From an age perspective, elderly patients with IBD showed significantly higher antibiotic consumption levels potentially linked to their diminished immune function and increased infection risk and which might be associated with the second peak in the IBD onset[25].

Comparing the periods of 2015-2019 and 2020-2024, no significant differences were observed as regards the de

Our analysis has some limitations. First, this work was a single-center study with findings that may not be directly generalizable to the IBD populations in other regions or countries. Second, the frequent antibiotic updates, along with the evolving drug types and treatment strategies, may cause biases. Variations in patients’ economic circumstances could also influence the antibiotic selection, potentially affecting the consumption level assessments. Nevertheless, our study indicated that antibiotic consumption represents a significant component of the clinical practice for patients with IBD, offering new perspectives and evidence for comprehensively optimizing IBD clinical management.

This study demonstrates that antibiotic consumption of hospitalized patients with IBD has remained high over the past decade, with recent increases in broad-spectrum and last-resort antibiotics. These trends underline the growing public health challenge associated with AMR in the IBD population. Strengthening antimicrobial stewardship programs, optimizing infection surveillance, and standardizing perioperative and empiric antibiotic prescribing protocols are essential to reducing unnecessary antibiotic exposure and preventing further resistance escalation.

We thank Professor Xin C for his guidance on the statistical aspects of this study.

| 1. | Chang JT. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2652-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 904] [Article Influence: 150.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen-Liaw A, Aggarwala V, Mogno I, Haifer C, Li Z, Eggers J, Helmus D, Hart A, Wehkamp J, Lamousé-Smith ESN, Kerby RL, Rey FE, Colombel JF, Kamm MA, Olle B, Norman JM, Menon R, Watson AR, Crossette E, Terveer EM, Keller JJ, Borody TJ, Grinspan A, Paramsothy S, Kaakoush NO, Dubinsky MC, Faith JJ. Gut microbiota strain richness is species specific and affects engraftment. Nature. 2025;637:422-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iliev ID, Ananthakrishnan AN, Guo CJ. Microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanisms of disease and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025;23:509-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Turpin W, Lee SH, Croitoru K. Gut Microbiome Signature in Predisease Phase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prediction to Pathogenesis to Prevention. Gastroenterology. 2025;168:902-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zheng J, Sun Q, Zhang M, Liu C, Su Q, Zhang L, Xu Z, Lu W, Ching J, Tang W, Cheung CP, Hamilton AL, Wilson O'Brien AL, Wei SC, Bernstein CN, Rubin DT, Chang EB, Morrison M, Kamm MA, Chan FKL, Zhang J, Ng SC. Noninvasive, microbiome-based diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Med. 2024;30:3555-3567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Beaugerie L, Rahier JF, Kirchgesner J. Predicting, Preventing, and Managing Treatment-Related Complications in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1324-1335.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rezazadeh Ardabili A, Van Esser D, Wintjens D, Cilissen M, Deben D, Mujagic Z, Russ F, Stassen L, Van Bodegraven A, Wong D, Winkens B, Jonkers D, Romberg-Camps M, Pierik M. The Risk of Mild, Moderate, and Severe Infections in IBD patients - A prospective, multicentre observational cohort study (PRIQ). J Crohns Colitis. 2025;jjaf112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8908] [Cited by in RCA: 8966] [Article Influence: 2241.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Venkat PG, Nguyen NH, Luo J, Qian AS, Khanna S, Singh S. Impact of recurrent hospitalization for Clostridioides difficile on longitudinal outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a nationally representative cohort. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221141501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Moran GW, Gordon M, Sinopolou V, Radford SJ, Darie AM, Vuyyuru SK, Alrubaiy L, Arebi N, Blackwell J, Butler TD, Chew T, Colwill M, Cooney R, De Marco G, Din S, Din S, Feakins R, Gasparetto M, Gordon H, Hansen R, Kok KB, Lamb CA, Limdi J, Liu E, Loughrey MB, McGonagle D, Patel K, Pavlidis P, Selinger C, Shale M, Smith PJ, Subramanian S, Taylor SA, Tun GSZ, Verma AM, Wong NACS; IBD guideline development group. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on inflammatory bowel disease in adults: 2025. Gut. 2025;74:s1-s101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, Rahier JF, Verstockt B, Abreu C, Albuquerque A, Allocca M, Esteve M, Farraye FA, Gordon H, Karmiris K, Kopylov U, Kirchgesner J, MacMahon E, Magro F, Maaser C, de Ridder L, Taxonera C, Toruner M, Tremblay L, Scharl M, Viget N, Zabana Y, Vavricka S. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:879-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (32)] |

| 12. | Sharland M, Cappello B, Ombajo LA, Bazira J, Chitatanga R, Chuki P, Gandra S, Harbarth S, Loeb M, Mendelson M, Moja L, Pulcini C, Tacconelli E, Zanichelli V, Zeng M, Huttner BD. The WHO AWaRe Antibiotic Book: providing guidance on optimal use and informing policy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1528-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | NIPH. ATC/DDD Index 2024. [cited December 22, 2025]. Available from: https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/?code=J01CE&showdescription=no. |

| 14. | Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, Pant S, Gandra S, Levin SA, Goossens H, Laxminarayan R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E3463-E3470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1795] [Cited by in RCA: 1895] [Article Influence: 236.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Klein EY, Impalli I, Poleon S, Denoel P, Cipriano M, Van Boeckel TP, Pecetta S, Bloom DE, Nandi A. Global trends in antibiotic consumption during 2016-2023 and future projections through 2030. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:e2411919121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Khan N, Vallarino C, Lissoos T, Darr U, Luo M. Risk of Infection and Types of Infection Among Elderly Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Retrospective Database Analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lynn AM, Loftus EV Jr. Illuminating the Black Box: The Real Risk of Serious Infection With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Therapies. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:262-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gargallo-Puyuelo CJ, Ricart E, Iglesias E, de Francisco R, Gisbert JP, Taxonera C, Mañosa M, Aguas Peris M, Navarrete-Muñoz EM, Sanahuja A, Guardiola J, Mesonero F, Rivero Tirado M, Barrio J, Vera Mendoza I, de Castro Parga L, García-Planella E, Calvet X, Martín Arranz MD, García S, Sicilia B, Carpio D, Domenech E, Gomollón F; ENEIDA registry of GETECCU. Sex-Related Differences in the Phenotype and Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: SEXEII Study of ENEIDA. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:2280-2290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Verstockt B, Salas A, Sands BE, Abraham C, Leibovitzh H, Neurath MF, Vande Casteele N; Alimentiv Translational Research Consortium (ATRC). IL-12 and IL-23 pathway inhibition in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:433-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Le Berre C, Honap S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2023;402:571-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 965] [Reference Citation Analysis (104)] |

| 21. | Dolinger M, Torres J, Vermeire S. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2024;403:1177-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 151.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (104)] |

| 22. | Yang K, Li G, Li Q, Wang W, Zhao X, Shao N, Qiu H, Liu J, Xu L, Zhao J. Distribution of gut microbiota across intestinal segments and their impact on human physiological and pathological processes. Cell Biosci. 2025;15:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McCallum G, Tropini C. The gut microbiota and its biogeography. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2024;22:105-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 92.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mulchandani R, Wang Y, Gilbert M, Van Boeckel TP. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food-producing animals: 2020 to 2030. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3:e0001305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 82.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 25. | Xu L, He B, Sun Y, Li J, Shen P, Hu L, Liu G, Wang J, Duan L, Zhan S, Wang S. Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Urban China: A Nationwide Population-based Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:3379-3386.e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/