Published online Dec 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.114377

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: December 21, 2025

Processing time: 93 Days and 6.5 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is highly prevalent worldwide, and rising antibiotic resistance has reduced the efficacy of standard therapy, underscoring the need for simplified and better-tolerated regimens.

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and optimal dosing of vonoprazan (VPZ)-amoxicillin (AMO) dual therapy in a non-inferiority randomized trial for H. pylori eradication.

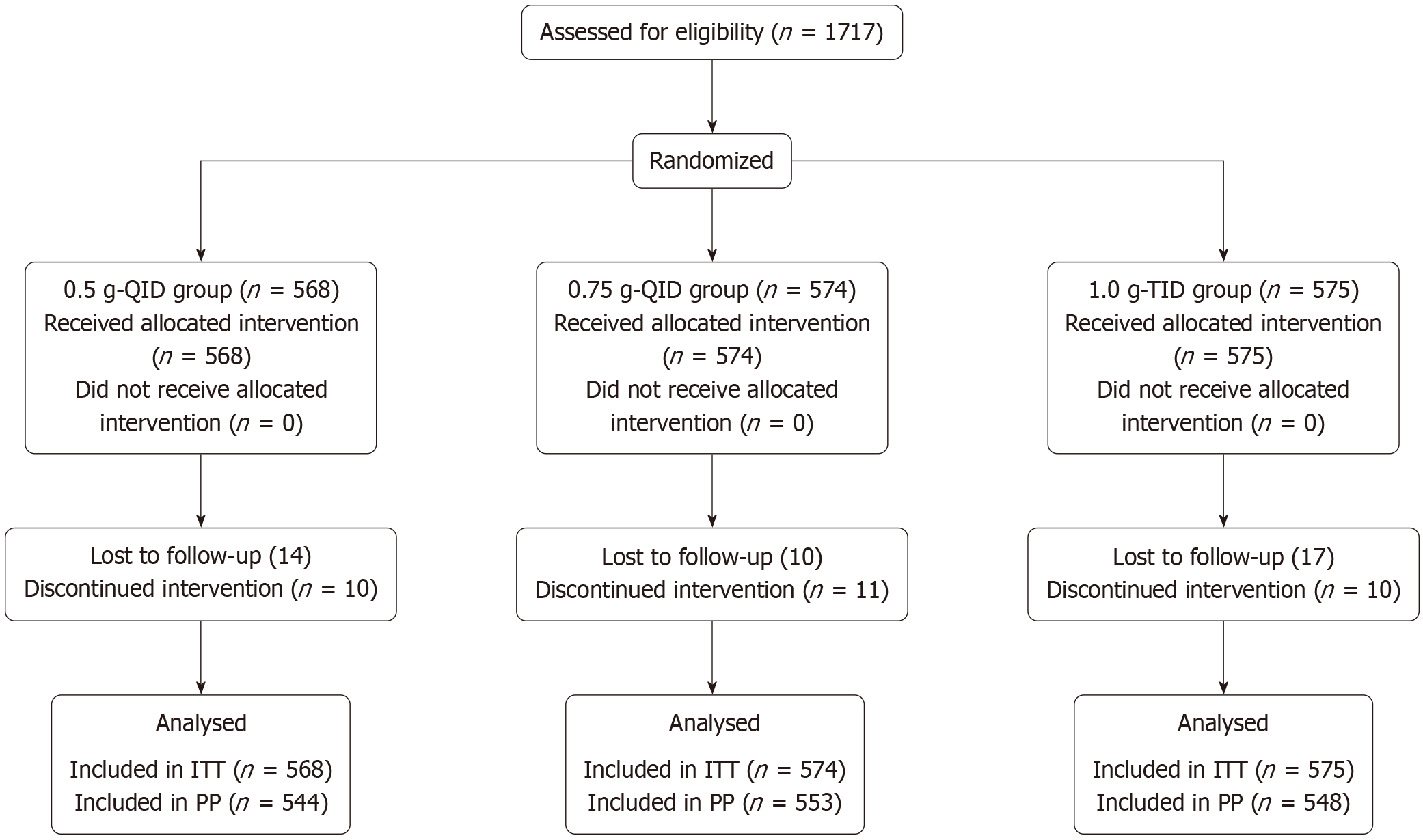

In this multi-center, randomized trial conducted at 17 hospitals in Sichuan Province, China, 1717 adults with confirmed infection were assigned (1:1:1) to 14-day regimens: (1) VPZ 20 mg BID + AMO 0.5 g QID; (2) 0.75 g QID; or (3) 1.0 g TID. The primary endpoint was the eradication rate based on intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses; secondary endpoints included adverse events (AEs) and treatment compliance.

Eradication rates were consistently high (92.35%-97.43%). In the 0.5 g QID group, ITT and PP eradication rates were 93.3% (95%CI: 91.2-95.1) and 97.4% (95%CI: 95.7-98.5), respectively, with no significant differences among groups (P > 0.05). Compliance ranged from 98.1% to 98.3%, and AEs were infrequent (5.2%-7.5%), predominantly mild gastrointestinal symptoms, which occurred least often in the 0.5 g QID group.

VPZ-AMO dual therapy achieved excellent eradication, safety, and patient compliance. All regimens were similarly effective, whereas the 0.5 g QID dosing strategy offered the most favorable balance of efficacy and tolerability, supporting its use as a first-line option in high-prevalence settings.

Core Tip: This multi-center randomized non-inferiority trial compared three vonoprazan (VPZ) plus amoxicillin (AMO) dual-therapy regimens: AMO 0.5 g QID, 0.75 g QID, and 1.0 g TID. All regimens achieved high eradication with excellent compliance and low adverse-event rates. The low-dose, high-frequency option (0.5 g QID) provided efficacy comparable to higher doses with superior tolerability, supporting dose optimization of VPZ-AMO as a practical first-line strategy in high-prevalence regions.

- Citation: Wu CQ, Zhou X, Li CP, He QL, Chen ZH, Ding SB, Deng L, Chen LL, Jiang K, Dong CK, Hu L, Zhu GB, Zhang CG, Zhang Y, Wu LL, Li W, Mao YH, Zhang H, Ai X, He YQ, Ma Y, He SY. Regional multi-center randomized trial of three vonoprazan-amoxicillin dosing regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Sichuan Province, China. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(47): 114377

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i47/114377.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.114377

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a pathogenic microorganism that colonizes the gastric mucosa for prolonged durations. About half of the global population is infected[1]. H. pylori is closely linked to chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and multiple gastric disorders[2-5]. Eradication substantially decreases the risk of these conditions and improves clinical outcomes[6,7]. International and national expert consensuses, including the Maastricht VI/Florence Consensus and the most recent Chinese guidelines, recommend active eradication in infected patients without contraindications[8,9]. Resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole used in conventional triple or quadruple therapy has continued to rise[10]. Although international recommendations advise clarithromycin susceptibility testing before use, timely access to such testing remains limited in many regions of China, reducing the practical effectiveness of standard regimens. By contrast, the resistance rate of amoxicillin (AMO) in China has remained very low (generally < 3%) for many years[11]. AMO is typically combined with potent acid suppression, as its antibacterial activity declines markedly in low-pH environments. Moreover, monotherapy with AMO does not promote resistance development in H. pylori, and main

Vonoprazan (VPZ), a potassium-competitive acid blocker, offers advantages over traditional proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), including acid stability without activation, rapid onset, prolonged suppression of gastric acid, and low interindividual variability[12]. It also demonstrates superior nocturnal acid suppression compared with esomeprazole and is not influenced by CYP2C19 polymorphisms[13]. AMO is advantageous due to its low resistance rate, availability, and cost-effectiveness in China[14].

Eradication with conventional triple therapy has declined substantially as resistance has increased. The Fifth National Consensus Report on the Management of H. pylori Infection in China (2017) documented resistance rates exceeding the international 15% alert threshold for clarithromycin (28.9%), metronidazole (63.8%), and levofloxacin (28.8%)[15]. Consequently, standard PPI-based triple therapy is no longer recommended in high dual-resistance regions unless susceptibility data are available. In such settings, guidelines endorse bismuth-based or non-bismuth quadruple regimens that combine PPIs with multiple antibiotics to maintain acceptable eradication rates[16,17]. However, these approaches are costly, have higher rates of adverse effects, and reduce adherence. Repeated therapeutic failures can further promote multi-drug resistance. VPZ-AMO dual therapy has recently gained attention as a simplified alternative with comparable efficacy and improved tolerability. A domestic randomized controlled trial using 1.0 g AMO BID for 10 days showed suboptimal eradication, whereas 14-day VPZ-AMO regimens achieved superior outcomes, potentially reflecting regional susceptibility differences[18]. Prolonging dual therapy to 14 days consistently yields > 90% eradication in diverse po

However, evidence for lower-dose strategies (e.g., 0.5 g QID) is still limited. Such dosing may offer a better balance of efficacy, adherence, and tolerability. To address this gap, the present multi-center randomized trial was designed to evaluate the eradication efficacy and safety of three VPZ-AMO dosing regimens, including the previously underexplored 0.5 g QID strategy.

This study enrolled 1717 treatment-naive patients with H. pylori infection from 34 tertiary hospitals (Class III Grade A or B) in Sichuan Province between November 2022 and March 2023 using a random number table method. Participants were assigned into three groups: (1) Standard-dose conventional treatment group (568 cases); (2) High-dose, high-frequency treatment group (574 cases); and (3) High-dose, low-frequency treatment group (575 cases).

The trial was powered to demonstrate non-inferiority of each test arm vs the reference (0.5 g QID) on the risk-difference scale with a prespecified margin of -10%, consistent with prior H. pylori eradication trials. Assuming a common era

The three groups received: (1) Standard-dose conventional group (0.5 g-QID): VPZ 20 mg twice daily (before breakfast and dinner) plus AMO 500 mg four times daily (after breakfast, lunch, dinner, and at bedtime) for 14 days; (2) High-dose, high-frequency group (0.75 g-QID): VPZ 20 mg twice daily plus AMO 750 mg four times daily for 14 days; and (3) High-dose, low-frequency group (1.0 g-TID): VPZ 20 mg twice daily plus AMO 1.0 g three times daily for 14 days.

AMO (brand name: Nomoling) was manufactured by Shijiazhuang Ouyi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (National Drug Approval Number H13023964) and supplied as 0.25 g tablets.

VPZ fumarate (brand name: Wakol) was produced by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin) (National Drug Approval Number J20200011) and supplied as 20 mg tablets.

The sex and age distribution of the three groups was as follows: (1) Standard-dose conventional group: 230 men and 338 women, mean age 46 years; (2) High-dose, high-frequency group: 207 men and 367 women, mean age 47 years; and (3) High-dose, low-frequency group: 257 men and 318 women, mean age 45 years.

(1) Adults aged 18-70 years; (2) No use of PPIs, H2 receptor antagonists, or other medications affecting H. pylori activity within 2 weeks before treatment, and no antibiotics, bismuth, or Chinese herbal medicines within 4 weeks before treatment; (3) Initial diagnosis of H. pylori positivity by 13C/14C-urea breath test (UBT), rapid urease test, or histopa

(1) Systemic lupus erythematosus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or human immunodeficiency virus infection; hepatitis B surface antigen positivity or hepatitis C virus antibody/RNA positivity; serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL (177 μmol/L); alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase > 2 × upper limit of normal, or total bilirubin > 2 × upper limit of normal; or clinically significant disease involving the central nervous system, cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, renal, metabolic, gastrointestinal, urinary, endocrine, or hematologic systems; (2) Known allergy to penicillin, AMO, or VPZ; (3) Organic gastrointestinal lesions (tumor, active bleeding, etc.); (4) Psychiatric disorders or commu

Treatment was discontinued if: (1) Intolerable adverse reactions occurred; (2) An intercurrent illness interfered with the trial; (3) The patient was lost to follow-up; or (4) Voluntary withdrawal occurred.

The technical roadmap of this study is shown in Figure 1. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee and the Clinical Pharmacy Committee (approval number KY2022272). The therapeutic agents and dosages were consistent with clinical guidelines. The trial was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200065282), conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and reported according to CONSORT guidelines.

Participants were competitively enrolled across study centers according to a pre-generated randomization list created using R software (version 4.3.2) by an independent statistician uninvolved in patient recruitment or treatment. Eligible patients were sequentially assigned to one of three treatment regimens in a 1:1:1 ratio based on the randomization sequence. Each center obtained the next available allocation number to ensure balanced enrollment across sites while maintaining strict allocation concealment throughout the process.

All treatments were prescribed by trained outpatient physicians at each participating center, who also provided verbal counseling and written instructions. To ensure protocol fidelity, all sites used a standardized drug administration plan and identical medications. Concomitant treatment of unrelated comorbidities (e.g., antihypertensive or antidiabetic drugs) was permitted and documented when applicable. Follow-up assessments were performed mid-treatment and upon therapy completion. Medication adherence was evaluated by pill counts during scheduled telephone follow-up. Adverse events (AEs) were actively monitored throughout treatment, and therapy was discontinued if clinically indicated. No prespecified interim analysis or formal stopping rules were applied.

All participants were required to undergo regular follow-up during the treatment period. Investigators contacted patients via WeChat, telephone, and other communication tools (including audio recordings) to document adherence and AEs. Smoking and alcohol consumption were strictly prohibited throughout treatment and for at least one week after discontinuation. Patients returned to the hospital ≥ 4 weeks after treatment completion to determine whether H. pylori had been eradicated.

Eradication of H. pylori was evaluated uniformly across treatment groups. Follow-up testing was conducted 4-6 weeks after therapy to avoid false-negative results from recent proton-pump inhibitor or antibiotic exposure. The 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) was used as the standard diagnostic method based on national and international consensus recommendations. A negative 13C-UBT result was defined as successful eradication. Stool antigen or biopsy-based methods were used for patients who could not undergo UBT. Follow-up procedures were performed by blinded assessors independent of treatment allocation. To minimize intercenter variability, all study sites used the same UBT analyzer and reagents under centralized quality control, and technicians received standardized training before study initiation.

Secondary outcomes included symptom relief, treatment compliance, and the incidence and severity of AEs. Symptom improvement was assessed using a structured treatment evaluation form (Table 1). The symptoms assessed included upper abdominal pain, postprandial discomfort, and loss of appetite. Symptom severity was graded as follows: 0 points (no symptoms); 1 point (mild symptoms); 2 points (moderate and tolerable); 3 points (severe, affecting work or daily life); and 4 points (very severe, significantly impairing normal life activities). The total score was the sum of individual symptom scores. Treatment efficacy was categorized as: (1) Markedly effective, defined as a post-treatment score ≤ one-third of the pretreatment score; (2) Effective, defined as a reduction > one-third but ≤ two-thirds; and (3) Ineffective, defined as a reduction ≤ one-third or deterioration. “Markedly effective” and “effective” were considered clinically effective overall. Poor adherence was defined as < 80% medication intake or ≥ 20% missed doses.

| Efficacy observation table | ||

| Symptom | Score before treatment | Score after treatment |

| Nausea | ||

| Vomiting | ||

| Loss of appetite | ||

| Abdominal distension | ||

| Abdominal pain | ||

| Diarrhea | ||

| Constipation | ||

| Belching | ||

| Acid regurgitation | ||

| Bitter taste | ||

| Heartburn | ||

| Halitosis | ||

| Total score | ||

AEs were prospectively documented throughout treatment using a standardized checklist covering gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, constipation, black stool) and systemic symptoms (headache, dizziness, rash, palpitations). Investigators blinded to allocation classified each AE as mild (transient and tolerable), moderate (causing functional limitation), or severe (interfering with normal activities).

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2). H. pylori eradication was assessed using intention-to-treat (ITT), modified ITT (mITT), and per-protocol (PP) analyses. The mITT population included all participants who received at least one dose of therapy, while the PP population included those who completed treatment and underwent a 13C-UBT ≥ 4 weeks after therapy. Participants were excluded from the PP analysis if they discontinued treatment, were lost to follow-up, or failed to complete post-treatment testing.

Continuous variables were first tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean ± SD and compared using one-way ANOVA or independent-samples t-tests, as appropriate. Non-normally distributed variables are reported as median (IQR) and compared using the Kruskal-Wallis H test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts were < 5. The primary outcome was analyzed within a non-inferiority framework, and non-inferiority was confirmed when the lower bound of the two-sided 95%CI for the eradication-rate difference exceeded -10%, the prespecified non-inferiority margin.

A total of 1717 patients were enrolled, with 568574, and 575 patients assigned to the 0.5 g QID, 0.75 g QID, and 1.0 g TID groups, respectively. Most baseline characteristics were generally comparable across the three groups (Table 2). The mean age of the 0.75 g QID group [47 (36-57) years] was slightly higher than that of the 0.5 g QID [46 (35-54) years] and 1.0 g TID groups [45 (33-55) years], and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.021, Kruskal-Wallis test). The proportion of female participants also differed significantly between groups (χ2= 8.830, P = 0.012), with the highest percentage observed in the 0.75 g QID group (63.9%) and the lowest in the 1.0 g TID group (55.3%). Rates of loss to follow-up (2.5%, 1.7%, and 3.0%) and poor adherence (1.8%, 1.9%, and 1.7%) did not differ significantly among the treatment arms (χ2= 1.411, P = 0.494; χ2= 0.037, P = 0.982). Symptom relief outcomes were also similar (χ2= 6.180, P = 0.186). The percentages of markedly effective cases increased progressively across the three groups (83.8%, 88.7%, and 91.9%), and the difference was statistically significant (χ2= 8.140, P = 0.017). The median pretreatment symptom scores were 2.0 (IQR 2.0-4.0), 3.0 (IQR 2.0-4.0), and 3.0 (IQR 2.0-4.0) and decreased after therapy to 0.0 (IQR 0.0-0.0), 0.0 (IQR 0.0-0.0), and 0.0 (IQR 0.0-0.0), with no statistically significant between-group differences (P = 0.170 and P = 0.169 for pretreatment and posttreatment scores, respectively; Kruskal-Wallis test).

| 0.5 g-QID | 0.75 g-QID | 1.0 g-TID | P value | ||

| 568 | 574 | 575 | |||

| Gender | Female | 338 (59.5) | 367 (63.9) | 318 (55.3) | 0.012 |

| Male | 230 (40.5) | 207 (36.1) | 257 (44.7) | ||

| Age [median (IQR)] | 46.0 (35.0-54.0) | 47.0 (36.0-57.0) | 45.0 (33.0-55.0) | 0.021 | |

| Lost to follow-up | 14 (2.5) | 10 (1.7) | 17 (3.0) | 0.494 | |

| Poor adherence | 10 (1.8) | 11 (1.9) | 10 (1.7) | 0.982 | |

| Symptom relief group | Asymptomatic | 340 (59.9) | 317 (55.2) | 325 (56.5) | 0.186 |

| No symptom relief | 6 (1.1) | 7 (1.2) | 9 (1.6) | ||

| Symptom relief | 208 (36.6) | 240 (41.8) | 224 (39.0) | ||

| Efficacy | Markedly effective | 171 (83.8) | 204 (88.7) | 203 (91.9) | 0.017 |

| Ineffective | 21 (10.3) | 10 (4.3) | 7 (3.2) | ||

| Effective | 12 (5.9) | 16 (7.0) | 11 (5.0) | ||

| Pretreatment score [median (IQR)] | 2.0 (2.0-4.0) | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 0.170 | |

| Post treatment score [median (IQR)] | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.169 | |

| Adverse events | 31 (5.46) | 30 (5.23) | 43 (7.48) | 0.187 |

As shown in Table 3, eradication rates were consistently high in all three dosing groups. In the ITT analysis, eradication rates were 93.31% (95%CI: 91.15-95.09) for the 0.5 g QID group, 93.55% (95%CI: 91.42-95.23) for the 0.75 g QID group, and 92.35% (95%CI: 90.11-94.17) for the 1.0 g TID group (P = 0.696). In the mITT analysis, the rates were 95.67% (95%CI: 93.84-96.98), 95.21% (95%CI: 93.33-96.55), and 95.16% (95%CI: 93.27-96.51), respectively (P = 0.911). In the PP analysis, eradication rates remained high at 97.43%, 97.11%, and 96.90% across the three groups, with no statistically significant differences (P = 0.870). Collectively, all regimens achieved eradication rates exceeding 92% in the ITT analysis and 96% in the PP analysis. The low-dose, high-frequency regimen (0.5 g QID) was non-inferior to the higher-dose regimens, providing comparable clinical benefit while potentially minimizing pill burden. These results support 0.5 g QID as a clinically efficient and practical option for H. pylori eradication, especially in high-prevalence regions.

| Dosage | 0.5 g-QID (95%CI) (%) | 0.75 g-QID (95%CI) (%) | 1 g-TID (95%CI) (%) | P value |

| ITT | 93.31 | 93.55 | 92.35 | 0.696 |

| 95%CI | 91.15-95.09 | 91.42-95.23 | 90.11-94.17 | |

| mITT | 95.67 | 95.21 | 95.16 | 0.911 |

| 95%CI | 93.84-96.98 | 93.33-96.55 | 93.27-96.51 | |

| PP | 97.43 | 97.11 | 96.90 | 0.870 |

| 95%CI | 95.73-98.46 | 95.35-98.21 | 95.09-98.05 |

No statistically significant difference was observed in the overall distribution of symptom relief among the three groups (P = 0.480). The rates of loss to follow-up were 2.5%, 1.7%, and 3.0% in the 0.5 g QID, 0.75 g QID, and 1.0 g TID groups, respectively. The proportions of asymptomatic patients were 59.9%, 55.2%, and 56.5%, while unrelieved symptoms accounted for 1.1%, 1.2%, and 1.6%. The proportions of patients reporting symptom improvement were 36.6%, 41.8%, and 39.0%, respectively. Markedly effective cases accounted for 83.8%, 88.7%, and 91.9% (P = 0.017), and the combined markedly effective plus effective rates were 89.7%, 95.7%, and 96.8%, indicating symptom improvement across all re

As shown in Table 4, all three regimens were well tolerated, with no serious AEs reported. The 0.5 g QID group demonstrated the lowest incidence of adverse reactions, with mild events such as nausea (1.8%), bloating (1.6%), diarrhea (1.4%), and abdominal discomfort (0.9%) occurring at low frequencies. No cases of loss of appetite, dry mouth, altered taste, or heartburn were reported in this group. In contrast, the 0.75 g QID and 1.0 g TID groups exhibited overall low adverse-event rates but experienced a slightly broader range of side effects, including reduced appetite, dry mouth, and taste disturbances, which were not observed in the 0.5 g QID group. Most AEs were mild gastrointestinal symptoms that resolved spontaneously or with minimal supportive care. The overall incidence of AEs was low and comparable among the three dosing schedules (5.5%, 5.2%, and 7.5%; P = 0.187).

| ADR | 0.5 g-QID | 0.75 g-QID | 1.0 g-TID | P value |

| Nausea | 10 (1.8) | 9 (1.6) | 10 (1.7) | 0.8215 |

| Vomiting | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2467 |

| Decreased appetite | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4996 |

| Abdominal distension | 9 (1.6) | 10 (1.7) | 7 (1.2) | 0.4772 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (0.9) | 4 (0.7) | 7 (1.2) | 0.5469 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (1.4) | 11 (1.9) | 8 (1.4) | 0.4996 |

| Constipation | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) | 0.6244 |

| Black stool | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4996 |

| Altered taste | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4996 |

| Xerostomia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.9) | 0.0620 |

| Bitter taste in mouth | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4996 |

| Headache | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4969 |

| Dizziness | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.6224 |

| Rash | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | 0.2493 |

| Chest tightness | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4969 |

| Palpitations | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4996 |

| Belching | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4969 |

| Heartburn | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1.0000 |

In the age-stratified analysis (Table 5), eradication and adherence rates remained consistently high across all dosing regimens and age groups. For the 0.5 g QID regimen, eradication exceeded 94% among adults aged 18-59 years and remained > 84% in older participants (60-70 years), with adherence rates close to 99%. Although a mild age-related decline in the eradication rate was observed, the difference reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). A similar pattern was identified in the 0.75 g QID group, with eradication rates > 95% in younger and middle-aged participants and 81.7% in older adults (P < 0.05). In contrast, the 1 g TID regimen showed no statistically significant age-related variation in eradication efficacy (P > 0.05). AEs were infrequent across all age strata, occurring in ≤ 10% of participants, without clinically meaningful differences between subgroups.

| Regimen | Age group | n (ITT) | Eradicated | Adherence ≥ 80% | Adverse events | P value (by age) |

| 0.5 g-QID | 18-39 | 205 | 194 (94.6) | 200 (97.6) | 6 (2.9) | < 0.05 |

| 40-59 | 285 | 270 (94.7) | 281 (98.6) | 21 (7.4) | < 0.05 | |

| 60-70 | 78 | 66 (84.6) | 77 (98.7) | 4 (5.1) | < 0.05 | |

| 0.75 g-QID | 18-39 | 188 | 179 (95.2) | 181 (96.3) | 19 (10.1) | < 0.05 |

| 40-59 | 282 | 273 (96.8) | 279 (98.9) | 7 (2.5) | < 0.05 | |

| 60-70 | 104 | 85 (81.7) | 103 (99.0) | 4 (3.8) | < 0.05 | |

| 1 g-TID | 18-39 | 234 | 214 (91.5) | 228 (97.4) | 14 (6.0) | > 0.05 |

| 40-59 | 281 | 265 (94.3) | 277 (98.6) | 28 (10.0) | > 0.05 | |

| 60-70 | 60 | 52 (86.7) | 60 (100.0) | 1 (1.7) | > 0.05 |

Overall, these findings indicate that both the 0.5 g QID and 0.75 g QID regimens achieved excellent eradication efficacy and adherence in younger and middle-aged adults. The 0.5 g QID regimen also maintained comparatively stable performance in older patients, further supporting its suitability as a practical and well-tolerated first-line option across age groups.

This large multi-center non-inferiority randomized controlled trial demonstrated that all three dosing regimens achieved eradication rates > 92% in the ITT analysis and > 96% in the PP analysis, surpassing the 90% benchmark recommended by the 2022 Chinese H. pylori guidelines and the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Importantly[20], the low-dose, high-frequency regimen (0.5 g QID) was statistically non-inferior to higher-dose regimens while achieving excellent compliance (> 98%) and favorable safety outcomes, thereby filling the previous gap in evidence regarding whether prolonged low-dose regimens can maintain eradication efficacy. These results suggest that optimizing dose frequency, rather than simply increasing individual doses, can sustain high eradication rates while reducing treatment burden and adverse effects[11,21].

The findings are consistent with recent trials and real-world data from Japan, Korea, and other Asian countries[22], where VPZ-based dual therapy has shown robust eradication performance and potent acid suppression even in settings with rising antibiotic resistance[23]. Prior studies typically adopted fixed high-dose regimens (e.g., 0.75 g QID or 1.0 g TID), leaving uncertainty regarding comparative outcomes across different dosing strategies[24-26]. By systematically evaluating three clinically relevant regimens, this study provides the first large-scale evidence showing that more frequent administration of a lower individual dose can yield equivalent eradication, addressing a key gap highlighted in recent international consensus statements.

All three VPZ-AMO regimens demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with AEs occurring in < 8% of patients. Most AEs were mild gastrointestinal symptoms that resolved without the need for treatment interruption. The 0.5 g QID regimen had the lowest adverse-event incidence while delivering non-inferior eradication efficacy, indicating that dose escalation beyond 0.5 g does not further improve treatment effectiveness but may slightly increase gastrointestinal discomfort. These observations support the clinical adoption of the 0.5 g QID regimen as a practical, well-tolerated first-line strategy.

Compared with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (BQT), the VPZ-AMO dual regimen represents a simpler and lower-burden alternative[27]. Although BQT can also achieve high eradication, it is commonly associated with gas

According to the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus, effective H. pylori eradication requires potent and sustained gastric acid suppression to maintain intragastric pH between 6 and 7[19]. Existing trials have shown that the 14-day VA dual regimen is superior to BQT in several respects: VPZ is stable under acidic conditions, acts rapidly, and delivers strong acid suppression from day one; conventional PPIs have weaker pKa values (3.8-5.0), shorter half-lives (0.5-2.0 hours), and less consistent pH control; and the efficacy of PPIs is strongly influenced by CYP2C19 polymorphisms, whereas VPZ efficacy is unaffected by genotype differences, resulting in more consistent clinical outcomes[30-32].

AMO is a time-dependent antibiotic, and its bactericidal effect depends on maintaining plasma concentrations above the MIC (T > MIC). The 0.5 g QID regimen reduces fluctuations between peak and trough concentrations, thereby prolonging T > MIC and enabling continuous suppression of H. pylori growth while VPZ maintains gastric pH ≥ 6.0 for most of the day[33]. This favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile enhances AMO stability and antibacterial potency in the gastric environment[34]. Together, these mechanistic features explain why more frequent administration of a lower dose can achieve comparable eradication efficacy while improving tolerability[35].

With global antimicrobial resistance increasing, treatment strategies that deliver optimal pharmacodynamic exposure while minimizing antibiotic overuse are essential[36]. By demonstrating that a low-dose, high-frequency regimen is non-inferior to higher-dose regimens, this trial supports rational antibiotic stewardship without compromising efficacy. Furthermore, the simplified dual regimen, which relies on two well-tolerated agents, is suitable for potential integration into large-scale screening and eradication programs, particularly in high-prevalence regions with constrained healthcare resources, where simplified protocols can improve scalability, adherence, and long-term sustainability.

The main strengths of this study include its large sample size (n = 1717), multi-center design, and rigorous randomization process, which collectively enhance the reliability and generalizability of the findings. The pragmatic design reflects real-world clinical practice and increases the external validity of the conclusions. In addition, the non-inferiority framework with a prespecified margin (-10%) is statistically robust and aligns with accepted standards in antimicrobial clinical trials.

However, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, all study sites were located within Sichuan Province, which may limit generalizability to populations with different genetic backgrounds, antimicrobial resistance patterns, or healthcare infrastructures. Second, the open-label design, although practical, may have introduced performance or detection bias despite the use of objective outcomes such as 13C-UBT confirmation. Third, this study did not examine post-eradication changes in gastric microbiota composition or evaluate long-term reinfection or recurrence.

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has recently been proposed as a simple, cost-effective marker of systemic inflammation and immune activation in H. pylori infection. Elevated NLR has been correlated with more severe mucosal injury and delayed recovery following eradication therapy[37,38]. Although NLR was not assessed in this study, incorporating it into future trials could help identify patients with heightened inflammatory responses who may require closer monitoring or extended follow-up. Patients receiving VPZ-AMO therapy should also avoid alcohol and spicy foods to reduce gastric irritation, and probiotics may help mitigate antibiotic-related gastrointestinal symptoms and support adherence. For those with peptic ulcer disease, adjunctive mucosal-protective therapy may accelerate ulcer healing and improve overall treatment outcomes.

Future research should incorporate these biological and clinical parameters in combination with pharmacogenomic profiling (e.g., CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms) and therapeutic drug monitoring to optimize individualized dosing strategies based on host metabolism and acid-suppressive capacity[39].

The combination of VPZ with AMO is safe and highly effective for the eradication of H. pylori. All three dosing regimens achieved high eradication rates, with the 0.5 g QID strategy offering the most favorable balance of efficacy, symptom relief, and tolerability. These results support the 0.5 g QID regimen as a practical first-line strategy for H. pylori era

| 1. | Ahn HJ, Lee DS. Helicobacter pylori in gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7:455-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Ishikawa E, Nakamura M, Satou A, Shimada K, Nakamura S. Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma in the Gastrointestinal Tract in the Modern Era. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xie L, Liu GW, Liu YN, Li PY, Hu XN, He XY, Huan RB, Zhao TL, Guo HJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China from 2014-2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:4636-4656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Aldubaib M, Abalkhail A, Anagreyyah S, Anajirih N, Almuzaini AM, Rawway M, Alfadhel A, Draz A, Abu-Okail A. Helicobacter pylori Infection: Current Status and Future Prospects on Diagnostic, Therapeutic and Control Challenges. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12:191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miller AK, Williams SM. Helicobacter pylori infection causes both protective and deleterious effects in human health and disease. Genes Immun. 2021;22:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ansari S, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori Infection, Its Laboratory Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Resistance: a Perspective of Clinical Relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022;35:e0025821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spagnuolo R, Scarlata GGM, Paravati MR, Abenavoli L, Luzza F. Change in Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori Infection in the Treatment-Failure Era. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024;13:357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arslan N, Yılmaz Ö, Demiray-Gürbüz E. Importance of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for the management of eradication in Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2854-2869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Cardos IA, Zaha DC, Sindhu RK, Cavalu S. Revisiting Therapeutic Strategies for H. pylori Treatment in the Context of Antibiotic Resistance: Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies. Molecules. 2021;26:6078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 10. | Guo B, Cao NW, Zhou HY, Chu XJ, Li BZ. Efficacy and safety of bismuth-containing quadruple treatment and concomitant treatment for first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb Pathog. 2021;152:104661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tarhini M, Fayyad-Kazan M, Fayyad-Kazan H, Mokbel M, Nasreddine M, Badran B, Kchour G. First-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori in Lebanon: Comparison of bismuth-containing quadruple therapy versus 14-days sequential therapy. Microb Pathog. 2018;117:23-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sugano K. Vonoprazan fumarate, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: safety and clinical evidence to date. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756283X17745776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Isakov V, Goncharov A. Breaking barriers in the first-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: Chinese multicenter trial validates vonoprazan-based triple therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:112312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu Y, Xue J, Lin F, Liu D, Zhang W, Ru S, Jiang F. Global Primary Antibiotic Resistance Rate of Helicobacter pylori in Recent 10 years: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Helicobacter. 2024;29:e13103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer, Liu G, Xie J, Lu ZR, Cheng LY, Zeng Y, Zhou JB, Chen YJ, Wang NH, Du Y, Lyu N. [Fifth Chinese national consensus report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2017;56:532-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, Fischbach L, Gisbert JP, Hunt RH, Jones NL, Render C, Leontiadis GI, Moayyedi P, Marshall JK. The Toronto Consensus for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:51-69.e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 695] [Cited by in RCA: 672] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 2088] [Article Influence: 232.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kusano C, Ikehara H, Ichijima R, Ohyauchi M, Ito H, Kawamura M, Ogata Y, Ohtaka M, Nakahara M, Kawabe K. Seven-day vonoprazan and low-dose amoxicillin dual therapy as first-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: a multicentre randomised trial in Japan. Gut. 2020;69:1019-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hu Y, Xu X, Ouyang YB, He C, Li NS, Xie C, Peng C, Zhu ZH, Xie Y, Shu X, Lu NH, Zhu Y. Optimization of vonoprazan-amoxicillin dual therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pyloriinfection in China: A prospective, randomized clinical pilot study. Helicobacter. 2022;27:e12896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Peng X, Chen HW, Wan Y, Su PZ, Yu J, Liu JJ, Lu Y, Zhang M, Yao JY, Zhi M. Combination of vonoprazan and amoxicillin as the first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, parallel-controlled study. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23:4011-4019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou L, Lu H, Song Z, Lyu B, Chen Y, Wang J, Xia J, Zhao Z; on behalf of Helicobacter Pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. 2022 Chinese national clinical practice guideline on Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:2899-2910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Wilkins CA, Hamman H, Hamman JH, Steenekamp JH. Fixed-Dose Combination Formulations in Solid Oral Drug Therapy: Advantages, Limitations, and Design Features. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gotoda T, Kusano C, Suzuki S, Horii T, Ichijima R, Ikehara H. Clinical impact of vonoprazan-based dual therapy with amoxicillin for H. pylori infection in a treatment-naïve cohort of junior high school students in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:969-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Furuta T, Yamade M, Kagami T, Uotani T, Suzuki T, Higuchi T, Tani S, Hamaya Y, Iwaizumi M, Miyajima H, Umemura K, Osawa S, Sugimoto K. Dual Therapy with Vonoprazan and Amoxicillin Is as Effective as Triple Therapy with Vonoprazan, Amoxicillin and Clarithromycin for Eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Digestion. 2020;101:743-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Peng X, Yao JY, Ma YQ, Li GH, Chen HW, Wan Y, Liang DS, Zhang M, Zhi M. Efficacy and Safety of Vonoprazan-Amoxicillin Dual Regimen With Varying Dose and Duration for Helicobacter pylori Eradication: A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1210-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hu Y, Xu X, Liu XS, He C, Ouyang YB, Li NS, Xie C, Peng C, Zhu ZH, Xie Y, Shu X, Zhu Y, Graham DY, Lu NH. Fourteen-day vonoprazan and low- or high-dose amoxicillin dual therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection: A prospective, open-labeled, randomized non-inferiority clinical study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1049908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gao W, Wang Q, Zhang X, Wang L. Ten-day vonoprazan-based versus fourteen-day proton pump inhibitor-based therapy for first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication in China: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2024;38:3946320241286866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ju K, Kong Q, Zhang S, Zhu L, Li Y. Amoxicillin or tetracycline in bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Microbiol. 2025;16:1667516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cheung KS, Lyu T, Deng Z, Han S, Ni L, Wu J, Tan JT, Qin J, Ng HY, Leung WK, Seto WK. Vonoprazan Dual or Triple Therapy Versus Bismuth-Quadruple Therapy as First-Line Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Three-Arm, Randomized Clinical Trial. Helicobacter. 2024;29:e13133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Santagati G, Vezzosi L, Angelillo IF. Unintentional Injuries in Children Up to Six Years of Age and Related Parental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors in Italy. J Pediatr. 2016;177:267-272.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ahn BY, Cho SJ. [Potassium-competitive Acid Blockers: A New Therapeutic Strategy for Helicobacter pylori Eradication]. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2023;23:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yang E, Ji SC, Jang IJ, Lee S. Evaluation of CYP2C19-Mediated Pharmacokinetic Drug Interaction of Tegoprazan, Compared with Vonoprazan or Esomeprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023;62:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kotzerke M, Mitri F, Enk A, Toberer F, Haenssle H. A Case of Extensive Grover's Disease in a Patient with a History of Multiple Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:553-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Song Z, Zuo X, Zhang Z, Wang X, Lin Y, Li Y, Xu X, Huang Y, Wang Q, Shi Y, Zhou L. Ten-Day Versus 14-Day Vonoprazan and Amoxicillin Dual Therapy for the Firstline Eradication of Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial. Helicobacter. 2025;30:e70070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ju KP, Kong QZ, Li YY, Li YQ. Low-dose or high-dose amoxicillin in vonoprazan-based dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2024;29:e13054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Xie F, Yao S. Jatrorrhizine attenuates inflammatory response in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasomes and NF-κB signaling pathway. Arch Microbiol. 2025;207:177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Gao H, Bai H, Su Y, Gao Y, Fang H, Li D, Yu Y, Lu X, Xia D, Mao D, Luo Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation from Helicobacter pylori carriers following bismuth quadruple therapy exacerbates alcohol-related liver disease in mice via LPS-induced activation of hepatic TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling. J Transl Med. 2025;23:627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kumarasamy C, Sabarimurugan S, Madurantakam RM, Lakhotiya K, Samiappan S, Baxi S, Nachimuthu R, Gothandam KM, Jayaraj R. Prognostic significance of blood inflammatory biomarkers NLR, PLR, and LMR in cancer-A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e14834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kuo CH, Lu CY, Shih HY, Liu CJ, Wu MC, Hu HM, Hsu WH, Yu FJ, Wu DC, Kuo FC. CYP2C19 polymorphism influences Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16029-16036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/