Published online Jun 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i22.101915

Revised: April 25, 2025

Accepted: May 26, 2025

Published online: June 14, 2025

Processing time: 245 Days and 18 Hours

Mesalamine is the recommended first-line treatment for inducing and maintaining remission in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis (UC). However, adherence in real-world settings is frequently suboptimal. Encouraging collaborative patient-provider relationships may foster better adherence and patient outcomes.

To quantify the association between patient participation in treatment decision-making and adherence to oral mesalamine in UC.

We conducted a 12-month, prospective, non-interventional cohort study at 113 gastroenterology practices in Germany. Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years, had a confirmed UC diagnosis, had no prior mesalamine treatment, and provided informed consent. At the first visit, we collected data on demographics, clinical characteristics, patient preference for mesalamine formulation (tablets or granules), and disease knowledge. Self-reported adherence and disease activity were assessed at all visits. Correlation analyses and logistic regression were used to examine associations between adherence and various factors.

Of the 605 consecutively screened patients, 520 were included in the study. The median age was 41 years (range: 18-91), with a male-to-female ratio of 1.1:1.0. Approximately 75% of patients reported good adherence at each study visit. In correlation analyses, patient participation in treatment decision-making was significantly associated with better adherence across all visits (P = 0.04). In the regression analysis at 12 months, this association was evident among patients who both preferred and received prolonged-release mesalamine granules (odds ratio = 2.73, P = 0.001). Patients reporting good adherence also experienced significant improvements in disease activity over 12 months (P < 0.001).

Facilitating patient participation in treatment decisions and accommodating medication preferences may improve adherence to mesalamine. This may require additional effort but has the potential to improve long-term management of UC.

Core Tip: In this 12-month prospective study, we found that when patients were actively involved in choosing their mesalamine formulation, such as tablets versus granules, their adherence to therapy significantly improved. This was especially true when patients both preferred and received mesalamine granules. Importantly, patients who reported good adherence also experienced better outcomes, with significant improvements in disease activity over the course of the study. Our findings suggest that supporting shared decision-making in routine care and accommodating patient preferences, particularly regarding medication formulation, can make a difference in long-term management of ulcerative colitis.

- Citation: Kruis W, Jessen P, Morgenstern J, Reimers B, Müller-Grage N, Bokemeyer B. Shared decision-making improves adherence to mesalamine in ulcerative colitis: A prospective, multicenter, non-interventional cohort study in Germany. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(22): 101915

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i22/101915.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i22.101915

Mesalamine is the recommended first-line treatment for inducing and maintaining remission in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis (UC)[1]. However, adherence in real-world settings is frequently suboptimal. Survey-based studies have reported adherence rates between 50% and 70%[2-5], whereas an analysis of prescription and claims data reported a lower rate of 28%[6]. Observational data further suggest that adherence to mesalamine declines over time[7,8].

Poor adherence to mesalamine maintenance therapy has been consistently associated with an increased risk of disease flares[9-11], with one systematic review finding a more than threefold higher relative risk among non-adherent patients[12]. Non-adherence also contributes to greater healthcare utilization and costs, driven primarily by hospitalization[13] and, in some cases, escalation to newer medications such as infliximab[14].

Interventions aiming to improve adherence to mesalamine in UC have yielded mixed results[15]. A range of patient-related and health-system characteristics have been found to influence whether patients take mesalamine as prescribed including age[5,7], disease status[3,16], medication beliefs[4,16], and aspects of care delivery[17]. In this context, shared decision-making has been identified as a potentially important but underexplored determinant of treatment behavior across a range of medical conditions[18,19]. Active patient involvement in treatment decisions represents an integral component of shared decision-making[20,21], yet few studies have examined how it relates to treatment adherence in UC.

To help narrow this gap, we conducted a 12-month, prospective, multicenter, non-interventional cohort study among patients with UC who were initiating or re-initiating mesalamine treatment in routine practice at gastroenterology practices throughout Germany. The primary aim was to examine the association between patient participation in treatment decisions and adherence to oral mesalamine therapy. Secondary aims were to explore associations between patient and clinical characteristics, disease knowledge, and adherence, as well as to examine the relationship between adherence and disease activity over time.

This was a 12-month, prospective, multicenter, non-interventional cohort study conducted at 113 specialty gastroenterology practices in Germany with expertise in treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the North Rhine Chamber of Physicians (Approval No. 2011343) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01517607). All study participants provided signed informed consent before study enrollment. Patient data were pseudonymized and entered into an online electronic database using the double data entry method. Quality assurance measures were implemented online via electronic validity checks.

To be eligible for this study, patients had to be 18 years or older and have an endoscopically confirmed diagnosis of proctitis, left-sided colitis, or extensive colitis in accordance with clinical guidelines for UC published by the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. Additional eligibility criteria included a clinical need for oral mesalamine therapy, receipt of a first-time prescription for mesalamine in the form of PENTASA® slow-release tablets or prolonged-release granules (FERRING Arzneimittel, Kiel, Germany), and provision of written informed consent. Patients with a history of mesalamine treatment or contraindications to mesalamine therapy were excluded.

As this was a non-interventional study, decisions about diagnostic procedures and treatment were made by the treating physician according to patients’ clinical needs and in consideration of the full range of appropriate therapeutic options. This took place during a routine clinical visit (screening visit) before study inclusion and independently of the study. During this visit, all patients who were prescribed and agreed to receive oral mesalamine therapy in the form of PENTASA® were asked about their formulation preference (tablets or granules). If patients met the study eligibility criteria, they were consecutively informed about the study, including its objectives and procedures. Written informed consent was obtained during the screening visit or in the following days. Upon consent, patients started mesalamine treatment and were scheduled for their first official study visit (Visit 1). There were no restrictions on the use of concomitant medications during the study. The mesalamine dose was determined by the attending physician.

Data collection commenced at Visit 1 (month 0), followed by Visit 2 (months 4-8) and Visit 3 (month 12). At Visit 1, data were collected on patient demographics, disease characteristics (disease activity, extent and duration of UC), patient formulation preference (tablets or granules), details of mesalamine therapy (e.g., dosage), and any concomitant medications for UC. Additionally, information was gathered on patient knowledge of UC and self-reported adherence to mesalamine therapy since the screening visit. At subsequent visits, further data were collected on disease activity, therapy adjustments, formulation preference, concurrent treatments, and ongoing adherence.

Disease activity was assessed using the partial Mayo score (pMayo)[22], which consists of categories related to stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and the physician’s global assessment. Total scores range from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating more severe disease activity.

Patient knowledge of UC was assessed using a self-developed, patient-administered questionnaire that consisted of two parts. The first part asked patients to rate their own knowledge of UC (very good, good, moderate, poor, or don’t know). The second part involved answering nine yes or no questions about UC. For analysis purposes, the results were grouped based on the number of correct answers (poor: 0-2; moderate: 3-6; good or very good: 7-9).

Adherence to therapy was assessed using a self-developed, patient-administered questionnaire with a visual analogue scale (VAS) that ranged from 0 (I have taken all medication correctly) to 10 (I have taken no medication). A score of 2 or lower was categorized as “good adherence” and scores greater than 2 as “suboptimal adherence.”

Patient involvement in treatment decision-making was not measured directly; instead, it was inferred from whether or not the prescribing physician accommodated a patient’s preference with regard to the formulation of mesalamine (i.e. tablets or granules). Thus, instances in which patients received their preferred formulation of mesalamine were considered to be cases of shared decision-making in our analysis. Patients who indicated that they had no preference in terms of mesalamine formulation were not included in this variable.

Descriptive statistical methods and correlation analysis were applied, with results visualized through tables and box plots. The floating-point adherence values were found to be right-skewed and were thus analyzed using median and interquartile range (IQR), whereas the whole-numbered pMayo scores were normally distributed and analyzed using mean and standard deviation (SD). Independent sample t-tests were used to assess differences between two values, and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used for comparisons involving three values. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons for the Kruskal-Wallis H tests were conducted using Dunn’s Test with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Additionally, multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify independent predictors of good adherence to therapy. The model assessed the direct effects of the following pre-selected binary variables on adherence: Age (> 40 years vs ≤ 40 years); disease activity based on the pMayo score [low (≤ 3) vs moderate-to-high (> 3)]; self-reported patient knowledge of UC (“good or very good” vs “don’t know/poor/moderate”); and objectively measured patient knowledge of UC (score 7-9 = “good or very good” vs < 7). The model also considered whether patients received their preferred mesalamine formulation (yes vs no) irrespective of formulation type, as well as whether patients who preferred mesalamine granules received this formulation (yes vs no). Data for the regression were drawn from Visit 3; if data from Visit 3 were not available, data from Visit 2 were used instead. For the remaining variables, missing data were addressed using listwise deletion, ensuring that the regression was performed only on complete cases. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All data collected in the practices were stored pseudonymously in an electronic database. Documentation was performed using a secure data server hosted by an independent organization (IOMTech GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Statistical analyses were conducted using Python 3.10.6 and the libraries numpy, scipy, and matplotlib.

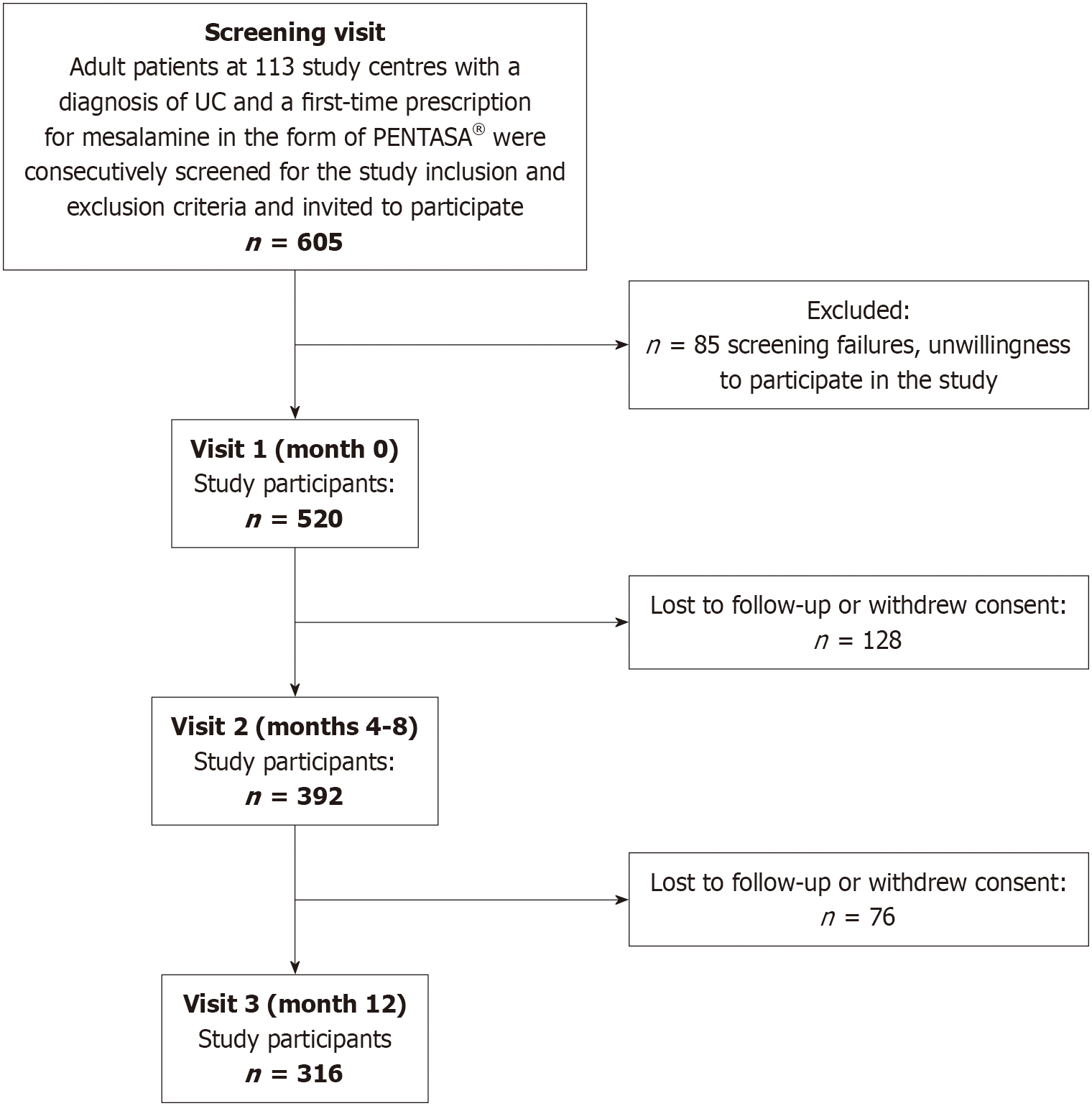

A total of 605 consecutive patients with UC had a first-time prescription for mesalamine. Of these patients, 85 did not meet the screening criteria or chose not to participate in the study, yielding a study cohort of 520 patients. The median age of the cohort was 41.0 years (range: 18-91 years), with a male-to-female ratio of 1.1:1.0. Whereas all 520 patients attended study Visit 1 (month 0), attendance decreased at subsequent visits, with 392 patients (75.3%) present at Visit 2 (months 4-8) and 316 patients (60.8%) present at Visit 3 (month 12). A participant flow diagram is provided in Figure 1.

Data on self-rated adherence to therapy were available for 446 patients at Visit 1, 349 patients at Visit 2, and 288 patients at Visit 3. The difference between these numbers and the total number of patients attending each visit was due to missing information or invalid entries, such as multiple markings on the VAS. The proportion of patients reporting good adherence (i.e. those with scores of 0-2) increased over the study period, with 72.4% (323 of 446) reporting good adherence at Visit 1, 78.2% (273 of 349) at Visit 2, and 79.5% (229 of 288) at Visit 3 (χ² = 6.04, P = 0.049). However, under the most conservative assumption that all patients who withdrew consent or were lost to follow-up exhibited suboptimal adherence to mesalamine therapy, the proportions would be as follows: 72.4% (323 of 446) at Visit 1, 61.2% (273 of 446) at Visit 2, and 51.3% (229 of 446) at Visit 3.

As shown in Table 1, most non-modifiable patient characteristics did not exhibit a significant relationship with adherence at Visit 1. The only exception was the localization of UC, with adherence being significantly lower in patients with left-sided colitis (P = 0.01).

| Variable | Definition | Percentage | Adherence median (IQR) |

| Sex | Female | 211 (47) | 0.5 (2.4) |

| Male | 235 (53) | 0.5 (2.2) | |

| Age | < 40 years | 193 (43) | 1.0 (2.4) |

| ≥ 40 years | 253 (57) | 0.3 (2.0) | |

| Disease duration | Newly diagnosed | 167 (38) | 0.4 (2.5) |

| < 2 years | 108 (24) | 0.7 (2.0) | |

| ≥ 2 years | 171 (38) | 0.5 (2.4) | |

| Localization1 | Extended | 140 (32) | 0.4 (1.6)a |

| Left-sided | 158 (36) | 0.9 (3.0) | |

| Proctitis | 144 (32) | 0.3 (1.7) |

Information about formulation preference was available for 506 of the 520 patients who took part in the study. Among these patients, 76.2% (386 of 506) expressed a preference for mesalamine granules, whereas 13.6% (69 of 506) favored tablets and 10.1% (51 of 506) had no preference. Physicians’ prescriptions aligned with patient preferences in 89.7% of cases for granules (n = 346) and in 88.4% of cases for tablets (n = 61).

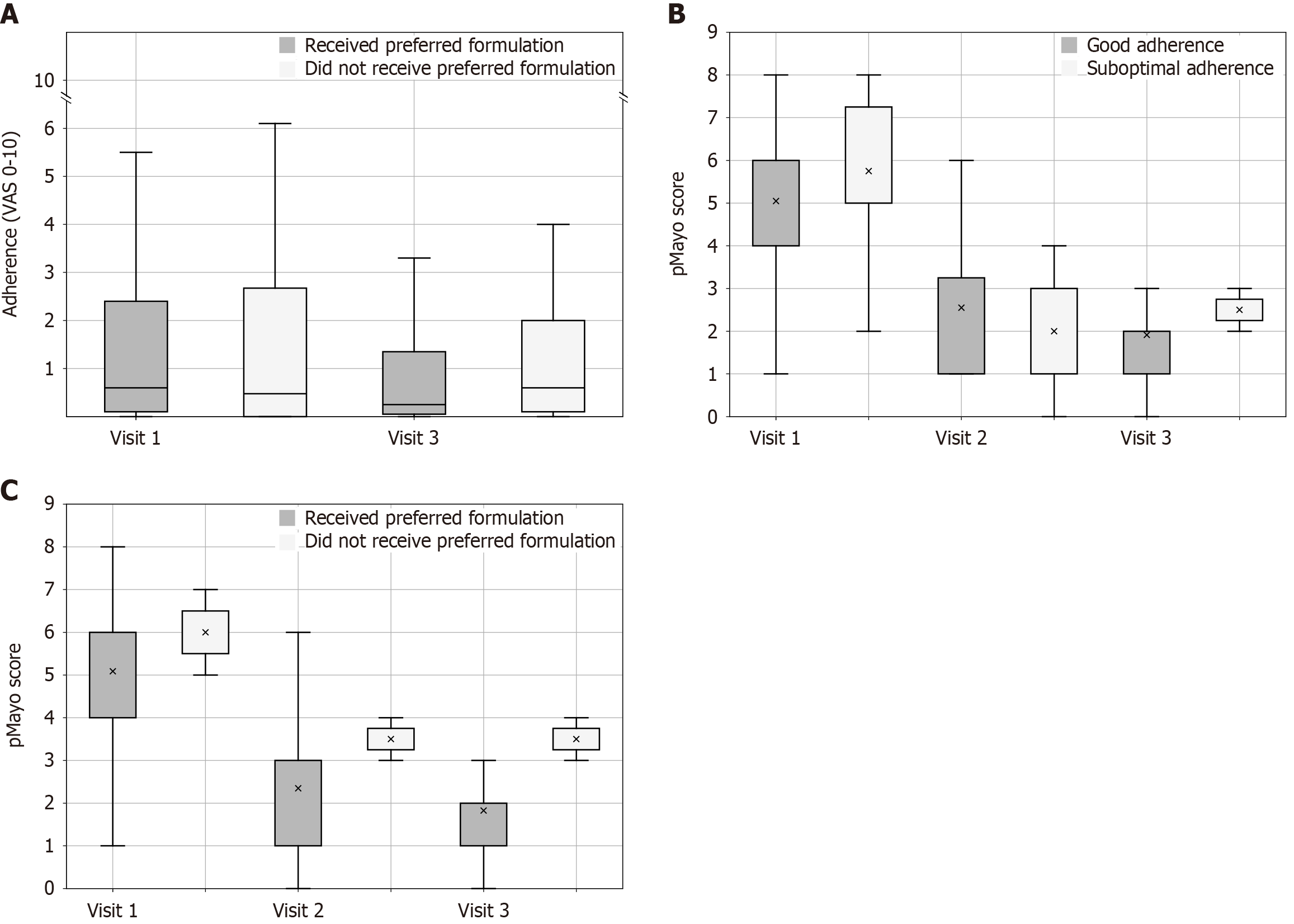

The results shown in Figure 2A suggest that accommodating patients’ formulation preference had a significant positive impact on adherence over time, regardless of mesalamine formulation. Among patients who received their formulation of choice (dark gray boxes), adherence improved over 12 months [Visit 1: Median 0.6 (IQR 2.6), Visit 3: Median 0.2 (IQR 2.4); P = 0.03] (Figure 2A). However, in patients whose choice of treatment was not respected (light gray boxes), adherence remained unchanged [Visit 1: Median 0.5 (IQR 2.7), Visit 3: Median 0.6 (IQR 2.2); P = 0.35].

When patients were asked to self-assess their general knowledge of UC, 39.3% rated this as good or very good, 40.6% as moderate, and 20% as poor or unknown. In our objective assessment involving specific UC-related questions, 31.7% of patients answered 7-9 questions correctly, 52.0% answered 3-6 questions correctly, and 16.3% answered 0-2 questions correctly. The individual UC-related questions in the objective assessment and the numbers and percentages of correct and incorrect answers for each are provided in Table 2. A comparison between patients’ self-assessed knowledge and objective knowledge suggests that patients tended to overestimate their knowledge of the disease, although the differences were small and reached significance only in the group with good or very good self-assessed knowledge.

| Questions | Answers1 | |

| Correct | Incorrect/don’t know | |

| Are patients with UC frequently affected by joint pain and skin conditions? | 206 (41.1) | 295 (58.9) |

| Do you know which part of your bowel is inflamed? | 430 (85.6) | 72 (14.4) |

| Is UC an infectious disease? | 501 (99.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Is UC a mental illness? | 474 (94.9) | 25 (5.0) |

| Is the immune system affected in UC? | 259 (51.7) | 242 (48.3) |

| Is it useful to treat UC with immunosuppressants? | 229 (45.9) | 269 (54.1) |

| Is there a special diet for UC? | 399 (79.8) | 101 (20.2) |

| Do patients with UC have a lower risk for colorectal cancer than the general population? | 480 (95.6) | 22 (4.4) |

| Is it possible to remove the entire colon without need for a permanent stoma? | 120 (24.1) | 377 (75.9) |

Additionally, the relationship between the median adherence score across all three study visits and patients’ objective knowledge of UC was assessed. The median adherence values were as follows: 0.3 (IQR 1.7) in patients with good or very good knowledge, 0.4 (IQR 1.7) in patients with moderate knowledge, and 0.5 (IQR 2.2) in patients with poor knowledge. The differences across groups, however, were not statistically significant.

The relationship between adherence and the course of the disease activity (pMayo) is illustrated in Figure 2B. A significant improvement in disease activity was observed from Visit 1 to Visit 3 only in the group reporting good adherence. This group experienced a consistent improvement over the 12-month period from Visit 1 to Visit 3 [Visit 1: Mean 5.05 (SD 1.97), Visit 2: Mean 2.55 (SD 1.56), Visit 3: Mean 1.83 (SD 1.14); P < 0.001]. Pairwise comparisons of the mean pMayo score at each visit showed a significant difference between Visit 1 and Visit 2 (P = 0.002) and Visit 1 and Visit 3 (P < 0.001) but not Visit 2 and Visit 3 (P = 0.80). By contrast, patients reporting suboptimal adherence experienced no significant change in disease activity during the observation period [Visit 1: Mean 5.75 (SD 2.28), Visit 2: Mean 2.0 (SD 1.29), Visit 3: Mean 2.50 (SD 0.50); P = 0.13].

Lastly, we analyzed the relationship between the accommodation of patient preference and the course of disease activity. Patients who received their preferred formulation regardless of formulation type experienced a continuous improvement in pMayo over 12 months [Visit 1: Mean 5.1 (SD 2.1), Visit 2: Mean 2.4 (SD 1.6), Visit 3: Mean 1.8 (SD 1.0); P < 0.001] (Figure 2C). Pairwise comparisons of the mean pMayo score at each visit showed a significant difference between Visit 1 and Visit 2 (P < 0.001) and Visit 1 and Visit 3 (P < 0.001) but not Visit 2 and Visit 3 (P = 1.0). By contrast, those who did not receive their preferred formulation saw an initial decrease in pMayo [Visit 1: Mean 6.0 (SD 1.0)], which then plateaued until the end of the observation period [Visit 3: Mean 3.5 (SD 0.5); P = 0.1]. In the latter group, the differences were not statistically significant.

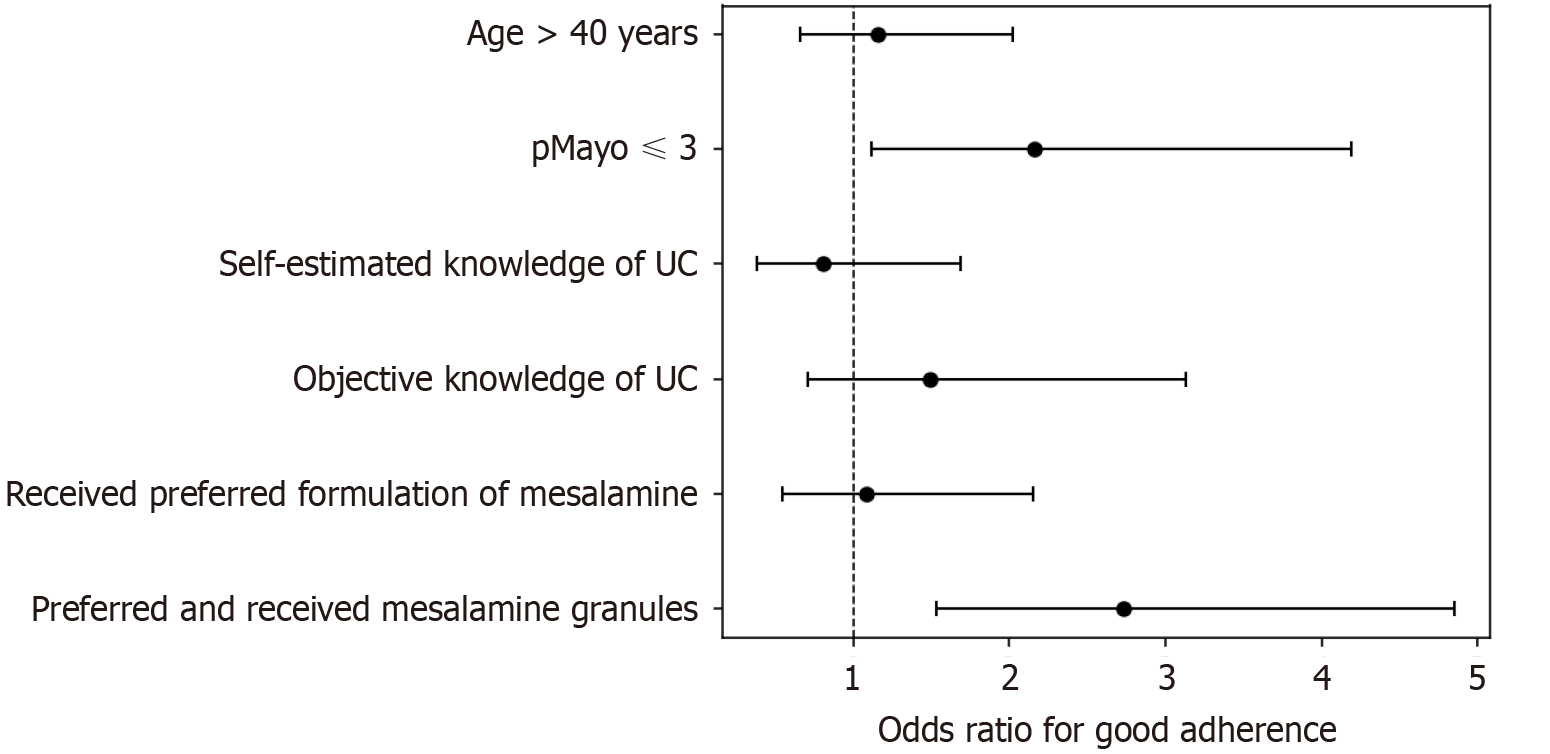

Multivariable logistic regression analysis assessed the associations between the various pre-selected predictors and adherence at Visit 3. The association between age greater than 40 years and adherence was not significant [odds ratio (OR): 1.15, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.66-2.02; P = 0.62]. By contrast, a significant association was found for patients with a pMayo score ≤ 3, who demonstrated greater adherence (OR: 2.16, 95%CI: 1.12-4.19; P = 0.02). Neither self-estimated good knowledge of UC nor objectively measured good knowledge (scores 7-9) showed a significant association with adherence (OR: 0.80, 95%CI: 0.38-1.69, P = 0.56; OR: 1.49, 95%CI: 0.71-3.13, P = 0.29, respectively). However, there was a strong association between receipt of the preferred medication formulation and greater adherence among those who preferred and received granules (OR: 2.73, 95%CI: 1.53-4.85; P = 0.001). This was not the case for the broader group of those who received their preferred medication formulation regardless of formulation type (OR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.54-2.15; P = 0.29). These results are depicted in Figure 3 as a forest plot displaying ORs and their corresponding 95%CIs.

This prospective, multicenter, non-interventional cohort study involving 113 specialty gastroenterology practices in Germany examined treatment adherence to a specific mesalamine product over a 12-month period. Approximately 75% of patients at each of the three study visits reported taking all or almost all their medication correctly. This contrasts with previous literature reporting lower adherence rates to mesalamine therapy[2-8]. However, the substantial attrition seen over the 12-month observation period must be considered. If one assumes that patients lost to follow-up had poor adherence, then overall adherence rates would drop from 72.4% at Visit 1 to only 51.3% at Visit 3, figures more consistent with previous literature. The true adherence level probably lies between these extremes.

Previous studies have reported that adherence is inversely related to the frequency of disease flares, with flare rates exceeding 10% after 2 years and 17% after 10 years in patients with low adherence (< 50%) compared to those with high adherence (≥ 80%)[8,9]. In our study, patients with good adherence experienced significant improvement in disease activity over 12 months. By contrast, suboptimally adherent patients experienced no significant change. It is possible that attrition in our cohort influenced our results. If we assume that patients lost to follow-up tended to have the weakest adherence - a reasonable assumption given the well-established relationship between poor adherence and an increase in disease flares - then the remaining group of suboptimally adherent patients in our study likely represents a “best case” scenario. The absence of improvement in disease activity even within this comparatively better subgroup suggests that the true association between poor adherence and unfavorable disease outcomes may be even stronger than observed here. This further emphasizes the need to develop effective strategies to support adherence in the long-term management of UC.

To contextualize these findings, it is useful to distinguish between non-modifiable and modifiable factors that influence adherence. In our cohort, disease localization was the only non-modifiable factor associated with adherence, supporting the findings of previous studies[6,23]. By contrast, the patient-physician interaction represents a modifiable factor that has been shown to play an important role in encouraging patients to adhere to their therapy. For example, a recent cluster randomized controlled trial demonstrated that in patients with Crohn’s disease, shared decision-making led to patients more frequently choosing the superior treatment strategy and experiencing lower decisional conflict and greater trust in their provider[24].

In our study, physicians individually discussed the different mesalamine formulations with each patient, allowing them to express their preferences. We interpreted the accommodation of these preferences as a proxy for shared decision-making. Patients whose preference was accommodated demonstrated improved adherence over time. In contrast, adherence remained unchanged in those whose preference was not accommodated. These findings are consistent with the broader literature suggesting that patient involvement in decision-making contributes to better adherence and potentially also better health outcomes[19,25,26].

Our regression analysis added further detail to this picture. Whereas receiving any preferred formulation was not significantly associated with adherence at 12 months, patients who both preferred and received mesalamine granules showed better adherence. This suggests that the specific formulation (i.e. granules) may have been perceived as easier to use, more tolerable, or more compatible with patients’ lifestyles. Previous studies support this interpretation, with mesalamine granules demonstrating higher patient acceptability and lower discontinuation rates than tablets[27,28]. Such formulation-specific benefits may be obscured when preferred formulations are grouped together, possibly explaining the lack of significance in broader categories.

With regard to patient education, we found no significant association between disease knowledge and self-reported treatment adherence. This is consistent with an earlier trial showing that a standardized patient education program did not improve adherence over the 14-month observation period[29]. Thus, while patient knowledge is often presumed to support adherence, our findings suggest that it may be insufficient on its own.

In summary, this study provides evidence that adherence to mesalamine treatment in UC is influenced by modifiable factors related to treatment delivery. Although demographic and disease-related aspects play a role, our results indicate that involving patients in treatment decisions, particularly regarding the choice of medication formulation such as granules, can support better adherence. In clinical practice, this emphasizes the importance of not only offering patients a choice between formulations but also of engaging them in an open discussion about their preferences and treatment goals. Looking ahead, interventions to improve adherence in UC should focus on systematically incorporating shared decision-making into routine care, supported by clinician training and practical tools to facilitate patient involvement in therapeutic planning.

An important strength of our study is its use of real-world data without formal interventions that require following stringent inclusion criteria, which would exclude many of the patients seen in everyday practice. This allowed us to examine the associations between adherence and a range of modifiable and unmodifiable factors under real-world clinical conditions. However, our study also had a number of important limitations that must be considered when interpreting its results. First, physicians’ accommodation of patient preference for mesalamine formulation served as a proxy for patient involvement in treatment decision-making. While this approach was pragmatic, it clearly represents an oversimplification of the multifaceted process of shared decision-making. In particular, it cannot account for variability in physician interpretation and response to patient preferences nor for variability in patients’ ability to communicate their preferences clearly. Second, substantial attrition was observed over the 12-month observation period, which is typical in a real-world, non-interventional cohort study. The advantage of real-world results is that they provide a more accurate picture of patient behavior outside the controlled conditions of a clinical trial. By assuming the worst-case scenario - that all patients who dropped out or were lost to follow-up exhibited suboptimal adherence - we could highlight the potential impact of attrition on the adherence rates reported. Third, patients who enroll in a study that entails assessments of medication use and who are aware of being monitored may demonstrate better adherence than the broader population of UC patients, or they may report inflated rates due to social desirability. Current clinical practice generally relies on self-report, which tends to overestimate adherence. Nevertheless, patient self-assessment of adherence has been shown to be a simple and realistic measurement in many studies[30-33], and is often the only option in settings where funding and other resources may be limited. Fifth, the predominantly European-Caucasian demographic composition of our sample may limit generalizability, as patients from underrepresented minorities have been shown to have lower adherence rates[34]. Lastly, the non-interventional, observational design of our study allows for the assessment of associations but does not permit causal inferences.

Patient adherence to mesalamine therapy in UC is influenced by a range of factors, from those that cannot be modified, such as demographic and disease characteristics, to those that can, such as accommodation of patient preferences for medication formulation (e.g., granules or tablets). Findings from our prospective, multicenter, non-interventional cohort study indicate that addressing these modifiable factors can improve adherence and, in turn, lead to better clinical outcomes. In particular, our results support the further integration of shared decision-making into routine gastroenterology care. This involves not only discussing treatment options with patients but also implementing practical measures to support their involvement, such as clinician training and tools for guiding therapeutic planning. Effective shared decision-making requires meaningful dialogue that considers the patient’s individual situation, including barriers to adherence and formulation preferences, and respects their perspective. Although ensuring active patient participation in treatment decisions may require additional time and resources, it has the potential to improve adherence and, ultimately, long-term disease management and outcomes in UC.

The MUKOSA (Mesalazin (PENTASA®) bei Colitis ulcerosa: Korrelation des Informationsstandes mit der Compliance im Alltag) study group.

| 1. | Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, Kucharzik T, Adamina M, Annese V, Bachmann O, Bettenworth D, Chaparro M, Czuber-Dochan W, Eder P, Ellul P, Fidalgo C, Fiorino G, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gordon H, Hedin C, Holubar S, Iacucci M, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Lakatos PL, Lytras T, Lyutakov I, Noor N, Pellino G, Piovani D, Savarino E, Selvaggi F, Verstockt B, Spinelli A, Panis Y, Doherty G. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 584] [Cited by in RCA: 673] [Article Influence: 168.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Shale MJ, Riley SA. Studies of compliance with delayed-release mesalazine therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:191-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | D'Incà R, Bertomoro P, Mazzocco K, Vettorato MG, Rumiati R, Sturniolo GC. Risk factors for non-adherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:166-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moshkovska T, Stone MA, Clatworthy J, Smith RM, Bankart J, Baker R, Wang J, Horne R, Mayberry JF. An investigation of medication adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, using self-report and urinary drug excretion measurements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1118-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tripathi K, Dong J, Mishkin BF, Feuerstein JD. Patient Preference and Adherence to Aminosalicylates for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2021;14:343-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lachaine J, Yen L, Beauchemin C, Hodgkins P. Medication adherence and persistence in the treatment of Canadian ulcerative colitis patients: analyses with the RAMQ database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jayasooriya N, Pollok RC, Blackwell J, Bottle A, Petersen I, Creese H, Saxena S; POP-IBD study group. Adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid maintenance treatment in young people with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2023;73:e850-e857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lenti MV, Selinger CP. Medication non-adherence in adult patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review and update of the determining factors, consequences and possible interventions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:215-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khan N, Abbas AM, Bazzano LA, Koleva YN, Krousel-Wood M. Long-term oral mesalazine adherence and the risk of disease flare in ulcerative colitis: nationwide 10-year retrospective cohort from the veterans affairs healthcare system. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:755-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawakami A, Tanaka M, Nishigaki M, Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Hibi T, Sanada H, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Kazuma K. Relationship between non-adherence to aminosalicylate medication and the risk of clinical relapse among Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission: a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1006-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Higgins PD, Rubin DT, Kaulback K, Schoenfield PS, Kane SV. Systematic review: impact of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid products on the frequency and cost of ulcerative colitis flares. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:247-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Mitra D, Hodgkins P, Yen L, Davis KL, Cohen RD. Association between oral 5-ASA adherence and health care utilization and costs among patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Selinger CP. How costly is non-adherence to infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease? J Med Econ. 2014;17:881-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bernick SJ, Kane S. Optimizing use of 5-ASA in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: Focus on patient compliance and adherence. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2010;1:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kawakami A, Tanaka M, Nishigaki M, Yoshimura N, Suzuki R, Maeda S, Kunisaki R, Yamamoto-Mitani N. A screening instrument to identify ulcerative colitis patients with the high possibility of current non-adherence to aminosalicylate medication based on the Health Belief Model: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yen L, Wu J, Hodgkins PL, Cohen RD, Nichol MB. Medication use patterns and predictors of nonpersistence and nonadherence with oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18:701-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 639] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Elias S, Chen Y, Liu X, Slone S, Turkson-Ocran RA, Ogungbe B, Thomas S, Byiringiro S, Koirala B, Asano R, Baptiste DL, Mollenkopf NL, Nmezi N, Commodore-Mensah Y, Himmelfarb CRD. Shared Decision-Making in Cardiovascular Risk Factor Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e243779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Waddell A, Lennox A, Spassova G, Bragge P. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in hospitals from policy to practice: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16:74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 983] [Cited by in RCA: 1435] [Article Influence: 159.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, Lichtenstein GR, Aberra FN, Ellenberg JH. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1660-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 733] [Cited by in RCA: 770] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kane SV, Brixner D, Rubin DT, Sewitch MJ. The challenge of compliance and persistence: focus on ulcerative colitis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14:s2-12; quiz s13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zisman-Ilani Y, Thompson KD, Siegel LS, Mackenzie T, Crate DJ, Korzenik JR, Melmed GY, Kozuch P, Sands BE, Rubin DT, Regueiro MD, Cross R, Wolf DC, Hanson JS, Schwartz RM, Vrabie R, Kreines MD, Scherer T, Dubinsky MC, Siegel CA. Crohn's disease shared decision making intervention leads to more patients choosing combination therapy: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57:205-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, Onate K, Denis JL, Pomey MP. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 450] [Cited by in RCA: 740] [Article Influence: 92.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Peters AE, Keeley EC. Patient Engagement Following Acute Myocardial Infarction and Its Influence on Outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1467-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Yagisawa K, Kobayashi T, Ozaki R, Okabayashi S, Toyonaga T, Miura M, Hayashida M, Saito E, Nakano M, Matsubara H, Hisamatsu T, Hibi T. Randomized, crossover questionnaire survey of acceptabilities of controlled-release mesalazine tablets and granules in ulcerative colitis patients. Intest Res. 2019;17:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nakagawa S, Okaniwa N, Mizuno M, Sugiyama T, Yamaguchi Y, Tamura Y, Izawa S, Hijikata Y, Ebi M, Ogasawara N, Funaki Y, Sasaki M, Kasugai K. Treatment Adherence in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Is Dependent on the Formulation of 5-Aminosalicylic Acid. Digestion. 2019;99:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nikolaus S, Schreiber S, Siegmund B, Bokemeyer B, Bästlein E, Bachmann O, Görlich D, Hofmann U, Schwab M, Kruis W. Patient Education in a 14-month Randomised Trial Fails to Improve Adherence in Ulcerative Colitis: Influence of Demographic and Clinical Parameters on Non-adherence. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1052-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sandborn WJ, Korzenik J, Lashner B, Leighton JA, Mahadevan U, Marion JF, Safdi M, Sninsky CA, Patel RM, Friedenberg KA, Dunnmon P, Ramsey D, Kane S. Once-daily dosing of delayed-release oral mesalamine (400-mg tablet) is as effective as twice-daily dosing for maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1286-1296, 1296.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bokemeyer B, Teml A, Roggel C, Hartmann P, Fischer C, Schaeffeler E, Schwab M. Adherence to thiopurine treatment in out-patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:217-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Stone JK, Shafer LA, Graff LA, Lix L, Witges K, Targownik LE, Haviva C, Sexton K, Bernstein CN. Utility of the MARS-5 in Assessing Medication Adherence in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Brenner EJ, Long MD, Kappelman MD, Zhang X, Sandler RS, Barnes EL. Development of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Specific Medication Adherence Instrument and Reasons for Non-adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sewell JL, Velayos FS. Systematic review: The role of race and socioeconomic factors on IBD healthcare delivery and effectiveness. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:627-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/