Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.115264

Revised: November 19, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 96 Days and 0.6 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, non-specific inflammatory bowel disease. The gut microbiome undergoes significant changes in UC. Fatigue is a highly preva

To assess the gut microbiota and metabolomic characteristics of patients with UC with fatigue (HUCF).

A total of 120 participants were recruited and divided into four groups (n = 30 per group) based on the diagnosis of UC and Fatigue Scale-14 scores: HUCF, UC without fatigue (HUCN), healthy with fatigue (HHF), and healthy without fatigue (HHN). Fresh stool samples were collected for 16S rRNA sequencing and un

Metabolomic analysis revealed significant differences among the four groups (principal component ana

Patients with HUCF exhibit a distinct gut microbial structure and metabolomic profile. The pro-inflammatory metabolite TX and the genus Anaerococcus are uniquely enriched in patients with HUCF, suggesting their potential roles in the development of HUCF. These findings provide novel insights and a theoretical basis for improving the clinical management of HUCF.

Core Tip: The relationship between disease severity and gut microbes and metabolites in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) with fatigue remains unclear. To investigate this relationship, we collected fresh stool samples from patients with UC with/without fatigue and healthy individuals with/without fatigue for 16S rRNA sequencing and untargeted metabolomic analysis. Results revealed the gut microbial and metabolomic characteristics of patients with UC with fatigue (HUCF). Patients with HUCF exhibited a distinct gut microbial structure and metabolomic profile. Metabolomic analysis revealed differential expression of metabolites such as linoleoyl ethanolamide, arachidonoyl ethanolamide, glycocholic acid, and thromboxane. Patients with HUCF showed a high relative abundance of Anaerococcus, a beneficial genus.

- Citation: Liu ZX, Liu XY, Tan WW, Zhang WB, Zhang YL, Zheng L, Dai YC. Characteristics of gut microbiota and metabolites in patients with ulcerative colitis with fatigue. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(3): 115264

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i3/115264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.115264

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic non-specific inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and mucopurulent bloody stools[1]. Although the pathogenesis of UC remains unclear, recent studies have indicated that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in the development of IBD[2]. Fatigue is a common symptom of UC, negatively affecting the quality of life of patients[3]. A Chinese cross-sectional study reported that the prevalence of fatigue among patients with UC was as high as 61.8%[4].

Fatigue is defined as a debilitating and persistent sense of exhaustion disproportionate to physical or mental exertion, which impacts daily life and is not alleviated by rest[5]. Studies have shown that 40%-48% of patients with UC in remission and 72%-86% of those with active UC experience fatigue[6]. However, owing to its subjective nature, fatigue is often overlooked in clinical practice, leading to frustration among patients who lack professional support[7]. Clinically, fatigue is observed during both active disease and remission in patients with UC, and overexertion can lead to relapse in patients in remission. Therefore, addressing fatigue can positively affect the clinical management of UC. Fatigue is considered an important predictor of work and activity impairment in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases[8-10]. Although fatigue is a common symptom of various acute and chronic diseases and is primarily related to sleep[11], mood[12], immunity[13], and pro-inflammatory cytokine release[14]. Numerous studies have investigated the role of gut microbes and metabolites in the development of fatigue using metabolomic and sequencing technologies[15-17]. Clinical studies have validated that probiotic supplementation can alleviate fatigue induced by psychological stress or exercise in athletes[18]. Similarly, murine studies have shown that Astragalus-Codonopsis and propolis ethanol extract can mitigate exercise-induced fatigue by modulating gut microbes and metabolites[19,20].

Existing primary treatments for UC include aminosalicylates for baseline treatment, corticosteroids for acute and moderate-to-severe cases (not for long-term maintenance), immunosuppressants, and biologics[21]. Although these drugs can alleviate intestinal inflammation and symptoms such as bloody stools and diarrhea, they have limited efficacy in reducing fatigue. Clinical studies have shown that patients with UC experience fatigue for a markedly long duration after biological therapy, with 61% of the patients sustaining fatigue for 1 year[22]. This long-term treatment not only imposes a substantial economic burden on patients and their families but also increases national healthcare expenditures. The prevalence of fatigue symptoms positively correlated with healthcare resource utilization[23,24]. In the United States, IBD imposes a substantial economic burden, with annual medical costs exceeding 25 billion USD[25]. Given the progressive increase in the global prevalence of UC and associated annual medical costs, developing effective treatment strategies for UC is necessary[26].

Patients with UC or fatigue show significant changes in the composition of gut microbiota. However, studies focusing on gut microbes and metabolites in patients with UC with fatigue (HUCF) remain limited. In this study, we used untargeted metabolomic analysis and 16S rRNA sequencing to assess the distribution of gut microbes and metabolites in patients with HUCF, identify key gut microbes and metabolites or metabolic pathways, and elucidate the mechanisms through which gut microbes and metabolites contribute to HUCF. The findings provide novel insights and a theoretical foundation for improving the clinical treatment of HUCF.

Participants were recruited from Shanghai Traditional Chinese Medicine-Integrated Hospital and Longhua Hospital from March 2024 to December 2024. The study cohort comprised four populations: Patients with HUCF, patients with UC without fatigue (HUCN), healthy with fatigue (HHF), and healthy without fatigue (HHN; control). A total of 30 participants were included in each group. UC was diagnosed based on the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis (2023, Xi'an) established by the IBD Group of the Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. The non-UC groups consisted of healthy individuals without gastrointestinal diseases and with normal physical examination indicators. A Fatigue Scale-14 (FS-14) score of ≥ 7 indicated the presence of fatigue. Clinical data, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), FS-14 scores, and Mayo scores, were recorded. Stool samples were collected for untargeted meta

All participants were asked to collect a 10-g stool sample from different parts of their morning stool using a sterile sampling spoon and place it in a sterile container. The samples were stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

A total of 50-mg of each stool sample was homogenized with grinding beads and 400 μL of an extraction buffer through low-temperature grinding. The sample was centrifuged, and the supernatant was analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Thermo Fisher UHPLC-Orbitrap Exploris 480). Raw data were subjected to baseline filtering and processing using Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation, United States). Metabolites were identified by comparing the data matrix against the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB; http://www.hmdb.ca/), Metlin database (https://metlin.scripps.edu/), and a custom database known as Majorbio.

After the extraction and quality-control analysis (using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer) of fecal microbial DNA, PCR was performed to amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rDNA. Purified amplicons were used to prepare sequencing libraries. DADA2-derived amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were used for taxonomic classification, α- and β-diversity analyses, and functional annotation of bacterial genes using PICRUSt2 (version 2.2.0).

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 26.0). Continuous variables that followed a normal distribution with homogeneity of variances were compared among the four groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Com

A total of 120 participants were enrolled and divided into the HUCF, HUCN, HHF, and HHN groups, with 30 participants in each group. No significant differences in age, sex, or BMI were observed among the four groups (P > 0.05). However, the differences in FS-14 and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) fatigue scores among the four groups were statistically significant (FS-14 scores: F = 63.795, P < 0.05; TCM fatigue scores: F = 23.505, P < 0.05), confirming the validity of grouping. Furthermore, we compared the clinical characteristics of the two UC groups (HUCF group vs HUCN group). The χ2 test revealed no significant differences in disease stage, extent of lesions, or Mayo scores between the two groups (P > 0.05), indicating the comparability of baseline data However, the HUCF group contained a higher proportion of patients with active disease [6.82% (25/44) vs 43.18% (19/44)], those with severe disease [88.89% (8/9) vs 11.11% (1/9)], and those with pan-colonic involvement [57.90% (11/19) vs 42.10% (8/19)] than to the HUCN group (Table 1).

| Item | HUCF group (n = 30) | HUCN group (n = 30) | HHF group (n = 30) | HHN group (n = 30) | P value |

| Age (year) | 45.10 ± 12.48 | 47.43 ± 13.70 | 44.00 ± 15.10 | 48.77 ± 13.67 | 0.533 |

| Gender (M/F) | 15/15 | 12/18 | 22/8 | 14/16 | 0.055 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.81 ± 1.21 | 22.56 ± 0.67 | 22.27 ± 0.80 | 23.60 ± 0.78 | 0.753 |

| FS-14 score | 8.89 ± 0.37 | 2.07 ± 0.47 | 7.33 ± 0.39 | 2.00 ± 0.58 | 0.000 |

| TCM fatigue score | 39.40 ± 2.85 | 12.88 ± 2.14 | 31.43 ± 2.86 | 10.00 ± 4.52 | 0.000 |

| Disease phase | - | - | 0.072 | ||

| Active phase | 25 (56.82) | 19 (43.18) | - | - | |

| Remission phase | 5 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) | - | - | |

| Disease extent | - | - | 0.534 | ||

| Proctitis | 9 (40.91) | 13 (59.09) | - | - | |

| Left-sided colitis | 10 (52.63) | 9 (47.37) | - | - | |

| Extensive colitis | 11 (57.90)) | 8 (42.10) | - | - | |

| Mayo score | - | - | 0.065 | ||

| 0 | 5 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) | - | - | |

| 1 | 5 (45.45) | 6 (54.55) | - | - | |

| 2 | 12 (50.00) | 12 (50.50) | - | - | |

| 3 | 8 (88.89) | 1 (11.11) | - | - |

Based on MS1 and MS2 data, database searches (e.g., Metlin and HMDB) revealed 5357 metabolites. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of these metabolites showed that peptides were the most abundant metabolite class, accounting for 20.71% of the total metabolite composition, followed by lipids (13.57%), organic acids (12.14%), steroids (11.43%), carbohydrates (11.43%), hormones and neurotransmitters (10.71%). Other metabolite classes, such as nucleic acids, vitamins and cofactors, and antibiotics, individually accounted for < 10% of the total metabolite composition. At the secondary classification level, amino acids, hydroxy acids, fatty acids, and monosaccharides were the most abundant compounds, whereas other classes contained fewer than 10 compounds. Further compound classification using HMDB and inter-group comparisons revealed differences in metabolite expression among the four groups, with the relative abundance of lipids and lipid-like molecules being significantly higher in the HHN group than in the UC groups (Figure 1A-C).

Principal component analysis (PCA) showed significant inter-group differences (P = 0.001). As shown in Figure 1D, the discrimination between the HUCF and HUCN groups and between the HHF and HHN groups was limited. Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) showed clear separation between groups, indicating significant inter-group differences. Volcano plots were generated to visualize differentially expressed metabolites (Figure 2). Overall, 262 differentially expressed metabolites, with 68 upregulated and 194 downregulated metabolites, were identified between the HUCF and HUCN groups. A total of 190 differentially expressed metabolites, with 45 upregulated and 145 downregulated metabolites, were identified between the HHF and HHN groups. A total of 1536 differentially expressed metabolites, with 662 upregulated and 874 downregulated metabolites, were identified between the HUCF and HHF groups. A total of 1409 differentially expressed metabolites, with 517 upregulated and 892 downregulated metabolites, were identified between the HUCN and HHN groups.

After the removal of variables with ≥ 50% missing values from the raw dataset, Venn diagram analysis of differential metabolites from the four groups revealed 5956 common metabolites. Subsequent cluster analysis divided these metabolites into 10 subclasses, and the expression patterns of the top 50 metabolites in the four groups were visualized (Figure 3A). Results revealed that subclusters 2, 6, 9, and 10 were upregulated in the UC groups and downregulated in the non-UC groups; subclusters 1, 3, 5, and 8 were downregulated in the UC groups and upregulated in the non-UC groups; and subcluster 4 was upregulated in the fatigue groups (HUCF and HHF) and downregulated in the non-fatigue groups (HUCN and HHN). The expression of linoleoyl ethanolamide (LEA) was significantly differences between the HUCF and HUCN groups, suggesting its potential as a key differential metabolite (Figure 3B).

Based on variable importance in projection (VIP) values (threshold ≥ 1), metabolites significantly contributing to inter-group differences were screened, and the top 30 metabolites were visualized. The expression patterns of these differential metabolites were as follows: In the HHF group vs HHN group, berberine had the highest VIP score, followed by (1S, 3R, 4R)-8,10-dihydroxyfenchone 10-O-β-D-glucoside and vaccinoside. In the HUCF group vs HHF group, key metabolites were nae (22:5), N-[4-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-1,3-thiazol-2-yl]-thiophene-2-carboxamide, and berberine, which exhibited higher overall expression levels in the HUCF group. In the HUCF group vs HUCN group, N,N-diallyl-tyrosyl-aminoisobutyryl-aminoisobutyryl-phenylalanyl-leucine, 4-hydroxyvalsartan, vertilmicin, and Lys-Gln-His-Lys were downregulated in the HUCF group, with only Lys-Gln-His-Lys showing a significant difference in expression. In the HUCN group vs HHN group, differential metabolites were usually upregulated in the HUCN group, with the top three metabolites being N-[4-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-1,3-thiazol-2-yl]-thiophene-2-carboxamide, gamma-glutamylcysteine, and 4-oxo-4-(pyridin-4-ylmethylamino) but-2-enoic acid. Comparative analysis revealed that N-[4-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-1,3-thiazol-2-yl]-thiophene-2-carboxamide was significantly differentially expressed in the HUCF group vs HHF group, HUCN group vs HHN group, and HUCF group vs HUCN group, with its expression being high in the HUCF group and HUCN group but low in the HUCF group vs HUCN group (Figure 3C-F).

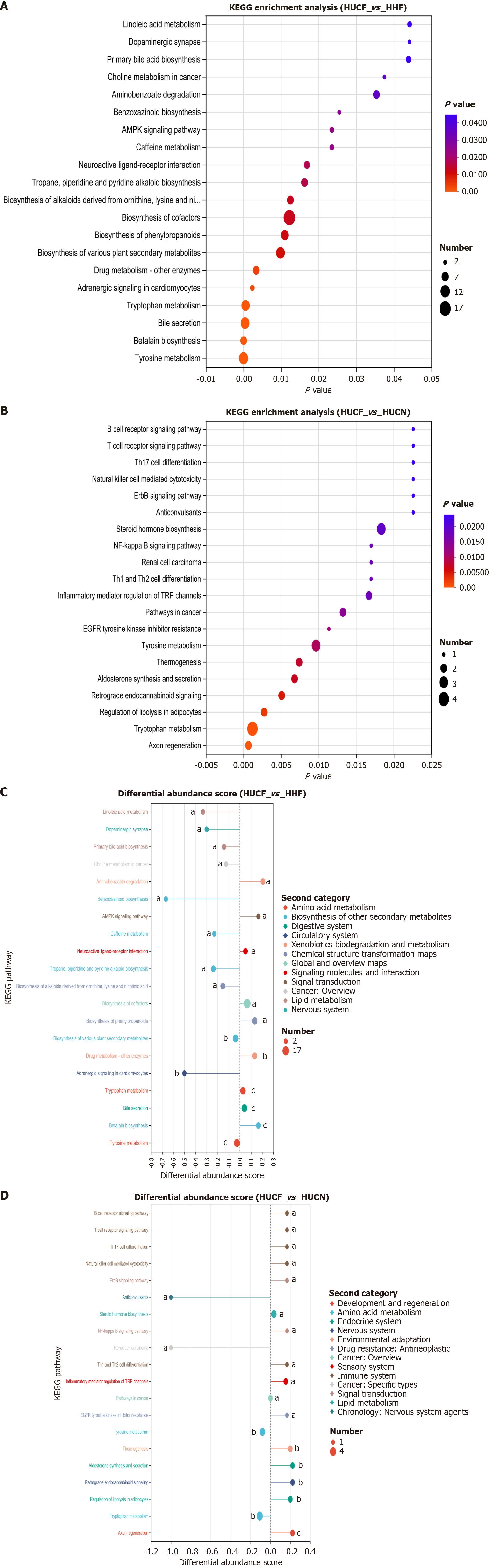

KEGG enrichment analysis of 88 metabolites unique to the HUCF group revealed that thromboxane (TX) was enriched in pathways such as eicosanoid metabolism, platelet activation, and aflatoxin biosynthesis. Other metabolic pathways also contained metabolites with potential biological significance, such as 5-hydroxyferulic acid and coumarinic acid (Figure 4A).

The differential metabolites in the HUCN group vs HHN group and HUCF group vs HHF group were, significantly enriched in pathways such as tryptophan metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, beta lain biosynthesis, and cofactors biosynthesis. In the HHF group vs HHN group and HUCF group vs HUCN group, tyrosine and tryptophan metabolic pathways were found to play important roles in UC. In the HUCN group vs HHN group, tryptophan metabolism showed en

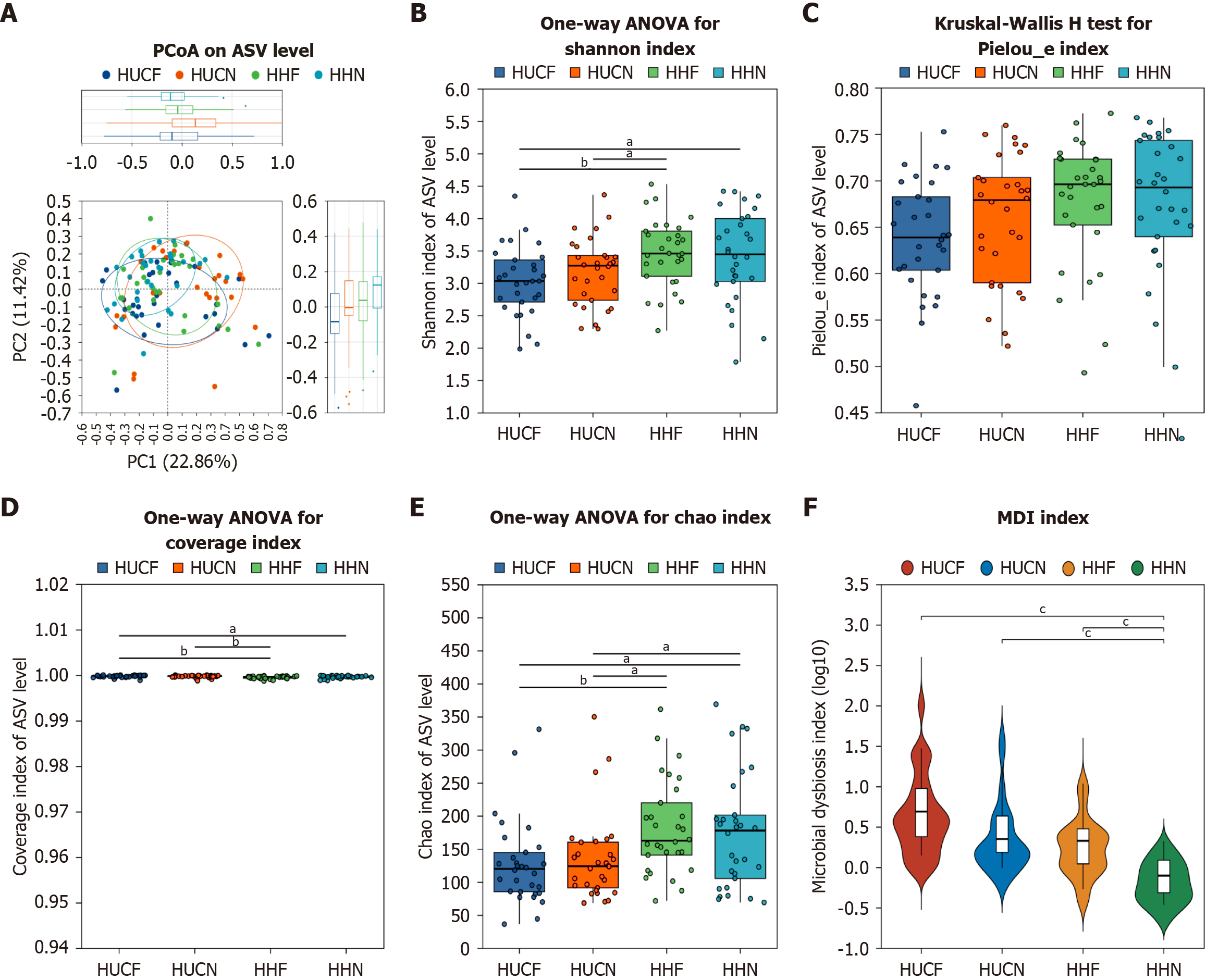

β-diversity: Principal coordinate analysis of β-diversity indices among the four groups yielded a scatter plot with the horizontal coordinate representing a principal component 1 contribution rate of 22.86% and the vertical coordinate representing a principal component 2 contribution rate of 11.42%. The plot showed that the HHN group had the best reproducibility and the smallest internal differences. A P value of < 0.05 indicated overall significant differences among the four groups; however, the trend was not evident. Subsequently, non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis was used to assess the overall similarity of experimental data among the four groups and determine whether the differences were significant. Results revealed significant differences (P = 0.001) among the four groups (Figure 6A).

α-diversity: At the ASV level, the Chao index, Shannon index, Pielou_e index, and coverage were used to assess the richness, diversity, evenness, and sequencing depth of gut microbial communities, respectively. Significant differences were observed in microbial community structure between the HUCF group and HHF group. Further analysis revealed that the richness and diversity of gut microbial communities were lower in the HUCF group than in the other three groups (Figure 6B-E). Compared with the HHN group, the HUCF group showed significant gut microbiota dysbiosis, with the degree of dysbiosis decreasing in the following order: HUCF > HUCN > HHF > HHN (Figure 6F).

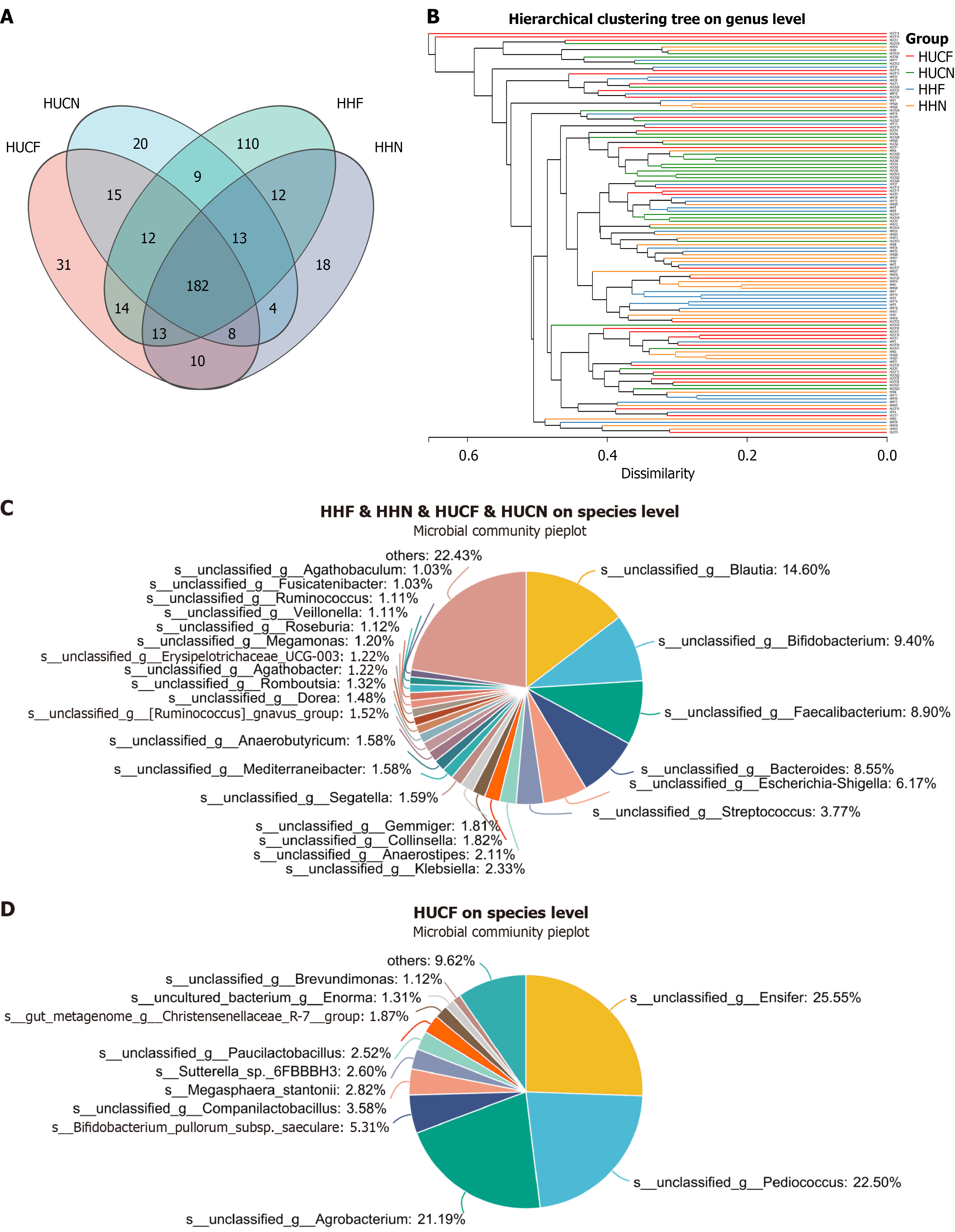

A Venn diagram was generated to compare and analyze the gut microbial communities of the four groups at the genus level. Results revealed that 31 genera were unique to the HUCF group. Among these genera, Ensifer exhibited the highest relative abundance (31.78%), followed by Pediococcus (27.99%) and Agrobacterium (26.36%). The remaining genera, including Companilactobacillus, Paucilactobacillus, and Brevundimonas, collectively accounted for < 5% of the total microbial composition. Furthermore, 248 genera were common among the four groups. Among them, Blautia showed the highest relative abundance (14.91%), followed by Bacteroides (9.32%), Bifidobacterium (9.21%), Faecalibacterium (8.73%), and Escherichia-Shigella (6.04%). All other genera individually constituted < 5% of the total microbial composition (Figure 7).

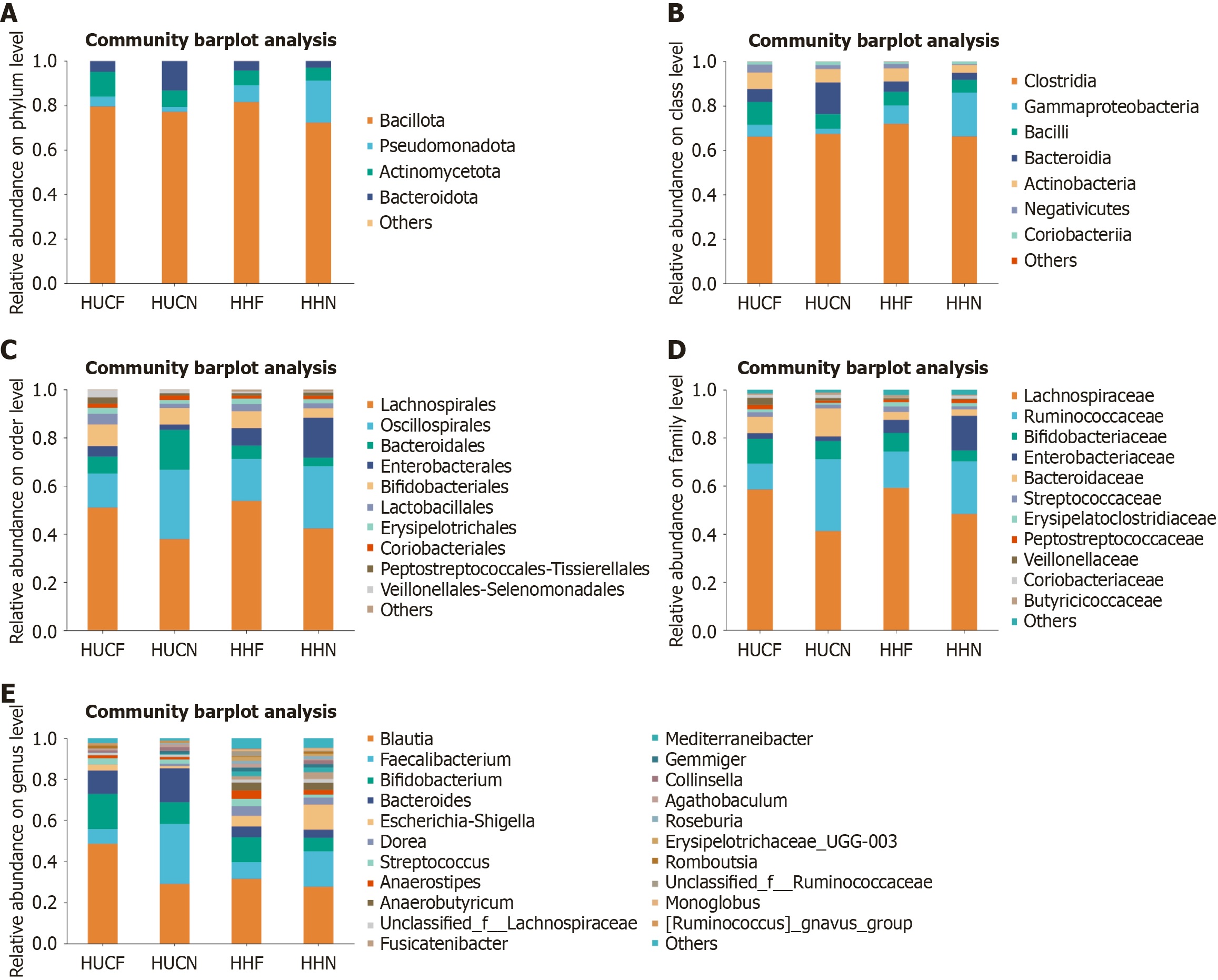

Analysis of microbial community structure at different taxonomic levels revealed that the most abundant microbes in all groups were Bacillota (phylum), Clostridia (class), Lachnospirales (order), Oscillospirales (order), Lachnospiraceae (family), and Blautia (genus). The dominant microbes in the HUCF group were Actinomycetota (phylum), Bacilli (class), and Veillonellaceae (family). Those in the HUCN group were Bacteroidota (phylum), Bacteroidia (class), Bacteroidales (order), Bacteroidaceae (family), and Bacteroides (genus). Those in the HHN group were Pseudomonadota (phylum), Gammaproteobacteria (class), Enterobacterales (order), and Enterobacteriaceae (family). The relative abundances of Lactobacillales (order), Lachnospirales (order), Lachnospiraceae (family), Klebsiella (genus), Segatella (genus), [Ruminococcus]gnavus_group (genus), Blautia (genus), Romboutsia (genus), and Ruminococcus (genus) were higher in the HUCF and HHF groups than in the HUCN and HHN groups. Conversely, the relative abundances of Oscillospirales (order) and Ruminococcaceae (family) were lower in the HUCF and HHF groups than in the HUCN and HHN groups. Compared with the non-UC groups, the UC groups showed higher relative abundances of Bacteroides (genus), Streptococcus (genus), Dialister (genus), Megamonas (genus), Agathobaculum (genus), and Ligilactobacillus (genus). In addition, the relative abundance of Ruminococcus (genus) was significantly higher in the HHF group than in the other three groups. The relative abundances of norank_f_[Eubacterium]_coprostanoligenes_group, Haemophilus, and Phascolarctobacterium (genus) were significantly higher in the HHN group, whereas that of Ligilactobacillus (genus) was very low, accounting for only 0.02% of the total microbial composition (Figure 8).

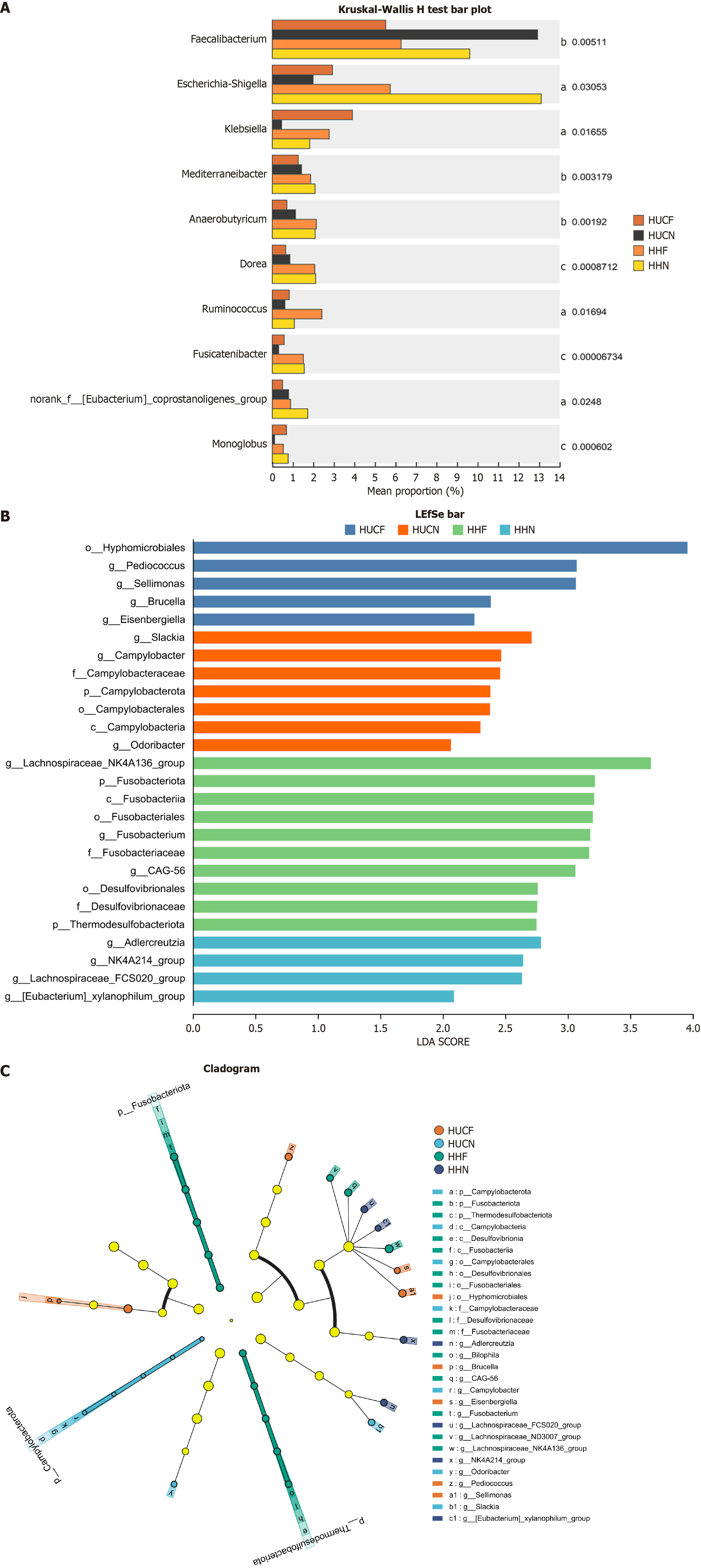

Species differences: The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was used for multi-group comparisons at the genus level. Compared with the non-fatigue groups (HUCN and HHN), the fatigue groups (HUCF and HHF) showed significantly higher abundances of Faecalibacterium, Mediterraneibacter, and Sellimonas but significantly lower abundances of Ruminococcus, norank_f_[Eubacterium]_coprostanoligenes_group, UCG-002, [Eubacterium]_eligens_group, and Akkermansia. Notably, the abundance of Anaerococcus was substantially higher in the HUCF group than in the other three groups (Figure 9A).

Linear discriminant analysis effect size analysis further identified signature microbial taxa unique to each group. The HUCF group showed high abundances of Hyphomicrobiales (order/family), Brucella (genus), Eisenbergiella (genus), Pediococcus (genus), and Sellimonas (genus). The HUCN group showed high abundances of Campylobacter, specifically Campylobacterota (phylum), Campylobacteria (class), Campylobacterales (order), Campylobacteraceae (family), Campylobacter (genus), Odoribacter (genus), and Slackia (genus). The HHF group showed high abundances of Fusobacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Lachnospiraceae, particularly Fusobacteriota (phylum), Thermodesulfobacteriota (phylum), Desulfovibrionia (class), Fusobacteriia (class), Desulfovibrionales (order), Fusobacteriales (order), Desulfovibrionaceae (family), Fusobacteriaceae (family), Bilophila (genus), CAG-56 (provisional name, uncultured group), Fusobacterium (genus), Lachnospiraceae_ND3007_group, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group. The HHN group had high abundances of Adlercreutzia (genus), Lachnospiraceae_FCS020_group, NK4A214_group (usually belonging to Lachnospiraceae), and [Eubacterium]_xylanophilum_group (Figure 9B and C).

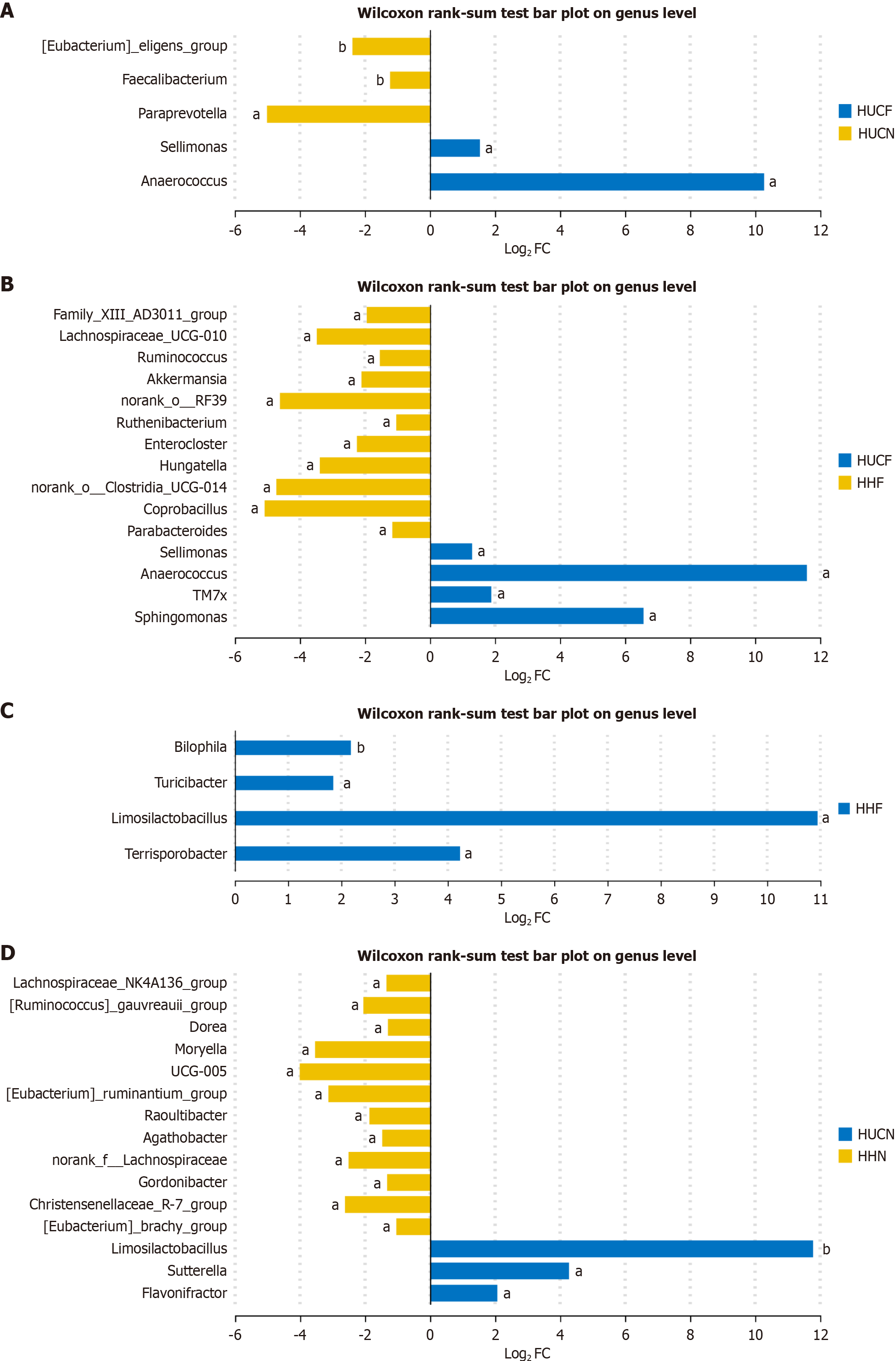

In the HUCF group vs HUCN group, Anaerococcus and Sellimonas were significantly enriched in the HUCF group, whereas Paraprevotella, [Eubacterium]_eligens_group, and Faecalibacterium were significantly enriched in the HUCN group. Anaerococcus showed the highest degree of enrichment in the HUCF group, with statistical significance (Figure 10A).

In the HUCF group vs HHF group, Anaerococcus, Sellimonas, candidate phylum TM7x (TM7x), and Sphingomonas were significantly enriched in the HUCF group, whereas norank_o_Clostridia_UCG-014, Paraprevotella, Lachnospiraceae_ND

In the HHF group vs HHN group, Limosilactobacillus, Turicibacter, Terrisporobacter, and Bilophila were significantly enriched in the HHF group, whereas Limosilactobacillus showed very low enrichment in the HHN group (Figure 10C).

In the HUCN group vs HHN group, Limosilactobacillus, Flavonifractor, and Sutterella were significantly enriched in the HUCN group, whereas Lachnoclostridium, Lachnospiraceae_FCS020_group, norank_f_Oscillospiraceae, Marvinbryantia, Family

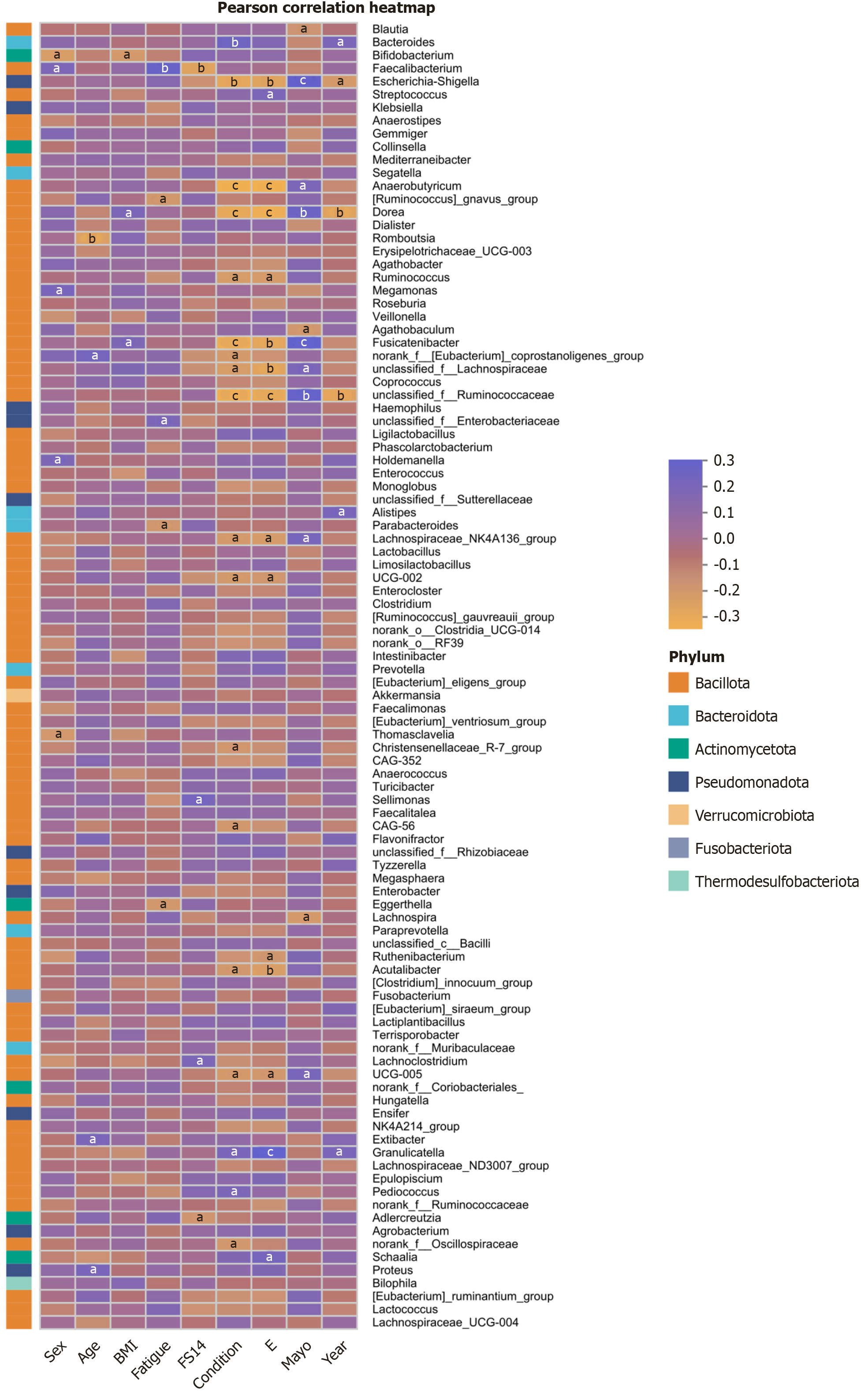

Correlations between clinical factors: Correlation analysis between gut microbiota and clinical factors revealed that several genera were significantly associated with clinical manifestations and fatigue severity in patients with UC. In particular, the abundance of Faecalibacterium (genus) was strongly correlated with the severity of fatigue. The abundances of Dorea (genus), Escherichia-Shigella (genus), and unclassified_f__Ruminococcaceae were significantly correlated with the extent, stage, and course of UC and Mayo scores. In addition, the abundances of Fusicatenibacter (genus), Anaerobutyricum (genus), unclassified_f__Lachnospiraceae, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group showed strong correlations with UC severity (Figure 11).

The onset of UC is closely related to gut microbiota dysbiosis[27]. Microbial imbalance can lead to overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, disrupting the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier[28]. Studies have shown that gut microbiota dysbiosis can trigger abnormal antigen responses in patients with UC, exacerbating intestinal inflammation[29]. Compared with healthy individuals, patients with UC have a significantly different gut microbial structure at multiple taxonomic levels (family, genus, and species), typically characterized by a decrease in the abundance of beneficial bacteria and an increase in the abundance of harmful bacteria[30]. This imbalance promotes pathogen colonization and leads to the production of harmful metabolites, stimulating the intestinal mucosa, promoting the release of inflammatory mediators, and consequently aggravating intestinal inflammation[21]. Gut microbiota can influence UC development by regulating epithelial cell metabolism. The intestinal mucosal epithelium not only functions as a physical barrier but also forms a complex symbiotic relationship with microbes and their metabolites[31,32]. For example, gut microbe-derived butyrate can create a low-oxygen environment in the epithelium, which is crucial for maintaining epithelial barrier function[33]. The synthesis and transformation of various metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids, are closely related to disease progression. The distinctive metabolic phenotype of the intestinal mucosa is a major factor in investigating the inflammatory mechanisms underlying UC development through metabolomics.

Gut microbes interact with metabolites, jointly regulating host inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism. Fecal microbiota transplantation can induce clinical remission in some patients with UC[34]. A recent study identified 84 metabolites significantly associated with UC progression, indicating that metabolomic changes play an important role in UC development[35]. When intestinal mucosal inflammation is highly active, the fatty acid metabolic profile changes significantly. For example, increased arachidonic acid levels can exacerbate inflammation[36].

In this study, we used untargeted metabolomic analysis to determine unique changes in gut microbes and metabolites in patients with HUCF. PCA and PLS-DA revealed differences in metabolite expression profiles among the four study groups, with the differences between the HUCF group and HUCN group and between the HHF group and HHN group suggesting that fatigue affects metabolite expression. Furthermore, the abundance of lipids was significantly lower in the UC groups than in the non-UC groups, and a larger number of differentially expressed metabolites were identified in the UC groups. These findings validate that patients with UC have significant metabolic disorders. Comparative analysis revealed significant differences in metabolite expression among the four groups. These metabolites may be key differential metabolites associated with UC.

LEA, an N-acylethanolamine, has anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects[37,38]. It can be hydrolyzed into linoleic acid and ethanolamine and regulates metabolism and inflammatory responses by activating PPARα receptors. Linoleic acid can enhance energy supply[39]. This study showed that LEA was upregulated in the fatigue groups (HUCF and HHF) and differentially expressed between the HUCF group and HUCN group. Studies have shown that LEA can inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage inflammation, alleviate contact dermatitis induced by 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene, and suppress the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines[40]. AEA is one of the most biologically active endocannabinoids in humans. It participates in neuroregulation, energy metabolism, and inflammatory responses through cannabinoid receptors (CB1/CB2) and TRPV1 channels[41,42]. This study showed that AEA was significantly enriched in the HUCF group and was involved in pathways such as axon regeneration, thermogenesis, and retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. GCA, a sterolic acid, is a bile acid conjugate synthesized from cholic acid and glycine in the liver. It facilitates the emulsification and absorption of fats and sterols[43]. The properties of bile acids enable GCA to effectively inhibit bacterial growth, alleviate inflammation and oxidative stress, modulate immune responses, and suppress breast disease[44]. GCA can serve as a diagnostic marker for early hepatobiliary dysfunction and is positively correlated with BMI[45]. Studies on classification models of IBD have found increased GCA levels in patients with IBD[46]. In this study, the HUCF group showed increased GCA levels. Notably, metabolites with anti-inflammatory properties were upregulated in patients with HUCF, suggesting that fatigue is related to compensatory anti-inflammatory responses or altered inflammatory tolerance. Studies have indicated that fatigue is positively correlated with the degree of inflammation; for example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis usually have inflammation-driven fatigue[47]. In addition, fatigue following both mental and physical activities is associated with increased inflammatory responses[48]. In patients with myasthenia gravis, the observed strong correlation between fatigue symptoms and C-reactive protein levels indicates that inflammatory responses can trigger the onset of fatigue[49].

TX is a pro-inflammatory eicosanoid derived from arachidonic acid. The two most important compounds in the TX family include TXA2 and its stable metabolite, TXB2[50,51]. TX can increase the abundance of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and leukotrienes; damage endothelial cells; and cause vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation. Increased platelet counts and platelet activation have been observed in patients with IBD. Platelets can directly trigger inflammatory responses[52,53]. Numerous studies have reported increased TX levels in both animal models of IBD and patients with IBD[54,55]. However, in mice with exercise-induced fatigue, TXB2 levels are significantly low in the gastric mucosal tissue[56]. In this study, TX was detected only in patients with HUCF, indicating its potential as a specific metabolic marker for this population.

16S rRNA sequencing showed that the HUCF group exhibited the lowest microbial richness and diversity and the most pronounced gut microbiota dysbiosis. Analysis of microbial community structure across the four groups revealed that Bacteroides was the dominant genus in the HUCN group. The signature gut microbiota of the HUCN group, from the phylum to genus levels, was primarily composed of Campylobacter, a well-established pathogen. Although Slackia can participate in human bile acid cycling and hormone metabolism, some studies have reported its altered abundance in patients with IBD. Odoribacter, a beneficial bacterium, produces butyrate and is involved in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and inhibiting inflammation. The gut microbial composition in the HUCF group appeared disorganized and irregular. Signature microbes in this group included harmful bacteria such as Eisenbergiella and Sellimonas, which are positively associated with IBD and colorectal cancer. Pediococcus, a beneficial genus, can alleviate intestinal inflammation. In the HHF group, signature microbes included Fusobacterium (genus), Desulfovibrionaceae (family), Bilophila (genus), and CAG-56, which are often found to have higher abundances in patients with IBD and are positively correlated with inflammation. The HHN group was mostly enriched with beneficial bacteria. These findings suggest that gut microbes associated with fatigue are related to inflammation.

Anaerococcus, a Gram-positive anaerobic bacterium, is associated with inflammatory conditions such as obesity and moderate-to-severe acute pancreatitis[57,58]. This study suggests that Anaerococcus contributes to the development of HUCF through pro-inflammatory mechanisms. The specific enrichment of Anaerococcus in the HUCF group suggests its potential as a microbial biomarker for this patient population.

This study revealed that gut microbial and metabolite profiles were altered in patients with HUCF. TX was identified as a key metabolite and Anaerococcus was identified as a key gut microbe in these patients. Although this study does not conclusively establish a relationship between TX, Anaerococcus, and the occurrence of fatigue in UC, it provides novel insights into the pathogenesis of HUCF.

We would like to thank all participants for collecting the data for this study.

| 1. | Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2718] [Article Influence: 302.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Kushkevych I, Bychkov M, Bychkova S, Gajdács M, Merza R, Vítězová M. ATPase Activity of the Subcellular Fractions of Colorectal Cancer Samples under the Action of Nicotinic Acid Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Louis E, Bossuyt P, Colard A, Nakad A, Baert D, Mana F, Caenepeel P, Branden SV, Vermeire S, D'Heygere F, Strubbe B, Cremer A, Setakhr V, Baert F, Vijverman A, Coenegrachts JL, Flamme F, Hantson A, Zhou J, Van Gassen G. Change in fatigue in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease initiating biologic therapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2025;57:707-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu F, Hu J, Yang Q, Ji Y, Cheng C, Zhu L, Shen H. Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in patients with ulcerative colitis in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matura LA, Malone S, Jaime-Lara R, Riegel B. A Systematic Review of Biological Mechanisms of Fatigue in Chronic Illness. Biol Res Nurs. 2018;20:410-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Panaccione R, Bleakman AP, Schreiber S, Travis S, Dubinsky M, Hibi T, Gibble TH, Panni T, Kayhan C, Flynn EJ, Favia AD, Atkinson C, Rubin DT. US and European Patient and Health Care Professional Perspectives on Fatigue in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease: Results From the Communicating Needs and Features of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Experiences Survey. Crohns Colitis 360. 2025;7:otaf011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hart A, Miller L, Büttner FC, Hamborg T, Saxena S, Pollok RCG, Stagg I, Wileman V, Aziz Q, Czuber-Dochan W, Dibley L, Mihaylova B, Moss-Morris R, Roukas C, Norton C. Fatigue, pain and faecal incontinence in adult inflammatory bowel disease patients and the unmet need: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Enns MW, Bernstein CN, Kroeker K, Graff L, Walker JR, Lix LM, Hitchon CA, El-Gabalawy R, Fisk JD, Marrie RA; CIHR Team in Defining the Burden and Managing the Effects of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Chronic Immunoinflammatory Disease. The association of fatigue, pain, depression and anxiety with work and activity impairment in immune mediated inflammatory diseases. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chavarría C, Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Ezquiaga E, Bujanda L, Rivero M, Argüelles-Arias F, Martín-Arranz MD, Martínez-Montiel MP, Valls M, Ferreiro-Iglesias R, Llaó J, Moraleja-Yudego I, Casellas F, Antolín-Melero B, Cortés X, Plaza R, Pineda JR, Navarro-Llavat M, García-López S, Robledo-Andrés P, Marín-Jiménez I, García-Sánchez V, Merino O, Algaba A, Arribas-López MR, Banales JM, Castro B, Castro-Laria L, Honrubia R, Almela P, Gisbert JP. Prevalence and Factors Associated With Fatigue in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Multicentre Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:996-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Holten KIA, Bernklev T, Opheim R, Johansen I, Olsen BC, Lund C, Strande V, Medhus AW, Perminow G, Bengtson MB, Cetinkaya RB, Vatn S, Frigstad SO, Aabrekk TB, Detlie TE, Hovde Ø, Kristensen VA, Småstuen MC, Henriksen M, Huppertz-Hauss G, Høivik ML, Jelsness-Jørgensen LP. Fatigue in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results from a Prospective Inception Cohort, the IBSEN III Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:1781-1790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiang Q, Yang D, Jiang R, Wan S, Wu M, Xu D, Zhou J. Analysis of factors influencing sleep disorders in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:34104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li X, Wu K, Qian L, Wang S, Xu X, Feng Z, Cai H, Yu Y, Wang H, Sun Y. Watching Positive Videos Facilitates Mental Fatigue Recovery: A Task fMRI Study. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2025;33:3965-3975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Che X, Ranjan A, Guo C, Zhang K, Goldsmith R, Levine S, Moneghetti KJ, Zhai Y, Ge L, Mishra N, Hornig M, Bateman L, Klimas NG, Montoya JG, Peterson DL, Klein SL, Fiehn O, Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. Heightened innate immunity may trigger chronic inflammation, fatigue and post-exertional malaise in ME/CFS. NPJ Metab Health Dis. 2025;3:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ferrando SJ, Lynch ST, Dornbush R, Groenendaal E, Klepacz L, Shahar S, Bilal A, Mansour R, Aftab S, Libretti A. Associations of elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor alpha with neuropsychiatric symptoms of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). J Psychiatr Res. 2025;190:128-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hamilton A, Whiley L, Kadyrov M, Chapman B. Forensic biomarker discovery: Utilising metabolomics to elucidate prospective fatigue biomarkers for eventual roadside detection. Sci Justice. 2025;65:101278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li H, Xue R, Di Y, Cheng X, Li S, Li J, Fan Q, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. Potential mechanisms underlying pathological fatigue-induced cardiac dysfunction. FASEB J. 2025;39:e70511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Withycombe JS, Bai J, Xiao C, Eldridge RC. Metabolomic Associations With Fatigue and Physical Function in Children With Cancer: A Pilot Study. Biol Res Nurs. 2025;27:453-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhu J, Zhu Y, Song G. Effect of Probiotic Yogurt Supplementation(Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12) on Gut Microbiota of Female Taekwondo Athletes and Its Relationship with Exercise-Related Psychological Fatigue. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | He P, Chen L, Qin X, Du G, Li Z. Astragali Radix-Codonopsis Radix-Jujubae Fructus water extracts ameliorate exercise-induced fatigue in mice via modulating gut microbiota and its metabolites. J Sci Food Agric. 2022;102:5141-5152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huang S, Yang X, Ma J, Li C, Wang Y, Wu Z. Ethanol extract of propolis relieves exercise-induced fatigue via modulating the metabolites and gut microbiota in mice. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1549913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kushkevych I, Dvořáková M, Dordevic D, Futoma-Kołoch B, Gajdács M, Al-Madboly LA, Abd El-Salam M. Advances in gut microbiota functions in inflammatory bowel disease: Dysbiosis, management, cytotoxicity assessment, and therapeutic perspectives. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2025;27:851-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Feagins LA, Moore P, Crabtree MM, Eliot M, Lemay CA, Loughlin AM, Gaidos JKJ. Impact of Fatigue on Work Productivity, Activity Impairment, and Healthcare Resource Utilization in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2025;7:otae073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bogale K, Maheshwari P, Kang M, Gorrepati VS, Dalessio S, Walter V, Stuart A, Koltun W, Bernasko N, Tinsley A, Williams ED, Clarke K, Coates MD. Symptoms associated with healthcare resource utilization in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Desai R, Lee WJ, Griffith J, Chen N, Loftus EV Jr. Economic Burden of Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2023;5:otad020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Singh S, Qian AS, Nguyen NH, Ho SKM, Luo J, Jairath V, Sandborn WJ, Ma C. Trends in U.S. Health Care Spending on Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 1996-2016. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang K, Zhang C, Gong R, Jiang W, Ding Y, Yu Y, Chen J, Zhu M, Zuo J, Huang X, Wang L, Li P, Sun X. From west to east: dissecting the global shift in inflammatory bowel disease burden and projecting future scenarios. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:2696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Prosty C, Katergi K, Papenburg J, Lawandi A, Lee TC, Shi H, Burnham P, Swem L, Routy B, Yansouni CP, Cheng MP. Causal role of the gut microbiome in certain human diseases: a narrative review. eGastroenterology. 2024;2:e100086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li H, Wang K, Hao M, Liu Y, Liang X, Yuan D, Ding L. The role of intestinal microecology in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e36590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Walker AW, Sanderson JD, Churcher C, Parkes GC, Hudspith BN, Rayment N, Brostoff J, Parkhill J, Dougan G, Petrovska L. High-throughput clone library analysis of the mucosa-associated microbiota reveals dysbiosis and differences between inflamed and non-inflamed regions of the intestine in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dong LN, Wang M, Guo J, Wang JP. Role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites in inflammatory bowel disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132:1610-1614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Madsen K, Cornish A, Soper P, McKaigney C, Jijon H, Yachimec C, Doyle J, Jewell L, De Simone C. Probiotic bacteria enhance murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:580-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 747] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Glover LE, Lee JS, Colgan SP. Oxygen metabolism and barrier regulation in the intestinal mucosa. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3680-3688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, Saeedi B, Scholz CC, Bayless AJ, Wilson KE, Glover LE, Kominsky DJ, Magnuson A, Weir TL, Ehrentraut SF, Pickel C, Kuhn KA, Lanis JM, Nguyen V, Taylor CT, Colgan SP. Crosstalk between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:662-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 807] [Cited by in RCA: 1283] [Article Influence: 116.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, Tijssen JG, Hartman JH, Duflou A, Löwenberg M, van den Brink GR, Mathus-Vliegen EM, de Vos WM, Zoetendal EG, D'Haens GR, Ponsioen CY. Findings From a Randomized Controlled Trial of Fecal Transplantation for Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:110-118.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 616] [Cited by in RCA: 703] [Article Influence: 63.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bourgonje AR, Ibing S, Livanos AE, Ganjian DY, Argmann C, Sands BE, Dubinsky MC, Helmus DS, Jacobsen HA, Larsen L, Jess T, Suarez-Fariñas M, Renard BY, Colombel JF, Ungaro RC. Distinct perturbances in metabolic pathways associate with disease progression in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19:jjaf082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pearl DS, Masoodi M, Eiden M, Brümmer J, Gullick D, McKeever TM, Whittaker MA, Nitch-Smith H, Brown JF, Shute JK, Mills G, Calder PC, Trebble TM. Altered colonic mucosal availability of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in ulcerative colitis and the relationship to disease activity. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:70-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Barrie N, Manolios N, Stuart J, Chew T, Arnold J, Sadsad R, De Campo L, Knott RB, White J, Booth D, Ali M, Moghaddam MJ. Design and function of targeted endocannabinoid nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2022;12:17260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lambert DM, Vandevoorde S, Jonsson KO, Fowler CJ. The palmitoylethanolamide family: a new class of anti-inflammatory agents? Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:663-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Luo Y, Yu Y, Zeng F, Yi Y, Lu Z, Lin B, Chen L, Zeng Z, Luo D, Liu A. Acetylation of FABP3 alleviates radioimmunotherapy-induced cardiomyocyte senescence by modulating long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;160:114912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ishida T, Nishiumi S, Tanahashi T, Yamasaki A, Yamazaki A, Akashi T, Miki I, Kondo Y, Inoue J, Kawauchi S, Azuma T, Yoshida M, Mizuno S. Linoleoyl ethanolamide reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophages and ameliorates 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced contact dermatitis in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;699:6-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Qian X, Liu W, Chen Y, Zhang J, Jiang Y, Pan L, Hu C. A UPLC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determination of arachidonic acid, stearic acid, and related endocannabinoids in human plasma. Heliyon. 2024;10:e28467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kabeiseman E, Paulsen RT, Burrell BD. Characterization of a Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase (FAAH) in Hirudo Verbana. Neurochem Res. 2024;49:3015-3029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Piscon B, Fichtman B, Harel A, Adler A, Rahav G, Gal-Mor O. The Effect of glycocholic acid on the growth, membrane permeability, conjugation and antibiotic susceptibility of Enterobacteriaceae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2025;15:1550545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Li J, Zhang C, Wang Y, Tian M, Xie C, Hu H. Research progress on the synthesis process, detection method, pharmacological effects and application of glycocholic acid. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1492070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Yamamura R, Okubo R, Ukawa S, Nakamura K, Okada E, Nakagawa T, Imae A, Kimura T, Tamakoshi A. Increased fecal glycocholic acid levels correlate with obesity in conjunction with the depletion of archaea: The Dosanco Health Study. J Nutr Biochem. 2025;139:109846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Xu RH, Shen JN, Lu JB, Liu YJ, Song Y, Cao Y, Wang ZH, Zhang J. Bile acid profiles and classification model accuracy for inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e38457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chalupczak NV, Aydemir B, Isaacs A, Muhammad LN, Song J, Reid KJ, Grimaldi D, Carns M, Dennis-Aren K, Dunlop DD, Wallace BI, Zee PC, Lee YC. Sleep Matters: Exploring the Link Between Sleep Disturbances and Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2025;77:1368-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Weinstein AA, Seth K, Gordy S, Jabbar K, Noori N, Birerdinc A, Baranova A, Winter P, Gerber LH. A pilot investigation of the impact of acute mental and physical fatigue exposure on inflammatory cytokines and state fatigue level in breast cancer survivors. BMC Womens Health. 2025;25:263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Ruiter AM, van Meijgaarden KE, Joosten SA, Spitali P, Huijbers MG, van Zwet EW, Badrising UA, Tannemaat M, Verschuuren JJ. Correlation of C-Reactive Protein With Severe Fatigue in Patients With Myasthenia Gravis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2025;12:e200468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Carty E, Nickols C, Feakins RM, Rampton DS. Thromboxane synthase immunohistochemistry in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Benndorf RA. The potential of thromboxane A(2) as a therapeutic target: prospects and challenges. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2025;29:601-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Di Sabatino A, Santilli F, Guerci M, Simeone P, Ardizzone S, Massari A, Giuffrida P, Tripaldi R, Malara A, Liani R, Gurini E, Aronico N, Balduini A, Corazza GR, Davì G. Oxidative stress and thromboxane-dependent platelet activation in inflammatory bowel disease: effects of anti-TNF-α treatment. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116:486-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Contursi A, Tacconelli S, Di Berardino S, De Michele A, Patrignani P. Platelets as crucial players in the dynamic interplay of inflammation, immunity, and cancer: unveiling new strategies for cancer prevention. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1520488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kikut J, Mokrzycka M, Drozd A, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Ziętek M, Szczuko M. Involvement of Proinflammatory Arachidonic Acid (ARA) Derivatives in Crohn's Disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC). J Clin Med. 2022;11:1861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Carter PR, McElhatten RM, Zhang S, Wright WS, Harris NR. Thromboxane-prostanoid receptor expression and antagonism in dextran-sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Inflamm Res. 2011;60:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Shi JJ, Huang LF. [Effects of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation of "Zusanli" (ST 36) on gastric mucosal injury in exercise stress-induced gastric ulcer rats]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2013;38:181-185. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Gámez-Valdez JS, García-Mazcorro JF, Montoya-Rincón AH, Rodríguez-Reyes DL, Jiménez-Blanco G, Rodríguez MTA, de Vaca RP, Alcorta-García MR, Brunck M, Lara-Díaz VJ, Licona-Cassani C. Differential analysis of the bacterial community in colostrum samples from women with gestational diabetes mellitus and obesity. Sci Rep. 2021;11:24373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 58. | Yu S, Xiong Y, Xu J, Liang X, Fu Y, Liu D, Yu X, Wu D. Identification of Dysfunctional Gut Microbiota Through Rectal Swab in Patients with Different Severity of Acute Pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:3223-3237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/