Published online Jan 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.112395

Revised: August 27, 2025

Accepted: November 24, 2025

Published online: January 14, 2026

Processing time: 171 Days and 1.8 Hours

Despite societal guidelines recommending targeted screening for Barrett’s eso

To assess patients’ self-management and help-seeking behavior for GERS.

This cross-sectional study collected data from the Dutch general population aged 18-75 years between January and April 2023 using a web-based survey. The sur

Of the 18156 invited individuals, 3214 participants (17.7%) completed the survey, of which 1572 participants (48.9%) reported GERS. Of these, 904 participants (57.5%) had never consulted a primary care provider for these symptoms, of which 331 participants (36.6%) reported taking OTC acid suppressant therapy in the past six months and 100 participants (11.1%) fulfilled the screening criteria for BE and EAC according to the European Society of Gas

The population fulfilling the screening criteria for BE and EAC is incompletely identified, suggesting potential underutilization of medical consultation. Raising public awareness of GERS as a risk factor for EAC is needed.

Core Tip: The majority of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) had never undergone prior endoscopic screening. An understanding of patients’ self-management and help-seeking behavior is essential to improve EAC screening adherence. Almost half of the 3214 participants who completed the survey reported gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS). Over half of the 1572 participants who reported GERS had never consulted a primary care provider for these symptoms whereas over one-third reported taking ‘over-the-counter’ acid suppressant therapy and approximately 11% fulfilled the screening criteria for EAC. Our findings highlight the importance to encourage individuals with long-term GERS to consult a primary care provider.

- Citation: Huibertse LJ, Sijben J, Peters Y, Siersema PD. Self-management and help-seeking behavior for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: A population-based survey. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(2): 112395

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i2/112395.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.112395

Over the past four decades, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has risen faster than any other cancer type in the Western world[1]. The global burden of EAC, and its precursor lesion Barrett’s esophagus (BE), is still increasing[1]. Despite medical advancements, the 5-year survival rate of EAC remains low, primarily due to the advanced stage of the disease at diagnosis, limiting treatment options[2]. This emphasizes the importance of early detection through effective screening strategies to reduce the incidence and mortality associated with EAC.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a well-established risk factor for BE and EAC[3]. However, while various professional societies recommend targeted screening for BE and EAC in individuals with GERD, current screening prac

Although GERD is a major risk factor for BE and EAC, it is neither a sensitive nor a specific risk factor. Approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with EAC do not report a prior history of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS)[4]. Moreover, GERS are prevalent, affecting 20%-30% of the general population in Western countries[5]. Studies suggest that only 10%-15% of those at risk for BE and EAC indeed undergo endoscopic screening[6].

The referral pathway for further investigation is complex, depending on both individuals’ ability to recognize persis

Current guidelines recommend lifestyle and dietary interventions as first-line treatment for GERS[9]. If these inter

This study aimed to investigate: (1) The prevalence of and participant characteristics associated with GERS in the Dutch general population; (2) The percentage of participants with GERS who had ever consulted a PCP for these symptoms and participant characteristics associated with PCP consultations; (3) Self-management and help-seeking behavior of participants with GERS; and (4) The percentage of participants with GERS who had never consulted a PCP for these symptoms but fulfilling the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline screening criteria for BE and EAC.

This cross-sectional study collected data from the Dutch general population between January and April 2023 using a web-based survey. Ethics approval was provided by the Regional Ethics Committee (METC) Oost-Nederland, the Netherlands (reference number: 2022-13720). Participants provided online informed consent prior to the start of the survey. The study protocol was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT05689918). The survey was conducted in accordance with The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement[10].

Eligible participants were residents in the Netherlands registered in the Personal Records Database aged 18-75 years with access to the survey using a cell phone, tablet, or computer. Simple random sampling was performed in the Dutch population registry by Statistics Netherlands to select individuals within the target age group (Supplementary Figure 1). The corresponding personal identification numbers were provided to the National Office for Identity Data. On the basis of the personal identification numbers, address details were provided to the researchers by the National Office for Identity Data. The chance of being selected was equal for all individuals, without stratification by age group. Selected individuals received an invitation letter through postal mail containing a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) and corresponding Quick Response (QR) code to access the survey, which was linked to a unique participant identification number to prevent duplicate entries. To assess representativeness, we compared the distribution of age, gender, educational level, and migration background in our study sample to data from the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) (Supplemen

The survey included validated questionnaires and questionnaires reviewed by the authors involved in this study. The survey was subsequently piloted in cognitive interviews among healthy volunteers (n = 7) and tested for technical functionality in the Castor Electronic Data Capture (EDC) platform (n = 3). The survey was divided into four sections (see below) and took approximately 10-15 minutes to complete. Participants directly entered data in Castor EDC. An English translation of the Dutch survey is available in the Supplementary Methods 1 in Supplementary material.

Section 1 (reflux disease questionnaire): This validated Dutch primary care questionnaire assessed the frequency and severity of GERS[11,12]. It comprises twelve questions rated on a six-point Likert-scale assessing heartburn, dyspepsia, and regurgitation over the past seven days.

Section 2 (GERS and help-seeking behavior): The second section included questions to investigate GERS onset and duration, and help-seeking behavior, including reasons for consulting or not consulting a PCP.

Section 3 (acid suppressive medication and self-management): In this section, participants answered questions about the use of acid suppressive medication, both prescribed and/or OTC, including type (e.g., PPIs, H2RAs, sucralfate, antacids, and homeopathic therapy), frequency, and duration, and reasons for taking medication without prescription.

Section 4 (sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics): Sociodemographic (i.e., age, gender, educational level, civil status, migration background, and family history of esophageal cancer or BE), lifestyle (i.e., smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, length, weight, and waist circumference), and clinical characteristics (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and self-reported esophageal findings) were collected in the last section of the survey. Participants’ postal codes were used to obtain the neighborhood socio-economic status (SES) scores as calculated by the CBS, ranging from -0.9 to 0.9, with 0 representing the Dutch average[13].

The first primary outcome measure was the prevalence of GERS assessed by the question: “Do you have symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation?” (yes, currently/yes, previously/no). Answer categories “yes, currently” and “yes, previously” were categorized into “yes”. The percentage of participants with GERS who had ever consulted a PCP for these symptoms was the second primary outcome measure. Secondary outcome measures were: (1) The use of acid suppressive medication and details among participants with GERS; (2) The (self-reported) diagnostic yield of gastroscopy among participants who had ever undergone a gastroscopy for GERS; and (3) The percentage of participants eligible for BE and EAC screening according to the ESGE Guideline among those who had never consulted a PCP for GERS. To determine whether participants were eligible for screening according to the ESGE Guideline, long-term GERS were defined as symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation for at least one day during the past week combined with experiencing these symptoms ≥ 5 years.

Sample size calculations were based on prior estimates of the prevalence of GERS (20%) in Western countries[5]. A sample size of 4719 was determined to be sufficient to estimate the prevalence of GERS with a confidence level of 99% and 1.5% margin of error. We sampled 18876 individuals based on an expected response rate of 25%. The actual response rate turned out to be 3214 participants (17.7%), which was sufficient to estimate the prevalence of GERS in the Dutch general population with a confidence level of 95% and 2% margin of error.

Descriptive statistics reported as n (%) were used to compare the participants with the Dutch population. Responses to open-ended questions were categorized into existing answer categories or into newly created ones.

Characteristics of participants with or without GERS and characteristics of participants who had ever or who had never consulted a PCP for these symptoms, were reported as means with SD (if data were normally distributed) or as medians with interquartile ranges (if data were non-normally distributed) for continuous variables and as n (%) for categorical variables.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics associated with (1) GERS; and (2) Consulting a PCP for GERS. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were reported. Participant characteristics were included in multivariable logistic regression analyses if significantly associated with the outcome of interest in univariable logistic regression analyses (P value < 0.05). Moreover, univariable logistic regression analyses were also used to examine the linearity assumption for continuous variables. If this assumption was not met, the variable was divided into categories.

We analyzed data using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 27.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, United States). Significance tests were two-sided and P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 18156 invited individuals, 3214 eligible participants (17.7%) completed the survey (Supplementary Figure 1). Participants were excluded if they did not provide informed consent (n = 71) or exceeded the target age range (n = 8). While gender distribution aligned with Dutch population statistics, the study sample overrepresented older individuals, those with higher educational levels, those with higher SES scores, and those with a Dutch background (Supplementary Table 1).

GERS were reported by 1572 of the 3214 participants (48.9%) (Table 1). Participants with an increased waist circumference were significantly more likely to have GERS compared with those with a normal waist circumference [odds ratio (OR) = 1.51 (95%CI: 1.06-2.14)]. Furthermore, participants with hypercholesterolemia were significantly more likely to have GERS compared with those without hypercholesterolemia [OR = 1.69 (95%CI: 1.05-2.73)]. Supplementary Table 2 shows the results of the univariable logistic regression analyses (only participant characteristics excluded from the multivariable model).

| Participants with GERS | Participants without GERS (n = 1584, 49.3%)1 | Participants with GERS vs participants without GERS, OR (95%CI) | |

| Age, years2 | |||

| 18-34 | 224 (14.8) | 300 (19.8) | Reference category |

| 35-54 | 461 (30.4) | 447 (29.5) | 0.896 (0.425-1.889) |

| 55-75 | 832 (54.8) | 768 (50.7) | 0.534 (0.256-1.114) |

| Gender2 | |||

| Female or non-binary | 783 (51.6) | 726 (47.9) | Reference category |

| Male | 734 (48.4) | 789 (52.1) | 0.720 (0.509-1.019) |

| Educational level3 | |||

| Lower | 292 (19.3) | 243 (16.1) | Reference category |

| Middle | 535 (35.3) | 525 (34.7) | 0.964 (0.607-1.531) |

| Higher | 689 (45.4) | 746 (49.3) | 0.888 (0.565-1.396) |

| Civil status3 | |||

| Living without a partner | 343 (22.6) | 417 (27.5) | Reference category |

| Living with a partner | 1173 (77.4) | 1097 (72.5) | 1.292 (0.864-1.933) |

| Migration background3 | |||

| Dutch background | 1417 (93.5) | 1439 (95.0) | |

| Western or non-Western background | 99 (6.5) | 75 (5.0) | |

| Waist circumference (cm)4,5 | |||

| Normal waist circumference | 456 (56.4) | 569 (70.8) | Reference category |

| Increased waist circumference | 353 (43.6) | 235 (29.2) | 1.513 (1.068-2.141) |

| Smoking behavior (pack-years), median (IQR)6 | 9.0 (17.00) | 7.5 (13.50) | 1.011 (0.998-1.023) |

| Alcohol consumption (units per week)7 | |||

| < 7 | 957 (73.3) | 980 (75.0) | |

| ≥ 7 | 349 (26.7) | 326 (25.0) | |

| Hypertension8 | |||

| No | 1185 (78.7) | 1273 (84.6) | Reference category |

| Yes | 321 (21.3) | 232 (15.4) | 1.174 (0.753-1.832) |

| Diabetes9 | |||

| No | 1405 (93.3) | 1446 (96.2) | Reference category |

| Yes | 101 (6.7) | 57 (3.8) | 0.853 (0.431-1.689) |

| Hypercholesterolemia10 | |||

| No | 1208 (80.3) | 1309 (87.1) | Reference category |

| Yes | 297 (19.7) | 194 (12.9) | 1.694 (1.051-2.731) |

| Family history of esophageal cancer11 | |||

| No or unknown | 940 (82.1) | 1047 (87.3) | Reference category |

| Yes | 205 (17.9) | 152 (12.7) | 0.870 (0.552-1.372) |

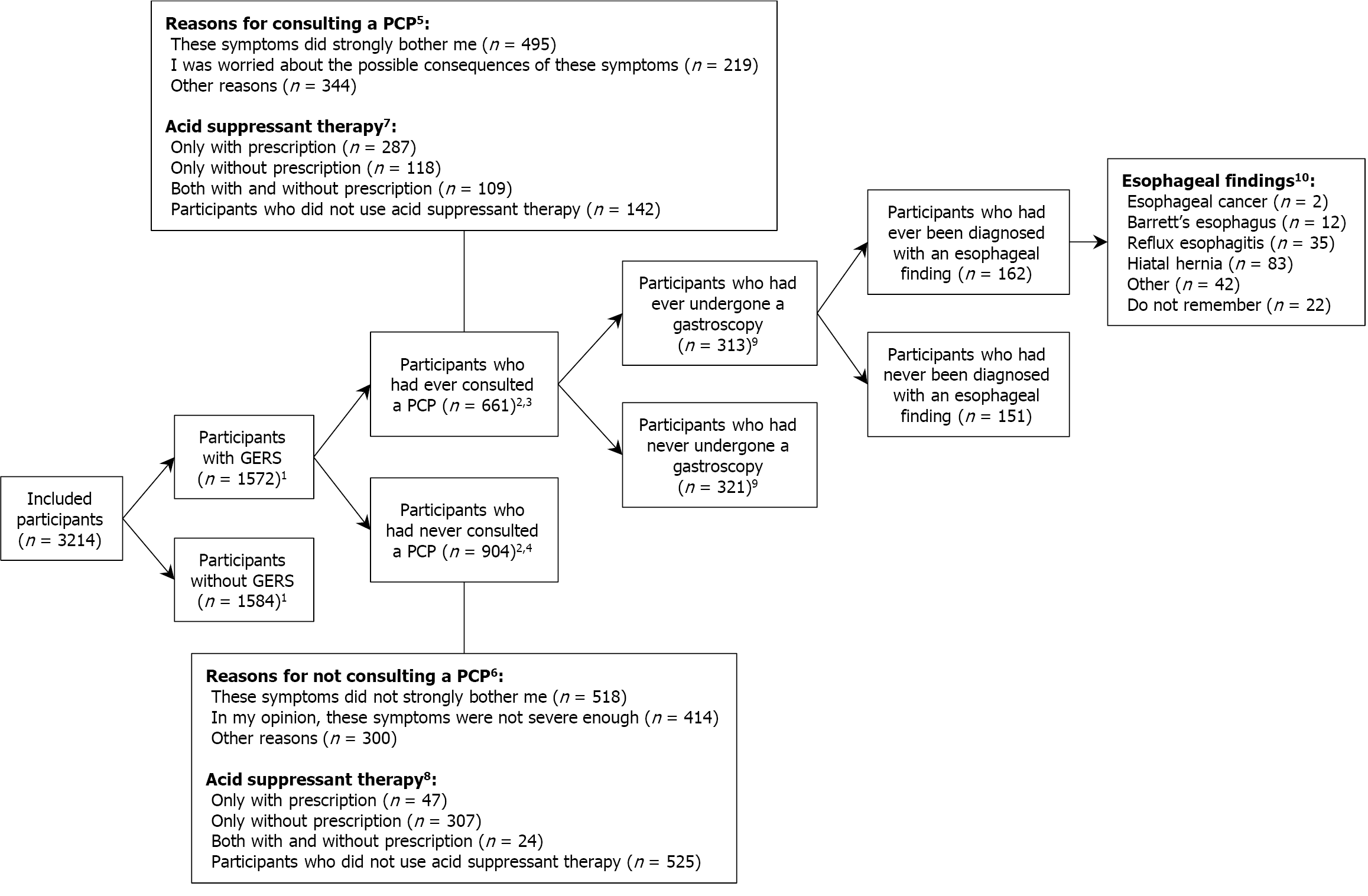

Table 2 shows that 661 participants with GERS (42.0%) had ever consulted a PCP for these symptoms whereas 904 participants (57.5%) had never. Participant characteristics associated with increased likelihood of PCP consultations included older age [35-54 years vs 18-34 years: OR = 1.53 (95%CI: 1.05-2.23); 55-75 years vs 18-34 years: OR = 2.24 (95%CI: 1.57-3.19)] and longer duration of GERS [1-5 years vs < 1 year: OR = 2.09 (95%CI: 1.57-2.79); 5-10 years vs < 1 year: OR = 2.65 (95%CI: 1.89-3.73); > 10 years vs < 1 year: OR = 4.82 (95%CI: 3.60-6.46)] (Table 2). Conversely, participants with middle or higher educational levels were significantly less likely to consult a PCP compared with those with lower educational levels [OR = 0.71 (95%CI: 0.52-0.97); OR = 0.58 (95%CI: 0.43-0.78), respectively]. Supplementary Table 3 shows the results of the univariable logistic regression analyses (only participant characteristics excluded from the multivariable model). As shown in Figure 1, the severity of discomfort due to GERS was an important indicator for consulting a PCP.

| Participants with GERS who had ever consulted a PCP (n = 661, 42.0%)1 | Participants with GERS who had never consulted a PCP (n = 904, 57.5%)1 | Participants with GERS who had ever consulted a PCP vs who had never consulted a PCP, OR (95%CI) | |

| Age, years2 | |||

| 18-34 | 54 (8.5) | 170 (19.3) | Reference category |

| 35-54 | 173 (27.2) | 288 (32.7) | 1.532 (1.053-2.230) |

| 55-75 | 410 (64.4) | 422 (48.0) | 2.244 (1.578-3.192) |

| Gender2 | |||

| Female or non-binary | 335 (52.6) | 448 (50.9) | |

| Male | 302 (47.4) | 432 (49.1) | |

| Educational level3 | |||

| Lower | 154 (24.2) | 138 (15.7) | Reference category |

| Middle | 234 (36.7) | 301 (34.2) | 0.715 (0.527-0.971) |

| Higher | 249 (39.1) | 440 (50.1) | 0.582 (0.432-0.784) |

| Civil status3 | |||

| Living without a partner | 139 (21.8) | 204 (23.2) | |

| Living with a partner | 498 (78.2) | 675 (76.8) | |

| Migration background3 | |||

| Dutch background | 594 (93.2) | 823 (93.6) | |

| Western or non-Western background | 43 (6.8) | 56 (6.4) | |

| Family history of esophageal cancer4 | |||

| No or unknown | 360 (79.6) | 580 (83.7) | |

| Yes | 92 (20.4) | 113 (16.3) | |

| Duration of GERS1, years | |||

| < 1 | 142 (21.5) | 415 (45.9) | Reference category |

| 1-5 | 169 (25.6) | 242 (26.8) | 2.099 (1.578-2.791) |

| 5-10 | 103 (15.6) | 109 (12.1) | 2.655 (1.890-3.730) |

| > 10 | 247 (37.4) | 138 (15.3) | 4.827 (3.602-6.469) |

| Age at onset GERS1, years | |||

| < 30 | 243 (36.8) | 367 (40.6) | |

| 30-50 | 262 (39.6) | 308 (34.1) | |

| > 50 | 156 (23.6) | 229 (25.3) |

Of the 1572 participants with GERS, 969 participants (61.6%) had experienced these symptoms < 5 years and 611 participants (38.9%) were < 30 years when first noticing these symptoms (Supplementary Table 4). The use of acid suppressive medication in the past six months was reported by 467 participants (29.7%) with prescription and 558 participants (35.5%) without prescription among the 1572 participants with GERS. Of the medications with prescription, PPIs were the most frequently prescribed (92.0%). Most participants reported taking the prescribed medications daily (69.6%) and < 5 years (44.3%). Of the medications without prescription, antacids were the most frequently used (60.8%). Most participants reported taking the OTC medications monthly (72.2%) and < 5 years (60.6%). In total, 904 of 1572 participants with GERS (57.5%) had never consulted a PCP for these symptoms (Supplementary Table 4). Of these, 247 participants (27.4%) had experienced these symptoms ≥ 5 years and 331 participants (36.6%) reported taking acid suppressive medication without prescription in the past six months. Of these OTC consumers, 21.4% reported taking it weekly or daily and 36.6% reported taking it ≥ 5 years. OTC PPIs accounted for 17.0% of the OTC acid suppressive medications among the 904 participants with GERS who had never consulted a PCP for these symptoms.

Of the 661 participants who had ever consulted a PCP for GERS, 313 participants (47.4%) had ever undergone a gas

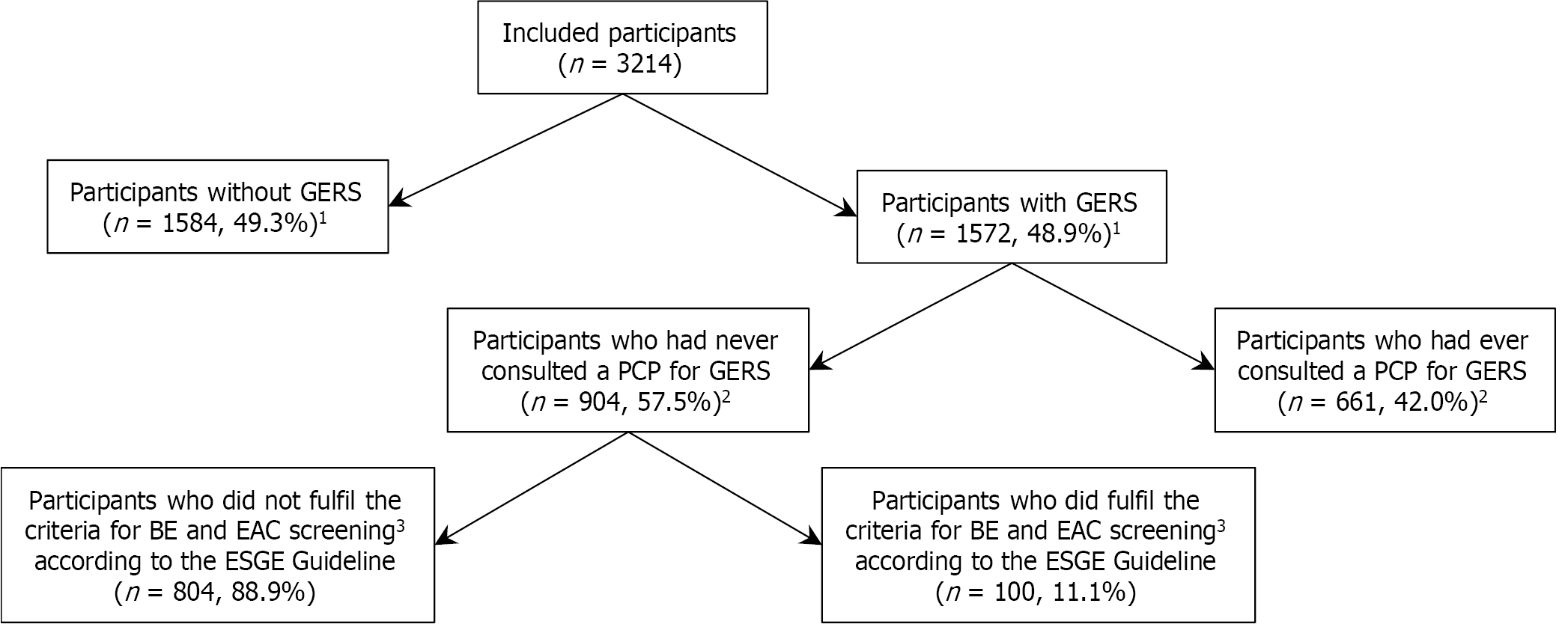

The ESGE Guideline suggests a screening strategy for BE and EAC that identifies the population at risk defined as individuals with a family history of BE or EAC, or as individuals with a prior history of long-term GERS, and at least one of the following additional risk factors for BE and EAC: (1) Age > 50 years; (2) Obesity; (3) History of smoking; and (4) Male gender. Of the 904 participants who had never consulted a PCP for GERS and thus had never undergone a gastroscopy, 100 participants (11.1%) fulfilled the criteria for BE and EAC screening according to the ESGE Guideline (Figure 2).

This population-based study demonstrated that 1572 participants (48.9%) reported GERS, with 904 participants (57.5%) having never consulted a PCP for these symptoms. Older participants and those with a longer duration of GERS were more likely to seek medical consultation. Remarkably, of the 904 participants who had never consulted a PCP for GERS, 36.6% reported using OTC acid suppressive medication in the past six months. Of these, 21.4% reported taking this medication weekly or daily. Additionally, OTC PPIs accounted for 17.0% of the OTC acid suppressive medications.

Our reported prevalence of GERS (48.9%) is higher than the regional estimated prevalence reported in several systematic reviews, ranging from 10%-30% in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East and from 3%-8% in east Asian countries[14,15]. The prevalence of GERS in our study also contrasts with previous Dutch population-based studies that reported lower prevalences (5.0%, 21.0%, and 9.2%, respectively)[16-18]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the use of different definitions of GERS, potentially leading to an overestimation of the reported prevalence of GERS in our study.

It is noteworthy that 904 participants with GERS (57.5%) had never sought medical consultation for these symptoms. These findings raise the question of whether participants perceived their GERS as only minimally inconvenient or that they were not aware of the possible consequences of persistent GERS. A lack of awareness is likely as previous findings indicated that 30% of the participants diagnosed with long-term GERS did not recognize it as a risk factor for BE and EAC[19]. Moreover, consistent with the literature that primary care consultation rates in general were highest in elderly people, our study found that older participants were more likely to seek medical consultation for GERS[20]. Furthermore, Kolb et al[19] have shown that 70% of the participants diagnosed with long-term GERS agreed that having GERS for a longer duration increases the risk for developing BE. This may explain why participants with a longer duration of GERS were more likely to seek medical consultation as reported in our study.

The decision to seek medical help is influenced by personal beliefs about the healthcare system, and cultural factors such as fear, stigma, and concerns about finances, work and caregiving responsibilities[21]. In the United States, delayed help-seeking regularly occurs due to concerns about treatment costs, which seems specific to the healthcare system in the United States[22]. Besides common barriers to seeking medical help regardless of ethnicity, such as fear of cancer, other barriers are more culture-specific[23]. Unlike black Africans, who least frequently report barriers to seeking medical help suggesting an assertive attitude towards the healthcare system, south Asians report the highest emotional and practical barriers[21,23]. In contrast, white people were more likely than any other ethnic group to report that being worried about wasting the doctor’s time would deter them from seeking help[23,24]. The overrepresentation of Dutch (white) indi

Our study shows that 36.6% of the participants with GERS who had never consulted a PCP for these symptoms regularly took OTC acid suppressive medication, suggesting that the use of OTC acid suppressive medication and the associated symptom relief may decrease the willingness to consult a PCP for GERS. This finding is consistent with a survey by Sheikh et al[25] demonstrating that 32.3% of the individuals with GERS took OTC PPIs. This survey also showed that OTC consumers were less likely to be optimally dosed compared with PCP-prescribed consumers, po

Although various professional societies endorse screening of individuals at risk for BE, the proportion of EAC patients with previously diagnosed BE is low[30]. Screening for EAC seems to be challenging for various reasons. First, an effective screening approach requires that the population at risk seeks medical consultation for persistent GERS. Therefore, more public awareness of the potential long-term risks of untreated persistent GERS and improved recognition of GERS are required. Our study revealed a significant cohort (11.1%) of individuals fulfilling the ESGE Guideline screening criteria for BE and EAC that had never consulted a PCP for GERS. However, it should be considered that the actual number of individuals at risk for BE and EAC could be lower, as in our study long-term GERS were defined as symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation for at least one day during the past week combined with experiencing these symptoms ≥ 5 years rather than weekly symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation ≥ 5 years. Second, current guidelines strongly rely on GERS as a criterion for endoscopic screening, but this criterion alone lacks sensitivity and specificity. However, the risk of BE increased by 1.2% for each additional risk factor supporting the concept of BE screening in the population at risk and emphasizing the need for medical consultation for persistent GERS[31]. Yet, there is a need for a better personalized approach to select patients for endoscopic screening. Various prediction tools have been developed but further prospective validation studies are needed before implementation in routine clinical practice can be considered[32]. Lastly, in countries with robust primary care gatekeeping systems (e.g., the Netherlands and United Kingdom), the necessity for recognizing the population at risk by a PCP, in this case a general practitioner (GP), should be highlighted. In these systems, the GP acts as a gatekeeper to second-line specialist care[33]. However, GPs are less likely to be aware of the screening criteria compared with gastroenterologists[7]. To overcome this barrier, the screening criteria should be reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of internal medicine specialists, gastroenterologists and PCPs and should then be implemented in both primary and secondary/tertiary care societal guidelines. Since healthcare systems with a gatekeeper function could play important roles in screening for cancer, the effectiveness of the involvement of PCPs is an important area of research[24,34]. In Europe, national screening programs have been implemented in a growing number of countries[24]. The three most widely available programs are for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening; however, the involvement of PCPs varies depending on the chosen strategy and local healthcare policy[24].

This study has several strengths, such as the use of the Dutch population registry to select individuals resulting in a representative study sample in terms of gender. Besides, most of the questions selected to assess the outcomes of interest were validated for the Dutch population and were reviewed by professionals, thereby enhancing the reliability and accuracy of our findings. However, we also acknowledge limitations in our study. First, participants who agreed to participate might have had more problematic GERS than those who did not accept the invitation potentially leading to an overestimation of the prevalence of GERS. Second, our study is limited by a relatively low response rate and the overrepresentation of older, non-deprived, and Dutch individuals indicating a minor socio-economic disparity in survey completion. Therefore, the generalizability of our results should be interpreted with caution. Selective participation might have affected the findings since lower socio-economic groups and ethnic minority groups are generally less aware of the possible consequences of persistent GERS. This might lead to an overestimation of the level of awareness in our study. Moreover, the overrepresentation of older individuals in our study might have contributed to an overestimation of the reported prevalence of GERS since previous research shows that GERS prevalence is significantly higher in older age groups[15]. We expect that the socio-economic disparity in survey completion likely had little impact on the reliability of the PCP consultation rates observed in our study. Although our study shows that older individuals were more likely to consult a PCP for GERS, this finding is expected to be negated by the overrepresentation of middle- or higher-educated individuals in the study sample who were less likely to consult a PCP for GERS according to our findings. Third, self-reported data introduces the potential of recall bias, as participants might not accurately remember the outcomes of interest. Fourth, selection bias might have been introduced due to the web-based design and language barriers (i.e., the survey was only available in Dutch). Fifth, since the actual response rate turned out to be lower than expected, the confidence level and margin of error had to be adjusted. As a result, our findings may be less reliable than initially thought.

In conclusion, this study reveals a substantial proportion of participants, fulfilling the screening criteria for BE and EAC, who had never sought medical consultation for GERS. Our findings highlight the importance to encourage patients to consult a PCP when having long-term GERS and/or when taking for a prolonged period OTC acid suppressive medication. Health care systems should develop strategies to identify and screen these at risk individuals who do not routinely engage with PCPs for their GERS. Future screening approaches should consider methods to reach this hidden population at risk to optimize early detection of BE and EAC.

| 1. | Thrift AP. Global burden and epidemiology of Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:432-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Morgan E, Soerjomataram I, Rumgay H, Coleman HG, Thrift AP, Vignat J, Laversanne M, Ferlay J, Arnold M. The Global Landscape of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Incidence and Mortality in 2020 and Projections to 2040: New Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:649-658.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 796] [Cited by in RCA: 743] [Article Influence: 185.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | GBD 2017 Oesophageal Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of oesophageal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:582-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Eluri S, Shaheen NJ. Barrett's esophagus: diagnosis and management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:889-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1057] [Cited by in RCA: 1321] [Article Influence: 110.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Jung KW, Talley NJ, Romero Y, Katzka DA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Dunagan KT, Lutzke LS, Wu TT, Wang KK, Frederickson M, Geno DM, Locke GR, Prasad GA. Epidemiology and natural history of intestinal metaplasia of the gastroesophageal junction and Barrett's esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1447-1455; quiz 1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Trindade AJ, Shaheen NJ. Screening for Barrett oesophagus - a call for collaboration between gastroenterology and primary care. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:342-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, Singal AG, Vajravelu RK, Wani S; SCREEN-BE Study Group. Understanding Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers Among Gastroenterologists and Primary Care Providers Is Crucial for Developing Strategies to Improve Screening for Barrett's Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1568-1573.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-328; quiz 329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1148] [Article Influence: 88.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6805] [Cited by in RCA: 13645] [Article Influence: 718.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 11. | Aanen MC, Numans ME, Weusten BL, Smout AJ. Diagnostic value of the Reflux Disease Questionnaire in general practice. Digestion. 2006;74:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, Rockwood T, Carlsson R, Adlis S, Fendrick AM, Jones R, Dent J, Bytzer P. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Statistics Netherlands. Sociaal-economische status per postcode. [cited 8 August 2023]. Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2022/26/sociaal-economische-status-per-postcode-2019. |

| 14. | GBD 2017 Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:561-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Bazzoli F, Ford AC. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2018;67:430-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stanghellini V. Three-month prevalence rates of gastrointestinal symptoms and the influence of demographic factors: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:20-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tielemans MM, Jaspers Focks J, van Rossum LG, Eikendal T, Jansen JB, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG. Gastrointestinal symptoms are still prevalent and negatively impact health-related quality of life: a large cross-sectional population based study in The Netherlands. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Kerkhoven LA, Eikendal T, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG, Jansen JB. Gastrointestinal symptoms are still common in a general Western population. Neth J Med. 2008;66:18-22. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, Gallegos J, O'Hara J, Tarter W, Hochheimer CJ, Golubski B, Kopplin N, Hennessey L, Kalluri A, Devireddy S, Scott FI, Falk GW, Singal AG, Vajravelu RK, Wani S. Patient Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Barriers to Barrett's Esophagus Screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:615-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hobbs FDR, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, Stevens S, Perera-Salazar R, Holt T, Salisbury C; National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007-14. Lancet. 2016;387:2323-2330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Scott ECS, Hoskin PJ. Health inequalities in cancer care: a literature review of pathways to diagnosis in the United Kingdom. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;76:102864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Smith LK, Pope C, Botha JL. Patients' help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: a qualitative synthesis. Lancet. 2005;366:825-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Niksic M, Rachet B, Warburton FG, Forbes LJ. Ethnic differences in cancer symptom awareness and barriers to seeking medical help in England. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:136-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, Dommett R, Earle C, Emery J, Fahey T, Grassi L, Grunfeld E, Gupta S, Hamilton W, Hiom S, Hunter D, Lyratzopoulos G, Macleod U, Mason R, Mitchell G, Neal RD, Peake M, Roland M, Seifert B, Sisler J, Sussman J, Taplin S, Vedsted P, Voruganti T, Walter F, Wardle J, Watson E, Weller D, Wender R, Whelan J, Whitlock J, Wilkinson C, de Wit N, Zimmermann C. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1231-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sheikh I, Waghray A, Waghray N, Dong C, Wolfe MM. Consumer use of over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:789-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Becher A, El-Serag H. Systematic review: the association between symptomatic response to proton pump inhibitors and health-related quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:618-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tack J, Becher A, Mulligan C, Johnson DA. Systematic review: the burden of disruptive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1257-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Vaezi MF, Yang YX, Howden CW. Complications of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:35-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 39.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Targownik LE, Fisher DA, Saini SD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on De-Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1334-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bhat SK, McManus DT, Coleman HG, Johnston BT, Cardwell CR, McMenamin U, Bannon F, Hicks B, Kennedy G, Gavin AT, Murray LJ. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma and prior diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus: a population-based study. Gut. 2015;64:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Qumseya BJ, Bukannan A, Gendy S, Ahemd Y, Sultan S, Bain P, Gross SA, Iyer P, Wani S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors for Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:707-717.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rubenstein JH, McConnell D, Waljee AK, Metko V, Nofz K, Khodadost M, Jiang L, Raghunathan T. Validation and Comparison of Tools for Selecting Individuals to Screen for Barrett's Esophagus and Early Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2082-2092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Peeters KMM, Reichel LAM, Muris DMJ, Cals JWL. Family Physician-to-Hospital Specialist Electronic Consultation and Access to Hospital Care: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2351623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ong AH, Young D, Valderas JM, Zhou Y. Addressing cancer care gaps through improved early cancer diagnosis in Singapore: research priorities to inform clinical practice. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;46:101073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/