Published online Jan 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i4.112635

Revised: November 20, 2025

Accepted: December 25, 2025

Published online: January 28, 2026

Processing time: 174 Days and 10 Hours

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) are pre-malignant tumours of the pancreas with variable malignant potential. Imaging often fails to map the disease extent accurately and guidelines differ on surgical thresholds. Pancreato

Core Tip: In this mini-review, we outline the current understanding of the role pancreatoscopy plays in assisting surgical decision-making for patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. We explore its role in both preoperative decision-making, in determining who should be operate on, and intraoperative decision-making, in deciding what operation to perform. We outline the current methods used to directly visualise the pancreatic duct of patients with suspected or confirmed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and discuss the safety and utility of these procedures.

- Citation: Abusharar M, Barritt C, Mavroeidis VK, Aroori S. Role of pancreatoscopy in the management of suspected and confirmed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(4): 112635

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i4/112635.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i4.112635

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are cystic precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer that originate from the ductal epithelium of the main pancreatic duct or its branches. They are increasingly detected incidentally through high-resolution abdominal imaging[1]. A large meta-analysis of approximately 48860 asymptomatic individuals found that 8% of participants had pancreatic cysts, with detection rates of 2%-3% on computed tomography (CT) and up to 45% on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rising to 50% in autopsy series. Of these lesions, mucinous cysts, including IPMNs, made up around 4.3% overall (95%CI: 2%-10%), although only 0.7% exhibited worrisome features[2]. In older adults, imaging studies report that IPMNs represent 3%-10% of pancreatic cysts, and autopsy series suggest a similar number of 24%-30%, implying that IPMNs likely account for 20%-50% of incidentally discovered pancreatic cysts[2,3].

IPMNs are classified into main duct (MD), branch duct (BD), and mixed-type variants, with MD-IPMN carrying the highest malignant potential. Current guidelines recommend surgical resection of MD-IPMN and mixed-type tumours due to their higher association with high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. In contrast, BD-IPMN may be managed conservatively unless it exhibits “worrisome features” or “high-risk stigmata”[4]. Despite these stratification frameworks, the management of IPMN remains fraught with uncertainty. Long-term follow-up of patients with branchduct IPMN has demonstrated that low-risk lesions can still progress to malignancy. Pergolini et al[5] in 2017 reported an 8% incidence of malignancy over 3-5 years, while surgical series often reveal only low-grade dysplasia on histology, highlighting the dilemma of balancing overtreatment against the risk of under-treatment[5].

The lack of high-fidelity diagnostic tools that can reliably distinguish between benign and malignant lesions remains a significant challenge[1]. Conventional imaging modalities, such as CT, MRI, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provide indirect assessment, and cytological sampling has limited sensitivity. Furthermore, surgical decision-making is often based on features that may not reflect the true pathological extent of the disease. Consequently, there is increasing in

Accurate preoperative characterisation of IPMNs is fundamental for informed management decisions. Cross-sectional imaging, specifically contrast-enhanced CT (pancreatic protocol) and MRI with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), serves as the diagnostic cornerstone[6,7]. CT provides high-resolution anatomical detail, aiding in the measurement of the main pancreatic duct and the identification of enhancing mural nodules or masses. In contrast, MRI/MRCP offers superior soft-tissue contrast, significantly improving sensitivity for detecting ductal communication, mural nodules, internal septations, and subtle cystic structures[6]. Indeed, a comparative review reported MRI’s sensitivity at 97% vs CT’s sensitivity at 81% for detecting key features of IPMN, such as mucinous ductal connections and mural nodules[7]. Additional radiological features, such as internal septations forming the classic “cluster-of-grapes” morphology of multifocal branch-duct IPMN, are also more conspicuously depicted on MRI[8]. Finally, main-duct IPMN is characterised radiologically by diffuse ductal dilation > 10 mm, often accompanied by visible mucin extrusion at the ampulla, with the “fishmouth” papilla sign seen in around 25%-50% of cases[9].

Branch-duct IPMNs appear as cystic lesions in the pancreas that communicate with the duct; a size greater than 3 cm or the presence of a mural nodule on MRI are important red flags for malignancy[4]. Despite their strengths, CT and MRI have limitations in IPMN evaluation. Small (< 5 mm) mural nodules can be missed if they are below the resolution of the imaging[10]. Distinguishing mucin plugs or debris from true solid nodules can be challenging on MRCP[10,11]. More

Other diagnostic approaches have also been explored. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography can demonstrate diffuse dilatation and filling defects caused by mucin, with ability to obtain brush cytology. However, endoscopic retro

Nevertheless, preoperative pancreatoscopy or IDUS via the ampulla remains technically demanding, not widely available, and carries a significant risk of pancreatitis. Pancreatoscopy requires a minimum ductal diameter (typically ≥

The current trend is to collect as much diagnostic information as possible using non-invasive means (CT/MRI) supplemented by EUS-FNA, then proceed to surgery if indicated. The final determination of the extent of disease is often made intraoperatively, relying on examination of the resected specimen. Histopathological assessment of a frozen section of the transection margin can be performed during the operation, to assess for evidence of epithelial dysplasia. If high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma is identified at the margin, further resection, including completion pancreatectomy, is typically recommended where feasible[23]. In the case of low- or intermediate-grade dysplasia, further resection is at the surgeon’s discretion, based on operative findings and patient-specific factors[23,24]. In this context, intraoperative pancreatoscopy (IOP) can play a valuable role by directly visualising the ductal epithelium to detect skip lesions or confirm disease clearance.

POP involves advancing a small-calibre endoscope into the pancreatic duct via the papilla, usually during an ERCP. This allows endoscopists to visualise the lumen of the main pancreatic duct and its major BDs. In the context of IPMN, POP can be used in patients with a dilated MD or significant branch-duct lesions to evaluate the mucosal appearance and to obtain biopsies of suspect areas[21,25]. Characteristic endoscopic findings of IPMN on pancreatoscopy have been described. These include villous or papillary projections, “fish-egg” like clusters of tumours, areas of erythematous or granular mucosa, and abnormal vasculature within the duct wall[26,27]. Per-oral pancreatoscopy, especially when combined with intraductal ultrasonography, reliably detects diffuse villous changes or tumour papillae, features indicative of IPMN involvement[27,28]. The presence of a smooth duct lining typically signifies minimal disease. The technique also facilitates targeted biopsies with forceps passed through the scope under direct visualisation, allowing preoperative histological confirmation of highgrade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma within an IPMN, aiding preoperative decision-making[28].

Multiple studies over the last decade have assessed the diagnostic performance of POP in IPMN. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by de Jong et al[27] pooled data from 25 studies involving pancreatoscopic evaluation of suspected IPMN. In these studies, POP was technically successful in most cases, with high rates of ductal cannulation and adequate visualisation of the target area. The overall diagnostic accuracy of POP for detecting high-grade dysplasia or cancer in IPMN was high across studies. However, the sensitivity and specificity varied between series, depending on the techniques and definitions used. One reason for variability is that some groups rely solely on visual appearance, whereas others combine visual findings with pancreatoscopy-guided biopsy results to diagnose malignancy[27]. When targeted biopsies are feasible, pancreatoscopy can enhance specificity; however, limited tissue sampling may result in false-negative outcomes[26].

In a series by Hara et al[28], POP combined with IDUS achieved 100% sensitivity for detecting main-duct IPMN in a cohort of 60 patients undergoing preoperative evaluation, underscoring its diagnostic potential in expert hands. More recent multicentre and single-centre studies report pancreatoscopic sensitivity ranging from 76% to 95% and specificity between 75% and 100%, reinforcing its role as a valuable complement to cross-sectional imaging[26,29].

By providing a direct assessment of disease extent and severity, pancreatoscopic findings can guide the decision on whether to proceed with surgery and which operation to perform. For example, if POP reveals only focal disease in the head region of the pancreas, a partial resection (e.g., pancreatoduodenectomy) may be planned. In contrast, diffuse MD involvement would indicate the need for a total pancreatectomy (TP). In the systematic review by de Jong et al[27], the authors found that pancreatoscopy findings altered the surgical approach or management in between 13% and 62% of cases, depending on the study. In some reports, nearly all patients had their management influenced by POP results, while in others, only a small fraction did, reflecting differing thresholds for using the information. On average, roughly one-third of patients had changes in surgical strategy attributable to pancreatoscopy[27]. These changes include decisions to extend the planned resection based on more extensive disease mapping, or conversely, to avoid or limit surgery if POP suggests only low-risk pathology. For instance, a French multicentre study reported that POP findings led to a modified surgical plan (more extensive resection) in approximately 30% of patients, due to the identification of multifocal or more extensive IPMN than initially thought[26]. Another series from the United States noted that pancreatoscopy helped confirm benign disease in some patients, allowing them to avoid immediate surgery, in favour of surveillance[30]. These data underscore that pancreatoscopy can provide actionable information beyond what imaging alone offers.

Safety is a crucial consideration when pancreatoscopy is performed via ERCP, given the risks associated with ERCP. The primary complication of POP is post-ERCP pancreatitis, due to manipulation and irrigation of the pancreatic duct. Across studies, the overall adverse event rate of POP in IPMN patients is approximately 10%-15%, primarily attributed to pancreatitis, which is typically mild[27]. The meta-analysis by de Jong et al[27] reported a pooled overall adverse event rate of 12%, with post-ERCP pancreatitis at approximately 10%, and almost all cases were mild, resolving with conservative management. This incidence is higher than that of a standard diagnostic ERCP, likely reflecting the prolonged duct instrumentation and irrigation required for pancreatoscopy. Nonetheless, no procedure-related mortalities were reported, and severe complications were rare. Other potential risks include ductal mucosal injury or infection, but these are uncommon with proper technique[30]. The risk of pancreatitis can be mitigated by use of rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as per standard ERCP protocol. Prophylactic pancreatic stenting can also be utilised in high-risk cases. Given these considerations, pancreatoscopy should be undertaken judiciously and ideally in centres experienced with advanced endoscopy, balancing the information yield against the risk of pancreatitis.

In summary, POP has emerged as a valuable diagnostic adjunct for suspected IPMN. It achieves high technical success and provides direct visual and histological assessment of the pancreatic duct, improving the detection of high-risk disease. Evidence suggests that POP frequently influences management decisions in about one-third of patients overall by better defining disease extent or confirming pathology. The procedure carries a modest risk of pancreatitis, so patient selection is crucial. Currently, POP may be most useful in cases where imaging and EUS have yielded indeterminate results and where confirmation of diffuse vs limited disease would alter surgical planning. As endoscopic technology continues to improve (for example, newer digital pancreatoscopes with enhanced optics and narrow-band imaging), the diagnostic accuracy of pancreatoscopy may increase further. Future prospective studies are warranted to quantify the impact of POP on long-term outcomes, such as reducing the need for unnecessary surgery or improving survival through earlier detection of cancerous changes.

IOP technique: IOP enables direct endoluminal visualisation of the pancreatic ductal epithelium, allowing assessment of mucosal abnormalities and targeted biopsies. IOP is typically performed in patients with suspected or confirmed MD-IPMN, where a decision has already been made to perform pancreatic resection. However, the type and extent of resection may not have been decided, and IOP is performed to aid in the decision-making process.

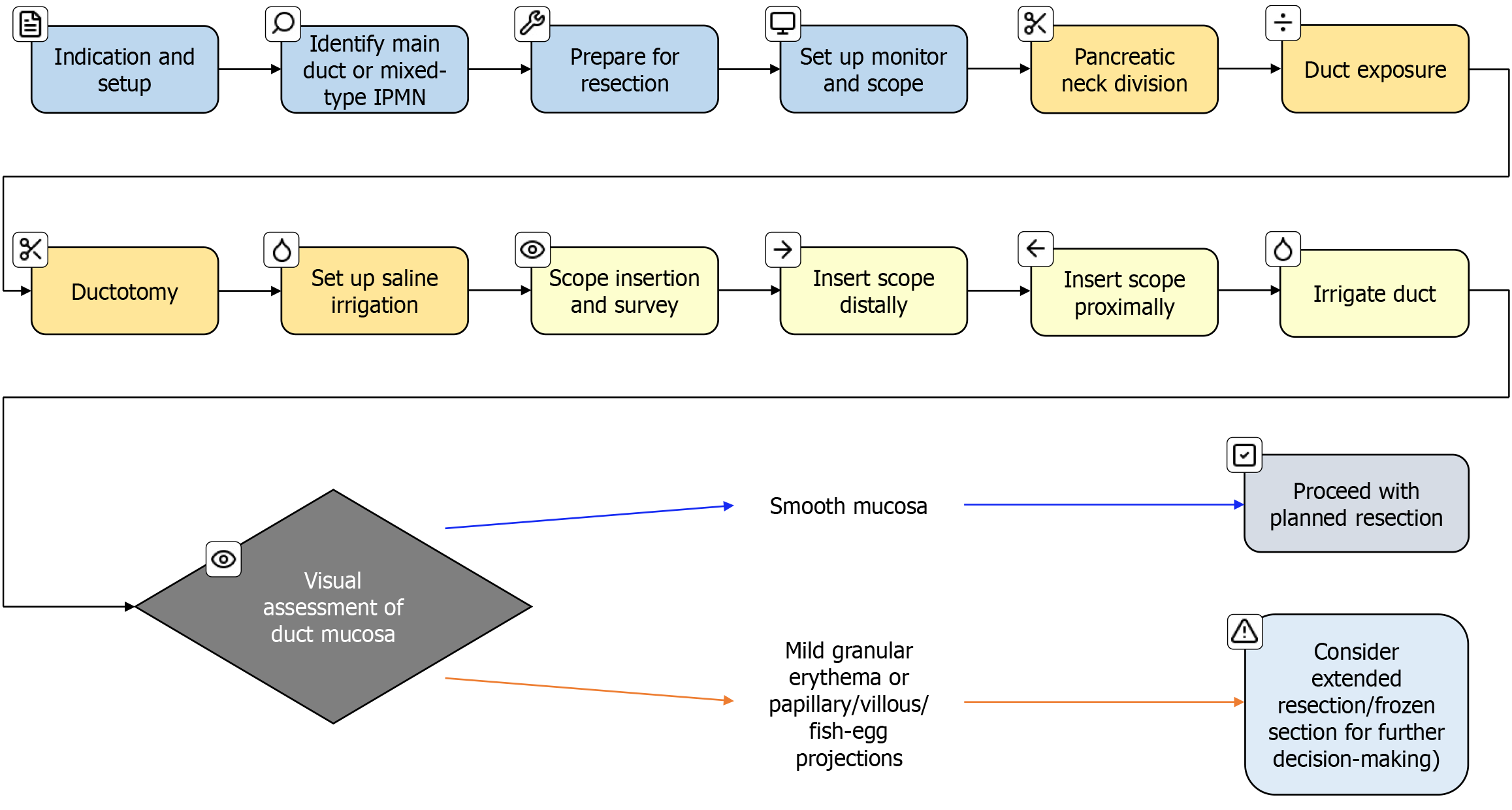

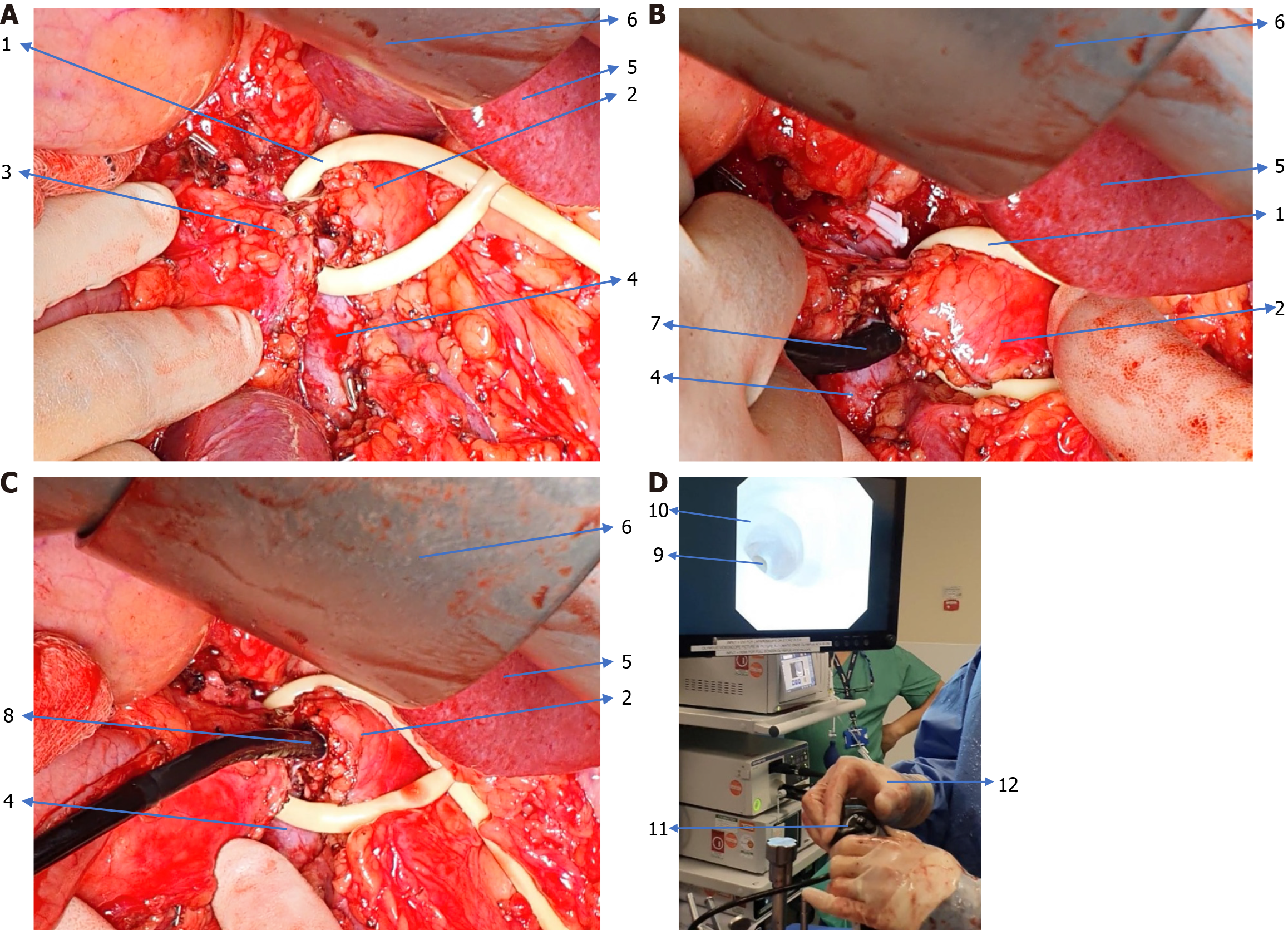

There is no standardised IOP technique described or followed in the literature. Figure 1 shows a workflow diagram of our approach and Figure 2 describes our preferred technique.

Regardless of the type of planned pancreatic resection, IOP involves a partial division of the pancreatic neck to expose the pancreatic duct. A ductotomy is performed either with a knife or scissors. This is followed by the introduction of either a 5 mm or 3 mm choledochoscope into the pancreatic duct. The scope is connected to saline irrigation to get a clear image of the pancreatic duct. Initially, the distal duct inside the body and tail of the pancreas is examined, followed by the examination of the duct inside the head of the pancreas. If a re-usable choledochoscope is not available then a disposable choledochoscope such as the digital SpyGlass DS (Boston Scientific, United States) can be used. In minimally invasive pancreatic resections, IOP can be performed by introducing a SpyGlass or reusable choledochoscope through a standard

Pancreatoscopic IPMN findings: IPMN lesions have characteristic endoscopic appearances. The endoscopic examiner often observes copious, stringy mucin within the duct, necessitating irrigation. Papillary proliferations appear as frond-like or villous projections arising from the duct wall, sometimes forming clusters described as “fish-egg” or “berry-like” due to their multiple bulbous protrusions. These mucosal changes represent the endoluminal view of the villous tumour[28].

High-grade dysplasia in IPMN may manifest as subtle mucosal irregularities, such as focal friability, erythema, or fine granular changes, discernible during pancreatoscopy when carefully examined[29,32]. Normal pancreatic ducts typically exhibit smooth, glistening mucosa on pancreatoscopy, whereas ducts involved in IPMN often display villous or coarse projections aligned with the disease pathology[27].

The Hara classification, introduced by Japanese endoscopists, categorises pancreatoscopic morphology into distinct types; type 1 features a honeycomb-like villous pattern, and type 2 shows fish-egg granular protrusions, each correlating with progressively higher dysplasia grades on histology[28]. In clinical practice, any visible papillary projection is dee

When pancreatoscopy is incorporated into surgery, it becomes a valuable intraoperative adjunct alongside frozen section analysis. A typical sequence during pancreatoduodenectomy for main-duct IPMN involves pancreatic neck transection followed by pancreatoscopic evaluation of the remainder of the duct. If suspicious areas are identified, targeted biopsies or additional margin samples are obtained for frozen section. Based on these assessments, the surgical team may proceed to TP.

The existing literature on pancreatoscopy in the context of IPMN is limited but growing. Most evidence to date has been derived from case series, single-centre cohorts, and early feasibility studies. Limitations include largely retrospective designs, selection bias toward high-volume centres, and variations in procedure techniques. While randomised controlled trials are lacking, several observational studies have demonstrated the diagnostic utility and technical feasibility of both peroral and IOP in assessing ductal extent, guiding surgical margins, and detecting high-grade dysplasia.

A recent scoping review analysed the use of IOP during surgery for IPMN[33]. The review identified three retrospective and one prospective case series (total n = 142 patients); IOP revealed occult skip lesions in about one-third of cases[35-38]. While additional IPMN lesions were identified in 48 of 142 patients (34%) and led to an extended or altered resection in 48 patients (34%)[33]. Similarly, Grewal et al[39] in 2024 reported that across 10 studies (n = 147), IOP detected 46 skip lesions and changed the surgical plan in about 37% of patients. These findings imply that IOP can uncover hidden multifocal disease and significantly impact intraoperative decision-making. Importantly, all studies included in both reviews reported no IOP-related complications[33,39]. Table 1 summarises the key outcomes of studies reporting on the role of IOP in patients with IPMN[35-38].

| Ref. | Study design and patients | Study period | Pre-operative imaging | IPMN types included | IOP approach (open vs MIS) | Additional lesions detected by IOP | Surgical plans change rate | Change of plan based on visual findings or intraductal biopsy | Notable findings |

| Kaneko et al[38], 1998 | Prospective single centre (Japan); 24 patients with IPMN (14 MD, 5 mixed, 5 BD) | 1992-1996 | EUS, ERCP and CT (all patients) | MD, BD, mixed (all types) | Open surgery; ultrathin scope (3 mm) | 10 occult lesions in 24 (42) | 3/24 (12.5%) | Visual findings | First demonstration of IOP; guided extended resection in 3 patients; pathology of skips not all reported |

| Navez et al[37], 2015 | Retrospective single-centre (Belgium); 21 patients (all had dilated main pancreatic duct) | 1991-2014 | CT, MRCP and EUS (all patients) | Mostly MD ± mixed | Open (laparotomy); 3 mm fiberscope with biopsies | 8 occult lesions in 21 (38) | 5/21 (23.8%) | Intraductal biopsies | Biopsies via IOP showed 3 carcinoma in situ and 2 invasive cancers, prompting 3 completion TPs and 2 extended resections; 90% 5-year disease-free survival reported |

| Pucci et al[36], 2014 | Retrospective multi-centre (Italy); 23 patients out of 1016 pancreatic surgeries | 2005-2012 | EUS, ERCP or MRCP | Mostly presumed MD (78%) | Open; choledochoscope | 5 occult lesions in 23 (22) | 5/23 (22%) | Visual findings | IOP altered management in 5 cases (extended resection); one of first multi-centre reports; most patients underwent Whipple’s procedure |

| Yang et al[35], 2023 | Retrospective single-centre (South Korea); 28 patients (all had IOP) | 2007-2020 | CT, MRCP and EUS (all patients) | MD and mixed only | MIS predominant (75% laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy) | 5 occult lesions in 28 (18) | 5/28 (18%) | Visual findings | All cases were pancreatoduodenectomy; IOP performed laparoscopically; extended resection (completion TP) done in those 5 cases; no difference in disease-free survival vs historic controls with frozen section only |

All these studies reinforce that IOP is both feasible and safe, even when applied in a minimally invasive surgery setting. The procedure typically adds a short amount of time (reported additional operative time is around 5-20 minutes for IOP)[32]. It can be performed with standard choledochoscopes or pancreatoscopes, which are available in most advanced hepato-pancreato-biliary centres[36]. Importantly, the findings from IOP complement those from frozen-section pathology; IOP can inspect upstream segments of the duct that are beyond the reach of the surgical margin that is sent for frozen section. In several cases, IOP-visualised lesions within the remnant pancreas are subsequently confirmed as high-grade dysplasia or invasive IPMN on directed biopsy or final pathology, justifying an extended resection intraoperatively[24,37]. In others, IOP has provided reassurance that no significant lesions remain, even if the resection margin shows low-grade dysplasia, thereby avoiding an unnecessary TP. However, a TP may remain appropriate in carefully selected young, fit patients at higher risk of pancreatic cancer, such as in the presence of familial pancreatic cancer[23]. The ability to directly see “skip lesions”, non-contiguous IPMN foci separate from the main tumour, is a unique advantage of pancreatoscopy[38]. Kaneko et al[38] specifically noted multiple small IPMN lesions that had not been identified on preoperative imaging, half of which led them to extend the resection margin further at the time of surgery. This was the sole study to report sensitivity and specificity, both at 100%[38]. In the retrospective series by Navez et al[37] skip lesions identified via IOP led to three patients undergoing completion pancreatectomy during the same operation, likely preventing future recurrence. Without IOP, those residual foci might have been left in situ, potentially progressing to recurrent disease. In all reported series to date, the use of IOP did not appear to compromise patient safety; complication rates and postoperative outcomes were comparable to cases without IOP. Navez et al[37] found no significant difference in overall morbidity or pancreatic fistula rates between patients undergoing IOP and those who did not, and the single postoperative death was unrelated to IOP and was attributed to septic shock in a high-risk patient.

All four studies are from large high volume hepato-pancreato-biliary centres, however, this is unlikely to limit the reproducibility of the studies with the increasing centralisation of pancreatic surgery in many countries. Despite this, the case numbers remain low. There are no consistent criteria across these studies regarding indications for IPMN surgery, while in one of the retrospective studies the indication adopted at that institution changed over the study period[37].

Three of the four studies were retrospective, and one prospective. The retrospective studies did not explicitly state if all patients undergoing IMPN resections were assessed for their suitability of IOP. This presents possibility for selection bias of patients with dilated ducts on preoperative imaging potentially missing occult disease. Those with dilated duct at the time of surgery may have not undergone IOP if not planned preoperatively.

There is also no standardised description of the appearance of IPMN at pancreatoscopy. One of the four studies incorporated frozen section biopsy into IOP to determine the need for an extended resection (Navez et al[37]), while the remaining three relied on visual findings at IOP. In the retrospective series by Yang et al[35] all operations and IOP were performed by the same surgeon, reducing variation in interpretation. Similarly, in the prospective study by Kaneko et al[38] the IOP was interpreted by a single clinician who was also blinded to the patients prior imaging. In the retrospective study by Pucci et al[36] where decision-making relied on visual findings alone, the IOP was performed by the operating surgeon. The lack of a universally accepted set of visual criteria to grade IPMN severity during pancreatoscopy, limits reproducibility and the broader adoption of this technique.

The range in detection rate of additional lesions by IOP across the four studies is large (18%-42%), with the highest IOP detection rate in the oldest study by Kaneko et al[38] and the lowest being in the most recent study by Yang et al[35]. One possible explanation for this variation is the advancement in imaging techniques over that time interval. There was up to a 29-year interval between some study participants across these four studies, while imaging capabilities and detection rates for IMPN have advanced over that time, which may explain why fewer additional lesions are detected on direct visualisation in the more recent patient cohorts[40]. On the presumption that imaging techniques continue to improve, the utility of IOP in detecting additional lesions might decrease, as lesions that previously would have been radiologically undetected become increasingly possible to identify.

Despite promising results reported in these four studies they all have small sample sizes, often with heterogeneity in technique, endoscopic platforms used, and visual classification systems. Moreover, few studies report long-term oncological outcomes, leaving open the question of whether pancreatoscopy improves survival or reduces recurrence.

It becomes obvious that while IOP shows promise in guiding surgical resection in IPMN, the evidence remains limited and of low to moderate quality. The small patient numbers, variable methodology, and lack of standardised outcome reporting, highlight the need for prospective multicentre trials to advance the adoption and incorporation of IOP into future guidelines.

Despite the encouraging results outlined above, pancreatoscopy has not yet been incorporated into routine guidelines for the management of IPMN. Current international guidelines remain cautious regarding pancreatoscopy in the management of IPMN. The 2012 and 2017 Fukuoka guidelines, established by the International Association of Pancreatology, make only a passing reference to pancreatoscopy. They advise against the use of IOP, citing the risk of spillage of mucin, favouring POP as an adjunct in preoperative planning[4,9]. Rather they emphasise radiological findings and cytology to inform interventions[4,9]. Similarly, the American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms, published in 2015, do not mention pancreatoscopy, reflecting the limited data available at the time[41]. The European evidence-based guidelines, published in 2018, provide the only reference to pancreatoscopy within current guidance, stating that it “may be used in selected cases to provide information on the location and extent of MD-IPMN”[24]. However, this comment is accompanied by a caveat regarding the limited quality of evidence and absence of a proven outcome benefit.

These omissions underscore critical limitations in prevailing recommendations. Current IPMN guidelines rely on surrogate markers, such as main pancreatic duct diameter, mural nodules, and negative intraoperative frozen section histology at resection margins, to estimate disease burden. However, these indicators may be insufficient. Discontinuous or skip lesions are missed in approximately 10% of cases despite negative frozen sections[42]. Moreover, imaging features such as nodules and duct dilation are imperfect predictors of malignancy, potentially resulting in incomplete resections and an underestimated risk of malignancy[43].

Pancreatoscopy, by offering direct visualisation of the ductal epithelium and enabling targeted biopsies, can address this diagnostic gap. Studies report that visual features observed during pancreatoscopy, such as villous or fish egg-like mucosal projections, are associated with malignancy and demonstrate high concordance with final histopathology[27].

In a prospective cohort, IOP altered the planned surgical approach in a substantial proportion of IPMN cases, highlighting its potential to improve surgical precision[26]. Nevertheless, guidelines remain silent on when and in whom pancreatoscopy should be used, offering no criteria for case selection, operator experience, or integration into existing diagnostic algorithms.

Real-world practice reflects this uncertainty. A European survey of endoscopists and pancreatic surgeons found that 46% use POP preoperatively for IPMN in selected cases, while over half reported never having used the technique[44]. Among users, the majority employed it to delineate MD involvement, and 71% combined visual assessment with directed biopsies. Importantly, nearly half of these clinicians reported that pancreatoscopy findings changed the surgical plan in up to 40% of cases, supporting its potential clinical impact. Similarly, our recent international survey of pancreatic surgeons (PANSCOPE study, unpublished data, 2024) found that fewer than 20% had ever performed IOP for IPMN. Nonetheless, approximately 75% expressed interest in adopting the technique if high-quality evidence demonstrated a clear benefit.

Barriers to broader adoption remain. These include limited access to advanced endoscopic platforms (such as the SpyGlass DS system), procedural risks including post-procedural pancreatitis or cholangitis, the learning curve associated with image interpretation, and the absence of reimbursement incentives in many healthcare systems. Although pancreatoscopy increases procedure time and involves specialised single-use devices raising cost-effectiveness concerns, some respondents argued that if it leads to more accurate resections with fewer recurrences or reoperations, it may be justifiable from a long-term oncological perspective[44].

In summary, existing guidelines reflect a cautious stance that fails to integrate recent developments in direct intraductal visualisation. While pancreatoscopy remains a niche tool largely confined to high-volume or research-focused centres, its diagnostic and intraoperative utility is increasingly supported by emerging data. Bridging the gap between current evidence and guideline adoption will require prospective studies and consensus on standardised indications. Until then, its use will continue to depend on local expertise, equipment availability, and clinician preference.

The primary advantage of IOP is that it enhances the surgeon’s capacity to assess the pancreatic duct mucosa in real time, beyond what tactile sensation or inspection of the transected duct surface allows. By offering direct endoscopic visualisation, IOP can identify skip lesions of IPMN that would otherwise remain undetected. This enables more precise resections by pinpointing areas harbouring occult high-grade neoplasia, thus potentially reducing the risk of recurrence[32].

Conversely, if the duct mucosa appears pristine beyond a certain point, surgeons may safely preserve more of the pancreas, thereby avoiding unnecessary removal of a functioning gland. In essence, IOP can help tailor the extent of resection to the true microscopic spread of the disease. Another strength is that targeted biopsies can be obtained from suspicious intraductal lesions during IOP. Unlike frozen-section analysis, which examines only a limited ductal margin, intraoperative pancreatoscopic biopsies enable targeted sampling of suspicious lesions, such as small papillary pro

Despite these advantages, pancreatoscopy has clear limitations. IOP requires specialised instruments and endoscopic expertise which are not widely available in all surgical centres. Furthermore, successful scope insertion depends on adequate duct calibre, typically necessitating a main pancreatic duct diameter of at least 4-5 mm for easy advancement[21]. In the largest of the retrospective studies into IOP by Navez et al[37], 86 patients had surgery for IMPN of which only 21 had a MD sufficiently dilated to facilitate complete IOP. In cases of small-duct IPMN or only mild duct dilation, IOP may not be possible. Also, branch-duct IPMNs that do not communicate with the MD cannot be visualised unless the BD is surgically opened. Pancreatoscopy mainly evaluates the MD and larger secondary ducts, so very peripheral disease could be missed. Another limitation is in the interpretation of findings. The interpretation of pancreatoscopic images, particularly subtle changes such as mucosal erythema or flat lesions, remains subjective. There is currently no consensus or standardised classification to define positive findings, which may affect diagnostic consistency[27]. This subjectivity could lead to variability; one surgeon might decide that a specific mucosal irregularity warrants a complete pancreatectomy, whereas another might not. The four studies discussed above report small case numbers over long time periods. The infrequent use of IOP and POP limits the opportunity for surgeons to learn to interpret pancreatoscopic images. The decision to extend a resection or not, based on IOP, is highly consequential. There is the potential for a missed lesion which may progress to become malignant, or the risk of overdiagnosis and unnecessary TP. Clinicians performing other diagnostic endoscopies with similarly consequential outcomes such as colonoscopy for cancer screening would typically perform hundreds of procedures prior to certification. Obtaining biopsies assists clinicians relieving them from depending solely on image interpretation, but the small endoscopic forceps biopsies may have sampling error, and obtaining a result from the pathologist will incur a delay. Furthermore, frozen section of tiny biopsies is challenging, and often, final pathology is needed. Therefore, intraoperative decision-making may end up being made based solely on the endoscopic appearance. There is also the potential for false negatives; pancreatoscopy may miss lesions due to blind spots (e.g., behind a sharp bend in the duct or in smaller side branches). A completely normal pancreatoscopic exam does not exclude the presence of dysplasia in the duct, particularly if the disease is flat.

Thus, surgeons should still consider conventional frozen section analysis and clinical judgement in conjunction with IOP. Another weakness is that current evidence has not shown a clear improvement in long-term outcomes with IOP, partly due to a lack of large studies. While TP might intuitively seem to reduce recurrence risk, retrospective data indicate that partial/segmental pancreatectomy followed by surveillance may yield comparable long-term outcomes. For instance, Hashimoto et al[45] examined a multicentre cohort of 194 patients with multifocal IPMN and found no significant difference in disease-specific or disease-free survival between total and segmental pancreatectomy[45]. Notably, the addition of IOP typically prolongs operative duration by approximately 5-20 minutes, as reported in published series[32]. In a patient already undergoing a lengthy and complex operation, every additional step must be justified. Some surgeons worry that manipulating the pancreatic duct with a scope could cause trauma to the duct epithelium or papilla. However, no such injuries have been documented, although careful technique remains imperative.

IOP has an excellent safety profile; a pilot retrospective study of 46 patients undergoing IOP for main-duct/mixed-type IPMN reported no mortality or procedure-related complications, and the surgical plan was altered in 65% of cases[32]. A recent scoping review of 142 IOP procedures confirmed no IOP-related morbidity, emphasising that duct decompression and gentle handling during surgery mitigate theoretical risks such as duct injury or pancreatitis[33]. In IOP procedures, the ampulla is routinely opened to facilitate ductal irrigation; correspondingly, no study has reported elevated rates of postoperative pancreatitis beyond those expected from standard pancreatectomy[32,33]. Another concern is the in

The financial implications of IOP warrant consideration. The disposable devices used to perform IOP are notoriously expensive; reusable scopes also come with capital and maintenance costs. The economic favourability of IOP hinges on its potential to prevent costly reoperations. If IOP enables surgeons to perform an extended resection at the initial operation, thereby addressing all disease and preventing recurrence, the savings from avoiding subsequent reoperations could offset the initial expenditure on equipment and devices.

Given the substantial costs of pancreatic resection and subsequent hospitalisation, even a modest reduction in residual disease-related recurrence requiring further intervention could make IOP cost-effective, although this requires formal economic evaluation. However, the extra costs of IOP could limit its adoption in resource-limited settings. In the context of limited evidence for clinical effectiveness, centres without established pancreatoscopy services may be reluctant to invest in the required infrastructure.

The collective evidence suggests that pancreatoscopy influences intraoperative surgical strategy in a meaningful subset of cases[32]. In such cases, the influence is usually to extend the resection, for example, by identifying that the IPMN extends further than initially thought, thereby prompting a more extensive resection or TP. In theory, pancreatoscopy could also prevent over-extending resection by confirming the absence of disease beyond a margin, but this is challenging to de

Undergoing a TP has profound life-long consequences for patients. The loss of exocrine function post TP, results in patients developing brittle, insulin-dependent diabetes, rendering patients’ susceptible to dangerous episodes of hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis[47,48]. Advancements in glucose monitoring and insulin pump technology have improved the quality to life for those who have access to them however life-long insulin therapy remains a major change in lifestyle[47,48]. Islet auto-transplantation offers patients undergoing TP the possibility of maintaining endogenous insulin production however it is not widely available and unlikely to be an option for patients undergoing an unplanned TP following IOP findings[47]. The loss of exocrine function following TP gives rise to persistent digestive tract symptoms and malnutrition. Although pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy can mitigate exocrine insufficiency, it can impose a substantial treatment burden for patients. Moreover, enzyme replacement does not fully restore nor

In situations where the anatomical relationship between the pancreatic tail and the splenic vessels necessitates a splenectomy during TP, patients become immunologically compromised for life. Lifelong preventive measures, including vaccinations and prophylactic antibiotics, are essential[47]. Nevertheless, even with these interventions, patients continue to face an increased risk of life-threatening infections.

A TP is significantly detrimental to a patient’s quality and length of life. Although many of the complications can be managed, all these interventions require lifelong adherence to daily treatment routines[47,48].

One must weigh the oncologic benefit vs the impact on length and quality of life when converting a partial to a TP, based on IOP. The surgeon may have removed all the premalignant lesion but with at a substantial cost to the patient's quality of life[47,48], raising the question whether it is always in the patient's best interest[47]. If the skipped lesion was only low-grade IPMN, it might have been sufficient to pursue surveillance only. Thus, there is a risk of overtreatment if pancreatoscopy leads surgeons to resect every abnormality aggressively.

This highlights the need for careful judgment; for instance, if IOP shows a small skip lesion that, on biopsy, is low-grade, one might opt to preserve the pancreas and monitor it rather than perform a TP. Conversely, a skip lesion that looks villous and worrisome should probably be removed. Each patient’s comorbidities and preferences, such as their willingness to accept the implications of TP, must factor into intraoperative decisions in real-time, which can be challenging.

Extending a resection to TP based on IOP carries profound long-term consequences. In the context of limited prospective evidence for clinical benefit, this raises important ethical considerations for counselling and shared decision-making in patients for whom such an approach might be considered.

Undergoing pancreatic resection the extent of which may be modified intraoperatively can increase uncertainty for patients with regard to postoperative function and recovery. Preoperative counselling should therefore address the planned operation, whether pancreatoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy, and whether splenectomy is anticipated. These procedures require careful consideration of both short-term and long-term risks, including postoperative pancreatic fistula with potentially serious sequelae, and the risk of overwhelming sepsis following splenectomy.

For those undergoing patrial pancreatectomy with IOP and the prospect of extension to TP, the patient must also weigh up a different set of, life-altering, and often life-limiting consequences[47]. The European evidence-based guidelines, advice that patients undergoing IPMN resection should always be counselled about the potential re

The primary alternative intraoperative strategy for assessing IPMN extent is the frozen section of margins. Frozen section is highly specific when positive; in the presence of high-grade dysplasia at a margin, it is there, but it can suffer from sampling error[49,50]. A negative margin does not ensure absence of disease in the remnant pancreas, as it samples only a small slice[4]. Pancreatoscopy allows for the examination of a larger surface area of the duct, potentially reducing sampling error[32]. Some centres use IOUS to detect nodules in the remnant pancreas; IOUS is effective at finding discrete pancreatic masses or metastases, but IPMNs frequently do not form well-defined masses. IPMNs spread along the ductal epithelium, often diffusely or as skip lesions, rather than as focal tumours. They can involve the entire MD and extend along it or via skip lesions in nearly 20% of cases. Such superficial or multifocal dysplasia would not appear as a distinct hypoechoic mass on ultrasound. As such, IOUS will only visualise an IPMN if it has produced a bulky nodule or invasive mass. Flat or microscopic spread of dysplasia is simply invisible to ultrasound[12]. Intraoperative cyst fluid analysis is not typically performed, except in research protocols. Thus, IOP is unique in what it offers.

In summary, the strengths of pancreatoscopy lie in enhanced detection of occult disease and improved confidence in resection margins. At the same time, its weaknesses are the need for resources and the subjective nature of the interpretation. Safety appears acceptable. IOP’s influence on strategy is evident in case series, but whether this translates into improved patient outcomes (more cures, fewer recurrences, acceptable trade-off in quality of life) is the key question that remains.

As pancreatoscopy continues to evolve, several developments could enhance its utility and facilitate broader integration into clinical practice. One major avenue is the development of standardised visual classification systems to improve reproducibility and inter-operator agreement. Currently, the interpretation of pancreatoscopic findings remains sub

Another promising area is the use of pancreatoscopy for intraoperative margin assessment, particularly during pancreatoduodenectomy or extended pancreatectomy for multifocal or extensive IPMN. Conventional frozen section analysis may fail to detect microscopic or skip lesions, potentially leading to incomplete resection or unnecessary extension. Pancreatoscopy offers a means of real-time ductal visualisation beyond the transection plane, which could complement histopathological assessment and refine margin strategy. Integrating pancreatoscopic findings into the surgical algorithm could help avoid both under- and over-treatment, particularly in anatomically complex or borderline cases.

Technological advancements may also support the integration of image-enhancement technologies and artificial intelligence. Techniques such as narrow-band imaging, digital chromoendoscopy, or confocal laser endomicroscopy may improve mucosal contrast and help distinguish between low-grade and high-grade dysplasia. Additionally, emerging machine learning algorithms trained on pancreatoscopic image datasets could offer real-time diagnostic support, flag high-risk features and reduce operator dependency. Such adjuncts, though currently experimental, have shown promise in other areas of endoscopic practice and may accelerate the standardisation and diagnostic accuracy of pancreatoscopy in pancreatic surgery.

Finally, prospective clinical trials and health-economic evaluations are essential to define the true impact of pancreatoscopy on patient outcomes. Questions remain regarding its impact on recurrence, survival rates, reoperation rates, and cost-effectiveness. Comparative trials assessing pancreatoscopy-guided surgery vs standard surgical planning will be crucial in determining its role in future guidelines. Collaborative efforts through international surgical and endoscopic networks will be critical to delivering these studies at scale.

In conclusion, pancreatoscopy represents a significant advance in our capability to visualise and manage IPMNs of the pancreas. For suspected IPMN cases, POP provides an additional diagnostic dimension that can confirm the presence of high-risk features and map disease distribution beyond what standard imaging can achieve. For confirmed IPMN at surgery, IOP allows for a final check for residual lesions, enabling surgeons to tailor the extent of resection to each patient’s disease. The evidence so far, drawn from modest-sized series, demonstrates that pancreatoscopy is safe and often impacts management, detecting occult IPMN in approximately 30% of patients and prompting changes in surgical plans in roughly 20%-30% of cases. However, given the paucity of data, current guidelines have appropriately been cautious, and pancreatoscopy is not yet a routine standard of care. As more data emerge, ideally from prospective multi-centre studies, we anticipate that the precise indications for pancreatoscopy will be better defined. If future data confirm that pancreatoscopy leads to improved long-term outcomes (such as reducing the rate of IPMN recurrence or avoiding unnecessary total pancreatectomies), it may become an integral part of IPMN management algorithms. Until then, pancreatoscopy should be considered on a case-by-case basis in specialised centres, particularly for patients in whom an incremental diagnostic or intraoperative insight could change management. The ultimate goal is to optimise treatment for IPMN patients, intervening aggressively enough to prevent progression to pancreatic cancer, yet sparing patients from the morbidity of overly aggressive surgery when it is not needed, and determining when it is warranted. Pancreatoscopy, as a tool to see the unseen within the pancreatic ducts, has the potential to help strike this delicate balance.

| 1. | Mavroeidis VK, Russell TB, Clark J, Adebayo D, Bowles M, Briggs C, Denson J, Aroori S. Pancreatoduodenectomy for suspected malignancy: nonmalignant histology confers increased risk of serious morbidity. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2023;105:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zerboni G, Signoretti M, Crippa S, Falconi M, Arcidiacono PG, Capurso G. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Prevalence of incidentally detected pancreatic cystic lesions in asymptomatic individuals. Pancreatology. 2019;19:2-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, Berlanstein B, Siegelman SS, Kawamoto S, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Hruban RH. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 724] [Cited by in RCA: 672] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Tanaka M, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, Jang JY, Levy P, Ohtsuka T, Salvia R, Shimizu Y, Tada M, Wolfgang CL. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 868] [Cited by in RCA: 1241] [Article Influence: 137.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Pergolini I, Sahora K, Ferrone CR, Morales-Oyarvide V, Wolpin BM, Mucci LA, Brugge WR, Mino-Kenudson M, Patino M, Sahani DV, Warshaw AL, Lillemoe KD, Fernández-Del Castillo C. Long-term Risk of Pancreatic Malignancy in Patients With Branch Duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm in a Referral Center. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1284-1294.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quingalahua E, Al-Hawary MM, Machicado JD. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions (PCLs). Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Canakis A, Lee LS. State-of-the-Art Update of Pancreatic Cysts. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:1573-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Morana G, Ciet P, Venturini S. Cystic pancreatic lesions: MR imaging findings and management. Insights Imaging. 2021;12:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, Shimizu M, Wolfgang CL, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1714] [Cited by in RCA: 1647] [Article Influence: 117.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pedrosa I, Boparai D. Imaging considerations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2:324-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Brugge WR, Hahn PF. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Paini M, Crippa S, Scopelliti F, Baldoni A, Manzoni A, Belfiori G, Partelli S, Falconi M. Extent of Surgery and Implications of Transection Margin Status after Resection of IPMNs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:269803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kin T, Shimizu Y, Hijioka S, Hara K, Katanuma A, Nakamura M, Yamada R, Itoi T, Ueki T, Masamune A, Hirono S, Koshita S, Hanada K, Kamata K, Yanagisawa A, Takeyama Y. A comparative study between computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasound in the detection of a mural nodule in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm -Multicenter observational study in Japan. Pancreatology. 2023;23:550-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Suzuki R, Thosani N, Annangi S, Guha S, Bhutani MS. Diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA-based cytology distinguishing malignant and benign IPMNs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2014;14:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lisotti A, Napoleon B, Facciorusso A, Cominardi A, Crinò SF, Brighi N, Gincul R, Kitano M, Yamashita Y, Marchegiani G, Fusaroli P. Contrast-enhanced EUS for the characterization of mural nodules within pancreatic cystic neoplasms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:881-889.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fujita M, Itoi T, Ikeuchi N, Sofuni A, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Kamada K, Umeda J, Tanaka R, Tonozuka R, Honjo M, Mukai S, Moriyasu F. Effectiveness of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for detecting mural nodules in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas and for making therapeutic decisions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:377-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cotton PB, Garrow DA, Gallagher J, Romagnuolo J. Risk factors for complications after ERCP: a multivariate analysis of 11,497 procedures over 12 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:80-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Shergill AK, Dominitz JA. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Sun B, Hu B. The role of intraductal ultrasonography in pancreatobiliary diseases. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | De Luca L, Repici A, Koçollari A, Auriemma F, Bianchetti M, Mangiavillano B. Pancreatoscopy: An update. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;11:22-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Adler DG. Fundamentals of ERCP, series #5. Pract Gastroenterol. 2023;. |

| 22. | Vehviläinen S, Fagerström N, Valente R, Seppänen H, Udd M, Lindström O, Mustonen H, Swahn F, Arnelo U, Kylänpää L. Single-operator peroral pancreatoscopy in the preoperative diagnostics of suspected main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: efficacy and novel insights on complications. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:7431-7443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oikonomou D, Bhogal RH, Mavroeidis VK. Central pancreatectomy: An uncommon but potentially optimal choice of pancreatic resection. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2025;24:119-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1144] [Cited by in RCA: 979] [Article Influence: 122.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Han S, Raijman I, Machicado JD, Edmundowicz SA, Shah RJ. Per Oral Pancreatoscopy Identification of Main-duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms and Concomitant Pancreatic Duct Stones: Not Mutually Exclusive. Pancreas. 2019;48:792-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Arnelo U, Siiki A, Swahn F, Segersvärd R, Enochsson L, del Chiaro M, Lundell L, Verbeke CS, Löhr JM. Single-operator pancreatoscopy is helpful in the evaluation of suspected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN). Pancreatology. 2014;14:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de Jong DM, Stassen PMC, Groot Koerkamp B, Ellrichmann M, Karagyozov PI, Anderloni A, Kylänpää L, Webster GJM, van Driel LMJW, Bruno MJ, de Jonge PJF; European Cholangioscopy study group. The role of pancreatoscopy in the diagnostic work-up of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2023;55:25-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hara T, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Tsuyuguchi T, Kondo F, Kato K, Asano T, Saisho H. Diagnosis and patient management of intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor of the pancreas by using peroral pancreatoscopy and intraductal ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:34-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nagayoshi Y, Aso T, Ohtsuka T, Kono H, Ideno N, Igarashi H, Takahata S, Oda Y, Ito T, Tanaka M. Peroral pancreatoscopy using the SpyGlass system for the assessment of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:410-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shah RJ. Innovations in Intraductal Endoscopy: Cholangioscopy and Pancreatoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25:779-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hedjoudje A, Dokmak S, Cros J, Sauvanet A, Prat F. Laparoscopic intraoperative pancreatoscopy for main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms assessment. VideoGIE. 2023;8:27-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Arnelo U, Valente R, Scandavini CM, Halimi A, Mucelli RMP, Rangelova E, Svensson J, Schulick RD, Torphy RJ, Fagerström N, Moro CF, Vujasinovic M, Matthias Löhr J, Del Chiaro M. Intraoperative pancreatoscopy can improve the detection of skip lesions during surgery for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia: A pilot study. Pancreatology. 2023;23:704-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ciprani D, Frampton A, Amar H, Oppong K, Pandanaboyana S, Aroori S. The role of intraoperative pancreatoscopy in the surgical management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a systematic scoping review. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:9043-9051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sato S, Miyazawa K, Shiobara M, Wakatsuki K, Ogasawara T, Suda K, Aida T, Miyoshi T, Yoshioka S, Yamazaki K. [Intraoperative Pancreatoscopy to Assess the Resection Margin in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm-A Case Report]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2019;46:2521-2523. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Yang HY, Kang I, Hwang HK, Lee WJ, Kang CM. Intraoperative pancreatoscopy in pancreaticoduodenectomy for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: Application to the laparoscopic approach. Asian J Surg. 2023;46:166-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pucci MJ, Johnson CM, Punja VP, Siddiqui AA, Lopez K, Winter JM, Lavu H, Yeo CJ. Intraoperative pancreatoscopy: a valuable tool for pancreatic surgeons? J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1100-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Navez J, Hubert C, Gigot JF, Borbath I, Annet L, Sempoux C, Lannoy V, Deprez P, Jabbour N. Impact of Intraoperative Pancreatoscopy with Intraductal Biopsies on Surgical Management of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:982-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kaneko T, Nakao A, Nomoto S, Furukawa T, Hirooka Y, Nakashima N, Nagasaka T. Intraoperative pancreatoscopy with the ultrathin pancreatoscope for mucin-producing tumors of the pancreas. Arch Surg. 1998;133:263-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Grewal M, Habib JR, Paluszek O, Cohen SM, Wolfgang CL, Javed AA. The Role of Intraoperative Pancreatoscopy in the Surgical Management of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: A Scoping Review. Pancreas. 2024;53:e280-e287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Park J, Park J, Lee YS, Jung K, Jung IH, Lee JC, Hwang JH, Kim J. Increased incidence of indeterminate pancreatic cysts and changes of management pattern: Evidence from nationwide data. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2023;22:294-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, Moayyedi P; Clinical Guidelines Committee; American Gastroenterology Association. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819-22; quize12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 629] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Sauvanet A, Couvelard A, Belghiti J. Role of frozen section assessment for intraductal papillary and mucinous tumor of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Tashiro Y, Kachi M, Hashimoto T, Takeyama N, Ueda Y, Munechika J, Ohgiya Y. Understanding intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm from pathogenesis to risk assessment: a pictorial review based on the kyoto guidelines. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Stassen PMC, de Jonge PJF, Webster GJM, Ellrichmann M, Dormann AJ, Udd M, Bruno MJ, Cennamo V; European Cholangioscopy Group; and the German Spyglass User Group. Clinical practice patterns in indirect peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy: outcome of a European survey. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1704-E1711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 45. | Hashimoto D, Satoi S, Yamamoto T, Yamaki S, Ishida M, Hirooka S, Shibata N, Boku S, Ikeura T, Sekimoto M. Long-term outcomes of patients with multifocal intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm following pancreatectomy. Pancreatology. 2022;22:1046-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Sahora K, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge W, Thayer SP, Ferrone CR, Sahani D, Pitman MB, Warshaw AL, Lillemoe KD, Fernandez-del Castillo CF. Branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: does cyst size change the tip of the scale? A critical analysis of the revised international consensus guidelines in a large single-institutional series. Ann Surg. 2013;258:466-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kotsifa E, Mavroeidis VK. Status post total pancreatectomy. In: Bennett G, Goodall E, editors. The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability. Cham: Springer, 2025: 1-15. |

| 48. | Mavroeidis VK, Knapton J, Saffioti F, Morganstein DL. Pancreatic surgery and tertiary pancreatitis services warrant provision for support from a specialist diabetes team. World J Diabetes. 2024;15:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Furukawa T, Hatori T, Fujita I, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi M, Ohike N, Morohoshi T, Egawa S, Unno M, Takao S, Osako M, Yonezawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, Lauwers GY, Yamaguchi H, Ban S, Shimizu M. Prognostic relevance of morphological types of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Gut. 2011;60:509-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bhardwaj N, Dennison AR, Maddern GJ, Garcea G. Management implications of resection margin histology in patients undergoing resection for IPMN: A meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2016;16:309-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/