Published online Jun 14, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i22.2468

Peer-review started: August 3, 2021

First decision: October 2, 2021

Revised: October 31, 2021

Accepted: May 16, 2022

Article in press: May 16, 2022

Published online: June 14, 2022

Processing time: 310 Days and 10 Hours

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most lethal malignancies with high mortality and short survival time. Computed tomography (CT) plays an important role in the diagnosis, staging and treatment of pancreatic tumour. Pancreatic cancer generally shows a low enhancement pattern compared with normal pancreatic tissue.

To analyse whether preoperative enhanced CT could be used to predict postope

Sixty-seven patients with PDAC undergoing pancreatic resection were enrolled retrospectively. All patients underwent preoperative unenhanced and enhanced CT examination, the CT values of which were measured. The ratio of the preoperative CT value increase from the nonenhancement phase to the portal venous phase between pancreatic tumour and normal pancreatic tissue was calculated. The cut-off value of ratios was obtained by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the tumour relative enhancement ratio (TRER), according to which patients were divided into low- and high-enhancement groups. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox regression based on TRER grouping. Finally, the correlation between TRER and clinicopathological characteristics was analysed.

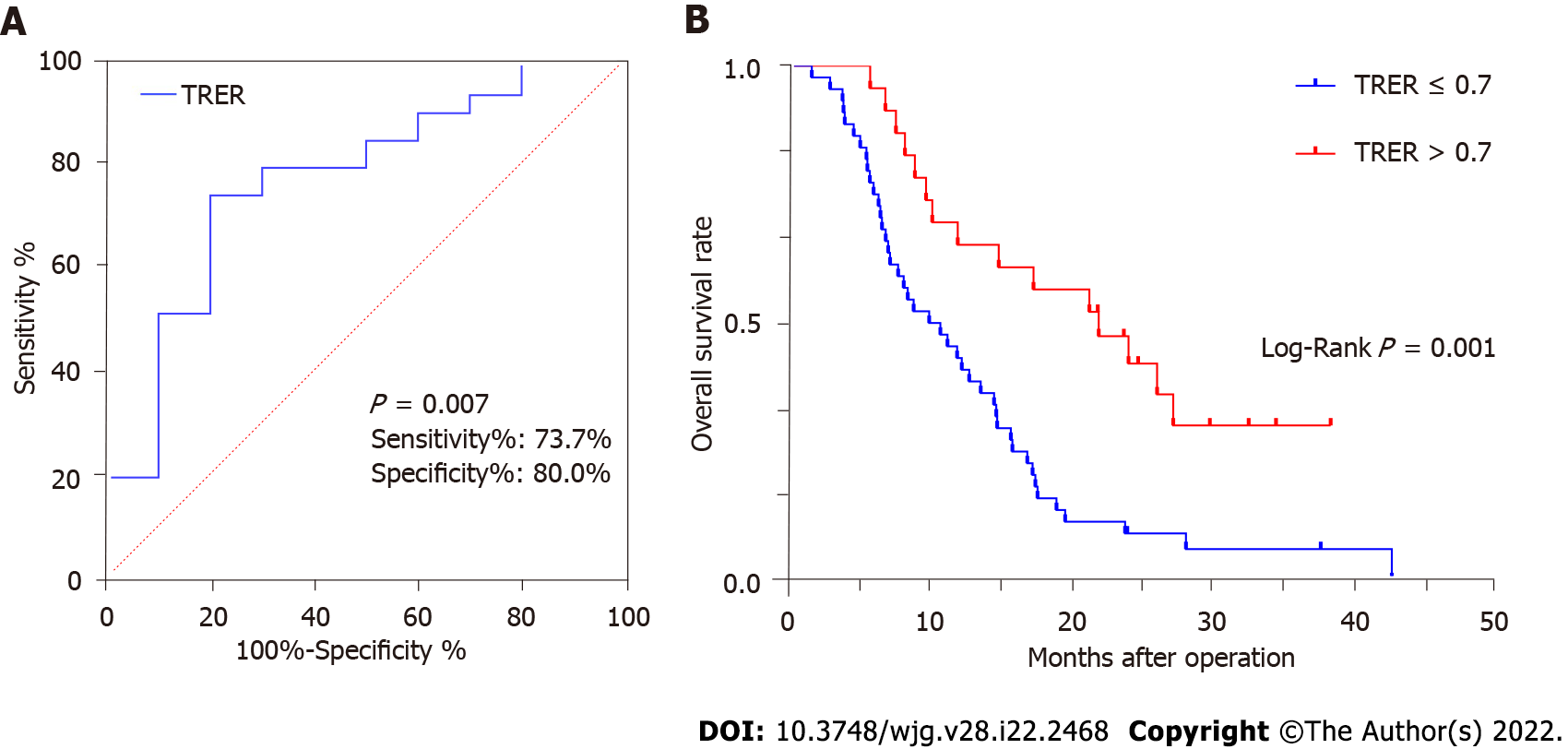

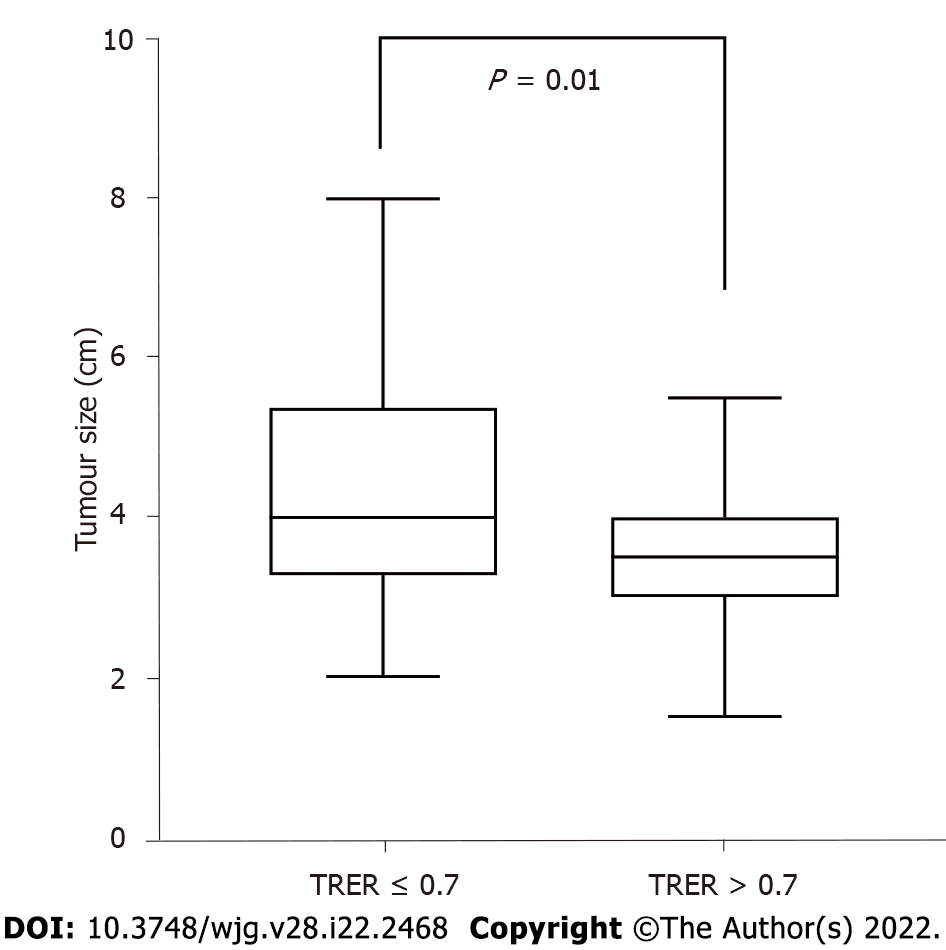

The area under the curve of the ROC curve was 0.768 (P < 0.05), and the cut-off value of the ROC curve was calculated as 0.7. TRER ≤ 0.7 was defined as the low-enhancement group, and TRER > 0.7 was defined as the high-enhancement group. According to the TRER grouping, the Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis results showed that the median survival (10.0 mo) with TRER ≤ 0.7 was significantly shorter than that (22.0 mo) with TRER > 0.7 (P < 0.05). In the univariate and multivariate analyses, the prognosis of patients with TRER ≤ 0.7 was significantly worse than that of patients with TRER > 0.7 (P < 0.05). Our results demonstrated that patients in the low TRER group were more likely to have higher American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, tumour stage and lymph node stage (all P < 0.05), and TRER was significantly negatively correlated with tumour size (P < 0.05).

TRER ≤ 0.7 in patients with PDAC may represent a tumour with higher clinical stage and result in a shorter overall survival.

Core Tip: Computed tomography (CT) plays an important role in the diagnosis, staging and treatment of pancreatic tumours. Pancreatic cancer generally shows a low enhancement pattern compared with normal pancreatic tissue. In our analysis, the prognosis of patients with the tumour relative enhancement ratio (TRER) less than or equal to 0.7 was significantly worse than that of patients with TRER greater than 0.7. TRER was significantly correlated with American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, tumour stage, and lymph node stage. Preoperative enhanced CT provides a simple and effective prediction of postoperative overall survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

- Citation: Gao JF, Pan Y, Lin XC, Lu FC, Qiu DS, Liu JJ, Huang HG. Prognostic value of preoperative enhanced computed tomography as a quantitative imaging biomarker in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(22): 2468-2481

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i22/2468.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i22.2468

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a highly malignant tumour with an estimated 56770 new cases and 45750 deaths in the United States in 2019, according to the American Cancer Society[1]. Very few patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma have the opportunity for surgical treatment due to the low early diagnosis rate[2]. Surgery is the only potential curative treatment for resectable pancreatic cancer, and adjuvant chemotherapy, mainly gemcitabine-based regimen, is often used to improve outcome[3,4]. In recent years, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy has shown efficacy in improving the prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer[5]. However, the overall prognosis is still unsatisfactory, with a 5-year survival rate as low as 8%[6]. Considering the extremely poor prognosis of pancreatic cancer, it is important to identify indicators of poor prognosis preoperatively or postoperatively. Currently, multiple diagnostic techniques are used to evaluate the aggressiveness or malignancy of pancreatic cancer to formulate the best treatment plan.

A previous study on endoscopic ultrasonography showed that the strain rate of the tumour was positively correlated with the stromal ratio of pancreatic cancer. The stroma of the tumour contributes to tumour growth and progression and plays an important role in chemotherapy resistance. Patients with a high strain rate had a poor prognosis postsurgery, but the survival of locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients receiving nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine regimen chemotherapy had been improved[7]. Another study showed that tumour size, tumour-lymph node-metastasis (TNM) stage and distant metastasis were significantly correlated with overall survival (OS) in pancreatic cancer[8]. Computed tomography (CT) imaging has been widely used in the diagnosis, staging and treatment planning of pancreatic cancer[9]. Pancreatic cancer tumours generally show a low enhancement pattern compared with normal pancreatic tissue[10]. CT texture analysis is also used to evaluate the prognosis of pancreatic cancer[11,12]. Low vascular distribution and high metabolism in pancreatic cancer are important factors in evaluating invasiveness[13].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of preoperative enhanced CT as a quantitative imaging biomarker in patients with pancreatic cancer based on the imaging characteristics of poor blood supply and CT examination.

The Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, Fuzhou, China, approved this retrospective study and waived the requirement for informed consent (No. 2020KY0141).

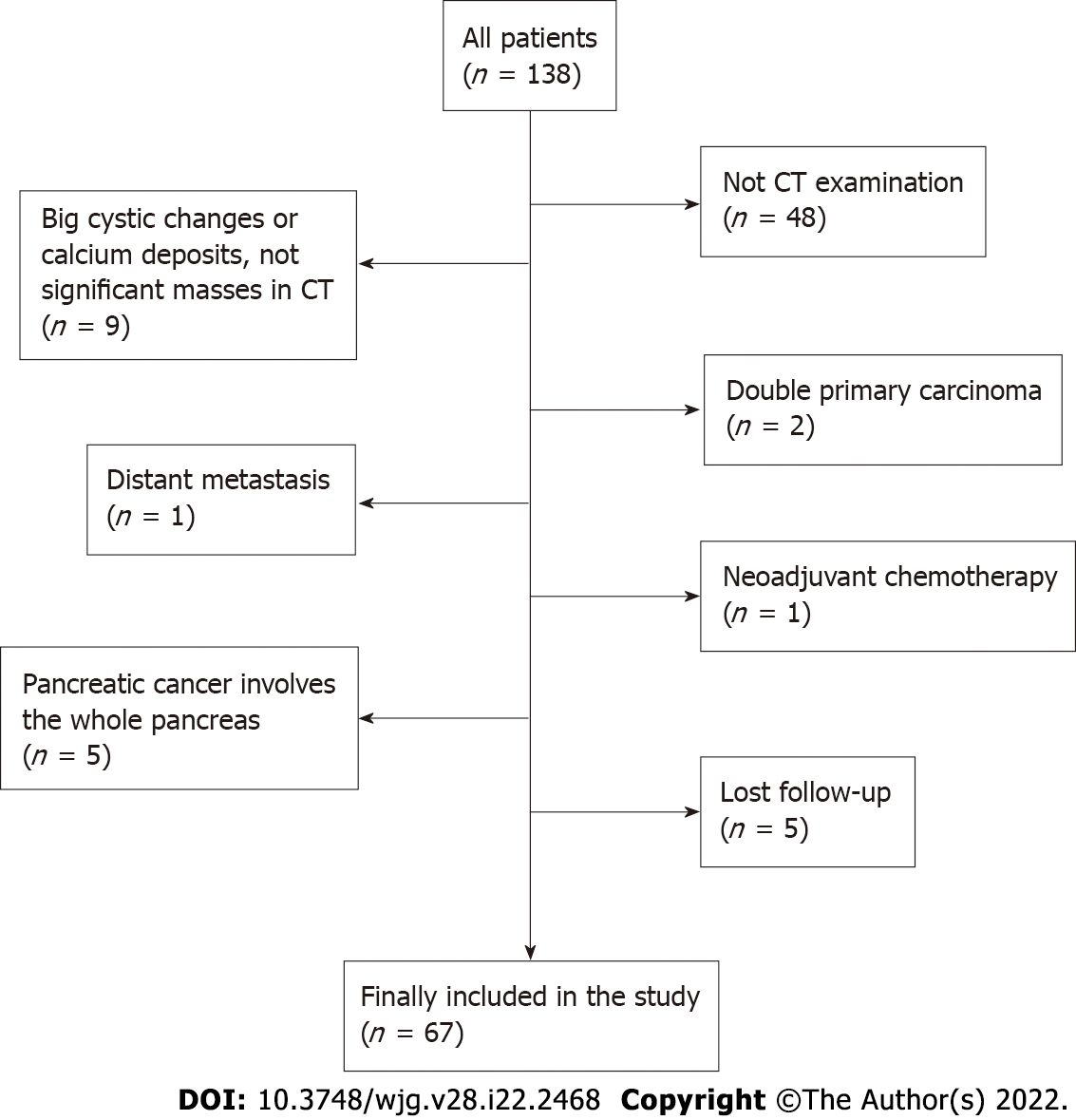

From March 2011 to May 2018, a total of 138 consecutive patients diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical resection in our department were reviewed. The last follow-up time was February 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age over 18 years; (2) no neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and no previous history of gastrointestinal and pancreatic surgery; (3) nonenhanced and enhanced CT performed within 30 days before surgery; and (4) pancreatic adenocarcinoma confirmed by postoperative pathology. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Stage IV pancreatic cancer; (2) severe complications or multiple primary cancers; (3) obvious pancreatic parenchymal atrophy, large cystic changes of the tumour and calcareous deposition; and (4) loss to follow-up. Patient sex, age, preoperative CT images, preoperative serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), tumour site, tumour size, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (2017) TNM staging, lymph node metastasis, postoperative pathology and differentiation grade, postoperative OS and other data were collected for analysis.

CT examination was performed on a 16-row CT scanner (Bright Speed Elite, GE Health care, United States) or a 64-row CT scanner (Discovery CT750 HD, GE Health care, United States). The CT scanning parameters for all phases were as follows: Gantry rotation speed, 0.5 s; tube voltage, 120 kVp; effective amperage, 210 mAs-260 mAs; matrix, 512 × 512; field of view, 350 mm-512 mm; and slice thickness, 5-10 mm. After a nonenhanced scan, 1.5 mL/kg of nonionic contrast agent (ioversol injection, 320 mg of iodine per millilitre, Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co., LTD, Jiangsu Province, China) was injected with an automatic syringe at 3.0 mL/s. Using the bolus-tracking technique, a pancreatic parenchymal (PP) phase scan was performed 7 s after the enhanced value of the descending aorta at the aortic hiatus reached 150 HU, and a portal venous (PV) phase scan was performed 25 s after the PP phase scan. CT imaging data were uploaded to the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) (Guangzhou YLZ Ruitu Information Technology Co., LTD, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China). In the process of collecting and reviewing the CT imaging results of the patient’s imaging data, we tried our best to make the quality of each patient’s tumour image meet our requirements.

The CT images and tumour relative enhanceement ratio (TRER) were analysed by two experienced radiologists using PACS. The region of the overall tumour (ROT) was delineated along the tumour edge at the largest and most visible level. Four regions of interest (ROIs) with diameters of 0.2-0.3 cm were randomly selected from the normal pancreatic tissue that were more than 1.0 cm away from ROT while avoiding obvious blood vessels, pancreatic ducts, pancreatic fissures and sites susceptible to intestinal gas interference. The average CT values of these 4 ROIs were used as CT values of pancreatic tissue outside the tumour (PTOT).

Tumour enhancement amplitude (TEA) = ROT value of the PV phase – ROT value of the nonenha

Pancreas enhancement amplitude outside tumour (PEA) = PTOT value of the PV phase – PTOT value of the nonenhancement phase.

TRER = TEA/PEA.

SPSS 25.0 for Windows software from IBM was used to establish a database for statistical analysis. Among the patients’ baseline data, those with a normal distribution of measurement data were represented by the mean ± SD, and an independent sample t test was used for comparisons between groups. The data with a nonnormal distribution were represented by the median and interquartile spacing, and comparisons between groups were tested by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Enumeration data were expressed in terms of frequency, and comparisons between groups were performed by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. In the analysis of the relationship between TRER and OS, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn. When the ROC curve was obtained, the “Coordinates of the Curve” and the corresponding “Sensitivity” and “1-Specificity” could be obtained, and their corresponding Youden indices could be calculated. The TRER corresponding to the maximum value of all Youden indices was the cut-off value of the ROC curve. The patients were divided into two groups according to the cut-off value. The corresponding survival curve was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method (log-rank test). Cox regression was performed for the univariate (enter model) and multivariate analyses (forward LR model). In the case of correlation analysis between TRER and clinicopathological characteristics, when the clinicopathological features were grouped as unordered categorical variables, the chi-squared test was used for analysis and the Cramer’s V correlation coefficient was calculated; When the clinicopathological features were grouped as ordinal categorical variables, Spearman rank correlation was used for analysis and the Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated. The results were considered statistically significant below the bilateral 5% significance level.

Of 138 patients, a total of 71 were excluded from the study (a flowchart of patient selection is shown in Figure 1). Ultimately, 67 patients were enrolled in the study. The clinical characteristics of the 67 patients in our study are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of 67 patients was 60.2 ± 10.0 (range, 35-80) years old, with 42 males (62.7%). The tumour was located in the head or uncinate of the pancreas in 44 patients (65.7%) and other sites in 23 patients (34.3%). The median postoperative OS of all patients was 12.3 mo (range, 1.7-42.8 mo).

| Patient characteristics | n = 67 |

| Age (yr) | |

| ≤ 60 | 31 (46.3) |

| > 60 | 36 (53.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 42 (62.7) |

| Female | 25 (37.3) |

| Tumour location | |

| Head/uncinate | 44 (65.7) |

| Body/tail | 23 (34.3) |

| CA19-9 | |

| < 37 ng/mL | 20 (29.9) |

| ≥ 37 ng/mL | 47 (70.1) |

| AJCC stage (2017) | |

| I | 11 (16.4) |

| II | 27 (40.3) |

| III | 29 (43.3) |

| Tumour differentiation | |

| Highly/moderately | 49 (73.1) |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 18 (26.9) |

| Surgical margin | |

| Negative | 57 (85.1) |

| Positive | 10 (14.9) |

| Vascular invasion | |

| No | 51 (76.1) |

| Yes | 16 (23.9) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| No | 33 (49.3) |

| Yes | 34 (50.7) |

The CT values of the nonenhancement and PV phases in tumour and extratumoural regions are shown in Table 2. The median TRER was 0.57 (interquartile range, 0.41-0.78).

| Location, phase and TRER | Value |

| ROT | |

| Nonenhancement phase (HU) | 36.1 (31.0-39.2) |

| PV phase (HU) | 58.0 (50.3-70.0) |

| PTOT | |

| Nonenhancement phase (HU) | 43.5 (36.8-48.1) |

| PV phase (HU) | 82.7 (71.8-98.4) |

| TRER | 0.57 (0.41-0.78) |

In the analysis of CT images, we also found that the CT values of ROT and PTOT gradually increased from the nonenhancement phase to the PV phase, but not all CT values of the PV phase were higher than those of the PP phase (Table 3).

| CT enhancement situation (PV phase and PP phase) | No. of patients (n) | |

| PV phase > PP phase | PV phase < PP phase | |

| ROT | 64 | 3 |

| PTOT | 50 | 17 |

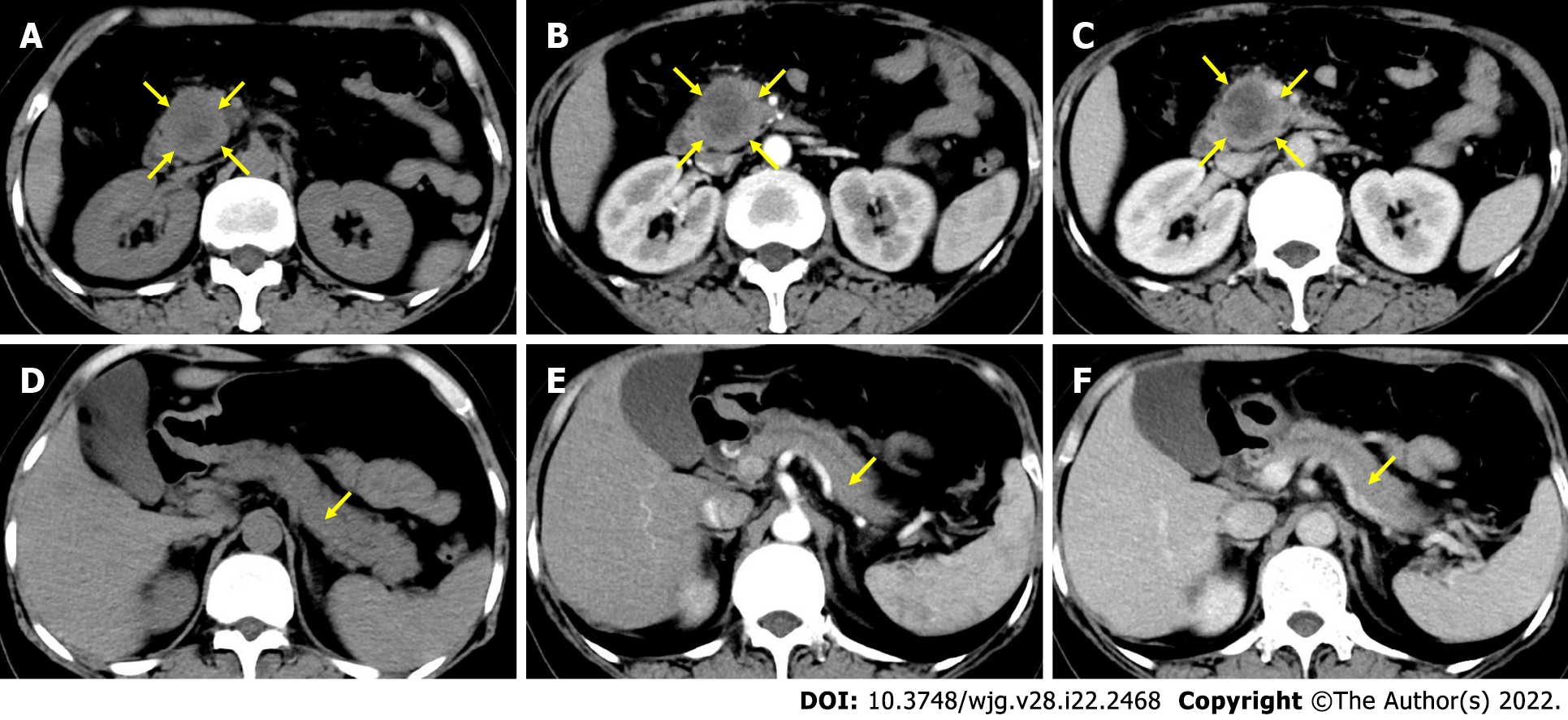

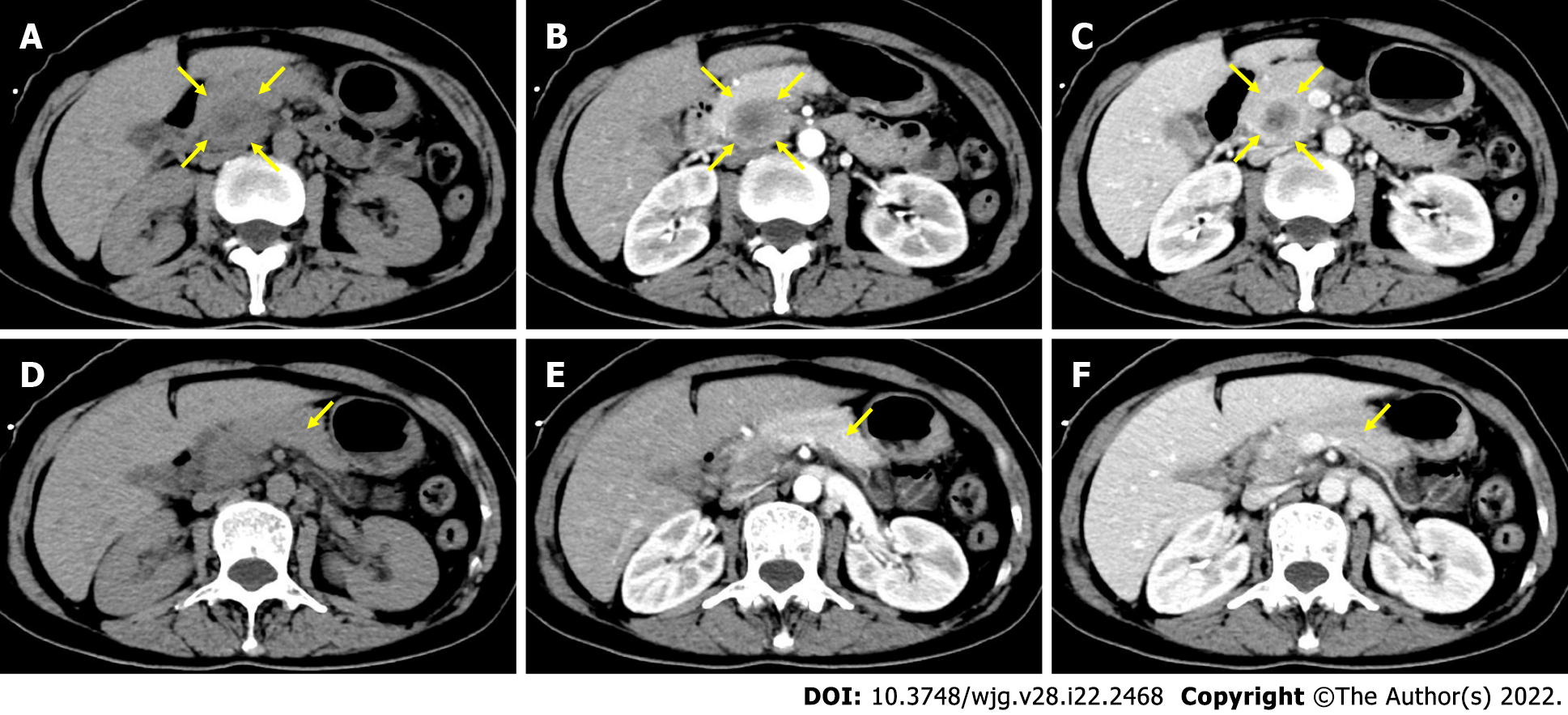

The ROC curve was drawn according to TRER, as shown in Figure 2A. The area under the curve of the ROC curve was 0.768 (P = 0.007). The cut-off value of the ROC curve was calculated to be 0.7, and the patients were classified according to the cut-off value. TRER ≤ 0.7 was defined as the low-enhancement group, TRER > 0.7 was defined as the high-enhancement group, and the Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis results showed that the median survival (10.0 mo) with TRER ≤ 0.7 was significantly worse than that (22.0 mo) with TRER > 0.7 (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). Typical CT images of the low- and high-enhancement groups are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively.

There was no significant difference in age, sex, tumour location, CA19-9, tumour differentiation, vascular invasion, surgical margin or adjuvant chemotherapy distribution between the low-and high-enhancement groups except the AJCC stage (P = 0.015) (Table 4).

| Variable | TRER ≤ 0.7, No. of patients, n (%) | TRER > 0.7, No. of patients, n (%) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.397 | ||

| ≤ 60 | 22 (50.0) | 9 (39.1) | |

| > 60 | 22 (50.0) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Sex | 0.170 | ||

| Male | 25 (56.8) | 17 (73.9) | |

| Female | 19 (43.2) | 6 (26.1) | |

| Tumour location | 0.117 | ||

| Head/uncinate | 26 (59.1) | 18 (78.3) | |

| Body/tail | 18 (40.9) | 5 (21.7) | |

| CA19-9 | 0.230 | ||

| < 37 ng/mL | 11 (25.0) | 9 (39.1) | |

| ≥ 37 ng/mL | 33 (75.0) | 14 (60.9) | |

| AJCC stage (2017) | 0.015 | ||

| I | 4 (9.1) | 7 (30.4) | |

| II | 16 (36.4) | 11 (47.8) | |

| III | 24 (54.5) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Tumour differentiation | 0.634 | ||

| Highly/moderately | 33 (75.0) | 16 (69.6) | |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 11 (25.0) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.071 | ||

| No | 30 (68.2) | 21 (91.3) | |

| Yes | 14 (31.8) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Surgical margin | 0.501 | ||

| Negative | 36 (81.8) | 21 (91.3) | |

| Positive | 8 (18.2) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.087 | ||

| No | 25 (56.8) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Yes | 19 (43.2) | 15 (65.2) |

Univariate and multivariate analyses of Cox regression were performed for clinical data and TRER (Tables 5 and 6). In the univariate analysis, AJCC stage (P = 0.005), preoperative CA19-9 (P = 0.033), postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.000) and TRER (P = 0.001) were significantly correlated with postoperative OS, while other factors had no significant influence on postoperative OS. In the multivariate analysis, preoperative CA19-9 (P = 0.015), tumour differentiation (P = 0.001), surgical margin (P = 0.008), postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.000) and TRER (P = 0.009) were significantly correlated with postoperative OS.

| Variable | No. of patients, n (%) | No. of events | Median OS (mo) (95%CI) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.699 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 31 (46.3) | 27 | 14.6 (9.1-20.0) | |

| > 60 | 36 (53.7) | 30 | 10.2 (5.7-14.7) | |

| Sex | 0.651 | |||

| Male | 42 (62.7) | 34 | 10.2 (4.3-16.1) | |

| Female | 25 (37.3) | 23 | 13.6 (9.2-18.1) | |

| Tumour location | 0.836 | |||

| Head/uncinate | 44 (65.7) | 36 | 12.0 (7.7-16.3) | |

| Body/tail | 23 (34.3) | 21 | 12.8 (4.1-21.6) | |

| AJCC stage (2017) | 0.005 | |||

| I | 11 (16.4) | 6 | 27.3 (14.9-39.6) | |

| II | 27 (40.3) | 23 | 12.0 (10.2-13.8) | |

| III | 29 (43.3) | 28 | 8.9 (5.0-12.7) | |

| CA19-9 | 0.033 | |||

| < 37 ng/mL | 20 (29.9) | 14 | 15.8 (10.4-21.2) | |

| ≥ 37 ng/mL | 47 (70.1) | 43 | 11.3 (7.2-15.3) | |

| Tumour differentiation | 0.255 | |||

| Highly/moderately | 49 (73.1) | 42 | 14.7 (11.9-17.6) | |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 18 (26.9) | 15 | 8.2 (5.7-10.7) | |

| Surgical margin | 0.141 | |||

| Negative | 57 (85.1) | 47 | 12.3 (7.5-17.1) | |

| Positive | 10 (14.9) | 10 | 12.0 (2.9-21.1) | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.435 | |||

| No | 51 (76.1) | 41 | 12.3 (7.7-16.9) | |

| Yes | 16 (23.9) | 16 | 12.0 (4.8-19.2) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.000 | |||

| No | 33 (49.3) | 32 | 8.2 (6.6-9.7) | |

| Yes | 34 (50.7) | 25 | 17.7 (14.4-20.9) | |

| TRER | 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 0.7 | 44 (65.7) | 42 | 10.0 (5.9-14.1) | |

| > 0.7 | 23 (34.3) | 15 | 22.0 (12.4-31.6) |

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| CA19-9 (ng/mL) | 2.279 | 1.174-4.422 | 0.015 |

| Tumour differentiation | 3.057 | 1.585-5.898 | 0.001 |

| Surgical margin | 2.860 | 1.315-6.222 | 0.008 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.200 | 0.106-0.380 | 0.000 |

| TRER | 0.432 | 0.229-0.812 | 0.009 |

A correlation analysis was conducted between TRER and clinicopathological characteristics (Table 7). The results showed that TRER was not significantly correlated with tumour location, preoperative serum CA19-9, lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, or tumour differentiation (all P > 0.05). However, TRER was significantly correlated with AJCC stage (P = 0.003, Spearman correlation coefficient = -0.353), T stage (P = 0.005, Cramer’s V correlation coefficient = 0.343), and N stage (P = 0.046, Spearman correlation coefficient = -0.245). The analysis of the relationship between TRER and tumour size showed that TRER was negatively correlated with tumour size (P = 0.001) (Figure 5).

| Variable | TRER ≤ 0.7, No. of patients, n (%) | TRER > 0.7, No. of patients, n (%) | P value | Coefficient of correlation |

| Tumour location | 0.117 | 0.192 | ||

| Head/uncinate | 26 (59.1) | 18 (78.3) | ||

| Body/tail | 18 (40.9) | 5 (21.7) | ||

| CA19-9 | 0.230 | 0.147 | ||

| < 37 ng/mL | 11 (25.0) | 9 (39.1) | ||

| ≥ 37 ng/mL | 33 (75.0) | 14 (60.9) | ||

| AJCC stage (2017)1 | 0.003 | -0.353 | ||

| I | 4 (9.1) | 7 (30.4) | ||

| II | 16 (36.4) | 11 (47.8) | ||

| III | 24 (54.5) | 5 (21.7) | ||

| T stage | 0.005 | 0.343 | ||

| T1/2 | 13 (29.5) | 15 (65.2) | ||

| T3/4 | 31 (70.5) | 8 (34.8) | ||

| N stage1 | 0.046 | -0.245 | ||

| N0 | 12 (27.3) | 11 (47.8) | ||

| N1 | 15 (34.1) | 8 (34.8) | ||

| N2 | 17 (38.6) | 4 (17.4) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.138 | 0.181 | ||

| Negative | 13 (29.5) | 11 (47.8) | ||

| Positive | 31 (70.5) | 12 (52.2) | ||

| Vascular invasion | 0.071 | 0.258 | ||

| No | 30 (68.2) | 21 (91.3) | ||

| Yes | 14 (31.8) | 2 (8.7) | ||

| Tumour differentiation | 0.634 | 0.058 | ||

| Highly/moderately | 33 (75.0) | 16 (69.6) | ||

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 11 (25.0) | 7 (30.4) |

Pancreatic cancer is a tumour with a very poor prognosis. CT plays important roles in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and the evaluation of the relationship between tumours and peripheral blood vessels. Our study found the clinical value of enhanced CT as a quantitative image in predicting the prognosis of pancreatic cancer.

For patients with pancreatic cancer, TNM staging, tumour size, lymph node positive rate, log odds of positive lymph nodes, R0 resection and other factors are related to patient recurrence-free survival and OS[14-16]. Our analysis results showed that patients in the low TRER group were more likely to have higher TNM stage, T stage and N stage, and TRER was significantly negatively correlated with tumour size, demonstrating that TRER could be used to predict the postoperative OS of pancreatic cancer. However, in our study, the tumour stage (AJCC) was significant in the univariate analysis but not in the multivariate analysis. This difference might be due to the relatively small sample size. Many imaging techniques combining qualitative and quantitative information with pathological findings of the tumour have been used to analyse the aggressiveness of the tumour to determine the prognosis of the patient from preoperative imaging information. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT (DCE-CT) also shows potential value in predicting tumour response to treatment and outcome[17,18].

Currently, the qualitative analysis of CT images has gained increasing attention for the prognostic analysis of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, unlike other solid tumours, is known as a cold tumour with insufficient blood supply. The pathological type of 90% pancreatic cancer is invasive ductal adenocarcinoma, which is one of the most stromal malignant tumours[19,20]. The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ, very close to the common hepatic artery, celiac artery, portal vein, superior mesenteric vessels, and splenic vessels. As pancreatic cancer progresses, it has early infiltration or perivascular desmoplastic reactions, which can influence its direct blood supply. The correlation analysis in our study showed that the vascular invasion rate in the low TRER group was higher (31.8%) than that in the high TRER group (8.7%), but P = 0.071, which might be due to the relatively small sample size.

In our study, we did not find any relationship between TRER and pathological differentiation of pancreatic cancer. However, a previous study on DCE-CT showed that pancreatic tumour CT enhancement was negatively correlated with pathological grade and the degree of malignancy[21,22]. In pancreatic cancer, fibroblast hyperplasia and vascular reduction are caused by a high fibrinolysis response, which results in a low-enhancement CT pattern compared with PTOT[23]. Some studies have shown that there is no significant difference in the perfusion values of the pancreatic head, body and tail in normal pancreatic tissues, while the perfusion values and blood flow in the tumour centre of pancreatic cancer patients are lower than those of PTOT[24,25]. Some researchers have reported that necrosis within pancreatic adenocarcinoma influences tumour enhancement on CT[26,27]. Tumour necrosis is the final result of hypoxia, which can accelerate the progression of malignant tumours[28,29]. It is well known that larger tumours are more prone to necrosis. The indirect relationship between large tumours and weakened CT enhancement was confirmed in our research. The TRER also indirectly reflects the necrosis of the tumour. A previous study showed that patients with low CT values in pancreatic tumours at the parenchymal stage, portal venous stage, and delayed stage had shorter postoperative survival times in the univariate analysis, whereas the CT values at the pancreatic tumour parenchymal stage were positively correlated with prognosis in the multivariate analysis[30]. When Cassinotto et al[31] measured the average attenuation value of the overall tumour and the lowest attenuation value in the tumour centre at the PV phase, they found that lower attenuation values at the PV phase reflected higher degree of malignancy, more likely lymph node invasion, and shorter disease-free survival. The lowest attenuation in the tumour centre also reflected the degree of necrosis within the tumour tissue. However, if only the changes in pancreatic tumours after CT enhancement were analysed, it would be easy to ignore the changes in PTOT. Due to the lack of control, the difference in enhancement amplitude between ROT and PTOT could not be analysed, which would lead to the inability to analyse whether the change was caused by the tumour itself or by the blood supply of the pancreatic organs as a whole. Visually isoattenuating pancreatic cancer is defined as when the attenuation of the tumour, compared with the pancreatic parenchyma, is not visually observed to increase or decrease at both arterial and portal venous phases. In this type of tumour, the number of cancer cells is lower, the degree of tumour necrosis is lower, the prognosis is better, and an increase in serum CA19-9 is rare[27]. In our study, although the scanning period selected was the nonenhancement and PV phases, which were different from the study of visually isoattenuating pancreatic cancer, they essentially reflected the increase in tumour CT value after enhanced CT examination, and the results were similar; that is, patients with lower tumour CT enhancement amplitude had shorter OS. At the same time, we found no correlation between TRER and the increase in CA19-9. In Zhu et al's study, the relative enhancement change (REC) was defined as the proportion of enhancement change between the tumour and pancreatic parenchyma during the PP and PV phases, showing that the postoperative OS of patients with REC < 0.9 was worse than those with REC ≥ 0.9[32]. Pancreatic cancer tissues are rich in fibrous tissue and show a pattern of delayed enhancement. However, our data showed that not all CT values of the PV phase were higher than those of the PP phase, regardless of ROT or PTOT. The CT value of the PV phase minus that of the PP phase may be negative. Therefore, when we designed the study, CT values of the PV and nonenhancement phases were selected for comparison. The final results showed that patients with a smaller TRER had worse a prognosis.

Although TRER is associated with AJCC stage, T stage, and N stage, it is not a substitute for lymph node status, tumour size, or stage. Pancreatic cancer is a kind of cold tumour with abundant stroma, and the stroma contributes to tumour growth and progression and plays an important role in the chemoresistance. This pathological feature of pancreatic cancer is similar to the pathological differentiation of tumours. It represents the characteristics of the pathology and growth of pancreatic cancer itself and will not disappear because the tumour is removed. The low-enhancement mode of CT in pancreatic cancer is partly due to the high stromal ratio of pancreatic cancer. Based on this, TRER is used as a quantitative reflection of the low-enhancement mode of CT in pancreatic cancer and the richness of pancreatic cancer stroma, which is used to predict postoperative OS. Moreover, because the postoperative prognosis of patients with low TRER is poor, such patients can consider whether to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Because tumour heterogeneity is affected by tumour blood supply, the ratio of tumour cells to stromal cells and tumour necrosis will lead to different CT values in different parts of the tumour. Although whole-volume quantitative analysis of tumour CTs is currently available, it has not been analysed in our study for the following reasons: (1) At the largest and most visible level of the tumour in CT images, the change of the tumour relative to surrounding tissue is relatively obvious, and it is easy to identify the boundary of the tumour. Moreover, it is simple to obtain the average CT value of ROT; and (2) compared with the largest level of the tumour, the CT value of the whole volume may be more easily affected by the obvious blood vessels and dilated pancreatic duct in the tumour.

There are several limitations in our study: (1) This was a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size at a single institution; (2) patients with metastasis were not studied; and (3) patients received a variety of postoperative treatments, making it difficult to further accurately classify and perform a survival analysis, which might lead to a degree of bias.

In conclusion, TRER is a quantitative index of CT enhancement. This study showed that when the TRER of pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients was not more than 0.7, the prognosis was significantly worse, demonstrating the prognostic value of preoperative enhanced CT as a quantitative imaging biomarker in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Computed tomography (CT) is widely used in the diagnosis, staging and treatment of pancreatic tumours. Because being rich in stroma, pancreatic cancer generally shows a low enhancement pattern compared with normal pancreatic tissue.

We want to use preoperative enhanced CT as a quantitative imaging biomarker to accurately predict the prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer.

To analyse prognostic value of preoperative enhanced CT in pancreatic cancer.

Sixty-seven patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoing pancreatic resection were enrolled retrospectively. All patients underwent preoperative unenhanced and enhanced CT examination, the CT values of which were measured. The ratio of the preoperative CT value increase from the nonenhancement phase to the portal venous phase between pancreatic tumour and normal pancreatic tissue was calculated. The cut-off value of ratios was obtained by the receiver operating characteristic curve of the tumour relative enhancement ratio (TRER), according to which patients were divided into low- and high-enhancement groups. Cox regression was performed for the univariate (enter model) and multivariate analyses (forward LR model). Finally, Spearman rank correlation or chi-square test was used to analyse the correlation between TRER and clinicopathological characteristics.

TRER is a quantitative index of enhancement CT. This study showed that the prognosis of patients with the TRER ≤ 0.7 was significantly worse. TRER is a simple and effective parameter. Our results demonstrated that patients in the low TRER group were more likely to have higher American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, tumour stage, lymph node stage, and TRER was significantly negatively correlated with tumour size.

TRER is a quantitative indicator of enhanced CT and can be used to predict postoperative overall survival in pancreatic cancer.

In the future, we will further study the value of preoperative enhanced CT in predicting the efficacy of chemotherapy.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15625] [Article Influence: 2232.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 2. | Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:607-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2129] [Cited by in RCA: 2182] [Article Influence: 145.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C, Gutberlet K, Kettner E, Schmalenberg H, Weigang-Koehler K, Bechstein WO, Niedergethmann M, Schmidt-Wolf I, Roll L, Doerken B, Riess H. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1779] [Cited by in RCA: 1791] [Article Influence: 94.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yoshitomi H, Togawa A, Kimura F, Ito H, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, Otsuka M, Kato A, Nozawa S, Furukawa K, Miyazaki M; Pancreatic Cancer Chemotherapy Program of the Chiba University Department of General Surgery Affiliated Hospital Group. A randomized phase II trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil/tegafur and gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2448-2456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Zhu H, Augustine MM, Porembka MR, Wang SC, Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Choti MA, Polanco PM. Neoadjuvant Therapy Followed by Resection Versus Upfront Resection for Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Propensity Score Matched Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:515-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Henriksen A, Dyhl-Polk A, Chen I, Nielsen D. Checkpoint inhibitors in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;78:17-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shi S, Liang C, Xu J, Meng Q, Hua J, Yang X, Ni Q, Yu X. The Strain Ratio as Obtained by Endoscopic Ultrasonography Elastography Correlates With the Stroma Proportion and the Prognosis of Local Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg. 2020;271:559-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bakkevold KE, Kambestad B. Staging of carcinoma of the pancreas and ampulla of Vater. Tumor (T), lymph node (N), and distant metastasis (M) as prognostic factors. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;17:249-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hong SB, Lee SS, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Byun JH, Hong SM, Song KB, Kim SC. Pancreatic Cancer CT: Prediction of Resectability according to NCCN Criteria. Radiology. 2018;289:710-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hattori Y, Gabata T, Zen Y, Mochizuki K, Kitagawa H, Matsui O. Poorly enhanced areas of pancreatic adenocarcinomas on late-phase dynamic computed tomography: comparison with pathological findings. Pancreas. 2010;39:1263-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sandrasegaran K, Lin Y, Asare-Sawiri M, Taiyini T, Tann M. CT texture analysis of pancreatic cancer. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1067-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim HS, Kim YJ, Kim KG, Park JS. Preoperative CT texture features predict prognosis after curative resection in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Komar G, Kauhanen S, Liukko K, Seppänen M, Kajander S, Ovaska J, Nuutila P, Minn H. Decreased blood flow with increased metabolic activity: a novel sign of pancreatic tumor aggressiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5511-5517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | van Roessel S, Kasumova GG, Verheij J, Najarian RM, Maggino L, de Pastena M, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Salvia R, Ng SC, de Geus SW, Lof S, Giovinazzo F, van Dam JL, Kent TS, Busch OR, van Eijck CH, Koerkamp BG, Abu Hilal M, Bassi C, Tseng JF, Besselink MG. International Validation of the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging System in Patients With Resected Pancreatic Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e183617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | You MS, Lee SH, Choi YH, Shin BS, Paik WH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Jang DK, Lee JK, Kwon W, Jang JY, Kim SW. Lymph node ratio as valuable predictor in pancreatic cancer treated with R0 resection and adjuvant treatment. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Demir IE, Jäger C, Schlitter AM, Konukiewitz B, Stecher L, Schorn S, Tieftrunk E, Scheufele F, Calavrezos L, Schirren R, Esposito I, Weichert W, Friess H, Ceyhan GO. R0 Versus R1 Resection Matters after Pancreaticoduodenectomy, and Less after Distal or Total Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg. 2018;268:1058-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Miles KA, Lee TY, Goh V, Klotz E, Cuenod C, Bisdas S, Groves AM, Hayball MP, Alonzi R, Brunner T; Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre Imaging Network Group. Current status and guidelines for the assessment of tumour vascular support with dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1430-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | García-Figueiras R, Goh VJ, Padhani AR, Baleato-González S, Garrido M, León L, Gómez-Caamaño A. CT perfusion in oncologic imaging: a useful tool? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:8-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cascinu S, Falconi M, Valentini V, Jelic S; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v55-v58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Feig C, Gopinathan A, Neesse A, Chan DS, Cook N, Tuveson DA. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266-4276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 841] [Cited by in RCA: 1064] [Article Influence: 81.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang SH, Sun YF, Liu Y, Zhou Y. CT contrast enhancement correlates with pathological grade and microvessel density of pancreatic cancer tissues. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5443-5449. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Seo W, Kim YC, Min SJ, Lee SM. Enhancement parameters of contrast-enhanced computed tomography for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Correlation with pathologic grading. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:4151-4158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cho HW, Choi JY, Kim MJ, Park MS, Lim JS, Chung YE, Kim KW. Pancreatic tumors: emphasis on CT findings and pathologic classification. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12:731-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Delrue L, Blanckaert P, Mertens D, Cesmeli E, Ceelen WP, Duyck P. Assessment of tumor vascularization in pancreatic adenocarcinoma using 128-slice perfusion computed tomography imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35:434-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Klauss M, Stiller W, Fritz F, Kieser M, Werner J, Kauczor HU, Grenacher L. Computed tomography perfusion analysis of pancreatic carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Demachi H, Matsui O, Kobayashi S, Akakura Y, Konishi K, Tsuji M, Miwa A, Miyata S. Histological influence on contrast-enhanced CT of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21:980-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim JH, Park SH, Yu ES, Kim MH, Kim J, Byun JH, Lee SS, Hwang HJ, Hwang JY, Lee MG. Visually isoattenuating pancreatic adenocarcinoma at dynamic-enhanced CT: frequency, clinical and pathologic characteristics, and diagnosis at imaging examinations. Radiology. 2010;257:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Büchler P, Reber HA, Lavey RS, Tomlinson J, Büchler MW, Friess H, Hines OJ. Tumor hypoxia correlates with metastatic tumor growth of pancreatic cancer in an orthotopic murine model. J Surg Res. 2004;120:295-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guillaumond F, Leca J, Olivares O, Lavaut MN, Vidal N, Berthezène P, Dusetti NJ, Loncle C, Calvo E, Turrini O, Iovanna JL, Tomasini R, Vasseur S. Strengthened glycolysis under hypoxia supports tumor symbiosis and hexosamine biosynthesis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3919-3924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fukukura Y, Takumi K, Higashi M, Shinchi H, Kamimura K, Yoneyama T, Tateyama A. Contrast-enhanced CT and diffusion-weighted MR imaging: performance as a prognostic factor in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cassinotto C, Chong J, Zogopoulos G, Reinhold C, Chiche L, Lafourcade JP, Cuggia A, Terrebonne E, Dohan A, Gallix B. Resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Role of CT quantitative imaging biomarkers for predicting pathology and patient outcomes. Eur J Radiol. 2017;90:152-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhu L, Shi X, Xue H, Wu H, Chen G, Sun H, He Y, Jin Z, Liang Z, Zhang Z. CT Imaging Biomarkers Predict Clinical Outcomes After Pancreatic Cancer Surgery. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Casà C, Italy; Lee Y, South Korea; Singh I, United States S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP