Published online Jul 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i26.4236

Peer-review started: November 10, 2020

First decision: November 30, 2020

Revised: December 16, 2020

Accepted: March 29, 2021

Article in press: March 29, 2021

Published online: July 14, 2021

Processing time: 243 Days and 14 Hours

Prophylactic drains have been used to remove intraperitoneal collections and detect complications early in open surgery. In the last decades, minimally invasive gastric cancer surgery has been performed worldwide. However, reports on routine prophylactic abdominal drainage after totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy are few.

To evaluate the feasibility performing totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy without prophylactic drains in selected patients.

Data of patients with distal gastric cancer who underwent totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with and without prophylactic drainage at China National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital from February 2018 to August 2019 were reviewed. The outcomes between patients with and without prophylactic drainage were compared.

A total of 457 patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer were identified. Of these, 125 patients who underwent totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy were included. After propensity score matching, data of 42 pairs were extracted. The incidence of concurrent illness was higher in the drain group (42.9% vs 31.0%, P = 0.258). The overall postoperative complication rates were 19.5% and 10.6% in the drain (n = 76) and no-drain groups (n = 49), respectively; there were no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). The difference between the two groups based on the need for percutaneous catheter drainage was also not significant (9.8% vs 6.4%, P = 0.700). However, patients with a larger body mass index (≥ 29 kg/m2) were prone to postoperative complications (P = 0.042). In addition, the number of days from surgery until the first flatus (4.33 ± 1.24 d vs 3.57 ± 1.85 d, P = 0.029) was greater in the drain group.

Omitting prophylactic drainage may reduce surgery time and result in faster recovery. Routine prophylactic drains are not necessary in selected patients. A prophylactic drain may be useful in high-risk patients.

Core Tip: We reviewed the outcomes of 125 consecutive patients with distal gastric cancer who underwent totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with and without prophylactic drainage at China National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital from February 2018 to August 2019. We found that performing totally laparoscopic gastrectomy without prophylactic drains in selected patients is possible. It significantly improved postoperative comfort and did not increase the risk of postoperative complications.

- Citation: Liu H, Jin P, Quan X, Xie YB, Ma FH, Ma S, Li Y, Kang WZ, Tian YT. Feasibility of totally laparoscopic gastrectomy without prophylactic drains in gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(26): 4236-4245

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i26/4236.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i26.4236

In the last decade, gastric cancer has been one of the most frequently occurring malignancies worldwide, with about one million new cases of gastric cancer in 2017. It is the fifth most common malignancy and the third highest malignant tumor, with an estimated 783000 deaths[1]. In China, there were approximately 677000 new gastric cancer cases in 2015. This accounted for half of the new gastric cancer cases worldwide[2].

In 1994, Kitano et al[3] reported the first case of laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) with D2 lymphadenectomy[3]. A recent multi-center clinical study in South Korea also confirmed that the operation was safe and effective[4]. With the development of surgical instruments and technology, early minimally invasive gastric cancer surgery has been widely performed worldwide. Meanwhile, the interim results of a class 01 clinical trial led by China’s Southern Hospital showed that the efficacy of laparoscopic surgery for advanced distal gastric cancer was comparable to that of open surgery[5].

The development of laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery has led to its emergence as a treatment modality for distal gastric cancer. Compared with laparoscopic assisted surgery, totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG) is an intra-cavitary anastomosis, which does not require an auxiliary small incision. The reconstruction of TLDG anastomosis is safer, regardless of tumor location, with a lower incidence of incision problems than LADG. Moreover, it can be performed more effectively in obese patients[6,7].

Prophylactic drains have been used to remove intraperitoneal collections and detect complications early. However, numerous trials have failed to demonstrate a reduction in postoperative complications by routine drainage in gastrointestinal surgery[8]. Several studies performed after open gastrectomy or LADG concluded that the prophylactic use of drains did not significantly improve postoperative outcomes. However, there are few studies on routine prophylactic drainage after TLDG.

In the current retrospective study, we compared the outcomes of patients who underwent TLDG with and without drainage to clarify the value of routine prophylactic drainage in uncomplicated TLDG procedures for distal gastric cancer.

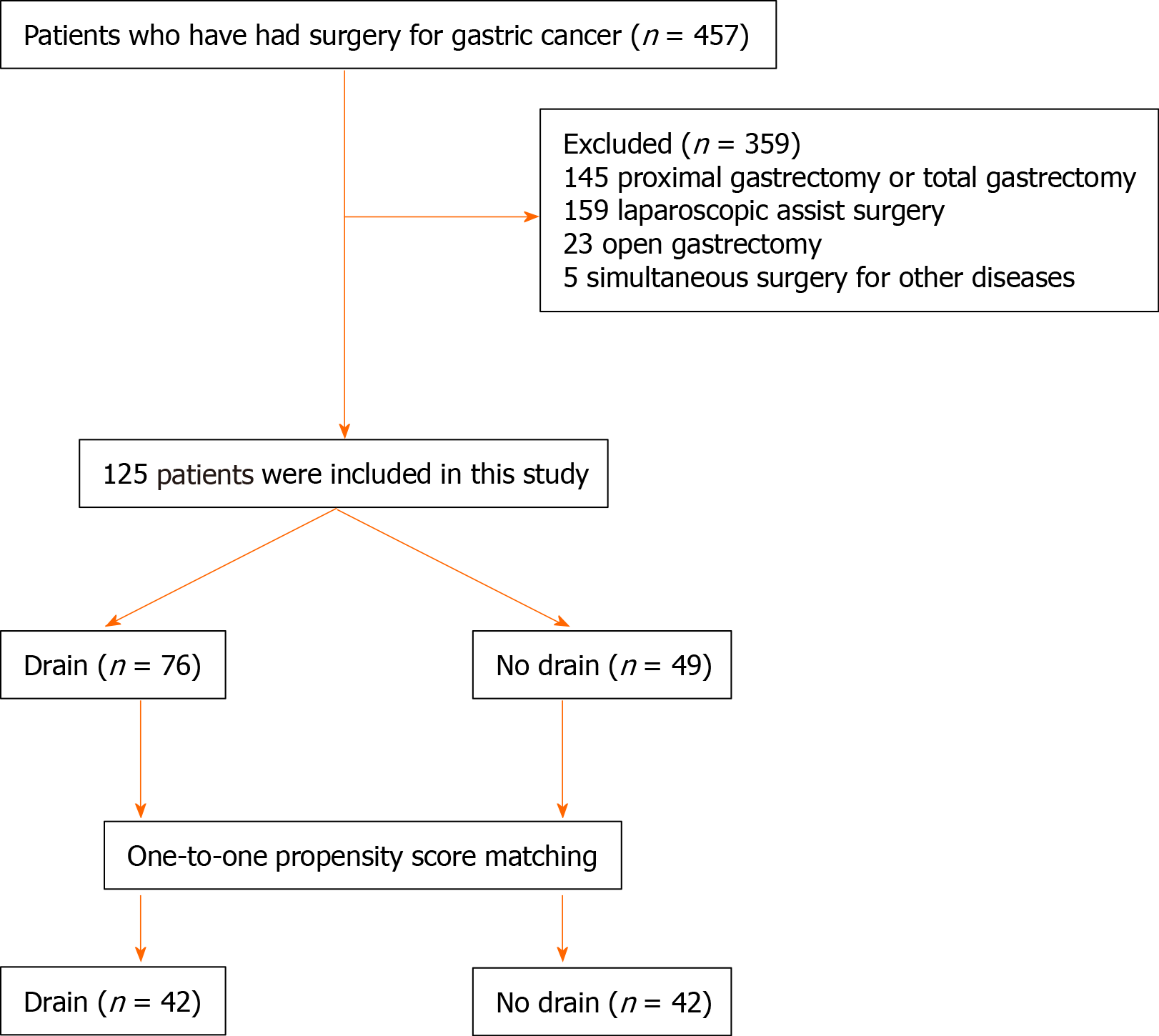

We reviewed the outcomes of 457 consecutive patients with distal gastric cancer who underwent TLDG with and without prophylactic drainage at China National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital from February 2018 to August 2019. Among them, 145 patients who underwent proximal gastrectomy or total gastrectomy, 159 patients who underwent laparoscopic assisted surgery, 23 who underwent open gastrectomy (including four cases converted from laparoscopic surgery), and five who underwent simultaneous surgery for other diseases such as choledocholithiasis (n = 1), ovarian tumor (n = 1), and pancreatic tail (n = 3) were excluded. Finally, a total of 125 patients were included in this study. They were assigned to a drain or no-drain group according to their operation records. The drain group comprised 76 patients who underwent TLDG with routine prophylactic drainage, and the no-drain group comprised 49 patients who underwent TLDG without routine prophylactic drainage (Figure 1).

The extent of gastrectomy and lymph node dissection were determined based on the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[9]. The surgeon was on the left side of the patient to finish laparoscopic ligation and division, and the first assistant was positioned on the opposite side. A cameraman stood between the patient’ s legs. A five-port system (i.e., two 5 mm and three 12 mm ports) was used for each totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Ten-millimeter flexible laparoscopes were used, with CO2 pressure maintained at 13-15 mmHg.

The operator was on the left side of the patient to perform Billroth-I reconstruction using a modified delta-shaped anastomosis[10] or overlap anastomosis[8]. Billroth-II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction was performed on the right side of the patients.

Patients in both groups were administered prophylactic antibiotics 30 min before surgery. The decision of whether to use a prophylactic drain was made by the surgeon. Oral intake of water was initiated on the first day after surgery. A soft diet was initiated after the patient could tolerate liquid meals, and postoperative upper gastrointestinal contrast confirmed the absence of anastomotic leakage.

The clinical, operative, and pathological variables were compared between the two groups based on the information obtained from our prospectively collected surgical database. Early postoperative complications (occurring on postoperative days 0-30) were graded using the Clavien–Dindo classification. Early postoperative complications requiring medical, radiological, or surgical interventions (grade 2 or higher) were regarded as events. The risk for the occurrence of postoperative complications was also assessed.

All values are expressed as the mean ± SD. The χ2 test and Student’s t test were used to compare the categorical and continuous variables, respectively. For categorical data, the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was performed. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistic Package for Social Science. 20.

Multiple factor logistic regression models were used to calculate the propensity score for each patient to balance the following covariates: Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), abdominal operation history, smoking history, drinking history, concurrent illness, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, operation time, estimated blood loss, primary tumor stage, regional lymph node stage, tumor size, and number of retrieved lymph nodes. We imposed a caliper width of 0.1 of the standard deviation of the logistic propensity score.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of patients undergoing TLDG with or without a prophylactic drain. No significant differences were observed in patient sex, age, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, abdominal operation history, smoking history, drinking history, concurrent illness primary tumor stage, or regional lymph node stage between the two groups after propensity score matching (PSM).

| ALL patients | Propensity-matched patients | |||||

| Characteristic | Drain (n = 76) | No drain (n = 49) | P value | Drain (n = 42) | No drain (n = 42) | P value |

| Sex (M/F) | 54/22 | 33/16 | 0.660 | 31/11 | 29/13 | 0.629 |

| Age | 57.58 ± 9.90 | 54.14 ± 12.63 | 0.092 | 57.4 ± 9.9 | 58.1 ± 10.8 | 0.739 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.71 ± 3.76 | 24.64 ± 3.72 | 0.915 | 24.3 ± 3.5 | 24.4 ± 2.7 | 0.879 |

| ASA (1/2/3), n (%) | 0.562 | 0.565 | ||||

| 1 | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 2 | 70 (92.1) | 44 (89.8) | 38 (90.5) | 38 (90.5) | ||

| 3 | 5 (6.6) | 5 (10.2) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (9.5) | ||

| pT stage, n (%) | 0.605 | 0.805 | ||||

| T1 | 39 (52.0) | 24 (49.0) | 20 (47.6) | 20 (47.6) | ||

| T2 | 10 (13.3) | 11 (22.4) | 6 (14.3) | 10 (23.8) | ||

| T3 | 9 (12) | 5 (10.2) | 6 (14.3) | 4 (9.5) | ||

| T4a | 17 (22.7) | 9 (18.4) | 10 (23.8) | 8 (19) | ||

| pN stage, n (%) | 0.888 | 0.760 | ||||

| N0 | 34 (44.7) | 20 (40.8) | 16 (38.1) | 18 (42.9) | ||

| N1 | 16 (21.1) | 12 (24.5) | 9 (21.4) | 11 (26.2) | ||

| N2 | 14 (18.4) | 7 (14.3) | 9 (21.4) | 5 (11.9) | ||

| N3 | 12 (15.8) | 10 (20.4) | 8 (19) | 8 (19) | ||

| Previous abdominal operation, n (%) | 13 (17.1) | 13 (26.5) | 0.205 | 6 (14.3) | 10 (23.8) | 0.266 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 5 (6.6) | 2 (4.1) | 0.704 | 4 (9.5) | 2 (4.8) | 0.676 |

| Concurrent illness, n (%) | 34 (44.7) | 14 (28.6) | 0.070 | 18 (42.9) | 13 (31.0) | 0.258 |

The operative outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The drain group had a longer operating time than the no-drain group (198.4 ± 41.0 min vs 164.0 ± 37.0 min, P < 0.001). Mean estimated blood loss and intraoperative blood transfusion were similar between the two groups. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the number of retrieved lymph nodes and tumor size (P > 0.05). After PSM, no significant differences were noted in operating time between the drain and no-drain groups.

| Variable | All patients | Propensity-matched patients | ||||

| Drain (n = 76) | No drain (n = 49) | P value | Drain (n = 42) | No drain (n = 42) | P value | |

| Operation time (min) | 198.4 ± 41.0 | 164.0 ± 37.0 | < 0.001 | 180.2 ± 33.4 | 168.0 ± 36.7 | 0.113 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 85.3 ± 80.7 | 70.82 ± 51.5 | 0.267 | 72.9 ± 45.8 | 73.8 ± 54.4 | 0.931 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion, n (%) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (4.1) | 0.645 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.8) | 1.000 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.5 ± 1.6 | 3.6 ± 1.5 | 0.664 | 3.6 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 0.839 |

| No. of retrieved lymph nodes | 36.7 ± 13.7 | 39.1 ± 14.2 | 0.346 | 40.0 ± 11.2 | 40.0 ± 15.1 | 0.923 |

The recovery outcomes are listed in Table 3. The number of days from surgery to the initiation of soft diet (5.34 ± 2.27 d vs 4.17 ± 2.13 d, P = 0.036) and to first flatus (4.29 ± 1.45 d vs 3.55 ± 1.83 d, P = 0.041) were greater in the drain group. There were no significant differences in the time to ambulation or length of postoperative hospital stay (8.15 ± 2.9 d vs 6.77 ± 2.3 d, P = 0.219) between the two groups. Postoperative C-reactive protein levels (8.24 ± 4.47 mg/L vs 8.67 ± 5.97 mg/L, P > 0.05) and postoperative maximum body temperature (Tmax) (37.6 ± 0.6 ℃ vs 37.5 ± 0.4 ℃, P > 0.05) were similar between the two groups. After PSM, only the number of days from surgery to first flatus (4.33 ± 1.24 d vs 3.57 ± 1.85 d, P = 0.029) was greater in the drain group.

| Variable | All patients | Propensity-matched patients | ||||

| Drain (n = 76) | No drain (n = 49) | P value | Drain (n = 42) | No drain (n = 42) | P value | |

| Time to ambulation, POD | 2.51 ± 1.34 | 2.98 ± 1.39 | 0.064 | 2.90 ± 1.54 | 3.07 ± 1.44 | 0.610 |

| Time to first flatus, POD | 3.97 ± 1.24 | 3.55 ± 1.79 | 0.122 | 4.33 ± 1.24 | 3.57 ± 1.85 | 0.029 |

| Time to first eating of soft diet, POD | 4.70 ± 2.17 | 4.14 ± 2.09 | 0.159 | 5.02 ± 1.88 | 4.17 ± 2.20 | 0.058 |

| Postoperative hospital stay | 7.88 ± 3.96 | 6.73 ± 5.13 | 0.164 | 7.93 ± 4.98 | 6.81 ± 5.50 | 0.331 |

| CRP | 7.54 ± 4.38 | 8.53 ± 5.91 | 0.286 | 7.66 ± 3.89 | 8.71 ± 5.95 | 0.339 |

| Tmax | 37.6 ± 0.5 | 37.5 ± 0.4 | 0.239 | 37.60 ± 0.60 | 37.48 ± 0.40 | 0.300 |

Postoperative patient complications are listed in Table 4. No mortality was recorded in either group. The overall postoperative complication rates were 15.8% and 10.2% in the drain and no-drain groups, respectively (P > 0.05). No anastomotic bleeding, anastomotic leakage, lymph leakage, ileus, or pancreatic fistula occurred in either group. Clavien-Dindo grade 3 complications included duodenal stump leakage (n = 2), anastomotic leakage (n = 2), intra-abdominal abscess (n = 2), and intra-abdominal bleeding (n = 1) in the drainage group. The need for percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) was not significantly different between the groups (9.8% vs 6.4%, P = 0.700). After PSM, no significant differences were noted in the complications between the drain and no-drain groups.

| All patients | Propensity-matched patients | |||||

| Complication, n | Drain (n = 76), n (%) | No drain (n = 49), n (%) | P value | Drain (n = 42), n (%) | No drain (n = 42), n (%) | P value |

| Total | 12(15.8) | 5 (10.2) | 0.374 | 8 (19.0) | 4 (9.5) | 0.212 |

| Clavien–Dindo grade II | 4 (5.2) | 2 (4.0) | 3 (7.2) | 1 (2.4) | ||

| Incision | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| System complications | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | ||

| Abdominal effusion | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Clavien–Dindo grade III | 8 (10.6) | 3 (6.0) | 5 (12) | 3 (7.2) | ||

| Duodenal stump leakage | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Anastomotic Leakage | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 3 (3.9) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| Pleural effusion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | ||

| Mortality | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

Postoperative complication risk factors are listed in Table 5. Between the two groups, no significant differences were observed in most variables. However, the patients with a larger BMI had a higher possibility of postoperative complications (27.44 ± 3.92 vs 24.25 ± 3.53, P = 0.01). In addition, we identified that patients with a BMI ≥ 29 kg/m2 were prone to postoperative complications (P = 0.042). A prophylactic drain may be useful in patients with a higher risk, larger BMI, or more concurrent illness. Prophylactic drains was not an independent risk factor for postoperative complications.

| Variable | Postoperative complications (+) (n = 17) | Postoperative complications (-) (n = 108) | P value |

| Sex | 0.584 | ||

| Male | 13 | 74 | |

| Female | 4 | 34 | |

| Age | 59.59 ± 9.62 | 55.70 ± 11.30 | 0.182 |

| BMI (kg/m2), n (%) | 27.44 ± 3.92 | 24.25 ± 3.53 | 0.001 |

| ≥ 29 | 5 (38.5) | 10 (13.3) | 0.042 |

| < 29 | 8 (61.5) | 65 (86.7) | |

| ASA (1/2/3), n (%) | 0.769 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| 2 | 15 (13.2) | 99 (86.8) | |

| 3 | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | |

| Preoperative ALB (g) | 39.62 ± 4.65 | 40.18 ± 5.86 | 0.709 |

| Preoperative HGB (g/L) | 136.59 ± 17.77 | 135.26 ± 19.36 | 0.791 |

| pT stage, n (%) | 0.776 | ||

| T1 | 7 (38.5) | 56 (49.3) | |

| T2 | 4 (23.1) | 17 (20.0) | |

| T3 | 3 (15.4) | 11 (8.0) | |

| T4a | 3 (23.1) | 23 (22.7) | |

| pN stage, n (%) | 0.872 | ||

| N0 | 8 (38.5) | 46 (45.3) | |

| N1 | 3 (15.4) | 25 (22.7) | |

| N2 | 3 (23.1) | 18 (13.3) | |

| N3 | 3 (23.1) | 19 (18.7) | |

| Previous abdominal operation | 0.103 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 25 | |

| No | 16 | 83 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.234 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 5 | |

| No | 15 | 103 | |

| Concurrent illness | 0.800 | ||

| Yes | 7 | 41 | |

| No | 10 | 67 | |

| Drain, n (%) | 12 (15.8) | 64 (84.2) | 0.374 |

| No drain, n (%) | 5 (10.2) | 44 (89.8) | |

| Type of reconstruction, n (%) | 0.357 | ||

| Billroth I | 4 (30.8) | 32 (36.0) | |

| Billroth II | 10 (61.5) | 69 (64.0) | |

| Roux-en-Y | 3 (7.7) | 7 (0.0) | |

| Operative time (min) | 195.82 ± 49.12 | 183.16 ± 41.69 | 0.258 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 62.94 ± 42.54 | 82.22 ± 74.07 | 0.298 |

Since 2015, totally laparoscopic surgery has been widely used in clinical practice, although there are few reports on whether totally laparoscopic surgery requires prophylactic drains[10,11]. Most studies on prophylactic drains were based on open gastrectomy. Cochrane review included four single-institution, randomized controlled trials that sought to evaluate the role of prophylactic drain placement in gastric resection for gastric cancer[12-14]. In this study, we reviewed the clinicopathological data of patients with gastric cancer during the past 2 years and found that routine prophylactic drains were not necessary in selected patients. To minimize the risk of confounding variables, PSM was used. Routine prophylactic drains are not necessary in all patients. A prophylactic drain may be useful in patients at higher risk.

Prophylactic drains have been used to enhance early detection of complications, prevent collection of fluid, reduce morbidity and mortality, and decrease the duration of hospital stay[15,16]. The present study results showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of postoperative hospital stay. The length of the postoperative hospital stay in the no-drain group was shorter than that in the drain group (7.93 ± 4.98 d vs 6.81 ± 5.50 d, P > 0.05). Among the 17 patients who experienced postoperative complications, there was also no significant difference between the two groups in terms of postoperative hospital stay. This result was different from that of Hirahara et al[10] study. In addition, omitting prophylactic drainage significantly improved the postoperative comfort of patients due to an earlier flatus (4.33 ± 1.24 d vs 3.57 ± 1.85 d, P < 0.05).

Moreover, the application of prophylactic drains did not reduce the incidence of complications, and the rate of complications was even higher in the drain group. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (19.0% vs 9.5%, P > 0.05). Through risk assessment, we identified that patients with a BMI ≥ 29 kg/m2 are prone to postoperative complications (P = 0.042). More visceral fat may make surgery more difficult. Thus, prophylactic drain is recommended for patients with a BMI > 29 kg/m2.

For patients with mild symptoms, administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics may be a good conservative management strategy. However, patients with severe symptoms need PCD. In the current study, postoperative complications were recognized in approximately 15% of patients. Two cases of duodenal stump leakage and two cases of intra-abdominal abscess occurred in the drain group, all of which required PCD. In the no-drain group, two cases of intra-abdominal abscess and one case of pleural effusion needed PCD. There was no significant difference between the two groups. Prophylactic drains do not alter the rates of secondary drainage procedures. Thus, omitting prophylactic drains during gastric cancer surgery did not increase the risk of PCD postoperatively. Similarly, in a study by Lee et al[16], omitting prophylactic drains did not increase the risk of PCD postoperatively, while male sex, older age, and longer operative time were identified as independent risk factors for postoperative PCD in patients without prophylactic drains.

In conclusion, omitting the use of prophylactic drains in selected patients during surgery for gastric cancer is feasible. It can significantly improve the postoperative comfort of patients and does not increase the risk of postoperative complications.

Prophylactic drains have been used to remove intraperitoneal collections and detect complications early in open surgery. In the last decades, minimally invasive gastric cancer surgery has been performed worldwide. However, reports on routine prophylactic abdominal drainage after totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy are few.

To evaluate the feasibility of performing totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy without prophylactic drains in selected patients.

To evaluate the feasibility of performing totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy without prophylactic drains in selected patients.

Data of patients with distal gastric cancer who underwent totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with and without prophylactic drainage at China National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital from February 2018 to August 2019 were reviewed.

After PSM, data of 42 pairs were extracted. The incidence of concurrent illness was higher in the drain group (42.9% vs 31.0%, P = 0.258). The overall postoperative complication rates were 19.5% and 10.6% in the drain (n = 76) and no-drain groups (n = 49), respectively; there were no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). The difference between the two groups based on the need for percutaneous catheter drainage was also not significant (9.8% vs 6.4%, P = 0.700). However, patients with a larger body mass index (≥ 29 kg/m2) were prone to postoperative complications (P = 0.042). In addition, the number of days from surgery until the first flatus (4.33 ± 1.24 d vs 3.57 ± 1.85 d, P = 0.029) was greater in the drain group.

Omitting prophylactic drainage may reduce surgery time and result in faster recovery. Routine prophylactic drains are not necessary in selected patients. A prophylactic drain may be useful in high-risk patients.

Omitting the use of prophylactic drains can significantly improve the postoperative comfort of patients and does not increase the risk of postoperative complications.

| 1. | Smith RJ, Bryant RG. Metal substitutions incarbonic anhydrase: a halide ion probe study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;66:1281-1286. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13333] [Article Influence: 1333.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146-148. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, Ryu SW, Lee HJ, Song KY. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy vs open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report--a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized Trial (KLASS Trial). Ann Surg. 2010;251:417-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 562] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yu J, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, Wang K, Suo J, Tao K, He X, Wei H, Ying M, Hu W, Du X, Hu Y, Liu H, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Liu F, Li Z, Zhao G, Yang K, Liu C, Li H, Chen P, Ji J, Li G; Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (CLASS) Group. Effect of Laparoscopic vs Open Distal Gastrectomy on 3-Year Disease-Free Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: The CLASS-01 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1983-1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 80.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Kim MG, Kawada H, Kim BS, Kim TH, Kim KC, Yook JH. A totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with gastroduodenostomy (TLDG) for improvement of the early surgical outcomes in high BMI patients. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1076-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim MG, Kim KC, Kim BS, Kim TH, Kim HS, Yook JH. A totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy can be an effective way of performing laparoscopic gastrectomy in obese patients (body mass index≥30). World J Surg. 2011;35:1327-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ishikawa K, Matsumata T, Kishihara F, Fukuyama Y, Masuda H. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer with vs without prophylactic drainage. Surg Today. 2011;41:1049-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1956] [Article Influence: 217.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Hayashi H, Takai K, Fujii Y, Tajima Y. Significance of prophylactic intra-abdominal drain placement after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shimoike N, Akagawa S, Yagi D, Sakaguchi M, Tokoro Y, Nakao E, Tamura T, Fujii Y, Mochida Y, Umemoto Y, Yoshimoto H, Kanaya S. Laparoscopic gastrectomy with and without prophylactic drains in gastric cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alvarez Uslar R, Molina H, Torres O, Cancino A. Total gastrectomy with or without abdominal drains. A prospective randomized trial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:562-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kumar M, Yang SB, Jaiswal VK, Shah JN, Shreshtha M, Gongal R. Is prophylactic placement of drains necessary after subtotal gastrectomy? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3738-3741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim J, Lee J, Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Chen J, Choi SH, Noh SH. Gastric cancer surgery without drains: a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:727-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Messager M, Sabbagh C, Denost Q, Regimbeau JM, Laurent C, Rullier E, Sa Cunha A, Mariette C. Is there still a need for prophylactic intra-abdominal drainage in elective major gastro-intestinal surgery? J Visc Surg. 2015;152:305-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee J, Choi YY, An JY, Seo SH, Kim DW, Seo YB, Nakagawa M, Li S, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH. Do All Patients Require Prophylactic Drainage After Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3929-3937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Amin S, Chen Y, Park J, Tsegmed U S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL