Published online Jun 21, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i23.3386

Peer-review started: December 25, 2020

First decision: February 28, 2021

Revised: April 14, 2021

Accepted: May 22, 2021

Article in press: May 22, 2021

Published online: June 21, 2021

Processing time: 175 Days and 1.2 Hours

Although dumping symptoms constitute the most common post-gastrectomy syndromes impairing patient quality of life, the causes, including blood sugar fluctuations, are difficult to elucidate due to limitations in examining dumping symptoms as they occur.

To investigate relationships between glucose fluctuations and the occurrence of dumping symptoms in patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

Patients receiving distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I (DG-BI) or Roux-en-Y reconstruction (DG-RY) and total gastrectomy with RY (TG-RY) for gastric cancer (March 2018-January 2020) were prospectively enrolled. Interstitial tissue glycemic profiles were measured every 15 min, up to 14 d, by continuous glucose monitoring. Dumping episodes were recorded on 5 patient-selected days by diary. Within 3 h postprandially, dumping-associated glycemic changes were defined as a dumping profile, those without symptoms as a control profile. These profiles were compared.

Thirty patients were enrolled (10 DG-BI, 10 DG-RY, 10 TG-RY). The 47 early dumping profiles of DG-BI showed immediately sharp rises after a meal, which 47 control profiles did not (P < 0.05). Curves of the 15 late dumping profiles of DG-BI were similar to those of early dumping profiles, with lower glycemic levels. DG-RY and TG-RY late dumping profiles (7 and 13, respectively) showed rapid glycemic decreases from a high glycemic state postprandially to hypoglycemia, with a steeper drop in TG-RY than in DG-RY.

Postprandial glycemic changes suggest dumping symptoms after standard gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Furthermore, glycemic profiles during dumping may differ depending on reconstruction methods after gastrectomy.

Core Tip: Glucose variability at dumping onset was investigated using continuous glucose monitoring and subject diaries after standard gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Postprandial glycemic changes suggest both early and late dumping symptoms. Glycemic profiles during dumping may differ depending on reconstruction methods after gastrectomy, considering the similar glucose fluctuation curves with both early and late dumping after distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction and rapidly decreasing glucose profiles with late dumping after distal and total gastrectomy, both with Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

- Citation: Ri M, Nunobe S, Ida S, Ishizuka N, Atsumi S, Makuuchi R, Kumagai K, Ohashi M, Sano T. Preliminary prospective study of real-time post-gastrectomy glycemic fluctuations during dumping symptoms using continuous glucose monitoring. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(23): 3386-3395

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i23/3386.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i23.3386

Globally, gastric cancer (GC) is among the most life-threatening malignancies[1,2]. Gastric resection with lymph node dissection is still the only curative treatment option for resectable GC, though it is noteworthy that early lesions can be resected endoscopically[3]. However, gastrectomy can result in various gastrointestinal symptoms known as post-gastrectomy syndrome, which is characterized by functional deficits and disorders due to loss of some or all of the stomach, often giving rise to clinical issues reflecting deterioration of quality of life for patients[4,5].

Dumping symptoms constitute the most common post-gastrectomy syndrome adversely affecting quality of life[6-8]. According to the time of onset, dumping syndrome is classified into early and late symptoms[9,10] but cannot always be clearly separated into these two categories. Therefore, while some patients develop either early or late dumping symptoms, others may have both. The mechanisms underlying late dumping symptoms especially are thought to involve hypoglycemia in response to hyperinsulinemia after carbohydrate ingestion[10,11]. However, blood glucose changes appearing while patients experience dumping symptoms are still not fully understood because a method allowing blood glucose to be measured easily and continuously has been lacking.

However, the continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system developed for the management of diabetes allows interstitial glucose levels, which are closely related to blood glucose levels, to be tracked continuously[12,13]. Therefore, details of the 24 h glycemic profile, which includes both postprandial and nocturnal trends not measurable with a simple conventional glucometer, can be obtained using CGM. This also means that CGM has the potential to provide essential information about the glucose profiles of patients suffering from dumping symptoms after gastrectomy.

Herein, we designed a prospective exploratory pilot study to investigate relation

During the period from March 2018 to January 2020, patients who underwent distal or total gastrectomy for GC at the Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Cancer Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, were prospectively enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Diagnosed as having pathological stage I or II gastric adenocarcinoma, underwent R0 resection, age 20 to 75 years, 3 mo to 3 years after the operation and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status score 0 or 1. Patients with simultaneous resection of other organs (other than cholecystectomy or splenectomy), diabetes under treatment, receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, and/or taking supplements including enteral nutrition were excluded. Pathological stages were determined according the 14th edition of the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma[14]. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Cancer Institute Hospital (No. 2017-1110). All participants signed a written informed consent for the present study. All protocols are carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines.

FreeStyle Libre Pro (Abbot Diabetes Care Inc., Alameda, CA, United States), a CGM device, was used to continuously measure glucose concentrations. The sensor attached to the posterior surface of the patient’s upper arm continuously measured and recorded the glucose concentration in the subcutaneous tissue interstitial fluid every 15 min for up to 14 d. Measurement results automatically saved on the sensor were transferred wirelessly to the reader and then analyzed using FreeStyle Libre Pro Software via the reader.

Dumping symptoms were evaluated using a diary recording diet and symptoms. Diary entries were made every 15 min and listed the 15 typical symptoms related to dumping, as previously reported[15,16]. The patient filled in the times of starting and completing meals, whether symptoms appeared, allowing the times and corresponding symptoms to be checked. Considering that patient dietary records after gastrectomy often document three or more meals, snacks described by the patient as being about the same amount as an ordinary meal were regarded as meals and were recorded as such in the diary. The diary entries were made for 5 patient-selected days within the 14 d period with the sensor attached.

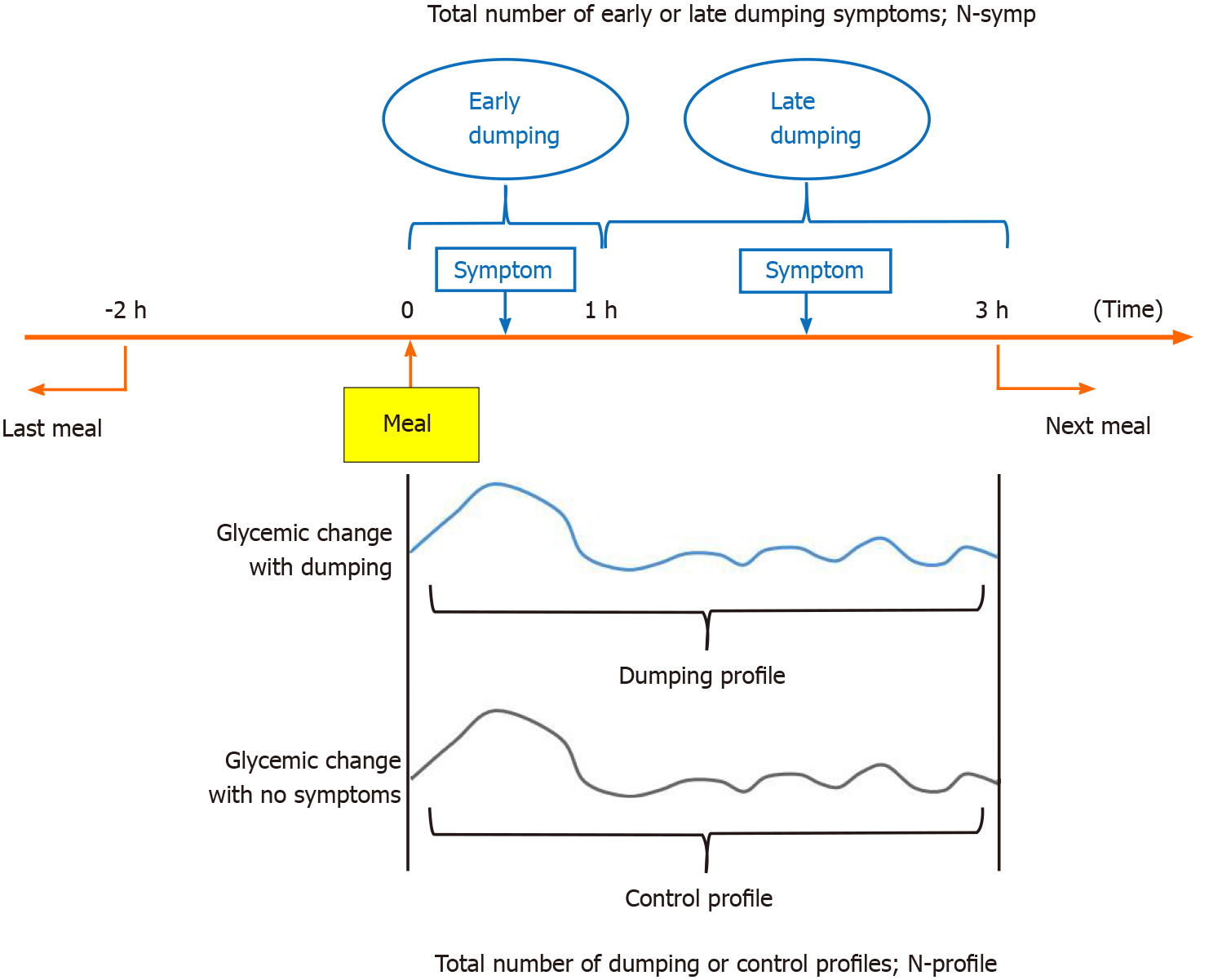

Our strategy for defining the dumping and control profiles is presented in Figure 1. Dumping syndrome is defined as the development of one or more of the 15 symptoms listed in the diary within 3 h of eating a meal. Furthermore, symptoms that occurred within 1 h after the start of a meal were regarded as early dumping and those occurring within 1 h to 3 h after starting a meal were regarded as late dumping, as previously reported[10,17]. To avoid effects of the intakes of other foods, we excluded cases in which another meal was consumed from two hours before to three hours after the baseline meal. The total number of symptoms was described as N-symp. In addition, within 3 h after the start of a meal, glycemic changes associated with early or late dumping symptoms were defined as a dumping profile, while those with no symptoms were defined as a control profile. The control profiles consisted of up to one series per patient per day. The total number with each profile was designated the N-profile. If multiple symptoms appeared simultaneously, the symptoms were counted accordingly, and the profile was only counted once.

The patient background characteristics, surgical details and postoperative findings were collected from our database and information contained in electronic medical records. Based on the glucose concentration values measured every 15 min by CGM and the details of the dumping symptoms described in the diary, dumping and control profiles were compared. All missing values in the data obtained employing CGM were replaced by linear interpolation as single imputation method[18]. All continuous variables were expressed as median values. Although we used P value of Mann-Whitney U test and the χ2 test in addition to basic statistics, statistical analysis is solely exploratory and descriptive without any formal general linear models. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Naoki Ishizuka, a biostatistician. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP Pro 13 (SAS Institute Japan Ltd, Japan) for Windows.

Patient background data are presented in Table 1. In total, 30 patients were enrolled prospectively: 10 patients each underwent distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction (DG-BI), distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (DG-RY) and total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TG-RY). The DG-BI group had a significantly shorter period since surgery than the other two surgical groups (P = 0.01). Surgical approach, degree of lymph node dissection and pathological stage differed significantly among the three groups. There were no significant differences in nutritional status or HbA1c levels among the three groups.

| DG-BI, n = 10 | DG-RY, n = 10 | TG-RY, n = 10 | P value | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.30 | |||

| Male | 3 (30) | 6 (60) | 6 (60) | |

| Female | 7 (70) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | |

| Age, yr (IQR) | 60 (48-70) | 63 (55-68) | 62 (46-70) | 0.97 |

| Period from operation, mo (IQR) | 7.1 (6.7-19.2) | 23.5 (19.5-26.6) | 20.3 (14.9-26.1) | 0.01 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (IQR) | 19.0 (16.1-23.1) | 21.3 (18.4-23.5) | 20.5 (19.4-23.1) | 0.32 |

| Serum total protein, g/dL (IQR) | 7.1 (6.8-7.4) | 7.0 (6.7-7.3) | 6.8 (6.5-7.3) | 0.57 |

| Serum prealbumin, mg/dL (IQR) | 23.4 (18.6-28.7) | 23.0 (21.8-29.3) | 22.0 (18.4-26.5) | 0.62 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL (IQR) | 4.3 (4.2-4.6) | 4.2 (4.0-4.5) | 4.1 (4.1-4.3) | 0.45 |

| Serum hemoglobin, g/dL (IQR) | 12.9 (12.2-14.3) | 13.6 (12.2-15.0) | 12.1 (11.3-13.2) | 0.21 |

| Blood glucose level, mg/dL (IQR) | 96 (95-99) | 96 (89-114) | 93 (88-100) | 0.73 |

| HbA1c, % (IQR) | 5.7 (5.3-5.9) | 5.7 (5.6-5.9) | 5.6 (5.5-5.8) | 0.73 |

| Approach | < 0.01 | |||

| Open | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | 6 (60) | |

| Laparoscopic | 10 (100) | 8 (80) | 4 (40) | |

| Lymph node dissection, n (%) | < 0.01 | |||

| D1+ | 10 (100) | 5 (50) | 2 (20) | |

| D2 | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 8 (80) | |

| pStage, n (%) | < 0.01 | |||

| I | 10 (100) | 9 (90) | 3 (30) | |

| II | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 7 (70) |

The details of early and late dumping symptoms are shown in Tables 2 and 3. In all patients, early dumping symptoms consisted mainly of abdominal symptoms such as borborygmi, bloating and abdominal pain (Table 2). The rates of borborygmi in TG-RY, bloating in DG-BI and drowsiness in DG-RY were significantly higher than those associated with other procedures. On the other hand, late dumping exhibited a wide range of symptoms in all three patient groups, and hypoglycemic symptoms such as cold sweat and drowsiness were relatively common among the features of late dumping syndrome (Table 3).

| Early dumping symptoms | |||||

| All, N-symp = 185 | DG-BI, N-symp = 80 | DG-RY, N-symp = 35 | TG-RY, N-symp = 70 | P value | |

| Borborygmi | 49 (26.5) | 14 (17.5) | 9 (25.7) | 26 (37.1) | 0.02 |

| Bloating | 47 (25.4) | 28 (35.0) | 4 (11.4) | 15 (21.4) | 0.01 |

| Abdominal pain | 21 (11.4) | 9 (11.3) | 2 (5.7) | 10 (14.3) | 0.42 |

| Drowsiness | 21 (11.4) | 9 (11.3) | 8 (22.9) | 4 (5.7) | 0.03 |

| Palpitation | 15 (8.1) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (5.7) | 10 (14.3) | 0.05 |

| Weakness | 11 (5.9) | 6 (7.5) | 3 (8.6) | 2 (2.9) | 0.37 |

| Others | 21 (11.4) | 11 (13.8) | 7 (20.0) | 3 (4.3) | 0.03 |

| Late dumping symptoms | |||||

| All, N-symp = 62 | DG-BI, N-symp = 28 | DG-RY, N-symp = 12 | TG-RY, N-symp = 22 | P value | |

| Cold sweat | 9 (14.5) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (18.2) | 0.73 |

| Drowsiness | 8 (12.9) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (18.2) | 0.64 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (12.9) | 5 (17.9) | 3 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0.06 |

| Weakness | 6 (9.7) | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (13.6) | 0.42 |

| Bloating | 6 (9.7) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (9.1) | 0.96 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 (9.7) | 1 (3.6) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.10 |

| Borborygmi | 5 (8.1) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0.18 |

| Palpitations | 4 (6.5) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (13.6) | 0.21 |

| Tremulousness | 4 (6.5) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.57 |

| Others | 6 (9.7) | 4 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.37 |

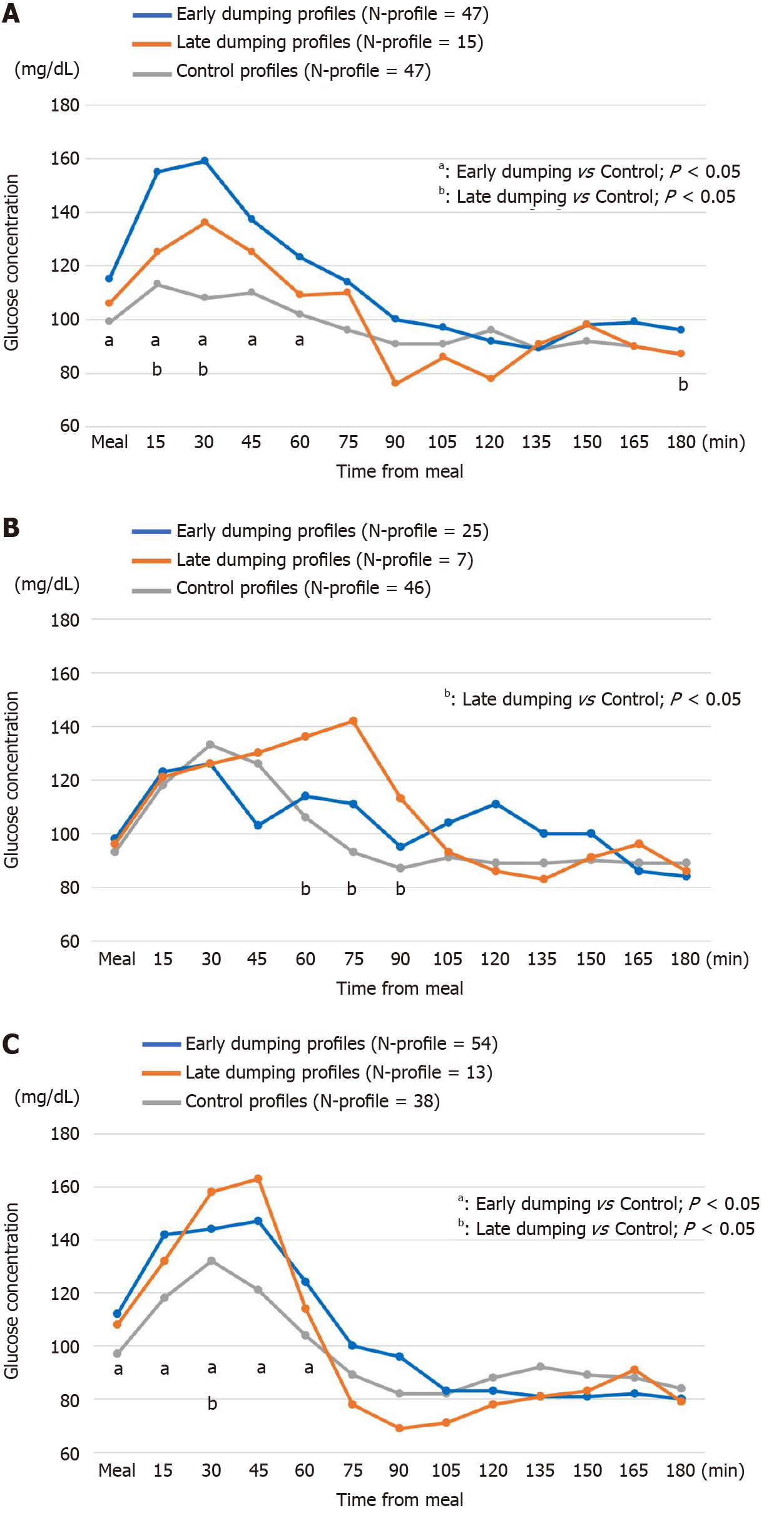

Dumping and control profiles obtained by CGM and the diary results are shown in Figure 2. During the 5 d of diary recording, the respective N-profiles of early dumping were 47, 25 and 54, those of late dumping were 15, 7 and 13, in the order of DG-BI, DG-RY and TG-RY.

The early dumping profiles in DG-BI showed a sharp and immediate rise when starting a meal and then dropped, with significant increases up to 60 min postprandially as compared with the control group (P < 0.05, Figure 2A). The curves of late dumping profiles in DG-BI were similar to those of early dumping profiles, with generally lower glucose levels (Figure 2A). The early dumping profiles in TG-RY increased significantly from the start of a meal up to 60 min postprandially as compared to the control profiles (P < 0.05, Figure 2C).

When late dumping developed in DG-RY and TG-RY (Figure 2B and 2C), the dumping profiles in the former showed a sharp decrease from the peak glycemic value at 75 min after starting a meal. A similar but more rapid drop was observed in the dumping profiles in TG-RY from the hyperglycemic state at 45 min after starting a meal. Most notably, glucose levels in TG-RY ultimately decreased to 69 mg/dL at 90 min postprandially.

Dumping syndrome was first reported by Mix in 1922 as a serious complication of gastrectomy[19]. Several mechanisms have been speculated to underlie the development of dumping symptoms[9,10,20]. In early dumping, because of the rapid flow of hyperosmolar food into the jejunum, the plasma fluid rapidly moves into the intestinal lumen and the plasma volume decreases. Furthermore, the release of gastrointestinal hormones, including vasoactive agents, incretins and glucose modulators, is also increased[21]. Consequently, vasomotor symptoms such as palpitations, weakness and faintness and gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating and borborygmi develop[10]. On the other hand, hypoglycemia in response to hyperinsulinemia after carbohydrate ingestion has been said to cause hypoglycemic symptoms including the drowsiness and cold sweat characteristic of late dumping[9,10,20]. In fact, early and late dumping symptoms similar to those previously reported were also observed in the present study. However, the causes of the onset of dumping symptoms have not yet been sufficiently elucidated because, as mentioned above, it is difficult to measure changes in plasma volume, various hormones and blood glucose levels when a dumping symptom is actually occurring.

To our knowledge, this is the first exploratory study of real-time changes in glucose profiles when a dumping symptom actually occurs after gastrectomy using CGM and daily recording of diet and symptoms. Although a few studies have demonstrated continuous glucose profiles using CGM after GC surgery, with most simply measuring the glucose fluctuations, the occurrence of dumping symptoms over time has not previously been examined[22-24]. Results of the present study indicated glucose fluctuations to be involved in the onset of late dumping as well as early dumping symptoms after standard gastrectomy for GC.

The early dumping profiles in DG-BI showed rises immediately after the start of meals and subsequently dropped in contrast to the control profiles. Postprandial hyperglycemia is usually observed in patients with impaired glucose tolerance, which is representative of diabetes. However, it was recently found that healthy subjects without diabetes show a similar phenomenon called a blood glucose spike[25]. Although the main mechanisms have been considered to differ between early and late dumping symptoms, a series of similar mechanisms might underlie the development of both early and late dumping symptoms, considering that similar curves of glycemic changes were observed in both symptomatic groups. Mine et al[8], who demonstrated a strong correlation between early and late dumping, suggested that a faster or greater flow of food into the small intestine may be the cause of both of early and late dumping symptoms.

On the other hand, in the late dumping profiles in DG-RY and TG-RY, a marked decrease in glucose levels was observed from a high glycemic state around 1 h after starting a meal to a hypoglycemic level around 2 h postprandially. Although hypo

Although a similar glycemic variability was observed in the late dumping groups that had undergone DG-RY and TG-RY, the curve of glucose profiles was steeper in the TG-RY than in the DG-RY dumping group. Due to the lack of storage capacity, that is the absence of part or all of the stomach, there might be a faster flow of food into the jejunum in TG-RY than in DG-RY, resulting in a more rapid glucose level change and higher number of dumping symptoms. In contrast, some of the observed variation in glycemic profiles might have been due to differences in the size of the remnant stomach in DG-RY, resulting in a lack of statistical significance. In addition, considering that the control profiles in DG-RY and TG-RY were more remarkable than those in DG-BI, RY reconstruction, a non-physiological reconstruction method in which food does not pass through the duodenum, may impact glucose fluctuations after a meal more adversely than the other procedures.

The present study has potential limitations. First, although prospective, this was a preliminary study with a small sample size conducted at a single institution. It is possible that statistical differences could not be demonstrated due to the small number of events. In addition, variation in the frequency of dumping among patients might have produced statistical bias. Further accumulation of cases, allowing a study with a larger sample size, is needed. Second, postoperative periods were not similar among the three groups. Although we aimed herein to enroll patients in the mid to long term after surgery, differences in postoperative periods may have influenced the onset of dumping symptoms and glycemic change. Third, dietary details were not documented in this study. Caloric intake has a significant effect on blood glucose levels, and the manner in which a meal is consumed may affect the onset of dumping symptoms. Finally, although glucose profiles and dumping symptoms were sequentially investigated, other factors possibly involved in the onset of dumping were not examined. The evaluation of changes in hemodynamics and various hormones, which are considered to be factors causing dumping, is another topic for future research.

Postprandial rapid glycemic changes appear to be involved in the onset of early and late dumping symptoms after standard gastrectomy for GC. Given the similar glucose fluctuation curves with early and late dumping in DG-BI and the rapid decrease in glucose profiles with late dumping in DG-RY and TG-RY, the glycemic profiles associated with dumping symptoms may differ depending on the reconstruction methods employed after gastrectomy.

Dumping symptoms constitute the most common post-gastrectomy syndrome adversely affecting quality of life. However, the causes of dumping symptoms, including blood glucose changes, remain poorly understood due to limitations in examining dumping symptoms as they occur.

The continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system, which continuously measures interstitial glucose levels to reflect blood glucose levels, was developed for the management of diabetes. CGM also has the potential to provide long awaited essential information about the glucose profiles of patients suffering from dumping symptoms after gastrectomy.

We designed a prospective pilot study to investigate relationships between glucose fluctuations and the occurrence of dumping symptoms in patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer (GC). Our results may contribute to devising future treatments for dumping syndrome.

During the period from March 2018 to January 2020, GC patients who underwent distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction (DG-BI), distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (DG-RY) or total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y recon

Thirty patients were enrolled (10 DG-BI, 10 DG-RY, 10 TG-RY). The early dumping profiles of DG-BI (47 profiles) showed a sharp and immediate rise after a meal, with significant increases up to 60 min postprandially as compared with the control group (47 profiles) (P < 0.05). The curves of late dumping profiles in DG-BI were similar to those of early dumping profiles, with generally lower glucose levels. DG-RY and TG-RY late dumping profiles (7 and 13, respectively) showed rapid glycemic decreases from a high glycemic state postprandially to hypoglycemia, with the drop being steeper in TG-RY than in DG-RY.

Postprandial rapid glycemic changes appear to be involved in the onset of early and late dumping symptoms after standard gastrectomy for GC. In addition, the glycemic profiles associated with dumping symptoms may differ depending on the reconstruction methods employed after gastrectomy, considering the similar glucose fluctuation curves with both early and late dumping after DG-BI and rapidly decreasing glucose profiles with late dumping after DG-RY and TG-RY.

We will conduct a prospective interventional study with the aim of developing new treatments ameliorating dumping symptoms associated with GC surgery.

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21463] [Article Influence: 1951.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56656] [Article Influence: 7082.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (134)] |

| 3. | Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ, Welvaart K, Songun I, Meyer S, Plukker JT, Van Elk P, Obertop H, Gouma DJ, van Lanschot JJ, Taat CW, de Graaf PW, von Meyenfeldt MF, Tilanus H; Dutch Gastric Cancer Group. Extended lymph-node dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:908-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1158] [Cited by in RCA: 1072] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Bolton JS, Conway WC 2nd. Postgastrectomy syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:1105-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Davis JL, Ripley RT. Postgastrectomy Syndromes and Nutritional Considerations Following Gastric Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:277-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Bender MA, Moore GE, Webber BM. Dumping syndrome; an evaluation of some current etiologic concepts. N Engl J Med. 1957;256:285-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abbott WE, Krieger H, Levey S, Bradshaw J. The etiology and management of the dumping syndrome following a gastroenterostomy or subtotal gastrectomy. Gastroenterology. 1960;39:12-27. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Mine S, Sano T, Tsutsumi K, Murakami Y, Ehara K, Saka M, Hara K, Fukagawa T, Udagawa H, Katai H. Large-scale investigation into dumping syndrome after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:628-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tack J, Arts J, Caenepeel P, De Wulf D, Bisschops R. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of postoperative dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Beek AP, Emous M, Laville M, Tack J. Dumping syndrome after esophageal, gastric or bariatric surgery: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Obes Rev. 2017;18:68-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Machella TE. The Mechanism of the Post-gastrectomy "Dumping" Syndrome. Ann Surg. 1949;130:145-159. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bolinder J, Antuna R, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P, Kröger J, Weitgasser R. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, non-masked, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2254-2263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 66.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wood A, O'Neal D, Furler J, Ekinci EI. Continuous glucose monitoring: a review of the evidence, opportunities for future use and ongoing challenges. Intern Med J. 2018;48:499-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2947] [Article Influence: 196.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Linehan IP, Weiman J, Hobsley M. The 15-minute dumping provocation test. Br J Surg. 1986;73:810-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vecht J, Masclee AA, Lamers CB. The dumping syndrome. Current insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1997;223:21-27. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Arts J, Caenepeel P, Bisschops R, Dewulf D, Holvoet L, Piessevaux H, Bourgeois S, Sifrim D, Janssens J, Tack J. Efficacy of the long-acting repeatable formulation of the somatostatin analogue octreotide in postoperative dumping. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Millard LAC, Patel N, Tilling K, Lewcock M, Flach PA, Lawlor DA. GLU: a software package for analysing continuously measured glucose levels in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:744-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mix C. Dumping stomach following gastrojejunostomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1922;2:617-622. |

| 20. | Tack J. Gastric motor disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:633-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Øhrstrøm CC, Worm D, Kielgast UL, Holst JJ, Hansen DL. Evidence for Relationship Between Early Dumping and Postprandial Hypoglycemia After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg. 2020;30:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Buscemi S, Mattina A, Genova G, Genova P, Nardi E, Costanzo M. Seven-day subcutaneous continuous glucose monitoring demonstrates that treatment with acarbose attenuates late dumping syndrome in a woman with gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kurihara K, Tamai A, Yoshida Y, Yakushiji Y, Ueno H, Fukumoto M, Hosoi M. Effectiveness of sitagliptin in a patient with late dumping syndrome after total gastrectomy. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kubota T, Shoda K, Ushigome E, Kosuga T, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Kudo M, Arita T, Murayama Y, Morimura R, Ikoma H, Kuriu Y, Nakanishi M, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Fukui M, Otsuji E. Utility of continuous glucose monitoring following gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:699-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hall H, Perelman D, Breschi A, Limcaoco P, Kellogg R, McLaughlin T, Snyder M. Glucotypes reveal new patterns of glucose dysregulation. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2005143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Abrahamsson N, Edén Engström B, Sundbom M, Karlsson FA. Hypoglycemia in everyday life after gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:91-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Laurenius A, Werling M, Le Roux CW, Fändriks L, Olbers T. More symptoms but similar blood glucose curve after oral carbohydrate provocation in patients with a history of hypoglycemia-like symptoms compared to asymptomatic patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:1047-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Salehi M, Gastaldelli A, D'Alessio DA. Blockade of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor corrects postprandial hypoglycemia after gastric bypass. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 669-680. e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tariciotti L S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH