Published online Jan 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.111996

Revised: August 18, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 14, 2026

Processing time: 176 Days and 0.4 Hours

Small intestinal villi are essential for nutrient absorption, and their impairment can lead to malabsorption. Small intestinal villous atrophy (VA) encompasses a heterogeneous group of disorders, including immune-mediated conditions (e.g., celiac disease, autoimmune enteropathy, inborn errors of immunity), lymphoproliferative disorders (e.g., enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma), infectious causes (e.g., tropical sprue, Whipple’s disease), iatrogenic factors (e.g., Olmesartan-associated enteropathy, graft-vs-host disease), as well as inflammatory and idiopathic types. These disorders are often rare and challenging to distinguish due to overlapping clinical, serological, endoscopic, and histopathological features. Through a systematic literature search using keywords such as small intestinal VA, malabsorption, and specific enteropathies, this review provides a comprehensive overview of diagnostic clues for VA and malabsorption. We systematically summarize the pathological characteristics of each condition to assist pathologists and clinicians in accurately identifying the underlying etiologies. Current studies still have many limitations and lack broader and deeper investigations into these diseases. Therefore, future research should focus on the development of novel diagnostic tools, predictive models, therapeutic targets, and mechanistic molecular studies to refine both diagnosis and management strategies.

Core Tip: Small intestinal villous atrophy is a key pathological feature of various rare and heterogeneous disorders associated with malabsorption. Owing to overlapping clinical, serological, and histological features among immune-mediated, lym

- Citation: Li MH, Wang QP, Ou CZ, Xu TM, Chen Y, Tang H, Zhang Y, Lai YJ, Qin XZ, Li J, Zhou WX, Li JN. Diagnostic clues in patients with clinical malabsorption and pathological small intestinal villous atrophy: Immune-mediated type and beyond. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(2): 111996

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i2/111996.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.111996

The small intestinal villi play a pivotal role in the absorption of six major nutrients (protein, carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins, water, and inorganic salts). Various factors, including immune dysregulation, genetic susceptibility, intestinal microbiota imbalance, environmental triggers, and iatrogenic causes, can lead to small intestine villous atrophy (VA)[1-4], which in turn leads to varying degrees of malabsorption syndrome. Malabsorption of fats, carbohydrates, and proteins can cause steatorrhea, wasting, edema, and anemia. Impaired absorption of water and inorganic salts may lead to electrolyte imbalances, such as hypokalemia, hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia, which can result in arrhythmia, osteoporosis, and tetany in severe cases. Deficiencies in fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins, including vitamins B, K, and D, manifest as glossitis, stomatitis, neuritis, coagulation abnormalities, and worsening osteomalacia[5].

Small intestinal VA disorders encompass a heterogeneous group of conditions with VA observed via endoscopy and histopathology. These disorders can be classified into six main categories on the basis of pathophysiological mechanisms: Immune-mediated, lymphoproliferative, infectious, inflammatory, iatrogenic, and idiopathic[1,3]. Differential diagnosis is often challenging because of overlapping clinical, serological, endoscopic, and histological features. For example, celiac disease (CeD) is an immune-mediated disorder and the leading cause of small intestinal VA[3], with seropositive CeD accounting for 94.9% of VA cases[6]. However, in the absence of definitive CeD serologic autoantibodies, the diagnosis of CeD is usually confused with other etiologies of VA[7-10]. More concerningly, these seronegative enteropathies are associated with poorer prognoses than are seropositive CeD[6,10]. Early recognition is crucial to initiate appropriate treatment, prevent disease progression, and improve outcomes through regular follow-up. This review provides an overview of the clinical and pathological features, as well as key points for differential diagnosis, of the major causes of malabsorption syndrome and small intestinal VA, with the aim of increasing the diagnostic accuracy for these rare but clinically significant conditions.

We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science for articles published before May 2025. Keywords included small intestinal VA, malabsorption, and enteropathy to generate a comprehensive overview. We further performed disease-specific searches for CeD, autoimmune enteropathy (AIE), common variable immunodeficiency, inborn errors of immunity (IEIs), lymphoma, lymphoproliferative disorders, infectious enteropathy, iatrogenic enteropathy, and inflammatory or idiopathic enteropathy. Eligible studies included original research, reviews, case series, and guidelines published in English that addressed the etiology, clinical and pathological features, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of small intestinal VA. References of relevant publications were also screened to identify additional sources. Findings were synthesized qualitatively, with a focus on clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological characteristics. This review aims to inform clinicians, pathologists, and researchers by providing diagnostic clues of patients with small intestinal VA and malabsorption. The findings are intended to directly guide clinical decision-making and patient management, while also offering insights for future research directions and the development of evidence-based guidelines.

CeD, also known as gluten-sensitive enteropathy, can affect both children and adults. Typical manifestations of CeD include malabsorption and chronic diarrhea, but it can also be asymptomatic or present only with extraintestinal symptoms. In Western countries, the prevalence is approximately 1.0%[11,12], and the incidence has increased by 7.5% annually over the past several decades[13]. For Asian countries, the prevalence is approximately 0.5%[14].

The most commonly used diagnostic criteria for CeD require a diagnostic intestinal biopsy (Marsh-Oberhuber grade

| Marsh-Oberhuber | Corazza-Villanacci | |||||

| Stage | IELs/100 enterocytes in Marsh | Crypts | Villi | Stage | IELs/100 enterocytes in Corazza | Villi |

| Type 0 | < 40 | Normal | Normal | None | < 25 | Normal |

| Type 1 | > 40 | Normal | Normal | Grade A | > 25 | Nonatrophic |

| Type 2 | > 40 | Hypertrophic | Normal | |||

| Type 3 (3a, 3b) | > 40 | Hypertrophic | Mild to moderate blunting | Grade B1 | > 25 | Atrophic, villous-crypt ratio < 3:1 |

| Type 3 (3c) | > 40 | Hypertrophic | Severe blunting (flat) | Grade B2 | > 25 | Atrophic, villi no longer detectable |

| Type 4 | < 40 | Normal | Severe blunting (flat) | / | / | / |

Clinicians and pathologists should be aware of several factors that may confound the diagnosis of CeD or other enteropathies with VA[24], including inadequate biopsy sampling during endoscopy[24,25], poor specimen orientation[26], and incorrect interpretation of histopathological findings[18,26,27]. For instance, poor orientation due to inaccurate specimen collection or processing may cause partial fusion or crushing of adjacent villi, which could be mistakenly interpreted as VA[26]. These factors can lead to an overestimation of seronegative CeD (SNCD) and the unnecessary initiation of a gluten-free diet (GFD).

A minority of CeD patients (2%-6.5%) present with VA and negative serology at diagnosis, a condition known as seronegative CeD[1]. SNCD is the leading cause of seronegative enteropathy with VA in adults, followed by iatrogenic, infectious, and immune-mediated conditions[1,10,28]. In children, inflammatory, infectious, and immune-mediated diseases predominate, whereas SNCD and iatrogenic causes are rare[1,29,30]. A recent study retrospectively identified the predictors of subsequent positive TTG-IgA autoantibodies in patients with duodenal VA on biopsy but without prior CeD serology results, including non-Hispanic and white race/ethnicity and younger age[31].

The heterogeneity of SNCD, which includes early-stage CeD, late-stage CeD [such as refractory CeD (RCD) or even lymphoma], and cutaneous CeD such as dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), complicates its differentiation from other enteropathies with VA[1,32,33]. In addition, CeD patients with concomitant immunodeficiencies, such as IgA deficiency and common variable immune deficiency (CVID), may also present with negative serology[3,34].

Diagnosis of SNCD is based on the clinical and histological response to a GFD, after the exclusion of other non-celiac enteropathies (NCEs)[32,35]. T-cell receptor (TCR) γδ+ IELs and the celiac lymphogram (defined as an increase in TCR γδ+ cells and a decrease in CD3- IELs) have been proposed as diagnostic indicators of SNCD in patients with seronegative VA[36], which requires validation in future studies. In addition, the potential of small intestinal mucosa deposits of IgA TTG2 antibodies in differentiating SNCD and NCEs remains uncertain[1,37,38]. Additionally, a negative HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 typing is useful for excluding CeD[1,35].

DH is the cutaneous manifestation of CeD and is characterized by intense itch and blistering symmetrical rash located on the elbows, knees, and buttocks[39]. Currently, the DH to CeD prevalence ratio is 1:8[39]. Although DH patients rarely exhibit the classic CeD gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, their small bowel biopsies still revealed VA, crypt hyperplasia, and sometimes inflammatory findings, such as intraepithelial lymphocytosis and increased densities of ɣδ+ T cells[39,40]. The diagnosis is confirmed by the detection of granular IgA deposits in the papillary dermis through immunofluorescence[39]. The DH autoantigen, transglutaminase 3, is found in immune complexes and deposited at the same site[39].

Most patients with CeD experience symptom improvement after strictly adhering to a GFD. However, a small subset of patients continue to exhibit clinical symptoms and VA, despite following a GFD for one year, which is termed RCD[41]. RCD is classified into type I (RCDI) and type II (RCDII) on the basis of whether IELs display an abnormal phenotype. The distinction between RCDI and RCDII is achieved through immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and TCR rearrangement testing[42-44]. NKp46 is a diagnostic biomarker that has shown potential for distinguishing RCDII from CeD and RCDI, with a threshold of 25 NKp46+ IELs per 100 epithelial cells[45]. RCDI generally has a more favorable prognosis, whereas RCDII is associated with more severe clinical manifestations and a poorer prognosis. Furthermore, RCDII is associated with the serious complication of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL)[42,43], which will be discussed in detail in the “Lymphoproliferative type” section below.

AIE is a rare condition in adults characterized by chronic watery diarrhea and severe weight loss[8,46]. Adult AIE is an important etiology of small intestinal VA that poses problems for differential diagnosis with SNCD[3].

The diagnostic criteria for adult AIE are still evolving[3,4,46-48]. Compared with nonspecific and subtle endoscopic findings, which offer little diagnostic value, pathological findings have played a pivotal role in all the proposed diagnostic criteria. In contrast to CeD, AIE is refractory to a GFD and usually presents with minimal IEL. The diagnosis of AIE can be challenging and is often misdiagnosed as RCD. One study revealed no significant difference in the degree of VA between AIE patients and RCD I patients; However, the IEL count might be helpful for distinguishing AIE patients from RCD I patients[46]. IELs are present in 100% of RCD I patients, whereas they are present in 50% of AIE patients[46]. The small intestinal villous epithelium normally consists of columnar enterocytes interspersed with goblet cells, Paneth cells, enteroendocrine cells, and stem cells. Importantly, the reduction in goblet cells and Paneth cells also serves as a characteristic feature of AIE[4].

Masia et al[49] proposed that the duodenal mucosal changes in AIE can be categorized into four types (Table 2): Active chronic duodenitis (ACD), CeD-like, graft-vs-host disease-like (GVHD-like), and mixed/not predominant patterns. The clinical value of pathological features beyond their use in diagnostic criteria, such as their role in relapse stratification or predicting treatment response, has not yet been clearly established. Many reported cases of AIE were associated with immune deficiencies, especially CVID[47,50-52]. However, some differences in histological features exist between AIE patients with primary immunodeficiency (PID) and those without. Specifically, the CeD-like pattern is more common in AIE patients with PID, whereas the mixed pattern is more frequently observed in AIE patients without PID[50].

| Classification | Active chronic duodenitis | CeD-like | GVHD-like | Mixed/no predominant |

| Description[49] | Villous atrophy, expansion of the lamina propria by mixed but predominantly mononuclear inflammation (consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils), and neutrophilic cryptitis (with or without crypt abscesses); with or without increased apoptosis in the crypt epithelium. Plasma cells were the predominant cell within the lamina propria inflammatory infiltrate | Villous atrophy and marked IEL (> 40 lymphocytes/100 enterocytes) | Increased apoptosis in crypt epithelium (> 1 apoptotic figure per 10 crypts), with or without crypt dropout, with minimal inflammation | Admixture of ≥ 2 patterns or insufficient features to qualify for other patterns |

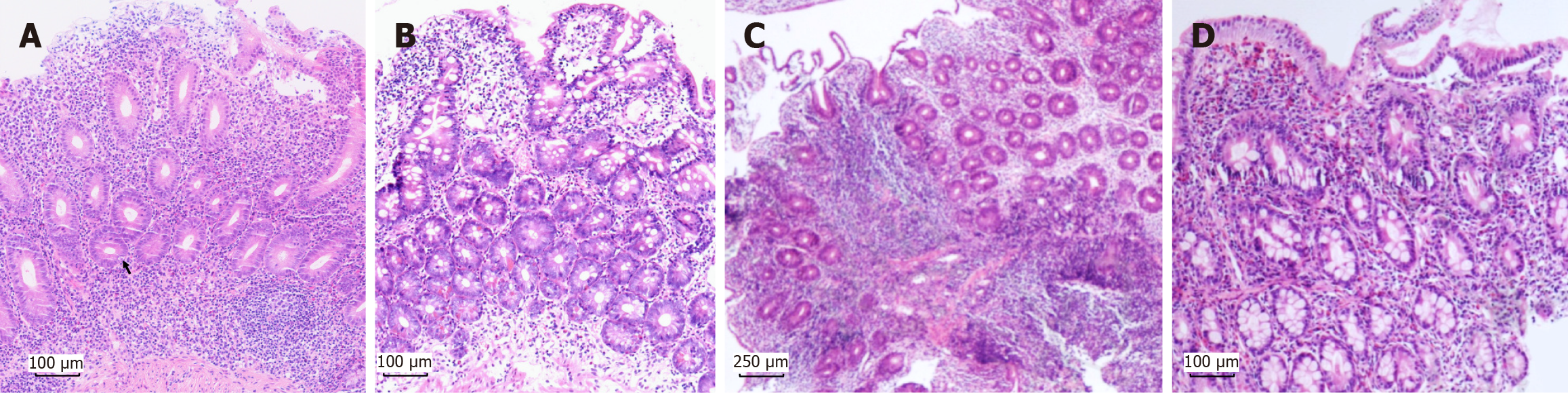

On the basis of published criteria for adult AIE and our previous experience, a modified criterion for adult AIE was defined as follows[4]: (1) Chronic diarrhea lasts more than 6 weeks in adults; (2) Malnutrition that does not respond to a GFD; (3) Absence of severe immunodeficiencies; (4) Pathological findings in the small intestine include VA; a reduction in the number of goblet cells and/or Paneth cells (Figure 1A); the presence of apoptotic bodies; mild IEL infiltration; and lymphocytic infiltration in the lamina propria or deep crypts; and (5) Exclusion of other diseases causing villi atrophy (e.g., CeD, lymphoma). Supportive criteria include neutrophilic infiltration, positivity for anti-enterocyte or anti-goblet cell antibodies, a negative celiac antibody profile, and an effective response to steroids or immunosuppressants. The above criteria help in the diagnosis of adult AIE and especially favor the discrimination of CVID with GI involvement, which still needs to be externally validated in the future.

The involvement of GI regions beyond the duodenum, including the esophagus, stomach, ileum and colon, has also been reported in AIE patients[49,50]. These regions exhibit pathological changes that are similar to those observed in the duodenum, particularly in the ileum, but also present distinct characteristics. Esophageal biopsies revealed esophagitis (73.2%) and mild acanthosis (16.7%)[50]. Gastric biopsies revealed chronic quiescent gastritis (50%), chronic active gastritis (40.6%), follicular gastritis (15.6%), lymphocytic gastritis (9.4%), apoptotic bodies (9.4%), and increased eosinophilic counts (12.5%)[50]. Colonic biopsies revealed acute (74.1%) or chronic (18.5%) inflammation, apoptotic bodies (51.9%), increased eosinophilic infiltration (44.4%), follicular lymphoid aggregates (22.2%), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection (7.4%)[50]. Paneth cell metaplasia was also observed in 9% of the colon[49].

Some adult AIE patients exhibit clinical and histopathological resolution following treatment with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive agents, whereas others show no response[8,46,49]. Additionally, relapse of diarrhea is commonly observed[8], and relapse occurs in almost half of patients within 1 year of follow-up[4]. Moreover, the development of malignant complications in AIE patients has also been reported, such as EATL, which worsens the prognosis[52-54].

CVID is the most common primary immunodeficiency disorder (PID) in adults and typically presents with hypogammaglobulinemia[55] and chronic pulmonary or GI infections[56,57]. To broaden the concept from immune deficiency to encompass immune dysregulation, the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) revised the nomenclature in 2017[58], replacing PIDs with IEIs. The IUIS classification was further updated in 2019[59], 2022[60] and 2024, and a total of 555 IEIs have been reported and categorized into 10 tables (https://iuis.org/committees/iei/). CVID with no gene defect specified is classified under the table of predominantly antibody deficiencies and further categorized into the subtable of Severe Reduction in at Least 2 Serum Immunoglobulin Isotypes with Normal or Low Number of B Cells, CVID Phenotype. Besides, diseases manifesting as CVID that are associated with specific gene mutations are listed separately. With respect to diagnostic criteria, the European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) and the Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency (PAGID) proposed criteria for CVID in 1999[61], which were updated by the ESID in 2019[62], with a greater emphasis placed on immune cell subsets.

Both infectious (such as Giardia, norovirus, and bacteria) and noninfectious GI involvement have been documented in CVID patients, who frequently present with chronic diarrhea and malabsorption[7,63-67]. VA is a common pathological finding, occurring in approximately 31%-89% of CVID patients with GI involvement[65,68]. The underlying mechanism of VA in CVID remains unclear and cannot be attributed solely to infection[65,69]. In addition to VA, CVID patients with GI involvement exhibit diffuse inflammatory changes in the duodenal and colonic mucosa[69,70], characterized by increased lymphocytes in the lamina propria and epithelium, along with epithelial apoptosis and GVHD-like changes[3]. These histopathological features are less frequently observed in CVID patients without GI involvement[69]. Interestingly, peripheral blood CD8+ lymphocytosis in CVID patients could predict intestinal IEL[65]. In addition, lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) from CVID patients with GI involvement produce significantly more T helper (Th) 1 cytokines, interleukin (IL)-12, and interferon-γ[69].

Pathological findings in CVID patients may overlap with those of other diseases, including CeD, lymphocytic and collagenous colitis, lymphocytic gastritis, granulomatous disease, acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), and inflammatory bowel disease[65,71]. However, certain histopathological features, such as the absence of plasma cells (Figure 1B) and the presence of follicular lymphoid hyperplasia, are relatively distinctive features of CVID and are rarely found in other diseases[65,71,72]. Reduced plasma cells are commonly observed throughout the entire GI tract, apart from the esophagus[71,73]. Recent studies have demonstrated that IgA+ plasma cells are the most frequently reduced plasma cell subset in CVID patients[73]. As a result, local deficiency of secretory IgA due to reduced plasma cells may disrupt intestinal homeostasis and contribute to the development of VA[65,72,73].

In terms of differential diagnosis, HLA genotyping is highly useful for excluding CeD in CVID patients[74]. CeD can only be diagnosed in CVID patients if they respond to a GFD[35]. However, serology tests may be misleading in distinguishing between CeD and CVID[35]. Genetic testing is required when necessary to rule out IEI caused by genetic mutations[60]. Moreover, the differential diagnosis of AIE relies on pathological findings of decreased numbers of goblet/Paneth cells in biopsy samples[75], which are preferable to AIE, whereas recurrent pulmonary infections, decreased immunoglobulin levels and the absence of plasma cells are preferable to CVID.

For treatment, a GFD is generally ineffective for treating CVID, and management typically relies on intravenous immunoglobulin and anti-infection therapy. There were some cases supporting the use of budesonide or steroids[65,76], but more evidence is needed to determine the indications and timing of the use of these immunosuppressive medications. CVID patients are at increased risk of developing malignant conditions such as lymphoma[7] or gastric cancer[77,78], which significantly impact their prognosis[79].

As mentioned in CVID, many patients bearing certain germline mutations can be categorized into other IEIs, which also show malabsorption and VA. In detail, IEIs classified as diseases of immune dysregulation (Table 3 in the IUIS 2022 classification) have seven subgroups[60]. Regulatory T-cell (Treg) dysfunction, exemplified by CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency with autoimmune infiltration (CHAI) caused by an autosomal dominant CTLA-4 defect; LRBA deficiency with autoantibodies, Treg defects, and autoimmune infiltration and enteropathy (LATAIE), which results from an autosomal recessive LRBA defect; and immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX), which is associated with an X-linked FOXP3 gene defect. Another subtable is autoimmune diseases with or without lymphoproliferation, including autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, candidiasis, and ectodermal dystrophy (APECED), which are caused by an autosomal recessive AIRE defect.

| Update | ESID and the PAGID in 1999[61] | IUIS in 2017[58] | ESID in 2019[62] | IUIS in 2019[59] and in 2022[60] | IUIS in 2024 (https://iuis.org/committees/iei/) |

| Description | Probable CVID (a marked decrease1 in serum IgG and IgA levels) and possible CVID (a marked decrease in one of the major isotypes, IgM, IgG, or IgA). Both need to fulfill all of the following criteria; (1) Onset of immunodeficiency at greater than 2 years of age; (2) Absent isohemagglutinins and/or poor response to vaccines; and (3) Excluded defined causes of hypogammaglobulinemia | Rename PIDs, including CVID, as IEIs. A total of 354 IEIs were categorized into 9 tables | At least one of the following: (1) Increased susceptibility to infection; (2) Autoimmune manifestations; (3) Granulomatous disease; (4) Unexplained polyclonal lymphoproliferation; and (5) Affected family member with antibody deficiency. And marked decrease of IgG and marked decrease of IgA with or without low IgM levels (measured at least twice; < 2 SD of the normal levels for their age). And at least one of the following: (1) Poor antibody response to vaccines (and/or absent isohemagglutinins); i.e., absence of protective levels despite vaccination where defined; and (2) Low switched memory B cells (< 70% of age-related normal value). And secondary causes of hypogammaglobulinemia have been excluded (e.g., infection, protein loss, medication, malignancy). And diagnosis is established after the fourth year of life (but symptoms may be present before). And no evidence of profound T-cell deficiency, defined as 2 of the following (y < years of life): (1) CD4 numbers/microliter: 2-6 years < 300, 6-12 years < 250, > 12 years < 200; (2) %naïve of CD4: 2-6 years < 25%, 6-16 years < 20%, > 16 years < 10%; and (3) T-cell proliferation absent | Increase to 416 and 485 IEI, respectively, and categorized into 10 tables | Increase to 555 IEI and categorized into 10 tables (similar to IUIS 2022). Unknown Genetic defect; Low IgG and IgA and/or IgM; Clinical phenotypes vary: Most have recurrent infections, some have polyclonal lymphoproliferation, autoimmune cytopenias and/or granulomatous disease |

The diagnostic complexity arises from substantial clinical overlap between these rare genetic disorders and immune-mediated enteropathies (AIE, CVID, and RCD)[80-85]. AIE-like manifestations may present as isolated GI disorders or as part of systemic syndromes, particularly IPEX and APECED, which predominantly affect pediatric populations[82]. Notably, anti-AIE-75 autoantibodies demonstrate diagnostic specificity for IPEX but are absent in APECED cases[86,87].

Moreover, some patients initially met the CVID criteria, and subsequent genetic and functional testing revealed CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency as the underlying etiology[81,88,89]. CHAI primarily manifests as hypogammaglobulinemia (84%), lymphoproliferation (73%), and autoimmune cytopenia (62%), with frequent respiratory (68%) or GI involvement (59%) and rare but serious neurological manifestations in approximately 29% of cases[85,90,91]. LATAIE, previously categorized as a CVID subtype, also leads to reduced CTLA-4 expression in Treg and activated T cells[92]. Therefore, CHAI and LATAIE have strikingly similar molecular mechanisms and clinical manifestations.

Both CHAI and LATAIE may manifest phenotypically resembling IPEX syndrome[86,93], whereas enteropathy is more frequent in LATAIE than in CHAI[93]. More specifically, CHAI is associated with a higher prevalence of granulomas, malignancies, atopy, cutaneous disorders, and neurological complications, whereas LATAIE is more frequently linked to life-threatening infections; pneumonia; ear, nose, and throat disorders; organomegaly; enteropathy; and growth failure[93]. However, the prevalence of autoimmune cytopenia - including immune thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and autoimmune neutropenia - does not significantly differ between the CHAI and LATAIE[93]. The most frequently used biological therapies for CHAI and LATAIE are abatacept and rituximab[83,93-96]. Other treatment approaches include other immunosuppressive agents and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[97-100].

In addition to those already mentioned, many other genetic mutations (such as those in STAT3 and CD25) can also lead to similar enteropathies[60,86,101]. With an increasing number of studies investigating these rare diseases, the necessity of genetic testing in patients with autoimmune features and a protracted disease course is further underscored. Advances in molecular medicine have enabled the application of targeted therapies and precision medicine, significantly improving treatment outcomes for these patients[102].

In this review, we specifically focus on immunoproliferative diseases that can cause chronic diarrhea and VA. Primary GI T-cell lymphoma is rare, accounting for less than 9% of all primary GI lymphomas[103]. Despite its rarity, this condition presents significant diagnostic challenges and exhibits considerable variability in prognosis. This review highlights two aggressive forms of the disease, namely, EATL and monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL), as well as two indolent forms, indolent T-cell lymphoma (ITCL)/Lymphoproliferative disorder of the GI tract (LPD-GI) and indolent NK-cell LPD-GI (INKLPD-GI). In addition to T-cell lymphoma, immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID) belongs to extra-nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, can also manifest as small intestinal VA and chronic non-bloody diarrhea[104].

EATL, previously referred to as type I EATL, is an aggressive lymphoma originating from intestinal intraepithelial T lymphocytes that accounts for 5%-8% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) and 10%-25% of primary intestinal lymphomas[105]. EATL primarily affects the small intestine but can also involve the stomach, colon, and extraintestinal sites, such as the skin and central nervous system[106]. Dissemination to mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and bone marrow is also observed[106].

EATL is strongly associated with CeD and often arises as a complication of RCD, particularly RCD II. As previously noted, RCD I is characterized by increased polyclonal IELs with a normal immunophenotype, whereas RCD II is distinguished by monoclonal IELs with aberrant immunophenotypes[46]. Progression from RCD II to EATL is common, with 50% of patients developing EATL within 4-6 years following an RCD II diagnosis[107]. EATL carries a poor prognosis, with a two-year survival rate of only 15%-20%[107]. Thus, the five-year survival rate is 93% for RCD I patients but drops significantly to 44% for those with RCD II[108]. However, EATL can also develop independently of CeD, with half of patients presenting with EATL as their first clinical manifestation[105].

Clinically, EATL patients commonly experience diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, malaise, and B symptoms, including weight loss, fever, and night sweats. Notably, half of the patients presented with acute symptoms due to intestinal perforation, obstruction, or hemorrhage[105,106]. On endoscopic examination, EATL lesions typically appear as edematous segments with large circumferential ulcers, sometimes plaques and strictures. In rare cases, EATL presents as tumor masses that are bulky, exophytic, or infiltrating[105,106]. Additionally, EATL may resemble CeD, displaying features such as VA and loss of mucosal folds[105,106].

Histologically, malignant cells exhibit variable cytologic atypia and are pleomorphic, with medium to large sizes and sometimes anaplastic features[103,105,106]. EATL frequently accompanies mixed inflammatory infiltrates (histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells) and may obscure tumor cells[106]. Extensive necrosis is common. Neoplastic cells infiltrate the entire intestinal wall and typically express cytoplasmic CD3, CD2, CD7, and CD103 along with the cytotoxic markers TIA-1, perforin, and granzyme-B but lack CD4, CD5, and CD56[106]. Surface CD3 and TCR are absent in most cases[106]. Approximately 1/3 of patients are CD8+ and 1/4 of patients exhibit intracellular TCRβ expression. CD30 expression is typical in anaplastic cells, but activin receptor-like kinase-1 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) always remains negative. The mitotic rate (Ki-67) is high, whereas megakaryocyte-associated tyrosine kinase (MATK) is detected in < 40% of tumor cells[105]. Importantly, intestinal mucosae beyond the EATL tumor site exhibit features of enteropathy similar to those of CeD (increased IEL, VA, increased IEL, and crypt hyperplasia)[103,105,106].

MEITL, formerly known as type II EATL, is also an aggressive subtype of PTCL that primarily affects the small intestine and presents with chronic GI symptoms (such as diarrhea and abdominal pain), acute abdominal conditions (such as intestinal obstruction and perforation) or no obvious symptoms[106]. EATL is more common in Western populations, whereas MEITL occurs in Asian populations[106]. The typical endoscopic manifestations of MEITL are deep ulcers with rigid intestinal segments. Some MEITL patients show mild endoscopic changes, including VA, swelling, mosaic mucosa and shallow ulcers.

MEITL is generally easy to distinguish from EATL because of its characteristic histological and immunophenotypic features[105]. The neoplastic cells in MEITL are usually monomorphic, medium-sized cells and display predominant epitheliotropism (Figure 1C)[103,105]. Unlike EATL, necrosis is rare in MEITL. Immunophenotypically, MEITL cells express CD3+, CD4-, CD5-, CD8+, CD56+, and CD30-, activated cytotoxic markers (TIA1+/-, granzyme B+, perforin+/-), and heterogeneous TCR expression (TCRγδ more frequently than TCRαβ)[105]. MATK is a novel distinguishing marker of MEITL[109] and is expressed in more than 80% of MEITL cells. Both MEITL and EATL frequently express NKp46, a shared marker that helps differentiate them from indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (ITLPDs)[45]. The distant mucosa from the tumor often shows increased IEL without VA[105].

MEITL and EATL have a poor prognosis, with a one-year survival rate of 30%-40%, often due to intestinal perforation and infections[106].

ITCL/LPD-GI is a rare condition characterized by an indolent, chronic, and relapsing course, typically without aggressive or destructive growth patterns. To date, only small case series have been reported[103,110-113]. The first case was described in 1994[114], and by 2013, the disorder was officially named ITLPDs of the GI tract (ITLPD-GI)[115]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized it as a provisional entity in the fourth edition of its Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues in 2017[116]. In the fifth edition, the WHO renamed ITLPD-GI ITCL of the GI tract, establishing it as a distinct entity[117]. However, the International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms still prefers the term ITLPD-GI[118]. Therefore, this review adopts the term ITCL/LPD-GI to describe these conditions.

ITCL/LPD-GI patients present distinct clinical and pathological features. Its clinical manifestations are protracted and persistent but nonspecific (mainly chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss and, less frequently, vomiting, dyspepsia, relapsing oral and colorectal ulcers), and it can overlap with other enteropathies[103]. Morphologically, ITCL/LPD-GI is characterized by clonal T-cell proliferation that infiltrates the lamina propria regardless of the location within the GI tract. These lymphocytes are small, mature, and monotonous, without epitheliotropism[103]. Their nuclei are round or slightly irregular, with coarse chromatin, and inconspicuous to absent nucleoli[103]. Epithelioid granulomas and scattered lymphoid follicles may be present, but necrosis is absent[103]. In rare cases, neoplastic cells extend into the muscularis mucosae and submucosa or even infiltrate the entire intestinal wall[103]. The mature T-cell phenotype is 100% CD3+ (75/75) and can be classified into four subgroups on the basis of the expression of CD4 and CD8, with 50% (37/74) being CD4+/CD8-, 39% (29/74) being CD4-/CD8+, 5.4% (4/74) being CD4+/CD8+, and 5.4% (4/74) being CD4-/CD8-[103]. Moreover, CD5+ expression is observed in 80% (16/20) of cases, and TIA1+ expression is frequent in CD8+/CD4- cases. Monoclonal TCR rearrangements were detected in all patients[103]. Remarkably, the proliferation index (Ki-67) was very low (< 5%).

ITCL/LPD-GI can be confused with other enteropathies because of overlapping findings. For example, ITCL/LPD-GI may present with crypt hyperplasia, IELs at the base of villi or crypts (generally not prominent), and rarely VA, which can mimic CeD[103]. A few patients also presented with HLA and serology results that suggested CeD and AIE[111]. One ITCL/LPD-GI patient with concomitant CeD experienced improvement in diarrhea but showed no change in lymphoma pathology after two years on a GFD[111]. Furthermore, a study comparing one ITCL/LPD-GI patient with suspected RCD with four CeD patients revealed differences in lymphocytic infiltration patterns[119]. In the former, infiltration extended throughout the lamina propria, whereas in the latter, it was predominantly intraepithelial.

ITCL/LPD-GI also shares some features with other lymphomas, such as EATL and MEITL. However, many differences in cytomorphology, immunophenotype and TCR help distinguish these conditions. For example, both EATL and MEITL are CD4-negative, with MEITL typically expressing CD56, whereas EATL and ITCL/LPD-GI do not[103]. In addition, EATL and MEITL are NKp46+, whereas ITCL/LPD-GI is NKp46-[45]. For the TCR, ITCL/LPD-GI is positive for TCR-α/

Although ITCL/LPD-GI typically follows an indolent course, there remains a risk of transformation into aggressive T-cell lymphoma[110,120-122], underscoring the importance of regular surveillance. In most cases, the disease remains confined to the GI tract, but extramural involvement (e.g., liver, bone marrow, mesenteric lymph nodes, tonsils) has been reported during disease progression. Therefore, the emergence of new symptoms during long-term follow-up may indicate disease development[103]. Furthermore, the presence of significant atypia should prompt reevaluation of the diagnosis and raise suspicion of disease progression[103].

INKLPD-GI is a distinct entity recognized by the WHO and the International Consensus Classification[103]. It features diffuse infiltration of medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells in the lamina propria, which displace or occasionally destroy glands, but without significant necrosis or vascular destruction. These cells express the NK-cell marker CD56 and do not display CD4, CD5, EBV or monoclonal TCR rearrangement[103]. The background consists of a mixed population of plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, histiocytes, and small mature lymphocytes. Differentiating INKLPD-GI from ITCL/LPD-GI might be challenging, but CD56+ and a lack of TCRs are the key distinguishing features[103]. INKLPD-GI follows an indolent course and does not exhibit aggressive progression.

IPSID, formerly referred to as Mediterranean lymphoma and alpha heavy chain disease, might arise from chronic antigen exposure, which drives clonal B-cell proliferation and potential neoplastic progression[123]. IPSID mainly occurs in developing countries with risk factors (poor sanitation, low socioeconomic status, and clean water inaccessibility)[123]. Clinical manifestations include voluminous diarrhea, subfebrile stages, nocturnal diaphoresis, abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, weight loss, malabsorption and finger clubbing[104,123]. The symptoms of carpopedal spasms and tetany are secondary electrolyte disturbances. IPSID is diagnosed through biopsy and actually displays a spectrum of clonal stages[123]. Histopathological features include VA, crypt atrophy, and distinct infiltration of clonal lymphocytes and plasmacytes at variable stages (Table 4)[124]. These lymphoplasmacytic cells secrete the abnormal monoclonal α-heavy chain (α-HC) protein[123]. Clonal α-HC is detectable via molecular testing even in early disease. Immunohistochemistry revealed CD20+ tumor cells with clonal α-HC lacking light chains and CD138+, CD79a+, and IgA+ plasma cells. Diagnosis is based on the detection of monoclonal α-HC without light chains in the serum, urine, or intestinal secretions or infiltrating cells of the intestinal mucosa.

| Stage | Small intestine involvement | Lymph nodal involvement (mesenteric, other abdominal and retroperitoneal, etc.) |

| Stage A (benign) | Infiltration of the lamina propria, predominantly by mature lymphocytes and plasma cells, accompanied by variable degrees of villous atrophy | Mature plasmocytic infiltration, with limited disruption of the lymph node architecture |

| Stage B (intermediate) | Infiltration extending beyond the mucosa, spreading into the submucosa, characterized by atypical lymphoplasmacytic cells and immunoblastic-like cells, often associated with total or subtotal villous atrophy | Atypical plasmocytic and immunoblastic infiltration, leading to total or subtotal architectural disruption of the lymph nodes |

| Stage C (malignant) | Proliferation of histiocytes (Hodgkin sarcoma) affecting all layers of the intestinal wall. Large masses are formed and transformed into malignant lymphoma | Sarcomatous proliferation, extensively disrupting the entire lymph node architecture |

Owing to overlapping symptoms and histological findings, IPSID can be mistaken for conditions such as CeD, infectious disease [tropical sprue (TS), Whipple’s disease (WD), etc.], and inflammatory disease (inflammatory bowel disease)[123]. Although IPSID and CeD patients both experience surface epithelial damage, VA, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, IPSID patients exhibit crypt atrophy vs crypt hyperplasia in CeD patients. Immunoelectrophoresis and immunoselection, which detect α-HC proteins in serum and body fluids, provide evidence for IPSID, whereas CeD-specific serology supports CeD[123]. Moreover, both CeD and IPSID can progress to high-grade lymphomas, with the former evolving into T-cell lymphomas, often associated with perforations, while the latter predominantly gives rise to B-cell lymphomas, in which perforations are rare[123].

TS, primarily reported in tropical and subtropical regions, is diagnosed on the basis of malabsorption of ≥ 2 unrelated nutrients (e.g., D-xylose absorption, fecal fat estimation, and serum vitamin B12 levels), along with abnormal small bowel mucosal histology (partial VA, increased IEL, increased eosinophils in the lamina propria)[125,126]. Diagnosis also requires ruling out other causes of malabsorption and confirming a sustained response to antibiotics combined with vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation[127]. Clinical, endoscopic and histologic features are very similar between CeD and TS[128,129]; both exhibit many overlapping features, with no difference in the prevalence and duration of chronic diarrhea, weight loss, extent of abnormal fecal fat content, or density of intestinal inflammation. However, some features are more common in CeD, including short stature, vomiting, endoscopic scalloping or attenuation of duodenal folds, histologically high modified Marsh changes, crescendo type IEL, epithelial denudation, mucosal flattening, subepithelial basement membrane thickening and, most importantly, celiac seropositivity[128]. TS commonly shows anemia, an abnormal D-xylose test, endoscopic findings of either normal duodenal folds or mild attenuation, histologically low modified Marsh changes, patchy mucosal changes, decrescendo type IEL, and mucosal eosinophilia[126,128].

WD is a rare (1-3 cases per million) chronic infection with multisystemic involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei (T. whipplei), a gram-positive actinobacterium widely present in the environment[130]. Culturing T. whipplei remains challenging, which constrains diagnostic capability[131].

WD manifests in three clinical forms: Classic WD, isolated T. whipplei endocarditis, and isolated neurological WD[130]. Classic WD follows a characteristic disease course with many nonspecific symptoms[130]. It begins with a prodromal phase lasting 7-8 years and is characterized by migratory arthralgia affecting large peripheral joints[130]. This is followed by the systemic/GI phase, which presents with diarrhea (steatorrhea), weight loss, hypoalbuminemia, anemia, fever, skin hyperpigmentation, and other systemic manifestations that increase the diagnostic specificity of the WD[130]. Additional organ involvement, including the heart, lungs, and skin, may also occur. The final and most severe stage is the neurological phase, which substantially increases mortality[130]. Symptomatic neurological involvement occurs in 10%-40% of patients, with headache, cognitive impairment, and eye movement disorders[130].

Diagnosis relies on identifying foamy or amorphous macrophages in the duodenal lamina propria containing PAS-positive, diastase-resistant, but Ziehl-Neelsen-negative granules[130]. Additional histopathological findings include villous blunting and lymphangiectasia[130]. Although PAS staining is widely used, it lacks specificity, as PAS-positive foamy macrophages can also be observed in infections caused by Mycobacterium avium, Bacillus cereus, Corynebacterium, Histoplasma, and other fungi[131]. Depending on the affected organ system, PAS-positive cells may be detected not only in GI biopsy samples but also in cerebrospinal fluid, brain biopsies of patients with CNS involvement, or cardiac valve samples from culture-negative endocarditis[131]. Advances in molecular diagnostics, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have significantly improved the detection of T. whipplei, increasing the diagnostic accuracy for this commonly overlooked infection[130,131]. Asymptomatic central nervous system involvement, detectable by PCR in cerebrospinal fluid, is observed in 50% of cases[130]. Quantitative real-time PCR of stool and saliva serves as a useful initial screening method; however, validating its specificity remains crucial[131].

Antibiotic regimens capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier are effective in most WD patients and improve prognosis. However, relapse with severe neurological involvement or the development of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is associated with poor outcomes[130].

Giardia lamblia is a globally prevalent protozoan with significant clinical heterogeneity across infected populations. Although it is a major contributor to pediatric malnutrition and growth retardation in developing regions, it rarely causes life-threatening diarrhea[132]. Notably, immunocompromised patients, such as those with CVID, exhibit increased susceptibility to giardiasis and require clinical vigilance[133]. The clinical spectrum ranges from asymptomatic carriage to severe malabsorption syndrome[3], with mucosal findings varying from near-normal morphology to VA[134]. Diagnostic evidence includes microscopy, antigen testing, and PCR detection in stool, as well as direct identification of the parasite in duodenal samples or aspirates[3]. Histopathology reveals mucosal inflammation characterized by neutrophilic infiltration, IEL, villous blunting and expansion, and prominent lymphoid aggregates[135].

Iatrogenic causes include drug-induced enteropathy (angiotensin II receptor blockers, particularly olmesartan, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate and chemotherapy), GVHD, transplanted small intestine disease and radiotherapy. This article focused on angiotensin II receptor blocker-induced enteropathy, which has been increasingly recognized in recent years, and GVHD, which has many overlapping pathological features with the aforementioned diseases.

Since the first report in 2012 of 22 cases of severe chronic diarrhea following olmesartan use[136], numerous studies have investigated whether olmesartan truly causes enteropathy[137-142]. Two large cohort studies revealed that long-term (over 1 year) and high-dose use of olmesartan in older patients is associated with an increased risk of malabsorption enteropathy[141,142]. A recent systematic review revealed that olmesartan-associated enteropathy (OAE) is the most common angiotensin II receptor blocker-induced enteropathy (ARB-E) (89.6%), followed by valsartan (3.6%), telmisartan (2.2%), irbesartan (1.6%), losartan (1.6%), candesartan (1.1%), and eprosartan (0.5%)[2].

OAE exhibits over 70% positivity for HLA-DQ2/DQ8. But unlike CeD, it is not essential for the pathogenesis of OAE[136,137]. The impairment of TGF-β signaling, which affects Treg and intestinal homeostasis, was initially hypothesized to be involved in the potential pathogenesis of OAE, but some studies contradict this hypothesis[2,136,143]. Current research suggests that the IL-15 signaling pathway and damage to the tight junction protein ZO-1 may play a role[143]. Furthermore, given its similarity to AIE, underlying immune dysregulation is a possible contributing factor[144].

ARB-E is characterized by severe diarrhea (97%) and weight loss (84%, median 13 kg), with a high percentage of hospital admissions (95%)[2]. Duodenal VA was reported in 89% (164/183) of ARB-E patients[2]. Patients without VA develop diarrhea (73.7%) significantly less frequently than those with VA (99.4%)[2].

In addition to small bowel involvement, 23/164 patients also presented with gastric involvement (mostly lymphocytic gastritis), 20/164 patients presented with colon involvement (predominantly microscopic colitis), and 12/164 patients presented with pangastrointestinal (gastric, small bowel and colonic) involvement[2]. The small intestinal VA is the main contributor to the clinical presentation of these patients, while gastric and colonic pathological changes hardly impact the clinical outcome and warrant less attention[2].

The histological features of OAE are very similar to those of AIE, making the distinction between them dependent on medical history[144,145]. ARB exposure can also exacerbate the clinical and pathological conditions of patients with an established CeD diagnosis[146]. OAE is an important differential diagnosis in SNVA that should not be overlooked[147]. ARB-E can also present with IELs, similar to CeD[148], but it is strongly associated with increased subepithelial collagen, which serves as a distinctive feature distinguishing it from SNCD[145].

After ARB withdrawal, all patients recovered clinically and histologically[2,149]. The prognosis of ARB-E is generally excellent after discontinuation of the medication, and follow-up endoscopy may not be necessary or recommended[2]. Importantly, switching to a different class of antihypertensive medication, rather than a different ARB, is more reasonable[2,150]. Beyond ARB withdrawal, treatment for AIE (steroids and/or immunosuppressants) might be effective and sometimes necessary for achieving remission in OAE patients[137,144].

GVHD arises when donor lymphocytes recognize host histocompatibility antigens as foreign and initiate an immune response that secretes proinflammatory cytokines (IL-2, IL-12, interferon-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α)[151,152]. Acute and chronic GVHD were initially classified on the basis of whether onset occurred before or after 100 days post-transplantation, while the refined consensus now differentiates them on the basis of disease features[153].

Voluminous secretory diarrhea is the main symptom of acute lower GI GVHD, with severe cases presenting with abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, and hematochezia. Acute upper GI GVHD is characterized by anorexia, nausea, and vomiting[153]. Endoscopic findings of acute GVHD are nonspecific and may range from a near-normal appearance to VA[154], edema, tortoise shell-like mucosae, erythema, erosion, ulcers, bleeding, and ileocecal valve atrophy, making biopsies essential[151,153]. A retrospective study revealed that VA in the terminal ileum is associated with more severe diarrhea, a definitive histological diagnosis, and steroid resistance in acute GVHD patients[155].

Histological findings include epithelial apoptosis, crypt loss, and denudation[153]. Apoptotic bodies may be the only finding in mild cases, whereas severe cases can exhibit cystic dilatation of glands or crypts lined by regenerative epithelium, crypt abscesses, and epithelial destruction[153]. Inflammatory infiltration is usually sparse[9], consisting mainly of mononuclear cells, with occasional scattered eosinophils and neutrophils[156]. Although the standard grading system remains controversial, GVHD histological abnormalities are generally classified into 4 grades (Table 5)[151,156-158].

Pathologic grade is correlated with clinical severity[159] and treatment response[151]. GVHD treatment relies on immunosuppressive therapies, with glucocorticoids used as the first-line treatment[160]. Treatment efficacy was reported to be highest for grade 1 GVHD (92.3%) but gradually decreased with increasing grade: 86.1% for grade 2, 80.0% for grade 3, and 36.8% for grade 4[151]. In addition, histologic changes, such as small intestinal Paneth cell loss, have also been reported to have important clinical implications. Paneth cells, which produce antimicrobial peptides to regulate microbiota homeostasis and contribute to GVHD pathogenesis[152], can be readily identified by their location and histochemical staining with lysozyme[159]. The number of Paneth cells per high-power field at diagnosis is negatively associated with non-relapse mortality of GVHD[159]. Regenerating islet-derived 3-α, a C-type lectin with antimicrobial activity produced by Paneth cells, can serve as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for both acute[161] and chronic[162] GI GVHD[152]. Severe crypt loss is associated with severe diarrhea (stool output exceeding 1000 mL/day) and a higher risk of steroid resistance and GVHD-related mortality[163]. The relationships between other histologic changes (pericapillary hemorrhage and eosinophils in the lamina propria) and disease severity still need further investigation[156].

GI involvement in chronic GVHD remains poorly characterized[164,165]. Upper esophageal webs on endoscopy serve as a diagnostic feature, but no distinct histologic markers have been established[156]. A study of 17 pediatric patients with chronic GVHD with GI involvement reported VA, glandular lesions and rare lamina propria fibrosis[164]. Glandular changes, including dilatation, atrophy, and epithelial apoptosis, resemble those of acute GVHD but are milder[164]. Both acute and chronic GVHD patients have cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD3+, CD8+, TiA1+, granzyme B-) infiltration in the lamina propria[164].

GVHD-like pathological changes in the GI tract can also be observed in other disorders, including CVID[166] and AIE[49], and additional clinical and histological information is needed for differential diagnosis. GVHD patients can also be concurrently affected by CMV, which necessitates CMV IHC staining when CMV is suspected[156].

Several diseases can cause inflammation-mediated VA, including Crohn’s disease (CD), eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE), and collagenous sprue. The former two diseases usually present inflammatory diarrhea without prominent VA or malabsorption and other relatively specific features, making their differentiating from disorders that primarily present with small intestinal VA is generally straightforward.

CD is characterized by chronic hematochezia, transmural inflammation, and discontinuous involvement of the GI tract[167]. CD most commonly affects the terminal ileum and proximal colon and is associated with multiple distinctive features, including segmental lesions, longitudinal ulcers, a cobblestone-like mucosal appearance, strictures, and fistula formation on endoscopy, as well as transmural inflammation, ulcers, crypt abscesses, and characteristic non-caseating granulomas on biopsy[1,3,168]. Duodenal involvement in CD is characterized by ACD, mucosal erosion, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, and inflamed Brunner’s glands, with granulomas and villous blunting occasionally observed[169-171].

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis, now classified as a non-eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) disorder within the spectrum of eosinophilic GI diseases, is characterized by a history of atopy and allergies, accompanied by eosinophilia in both blood and GI biopsy specimens (Figure 1D), after excluding other conditions that may cause eosinophilia[172]. In small intestinal involvement, eosinophilic infiltration may occur in the subcryptal region and lamina propria; in severe cases, it can extend into the intraepithelial compartment and villous tips, resulting in villous damage and blunting[172].

As for collagenous sprue, which used to be considered a refractory form of CeD, is still unclear and debatable. The subepithelial collagen deposition and inflammation changes in the small intestine resemble the histological findings observed in the colonic mucosa of patients with collagenous colitis (a type of MC) and in the gastric mucosa of patients with collagenous gastritis[173,174]. Collagenous deposits might represent a kind of histologic pattern of mucosal injury that can manifest in different GI segments.

The diagnostic approach for idiopathic VA (IVA) involves comprehensive exclusion of alternative etiologies through clinical, serological, and histopathological evaluations, combined with treatment response during follow-up[1]. IVA manifests as three categories with divergent outcomes[175]. Group 1 comprises transient self-resolving partial VAs, which are often associated with infectious triggers and have excellent prognoses, with a 5-year survival of 96%. Group 2 comprises persistent nonclonal VAs correlated with HLA-DQB1*0301/DQB*06, which has nonprogressive clinical courses and a 5-year survival of 100%, whereas Group 3 comprises lymphoproliferative enteropathies characterized by rapid clinical deterioration and substantially reduced survival rates, with a 5-year survival of 27%[175]. Hypoalbuminemia and age at diagnosis were major predictors of mortality in IVA patients.

Other conditions can also cause VA, but they often present with distinctive features that facilitate differentiation and generally do not pose challenges in differential diagnosis. Therefore, this review does not cover these conditions in detail. For example, in the iatrogenic group, patients with chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced enteropathy typically have a clear medical history. In the infectious group, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enteropathy can be identified through HIV testing and lymphocyte counts, whereas intestinal tuberculosis requires evidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and caseating granulomas on biopsy (although not always present).

This review summarizes the current understanding of small intestinal VA and malabsorption disorders, with an emphasis on their clinical features and key points in differential diagnosis. Nevertheless, many important questions remain unanswered. First, due to the complexity, heterogeneity, and relative rarity of these conditions, pathologists face a high learning burden. Future research should integrate advanced technologies such as computer vision and artificial intelligence to build pathological diagnostic models that can support and enhance the diagnostic accuracy of junior pathologists. Second, existing serological biomarkers, such as autoantibodies for AIE, have suboptimal sensitivity and specificity[47]. Histopathological diagnosis relies on invasive, multi-site biopsies and requires close collaboration between experienced gastroenterologists and pathologists to ensure accurate interpretation. Therefore, future efforts should focus on identifying novel non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers, for example through integration of serum proteomics and imaging omics, to further improve diagnostic efficiency and clinical management. Thirdly, aside from CeD, most disorders within this spectrum are either uncommon or geographically restricted, and existing studies are largely descriptive. To advance knowledge, broader multicenter collaborations are needed to provide more comprehensive and unbiased characterizations of clinical, endoscopic, and pathological features. In parallel, deeper investigations should combine multi-omics analyses with experimental validation to elucidate disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses. For instance, genetic testing in IEIs facilitates more precise disease classification, enhances understanding of pathogenesis, and informs targeted therapeutic strategies for specific patient subsets[176]. In addition, the long-term prognosis of these patients remains unsatisfactory, with severe malnutrition, secondary malignancies, and persistent relapses continuing to threaten survival[8,43]. Future studies should therefore aim to identify novel therapeutic targets based on mechanistic insights and establish prospective cohorts to clarify long-term outcomes. Finally, a subset of patients continues to be classified as IVA. For this group, sustained follow-up and repeated evaluations are essential to eventually uncover underlying causes or to detect life-threatening complications at an earlier stage, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Small intestinal VA is a key feature of malabsorption syndromes and may arise from a wide range of etiologies, including immune-mediated, lymphoproliferative, infectious, iatrogenic, inflammatory, and idiopathic disorders. VA represents a primary feature in some conditions, whereas in others it appears only as a secondary or uncommon finding. Diagnostic challenges frequently arise due to the diversity and overlap of clinical presentations and histopathological features across these etiologies. Histopathological assessment of the small intestine remains essential for differential diagnosis; therefore, this review systematically summarizes the pathological features of each disease, providing pathologists and clinicians with a comprehensive understanding of these rare and complex conditions.

In clinical practice, for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea, malnutrition, or other GI symptoms, it is important not to overlook subtle changes such as small intestinal VA during endoscopic evaluation. A comprehensive assessment that includes relevant laboratory tests, imaging exams, endoscopy, and biopsy as outlined in Table 6 should then be conducted to determine whether a specific etiology is present. If so, proper treatment should be initiated. For immune-mediated or inflammatory disorders, differential diagnosis might be challenging. Careful evaluation of pathological findings along with thorough interdisciplinary communication is essential. For complex cases or IVA, multidisciplinary consultation should be considered, and patients should undergo regular follow-up to monitor their condition.

| Type of enteropathy | Clinical features | Laboratory or imaging features | Endoscopic features | Histological/molecular features on duodenal biopsy | Treatment |

| Immuno-mediated | |||||

| CeD | Malabsorption, chronic diarrhea and extraintestinal manifestations | Positive serology for TTA, EmA, or DGP; HLA-DQ2/DQ8 typing | Nonspecific, VA, scalloping, flattening, and fissuring of the mucosal folds, mosaic mucosal pattern, and increased vascularity | VA, Increased IEL, Hypertrophic crypt (polyclonal IELs in RCD I and monoclonal IELs in RCD II) | GFD ± (budesonide and other agents for RCD) |

| AIE | Severe diarrhea, malabsorption with weight loss and electrolyte imbalance unresponsive to dietary restrictions | Anti-enterocyte and/or anti-goblet cell antibodies | Nonspecific, VA, edema, hyperemia; sometimes erosion, nodular changes, scalloping of plicae, mosaic mucosa; rarely ulcer | VA, decreased goblet and or Paneth cells, apoptotic bodies, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration ± increased IEL, neutrophilic infiltration | Glucocorticoid ± immunosuppressants |

| CVID | Chronic diarrhea, onset after age 2, recurrent respiratory infections | marked decrease of IgG and IgA ± low IgM | VA, edema, nodular changes | VA, lack of plasma cells, lymphoid follicles, lymphocytosis, apoptotic bodies | Immunoglobulin replacement, infection control |

| IEI | Miscellaneous, multisystem involvement | Genetic test might find pathogenic mutations | Variable | Various | Targeted treatments for specific mutation |

| Lymphoproliferative | |||||

| EATL | Related to CeD, diarrhea, abdominal pain, malaise, weight loss, fever, night sweats, obstruction, perforation, bleeding, more common in Asian population | PET-CT scan, Monoclonal T cells on flow cytometry | Edema, VA, large circumferential ulcers, sometimes plaques and strictures, rarely tumor masses | VA, large malignant cells, variable cytologic atypia and pleomorphic, mixed inflammatory infiltration, necrosis, vascular destruction, high Ki-67, low MATK, NKp46+, cytoplasmic CD3+, CD2+, CD7+, CD103+, CD30+, TIA-1+, perforin+, granzyme-B+, CD4-, CD5-, CD8-, CD56-, Surface CD3- and surface TCR- | Chemotherapy |

| MEITL | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, malaise, weight loss, fever, night sweats, obstruction, more common in Western population | PET-CT scan, Monoclonal T cells on flow cytometry | deep ulcer, rigid intestinal segments or VA, swollen, mosaic mucosa, shallow ulcers | Monomorphic, medium-sized malignant cells with epitheliotropism, rare necrosis, high Ki-67, high MATK, NKp46+, CD3+, CD4-, CD5-, CD8+, CD56+, CD30-, TIA1+/-, perforin+/-, granzyme-B+, TCRγδ (> TCRαβ) | Chemotherapy |

| ITCL/LPD-GI | Protracted, persistent course, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss | Monoclonal T cells on flow cytometry | Nonspecific, nodular mucosa, erythema, erosion, ulcers or near normal | Small, mature, and clonal T-cell only infiltrate into lamina propria, without epitheliotropism or necrosis, low Ki-67, NKp46-, CD3+, CD5+, CD4+/-, CD8+/-, CD56-, monoclonal TCRαβ | No agreement (observation or steroid or chemotherapy) |

| INKLPD-GI | Asymptomatic or abdominal pain, hematochezia, diarrhea, diverticulosis | Absence of EBV | Superficial erosions, ulcers, erythematous or nodular or hyperemia mucosa | Infiltration of medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells in the lamina propria, without necrosis or vascular destruction, CD4-, CD5-, CD56+, absent TCR | Observation |

| IPSID | Malabsorption, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, subfebrile stages, finger clubbing, in developing countries | Immunoelectrophoresis and immunoselection detect α-heavy chain proteins, elevated serum IgA | Mild, atrophic nodular mucosa, thickening of intestinal folds, edema | variable degrees of VA, infiltration of clonal lympho-plasmacytes at variable stages ± lymph nodal Involvement | Antibiotics, chemotherapy |

| Infectious | |||||

| Tropical sprue | Malabsorption, related to tropical and subtropical regions | malabsorption of ≥ 2 unrelated nutrients (e.g., anemia, D-xylose absorption, fecal fat estimation, serum vitamin B12 and folate levels) | Normal or mild changes | VA, increased IEL, Increased eosinophils in lamina propria | Antibiotics + vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation |

| Whipple’s disease | Migratory arthralgia affecting large peripheral joints, followed diarrhea (steatorrhea), weight loss, fever, finally neurological involvement | PCR detection, absent rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies, or other autoantibodies, | Nonspecific changes | PAS-positive macrophage infiltration of the lamina propria, observation of T. whipplei bacilli | Antibiotics |

| Comorbid CMV infection | Gastrointestinal bleeding, diarrhea in immunocompromised individuals1 | CMV IgM (IgG)+, CMV DNA+ | Ulcerative, polypoid lesions | CMV inclusion bodies (owl’s eye), IHC staining+ | Antiviral agents |

| Giardiasis | Malabsorption of different severity, in developing regions/immunocompromised individuals | Antigen testing, PCR detection, microscopic exams for stool | Near-normal or VA, nonspecific changes | Direct identification of parasite, neutrophilic infiltration, increased IEL, VA, lymphoid aggregates | Antiparasitic agents |

| Iatrogenic | |||||

| ARB induced enteropathy | Severe malabsorption, weight loss, suggestive history of pharmacology | To rule out other diseases | Near-normal or VA, nonspecific changes | VA, similar to CeD/AIE | Drug withdrawal |

| GVHD | Severe diarrhea or nausea, vomiting, history of transplantation | To rule out other diseases (e.g., infections) | Near-normal or VA, nonspecific changes | epithelial apoptosis, crypt losses, and denudation, sparse inflammatory infiltration | Glucocorticoid ± immunosuppressants |

| Inflammatory (not prominent VA or malabsorption) | |||||

| Crohn’s disease | Abdominal pain, chronic bloody diarrhea, fever, malabsorption, etc. | CT/MRI reconstruction of small intestine | Segmental lesions, longitudinal ulcer, pebble-like appearance, stricture, fistula | Transmural inflammation, crypt abscess, ulcer, noncaseous granulomas | 5-ASA, glucocorticoid ± immunosuppressants ± biological therapy |

| EGE | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or serous effusion or obstruction with history of atopy and allergies | Elevated eosinophil in blood or effusion, increased IgE | Nonspecific changes | Eosinophil infiltration | Special diet, Anti-allergy treatment, glucocorticoid ± immunosuppressants |

| Collagenous sprue | Malabsorption, watery diarrhea, weight loss | To rule out other diseases | VA, nonspecific changes | Duodenal VA, subepithelial collagen deposition, increased IEL | GFD, corticosteroid, immunosuppression |

| Idiopathic | |||||

| IVA 1 | Transient course, diarrhea, weight loss, dyspepsia, infectious triggers | To rule out all other diseases | Normal or VA or mild changes | VA | None, spontaneous remission |

| IVA 2 | Persistent course, malabsorption | To rule out all other diseases | VA or nonspecific changes | VA, nonlymphoproliferative | Immunosuppressants |

| IVA 3 | Persistent course, severe malabsorption | To rule out all other diseases | VA or nonspecific changes | VA, lymphoproliferative features, monoclonal TCR | Immunosuppressants, consult hematologist |

Future efforts should focus on the development of artificial intelligence-assisted diagnostic tools, novel non-invasive biomarkers, more precise prognostic models, the identification of new therapeutic targets, molecular mechanistic investigations and internation collaborations. Addressing these gaps will ultimately improve patient outcomes and enhance our understanding of small intestinal VA.

| 1. | Schiepatti A, Cincotta M, Biagi F, Sanders DS. Enteropathies with villous atrophy but negative coeliac serology in adults: current issues. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8:e000630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schiepatti A, Minerba P, Puricelli M, Maimaris S, Arpa G, Biagi F, Sanders DS. Systematic review: Clinical phenotypes, histopathological features and prognosis of enteropathy due to angiotensin II receptor blockers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59:432-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schiepatti A, Sanders DS, Baiardi P, Caio G, Ciacci C, Kaukinen K, Lebwohl B, Leffler D, Malamut G, Murray JA, Rostami K, Rubio-Tapia A, Volta U, Biagi F. Nomenclature and diagnosis of seronegative coeliac disease and chronic non-coeliac enteropathies in adults: the Paris consensus. Gut. 2022;71:2218-2225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li M, Xu T, Ruan G, Ou C, Tan B, Zhang S, Li X, You Y, Zhou W, Li J, Li J. Comprehensive insights into pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis in adult autoimmune enteropathy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025;20:208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Theethira TG, Dennis M, Leffler DA. Nutritional consequences of celiac disease and the gluten-free diet. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schiepatti A, Biagi F, Fraternale G, Vattiato C, Balduzzi D, Agazzi S, Alpini C, Klersy C, Corazza GR. Short article: Mortality and differential diagnoses of villous atrophy without coeliac antibodies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:572-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Franzblau LE, Fuleihan RL, Cunningham-Rundles C, Wysocki CA. CVID-Associated Intestinal Disorders in the USIDNET Registry: An Analysis of Disease Manifestations, Functional Status, Comorbidities, and Treatment. J Clin Immunol. 2023;44:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li MH, Ruan GC, Zhou WX, Li XQ, Zhang SY, Chen Y, Bai XY, Yang H, Zhang YJ, Zhao PY, Li J, Li JN. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and long-term prognosis of adult autoimmune enteropathy: Experience from Peking Union Medical College Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2523-2537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | van Wanrooij RLJ, Bontkes HJ, Neefjes-Borst EA, Mulder CJ, Bouma G. Immune-mediated enteropathies: From bench to bedside. J Autoimmun. 2021;118:102609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Aziz I, Peerally MF, Barnes JH, Kandasamy V, Whiteley JC, Partridge D, Vergani P, Cross SS, Green PH, Sanders DS. The clinical and phenotypical assessment of seronegative villous atrophy; a prospective UK centre experience evaluating 200 adult cases over a 15-year period (2000-2015). Gut. 2017;66:1563-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Leonard MM, Sapone A, Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac Disease and Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: A Review. JAMA. 2017;318:647-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McAllister BP, Williams E, Clarke K. A Comprehensive Review of Celiac Disease/Gluten-Sensitive Enteropathies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57:226-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | King JA, Jeong J, Underwood FE, Quan J, Panaccione N, Windsor JW, Coward S, deBruyn J, Ronksley PE, Shaheen AA, Quan H, Godley J, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Lebwohl B, Ng SC, Ludvigsson JF, Kaplan GG. Incidence of Celiac Disease Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:507-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Singh P, Arora S, Singh A, Strand TA, Makharia GK. Prevalence of celiac disease in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1095-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bai JC, Fried M, Corazza GR, Schuppan D, Farthing M, Catassi C, Greco L, Cohen H, Ciacci C, Eliakim R, Fasano A, González A, Krabshuis JH, LeMair A; World Gastroenterology Organization. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines on celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Semrad C, Kelly CP, Greer KB, Limketkai BN, Lebwohl B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines Update: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:59-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 86.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Adelman DC, Murray J, Wu TT, Mäki M, Green PH, Kelly CP. Measuring Change In Small Intestinal Histology In Patients With Celiac Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:339-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1185-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1142] [Cited by in RCA: 1223] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Robert ME. Gluten sensitive enteropathy and other causes of small intestinal lymphocytosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2005;22:284-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue'). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1437] [Cited by in RCA: 1355] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Corazza GR, Villanacci V, Zambelli C, Milione M, Luinetti O, Vindigni C, Chioda C, Albarello L, Bartolini D, Donato F. Comparison of the interobserver reproducibility with different histologic criteria used in celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:838-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Biagi F, Vattiato C, Burrone M, Schiepatti A, Agazzi S, Maiorano G, Luinetti O, Alvisi C, Klersy C, Corazza GR. Is a detailed grading of villous atrophy necessary for the diagnosis of enteropathy? J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:1051-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | N Marsh M, W Johnson M, Rostami K. Mucosal histopathology in celiac disease: a rebuttal of Oberhuber's sub-division of Marsh III. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8:99-109. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Schiepatti A, Savioli J, Vernero M, Borrelli de Andreis F, Perfetti L, Meriggi A, Biagi F. Pitfalls in the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease and Gluten-Related Disorders. Nutrients. 2020;12:1711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lebwohl B, Bhagat G, Markoff S, Lewis SK, Smukalla S, Neugut AI, Green PH. Prior endoscopy in patients with newly diagnosed celiac disease: a missed opportunity? Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1293-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Taavela J, Koskinen O, Huhtala H, Lähdeaho ML, Popp A, Laurila K, Collin P, Kaukinen K, Kurppa K, Mäki M. Validation of morphometric analyses of small-intestinal biopsy readouts in celiac disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Biagi F, Bianchi PI, Campanella J, Zanellati G, Corazza GR. The impact of misdiagnosing celiac disease at a referral centre. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:543-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Volta U, Caio G, Boschetti E, Giancola F, Rhoden KJ, Ruggeri E, Paterini P, De Giorgio R. Seronegative celiac disease: Shedding light on an obscure clinical entity. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:1018-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gustafsson I, Repo M, Popp A, Kaukinen K, Hiltunen P, Arvola T, Taavela J, Vornanen M, Kivelä L, Kurppa K. Prevalence and diagnostic outcomes of children with duodenal lesions and negative celiac serology. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |