Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.111187

Revised: August 17, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 171 Days and 18 Hours

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a linear double-stranded DNA herpesvirus, is univer

Core Tip: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is widespread in the population, often causing EBV-related intestinal disease in immunocompromised groups - including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, who are susceptible to opportunistic EBV infection due to drug-induced immunosuppression. Patients with initial EBV-related intestinal symptoms require differentiation between EBV-associated enteritis and IBD complicated by EBV infection, while relapsed confirmed IBD cases should rule out concurrent EBV infection or reactivation. This review examines the distinctions and connections between EBV-related intestinal diseases and IBD, analyzes management strategies for IBD with EBV infection, and highlights EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders.

- Citation: Li SY, Jia J, Xu LZ, Zheng K. Relationship between Epstein-Barr virus and inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(48): 111187

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i48/111187.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.111187

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), also defined as human herpesvirus 4, is a DNA oncovirus of the lymphotropic virus. It is primarily transmitted through body fluids, especially saliva, and it is estimated to infect between 90% and 95% of adults worldwide, establishing a lifelong latent infection[1,2]. In healthy hosts, primary EBV infection during early childhood (particularly in infancy) is mostly asymptomatic or causes mild pharyngitis and febrile viral upper respiratory infections. Primary infection in adolescence or early adulthood frequently exhibits symptoms consistent with infectious mononucleosis (IM). More than 50% of patients diagnosed with IM present with the triad of fever, lymph node enlargement, and angina; splenomegaly, rash, eyelid edema, and hepatomegaly each occur in more than 10% of patients. Less common complications include hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, myocarditis, hepatitis, interstitial pneu

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is defined as a chronically relapsing, idiopathic inflammatory disorder of the alimentary canal, classified as ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), or unclassified IBD. These subtypes differ primarily in the location and depth of inflammation. UC is typified by a diffuse form of inflammation affecting mucosal and submucosal areas, CD involves transmural inflammation, and unclassified IBD presents with mucosal inflammation. As a chronic non-communicable disease, IBD affects approximately 0.3%-0.5% of the global population[6]. The patho

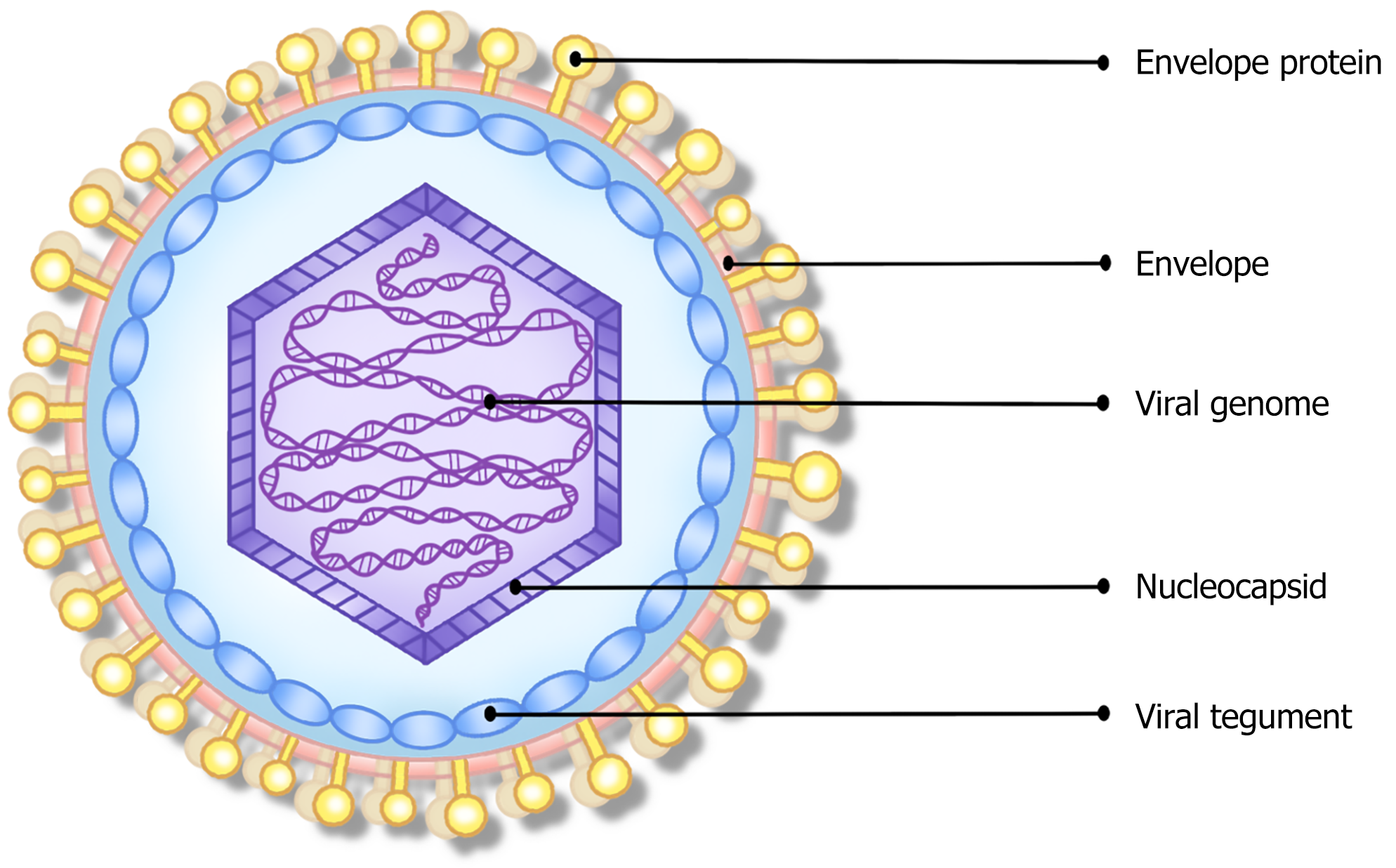

Similar to other herpesviruses, EBV is spherical, measuring approximately 180 nm. Its structural composition comprises the viral genome, nucleocapsid, viral tegument, and envelope parts, in sequence from the inside to the outside (Figure 1). The core structure of the nuclear sample is a linear double-stranded DNA genome, having an average length of 172 kb, encoding more than 85 proteins and multiple non-coding RNAs, surrounded by the nucleocapsid, and covered by the envelope[8,9]. During lytic infection, the viral genome actively replicates and infects cells in a linear way; but during latent infection, the viral genome becomes a closed circular plasmid in the host nucleus, that behaves similarly to host DNA and replicates along with host cell division[10]. The viral tegument is a protein layer unique to herpes viruses that lies between the capsid and envelope. It is hypothesized that tegument proteins regulate the viral envelope formation[11]. The envelope originates from the host cell's nuclear membrane and displays numerous virus-encoded glycoproteins essential for host cell infection. More than 10 glycoproteins have been identified, including gp350/220, gB, gH, gL, gp42, gp85, gM, gN, gp150, gp78/gp55, and so on. These glycoproteins mediate viral adhesion, fusion, and immune evasion by binding to particular receptors or co-receptors on the different target host cells[11-14]. The relevant receptors bound by each envelope glycoprotein, and their functions, are further delineated in Table 1.

| Protein | Gene | Target cells and related receptors/co-receptors | Type | Expression | Function |

| gp350/gp220 | BLLF1 | T-cell CR2/CD21 | Single pass type1 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Adhesion and endocytosis |

| B-cell CR1/CD35 and CR2/CD21 | Adhesion and endocytosis | ||||

| Epithelial cells CR2/CD21 | Adhesion | ||||

| gB | BALF4 | Epithelial cells neuropilin-1 (NRP1) | Single pass type1 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Endocytosis and fusion |

| gH | BXLF2 | gH/gL heterodimers bind to Epithelial cells' NMHC-IIA/integrin/EphA2, gH/gL/gp42 heterotrimers bind to B-cell HLA-II | Single pass type1 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Adhesion and fusion |

| gL | BKRF2 | Single pass type2 membrane | Late lytic/structural | ||

| gp42 | BZLF2 | gH/gL/gp42 heterotrimers bind to B-cell HLA-II | Single pass type2 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Triggering of fusion and immune evasion |

| BMRF2 | BMRF2 | Epithelial cells integrins | Multispanning membrane | Late lytic/structural | Epithelial cells adhesion/fusion and spread |

| BDLF2 | BDLF2 | Epithelial cells integrins | Single pass type2 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Epithelial cells adhesion/fusion and spread |

| BARF1 | BARF1 | Epithelial cells and B-cells soluble CSF-1 receptors | secreted | Early lytic/Late lytic | Immune evasion: B cells expressed in early lytic, epithelial cells expressed in latency |

| gp150 | BDLF3 | Surrounding the surface of APC HLA-I/HLA-II/CD1d antigen complexes | Single pass type1 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Targeting HLA-I, II/CD1d antigen complexes of APC prevents antigen-presenting molecules from binding to TCR, primarily by affecting antigen presentation to T cells to achieve immune escape |

| gN | BLRF1 | gM/gN | Single pass type1 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Assembly and release: Mainly guide the nucleocapsid to the budding site for secondary envelopment, and then promotes viral release by increasing cell membrane permeability |

| gM | BBRF3 | Multispanning membrane | Late lytic/structural | ||

| gp78/55 | BILF2 | Epithelial cells (possible) | Single pass type1 membrane | Late lytic/structural | Promote viral replication |

| GPCRs | BILF1 | Chemokine receptor | Multispanning membrane | Immediate early/early | Immune evasion and spread by down-regulating MHC I molecules of host cells |

Adsorption and entry into cells: EBV adheres to different recipient cells through envelope glycoproteins and mediates the fusion of the host cell membrane with the virus’ envelope. Through endocytosis, the nucleocapsid enters the host cytoplasm, and viral uncoating then injects viral DNA into the host cell nucleus[15].

Replication: EBV replication modes are divided into lytic replication and latent replication. Lytic replication, also known as lytic infection, replicates viral DNA along with host DNA. The genes expressed in viral lysis are divided into three consecutive stages (immediate-early, early, and late), and these genes are coordinately expressed in a cascade reaction[10]. Latent replication, also known as latent infection, mainly expresses a limited subset of viral genes and non-coding RNAs, including six nuclear antigen genes (EBNAs; EBNA-1, EBNA-2, EBNA-3A/3B/3C, and EBNA-LP), three latent membrane protein genes (LMPs; LMP-1 and LMP-2A/B), non-coding RNAs (EBER1, EBER2, BARTs and BHRF1) and microRNAs (miRNAs)[16,17]. The linear EBV DNA from lytic-replication becomes a circle-shaped episome within the nucleus of hosts and attaches to the host’s DNA via EBNA-1, replicating along with the cellular cycle of the host cell and resulting in the transmission of the virus to progeny cells[18]. Then, different patterns of genes are expressed based on the type and state of the infected cells (resting or proliferating).

Reactivation: In healthy hosts, EBV reactivation into lytic infection is essential for viral transmission and replenishing the latent infected host pool. EBV reactivation is primarily achieved through the regulatory stages: Specific DNA sequences are demethylated in the circular EBV episome, or the B-cell receptor signaling pathway is activated. This causes the immediate-early genes BZLF1 (also called ZTA, ZEBRA, and Z) and BRLF1 (also named RTA and R) to be expressed. These genes then control the transcription of late genes and the replication of viral DNA. Ultimately, viral replication and egress occur to continue infecting host cells, or to be shed into saliva at low levels for subsequent transmission to new individuals. In this process, both the expressed early and late antigens are recognized as targets for specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes[19-22].

During initial host infection, EBV glycoproteins in saliva bind to epithelial cell receptors, mediating the process of the virion’s envelope fusion with the epithelial cell membrane and subsequent endocytosis, thereby infecting oropharyngeal epithelial cells. After entering the epithelial cells, EBV undergoes lytic replication to synthesize mature virions. The virus then transcytoses across the epithelial cell layer to facilitating the infection of naive B cells within the locally infiltrated Waldeyer's tonsillar ring (local lymphoid tissue). The transcription factor EBNA2 regulates the growth and transformation of infected naive B cells into immortalized lymphoblasts[23]. Lymphoblasts reside exclusively within lymph nodes, and naive B cells are particularly susceptible to immortalization into proliferating lymphoblasts, making them preferential targets for viral infection[24,25]. The lymphoblasts migrate to the germinal center. Driven by EBV, the infected B-lymphocytes multiply and evolve into effector B-lymphocytes, also termed plasma cells, and memory B-lymphocytes. Within memory B cells, EBV inhibits the synthesis of viral proteins like EBNA2, switching to a default program. These memory B cells then undergo migration into the blood circulation of the body, becoming quiescent memory B cells where they persist long term[26,27]. Additionally, EBV can directly infect memory B cells or Langerhans cells[28-31]. EBV-carrying B cells or Langerhans cells can infect epithelial cells by contacting their basolateral surface via cell adhesion molecules[32,33]. EBV released from already-infected epithelial cells can also directly infect neighboring epithelial cells through lateral cell membranes[34,35].

Memory B cells function as a reservoir for EBV, establishing lifetime dormant infections[16,27]. This process is continuously monitored by cytotoxic T cells and NK cells, and the virus seldom advances to a proliferative phase. However, under certain conditions such as hypoxia, DNA damage, persistent inflammatory response, implementation of immunosuppressive therapeutics, or concurrent infection with other pathogens, the capacity of the immune system to keep EBV under surveillance is weakened, leading to the ultimate transformation of memory B cells and the initiation of the lytic phase of EBV[36,37]. This process eventually generates new infectious virus corpuscles that infect epithelial cells, and B cells that replicate within epithelial cells[37-39].

The vast majority of individuals retain lifelong protection against EBV. Although EBV may sporadically reactivate, it is rapidly extinguished. In addition to defensive barriers like the integument and mucous membranes, the body initially controls EBV infection through the innate immune response (also known as non-specific immunity). Following viral invasion, the specific receptors on innate immune cells identify EBV molecular patterns. These cells include dendritic cells, NK cells, invariant NKT cells, and B lymphocytes. This recognition elicits a signaling cascade, culminating in the secretion of antiviral factors such as various cytokines, chemokines, and type I interferons (IFNs). It also activates the adaptive immune response, thereby blocking infection, lysing the virus, and effectively limiting EBV infection[40,41].

EBV achieves immune evasion through multiple strategies, including restricting its own gene expression; inhibiting the TLR-NFκB, RIG-I, and IFN signaling pathways; interfering with antigen presentation; suppressing CD8+ T-cell responses; and inhibiting apoptosis[42,43]. The virus persists latently within B cells in most people. However, in some immunocompromised individuals, the virus is found in both B cells and T cells[44,45]. After primary infection of EBV, the latent-lytic infection cycle recurs repeatedly, expressing multiple EBV genes. These viral genes share cross-reactive epitopes with the host's normal tissue proteins, inhibit the host's adaptive immunity, or promote the excretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This raises the host immune system dysregulation and, in conjunction with other pathogenic factors, can trigger autoimmune diseases[46,47].

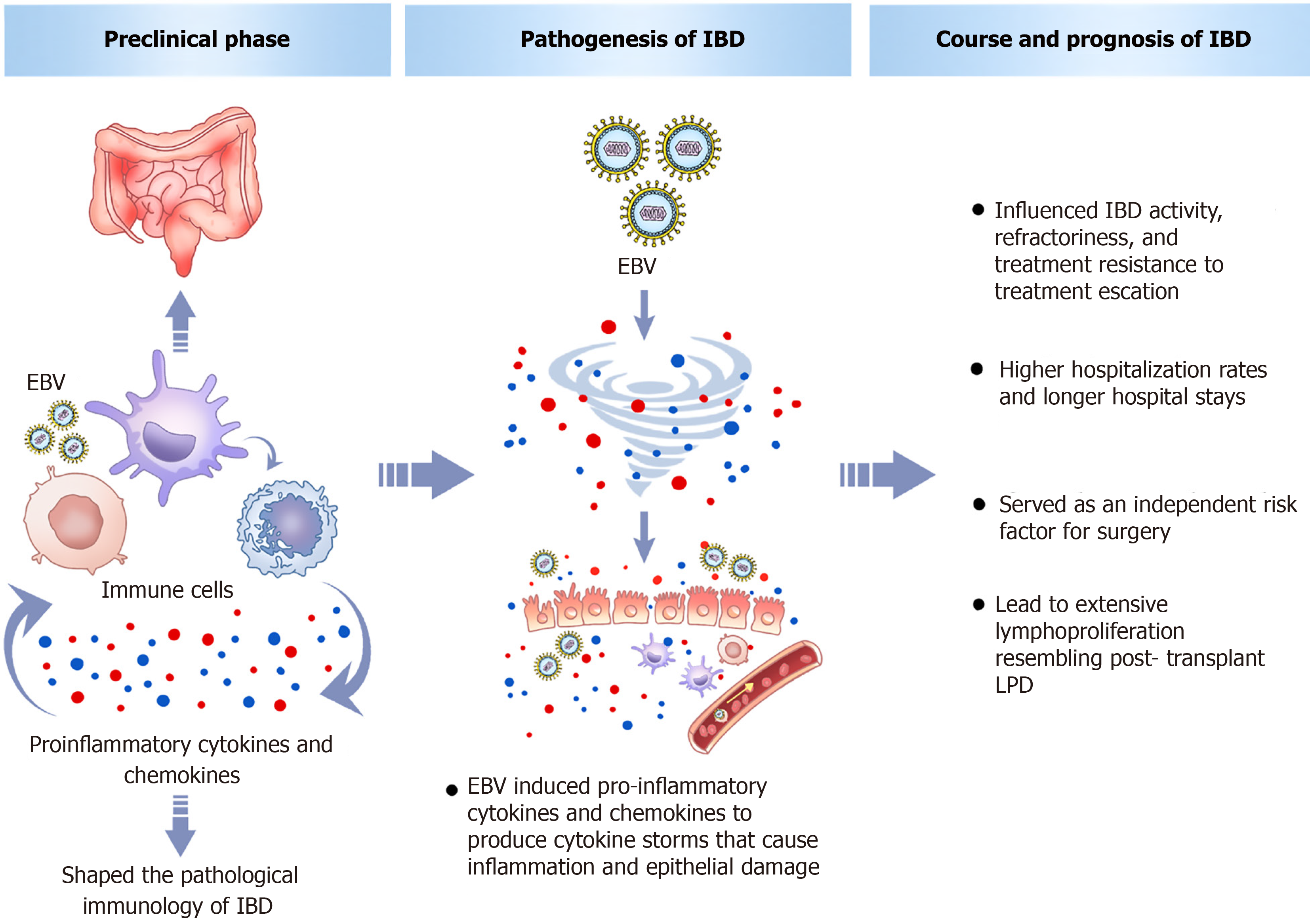

A study on the preclinical stage of IBD suggests that its development starts in high-risk persons before progressing through several distinct sub-stages, including preclinical disease initiation, a disease expansion period lasting about two years, after which the disease is diagnosed[48]. Changes of the gut observed during the preclinical phase include immune systems dysregulation, shifts in microbiome, higher permeability, glycomic changes, and variations in clinical parameters. Evaluations of serum biomarkers in patients in the preclinical stage of IBD have found that chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) is involved in changes that alter immune and barrier functions, contributing to the development of IBD[49,50]. An acute attack of EBV induces the formation of numerous cytokines and chemokines, including CXCL9. Unlike the mild immune response seen with other viral infections, the quantities of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines induced by acute infection of EBV are comparable to those in cytokine storm syndrome[51]. Animal experiments have shown that EBV DNA can lead to enhanced expression of cytokines [interleukin (IL)-17A, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α] and Toll-like receptors in the colon tissue of DSS mouse models of IBD, exacerbating colonic inflammation, increasing damage to the colonic histological structure, and thus escalating pathophysiological processes, ultimately leading to the development of IBD[52,53]. Research into EBV-triggered intestinal inflammation in IBD indicates that it might drive IBD pathogenesis by dysregulating gut adaptive and innate immunity through the EBI2-oxysterol axis and facilitating intestinal lymphoid structure formation[54-56]. A meta-analysis identified EBV as a significant risk contributor to the development of IBD[57]. A large prospective Dutch cohort study of 178 patients with new-onset IBD found distinct pathogen antibody responses years before diagnosis, including to EBV, which may influence the development of preclinical IBD[58]. Genome-wide association studies have also found that the gene encoding the G protein-coupled receptor 2 (EBI2) induced by EBV DNA is a risk gene for IBD[59]. Collectively, these findings imply that EBV could participate in establishing the subclinical inflammatory condition observed in preclinical IBD.

Therefore, we can infer that during the preclinical phase of IBD, EBV infection could act as either a precipitating event or a risk factor for the development of IBD. It participates in shaping the pathological immunology of IBD, inducing and promoting intestinal immune dysfunction or barrier impairment, thereby serving as a risk factor for IBD. Epidemiological surveys have found that EBV is more prevalent in IBD patients compared to controls, indicating its role in disease onset[60]. An artificial intelligence model was used to integrate clinical data from 287 IBD patients and perform correlation analysis, which found that EBV was associated with IBD, and the EBV infection rate in UC was significantly higher than in CD[61]. A large clinical cohort study consisting of 15931 outpatients with IM and 15931 outpatients without IM found that IM was significantly associated with IBD[62]. A nationwide Danish cohort study tracking the risk of IBD in nearly 40000 individuals hospitalized for IM showed a significant association between severe IM and the development of IBD, particularly in CD, and noted that only those diagnosed with severe IM at ages 10-16 or 17-29 years had an increased risk of IBD[63]; however, another Danish nationwide cohort study suggested that childhood EBV infection has a protective effect against CD, while adult EBV infection does not and might be associated with an increased risk of IBD, although this association lacked statistical significance[64]. This discrepancy's mechanisms relate mainly to the "hygiene hypothesis" and immune "immunological training": Childhood EBV infection stimulates and "trains" immune system development/maturation, aids in establishing intestinal immune tolerance, and protects against IBD onset[65,66]. Beyond epidemiological studies of EBV in peripheral blood comparing IBD patients and controls, which found that EBV promotes IBD occurrence, epidemiological studies of EBV in the intestinal mucosal tissue of IBD patients have also validated this conclusion[67,68]. Further histological study revealed increased synthesis and expression of IL-39 in the colon mucosa of IBD patients, with EBV-induced gene 3 being a part of the IL-39, and where the IL-39 gene is upregulated in active IBD patients and correlates with severe histological activity in UC, confirming at the histological level that EBV DNA may act as an inflammatory mediator in active IBD[69]. Interestingly, a study on IBD patients with fatigue, who exhibited different systemic antibody epitope repertoires, found that in highly fatigued IBD patients, antibody responses were mainly directed against viral antigens, especially several antigens of EBV, indicating that viral antigens, especially EBV, have a potential role in the pathophysiology of fatigue in IBD patients[70]. Overall, the main mechanisms underlying the onset and progression of IBD after EBV include the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to produce cytokine storms that cause inflammation and epithelial damage.

In addition to being involved in the preclinical phase of IBD and promoting IBD onset, EBV infection also influences IBD activity, refractoriness, treatment resistance, and prognosis. Multiple studies have pointed out that refractory IBD patients show higher EBV infection rates than controls, with EBV prevalence rising as the disease progresses; disease activity severity correlates positively with intestinal mucosal viral levels[71-78]. One of these studies pointed out that the specific mechanism by which EBV exacerbates IBD might involve the spread of opportunistic viral particles from immune cells to epithelial cells in inflamed mucosa, leading to active viral replication and significant tissue harm[78]. Furthermore, a minority of IBD patients receiving immunotherapy experience transient high-level EBV viremia associated with disease flares[79-83]. Additionally, the anti-viral capsid antigen IgA subtype shows a highly significant correlation with severe UC, and UC patients with latent EBV infection are more likely to exhibit pancolonic lesions[84,85]. The latest study revealed that EBV activates macrophage pyroptosis by upregulating glycolysis, causing EBV-infected macrophages to exhibit excessive inflammatory responses that disrupt the intestinal barrier and exacerbate UC, thereby elucidating the role of EBV in UC pathology and the manner in which it aggravates UC[86].

Regarding the increase in IBD treatment resistance caused by EBV, a study showed that EBV-positive IBD patients tend to exhibit more severe histological activity and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration than EBER-negative IBD patients, and they require steroids more frequently, need more frequent treatment escalation (including immunosuppressants and biologics), and have higher rates of treatment failure[81]. Several clinical epidemiological investigations concluded that the resistance of IBD patients to conventional therapy may be positively related to the viral load in the lesional mucosa, and refractory IBD patients exhibit high viral DNA loads in both intestinal and immune cells, while the group responsive to standard therapy has lower viral levels[74-76]. Research at the cellular level of EBV-induced IBD treatment resistance has shown that EBV-transformed B cells present infliximab (IFX)- and adalimumab (ADA)-derived peptides on their surface under IFX and ADA stimulation, with these peptides representing potential T cell epitopes that trigger anti-drug antibody responses[87], thereby unraveling the molecular mechanism of anti-TNF treatment failure.

In terms of poor prognosis, A higher EBV load in UC patients may result in an increased need for surgery, higher hospitalisation rates, longer hospital stays, and treatment escalation[73,81]. EBV is a separate warning sign for surgery in patients of moderate-to-severe UC[88,89]. Patients with EBV receiving colectomy are more likely to have high EBV levels than those who do not, and IBD patients suffering from atypical intestinal mucosal infiltration are also associated with EBV which may lead to extensive lymphoproliferation resembling post-transplant LPD[90,91]. However, other studies have found no association between EBV infection and poor prognosis[60,83,92,93]. Notably, a retrospective study collected EBV DNA loads in blood samples from 568 IBD patients found that some EBV DNA-positive IBD patients who received azathioprine (AZA) or IFX treatment but no antiviral therapy became EBV DNA-negative on follow-up[83]. This indicates that EBV DNA positivity in IBD patients' blood also represents a self-limiting infection. Above all, impact of EBV of different clinical stages of IBD is shown in the Figure 2.

The intestinal mucosa contains abundant lymphoid tissue, and EBV, as a lymphotropic virus, is one of the common sites for EBV-related diseases. In developing countries, almost all children are EBV seropositive by age 6[94]; in developed countries, EBV infection is rare in children under 4 years old, with only 20%-25% being infected by age 5[95]. Seroprevalence rises to 70%-95% during adolescence and young adulthood, and primary infection often occurs during adolescence or early adulthood[96,97]. Regarding EBV infection status of the IBD population, the prevalence in individuals aged 18-25 years old is similar to that in the general population, with a seropositivity rate approaching 71%, and in individuals over 25 years old, the seropositive rate approaches 100%[98]. The high prevalence of EBV in the population leads to a relatively high rate of EBV-associated gastrointestinal diseases. EBV-associated gastrointestinal diseases can be categorized based on different stages of development into latent intestinal EBV infection, acute EBV enteritis, localized intestinal EBV infection, and EBV-associated LPDs with gastrointestinal involvement (including EBV-associated lymphoma). It is vital to note that a certain percentage of IBD patients have primary EBV infection. These primary infections can cause gastrointestinal diseases that clinically, endoscopically, and histologically resemble IBD, and they often co-occur with IBD, leading to misdiagnosis of IBD and misguided IBD treatment, which can be life-threatening in severe cases. The main EBV-associated gastrointestinal diseases that can lead to misdiagnosis in IBD patients are as follows.

Primary EBV infection in healthy individuals is often silent and latent, with the virus being dormant within B cells. Intestinal EBV latent infection can be detected using in situ hybridization to identify EBV miRNA (EBER) in biopsy specimens, but it is unclear how many positive cells per high-power field (HPF) can be defined as latent infection. Some studies suggest that 1-2 EBER-positive cells per HPF, with only scattered positive cells throughout the entire section, typically represents EBV non-pathogenic latent infection of no clinical significance[67,68,74]. Under stimulation by inflammation and other factors, non-specific EBV amplification occurs locally in the intestine in EBV latent infection, without elevating EBV DNA load in peripheral blood. Histologically, the number of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria of the mucosa is normal or only slightly increased, with no cellular atypia.

Acute EBV infectious enteritis is primarily a viral enteritis caused by acute EBV infection and is clinically uncommon. This EBV colitis closely resembles IBD, making misdiagnosis likely[99,100]. Currently, there is no consensus on the clinical characteristics of EBV-associated enteritis. A case report described how EBV infection during immunosuppressive therapy after organ transplantation manifested as terminal ileitis, specifically isolated terminal ileal ulcers, mimicking CD and leading to misdiagnosis[101]. A retrospective study including eight children with EBV-associated enteritis indicated that its main clinical manifestations include abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and fever, and endoscopic findings showed mucosal roughness, edema, erosions, and isolated, well-demarcated multiple ulcers, which affect the entire digestive tract. Symptoms resembled UC, but colonic biopsies were uniformly EBER-positive. Symptoms improved after enteral nutrition and antiviral treatment[102]. Acute EBV infection involving the gastrointestinal tract is very unusual in immunocompetent adults. Choi et al[103] reported a 34-year-old male with abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and anorexia whose endoscopy result was discontinuous sporadic erosions with EBV confirmed histologically, and he recovered after supportive care. Another case report described a 30-year-old immunocompetent man with persistent lower abdominal distension and mucoid hematochezia for 2 months due to acute EBV infectious colitis. His imaging suggested diffuse colonic thickening and multiple mesenteric lymph node enlargements, and endoscopy primarily showed diffuse colonic mucosal inflammation and ulcers with histopathology revealed dense lymphoid infiltration in the lamina propria and relative crypt scarcity. This patient achieved complete clinical recovery with only supportive care[104]. However, some cases of acute EBV colitis present with acute gastrointestinal hemorrhagic ulcers or even perforation, requiring colectomy or antiviral therapy for resolution[105-107]. This suggests that acute EBV infectious enteritis is essentially a self-limiting intestinal infection. Nevertheless, one reported case of acute EBV enteritis in a child was initially misdiagnosed as IBD due to similar clinical and histopathological features, subsequently progressing to CAEBV[108]. Due to the disconnect between viral load and the number of EBER1-positive cells in peripheral blood, viral colitis can exist separate from systemic involvement[76]. Therefore, it is crucial to differentiate acute EBV infectious enteritis from IBD in the initial diagnosis, and caution is warranted to avoid the potential progression of acute EBV enteritis due to immunosuppressive therapy.

Localized intestinal EBV infection typically does not present with systemic symptoms, or it may manifest as an opportunistic EBV infection superimposed on pre-existing intestinal diseases, such as IBD. IBD patients are sometimes hospitalized with fever, stomachache, and diarrhea, which are usually indicative of active or deteriorating underlying condition, but may also be due to opportunistic EBV infections. Ido Weinberg reported a patient with previously EBV-negative IBD who developed primary EBV infection while on AZA therapy. The patient presented with fever (39 °C), watery diarrhea, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly initially attributed to severe aggravation of IBD, and they began to receive high-dose corticosteroid (CS) therapy. However, clinical symptoms did not improve. Serological testing and colonic biopsies, particularly within epithelial cells, indicated EBV infection. After discontinuing steroid therapy, the gastrointestinal symptoms spontaneously resolved within 1 week[109]. The use of immunosuppressants and immu

Therefore, distinguishing gastrointestinal EBV infection from an IBD flare has significant therapeutic implications for IBD patients presenting with severe diarrhea or symptoms suggestive of primary EBV infection, particularly younger patients. Active investigation for symptomatic colonic EBV infection should be pursued through colonic biopsies and EBV-specific staining. When IBD patients develop active opportunistic EBV infection, antiviral therapy may help control the condition, and reducing rather than increasing immunosuppressive therapy may be necessary. However, specific antiviral agents (e.g., acyclovir, ganciclovir) have limited efficacy. Importantly, antiviral therapy is ineffective in cases of EBV-associated LPDs[112].

EBV most commonly leads to the development of IBD through EBV-LPDs. This is viewed both as a complication of immunosuppressive therapy for IBD and as a potential consequence of the disease process itself. EBV-LPDs are a group of LPDs caused by EBV, with a continuous spectrum of proliferative, borderline, and malignant lineages. They are common in patients with congenital or acquired immunodeficiency. The liver, spleen, bone marrow, skin, and lymph nodes are the most commonly affected organs. They can be divided into reactive proliferative diseases (including reactive lesions without malignant potential and reactive lesions with different malignant potentials), EBV-associated B-cell LPDs (EBV+B-LPDs) (such as Burkitt lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma), EBV-associated NK/T-cell LPDs (EBV+T/NK-LPDs) (such as extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma; aggressive NK-cell leukemia; and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified), and post-transplant and HIV-associated LDs[113]. In Western countries, the most common type of EBV lymphoma is EBV+B-LPD, occurring in the context of T-cell immunodeficiency, most frequently following hematopoietic stem cell or solid organ transplantation[114]. EBV+T/NK-LPD is more prevalent in East Asia and South America[45,115-118].

Although IBD itself may not confer an increased risk for LPD, EBV is a well-established contributor LPDs in IBD patients with immunosuppressive drugs[119,120]. It must be noted that a 4-month follow-up study of 32 immunosuppressive therapy-naive IBD patients found that immunosuppression did not affect EBV load in the short term[121]. Additionally, other studies suggest that extensive or long-term IBD appears to be associated with lymphoma development, with an average interval of 12 years from the diagnosis of UC to lymphoma[122,123]. EBV-positive status is observed in 44%-75% of IBD patients with lymphoma[124]. Therefore, IBD patients are susceptible to EBV during passive immunosuppression (from therapy) or inherent immunosuppression (from long-standing/extensive disease). The impaired immune system’s failure to eliminate the virus ultimately elevates the risk of LPDs driven by EBV. EBV-LPDs can present as a complication of IBD, and when they involve the gastrointestinal tract, they clinically resemble IBD, leading to potential misdiagnosis due to similar symptoms[125].

Chronic active EBV affecting the gastrointestinal tract: CAEBV is a systemic progressive LPD featuring the infiltration of EBV-infected T-cells and/or NK cells, lasting beyond 3 months. Beyond infiltrating lymphoid tissues, it can involve multiple organs throughout the body, exhibiting both systemic inflammation and clonal proliferation, and can ultimately progress to malignant lymphoma[126]. Furthermore, EBV affects the hematopoietic system, encompassing the lymphoid and myeloid lineages, by infecting hematopoietic stem cells in CAEBV patients, leading to hematologic diseases[127]. According to the latest and largest global case cohort study on CAEBV, the disease is classified into four clinical subtypes based on the predominantly involved organ system: Cutaneous type, vascular type, gastrointestinal type, and unclassified type. The cutaneous type has the highest survival rate, while the gastrointestinal type carries the worst prognosis and requires early intervention[128].

When CAEBV involves the gastrointestinal tract without underlying malignant lymphoproliferation, it may be termed chronic active EBV-associated enteritis (CAEAE)[108,129]. The site in the gastrointestinal tract most commonly affected by CAEBV is the colon, with clinical manifestations including common symptoms such as diarrhea, hematochezia, abdominal pain, and perianal ulcers, along with systemic symptoms like intermittent high fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. Endoscopic findings may show varying degrees of gastrointestinal ulcers or stricture, pathological features of transmural chronic and acute mucosal inflammation with lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration, and no significant changes in crypt architecture, occasionally with cryptitis and crypt abscesses. These features can easily lead to misdiagnosis as IBD[130,131]; while IBD and CAEAE share some pathological similarities, atypical lymphocytic infiltrates (including B cells) are more frequently observed in CAEAE[90]. CAEAE generally lacks the typical chronic architectural changes seen in IBD, such as granulomas, muscularis mucosae hyperplasia, and neural hypertrophy[131,132]. There is also a lack of diffuse crypt architectural distortion[133,134]. CAEBV involving the gastrointestinal generally progresses rapidly, with a mortality rate of up to 51% within 6 months and a very poor prognosis[130]. A study found that approximately 6% of adult CAEBV patients died from gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation[135].

The overlap in symptoms, endoscopic findings, and histopathology between CAEBV with gastrointestinal involvement and IBD makes diagnosis difficult. It is often challenging to determine whether worsening symptoms stem from CAEBV or IBD flare[136]. Some cases of CAEBV primarily present with steroid-dependent IBD or steroid- and biologic-refractory IBD, leading to misdiagnosis. CAEBV should be considered in the routine differential diagnosis of refractory enteritis[108]. Critically, the treatment approaches for CAEBV involving the gastrointestinal tract and IBD are contradictory. The inappropriate use of immunosuppressants or immunomodulators can accelerate clinical deterioration and death in CAEBV patients[137,138]. Gastrointestinal ulcers in CAEBV are a rare presentation. When ulcer morphology alone is insufficient for a definitive diagnosis, confirmation may be obtained via in situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA and the detection of EBV DNA in the bloodstream.

EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer: EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer (EBV-MCU) is a highly unusual EBV+B-LPD. EBV-MCU is primarily characterized by superficial, well-demarcated, solitary mucosal or cutaneous ulcers, occasionally presenting as multifocal lesions. It commonly affects the oropharyngeal mucosa, esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, and skin, but can also involve the genitalia, perianal region, penis, vulva, and cervix. These characteristic ulcers often mimic CD intestinal or extraintestinal manifestations[139-142] and can easily be confused with IBD, requiring careful differentiation. Besides skin ulcers, EBV-MCU can also present as pyoderma gangrenosum or subcutaneous abscesses in the skin[143,144]. Additionally, most patients lack systemic symptoms or generalized lymphadenopathy related to EBV, although regional lymphadenopathy and multifocal involvement (in 17% of cases) have been described, making diagnosis challenging. The main risk factor for EBV-MCU is immunosuppression, with elderly individuals primarily being affected by age-related immunosenescence and younger individuals by medical immunosuppression, solid organ transplantation, and primary immunodeficiency[145]. Skin and gastrointestinal manifestations are frequently linked to medical immunosuppression[146,147]. Histopathological features of EBV-MCU include circumscribed mucosal or cutaneous ulcers, atypical lymphoid cells positive for EBV, and large infiltration of polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells (such as plasma cells, histiocytes, and granulocytes), with EBV-positive atypical cells of varying sizes like Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells[145]. The outlook is generally favourable, with the condition spontaneously resolving or resolving after reducing immunosuppression[139]; however, for some persistent cases, more intensive treatment may be required[82,148]. A recent report described four cases of EBV-MCUs secondary to enterocolitis in areas treated with immunosuppressive agents, associated with refractory colitis and colonic perforation[146].

In summary, EBV-MCU can be misdiagnosed as immunosuppression and steroid-resistant IBD due to their similarity to CD intestinal or extraintestinal manifestations. Conversely, IBD patients may be misdiagnosed with recurrent IBD due to receiving immunosuppressants or immunomodulators or experiencing age-related immunosenescence. These non-specific presentations confound the diagnosis, requiring clinicians to promptly adjust their diagnostic approach.

Lymphomatoid granulomas: Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare EBV+B-LPD linked to defective immune surveillance, affecting 98% of patients in the lungs and with approximately 30% of cases also involving the central nervous system, liver, skin, and kidneys[149,150]. The manifestations of lymphoma-like granuloma in the skin mainly include two types, with the most common being multiple erythematous papules and/or subcutaneous nodules, with or without ulceration, followed by multiple sclerosis and erythematous-to-white patch lesions[151,152]. These skin findings may also mimic the extraintestinal manifestations of IBD, leading to misdiagnosis. All reported cases of IBD with lymphomatoid granulomatosis have been associated with immunosuppression and EBV[153-157]. Treatment approaches include systemic CSs, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy (rituximab) combined with cytotoxic immunochemotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)[158]. Lowering or stopping medical immunosuppression may induce disease regression in patients with low-grade conditions[159,160]. However, a subset of patients die within the first year after diagnosis[161].

XLP: XLP is an uncommon X-linked recessive primary immunodeficiency condition with two subtypes: XLP1 and XLP2. Unlike XLP1, which is driven by EBV, some XLP2 patients with EBV have IBD complications, which are mainly similar to CD[162]; however, some XLP2 patients with intestinal inflammation have no evidence of EBV infection[163]. In total, 25%-30% of patients with X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) deficiency will develop an IBD-like phenotype with a poor prognosis, and 10% of cases will even die[164-166]. IBD or IBD-like gastroenteritis caused by XIAP mutations is called XIAP deficiency-associated IBD. It is a form of Mendelian or monogenic IBD affecting individuals with an X-linked, recessive inheritance pattern. It manifests as IBD with CD features, typically presenting in childhood and rarely in older children and adults, and it affects males more than females[166-168]. XIAP deficiency is observed in up to 4% of childhood-onset IBD patients whereas it is generally absent in adult-onset IBD patients[167,169]. XIAP deficiency-associated IBD is clinically and pathologically very similar to CD, but patients often have more severe disease and respond poorly to conventional therapy. Some patients die in infancy or early childhood due to severe intestinal lesions or complications such as serious infections due to delayed diagnosis and treatment[170,171]. XIAP must be assessed in boys with severe IBD, especially with splenomegaly, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), or family IBD history. Early hematologist referral for consideration of HSCT may relieve intestinal inflammation and cut life-threatening HLH risk.

Intestinal EBV infection with HPS: HPS (also known as HLH) is a severe hyperinflammatory syndrome arising from the dysregulated activation of macrophages and lymphocytes, which results from genetic or acquired immune regulatory dysfunction. A retrospective study analyzed the symptoms of HLH in viral IBD, which showed no obvious specificity, but some patients may present with diffuse, low-density liver or spleen lesions besides hepatosplenomegaly[172,173]. Two epidemiological studies investigating HLH in pediatric IBD patients estimated that the risk of HLH is approximately 100 times higher in pediatric IBD patients than local general incidence, and common features were thiopurine exposure and primary EBV infection[174,175]. Other immunosuppressants, like CSs and IFX, may also elevate HLH risk[172]. HLH is a rapidly progressive and highly lethal disease. The median survival time of untreated HLH patients does not exceed 2 months[145,176-180]. For HLH patients, a high EBV DNA viral load indicates that active treatment intervention measures should be taken immediately, and effective early intervention can boost the outcome[181,182].

The prolonged use and increasing variety of immunosuppressants and immunomodulators have heightened the likelihood of EBV in IBD sufferers. Consensus guidelines from various countries provide recommendations on managing EBV infection in this population. The European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines state[183-185] that the combo therapy of TNF-α inhibitors and thiopurines carries a higher risk of lymphoma than thiopurine or TNF-α inhibitors alone, which the combination therapy notably escalates the occurrence of rare hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, especially among males under 30 years; patients receiving thiopurine monotherapy are also susceptible to myeloproliferative disorders. EBV is linked to higher lymphoma rates in those receiving immunosuppressant therapy who are EBV-negative. Considering these risks, ECCO recommends: Serological screening for EBV in all IBD sufferers at baseline or before initiating immunosuppressive medication, especially in the elderly and those with additional lymphoma risk elements; in EBV IgG-negative patients, drugs other than thiopurines should be considered, and EBV-seronegative IBD patients starting immunomodulator therapy should undergo monitoring of EBV serology when seroconversion (EBV IgG positive) or positive viral DNA load occurs, which indicates primary EBV infection; the immunomodulator dose should be reduced or stopped, and antiviral therapy may be considered. If EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disease develops, immediate discontinuation of immunomodulators may lead to spontaneous regression. In IBD patients who do not show spontaneous resolution or progression after discontinuation of immunomodulatory therapy, rituximab and chemotherapy may be necessary. Regarding long-term immunosuppressive regimens in children, ECCO states that weekly low-dose methotrexate as a concomitant immunomodulator has not been found to carry a risk of lymphoproliferative disease, and the strategy is in line with other recent pediatric guidelines[186,187]. In 2015, ECCO further emphasized avoiding combined immunosuppressive therapy in young male patients who may require long-term treatment[188].

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology, on the other hand, adopts slightly different approaches for managing the incidence of lymphoproliferative disease in IBD sufferers receiving thiopurine/6-mercaptopurine and TNF-α antagonist (for male and female CD patients, respectively). Regarding thiopurine use, it is recommended to use thiopurine to maintain remission in female CD patients due to the teratogenic risk of methotrexate, but there is no consensus on whether to use thiopurine to maintain remission in male CD patients; regarding the combination of IFX with thiopurine, it is not recommended that IFX be combined with thiopurine in male patients, but there is no consensus on combining thiopurine to maintain clinical remission in female CD patients[187]. The consensus panel believes that methotrexate may be a useful alternative to AZA for individuals with high-risk non-melanoma skin cancer or lymphoma, especially elderly patients[189]. In 2021, both the ECCO[184] and American Colitis Guidelines[190] proposed that infectious causes should be excluded during diagnosis, but did not specify whether EBV infection was included.

The Chinese Expert Guidelines for Pathological Diagnosis of IBD[191] propose distinguishing between IBD with EBV based on the quantity of EBER-positive cells and peripheral blood EBV DNA. If the number of EBER-positive cells is ≥ 10/HPF, with symptoms of refractory IBD, elevated activity indices, and increased peripheral blood EBV DNA copies, EBV opportunistic infection should be considered. If the number of EBER-positive cells is 1-2/HPF, with occasional positive cells seen throughout the slide and no increase in peripheral blood EBV DNA copies, there is often EBV non-pathogenic latent infection without clinical significance. If the number of EBER-positive cells is < 10/HPF, the clinical significance cannot be determined solely based on the number of EBER-positive cells and requires comprehensive clinical analysis[191]. Furthermore, the Chinese Consensus on Opportunistic Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease states that if active EBV infection is detected in an IBD patient during immunosuppressive therapy, a careful weighing of risks and benefits is required, with discontinuation of immunosuppressants considered. Close monitoring of blood counts, peripheral blood smears, liver function, and EBV serology is mandatory. If an EBV+LPD develops and is unresponsive to antiviral therapy, close collaboration with hematologists is essential to formulate an appropriate treatment plan[112]. Combined with the management opinions of various countries on IBD combined with EBV infection, we advocate that infectious causes, including EBV, should be excluded when diagnosing IBD; IBD patients should undergo serological screening for EBV before they receive immunosuppressants or immunomodulators. In addition, IBD patients should also undergo serological screening for EBV during treatment with immunosuppressants or immunomodulators. Additionally, if IBD patients experience disease exacerbation, reduced effectiveness of existing treatment, or symptoms related to IM while on immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy, EBV serological screening should be conducted promptly to rule out active EBV infection. If active EBV infection is found, strive to reduce or stop immunomodulatory treatment and consider adding antiviral treatment. Be vigilant that IBD patients with EBV infection may develop EBV-related lymphoproliferative diseases.

EBV is highly prevalent in the general population, persisting in a latent state within B cells, and with reactivation being more likely in immunocompromised individuals. EBV is implicated in the preclinical phase of IBD, correlating with its onset and progression, and influences the disease course and prognosis. For patients with gastrointestinal symptoms and EBV infection, it is crucial to differentiate between a simple EBV infection and an opportunistic EBV infection in the context of IBD. IBD patients, due to their compromised immune system or use of immunosuppressive drugs, are part of the immunocompromised population and are more susceptible to opportunistic EBV infections. For these individuals, enhanced monitoring is necessary, and the use of immunosuppressive drugs should be discontinued to prevent the occurrence of LPDs, especially HLH. Multidisciplinary collaboration is vital to formulate appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

| 1. | Williams H, Crawford DH. Epstein-Barr virus: the impact of scientific advances on clinical practice. Blood. 2006;107:862-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:481-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1156] [Cited by in RCA: 1202] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Münz C. Epstein-Barr virus pathogenesis and emerging control strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025;23:667-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maeda E, Akahane M, Kiryu S, Kato N, Yoshikawa T, Hayashi N, Aoki S, Minami M, Uozaki H, Fukayama M, Ohtomo K. Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-related diseases: a pictorial review. Jpn J Radiol. 2009;27:4-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sabeti M, Kermani V, Sabeti S, Simon JH. Significance of human cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in inducing cytokine expression in periapical lesions. J Endod. 2012;38:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769-2778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2677] [Cited by in RCA: 4496] [Article Influence: 499.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (111)] |

| 7. | Chang JT. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2652-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 902] [Article Influence: 150.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:757-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1539] [Cited by in RCA: 1631] [Article Influence: 74.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Notarte KI, Senanayake S, Macaranas I, Albano PM, Mundo L, Fennell E, Leoncini L, Murray P. MicroRNA and Other Non-Coding RNAs in Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsurumi T, Fujita M, Kudoh A. Latent and lytic Epstein-Barr virus replication strategies. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He HP, Luo M, Cao YL, Lin YX, Zhang H, Zhang X, Ou JY, Yu B, Chen X, Xu M, Feng L, Zeng MS, Zeng YX, Gao S. Structure of Epstein-Barr virus tegument protein complex BBRF2-BSRF1 reveals its potential role in viral envelopment. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Damania B, Kenney SC, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus: Biology and clinical disease. Cell. 2022;185:3652-3670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Machón C, Fàbrega-Ferrer M, Zhou D, Cuervo A, Carrascosa JL, Stuart DI, Coll M. Atomic structure of the Epstein-Barr virus portal. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen T, Wang Y, Xu Z, Zou X, Wang P, Ou X, Li Y, Peng T, Chen D, Li M, Cai M. Epstein-Barr virus tegument protein BGLF2 inhibits NF-κB activity by preventing p65 Ser536 phosphorylation. FASEB J. 2019;33:10563-10576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hutt-Fletcher LM. Epstein-Barr virus entry. J Virol. 2007;81:7825-7832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thompson MP, Kurzrock R. Epstein-Barr virus and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:803-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kelly GL, Long HM, Stylianou J, Thomas WA, Leese A, Bell AI, Bornkamm GW, Mautner J, Rickinson AB, Rowe M. An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively expressed in transformed cells and implicated in burkitt lymphomagenesis: the Wp/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Aiyar A, Aras S, Washington A, Singh G, Luftig RB. Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen 1 modulates replication of oriP-plasmids by impeding replication and transcription fork migration through the family of repeats. Virol J. 2009;6:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Takada K. Cross-linking of cell surface immunoglobulins induces Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Int J Cancer. 1984;33:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lupey-Green LN, Moquin SA, Martin KA, McDevitt SM, Hulse M, Caruso LB, Pomerantz RT, Miranda JL, Tempera I. PARP1 restricts Epstein Barr Virus lytic reactivation by binding the BZLF1 promoter. Virology. 2017;507:220-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kanda T, Yajima M, Ikuta K. Epstein-Barr virus strain variation and cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:1132-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rickinson AB, Moss DJ. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:405-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhao B, Zou J, Wang H, Johannsen E, Peng CW, Quackenbush J, Mar JC, Morton CC, Freedman ML, Blacklow SC, Aster JC, Bernstein BE, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus exploits intrinsic B-lymphocyte transcription programs to achieve immortal cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14902-14907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Babcock GJ, Hochberg D, Thorley-Lawson AD. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity. 2000;13:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 25. | Joseph AM, Babcock GJ, Thorley-Lawson DA. Cells expressing the Epstein-Barr virus growth program are present in and restricted to the naive B-cell subset of healthy tonsils. J Virol. 2000;74:9964-9971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV Persistence--Introducing the Virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;390:151-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thorley-Lawson DA. Epstein-Barr virus: exploiting the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 678] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Thorley-Lawson DA, Mann KP. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus infection provide a model for B cell activation. J Exp Med. 1985;162:45-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Roughan JE, Thorley-Lawson DA. The intersection of Epstein-Barr virus with the germinal center. J Virol. 2009;83:3968-3976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kurth J, Hansmann ML, Rajewsky K, Küppers R. Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells expanding in germinal centers of infectious mononucleosis patients do not participate in the germinal center reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4730-4735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | SoRelle ED, Reinoso-Vizcaino NM, Horn GQ, Luftig MA. Epstein-Barr virus perpetuates B cell germinal center dynamics and generation of autoimmune-associated phenotypes in vitro. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1001145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Shannon-Lowe C, Rowe M. Epstein-Barr virus infection of polarized epithelial cells via the basolateral surface by memory B cell-mediated transfer infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Walling DM, Ray AJ, Nichols JE, Flaitz CM, Nichols CM. Epstein-Barr virus infection of Langerhans cell precursors as a mechanism of oral epithelial entry, persistence, and reactivation. J Virol. 2007;81:7249-7268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang H, Li Y, Wang HB, Zhang A, Chen ML, Fang ZX, Dong XD, Li SB, Du Y, Xiong D, He JY, Li MZ, Liu YM, Zhou AJ, Zhong Q, Zeng YX, Kieff E, Zhang Z, Gewurz BE, Zhao B, Zeng MS. Ephrin receptor A2 is an epithelial cell receptor for Epstein-Barr virus entry. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Xiao J, Palefsky JM, Herrera R, Berline J, Tugizov SM. EBV BMRF-2 facilitates cell-to-cell spread of virus within polarized oral epithelial cells. Virology. 2009;388:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yiu SPT, Guo R, Zerbe C, Weekes MP, Gewurz BE. Epstein-Barr virus BNRF1 destabilizes SMC5/6 cohesin complexes to evade its restriction of replication compartments. Cell Rep. 2022;38:110411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sausen DG, Bhutta MS, Gallo ES, Dahari H, Borenstein R. Stress-Induced Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Laichalk LL, Thorley-Lawson DA. Terminal differentiation into plasma cells initiates the replicative cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79:1296-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Alternate replication in B cells and epithelial cells switches tropism of Epstein-Barr virus. Nat Med. 2002;8:594-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Taylor GS, Long HM, Brooks JM, Rickinson AB, Hislop AD. The immunology of Epstein-Barr virus-induced disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:787-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ma Z, Damania B. The cGAS-STING Defense Pathway and Its Counteraction by Viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:150-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Yuan L, Zhong L, Krummenacher C, Zhao Q, Zhang X. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated immune evasion in tumor promotion. Trends Immunol. 2025;46:386-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gram AM, Oosenbrug T, Lindenbergh MF, Büll C, Comvalius A, Dickson KJ, Wiegant J, Vrolijk H, Lebbink RJ, Wolterbeek R, Adema GJ, Griffioen M, Heemskerk MH, Tscharke DC, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Wiertz EJ, Hoeben RC, Ressing ME. The Epstein-Barr Virus Glycoprotein gp150 Forms an Immune-Evasive Glycan Shield at the Surface of Infected Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bekker V, Scherpbier H, Beld M, Piriou E, van Breda A, Lange J, van Leth F, Jurriaans S, Alders S, Wertheim-van Dillen P, van Baarle D, Kuijpers T. Epstein-Barr virus infects B and non-B lymphocytes in HIV-1-infected children and adolescents. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1323-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kimura H, Hoshino Y, Hara S, Sugaya N, Kawada J, Shibata Y, Kojima S, Nagasaka T, Kuzushima K, Morishima T. Differences between T cell-type and natural killer cell-type chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:531-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Houen G, Trier NH. Epstein-Barr Virus and Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:587380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | De Francesco MA. Herpesviridae, Neurodegenerative Disorders and Autoimmune Diseases: What Is the Relationship between Them? Viruses. 2024;16:133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Rudbaek JJ, Agrawal M, Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Jess T. Deciphering the different phases of preclinical inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21:86-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Leibovitzh H, Lee SH, Raygoza Garay JA, Espin-Garcia O, Xue M, Neustaeter A, Goethel A, Huynh HQ, Griffiths AM, Turner D, Madsen KL, Moayyedi P, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS, Deslandres C, Bitton A, Mack DR, Jacobson K, Cino M, Aumais G, Bernstein CN, Panaccione R, Weiss B, Halfvarson J, Xu W, Turpin W, Croitoru K; Crohn’s and Colitis Canada (CCC) Genetic, Environmental, Microbial (GEM) Project Research Consortium. Immune response and barrier dysfunction-related proteomic signatures in preclinical phase of Crohn's disease highlight earliest events of pathogenesis. Gut. 2023;72:1462-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Grännö O, Bergemalm D, Salomon B, Lindqvist CM, Hedin CRH, Carlson M, Dannenberg K, Andersson E, Keita ÅV, Magnusson MK, Eriksson C, Lanka V; BIOIBD consortium, Magnusson PKE, D'Amato M, Öhman L, Söderholm JD, Hultdin J, Kruse R, Cao Y, Repsilber D, Grip O, Karling P, Halfvarson J. Preclinical Protein Signatures of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Nested Case-Control Study Within Large Population-Based Cohorts. Gastroenterology. 2025;168:741-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Liu M, Brodeur KE, Bledsoe JR, Harris CN, Joerger J, Weng R, Hsu EE, Lam MT, Rimland CA, LeSon CE, Yue J, Henderson LA, Dedeoglu F, Newburger JW, Nigrovic PA, Son MBF, Lee PY. Features of hyperinflammation link the biology of Epstein-Barr virus infection and cytokine storm syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2025;155:1346-1356.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Andari S, Hussein H, Fadlallah S, Jurjus AR, Shirinian M, Hashash JG, Rahal EA. Epstein-Barr Virus DNA Exacerbates Colitis Symptoms in a Mouse Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Viruses. 2021;13:1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Karout I, Salhab Z, Sherri N, Bitar ER, Borghol AH, Sabra H, Kassem A, Osman O, Alam C, Znait S, Assaf R, Fadlallah S, Jurjus A, Hashash JG, Rahal EA. The Effects of Endosomal Toll-like Receptor Inhibitors in an EBV DNA-Exacerbated Inflammatory Bowel Disease Mouse Model. Viruses. 2024;16:624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Wyss A, Raselli T, Perkins N, Ruiz F, Schmelczer G, Klinke G, Moncsek A, Roth R, Spalinger MR, Hering L, Atrott K, Lang S, Frey-Wagner I, Mertens JC, Scharl M, Sailer AW, Pabst O, Hersberger M, Pot C, Rogler G, Misselwitz B. The EBI2-oxysterol axis promotes the development of intestinal lymphoid structures and colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12:733-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Zhang F, Zhang B, Ding H, Li X, Wang X, Zhang X, Liu Q, Feng Q, Han M, Chen L, Qi L, Yang D, Li X, Zhu X, Zhao Q, Qiu J, Zhu Z, Tang H, Shen N, Wang H, Wei B. The Oxysterol Receptor EBI2 Links Innate and Adaptive Immunity to Limit IFN Response and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2207108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Chen KY, De Giovanni M, Xu Y, An J, Kirthivasan N, Lu E, Jiang K, Brooks S, Ranucci S, Yang J, Kanameishi S, Kabashima K, Brulois K, Bscheider M, Butcher EC, Cyster JG. Inflammation switches the chemoattractant requirements for naive lymphocyte entry into lymph nodes. Cell. 2025;188:1019-1035.e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Marongiu L, Venturelli S, Allgayer H. Involvement of HHV-4 (Epstein-Barr Virus) and HHV-5 (Cytomegalovirus) in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Bourgonje AR, Andreu-Sánchez S, Gacesa R, Klompus S, Kalka IN, Leviatan S, Weinberger A, Segal E, Fu J, Zhernakova A, Vogl T, Weersma RK. DOP20 Changes in systemic antibody epitope repertoires from preclinical to established Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:i108-i110. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 59. | Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, Lee JC, Schumm LP, Sharma Y, Anderson CA, Essers J, Mitrovic M, Ning K, Cleynen I, Theatre E, Spain SL, Raychaudhuri S, Goyette P, Wei Z, Abraham C, Achkar JP, Ahmad T, Amininejad L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Andersen V, Andrews JM, Baidoo L, Balschun T, Bampton PA, Bitton A, Boucher G, Brand S, Büning C, Cohain A, Cichon S, D'Amato M, De Jong D, Devaney KL, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Ellinghaus D, Ferguson LR, Franchimont D, Fransen K, Gearry R, Georges M, Gieger C, Glas J, Haritunians T, Hart A, Hawkey C, Hedl M, Hu X, Karlsen TH, Kupcinskas L, Kugathasan S, Latiano A, Laukens D, Lawrance IC, Lees CW, Louis E, Mahy G, Mansfield J, Morgan AR, Mowat C, Newman W, Palmieri O, Ponsioen CY, Potocnik U, Prescott NJ, Regueiro M, Rotter JI, Russell RK, Sanderson JD, Sans M, Satsangi J, Schreiber S, Simms LA, Sventoraityte J, Targan SR, Taylor KD, Tremelling M, Verspaget HW, De Vos M, Wijmenga C, Wilson DC, Winkelmann J, Xavier RJ, Zeissig S, Zhang B, Zhang CK, Zhao H; International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC), Silverberg MS, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Brant SR, Radford-Smith G, Mathew CG, Rioux JD, Schadt EE, Daly MJ, Franke A, Parkes M, Vermeire S, Barrett JC, Cho JH. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3979] [Cited by in RCA: 3711] [Article Influence: 265.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 60. | Lopes S, Andrade P, Conde S, Liberal R, Dias CC, Fernandes S, Pinheiro J, Simões JS, Carneiro F, Magro F, Macedo G. Looking into Enteric Virome in Patients with IBD: Defining Guilty or Innocence? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1278-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wang Z, Chen Y, Wu Y, Xue Y, Lin K, Zhang J, Xiao Y. Enhancing Epstein-Barr virus detection in IBD patients with XAI and clinical data integration. Comput Biol Med. 2025;184:109465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Loosen SH, Kostev K, Schöler D, Orth HM, Freise NF, Jensen BO, May P, Bode JG, Roderburg C, Luedde T. Infectious mononucleosis is associated with an increased incidence of Crohn's disease: results from a cohort study of 31 862 outpatients in Germany. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Ebert AC, Harper S, Vestergaard MV, Mitchell W, Jess T, Elmahdi R. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease following hospitalisation with infectious mononucleosis: nationwide cohort study from Denmark. Nat Commun. 2024;15:8383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Agrawal M, Allin KH, Hansen AV, Colombel JF, Jess T. P1204 Childhood EBV infection is protective against IBD, while adulthood EBV infection is not: a population-based cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19:i2179-i2179. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 65. | Yu Y, Zhu S, Li P, Min L, Zhang S. Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease: a crosstalk between upper and lower digestive tract. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Netea MG, Quintin J, van der Meer JW. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 1180] [Article Influence: 78.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 67. | Ryan JL, Shen YJ, Morgan DR, Thorne LB, Kenney SC, Dominguez RL, Gulley ML. Epstein-Barr virus infection is common in inflamed gastrointestinal mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1887-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Spieker T, Herbst H. Distribution and phenotype of Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Fonseca-Camarillo G, Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Barreto-Zúñiga R, Martínez-Benítez B, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Increased synthesis and intestinal expression of IL-39 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Res. 2024;72:284-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Griesbaum MG, Vogl T, Andreu-Sánchez S, Klompus S, Kalka IN, Leviatan S, van Dullemen HM, Visschedijk MC, Festen EAM, Faber KN, Dijkstra G, Weinberger A, Segal E, Weersma RK, Bourgonje AR. P193 Fatigued patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease exhibit distinct systemic antibody epitope repertoires. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:i502-i503. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 71. | Li X, Chen N, You P, Peng T, Chen G, Wang J, Li J, Liu Y. The Status of Epstein-Barr Virus Infection in Intestinal Mucosa of Chinese Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestion. 2019;99:126-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Wang W, Chen X, Pan J, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epstein-Barr Virus and Human Cytomegalovirus Infection in Intestinal Mucosa of Chinese Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:915453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Xu S, Chen H, Zu X, Hao X, Feng R, Zhang S, Chen B, Zeng Z, Chen M, Ye Z, He Y. Epstein-Barr virus infection in ulcerative colitis: a clinicopathologic study from a Chinese area. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820930124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ciccocioppo R, Racca F, Paolucci S, Campanini G, Pozzi L, Betti E, Riboni R, Vanoli A, Baldanti F, Corazza GR. Human cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection in inflammatory bowel disease: need for mucosal viral load measurement. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1915-1926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Pezhouh MK, Miller JA, Sharma R, Borzik D, Eze O, Waters K, Westerhoff MA, Parian AM, Lazarev MG, Voltaggio L. Refractory inflammatory bowel disease: is there a role for Epstein-Barr virus? A case-controlled study using highly sensitive Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA1 in situ hybridization. Hum Pathol. 2018;82:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Ciccocioppo R, Racca F, Scudeller L, Piralla A, Formagnana P, Pozzi L, Betti E, Vanoli A, Riboni R, Kruzliak P, Baldanti F, Corazza GR. Differential cellular localization of Epstein-Barr virus and human cytomegalovirus in the colonic mucosa of patients with active or quiescent inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Res. 2016;64:191-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Wei H, Xue X, Ling Q, Wang P, Zhou W. Positive correlation between latent Epstein-Barr virus infection and severity of illness in IBD patients. 2022 Preprint. Available from: researchsquare. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 78. | Dimitroulia E, Pitiriga VC, Piperaki ET, Spanakis NE, Tsakris A. Inflammatory bowel disease exacerbation associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 79. | Barzilai M, Polliack A, Avivi I, Herishanu Y, Ram R, Tang C, Perry C, Sarid N. Hodgkin lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Portrait of a rare clinical entity. Leuk Res. 2018;71:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Reijasse D, Le Pendeven C, Cosnes J, Dehee A, Gendre JP, Nicolas JC, Beaugerie L. Epstein-Barr virus viral load in Crohn's disease: effect of immunosuppressive therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 81. | Núñez Ortiz A, Rojas Feria M, de la Cruz Ramírez MD, Gómez Izquierdo L, Trigo Salado C, Herrera Justiniano JM, Leo Carnerero E. Impact of Epstein-Barr virus infection on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical outcomes. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2022;114:259-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Goetgebuer RL, van der Woude CJ, de Ridder L, Doukas M, de Vries AC. Clinical and endoscopic complications of Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory bowel disease: an illustrative case series. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:923-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Zhou JQ, Zeng L, Zhang Q, Wu XY, Zhang ML, Jing XT, Wang YF, Gan HT. Clinical features of Epstein-Barr virus in the intestinal mucosa and blood of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:312-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Wei HT, Xue XW, Ling Q, Wang PY, Zhou WX. Positive correlation between latent Epstein-Barr virus infection and severity of illness in inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:420-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |