Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.115527

Revised: November 10, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 89 Days and 21.2 Hours

Clinically, patients with nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding (NVGB) are prone to thromboembolic events, but the specific risk remains unclear.

To identify risk factors and evaluate the performance of five machine learning (ML) models in predicting the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB.

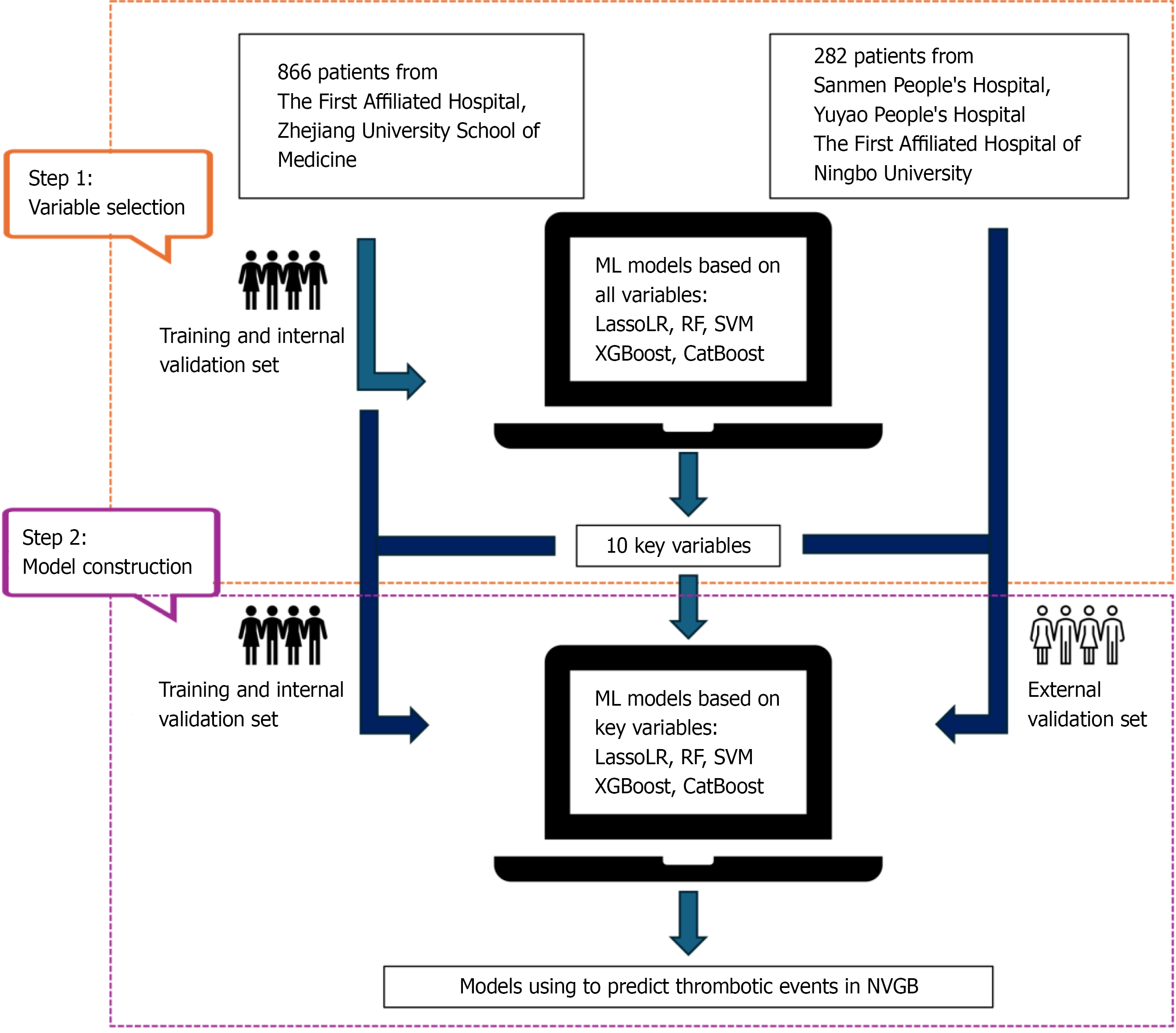

This retrospective cohort study enrolled 866 patients from a tertiary hospital for model training and internal validation, and 282 patients from three other tertiary hospitals for external validation. These data were used to develop five ML models to predict the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB. After initial feature selection by training ML models, ten variables were selected to construct simplified ML models. Model perfor

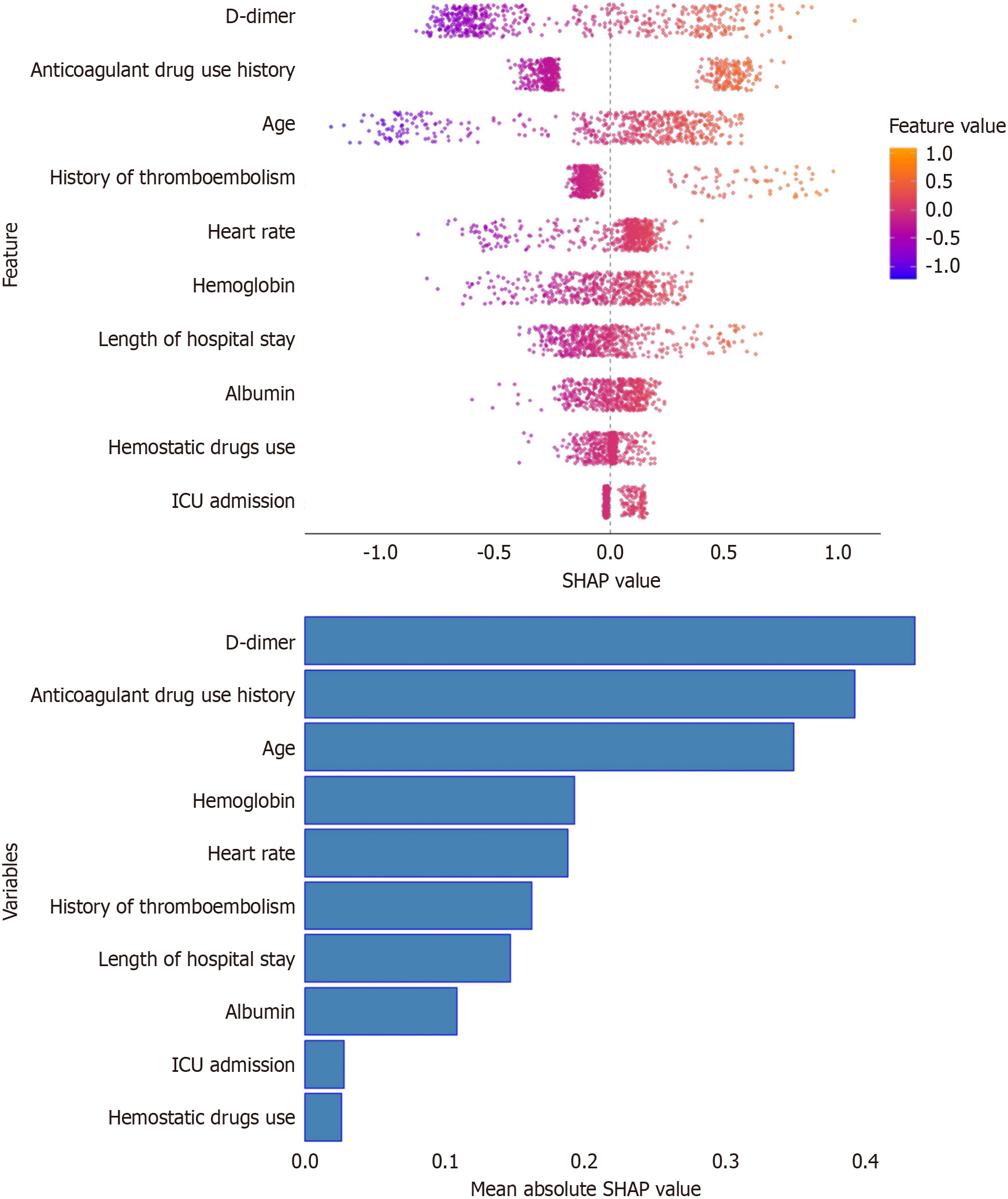

During hospitalization, the incidence of thromboembolic events was 25.61% in patients with NVGB. The categorical boosting (CatBoost) algorithm which combined variable importance and SHapley Additive exPlanations values identified 10 independent predictors of thromboembolic events: (1) History of anticoagulant drug use; (2) D-dimer level; (3) Age; (4) History of thromboembolism; (5) Length of hospital stays; (6) Intensive care unit (ICU) admission; (7) Hemoglobin level; (8) Use of hemostatic drugs; (9) Heart rate; and (10) Serum albumin level. We developed five simplified ML prediction models (L1 regularized logistic regression, random forest, support vector machines, extreme gradient boosting, and CatBoost) based on the above 10 predictors, which achieved area under the receiver operating characteristic curves of 0.805, 0.804, 0.806, 0.746, and 0.815 in external validation, respectively. The performance of all five ML models significantly exceeded that of D-dimer alone in both internal and external validation. The CatBoost model demonstrated good calibration and accuracy, achieving the lowest Brier score of 0.131 and 0.110 in the internal and external validation set, respectively. Of the five models, the CatBoost model was considered the preferred choice in clinical settings.

The findings in this study enable effective and timely preventive interventions for high-risk patients, and help avoid unnecessary monitoring in low-risk patients.

Core Tip: This multicenter study developed and validated five machine learning models to predict thromboembolic risk in patients with nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Using ten key clinical variables identified by categorical boosting and SHapley Additive exPlanations analysis, all models showed superior predictive performance to D-dimer alone, with the categorical boosting model achieving the best calibration and accuracy. These models can help clinicians identify high-risk patients for early intervention while reducing unnecessary monitoring in low-risk individuals.

- Citation: Lu C, Cheng HY, Zhu RK, Zhou YD, Sun KF, Xu L, Sang JZ, Chen JE, Yu CH, Qin YL, Li L. Application of machine learning models in predicting the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(3): 115527

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i3/115527.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.115527

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, the global annual hospitalization rate for nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding (NVGB) is approximately 160 per 10000 individuals. Approximately 13% of patients are readmitted within 30 days after discharge, with a higher incidence in developing countries. Due to factors such as advanced age, hemodynamic instability, and underlying conditions, the overall mortality rate ranges from 2% to 5%[1].

Due to prolonged bed rest and altered hemodynamics in hospitalized patients, these patients face not only life-threatening conditions but also an increased risk of thromboembolic events, with a reported incidence of 1%-1.9%[2]. Chemical deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis is usually avoided in patients with NVGB, and thromboembolic events can occur in any location, including DVT, pulmonary embolism, cerebral infarction, and myocardial infarction, each leading to distinct clinical outcomes[3]. Previous studies have shown that any medical or surgical condition that leads to thromboembolic events will significantly increase the economic burden[4]. Therefore, early prevention and accurate prediction of thromboembolic events are important. Known risk factors include advanced age, active cancer, recent surgery, and trauma, all of which warrant close clinical attention[5]. D-dimer is widely used as a predictive biomarker, and normal levels can be used to rule out thromboembolic events[6]. Although elevated D-dimer levels are independently associated with thromboembolic events across various disease states, they do not necessarily indicate a high-risk thromboembolic event[7]. Other predictive indicators also have inherent limitations, and to date, no scoring system based solely on clinical and demographic parameters has demonstrated sufficient accuracy. For severe complications such as cerebral infarction, which can result in disability, earlier predictive models are essential to reduce incidence. Although some models based on clinical data have been developed to predict thromboembolic events, they still have notable limitations[8].

Artificial intelligence, particularly recent advances in machine learning (ML) and deep learning techniques, has been increasingly applied to disease risk prediction[9]. ML models have shown great potential in enabling timely clinical interventions and improving patient outcomes[10]. However, for high-risk populations such as those with NVGB, no studies to date have specifically addressed how to effectively predict early diagnosis and guide timely intervention. With the growing adoption of ML algorithms, this study aims to explore the feasibility of predicting and validating the occurrence of thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB based on clinical parameters and demographic information using various ML models, thereby providing guidance for early intervention.

This study was a retrospective cohort analysis. We identified patients diagnosed with NVGB between January 2022 and May 2024 at the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. The cohort was randomly divided into a training set and an internal validation set at a 7:3 ratio using simple random sampling.

In this study, NVGB was defined as the presence of visible hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia, accompanied by a significant decrease in hemoglobin levels, with esophagogastric varices excluded based on clinical history and endoscopic examination. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Meeting the diagnostic criteria for gastrointestinal bleeding; (2) Age ≥ 14 years; (3) Identification of the cause of gastrointestinal bleeding via esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, enteroscopy, or surgery; and (4) If thromboembolic events were suspected, confirmation (or exclusion) through at least one imaging examination, such as thoracoabdominal computed tomography angiography, vascular ultrasound, or head magnetic resonance imaging. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Gastrointestinal bleeding caused by portal hyper

This study retrospectively collected data across four major categories, comprising 42 variables. These included: (1) Demographic data (gender, age, history of smoking and drinking, anticoagulant use, comorbidities, history of throm

To assess the robustness and generalizability of the model, an external validation cohort was included from three additional tertiary hospitals: (1) Sanmen People's Hospital of Zhejiang Province; (2) Yuyao People's Hospital; and (3) the First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University. Patients enrolled between January 2023 and December 2024 were selected based on the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as described above. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. 2024-1142), with a waiver of informed consent.

This study included a total of 42 initial variables based on patients' clinical characteristics. Five ML algorithms including L1 regularized logistic regression (LassoLR), random forest (RF), support vector machines (SVM), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and categorical boosting (CatBoost) were employed for initial feature selection. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was used to comprehensively evaluate the models, quantifying their overall discriminative ability through AUC calculation. Subsequently, based on the variable importance and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) feature importance analysis of the optimal model, the top 10 variables were selected to construct a simplified prediction model using five ML algorithms. To optimize the models' performance and minimize the risk of overfitting, five-fold cross-validation was employed to ensure the reliability of the evaluation results. The predictive performance of the model was assessed through accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score and AUC in the validation dataset. Additionally, decision curve analysis (DCA) and calibration curve were employed to evaluate model performance.

In this study, categorical variables are presented as n (%), while continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 23.0, Chicago, IL, United States) software. χ2 tests were applied for categorical variables and Student's t-tests were used for continuous variables. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a probability level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The DeLong test was used to compare the AUC between different models. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to test the goodness of fit of the model. P > 0.05 was considered indicative of good calibration. The Brier score was employed to evaluate both calibration and accuracy in probabilistic predictions. All analyses of ML models were conducted using the R programming language (version 4.0.2; R foundation for statistical computing). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 1148 patients were included in this study, of whom 294 (25.61%) experienced thromboembolic events, including 72 cases of acute cerebral infarction, 4 cases of pulmonary embolism, 196 cases of DVT, and 22 cases of mesenteric vein thrombosis. Patients were stratified into two groups based on the presence of thromboembolic events. Baseline characteristics of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. Eight hundred and 66 patients were allocated to the training and internal validation sets in a 7:3 ratio, while 282 patients were assigned to an independent external validation set (Figure 1). During the training phase, five ML algorithms using 42 variables were developed to predict thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB. Of these algorithms, the CatBoost algorithm achieved the highest AUC value and was therefore considered the most reliable for feature extraction (Supplementary Table 1). Finally, based on variable im

| Variable | Thromboembolism group (n = 294) | Non-thromboembolism group (n = 854) | P value |

| Age (years) | 73.10 ± 11.55 | 64.85 ± 16.97 | < 0.001 |

| Gender (male) (%) | 64.07 | 69.56 | 0.088 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 83.21 ± 15.18 | 86.92 ± 18.87 | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 80.15 ± 27.47 | 90.01 ± 30.61 | < 0.01 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3306 ± 6.62 | 34.91 ± 9.87 | 0.003 |

| Intensive care unit admission (%) | 22.37 | 10.77 | < 0.001 |

| History of anticoagulant drug use (%) | 58.64 | 25.41 | < 0.001 |

| D-dimer level (μg/L) | 4177.46 ± 8129.90 | 2114.73 ± 6339.46 | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 12.90 ± 9.52 | 8.57 ± 6.88 | < 0.001 |

| Use of hemostatic drugs (%) | 10.17 | 11.82 | 0.04 |

| Thromboembolism history (%) | 35.25 | 10.42 | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 23.19 ± 50.04 | 23.55 ± 64.62 | 0.931 |

| Creatinine (μmoI/L) | 121.59 ± 123.56 | 115.05 ± 144.02 | 0.486 |

| International normalized ratio | 5.57 ± 6.62 | 1.17 ± 0.64 | 0.044 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 14.03 ± 9.73 | 13.56 ± 6.97 | 0.376 |

| History of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use (%) | 15.93 | 17.68 | 0.493 |

| Shock (%) | 10.17 | 10.77 | 0.772 |

| Red cell distribution width (%) | 15.56 ± 2.99 | 15.09 ± 5.04 | 0.13 |

| Education (%)1 | 9.52 | 15.69 | 0.09 |

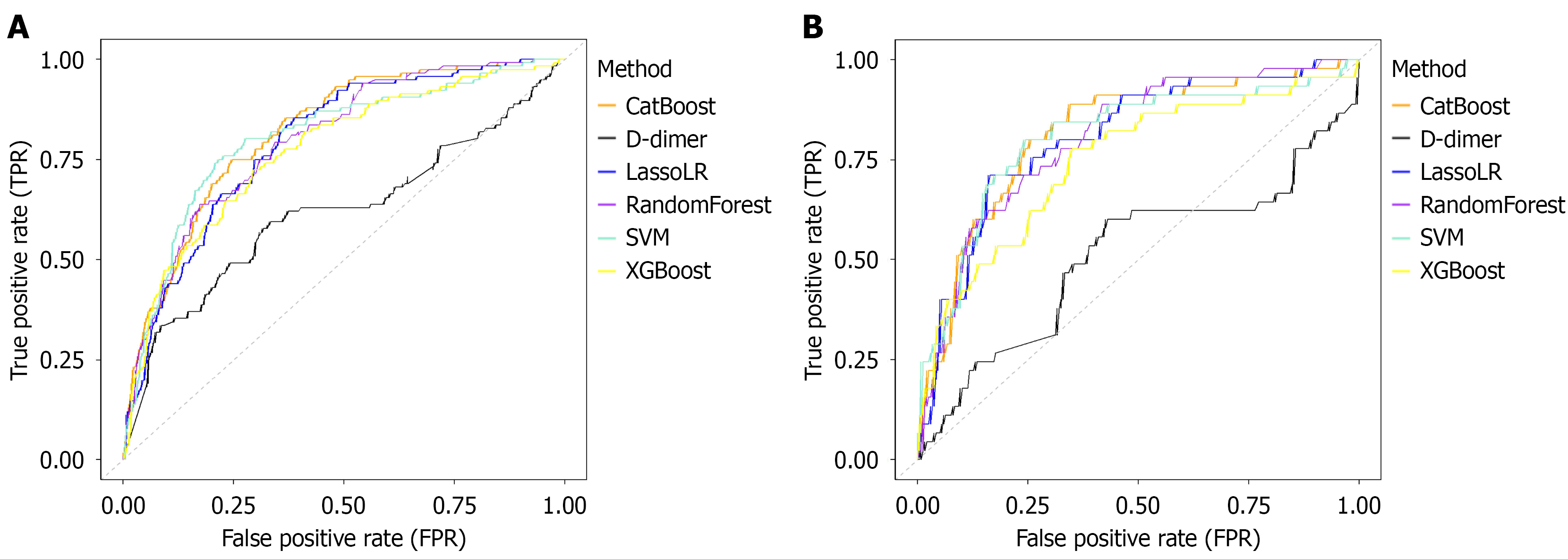

In the internal validation sets, the performance of the five ML models and univariate D-dimer are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2A. The AUC values of the five ML models were as follows: (1) CatBoost (0.818, 95%CI: 0.777-0.859); (2) SVM (0.804, 95%CI: 0.757-0.851); (3) LassoLR (0.793, 95%CI: 0.750-0.837); (4) RF (0.798, 95%CI: 0.757-0.842); and (5) XGBoost (0.772, 95%CI: 0.723-0.821). Of these, the AUC value of CatBoost was significantly better than that of RF and XGBoost (P = 0.0386 and P = 0.009), and the AUC value of RF was significantly better than that of XGBoost (P = 0.0348), while there were no statistically significant differences in AUC between the other ML models (P > 0.05). The cut-off value for D-dimer identified by the receiver operating characteristic curve in the validation cohort was 558.5. For practical use, the predicted probability of D-dimer was normalized to a probability value between 0 and 1 by the Sigmoid function. Importantly, all the ML models outperformed the D-dimer level (AUC = 0.618, 95%CI: 0.552-0.683) (all P < 0.001). CatBoost demonstrated the highest accuracy (0.754, 95%CI: 0.716-0.789). Additionally, the five ML models exhibited sensitivity values ranging from 69% to 80.2% vs 62.1% (95%CI: 0.530-0.704) for the D-dimer assay. Similarly, the specificity of the five ML models ranged from 67.5% to 75.5%, while the specificity of D-dimer was 62.1% (95%CI: 0.574-0.666). Overall, all five ML models outperformed D-dimer in predicting thromboembolic events in the validation cohort.

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve | P value |

| L1 regularized logistic regression | 0.736 (0.697-0.771) | 0.43 (0.362-0.501) | 0.716 (0.628-0.79) | 0.741 (0.698-0.781) | 0.537 | 0.793 (0.750-0.837) | < 0.01 |

| Support vector machines | 0.701 (0.661-0.738) | 0.401 (0.340-0.465) | 0.802 (0.72-0.864) | 0.673 (0.627-0.716) | 0.534 | 0.804 (0.757-0.851) | < 0.01 |

| Categorical boosting | 0.754 (0.716-0.789) | 0.455 (0.386-0.526) | 0.75 (0.664-0.82) | 0.755 (0.712-0.794) | 0.567 | 0.818 (0.777-0.859) | < 0.01 |

| Random forest | 0.678 (0.638-0.716) | 0.38 (0.321-0.443) | 0.793 (0.711-0.857) | 0.647 (0.6-0.691) | 0.514 | 0.798 (0.755-0.842) | < 0.01 |

| Extreme gradient boosting | 0.71 (0.67-0.746) | 0.402 (0.338-0.47) | 0.724 (0.637-0.797) | 0.706 (0.661-0.747) | 0.517 | 0.772 (0.723-0.821) | < 0.01 |

| D-dimer | 0.621 (0.579-0.661) | 0.309 (0.253-0.371) | 0.621 (0.530-0.704) | 0.621 (0.574-0.666) | 0.413 | 0.618 (0.552-0.683) | - |

In the external validation sets, the performance and advantages of the various ML models and univariate D-dimer are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2B. The AUC values of the five ML models were as follows: (1) CatBoost (0.815, 95%CI: 0.746-0.885); (2) SVM (0.806, 95%CI: 0.727-0.884); (3) RF (0.804, 95%CI: 0.736-0.872); (4) LassoLR (0.805, 95%CI: 0.735-0.875); and (5) XGBoost (0.746, 95%CI: 0.661-0.831). The AUC values of CatBoost and RF were significantly higher than that of XGBoost (P = 0.0081 and P = 0.0140, respectively). There were no statistically significant differences in AUC values between the other ML models (P > 0.05). However, all of the ML models demonstrated significant advantages over D-dimer (0.51, 95%CI: 0.403-0.617) (all P < 0.001). CatBoost demonstrated the best accuracy (0.826, 95%CI: 0.778-0.866). The ML models achieved sensitivities ranging from 74.3% to 86.9% vs 35.6% for the D-dimer assay (95%CI: 0.232-0.502). Notably, the specificity of the five ML models ranged from 74.3% to 86.9%, while the diagnostic specificity of D-dimer was 80.6% (95%CI: 0.751-0.851). Nevertheless, the above five models outperformed D-dimer in discrimination following comprehensive evaluation of all indices.

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve | P value |

| L1 regularized logistic regression | 0.78 (0.728-0.825) | 0.395 (0.296-0.504) | 0.711 (0.566-0.823) | 0.793 (0.737-0.84) | 0.508 | 0.805 (0.735-0.875) | < 0.01 |

| Support vector machines | 0.77 (0.717-0.815) | 0.389 (0.295-0.492) | 0.778 (0.637-0.875) | 0.768 (0.71-0.817) | 0.519 | 0.806 (0.727-0.884) | < 0.01 |

| Categorical boosting | 0.826 (0.778-0.866) | 0.466 (0.343-0.592) | 0.6 (0.455-0.73) | 0.869 (0.82-0.906) | 0.524 | 0.815 (0.746-0.885) | < 0.01 |

| Random forest | 0.738 (0.683-0.785) | 0.344 (0.255-0.445) | 0.711 (0.566-0.823) | 0.743 (0.683-0.794) | 0.464 | 0.804 (0.736-0.872) | < 0.01 |

| Extreme gradient boosting | 0.727 (0.672-0.776) | 0.318 (0.23-0.421) | 0.622 (0.476-0.749) | 0.747 (0.688-0.798) | 0.421 | 0.746 (0.661-0.831) | < 0.01 |

| D-dimer | 0.734 (0.68-0.782) | 0.258 (0.166-0.379) | 0.356 (0.232-0.502) | 0.806 (0.751-0.851) | 0.299 | 0.51 (0.403-0.617) | - |

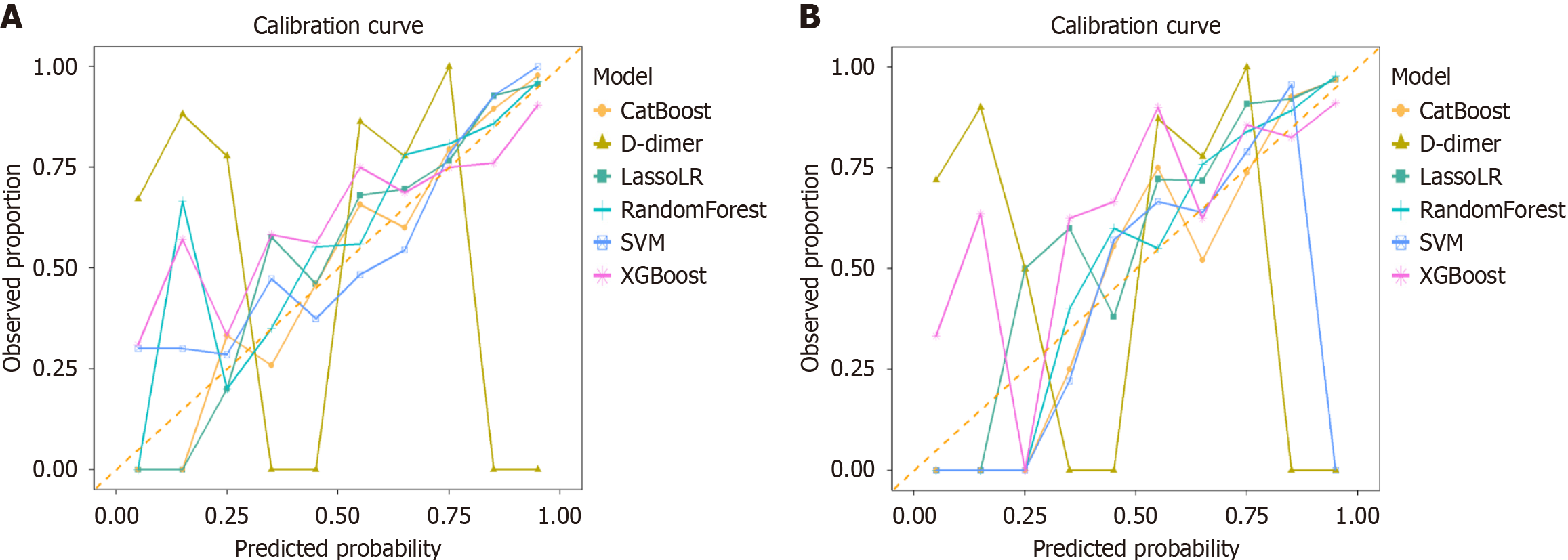

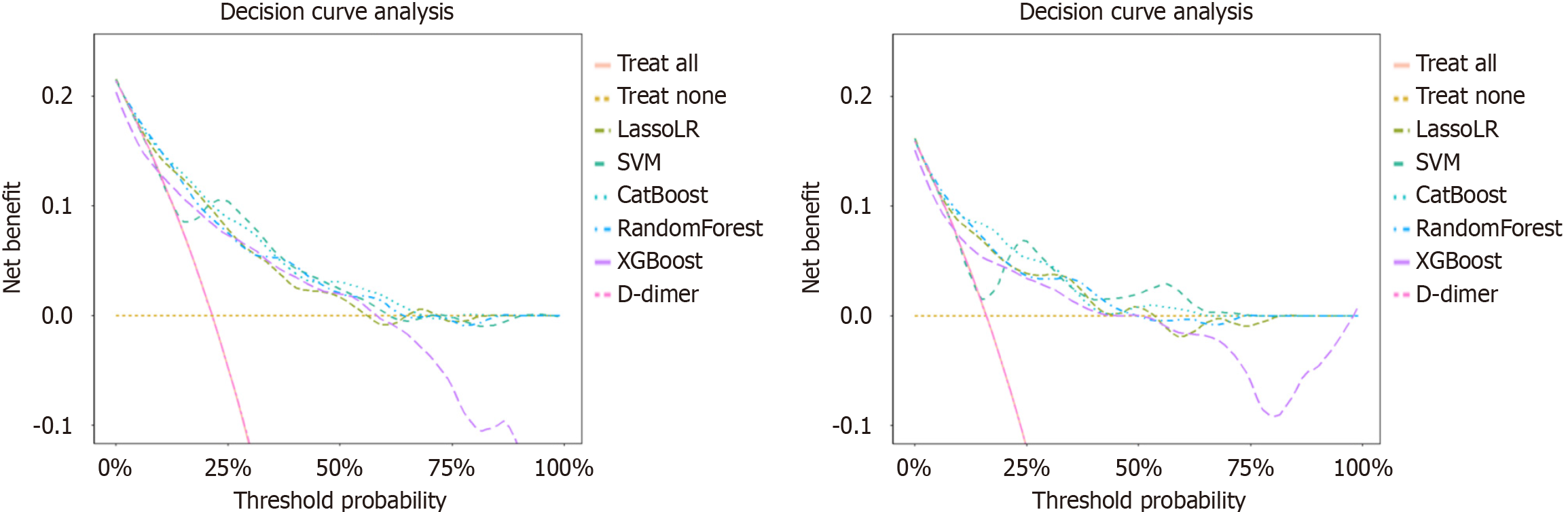

Calibration Curve and DCA were used to assess calibration and clinical applicability, respectively (Figures 3 and 4). The calibration curve of CatBoost, LassoLR and RF for predicting thromboembolic events showed good performance, as confirmed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (all P > 0.05) across validation cohorts. The CatBoost model demonstrated good calibration and accuracy, achieving the lowest Brier score of 0.131 and 0.110 in the internal and external validation set, respectively. Compared to D-dimer, several ML models, particularly CatBoost, exhibited superior calibration, meaning CatBoost more accurately reflected the true risk of thromboembolic events across different predicted probabilities. This provides greater clinical value in decision-making. The results of the DCA showed that compared with D-dimer, all ML models demonstrated higher net benefits across most threshold probability ranges, particularly between approximately 10% and 50%, indicating their greater utility in accurately identifying patients who require clinical intervention.

To enhance the interpretability of CatBoost, the SHAP summary plot was employed to demonstrate the mean SHAP values and the influence of input features on the model's output (Figure 5). The 10 important features were ranked as follows: D-dimer, history of anticoagulant use, age, hemoglobin level, heart rate, history of thromboembolism, length of stays, albumin level, ICU admission, and hemostatic drug use. As expected, D-dimer and history of anticoagulant use were the most influential predictors. Moreover, the magnitude of the mean SHAP value associated with age and hemoglobin indicates a notable influence on the risk of thromboembolic events, suggesting that particular attention should be paid to these high-risk factors in patients with NVGB. To further illustrate the model's prediction process, two representative patients classified by CatBoost as positive and negative were randomly selected. Combined with SHAP analysis, the model's decision-making process was visually demonstrated. The arrows represent the impact of each factor on the prediction, with blue and red arrows indicating decreased (blue) or increased (orange) thromboembolic risk, respectively. In the negative patient, the SHAP score (-0.643) fell below the baseline (0), whereas in the positive patient, the SHAP score (1.79) was above baseline (0) (Supplementary Figure 2).

To date, there is no reliable method to predict the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB, and a review of the literature revealed that no previous studies have addressed this issue. In this cohort study of over 1000 individuals, the incidence of thromboembolic events was 25.61%. By applying various advanced ML models, we were able to predict the risk of thromboembolism and enable early intervention. Among the five well-performing models, CatBoost showed good discrimination and calibration with an AUC of 0.815 (95%CI: 0.746-0.885) and a Brier score of 0.110. Due to its interpretability and traceability of variable effect analysis, CatBoost emerges as the preferred choice in clinical settings. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare different ML models to predict future thromboembolic events among patients with NVGB. Importantly, compared with D-dimer, which is widely used in clinical practice to monitor thromboembolism, all ML models demonstrated a clear advantage.

This study screened a large number of clinical features, including demographic information, laboratory results, endoscopic findings, and clinical characteristics. However, using all of these parameters in ML models posed a dilemma: Some features with weak relevance may not contribute to accurate predictions and could also create challenges in clinical practice. In this study, we initially incorporated all variables into the ML models, and then applied variable importance and SHAP values based on the CatBoost model to identify the most valuable features for the final model construction. Using this approach, we can more effectively focus on key variables in clinical applications. Feature importance analysis of the final CatBoost model using SHAP revealed that several thromboembolism-related variables had a substantial influence on the predicted probability of thromboembolic events. Taking D-dimer and the history of anticoagulant use as examples, these variables had a positive impact on the probability of thromboembolism, and may be used to assess circulatory stability in high-risk cohorts in order to take timely anticoagulant measures to prevent the occurrence of thromboembolic events. Similarly, a history of thromboembolic events and advanced age were identified as high-risk factors, supporting early clinical intervention. These findings are consistent with previous literature[12]. Another important finding was that in our study, the ML model identified the use of hemostatic agents as a significant factor associated with thromboembolic events, which contrasted with previous literature. For example, a meta-analysis by Murao et al[13] suggested that antifibrinolytic agents do not appear to increase the risk of thromboembolic events in bleeding patients. In contrast, blood pressure, which did not rank among the top 10 features, appeared to be the least important, possibly due to the common presence of significant intravascular volume depletion in patients with NVGB. Likewise, certain factors considered clinically as high-risk indicators, such as platelet count, may not be reflected in the ML model, while other commonly considered factors like age and hemoglobin levels are quantitatively represented in the model. This highlights a key advantage of ML models over clinical judgment – the ability to objectively evaluate and weigh the contribution of each variable, potentially revealing patterns that may be overlooked by clinicians. This novel finding may offer new insights for clinical decision-making. The ranking results of the feature variable importance confirmed that clinically significant parameters in clinical records can be used to predict thromboembolic events, and the model we established successfully captured these key variables.

ML models have already been applied in the risk assessment of thromboembolic events. For example, Sheng et al[14] successfully developed risk prediction models for thromboembolic events at hospital admission using multiple ML models. Franco-Moreno et al[15] concluded that ML-based prediction models have good predictive performance for thromboembolic events in cancer patients through a meta-analysis. The present study focused on predicting throm

Among the models tested, CatBoost demonstrated the best performance and was considered an advanced ML model. It can directly handle categorical features without the need for complex preprocessing using a method called statistical encoding to convert categorical variables into numerical values, effectively reducing overfitting. This finding was particularly valuable in clinical practice, as it not only confirmed the robustness of the models but also underscored their potential to enhance decision-making and risk stratification in real-world settings. As the frequency of hematological and imaging examinations varies across different centers and regions, and excessive or unnecessary testing can increase the burden on patients, establishing a reliable ML model would allow for more targeted monitoring of key indicators in patients at high risk of thromboembolic events associated with NGVB. For example, high-risk patients could undergo more frequent follow-up assessments, with preventive measures such as sequential compression devices applied to reduce the risk of thromboembolism. When their indicators shift to a low-risk range, the frequency of follow-ups can be reduced, enabling more efficient patient management. More importantly, ML models can assist clinicians in weighing the risks and benefits of imaging studies involving intravenous contrast, potentially helping to prevent patient harm. For instance, when evaluating an NVGB patient with renal insufficiency for a contrast-enhanced study, clinicians can use ML models to stratify risk and assess the necessity of contrast. This type of high-stakes, clinically meaningful decision support is exactly where ML models can offer the greatest value.

Recent studies have explored the application of ML models for thromboembolic risk prediction in various clinical contexts, including thoracic trauma, orthopedic surgery, and malignancy[17,18]. In addition, a large-scale study based on electronic health records used logistic regression, balanced RF, and neural network models to predict 30-day VTE readmissions, showing robust performance (AUCs around 0.80)[19]. Compared with these studies, our research focused on a distinct and clinically relevant population (patients with NVGB), who face a unique balance between bleeding and thrombosis risk. Unlike prior work limited to single disease categories, our models integrated multidimensional variables encompassing clinical, laboratory, and treatment-related factors, allowing a more comprehensive assessment of thrombotic risk. Furthermore, we developed and externally validated five ML models. Importantly, our study included external validation across multiple tertiary hospitals, whereas several previous studies were single-center or lacked independent validation. These distinctions emphasize the novelty and generalizability of our approach and suggest that ML-based prediction in NVGB patients may extend the application of artificial intelligence-driven thrombosis risk assessment to a new clinical domain.

This study has several strengths. For example, it was the first study to use ML models to predict thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB. We conducted comparative validation to assess the reliability among the models and to evaluate the differences between each ML model and the D-dimer indicator. Moreover, the model was developed using data from a single center and tested with data from multiple centers, effectively demonstrating its clinical applicability. Furthermore, we elaborated on the potential clinical applications of our ML model within the hospital workflow. Specifically, this model could be integrated into the hospital information system or electronic medical record platform to automatically calculate an individualized thrombotic risk score at key clinical time points, such as upon hospital admission, during disease progression, or prior to invasive procedures. The real-time output of the model could assist clinicians in identifying patients at high risk for thromboembolic events and prompt timely preventive measures, such as intensified monitoring, early diagnostic testing, or adjustment of anticoagulation strategies. In this way, the model may serve as a clinical decision-support tool to facilitate early intervention and improve patient outcomes.

However, there were limitations in this study that need to be overcome in the future. Firstly, although this was a multicenter population-based study, it was essentially retrospective in nature. We explicitly acknowledge that the current study lacks prospective, real-world verification, and we plan to conduct future prospective, multicenter studies to evaluate the feasibility, robustness, and clinical utility of the proposed ML model in real clinical settings. Such studies will be essential to determine whether the model can meaningfully assist clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes. Secondly, this study analyzed a large amount of clinical and demographic data for correlation and applied it to ML models based on datasets provided by the participating centers. However, it is debatable whether there were other overlooked variables that could further improve the model’s performance. Thirdly, among the patients with gas

Based on simple clinical parameters and demographic information, we developed ML models that can accurately predict the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with NVGB. Furthermore, all ML models demonstrated significantly superior predictive performance compared to the traditional D-dimer marker. Based on model characteristics, Catboost may have the best clinical applicability. This model has the potential to support more cost-effective clinical monitoring programs by identifying high-risk individuals, while also avoiding unnecessary surveillance for patients at very low risk. The application of ML models based on basic patient data for risk stratification shows promising potential and warrants further evaluation.

| 1. | Wolf S, Barco S, Di Nisio M, Mahan CE, Christodoulou KC, Ter Haar S, Konstantinides S, Kucher N, Klok FA, Cannegieter SC, Valerio L. Epidemiology of deep vein thrombosis. Vasa. 2024;53:298-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guijarro R, San Roman C, Arcelus JI, Montes-Santiago J, Gómez-Huelgas R, Gallardo P, Monreal M. Bleeding and venous thromboembolism arising in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. Findings from the Spanish national discharge database. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Taeuber I, Weibel S, Herrmann E, Neef V, Schlesinger T, Kranke P, Messroghli L, Zacharowski K, Choorapoikayil S, Meybohm P. Association of Intravenous Tranexamic Acid With Thromboembolic Events and Mortality: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:e210884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Danilatou V, Dimopoulos D, Kostoulas T, Douketis J. Machine Learning-Based Predictive Models for Patients with Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review. Thromb Haemost. 2024;124:1040-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Olaf M, Cooney R. Deep Venous Thrombosis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:743-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, Rodger MA. Venous thromboembolism. Lancet. 2021;398:64-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 89.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Halaby R, Popma CJ, Cohen A, Chi G, Zacarkim MR, Romero G, Goldhaber SZ, Hull R, Hernandez A, Mentz R, Harrington R, Lip G, Peacock F, Welker J, Martin-Loeches I, Daaboul Y, Korjian S, Gibson CM. D-Dimer elevation and adverse outcomes. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang J, Liao F, Tang J, Shu X. Development of a model for predicting acute cerebral infarction induced by non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2023;235:107992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Berre C, Sandborn WJ, Aridhi S, Devignes MD, Fournier L, Smaïl-Tabbone M, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Application of Artificial Intelligence to Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:76-94.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 59.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | Anghele AD, Marina V, Dragomir L, Moscu CA, Anghele M, Anghel C. Predicting Deep Venous Thrombosis Using Artificial Intelligence: A Clinical Data Approach. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024;11:1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kate V, Sureshkumar S, Gurushankari B, Kalayarasan R. Acute Upper Non-variceal and Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:932-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang W, Cui Y, Wu J, Chen Y, Wang R, An J, Zhang Y. Incidence and risk factors of venous thromboembolism in patients with acute Leukemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk Res. 2025;153:107694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Murao S, Nakata H, Roberts I, Yamakawa K. Effect of tranexamic acid on thrombotic events and seizures in bleeding patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2021;25:380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sheng W, Wang X, Xu W, Hao Z, Ma H, Zhang S. Development and validation of machine learning models for venous thromboembolism risk assessment at admission: a retrospective study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1198526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Franco-Moreno A, Madroñal-Cerezo E, Muñoz-Rivas N, Torres-Macho J, Ruiz-Giardín JM, Ancos-Aracil CL. Prediction of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With Cancer Using Machine Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2023;7:e2300060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Olson JD. D-dimer: An Overview of Hemostasis and Fibrinolysis, Assays, and Clinical Applications. Adv Clin Chem. 2015;69:1-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liu K, Qian D, Zhang D, Jin Z; China Chest Injury Research Society (CCIRS), Yang Y, Zhao Y. A risk prediction model for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with thoracic trauma: a machine learning, national multicenter retrospective study. World J Emerg Surg. 2025;20:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang B, Qin Y, Jiu L, Qin C, Wang J, Zhao H. A study on the risk prediction model for venous thromboembolism in orthopedic inpatients based on machine learning. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1574546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park JI, Kim D, Lee JA, Zheng K, Amin A. Personalized Risk Prediction for 30-Day Readmissions With Venous Thromboembolism Using Machine Learning. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021;53:278-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/