Published online Nov 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i42.111282

Revised: August 13, 2025

Accepted: October 13, 2025

Published online: November 14, 2025

Processing time: 138 Days and 12.6 Hours

Tofacitinib is an oral, selective Janus kinase inhibitor that is approved for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC). The 8-week induction protocol involves the administration of 10 mg twice daily (bid) with the possibility of extending the induction period to 16 weeks. The maintenance dose of tofacitinib is either 5 mg or 10 mg bid.

To assess predictors for clinical remission and drug persistence in patients with UC receiving the extended induction tofacitinib protocol.

This was a real-world multicenter retrospective study in patients with moderate-to-severe UC. Patients received physician-directed extended induction tofacitinib treatment. We collected clinical and demographic data at baseline and data regar

Thirty-seven consecutive patients from 11 medical centers were included [51.4% males with median age 39 (17-64) years]. Twenty-eight patients continued treat

Our results supported the extended induction strategy with tofacitinib in selected patients with UC. Patients with prior failure of advanced therapies particularly benefitted, highlighting the importance of personalized maintenance regimens.

Core Tip: This multicenter, retrospective cohort study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of administering a 16-week extended induction protocol for tofacitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. At week 52 over half of the patients achieved clinical remission with a drug persistence rate of 75.7%. Notably, prior exposure to biologics was associated with the need for continuous administration of escalated doses while active smoking was significantly associated with treatment discontinuation. Extended induction therapy in selected patients may be beneficial. Our study highlights the need for further research to identify predictors of long-term response and optimal dosing strategies.

- Citation: Tzouvala M, Zacharopoulou E, Kalafateli M, Viazis N, Psistakis A, Theodoropoulou A, Drygiannakis I, Karmiris K, Koutroubakis IE, Kevrekidou P, Soufleris K, Katsaros M, Giouleme O, Fousekis F, Katsanos K, Christodoulou D, Gaki A, Papathanasiou E, Bamias G, Zampeli E, Michopoulos S, Kyriakos N, Veretanos C, Argyriou K, Kapsoritakis A, Tribonias G, Mantzaris GJ, Liatsos C. Value of tofacitinib extended induction therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: A real-world 52-week follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(42): 111282

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i42/111282.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i42.111282

Therapeutic options for ulcerative colitis (UC) have significantly expanded over the last decade. The European Medicines Agency has approved eight biological agents and five small molecule drugs for the treatment of UC[1]. While this broadened arsenal enhances treatment possibilities, it simultaneously underscores the need to personalize therapy by identifying the patient profiles that will best respond to specific agents and dosing strategies. Because controlled clinical trials will often include only highly selected populations, real-world data are essential to bridge the gap between trial efficacy and effectiveness in clinical practice[2,3].

Tofacitinib is an oral small molecule drug that selectively inhibits Janus kinases (JAKs), particularly JAK1 and JAK3. By blocking cytokine signaling pathways mediated by these kinases, tofacitinib modulates immune responses by attenuating interleukins and type I/type II interferon signaling, which is implicated in UC pathogenesis[4,5]. Tofacitinib was the first approved JAK inhibitor for UC and is currently indicated for adults with moderate-to-severe disease who have shown inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance to either conventional or advanced therapies. Tofacitinib is reim

Clinical trials have established the efficacy of an induction regimen of 10 mg twice daily (bid) for 8 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg bid. In cases where the response is insufficient at 8 weeks, an extended induction period of up to 16 weeks with 10 mg bid is suggested[7,8]. Patients who do not experience a therapeutic benefit by week 16 should discontinue therapy. In pivotal phase 3 trials [OCTAVE 1 (NCT01465763) and OCTAVE 2 (NCT01458951)], 18.5% of patients treated with 10 mg bid achieved clinical remission by week 8, significantly outperforming (8.2%) the placebo group. Additionally, maintenance of remission at 52 weeks was observed in 34.3% of patients maintained on 5 mg bid and 40.6% of patients maintained on 10 mg bid vs 11.1% of patients in the placebo group[4].

Clinical practice has demonstrated that de-escalating the dose from 10 mg bid to 5 mg bid during maintenance has led to a loss of response in nearly 50% of patients. Baseline endoscopic severity (Mayo subscore of 3) and previous failure of biologics are potential risk factors for relapse. The response can be restored by re-escalating the dose to 10 mg bid[9,10]. Conversely, patients with difficult-to-treat disease may benefit from continuous dosing of 10 mg bid as maintenance therapy. Approximately one-third of patients require extended induction, and among these nearly half achieve a clinical benefit. These patients are referred to as delayed responders and appear to have no differences in safety outcomes[11]. The clinical characteristics that define successful long-term responders after extended induction and the likelihood of successful dose de-escalation remain insufficiently characterized. The present multicenter, observational study evaluated clinical remission and drug persistence rates at week 52 in patients with moderate-to-severe UC who underwent an extended 16-week induction period with tofacitinib and identified predictive factors associated with these outcomes.

This was a retrospective multicenter cohort study that prospectively collected data from July 2018 to January 2025. Consecutive patients with moderate-to-severe UC who initiated tofacitinib therapy based on international guidelines (inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance/contraindications to prior treatments)[8] and required a physician-directed 16-week extended induction were eligible. Patients were followed until week 52. Exclusion criteria were primary nonresponse or signs of infectious colitis/fulminant colitis/toxic megacolon during the initial 8-week induction regimen as well as continuation of tofacitinib as part of combination therapy with other advanced therapies. Concomitant use of oral aminosalicylates and corticosteroids was allowed. Patients were enrolled from 11 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) tertiary referral centers in Greece. The date of tofacitinib initiation was set as the time point of baseline assessment. Treatment decisions were made by physicians according to national guidelines and a summary of product characteristics.

The study protocol received ethical approval from the Scientific Committee of the coordinating institution (General Hospital of Nikaia and Piraeus “Agios Panteleimon”). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. All investigators adhered to the summary of product characteristics for tofacitinib during the study period[8].

Clinical and demographic data were extracted from institutional electronic databases and/or patient records. Collected baseline characteristics included: Sex; age; smoking status; body mass index; disease extent and duration; family history of IBD; extraintestinal manifestations; previous and concomitant UC treatments; partial Mayo score; and endoscopic and histological assessments (endoscopic Mayo score, UC Endoscopic Index of Severity, and NANCY index). Follow-up assessments were performed at weeks 8, 16, 24, and 52. These included clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic evaluations, documentation of treatment modifications (e.g., de-escalation), adverse events (AEs), and drug persistence rate. A ± 6-week window was allowed for assessments due to the retrospective nature of the study and reflects the mean time of regular patient assessment according to the availability of the participating centers.

The primary outcome was the identification of predictors for clinical remission at week 52. Secondary endpoints included differences in clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic results at week 52 between patients receiving 5 mg bid vs 10 mg bid and identification of predictors for treatment discontinuation. Clinical remission was defined as a partial Mayo score ≤ 2 with no subscore > 1 and a rectal bleeding subscore of 0. Biochemical response was defined as any reduction in fecal calprotectin or C-reactive protein from baseline.

Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range, depending on distribution. Categorical variables were reported as n (%). Normality was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Between-group comparisons were made using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data. Binary logistic regression was applied to determine factors associated with remission and drug discontinuation at week 52. Variables with a P value < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in multivariate models using backward selection. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Considering that the percentage of missing data was small (< 5%) for the variables of interest, we removed any cases with missing data from the univariate analyses. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.2.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

Thirty-seven patients received tofacitinib with an extended induction protocol and were included in the analysis. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The median age was 39 (17-64) years, and 19 patients (51.4%) were male. The indications for tofacitinib initiation were inadequate response or loss of response to previous treatments in 33 patients (89.2%), intolerance to previous treatment in 1 patient [anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) treatment] (2.7%), contraindications to other treatment modalities in 2 patients (5.4%), and steroid-dependent disease in 1 patient (2.7%). Thirty-three patients (89.2%) had received biologic treatment previously. Concomitant 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) use was reported by 20 patients (54.1%) and concomitant corticosteroid use was reported by 23 patients (62.2%). None of the patients had ulcerative proctitis (E1 Montreal classification). The median total Mayo score was 9 (range: 5-12), and 30 patients (out of 31 with available data) had an endoscopic Mayo subscore ≥ 2.

| Quantitative variable | Median (range)/n | IQR/percent (%) |

| Age in years | 39 (17-64) | 32 |

| Disease duration in years | 6 (1-28) | 13 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 23.35 (14.00-36.30) | 10.76 |

| Number of previous treatments | 2 (0-4) | 1 |

| CRP in mg/dL | 8.6 (0.5-61.6) | 13.98 |

| Albumin in g/dL | 4.1 (3.0-5.2) | 0.33 |

| Hb in g/dL | 13.3 (8.9-15.7) | 1.68 |

| PLT as × 109/L | 315 (127-705) | 181.25 |

| WBC per mL | 8935 (4400-16990) | 2760.7 |

| Granulocytes (absolute count) per mL | 5300.0 (2600.0-11060.5) | 2526.4 |

| UCEIS | 6.5 (2.0-10.0) | 3 |

| Total Mayo score | 9 (5-12) | 4 |

| NANCY score | 3 (3-4) | 1 |

| Sex as male/female | 19/18 | 51.4/48.6 |

| Montreal classification as E1/E2/E3 | 0/10/27 | 0/27/73 |

| Family history of IBD | 3 | 8.1 |

| Smoking as current/in the past | 4/7 | 10.8/18.9 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 11 | 29.7 |

| Musculoskeletal as peripheral arthritis/axonal arthritis/both | 6/2/1 | 16.2/5.4/2.7 |

| Dermatological as pyoderma gangrenosum/psoriasis | 1/1 | 2.7/2.7 |

| Liver/biliary | 0 | 0 |

| Stomal | 0 | 0 |

| Ocular (uveitis) | 1 | 2.7 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Active extraintestinal manifestation | 6 | 16.2 |

| Previous treatment | 32 | 86.5 |

| Steroids | 33 | 89.2 |

| 5-ASA | 30 | 81.1 |

| Azathioprine | 18 | 48.6 |

| MTX | 2 | 5.4 |

| Biologics | 33 | 89.2 |

| Anti-TNFα as infliximab/adalimumab/golimumab | 29 (24/11/5) | 78.4 (64.9/29.7/13.5) |

| Vedolizumab | 19 | 51.4 |

| Anti-IL12/23 | 6 | 16.2 |

| Bloody stool | ||

| Traces of blood < 50% | 11 | 29.7 |

| Blood > 50% | 22 | 9.5 |

| Only blood | 1 | 2.7 |

| Number of bowel movements | ||

| 1-2 more than normal | 6 | 16.2 |

| 3-4 more than normal | 17 | 45.9 |

| ≥ 5 more than normal | 13 | 35.1 |

| PGA | ||

| Mild disease | 8 | 21.6 |

| Moderate disease | 14 | 37.8 |

| Severe disease | 15 | 40.5 |

| Urgency | ||

| In 5 minutes | 15 | 40.5 |

| In 1 minute | 3 | 8.1 |

| Incontinence | 3 | 8.1 |

| 5-ASA coadministration | 20 | 54.1 |

| Steroids coadministration | 23 | 62.2 |

| Endoscopic Mayo score as 0/1/2/3 | 1/0/11/19 | 2.7/0/29.7/51.4 |

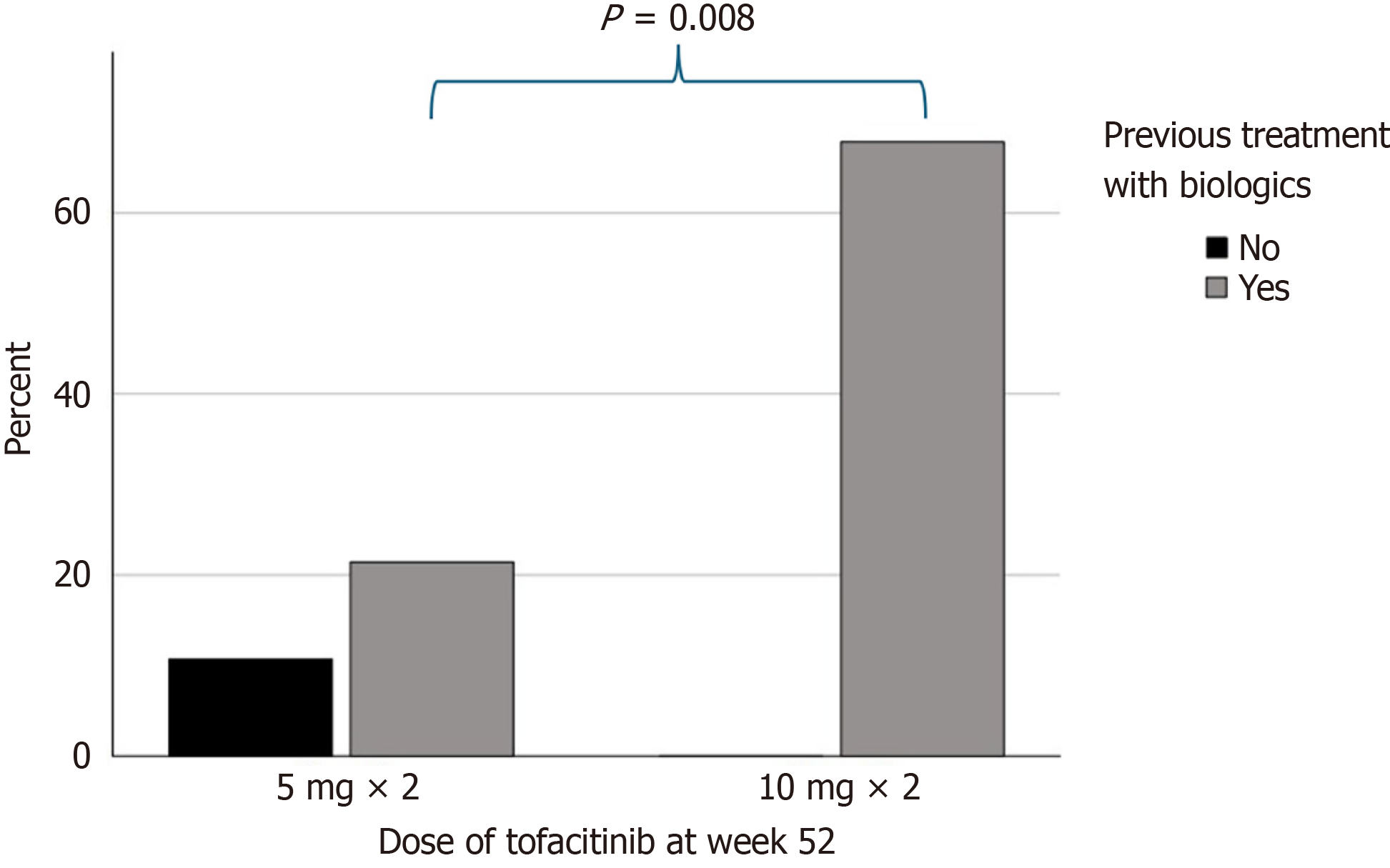

Nine patients (24.3%) discontinued tofacitinib before week 52 (8 patients due to inadequate response and 1 patient due to AEs). Of the 28 patients (75.7%) that continued treatment, 9 patients (32.1%) were receiving 5 mg bid of tofacitinib and 19 patients (67.9%) were receiving 10 mg bid of tofacitinib. Eleven patients (39.3%) were receiving 5-ASA concomitantly and two patients (7.1%) were receiving corticosteroids concomitantly. De-escalation of tofacitinib to 5 mg bid was attempted in 17 patients (60.7%): 9 patients (52.9%) were successfully de-escalated and continued with 5 mg bid up to week 52. The differences in the clinical and biochemical parameters between patients receiving 5 mg and 10 mg at week 52 are presented in Table 2. Patients treated with 10 mg bid were more likely to have received previous treatment with biologics than patients treated with 5 mg bid (100% vs 66.7%, P = 0.008). Interestingly, all patients receiving 10 mg of tofacitinib had previously been treated with biologics (Figure 1). A trend towards a higher total Mayo score in patients treated with 10 mg was also observed but failed to reach statistical significance.

| Factors | Tofacitinib 5 mg bid, n = 9 | Tofacitinib 10 mg bid, n = 19 | P value |

| Quantitative variables [median (range)] | |||

| Age in years | 43 (23-61) | 38 (17-62) | 0.247 |

| Disease duration in years | 4 (2-15) | 8 (1-28) | 0.141 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 28.1 (19.0-36.2) | 23.8 (14.0-36.3) | 0.275 |

| Number of previous treatments | 1 (0-4) | 2 (1-4) | 0.241 |

| CRP at baseline in mg/dL | 10.1 (3.0-18.0) | 4.8 (0.7-17.9) | 0.170 |

| Albumin at baseline in g/dL | 4.1 (3.1-4.5) | 4.3 (3.1-5.2) | 0.610 |

| Hb at baseline in g/d | 13.2 (8.9-13.6) | 13.6 (10.2-15.5) | 0.881 |

| PLT at baseline as × 109/L | 315 (265-390) | 297 (192-705) | 0.183 |

| WBC at baseline per mL | 8590 (5230-12200) | 9600 (6000-16990) | 0.522 |

| Granulocytes absolute count at baseline per mL | 5160 (2600-9000) | 5476 (2881-11060) | 0.806 |

| UCEIS at baseline | 6 (2-7) | 7 (4-10) | 0.171 |

| Full Mayo score at baseline | 7 (5-10) | 9 (5-12) | 0.060 |

| NANCY score at baseline | 4 (4-4) | 3 (3-4) | 0.091 |

| CRP in mg/dL at week 52 | 5.0 (0.5-40.0) | 1.0 (0.1-69.0) | 0.263 |

| Albumin in g/dL at week 52 | 4.1 (3.9-4.3) | 4.5 (3.6-5.0) | 0.175 |

| Hb at week 52 | 13.2 (10.1-14.6) | 12.8 (11.3-16.3) | 0.918 |

| PLT as × 109/L at week 52 | 311.5 (221.0-391.0) | 300.0 (199.0-572.0) | 0.934 |

| WBC per mL at week 52 | 7010 (4390-10600) | 6800 (4550-9400) | 0.881 |

| Granulocytes absolute count at week 52 | 4408.0 (2742.0-7290.0) | 4544.5 (3440.0-6950.0) | 0.826 |

| Qualitative variables [n (%)] | |||

| Sex as male/female | 4/5 (44.4/55.5) | 11/8 (57.9/42.1) | 0.505 |

| Montreal classification as E1/E2/E3 | 0/4/5 (0/44.4/55.5) | 0/4/15 (21.1/78.9) | 0.201 |

| Family history of IBD | 2 (22.2) | 1 (5.3) | 0.175 |

| Smoking for current/in the past | 0/2 (0/22.2) | 1/3 (5.3/15.8) | 0.735 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 4 (44.4) | 3 (15.8) | 0.102 |

| Musculoskeletal as peripheral arthritis/axonal arthritis/both | 2/1/1 (22.2/11.1/11.1) | 1/0/0 (5.3/0/0) | 0.072 |

| Dermatological as pyoderma gangrenosum/psoriasis | 0 | 0/1 (0/5.3) | 0.483 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Active extraintestinal manifestation | 2 (22.2) | 1 (5.3) | 0.175 |

| Indication of treatment initiation | 0.103 | ||

| Inadequate response or loss of response in previous treatments | 7 (77.8) | 19 (100) | |

| Intolerance to previous treatment | 1 (11.1) | 0 | |

| Contraindications for other treatment modality | 0 | 0 | |

| Steroid dependency | 1 (11.1) | 0 | |

| Previous treatment | 6 (66.7) | 19 (100) | 0.008a |

| Steroids | 8 (88.9) | 16 (84.2) | 0.741 |

| 5-ASA | 8 (88.9) | 13 (68.4) | 0.243 |

| Azathioprine | 5 (55.6) | 8 (42.1) | 0.505 |

| MTX | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0.483 |

| Biologics | 6 (66.7) | 19 (100) | 0.008a |

| Anti-TNFα as infliximab/adalimumab/golimumab | 6 (66.7) [5 (55.6)/2 (22.2)/1 (11.1)] | 18 (89.5) [14 (73.7)/5 (26.3)/2 (10.5)] | 0.141 (0.337/0.815/0.963) |

| Vedolizumab | 4 (44.4) | 11 (57.9) | 0.505 |

| Anti-IL12/23 | 2 (22.2) | 2 (10.5) | 0.409 |

| Bloody stool at baseline | 0.255 | ||

| Traces of blood < 50% | 5 (55.6) | 4 (21.2) | |

| Blood > 50% | 4 (44.4) | 12 (63.2) | |

| Only blood | 0 | 1 (5.3) | |

| Number of bowel movements at baseline | 0.484 | ||

| 1-2 more than normal | 2 (22.2) | 4 (21.1) | |

| 3-4 more than normal | 6 (66.7) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Bloody stool at baseline | 1 (11.1) | 6 (31.6) | |

| Traces of blood < 50% | 0.222 | ||

| Blood > 50% | 4 (44.4) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Only blood | 3 (33.3) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Severe disease | 2 (22.2) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Urgency at baseline | 0.114 | ||

| In 5 minutes | 5 (55.5) | 6 (31.6) | |

| In 1 minute | 2 (22.2) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Incontinence | 1 (11.1) | 1 (5.3) | |

| 5-ASA coadministration at baseline | 5 (55.6) | 9 (47.4) | 0.686 |

| Steroids coadministration at baseline | 5 (55.6) | 12 (63.2) | 0.700 |

| Endoscopic Mayo score (0/1/2/3) at baseline | 0/0/4/4 (0/0/44.4/44.4) | 1/0/4/10 (5.3/0/21.1/52.6) | 0.452 |

| Bloody stool at week 52 | 0.110 | ||

| Traces of blood < 50% | 0 | 5 (26.3) | |

| Blood > 50% | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| Only blood | 0 | 0 | |

| Number of bowel movements at week 52 | 0.448 | ||

| 1-2 more than normal | 3 (33.3) | 7 (36.8) | |

| 3-4 more than normal | 0 | 3 (15.8) | |

| ≥ 5 more than normal | 0 | 1 (5.3) | |

| PGA at week 52 | 0.215 | ||

| Mild disease | 2 (22.2) | 6 (31.6) | |

| Moderate disease | 0 | 4 (21.1) | |

| Severe disease | 0 | 0 | |

| Urgency at week 52 | 0.272 | ||

| In 5 minutes | 1 (11.1) | 0 | |

| In 1 minute | 0 | 1 (5.3) | |

| Incontinence | 0 | 0 | |

| 5-ASA coadministration at week 52 | 3 (33.3) | 8 (42.1) | 0.657 |

| Steroids coadministration at week 52 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (5.3) | 0.512 |

Clinical remission was achieved in 16 out of 28 patients (57.1%) who continued tofacitinib until week 52. Six patients (66.7%) received 5 mg, and ten patients (52.6%) received 10 mg bid (P = 0.483). Factors associated with clinical remission are presented in Table 3. In the univariate binary logistic regression analysis, only 5-ASA coadministration at week 52 was negatively associated with clinical remission [odds ratio: 0.11, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.02-0.66, P = 0.01]. Multivariate analysis could not be performed.

| Factors | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 1.003 (0.949-1.061) | 0.909 |

| Male sex | 0.778 (0.173-3.493) | 0.743 |

| Montreal classification | 1.500 (0.288-7.807) | 0.630 |

| Disease duration | 1.030 (0.918-1.154) | 0.616 |

| Family history of IBD | 1.571(0.126-19.668) | 0.726 |

| Current smoker | 1.250 (0.173-9.019) | 0.825 |

| BMI | 1.026 (0.906-1.163) | 0.684 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 2.773 (0.357-14.454) | 0.384 |

| Active extraintestinal manifestation | 1.571 (0.126-19.668) | 0.726 |

| Previous treatment | 0.545 (0.043-6.889) | 0.639 |

| Number of previous treatments | 0.636 (0.051-7.965) | 0.726 |

| Partial Mayo | 1.461 (0.928-2.301) | 0.102 |

| Coadministration of 5-ASA at week 52 | 0.115 (0.020-0.665) | 0.015a |

| Coadministration of steroids at week 52 | 0.786 (0.044-14.026) | 0.870 |

| CRP | 1.002 (0.866-1.159) | 0.981 |

| Albumin | 0.654 (0.132-3.247) | 0.603 |

| Hb | 0.790 (0.474-1.316) | 0.365 |

| PLT | 0.999 (0.992-1.006) | 0.862 |

| WBC | 1.00 (1.000-1.000) | 0.881 |

| Gran | 1.00 (1.000-1.001) | 0.725 |

| Endoscopic Mayo | 0.383 (0.083-1.761) | 0.218 |

| Full Mayo score | 1.478 (0.902-2.423) | 0.121 |

| Dose of tofacitinib at week 52 | 0.556 (0.106-2.901) | 0.486 |

Nine patients discontinued treatment before week 52 (drug persistence rate: 75.6%). In the univariate analysis active smoking (odds ratio: 16.5, 95%CI: 1.3-201.3, P = 0.028) was significantly associated with treatment discontinuation at week 52 (Table 4). Multivariate analysis could not be performed.

| Factors | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 1.040 (0.979-1.105) | 0.208 |

| Male sex | 1.442 (0.319-6.529) | 0.635 |

| Montreal classification | 1.400 (0.238-8.240) | 0.710 |

| Disease duration | 1.012 (0.911-1.125) | 0.819 |

| Family history of IBD | NA | |

| Current smoker | 16.500 (1.353-201.290) | 0.028a |

| BMI | 1.008 (0.883-1.150) | 0.910 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 2.400 (0.500-11.519) | 0.274 |

| Active extraintestinal manifestation | 4.167 (0.667-26.017) | 0.127 |

| Previous treatment | 0.960 (0.087-10.573) | 0.973 |

| Number of previous treatments | 0.866 (0.445-1.687) | 0.673 |

| Partial Mayo | 1.193 (0.779-1.827) | 0.417 |

| CRP | 1.056 (0.985-1.132) | 0.127 |

| Albumin | 0.553 (0.141-2.159) | 0.394 |

| Hb | 1.155 (0.730-1.829) | 0.538 |

| PLT | 1.001 (0.994-1.007) | 0.854 |

| WBC | 1.000 (1.000-1.000) | 0.857 |

| Gran | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.224 |

| Endoscopic Mayo | 1.290 (0.343-4.848) | 0.706 |

| Full Mayo score | 1.385 (0.835-2.297) | 0.207 |

During the 52-week period of treatment with tofacitinib the following AEs were observed: Hyperlipidemia (n = 1); coronavirus disease 2019 infection (n = 2); Clostridium difficile infection (n = 1); lung infection (n = 1); abnormal liver enzymes (n = 1); and cytomegalovirus colitis (n = 2). Only 1 patient with cytomegalovirus colitis was hospitalized and discontinued treatment at week 24. Τhis patient received intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg bid for 14 days, followed by oral valganciclovir 450 mg S 2 × 2/day for an additional 7 days. All other AEs were classified as mild to moderate and did not lead to therapy discontinuation. All AEs were observed in patients treated with 10 mg bid of tofacitinib. AEs only occurred during the first 24 weeks of treatment. No deaths were reported.

This real-world multicenter study demonstrated that clinical remission was achieved after 52 weeks in 57% of patients with moderate-to-severe UC who underwent an extended 16-week induction regimen with tofacitinib. The remission rates from our study aligned with prior clinical trials[4,11], supporting the long-term efficacy of tofacitinib across different maintenance dosing strategies. Co-administration of 5-ASA at week 52 was inversely associated with remission, suggesting that these patients may be a treatment-resistant subgroup in which monotherapy with tofacitinib was not considered adequate by clinicians. No association between remission and prior experience with advanced therapies was observed.

The OCTAVE clinical program showed that one-third of patients failed to respond to tofacitinib at week 8 but benefited from an extended 16-week induction period. In the OCTAVE open study, half of the delayed responders achieved remission after receiving continuous tofacitinib (10 mg bid) for 1 year, regardless of previous anti-TNF exposure[11,12]. These findings highlight the therapeutic value of prolonged induction in selected patients. Our findings confirmed these results, showing that 66.7% of patients receiving 5 mg and 41.2% of patients receiving 10 mg achieved remission at week 52. Our results support the applicability of extended induction strategies[13]. Similar trends were observed in other cohorts, like the Japanese subgroup of patients from the OCTAVE sustain study[14].

De-escalation from 10 mg to 5 mg was attempted in 42.3% of our cohort and was successful in half of the patients through week 52, reflecting real-world practices often driven by safety and cost considerations. These findings echo previous real-world and interventional studies in which de-escalation was feasible in carefully selected patients (particularly those with favorable endoscopic and clinical parameters at baseline). Yu et al[10] provided retrospective evidence that de-escalation was attempted in 48% of their patients, and 56% experienced deterioration of UC. Likewise, Vermeire et al[15] found that 77.1% of patients in stable condition for more than 2 years on a dose of 10 mg bid were successfully de-escalated. A baseline Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 and absence of prior anti-TNF failure were associated with increased rates of clinical remission. A subgroup analysis of the OCTAVE clinical program demonstrated that patients with prior exposure to anti-TNF agents exhibited increased remission rates when treated with 10 mg bid of tofacitinib[16]. Our findings also revealed a significantly higher proportion of biologic-experienced patients in the 10 mg bid group, underscoring the necessity for sustained, intensive therapeutic strategies in this population.

Drug persistence rate at 52 weeks was 74.3% (26/35 patients). Active smoking was identified as a negative predictor of treatment continuation. Efforts have been undertaken to develop predictive models for clinical outcomes with tofacitinib treatment. A post hoc analysis of the OCTAVE program demonstrated that changes in the rectal bleeding subscore may serve as an indicator of clinical deterioration while improvement in the endoscopic subscore could predict treatment response[17].

Moreover, an integrated analysis of the OCTAVE and RIVETING trials found no significant association between smoking status and the overall efficacy or safety of tofacitinib. Nonetheless, never-smokers were disproportionately represented compared with ever-smokers [47.5% (270/569) vs 37.2% (125/336), respectively][17,18]. Additional parameters, such as younger age (< 40 years), female sex, and initiation with a 10 mg bid regimen, collected at baseline in the OCTAVE open trial were identified as predictors of treatment discontinuation. Notably, the potential impact of active smoking on long-term drug persistence remains insufficiently studied and warrants further investigation.

Long-term safety data extending up to 9.2 years in patients with UC treated with tofacitinib did not reveal any novel safety concerns beyond those already established (i.e. herpes zoster and other infections). Notably, the incidence of herpes zoster was comparable between dosing regimens: 10.5% of patients treated with 5 mg bid (incidence rate: 2.71; 95%CI: 1.72-4.06) and 8.1% of patients treated with 10 mg bid (incidence rate: 3.44; 95%CI: 2.71-4.39). Most of these cases were nonserious, and patients were able to continue therapy[19].

In the context of prolonged induction and maintenance therapy with 10 mg bid, the frequency of AEs of special interest, such as serious infections, opportunistic infections, herpes zoster, malignancies, gastrointestinal perforation, major adverse cardiovascular events, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, was similar to that of the treatment arm of 5 mg bid in the original OCTAVE program. Only a numerically greater occurrence of serious infections was noted among delayed responders[11].

We have reported a single case of hyperlipidemia managed successfully with statin therapy here. No cases of herpes zoster nor thromboembolic events were observed in our cohort, likely due to the relatively young median age of the study population. We were unable to statistically compare the safety profiles between 10 mg and 5 mg because of the small sample size. Remarkably, all AEs were recorded among patients receiving 10 mg bid and were exclusively observed within the initial 24 weeks of treatment. However, the small sample size and the study design did not allow us to assume a dose effect or a decrease of risk over time. Nevertheless, our findings emphasized that most AEs tended to emerge during the early phases of treatment initiation.

Notably, this study had limitations. First, it was a retrospective analysis prone to recall bias and included a relatively small number of patients. However, we included consecutive patients from 11 IBD-specialized centers across Greece to enhance both the robustness of our results and their external validity. This multicenter approach substantially strengthened the reliability and generalizability of our findings across different practice settings, while providing a comprehensive real-world depiction of the data despite the small sample size. The small sample size precluded the performance of a multivariate analysis. Therefore, the reported predictors should be interpreted solely as associations. Furthermore, not all patients had available endoscopic indices and/or calprotectin values at 52 weeks. Therefore, we were unable to assess endoscopic remission rates. It is worth noting that the data collection window of ± 6 weeks (although somewhat arbitrary) was reasonable as it reflects routine clinical practice in which the typical interval for routine patient evaluations are dictated by the scheduling capacity of the participating centers.

This multicenter, real-world, retrospective cohort study provided meaningful insights into the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe UC requiring extended induction therapy. Our findings demonstrated that most patients achieved clinical remission after 52 weeks of treatment, highlighting the clinical value of this therapeutic approach in delayed responders. Importantly, a successful dose de-escalation to 5 mg bid was achieved in almost half of the patients, demonstrating its potential role in long-term disease control. Prior biologic exposure was associated with the need to maintain the 10 mg bid dose, emphasizing the challenge of managing biologic-experienced cases. Safety outcomes were favorable with mild-to-moderate AEs occurring within the first 24 weeks of treatment and exclusively in the high-dose group. Active smoking emerged as a significant predictor of treatment discontinuation.

Taken together, our real-world findings: (1) Supported the extended induction strategy of tofacitinib in selected patients, particularly those with prior treatments failure; (2) Underscored the importance of personalized maintenance regimens; and (3) Effectively complemented controlled trial data, thereby contributing meaningfully to the understanding of tofacitinib use in routine clinical practice. Future prospective studies are needed to refine predictive models for remission and safe de-escalation, thereby optimizing long-term outcomes in UC management.

Hellenic Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EOMIFNE) and Pardalis P (Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Athens “Alexandra”) kindly supported this work.

| 1. | European Medicines Agency. Search results. [cited 3 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/search?search_api_fulltext=ulcerative%20colitis. |

| 2. | Burr NE, Gracie DJ, Black CJ, Ford AC. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2021;gutjnl-2021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ha C, Ullman TA, Siegel CA, Kornbluth A. Patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials do not represent the inflammatory bowel disease patient population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1002-7; quiz e78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D'Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Danese S, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Niezychowski W, Friedman G, Lawendy N, Yu D, Woodworth D, Mukherjee A, Zhang H, Healey P, Panés J; OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 1298] [Article Influence: 144.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taneja V, El-Dallal M, Haq Z, Tripathi K, Systrom HK, Wang LF, Said H, Bain PA, Zhou Y, Feuerstein JD. Effectiveness and Safety of Tofacitinib for Ulcerative Colitis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:e323-e333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liatsos C, Tzouvala M, Michalopoulos G, Giouleme O, Karmiris K, Kozompoli D, Mousourakis K, Kyriakos N, Giakoumis M, Striki A, Karoubalis I, Bellou G, Zacharopoulou E, Katsoula A, Kalogirou M, Viazis N. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in biologic-naive patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;37:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mukherjee A, Hazra A, Smith MK, Martin SW, Mould DR, Su C, Niezychowski W. Exposure-response characterization of tofacitinib efficacy in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: Results from a dose-ranging phase 2 trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:1136-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | European Medicines Agency. Xeljanz. [cited 8 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/xeljanz. |

| 9. | Ma C, Panaccione R, Xiao Y, Khandelwal Y, Murthy SK, Wong ECL, Narula N, Tsai C, Peerani F, Reise-Filteau M, Bressler B, Starkey SY, Loomes D, Sedano R, Jairath V, Bessissow T; Canadian IBD Research Consortium. REMIT-UC: Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Tofacitinib for Moderate-to-Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Canadian IBD Research Consortium Multicenter National Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:861-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yu A, Ha NB, Shi B, Cheng YW, Mahadevan U, Beck KR. Real-World Experience With Tofacitinib Dose De-Escalation in Patients With Moderate and Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:3115-3124.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Quirk D, Wang W, Nduaka CI, Mukherjee A, Su C, Sands BE. Efficacy and Safety of Extended Induction With Tofacitinib for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1821-1830.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Lukas M, Quirk D, Nduaka CI, Maller E, Lawendy N, Kayhan C, Fan H, Woodworth DA, Chan G, Su C. DOP43 Long-term efficacy of tofacitinib in patients who received extended induction therapy: results of the OCTAVE open study for tofacitinib delayed responders. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:S050-S052. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Sandborn WJ, Lawendy N, Danese S, Su C, Loftus EV Jr, Hart A, Dotan I, Damião AOMC, Judd DT, Guo X, Modesto I, Wang W, Panés J. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for treatment of ulcerative colitis: final analysis of OCTAVE Open, an open-label, long-term extension study with up to 7.0 years of treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:464-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Suzuki Y, Watanabe M, Matsui T, Motoya S, Hisamatsu T, Yuasa H, Tabira J, Isogawa N, Tsuchiwata S, Arai S, Hibi T. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy in Japanese Patients with Active Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2019;4:131-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vermeire S, Su C, Lawendy N, Kobayashi T, Sandborn WJ, Rubin DT, Modesto I, Gardiner S, Kulisek N, Zhang H, Wang W, Panés J. Outcomes of Tofacitinib Dose Reduction in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis in Stable Remission from the Randomised RIVETING Trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1130-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sharara AI, Su C, Modesto I, Mundayat R, Gunay LM, Salese L, Sands BE. Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib in Ulcerative Colitis Based on Prior Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Failure Status. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:591-601.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Panaccione R, Abreu MT, Lazariciu I, Mundayat R, Lawendy N, Salese L, Woolcott JC, Sands BE, Chaparro M. Persistence of treatment in patients with ulcerative colitis who responded to tofacitinib therapy: data from the open-label, long-term extension study, OCTAVE open. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:1534-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chiorean M, Daperno M, Lees CW, Bonfanti G, Soudis D, Modesto I, Deuring JJ, Edwards RA. Modeling of Treatment Outcomes with Tofacitinib Maintenance Therapy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Post Hoc Analysis of Data from the OCTAVE Clinical Program. Adv Ther. 2023;40:4440-4459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Panés J, D'Haens GR, Sands BE, Ng SC, Lawendy N, Kulisek N, Guo X, Wu J, Vranic I, Panaccione R, Vermeire S. Analysis of tofacitinib safety in ulcerative colitis from the completed global clinical developmental program up to 9.2 years of drug exposure. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/