Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.113650

Revised: October 10, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 89 Days and 16.1 Hours

Bacterial contamination during colonoscopy is a significant concern, yet few studies have evaluated bacterial aerosols. This study aimed to determine whether covering the biopsy hole check valve with enzymolysis gauze (refers to sterile gauze soaked in a multi-enzyme cleaning solution) reduces bacterial air pollution in endoscopy rooms.

To evaluate the efficacy of an enzymolysis gauze cover in reducing bacterial aerosols from the biopsy valve.

This prospective, single-blind trial included 80 patients undergoing elective diagnostic colonoscopy. During the procedure, the biopsy hole check valve was either covered or left uncovered with enzymolysis gauze. Air samples (100 L) were collected at a distance of 30 cm from the biopsy hole check valve and approximately 140 cm above the floor using a percussive air sampling instrument. Gram-positive bacteria were cultured on standard 90 mm colimycin nalidixic agar blood plates. The primary outcome measures were bacterial load and species identification.

Covering the biopsy hole check valve with enzymolysis gauze reduced bacterial load near the check valve from 50 colony-forming unit (CFU)/m3 [interquartile range (IQR): 30-80] to 20 CFU/m3 (IQR: 10-20). At the end of the procedure each day, covering the valve also decreased bacterial load in the endoscopy room from 35 CFU/m3 (IQR: 33-85) to 10 CFU/m3 (IQR: 5-10). The predominant bacteria identified were Gram-positive cocci.

Applying enzymolysis gauze to cover the biopsy hole check valve significantly reduces bacterial aerosol contamination in endoscopy rooms during colonoscopy.

Core Tip: Endoscopy-related infections are underestimated due to difficulties in diagnosis, misdiagnosis, and underreporting. Bacterial contamination during colonoscopy poses a significant challenge, yet limited research has focused on bacterial aerosols, particularly those originating from the biopsy valve. This study introduces a simple yet effective approach to mitigate bacterial aerosol contamination in the endoscopy room. Our findings demonstrate that covering the biopsy valve with an enzymolysis gauze during colonoscopy significantly reduces airborne bacterial aerosols. This could improve safety for both patients and healthcare personnel.

- Citation: Xia HB, Hou YD, Zhang Y, Yu AY, Ding Q, Ruan WL, Mao YS, Feng SJ, Ding C, Zhou YF. Covering the biopsy hole check valve with “enzymolysis gauze” reduces bacterial contamination in the endoscopy room. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(44): 113650

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i44/113650.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.113650

The human colon harbors a diverse microbial community, with bacterial concentrations reaching up to 1012 colony-forming units (CFUs) per gram of stool[1]. Due to the invasive nature and open design of endoscopic diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, endoscopy centers have become critical sites for bacterial aerosol generation[2]. Aerosols can be produced during various endoscopic maneuvers, including suction, flushing, and gas insufflation[3,4]. Additionally, patient exhaust and defecation during procedures contribute to significant bacterial aerosolization. However, research on air contamination in endoscopy rooms and strategies to mitigate fecal bacterial dispersion remains limited.

Transendoscopic biopsy channels are recognized as a significant risk factor for device-associated infections[5,6]. Studies have shown that biopsy forceps removal through the biopsy hole releases a substantial bacterial load[7]. These aerosols not only pose infection risks to healthcare workers but may also contribute to cross-infection among patients[8,9]. Johnston et al[10] reported that endoscopic personnel are at high risk of bioaerosol exposure, which can be transmitted through mucosal pathways such as the eyes, nose, and mouth. Therefore, reducing bacterial aerosol dispersion during colonoscopy is of paramount importance. Previous research by Vavricka et al[7] suggested that negative pressure as

This study was conducted at the Endoscopy Center and received ethical approval from Hangzhou First People’s Hospital (Approval No. 2025ZN007-1). Prospective registration of this study was completed in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (No. ChiCTR2500097549, https://www.chictr.org.cn/) on February 20, 2025.

All patients provided written informed consent before participation. Air samples were collected over several months during elective diagnostic colonoscopies. The endoscopy suite maintained an air exchange rate of 12 times per hour. All procedures were performed in the same endoscopy suite. The sample size of 80 (40 per group) was justified by a power analysis using pilot data. Assuming a 50% reduction in bacterial load, the analysis (α = 0.05, β = 0.20) indicated a minimum of 76 patients was required to detect this effect, leading us to enroll 80 participants: (1) Inclusion criteria: Patients aged 18-90 years with good bowel preparation quality (minimal or no fecal residue) undergoing diagnostic colonoscopy without therapeutic interventions (i.e., no polypectomy, hemostasis, or stent placement) were included; and (2) Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they declined participation, had incomplete access to the ileocecal area, required therapeutic intervention, or were undergoing emergency procedures.

Collected data included patient name, anonymous identification number, age, sex, colonoscopy indication, procedure date and time, bowel preparation method, and bowel preparation quality score (Boston Bowel Preparation Scale, BBPS). Patients were randomly assigned to the control group (biopsy hole check valve uncovered) or the experimental group (biopsy hole covered with enzymolysis gauze) using a random number table. A random number table determined the group assignment (control or experimental) for each day, with all patients enrolled on that day allocated accordingly. All patients on a given day were assigned to the same group, thus precluding any crossover of groups within a single day.

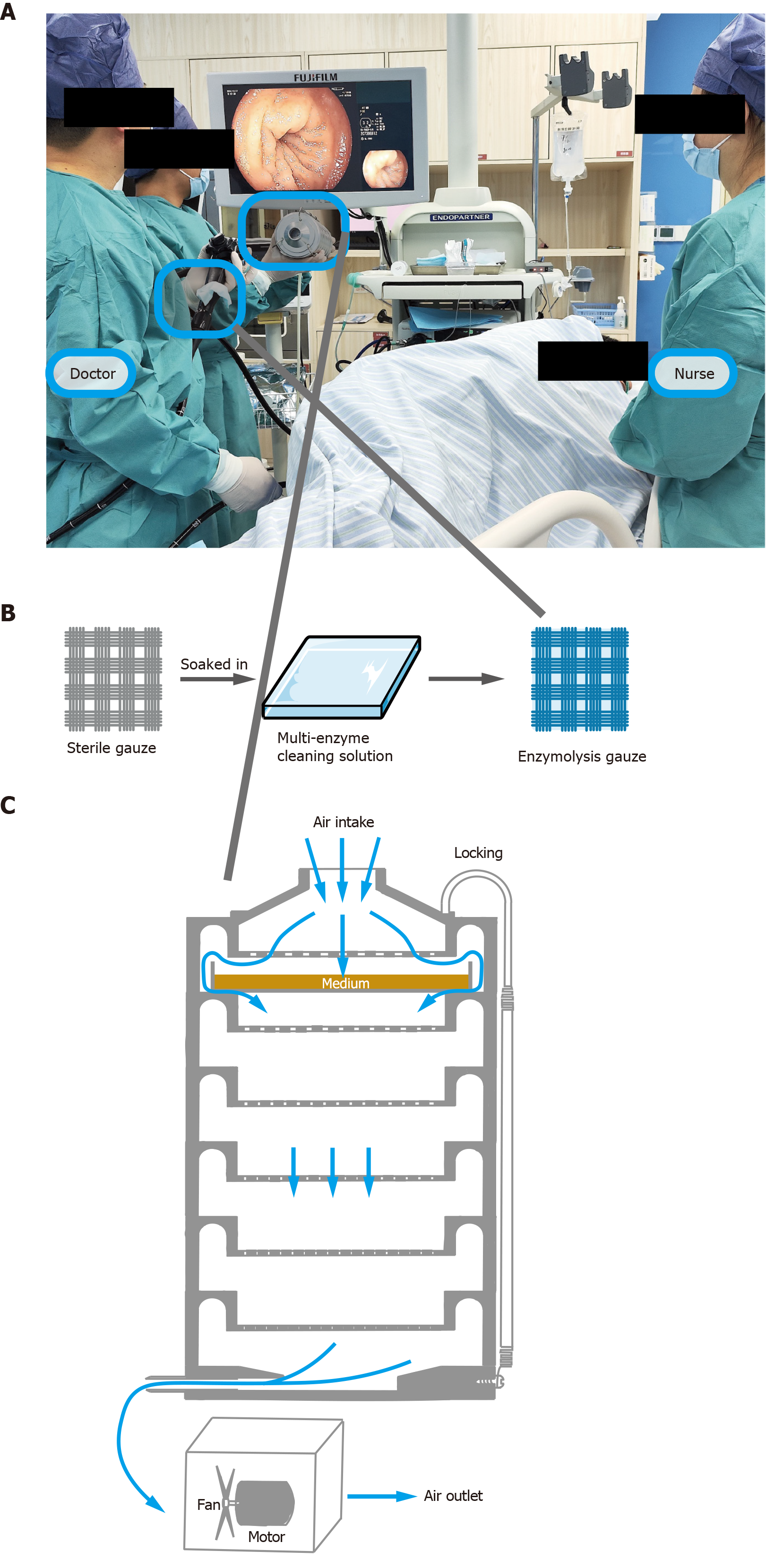

Patients were placed in the left lateral position (Figure 1A) and sedated with propofol. All colonoscopies were performed by physicians with over 10 years of endoscopy experience, who were familiar with the study protocol. “Enzymolysis gauze” refers to sterile gauze soaked in a multi-enzyme cleaning solution (Mulliken Technology Limited, MO, United States) (Figure 1B). New biopsy valve plugs were used for each procedure. In the experimental group, an enzymolysis gauze was securely placed over the biopsy hole check valve using elastic cords to prevent dislodgment. Air sampling was performed for each patient during both the insertion and withdrawal phases, collecting 50 L per phase, for a total of 100 L per procedure. During the insertion phase, air was sampled as the endoscope advanced from the anal opening to the cecum or appendix opening. During the withdrawal phase, air was sampled as the endoscope was withdrawn from the cecum or appendix opening to the anal opening. After sampling, sterilized instruments were used for each collection. The air sampler was disinfected by immersion in 75% alcohol, with subsequent sampling performed only after complete alcohol evaporation. Endoscopes (FUJIFILM, Japan) were disinfected using an automatic endoscope washer-disinfectant (Steelco, Italy). Each endoscopy room conducts 5-10 procedures daily.

Various air sampling devices can be used to assess air quality in endoscopy rooms, with impactors being the most commonly used in hospital settings. This study employed the Anderson six-stage impact microorganism sampler (Figure 1C), the most frequently used device in our facility for hospital air sampling[11,12]. The Anderson sampler directs air through a perforated screen plate onto an agar plate. The suction mechanism forces airborne particles onto the agar surface, where microorganisms are cultured. In this study, only the first layer of the sampler contained an agar plate. Sampling flow was calibrated to 28.3 L/minute, per manufacturer guidelines. The airborne bacterial load was calculated as colony-forming units per cubic meter (CFU/m3) using the following formula: CFU/m3 = Q1/(28.3 L/minute × t) × 1000, where Q1 represents the number of colonies on the agar plate, and t is the sampling time (minutes).

Air samples were collected every morning (before procedures, at 8:00 AM) and every evening (30 minutes after the final procedure of the day). The sampler was placed at the center of the endoscopy room, at a height of 1.4 m, corresponding to the position of the endoscopist during procedures. During colonoscopy, air sampling was conducted at 28.3 L/minute, 30 cm from the biopsy hole check valve. Sampling was performed in two 106-second periods: One 50 L sample during the insertion phase and another 50 L sample during the withdrawal phase.

Standard 90-mm Petri dishes containing a selective medium for Gram-positive cocci (Columbia colistin-nalidixic acid agar blood agar, supplemented with polymyxin B and nalidixic acid as bacteriostatic agents; HKM, Guangdong, China) were used with the impaction sampler. Following air sampling, colistin-nalidixic acid agar blood plates were incubated at 35 °C in a 5% carbon dioxide environment for 72 hours. The number of bacterial colonies was then counted and converted to CFU/m3. Bacterial species were identified using mass spectrometry (Microflex LT/SH, Bruker, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Gram-positive bacteria were primarily cultured, as they are a major source of hospital-acquired infections. Gram-negative bacteria were not quantified due to their high abundance, which could interfere with colony counting. The outcome indicators of the study include bacterial colony counts and bacterial species.

Since airborne microbial data followed a non-normal distribution, the median was used to represent bacterial concentrations. Maximum and minimum values were recorded to reflect sample variability. The Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare differences between two independent groups. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for paired samples. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance was employed to assess differences among three or more groups. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 98 patients were screened. Eighteen patients were excluded due to undergoing therapeutic procedures (e.g., polyp removal). The remaining 80 patients underwent colonoscopy after bowel preparation with sodium phosphate powder. The most common indications for colonoscopy were screening (53.75%), abdominal pain (20%), hematochezia (10%), diarrhea (5%), bloating (6.25%), irregular stool (3.75%), and elevated tumor markers (1.25%). Patients were randomly assigned to either the control group (biopsy hole check valve uncovered) or the experimental group (biopsy hole covered with enzymolysis gauze), with 40 patients in each group. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between the control (mean age: 56.80 ± 13.01 years; body mass index: 24.21 ± 2.44; BBPS: 7.30 ± 1.04) and experimental groups (mean age: 58.93 ± 12.66 years; body mass index: 23.56 ± 2.35 kg/m2; BBPS: 7.35 ± 1.17) (Table 1).

| Control group, n = 40 | Experimental group, n = 40 | P value | |

| Sex | > 0.05 | ||

| Men | 20 | 19 | |

| Women | 20 | 21 | |

| Age (years) | 56.80 ± 13.01 | 58.93 ± 12.66 | > 0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.21 ± 2.44 | 23.56 ± 2.35 | > 0.05 |

| BBPS | > 0.05 | ||

| Right | 2.25 ± 0.71 | 2.18 ± 0.71 | |

| Transverse | 2.48 ± 0.56 | 2.35 ± 0.58 | |

| Left | 2.58 ± 0.51 | 2.80 ± 0.41 | |

| Total BBPS | 7.30 ± 1.04 | 7.35 ± 1.17 |

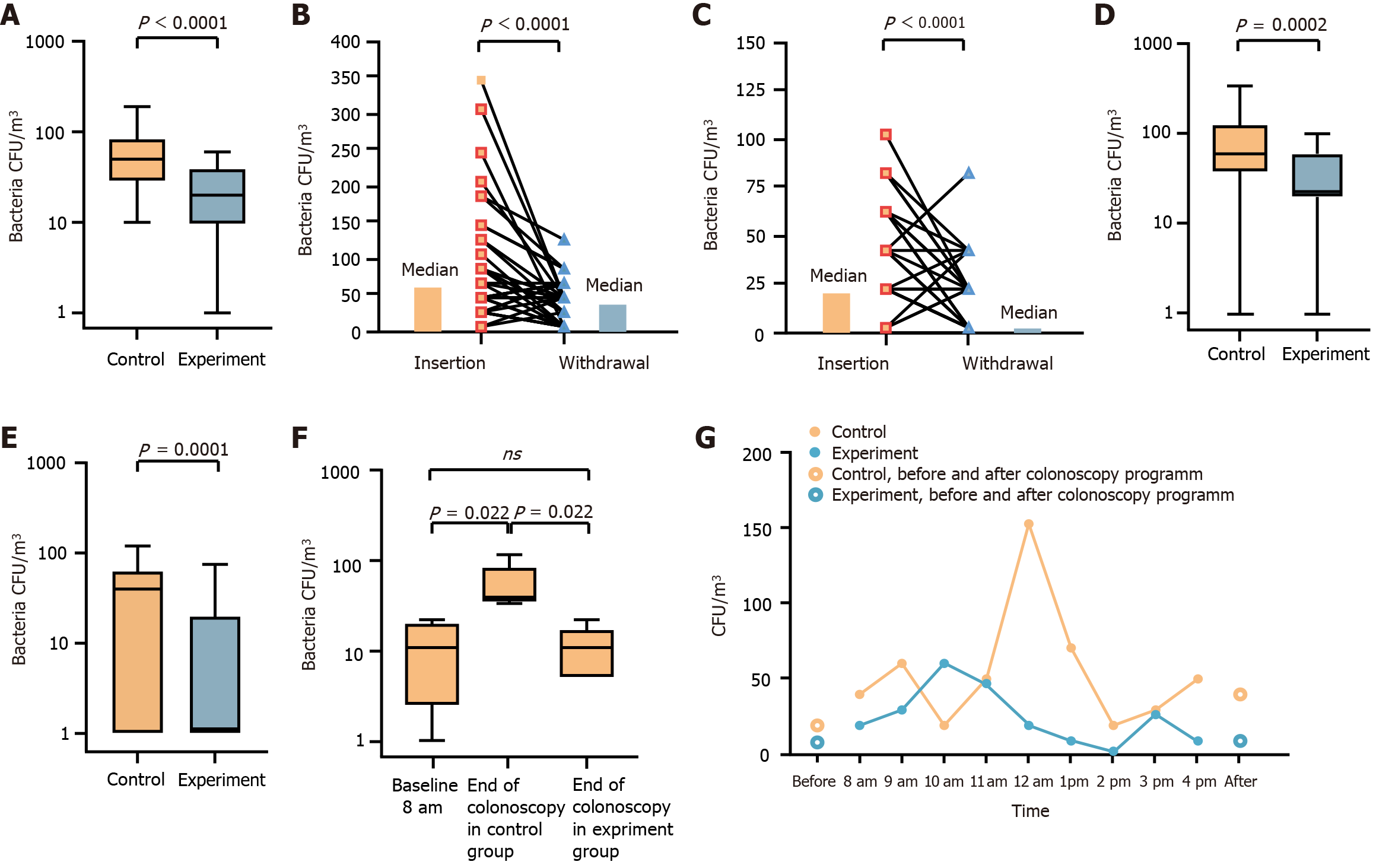

Gram-positive bacteria were the focus of this study due to their significance in nosocomial infections. In the control group, the median bioaerosol burden near the biopsy hole check valve was 50 CFU/m3 [interquartile range (IQR): 30-80] (Figure 2A). Covering the biopsy hole check valve with enzymolysis gauze significantly reduced the median bioaerosol burden to 20 CFU/m3 (IQR: 10-30) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A). Since the colonoscopy insertion and withdrawal phases differ in technique, we compared the bacterial loads separately. In the control group, the median aerosol load during withdrawal was 40 CFU/m3 (IQR: 0-60), whereas insertion generated a higher bacterial load of 60 CFU/m³ (IQR: 40-120) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2B). Similarly, in the experimental group, bacterial load during insertion was 20 CFU/m3 (IQR: 20-60), while during withdrawal, it decreased to 0 CFU/m3 (IQR: 0-20) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2C).

Comparing bacterial loads between groups, during insertion, the bacterial aerosol load in the experimental group was 20 CFU/m3 (IQR: 20-60) vs 60 CFU/m3 (IQR: 40-120) in the control group (P = 0.0002) (Figure 2D). During withdrawal, bacterial aerosol load in the experimental group was 0 CFU/m3 (IQR: 0-20) compared to 40 CFU/m3 (IQR: 0-60) in the control group (P = 0.0001) (Figure 2E). These results indicate that insertion generates a higher bacterial load than withdrawal, and enzymolysis of gauze effectively reduces bacterial contamination in both phases. To assess bacterial accumulation over a full day of colonoscopy procedures, we measured airborne bacterial load in the endoscopy suite before and after daily procedures. The median bacterial load before colonoscopies was 10 CFU/m3 (IQR: 3-18) (Figure 2F). At the end of the day, the control group exhibited a significantly increased bacterial load of 35 CFU/m3 (IQR: 33-85) (P = 0.022), while in the experimental group, it remained low at 10 CFU/m3 (IQR: 5-10) (Figure 2F). Throughout the day, bioaerosol accumulation was observed. Compared to the control group, bacterial load in the enzymolysis gauze group remained consistently lower (Figure 2G). On the second day, aerosol levels returned to baseline, and no bacterial accumulation was detected (Figure 2G).

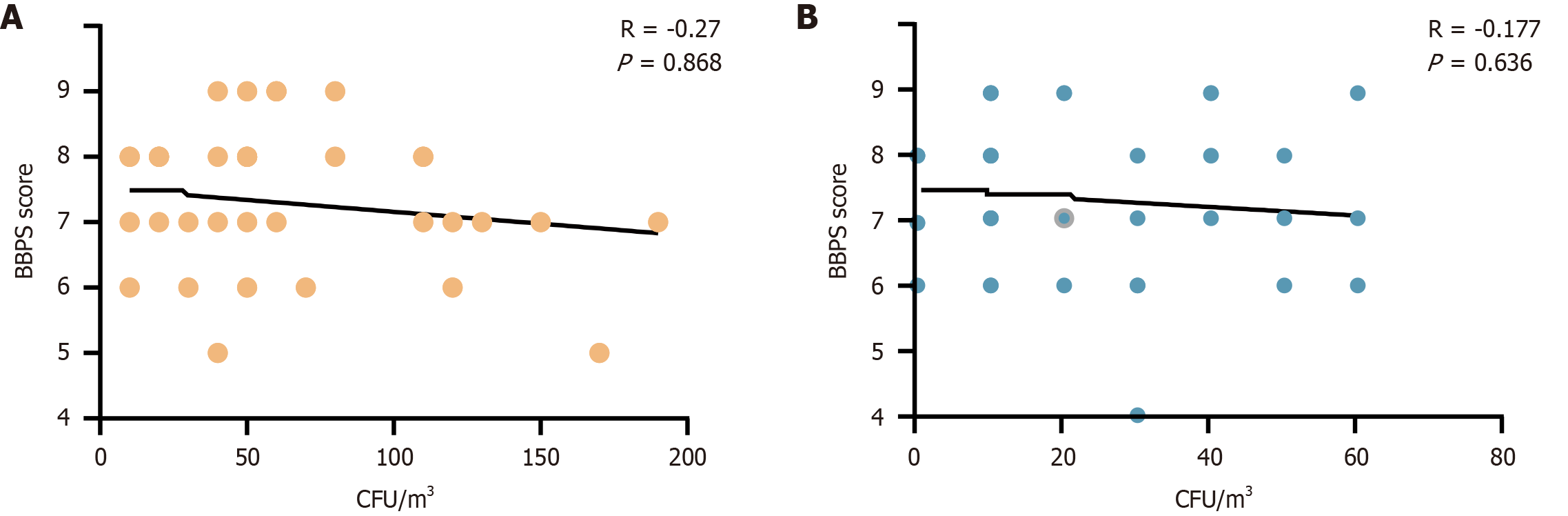

To evaluate whether lower bowel cleanliness was associated with higher bacterial load, we analyzed the correlation between BBPS scores and bacterial load. As shown in Figure 3, bacterial load negatively correlated with BBPS scores in both the control and experimental groups. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the groups. These findings suggest that bacterial load during colonoscopy is not directly influenced by intestinal cleanliness. This may be attributed to variations in bowel preparation timing and sample size limitations.

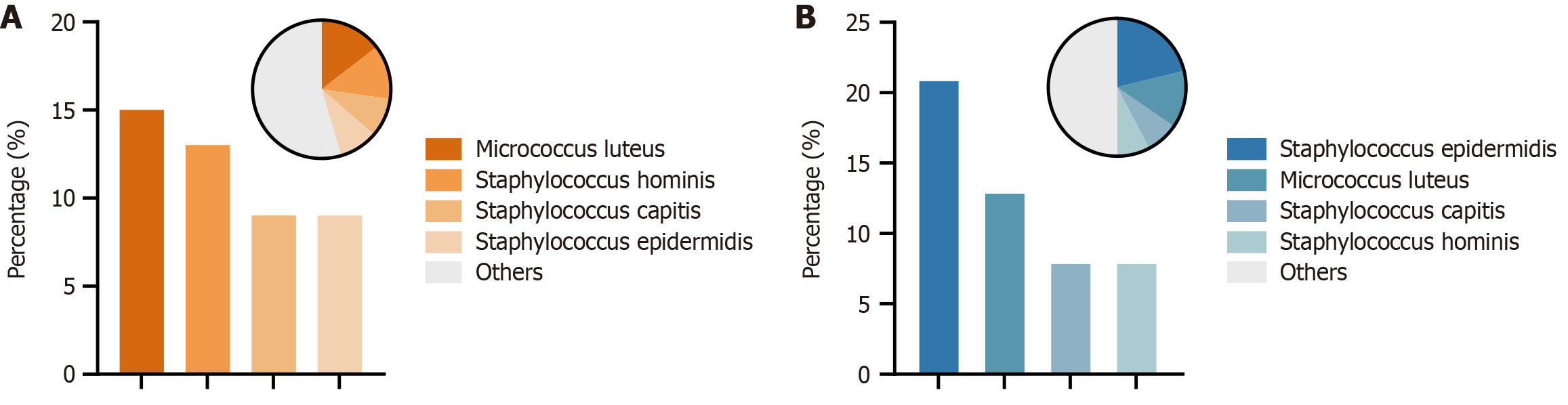

Bacterial species were identified using mass spectrometry. The predominant isolates were Gram-positive cocci. In the control group, Micrococcus luteus (M. luteus) was the most dominant strain, followed by Staphylococcus hominis (S. hominis) (Figure 4A). In the experimental group, Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) became the most prevalent strain, while M. luteus and S. hominis ranked second and fourth, respectively (Figure 4B). The findings indicate that enzymolysis of gauze had the greatest effect on reducing M. luteus and S. hominis (Figure 4).

Lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy involves close contact with patient secretions, excreta, blood, and other bodily fluids, all of which contain high bacterial loads. Studies have shown that endoscopic procedures generate aerosols containing microorganisms. Passi et al[13] visualized aerosol particles during GI endoscopy using laser light scattering technology. Additionally, procedures such as anal intubation, extubation, abdominal compression, insufflation, and retroflection can further increase aerosol dispersion in the procedure room[3]. These aerosolized particles primarily consist of patient secretions and excretions, carrying various microorganisms, including bacteria, which can attach to aerosols and potentially cause infections via the fecal-aerosol-mucosal route[14]. However, strategies to mitigate the release of fecal bacteria during lower GI endoscopy remain under investigation.

To control potential confounders, our study standardized key factors: All endoscopists had > 10 years of experience, room ventilation rates were fixed, and random assignment of patients was used to minimize bias. To minimize cross-contamination, all procedures on a given day were assigned to a single group. This ensured that each room was unused and well-ventilated overnight prior to use, providing a consistently low baseline bacterial load. Our study confirmed the presence of airborne bacterial contamination during colonoscopy, consistent with previous reports. It has been docu

To address this, we covered the biopsy hole check valve with enzymolysis gauze and collected air samples for bacterial culture. Our results demonstrated that this intervention not only reduced bacterial load near the endoscopist but also significantly decreased bacterial contamination within the entire endoscopy room (Figure 2). A noteworthy observation was that bacterial load was higher during insertion than withdrawal. This could be attributed to intestinal insufflation and abdominal compression, which are commonly performed during insertion but rarely used during withdrawal. Gram-positive bacteria are a major cause of hospital-acquired infections and are also the primary bacterial residues detected following endoscope cleaning and disinfection[15]. S.s epidermidis and M. luteus have emerged as significant pathogens in nosocomial infections, primarily due to their ability to form biofilms, carry drug resistance genes, and exploit invasive medical procedures - particularly endoscopy[16-18]. While these bacteria may pose minimal risk to immunocompetent individuals, they can cause severe complications in immunocompromised patients, including meningitis, septicemia, and endocarditis[19-22]. The findings indicate that enzymolysis of gauze had the greatest effect on reducing M. luteus and S. hominis. Therefore, we recommend using enzymolysis gauze as a simple and effective measure during colonoscopy to reduce the spread of bacterial aerosols.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, the causal relationship between bacterial aerosols and hospital-acquired infections remains unconfirmed. Directly linking this reduction to a decrease in post-colonoscopy infections would require an impractically large sample size[23], given the low reported incidence of such events. However, our findings have clear clinical relevance from an infection control perspective. The rationale for this intervention is rooted in the precautionary principle: Reducing exposure to pathogenic aerosols is a foundational goal of hospital hygiene[24]. Second, the study design compared the enzymolysis gauze with an uncovered valve but lacked a placebo control (e.g., sterile dry gauze or a saline-soaked gauze). Therefore, while we demonstrate the high efficacy of the enzymolysis gauze as a combined unit, we cannot definitively apportion the reduction in bacterial colonies between the physical barrier effect and the potential added antimicrobial or organic-matter-degrading effect of the enzymatic solution. This represents an important avenue for future research. Third, potential underreporting of endoscopy-associated infections[23,25,26]. Endoscopy-related infections are perceived as rare, but some experts suggest they may be underdiagnosed or asymptomatic, leading to underreporting[27,28]. Our study focused on quantifying Gram-positive bacteria as a surrogate for bacterial aerosol contamination[7]. While this approach allowed for a clear and reproducible assessment of our intervention’s efficacy, it does not capture the full spectrum of microorganisms. Consequently, this may lead to an underestimation of infection risks, as abundant populations such as Gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes were not quantified. Future studies should use molecular or broader culture methods to characterize the full taxonomy of endoscopy-related bioaerosols and thereby validate our intervention’s efficacy.

This study demonstrates that bacterial aerosols are present in the endoscopy room during colonoscopy and establishes a link between aerosol release from the biopsy hole check valve and environmental contamination. More importantly, covering the biopsy hole check valve with enzymolysis gauze effectively reduces bacterial load. Given its simplicity, effectiveness, and low cost, we strongly recommend adopting this method as a standard infection control measure during colonoscopy to minimize bacterial aerosol dispersion and enhance patient and healthcare worker safety.

Applying enzymolysis gauze to cover the biopsy hole check valve significantly reduces bacterial aerosol contamination in endoscopy rooms during colonoscopy. This simple and effective measure may help reduce the risk of infection during endoscopic procedures.

The authors thank the patients for contributing to this study.

| 1. | Lyra A, Forssten S, Rolny P, Wettergren Y, Lahtinen SJ, Salli K, Cedgård L, Odin E, Gustavsson B, Ouwehand AC. Comparison of bacterial quantities in left and right colon biopsies and faeces. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4404-4411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chiu PWY, Ng SC, Inoue H, Reddy DN, Ling Hu E, Cho JY, Ho LK, Hewett DG, Chiu HM, Rerknimitr R, Wang HP, Ho SH, Seo DW, Goh KL, Tajiri H, Kitano S, Chan FKL. Practice of endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: position statements of the Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE-COVID statements). Gut. 2020;69:991-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Phillips F, Crowley J, Warburton S, Gordon GSD, Parra-Blanco A. Aerosol and droplet generation in upper and lower GI endoscopy: whole procedure and event-based analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96:603-611.e0. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hussain A, Singhal T, El-Hasani S. Extent of infectious SARS-CoV-2 aerosolisation as a result of oesophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kinney TP, Kozarek RA, Raltz S, Attia F. Contamination of single-use biopsy forceps: a prospective in vitro analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van der Ploeg K, Haanappel CP, Voor In 't Holt AF, de Groot W, Bulkmans AJC, Erler NS, Mason-Slingerland BCGC, Severin JA, Vos MC, Bruno MJ. Unveiling 8 years of duodenoscope contamination: insights from a retrospective analysis in a large tertiary care hospital. Gut. 2024;73:613-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vavricka SR, Tutuian R, Imhof A, Wildi S, Gubler C, Fruehauf H, Ruef C, Schoepfer AM, Fried M. Air suctioning during colon biopsy forceps removal reduces bacterial air contamination in the endoscopy suite. Endoscopy. 2010;42:736-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gordon GSD, Warburton S, Parkes S, Kerridge A, Parra-Blanco A, Ortiz-Fernandez-Sordo J, Fitzgerald RC. Cytosponge procedures produce fewer respiratory aerosols and droplets than esophagogastroduodenoscopies. Dis Esophagus. 2024;37:doad061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kikuchi D, Ariyoshi D, Suzuki Y, Ochiai Y, Odagiri H, Hayasaka J, Tanaka M, Morishima T, Kimura K, Ezawa H, Iwamoto R, Matsuwaki Y, Hoteya S. Possibility of new shielding device for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1536-E1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Johnston ER, Habib-Bein N, Dueker JM, Quiroz B, Corsaro E, Ambrogio M, Kingsley M, Papachristou GI, Kreiss C, Khalid A. Risk of bacterial exposure to the endoscopist's face during endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zavieh FS, Mohammadi MJ, Vosoughi M, Abazari M, Raesee E, Fazlzadeh M, Geravandi S, Behzad A. Assessment of types of bacterial bio-aerosols and concentrations in the indoor air of gyms. Environ Geochem Health. 2021;43:2165-2173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang C, Li J, Cui H, Jin Y, Chen Z, Zhang L, Song S, Lu B, Wang Z, Guo Z. Lentinan Reduces Transmission Efficiency of COVID-19 by Changing Aerodynamic Characteristic of Exhaled SARS-CoV-2 Aerosols in Golden Hamsters. Microorganisms. 2025;13:597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Passi M, Stadnytskyi V, Anfinrud P, Koh C. Visualizing endoscopy-generated aerosols with laser light scattering (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96:1072-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Knowlton SD, Boles CL, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, Nonnenmann MW; CDC Epicenters Program. Bioaerosol concentrations generated from toilet flushing in a hospital-based patient care setting. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mills B, Megia-Fernandez A, Norberg D, Duncan S, Marshall A, Akram AR, Quinn T, Young I, Bruce AM, Scholefield E, Williams GOS, Krstajić N, Choudhary TR, Parker HE, Tanner MG, Harrington K, Wood HAC, Birks TA, Knight JC, Haslett C, Dhaliwal K, Bradley M, Ucuncu M, Stone JM. Molecular detection of Gram-positive bacteria in the human lung through an optical fiber-based endoscope. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:800-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hoshi K, Kikuchi H, Narita K, Fukutoku Y, Asari T, Miyazawa K, Murai Y, Sawada Y, Tatsuta T, Hasui K, Hiraga H, Chinda D, Mikami T, Subsomwong P, Asano K, Nakane A, Fukuda S, Sakuraba H. Bacterial exposure risk to the endoscopist's face while performing endoscopy. DEN Open. 2023;3:e209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Maimone S, Saffioti F, Filomia R, Caccamo G, Saitta C, Pallio S, Consolo P, Sabatini S, Sitajolo K, Franzè MS, Cacciola I, Raimondo G, Squadrito G. Elective endoscopic variceal ligation is not a risk factor for bacterial infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:366-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lorenz R, Herrmann M, Kassem AM, Lehn N, Neuhaus H, Classen M. Microbiological examinations and in-vitro testing of different antibiotics in therapeutic endoscopy of the biliary system. Endoscopy. 1998;30:708-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Khan A, Aung TT, Chaudhuri D. The First Case of Native Mitral Valve Endocarditis due to Micrococcus luteus and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Cardiol. 2019;2019:5907319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Karchmer AW, Archer GL, Dismukes WE. Staphylococcus epidermidis causing prosthetic valve endocarditis: microbiologic and clinical observations as guides to therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:447-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Buonsenso D, Lombardo A, Fregola A, Ferrari V, Piastra M, Calvani M, Lazzareschi I, Valentini P. First Report of Micrococcus luteus Native Valve Endocarditis Complicated With Pulmonary Infarction in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:e284-e286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Heidari V, Habibi Z, Hojjati Marvasti A, Ebrahim Soltani Z, Naderian N, Tanzifi P, Nejat F. Different Behavior and Response of Staphylococcus Epidermidis and Streptococcus Pneumoniae to a Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: An in vitro Study. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2017;52:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang P, Xu T, Ngamruengphong S, Makary MA, Kalloo A, Hutfless S. Rates of infection after colonoscopy and osophagogastroduodenoscopy in ambulatory surgery centres in the USA. Gut. 2018;67:1626-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fennelly KP. Particle sizes of infectious aerosols: implications for infection control. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:914-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Silvis SE, Nebel O, Rogers G, Sugawa C, Mandelstam P. Endoscopic complications. Results of the 1974 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Survey. JAMA. 1976;235:928-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Vennes JA. Infectious complications of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:60S-64S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nelson DB. Recent advances in epidemiology and prevention of gastrointestinal endoscopy related infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:326-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Beilenhoff U, Biering H, Blum R, Brljak J, Cimbro M, Dumonceau JM, Hassan C, Jung M, Neumann C, Pietsch M, Pineau L, Ponchon T, Rejchrt S, Rey JF, Schmidt V, Tillett J, van Hooft J. Prevention of multidrug-resistant infections from contaminated duodenoscopes: Position Statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (ESGENA). Endoscopy. 2017;49:1098-1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/