Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.113793

Revised: September 20, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 86 Days and 0.1 Hours

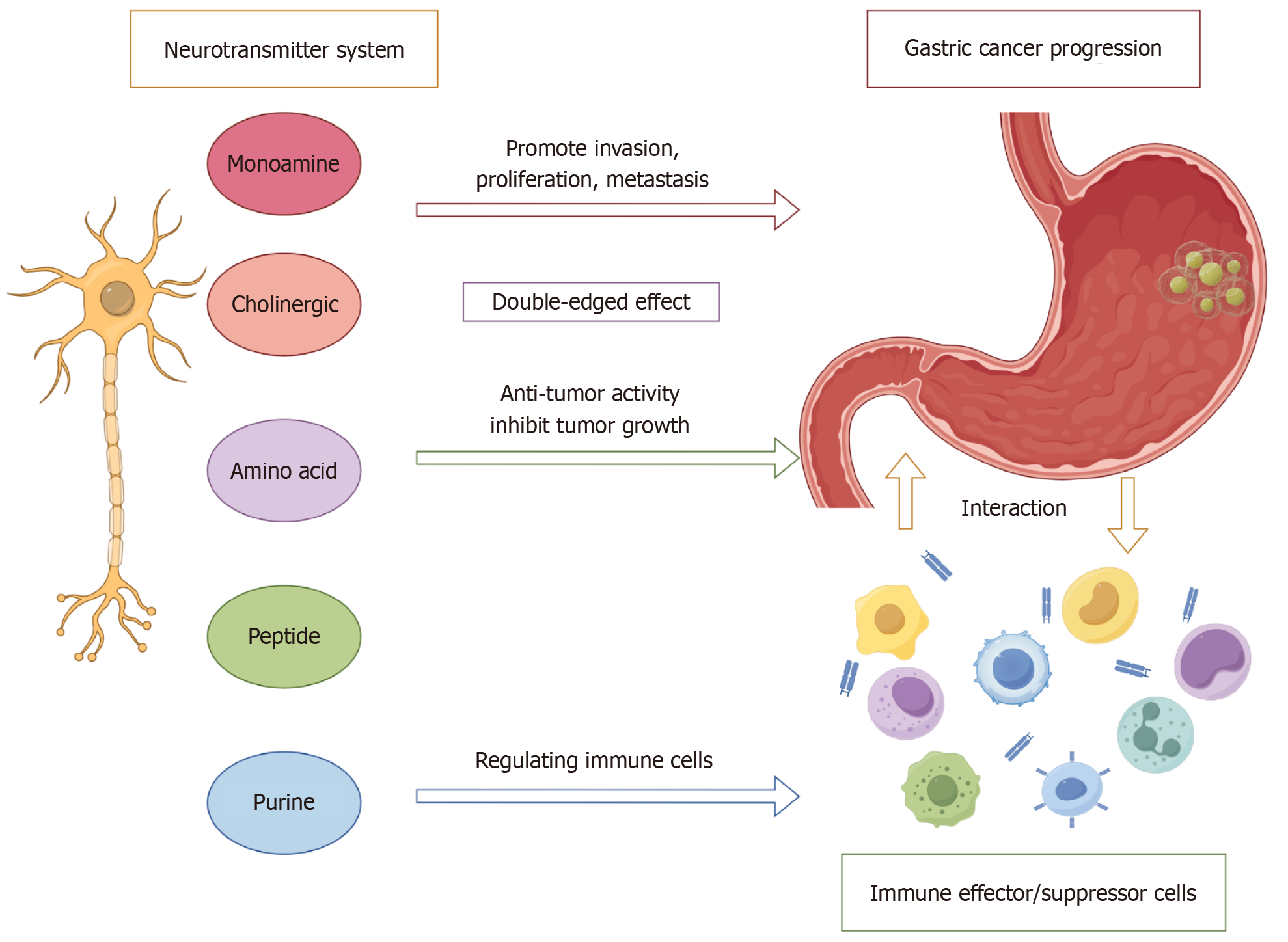

Emerging evidence underscores the critical, yet frequently underrecognized, role of the nervous system in the development and progression of gastric cancer (GC), primarily mediated through complex neuro-tumoral interactions and modulation of immune responses. GC cells actively invade neural structures, inducing aber

Core Tip: The nervous system plays a critical but underrecognized role in gastric cancer (GC) progression through bidirectional neuro-tumoral interactions. Neurotransmitters—including norepinephrine, acetylcholine, glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid, adenosine, and neuropeptide Y—produced by both neurons and malignant cells, actively reprogram the tumor microenvironment. These mediators regulate proliferation, invasion, metastasis, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance in GC. This review highlights advances in understanding neurotransmitter-driven mechanisms and introduces the concept of “neuro-gastric oncology”, providing a rationale for novel therapeutic strategies targeting neuro-tumoral signaling pathways.

- Citation: Liu YZ, Liu WX, Deng WH. Advances in the study of the relationship between neurotransmitters and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(44): 113793

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i44/113793.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.113793

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with over one million new diagnoses annually. Approximately 320000 of these cases occur each year in China[1,2]. A downward pattern has been observed in the population attributable fraction (PAF) for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, cigarette smoking, intake of pickled vegetables, and alcohol use, whereas the PAF associated with excess body mass index and diabetes has continued to rise. Nevertheless, H. pylori infection is expected to remain the predominant determinant of GC risk in China for the fore

Aberrant neurotransmitter expression patterns within GC have been shown to activate diverse intracellular signaling pathways, thereby contributing to tumor initiation and progression. For example, norepinephrine (NE) signal through β2-adrenergic receptors, facilitating metastasis via MMP-7/STAT3 activation and concurrently suppressing CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses[7-9]. Acetylcholine (Ach) engages M3 muscarinic and α7 nicotinic receptors, promoting cancer stemness via the Wnt/YAP axis and conferring chemoresistance through PI3K/AKT signaling[10,11]. Dysregulation of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters—including glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)—alters tumor metabolic programs[12,13], while adenosine (ADO), via the CD73/A2AR axis[14], and neuropeptide Y (NPY), through Y1 receptor signaling, contribute to immunosuppressive niche formation[15] (Table 1).

| Neurotransmitter | Receptor | Effects on gastric cancer |

| NE/E | β2-AR[6,8,9,11,23,26-30] | Promote proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT, metastasis, angiogenesis, DNA damage; inhibit immunosuppressive TME |

| DA | D2R[31,32,39,41,42] | Inhibit growth, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis; promote antitumor immunity |

| 5-HT | HTR2B[52-55] | Promote tumor occurrence, growth; inhibit ferroptosis and immunosuppressive TME |

| HTR1D[56] | Promote proliferation and migration | |

| ACh | M3[62,66,69-71] | Promote proliferation, tumor growth, and NGF expression |

| α5-nAChR[76-78] | Promote proliferation, EMT; inhibit apoptosis | |

| α7-nAChR[79-82,85-91] | Promote proliferation, invasion, migration, angiogenesis, antitumor immunity; inhibit chemotherapy efficacy | |

| GABA | GABA-A[102-104,106] | Promote proliferation, tumor growth; immune escape |

| GABRD[105,107] | Promote proliferation, invasion; inhibit apoptosis | |

| Glu | GRIK 2[110] | Inhibit tumor growth and migration |

| Gastrin | CCK2R[122-126] | Promote proliferation, invasion, migration, angiogenesis; inhibit apoptosis |

| CCK | CCK2R[124,130] | Promote proliferation, tumor growth |

| SST | SSTR1[134] | Inhibit proliferation, invasion, migration |

| SSTR3[133] | Inhibit proliferation and apoptosis | |

| SP | NK1R[119,143,144] | Promote proliferation, invasion, migration, adhesion |

| NPY | Y1R[15,153] | Promote proliferation, migration, angiogenesis |

| Y2R[120,154] | Promote proliferation and angiogenesis | |

| ADO | A2B[156] | Promote EMT and migration |

| A2A[14,158] | Promote tumor escape | |

| ATP | P2X7R[155,159-161] | Promote tumor occurrence, proliferation, EMT, invasion, migration |

This review integrates current findings on the role of distinct neurotransmitter classes in GC, emphasizing their effects on the TME and outlining potential therapeutic implications. Collectively, these insights lay the groundwork for a conceptual framework of “neuro-gastric oncology”, providing a rationale for developing targeted interventions that disrupt neurotransmitter-driven tumor mechanisms (Figure 1).

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases. Keywords included: "Neurotransmitter”, "gastric cancer”, "neuro-immune axis”, "monoamine”, "acetylcholine”, "GABA”, "glutamate”, "neuropeptide”, "purinergic signaling”, and specific receptor names (e.g., "β2-adrenergic receptor”, "M3 muscarinic receptor"). Articles published between 2000 and 2025 were included, with emphasis on original research, meta-analyses, and high-impact reviews. Studies were selected based on relevance to neurotransmitter mechanisms in GC, including in vitro, in vivo, and clinical evidence. Although this review emphasizes GC, relevant findings on neurotransmitters in other gastrointestinal malignancies (e.g., colorectal, pancreatic) may also provide insights and will be briefly discussed.

Monoamine neurotransmitters constitute a predominant class of signaling molecules in the nervous system, including epinephrine (E), NE, dopamine (DA), and serotonin (5-HT). Studies have shown that neurotransmitters such as NE are abundantly released through activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis by the sympathetic nervous system in response to stress[16]. Notably, increasing evidence suggests that stress responses critically enhance tumor cell proliferation and migration[17]. From the standpoint of pathophysiology, stress can manifest as either acute or chronic, with the latter being more consistently implicated in the initiation and progression of malignancies in experimental models[18]. Sustained stress exposure results in persistent secretion of catecholamines, which, as demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo studies, modulate GC cell behavior by driving oncogenic traits such as uncontrolled growth, enhanced invasiveness, and metastatic spread[19,20]. Although these observations delineate critical mechanistic connections, the majority of supporting evidence derives from preclinical research, leaving their clinical relevance incompletely clarified. Within this context, the present section examines the potential roles of principal monoamine neurotransmitters in shaping the biological characteristics of GC cells.

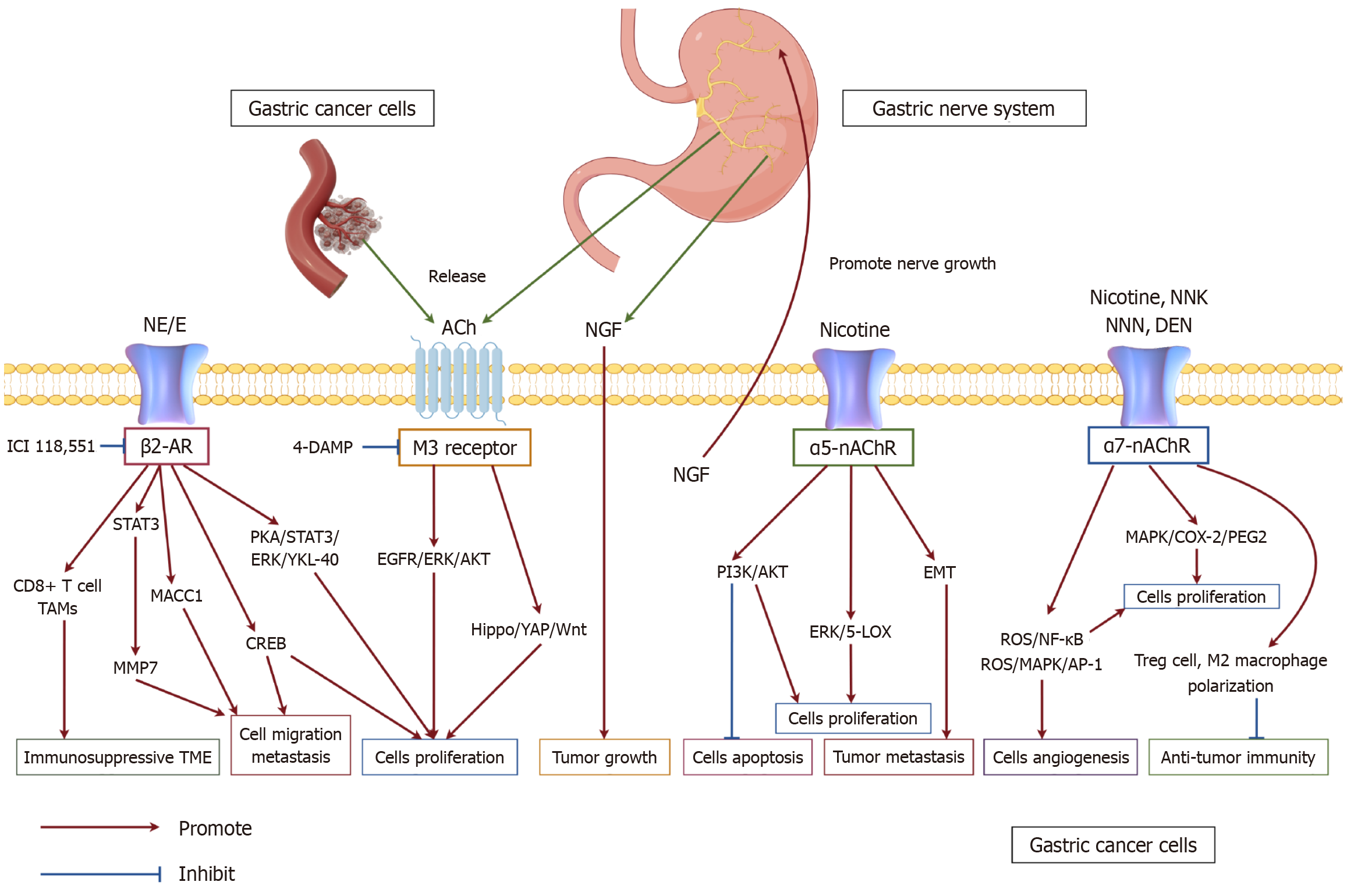

E and NE primarily function within the sympathetic nervous system by engaging two receptor types: ADRA and ADRB receptors. Notably, research has indicated that in GC progression, these catecholamines predominantly interact with β2-adrenergic receptors, initiating downstream signaling cascades[7]. From a metastasis perspective, catecholamines have been shown to enhance the expression of premetastatic matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in tumor cells[21]. Specifically, STAT3 and c-Jun, activated by catecholamines, bind to the AP-1 binding site (-67 to -61) on the MMP-7 promoter, leading to transactivation of MMP-7 and facilitating tumor dissemination[8]. GC cells exhibit responsiveness to NE and cate

DA, a key neurotransmitter in the gastrointestinal tract, plays diverse physiological roles in intestinal function. Research has demonstrated that DA can suppress tumor cell proliferation, invasion, growth, and angiogenesis[31,32]. Its effects in GC cells are mediated through DA receptors (DRs), which are categorized into five subtypes (D1R-D5R) that are widely distributed in the gastrointestinal system[33]. These receptors are further classified into two families: D1-like (D1, D5), which stimulate adenylyl cyclase to elevate intracellular cAMP, and D2-like (D2, D3, D4), which reduce cAMP levels and regulate Ca2+ as well as phospholipase C signaling pathways[34,35]. Among them, D2R has been implicated in suppressing IGF-I-driven proliferation of GC cells in preclinical models[32]. DA exerts its inhibitory effects on invasion, migration, and MMP-13 production by acting through D2R to suppress EGFR and AKT activation[36]. Conversely, overexpression of DA- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein DARPP-32 has been identified as an early molecular event in gastric tumorigenesis. Preclinical data suggest that DARPP-32 can activate the IGF1R/SRC/STAT3 axis, thereby supporting tumor initiation[37,38]. As discussed earlier, NE and E enhance VEGF expression, thereby promoting tumor angiogenesis. In contrast, DA does not upregulate proangiogenic molecules such as VPF/VEGF but instead downregulates VEGFR-2-mediated signaling in tumor endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells via D2R[39,40]. Studies indicate that at specific concentrations, DA enhances antitumor immunity in vivo by activating effector T cells (Teffs) while suppressing regulatory T cells (Tregs). By contrast, in cancer patients, markedly elevated circulating DA can compromise Teff proliferation and cytotoxic function through receptors such as D1R, and may also induce lymphocyte apoptosis via oxidative stress, ultimately resulting in immunosuppression. Moreover, DA promotes the polarization of TAMs toward an M1-like phenotype through D2R signaling, highlighting its paradoxical function as both an enhancer and suppressor of immune responses within the TME[41,42]. Interestingly, a study by Liu et al[43] revealed that DA transporter gene (SLC6A3) expression was markedly elevated in GC tissues but significantly reduced following surgical resection. This suggests that SLC6A3, as a DA transporter, may modulate GC progression by influencing DA-associated genes. Additionally, the DR antagonist ONC201, evaluated in preclinical and early translational studies in pancreatic cancer, has shown promise in combination therapies[44]. Nevertheless, direct clinical evidence in GC is currently lacking, and the therapeutic potential of targeting DA pathways requires rigorous clinical validation.

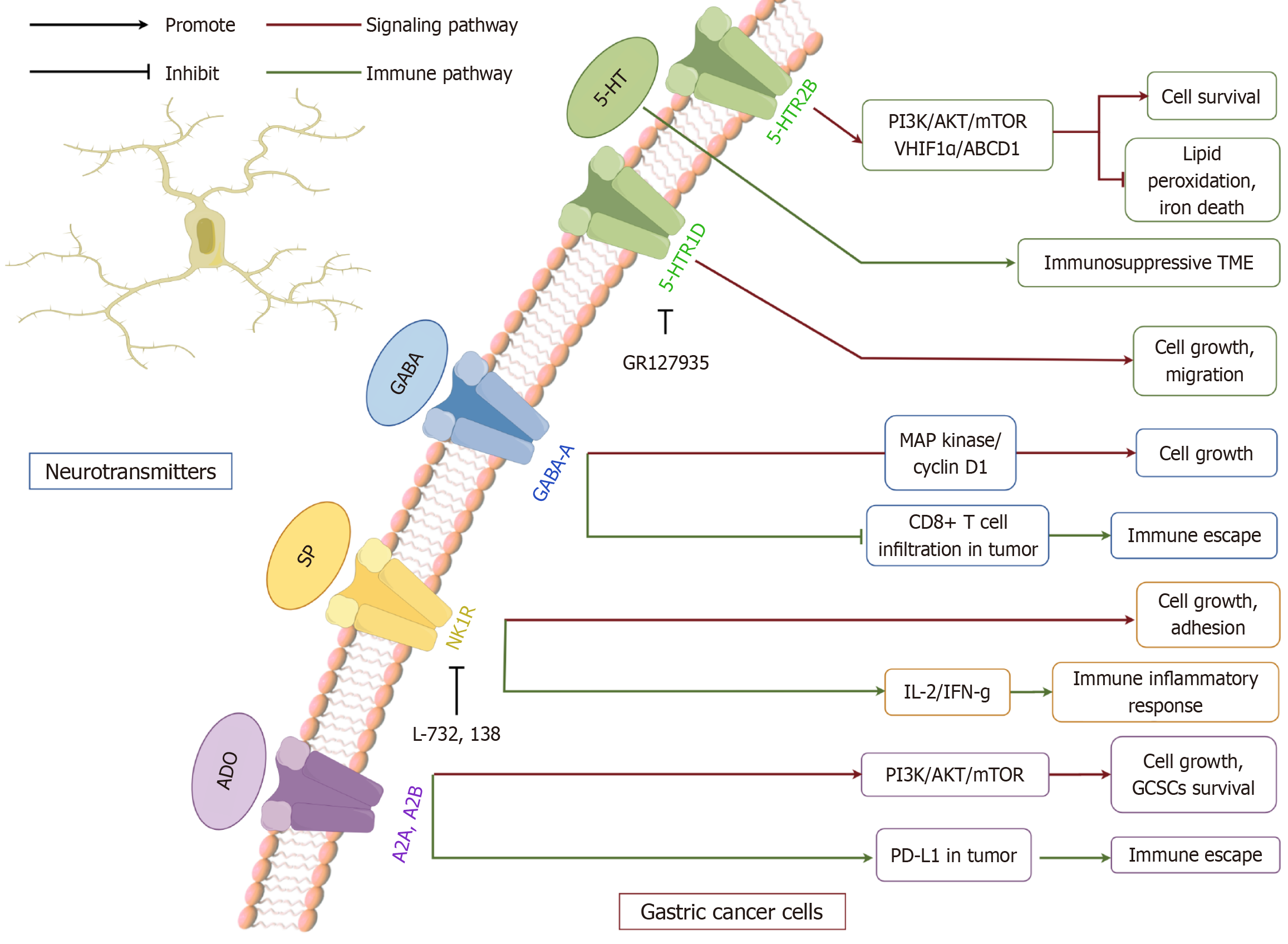

5-HT, a biogenic amine derived from tryptophan, is a well-established neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. It plays a crucial role in modulating gastrointestinal motility, vasodilation, and secretion[45,46]. The 5-HT system is regulated by seven receptor families (5-HTR1-5-HTR7) and 17 subtypes (HTR1A-F, 2A-C, 3A-E, 4, 5A, 6, and 7), which include both G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels[45,47]. Within the gastrointestinal tract, smooth muscle, enteric neurons, epithelial cells, and immune cells predominantly express 5-HTR1-4, and 5-HTR7[48]. Notably, approximately 90% of 5-HT is synthesized and localized within enterochromaffin cells[49]. Preclinical evidence suggests that dysregulated 5-HT signaling may contribute to tumorigenesis. Several receptor antagonists, including ondansetron, sertraline, and fluoxetine, have demonstrated tumor-suppressive effects in cell and animal models[50-52]. Recent findings suggest that abnormal overexpression of the 5-HTR2B subtype contributes to tumorigenesis. HTR2B plays a pivotal role in promoting GC cell survival by modulating the PI3K signaling cascade. Additionally, its activation enhances HIF1α and ABCD1 expression while reducing lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. This study further elucidated the correlation between HTR2B receptor expression and clinical prognosis in GC patients[53]. Previous reports have indicated that the HTR2B and 5-HTR7 signaling pathways promote the development of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, while the latter promotes tumor development. Abnormal 5-HT signaling can promote tumor growth and contribute to the formation of an immunosuppressive TME that supports tumor survival[54,55]. In addition, expression of 5-HTR1D has been associated with proliferation marker Ki-67 in GC specimens. Inhibition of 5-HTR1D, either pharmacologically or genetically, reduced proliferation and migration in vitro and impaired cell cycle progression[56]. These findings suggest potential prognostic and therapeutic relevance, but they remain largely restricted to preclinical studies. While this evidence highlights a potential connection between 5-HT receptor expression and GC prognosis, the underlying mechanisms remain insufficiently explored. Clinical evidence is still emerging, and most data are derived from preclinical models. Further human studies are needed to validate these mechanisms. Further human studies are essential to establish the clinical significance of these pathways and to determine whether serotonergic modulation could represent a viable therapeutic strategy.

ACh serves as a crucial neurotransmitter within both central and peripheral nervous systems, where it plays essential roles in gastric physiology. Its primary functions in the stomach include stimulating gastric acid secretion, enhancing gastric motility to facilitate emptying, and inducing the release of pepsinogen from chief cells in the gastric mucosa, thereby aiding digestion[57-59]. Beyond its physiological roles, ACh is implicated in the pathogenesis of various gastric disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, and GC[60-62]. Emerging evidence indicates that ACh contributes to GC progression by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, primarily through the upregulation of muscarinic M3 receptors and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), a key enzyme in ACh biosynthesis[63]. Given its involvement in tumorigenesis, this review aims to further explore the influence of ACh on GC through distinct muscarinic and nicotinic ACh receptor subtypes.

Muscarinic receptors, classified as class A (rhodopsin-like) GPCRs, are distinct from nicotinic receptors due to their preferential affinity for muscarine over nicotine[64]. Five principal subtypes (M1-M5), encoded by CHRM1-CHRM5, mediate various parasympathetic functions, with the M3 receptor being the most abundantly expressed subtype in the gastrointestinal tract[65]. GC cells autonomously produce and secrete ACh, which activates M3 receptors in both autocrine and paracrine manners, triggering EGFR transactivation and facilitating tumor cell proliferation. Compared with normal gastric epithelial cells, GC cell lines exhibit elevated expression of ChAT, further amplifying autocrine and paracrine ACh signaling via M3R and EGFR pathways to promote tumorigenesis[62,63]. Preclinical studies have implicated M3R in driving proliferation through EGFR/AKT activation[66], and inhibition with antagonists such as 4-DAMP or Tuffina reduced proliferation, sensitized cells to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and promoted apoptosis[62,67]. Recent investigations have explored the involvement of the cholinergic system in tumor cell proliferation and oncogenesis. Studies utilizing Dclk-positive cluster cells revealed that cholinergic stimulation in the gastric epithelium induces NGF expression, which subsequently fosters tumor development. This suggests a positive feedback loop where NGF secretion further enhances cholinergic nerve expansion[68]. The vagus nerve has also been identified as a critical modulator of Wnt signaling in gastric tumorigenesis, a pathway essential for epithelial homeostasis in the stomach and intestine and implicated in certain GC subtypes[69,70]. Recent findings indicate that ACh enhances LGR5+ stem cell proliferation and tumor growth through Hippo-YAP-mediated regulation of Wnt signaling[71,72]. Knockdown of M3R in animal models suppressed Wnt signaling and tumor progression, while increased intratumoral innervation correlated with disease severity[69]. Beyond GC, studies in colorectal cancer cells showed that muscarinic blockade reduced PD-L1/PD-L2 expression and limited immune evasion[73]. These data suggest that cholinergic signaling may influence both tumor-intrinsic growth and immune modulation. However, much of the current evidence is derived from preclinical systems, and whether muscarinic signaling represents a clinically actionable target in GC remains uncertain.

A substantial body of research indicates that nAChRs serve as key mediators of nicotine’s effects on GC. Compared to normal gastric epithelial cells, GC cells exhibit an increased number and density of β-subunit-containing nAChRs[74]. Early investigations have linked prolonged nicotine exposure to a higher incidence of gastric malignancies[75]. Although current knowledge regarding nAChR-mediated signaling in GC remains limited, two subtypes, α5 and α7, have been extensively examined. Elevated α5-nAChR expression has been reported in gastric tumor specimens, and preclinical studies suggest that its activation promotes proliferation and resistance to cisplatin via AKT signaling, accompanied by upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Survivin and Bcl-2[76,77]. Nicotine has also been shown to activate ERK/5-LOX signaling, thereby enhancing proliferation, EMT, and invasion in cell-based models[78]. The α7 subtype exhibits a broader expression profile. Nicotine and tobacco-derived nitrosamines (NNK, NNN, DEN) bind strongly to α7-nAChR, initiating downstream signaling linked to tumor growth and invasion[79-81]. α7-nAChR is expressed in macrophages and T cells and is involved in the regulation of immune function and inflammatory response. α7-nAChR activation promotes enhanced Treg cell function and M2-type macrophage polarization, thereby suppressing anti-tumor immunity[82]. Wang et al's research[83] demonstrated that NNK significantly enhances the migratory capacity of human gastric adenocarcinoma cells (AGS) through α7-nAChR activation. Inhibition of α7-nAChR, either via receptor antagonists or siRNA-mediated knockdown, effectively suppressed NNK-induced cell migration, confirming that this effect is specifically mediated by α7-nAChR[84]. Moreover, both nicotine and NNK have been reported to activate nAChRs and β-adrenergic receptors via MAPK and COX-2/PGE2 signaling, leading to increased GC cell proliferation. These findings align with Wong et al’s study[85], which demonstrated that nicotine directly acts on β-adrenergic receptors, promoting the growth and angiogenesis of tumors within the gastrointestinal tract. Such evidence suggests a functional interplay between α7-nAChR and β-adrenergic receptors in nicotine-induced GC progression. Additionally, nicotine enhances angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and metastatic potential through α7-nAChR-mediated activation of the COX-2/EGF/VEGFR signaling axis[86,87]. Recent studies have revealed that nicotine upregulates IL-8 expression in AGS cells through ROS/NF-κB and ROS/MAPK (Erk1/2, p38)/AP-1 pathways, subsequently stimulating endothelial cell proliferation and tumor-associated angiogenesis[88]. Furthermore, α7-nAChR knockdown sensitized GC cells to taxanes, 5-FU, and ixabepilone, suggesting a role in drug resistance[89-91]. These findings provide critical insights into the potential utility of α7-nAChR expression as a predictive biomarker for chemotherapy efficacy in GC (Figure 2).

Amino acid neurotransmitters, including GABA and glutamate, play dual roles in neural signaling and metabolic regulation[12]. Within normal gastric tissues, glutamate contributes to the modulation of gastric acid secretion and the preservation of mucosal integrity[92], while GABA exerts inhibitory effects that regulate smooth muscle contraction and facilitate mucosal repair[93]. Collectively, these neurotransmitters are essential for preserving gastric homeostasis. In the context of GC, their roles become more intricate and ambivalent[94]. GABA, through its receptors, has been implicated in suppressing the invasive potential of certain GC cells. Conversely, glutamate enhances tumor cell proliferation, mig

GABA is distributed throughout both the central and peripheral nervous systems[97,98]. Within the central nervous system, GABA primarily functions as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, modulating energy dynamics in GABAergic neurons[99]. In the peripheral nervous system, it is found in neurons of the enteric plexus, where it similarly serves as a neurotransmitter within the digestive tract[100]. GABA receptors are classified into two major categories: Ligand-gated ionotropic receptors, including GABA-A and GABA-C, and G-protein-coupled metabotropic GABA-B receptors. These receptors regulate the release of neurotransmitters such as ACh in the intestinal nervous system, thereby affecting gastrointestinal motility and gastric acid secretion[101]. Matuszek et al’s research[102] was the first to discover elevated levels of GABA expression in GC. The results showed that muscimol, a GABA-A receptor agonist, significantly reduced the incidence of chemically induced gastric tumors from 50% to 15%. Tumor-derived GABA has been implicated in the activation of β-catenin signaling, which contributes to tumor progression[103]. Research conducted by Maemura et al[104] demonstrated that GABA facilitated the proliferation of KATO III GC cells through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms via the GABA-A receptor, leading to the upregulation of MAP kinase and cyclin D1 expression. Recent research highlights the δ subunit of GABRD as a potential contributor to malignant phenotypes. GABRD mRNA is upregulated in tumor specimens, correlating with poor prognosis in preclinical analyses. Silencing GABRD or inhibiting its function in vitro reduced proliferation and invasion while promoting apoptosis[105]. Additionally, GABRD may influence the TME: 4-acetylaminobutyric acid activation of GABRD on CD8+ T cells inhibited AKT1 signaling, reducing T cell activation and infiltration. Blockade of this pathway in mouse models enhanced responses to immune checkpoint inhibition, suggesting a potential therapeutic avenue[103,106]. GABRD may also upregulate CCND1, further supporting proliferation and invasion in GC cells, though these findings remain largely preclinical[107]. Overall, GABA signaling appears to exert both pro- and anti-tumor effects depending on receptor subtype and cellular context. Clinical evidence remains scarce, and further translational studies are needed to clarify the relevance of these mechanisms in human GC.

Glutamate serves as the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, with receptors categorized as mGluRs (mGlu1-mGlu8) and ionotropic glutamate receptors, including NMDA, AMPA, and kainate subtypes[108]. Beyond its role in excitotoxicity, functional Glu signaling has been implicated in tumorigenesis and cancer progression[109]. In GC, GRIK2, a member of the ionotropic Glu receptor family, has been associated with growth suppression and inhibition of tumor cell migration[110]. Conversely, the glutamate ionotropic receptor GRIN2D appears to facilitate tumor progression by promoting calcium influx into GC cells and activating the p38 MAPK signaling cascade[111]. mGluRs have not been extensively studied in GC, but their tumor-promoting roles in other malignancies suggest potential relevance as therapeutic targets[13]. Beyond receptor-mediated effects, amino acid metabolism also modulates the efficacy of chemotherapy in GC. Alterations in glutamine, serine, and glycine levels have been shown to induce ubiquitination-mediated degradation of KDM4A, a process that enhances the responsiveness of GC cells to chemotherapeutic agents[95]. Collectively, these results indicate that glutamate-associated signaling and metabolic pathways could modulate tumor behavior and responses to therapy, although the majority of supporting data remain preclinical. Such observations offer a foundation for exploring targeted interventions in GC in future clinical settings.

Peptide neurotransmitters are bioactive molecules composed of amino acids linked by peptide bonds, broadly distributed in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. These molecules play crucial roles in neural communication and physiological regulation. Representative members of this group include gastrin, cholecystokinin (CCK), somatostatin (SST), substance P (SP), and NPY. By interacting with their respective receptors, these neurotransmitters modulate diverse biological processes such as pain transmission, emotional regulation, metabolism, and gastrointestinal motility and secretion[112]. In normal gastric physiology, gastrin and SST contribute to the regulation of gastric acid secretion, while SP facilitate gastrointestinal contraction, thereby accelerating gastric emptying[113-115]. Additionally, calcitonin gene-related peptide has been shown to promote vasodilation in gastric blood vessels and enhance mucus secretion, aiding in the repair of mucosal injury[116]. In the context of GC, peptide neurotransmitters exhibit distinct pathological roles. The peptidergic signaling system plays a fundamental role in cancer progression, influencing key processes such as cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis[117]. Overexpression of gastrin has been linked to the activation of the MAPK/PI3K pathway via its interaction with the CCK2 receptor, driving cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis[118]. Moreover, SP has been implicated in enhancing the proliferative, adhesive, migratory, and invasive capacities of MKN45 GC cells in vitro[119]. NPY exerts its tumor-promoting effects through Y2 receptor activation, facilitating angiogenesis and establishing an immunosuppressive TME that promotes metastasis[120]. In contrast, SST and its analogs, such as octreotide, function as inhibitors of EGF/VEGF signaling, thereby suppressing tumor progression and inducing apoptotic pathways[121].

Gastrin, predominantly secreted by G cells in the gastric antrum, regulates acid secretion. Chronic hypergastrinemia, as observed in H. pylori infection or autoimmune gastritis, has been linked to mucosal hyperplasia and neoplastic changes in preclinical studies[122]. Certain GC cells exhibit the capacity for autocrine gastrin secretion, which, upon interaction with CCK2 receptors, activates downstream signaling cascades, including the MEK and PI3K pathways. This activation promotes cyclin D1 expression, enhances proliferative activity, and suppresses apoptotic processes by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2[123,124]. Furthermore, gastrin facilitates cancer cell invasion and migration through β-catenin and snail-mediated repression of E-cadherin expression[125]. Additionally, it induces VEGF secretion, fostering angiogenesis and sustaining metastatic progression[126]. However, findings by Zu et al[127] suggest that excessive gastrin levels may exert tumor-suppressive effects by activating the ERK-P65-miR-23a/27a/24 axis, introducing a nuanced perspective on its dual role in gastric malignancy.

CCK, a peptide hormone secreted by I cells of the small intestine, functions as both a gastrointestinal regulator and a neurotransmitter within the central and peripheral nervous systems. Its biological effects are mediated through two G protein-coupled receptors, CCK1R and CCK2R. Notably, CCK2R is frequently overexpressed in GC, making it a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target[128]. CCK cooperates with gastrin to amplify oncogenic signaling through the MAPK and PI3K pathways, thereby accelerating tumor progression[123,124,129]. Research by Sun et al[130] demonstrated that co-administration of CCK2R inhibitors alongside COX-2 inhibitors significantly enhances apoptosis and suppresses GC cell proliferation.

SST, a neuropeptide synthesized by the hypothalamus, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cells, and peripheral nervous system, predominantly exists in two biologically active isoforms, SST-14 and SST-28. Its functions are mediated by binding to SST receptors (SSTR1-SSTR5)[131]. SST exerts strong antitumor properties in GC by inhibiting tumor development and progression[132]. The SST analog octreotide has been found to suppress GC cell proliferation and induce apoptosis through activation of SSTR3 in SSTR3-expressing gastric tumors[133]. Moreover, a study by Zhao et al[134] reported that SSTR1 expression is downregulated in GC, and its overexpression significantly impairs tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. These findings suggest a promising avenue for the development of novel targeted therapies against GC.

SP, a key member of the tachykinin family, originates from the preprotachykinin A gene. Its biological effects are predominantly mediated through the NK1R, a GPCR[135]. Upon binding to NK1R, SP activates multiple tumor-promoting pathways, including PI3K, MAPK, and canonical Wnt signaling, contributing to cancer progression[136]. Early clinical studies led by Wilander et al[137] discovered SP immune reactivity in certain gastrointestinal malignancies. Tatsuta et al[138] demonstrated that prolonged SP administration in Wistar rats elevated both the incidence of MNNG-induced gastric tumors and the abnormal gastric mucosal marker index. These early observations underscore the necessity of elucidating the underlying mechanisms, with particular emphasis on the overexpression of NK1R in GC cells[119,135,139]. The presence of NK1R has been confirmed in human gastric carcinoma tissues as well as in the GC cell, where SP stimulation enhances proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion in vitro[119]. SP, a capsaicin-sensitive sensory neuropeptide, can induce acute inflammatory responses by increasing vasodilation and extravasation in the neuro-immune-metabolic axis, and SP enhances immunomodulation of mesenchymal stem cells through IL-2/IFN-g secretion in T cells[140,141]. Muñoz et al’s research[142] on nuclear expression patterns in GC cells revealed that SP exhibits higher nuclear localization in malignant cells compared to normal counterparts. Conversely, the NK1R antagonists L-732138 can effectively suppress gastrointestinal tumor cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in GC cells[143]. In addition, recent studies by Guo et al[144] demonstrated that exosomal miR-877-5p inhibits SP-driven GC cell proliferation, further supporting its potential as a therapeutic avenue. Although these data support a potential pro-tumor role for SP, direct evidence in human GC remains limited, and translational studies are needed to confirm clinical relevance.

NPY, a crucial component of the pancreatic polypeptide family, serves as a neurotransmitter distributed throughout both the central and peripheral nervous systems[145]. This family also includes PP and PYY, with NPY exerting its biological effects primarily through interactions with five receptor subtypes, particularly Y1 and Y2 receptors. Recent research has implicated NPY in the pathogenesis and advancement of multiple malignancies, including brain tumors, breast carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, colorectal malignancies, esophageal cancer, and Ewing sarcoma[146-150]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying NPY's role in GC remain largely unexplored. In early studies, Bilchik et al[151] conducted animal model studies on genetically predisposed gastric neuroendocrine tumors, demonstrating that the loss of gastric parietal cells could accelerate tumor development, the elevated serum and tumor tissue PYY concentrations were detected in these models. In contrast, a case report by Solt et al[152] documented increased PP levels in a GC patient. Furthermore, reduced plasma NPY levels in individuals with colorectal or GC were linked to both tumor burden and weight loss[149]. In the context of cancer prognosis, plasma Y1R levels have been proposed as potential biomarkers for metastasis and disease progression, as elevated Y1R expression correlates with lymphatic dissemination, advanced disease stage, perineural invasion, and diminished cancer-specific survival[15,153]. Extensive investigations suggest that antagonists targeting YR receptors not only inhibit cancer cell proliferation and tumor neovascularization—such as the Y2R antagonist BIIE0246, which reduces melanoma tumor mass, angiogenesis, and serum VEGF levels—but also induce direct tumor cell apoptosis[120,154]. Meanwhile, Y5R agonists promote VEGF release from breast cancer cells, fostering angiogenesis, further substantiating the tumor-suppressive potential of YR antagonism[147]. Clinical evidence remains scarce, although plasma Y1R levels have been proposed as potential biomarkers for disease progression and metastasis.

Purine neurotransmitters, typified by ADO and ATP, constitute a class of low-molecular-weight signaling molecules that exert regulatory effects by interacting with purinergic receptors, including the P1 and P2 receptor families. These neurotransmitters are extensively distributed across both central and peripheral nervous systems, where they participate in immune modulation, inflammatory cascades, and the remodeling of the TME. In recent years, their involvement in oncogenesis and cancer progression has garnered increasing scientific interest. Increasing evidence from preclinical studies indicates that purinergic signaling may participate in cancer-related processes, and dysregulation of these pathways has been reported in GC, suggesting potential therapeutic relevance[155].

ADO, a purine-derived neurotransmitter and metabolic byproduct, modulates immune responses, tumor growth, and resistance to therapy through activation of purinergic receptors such as A2A and A2B within the TME. In recent years, its role in GC pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions has gained significant research interest. Preclinical data indicate that A2B receptor expression is elevated in GC tissues and may influence EMT markers, contributing to enhanced metastatic traits in cell line models[156]. A study by Liu et al[157] demonstrated that blocking the A2A receptor preserves the stem-like characteristics of GC cells by triggering the PI3K signaling cascade, thereby contributing to radiation resistance in MFC and MKN-45 cell lines. Investigations into ADO-mediated signaling and its implications for immunotherapy have intensified in recent years. ADO synthesis is primarily catalyzed by CD73, encoded by the NT5E gene, which converts AMP into ADO. Elevated CD73 expression in GC has been closely associated with poorer patient prognosis and reduced survival rates. By engaging A2A receptors on immune cells, including T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, ADO suppresses immune infiltration and function, fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment that facilitates tumor immune evasion. Furthermore, ADO signaling enhances PD-L1 expression in malignant cells, thereby promoting resistance to immune checkpoint blockade therapies[14,158]. While these findings underscore a potential role of ADO in tumor immune evasion, clinical validation remains limited.

ADO triphosphate, a fundamental molecule in cellular energy metabolism, also functions as a critical neurotransmitter, exerting diverse effects on GC through its interaction with distinct purinergic receptors. Preclinical studies have shown that ATP facilitates the proliferation, migration, and invasion of GC cells by engaging the P2X7 receptor. Both ATP and its analog BzATP increase intracellular calcium levels, promote cytoskeletal reorganization, and enhance cell survival in vitro. Conversely, pharmacological blockade of P2X7R with antagonists such as A438079 or AZD9056 reduces these effects, suggesting potential therapeutic value in experimental models[159]. The involvement of ATP in the P2 purinergic signaling network within GC cells plays a crucial role in modulating tumor progression, particularly by fostering tumor cell proliferation and invasion[155]. Moreover, the ATP-P2X7R axis has been implicated in both oncogenesis and cancer-associated pain, underscoring its significance as a potential therapeutic target[160]. Beyond its direct effects, ATP has been found to act in synergy with NE to drive GC progression. This cooperative interaction enhances the invasive potential of GC cells by promoting EMT, further emphasizing the complexity of ATP-mediated oncogenic mechanisms[161] (Figure 3).

This study comprehensively reviews the regulatory roles of diverse neurotransmitters in GC initiation and progression, proposing an innovative therapeutic approach that targets specific receptor agonists or antagonists based on prior research findings. Monoaminergic neurotransmitters, such as NE and DA, have been shown to markedly drive the aggressive phenotypes of GC cells—including enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion, and neovascularization—primarily through activation of key signaling cascades like the β-adrenergic receptor pathway. It is worth noting that most neurotransmitters exhibit environment-dependent effects. For example, although DA typically suppresses GC via D2R, studies indicate that excessively high DA concentrations in vivo can also impair Teffs through D1R, leading to immunosuppression. This reflects the contradictory effects of neurotransmitters on GC under different conditions. Within the serotonergic system, HTR2B receptor engagement stimulates GC cell growth via downstream mediators such as the PI3K and MAPK pathways. Conversely, the roles of other 5-HT receptor subtypes remain poorly characterized and demand comprehensive evaluation in gastric malignancy. Despite increasing attention to the influence of the HPA axis in cancer biology, the precise contribution of this stress-responsive endocrine axis—particularly its key mediators such as E—within the gastric TME remains largely unexplored. In terms of cholinergic regulation, ACh facilitates oncogenic processes through both mAChR and nAChR receptors, yet the molecular interplay between these receptor classes within a single gastric tumor subtype has not been mechanistically dissected. GABAergic signaling is implicated in gastric tumorigenesis through the elevated expression of GABA-A and GABA-B receptors, which potentiate tumor progression via activation of mTOR signaling; however, head-to-head comparisons of antagonists targeting these receptors are still lacking. Although increased levels of SP and NPY have been detected in gastric carcinoma cells, detailed mechanistic understanding of their functional roles remains in its infancy. ADO receptor A2B is notably overexpressed in GC tissues, and ADO itself has been implicated in promoting resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Moreover, ATP-mediated stimulation of P2X7 receptors drives tumor cell proliferation, motility, and invasiveness, yet differential and potentially synergistic effects of ATP in its capacity as an exogenous metabolite vs a neurotransmitter have yet to be delineated. The dynamic crosstalk between neural signaling molecules and the TME is emerging as a critical axis in GC research. Dissecting the complex regulatory networks governed by distinct neurotransmitter systems in gastric tumors will not only deepen our molecular understanding of gastric carcinogenesis, but also pave the way for novel biomarker discovery based on neurotransmitter-receptor expression profiles. Targeted therapeutic interventions utilizing receptor-specific agonists or antagonists may offer promising avenues for treatment. Furthermore, neurotransmitter-modulating strategies have the potential to synergize with immune checkpoint inhibitors to overcome therapeutic resistance. Unraveling the integrative signaling logic and inter-receptor communication among these neuromodulatory systems may guide the development of rational combinatorial regimens. Ultimately, precision-targeted modulation of neurotransmitter receptors could serve as a transformative approach in the personalized management of GC, offering new hope for improved survival outcomes.

| 1. | Sundar R, Nakayama I, Markar SR, Shitara K, van Laarhoven HWM, Janjigian YY, Smyth EC. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2025;405:2087-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Zheng RS, Chen R, Han BF, Wang SM, Li L, Sun KX, Zeng HM, Wei WW, He J. [Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2024;46:221-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zahalka AH, Frenette PS. Nerves in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:143-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mehedințeanu AM, Sfredel V, Stovicek PO, Schenker M, Târtea GC, Istrătoaie O, Ciurea AM, Vere CC. Assessment of Epinephrine and Norepinephrine in Gastric Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zahalka AH, Arnal-Estapé A, Maryanovich M, Nakahara F, Cruz CD, Finley LWS, Frenette PS. Adrenergic nerves activate an angio-metabolic switch in prostate cancer. Science. 2017;358:321-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Qi YH, Yang LZ, Zhou L, Gao LJ, Hou JY, Yan Z, Bi XG, Yan CP, Wang DP, Cao JM. Sympathetic nerve infiltration promotes stomach adenocarcinoma progression via norepinephrine/β2-adrenoceptor/YKL-40 signaling pathway. Heliyon. 2022;8:e12468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cole SW, Sood AK. Molecular pathways: beta-adrenergic signaling in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1201-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shi M, Liu D, Duan H, Han C, Wei B, Qian L, Chen C, Guo L, Hu M, Yu M, Song L, Shen B, Guo N. Catecholamine up-regulates MMP-7 expression by activating AP-1 and STAT3 in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin C, He H, Liu H, Li R, Chen Y, Qi Y, Jiang Q, Chen L, Zhang P, Zhang H, Li H, Zhang W, Sun Y, Xu J. Tumour-associated macrophages-derived CXCL8 determines immune evasion through autonomous PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer. Gut. 2019;68:1764-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yong J, Li Y, Lin S, Wang Z, Xu Y. Inhibitors Targeting YAP in Gastric Cancer: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:2445-2456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He Z, Xu Y, Rao Z, Zhang Z, Zhou J, Zhou T, Wang H. The role of α7-nAChR-mediated PI3K/AKT pathway in lung cancer induced by nicotine. Sci Total Environ. 2024;912:169604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3099] [Cited by in RCA: 4283] [Article Influence: 428.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eddy K, Eddin MN, Fateeva A, Pompili SVB, Shah R, Doshi S, Chen S. Implications of a Neuronal Receptor Family, Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors, in Cancer Development and Progression. Cells. 2022;11:2857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shi L, Yang L, Wu Z, Xu W, Song J, Guan W. Adenosine signaling: Next checkpoint for gastric cancer immunotherapy? Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;63:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dawoud MM, Abdelaziz KK, Alhanafy AM, Ali MSE, Elkhouly EAB. Clinical Significance of Immunohistochemical Expression of Neuropeptide Y1 Receptor in Patients With Breast Cancer in Egypt. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2021;29:277-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pu J, Zhang X, Luo H, Xu L, Lu X, Lu J. Adrenaline promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via HuR-TGFβ regulatory axis in pancreatic cancer cells and the implication in cancer prognosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493:1273-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang H, Xia L, Chen J, Zhang S, Martin V, Li Q, Lin S, Chen J, Calmette J, Lu M, Fu L, Yang J, Pan Z, Yu K, He J, Morand E, Schlecht-Louf G, Krzysiek R, Zitvogel L, Kang B, Zhang Z, Leader A, Zhou P, Lanfumey L, Shi M, Kroemer G, Ma Y. Stress-glucocorticoid-TSC22D3 axis compromises therapy-induced antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2019;25:1428-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang X, Zhang Y, He Z, Yin K, Li B, Zhang L, Xu Z. Chronic stress promotes gastric cancer progression and metastasis: an essential role for ADRB2. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Sethi NS, Kikuchi O, Duronio GN, Stachler MD, McFarland JM, Ferrer-Luna R, Zhang Y, Bao C, Bronson R, Patil D, Sanchez-Vega F, Liu JB, Sicinska E, Lazaro JB, Ligon KL, Beroukhim R, Bass AJ. Early TP53 alterations engage environmental exposures to promote gastric premalignancy in an integrative mouse model. Nat Genet. 2020;52:219-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhi X, Li B, Li Z, Zhang J, Yu J, Zhang L, Xu Z. Adrenergic modulation of AMPKdependent autophagy by chronic stress enhances cell proliferation and survival in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2019;54:1625-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ogden SR, Wroblewski LE, Weydig C, Romero-Gallo J, O'Brien DP, Israel DA, Krishna US, Fingleton B, Reynolds AB, Wessler S, Peek RM Jr. p120 and Kaiso regulate Helicobacter pylori-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4110-4121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pan C, Wu J, Zheng S, Sun H, Fang Y, Huang Z, Shi M, Liang L, Bin J, Liao Y, Chen J, Liao W. Depression accelerates gastric cancer invasion and metastasis by inducing a neuroendocrine phenotype via the catecholamine/β(2) -AR/MACC1 axis. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:1049-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Thaker PH, Han LY, Kamat AA, Arevalo JM, Takahashi R, Lu C, Jennings NB, Armaiz-Pena G, Bankson JA, Ravoori M, Merritt WM, Lin YG, Mangala LS, Kim TJ, Coleman RL, Landen CN, Li Y, Felix E, Sanguino AM, Newman RA, Lloyd M, Gershenson DM, Kundra V, Lopez-Berestein G, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Sood AK. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med. 2006;12:939-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 875] [Cited by in RCA: 990] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhou SJ, Deng YL, Liang HF, Jaoude JC, Liu FY. Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes CREB-mediated activation of miR-3188 and Notch signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1577-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shen J, Li M, Min L. HSPB8 promotes cancer cell growth by activating the ERKCREB pathway and is indicative of a poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:2978-2986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hara MR, Kovacs JJ, Whalen EJ, Rajagopal S, Strachan RT, Grant W, Towers AJ, Williams B, Lam CM, Xiao K, Shenoy SK, Gregory SG, Ahn S, Duckett DR, Lefkowitz RJ. A stress response pathway regulates DNA damage through β2-adrenoreceptors and β-arrestin-1. Nature. 2011;477:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lu YJ, Geng ZJ, Sun XY, Li YH, Fu XB, Zhao XY, Wei B. Isoprenaline induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;408:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wei B, Sun X, Geng Z, Shi M, Chen Z, Chen L, Wang Y, Fu X. Isoproterenol regulates CD44 expression in gastric cancer cells through STAT3/MicroRNA373 cascade. Biomaterials. 2016;105:89-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang Y, Wang S, Yang Q, Li J, Yu F, Zhao E. Norepinephrine Enhances Aerobic Glycolysis and May Act as a Predictive Factor for Immunotherapy in Gastric Cancer. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:5580672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brak HH, Thielman NRJ. Norepinephrine mediates adrenergic receptor transcription and oncogenic gene expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Adv Biol Regul. 2025;97:101097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang Y, Wang X, Wang K, Qi J, Zhang Y, Wang X, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Gu L, Yu R, Zhou X. Chronic stress accelerates glioblastoma progression via DRD2/ERK/β-catenin axis and Dopamine/ERK/TH positive feedback loop. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ganguly S, Basu B, Shome S, Jadhav T, Roy S, Majumdar J, Dasgupta PS, Basu S. Dopamine, by acting through its D2 receptor, inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I)-induced gastric cancer cell proliferation via up-regulation of Krüppel-like factor 4 through down-regulation of IGF-IR and AKT phosphorylation. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2701-2707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Al-Jahmany AA, Schultheiss G, Diener M. Effects of dopamine on ion transport across the rat distal colon. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:605-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pivonello R, Ferone D, Lombardi G, Colao A, Lamberts SWJ, Hofland LJ. Novel insights in dopamine receptor physiology. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156 Suppl 1:S13-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Feng XY, Yan JT, Li GW, Liu JH, Fan RF, Li SC, Zheng LF, Zhang Y, Zhu JX. Source of dopamine in gastric juice and luminal dopamine-induced duodenal bicarbonate secretion via apical dopamine D(2) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:3258-3272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Huang H, Wu K, Ma J, Du Y, Cao C, Nie Y. Dopamine D2 receptor suppresses gastric cancer cell invasion and migration via inhibition of EGFR/AKT/MMP-13 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;39:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mukherjee K, Peng D, Brifkani Z, Belkhiri A, Pera M, Koyama T, Koehler EA, Revetta FL, Washington MK, El-Rifai W. Dopamine and cAMP regulated phosphoprotein MW 32 kDa is overexpressed in early stages of gastric tumorigenesis. Surgery. 2010;148:354-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhu S, Soutto M, Chen Z, Blanca Piazuelo M, Kay Washington M, Belkhiri A, Zaika A, Peng D, El-Rifai W. Activation of IGF1R by DARPP-32 promotes STAT3 signaling in gastric cancer cells. Oncogene. 2019;38:5805-5816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chakroborty D, Sarkar C, Basu B, Dasgupta PS, Basu S. Catecholamines regulate tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3727-3730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chauvet N, Romanò N, Lafont C, Guillou A, Galibert E, Bonnefont X, Le Tissier P, Fedele M, Fusco A, Mollard P, Coutry N. Complementary actions of dopamine D2 receptor agonist and anti-vegf therapy on tumoral vessel normalization in a transgenic mouse model. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2150-2161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Qin T, Wang C, Chen X, Duan C, Zhang X, Zhang J, Chai H, Tang T, Chen H, Yue J, Li Y, Yang J. Dopamine induces growth inhibition and vascular normalization through reprogramming M2-polarized macrophages in rat C6 glioma. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:112-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhang X, Liu Q, Liao Q, Zhao Y. Potential Roles of Peripheral Dopamine in Tumor Immunity. J Cancer. 2017;8:2966-2973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Liu S, Cui M, Zang J, Wang J, Shi X, Qian F, Xu S, Jing R. SLC6A3 as a potential circulating biomarker for gastric cancer detection and progression monitoring. Pathol Res Pract. 2021;221:153446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kumar V, Sethi B, Staller DW, Shrestha P, Mahato RI. Gemcitabine elaidate and ONC201 combination therapy for inhibiting pancreatic cancer in a KRAS mutated syngeneic mouse model. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10:158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ye D, Xu H, Tang Q, Xia H, Zhang C, Bi F. The role of 5-HT metabolism in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1876:188618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bohl B, Lei Y, Bewick GA, Hashemi P. Measurement of Real-Time Serotonin Dynamics from Human-Derived Gut Organoids. Anal Chem. 2025;97:5057-5065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Dizeyi N, Hedlund P, Bjartell A, Tinzl M, Austild-Taskén K, Abrahamsson PA. Serotonin activates MAP kinase and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways in prostate cancer cell lines. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:436-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Fabà L, de Groot N, Ramis G, Cabrera-Gómez CG, Doelman J. Serotonin receptors and their association with the immune system in the gastrointestinal tract of weaning piglets. Porcine Health Manag. 2022;8:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Sumara G, Sumara O, Kim JK, Karsenty G. Gut-derived serotonin is a multifunctional determinant to fasting adaptation. Cell Metab. 2012;16:588-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ashbury JE, Lévesque LE, Beck PA, Aronson KJ. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Antidepressants, Prolactin and Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Busby J, Mills K, Zhang SD, Liberante FG, Cardwell CR. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and breast cancer survival: a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Gurbuz N, Ashour AA, Alpay SN, Ozpolat B. Down-regulation of 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors inhibits proliferation, clonogenicity and invasion of human pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Tu RH, Wu SZ, Huang ZN, Zhong Q, Ye YH, Zheng CH, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Chen QY, Huang CM, Lin M, Lu J, Cao LL, Li P. Neurotransmitter Receptor HTR2B Regulates Lipid Metabolism to Inhibit Ferroptosis in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83:3868-3885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Liu Y, Pei Z, Pan T, Wang H, Chen W, Lu W. Indole metabolites and colorectal cancer: Gut microbial tryptophan metabolism, host gut microbiome biomarkers, and potential intervention mechanisms. Microbiol Res. 2023;272:127392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | de las Casas-Engel M, Domínguez-Soto A, Sierra-Filardi E, Bragado R, Nieto C, Puig-Kroger A, Samaniego R, Loza M, Corcuera MT, Gómez-Aguado F, Bustos M, Sánchez-Mateos P, Corbí AL. Serotonin skews human macrophage polarization through HTR2B and HTR7. J Immunol. 2013;190:2301-2310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jin X, Li H, Li B, Zhang C, He Y. Knockdown and inhibition of hydroxytryptamine receptor 1D suppress proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;620:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Schubert ML. Physiologic, pathophysiologic, and pharmacologic regulation of gastric acid secretion. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:430-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kondo T, Nakajima M, Teraoka H, Unno T, Komori S, Yamada M, Kitazawa T. Muscarinic receptor subtypes involved in regulation of colonic motility in mice: functional studies using muscarinic receptor-deficient mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Goswami C, Tanaka T, Jogahara T, Sakai T, Sakata I. Motilin stimulates pepsinogen secretion in Suncus murinus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;462:263-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Holzer P. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels as drug targets for diseases of the digestive system. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:142-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Dong WY, Zhu X, Tang HD, Huang JY, Zhu MY, Cheng PK, Wang H, Wang XY, Wang H, Mao Y, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Tao WJ, Zhang Z. Brain regulation of gastric dysfunction induced by stress. Nat Metab. 2023;5:1494-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Yu H, Xia H, Tang Q, Xu H, Wei G, Chen Y, Dai X, Gong Q, Bi F. Acetylcholine acts through M3 muscarinic receptor to activate the EGFR signaling and promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Wang L, Zhi X, Zhang Q, Wei S, Li Z, Zhou J, Jiang J, Zhu Y, Yang L, Xu H, Xu Z. Muscarinic receptor M3 mediates cell proliferation induced by acetylcholine and contributes to apoptosis in gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:2105-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Gong Z, Zhang X, Liu M, Jin C, Hu Y. Visualizing agonist-induced M2 receptor activation regulated by aromatic ring dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025;122:e2418559122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Kruse AC, Kobilka BK, Gautam D, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Wess J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: novel opportunities for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:549-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Hayakawa Y, Sakitani K, Konishi M, Asfaha S, Niikura R, Tomita H, Renz BW, Tailor Y, Macchini M, Middelhoff M, Jiang Z, Tanaka T, Dubeykovskaya ZA, Kim W, Chen X, Urbanska AM, Nagar K, Westphalen CB, Quante M, Lin CS, Gershon MD, Hara A, Zhao CM, Chen D, Worthley DL, Koike K, Wang TC. Nerve Growth Factor Promotes Gastric Tumorigenesis through Aberrant Cholinergic Signaling. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:21-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 67. | Kuol N, Davidson M, Karakkat J, Filippone RT, Veale M, Luwor R, Fraser S, Apostolopoulos V, Nurgali K. Blocking Muscarinic Receptor 3 Attenuates Tumor Growth and Decreases Immunosuppressive and Cholinergic Markers in an Orthotopic Mouse Model of Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Zhi X, Wu F, Qian J, Ochiai Y, Lian G, Malagola E, Zheng B, Tu R, Zeng Y, Kobayashi H, Xia Z, Wang R, Peng Y, Shi Q, Chen D, Ryeom SW, Wang TC. Nociceptive neurons promote gastric tumour progression via a CGRP-RAMP1 axis. Nature. 2025;640:802-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zhao CM, Hayakawa Y, Kodama Y, Muthupalani S, Westphalen CB, Andersen GT, Flatberg A, Johannessen H, Friedman RA, Renz BW, Sandvik AK, Beisvag V, Tomita H, Hara A, Quante M, Li Z, Gershon MD, Kaneko K, Fox JG, Wang TC, Chen D. Denervation suppresses gastric tumorigenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:250ra115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Su Z, Song J, Wang Z, Zhou L, Xia Y, Yu S, Sun Q, Liu SS, Zhao L, Li S, Wei L, Carson DA, Lu D. Tumor promoter TPA activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in a casein kinase 1-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E7522-E7531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Takahashi T, Ohnishi H, Sugiura Y, Honda K, Suematsu M, Kawasaki T, Deguchi T, Fujii T, Orihashi K, Hippo Y, Watanabe T, Yamagaki T, Yuba S. Non-neuronal acetylcholine as an endogenous regulator of proliferation and differentiation of Lgr5-positive stem cells in mice. FEBS J. 2014;281:4672-4690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Zhou H, Li G, Huang S, Feng Y, Zhou A. SOX9 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway in gastric carcinoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Kuol N, Godlewski J, Kmiec Z, Vogrin S, Fraser S, Apostolopoulos V, Nurgali K. Cholinergic signaling influences the expression of immune checkpoint inhibitors, PD-L1 and PD-L2, and tumor hallmarks in human colorectal cancer tissues and cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Grando SA. Connections of nicotine to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:419-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Shin VY, Wu WK, Ye YN, So WH, Koo MW, Liu ES, Luo JC, Cho CH. Nicotine promotes gastric tumor growth and neovascularization by activating extracellular signal-regulated kinase and cyclooxygenase-2. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2487-2495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Papapostolou I, Ross-Kaschitza D, Bochen F, Peinelt C, Maldifassi MC. Contribution of the α5 nAChR Subunit and α5SNP to Nicotine-Induced Proliferation and Migration of Human Cancer Cells. Cells. 2023;12:2000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Jia Y, Sun H, Wu H, Zhang H, Zhang X, Xiao D, Ma X, Wang Y. Nicotine Inhibits Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis via Regulating α5-nAChR/AKT Signaling in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Shin VY, Jin HC, Ng EK, Sung JJ, Chu KM, Cho CH. Activation of 5-lipoxygenase is required for nicotine mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor cell growth. Cancer Lett. 2010;292:237-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Yang LH, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani K, Lin X, Levi J, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Czura CJ, Larosa GJ, Miller EJ, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y. Selective alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves survival in murine endotoxemia and severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1139-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Mugisha S, Baba SA, Labhsetwar S, Dave D, Zakeri A, Klemke R, Desgrosellier JS. S100A8/A9 innate immune signaling as a distinct mechanism driving progression of smoking-related breast cancers. Oncogene. 2025;44:1051-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Neves Cruz J, Santana de Oliveira M, Gomes Silva S, Pedro da Silva Souza Filho A, Santiago Pereira D, Lima E Lima AH, de Aguiar Andrade EH. Insight into the Interaction Mechanism of Nicotine, NNK, and NNN with Cytochrome P450 2A13 Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60:766-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Mashimo M, Fujii T, Ono S, Moriwaki Y, Misawa H, Azami T, Kasahara T, Kawashima K. GTS-21 Enhances Regulatory T Cell Development from T Cell Receptor-Activated Human CD4(+) T Cells Exhibiting Varied Levels of CHRNA7 and CHRFAM7A Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:12257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Wang W, Chin-Sheng H, Kuo LJ, Wei PL, Lien YC, Lin FY, Liu HH, Ho YS, Wu CH, Chang YJ. NNK enhances cell migration through α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor accompanied by increased of fibronectin expression in gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19 Suppl 3:S580-S588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Shin VY, Jin HC, Ng EK, Yu J, Leung WK, Cho CH, Sung JJ. Nicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone induce cyclooxygenase-2 activity in human gastric cancer cells: Involvement of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) and beta-adrenergic receptor signaling pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;233:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Wong HP, Yu L, Lam EK, Tai EK, Wu WK, Cho CH. Nicotine promotes colon tumor growth and angiogenesis through beta-adrenergic activation. Toxicol Sci. 2007;97:279-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Shin VY, Wu WK, Chu KM, Wong HP, Lam EK, Tai EK, Koo MW, Cho CH. Nicotine induces cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in association with tumor-associated invasion and angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:607-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Shin VY, Wu WK, Chu KM, Koo MW, Wong HP, Lam EK, Tai EK, Cho CH. Functional role of beta-adrenergic receptors in the mitogenic action of nicotine on gastric cancer cells. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Lian S, Li S, Zhu J, Xia Y, Do Jung Y. Nicotine stimulates IL-8 expression via ROS/NF-κB and ROS/MAPK/AP-1 axis in human gastric cancer cells. Toxicology. 2022;466:153062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Tu CC, Huang CY, Cheng WL, Hung CS, Uyanga B, Wei PL, Chang YJ. The α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mediates the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to taxanes. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:4421-4428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Chen WY, Huang CY, Cheng WL, Hung CS, Huang MT, Tai CJ, Liu YN, Chen CL, Chang YJ. Alpha 7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mediates the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9537-9544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Tu CC, Huang CY, Cheng WL, Hung CS, Chang YJ, Wei PL. Silencing A7-nAChR levels increases the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to ixabepilone treatment. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:9493-9501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Burrin DG, Stoll B. Metabolic fate and function of dietary glutamate in the gut. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:850S-856S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Pfragner R, Eick GN, Champaneria MC. The functional characterization of normal and neoplastic human enterochromaffin cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2340-2348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Jiang Y, Tao Q, Qiao X, Yang Y, Peng C, Han M, Dong K, Zhang W, Xu M, Wang D, Zhu W, Li X. Targeting amino acid metabolism to inhibit gastric cancer progression and promote anti-tumor immunity: a review. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1508730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Fu J, Ni Y, Hu Y, Tang W, Fu J, Wang Y, Yu S, Xu W. Glutamine, Serine and Glycine at Increasing Concentrations Regulate Cisplatin Sensitivity in Gastric Cancer by Posttranslational Modifications of KDM4A. Mol Carcinog. 2025;64:703-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Zhang C, Yuan XR, Li HY, Zhao ZJ, Liao YW, Wang XY, Su J, Sang SS, Liu Q. Anti-cancer effect of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 inhibition in human glioma U87 cells: involvement of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:419-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Shaye H, Stauch B, Gati C, Cherezov V. Molecular mechanisms of metabotropic GABA(B) receptor function. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabg3362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Hansen KB, Wollmuth LP, Bowie D, Furukawa H, Menniti FS, Sobolevsky AI, Swanson GT, Swanger SA, Greger IH, Nakagawa T, McBain CJ, Jayaraman V, Low CM, Dell'Acqua ML, Diamond JS, Camp CR, Perszyk RE, Yuan H, Traynelis SF. Structure, Function, and Pharmacology of Glutamate Receptor Ion Channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:298-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 99.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Martinez de Morentin PB, Gonzalez JA, Dowsett GKC, Martynova Y, Yeo GSH, Sylantyev S, Heisler LK. A brainstem to hypothalamic arcuate nucleus GABAergic circuit drives feeding. Curr Biol. 2024;34:1646-1656.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Liu J, Zhang P, Zheng Z, Afridi MI, Zhang S, Wan Z, Zhang X, Stingelin L, Wang Y, Tu H. GABAergic signaling between enteric neurons and intestinal smooth muscle promotes innate immunity and gut defense in Caenorhabditis elegans. Immunity. 2023;56:1515-1532.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Cruz MT, Dezfuli G, Murphy EC, Vicini S, Sahibzada N, Gillis RA. GABA(B) Receptor Signaling in the Dorsal Motor Nucleus of the Vagus Stimulates Gastric Motility via a Cholinergic Pathway. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Matuszek M, Jesipowicz M, Kleinrok Z. GABA content and GAD activity in gastric cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:377-381. [PubMed] |

| 103. | Huang D, Wang Y, Thompson JW, Yin T, Alexander PB, Qin D, Mudgal P, Wu H, Liang Y, Tan L, Pan C, Yuan L, Wan Y, Li QJ, Wang XF. Cancer-cell-derived GABA promotes β-catenin-mediated tumour growth and immunosuppression. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:230-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Maemura K, Shiraishi N, Sakagami K, Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, Watanabe M, Otsuki Y. Proliferative effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid on the gastric cancer cell line are associated with extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:688-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Sawaki K, Kanda M, Kodera Y. ASO Author Reflections: Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Subunit Delta as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:637-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Zhou X, Chen Z, Yu Y, Li M, Cao Y, Prochownik EV, Li Y. Increases in 4-Acetaminobutyric Acid Generated by Phosphomevalonate Kinase Suppress CD8(+) T Cell Activation and Allow Tumor Immune Escape. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2403629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Leng W, Ye J, Wen Z, Wang H, Zhu Z, Song X, Liu K. GABRD Accelerates Tumour Progression via Regulating CCND1 Signalling Pathway in Gastric Cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2025;29:e70485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |