Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112318

Revised: August 25, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: December 7, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 10.5 Hours

People with compensated advanced chronic liver disease (cACLD) remain at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) even after hepatitis C virus (HCV) sus

To evaluate transient elastography and fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index as prognostic markers for HCC after HCV-SVR.

This retrospective cohort study analyzed data from people with cALCD and HCV-SVR. cALCD was defined as baseline liver stiffness measurement (LSM) ≥ 10 kPa. The primary outcome was the occurrence of HCC. Data collected at base

Total of 425 patients (65.2% female; mean age = 62 ± 10 years) were included. The median pre-treatment and 1-year-EOT LSM were respectively 15.0 kPa (interquartile range: 11.8-23.2) and 12 kPa (interquartile range: 7.9-19.9) (P < 0.001), with a 27% (interquartile range: 2.7%-43%) reduction after SVR. The median pre-treatment FIB-4 index was 2.94 (interquartile range: 1.89-4.85) and 1-year-EOT FIB-4 1.99 (interquartile range: 1.29-3.13) (P < 0.001). Neither LSM nor FIB-4 deltas were associated with HCC. A total of 26 participants (6%) developed HCC during a follow-up of 48 ± 23 months with an incidence of 15.3/1000 person-years. Age [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.06, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01-1.11; P = 0.02], baseline (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02-1.07) and 1-year-EOT LSM ≥ 20 kPa (HR = 4.49, 95%CI: 2.19-9.19; P < 0.001) and baseline (HR = 7.79, 95%CI: 2.31-26.32; P < 0.001) and 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index score ≥ 3.25 (HR = 3.14, 95%CI: 1.65-6.00; P < 0.001) were associated with incident HCC.

In cACLD-HCV SVR patients, pre-treatment or 1-year-EOT LSM ≥ 20 kPa and FIB-4 ≥ 3.25 but not their delta was associated with HCC. A single measure of LSM ≥ 20 kPa or FIB-4 ≥ 3.25, either pre-treatment or 1-year-EOT, would be necessary to predict the incidence of HCC in people with HCV-SVR.

Core Tip: This retrospective longitudinal study was conducted in two tertiary centers to evaluate noninvasive tests as predictive factors for developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The cohort included people with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and compensated advanced chronic liver disease, defined as pre-treatment liver stiffness measurement (LSM) ≥ 10 kPa, who achieved sustained virological response after direct-acting antivirals therapy. At pre-treatment and 1-year end of treatment, fibrosis-4 index score ≥ 3.25 and LSM ≥ 20 kPa were independently associated with the incidence of HCC.

- Citation: da Silva PGF, Barrocas JBP, Perazzo H, Villela-Nogueira L, Peixoto HR, Pereira GHS, Braga LNP, Chinzon M, de Silva JRL, Fernandes FF, Villela-Nogueira CA. Transient elastography and fibrosis-4 index as predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus patients with sustained virological response. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(45): 112318

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i45/112318.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112318

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignancy in the world and the leading primary liver cancer[1-4]. Sustained virological response (SVR) to hepatitis C virus (HCV) obtained with direct-acting antivirals (DAA) reduces the risk of HCC by 43% to 70% when compared to patients without SVR[5-9]. Although there is a decrease in the HCC incidence after SVR, people with advanced fibrosis or liver cirrhosis before SVR are still at risk of HCC for as long as 10 years after SVR[9].

DAAs have improved survival of patients with HCV infection, and it is estimated that the number of patients under HCC surveillance will increase six-fold from 2012 to 2030[10]. For now, clinical guidelines recommend life-long ul

Recently, diagnosis of compensated advanced chronic liver disease (cACLD) has been based on noninvasive tests (NITs), such as liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by transient elastography (TE) or serological markers [i.e., fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index][12]. The current guidelines recommend the use of NITs for surveillance of people with clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH). However, there is still a gap in knowledge on using NITs to predict the HCC incidence after HCV-SVR. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic values of LSM and FIB-4 index before and after 1 year of HCV treatment to predict the incidence of HCC in people with HCV-SVR and cACLD.

This retrospective longitudinal study evaluated LSM and FIB-4 index values of individuals with cACLD and HCV-SVR as predictors of HCC. It was conducted in two tertiary centers, Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Bonsucesso Federal Hospital in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil. All consecutive adult patients with chronic hepatitis C, advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, treated with DAA between January 2016 and March 2021 were eligible. Patients with a pre-treatment LSM suggesting cACLD, defined by a LSM ≥ 10 kPa, who achieved SVR were included. The value ≥ 10 kPa was chosen since BAVENO VII considered LSM values between 10 kPa and 15 kPa suggest cACLD. Exclusion criteria were: Human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis B coinfection; HCC diagnosis within 180 days after end of treatment (EOT); chronic kidney failure, right-sided heart failure, and presence of other concomitant chronic liver diseases. This study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the Ethical Committee of the UFRJ (No. CAAE 1.654.467).

The investigators collected the information manually from patients’ records by following a code book designed by the author. The data before HCV treatment (pre-treatment) was: Demographic characteristics (age, sex, skin color, body mass index), presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), presence of CSPH (defined as esophageal varices, ascites, splenomegaly and collateral circulation), and previous liver-related decompensations (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or gastro-esophageal variceal bleeding). Additionally, pre-treatment and one year after EOT (1-year-EOT) laboratory parameters, including liver enzymes, albumin, bilirubin, international normalized ratio, platelet count, and alpha fetoprotein, were also collected. The FIB-4 index score was calculated by the formula: [Age × aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/(platelet count × √alanine aminotransferase)][13]. We collected data from TE examinations (Fibroscan Touch 502, Echosens, France) obtained closest to the start date and one year after HCV treatment. Experienced operators performed TE exams in individuals fasted for at least 3 hours. The delta of TE between pre and 1-year-EOT was also assessed. The pre-treatment, 1-year-EOT, and delta FIB-4 index were also calculated. Cirrhosis was defined as LSM ≥ 12.5 kPa, imaging signs of chronic liver disease by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or liver histology, if available. SVR was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks after the EOT. Trained investigators also reviewed all medical records from included patients to identify the prospective incidence of HCC defined by magnetic resonance imaging, triphasic computed tomography with or without alpha-fetoprotein above 400 UI. Participants were followed up through medical care, laboratory tests, and imaging every 6 months until the development of HCC, liver transplantation, or death. Participants without HCC during follow-up were censored at the last visit up to 30 April 2024.

Continuous variables were expressed by mean with the respective standard deviation or as the median with interquartile range, and categorical variables as absolute (n) and relative frequency. The Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test was applied for the comparative analysis between parametric and non-parametric continuous variables. A χ2 test was also applied to compare categorical variables and HCC development. Parametric continuous variables were analyzed at the baseline and 1-year-EOT using the paired T-test, and those non-parametric variables using the Wilcoxon test. Area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the best performance of each test (FIB-4 pre- and post-treatment and LSM pre- and post-treatment EOT) using HCC development as the outcome. The AUROCs were compared using the DeLong test. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted, and the log-rank test was calculated. A Cox proportional-hazard model was built to identify the variables independently associated with HCC [hazard ratio (HR)]. All models were adjusted for age and sex. The significance level was established as 5%. Data was guarded and analyzed by the SPSS statistical package database version 27 (IBM Inc., NY, United States). The MedCalc statistical software (MedCalc Software Ltd, Belgium) was used to compare the AUROCs regarding FIB-4 pre- and post-treatment and LSM pre- and post-treatment.

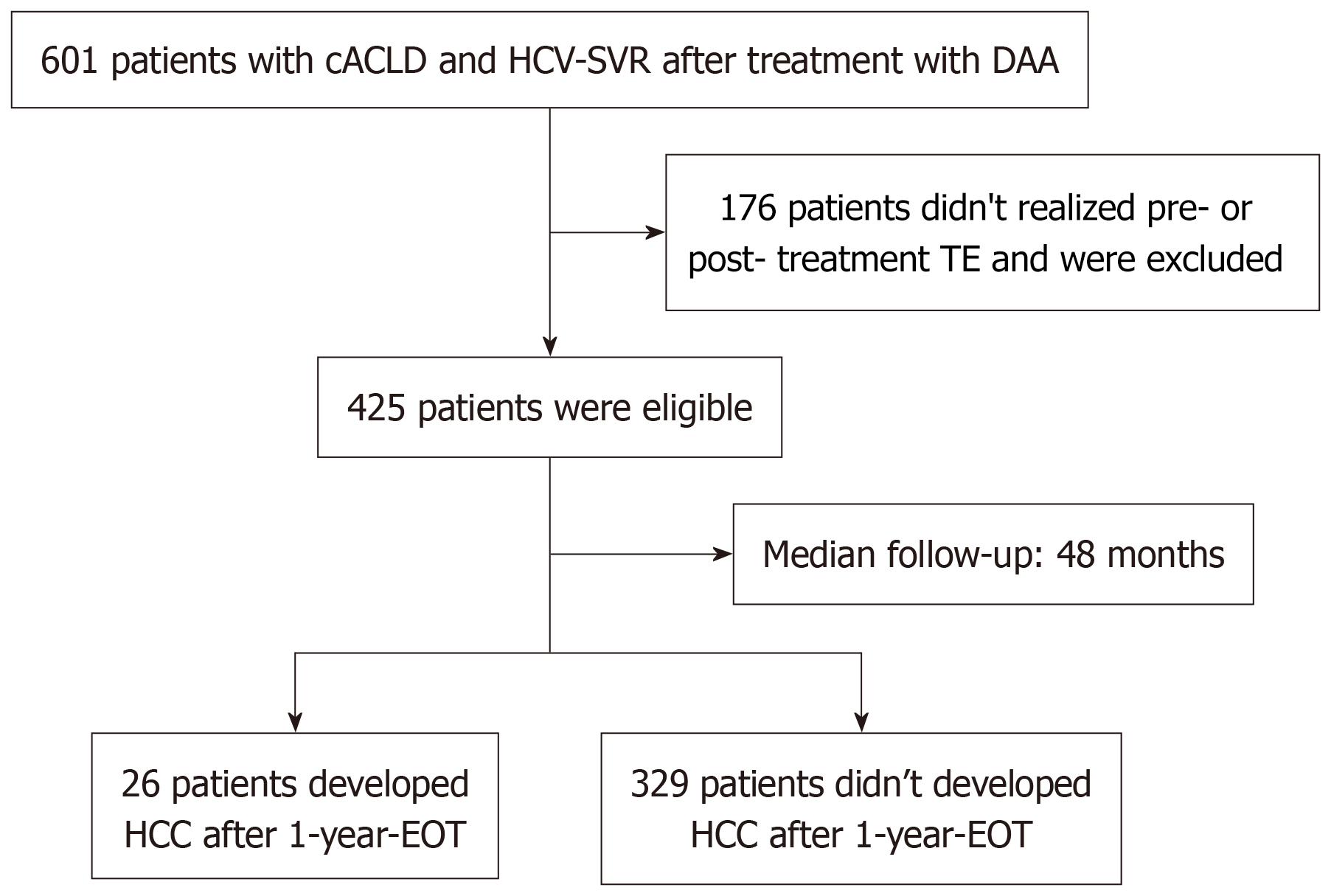

Overall, 601 people with cACLD and HCV-SVR after treatment with DAA were eligible. One hundred seventy-six (29%) were excluded due to missing data on LSM pre-treatment or 1-year-EOT (Figure 1). Hence, 425 participants [65.2% female, median age 62 years (interquartile range: 56-67), 56.5% self-declared as non-white skin color, 63.3% with DM, and 20% with CSPH] were included in the study. A total of 15 participants (3.5%) had already experienced any liver-related decompensation before treatment [0.9% (n = 4) variceal bleeding; 2.6% (n = 11) ascites; 0.9% (n = 4) hepatic encephalopathy].

The median interquartile range pre-treatment LSM was 15.0 kPa (interquartile range: 11.8-23.2), and a pre-treatment LSM ≥ 20 kPa was observed in 151 (35.5%) of participants. The median interquartile range pre-treatment FIB-4 index was 2.94 (interquartile range: 1.89-4.85), and 181 (42.7%) participants had a pre-treatment FIB-4 ≥ 3.25. During a median follow-up of 48 months (± 23), 6% (n = 26) of patients developed HCC, corresponding to an incidence rate of 15.3 per 1000 person-years [95% confidence interval (CI): 9.4-21.2]. Nine (35%) developed HCC up to 24 months after EOT. Among those with incident HCC, 3 (11.5%) patients were transplanted, and 17 (65%) died. Most of the HCC patients had cirrhosis before treatment (n = 23, 88.5%) with a median LSM of 26.3 kPa (interquartile range: 20-38.5) and a median FIB-4 index of 5.9 (interquartile range: 4.4-8.8). Only three patients (11.5%) with HCC presented advanced fibrosis (F3), with a median LSM of 10.9 kPa (interquartile range: 10.3-10.9) and a median FIB-4 index of 4.37 (interquartile range: 1.13-4.37). Table 1 shows the baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the included HCV-SVR patients.

| Variables | |

| Age, years | 61 ± 10.2 |

| Female sex | 277 (65.2) |

| White non-Hispanic | 240 (56.5) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 156 (36.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.98 ± 5.24 |

| AST, U/L, median IQR | 70 (45-108) |

| ALT, U/L, median IQR | 86 (54-135) |

| Albumin, g/dL, median IQR | 3.8 (3.5-4.1) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL, median IQR | 0.7 (0.5-1) |

| INR, median IQR | 1.1 (1-1.2) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/mL, median IQR | 8.2 (4.7-15) |

| Pre-T F3 | 137 (32.2) |

| Pre-T F4 | 265 (67.8) |

| CSPH | 85 (20) |

| Previous decompensation | 15 (3.5) |

| LSM, kPa, median IQR | 15 (11.8-23.2) |

| FIB-4 index, median IQR | 2.94 (1.89-4.85) |

| Platelets, × 109/L | 165 ± 71 |

| Time of follow-up, months | 48 ± 23 |

| HCC | 26 (6) |

| Time until HCC since EOT, months | |

| ≥ 12 | 9 (34.6) |

| ≥ 24 | 17 (65.4) |

Overall, in 1-year-EOT, the median LSM was 12 kPa (interquartile range: 7.9-19.9) with a 27% reduction compared to pre-treatment LSM values. At univariate analysis, a reduction of > 20% and > 25% occurred in 61% (n = 256) and 55% (n = 231) of participants, respectively, and was not related to HCC development (P = 0.07 and P = 0.25, respectively). Nevertheless, those patients who achieved 1-year-EOT LSM lower than 10 kPa had a significantly lower occurrence of HCC (P = 0.029). Accordingly, the median 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index was 1.78 (interquartile range: 1.24-2.25) with a 60% reduction compared to the pre-treatment. The FIB-4 index delta was unrelated to the HCC development (P = 0.85). Table 2 shows LSM and FIB-4 index values in patients who developed HCC compared to those who did not.

| Variables | People without incident HCC (n = 399) | People with incident HCC (n = 26) | P value |

| Age, years | 60.8 ± 10.3 | 64.8 ± 6.0 | 0.004 |

| Female sex | 261 (65.4) | 16 (61.5) | 0.68 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.0 ± 5.3 | 26.9 ± 3.2 | 0.36 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 144 (36) | 12 (46) | 0.30 |

| Pre-T platelets, 109/L | 168 ± 71 | 113 ± 44 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-T AST, U/L, median IQR | 70 (45-110) | 101 (62-123) | 0.04 |

| Pre-T ALT, U/L, median IQR | 88 (55-139) | 102 (52-126) | 0.85 |

| Pre-T albumin, g/dL, median IQR | 3.8 (3.5-4.1) | 3.4 (3.1-3.9) | 0.007 |

| Pre-T LSM, kPa, median IQR | 14.6 (11.8-22.2) | 24.5 (14.2-34.6) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-T FIB-4, median IQR | 2.83 (1.84-4.6) | 5.86 (4.37-9.15) | < 0.001 |

| 1yr-EOT-platelets, 109/L | 178 ± 69 | 138 ± 37 | 0.005 |

| 1-year-EOT AST, median IQR | 24 (20-31) | 29 (31-39) | 0.03 |

| 1-year-EOT ALT, median IQR | 25 (19-33) | 25 (19-32) | 0.78 |

| 1-year-EOT albumin, median IQR | 4.1 (3.9-4.4) | 3.8 (3.7-4.3) | 0.02 |

| 1-year-EOT LSM, kPa, median IQR | 11.9 (7.8-18.8) | 20.1 (13.9-35.5) | < 0.001 |

| 1-year-EOT FIB-4, median IQR | 1.75 (1.22-2.63) | 3.02 (2.3-5.3) | < 0.001 |

The pre-treatment and 1-year-EOT LSM AUROCs regarding the development of HCC were 0.70 (95%CI: 0.57-0.80) and 0.70 (95%CI: 0.58-0.81), respectively (P = 0.97), and the pre-treatment and 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index AUROCs were 0.76 (95%CI: 0.74-0.82) and 0.78 (95%CI: 0.71-0.85), P = 0.47.

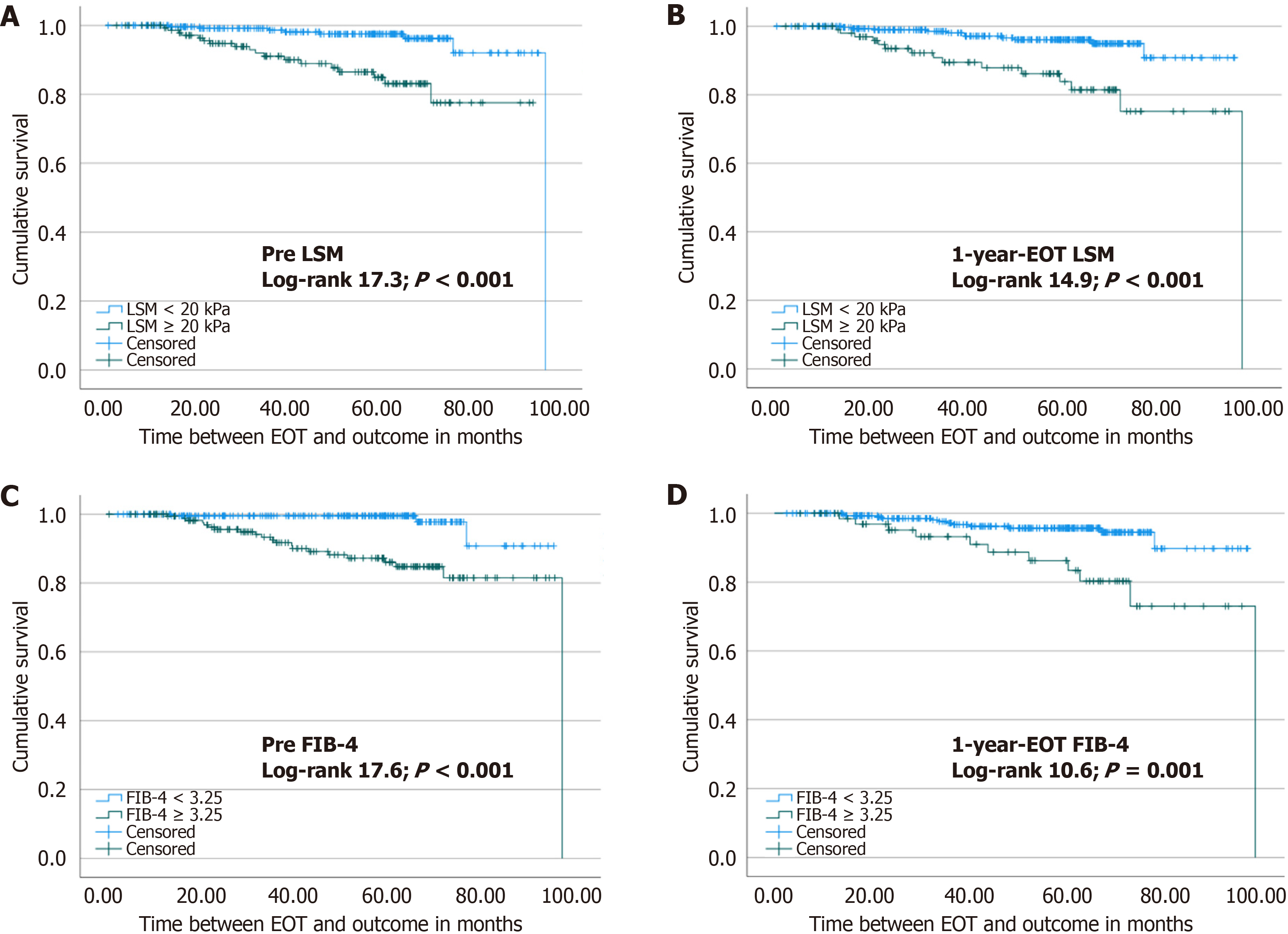

At the Kaplan Meier analysis (Figure 2), patients with 1-year-EOT LSM ≥ 20 kPa had a higher risk of HCC (log-rank 14.9; P < 0.001). Likewise, FIB-4 index ≥ 3.25 had a higher risk of HCC development (log-rank 10.6; P = 0.001). Fur

Due to collinearity between LSM and FIB-4, pre-treatment and 1-year-EOT, separate models regarding Cox regression analysis were built. Table 3 depicts all pre-treatment LSM and FIB-4 index results as continuous or categorical variables. In its first two models (models 3a and 3b), the variables independently associated with HCC were age and LSM, either as a continuous variable or as a categorical one. Regarding the FIB-4 index as a continuous or categorical variable (cut-off 3.25) (models 3c and 3d), both were associated with HCC occurrence.

| Covariates | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Model 3a: LSM, kPa | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.42 (0.63-3.2) | 0.39 |

| Pre-treatment LSM, kPa | 1.05 (1.02-1.07) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-treatment age, years | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) | 0.10 |

| Model 3b: LSM ≥ 20 kPa | ||

| Sex (male) | 0.72 (0.32-1.63) | 0.43 |

| Pre-treatment LSM ≥ 20 kPa | 0.2 (0.08-0.47) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-treatment age, years | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) | 0.02 |

| Model 3c: FIB-4 index | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.41 (0.57-3.49) | 0.45 |

| Pre-treatment age, years | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) | 0.22 |

| Pre-treatment FIB-4 index | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3d: FIB-4 index ≥ 3.25 | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.81 (0.49-2.82) | 0.71 |

| Pre-treatment age, years | 1.06 (1-1.11) | 0.034 |

| Pre-treatment FIB-4 index ≥ 3.25 | 7.79 (2.31-26.32) | < 0.001 |

Table 4 presents 1-year-EOT models regarding pre-treatment LSM as a continuous or categorical variable (Cut-off of 20 kPa), (models 4a and 4b), as well as 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index, also as a continuous or categorical variable (cut-off 3.25) (models 4c and 4d). One year-EOT-LSM either as a continuous or categorical variable (models 4a and 4b) and continuous or categorical FIB-4 index (models 4c and 4d) together with age were associated with HCC outcome. Furthermore, LSM ≥ 15 kPa was also performed in Cox regression analysis and showed to be significant only after 1-year-EOT (HR = 3.98, 95%CI: 1.64-9.62, P = 0.002).

| Covariates | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Model 4a: LSM, kPa | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.17 (0.57-2.42) | 0.66 |

| 1-year-EOT LSM, kPa | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Age at 1-year-EOT, years | 1.04 (0.99-1.08) | 0.05 |

| Model 4b: LSM ≥ 20 kPa | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.45 (0.71-2.95) | 0.30 |

| 1-year-EOT LSM ≥ 20 kPa | 4.49 (2.19-9.19) | < 0.001 |

| Age at 1-year-EOT, years | 1.04 (1.003-1.085) | 0.03 |

| Model 4c: FIB-4 index | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.10 (0.60-2.01) | 0.30 |

| Age at 1-year-EOT, years | 1.040 (1.002-1.080) | 0.04 |

| 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index | 1.16 (1.06-1.28) | < 0.001 |

| Model 4d: FIB-4 index ≥ 3.25 | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.15 (0.63-2.09) | 0.63 |

| Age at 1-year-EOT, years | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.07 |

| 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index ≥ 3.25 | 3.14 (1.65-6.00) | < 0.001 |

The covariates included in the pre-treatment and post-treatment models (Tables 3 and 4) were DM, pre-treatment platelet count, pre-treatment AST, and pre-treatment albumin for the models that included LSM and for the models that included FIB-4 index, DM, and 1-year-EOT albumin since AST and platelets compose the FIB-4 index formula. All models were adjusted for sex and age.

The present study highlights the prognostic value of noninvasive methods to predict the incidence of HCC in a cohort of people with cACLD before HCV treatment (defined as LSM ≥ 10 kPa) who obtained SVR after DAA therapy. Our most relevant findings were the good performance of the LSM and the FIB-4 index as predictors of HCC risk in a 48-month follow-up. Besides, we demonstrated that variation of liver stiffness pre- and post-treatment did not perform well as an NIT for HCC risk stratification.

In our study, age was a predictor of HCC. The same was observed in a Brazilian cohort of patients with all degrees of fibrosis[14]. On the other hand, Alonso López et al[15] did not identify an association between age and HCC in their cohort of 1046 patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Age is a consolidated risk factor for HCC and is included in risk scores for HCC development, such as age-male-albumin-bilirubin-platelets and HCC risk[2,16,17]. So far, there is no established cut-off for age as an HCC risk[17,18], maybe due to demographic, genetic, and socioeconomic differences between the cohorts.

Many studies evaluated the variation between pre- and post-treatment LSM in SVR HCV patients[19-21]. Semmler et al[21] evaluated the Baveno VII criteria in a cohort of 2335 patients with pre-treatment LSM > 10 kPa and concluded that LSM dynamics did not provide significant prognostic information in patients with follow-up LSM between 10 kPa and 19.9 kPa.

A study from Ravaioli et al[20] suggested that a 30% reduction in LSM was a protective factor for HCC development. However, this study included only 139 patients with a shorter follow-up of 15 months. Besides, the post-end-of-treatment LSM was performed at different times. Another Brazilian cohort of 456 patients with cACLD showed that the regression of at least 20% of LSM after SVR was associated with a significant decrease in the incidence of liver-related complications, including HCC[22].

In our cohort, either a 20% or a 25% variation in LSM after 1-year-EOT was not identified as a significant protective factor for HCC incidence. It is well established that a reduction in liver stiffness after SVR partly results from inflammation resolution but not necessarily due to fibrosis improvement[23-26]. Hence, it is reasonable not to expect an association between pre- and post-treatment LSM variation and HCC occurrence, as shown in the present study. Studies that identified a protective association between pre- and post-treatment LSM delta and the development of HCC had fewer patients; included patients with all stages of liver stiffness, and/or did not have HCC as the primary outcome[20,22].

Several studies demonstrated that pre-treatment LSM was associated with pos SVR HCC occurrence, with predicting values varying from 15 kPa to 21 kPa[14,19,20]. These studies are heterogeneous regarding LSM pre-treatment inclusion criteria and elastography intervals[14,19,20]. In our study, pre-treatment continuous and categorical LSM were associated with HCC. However, the LSM with a 20 kPa cut-off presented a higher predictive value when compared to LSM as a continuous variable.

The post-treatment LSM has also been studied as a prognostic factor for the occurrence of HCC in patients with SVR, with several cut-offs varying from 10 kPa to 19 kPa[10,21,27]. Semmler et al[10] also developed a predictive score for HCC that included the post-treatment LSM lower than 19 kPa as a protective variable. Our results align with this proposal, as an LSM value over 20 kPa increases the risk for HCC occurrence. We also identified 1-year-EOT LSM ≥ 15 kPa to be significantly related to HCC in Cox regression analysis, which suggests that a lower LSM after EOT provides a better prognosis.

The FIB-4 index score was created as an easily accessible tool in clinical practice to noninvasively assess the presence of advanced fibrosis[28]. Its use has been studied as an NIT capable of predicting HCC in patients with SVR after DAA[14,15,24-26,29,30]. Different cohorts, including patients with all stages of LSM and patients with advanced fibrosis and/or cirrhosis, have been investigated. Most results show a FIB-4 index higher than 3.25 after the EOT as a risk factor for HCC[15,26,30]. Among these studies, the time for evaluation also varied, with the score being performed from 12 weeks to 1 year after EOT. Ciancio et al[29] identified that a reduction in FIB-4 index to lower than 3.25 in the SVR was related to a lower risk of HCC. In our cohort, patients with a 1-year-EOT FIB-4 index lower than 3.25 had a higher cumulative survival free of HCC than those with a FIB-4 ≥ 3.25.

Regarding pre-treatment evaluation, Ioannou et al[25] showed that an FIB-4 index higher than 3.25 could be considered a predictor of incident HCC. However, this finding was controversial among studies. Nicoletti et al[24], in their cohort of people with cirrhosis, showed that the pre-treatment FIB-4 index and its variation did not predict HCC. Leal et al[14] included patients with all stages of LSM in a study that compared different biomarkers (FIB-4 index, AST to platelet ratio index, and albumin-bilirubin scores) and pre-treatment LSM as predictors of HCC. However, only LSM was considered a reliable HCC predictor. In our study, the pre-treatment FIB-4 index with a cut-off of 3.25 was also related to HCC.

Similar to LSM, the delta regarding pre- and post-treatment FIB-4 index did not impact HCC prediction in our study. A cohort of 551 patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis identified that delta FIB-4 after 12-24 weeks of SVR was an independent risk factor for HCC[31]. However, Nicoletti et al[24] did not find the same with delta FIB-4 after 1-year-EOT.

This study has some limitations. An analysis restricted only to patients with LSM available before and after treatment could give rise to selection bias. Also, the reduced number of patients with advanced fibrosis before treatment in our cohort makes it challenging to identify NIT values suitable for risk stratification in this population. In addition, data on alcohol consumption and other metabolic comorbidities besides DM were not available, limiting additional analyses. Finally, it has a retrospective design. However, it comprises a large cohort from two centers with homogeneous treatment and follow-up protocols and a well-defined interval for acquiring LSM. Furthermore, it is a real-life study whose results can be applied to similar cohorts of HCV SVR patients.

In people with cACLD and HCV-SVR, both pre- and after 1-year-post-EOT LSM have prognostic value in predicting the occurrence of HCC. Hence, each patient would need only one elastography evaluation, whether pre- or post-treatment. Likewise, the FIB-4 index score could also be evaluated only once in SVR patients, either pre- or 1-year-post-EOT. These findings should be considered when evaluating the economic burden of HCC surveillance.

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5593] [Cited by in RCA: 6420] [Article Influence: 802.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 2. | Fan R, Papatheodoridis G, Sun J, Innes H, Toyoda H, Xie Q, Mo S, Sypsa V, Guha IN, Kumada T, Niu J, Dalekos G, Yasuda S, Barnes E, Lian J, Suri V, Idilman R, Barclay ST, Dou X, Berg T, Hayes PC, Flaherty JF, Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Buti M, Hutchinson SJ, Guo Y, Calleja JL, Lin L, Zhao L, Chen Y, Janssen HLA, Zhu C, Shi L, Tang X, Gaggar A, Wei L, Jia J, Irving WL, Johnson PJ, Lampertico P, Hou J. aMAP risk score predicts hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1368-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Luna-Cuadros MA, Chen HW, Hanif H, Ali MJ, Khan MM, Lau DT. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis C virus cure. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:96-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Gillessen J, Reuken P, Hunyady PM, Reichert MC, Lothschütz L, Finkelmeier F, Nowka M, Allo G, Kütting F, Bürger M, Nierhoff D, Steffen HM, Schramm C. Evaluation of Ultrasound-based Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients at Risk: Results From a German Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2023;11:626-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Practice Guidelines Panel: Chair:; EASL Governing Board representative:; Panel members:. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series☆. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1170-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 866] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ioannou GN. HCC surveillance after SVR in patients with F3/F4 fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74:458-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bhattacharya D, Aronsohn A, Price J, Lo Re V; AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2023 Update: AASLD-IDSA Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;ciad319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ioannou GN, Green PK, Berry K. HCV eradication induced by direct-acting antiviral agents reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;S0168-8278(17)32273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Reiberger T, Lens S, Cabibbo G, Nahon P, Zignego AL, Deterding K, Elsharkawy AM, Forns X. EASL position paper on clinical follow-up after HCV cure. J Hepatol. 2024;81:326-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Semmler G, Meyer EL, Kozbial K, Schwabl P, Hametner-Schreil S, Zanetto A, Bauer D, Chromy D, Simbrunner B, Scheiner B, Stättermayer AF, Pinter M, Schöfl R, Russo FP, Greenfield H, Schwarz M, Schwarz C, Gschwantler M, Alonso López S, Manzano ML, Ahumada A, Bañares R, Pons M, Rodríguez-Tajes S, Genescà J, Lens S, Trauner M, Ferenci P, Reiberger T, Mandorfer M. HCC risk stratification after cure of hepatitis C in patients with compensated advanced chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2022;76:812-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N, Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, Jou JH, Kulik LM, Agopian VG, Marrero JA, Mendiratta-Lala M, Brown DB, Rilling WS, Goyal L, Wei AC, Taddei TH. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;78:1922-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 900] [Cited by in RCA: 1163] [Article Influence: 387.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 12. | de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2609] [Cited by in RCA: 2358] [Article Influence: 214.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 13. | Mezina A, Krishnan A, Woreta TA, Rubenstein KB, Watson E, Chen PH, Rodriguez-Watson C. Longitudinal assessment of liver stiffness by transient elastography for chronic hepatitis C patients. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:5566-5576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Leal C, Strogoff-de-Matos J, Theodoro C, Teixeira R, Perez R, Guaraná T, de Tarso Pinto P, Guimarães T, Artimos S. Incidence and Risk Factors of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Treated with Direct-Acting Antivirals. Viruses. 2023;15:221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alonso López S, Manzano ML, Gea F, Gutiérrez ML, Ahumada AM, Devesa MJ, Olveira A, Polo BA, Márquez L, Fernández I, Cobo JCR, Rayón L, Riado D, Izquierdo S, Usón C, Real Y, Rincón D, Fernández-Rodríguez CM, Bañares R. A Model Based on Noninvasive Markers Predicts Very Low Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk After Viral Response in Hepatitis C Virus-Advanced Fibrosis. Hepatology. 2020;72:1924-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ioannou GN, Green PK, Beste LA, Mun EJ, Kerr KF, Berry K. Development of models estimating the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after antiviral treatment for hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2018;69:1088-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tani J, Morishita A, Sakamoto T, Takuma K, Nakahara M, Fujita K, Oura K, Tadokoro T, Mimura S, Nomura T, Yoneyama H, Kobara H, Himoto T, Tsutsui A, Senoh T, Nagano T, Ogawa C, Moriya A, Deguchi A, Takaguchi K, Masaki T. Simple scoring system for prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence after hepatitis C virus eradication by direct-acting antiviral treatment: All Kagawa Liver Disease Group Study. Oncol Lett. 2020;19:2205-2212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nakai M, Yamamoto Y, Baba M, Suda G, Kubo A, Tokuchi Y, Kitagataya T, Yamada R, Shigesawa T, Suzuki K, Nakamura A, Sho T, Morikawa K, Ogawa K, Furuya K, Sakamoto N. Prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma using age and liver stiffness on transient elastography after hepatitis C virus eradication. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morisco F, Federico A, Marignani M, Cannavò M, Pontillo G, Guarino M, Dallio M, Begini P, Benigno RG, Lombardo FL, Stroffolini T. Risk Factors for Liver Decompensation and HCC in HCV-Cirrhotic Patients after DAAs: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ravaioli F, Conti F, Brillanti S, Andreone P, Mazzella G, Buonfiglioli F, Serio I, Verrucchi G, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Colli A, Marasco G, Colecchia A, Festi D. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk assessment by the measurement of liver stiffness variations in HCV cirrhotics treated with direct acting antivirals. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:573-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Semmler G, Alonso López S, Pons M, Lens S, Dajti E, Griemsmann M, Zanetto A, Burghart L, Hametner-Schreil S, Hartl L, Manzano M, Rodriguez-Tajes S, Zanaga P, Schwarz M, Gutierrez ML, Jachs M, Pocurull A, Polo B, Ecker D, Mateos B, Izquierdo S, Real Y, Ahumada A, Bauer DJM, Mauz JB, Casanova-Cabral M, Gschwantler M, Russo FP, Azzaroli F, Maasoumy B, Reiberger T, Forns X, Genesca J, Bañares R, Mandorfer M; cACLD-SVR Study Group. Post-treatment LSM rather than change during treatment predicts decompensation in patients with cACLD after HCV cure. J Hepatol. 2024;81:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Piedade J, Pereira G, Guimarães L, Duarte J, Victor L, Baldin C, Inacio C, Santos R, Chaves Ú, Nunes EP, Grinsztejn B, Veloso VG, Fernandes F, Perazzo H. Liver stiffness regression after sustained virological response by direct-acting antivirals reduces the risk of outcomes. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Knop V, Hoppe D, Vermehren J, Troetschler S, Herrmann E, Vermehren A, Friedrich-Rust M, Sarrazin C, Trebicka J, Zeuzem S, Welker MW. Non-invasive assessment of fibrosis regression and portal hypertension in patients with advanced chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated liver disease and sustained virologic response (SVR): 3 years follow-up of a prospective longitudinal study. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28:1604-1613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nicoletti A, Ainora ME, Cintoni M, Garcovich M, Funaro B, Pecere S, De Siena M, Santopaolo F, Ponziani FR, Riccardi L, Grieco A, Pompili M, Gasbarrini A, Zocco MA. Dynamics of liver stiffness predicts complications in patients with HCV related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:1472-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ioannou GN, Beste LA, Green PK, Singal AG, Tapper EB, Waljee AK, Sterling RK, Feld JJ, Kaplan DE, Taddei TH, Berry K. Increased Risk for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Persists Up to 10 Years After HCV Eradication in Patients With Baseline Cirrhosis or High FIB-4 Scores. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1264-1278.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Watanabe T, Tokumoto Y, Joko K, Michitaka K, Horiike N, Tanaka Y, Hiraoka A, Tada F, Ochi H, Kisaka Y, Nakanishi S, Yagi S, Yamauchi K, Higashino M, Hirooka K, Morita M, Okazaki Y, Yukimoto A, Hirooka M, Abe M, Hiasa Y. Simple new clinical score to predict hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained viral response with direct-acting antivirals. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pons M, Rodríguez-Tajes S, Esteban JI, Mariño Z, Vargas V, Lens S, Buti M, Augustin S, Forns X, Mínguez B, Genescà J. Non-invasive prediction of liver-related events in patients with HCV-associated compensated advanced chronic liver disease after oral antivirals. J Hepatol. 2020;72:472-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3814] [Article Influence: 190.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ciancio A, Ribaldone DG, Spertino M, Risso A, Ferrarotti D, Caviglia GP, Carucci P, Gaia S, Rolle E, Sacco M, Saracco GM. Who Should Not Be Surveilled for HCC Development after Successful Therapy with DAAS in Advanced Chronic Hepatitis C? Results of a Long-Term Prospective Study. Biomedicines. 2023;11:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Azzi J, Dorival C, Cagnot C, Fontaine H, Lusivika-Nzinga C, Leroy V, De Ledinghen V, Tran A, Zoulim F, Alric L, Gournay J, Bronowicki JP, Decaens T, Riachi G, Mikhail N, Soliman R, Shiha G, Pol S, Carrat F, Ganne-Carrié N; ANRS-AFEF Hepather Study group. Prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis after sustained virologic response. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46:101923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xu S, Qiu L, Xu L, Liu Y, Zhang J. Development and validation of a nomogram for assessing hepatocellular carcinoma risk after SVR in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Infect Agent Cancer. 2024;19:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/