Published online Jan 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i4.112698

Revised: November 22, 2025

Accepted: December 29, 2025

Published online: January 28, 2026

Processing time: 172 Days and 7.3 Hours

One of the main aims of colonoscopy is to detect and remove precancerous po

To evaluate how varying levels of endoscopist use of CADe affect adenoma de

A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary Australian center after introduction of the Olympus Endo-AID® CADe module in July 2023, available for all elective procedures. Colonoscopy reports from six months before and after implementation were reviewed. Endoscopists were grouped by observed CADe usage. The primary outcome was change in ADR by group. Secondary outcomes included sessile serrated lesion detection rate (SSL-DR), adenomas per patient (APP), and sessile serrated lesions per patient (SPP).

Seven endoscopists performed 636 pre-CADe and 386 post-CADe colonoscopies. Two endoscopists used CADe 100% of the time, four used it 50%-99%, and one did not use CADe. No endoscopists used CADe 1%-50% of the time. ADR significantly improved from 29% to 41.9% in the 50%-99% group (odds ratio 1.77, 95%CI: 1.13-2.75, P = 0.01). No ADR change was observed in the 100% group, which had a baseline ADR above 60%, although APP increased from 0.90 to 2.08 (relative risk 2.31, 95%CI: 1.97-2.73, P < 0.0001). SSL-DR and SPP were not significantly affected by CADe.

In this real-world study, the availability of CADe was associated with an uptake by the majority of the en

Core Tip: This study evaluates the real-world impact of varying computer-aided detection (CADe) usage frequency on colonoscopy quality metrics in a tertiary Australian endoscopy center. Endoscopists were stratified by CADe usage, revealing that even partial use (50%-99% of procedures) significantly improved adenoma detection rate (ADR). High-frequency users maintained high ADR, but total adenomas per procedure increased, highlighting additional quality benefits. The findings emphasize that CADe effectiveness depends not only on technology availability but also on endoscopist level of usage, offering insights into optimizing implementation and improving patient outcomes through enhanced polyp detection and risk stratification.

- Citation: Rao V, Walia N, Parkash N, Wanigaratne T, Henshaw S, Chen G, Lo SW, Be KH, Robertson M, Zorron Cheng Tao Pu L. Availability and use of computer-aided detection during colonoscopy: A real-world observational study at an Australian tertiary center. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(4): 112698

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i4/112698.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i4.112698

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is highly prevalent worldwide[1]. It is the fourth most common cancer in Australia, but the second in number of cancer-related deaths behind lung cancer[2]. Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for CRC screening, playing a pivotal role in prevention of CRC by detecting and removing precancerous and early cancerous polyps. Adenoma detection rate (ADR), defined as the percentage of colonoscopies that detect at least one adenomatous polyp, is an important marker of colonoscopy quality. ADR has shown to be inversely correlated to the risk of post-colonoscopy CRC and cancer mortality/morbidity[3]. Many Gastrointestinal Societies are increasingly advocating for higher minimum standards for ADRs, reflecting the demonstrated benefits of elevated ADRs in multiple observational studies[4]. The American College of Gastroenterology recently raised their recommended ADR from 25% to 35%, ad

Since the early 2000s, AI has been gradually integrated into gastroenterology practice with the most prominent example being computer-aided detection (CADe). CADe aims to increase the detection of suspicious colorectal lesions, usually highlighting any suspicious lesions on screen with a green box around the area of interest. Multiple multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the efficacy of CADe in increasing ADR[10-13], with studies predominantly conducted in China, United States of America and Europe.

Despite the promising results of RCTs, real world studies have revealed more variable outcomes. A recent meta-analysis by Wei et al[14] revealed that CADe only modestly improved ADR compared to conventional colonoscopy, with this effect only noted in prospective studies and not in retrospective studies. The discrepancy between RCTs and real-world studies may be attributed to numerous factors, including more effective bowel preparation in RCTs, heightened operator awareness of being observed in controlled settings, variations in endoscopy proficiency, and differences in the familiarity and uptake of CADe.

The availability of CADe in Australian settings is inconsistent, and even where it is accessible, its uptake amongst endoscopists is variable. The only observational study conducted in Australia to date in this area, by Goetz et al[15], observed the effect of CADe in a single center comparing endoscopist ADRs from colonoscopies before and after implementation of CADe. The study found no statistically significant improvement in ADR following the implementation of CADe technology (52.1% for CADe vs 52.6% for conventional colonoscopy). This result may be related to the high baseline ADR in this study. As shown in previous studies, the impact of CADe may be more significant for endoscopists with lower baseline ADR, with Biscaglia et al[16] comparing the ADRs between trainee endoscopists using CADe with those of experienced endoscopists using conventional colonoscopy and noting no significant difference between the two groups. This is important as the real-world setting encompasses a wide range of experience and usage levels among endoscopists.

This study evaluated the real-world impact of the degree of endoscopist use of CADe on adenoma detection in an Australian tertiary endoscopy center where CADe was available for all procedures.

This single-center retrospective observational study, conducted at a tertiary hospital in Melbourne, Australia, evaluated the impact of CADe availability on ADR according to endoscopists’ levels of CADe use during screening, diagnostic, and surveillance colonoscopies. The study was granted ethics approval by the Peninsula Health Human Research Ethics Committee prior to commencement. Patient data was handled in accordance with institutional privacy requirements; all extracted data was de-identified prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality and protect patient privacy. All colonoscopies performed six months prior and six months after the introduction of CADe were considered. Inclusion criteria included: (1) Patients aged 40 years and older; (2) Colonoscopies performed between January 2023 and February 2024; and (3) Procedures conducted for screening, surveillance, or diagnostic purposes. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Procedures not documented in ENDOBASE; (2) Emergency procedures (e.g., for acute colitis, foreign body extraction, suspected active bleeding, or acute obstruction); (3) Planned procedures for polyp removal; or (4) Endoscopists who did not have eligible colonoscopies reported in both the pre- and post-CADe time periods. Endoscopists received no formal training or orientation on CADe usage as part of the study.

We included colonoscopies performed for both screening/surveillance and diagnostic indications in our primary analysis. This decision was guided by evidence demonstrating that ADR is comparable across different procedural indications.

A search query was run via the hospital’s endoscopy report documentation software ENDOBASE looking for procedures performed in the six months before and after the introduction of CADe on July 31, 2023. A repeat search query was run with the assistance of the hospital health and information services team to ensure no procedures were missed. The Endoscopy Nurse Unit Manager, in collaboration with the regular endoscopy nursing team, evaluated the frequency of CADe use for each endoscopist based on recalling their collective direct observation during procedures. Endoscopists were classified into four usage categories: (1) CADe used for all (100%) of procedures; (2) CADe used for most (between 50% and 99%) of the procedures; (3) CADe used for some/Less than half (between 1% and 50%) of the procedures; and (4) CADe not used at all (0%). These thresholds were selected to reflect differences in real-world usage patterns. For each procedure, data collected included patient age, sex, indication for colonoscopy, use of CADe, intubation and total procedure time (including time for polypectomy and any additional procedures), number of polyps sent for histopathological analysis, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), and number of histologically confirmed adenomas. Total procedure time was used as a surrogate for withdrawal time, as withdrawal time was not consistently recorded across all colonoscopies, whereas procedure start and end times were reliably documented.

Colonoscopy reports from January 2023 to February 2024 were reviewed, with data collected on adenomas, sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), and overall polyps detected for each procedure. Additional procedural factors, including the BBPS score and total procedure time, were also recorded. The primary outcome was the change in ADR before and after CADe introduction, stratified by the level of CADe use. Secondary outcomes included polyp detection rate (PDR), SSL detection rate (SSL-DR), adenoma per patient (APP) and SSL per patient (SPP).

SPSS Statistics software was used for statistical analysis, with a significance level set at P < 0.05. The comparison of the basal clinical and demographic characteristics was performed by the χ2 test of categorical variables and paired t test for continuous variables.

To examine the independent association of CADe availability and adenoma detection, we performed a multivariate regression analysis using a logistic model with mixed-effects modeling. Clustering by endoscopist was addressed by including a random intercept for endoscopist in the model. This allowed us to estimate the odds of adenoma detection after adjusting for the following potential confounders: Patient age, procedure timing (AM vs PM), total procedure duration, colonoscopy indication (screening, surveillance, or diagnostic), and quality of bowel preparation (BBPS score).

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess whether the effect of CADe differed according to procedural indication. Mixed-effects logistic regression models were repeated separately for screening, surveillance and diagnostic colonoscopies. Each stratified model included the same covariates as the primary analysis (age, procedure timing, bowel preparation quality, and total procedure duration) and incorporated a random intercept for endoscopist to account for clustering.

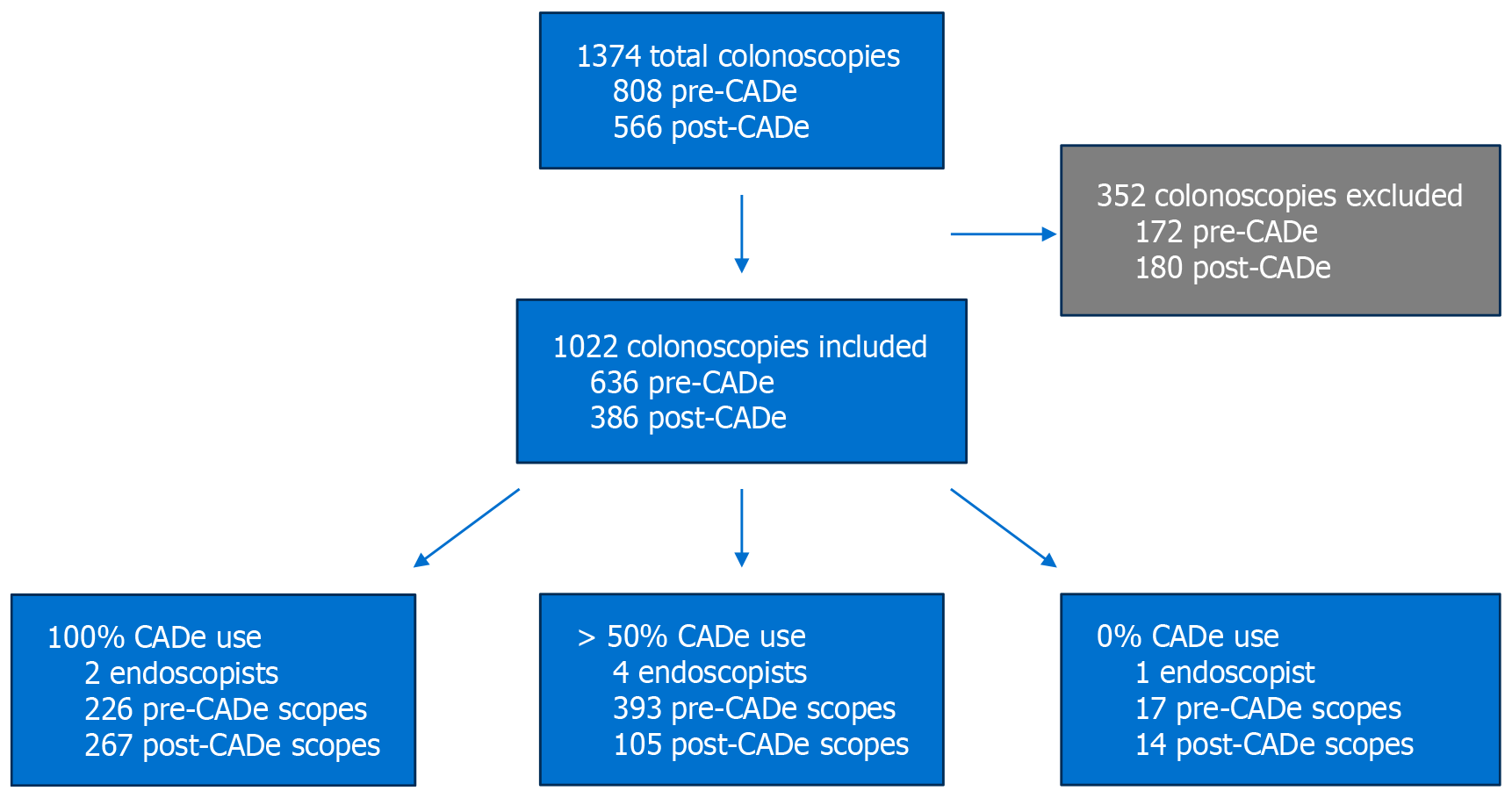

A total of 1374 colonoscopies were identified, of which 352 were excluded, leaving 1022 procedures for analysis. Among these, 636 were performed before the introduction of CADe. Procedures were stratified based on endoscopist CADe usage patterns (Figure 1):

100% CADe use group: Two endoscopists performed 493 colonoscopies (226 pre-CADe, 267 post-CADe).

50%-99% CADe use group: Four endoscopists performed 498 colonoscopies (393 pre-CADe, 105 post-CADe).

0% CADe use group: One endoscopist performed 31 colonoscopies (17 pre-CADe, 14 post-CADe).

The mean age of patients was significantly higher in the post-CADe group compared to the pre-CADe group (59.4 years vs 63.2 years, P < 0.001). The proportion of male patients was nearly identical between groups (47.9% vs 47.8%, P = 0.986). The most common indications for colonoscopy included iron deficiency anaemia, positive faecal occult blood test, and polyp surveillance. While most indications were comparable between study periods, iron deficiency (with or without anaemia) occurred at a significantly higher proportion in the post-CADe group (Table 1). As well, median total procedure time was significantly longer in the post-CADe group compared to the pre-CADe group (23 minutes vs 18 minutes, P < 0.05).

| Characteristic | Pre-CADe | Post-CADe | P value |

| Age (years) | 59.4 (40-89) | 63.2 (41-87) | < 0.001a |

| Male | 299 (47.8) | 173 (47.9) | 0.986 |

| Indication: Iron deficiency ± anaemia | 117 (17.5) | 94 (19.0) | < 0.05b |

| Indication: Faecal occult blood positive | 72 (10.8) | 70 (14.1) | 0.087 |

| Indication: Polyp surveillance | 76 (11.4) | 63 (12.7) | 0.497 |

| Average total BBPS score | 7.3 (3-9) | 7.4 (3-9) | 0.744 |

| Median total procedure time (minute) | 18 (1-169) | 23 (1-408) | < 0.05 |

For endoscopists who used CADe in 100% of cases, PDR had no statistically significant increase: From 82.3% pre-CADe to 78.7% post-CADe [odds ratio (OR) = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.51-1.24, P = 0.31], as well as ADR: From 64.2% to 58.1% (OR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.54-1.11, P = 0.17), and SSL-DR (19.5% pre vs 18.7% post, OR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.61-1.50, P = 0.83). Among endoscopists who adopted CADe in 50% to 99% of procedures, there was a significant increase in both PDR (46.3% pre vs 63.8% post, OR = 2.04, 95%CI: 1.31-3.19, P < 0.01) and ADR (29.0% pre vs 41.9% post, OR = 1.77, 95%CI: 1.13-2.75, P = 0.01). SSL-DR also increased numerically from 9.7% to 11.4%, but this was not statistically significant (OR = 1.2, 95%CI: 0.61-2.40, P = 0.59). For the single endoscopist who did not use CADe, PDR (52.9% pre vs 50.0% post, OR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.22-3.66, P = 0.87, ADR (23.6% to 14.3% (OR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.083-3.51, P = 0.52) and SSL-DR (11.8% to 21.4% (OR = 2.04, 95%CI: 0.29-14.3, P = 0.47), did not show statistical difference (Table 2).

| CADe use (n) | PDR % (No. of procedures) | ADR % (No. of procedures) | SSL-DR % (No. of procedures) | |||||||||

| Pre | Post | OR (CI) | P value | Pre | Post | OR (CI) | P value | Pre | Post | OR (CI) | P value | |

| 100% (2) | 82.3 (226) | 78.7 (267) | 0.79 (0.51-1.24) | 0.31 | 64.2 (226) | 58.1 (267) | 0.77 (0.54-1.11) | 0.17 | 19.5 (226) | 18.7 (267) | 0.83 (0.61-1.50) | 0.83 |

| 50%-99% (4) | 46.3 (393) | 63.8 (105) | 2.04 (1.31-3.19) | < 0.01b | 29.0 (393) | 41.9 (105) | 1.77 (1.13-2.75) | 0.01b | 9.7 (393) | 11.4 (105) | 1.20 (0.61-2.40) | 0.59 |

| 0% (1) | 52.9 (17) | 50.0 (14) | 0.88 (0.22-3.66) | 0.87 | 23.6 (17) | 14.3 (14) | 0.54 (0.083-3.51) | 0.52 | 11.8 (17) | 21.4 (14) | 2.04 (0.29-14.3) | 0.47 |

APP and SPP were analyzed across the three CADe usage groups to assess whether CADe availability influenced the number of adenomas and SSLs detected per procedure.

Endoscopists who used CADe in 100% of procedures demonstrated a significant increase in APP, rising from 0.90 pre-CADe to 2.08 post-CADe [relative risk (RR) = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.97-2.73, P < 0.0001]. This suggests a more than twofold increase in adenomas detected per patient with consistent CADe use. SPP rose from 0.137 pre-CADe to 0.187 post-CADe but this change was not significant (RR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.85-2.21, P = 0.1729).

For the 50%-99% CADe use group, APP did not increase significantly (1.15 pre-CADe to 1.31 post-CADe, RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 0.94-1.39, P = 0.1728). SPP did not change significantly (0.132 pre-CADe to 0.11 post-CADe, RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.42-1.64, P = 0.6680).

The 0% CADe use group showed no significant change in APP from 0.29 pre-CADe to 0.21 post-CADe, with a rate ratio of 0.73 (95%CI: 0.11-3.74, P = 0.6906).

To assess whether CADe influenced the detection of adenomas in specific anatomical locations, we analyzed the average number of adenomas per colonoscopy in different segments of the colon before and after CADe implementation.

100% CADe use group: The right sided average adenoma per colonoscopy increased significantly from 0.28 pre-CADe to 0.89 post-CADe (RR = 3.22, 95%CI: 2.44-4.25, P < 0.0001).

50%-99% CADe use group: The right sided average adenoma per colonoscopy rate increased from 0.49 to 0.52 but this change did not reach significance (RR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.79-1.44, P = 0.68).

0% CADe use group: No notable improvements in right-sided adenoma detection were observed in this group.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding all colonoscopies performed for diagnostic indications, to isolate the impact of CADe on ADR and related metrics in screening and surveillance procedures alone. This exclusion greatly reduced the number of procedures available for analysis, particularly in endoscopist groups 2 and 3, significantly limiting statistical power.

In this restricted cohort, no statistically significant differences were observed in PDR, ADR, or SSL-DR across any endoscopist group following CADe implementation (Table 3). For example: In the 100% use group, ADR decreased from 78.4% to 70.6% (P = 0.26), and SSL-DR increased from 19.6% to 22.5% (P = 0.73). In the 50%-99% use group, ADR rose marginally from 47.0% to 50.0% (P = 0.86), while SSL-DR remained essentially unchanged (16.4% vs 15.9%, P = 1.00). The 0% use group sample size was too small to support meaningful comparisons.

| CADe use (n) | PDR % (No. of procedures) | ADR % (No. of procedures) | SSL-DR % (No. of procedures) | ||||||

| Pre | Post | P value | Pre | Post | P value | Pre | Post | P value | |

| 100% of time (2) | 93.1 (102) | 89.2 (102) | 0.46 | 78.4 (102) | 70.6 (102) | 0.26 | 19.6 (102) | 22.5 (102) | 0.73 |

| 50%-99% of time (4) | 68.2 (134) | 72.7 (44) | 0.71 | 47.0 (134) | 50 (44) | 0.86 | 16.4 (134) | 15.9 (44) | 1.00 |

| 0% of time (1) | 66.7 (3) | 66.7 (3) | 1.00 | 66.7 (3) | 0 (3) | 0.40 | 33.3 (3) | 33.3 (3) | 1.00 |

A mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression model was performed to evaluate the independent association between CADe availability and adenoma detection, accounting for clustering by individual endoscopist through inclusion of a random intercept. After adjustment for patient age, indication, procedure timing, bowel preparation quality, and total procedure duration, CADe use remained significantly associated with increased adenoma detection (OR = 1.47, 95%CI: 1.07-2.01, P = 0.02), indicating an independent effect of the technology beyond measured procedural and patient-level factors (Table 4).

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| CADe era | 1.47 | 1.07-2.01 | 0.02b |

| Patient age (years) | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.41 |

| Procedure time of day (PM vs AM) | 0.92 | 0.67-1.26 | 0.61 |

| Procedure time (minutes) | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.02b |

| Indication: Surveillance compared to screening | 2.19 | 1.45-3.30 | < 0.001a |

| Indication: Diagnostic compared to screening | 1.53 | 1.08-2.19 | 0.02b |

| BBPS score (total) | 0.97 | 0.88-1.06 | 0.50 |

To assess whether the effect of CADe differed by procedural indication, a multivariate sensitivity analysis was performed stratified into screening, surveillance, and diagnostic colonoscopies. CADe availability did not significantly influence adenoma detection in screening or surveillance procedures; however, in diagnostic colonoscopies, CADe use was independently associated with higher adenoma detection (OR = 1.76, 95%CI: 1.17-2.63, P = 0.006; Table 5).

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Screening | |||

| CADe era | 1.30 | 0.59-2.87 | 0.52 |

| Patient age (years) | 1.02 | 0.99-1.04 | 0.23 |

| Procedure time of day (PM vs AM) | 0.40 | 0.18-0.85 | 0.02 |

| BBPS score (total) | 0.87 | 0.67-1.12 | 0.29 |

| Procedure time | 1.01 | 0.99-1.04 | 0.22 |

| Surveillance | |||

| CADe era | 1.27 | 0.70-2.29 | 0.43 |

| Patient age (years) | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.73 |

| Procedure time of day (PM vs AM) | 1.11 | 0.61-2.01 | 0.72 |

| BBPS score (total) | 1.10 | 0.93-1.32 | 0.32 |

| Procedure time | 1.00 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.74 |

| Diagnostic | |||

| CADe era | 1.76 | 1.17-2.63 | 0.006b |

| Patient age (years) | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.35 |

| Procedure time of day (PM vs AM) | 1.10 | 0.72-1.67 | 0.67 |

| BBPS score (total) | 0.94 | 0.82-1.07 | 0.34 |

| Procedure time | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.08 |

The use of CADe has been found to improve certain colonoscopy quality indicators such as ADR in several RCTs[10,11,17]. Currently, it is not established whether this is reflected in clinical practice, with mixed results emerging from real-world studies.

Promisingly, this retrospective cohort study demonstrated that CADe availability significantly improved ADR from a baseline of 29% in the group of endoscopists who used CADe in the majority (50%-99%) of procedures. In comparison the group of endoscopists who used CADe 100% of the time had no statistically significant change in ADR. This is likely attributable to their already high baseline ADR of 64.2%, which exceeds established quality benchmarks and leaves limited room for measurable improvement. This suggests a ceiling effect, whereby endoscopists with strong baseline performance gain proportionally less from adjunctive technologies. Additional factors may also have contributed to the absence of further ADR improvement despite 100% CADe use, such as greater case complexity (both endoscopists using CADe 100% of time were interventional luminal endoscopists).

Consistent with this, other recent observational studies that found endoscopists with no change in ADR post CADe availability tended to have a high baseline ADR, suggesting that a “ceiling effect” may account for the lack of impro

Although current CRC screening guidelines focus on individuals aged 45-75 years[21], evidence suggests that polyp transformation via the chromosomal instability pathway occurs over an average of 10 years, supporting the inclusion of patients ≥ 40 years for surveillance and hence this age threshold was used for the study[22,23]. The age difference between groups was statistically significant, however, the four-year gap is unlikely to have resulted in a meaningful increase in adenoma or polyp prevalence, as the risk of colorectal neoplasia typically rises over longer timeframes.

In our initial sensitivity analysis, we excluded diagnostic colonoscopies to isolate the effect of CADe on ADR in a screening and surveillance cohort. This greatly reduced the sample size, particularly among endoscopists in groups 2 and 3, limiting statistical power to detect meaningful differences. Within this smaller dataset, no significant changes were observed in ADR following CADe implementation, and the low case numbers made interpretation difficult. We therefore performed a second, more robust sensitivity analysis using mixed-effects logistic regression stratified by indication. In this analysis, CADe did not significantly affect ADR in screening or surveillance procedures but remained independently associated with higher adenoma detection in diagnostic colonoscopies. This may reflect both methodological and clinical factors: Diagnostic procedures comprised most of the cases in this real-world cohort, providing greater statistical power, and they typically involve higher clinical suspicion and lesion prevalence, giving CADe more opportunity to add incre

These limitations reinforce the rationale for our primary analytic approach, which included diagnostic, surveillance and screening colonoscopies. This decision aligns with real-world clinical practice and reflects the design of major CADe studies and guideline recommendations. Moreover, prior evidence has demonstrated that ADR is consistent across both screening and non-screening indications, supporting its use as a valid quality measure irrespective of indication[24]. Including diagnostic procedures allowed us to preserve statistical power, maintain generalizability, and evaluate the performance of CADe in a setting more representative of routine endoscopic practice.

Compared to adenomas, SSLs are more easily missed given their indistinct borders, bland color and flat morphology. In examining SSL-DR as a secondary outcome, there was no statistically significant change in SSL-DR for all three groups regardless of CADe use. This is similar to previous research, such as a 2023 meta-analysis which showed no statistically significant improvement in SSL detection with CADe compared to a clear improvement in adenoma detection[24]. A potential explanation for this may be that most CADe systems are not focused on detecting SSLs, with only a few describing its use in their training dataset[25]. Another possibility is the role that endoscopist discretion may play in interpreting the lesion highlighted by CADe and determining whether to proceed with polypectomy.

Importantly, in the group of endoscopists who used CADe in 100% of cases, the total number of APP significantly increased, effectively doubling detection. Therefore, even when ADR did not further improve due to an already high baseline, CADe still contributed to identifying a greater number of APP. This may reflect subtle quality benefits beyond just ADR, including detection of additional adenomas that may otherwise be missed, identification of smaller or flat lesions, and improved risk stratification to guide interval surveillance colonoscopy. While there was an absolute increase in APP in the 50%-99% CADe-use group (from 1.15 to 1.31), this change was not statistically significant.

The median total procedure time for colonoscopies was longer in the post-CADe era compared to pre-CADe procedures, a difference that was statistically significant. This increase in time may reflect additional time taken to remove the greater number of polyps and adenomas detected with the aid of CADe. However, it may also indicate that the presence of CADe acts as a visual prompt for endoscopists to examine the mucosa carefully, thus improving detection rates. Importantly, our multivariate analysis confirmed that the observed increase in adenoma detection associated with CADe use persisted even after adjusting for procedure duration, as well as other potential confounders including patient age, indication, time of day, and bowel preparation quality. This suggests that the improvement in ADR likely reflects a true additive effect of CADe technology.

Although scopes done for iron-deficiency were more frequent in the post-CADe period, this alone is unlikely to explain the observed improvement in detection. Iron-deficiency anaemia is a heterogeneous indication, and while it may increase the baseline likelihood of finding pathology, it does not uniformly predict higher adenoma yield. As well, our mul

A major strength of this study is that the effects of CADe availability were examined with endoscopists unaware that colonoscopy quality metrics would be assessed and compared. This contrasts with previous RCTs performed where endoscopists were aware of being observed and may have been more vigilant in their procedures. Furthermore, as a real-world study, where CADe use is left to the discretion of endoscopists, these results are more generalizable to clinical practice and may provide practical input to hospital management and heads of units/departments on the value of CADe even though it may not be adopted 100% of the time.

Another useful insight from this study relates to the endoscopist who did not utilise CADe for any procedures during the study period. Having the lowest baseline ADR of the groups, this endoscopist ostensibly would have benefited the most from using CADe. This demonstrates that despite availability and integration into departmental workflow, variation in attitudes and willingness to engage with new technology can significantly influence usage rates. The non-use observed in this case underscores that barriers to CADe uptake are not solely technical, but also practitioner dependent. Understanding these factors will be essential for improving real-world implementation and maximising the potential quality benefits of CADe.

We acknowledge there are several limitations applicable to this study. Various potential confounding procedural fa

Moreover, there was an uneven distribution of procedures pre- and post-CADe among endoscopists, which limits interpretation. In addition, as no endoscopists in this study utilised CADe between 1% and 49% of procedures, we were unable to assess whether use of CADe in the minority of cases had the potential to improve ADR. As well, while a reasonable cohort of patients were examined in this study, there was only a limited number of endoscopists involved.

Withdrawal time was not consistently recorded; as a result, total procedure time was used as a surrogate, which in

Finally, this study included diagnostic as well as screening and surveillance colonoscopies, which may introduce heterogeneity in baseline ADR. Our subsequent sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the effect of CADe was not uniform across indications. While CADe did not significantly change ADR in screening or surveillance procedures, it remained independently associated with higher adenoma detection in diagnostic colonoscopies. This likely reflects the greater prevalence of pathology and higher clinical suspicion in diagnostic procedures, as well as the larger sample size within this subgroup, providing greater statistical power to detect differences. Nevertheless, these findings support a real-world benefit of CADe in improving lesion detection, particularly in diagnostic settings.

In this real-world study, the implementation of CADe was associated with a significant improvement in ADR, even when not being used in all procedures. The ADR improvement was not shown in endoscopists with a high baseline ADR, however in this subgroup there was significant increase in APP. SSL-DR and SPP were not improved with the addition of CADe. CADe was associated with increased total procedure time, however on multivariate analysis, CADe was independently associated with increase ADR. Overall, these findings suggest that CADe holds benefits even without 100% endoscopist use.

| 1. | Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 1362] [Article Influence: 454.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 2. | Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer data in Australia. 2025. [cited 15 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia. |

| 3. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, Levin TR, Quesenberry CP. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1673] [Article Influence: 139.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Shaukat A, Holub J, Pike IM, Pochapin M, Greenwald D, Schmitt C, Eisen G. Benchmarking Adenoma Detection Rates for Colonoscopy: Results From a US-Based Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1946-1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rex DK, Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Day LW, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Ladabaum U, Levin TR, Shaukat A, Achkar JP, Farraye FA, Kane SV, Shaheen NJ. Quality Indicators for Colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:1754-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mehrotra A, Morris M, Gourevitch RA, Carrell DS, Leffler DA, Rose S, Greer JB, Crockett SD, Baer A, Schoen RE. Physician characteristics associated with higher adenoma detection rate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:778-786.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Almadi MA, Sewitch M, Barkun AN, Martel M, Joseph L. Adenoma detection rates decline with increasing procedural hours in an endoscopist's workload. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1714-1723; quiz 1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Facciorusso A, Del Prete V, Buccino RV, Della Valle N, Nacchiero MC, Monica F, Cannizzaro R, Muscatiello N. Comparative Efficacy of Colonoscope Distal Attachment Devices in Increasing Rates of Adenoma Detection: A Network Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1209-1219.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kamba S, Tamai N, Horiuchi H, Matsui H, Kobayashi M, Ego M, Sakamoto T, Fukuda A, Tonouchi A, Shimahara Y, Nishino H, Nishikawa M, Saito Y, Sumiyama K. ID: 3519580 A Multicentre Randomized Controlled Trial To Verify The Reducibility Of Adenoma Miss Rate Of Colonoscopy Assisted With Artificial Intelligence Based Software. Gastroint Endosc. 2021;93:AB195. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Wang P, Liu X, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown JR, Liu P, Zhou C, Lei L, Li L, Guo Z, Lei S, Xiong F, Wang H, Song Y, Pan Y, Zhou G. Effect of a deep-learning computer-aided detection system on adenoma detection during colonoscopy (CADe-DB trial): a double-blind randomised study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:343-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Park DK, Kim EJ, Im JP, Lim H, Lim YJ, Byeon JS, Kim KO, Chung JW, Kim YJ. A prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial on artificial intelligence assisted colonoscopy for enhanced polyp detection. Sci Rep. 2024;14:25453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Soleymanjahi S, Huebner J, Elmansy L, Rajashekar N, Lüdtke N, Paracha R, Thompson R, Grimshaw AA, Foroutan F, Sultan S, Shung DL. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Colonoscopy for Polyp Detection : A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177:1652-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wei MT, Fay S, Yung D, Ladabaum U, Kopylov U. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Colonoscopy in Real-World Clinical Practice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2024;15:e00671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Goetz N, Hanigan K, Cheng RK. Artificial intelligence fails to improve colonoscopy quality: A single centre retrospective cohort study. Artif Intell Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;4:18-26. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Biscaglia G, Cocomazzi F, Gentile M, Loconte I, Mileti A, Paolillo R, Marra A, Castellana S, Mazza T, Di Leo A, Perri F. Real-time, computer-aided, detection-assisted colonoscopy eliminates differences in adenoma detection rate between trainee and experienced endoscopists. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10:E616-E621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gimeno-García AZ, Hernández Negrin D, Hernández A, Nicolás-Pérez D, Rodríguez E, Montesdeoca C, Alarcon O, Romero R, Baute Dorta JL, Cedrés Y, Castillo RD, Jiménez A, Felipe V, Morales D, Ortega J, Reygosa C, Quintero E, Hernández-Guerra M. Usefulness of a novel computer-aided detection system for colorectal neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:528-536.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Samarasena J, Yang D, Berzin TM. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Colon Polyp Diagnosis and Management: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1568-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nehme F, Coronel E, Barringer DA, Romero LG, Shafi MA, Ross WA, Ge PS. Performance and attitudes toward real-time computer-aided polyp detection during colonoscopy in a large tertiary referral center in the United States. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:100-109.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ladabaum U, Shepard J, Weng Y, Desai M, Singer SJ, Mannalithara A. Computer-aided Detection of Polyps Does Not Improve Colonoscopist Performance in a Pragmatic Implementation Trial. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:481-483.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Krist AH, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Owens DK, Pbert L, Silverstein M, Stevermer J, Tseng CW, Wong JB; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 1377] [Article Influence: 275.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vleugels JLA, Hazewinkel Y, Dekker E. Morphological classifications of gastrointestinal lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:359-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, Lieberman D, Levin TR, Robertson DJ, Rex DK; United States Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Colonoscopy Surveillance After Colorectal Cancer Resection: Recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:758-768.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shiha MG, Oka P, Raju SA, David Tai FW, Ching H, Thoufeeq M, Sidhu R, Mcalindon ME, Sanders DS. Artificial intelligence-assisted colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. iGIE. 2023;2:333-343.e8. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zorron Cheng Tao Pu L, Maicas G, Tian Y, Yamamura T, Nakamura M, Suzuki H, Singh G, Rana K, Hirooka Y, Burt AD, Fujishiro M, Carneiro G, Singh R. Computer-aided diagnosis for characterization of colorectal lesions: comprehensive software that includes differentiation of serrated lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:891-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/