CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Recurrent melena for nine days.

History of present illness

A 22-year-old married woman presented with melena (4-5 times/day) with dark red clots, accompanied by dizziness, which abruptly began nine days ago without identifiable triggers. The patient had one episode of syncope, accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The initial management at a local hospital included acid suppression, hemostatic agents, and blood transfusions. However, the hemoglobin levels of the patient fluctuated, reaching a nadir of 4.90 g/dL. The laboratory results revealed abnormally elevated serum β-hCG levels (2391.62 IU/L). However, the transvaginal ultrasound was normal. The gastroscopy revealed chronic non-atrophic gastritis. The contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) at the previous hospital revealed gallbladder folding, bile stasis, and a small amount of fluid in the pelvic cavity. Since the cause of the hemorrhage remained undetermined, the patient was referred to the hospital of the investigators. The transvaginal gynecologic ultrasound performed at the previous hospital revealed a normal uterus size, no evidence of pregnancy, and a small amount of fluid in the rectovesical fossa.

History of past illness

Thirteen months ago, the patient had an abortion due to fetal demise. The pathology of the curettage material from the uterine cavity revealed villi and decidua on microscopic examination.

Personal and family history

The patient had regular menstruation, and her menarche was achieved at the age of 13, with a menstrual period that lasted for 4-5 days, and occurred every 30 days. The last menstrual period was 19 days before the onset of the illness. The patient had no abdominal pain during the menstrual period, and no abnormal vaginal discharge. The patient had three pregnancies, and gave birth to two daughters. One of whom was aborted due to death in the womb before thirteen months. There was no significant family history.

Physical examination

The patient was conscious, but appeared weak and anemic. The heart rate was slightly elevated at 98 beats per minute. Other vital signs were stable. The physical examination of the heart, lungs and abdomen was unremarkable. The digital rectal examination revealed no palpable mass or tenderness, but brown bloodstains were observed on the glove. The routine gynecological examination revealed a normal vulva without any lesions. The vaginal mucosa was pink and rugated, with a minimal amount of white, non-malodorous discharge. The cervix appeared parous, was smooth and pink in color, and showed no signs of cervicitis, masses, or contact bleeding. On the bimanual examination, the uterus was anteverted, normal in size, mobile, and non-tender. Both adnexa were clear, with no palpable masses or tenderness.

Laboratory examinations

The routine blood examination revealed anemia (hemoglobin: 65 g/L), neutrophils 79%, lymphocytes 14%, absolute lymphocyte count of 0.90 × 109, red blood cell count of 2.42 × 1012, and normal platelets. The fecal routine examination revealed red blood cells 3-6/high-power field of view and white blood cells 6-10/high-power field of view. The serum hCG levels were elevated on multiple occasions, with a maximum value of 3553.59 IU/L. Tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and alpha-fetoprotein, were normal.

Imaging examinations

The abdominal CT with contrast enhancement revealed thickening and edema of the gastric wall. Furthermore, there was mild fluid accumulation in the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Moreover, there were low-density shadows in both adnexal regions, which were likely physiological follicles. No small intestinal lesions were detected on CT.

The gastroscopy detected chronic non-atrophic gastritis with bile reflux. The colonoscopy revealed that the large intestinal mucosa was normal. However, upon entering the terminal ileum, a large amount of dark red bloody fluid was observed, suggestive of small intestinal bleeding.

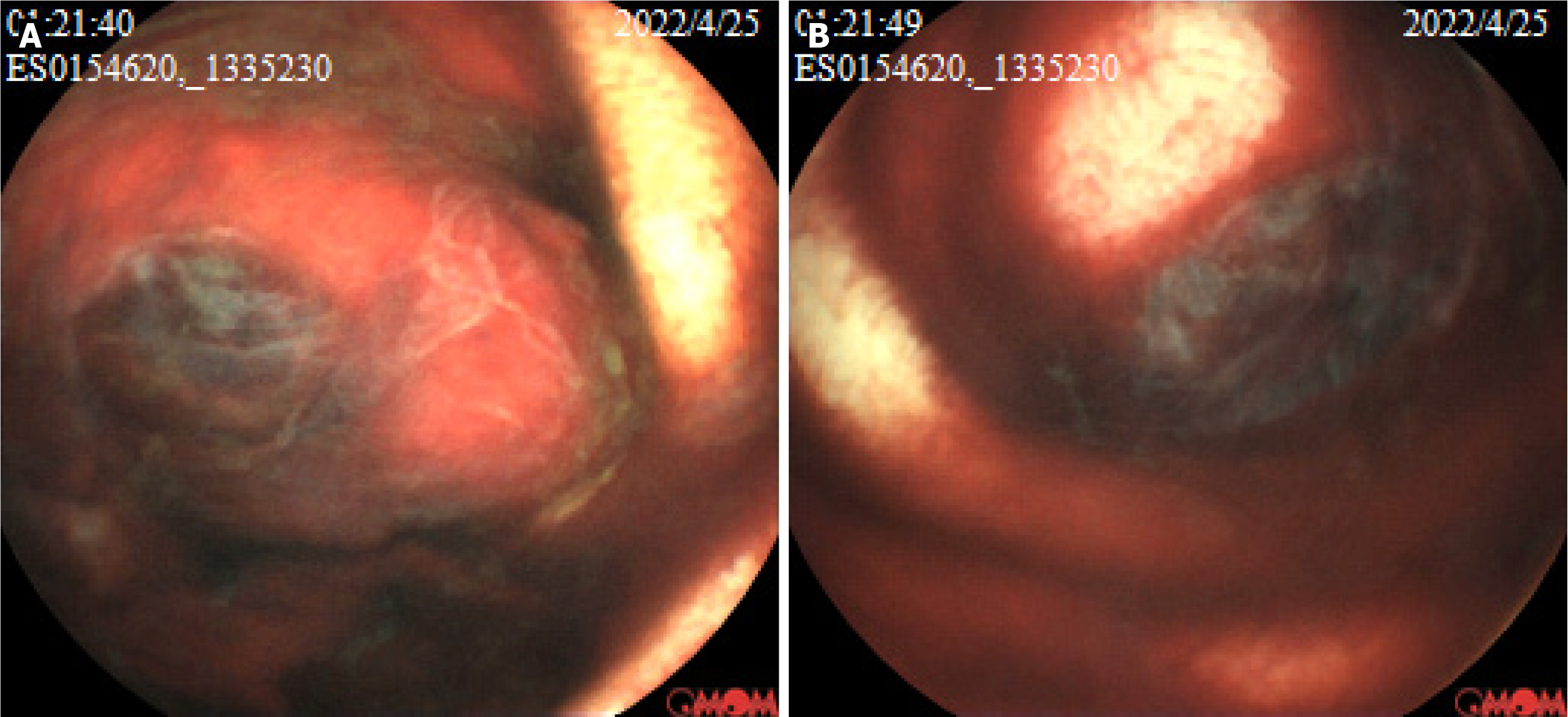

At one hour and 21 minutes after capsule ingestion, the capsule endoscopy revealed a protruding lesion with a diameter of approximately 1.50 cm and ulcer formation, and this was covered with blood scab in the small intestine, suggestive of neoplasm with bleeding (Figure 1). Based on the mucosal manifestations and operation time of the capsule endoscopy, it was speculated that the lesion was in the jejunum.

Figure 1 The capsule endoscopy examination shows a protruding lesion with a diameter of approximately 1.5 cm, ulcerations, and dark red bloodstains in the jejunum.

A and B: The morphological manifestations of the lesion from different perspectives.

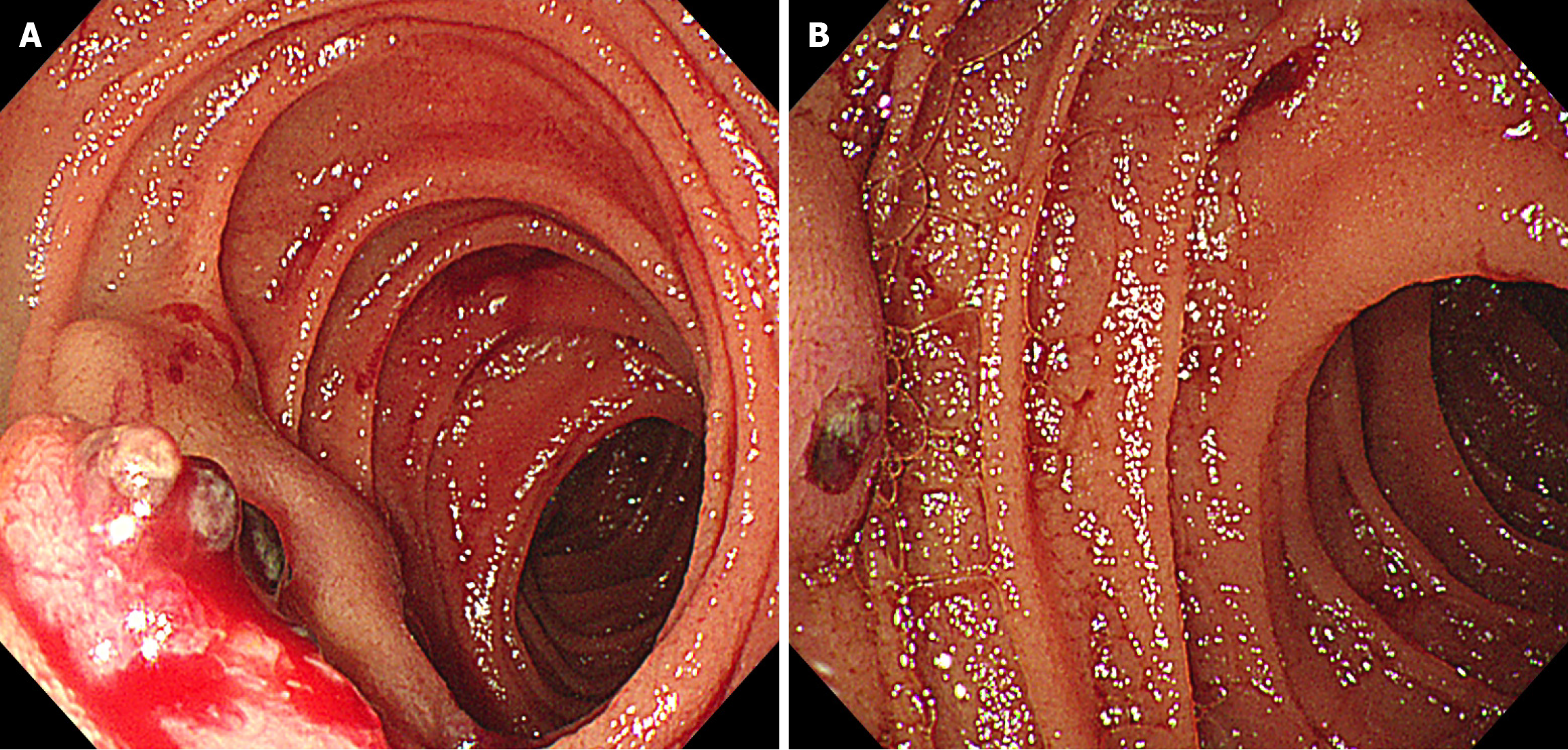

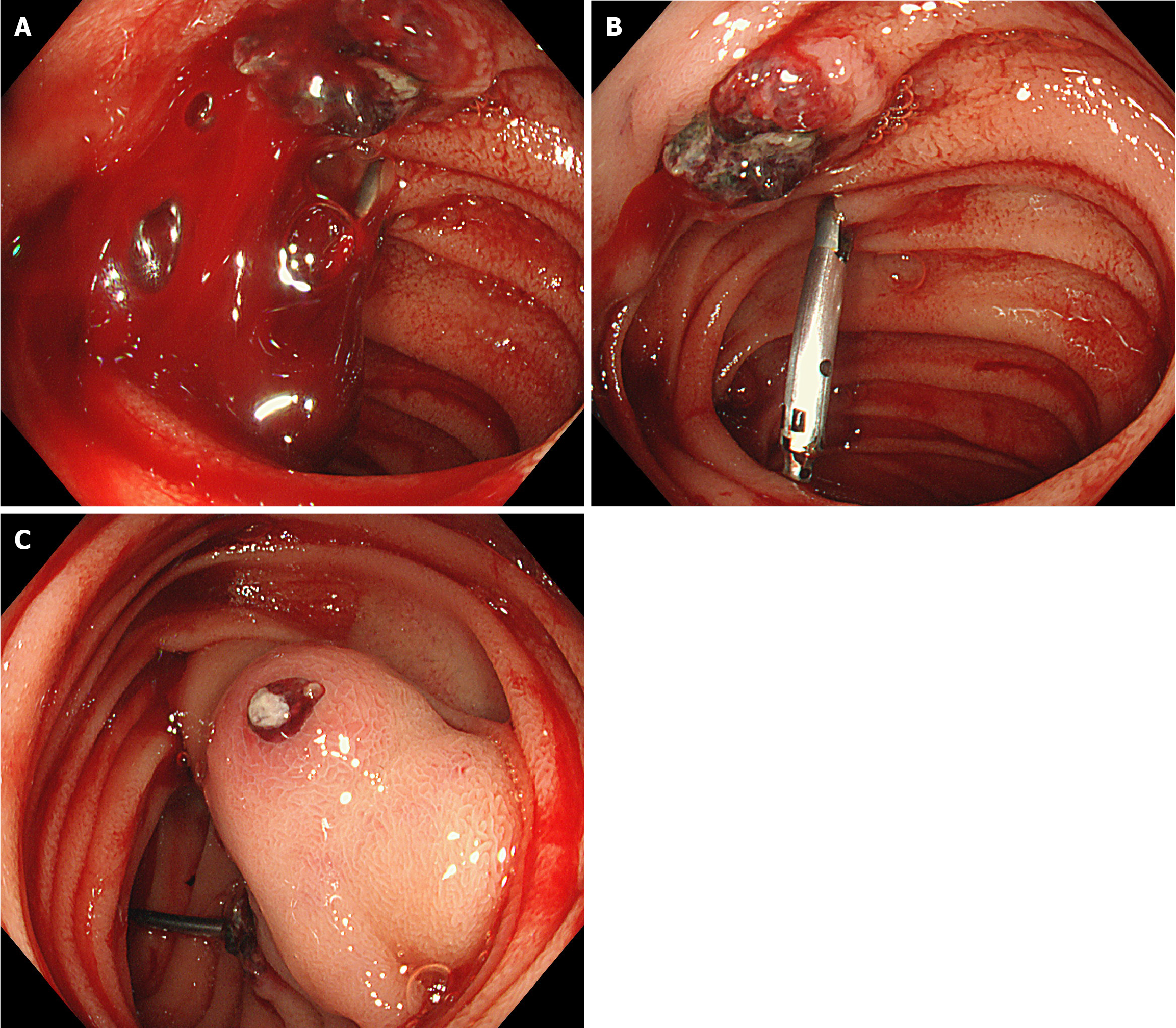

Next, the oral single-balloon enteroscopy revealed two adjacent submucosal protruding lesions, with erosion and blood clots on the surface of one lesion, and exposed vascular heads on the other lesion. Both lesions were relatively hard upon palpation. Titanium clips were placed on the oral side of the lesions for intraoperative localization (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The oral single-balloon enteroscopy reveals two adjacent protruding lesions with surface erosion, blood clots, and a small amount of blood.

A: The surface morphology of the labial lesion and the local morphology of the anal lesion; B: The surface morphology of the anal lesion.

No additional lesions were visible on the further evaluation by chest and head CT, Doppler echocardiography, and ultrasound examination of the thyroid gland and adrenal gland.

DISCUSSION

Small intestinal bleeding accounts for approximately 5%-10% of gastrointestinal bleeding[5]. The common causes include vascular malformations, Meckel’s diverticulum, Crohn’s disease, primary tumors, and metastatic tumors. Among these, small intestinal tumors are relatively rare, accounting for approximately 3%-6% of gastrointestinal tumors[1]. Most small bowel tumors are malignant, accounting for 1.10%-2.40% of gastrointestinal malignant tumors[1]. Although the incidence of small intestinal malignant tumors varies among different countries and regions, stromal tumors, lymphomas, adenocarcinomas, and neuroendocrine tumors are the most frequent[2-4].

Clinically, there may or may not be any symptoms. The most frequent symptoms are non-specific, such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The lack of typical clinical symptoms and low index of clinical suspicion make the diagnosis of small intestinal tumors particularly complex. It is usually recommended to perform abdominal imaging before endoscopy. Enhanced small intestinal CT or MRI can preliminarily assess the location, size, nature, and surrounding relationship of the tumor, and at the same time, assist in selecting the approach for small intestinal endoscopy. The detection rate of small intestinal lesions by capsule endoscopy (65.20%) is higher, when compared to traditional methods, which can guide the subsequent selection of the route of double-balloon endoscopy. The detection rate within 14 days after bleeding is significantly high (91% vs 34%)[5]. Capsule endoscopy can detect lesions in the small intestine that cannot be detected by other imaging examinations. However, enteroscopy can be used to perform biopsy for suspicious lesions, or provide endoscopic treatment in case of emergencies. Studies have revealed that most small intestinal tumors are in the jejunum. Therefore, if there is no clinical evidence indicating the location of the lesion, oral enteroscopy should be preferred to detect the lesion[6].

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasms (GTN) refer to malignant tumors that form through the abnormal proliferation of trophoblast cells in the blastoderm[7]. These are a series of biologically interrelated diseases that form a disease spectrum, which consists of four different clinical and pathological entities: Invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, placental site trophoblastic tumor, and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor[8].

Invasive mole is the most common form of GTN. Histologically, it is defined as trophoblastic cells that invade the myometrium and/or lymphatic vessels, and contain molar villi in the tumor or metastatic sites. The incidence of invasive mole varies in different regions. The incidence is highest in Southeast Asia and Middle Eastern countries, while its incidence is lowest in Europe and North America[9]. The pathogenesis of invasive mole is not yet fully understood. Approximately 95% of invasive mole cases are preceded by a mole. Other risk factors include pregnancy at an extreme reproductive age, history of spontaneous abortion, vitamin A deficiency, oral contraceptives, and paternal and environmental factors[10].

Invasive mole is characterized by extremely strong invasiveness to the blood vessels and tissues, and the lesion often undergoes necrosis and hemorrhage[11]. This can occur outside the uterus, typically through hematogenous dissemination[12]. Furthermore, metastatic foci appear early, and are widespread[11]. Studies have reported that 30% of patients with invasive mole already have metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis. The most common metastatic sites are the lungs (30%), vagina (30%), and liver (10%), and less frequently, the brain, bones, and breasts[13]. Small bowel is a rare site of metastasis.

The pathophysiology of distant metastasis of invasive mole to the small intestine is not yet fully clear. Wang et al[14] speculated that there are three possible pathways for choriocarcinoma to metastasize to the intestine: (1) Through the bloodstream to the liver, and subsequently to the intestine; (2) Implantation of tumor cells on the greater omentum through the blood stream, which finally metastasizes to the intestine through the bloodstream again, although the sequence of metastasis to the greater omentum and intestines remain unclear; and (3) Implantation of tumor cells directly on the greater omentum, which subsequently metastasizes to the liver and intestines through the bloodstream. The investigators considered that the above pathways are applicable to trophoblastic tumors with primary lesions, but not suitable for metastatic trophoblastic tumors without a clear primary lesion, as observed in the present case.

Due to its unique characteristic of the destruction of blood vessels, bleeding is the common feature of all metastatic sites[8]. The most common clinical symptoms of invasive mole are uncontrolled vaginal bleeding and uterine enlargement[13]. However, in rare cases of metastatic GTN, patients may solely present with symptoms of extrauterine metastases, while the primary lesion remains asymptomatic, as demonstrated in the present case. Due to the lack of clinical manifestations related to GTN, the initial symptoms often vary, making diagnosis difficult and prone to misdiagnosis.

The diagnosis of invasive mole is usually based on the hCG levels during the follow-up period after uterine curettage (continuous increase or no decrease). In very rare cases, the diagnosis is made after a spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, or full-term pregnancy[15]. The time interval between the last pregnancy and the occurrence of the tumor varies, and can be as long as several decades[16]. It has been observed that 10%-20% of patients have elevated or persistently elevated hCG levels[13]. The present patient had no history of hydatidiform mole removal. Instead, the condition occurred more than a year after a miscarriage of a stillborn fetus, which is a rare phenomenon. However, the hCG levels of the patient were not regularly monitored after the abortion.

Transabdominal ultrasound is regarded as the preferred imaging modality for the initial diagnosis of GTN, and for demonstrating its characteristic cystic appearance. It is also considered reliable for postoperative monitoring in patients with elevated serum β-hCG[17]. Transvaginal ultrasound can further provide detailed information, such as lesion echoes and adjacent relationships, and can distinguish the nature of most pelvic masses. CT and MRI are recommended for the detection of metastatic lesions and staging[18]. Intestinal metastatic lesions appear as thickened intestinal walls or soft tissue shadows in the CT abdomen. Lymph nodal enlargement has not been reported in these patients. The lesions can be observed as significantly enhanced nodular shadows on the CT angiography of mesenteric vessels, and contrast agent leakage indicates the existence of active bleeding[16].

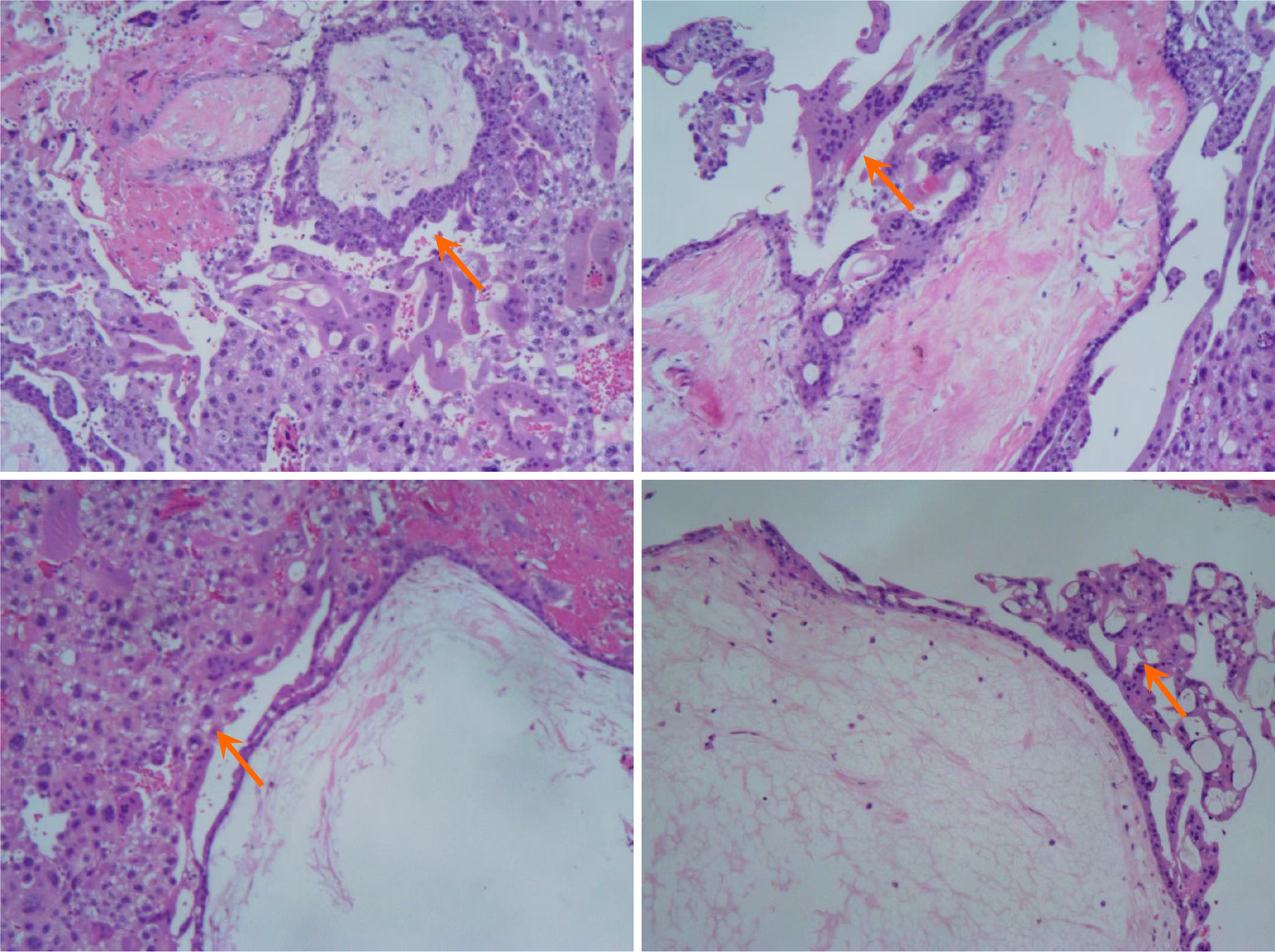

There are no specific features of invasive mole on endoscopy. Based on the enteroscopic findings in the present case and previous reports in the literature, the investigators speculate that it should present as a submucosal protrusion-like lesion, which may ulcerate locally and show signs of bleeding. Similarly, it was speculated that under endoscopic ultrasound, this may present as a submucosal hypoechoic lesion or multiple cystic lesions, with a small amount of blood flow signals visible under Doppler. However, in cases of jejunal or ileal lesions, endoscopic ultrasound cannot be used for tumor characterization. The role of fluorine-18-2-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography/CT is mainly limited to identifying individuals at high risk of developing GTN after a molar pregnancy[11,19]. The most used protein markers for confirming trophoblastic tumors are hCG, followed by Programmed death-1, inhibin, and GATA binding protein 3[20]. However, none of these markers can distinguish the histological origin of the tumor[21,22]. Pathology is the gold standard for diagnosing this disease. However, since this is a hemorrhagic disease, biopsy may lead to active bleeding, and endanger the patient’s life. It has been reported that genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis is a powerful tool to confirm the diagnosis and type of hydatidiform mole[23]. Therefore, genomic diagnosis of postoperative tissues can provide patients with personalized treatment plans, and optimize postoperative management.

Although invasive moles are aggressive and have a high metastasis rate, these are highly sensitive to chemotherapy, which is considered the preferred treatment. However, surgery is recommended in specific circumstances, such as in postmenopausal patients and cases of invasive moles with uncontrollable vaginal bleeding[24-26]. Similar to patients with metastasis to high-risk sites, such as the brain, liver, and kidneys, patients with invasive mole metastasis to the small intestine also require multi-modal treatment to achieve the best therapeutic effect. While undergoing chemotherapy, additional surgery may be necessary to control bleeding, and stabilize the condition for subsequent treatments[27]. The chemotherapy agents in GTN are decided based on the staging of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and the prognostic scoring system[28]. Both the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend single-agent chemotherapy, commonly with methotrexate or actinomycin D, as the first-line treatment of low-risk GTN (≤ 6)[28,29]. The latest research recommends the actinomycin D regimen as the first-line treatment, since this can increase the complete remission rate by 18.40% when compared to methotrexate[30]. In case of high-risk cases (≥ 7), combination chemotherapy is preferred, and several chemotherapy regimens are available. Among these, the EMA-CO regimen (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine) is the most used regimen[29].

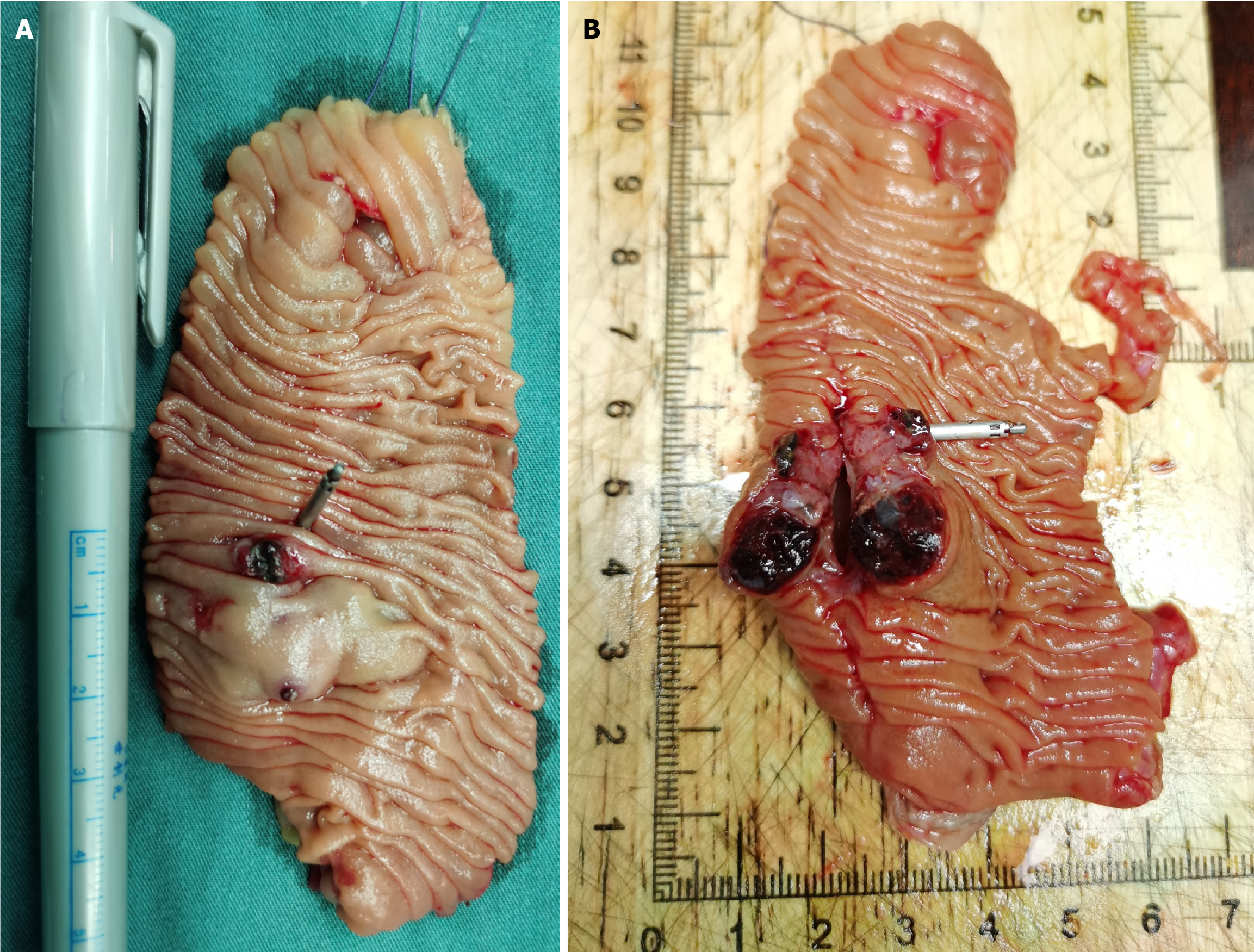

As mentioned above, chemotherapy is the first-line treatment for GTN. However, for the present case, chemotherapy was not performed after the biopsy confirmed the nature of the lesion, and surgery was chosen instead. The reasons were, as follows: (1) To further clarify the nature of the lesion: The biopsy pathology indicated the presence of trophoblastic cells. Combined with the patient’s medical history and other auxiliary examinations, it was a trophoblastic tumor. According to the guidelines, most trophoblastic tumors can be treated with chemotherapy based on risk stratification. However, rare types, such as placental site trophoblastic tumor and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor, have different treatment plans, prognoses, and follow-up strategies[29]. Misdiagnosis can lead to ineffective treatment and disease progression. Thus, further clarification of the pathological type is crucial. Some literature also suggests that when complete resection is possible, a histopathological diagnosis would be valuable[31]; (2) Most trophoblastic tumors respond well to chemotherapy, but a small number of cases may experience bleeding due to drug resistance or metastasis. Literature reports have mentioned metastasis to the vagina[32], liver[33], lungs[34], and gastrointestinal tract[35], leading to bleeding, which was managed by embolization or surgery[36]. Therefore, if the patient initially receives chemotherapy, risk of bleeding cannot be ruled out during the treatment; and (3) More importantly, the patient and the patient’s family were still traumatized by the previous bleeding crisis, and were afraid of another major hemorrhage. Literature suggests that surgery is recommended for the treatment of this disease, mainly for patients who are resistant to chemotherapy. Furthermore, literature reports have indicated that isolated drug-resistant GTN tumors can be cured by resection[37,38], and proposed indications for the successful surgical treatment of chemotherapy-resistant GTN, which includes good physical condition, localized tumor, no disease spread, and low hCG[39]. Therefore, despite the recommendation of chemotherapy by gynecological oncologists, based on the above reasons, the investigators agreed to perform the surgery. Recently, the concept of “neoadjuvant” surgery has been proposed, suggesting that surgery before chemotherapy can lead to cure, with less toxic single-agent chemotherapy or fewer cycles of combination chemotherapy for the patient[40]. Therefore, surgery was a good choice for the present patient. Studies have revealed that the future fertility, pregnancy, and offspring of patients cured of this disease are not affected[41]. The present patient was young and in good physical condition, the lesion was small and located in the small intestine, there was no evidence of metastasis in other parts, and the hCG level was not very high. Hence, the surgery cured the patient’s invasive mole, and the occurrence of this disease had no impact on the patient’s subsequent pregnancy.