Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.113935

Revised: October 1, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 131 Days and 15.2 Hours

Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (HIRI) is a major complication in liver transplantation with limited treatment options. Peptidomics offers a promising approach to discover therapeutic peptides.

To identify novel peptides from human liver transplants that could mitigate HIRI and preliminarily explore their mechanisms.

Liver samples from six transplant patients were analyzed using nano-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. A candidate peptide, human liver transplantation peptide 1 (HLTP1), was screened in a murine HIRI model and validated in vitro using AML12 cells. Mechanisms were probed via Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation analysis and rescue experiments with a JNK activator.

HLTP1 was identified as a protective peptide. It reduced liver damage and apoptosis in mice, enhanced cell viability and proliferation, and decreased apoptosis in AML12 cells. Mechanistically, HLTP1 inhibited JNK phosphorylation, and its effects were reversed by JNK activation.

HLTP1 alleviates HIRI by inhibiting JNK-mediated apoptosis, representing a potential therapeutic strategy for liver transplantation.

Core Tip: This study pioneers the discovery of a novel endogenous peptide, human liver transplantation peptide 1, directly from clinical human liver transplant samples using peptidomics. We demonstrate that human liver transplantation peptide 1 confers significant protection against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by specifically inhibiting Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation and subsequent hepatocyte apoptosis. This work is the first to identify a therapeutically promising peptide of human origin with this mechanism for hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury, offering a highly translatable and innovative strategy to improve outcomes in liver transplantation and other ischemic liver conditions.

- Citation: Xie HW, Bao Q, Chen ZX, Zhang XM, Liu XY, Wang R, Cai YS, Sun P. Targeting Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation: A human-derived hepatoprotective peptide human liver transplantation peptide 1 attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(3): 113935

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i3/113935.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.113935

End-stage liver disease (ESLD) is a significant global cause of mortality, with conditions such as liver failure and cirrhosis accounting for over 50% of deaths attributed to ESLD[1,2]. In most cases, liver transplantation remains the only effective treatment for ESLD[3]. Despite high long-term survival rates, liver transplant recipients are still at risk of severe complications, among which hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (HIRI) is unavoidable during liver transplantation[4]. HIRI is a critical pathophysiological event associated with liver trauma, partial hepatectomy, and transplantation. During these situations, the liver sustains further damage when the blood supply is interrupted and then restored, exacerbating the initial ischemic injury[5]. The development of HIRI increases the incidence of primary graft dysfunction as well as acute and chronic rejection, adversely affecting transplant success[6]. HIRI is a significant risk factor for early liver failure and subsequent multiorgan failure, leading to high morbidity and mortality rates in transplant recipients[7,8]. Therefore, developing effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of HIRI is of the utmost importance.

A number of methods are available to mitigate HIRI, which are mainly categorized into pharmacological and mechanical methods. Pharmacological methods include sevoflurane, propofol, sufentanil, edaravone, N-acetylcysteine, rifaximin, prostaglandin A1 and others[9,10]. Mechanical methods include hepatic inflow modulation and machine perfusion, where hepatic inflow modulation includes ischemic preconditioning, remote ischemic preconditioning and pre-retrieval reperfusion, machine perfusion includes hypothermic perfusion, dual hypothermic perfusion, normothermic perfusion and regional normothermic perfusion[9,10]. Although the approach is technically feasible and the results are satisfactory, there are still many problems to be overcome. Indeed, the management of HIRI remains a considerable and unmet clinical challenge. A pivotal limitation is the stark absence of any pharmacologic agent specifically approved by regulatory bodies for the prevention or treatment of HIRI. The pharmacological agents listed above are largely repurposed drugs with limited efficacy and a lack of specificity for the intricate pathways of HIRI. Similarly, while mechanical interventions are valuable, their application can be technically demanding and not universally accessible. This translation gap, where numerous preclinical candidates have failed to become approved therapies, underscores the urgent demand for novel, targeted, and effective therapeutic strategies. Our study addresses this critical void by exploring the potential of endogenous human peptides, which offer the promise of high biocompatibility and mechanistically targeted action, as a new class of therapeutics for HIRI.

Since the advent of insulin over the past century, more than 80 peptide-based drugs have been commercialized, tar

The burgeoning field of therapeutic peptides offers a promising avenue to address complex diseases, leveraging their high specificity and generally favorable safety profiles. Building on this momentum, we sought to explore a novel paradigm in peptide drug discovery for liver transplantation. Despite extensive research, effective pharmacological strategies to prevent HIRI in this setting remain an unmet clinical need. While previous proteomic studies have provided insights into RNA-level and protein-level changes during HIRI[16,17], the potential of naturally occurring, low-molecular-weight peptides as innate protective agents has been largely overlooked. Critically, to our knowledge, a peptidomics approach has not been previously employed to discover therapeutic peptides directly from human liver transplant tissues. This study is the first to bridge this gap. We hypothesized that the human liver itself may produce protective peptides in response to HIRI. To test this, we used mass spectrometry to identify changes in the peptidome during liver transplantation. In addition, using a mouse model of HIRI, we identified a novel peptide with protective effects against HIRI. Among the identified peptides, human liver transplantation peptide 1 (HLTP1) has been found to reduce hepatocyte apoptosis during ischemia-reperfusion injury. We also investigated the underlying mechanisms of action. The findings of this study provide new insights into the alterations in the peptidome during liver transplantation and highlight novel peptides such as HLTP1, which may offer a promising therapeutic approach for managing HIRI.

Liver tissue samples were collected from six liver transplant patients at the Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. All the research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. Peptide profiles pre- and post-transplantation were identified using nano-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Differentially expressed peptides were recorded, with upregulated and downregulated peptides in post-transplant liver tissue compared with pre-transplant samples serving as controls.

The peptide precursor proteins were retrieved from the UniProt database (http://www.uniprot.org/). ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) was used to calculate the molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) of each peptide. To predict the potential functions of these peptide precursor proteins, Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses were conducted using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (http://david.ncifcrf.gov/).

Detailed sequences of the selected peptides are listed in Table 1. The sequence GRKKRRQRRRPPQQ, comprising 14 amino acids, represents a cell-penetrating peptide. All peptides, synthesized by Shanghai Scipeptide Biological Technology Co. (Shanghai, China), had purities exceeding 95%. Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in sterile ultrapure water to prepare a 10 mmol/L stock solution, which was further diluted to the experimental concentrations. The peptides were pre-incubated with the medium for one hour before hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) treatment.

| No. | Peptide sequence | Precurso protein | UniProt accession | Log ratio | P value | MW | PI | Length |

| 1 | FAPPGVPPPP | DAZAP1 | Q96EP5 | -2.3016 | 0.0234 | 974.52 | 5.52 | 10 |

| 2 | ITLEQGKTL | ALDH6A1 | Q02252 | -2.3465 | 0.0274 | 1001.58 | 6.00 | 9 |

| 3 | IVAINDPFID | GAPDH | P04406 | -2.9016 | 0.0047 | 1115.59 | 3.56 | 10 |

| 4 | IIGGDPKGNNF | WDR1 | O75083 | -2.2339 | 0.0161 | 1130.57 | 5.84 | 11 |

| 5 | ITPEVLPGWK | IMMT | Q16891 | -2.4517 | 0.0144 | 1138.64 | 6.00 | 10 |

| 6 | DKNLKPIKPMQ | PGAM1 | P18669 | -2.6614 | 0.0020 | 1310.74 | 9.70 | 11 |

| 7 | AANHDAAIFPGGFG | GATD3A | P0DPI2 | -2.4993 | 0.0294 | 1343.63 | 5.08 | 14 |

| 8 | IASVQTNEVGLKQ | CPS1 | P31327 | -2.2638 | 0.0264 | 1385.75 | 6.00 | 13 |

| 9 | AVPEGFVIPRGNVL | NAMPT | P43490 | -2.4661 | 0.0208 | 1466.82 | 6.05 | 14 |

| 10 | LITNILPFEKINE | ADH1C | P00326 | -2.0812 | 0.0241 | 1542.87 | 4.53 | 13 |

| 11 | ASASGAMAKHEQILVL | VAPA | Q9P0 L0 | -2.0004 | 0.0162 | 1624.86 | 6.79 | 16 |

| 12 | EAIQEKIQEKAVKR | AKR1B10 | O60218 | -2.2136 | 0.0280 | 1668.95 | 8.59 | 14 |

| 13 | KLGDVYVNDAFGTAHR | PGK1 | P00558 | -2.2887 | 0.0148 | 1761.88 | 6.75 | 16 |

| 14 | TEDPARSFQPDTGRIE | PC | P11498 | -3.0851 | 0.0075 | 1817.85 | 4.32 | 16 |

| 15 | LMPHDLARAALTGLLHR | HADHB | P55084 | -2.1911 | 0.0169 | 1884.05 | 9.61 | 17 |

| 16 | EPTEKLPFPIIDDRNRE | PRDX6 | P30041 | -2.3486 | 0.0264 | 2068.06 | 4.51 | 17 |

| 17 | EELAPERGFLPPASEKHGSWG | BHMT | Q93088 | -2.8879 | 0.0117 | 2293.11 | 4.91 | 21 |

| 18 | HEGAGIVESVGEGVTKLKAGDTVIP | ADH5 | P11766 | -2.3797 | 0.0020 | 2462.30 | 4.83 | 25 |

| 19 | ALEKRGYVKAGPWTPEAAVEHPE | BHMT | Q93088 | -2.2247 | 0.0279 | 2534.29 | 5.57 | 23 |

| 20 | AGPWTPEAAVEHPEAVRQLHREF | BHMT | Q93088 | -2.2340 | 0.0055 | 2626.30 | 5.40 | 23 |

| 21 | PVVKKVEQKIANDNSLNHEYLPI | GOT1 | P17174 | -3.4308 | 0.0053 | 2647.43 | 7.17 | 23 |

| 22 | RYIVPMLTVDGKRVPRDAGHPLYPFN | AKR1A1 | P14550 | -2.1004 | 0.0244 | 3010.60 | 9.69 | 26 |

Male C57BL/6 mice aged 6-8 weeks were purchased from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and temporarily housed in our research facility. All experimental protocols adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 86-23, revised 1985) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Tong Ren Hospital.

The experiment began one week after the procurement of the animals. The mice were randomly assigned to four groups: A control group, peptide-treated group, HIRI group, and peptide-treated HIRI group, with 12 mice per group. For the peptide-treated and peptide-treated HIRI groups, peptides were administered via the tail vein at a dose of 5 mg/kg every 12 hours, starting 1 hours before surgery, while the control and HIRI groups received an equivalent volume of saline. The 5 mg/kg dose was selected as a common and efficacious starting point for peptide therapeutics. The dosing interval of 12 hours was determined based on the in vivo half-life of HLTP1 (approximately 12 hours), which was predicted using the Expasy ProtParam tool (https://www.expasy.org/). To induce 70% ischemia, the mice were placed in a supine position on a thermostatic heating pad (37 °C), and the blood supply to the left and middle hepatic lobes was occluded. The ischemia was maintained for 60 minutes, followed by clamp removal. After 24 hours, the mice were euthanized, and liver tissues and blood samples were collected for further analysis. The sham-operated control and peptide-treated groups underwent the same sampling procedure without ischemia.

Blood serum was obtained by centrifuging mouse blood samples at 3000 rpm for 15-20 minutes at 4 °C. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, which are indicators of liver function, were measured using a Chemray 800 chemical analyzer (Rayto, Shenzhen, China). The extent of ischemia-reperfusion injury was assessed using hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained liver tissues. Images from three random fields per slide were captured using a light microscope.

Paraffin-embedded tissue and cell samples were stained for apoptosis using a propidium iodide/hoechst33342 double-staining kit (K2003; ApexBio Technology, TX, United States) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (K1134; ApexBio Technology, TX, United States) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Paraffin-embedded tissue and cell samples were analyzed using the antibodies against Ki67 (ab16667; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), Ly6G (GB12229, Servicebio, Wuhan, China), F4/80 (GB12027-100, Servicebio, Wuhan, China).

Mouse hepatocyte AML12 cells were obtained from Fuheng Cell Center, Shanghai, China (FH0338). The cells were propagated in AML12 complete medium (FH-AML12, Fuheng, Shanghai, China) under sterile conditions at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured every 1-2 days to maintain viability and to prepare for experimental protocols.

To simulate ischemia-reperfusion injury, AML12 cells were cultured in glucose- and serum-free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium/nutrient mixture F-12 media and incubated under hypoxic conditions (94% N2, 5% CO2, and 1% O2) at

Cell viability was assessed using the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Share-bio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. AML12 cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. When cells reached 70%-80% confluency, they were pretreated with peptides at varying concentrations (1, 3, 10, 30, or 100 μmol/L) at 37 °C for 1 hours before hypoxia induction. After treatment, peptides were replaced with glucose- and serum-free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium/nutrient mixture F-12 medium, and cells were subjected to H/R treatment. Two hours before the end of reoxygenation, 10 μL of the CCK-8 reagent was added to each well. The cells were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 2 hours, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. Based on the dose-response results from this assay, 10 μmol/L was selected for all subsequent experiments as it represented the minimal concentration that produced the maximal protective effect.

Proteins from AML12 cells were extracted using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. Protein concentrations were quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (SB-WB013, Share-bio, Shanghai, China). The Samples were mixed with 6 × loading buffer (P0015F, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and denatured by boiling at 95 °C for 5 minutes. After cooling on ice, the samples were separated on Bis-Tris pre-cast gels (SB-FP11010, Share-bio, Shanghai, China) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (FFP71). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 1 hour, washed three times with Tris-buffered saline with Tween buffer (10 minutes each), and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:1000, 9661, CST, MA, United States), anti-Bcl-2 (1:1000, 182858, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (anti-PCNA, 1:1000, 2586S, CST, MA, United States), anti-Jun N-terminal kinase (anti-JNK, 1:1000, 4668, CST, MA, United States), anti-p-JNK (1:1000, sc-7345, Santa Cruz), and anti-β-actin (1:2000, EM21002, HuaBio, Zhejiang, China). After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and protein expression was visualized using a Tanon-5200 chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Band intensities were quantified using the ImageJ software and normalized to β-actin expression levels.

All data were derived from at least three independent experiments. Quantification of fluorescently stained cells and western blot protein expression was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.26). Statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 10. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Differences between two groups were analyzed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. For multi-group comparisons, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (for all pairwise comparisons) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test (for comparisons at specific time points or conditions) was applied as appropriate. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on liver samples from six liver transplant patients before and after transplantation, revealing a differential expression profile of polypeptides associated with human liver transplantation (Figure 1A). A heatmap indicated distinct differences in polypeptide expression before and after transplantation (Figure 1B). A total of 40718 peptides were detected, of which 463 exhibited significant differential expression, defined as a fold-change of at least 1 and a P value below 0.05. Among these, 83 peptides were downregulated and 380 were upregulated (Figure 1C). A volcano plot illustrated the distribution of the upregulated and downregulated peptides (Figure 1D). The length of these peptides varied significantly, with the majority ranging from 13 to 17 amino acids (Figure 1E). Further analysis of their MW and pI values revealed that their MWs fell between 1.2 and 1.8 kDa, with downregulated peptides primarily concentrated between 1.2-1.6 kDa and upregulated peptides between 1.4-1.8 kDa and 2.2-2.4 kDa (Figure 1F). The pI values ranged predominantly between 4-7 and 8-10 (Figure 1G). The relationship between MW and pI distribution was further analyzed, identifying five distinct peptide clusters, especially those with pI values concentrated around 4, 6, 7, 8, and 10 (Figure 1H). We screened several differential peptides and analyzed the distribution of their basic properties.

Initially, downregulated peptides were screened based on their degree of differential expression compared to pre-transplant livers (log ratio < -2, P < 0.03), resulting in the selection of 22 peptides from the 83 downregulated peptides (Table 1). Subsequently, secondary screening was conducted based on central distribution parameters, including MW (1.2-1.6 kDa), pI (4-7 or 8-10), and peptide lengths (13-17 amino acids). Several studies have shown that peptides often have biological roles that are similar to those of their precursor proteins. Literature reviews have identified precursor proteins of peptides potentially associated with HIRI, enabling the selection of peptides likely to alleviate HIRI. Therefore, based on our literature review, we identified that peptide 9 (‘AVPEGFVIPRGNVL’), which we designate here as HLTP1, is derived from nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT). NAMPT has been implicated in HIRI, as treatment with its inhibitor FK866 has been shown to ameliorate liver injury and suppress inflammation in mice[18].

The chemical formula of HLTP1 was determined using the All Peptide Biology website (https://www.allpeptide.com/jiegotu.html), and its structure was depicted using ChemDraw software (Figure 2A). Sequence comparison of the precursor protein NAMPT from different species using National Center for Biotechnology Information revealed the highly conserved nature of HLTP1 in humans, rats and mice (Figure 2B). Subsequently, we chemically synthesized HLTP1, added the membrane-penetrating amino acid sequence – ‘GRKKRRQRRRPPQQ’ to the N-terminus of HLTP1 and performed mass spectrometry to ensure its purity of over 97% (Figure 2C and D). We also added a fluorescent tag of fluorescein isothiocyanate to the N-terminus of the membrane-penetrating sequence and synthesized the sequence ‘FITC-acp-GRKKRRQRRRPPQAVPEGFVIPRGNVL’, which was solubilized with double distilled water and added to AML12 cells, and found that HLTP1 could enter the cells rapidly and stay mostly in the cytoplasm and a little in the nucleus (Figure 2E).

To evaluate the potential of HLTP1 to mitigate HIRI, a mouse model of ischemia-reperfusion injury was established. Peptides were administered via tail vein injection 1 hour prior to surgery. The left and middle lobes of the liver were clamped using microvascular clips for 60 minutes, followed by reperfusion for 24 hours before humane euthanasia for sample collection (Figure 3A). HLTP1 was found to significantly mitigate HIRI. Macroscopic examination showed severe congestion and swelling in untreated mouse livers, which were absent in the HLTP1-treated livers (Figure 3B). HE staining revealed reduced hepatocyte necrosis, vacuolisation and sludge in HLTP1-treated livers (Figure 3C). Suzuki’s scores of HE staining results quantified this result. Serum ALT and AST levels were significantly reduced following HLTP1 treatment (Figure 3D and E).

Given the above experimental results, we further explored the capability of HLTP1 to attenuate HIRI. TUNEL staining demonstrated a marked reduction in apoptotic cells in HLTP1-treated livers (Figure 3F and G). Ly6G and F4/80 staining of the liver demonstrated that HLTP1 significantly reduced the expression of Ly6G and F4/80, suggesting that HLTP1 reduced the infiltration of hepatic neutrophils and mononuclear macrophages (Figure 3H and I). Serum levels of interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α also showed that HLTP1 significantly reduced the levels of inflammatory mediators in the liver (Figure 3J and K). These results suggested that HLTP1 alleviates HIRI by decreasing apoptosis and inflammatory cell infiltration in the liver.

The potential of HLTP1 to attenuate HIRI was investigated through a series of in vivo experiments, and its role was validated through in vitro experiments. The effect of HLTP1 on the viability of AML12 hepatocytes was evaluated using the CCK-8 assays. Under normal conditions, HLTP1 enhanced AML12 cell viability without causing cytotoxicity (Figure 4A, left). Following H/R treatment, pre-treatment with HLTP1 at 10 μmol/L significantly improved cell survival in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A, right). Additionally, western blotting revealed that HLTP1 decreased the expression of cleaved-caspase-3 and increased the level of Bcl-2 (Figure 4B), and TUNEL staining suggested that HLTP1 reduced the number of apoptotic cells after H/R. TUNEL staining also suggested that HLTP1 reduced the number of apoptotic cells following H/R treatment (Figure 4C), suggesting that HLTP1 could inhibit apoptosis. In addition, western blotting confirmed that HLTP1 promoted PCNA expression in AML12 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4D). Cellular immunofluorescence for Ki67 showed that HLTP1 significantly increased Ki67 expression in AML12 cells (Figure 4E), indicating that HLTP1 promoted proliferation. Consequently, HLTP1 has the potential to counteract HIRI by promoting hepatocyte proliferation and attenuating apoptosis in vitro.

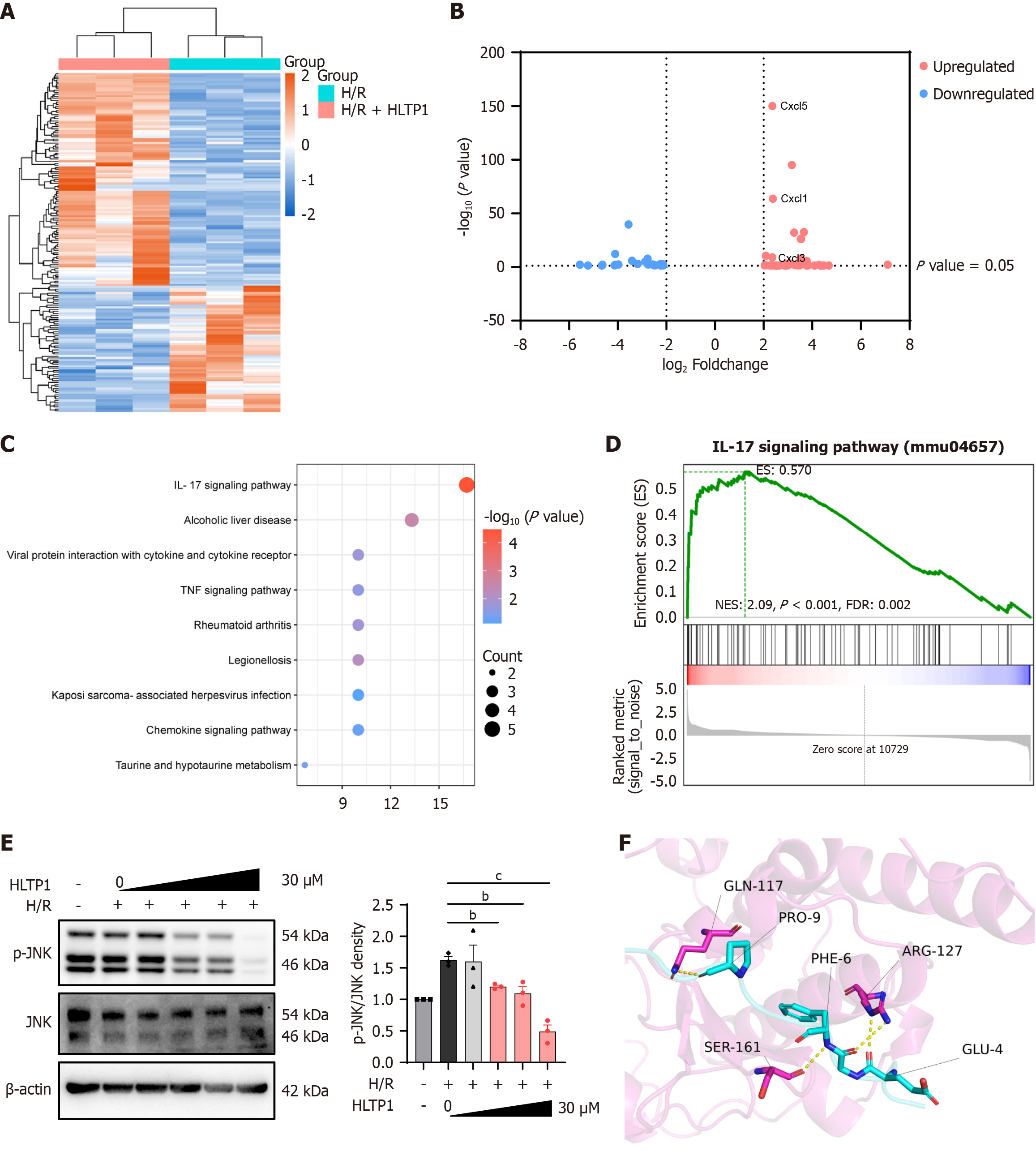

To ascertain the precise mechanism by which HLTP1 attenuates HIRI, RNA-Seq analysis was conducted at the cellular level. We sought to compare the expression levels of HLTP1 in the presence and absence of H/R model conditions. The heatmap shows significant differences in gene expression between the two groups (Figure 5A). A volcano plot showing the distribution of upregulated and downregulated genes (log ratio < -2, P < 0.05; Figure 5B). KEGG analysis of the RNA-seq data indicated that HLTP1 might act in the IL-17 signaling pathway (Figure 5C). We performed gene set enrichment analysis of KEGG, which showed a significant difference in the IL-17 signaling pathway with P < 0.001 and false discovery rate < 0.002 (Figure 5D). The IL-17 pathway and related genes may be involved in the proinflammatory mechanism of HIRI[19]. Consequently, we verified the effects of HLTP1 on the IL-17 signaling pathway and its specific targets by western blotting. Western blotting results confirmed that HLTP1 primarily suppressed JNK phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5E). AlphaFold3 was used to predict interactions between HLTP1 and JNK proteins, and PyMOL v2.3.4 analysis identified hydrogen bond-forming amino acid pairs (Figure 5F). PRODIGY analysis estimated the binding affinity between HLTP1 and JNK to be -9.1 kcal/mol. The predicted results suggested that HLTP1 interacts with JNK to inhibit its phosphorylation and consequently mitigate hepatocyte apoptosis.

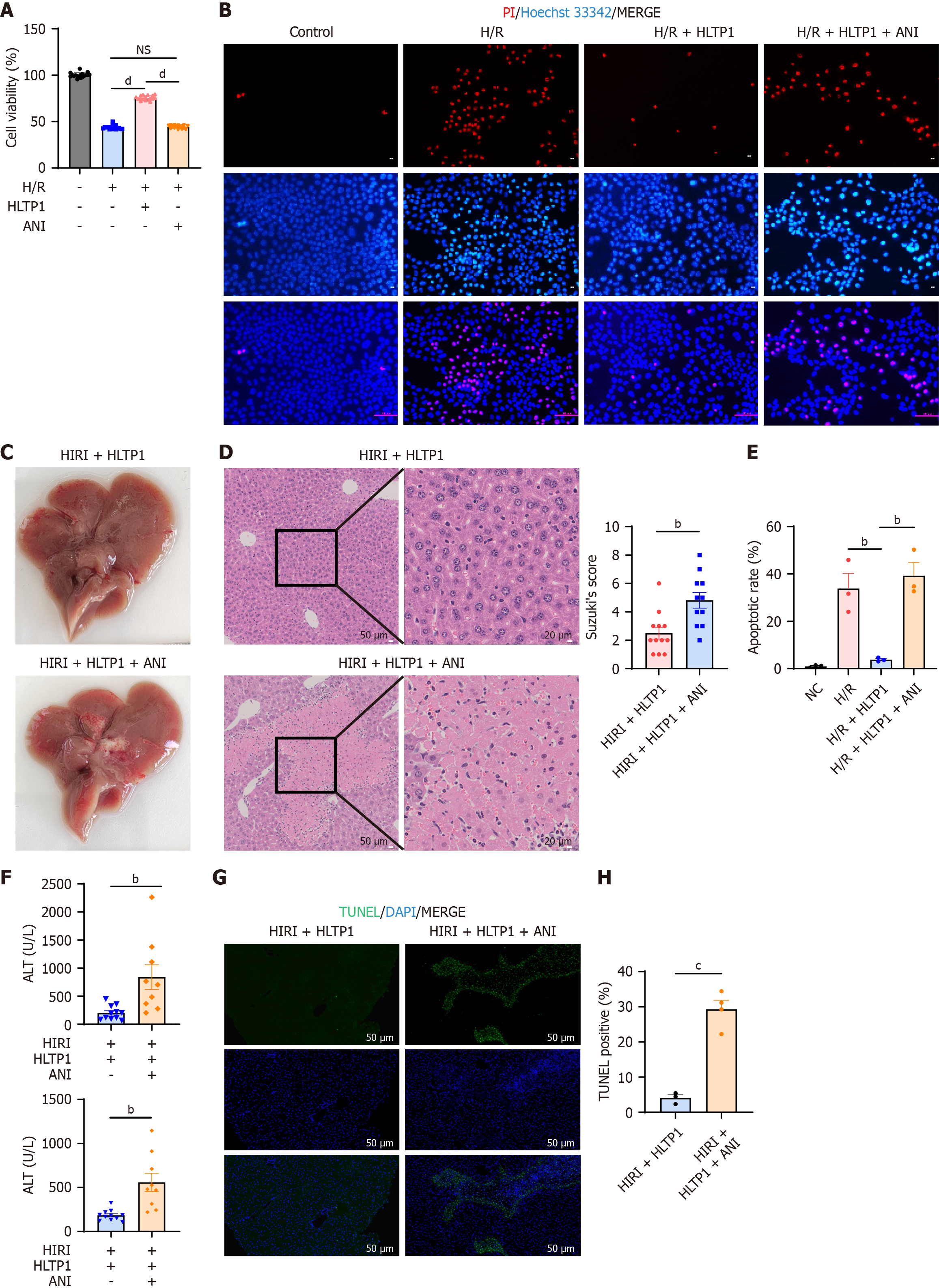

Given the significant inhibition of JNK phosphorylation exhibited by HLTP1, rescue experiments were performed using JNK agonists both in vivo and in vitro. Anisomycin (ANI, a JNK agonist, promotes JNK phosphorylation) was used in rescue experiments to validate HLTP1’s mechanism. Pre-treatment with ANI attenuated HLTP1’s ability to enhance AML12 cell viability following H/R (Figure 6A). Propidium iodide/Hoechst33342 co-staining indicated that ANI counteracted HLTP1’s apoptosis-reducing effects (Figure 6B). When administered in vivo, ANI reversed the protective effects of HLTP1 on HIRI. This was evidenced by an increase in liver congestion and swelling (Figure 6C), and the presence of hepatocyte necrosis, vacuolization and sludge in HE staining (Figure 6D). Furthermore, ANI administration resulted in elevated ALT/AST levels and an increase in apoptotic cells (Figure 6E and F) on TUNEL staining (Figure 6G and H). Overall, the results of rescue experiments indicated that HLTP1 inhibited JNK phosphorylation to attenuate hepatocyte apoptosis and mitigate HIRI.

HIRI is a significant contributor to complications, morbidity, and mortality following liver resection and transplantation[20]. Therefore, developing effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of HIRI is paramount. This study utilized LC-MS/MS was used to identify the changes in the peptide pool during human liver transplantation. By analyzing six paired liver samples collected before and after transplantation, 380 downregulated and 83 upregulated peptides were identified. Among these, we discovered a novel peptide, HLTP1, with potential clinical applications. HLTP1 attenuated HIRI by reducing apoptosis through inhibition of JNK phosphorylation. This study is the first to investigate alterations in the human hepatic peptidome during liver transplantation, thus offering innovative insights. The screened peptides were of human origin, enhancing their potential for clinical applications. In addition, we effectively leveraged LC-MS/MS and RNA-seq technologies to identify HLTP1 and explore its potential mechanisms of action, thereby ensuring a comprehensive approach.

Recent studies have reported the efficacy of various peptides for mitigating HIRI in animal models. For instance, Li et al[21] demonstrated that liraglutide alleviates HIRI by regulating glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor, preventing macrophage polarization towards an inflammatory state. Bao et al[22] identified liver-derived peptide 2 as a novel peptide that prevents HIRI by inhibiting inflammation, apoptosis, and autophagy. Li et al[23] showed that the short peptide Ac2-26 derived from Annexin A1 reduces oxidative stress and inhibits mitochondrial apoptosis to ameliorate HIRI. However, no prior research has focused on identifying human-derived peptides to address HIRI in liver transplantation patients. Liraglutide is a therapeutic agent originally derived from exendin-4 in Gila monster venom. It has been structurally modified to prolong its half-life, and is primarily used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity[24]. Ac2-26 is a peptide derived from Annexin A1, a potent endogenous anti-inflammatory protein. It represents the minimal, rationally designed core fragment responsible for the protein’s bioactivity and is under investigation for the treatment of various inflammatory diseases[25]. However, HLTP1 is a naturally occurring peptide derived directly from human liver tissue. Without the need for any modification, it demonstrates a direct protective effect against HIRI.

IL-17 signaling activates inflammatory transcription factors to induce gene expression via nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathways [p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and JNK][26]. Consistently, IL-17-induced genes show enrichment of NF-κB and activator protein-1 binding sites in their proximal promoters, and blockade of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways typically impairs the induction of IL-17-induced target genes[27]. The MAPK signaling pathway, a critical mediator of cellular responses, regulates processes such as growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and biochemical reactions[28]. IL-17 activates the MAPK pathways, which include ERK, p38 and JNK. Notably, the MAPK cascade is linked to ischemia-reperfusion injuries in various organs, particularly through its three main family members, JNK, ERK, and p38-MAPK[28]. During HIRI, p38, JNK, and ERK are activated in specific cells, initiating a series of physiological and pathological responses[29]. Activated JNK plays a pivotal roles in apoptosis[30]. JNK, in particular, directly impacts mitochondrial function, leading to cell death[29,31]. Qiu et al[31] and Zhu et al[32] highlighted molecules such as dual specificity phosphatase 12 and yes-associated protein as potential therapeutic agents targeting JNK to prevent apoptosis and combat HIRI.

Peptide composition and properties in the human liver change under stress conditions[12] such as HIRI, an inevitable pathophysiological process during liver transplantation. Stress profoundly alters the hepatic peptidome. No previous studies have explored whether peptides derived from human liver transplantation can mitigate HIRI. Using LC-MS/MS and peptidomics, we identified distinct peptide expression patterns before and after transplantation and discovered the novel peptide HLTP1, which demonstrated protective effects against HIRI.

To validate HLTP1’s function, we conducted in vitro and in vivo experiments were conducted. A mouse model with 70% HIRI and a hepatocyte H/R assay was used to simulate human HIRI. HLTP1 exhibited hepatoprotective effects, as evidenced by the reduced serum ALT and AST levels and histological improvements in HE-stained samples. TUNEL staining revealed decreased apoptosis in the HLTP1-treated liver tissue. Furthermore, CCK-8 assays confirmed HLTP1’s non-toxicity of in AML12 cells, enhancing their viability. Increased expression of PCNA and Ki67 indicated that HLTP1 promoted AML12 cell proliferation. Moreover, elevated Bcl-2 expression and reduced cleaved caspase-3 levels suggested anti-apoptotic effects.

To investigate the underlying mechanisms, we integrated RNA-seq data with HLTP1 phenotypic results to identify the IL-17 signaling pathway as a potential target. In particular, HLTP1 significantly inhibits JNK phosphorylation. This was confirmed through rescue experiments using ANI, a JNK agonist. ANI abrogated HLTP1’s effects on AML12 cell viability in vitro. HLTP1 Lost its hepatoprotective effects against HIRI when ANI was introduced in vivo. Based on these findings, we propose that HLTP1 attenuates HIRI by reducing apoptosis through inhibition of JNK phosphorylation.

While our data robustly demonstrate that HLTP1 treatment leads to the specific inhibition of JNK phosphorylation, the exact molecular initiation point of this effect requires further clarification. To explore whether a direct interaction could contribute, we performed computational molecular docking. This in silico analysis suggested the potential for HLTP1 to bind directly to JNK, with a favorable binding energy of -9.1 kcal/mol. While this computational result provides a plausible structural hypothesis, it is important to note that it does not constitute definitive proof of a direct interaction in a biological context. We therefore hypothesize that the inhibition of JNK phosphorylation by HLTP1 could be mediated, at least in part, by such a direct binding mechanism. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that HLTP1 also acts upstream by modulating a cell surface receptor or other signaling components. Consequently, future work is essential to experimentally validate this interaction using techniques such as surface plasmon resonance or co-immunoprecipitation, and to delineate the precise mechanistic steps.

Our findings highlight a novel human-derived peptide that offers a promising strategy for HIRI prevention and treatment, potentially improving outcomes in liver transplantation patients. This may reduce HIRI-associated complications and expand the use of marginal livers, addressing the imbalance between liver transplant supply and demand. Our work is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to demonstrate a successful peptide drug discovery pipeline originating from peptidomic profiling of clinical liver transplantation samples. This approach differs fundamentally from previous strategies that focused on modifying known proteins or testing exogenous compounds. The discovery of HLTP1 not only reveals a new biological mechanism of intrinsic protection but also opens a new avenue for therapeutic development in solid organ transplantation by leveraging the body’s own ‘pharmacopeia’ of signaling peptides. Future studies should validate HLTP1’s effects in other species and in human models to confirm its translational potential. Additionally, HLTP1’s pharmacokinetic profile must be thoroughly evaluated to facilitate its clinical application. Given its relatively simple mechanism, further exploration of HLTP1’s broader effects and pathways is warranted.

However, this study had some limitations. As HLTP1 is a novel peptide, its pharmacological profile is not yet well defined, necessitating further studies to clarify its pharmacokinetics. Additionally, HLTP1’s protective effects against HIRI have only been validated in mice and AML12 cells, limiting its generalizability across species and cell types. The translating of HLTP1 into clinical use requires extensive further research. Finally, while HLTP1 was found to inhibit JNK phosphorylation, the precise mechanism by which it directly regulates JNK expression/activation or acts via upstream pathways remains unresolved.

Looking forward, a defined translational pathway is essential to advance HLTP1 toward clinical application. Our immediate future work will prioritize a comprehensive safety and pharmacokinetic profiling. This includes systematic toxicity studies in relevant animal models to establish a safety window, and thorough stability assessments to guide optimal formulation development. Furthermore, elucidating the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties of HLTP1 is critical for predicting human pharmacokinetics and determining appropriate dosing regimens. Success in these preclinical studies will pave the way for investigational new drug-enabling studies and, ultimately, phase I clinical trials to evaluate the safety and tolerability of HLTP1 in human volunteers. This structured approach will be vital for realizing the therapeutic promise of HLTP1 in preventing HIRI in transplant patients.

HLTP1 was the first bioactive micro peptide identified in human liver transplantation. It attenuates HIRI by reducing apoptosis through the inhibition of JNK phosphorylation. Beyond its demonstrated efficacy, HLTP1, as a human-derived small peptide, presents several distinct translational advantages. First, its endogenous nature suggests low immunogenicity[33], potentially offering superior biocompatibility and a more favorable safety profile for long-term therapy compared to exogenous biologics or synthetically modified peptides. Second, the mechanism of HLTP1, precise inhibition of JNK phosphorylation, targets a core pathway of ischemia-reperfusion injury. This specificity, as opposed to broad-spectrum antioxidative or anti-inflammatory strategies, may minimize off-target effects and enhance therapeutic precision. Finally, its small peptide characteristics facilitate cost-effective scalable production via chemical synthesis. This property also provides flexibility in clinical delivery; for instance, localized administration or liver-targeted delivery systems could achieve high intrahepatic concentrations, potentially maximizing efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects. These attributes collectively position HLTP1 as a novel and highly promising clinical candidate for preventing HIRI.

In summary, this study identifies HLTP1 as the first human liver transplantation-derived micropeptide that protects against HIRI. We demonstrate that HLTP1 directly targets the JNK pathway, inhibiting phosphorylation and subsequent apoptosis to shift the liver toward a minor injured state. Its human origin ensures low immunogenicity, while its small size and targeted mechanism facilitate production and precision therapy. HLTP1 thus represents a novel, translationally promising candidate, and our work establishes a new paradigm for discovering endogenous peptide therapeutics in organ transplantation.

| 1. | Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, Gluud LL, Arrese M, Bugianesi E, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:388-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 167.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hu XH, Chen L, Wu H, Tang YB, Zheng QM, Wei XY, Wei Q, Huang Q, Chen J, Xu X. Cell therapy in end-stage liver disease: replace and remodel. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhai Y, Petrowsky H, Hong JC, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury in liver transplantation--from bench to bedside. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:79-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dar WA, Sullivan E, Bynon JS, Eltzschig H, Ju C. Ischaemia reperfusion injury in liver transplantation: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Liver Int. 2019;39:788-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Peng Y, Yin Q, Yuan M, Chen L, Shen X, Xie W, Liu J. Role of hepatic stellate cells in liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Immunol. 2022;13:891868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ito Y, Hosono K, Amano H. Responses of hepatic sinusoidal cells to liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1171317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stravitz RT, Lee WM. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2019;394:869-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 90.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ito T, Naini BV, Markovic D, Aziz A, Younan S, Lu M, Hirao H, Kadono K, Kojima H, DiNorcia J 3rd, Agopian VG, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Kaldas FM. Ischemia-reperfusion injury and its relationship with early allograft dysfunction in liver transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:614-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Masior Ł, Grąt M. Methods of Attenuating Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu H, Man K. New Insights in Mechanisms and Therapeutics for Short- and Long-Term Impacts of Hepatic Ischemia Reperfusion Injury Post Liver Transplantation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muttenthaler M, King GF, Adams DJ, Alewood PF. Trends in peptide drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:309-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 1208] [Article Influence: 241.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anapindi KDB, Romanova EV, Checco JW, Sweedler JV. Mass Spectrometry Approaches Empowering Neuropeptide Discovery and Therapeutics. Pharmacol Rev. 2022;74:662-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sharma K, Sharma KK, Sharma A, Jain R. Peptide-based drug discovery: Current status and recent advances. Drug Discov Today. 2023;28:103464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lyapina I, Ivanov V, Fesenko I. Peptidome: Chaos or Inevitability. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:13128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Richardson J, Zhang Z. Fully Unattended Online Protein Digestion and LC-MS Peptide Mapping. Anal Chem. 2023;95:15514-15521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jia K, Zhang Y, Luo R, Liu R, Li Y, Wu J, Xie K, Liu J, Li S, Zhou F, Li X. Acteoside ameliorates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury via reversing the senescent fate of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and restoring compromised sinusoidal networks. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:4967-4988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qin X, Tan Z, Li Q, Zhang S, Hu D, Wang D, Wang L, Zhou B, Liao R, Wu Z, Liu Y. Rosiglitazone attenuates Acute Kidney Injury from hepatic ischemia-reperfusion in mice by inhibiting arachidonic acid metabolism through the PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway. Inflamm Res. 2024;73:1765-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lu J, Wang M, Chen Y, Song H, Wen D, Tu J, Guo Y, Liu Z. NAMPT inhibition reduces macrophage inflammation through the NAD+/PARP1 pathway to attenuate liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Chem Biol Interact. 2023;369:110294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tan S, Lu X, Chen W, Pan B, Kong G, Wei L. Analysis and experimental validation of IL-17 pathway and key genes as central roles associated with inflammation in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Sci Rep. 2024;14:6423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tong G, Chen Y, Chen X, Fan J, Zhu K, Hu Z, Li S, Zhu J, Feng J, Wu Z, Hu Z, Zhou B, Jin L, Chen H, Shen J, Cong W, Li X. FGF18 alleviates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury via the USP16-mediated KEAP1/Nrf2 signaling pathway in male mice. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li SL, Wang ZM, Xu C, Che FH, Hu XF, Cao R, Xie YN, Qiu Y, Shi HB, Liu B, Dai C, Yang J. Liraglutide Attenuates Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Modulating Macrophage Polarization. Front Immunol. 2022;13:869050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bao Q, Wang Z, Cheng S, Zhang J, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Cheng D, Guo X, Wang X, Han B, Sun P. Peptidomic Analysis Reveals that Novel Peptide LDP2 Protects Against Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2023;11:405-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li W, Jiang H, Bai C, Yu S, Pan Y, Wang C, Li H, Li M, Sheng Y, Chu F, Wang J, Chen Y, Li J, Jiang J. Ac2-26 attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice via regulating IL-22/IL-22R1/STAT3 signaling. PeerJ. 2022;10:e14086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Knudsen LB, Lau J. The Discovery and Development of Liraglutide and Semaglutide. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 626] [Article Influence: 89.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sousa SO, Santos MRD, Teixeira SC, Ferro EAV, Oliani SM. ANNEXIN A1: Roles in Placenta, Cell Survival, and Nucleus. Cells. 2022;11:2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Amatya N, Garg AV, Gaffen SL. IL-17 Signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:310-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 603] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li X, Bechara R, Zhao J, McGeachy MJ, Gaffen SL. IL-17 receptor-based signaling and implications for disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1594-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 58.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen Z, Hu F, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Wang T, Kong C, Hu H, Guo J, Chen Q, Yu B, Liu Y, Zou J, Zhou J, Qiu T. Ubiquitin-specific protease 29 attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by mediating TGF-β-activated kinase 1 deubiquitination. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1167667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yu B, Zhang Y, Wang T, Guo J, Kong C, Chen Z, Ma X, Qiu T. MAPK Signaling Pathways in Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:1405-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang S, Tang J, Sun C, Zhang N, Ning X, Li X, Wang J. Dexmedetomidine attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced apoptosis via reducing oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;117:109959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Qiu T, Wang T, Zhou J, Chen Z, Zou J, Zhang L, Ma X. DUSP12 protects against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury dependent on ASK1-JNK/p38 pathway in vitro and in vivo. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134:2279-2294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhu S, Wang X, Chen H, Zhu W, Li X, Cui R, Yi X, Chen X, Li H, Wang G. Hippo (YAP)-autophagy axis protects against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury through JNK signaling. Chin Med J (Engl). 2024;137:657-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dingman R, Balu-Iyer SV. Immunogenicity of Protein Pharmaceuticals. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108:1637-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/