Published online Oct 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i38.110557

Revised: July 14, 2025

Accepted: September 1, 2025

Published online: October 14, 2025

Processing time: 127 Days and 15.7 Hours

Esophageal cancer is a common malignancy, and endoscopic submucosal dissec

To analyze clinicopathological features, ESD efficacy, and prognostic factors of differentiated esophageal neoplasms to optimize management strategies.

A total of 264 Lesions in 245 patients treated with ESD (2014-2022) were retro

Early-stage cancers showed more surface vesicles than LGIN (P = 0.002). Intraepithelial papillary capillary loop (IPCL)-A predominated in LGIN, while IPCL-B2 was frequent in cancer (P < 0.001). Superficial carcinomas had higher vertical margin positivity (P < 0.001). Curative resection correlated with differentiation, body mass index (BMI), and symptoms; complications were linked to gender, BMI, and lesion size. The 3-, 5-, and 8-year disease-free survival rates were 96.8%, 91.7%, and 86.4%, respectively. Age [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.018] and prior esophageal cancer (HR = 3.050) predicted poorer survival.

Differentiated esophageal neoplasms exhibit distinct clinicopathological features. ESD provides durable efficacy, but high-risk patients (older age, prior cancer) require vigilant surveillance.

Core Tip: This study examined 264 cases of esophageal mucosal lesions in 245 patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) treatment. The study found that esophageal tumors with different levels of differentiation exhibit differences in clinical and pathological characteristics. While ESD demonstrated sustained efficacy, elderly patients and those with a history of esophageal cancer had poorer prognoses and required close follow-up.

- Citation: Zhang YM, Zhu N, Chen MY, Li FL, Qin B, Jiang J, Wang SH, Wu J, Quan XJ, Wang CY, Zheng Y, Zou BC. Clinical features of early esophageal neoplastic lesions at different stages and efficacy and prognosis after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(38): 110557

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i38/110557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i38.110557

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. China accounts for more than half of the global incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the most aggressive type and is particularly prevalent in Eastern Europe and Asia[2-4]. The lack of typical symptoms in the early stages results in a 5-year survival rate of only 10%-30%[1].

The pathological staging of esophageal cancer is based on the Vienna Classification and the Japanese Esophageal Cancer Classification Criteria[5]. Early-stage lesions include low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN), high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN), early-stage cancer (confined to the mucosal layer, with no lymph node or distant meta

In recent years, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has achieved remarkable efficacy as the treatment of choice for superficial infiltrative ESCC, with 5-year survival rates of up to 90%[6,7]. However, there is a paucity of long-term efficacy observations, and the factors affecting prognosis are still being explored. Additionally, the indications for ESD need to be improved. This study aimed to analyze the clinical features, endoscopic characteristics, long-term efficacy, and influencing factors of esophageal mucosal tumors (LGIN, HGIN, early-stage carcinoma, and superficial carcinoma) with different degrees of differentiation after ESD. The findings are expected to elucidate the pivotal factors influencing the pathogenesis and prognosis of esophageal cancer, thereby providing a foundation for the development of early diag

This study retrospectively included patients with esophageal lesions who underwent ESD at our center between June 2014 and October 2022. Clinical data were obtained from the hospital's electronic medical record system.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Early-stage esophageal neoplasia histologically confirmed by endoscopy and biopsy; (2) No evidence of lymph node involvement or distant metastasis on imaging, meeting the established indications for ESD; and (3) Written informed consent obtained prior to the procedure.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients meeting ESD indications but not undergoing the procedure; (2) Incomplete follow-up data; (3) Prior anticancer treatment before ESD (such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy); or (4) Severe comorbidities such as cardiovascular, hematological, or neuropsychiatric disorders, or significant hepatic or renal dysfunction.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2024 Ethics Review 032) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

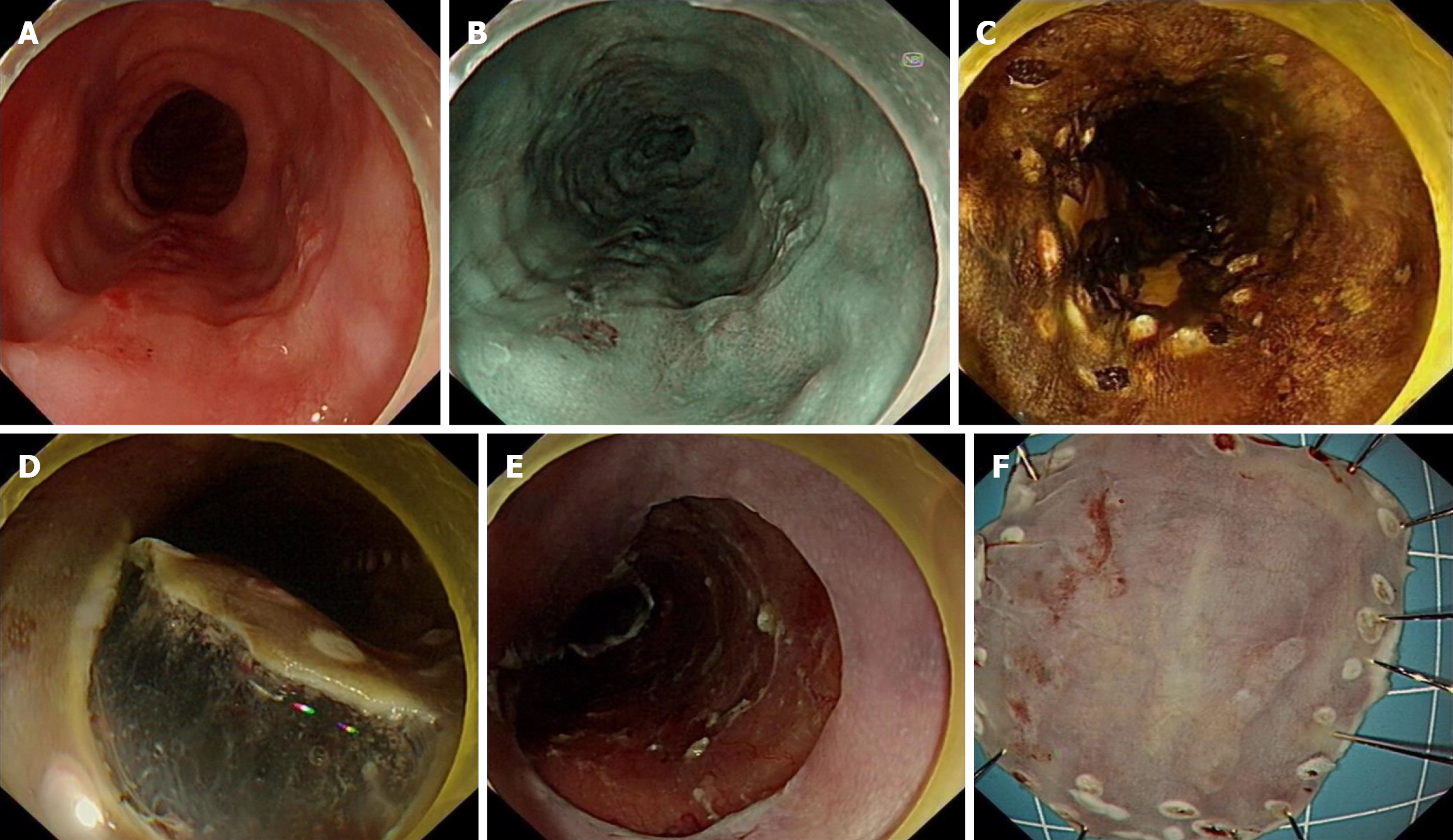

The lesion boundaries were identified by pigmented endoscopy and Lougol's iodine staining, and the lesion was marked by electrocoagulation 0.3 cm from the edge of the lesion and elevated by multiple submucosal injections of a mixture of indigo carmine, epinephrine, and saline. Submucosal dissection was then performed with a needle knife. ESD specimens were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours, sectioned at 2-mm intervals, and evaluated by an experienced pathologist. Pathological assessment included infiltration depth, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, histological subtype, diffe

Short-term outcomes: (1) Complications. Acute bleeding: Intraprocedural hemorrhage requiring hemostasis. Delayed bleeding: Clinically evident bleeding (> 48 hours post-ESD) confirmed by endoscopy. Perforation was defined as a state in which the esophageal wall was punctured, resulting in communication of the esophageal lumen with the thoracic or abdominal cavity, or the development of persistent postoperative fever and severe chest pain, assisted by the detection of free gas on thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) or the detection of an esophageal wall defect on gas

Long-term outcomes: (1) Local recurrence was defined as the development of early esophageal cancer at the ESD site of the primary lesion, whereas metastatic recurrence was defined as recurrence involving other organs or lymph nodes; and (2) Survival metrics: Overall survival (OS); disease-free survival (DFS); recurrence-metastasis-free survival (RMFS); disease-specific survival (DSS).

Follow-up schedule: Standardized protocol: Months 3/6/12: Endoscopy + CT/magnetic resonance imaging + tumor markers. Annually thereafter (or biannually for high-risk: SM2/NCR). Additional treatment after ESD was based on the European Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines for Histopathological Diagnostic Endoscopy[6]. Additional treatment (surgery or radiotherapy) was given for lymphovascular infiltrating lesions and lesions invading the deeper layers of the submucosa (> SM2). After multidisciplinary discussion, additional treatment was provided on a patient-by-patient basis, taking into account the patient's age, comorbidities, and preferences.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 and GraphPad Prism 10.0. Continuous variables were tested for normality via the Shapiro-Wilk test, presented as mean ± SD (normal) or median (interquartile range) (non-normal), and compared using ANOVA/t-test or Kruskal-Wallis/Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Categorical variables were expressed as n (%), compared by χ2 test, with Fisher's exact test used for expected frequencies < 5. Ordinal variables were analyzed via Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons. Multivariate logistic regression included variables with P < 0.05 from univariate analysis, using stepwise backward elimination (removal probability = 0.10) and Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness-of-fit. Survival outcomes were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test for group comparisons. Cox proportional hazards regression was used for multivariable survival analysis (Schoenfeld residuals to verify proportional hazards assumption), with hazard ratio (HR) and 95%CI reported. Sensitivity analysis validated the robustness of the results by excluding cases of superficial cancer. Statistical significance was set at two-tailed P < 0.05.

A total of 245 patients with 264 Lesions were examined. The mean age of the patients was 62.3 ± 7.8 years (range 44-86 years), of which 69.8% (171/245) were male.

We analyzed and counted the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of early esophageal cancer with different degrees of differentiation, and there were no significant differences.

Endoscopic lesions were predominantly erythema and mucosal roughness. Surface vesiculation was significantly higher in patients with early carcinoma than in those with LGIN (33.8% vs 8.5%, P = 0.002). Submucosal vascular blurring or disappearance was significantly less in patients with LGIN than in those with HGIN and early carcinoma (18.6% vs 1.4%, 13.8% vs 1.4%, P = 0.002; Table 1).

| LGIN (n = 71) | HGIN (n = 97) | Early cancer (n = 65) | Superficial cancer (n = 31) | P value | |

| Gender | 0.818 | ||||

| Male | 53 (74.6) | 71 (73.2) | 44 (67.7) | 22 (71.0) | |

| Female | 18 (25.4) | 26 (26.8) | 21 (32.3) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Age (years) | 61.34 ± 6.94 | 62.8 ± 8.10 | 62.91 ± 7.66 | 61.84 ± 9.06 | 0.578 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 8 (11.3) | 10 (10.3) | 6 (9.2) | 1 (3.2) | 0.676 |

| Hypertension | 20 (28.2) | 24 (24.7) | 20 (30.8) | 6 (19.4) | 0.642 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 10 (14.1) | 14 (14.4) | 7 (10.8) | 3 (9.7) | 0.873 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 8 (11.3) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (7.7) | 1 (3.2) | 0.167 |

| Respiratory diseases | 7 (9.9) | 13 (13.4) | 6 (9.2) | 8 (25.8) | 0.141 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 38 (31.7) | 46 (38.3) | 26 (40.0) | 10 (32.3) | 0.174 |

| Barrett's esophagus | 3 (4.2) | 3 (3.1) | 4 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 0.575 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 49 (69.0) | 64 (66.0) | 43 (66.2) | 23 (74.2) | 0.836 |

| Hiatal hernia | 5 (7.0) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0.315 |

| Previous tumor history | 7 (9.9) | 12 (12.4) | 8 (12.3) | 4 (12.9) | 0.943 |

| Previous esophageal cancer history | 1 (1.4) | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | 0.195 |

| Smoking history | 28 (39.4) | 48 (49.5) | 31 (47.7) | 19 (61.3) | 0.225 |

| Alcohol history | 22 (31.0) | 32 (33.0) | 13 (20.0) | 13 (41.9) | 0.133 |

| Family history | 17 (23.9) | 12 (12.4) | 5 (7.7) | 5 (16.1) | 0.055 |

| Accompanying symptoms | |||||

| Dysphagia | 9 (12.7) | 13 (13.4) | 9 (13.8) | 8 (25.8) | 0.392 |

| Retrosternal pain | 16 (22.5) | 26 (26.8) | 10 (15.4) | 9 (29.0) | 0.314 |

| Weight loss | 10 (14.1) | 12 (12.4) | 8 (12.3) | 2 (6.5) | 0.716 |

| Other | 40 (56.3) | 51 (52.6) | 41 (63.1) | 13 (41.9) | 0.248 |

| White light endoscopic | |||||

| Redness | 48 (67.6) | 72 (74.2) | 48 (73.8) | 21 (67.7) | 0.735 |

| Whitening | 11 (15.5) | 16 (16.5) | 9 (13.8) | 4 (12.9) | 0.973 |

| Roughness | 52 (73.2) | 82 (84.5) | 47 (72.3) | 25 (80.6) | 0.194 |

| Erosion | 6 (8.5)c | 16 (16.5) | 22 (33.8)a | 5 (16.1) | 0.002 |

| Nodule | 2 (2.8) | 7 (7.2) | 10 (15.4) | 5 (16.1) | 0.024 |

| White coating | 7 (9.9) | 13 (13.4) | 11 (16.9) | 3 (9.7) | 0.640 |

| Submucosal vascular blurring or loss | 1 (1.4)b,c | 18 (18.6)a | 9 (13.8)a | 3 (9.7) | 0.002 |

Intraepithelial papillary capillary loop (IPCL) staging is based on the AB staging criteria of the Japanese Society of Endoscopy[8]. Compared with patients with HGIN, early cancer, and superficial cancer, lesions in patients with LGIN were more likely to be IPCL-A type (9.3% vs 29.6%, 3.1% vs 29.6%, 0% vs 29.6%, P < 0.001), and lesions in early cancer and superficial cancer were more likely to be IPCL-B2 type (44.6% vs 4.2%, 45.2% vs 4.2%, P < 0.001; Table 2).

Compared to patients with LGIN, patients with superficial carcinoma had a higher rate of positive horizontal (19.4% vs 0%, P = 0.001) and vertical (29.0% vs 0%, P < 0.001) margins. Patients with HGIN, early-stage carcinoma, and superficial carcinoma had longer longitudinal diameter of lesions (H = 39.511, P < 0.001) and wider circumferential extent (H = 25.813, P < 0.001). Early-stage and superficial carcinomas infiltrated deeper than LGIN (H = -118.338, P < 0.001; H =

| LGIN (n = 71) | HGIN (n = 97) | Early cancer (n = 65) | Superficial cancer (n = 31) | P value | |

| Lesion location | 0.033 | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | 18 (25.4)b | 9 (9.3)a | 10 (15.4) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Middle 1/3 | 36 (50.7) | 48 (49.5) | 34 (52.3) | 14 (45.2) | |

| Lower 1/3 | 17 (23.9) | 40 (41.2) | 21 (32.3) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Lesion length (cm) | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 46 (64.8)b,c,d | 25 (25.8)a | 12 (18.5)a | 9 (29.0)a | |

| > 2 and < 5 | 22 (31.0)b,c | 58 (59.8)a | 37 (56.9)a | 14 (45.2) | |

| ≥ 5 | 3 (4.2)c,d | 14 (14.4) | 16 (24.6)a | 8 (25.8)a | |

| Circumferential extent | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 1/2 | 59 (83.1)b,c,d | 60 (61.9)a | 31 (47.7)a | 17 (54.8)a | |

| ≥ 1/2 and < 3/4 | 12 (16.9) | 27 (27.8) | 16 (24.6) | 3 (9.7) | |

| ≥ 3/4 | 0 (0)b,c,d | 10 (10.3)a,c,d | 18 (27.7)a,b | 11 (35.5)a,b | |

| Invasion depth | < 0.001 | ||||

| M1 | 71 (100)c,d | 97 (100)c,d | 0 (0)a,b | 0 (0)a,b | |

| M2 | 0 (0)c | 0 (0)c | 36 (55.4)a,b,d | 1 (3.2)c | |

| M3 | 0 (0)c,d | 0 (0)c,d | 29 (44.6)a,b,d | 5 (16.1)a,b,c | |

| SM1 | 0 (0)d | 0 (0)d | 0 (0)d | 23 (74.2)a,b,c | |

| SM2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Vertical margin | < 0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0)d | 0 (0)d | 4 (6.2) | 5 (16.1)a,b | |

| Negative | 71 (100)d | 97 (100) d | 61 (93.8) | 26 (83.9)a,b | |

| Horizontal margin | 0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0)d | 5 (5.2) | 6 (9.2) | 6 (19.4)a | |

| Negative | 71 (100)d | 92 (94.8) | 59 (90.8) | 25 (80.6)a | |

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.364 | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Negative | 71 (100) | 97 (100) | 64 (98.5) | 31 (100) | |

| Vascular invasion | < 0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0)d | 0 (0)d | 0 (0)d | 8 (25.8)a,b,c | |

| Negative | 71 (100)d | 97 (100)d | 65 (100)d | 23 (74.2)a,b,c | |

| Multiple lesions | 17 (23.9)b | 7 (7.2)a | 8 (12.3) | 6 (19.4) | 0.015 |

| Paris classification | 0.001 | ||||

| 0-I | 3 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 0-IIa | 4 (5.6) | 11 (11.3) | 10 (15.4 ) | 3 (9.7) | |

| 0-IIb | 59 (83.1)c,d | 74 (76.3) | 42 (64.6)a | 18 (58.1)a | |

| 0-IIc | 5 (7.0) | 9 (9.3) | 6 (9.2) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Mixed type | 0 (0)c,d | 3 (3.1)d | 7 (10.8)a | 7 (22.6)a,b |

All patients with LGIN met the absolute indications for ESD, whereas all superficial cancers exceeded the absolute indications; superficial cancers were more likely to exceed the absolute indications for ESD compared to early-stage cancers (40.0% vs 0%, P < 0.001) The R0 rate of early-stage and superficial cancers was significantly lower compared to LGIN (86.2% vs 0%, 71.0% vs 0%, P < 0.001), and the NCR rate (15. 4% vs 0%, 45.2% vs 0%) and the incidence of postoperative stenosis (24.6% vs 4.2%, 35.5% vs 4.2%) were significantly higher (P < 0.001). Superficial carcinoma had a lower R0 rate (71.0% vs 94. 8%) and a higher rate of NCR than HGIN had (45.2% vs 5.2%, both P < 0.001). The proportion of intrinsic muscle layer injury was significantly higher in superficial carcinoma than in LGIN (4.2% vs 29.0%, P = 0.008).

Postoperative body mass index (BMI) was significantly lower in patients with superficial carcinoma than in LGIN (18.94 vs 24.22, H = 79.192), HGIN (18.94 vs 23.04, H = 51.243) and early-stage carcinoma (18.94 vs 23.53, H = 52.355) (all P < 0.05). Postoperative follow-up BMI was also lower in HGIN (H = 27.949) and early cancer (H = 26.838) than in LGIN (both P < 0.05). Patients with early-stage and superficial cancers had a higher incidence of long-term adverse outcomes (recurrence, metastasis, and death) (12.3% vs 2.8%, 19.4% vs 2.8%, P = 0.006) and an increased risk of recurrence (6.2% vs 0%, 12.9% vs 0%, P = 0.014; Table 4).

| LGIN (n = 71, 26.9%) | HGIN (n = 97, 36.7%) | Early cancer (n = 65, 24.6%) | Superficial cancer | P value | |

| Short-term outcomes | |||||

| Absolute indication | 71 (100)b,c,d | 88 (90.7)a,c,d | 26 (40.0)a,b,d | 0 (0)a,b,c | < 0.001 |

| R0 resection | 71 (100)c,d | 92 (94.8)d | 56 (86.2)a | 22 (71.0)a,b | < 0.001 |

| CR | 71 (100)c,d | 92 (94.8)d | 55 (84.6)a,d | 16 (51.6)a,b,c | < 0.001 |

| Muscle layer injury | 3 (4.2)d | 13 (13.4) | 8 (12.3) | 9 (29.0)a | 0.008 |

| Complications | 4 (5.6)c,d | 17 (17.5) | 16 (24.6)a | 12 (38.7)a | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.363 |

| Perforation | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 0.198 |

| Stricture | 3 (4.2)c,d | 14 (14.4) | 16 (24.6)a | 11 (35.5)a | < 0.001 |

| Long-term outcomes | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.22 (22.76-25.60)b,c,d | 23.04 (20.95-24.95)a | 23.53 (20.57-24.73)a | 21.97 (18.94-23.00)a | < 0.001 |

| Adverse outcomes | 1 (2.8)c,d | 6 (6.2)d | 8 (12.3)a | 6 (19.4)a,b | 0.006 |

| Recurrence | 0 (0)c,d | 3 (3.1)d | 4 (6.2)a | 4 (12.9)a,b | 0.014 |

| Metastasis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0.802 |

| Mortality | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.1) | 5 (7.7) | 2 (6.5) | 0.133 |

| Multiple primary cancers | 11 (15.5) | 13 (13.4) | 11 (16.9) | 5 (16.1) | 0.933 |

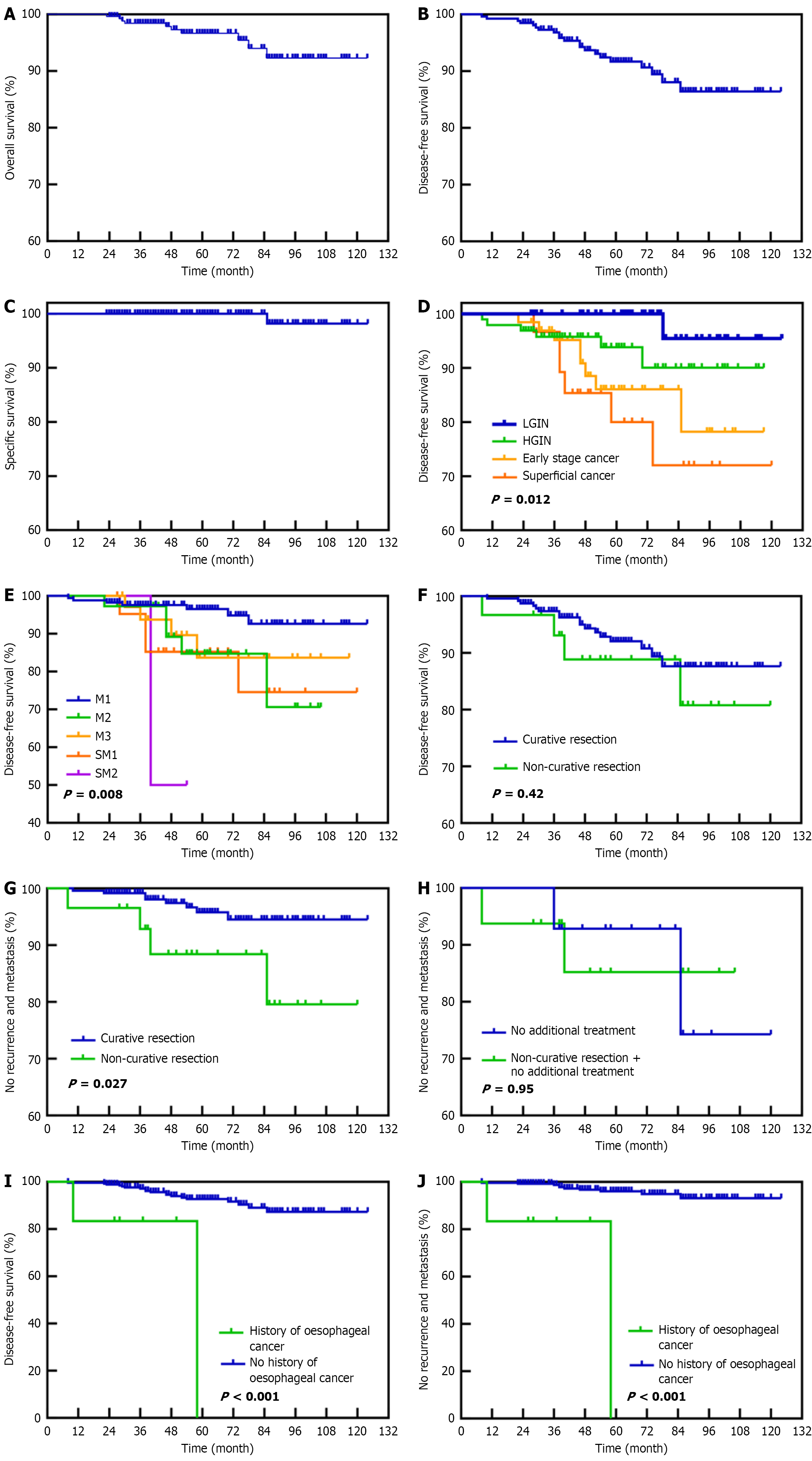

Degree of differentiation [HGIN odds ratio (OR): 7.527, early-stage cancer OR: 2.545] was significantly associated with R0 resection. Degree of differentiation (early-stage cancer OR: 3.722, HGIN OR: 11.460), BMI (OR: 1.205), and preoperative symptoms (retrosternal pain OR: 0.340) were considered independent risk factors for CR (Table 5). Sex (female OR 2.768), BMI (OR 0.837), lesion length (≥ 5 cm: OR 4.411), > 3/4 of the annulus circumference (OR: 5.820) and R0 resection (OR 0.288) were independent risk factors for complications. Sex (female OR: 2.450), lesion length > 5 cm (OR: 5.833), > 3/4 of the esophageal circumference (OR: 3.472), and postoperative stenosis prophylaxis (OR: 4.161) were independent risk factors for esophageal stenosis after ESD (Table 6). Age (HR: 1.018) and prior esophageal cancer (HR: 3.050) were significantly associated with poor prognosis. Prior esophageal cancer (HR: 18.230) and depth of lesion invasion (SM2 HR: 30.213) were significantly associated with recurrent metastasis (Table 7 and Figure 2).

| Variable | Category | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI |

| CR | ||||

| Differentiation degree | HGIN | < 0.001 | 11.460 | 3.404-38.582 |

| Early cancer | 0.014 | 3.722 | 1.312-10.564 | |

| Superficial cancer | 1 | |||

| Retrosternal pain | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.036 | 0.340 | 0.124-0.931 | |

| BMI | 0.032 | 1.205 | 1.016-1.430 | |

| R0 resection | ||||

| Differentiation degree | HGIN | < 0.001 | 7.527 | 2.294-24.695 |

| Early cancer | 0.080 | 2.545 | 0.893-7.255 | |

| Superficial cancer | 1 |

| Variable | Category | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI |

| Complications | ||||

| Gender | Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.009a | 2.320 | 0.838-6.423 | |

| BMI | - | 0.008a | 0.837 | 0.734-0.956 |

| Lesion length (cm) | ≤ 2 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 0.021a | 4.411 | 1.251-15.548 | |

| Circumferential extent | < 1/2 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 3/4 | < 0.001a | 5.820 | 2.180-15.537 | |

| R0 resection | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.023a | 0.288 | 0.098-0.841 | |

| Esophageal stenosis | ||||

| Gender | Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.032a | 2.450 | 1.078-5.571 | |

| Lesion length (cm) | ≤ 2 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 0.026a | 5.833 | 1.232-27.626 | |

| Circumferential extent | < 1/2 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 3/4 | 0.033a | 3.472 | 1.104-10.922 | |

| Stenosis prevention | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.006a | 4.161 | 1.490-11.615 |

The pathogenesis of ESCC is influenced by a variety of factors, including genetic susceptibility and environmental stimuli[2,9,10]. The precursor lesion of ESCC is dysplasia of the esophageal epithelium, ranging from LGIN to HGIN, which may eventually progress to invasive carcinoma. It has been reported that about 23% of LGINs progress to HGINs or invasive carcinoma within 5 years, while about 70% of HGINs progress to invasive carcinoma within 5 years. However, about 37% of precancerous lesions regress spontaneously within 5 years, and not all precancerous lesions progress, which may be closely related to genetic and environmental factors[11].

This study found no significant differences in demographics, comorbidities, or symptoms among patients with ESCC of varying differentiation. However, atrophic gastritis was more common and is strongly associated with increased ESCC and gastric cancer risk[10]. Smoking and alcohol consumption significantly raised the incidence of superficial carcinoma, aligning with previous findings[12]. LGIN detection was higher in individuals with a family history of esophageal cancer; likely due to active screening. The most common symptom was nonspecific upper gastrointestinal discomfort. Therefore, early endoscopic examination with targeted biopsy is essential for patients with risk factors, such as atrophic gastritis, gastrointestinal symptoms, family history, smoking, and alcohol use, to enable early detection and reduce mortality.

With increasing lesion differentiation, the longitudinal and circumferential extent, invasion depth, muscular involve

ESD is an efficient and minimally invasive resection technique with a high resection rate. En bloc resection rate, R0 resection rate, and CR rate were 100%, 91.3%, and 88.6%, respectively, The CR rate was significantly higher than in previous studies; likely due to accurate preoperative evaluation and advancing ESD techniques in China, further validating the method's effectiveness. There were 30 patients with NCR (11.4%). Fourteen of those patients received additional treatment, including esophagectomy in five and radical chemoradiotherapy in 10. One patient underwent esophagectomy followed by additional chemoradiotherapy. Of the patients who received additional chemoradiotherapy, five experienced recurrence. One patient achieved remission after repeated ESD, one achieved remission after continued radical chemoradiotherapy, and three achieved a cure after esophagectomy. The remaining 16 patients underwent endoscopic monitoring. Some did not meet the CR criteria in the Japanese Esophageal Guidelines but had pathological findings indicating R0 resection. Others were older, had severe comorbidities, or had other reasons. Of the patients who did not receive additional treatment, two had recurrence (one with neck lymph node metastasis who subsequently died, and one who was relieved after undergoing ESD again), and 14 showed no abnormalities during follow-up. There were no ESCC-related deaths post-CR surgery, and the RMFS was significantly higher than in NCR patients. Follow-up observations are ongoing for these patients. The possibility of recurrence in NCR patients despite additional radiotherapy and chemotherapy suggests that postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy cannot completely prevent disease recurrence, which is consistent with previous studies[13]. Further large-scale studies are needed to explore whether adjuvant radiotherapy can reduce the recurrence rate in NCR patients after ESD. Previous studies have demon

This study found that the degree of tumor differentiation, retrosternal pain, and BMI were independent risk factors for NCR. Compared with superficial cancer, the CR rate was significantly higher in LGIN, HGIN, and early-stage cancer. The incidence of NCR and non-R0 resection increased with increasing lesion differentiation, deeper invasion, and higher risk of lymphatic metastasis. In particular, the presence of retrosternal pain may indicate that the tumor has invaded deeper tissues or nerves, and the extent of the lesion may be beyond the expected resection range of ESD. In addition, patients with a high BMI may impair the operator's ability to accurately assess the lesion boundaries due to limited exposure of the surgical field, thus increasing the risk of NCR. However, the differences between the results of this and some previous studies may be related to the different pathological stratification of the study population and the types of confounding factors. Based on these findings, it is recommended that in patients with retrosternal pain, high preoperative pathological differentiation and obesity, the indications for ESD should be evaluated more cautiously, and the extent of resection should be carefully assessed to avoid overtreatment or underestimation of the extent of tumor infiltration.

ESD perioperative complications such as bleeding (1.1%) and perforation (0.8%) can be effectively controlled with medication and endoscopy, and no deaths occurred. Due to the low event numbers, risk factor analysis for these compli

The cumulative OS at 3, 5, and 8 years in the study cohort was 98.4%, 96.6%, and 92.3%, respectively. DFS was 96.8%, 91.7% and 86.4%, and RMFS was 98.4%, 95.0% and 92.1%. The 10-year local recurrence metastasis rate with DSS was 4.5% and 99.6%, respectively. Five-year DFS rates for CR and NCR patients were 92.0% and 88.9%, respectively. A total of 10 patients died: One from ESCC, five from second primary tumors (3 Lung, 1 each esophageal and gastric) and four from lung cancer. Significant differences in DFS and RMFS were observed between lesions of varying differentiation invasion depth, with superficial carcinoma (especially invasive to SM2) showing the worst prognosis. Recurrent metastases increased with higher lesion differentiation and depth of invasion, consistent with previous studies[15,26]. Additionally, the study found a higher incidence of secondary lung cancer in esophageal cancer patients, reinforcing the need for regular monitoring for second primary malignancies post-treatment[16,17].

In this study, the mean time to esophageal cancer recurrence was 41.0 ± 23.5 months (range: 8-85 months), with 81.8% of recurrences occurring within 5 years post-surgery. Recurrence rates significantly declined beyond 5 years[27], so a minimum of 5 years postoperative follow-up is recommended, as well as increased surveillance for 2-4 years. In Cox multivariate regression, each additional year of age was associated with a 1.8% increase in the risk of DFS (HR = 1.018), suggesting that advanced age may affect prognosis through immune aging or DNA repair capacity[28]. Patients with a history of esophageal cancer had a recurrence risk approximately three times higher than those without a history of the disease (HR = 3.05), and clinical follow-up strategies should be strengthened. To address potential bias from the small sample size of superficial carcinomas (n = 31), a sensitivity analysis excluding these cases was performed (Table 8). Notably, the HR for age (1.097 vs 1.018) and prior cancer history (10.429 vs 3.050) remained significant or even increased, confirming the robustness of these associations. These findings underscore the need for intensified surveillance in elderly patients and those with prior malignancies, regardless of lesion stage. To further eliminate the impact of esophageal cancer-specific mortality on the results, the analysis showed that the independent risk factors for RMFS were a history of esophageal tumors (HR = 18.230) and a lesion infiltration depth of SM2. Patients with a history of esophageal cancer have an 18.23-fold higher risk of recurrence and metastasis than those without a history of the disease (HR = 18.230), suggesting that residual micrometastases or chronic inflammation may drive recurrence[29]. Increased depth of invasion is significantly associated with a marked increase in lymph node metastasis rate, suggesting that SM2 Lesions may have a higher metastatic potential[30], with a significantly increased recurrence and metastasis rate. Two patients with stage SM2 invasive esophageal cancer developed choroidal invasion after ESD. One patient achieved long-term remission with adjuvant radiotherapy, while the other patient did not experience recurrence after esophagectomy. These cases suggest ESD combined with radiotherapy might be a viable option for SM2 Lesions, although larger studies are needed to confirm safety and efficacy. Consistent with previous studies[31], patients with NCR have a significantly increased risk of recurrence and metastasis. Such patients are recommended to undergo enhanced endoscopic monitoring 3-6 months after surgery and receive an individualized assessment of the need for adjuvant therapy (e.g., radiotherapy for patients not eligible for surgery). In addition, this study supports increased screening of people over 40 years of age or with a history of tumors, especially esophageal cancer, for early diagnosis and treatment to improve long-term survival and reduce the burden on society.

Our study revealed significant differences in the epidemiological and endoscopic characteristics of esophageal mucosal tumors with varying degrees of differentiation, highlighting the importance of accurate preoperative diagnosis in selecting appropriate ESD indications. ESD demonstrated high CR and R0 resection rates for early esophageal cancer, with excellent DSS and favorable long-term outcomes. Although bleeding and perforation risks are low, esophageal stricture remains a major challenge. Patients with NCRs had significantly lower DFS, necessitating further treatment strategies, as no clear consensus exists on whether surgery or radiotherapy is preferable. Additionally, esophageal cancer patients face a higher risk of death from other malignancies and recurrence within 5 years. Thus, close postoperative surveillance is essential for early detection of second primary tumors and recurrence.

This study had several limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective study, selection bias may be present despite strict inclusion criteria, limiting the generalization of the findings. Second, small subgroup sizes (e.g., superficial car

This study systematically analyzed the clinicopathological characteristics and long-term outcomes of early esophageal neoplastic lesions with different degrees of differentiation treated by ESD. ESD demonstrated favorable efficacy and safety, particularly in patients with LGIN and HGIN. Poor differentiation, retrosternal pain, and elevated BMI were identified as independent predictors of NCR, underscoring the importance of individualized preoperative assessment. Although adjuvant therapy may benefit patients with NCR, recurrence remains a concern, especially in those with SM2 invasion or a history of esophageal cancer. Post-ESD strictures were more common in female patients and those with long or ≥ 3/4 of the annulus circumference lesions. While prophylactic interventions such as steroid therapy and balloon dilation may reduce stricture severity, their efficacy requires further validation. Given the potential risk of recurrence and secondary malignancies, long-term and structured surveillance is essential. These findings support the refinement of risk-stratified treatment and follow-up strategies for early-stage esophageal cancer.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68630] [Article Influence: 13726.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Codipilly DC, Wang KK. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2022;51:457-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Waters JK, Reznik SI. Update on Management of Squamous Cell Esophageal Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24:375-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhu H, Ma X, Ye T, Wang H, Wang Z, Liu Q, Zhao K. Esophageal cancer in China: Practice and research in the new era. Int J Cancer. 2023;152:1741-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mine S, Tanaka K, Kawachi H, Shirakawa Y, Kitagawa Y, Toh Y, Yasuda T, Watanabe M, Kamei T, Oyama T, Seto Y, Murakami K, Arai T, Muto M, Doki Y. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 12th Edition: Part I. Esophagus. 2024;21:179-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Bastiaansen BAJ, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, Bourke MJ, Esposito G, Lemmers A, Maselli R, Messmann H, Pech O, Pioche M, Vieth M, Weusten BLAM, van Hooft JE, Deprez PH, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2022;54:591-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 119.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kitagawa Y, Ishihara R, Ishikawa H, Ito Y, Oyama T, Oyama T, Kato K, Kato H, Kawakubo H, Kawachi H, Kuribayashi S, Kono K, Kojima T, Takeuchi H, Tsushima T, Toh Y, Nemoto K, Booka E, Makino T, Matsuda S, Matsubara H, Mano M, Minashi K, Miyazaki T, Muto M, Yamaji T, Yamatsuji T, Yoshida M. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2022 edited by the Japan esophageal society: part 1. Esophagus. 2023;20:343-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oyama T, Inoue H, Arima M, Momma K, Omori T, Ishihara R, Hirasawa D, Takeuchi M, Tomori A, Goda K. Prediction of the invasion depth of superficial squamous cell carcinoma based on microvessel morphology: magnifying endoscopic classification of the Japan Esophageal Society. Esophagus. 2017;14:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ko KP, Huang Y, Zhang S, Zou G, Kim B, Zhang J, Jun S, Martin C, Dunbar KJ, Efe G, Rustgi AK, Nakagawa H, Park JI. Key Genetic Determinants Driving Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Initiation and Immune Evasion. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:613-628.e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lander S, Lander E, Gibson MK. Esophageal Cancer: Overview, Risk Factors, and Reasons for the Rise. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25:275-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wen D, Zhang L, Wang X, Li Y, Ma C, Liu X, Zhang J, Wen X, Yang Y, Zhang F, Wang S, Shan B. A 5.5-year surveillance of esophageal and gastric cardia precursors after a population-based screening in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1720-1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang H, Wang F, Hallemeier CL, Lerut T, Fu J. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2024;404:1991-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Joseph A, Draganov PV, Maluf-Filho F, Aihara H, Fukami N, Sharma NR, Chak A, Yang D, Jawaid S, Dumot J, Alaber O, Chua T, Singh R, Mejia-Perez LK, Lyu R, Zhang X, Kamath S, Jang S, Murthy S, Vargo J, Bhatt A. Outcomes for endoscopic submucosal dissection of pathologically staged T1b esophageal cancer: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96:445-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Beaufort IN, Frederiks CN, Overwater A, Brosens LAA, Koch AD, Pouw RE, Bergman JJGHM, Weusten BLAM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: long-term results from a Western cohort. Endoscopy. 2024;56:325-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Iwai N, Dohi O, Yamada S, Harusato A, Horie R, Yasuda T, Yamada N, Horii Y, Majima A, Zen K, Kimura H, Yagi N, Naito Y, Itoh Y. Prognostic risk factors associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection: a multi-center cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:2279-2289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ishido K, Tanabe S, Katada C, Kubota Y, Furue Y, Wada T, Watanabe A, Koizumi W. Usefulness of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in elderly patients: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51:895-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tajiri A, Tsujii Y, Nishida T, Inoue T, Maekawa A, Kitamura S, Yamaguchi S, Nishihara A, Yamada T, Ogiyama H, Murayama Y, Yamamoto S, Egawa S, Uema R, Yoshihara T, Hayashi Y, Takehara T. High incidence of lung cancer death after curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu BD, Udemba SC, Saleh S, Hill H, Song G, Fass R. Raloxifene increases the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal stricture in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35:e14689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Miwata T, Oka S, Tanaka S, Kagemoto K, Sanomura Y, Urabe Y, Hiyama T, Chayama K. Risk factors for esophageal stenosis after entire circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4049-4056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Mizuno J, Urabe Y, Oka S, Konishi H, Ishibashi K, Fukuhara M, Tanaka H, Tsuboi A, Yamashita K, Hiyama Y, Kotachi T, Takigawa H, Yuge R, Hiyama T, Tanaka S. Predictive factors for esophageal stenosis in patients receiving prophylactic steroid therapy after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hsu WH, Shih HY, Shen CS, Yu FJ, Wang HC, Chan LP, Kuo CH, Hsieh HM, Wu IC. Prevention and management of esophageal stricture after esophageal ESD: 10 years of experience in a single medical center. J Formos Med Assoc. 2023;122:486-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shibagaki K, Yuki T, Taniguchi H, Aimi M, Miyaoka Y, Yuki M, Ishimura N, Oshima N, Mishiro T, Tamagawa Y, Mikami H, Izumi D, Yamashita N, Sato S, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Prospective multicenter study of the esophageal triamcinolone acetonide-filling method in patients with subcircumferential esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:355-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou S, Chen X, Feng M, Shi C, ZhuoMa G, Ying L, Zhang Z, Cui L, Li R, Zhang J. Efficacy of different steroid therapies in preventing esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection: a comparative meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;100:1020-1033.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hikichi T, Nakamura J, Takasumi M, Hashimoto M, Kato T, Kobashi R, Takagi T, Suzuki R, Sugimoto M, Sato Y, Irie H, Okubo Y, Kobayakawa M, Ohira H. Prevention of Stricture after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Superficial Esophageal Cancer: A Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2020;10:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang J, Zhao Y, Li P, Zhang S. Advances in The Application of Regenerative Medicine in Prevention of Post-endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Esophageal Stenosis. J Transl Int Med. 2022;10:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Berger A, Rahmi G, Perrod G, Pioche M, Canard JM, Cesbron-Métivier E, Boursier J, Samaha E, Vienne A, Lépilliez V, Cellier C. Long-term follow-up after endoscopic resection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a multicenter Western study. Endoscopy. 2019;51:298-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lou F, Sima CS, Adusumilli PS, Bains MS, Sarkaria IS, Rusch VW, Rizk NP. Esophageal cancer recurrence patterns and implications for surveillance. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:1558-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10570] [Cited by in RCA: 11064] [Article Influence: 851.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51728] [Cited by in RCA: 48784] [Article Influence: 3252.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 30. | Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Ferguson MK, Blackstone EH, Goldstraw P. Cancer of the Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction: An Eighth Edition Staging Primer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 546] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Farjah F, Gerdes H, Gibson M, Grierson P, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jalal S, Keswani RN, Kim S, Kleinberg LR, Klempner S, Lacy J, Licciardi F, Ly QP, Matkowskyj KA, McNamara M, Miller A, Mukherjee S, Mulcahy MF, Outlaw D, Perry KA, Pimiento J, Poultsides GA, Reznik S, Roses RE, Strong VE, Su S, Wang HL, Wiesner G, Willett CG, Yakoub D, Yoon H, McMillian NR, Pluchino LA. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers, Version 2.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:393-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/