Published online Sep 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i34.109900

Revised: June 30, 2025

Accepted: August 13, 2025

Published online: September 14, 2025

Processing time: 103 Days and 20.3 Hours

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage, including endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy and endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepatogastrostomy (EUS-HGS), is an efficacious alternative to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and its common complications are bile leak, infection, stent migration and bleeding. Here, we report an atypical case of a patient who deve

A 76-year-old woman diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma received EUS-HGS for relieving jaundice. The patient reported abdominal pain and chest tightness after the operation, with difficulty in urinating. X-ray suggested right-sided pleural effusion and dark green pleural effusion was drained out. However, the patient also developed dark green urine, which appeared everyday afternoon and disappeared automatically after intravenous treatment. The previous pleural effusion disappeared after one week, but later the patient showed an increase of ascites, and the lesions were compartmentalized and encapsulated internally.

Postoperative surveillance after EUS-HGS must be emphasized to check for in order to prevent severe and hidden complications.

Core Tip: This case report focused on unexplained urinary changes following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepatogastrostomy. The patient developed unexplained dark green urine, which periodically appeared every morning and disappeared every afternoon after intravenous treatment. This phenomenon is highly intriguing and unexplainable, and calls for more attention to the complications of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD). Despite a high clinical success rate, EUS-BD may still be associated with adverse effects in one-seventh of the cases. Therefore, postoperative surveillance after EUS-BD must be emphasized.

- Citation: Zhang KY, He Q, Jin Y, Liu J, Lin R, Han CQ. Dark green urine following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(34): 109900

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i34/109900.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i34.109900

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) remains the first-line method for biliary access[1]. Neverthe

Common complications of EUS-BD include bile leak, infection (including cholangitis, pancreatitis, and biliary peri

A 76-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital, presented with a 2-month history of intermittent upper abdominal pain and a 1-week duration of scleral icterus. She received EUS-HGS for relieving jaundice at our hospital, and she reported acute abdominal pain, with chest tightness and dysuria on the second postoperative day.

The patient reported acute abdominal pain, chest tightness, and dysuria. Closed thoracic drainage yielded dark green fluid and the effusion resolved gradually in the following days. However, the urine drained out by catheterization was also bile-like dark green, which is unexplainable.

Previous imaging and histopathology confirmed that the patient had pancreatic head adenocarcinoma (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage III) with associated common bile duct dilation. She also had a history of hypertension for more than three years and took medication regularly.

No significant family history was reported.

The patient’s vital signs were within normal ranges. No obvious abnormality was observed on pulmonary or cardiac examination. She was observed to have scleral icterus. Her abdomen was non-distended and soft. Moderate tenderness was found on deep palpation of the upper abdomen without rebound tenderness.

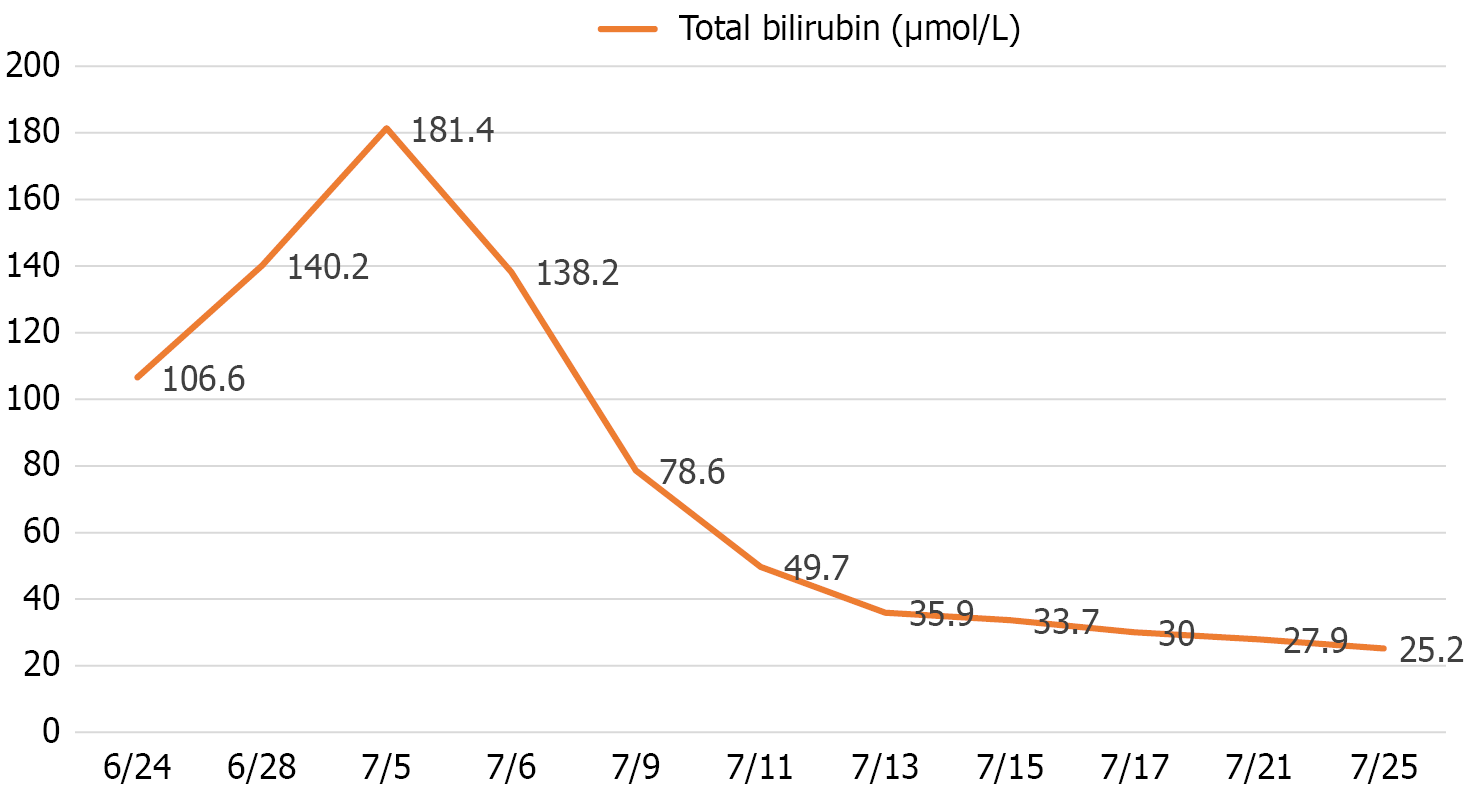

Prior to the EUS-HGS operation, the laboratory tests of the patient revealed significant hepatobiliary dysfunction: Total bilirubin (TBIL): 181.4 μmol/L (reference: 3.4-17.1 μmol/L); aspartate aminotransferase: 150 IU/L (reference: 8-40 IU/L), and alanine aminotransferase: 116 IU/L (reference: 5-40 IU/L). Serial bilirubin monitoring after the EUS-HGS demonstrated effective drainage: Preoperative: 181.4 μmol/L; post-operative day: 138.2 μmol/L; day 4: 78.6 μmol/L, and stabilized around 30 μmol/L in the following weeks (Figure 1).

The biochemistry of the pleural effusion: Total bilirubin: 326.6 μmol/L; direct bilirubin level: 158.1 μmol/L, and the total bile acid level: 1034.16 μmol/L. Urinalysis of the unknown dark green urine: Strong positive result of urinary bilirubin (++); and urinary occult blood (+++).

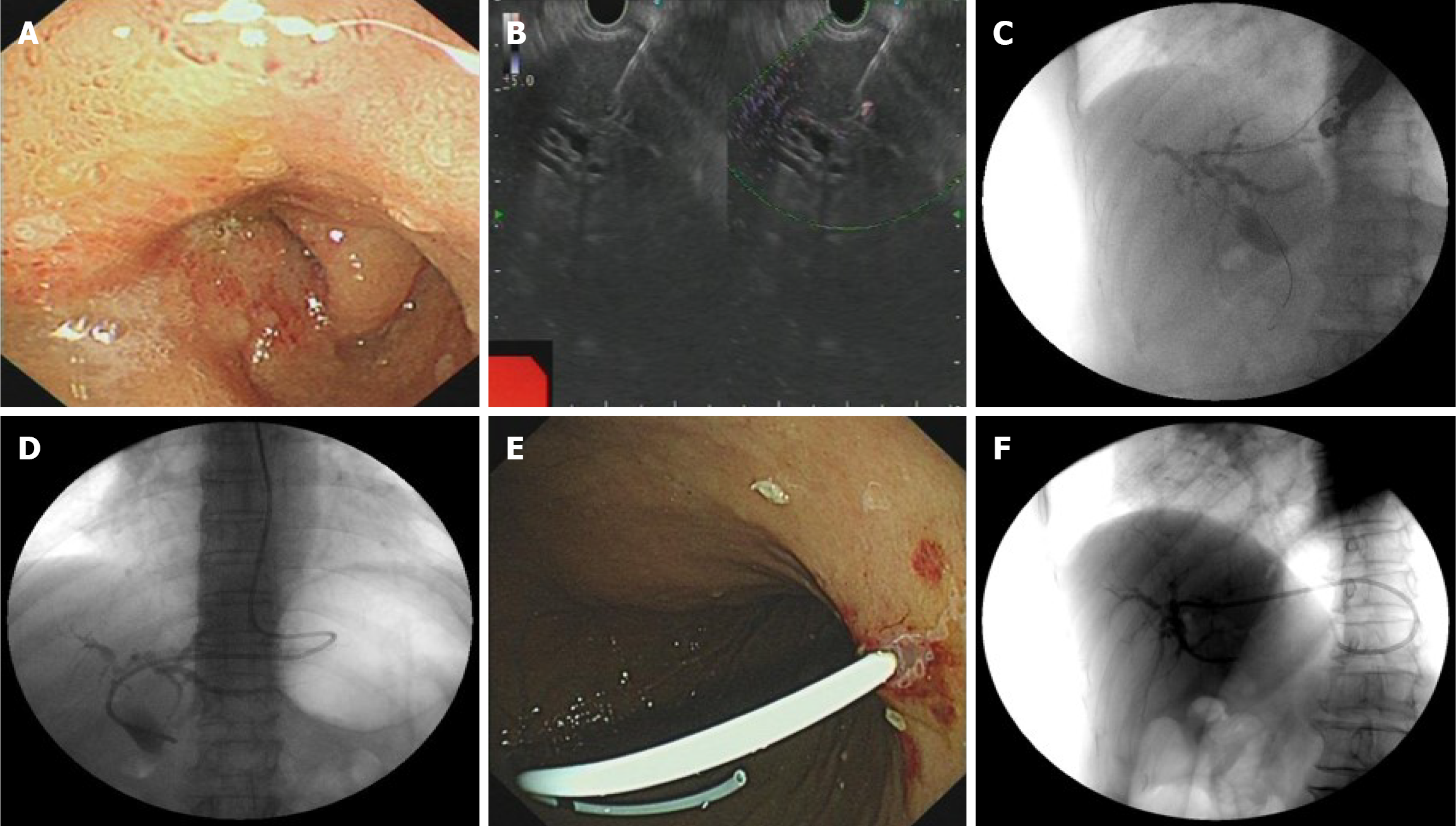

A skillful endoscopist with abundant EUS-BD experience (> 50 EUS-BD cases annually) conducted the operation using a linear array endoscopic ultrasound (Olympus processor EU-ME2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) via the gastric cardia’s posterior wall. The puncture succeeded, and the contrast agent (30% biligrafin) was injected to show the intrahepatic bile ducts. The whole operation was successful and concluded without immediate complications (Figure 2).

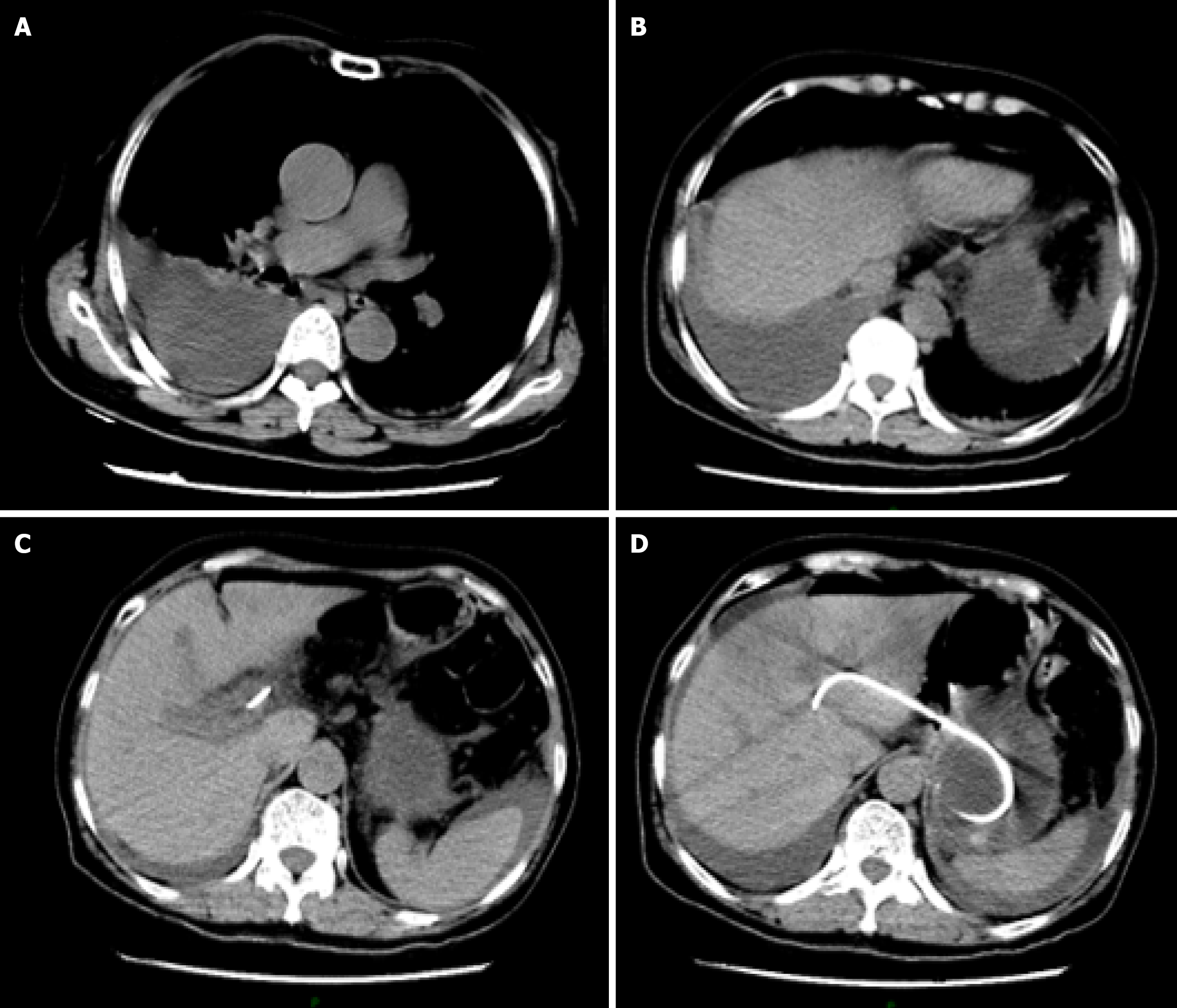

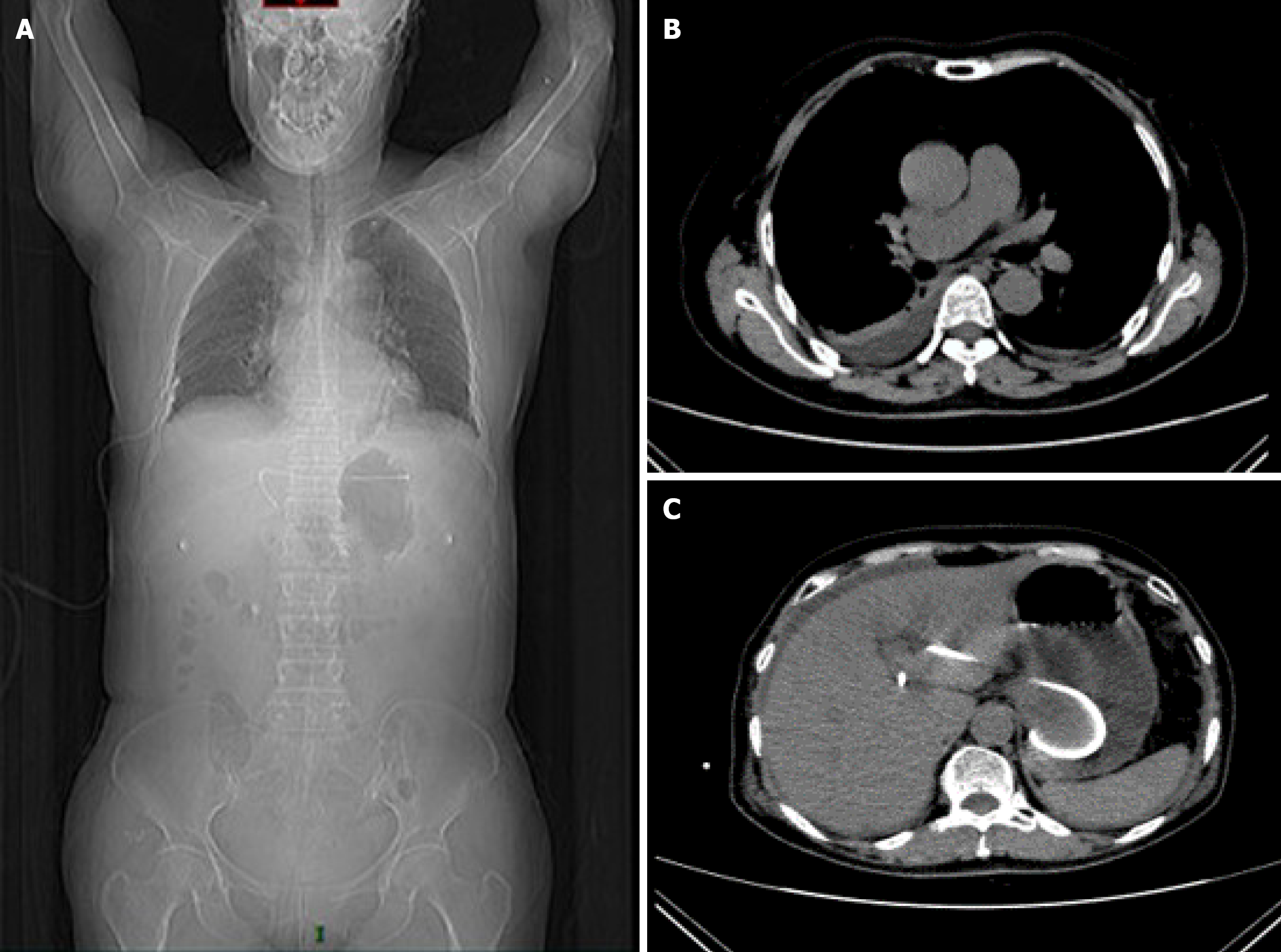

In the afternoon of the second postoperative day, the patient developed acute abdominal pain, with chest tightness and dysuria. Emergency thoracic computed tomography (CT) revealed right pleural effusion and right lower lobe atelectasis (Figure 3). Notably, the biliary stent remained well-positioned under CT, excluding the possibility of stent migration.

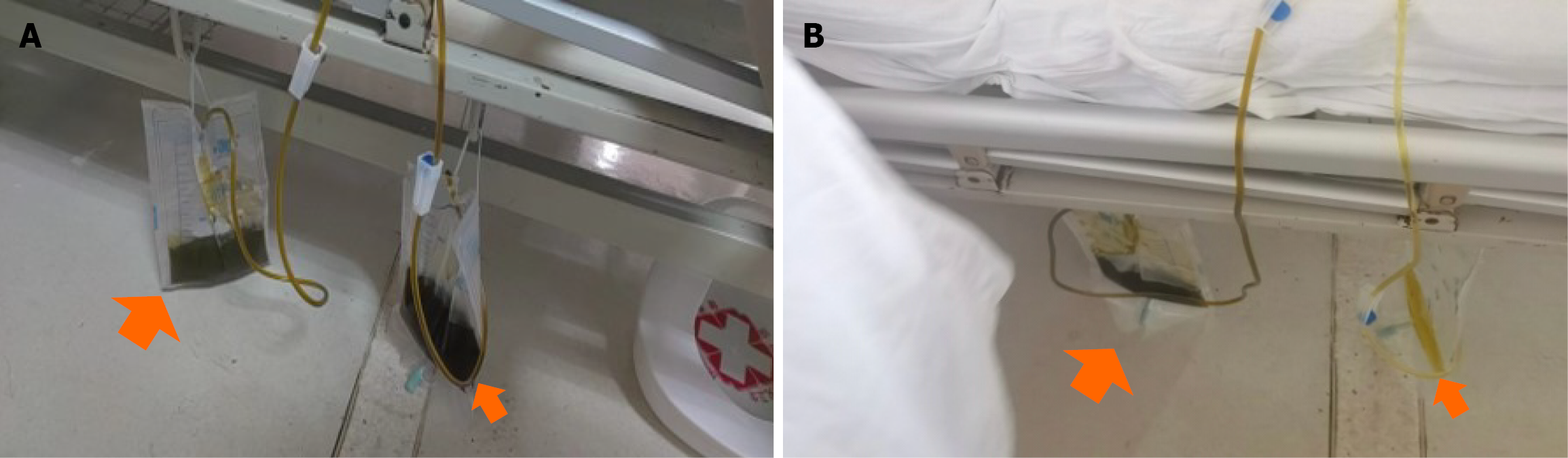

Closed thoracic drainage yielded dark green fluid (Figure 4A, left and bigger orange arrow). Given the temporal association and the imaging findings, we hypothesized iatrogenic microperforation of the diaphragm during transgastric puncture, permitting biliopleural leak. The effusion resolved gradually in the following days following closed thoracic drainage. However, the urine drained out by catheterization was also dark green (Figure 4A, right and smaller orange arrow), and just the same color (dark green) as the pleural effusion drained out. This abnormal change in urine color was unexplainable, but the color turned normal spontaneously after intravenous treatment every afternoon (Figure 4B).

Based on the above presentation, we suspected that this patient had developed complications of EUS-BD: Biliary leak, possibly caused by damage to the intrahepatic blood vessels, with bile flowing back through the bloodstream and entering the thoracic cavity via the blood circulation.

The patient was given an intravenous infusion of omeprazole for acid suppression, cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium for infection prevention and other therapies were adopted to maintain electrolyte balance.

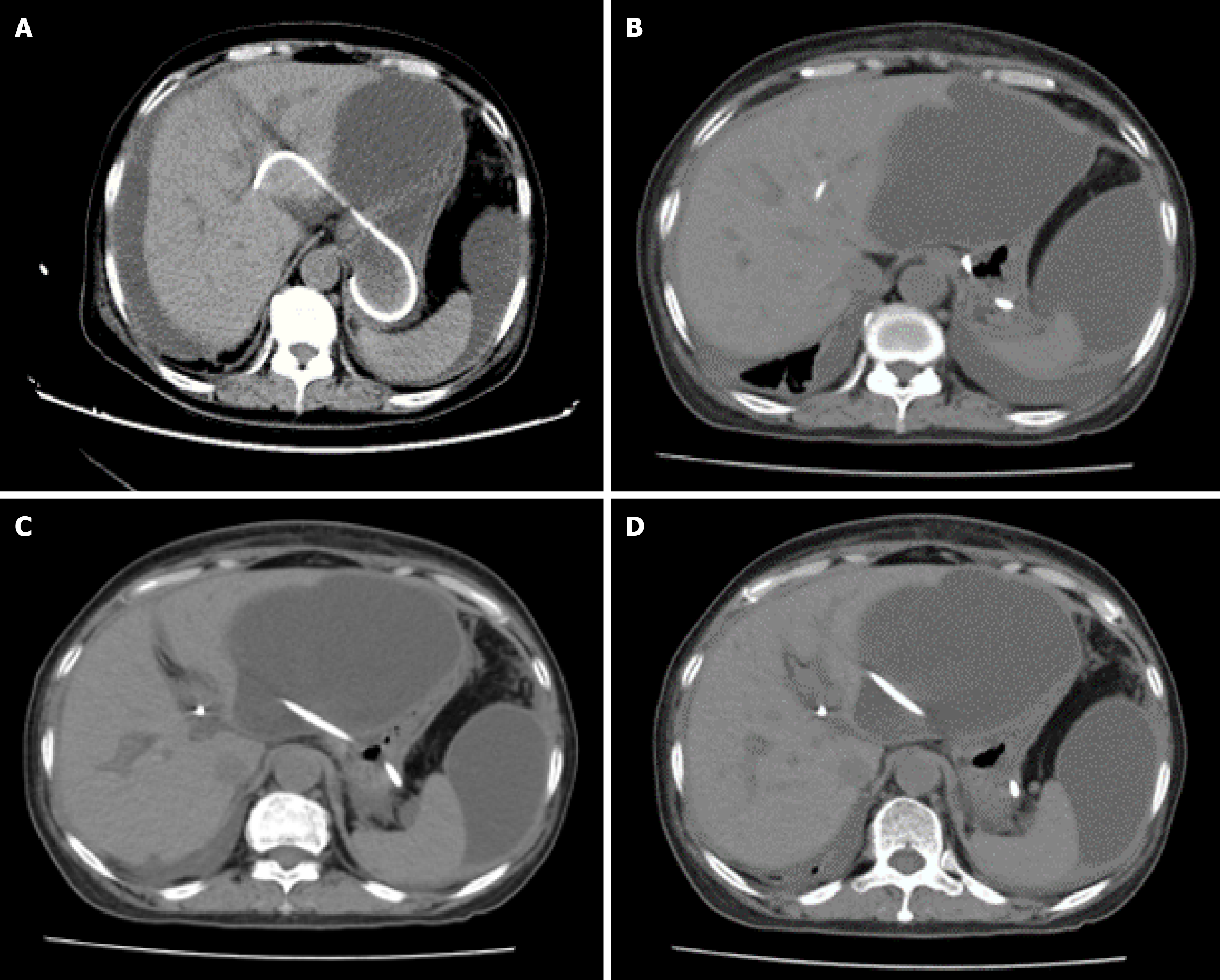

Follow-up CT at postoperative day 7 demonstrated (Figure 5) a significant increase in bile masses in the abdominal cavity, and the previous thoracic pleural effusion had mostly disappeared. Another follow-up CT scan on postoperative day 10, progressive encapsulation formed loculated ascites predominantly in the perihepatic space and pelvis (Figure 6).

The patient later developed aseptic biliary peritonitis, as her difficulty in urinating and pleural effusion on the right side suggested, possibly due to the lack of surgical treatment of the formed fistula. Blood test of the patient indicated elevated white blood cell count: 23.4 × 109 (reference: 4.0-10.0 × 109/L); C-reactive protein: 237 mg/L (reference: < 8 mg/L); and procalcitonin level: 0.64 ng/L (reference: < 0.5 ng/mL), indicating infection, further consolidating our diagnosis of aseptic biliary peritonitis. Ultrasound-guided abdominal duct drainage was attempted but failed due to high puncture difficulty and poor expected outcome. The patient, unfortunately, had ultimately died.

When ERCP fails due to inaccessible papilla or cannulation failure, EUS-BD supersedes percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage as the preferred salvage modality due to superior safety (15%-24%), comparable technical success (90%-95%)[10,11] and the advantage for being less invasive, having lower demand for re-intervention, being more cost-effective and causing less physical discomfort[11-13].

Although EUS-BD demonstrates superior safety over percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, procedure-specific complications require vigilant prevention. The most common complications of EUS-BD are bile leak, infection (including cholangitis, pancreatitis, and biliary peritonitis), and bleeding[2]. In addition, in some rare cases, stent migration may occur, which can be life-threatening.

Interestingly, the complication rates also vary according to the different biliary access routes. Two main approach routes in EUS-BD are EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS[14]. EUS-CDS was reported to be associated with a lower stent dysfunc

Based on the previous case presentation and laboratory findings, we suspected that this patient had developed complications of EUS-BD: Biliary leak. We speculate that there may be two reasons to explain the bile leak: (1) Puncture of the intrahepatic bile duct, with bile seeping into the thoracic cavity through the pleuroperitoneal space; and (2) Damage to the intrahepatic blood vessels, with bile flowing back through the bloodstream and entering the thoracic cavity via the blood circulation. The second reason seems more likely, as the urine also developed a bile-like dark green color (Figure 4). However, this complication is still insufficient to explain the color change of the urine, which appeared every afternoon. We suspected that this abnormal urine color may be associated with intraoperative injury to blood vessels, leading to the formation of a biliary-vascular fistula. The leaked bile juice entered the blood circulation directly and never underwent the normal metabolism of bile acids (Normally, bile is synthesized and secreted by the liver, enters the bloodstream, and a portion of bile is excreted through urine.). In this patient, it is suspected that the liver puncture may have damaged the intrahepatic bile ducts and small intrahepatic blood vessels, causing the bile to be directly released into the bloodstream and not be metabolized by the kidneys, thus causing bile juice-containing urine to be excreted by the kidneys, which may explain the dark green color of the urine (supported by strong positive results of urinary bilirubin and positive urine occult blood). However, this abnormal change resolved spontaneously after intravenous treatment every afternoon, which is also unexplained and needs further investigation. We speculated that during the day, intravenous infusion dilutes the bile in the blood, so the urine color is lighter during the day, while at night, no infusion is administered, making the color look darker in the morning.

We have further investigated whether this phenomenon could be attributed to a biochemical reaction between stagnant bile and specific contrast agent (such as iodinated contrast), especially in a setting of diabetes mellitus, which may promote the oxidation of the agent. This process is exacerbated by impaired gallbladder motility and bile acid metabolism in diabetes, prolonging pigment retention[18]. However, our patient had no previous history and a normal blood glucose level before and after the operation. Besides, the agent we used was biligrafin, which had no previous reports of causing abnormal urine color. Technical factors such as the equipment and the experience were also considered, but the equipment we used was at an advanced international level, and the whole process was operated by a skillful endoscopist with abundant EUS-BD operation experience (≥ 50 EUS-BD cases annually). Therefore, we consider that equipment-related problems may not be a major cause of the aberrant urine changes.

We have compared this phenomenon with purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS), another type of unusual urine color change first reported by Barlow and Dickson in 1978, and excluded its possibility based on clinical and laboratory distinctions. PUBS typically occurs in patients with long-term indwelling urinary catheters (usually over 2 weeks) and alkaline urine (pH ≥ 7.0), where indole metabolites produced by gut microbiota such as Escherichia coli react with plastic catheter materials to form purple pigments[19]. In contrast, our patient had no previous history of urinary catheterization, and the urine pH was acid (pH = 6.0). Additionally, PUBS urine cultures often demonstrate polymicrobial growth, such as Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis, whereas our patient’s urine culture was sterile. These findings robustly exclude PUBS as a potential diagnosis.

To further solidify the biliary-vascular fistula hypothesis, we also compared our case with other types of differential diagnosis of pigmented urine: (1) Hemoglobinuria: These conditions cause reddish-brown urine due to intravascular hemolysis or muscle injury. However, urine dipstick testing in our patient showed negative for blood (despite dark green coloration), excluding free hemoglobin or myoglobin. The absence of anemia and no significant decrease in serum haptoglobin further excluded this possibility; and (2) Porphyria: Porphyria is a complex metabolic disease which can present different urine color changes (such as reddish or dark) according to respective types[20]. However, our patient lacked dermatological syndromes or laboratory findings to support this diagnosis.

This study also had some limitations, it is a single case, therefore the generalizability of this study may be limited. But we still hope this case report may provide some insights on the recognition and prevention of potential EUS-BD complications. It’s noteworthy that EUS-BD has become the prior substitute for those who failed ERCP, and enhancing understanding of its process and potential risk, and preventing its complications (which can be fatal, such as stent migration) are of great importance to endoscopists. Despite a high clinical success rate, EUS-BD may still be associated with adverse effects in one-seventh of the cases. Therefore, postoperative surveillance after EUS-BD must be emphasized[8,9,21]. For patients with abnormal laboratory findings or clinical manifestations, CT scans must be done to check for possible abnormalities such as stent migration, pneumoperitoneum, or fluid collection.

This case report focused on unexplained urinary changes following EUS-HGS. The patient developed unexplained dark green urine which periodically appeared every morning and disappeared every afternoon after intravenous treatment. This phenomenon is highly intriguing and unexplainable, and calls for more attention on the complications of EUS-BD. Despite a high clinical success rate, EUS-BD may still be associated with adverse effects in one-seventh of the cases. Therefore, postoperative surveillance after EUS-BD must be emphasized. Besides, this procedure is appropriate only when operated by endoscopists with abundant experience.

| 1. | Baars JE, Kaffes AJ, Saxena P. EUS-guided biliary drainage: A comprehensive review of the literature. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:4-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mishra A, Tyberg A. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage: a comprehensive review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Doyle JB, Sethi A. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage. J Clin Med. 2023;12:2736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moole H, Bechtold ML, Forcione D, Puli SR. A meta-analysis and systematic review: Success of endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary stenting in patients with inoperable malignant biliary strictures and a failed ERCP. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e5154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Giri S, Mohan BP, Jearth V, Kale A, Angadi S, Afzalpurkar S, Harindranath S, Sundaram S. Adverse events with EUS-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:515-523.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dhindsa BS, Mashiana HS, Dhaliwal A, Mohan BP, Jayaraj M, Sayles H, Singh S, Ohning G, Bhat I, Adler DG. EUS-guided biliary drainage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang K, Zhu J, Xing L, Wang Y, Jin Z, Li Z. Assessment of efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1218-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Martins FP, Rossini LG, Ferrari AP. Migration of a covered metallic stent following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy: fatal complication. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E126-E127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hindryckx P, Degroote H, Tate DJ, Deprez PH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of the biliary system: Techniques, indications and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;11:103-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Duan F, Cui L, Bai Y, Li X, Yan J, Liu X. Comparison of efficacy and complications of endoscopic and percutaneous biliary drainage in malignant obstructive jaundice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Imaging. 2017;17:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharaiha RZ, Kumta NA, Desai AP, DeFilippis EM, Gabr M, Sarkisian AM, Salgado S, Millman J, Benvenuto A, Cohen M, Tyberg A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage: predictors of successful outcome in patients who fail endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5500-5505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ginestet C, Sanglier F, Hummel V, Rouchaud A, Legros R, Lepetit H, Dahan M, Carrier P, Loustaud-Ratti V, Sautereau D, Albouys J, Jacques J, Geyl S. EUS-guided biliary drainage with electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stent placement should replace PTBD after ERCP failure in patients with distal tumoral biliary obstruction: a large real-life study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:3365-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Paduano D, Facciorusso A, De Marco A, Ofosu A, Auriemma F, Calabrese F, Tarantino I, Franchellucci G, Lisotti A, Fusaroli P, Repici A, Mangiavillano B. Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Biliary Drainage in Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yamao K, Hara K, Mizuno N, Sawaki A, Hijioka S, Niwa Y, Tajika M, Kawai H, Kondo S, Shimizu Y, Bhatia V. EUS-Guided Biliary Drainage. Gut Liver. 2010;4 Suppl 1:S67-S75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Kato H, Itoi T, Kawakami H, Hanada K, Ishiwatari H, Yasuda I, Kawamoto H, Itokawa F, Kuwatani M, Iiboshi T, Hayashi T, Doi S, Nakai Y. Multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:328-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Khan MA, Akbar A, Baron TH, Khan S, Kocak M, Alastal Y, Hammad T, Lee WM, Sofi A, Artifon EL, Nawras A, Ismail MK. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:684-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rizqiansyah CY, Awatara PID, Amar N, Lesmana CRA, Mustika S. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) hepaticogastrostomy (HGS) versus choledochoduodenostomy (CDS) in ERCP-failed malignant biliary obstruction: A systematic review and META-analysis. JGH Open. 2024;8:e70037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Shafqet M, Sharzehi K. Diabetes and the Pancreatobiliary Diseases. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2017;15:508-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pallath AM, Gopan G, Tm A. Purple urine bag syndrome. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23:270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ramanujam VS, Anderson KE. Porphyria Diagnostics-Part 1: A Brief Overview of the Porphyrias. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2015;86:17.20.1-17.20.26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Matsubara S, Nakagawa K, Suda K, Otsuka T, Oka M, Nagoshi S. Practical Tips for Safe and Successful Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Hepaticogastrostomy: A State-of-the-Art Technical Review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/