Published online Jul 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i28.4582

Peer-review started: January 28, 2021

First decision: May 2, 2021

Revised: May 28, 2021

Accepted: June 22, 2021

Article in press: June 22, 2021

Published online: July 28, 2021

Processing time: 178 Days and 16.6 Hours

In solid tumors, the development of vasculature is, to some extent, slower than the proliferation of the different types of cells that form the tissue, both cancer and stroma cells. As a consequence, the oxygen availability is compromised and the tissue evolves toward a condition of hypoxia. The presence of hypoxia is variable depending on where the cells are localized, being less extreme at the periphery of the tumor and more severe in areas located deep within the tumor mass. Surprisingly, the cells do not die. Intracellular pathways that are critical for cell fate such as endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, autophagy, and others are all involved in cellular responses to the low oxygen availability and are orchestrated by hypoxia-inducible factor. Oxidative stress and inflammation are critical conditions that develop under hypoxia. Together with changes in cellular bioenergetics, all contribute to cell survival. Moreover, cell-to-cell interaction is established within the tumor such that cancer cells and the microenvironment maintain a bidirectional communication. Additionally, the release of extracellular vesicles, or exosomes, represents short and long loops that can convey important information regarding invasion and metastasis. As a result, the tumor grows and its malignancy increases. Currently, one of the most lethal tumors is pancreatic cancer. This paper reviews the most recent advances in the knowledge of how cells grow in a pancreatic tumor by adapting to hypoxia. Unmasking the physiological processes that help the tumor increase its size and their regulation will be of major relevance for the treatment of this deadly tumor.

Core Tip: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is characterized by high aggressiveness, therapeutic resistance, and mortality. The cells included in the mass, both tumor and those forming the stroma, have a high proliferative rate that leads to the rapid growth of the tumor. Because of this, the distribution of blood vessels is insufficient to supply oxygen to the cells, and hypoxia is a consequence. Cells escape from death and adapt by undergoing critical changes in intracellular pathways involved in energy supply, proliferation, and cell-to-cell communication.

- Citation: Estaras M, Gonzalez A. Modulation of cell physiology under hypoxia in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(28): 4582-4602

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i28/4582.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i28.4582

World Health Organization estimates that about 465.000 people died from pancreatic cancer (PC) in 2020, which was the seventh leading cause of cancer deaths[1]. Various studies point toward recent increases in the incidence of PC and in the number of PC-related deaths[2,3]. The causes of high mortality are late diagnosis and few and inef

Tumors conditions include the development of hypoxic areas of varying extent, in which the growing cell population is subjected to low O2 availability[5]. This condition derives from the high rate of cell proliferation and the rapid growth of the tumor mass, which is accompanied by an abnormal distribution of blood vessels that limits blood flow and, hence the O2 supply[6]. An ongoing hypoxic state has been well documented in PC. The average of O2 level in the healthy pancreas is 6.8%, whereas in PC it is 0.4%. This 17-fold decrease in O2 availability is high compared with other tumors[7]. Extensive fibrosis and hypovascularization are characteristic of PDAC, and lead to significant tissue hypoxia and the aggressiveness, therapeutic resistance, and high mortality that are characteristic of this type of cancer[8].

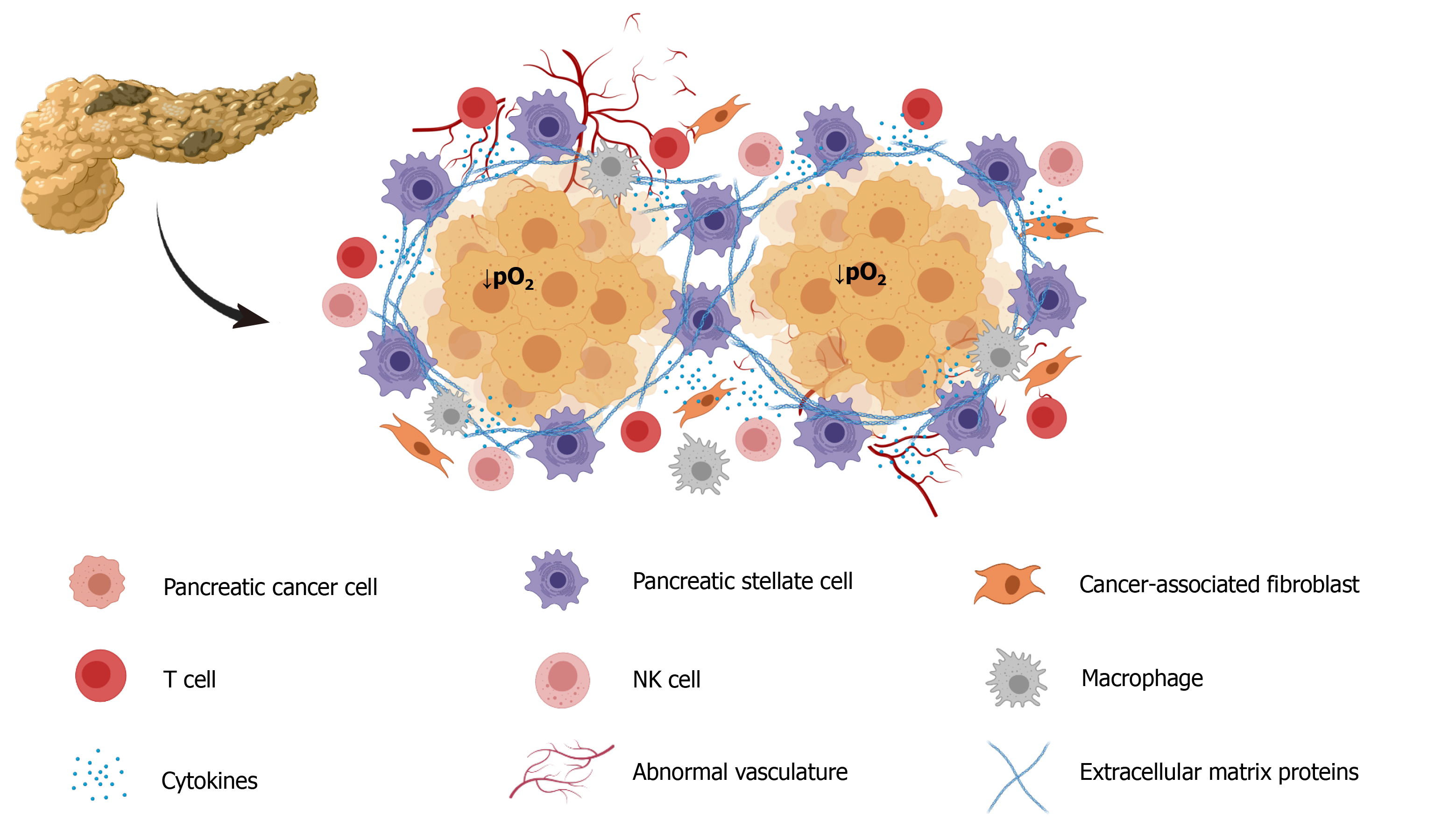

Not less important, the stroma that forms part of the tumor mass contributes to the creation of a tumor microenvironment that contributes to conditions that determine tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis[9]. The tumor microenvironment is composed of structural elements, which include extracellular matrix proteins and cells, such as macrophages, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and stellate cells[9,10]. Pancreatic stellate cells (PSC) interact closely with cancer cells and set up a close relationship that favors tumor growth[11]. Additionally, PSC are considered major contributors to the fibrosis that forms part the stroma[12]. Increased hypoxia promotes collagen deposition and tumor progression, i.e. hypoxia contributes to the development of fibrosis in PC and in other types of tumors[13]. Hypoxia promotes PSC activation, increased proliferation, and invasiveness, confirming their participation in the formation of fibrotic tissue[14].

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) plays a pivotal role in the development of cellular responses to hypoxia[15]. Usually, this factor promotes or represses the transcription of many of genes that are involved in cellular homeostasis. HIF is degraded, and hence is nonfunctional when O2 is available to the cells, but becomes active under specific conditions, including low-O2 (hypoxic) stress. The genes targeted by HIF allow cells to adapt to hypoxic conditions and survive. The genes involved code for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin, and glucose transporter-1[16]. In order to adapt to O2 deprivation, energy metabolism switches to glycolysis[17]. Concomitantly, regulation of the transcription of certain metabolic enzymes, including pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1, lactate dehydrogenase A, glycogen phosphorylase L, and others occur. The result is the improvement of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production at the expense of increases of glucose uptake, glycolysis, and generation of lactate[18].

Several isoforms of HIF have been identified. HIF-1α and HIF-2α are closely related, and HIF-1α is the first isoform that was described. Both activate the transcription of genes associated with hypoxia. HIF-3α is more distantly related. Current evidence indicates that HIF-1α, and not HIF-2α, is active in regulating the transcription of genes that encode the enzymes that coordinate the activation of cellular pathways related to ATP support[19]. HIF-1 is a major activator of pathways that play crucial roles in tumor development by upregulating pivotal genes. The genes thereafter regulate energy metabolism, angiogenesis, survival, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance of cancer cells[20]. The HIF-1α subunit is regulated by O2-dependent hydroxylation, ubiquitination, and degradation. In general, it is accepted that HIF signaling is activated in all types of cancer, including PC. Its activation will provide the tumor cells with tools to support survival. Therefore, HIF has been described as a key molecular target for cancer therapy. therapy[5,21]. To cite some examples, Xiao et al[22] showed that silencing the expression of HIF-1 diminished the invasiveness of Panc-1 and MiaPaca-2 cells. The enzyme prolyl hydroxylase domain 3 (PHD3) regulates the degradation of HIF and is the rate-limiting in that process. PHD3 is deregulated in PC cells. It has been shown that HIF-1α expression was suppressed in MiaPaca2 PC cells that overexpressed PHD3, which inhibited cell growth and colony formation under hypoxic conditions[19,23]. Another study showed that PHD3 expression regulated the secretion of VEGF evoked by hypoxia and inhibited tumor growth in vivo by abrogation of angiogenesis[24].

Along with cancer cells, the fibrotic tissue also undergoes adaptation to hypoxia by terms of HIF signaling. HIF-1α expression was found in the stroma adjacent to the PDAC cells[25]. HIF-1 and HIF-2 were expressed in cultured PSC subjected to hypoxia[14]. HIF-1 expression induced changes in PSC that promoted invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inhibited death of PC cells[22]. HIF-1α induced secretion of collagen in PSC. Accumulation of collagen together with other extracellular matrix components promotes fibrotic stroma formation[26]. Another study showed that HIF-1α promoted the activation of PSC through recruitment of macrophages in PDAC[27].

The growth of fibroblasts was accelerated by the release of sonic hedgehog protein (SHH) in PC cells that were subjected to hypoxia, and that situation contributed to increased deposition of fibrous tissue[28]. PC stromal fibroblasts subjected to hypoxia were found to be associated with aggressive invasion and liver metastasis and increased processing and release of hepatocyte growth factor activator[29]. Moreover, fibroblasts have been found to contribute to vascular remodeling under hypoxia by influencing VEGF expression[30]. Figure 1 is a depiction of all the cell types that can be included in tumor tissue. Depending on their location in the mass, all cells are subjected to hypoxia to different extents.

Cancer cells have high proliferation rates, altered metabolism, and increased oxidative stress. The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leads to genomic instability and the impairment of gene expression that underly cancer development[31]. ROS are produced in the mitochondria[32] and production is increased in tumor cells[6]. In healthy cells, uncontrolled overproduction of ROS is usually accompanied by cell death[33]. However, that does not necessarily happen in tumor cells, which can adapt to survive. Local expression of renin-angiotensin system has been signaled to play an important role in the regulation of blood pressure and fluid homeostasis in the pancreas[34]. Interestingly, hypoxia could upregulate the mentioned system that could then contribute to the modulation of local blood flow in a growing tumor and help the tissue to manage oxidative stress. Along this line, angiogenesis is a process that attempts to counter the lack of nutrients and oxygen shortage that develops in tumors[35]. However, in spite of the development of new microvasculature, vascular access is still poor and O2 supply is compromised in the majority of tumors[36]. In PDAC for example, a low microvessel density and collapsed vasculature are observed[37].

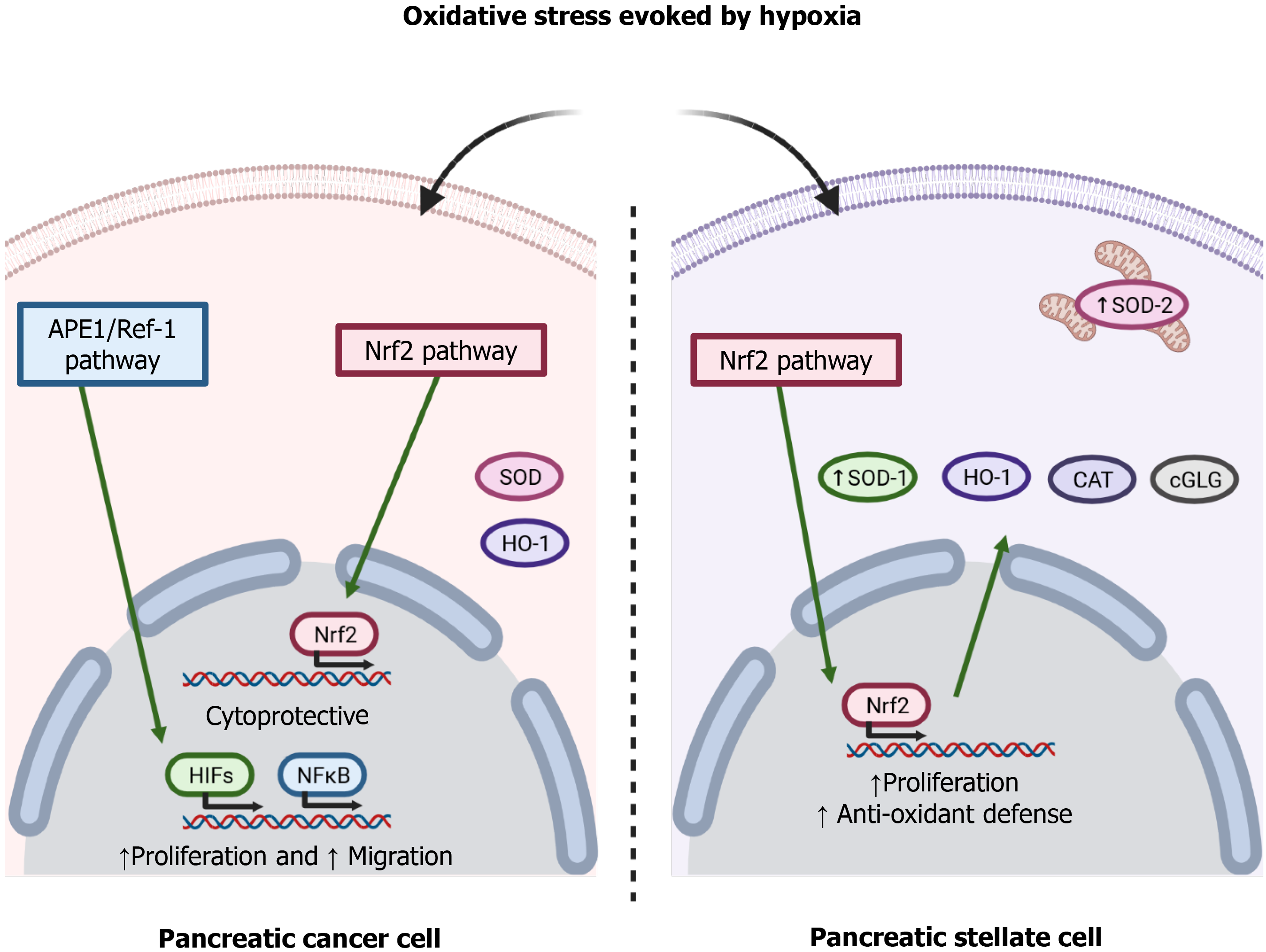

To adapt to the adverse pro-oxidative conditions derived from uncontrolled cell proliferation and a limited blood supply, cancer cells increase their antioxidant defenses[38]. The redox signaling protein apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1/Redox effector factor 1 (APE1/Ref-1) modulates the redox activity of PC cells and is involved in cell proliferation and migration through the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and HIF-1 pathways[39]. The transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2 (Nrf2) regulates a wide range of cytoprotective genes in response to oxidative stress and various stressors present in the extracellular environment. The glutathione system is key among the antioxidant systems that are regulated by this transcription factor[40]. Chronic hypoxia is known to increase glutathione-dependent antioxidant capacity, which avoids damage to the cell membrane because of concomitant oxidative stress[41]. Indeed, glutathione peroxidase maintains redox homeostasis in Panc1 cells, a pancreatic tumor cell line[42]. Heme oxygenase-1, an antioxidant enzyme regulated by Nrf2, has been shown to provide a survival advantage to PDAC cells subjected to hypoxia, and its inhibition induced an increase of the production of ROS and increased cell death[43]. Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are antioxidant enzymes that protect cells against ROS. The family consists of three isoforms, cytoplasmic Cu/ZnSOD (SOD1), mitochondrial MnSOD (SOD2), and extracellular Cu/ZnSOD (SOD3)[44]. A decrease in the expression of SOD1 has been related to a decrease in the viability of the pancreatic tumor cell lines Panc-1 and MiaPaCa2 cells when they were subjected to hypoxia[45]. SOD2 was shown to protect KP4 human pancreatic carcinoma cells against oxidative stress evoked by hypoxia/reoxygenation. The evidence thus supports the involvement of antioxidant enzymes in PC cell survival[6].

Interestingly, PSC undergo oxidative stress under hypoxia, and increased oxidation of lipids and proteins have been reported in PSC subjected to hypoxia. Moreover, PSC can adapt to hypoxia by increasing their antioxidant defenses by upregulated expression of SOD1 and SOD2 associated with increased phosphorylation of the Nrf2 transcription factor[14]. Figure 2 summarizes the involvement of the pathways involved in hypoxia-evoked antioxidant responses. In general, both the tumor cells and the other cells that grow in the mass adapt to varying extents. The overall success achieved by cellular responses determines the growth of the tumor and the probable concomitant migration, invasion, and metastasis[46].

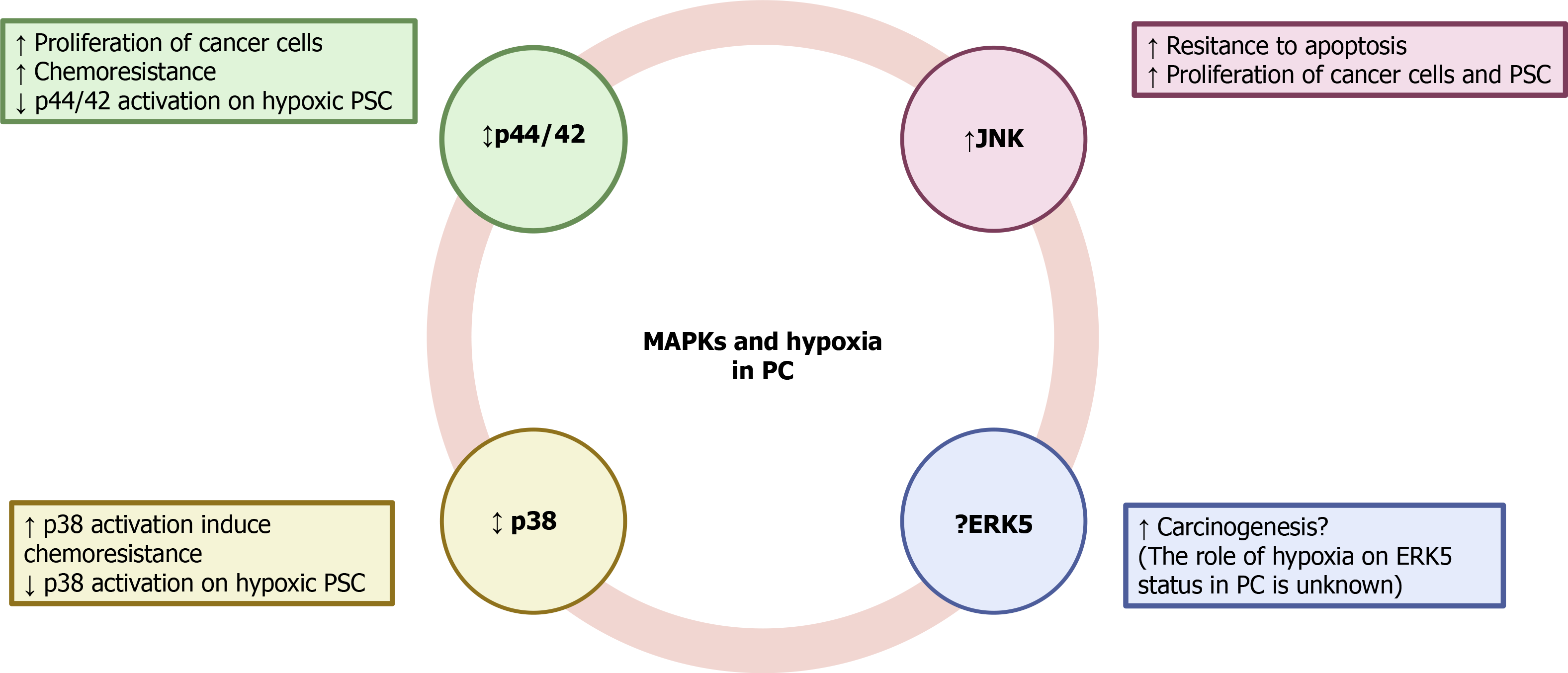

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) comprise a family of proteins that regulate various physiological processes. Among them, cell proliferation, differentiation and survival play major roles in cancer development and progression[47]. Participation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and c-Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK) in the growth of PC was demonstrated in KP-1N human pancreatic carcinoma cells that had been incubated with the secretagogue cholecystokinin[48]. Glucose deprivation, which was used to mimic hypoxia, induced the activation of JNK in the PC cells. Inhibition of the kinase led to a decrease of cell sensitivity to glucose deprivation-induced apoptosis[49]. JNK was also activated by interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3, a group of genes that are stimulated by interferon and upregulated in aggressive PC cells[50]. Pro-survival and proliferation pathways regulated by ERK1/2 have been reported in Panc-1 cells[51]. In Capan-2 cells, another human PC cell line, hypoxia upregulated ERK1/2 and activated HIF-1α, which conferred chemoresistance of cells to gemcitabine[52]. On the contrary, a decrease in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was accompanied by a drop in the proliferation of L3.6pl human PC cells[53]. ERK1/2 were also involved in the malignant transformation and development of PDAC under hypoxia; and as has been shown in other pancreatic tumor cell lines, implication of HIF-1α expression was also reported[54].

Involvement of p38 MAPK in the modulation of cancer cell survival has also been shown. Its inhibition protected of MiaPaCa2 cells from death in response to 15-deoxy-delta-prostaglandin J2[55]. Conversely, p38 was activated in MiaPaCa2 cells subjected to simulated ischemia, and led to activation of HIF-1α[56]. Moreover, inhibition of p38 in MiaPaCa2 cells subjected to hypoxia-induced sensitization of cells to 2-deoxy-glucose and D-allose and decreased their viability. Involvement of HIF-1α was probably responsible for the antiproliferative activity because the inhibitor decreased HIF-1α protein accumulation and transcriptional activity[57]. Participation of MAPKs in the development of stromal tissue in cancer has also been proposed[58,59]. In a recent study it has been shown that PSC subjected to hypoxia exhibited an increase in the phosphorylation of JNK, whereas that of p44/42 and p38 was decreased. PSC survival under hypoxia was dependent on JNK activation because incubation of cells with the specific inhibitor SP600125 decreased cell viability[14]. Another member of the MAPK family, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5), is required for the prevention of apoptosis, regulation of hypoxia, tumor angiogenesis, and cell migration[60]. Inhibition of ERK5 diminished proliferation and migration of HepG2 and Huh-7 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells[61]. Implication of ERK5 in other types of cancer, including renal cancer[62], prostate cancer[63], and leukemia[64] has also been reported.

The ERK-5 inhibitor XMD8-92 inhibited pancreatic tumor growth via downregulation of doublecortin-like kinase 1 and several of its downstream targets that are involved in oncogenic pathways, including c-Myc, KRAS, NOTCH1, ZEB1, ZEB2, SNAIL, SLUG, OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, LIN28, VEGFR1, and VEGFR2)[65]. Inhibition of p44/42 and ERK5 synergistically caused loss of Myc protein, which is a key transcriptional factor with a key role in cell growth, differentiation, and tumor development. Inhibition of both MAPKs suppressed PDAC growth[66]. However, additional studies on the participation of ERK5 in the development of PC are currently lacking.

To our knowledge, little is known about the involvement of MAPK signaling in PC under hypoxia because of a lack of published studies. The available evidence indicates that differential inhibition of protein kinases might be used to attenuate the progression of the disease, but it is not conclusive. Therefore, additional research should be conducted in to unravel how this important signaling pathway is affected by hypoxia and to elucidate whether the targeting of MAPKs could be used in cancer therapy. The putative involvement of MAPK signaling under hypoxia is summarized in Figure 3.

Apoptosis is a regulated cellular process that occurs both in physiological and pathological conditions. It is designed to control the cell population within a tissue or organ[67]. The pathways involved in apoptosis can undergo defects that might lead to the transformation of damaged cells. This commonly occurs in cancer and has been reported as responsible for development, growth, metastasis, and chemoresistance in different types of tumors[68]. Bcl-2 is a major protein in the apoptosis pathway. It is considered a gene that suppresses the pathway in the sense that overexpression of Bcl-2 blocks or delays the onset of apoptosis in cancer cells[69]; conversely, inhibition of Bcl-2 may lead cell death in some cancers that are resistant to apoptosis, for example breast cancer and PC[70]. Hypoxia has been associated with treatment resistance in various cancers, and apoptosis is among several signaling pathways that are thought to be involved. Many studies conducted in different cellular models of tumors have reported that the antitumor, and hence beneficial, effects of a variety of drugs depend on their ability to activate apoptosis[71]. However, few studies have focused on how the pathways that control apoptosis are modulated by hypoxia.

Cells with constitutive expression of HIF-1α have been shown to be more resistant to apoptosis than those without constitutive expression of the transcription factor, and the lack of expression was associated with increased in vivo tumorigenicity[72]. The expression of a regulator of hypoxia-induced cell death, Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), was downregulated in PC cells and was associated with adaptation of the tissue to hypoxia and tumor resistance. Restoration of BNIP3 expression increased cell sensitivity to death[73]. Decreased expression of thioredoxin 1 has been reported in human PC tissues and was associated with decreased apoptosis and increased cell survival. The induction of thioredoxin-interacting protein, a tumor suppressor gene, resulted in increased apoptosis of Panc-1 cells even in cells with activation of HIF-1α[74].

In a mouse pancreas endocrine tumor model, it was shown that increased invasion into surrounding exocrine tissue was associated with decreased the expression of caspase-3, and occurred in areas were high levels of HIF-1α were noted[75]. In a related study, cleaved caspase-3 staining was increased in viable tumor tissue of hypoxic models. That was considered as indicating a remodeling process of the growing tissue by a counterbalanced cell loss by apoptosis in response to rapid cell proliferation[76]. Another study showed that MiaPaca2 cells exhibited increased levels of caspase-3 when cells were transfected with HIF-1α siRNA. That resulted in a decrease of cell proliferation and in an increase of chemosensitivity[77]. Overexpression of HIF evoked the expression of hypoxia-induced gene domain family-1a (Higd-1a), a mitochondrial inner membrane protein. The gene expression was believed to promote cell survival under hypoxia, because apoptosis was decreased. The antiapoptotic effect of the genes resulted from the inhibition of cytochrome C release and from the reduction of caspase activity[78]. Another study showed that hypoxia and serum-free media, which were used to mimic tumor hypoxic-ischemic microenvironment, reduced apoptosis and stimulated proliferation of MiaPaCa2 cells[79].

With respect to the tumor microenvironment, it is well accepted that it contributes to resistance to cancer therapy and to the evolution of the disease by regulation of apoptosis[80]. Hypoxia has been shown to regulate the viability of PSC through p21-activated kinase 1. The inhibition of this kinase decreased the activation, inhibited proliferation, and increased apoptosis of human PSC[12]. TH-302, a hypoxia-activated prodrug, was assayed in MiaPaCa2 and PANC-1 cell lines, and in BxPC-3 PDAC xenograft models in mice. The compound helped to reduce stromal density and intratumoral hypoxia, and hence, increased the effectiveness of anticancer drugs[81]. The expression of fibulin-5 (Fbln5) is abundant in the stroma of PDAC[82]. This matricellular protein supports PDAC progression by blocking fibronectin-integrin interaction. Compared with normal pancreatic tissue, Fbln5 content was increased in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and 3T3 fibroblasts subjected to hypoxia. This involved transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)- and PI3K-dependent mechanisms, because inhibition blocked hypoxia-induced Fbln5 expression[83]. The balancing of apoptosis pathways could be a maneuver of PC cells to support the growth of tumor tissue[84]. Moreover, the modulation of HIF expression might be a valuable tool to control tumor cell proliferation under hypoxia[85].

Autophagy is a metabolic pathway that is used by the cell for degradation of cytoplasmic proteins, macromolecules, and organelles in the lysosomes. It serves as a mechanism for protection of the cell and represents a major survival pathway that is activated in the presence of environmental and cellular stress[86]. However, is relationship to cancer development is contradictory. Both cell survival and cell death have been associated with autophagy because defects or partial reduction in autophagy transmit oncogenic stimulus and have been associated with cancer cell survival[70]. Autophagy is also activated under hypoxia and has been reported as potential contributor to the resistance of various types of cancer to therapy[71].

Inhibition of the pAkt/mTORC1 pathway, one of the critical regulators of autophagy, was observed in PC cells incubated under hypoxia, was found to promote autophagy, and was associated with enhanced cell survival[87]. Autophagy induction in response to hypoxia was detected in the PANC-1, BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 pancreatic cell lines, in which inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase induced cytotoxicity and enhanced apoptosis. This suggested the involvement of this pathway in cell survival under hypoxia[88]. Serum-free media and hypoxic conditions protected MiaPaCa2 cells against death by stimulating autophagy. In that study, the ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I expression was increased, and treatment with the inhibitor of autophagy 3-MA decreased cell viability[79]. Autophagy was inhibited by chloroquine in MiaPaCa2 and S2VP10 cells that had been subjected to hypoxia, suggesting that the pathway was responsible for tumor cell survival[89]. Autophagy was also involved in the survival of PDAC cells in spite of the deprivation of nutrients and O2 that derived from the hypoxic tumor microenvironment[90]. In the aforementioned study, LC3 was converted to the active LC3-II form, formation of autophagic and acid vesicles was detected, and PC cell survival and migration increased. Similarly, intermittent hypoxia increased the levels of HIF-1α. Enhanced autophagy was associated with increases in the levels of LC3-II and Beclin. As a consequence, hypoxia-induced stem-like properties of non-stem PC cells, which influenced tumor development and growth[91]. Analysis of the expression of LC3 in different PC tissue samples revealed strong LC3 expression in the peripheral areas, which was related to poor outcome. It was concluded that activation of autophagy was associated with the responses of cells to factors in the cancer microenvironment, including hypoxia[92].

Changes in metabolism related to mitochondrial and bioenergetics adaptations also occur in response to hypoxia. It has been demonstrated that tumor cells survive and proliferate under hypoxic and glucose-deprived conditions that develop in PCs that are caused by a lack of vasculature that leads to a low blood supply to the growing tissue and to changes in energy metabolism[49]. In the same study 63 genes were identified, whose expression was increased under conditions that mimicked hypoxia. Thus, the expression of certain genes may determine the survival of cancer cells when the blood supply of O2 is compromised[49]. Mitochondria are the major organelles responsible for supplying energy to the cell in the presence of O2[93]. It has been suggested that mitochondria undergo changes in dynamics and distribution that are an adaptive response for survival and metastasis[94]. Along this line, PDAC cell lines are able to grow even when O2 tension is as low as 0.1%. Under such conditions, the cells maintain the mitochondrial parameters and oxidative metabolism needed for the synthesis of metabolites that maintain proliferation[8].

Glycolysis is of major relevance to tumor survival and proliferation because is the main provider of energetic substrates[95]. MUC1 is a large type I transmembrane protein that is overexpressed in several carcinomas including PDAC. It regulates, through interaction with HIF-1α, the expression of genes involved in glucose metabolism and enhances glycolytic activity[96]. Hypoxia has been shown to induce adaptive metabolic responses, such as a high glycolytic rate and activation of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, which favor hypoxic and normoxic cancer cell survival[97]. Hypoxic glycolysis, with increases in glucose uptake and lactate production, was found to be governed by ERK2 in PDAC cells and was associated with malignant progression[54]. Phosphoglycerate kinase 1, an enzyme that is involved in the generation of ATP in glycolysis, is involved in the energy supply in PDAC cells via Nuclear Factor of Activated T Cells 5[98]. Activation of glycolysis was shown in another study carried out using PDAC cells subjected to hypoxia. The authors showed that carbonic anhydrase 9 (CA9), an enzyme that is involved in the regulation of cellular pH, was upregulated. It functions as a part of the cellular response to hypoxia to promote cell survival. The inhibition of CA9 reduced the cellular pH, decreased glycolysis, and increased cellular sensitivity to gemcitabine[99]. The use of inhibitors of CA9 was also suggested by Logsdon et al[100], who showed that inhibition of APE1/Ref-1 decreased HIF1α-mediated induction of CA9 and might reduce PDAC cells viability.

The expression of the enzymes 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3 and -4 (PFKFB-3 and PFKFB-4) was increased in different cancer cell lines, including PC, in response to HIF[101]. It is known that those enzymes play a major role in the regulation of glycolysis in cancer cells to support proliferation and survival. Correlation with the enhanced expression of VEGF and glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1) was observed[101]. The M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase (PKM2), a molecule involved in glycolysis, was shown to participate in the metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells and regulated cell cycle progression. Impairment of PKM2 expression decreased cell proliferation and augmented apoptosis and, hence, impaired tumor growth[102]. Another study showed that the activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 was increased in cells subjected to hypoxia and was associated with the induction of colony and spheroid formation[103].

Glucose enters the cell via glucose transporters (GLUTs), of which various classes exist[104]. Targeting GLUTs might be a valuable tool to help anticancer drugs to exert their effects[105]. Increased expression of Glut-1 in cancer cells can maintain the energy supply needed for development and growth[106]. Expression of the genes Glut-1 and aldolase A, which are associated with the regulation of anaerobic metabolism, was found to be increased in cells with constitutive expression of HIF-1α compared with cells without it. It was assumed that expression of HIF-1α was associated with increased survival and proliferation of PC cells, and that cells undergo activation of anaerobic metabolism under conditions of hypoxia and glucose deprivation[72].

Adaptation responses to glucose deprivation and hypoxia are also necessary for the survival of cells in the tumor microenvironment[107]. A number of genes, including Glut-1, Glut-3, and Hexokinase-2, were expressed at high levels in human PC tissue specimens where hypoxic conditions were detected[108]. Guillaumond et al[97] reported that hypoxic PDAC tissue was comprised of abundant epithelial cells harboring epithelial-mesenchymal transition features and expressing glycolytic markers. Hypoxia led to a change in the glycolytic metabolism of PC cells from oxidative phosphorylation to lactate production. As a consequence, the growth of normoxic cancer cells was favored[109]. Interestingly, PDAC cells might use PSC-derived alanine to increase their biochemical flexibility in order to adapt to the austere conditions resulting from hypoxia[110]. Finally, Munc18-1-interacting protein 3 (Mint3) was found to promote ATP production via glycolysis by activating HIF-1α in cancer fibroblasts[58].

Specific conditions and factors within tumor masses, for example hypoxia, nutrient starvation, low pH, and increased levels of free radicals, induce a situation that has been termed "endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress". It is also known as unfolded protein response[111]. In tumors, this response is found in malignant cells and other cell types present in the stroma[112]. In general, ER stress works in favor of cell survival and adaptation to hostile environmental conditions. Nevertheless, the ER stress can also induce cell death if it is unresolved. It can also be connected to inflammation and immune suppression within tumors[113]. For information about the branches operating ER stress see Chern and Tai[114].

As mentioned above, glucose deprivation and hypoxia often occur in solid tumor cells, including PC cells. A study showed that with glucose deprivation, ER stress was activated in cancer cells and upregulated glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), which protects cells from death. Inhibition of ER stress by pancastatin A (PST-A) and B (PST-B), which are glabretal triterpenoid moieties, suppressed the accumulation of GRP78, and exhibited selective cytotoxicity in Panc-1 cells[115]. Hypoxia and ER stress contributed to the overexpression of endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 alpha (ERO1L) in PDAC. ERO1L is an ER luminal glycoprotein that participates in the formation of disulfide bonds in secreted and membrane proteins. This oxidoreductase has been associated with the proliferation of PDAC cells in vitro[116]. To our knowledge, little is known about how ER stress evolves under hypoxia. Further studies need to be carried out in order to better understand how this dual-sided pathway determines cell fate under hypoxia.

PDAC is characterized by a significant inflammatory response[103]. During malignant progression, cancer cells acquire various features that include increased secretion of VEGF and interleukin 6 (IL-6), to which inflammation contributes to a certain extent and confers chemoresistance[50]. Hypoxia induces the accumulation of metabolites that can enter signaling cascades and contribute to the inflammatory response[117]. The expression of IL-6 was enhanced by hypoxia and proteins involved in PC development like Kras, mesothelin or ZIP4. The cytokine contributed to the generation of a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment and was probably involved in angiogenesis[118]. The expression of IL-6 was also reported as responsible for the aggressiveness of PC cells under hypoxia[119]. PC cell lines expressed higher levels of IL-6 than normal human pancreatic tissue. Moreover, exogenous application of IL-6 in Panc-1, MIA PaCa-2, and BxPC-3 cells increased the secretion of multiple Th2-type cytokines. In addition, IL-6 activated ERK2 signaling pathways[120]. Under hypoxia, involvement of downstream elements of the pathways regulated by VEGF and tumor necrosis factor has been suggested[121].

Human IL-37 possesses anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. It also suppresses tumor growth and progression[122]. A study by Zhao et al[123] showed that HIF-1α attenuated IL-37 transcription. A decrease in the expression of IL-37 was observed in PDAC this was associated with increased histological grade, tumor size, metastasis, and vessel invasion. On the other hand, IL-37 suppressed the expression of HIF-1α through the inhibition of Stat3. Stat3 exhibits a range of oncogenic functions that include suppression of antitumor immune responses and promotion of inflammation. Another found showed that PC cell death was induced by blockade of the expression of Stat-3-related genes[124]. It has been suggested that IL-1β was involved in cell proliferation after Myc-induced cell cycle entry. Following Myc activation, cells rapidly exhibited expression and release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, which could be the reason why pleiotropic Myc oncoproteins contributed to the expansion of the vascular compartment during tumor progression[124].

In PDAC the abundant stroma participates in the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells through the activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts and the secretion of TGF-β[125]. It has been proposed that PSC and myofibroblasts subjected to hypoxia contribute to the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and B cells in PDA caused by the release of cytokines[26]. Recruitment of macrophages in PDAC was found to induce the activation of PSC that was associated with a certain degree of inflammation in the tumor region. The process was dependent on HIF-1α[27]. In a study by Maruggi et al[126], it was shown that hypoxic cancer cells secreted the inflammatory chemokines IL-1β and IL-8. Moreover, analysis of the tumor stroma revealed enrichment of myeloid dendritic cells 1 and 2, which secreted proangiogenic cytokines. Another study showed that IL-8 was significantly overexpressed in regions surrounding necrotic areas of PC tissue in which the cells were exposed to hypoxia and an acidic pH. IL-8 was reported to participate in the growth and metastasis of variants derived from COLO 357 human PC cells[127]. Additionally, IL-8 increased tumorigenesis by promoting angiogenesis and metastasis via VEGF and neuropilin expression. IL-8 also stimulated ERK1/2 signaling in the human PC cell line BxPC-3[128]. It may be possible that controlling the inflammatory response and the release of cytokines by cells within the tumor mass would facilitate treatment and restrain tumor growth[129].

Extracellular vesicles, also known as exosomes, consist of diverse types of membrane vesicles of endosomal and plasma membrane origin that are released by the cells into the extracellular milieu[130]. They are considered as an important mode of cell-to-cell communication because they function as vehicles to transfer membrane and cytosolic proteins, lipids, and RNA between cells[131]. The hypoxic microenvironment promotes tumor cells to release exosomes, which is an activity of solid tumors that allows invasion and metastasis[132]. As in other types of cancer, exosomes have a key role pancreatic tumor pathobiology by facilitating intercellular communication. Exosome, are considered as important mediators of the crosstalk between tumor cells and the microenvironment[133].

Hypoxia was found to stimulate the release of exosomes in MiaPaCa2 and AsPC1 cells and to promote the survival of cells subjected to hypoxia. HIF-1α was involved in exosome release[134]. Another study showed that exosomes derived from PC cells subjected to hypoxia-activated macrophages, a process that was dependent on HIF-1α or HIF-2α. Following release, the exosomes facilitated the migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of PC cells, thereby worsening the prognosis[133]. Regarding the stroma, feedback loops are established between stromal elements and tumor cells in the cancerous tissue. Along this line, PSC are responsible for direct nutrient transfer via vesicles[135]. As with other aspects that have been reviewed above, modulation of exosome signaling under hypoxia deserves further study.

Micro (mi)RNAs are noncoding RNAs comprising of a single-stranded chain of 18 to 22 nucleotides, and they play major roles in the regulation of gene expression. Extracellular miRNAs function as chemical messengers to mediate cell-to-cell communication[136]. Synthesized miRNAs can be released from the cell into the extracellular space by (1) selective incorporation in the exosomes, (2) being coupled with Ago2 protein, and (3) by release attached to high-density lipoproteins. Once in the extracellular medium miRNAs will reach other cells to alter their functions[133,137].

Hypoxia was found to decrease the expression of miR-519 in Panc-1 and SW1990 cells[138], and was regarded as a survival mechanism because transfection with miR-519 mimics inhibited cell growth and invasiveness and induced apoptosis. Similarly, HIF-1α induced the downregulation of miR-548an in PC cells during hypoxia. The vimentin content was inversely correlated with miR-548an expression and was associated with facilitation of pancreatic tumorigenesis[139]. miR-454 was found to be present in low levels in PDAC and it was associated with cell growth because overexpression of the miRNA led to slower cell growth[140]. The expression of other miRNAs has been associated with increased cell proliferation and cancer malignancy[141]. miR-210, which is induced by HIF-1α, was reported to have many targets within cells that can regulate the cell cycle, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, angioge

The long noncoding (lnc)RNA UCA1 released from hypoxic PC cells and was shown to promote angiogenesis and tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo by regulation of miR-96-5p[132]. The synthesis and release of circ_0000977 was induced by hypoxia and conferred resistance to natural killer (NK) cells by Panc-1 cells. Inhibition of miR-153-mediated repression of HIF-1α and ADAM10 allowed the immune escape of the cancer cells[146].

Another hypoxia-induced microRNA, miR-646, blocked the expression of migration and invasion inhibitory protein (MIIP), which has been identified as an inhibitor of tumor development. MIIP acted to suppress the activity of histone deacetylase 6 and promote the degradation of HIF-1α, therefore impairing HIF-1α accumulation[147]. Inhibition of MIIP by miR-646 led to increased proliferation and invasion of PC cells. miR125a, the content of which was regulated by HIF-1α, inhibited mitochondrial fission and contributed to cellular survival in PDAC by preventing apoptosis[148].

The existing evidence signals that miRNAs differentially participate in regulating cell fate. Whereas certain types are downregulated in cancer cells, others have increased expression compared with healthy cells[149,150]. The expression of miRNAs is regulated by HIF-1α when hypoxic conditions are established, and that confers the tumor cells with adaptations that allow cancer growth. A summary of the roles of miRNAs in PC under hypoxia is provided in Table 1. Fewer studies have investigated miRNAs in the pancreatic stroma. Along this line, Bynigeri et al[151] reported that miRNAs were involved in the inflammatory and profibrogenic functions of PSC. Within the stroma, the interaction of PSC and tumor cells that include signaling through miRNAs can promote tumor progression, metastasis, immune evasion, and drug resistance, which impact the evolution and prognosis of PC[152].

| MicroRNA | Oncogenic activity | Function | Ref. |

| miR-519 | Anti-tumor | Inhibits cell growth and invasiveness | [138] |

| miR-58an | Anti-tumor | Reduces tumorigenesis | [139] |

| miR-454 | Anti-tumor | Decreases cell proliferation | [140] |

| miR-210 | Pro-tumor | Regulates cell cycle and promotes angiogenesis | [142] |

| miR-191 | Pro-tumor | Promotes tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis | [143] |

| miR-212 | Pro-tumor | Promotes tumor growth, vessel invasion, and metastasis | [144] |

| miR-21 | Pro-tumor | Induces cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis | [119,145] |

| miR-210 | Pro-tumor | Increases migration, invasion, and angiogenesis | [119] |

| miR-646 | Pro-tumor | Promotes proliferation and invasion | [147] |

| miR-125a | Pro-tumor | Increases tumor cell viability | [148] |

| miR-96-5p | Anti-tumor | Inhibits angiogenesis | [132] |

| miR-153 | Anti-tumor | Avoids immune escape of tumor cells from natural killer cells | [146] |

As noted earlier in this review, cells growing within the tumor mass make key adaptions and changes in intracellular pathways that might convey resistance to death and to treatment. In fact, the most frequent treatment of PDAC is radical surgery and chemotherapy, and they are the only treatments that seems to work in a only a few patients. Despite treatment, PDAC remains a highly lethal disease. In addition to surgery, various combinations of drugs of different types have been evaluated as chemotherapy and remains as the standard adjuvant therapy[153]. For example, the combination of FOLFIRINOX and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine as found to improve the survival of patients with metastatic disease[154] and to improve surgical and clinicopathologic outcomes following pancreatic resection[155].

It must be noted that failure of chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy have all been attributed to the PDAC microenvironment[156]. Dysregulation of the tumor microenvironment promotes an intense fibrosis and immune suppression that plays a key role in drug resistance[157]. Therefore, targeting the extracellular tumor microenvironment via inhibition of signaling pathways, alteration of DNA repair pathways, immunotherapy and/or modulation of cell metabolism, might serve as novel tools for PDAC treatment. Treatments under study include vaccines, oncolytic viruses, MEK inhibitors, cytokine inhibitors, and targeting hypoxia[125]. Recently, intense efforts have been carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of therapies aiming to increase tumor immunogenicity and promote the recruitment and activation of effector T cells[125]. Along this line, it has been suggested that challenging the immunosuppression occurring within pancreatic immune infiltrate might diminish tumor aggressiveness[154]. Because hypoxia contributes to aggressive tumor behavior, mainly involving tumor progression, malignancy, and promoting resistance to conventional and targeted therapeutic agents[158], finding drugs that are effective in the modulation of cell proliferation under hypoxia is a major challenge. HIF has been seen as a potential therapeutic target in the pathobiology of PDAC. Interestingly, HIF might exert its oncogenic influence through the modulation of the stroma rather than the modulation of cancer cells[159]. Cyclopamine, a hedgehog inhibitor plus paclitaxel in a polymeric micelle formulation, exhibited effects on the stroma by increasing microvessel density, alleviating hypoxia, and reducing matrix stiffness while maintaining the tumor-restraining function of extracellular matrix. As a result, tumor growth was suppressed and animal survival was prolonged[160]. Targeting HIF by siRNAs delivered to cancer cells might be an effective cancer treatment. Indeed, recombinant adeno-associated virus has been employed to deliver siRNA targeting HIF-1α into MiaPaCa2 human PC cells subjected to hypoxia. As a consequence, cell proliferation and migration decreased and apoptosis was induced [85]. siRNA targeting of HIF-1α in MiaPaCa2 cells subjected to hypoxia-induced apoptosis through both NF-kB-independent and -dependent mechanisms[161].

Additionally, hypoxia-activated prodrugs designed to overcome the resistance of cancer cells have shown clinical efficacy[162]. TH-302 is an investigational hypoxia-activated prodrug. Its combination with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel was effective in PDAC xenograft models in mice[81]. Moreover, TH-302 significantly decreased in vivo tumor growth, increased survival in a MiaPaCa cancer model and improved survival in Hs766t tumors[162]. Recently, we showed that PSC adapted to pro-oxidant conditions under hypoxia, and that the adaptations may have been responsible for increased cell viability and proliferation[14]. Interestingly, melatonin modulated the antioxidant responses and signaling by inflammatory regulators. Therefore, this indoleamine is emerging as another potential treatment of PDAC[163].

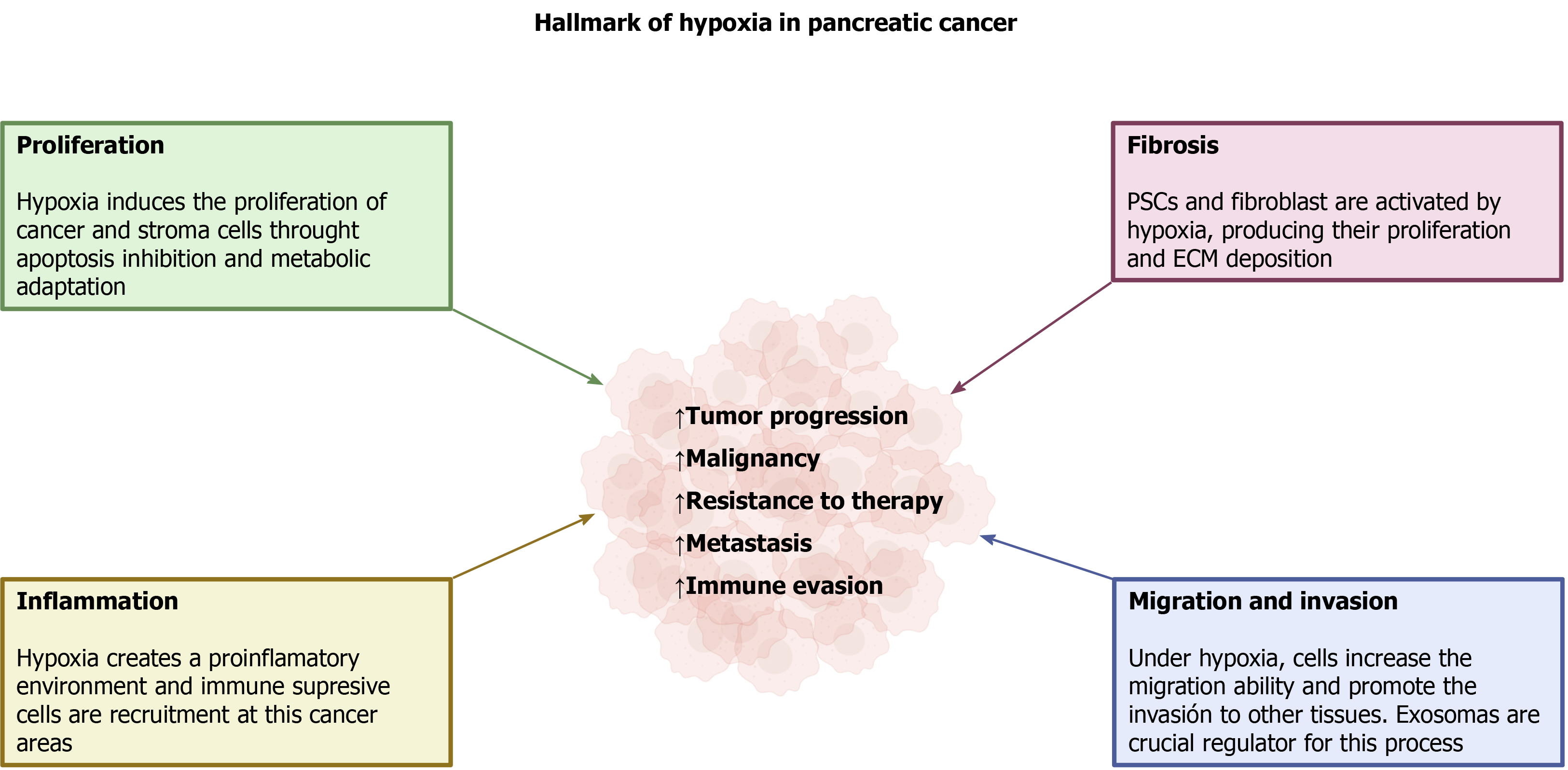

Hypoxia is a common condition that is created in solid tumors and it results from rapid, uncontrolled growth of the tissue that is accompanied by insufficient development of blood microcirculation. Along with tumor cell proliferation, a fibrotic reaction is established that involves the parallel growth of several types of cells different from tumor cells, and the deposition of extracellular components, which comprises a stromal component. As a consequence of the low O2 availability that develops, all the cells included in the mass adapt in order to survive. HIF is the major regulator of cell responses to hypoxia. Activation of different intracellular pathways and changes in cellular energy metabolism take place, and are all modulated by hypoxia. These conditions are responsible for tumor progression, malignancy, and resistance to therapy, which are major features of PC. Additionally, capabilities of invasion of neighbor tissues, organs, and metastasis are acquired, all of which are critical determinants of the extreme malignancy of PC. A summary of the major adaptations of pancreatic tumor to hypoxia is shown in Figure 4.

| 1. | International Agency for Research on Cancer - WHO. Global Cancer Observatory. 2021. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/. |

| 2. | Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913-2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5379] [Cited by in RCA: 5360] [Article Influence: 446.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferlay J, Partensky C, Bray F. More deaths from pancreatic cancer than breast cancer in the EU by 2017. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1158-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4846-4861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1338] [Cited by in RCA: 1346] [Article Influence: 168.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (49)] |

| 5. | Yamasaki A, Yanai K, Onishi H. Hypoxia and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2020;484:9-15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Hirai F, Motoori S, Kakinuma S, Tomita K, Indo HP, Kato H, Yamaguchi T, Yen HC, St Clair DK, Nagano T, Ozawa T, Saisho H, Majima HJ. Mitochondrial signal lacking manganese superoxide dismutase failed to prevent cell death by reoxygenation following hypoxia in a human pancreatic cancer cell line, KP4. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:523-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McKeown SR. Defining normoxia, physoxia and hypoxia in tumours-implications for treatment response. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 464] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hollinshead KER, Parker SJ, Eapen VV, Encarnacion-Rosado J, Sohn A, Oncu T, Cammer M, Mancias JD, Kimmelman AC. Respiratory Supercomplexes Promote Mitochondrial Efficiency and Growth in Severely Hypoxic Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108231. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Valkenburg KC, de Groot AE, Pienta KJ. Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:366-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 825] [Article Influence: 117.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Bu L, Baba H, Yoshida N, Miyake K, Yasuda T, Uchihara T, Tan P, Ishimoto T. Biological heterogeneity and versatility of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2019;38:4887-4901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xu Z, Pothula SP, Wilson JS, Apte MV. Pancreatic cancer and its stroma: a conspiracy theory. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11216-11229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yeo D, Phillips P, Baldwin GS, He H, Nikfarjam M. Inhibition of group 1 p21-activated kinases suppresses pancreatic stellate cell activation and increases survival of mice with pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2101-2111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ostapoff KT, Awasthi N, Cenik BK, Hinz S, Dredge K, Schwarz RE, Brekken RA. PG545, an angiogenesis and heparanase inhibitor, reduces primary tumor growth and metastasis in experimental pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1190-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Estaras M, Martinez-Morcillo S, García A, Martinez R, Estevez M, Perez-Lopez M, Miguez MP, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Mateos JM, Vara D, Blanco G, Lopez D, Roncero V, Salido GM, Gonzalez A. Pancreatic stellate cells exhibit adaptation to oxidative stress evoked by hypoxia. Biol Cell. 2020;112:280-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Semenza GL. HIF-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:167-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouysségur J. HIF at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1055-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Trayhurn P. Hypoxia and adipose tissue function and dysfunction in obesity. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choi JH, Park MJ, Kim KW, Choi YH, Park SH, An WG, Yang US, Cheong J. Molecular mechanism of hypoxia-mediated hepatic gluconeogenesis by transcriptional regulation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2795-2801. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Ratcliffe PJ. HIF-1 and HIF-2: working alone or together in hypoxia? J Clin Invest. 2007;117:862-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guan Y, Reddy KR, Zhu Q, Li Y, Lee K, Weerasinghe P, Prchal J, Semenza GL, Jing N. G-rich oligonucleotides inhibit HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha and block tumor growth. Mol Ther. 2010;18:188-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yuen A, Díaz B. The impact of hypoxia in pancreatic cancer invasion and metastasis. Hypoxia (Auckl). 2014;2:91-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xiao Y, Qin T, Sun L, Qian W, Li J, Duan W, Lei J, Wang Z, Ma J, Li X, Ma Q, Xu Q. Resveratrol Ameliorates the Malignant Progression of Pancreatic Cancer by Inhibiting Hypoxia-induced Pancreatic Stellate Cell Activation. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:963689720929987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tang LR, Wu JX, Cai SL, Huang YX, Zhang XQ, Fu WK, Zhuang QY, Li JL. Prolyl hydroxylase domain 3 influences the radiotherapy efficacy of pancreatic cancer cells by targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:8507-8515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Su Y, Loos M, Giese N, Hines OJ, Diebold I, Görlach A, Metzen E, Pastorekova S, Friess H, Büchler P. PHD3 regulates differentiation, tumour growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1571-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schwartz DL, Bankson JA, Lemos R Jr, Lai SY, Thittai AK, He Y, Hostetter G, Demeure MJ, Von Hoff DD, Powis G. Radiosensitization and stromal imaging response correlates for the HIF-1 inhibitor PX-478 given with or without chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2057-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Daniel SK, Sullivan KM, Labadie KP, Pillarisetty VG. Hypoxia as a barrier to immunotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Med. 2019;8:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li N, Li Y, Li Z, Huang C, Yang Y, Lang M, Cao J, Jiang W, Xu Y, Dong J, Ren H. Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) Recruits Macrophage to Activate Pancreatic Stellate Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Katagiri T, Kobayashi M, Yoshimura M, Morinibu A, Itasaka S, Hiraoka M, Harada H. HIF-1 maintains a functional relationship between pancreatic cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts by upregulating expression and secretion of Sonic hedgehog. Oncotarget. 2018;9:10525-10535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kitajima Y, Ide T, Ohtsuka T, Miyazaki K. Induction of hepatocyte growth factor activator gene expression under hypoxia activates the hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met system via hypoxia inducible factor-1 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1341-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gray MJ, Zhang J, Ellis LM, Semenza GL, Evans DB, Watowich SS, Gallick GE. HIF-1alpha, STAT3, CBP/p300 and Ref-1/APE are components of a transcriptional complex that regulates Src-dependent hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF in pancreatic and prostate carcinomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:3110-3120. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Yang Y, Karakhanova S, Hartwig W, D'Haese JG, Philippov PP, Werner J, Bazhin AV. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial ROS in Cancer: Novel Targets for Anticancer Therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231:2570-2581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dan Dunn J, Alvarez LA, Zhang X, Soldati T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2015;6:472-485. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Sinha K, Das J, Pal PB, Sil PC. Oxidative stress: the mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87:1157-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1343] [Cited by in RCA: 1319] [Article Influence: 101.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Leung PS. The physiology of a local renin-angiotensin system in the pancreas. J Physiol. 2007;580:31-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Yamamizu K, Hamada Y, Narita M. κ Opioid receptor ligands regulate angiogenesis in development and in tumours. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:268-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Küper A, Baumann J, Göpelt K, Baumann M, Sänger C, Metzen E, Kranz P, Brockmeier U. Overcoming hypoxia-induced resistance of pancreatic and lung tumor cells by disrupting the PERK-NRF2-HIF-axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Silvestris N, Danza K, Longo V, Brunetti O, Fucci L, Argentiero A, Calabrese A, Cataldo I, Tamma R, Ribatti D, Tommasi S. Angiogenesis in adenosquamous cancer of pancreas. Oncotarget. 2017;8:95773-95779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Narayanan D, Ma S, Özcelik D. Targeting the Redox Landscape in Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fishel ML, Jiang Y, Rajeshkumar NV, Scandura G, Sinn AL, He Y, Shen C, Jones DR, Pollok KE, Ivan M, Maitra A, Kelley MR. Impact of APE1/Ref-1 redox inhibition on pancreatic tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1698-1708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yagishita Y, Fukutomi T, Sugawara A, Kawamura H, Takahashi T, Pi J, Uruno A, Yamamoto M. Nrf2 protects pancreatic β-cells from oxidative and nitrosative stress in diabetic model mice. Diabetes. 2014;63:605-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ip SP, Chan YW, Che CT, Leung PS. Effect of chronic hypoxia on glutathione status and membrane integrity in the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2002;2:34-39. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Peng G, Tang Z, Xiang Y, Chen W. Glutathione peroxidase 4 maintains a stemness phenotype, oxidative homeostasis and regulates biological processes in Panc1 cancer stemlike cells. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:1264-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Abdalla MY, Ahmad IM, Rachagani S, Banerjee K, Thompson CM, Maurer HC, Olive KP, Bailey KL, Britigan BE, Kumar S. Enhancing responsiveness of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine treatment under hypoxia by heme oxygenase-1 inhibition. Transl Res. 2019;207:56-69. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 44. | Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Superoxide dismutases: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1583-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1195] [Cited by in RCA: 1482] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Xiao H, Li S, Zhang D, Liu T, Yu M, Wang F. Separate and concurrent use of 2-deoxy-D-glucose and 3-bromopyruvate in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Erin N, Grahovac J, Brozovic A, Efferth T. Tumor microenvironment and epithelial mesenchymal transition as targets to overcome tumor multidrug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2020;53:100715. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Cargnello M, Roux PP. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:50-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1732] [Cited by in RCA: 2512] [Article Influence: 167.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Tateishi K, Funakoshi A, Misumi Y, Matsuoka Y. Jun and MAP kinases are activated by cholecystokinin in the pancreatic carcinoma cell line KP-1N. Pancreas. 1998;16:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cui H, Darmanin S, Natsuisaka M, Kondo T, Asaka M, Shindoh M, Higashino F, Hamuro J, Okada F, Kobayashi M, Nakagawa K, Koide H. Enhanced expression of asparagine synthetase under glucose-deprived conditions protects pancreatic cancer cells from apoptosis induced by glucose deprivation and cisplatin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3345-3355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Niess H, Camaj P, Mair R, Renner A, Zhao Y, Jäckel C, Nelson PJ, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. Overexpression of IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 (IFIT3) in pancreatic cancer: cellular "pseudoinflammation" contributing to an aggressive phenotype. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3306-3318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Barcelos RC, Pelizzaro-Rocha KJ, Pastre JC, Dias MP, Ferreira-Halder CV, Pilli RA. A new goniothalamin N-acylated aza-derivative strongly downregulates mediators of signaling transduction associated with pancreatic cancer aggressiveness. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;87:745-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | He X, Wang J, Wei W, Shi M, Xin B, Zhang T, Shen X. Hypoxia regulates ABCG2 activity through the activivation of ERK1/2/HIF-1α and contributes to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17:188-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Stoeltzing O, Liu W, Reinmuth N, Fan F, Parikh AA, Bucana CD, Evans DB, Semenza GL, Ellis LM. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, vascular endothelial growth factor, and angiogenesis by an insulin-like growth factor-I receptor autocrine loop in human pancreatic cancer. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1001-1011. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 54. | Jia Y, Li HY, Wang J, Wang Y, Zhang P, Ma N, Mo SJ. Phosphorylation of 14-3-3ζ links YAP transcriptional activation to hypoxic glycolysis for tumorigenesis. Oncogenesis. 2019;8:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Hashimoto K, Farrow BJ, Evers BM. Activation and role of MAP kinases in 15d-PGJ2-induced apoptosis in the human pancreatic cancer cell line MIA PaCa-2. Pancreas. 2004;28:153-159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 56. | Kwon SJ, Song JJ, Lee YJ. Signal pathway of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha phosphorylation and its interaction with von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein during ischemia in MiaPaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7607-7613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Malm SW, Hanke NT, Gill A, Carbajal L, Baker AF. The anti-tumor efficacy of 2-deoxyglucose and D-allose are enhanced with p38 inhibition in pancreatic and ovarian cell lines. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Nakaoka HJ, Tanei Z, Hara T, Weng JS, Kanamori A, Hayashi T, Sato H, Orimo A, Otsuji K, Tada K, Morikawa T, Sasaki T, Fukayama M, Seiki M, Murakami Y, Sakamoto T. Mint3-mediated L1CAM expression in fibroblasts promotes cancer cell proliferation via integrin α5β1 and tumour growth. Oncogenesis. 2017;6:e334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Navis AC, Bourgonje A, Wesseling P, Wright A, Hendriks W, Verrijp K, van der Laak JA, Heerschap A, Leenders WP. Effects of dual targeting of tumor cells and stroma in human glioblastoma xenografts with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor against c-MET and VEGFR2. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Roberts OL, Holmes K, Müller J, Cross DA, Cross MJ. ERK5 and the regulation of endothelial cell function. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:1254-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Rovida E, Di Maira G, Tusa I, Cannito S, Paternostro C, Navari N, Vivoli E, Deng X, Gray NS, Esparís-Ogando A, David E, Pandiella A, Dello Sbarba P, Parola M, Marra F. The mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5 regulates the development and growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2015;64:1454-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Serrano-Oviedo L, Giménez-Bachs JM, Nam-Cha SY, Cimas FJ, García-Cano J, Sánchez-Prieto R, Salinas-Sánchez AS. Implication of VHL, ERK5, and HIF-1alpha in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Molecular basis. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:114.e154-114.e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Rodríguez-Berriguete G, Fraile B, Martínez-Onsurbe P, Olmedilla G, Paniagua R, Royuela M. MAP Kinases and Prostate Cancer. J Signal Transduct. 2012;2012:169170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Tusa I, Cheloni G, Poteti M, Gozzini A, DeSouza NH, Shan Y, Deng X, Gray NS, Li S, Rovida E, Dello Sbarba P. Targeting the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 5 Pathway to Suppress Human Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;11:929-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sureban SM, May R, Weygant N, Qu D, Chandrakesan P, Bannerman-Menson E, Ali N, Pantazis P, Westphalen CB, Wang TC, Houchen CW. XMD8-92 inhibits pancreatic tumor xenograft growth via a DCLK1-dependent mechanism. Cancer Lett. 2014;351:151-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Vaseva AV, Blake DR, Gilbert TSK, Ng S, Hostetter G, Azam SH, Ozkan-Dagliyan I, Gautam P, Bryant KL, Pearce KH, Herring LE, Han H, Graves LM, Witkiewicz AK, Knudsen ES, Pecot CV, Rashid N, Houghton PJ, Wennerberg K, Cox AD, Der CJ. KRAS Suppression-Induced Degradation of MYC Is Antagonized by a MEK5-ERK5 Compensatory Mechanism. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:807-822.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Modi S, Kir D, Banerjee S, Saluja A. Control of Apoptosis in Treatment and Biology of Pancreatic Cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:279-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1328] [Cited by in RCA: 2008] [Article Influence: 133.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | García-Sáez AJ. The secrets of the Bcl-2 family. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1733-1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Dalby KN, Tekedereli I, Lopez-Berestein G, Ozpolat B. Targeting the prodeath and prosurvival functions of autophagy as novel therapeutic strategies in cancer. Autophagy. 2010;6:322-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Jing X, Yang F, Shao C, Wei K, Xie M, Shen H, Shu Y. Role of hypoxia in cancer therapy by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 1408] [Article Influence: 201.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Akakura N, Kobayashi M, Horiuchi I, Suzuki A, Wang J, Chen J, Niizeki H, Kawamura Ki, Hosokawa M, Asaka M. Constitutive expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha renders pancreatic cancer cells resistant to apoptosis induced by hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6548-6554. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Okami J, Simeone DM, Logsdon CD. Silencing of the hypoxia-inducible cell death protein BNIP3 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5338-5346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Baker AF, Koh MY, Williams RR, James B, Wang H, Tate WR, Gallegos A, Von Hoff DD, Han H, Powis G. Identification of thioredoxin-interacting protein 1 as a hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha-induced gene in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;36:178-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Takeda T, Okuyama H, Nishizawa Y, Tomita S, Inoue M. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α is necessary for invasive phenotype in Vegf-deleted islet cell tumors. Sci Rep. 2012;2:494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Chang Q, Jurisica I, Do T, Hedley DW. Hypoxia predicts aggressive growth and spontaneous metastasis formation from orthotopically grown primary xenografts of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3110-3120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Yang L, Kang WK. The effect of HIF-1alpha siRNA on growth and chemosensitivity of MIA-paca cell line. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | An HJ, Shin H, Jo SG, Kim YJ, Lee JO, Paik SG, Lee H. The survival effect of mitochondrial Higd-1a is associated with suppression of cytochrome C release and prevention of caspase activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:2088-2098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Wu CY, Guo XZ, Li HY. Hypoxia and Serum deprivation protected MiaPaCa-2 cells from KAI1-induced proliferation inhibition through autophagy pathway activation in solid tumors. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4060] [Cited by in RCA: 6077] [Article Influence: 506.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Sun JD, Liu Q, Ahluwalia D, Li W, Meng F, Wang Y, Bhupathi D, Ruprell AS, Hart CP. Efficacy and safety of the hypoxia-activated prodrug TH-302 in combination with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in human tumor xenograft models of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:438-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 82. | Wang M, Topalovski M, Toombs JE, Wright CM, Moore ZR, Boothman DA, Yanagisawa H, Wang H, Witkiewicz A, Castrillon DH, Brekken RA. Fibulin-5 Blocks Microenvironmental ROS in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5058-5069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Topalovski M, Hagopian M, Wang M, Brekken RA. Hypoxia and Transforming Growth Factor β Cooperate to Induce Fibulin-5 Expression in Pancreatic Cancer. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:22244-22252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Enane FO, Saunthararajah Y, Korc M. Differentiation therapy and the mechanisms that terminate cancer cell proliferation without harming normal cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Chen C, Tang P, Yue J, Ren P, Liu X, Zhao X, Yu Z. Effect of siRNA targeting HIF-1alpha combined L-ascorbate on biological behavior of hypoxic MiaPaCa2 cells. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2009;8:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Saha S, Panigrahi DP, Patil S, Bhutia SK. Autophagy in health and disease: A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;104:485-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 397] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 87. | Joshi S, Kumar S, Ponnusamy MP, Batra SK. Hypoxia-induced oxidative stress promotes MUC4 degradation via autophagy to enhance pancreatic cancer cells survival. Oncogene. 2016;35:5882-5892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Owada S, Ito K, Endo H, Shida Y, Okada C, Nezu T, Tatemichi M. An Adaptation System to Avoid Apoptosis via Autophagy Under Hypoxic Conditions in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:4927-4934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Frieboes HB, Huang JS, Yin WC, McNally LR. Chloroquine-mediated cell death in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma through inhibition of autophagy. JOP. 2014;15:189-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Rausch V, Liu L, Apel A, Rettig T, Gladkich J, Labsch S, Kallifatidis G, Kaczorowski A, Groth A, Gross W, Gebhard MM, Schemmer P, Werner J, Salnikov AV, Zentgraf H, Büchler MW, Herr I. Autophagy mediates survival of pancreatic tumour-initiating cells in a hypoxic microenvironment. J Pathol. 2012;227:325-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Zhu H, Wang D, Liu Y, Su Z, Zhang L, Chen F, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Yu M, Zhang Z, Shao G. Role of the Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha induced autophagy in the conversion of non-stem pancreatic cancer cells into CD133+ pancreatic cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Fujii S, Mitsunaga S, Yamazaki M, Hasebe T, Ishii G, Kojima M, Kinoshita T, Ueno T, Esumi H, Ochiai A. Autophagy is activated in pancreatic cancer cells and correlates with poor patient outcome. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1813-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Solaini G, Baracca A, Lenaz G, Sgarbi G. Hypoxia and mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1171-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Yan X, Qu X, Tian R, Xu L, Jin X, Yu S, Zhao Y, Ma J, Liu Y, Sun L, Su J. Hypoxia-induced NAD+ interventions promote tumor survival and metastasis by regulating mitochondrial dynamics. Life Sci. 2020;259:118171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Costanza B, Rademaker G, Tiamiou A, De Tullio P, Leenders J, Blomme A, Bellier J, Bianchi E, Turtoi A, Delvenne P, Bellahcène A, Peulen O, Castronovo V. Transforming growth factor beta-induced, an extracellular matrix interacting protein, enhances glycolysis and promotes pancreatic cancer cell migration. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:1570-1584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |