Published online Dec 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112010

Revised: August 5, 2025

Accepted: October 31, 2025

Published online: December 14, 2025

Processing time: 147 Days and 5.4 Hours

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most prevalent skin cancer, characterized by indolent growth and low metastatic rates. When metastatic BCC (mBCC) does occur, it most commonly involves lymph nodes, lungs, and bones, with meta

A 52-year-old male with recurrent BCC and known mBCC to the bone presented with progressive dysphagia, cranial neuropathies and generalized weakness. He had been treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, with intermittent therapy modifications due to treatment related toxicities. His past history was notable for malignant perineural invasion, radiotherapy for osseous metastases, immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enteritis, and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Gastroscopy revealed subepithelial gastric lesions, and biopsies confirmed mBCC - a pre

Clinicians should consider atypical metastatic sites in advanced BCC. A multidisciplinary approach remains essen

Core Tip: Metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) rarely involves visceral organs, and gastric metastases have never been previously reported. We present the first documented case of metastatic BCC to the stomach in a patient with extensive bone metastases, highlighting the diagnostic challenges associated with this unusual presentation. This case underscores the importance of recognizing atypical metastatic patterns in advanced BCC, and demonstrates the critical role of a multidisciplinary approach in optimizing patient care and guiding end-of-life decision-making.

- Citation: Ahmadi S, Joarder I, Jowhari F. Beyond the skin - metastatic basal cell carcinoma in the stomach: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(46): 112010

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i46/112010.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112010

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common form of skin cancer, known for its slow growth and low metastatic potential[1,2]. While BCC is highly prevalent, early detection and appropriate treatment are typically associated with an excellent prognosis. Metastatic BCC (mBCC), however, is a rare occurrence, reported in less than 0.6% of cases and often linked to years of untreated or recurrent disease[1-3]. When metastasis does occur, it most frequently involves regional lymph nodes, followed by hematogenous spread to the lungs and bones, in decreasing order of frequency[2-5]. Rarely, metastases to other sites such as the salivary glands, liver, meninges, mediastinum, kidneys, pleura, skin, spleen, pancreas, peritoneum, diaphragm, pericardium, adrenals, and duodenum have been reported[2-6]. These locations are typically only affected in advanced disease, often concurrent with involvement of lymph nodes, lungs, or bones[2-6].

Gastric metastases, however, are exceptionally rare (0.2%-0.7%), and have previously been documented for the following primary tumour sites: Breast (27%), lung (23%), kidney (7.6%) and melanoma (7%)[7]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of mBCC in the stomach based on a comprehensive literature review. While the underlying mechanism of gastric metastases remains unknown, some proposed pathways include hematogenous dissemination, peritoneal dissemination, lymphatic infiltration and direct invasion[7]. These unusual presentations pose considerable diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to their atypical clinical manifestations and the limited data guiding management. This case report highlights a patient with mBCC presenting with metastases to both the bone and stomach, emphasizing the importance of recognizing atypical metastatic patterns, and adopting a multidisciplinary approach to managing advanced mBCC effectively.

A 52-year-old male presented with progressive dysphagia, generalized weakness, and worsening cranial neuropathies in October 2024.

The patient had a history of recurrent BCC and mBCC to the bone, first diagnosed in 2021. Initial treatment included a programmed death-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) (cemiplimab) and a receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand inhibitor (denosumab), achieving a partial response. However, he later developed immune ICI therapy-associated enteritis, necessitating prednisone treatment and a four-month interruption of cemiplimab in 2022. Attempts to re-initiate cemiplimab were unsuccessful, prompting a transition to a hedgehog pathway inhibitor (vismodegib) and an antifungal agent with off-label antitumor synergy (itraconazole). Despite this change, his disease progressed, leading to the re-introduction of cemiplimab in February 2024. A gut selective integrin receptor antagonist (vedolizumab) was concomitantly started as prophylaxis for immune mediated gastrointestinal toxicity. Over time he developed worsening neurological symptoms, attributed to ICI associated neuropathy, including cranial nerve IV and VII palsies. He also developed osteonecrosis of the jaw secondary to denosumab, which required further treatment modifications, including discontinuation of vedolizumab.

Over several months, he reported progressive dysphagia to both liquids and solids, describing the difficulty as primarily oropharyngeal, with impaired bolus transfer into his esophagus, and associated nasal regurgitation. He also experienced worsening postural lightheadedness, and intractable oral thrush. A video fluoroscopy swallowing study performed in conjunction with a speech language pathology assessment revealed a severely impaired and disorganized oral phase of swallowing with incomplete laryngeal clearance, and poor bolus coordination resulting in overt aspiration. As such he was considered to be at a significant risk for aspiration-related complications including pneumonia. Given his progressive symptoms and inability to maintain oral intake, he was admitted to hospital for further evaluation.

His medical history included multiple resected BCC lesions from both cheeks (2018, 2019, 2020, 2022), some of which demonstrated perineural invasion. He received radiotherapy for bone metastases, and had a remote history of squamous cell carcinoma excised from his posterior neck. His medical history also included a previous cerebrospinal fluid leak treated with an epidural blood patch. He was also diagnosed with tumor-induced osteomalacia, treated with burosumab.

There was no significant family history of malignancies or known genetic predispositions. He was a lifelong non-smoker and had no history of significant environmental exposures.

On examination, the patient was alert and in no acute distress. His vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.8 °C; blood pressure, 123/89 mmHg; heart rate, 100 beats/minute; and oxygen saturation 94% on room air. His left eye was taped shut due to difficulties with eyelid closure. There was no scleral icterus in the right eye and no frank jaundice noted. There was obvious facial asymmetry seen from his cranial nerve VII palsy. Guttural and lingual sounds were normal. Tongue movement was normal. There was 4/4 motor strength in all 4 extremities with spontaneous movements. Abdomen was soft and non-tender. There was a scar seen on his right cheek from previous BCC excision.

A complete blood count revealed the following: Hemoglobin 101 g/L, white blood cell count 9 × 109/L, and platelet count 70 × 109. Liver function tests demonstrated a normal total bilirubin level of 17 μmol/L, but progressive and marked transaminitis with alkaline phosphatase 697 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase > 1200 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 232 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase 97 U/L.

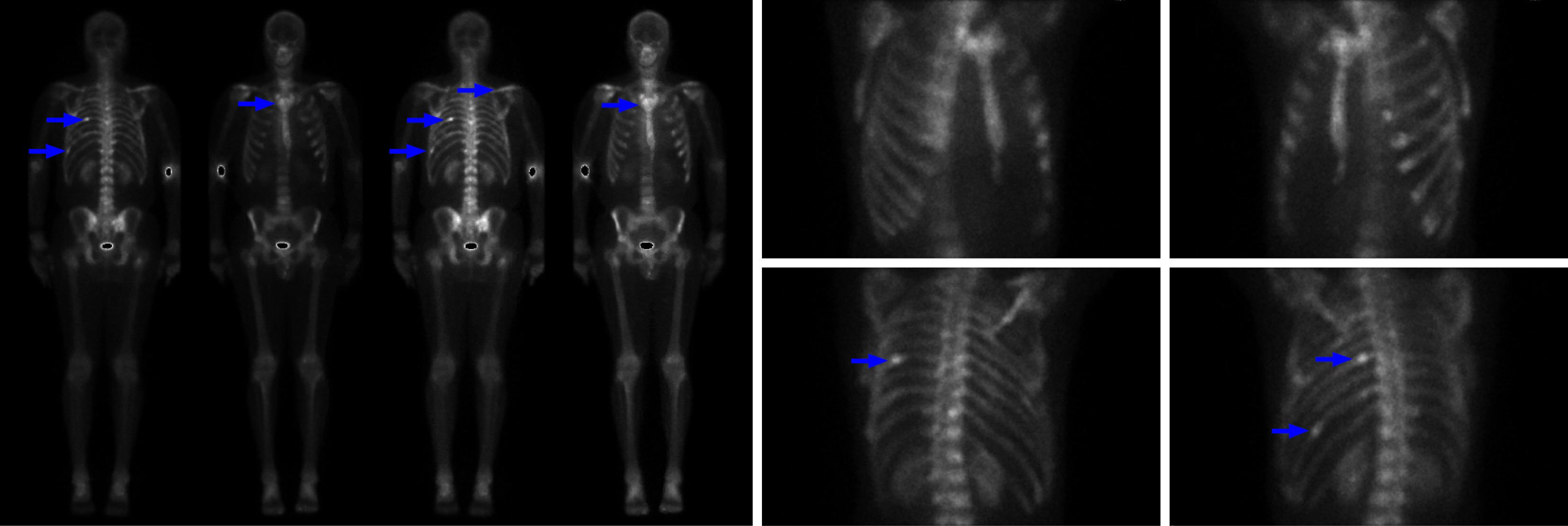

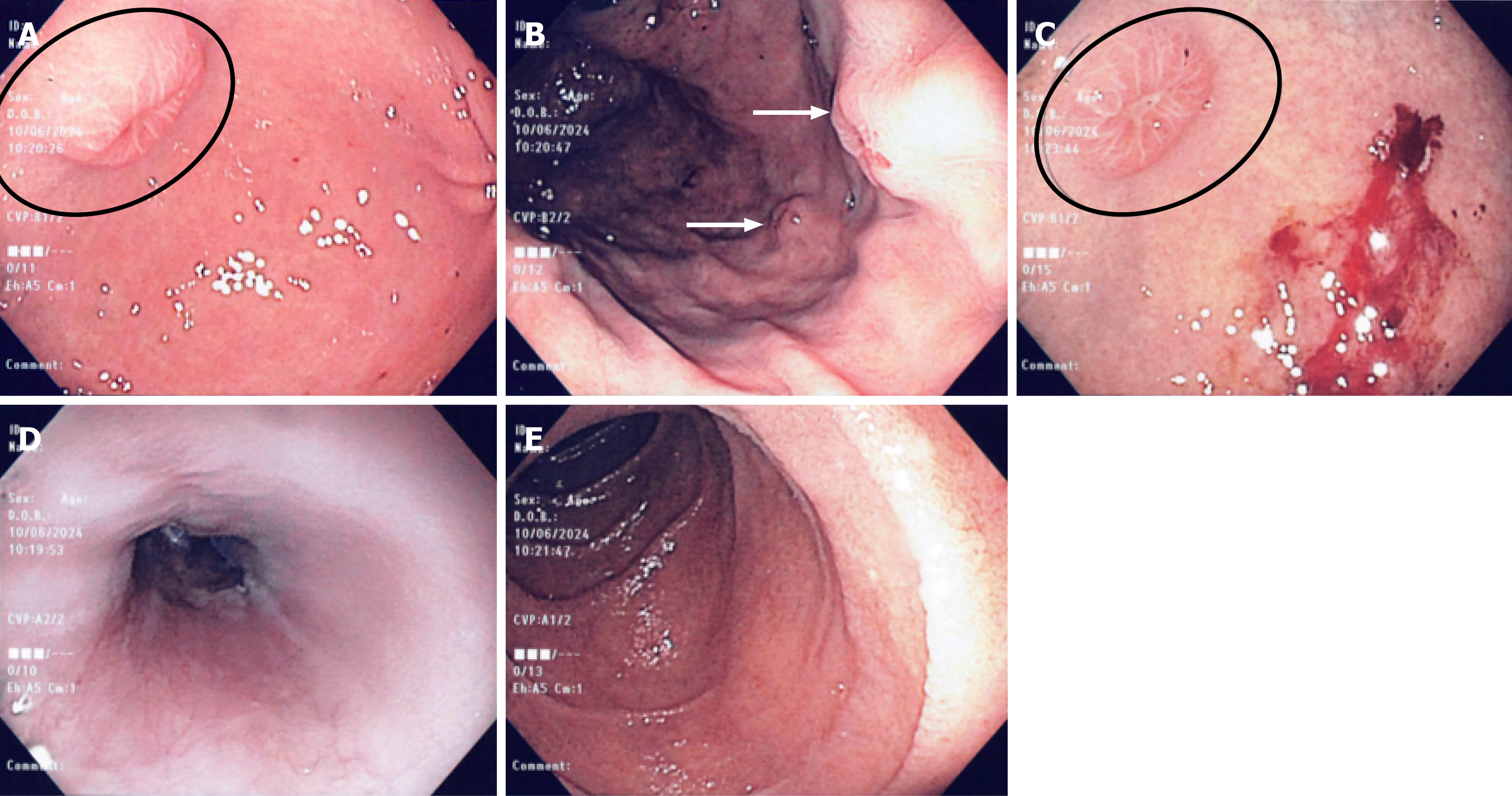

Prior to admission, whole-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography, confirmed extensive skeletal involvement of mBCC (Figure 1). A gastroscopy revealed multiple well circumscribed, subepithelial nodules, measuring between 5-10 mm in size, and located predominantly in the gastric body and fundus, but also in the antrum. The lesions were firm and had an umbilicated center with a targetoid appearance. The overlying mucosa was intact and not actively bleeding, but some friability was noted. The endoscopic appearance and number raised suspicion for metastatic disease, and targeted mucosal biopsies taken with standard biopsy forceps, later confirmed these to be mBCC on histopathology (Figure 2A-C). There was no active oropharyngeal or esophageal candidiasis observed, and both the esophagus and duodenum appeared normal (Figure 2D and E). Triphasic computed tomography of the abdomen showed intrahepatic biliary duct dilation, but no mass was seen. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was unremarkable.

Histologic evaluation of the targeted gastric biopsies showed nests of basaloid cells infiltrating the mucosa. Immunohistochemical staining showed strong expression of MOC31, but epithelial membrane antigen, chromogranin and synaptophysin were negative, ruling out neuroendocrine differentiation. The findings were consistent with mBCC involving the gastric mucosa. There was no evidence of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia or Helicobacter pylori. The patient was therefore diagnosed with metastatic mBCC involving the stomach - a previously undocumented site of metastatic spread.

Due to significant weakness, difficulty managing oral intake, and the very high aspiration risk related to both advanced disease and neurological symptoms, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube as opposed to a nasogastric tube was inserted. The patient and his spouse were successfully trained in its use to independently manage nutrition and medication administration. The patient also experienced significant ocular irritation and inflammation of the left eye related to his left sided Bell’s palsy, and a tarsoplasty was performed to protect his left eye. There were no suitable systemic treatment options available and although treatment with systemic radioisotope therapy was considered, it was ultimately deemed inappropriate given the patient’s clinical status. Gastric-specific treatments such as endoscopic resection or radiation were also not considered given the diffuse metastases and the risks associated with treatment. During his hospitalization, he was evaluated by neurology, gastroenterology, oncology, and the palliative care teams. Following comprehensive multidisciplinary discussions and consideration of his advanced disease and deteriorating quality of life, a decision was made to transition to hospice care and discharge the patient on a symptom based palliative management plan.

Given the advanced nature of his disease, limited prognosis, and ongoing challenges with quality of life, the patient and his family opted for hospice care following discharge. While there is limited research on prognostic data for mBCC to the stomach, the median overall survival of patients with metastatic gastric cancer has been reported to be 3 months (ranging from 1-11 months in a series of 37 cases)[7]. Subsequent care focused on symptom management, including pain control and palliative interventions, aimed at optimizing comfort during the patient’s remaining time.

Metastatic mBCC is an exceptionally rare and aggressive manifestation of a typically indolent skin cancer. Although BCC constitutes the vast majority of skin cancer cases, its metastatic rate remains under 0.6%[1-3]. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of mBCC with gastric involvement, expanding the known spectrum of metastatic patterns and offering critical insights for clinicians managing advanced disease. The rarity of gastric metastases in mBCC is likely multifactorial. Factors influencing metastatic potential include tumor size, depth of invasion, histologic subtype, duration of untreated disease, local recurrence of primary tumour, immunosuppression, perineural invasion, history of radiation therapy, and high mitotic activity[8-10]. Aggressive subtypes, such as infiltrating BCC, or tumours with perineural invasion, as seen in our patient, carry a higher risk of dissemination[8-10]. Hematogenous spread, enabled by vascular invasion, likely accounts for the gastric and osseous involvement in this case. Additionally, long-term immunosuppression due to ICI-related toxicities may have altered the disease course and contributed to its atypical metastatic behavior. These immunosuppressive microenvironments may have promoted tumour progression and favoured the immune escape of cancers[11].

The diagnosis of mBCC in the stomach is inherently challenging due to its rarity and nonspecific clinical presentation. In our patient, dysphagia, that was an unrelated symptom prompted endoscopic evaluation and ultimately led to the diagnosis. This underscores the need for a high index of suspicion for atypical metastatic sites in patients with advanced BCC, particularly when new or atypical gastrointestinal symptoms or symptoms that deviate from the expected disease course arise. The endoscopists (whether gastroenterologists or surgeons) should follow standard practice guidelines when approaching subepithelial gastric lesions. The first step is careful inspection of the lesion, followed by targeted biopsies using standard or jumbo biopsy forceps with multiple passes to improve diagnostic yield. If the diagnosis is still in question, then a referral to a tertiary centre for consideration of advanced techniques such as endoscopic ultrasound guided biopsy could be considered. Recognizing the diagnostic value of subtle cues, such as central umbilication, can have prognostic implications for cases like these.

The management of mBCC presents unique challenges, particularly in patients with advanced disease requiring systemic therapy. ICIs like cemiplimab have revolutionized the therapeutic landscape for advanced BCC, offering durable responses in many patients with advanced or inoperable disease[10,12,13]. However, immune-related adverse events, as seen in our patient, often necessitate treatment modifications or discontinuation, complicating disease management. While advances in chemotherapeutic medications have improved, the prognosis of mBCC still remains poor, with median survival ranging from 8 months to 7 years depending on disease burden and therapeutic response[2,14]. For our patient, concurrent gastric and osseous metastases combined with neurological complications indicated refractory disease, highlighting the importance of early detection, and the judicious use of systemic therapies to delay progression and preserve quality of life. Further limitations in this case included the absence of molecular profiling for hedgehog pathway mutations in particular, which could have informed resistance to vismodegib and guided alternative therapies.

This case also highlights the critical role of multidisciplinary care in managing advanced mBCC. Gastroenterology’s involvement was pivotal in identifying and addressing gastric metastases, while oncology guided systemic therapy adjustments. Palliative care played a key role in addressing quality-of-life concerns and facilitating the transition to hospice care. These coordinated efforts exemplify the value of a team-based approach in optimizing outcomes for patients with complex, advanced disease.

Our case illustrates the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in diagnosing and managing advanced mBCC, particularly when faced with rare metastatic sites such as the stomach. It highlights the need for further research into the mechanisms driving atypical metastases, and strategies to optimize therapeutic outcomes while minimizing toxicity. Clinicians managing mBCC should remain vigilant for rare metastatic presentations, and maintain a broad differential diagnosis when patients exhibit atypical symptoms. In patients with mBCC and new gastrointestinal symptoms, early endoscopy with targeted biopsies should be prioritized to detect rare metastatic sites like the stomach. Importantly, mBCC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of subepithelial gastric lesions, especially those with an umbilicated center as this may represent a distinctive endoscopic clue to an otherwise rare diagnosis.

| 1. | Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal Cell Carcinoma Review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McCusker M, Basset-Seguin N, Dummer R, Lewis K, Schadendorf D, Sekulic A, Hou J, Wang L, Yue H, Hauschild A. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: prognosis dependent on anatomic site and spread of disease. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:774-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Millán-Cayetano JF, Blázquez-Sánchez N, Fernández-Canedo I, Repiso-Jiménez JB, Fúnez-Liébana R, Bautista MD, de Troya-Martin M. Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:61-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mikhail GR, Nims LP, Kelly AP Jr, Ditmars DM Jr, Eyler WR. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: review, pathogenesis, and report of two cases. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1261-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Robinson JK, Dahiya M. Basal cell carcinoma with pulmonary and lymph node metastasis causing death. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:643-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gellatly M, Cruzval-O'Reilly E, Mervak JE, Mervak BM. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma with atypical pattern of spread. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:2641-2644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Weigt J, Malfertheiner P. Metastatic Disease in the Stomach. Gastrointest Tumors. 2015;2:61-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Paul S, Knight A. The Importance of Basal Cell Carcinoma Risk Stratification and Potential Future Pathways. JMIR Dermatol. 2023;6:e50309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baker LX, Grilletta E, Zwerner JP, Boyd AS, Wheless L. Clinical and Histopathologic Characteristics of Metastatic and Locally Advanced Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43:e169-e174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Casey MC, Pollock R, Enright RH, O'Neill JP, Shine N, Sullivan P, Martin FT, O'Sullivan B. Metastatic and locally aggressive BCC: Current treatment options. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tie Y, Tang F, Wei YQ, Wei XW. Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 94.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Villani A, Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, Scalvenzi M. New Emerging Treatment Options for Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Adv Ther. 2022;39:1164-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lewis KD, Peris K, Sekulic A, Stratigos AJ, Dunn L, Eroglu Z, Chang ALS, Migden MR, Yoo SY, Mohan K, Coates E, Okoye E, Bowler T, Baurain JF, Bechter O, Hauschild A, Butler MO, Hernandez-Aya L, Licitra L, Neves RI, Ruiz ES, Seebach F, Lowy I, Goncalves P, Fury MG. Final analysis of phase II results with cemiplimab in metastatic basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog pathway inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Danial C, Lingala B, Balise R, Oro AE, Reddy S, Colevas A, Chang AL. Markedly improved overall survival in 10 consecutive patients with metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:673-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |