Published online Feb 21, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i7.759

Peer-review started: November 2, 2019

First decision: December 4, 2019

Revised: December 29, 2019

Accepted: January 19, 2020

Article in press: January 19, 2020

Published online: February 21, 2020

Processing time: 110 Days and 2.9 Hours

Emergency situations in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) put significant burden on both the patient and the healthcare system.

To prospectively measure Quality-of-Care indicators and resource utilization after the implementation of the new rapid access clinic service (RAC) at a tertiary IBD center.

Patient access, resource utilization and outcome parameters were collected from consecutive patients contacting the RAC between July 2017 and March 2019 in this observational study. For comparing resource utilization and healthcare costs, emergency department (ED) visits of IBD patients with no access to RAC services were evaluated between January 2018 and January 2019. Time to appointment, diagnostic methods, change in medical therapy, unplanned ED visits, hospitalizations and surgical admissions were calculated and compared.

488 patients (Crohn’s disease: 68.4%/ulcerative colitis: 31.6%) contacted the RAC with a valid medical reason. Median time to visit with an IBD specialist following the index contact was 2 d. Patients had objective clinical and laboratory assessment (C-reactive protein and fecal calprotectin in 91% and 73%). Fast-track colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy was performed in 24.6% of the patients, while computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging in only 8.1%. Medical therapy was changed in 54.4%. ED visits within 30 d following the RAC visit occurred in 8.8% (unplanned ED visit rate: 5.9%). Diagnostic procedures and resource utilization at the ED (n = 135 patients) were substantially different compared to RAC users: Abdominal computed tomography was more frequent (65.7%, P < 0.001), coupled with multiple specialist consults, more frequent hospital admission (P < 0.001), higher steroid initiation (P < 0.001). Average medical cost estimates of diagnostic procedures and services per patient was $403 CAD vs $1885 CAD comparing all RAC and ED visits.

Implementation of a RAC improved patient care by facilitating easier access to IBD specific medical care, optimized resource utilization and helped avoiding ED visits and subsequent hospitalizations.

Core tip: The present study reports a comprehensive analysis of patient access, resource utilization, costs and outcome measures of a newly implemented formal inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) specific rapid access clinic service compared to usual emergency department visits in IBD patients from a single academic center in North America. Creating a rapid access clinic service for IBD patients is associated with quick patient access, optimized and specific use of diagnostic procedures and services, with similar outcome parameters and lower resource utilization and overall costs compared to regular emergency department visits for IBD patients.

- Citation: Nene S, Gonczi L, Kurti Z, Morin I, Chavez K, Verdon C, Reinglas J, Kohen R, Bessissow T, Afif W, Wild G, Seidman E, Bitton A, Lakatos PL. Benefits of implementing a rapid access clinic in a high-volume inflammatory bowel disease center: Access, resource utilization and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(7): 759-769

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i7/759.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i7.759

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory conditions which affect the patient’s physical health, quality of life and social functioning. This creates an ongoing need for interactions with the healthcare system, as IBD patients are known to have high risk for developing severe disease related complications, as well as drug related adverse events[1,2]. As a result, IBD patients are high consumers of acute-care services and the initial point of care for persons having acute health issues related to their IBD are typically the emergency department (ED)[3]. Seeking medical care through the ED has been shown to cause a significant socio-economic impact on our health care system due to the substantial burden of resource utilization, especially in chronic conditions, such as IBD[4].

IBD, similar to many other chronic and progressive conditions require continuous follow-up. In the last decade, therapeutic options and tools for disease monitoring have become increasingly complex, which led to a paradigm shift in IBD management. Objective therapeutic targets/endpoints have been defined and more rigorous disease monitoring strategies have been put forward in many expert recommendations, which all require continuous interactions with IBD specialist physicians[5,6]. Recently, multiple quality of care indicators have been developed to ensure a standardized and high quality care in IBD management. Among many, patient satisfaction is thought to be an integral part of high quality of care[7]. Several data show that “patient access” to treating physician or healthcare services in general is frequently a source of inadequate satisfaction among IBD patients[8,9].

ED services are best reserved for acute, serious and/or life-threatening disease states. Thus optimising and reducing patient load to the ED is an important goal for global healthcare delivery[10]. A large proportion of patients with known chronic conditions could potentially be managed in alternative care settings, more specific to their disease. These specific “rapid access” patient pathways for “rapid” evaluation and management can be established through regular outpatient care providers, which can potentially reduce ED visits, thus saving costs. There are examples for a good performance of rapid access clinics (RAC) in other chronic conditions, e.g., diabetes or cardiology[11,12]. Until now, there is no well-defined framework of outpatient RAC in IBD centers across North America. A RAC service can provide quick access and rapid evaluation by an IBD specialist for patients experiencing moderate to severe symptoms in non-emergency situations related to IBD, thus potentially avoiding ED visits. In this study, we aimed to prospectively measure quality of care indicators by assessing patient access, diagnostic procedures, resource utilization and outcome parameters after the implementation of a new, formal RAC service at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) tertiary care IBD center. We also aimed to compare the resource utilization and costs of the RAC with regular ED visits of other IBD patients having no access to RAC services.

The MUHC IBD center consists of a team of medical professionals including IBD specialized gastroenterologists and fellows, IBD nurses, research fellows who work closely with other consulting professionals to offer a continuous, multi-faceted care to IBD patients[13]. The formal RAC service was established within the MUHC IBD center. Treating physicians provided emergency contact information (ema-il/telephone) to all patients, as well as a framework of indications for appropriate consultation to the RAC, known as the Urgent IBD care plan (Supplementary Figure 1). Each email was read and reviewed by an IBD-specialised nurse and/or physician. The patients were offered a RAC visit if the request was deemed appropriate. Consecutive patients from the MUHC IBD Center who contacted the RAC via email/telephone or personal visit between July 2017 and April 2019 were prospectively included in this study. Only those above the age of 18 with a known diagnosis of IBD and followed-up at the MUHC IBD center by a member of the gastroenterology service were offered the RAC service. Patients with a recent diagnosis (less than 1 year) or an uncertain diagnosis of IBD were excluded.

Patient and disease related demographics including disease phenotype and severity as well as current and previous medication history was captured upon the RAC visits. Patient access to the RAC in terms of the validity of the request, and time to medical appointment were evaluated. Resource utilization included laboratory inflammatory markers and cultures ordered during the visit, endoscopy and other imaging modalities, requests for consulting services as well as changes in treatment initiated during the visit. We also evaluated outcome parameters such as need for ED visits within a 30 and 90 d period following the RAC visit. These ED visits were categorised based on the fact, whether they were organised by the RAC personnel or initiated by the patient alone and the RAC service was unaware of the event (unplanned ED visits). Hospital admissions or surgery were also registered in the aforementioned period.

To compare resource utilization and healthcare costs we evaluated consecutive IBD patients who presented to the ED at the MUHC but did not have access to the RAC services. These patients were included in the period between January 2018 and January 2019. Data pertaining to patient access, diagnostic procedures and outcomes similar to the above-mentioned was collected during this period. Comparison of healthcare costs was performed using the non-industry cost estimates for diagnostic tests/procedures and medical services, as reimbursed by the RAMQ in Quebec[14]. Average medical cost estimates per patient were calculated for ED visits and RAC visits.

Data was analyzed using SPSS 20.0 software. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate demographic variables, baseline patient characteristics, frequencies of diagnostic procedures, treatment change and outcome parameters. χ2 test was used to calculate differences in frequencies of resource utilization, change in medical therapy or hospitalization events, surgery requirements. Mean (SD) and median (IQR) time to events or length of stay and mean (SD) costs were calculated. A P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Ethics Committee approval was obtained in accordance to ISO protocol, local legal regulations and McGill University Health Center Research Ethics Board guidelines, prior to initiation of this study. All information collected during the course of this study remained confidential to the extent required by law. Data was strictly limited to members of the research team. Authorization to access patient charts was obtained from the Director of Professional Services of the MUHC.

488 patients [41.3% male, Crohn’s disease (CD)/ulcerative colitis (UC) 68.5%/31.5%] who had valid medical reason for contacting the RAC clinic were included during the investigation period (Table 1). For cost- and resource utilization comparison, 135 patients (60.7% male, CD/UC 68.5%/31.5%) who were not followed-up in the MUHC IBD center and were presenting to the ED at the MUHC for symptoms pertaining to a potential IBD flare were included. Detailed patient characteristics data is depicted in Table 1.

| RAC visits (n = 488) | Emergency departmentvisits (n = 135) | |

| CD/UC (n) | 334/154 | 97/38 |

| Men/Women (%) | 41.3/58.7 | 60.7/39.3 |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 39.3 ± 14.8 | 45.2 ± 18.4 |

| CD localization L1/L2/L3/L4 (%) | 25.1/27.9/46.0/1.0 | 18.4/19.4/62.2/- |

| CD behavior B1/B2/B3 (%) | 66.7/17.6/15.7 | 38.8/31.6/29.6 |

| CD perianal (%) | 22.7 | 10.2 |

| UC location E1/E2/E3 (%) | 8.8/30.4/60.8 | -/27.8/72.2 |

| Biological therapy (%) | 60.6 | 42.9 |

| Previous resective surgery (%) | 19.8 | 35.6 |

Amongst all the email/telephone requests obtained during the study period, 85.8% were deemed appropriate for a rapid appointment as per the Urgent IBD Care plan and consequently, these patients were given appointments for a RAC visit. Amongst these total visits, 333 patients (68.2%) were granted an appointment with an IBD specialist gastroenterologist and 86 patients (17.6%) had a visit with a specialised IBD nurse, where the physician was kept notified of the situation. 69 patients (14.1%) had no visit as their request could be managed via email or telephone. The reason for a rapid appointment was potential disease flare in 71.6% of patients presenting for a RAC visit. The median time to a RAC visit with an IBD specialist physician was 2 d (IQR: 0-6 d) following the first point of contact (telephone or email) initiated by the patient.

RAC visits consisted of fast-track evaluation of disease activity using clinical assessment and laboratory markers. Complete blood count and C-reactive protein (CRP) measurements were performed in 90.9%, while fecal calprotectin (FCAL) in 73%, respectively. Stool culture was ordered in 41.9% of patients and Clostridium difficile toxin stool PCR in 43.1%. Colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy was requested in 17.9% and 6.7% of the patients, while only a minority of patients underwent imaging modalities, including 6.0% abdominal computed tomography (CT) and 2.1% magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Other specialist consults were ordered in 9.8% of the cases, which included ED visits/consult initiated during a RAC appointment (Table 2). There was no significant difference between resource utilization and outcomes between patients with Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative colitis (Supplementary Figure 1).

| RAC resource utilization (%)1 | ED resource utilization (%)2 | P value | |

| CRP | 90.9 | 98.5 | NS |

| FCAL | 73 | 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| C. diff stool test | 43.1 | 51.1 | 0.03 |

| Stool Culture | 41.9 | 48.9 | 0.06 |

| TDM | 14.7 | 0.0 | < 0.001 |

| Colonoscopy | 17.9 | 26.7 | 0.005 |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | 6.7 | 14.8 | < 0.001 |

| CT abdominal | 6.0 | 65.7 | < 0.001 |

| MRI | 2.1 | 2.2 | NS |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 11.3 | 3.7 | < 0.001 |

| Gastroenterology consultation | - | 100 | |

| Internal medicine consultation | - | 50.4 | |

| Colorectal surgery consultation | - | 37.8 | |

| Other consults | 9.8 | 9.6 | NS |

The study revealed a change in medical therapy in 54.4% of the cases. 21% of the patients experienced initiation or dose adjustment of systemic steroids, and biologics were started or optimized in 11.9% of cases, respectively (Table 3).

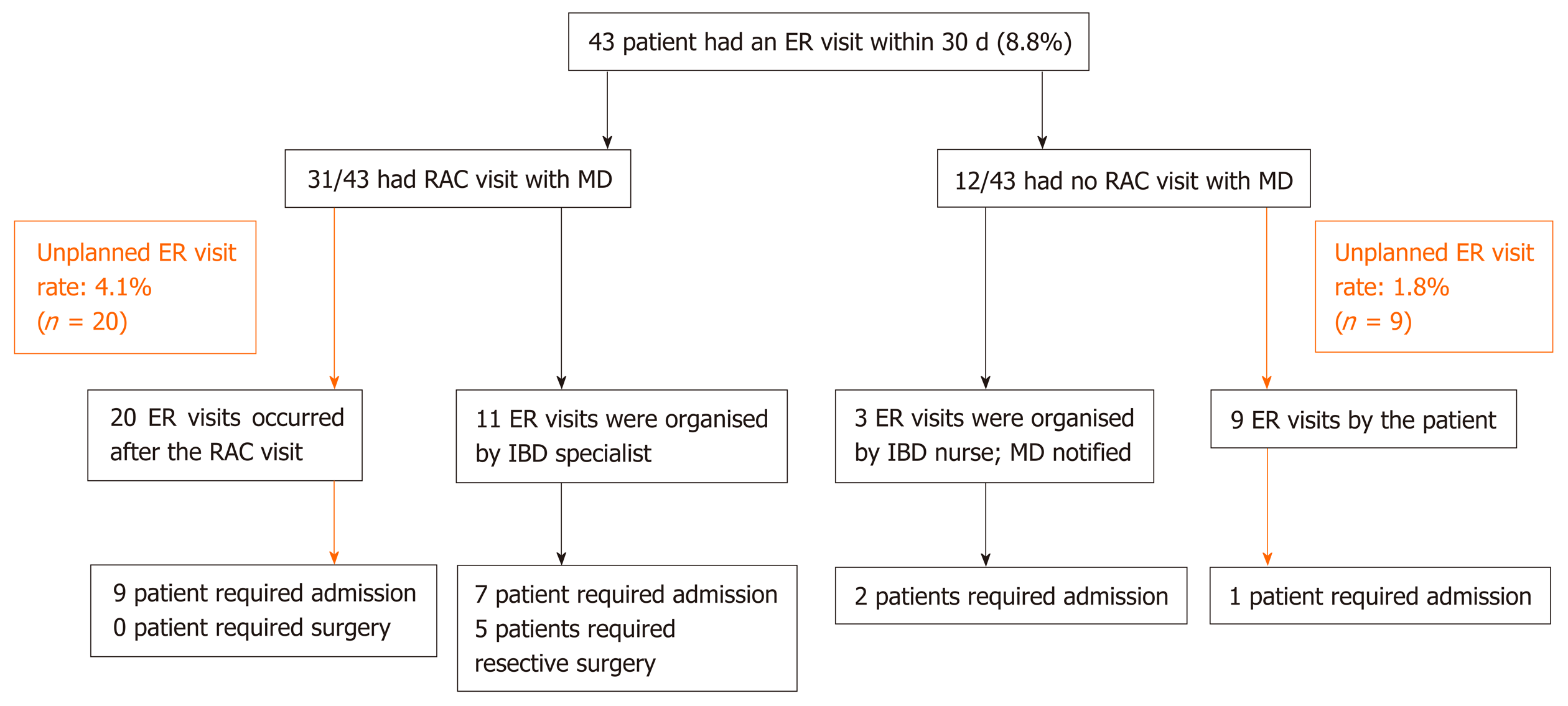

There was an 8.8% (n = 43) rate of ED visits within 30 d and 11.1% rate within 90 d following the initial contact with the RAC services. The overall rate of hospital admissions related to IBD within 30 d following the first contact with the RAC was 4.5% (n = 22). The overall incidence of unplanned ED visits (not initiated by a physician or IBD nurse) was 5.9% (n = 29). Twenty patients presented to the ED following a RAC visit with an IBD specialist and 9 patients were not deemed appropriate for RAC visit with a physician based on complaints. Among patients with unplanned ED visits 10 patients required hospital admission and no patient required surgery. Fourteen patients had ED visits initiated by an IBD specialist or IBD nurse following a RAC visit due to physician concerns during the triage process. Among those, 9 patients required hospital admission and 5 patients underwent surgery. For detailed patient routes see Figure 1.

Amongst the patients assessed in the ED, 98.5% had at least one CRP value drawn and FCAL was measured in 10.4% of cases, significantly less frequent compared to the RAC visits (P < 0.001). 51.1% and 48.9% of patients had a C. difficile stool PCR test and stool cultures, the earlier being significantly more frequent compared to the RAC visits (P = 0.03). A noteworthy 65.7% of patients underwent abdominal CT imaging, significantly more compared to that during the RAC visits (P < 0.001). The frequency of colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy requested were 26.7% and 14.8%, again significantly more compared to the RAC visits (P = 0.005 and P < 0.001). All the patients were assessed by a consultant gastroenterology service. 50.4% were equally seen by internal medicine, 37.8% by colorectal surgery and 9.6% by other consultant services (Table 2).

The overall treatment change rate was similar to that of the RAC cohort, however there was a 42.2% rate of steroid use, significantly more compared to the RAC visits (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Hospital admissions were initiated during an ED visit in 64.4% of the patients, with 5.9% (n = 8) of patients requiring surgery. The mean and median length of hospital stay was 8.4 (SD 9.9) and 5 (IQR: 3-10) d with only 16.9% and 13.5% of patient having a 1-2 or 3 d hospital admission. Additional hospitalisations within 30 d following the ED visit occurred in 8.1% (n = 11) of the patients.

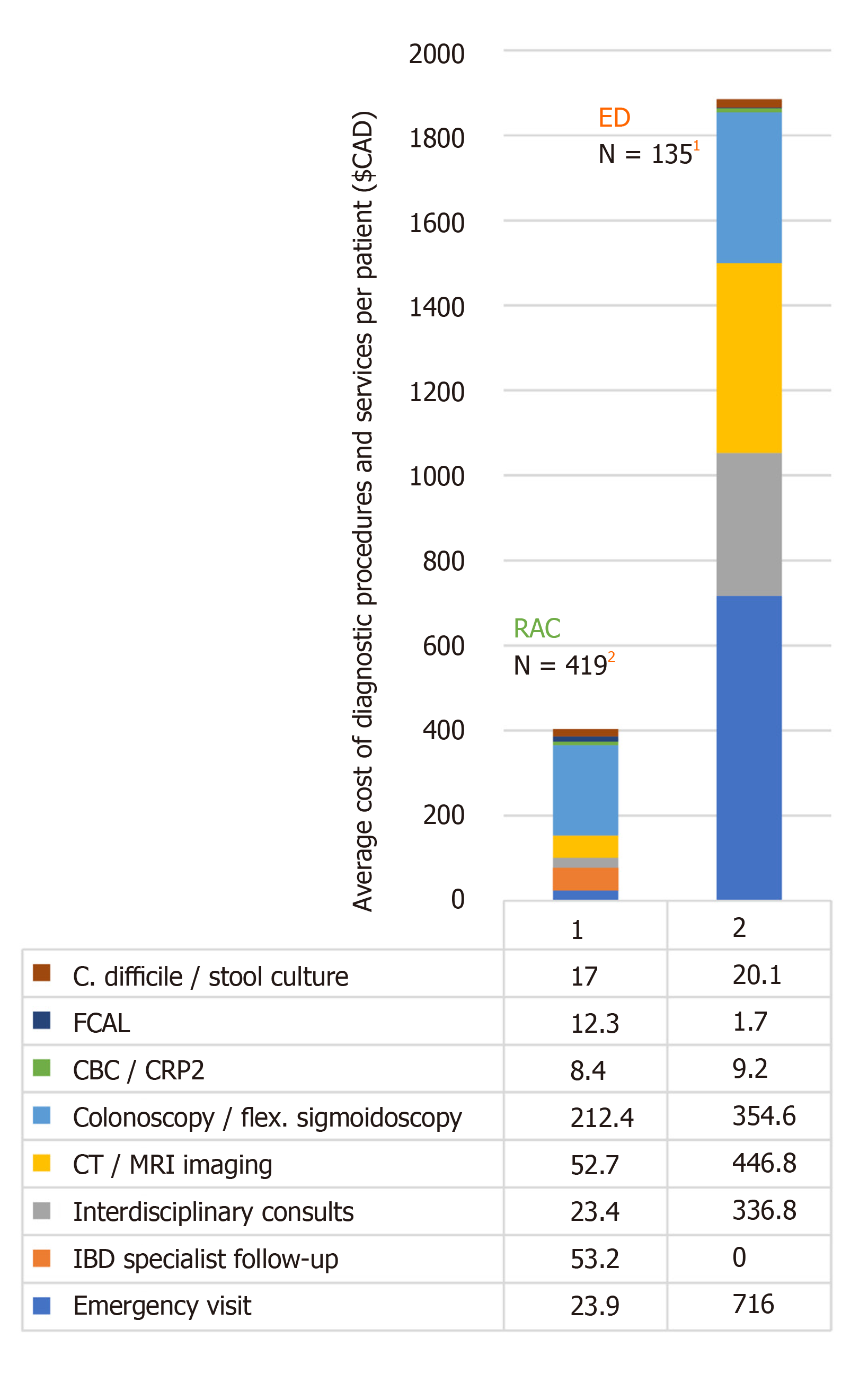

We further analyzed medical expenses comparing the average per-patient costs of resources used for patient assessment by the RAC vs the ED. Amongst the 419 patients seen in the RAC, estimated costs per person based on the diagnostic procedures and services utilized was $403.30 CAD. This is to be compared to ED visits, with an average cost of $1885.50 CAD per patient, with the cost of emergency visit, interdisciplinary consult and imaging being the most contributive to this total (Figure 2). This estimate do not include the expenses of hospital admissions, although 64.4% of the patients presenting at the ED required at least 1 [median 5 (IQR 3-10)] d of hospital admission. This produced an average additional cost of $3143 CAD per patient per day related to hospitalisations (the estimated cost of admitting was $4881 CAD per day). Of note, the average cost related to hospitalizations which incurred during all of the RAC visits was $104.8 CAD per patient per day.

This is the first comprehensive analysis of patient access, resource utilization, costs and outcome measures of a newly implemented formal IBD specific RAC service compared to usual ED visits in IBD patients from a single academic center in North America. The major finding of the present study was that creating a RAC service for IBD patients is associated with quick patient access, optimized and specific use of diagnostic procedures and services, with similar outcome parameters and lower resource utilization compared to regular ED visits for IBD patients.

ED attendance has been reported high for both incident and prevalent cases of IBD. By analyzing trends in ED visits and subsequent hospitalizations in the United States, the frequency of IBD related ED visits increased by 51.8%, from 90846 visits in 2006 to 137946 in 2014 based on the National Emergency Department Sample database[15]. For comparison, all-case ED use in this period increased by 14.8%. Inpatient hos-pitalizations following the ED visits was high, yet showed a decreasing trend for IBD patients (from 64.7% to 52.6%). Of note, the rates of urgent surgery in IBD patients admitted from the ED also decreased from 9.1% of all ED visits in 2006 to 5.6% in 2014. Trends were largely similar for pediatric onset IBD patients, according to a nationwide report on the use of ED resources by children with IBD in the United States. The rate of hospital admission for children was approximately 40% in CD and 60% in UC[16]. In a recent population-based study from Manitoba including 300 incident and 3394 prevalent IBD cases, 76% and 49% of patients attended the ED at least once during the study period of 3 years[3]. Hospitalization rates were reported lower in this study after presentation to the ED, with only 15% of the patients with known IBD and 44% with a new diagnosis of IBD were being admitted to the hospital. Our results show high rates (64%) for overall hospitalization of IBD patients presenting for regular ED department visits, however the rate of surgical intervention was low, only 5.9%. Direct comparison between these rates is difficult because of different methodology and IBD setting (IBD center vs population-based), or other contributing factors (e.g., the availability of IBD specialist gastroenterology consults). Considering all the above, results could suggest that in a significant proportion of cases, IBD care provided in the ED could have been effectively and safely managed in a more cost-optimized outpatient settings, preferably by the attending IBD specialist.

The need for optimized “patient access” and monitoring algorithms for specialized care in acute IBD-related conditions is also expressed by the patients. ED care is associated with a high health care burden (e.g., long waiting hours, assessment and care provided by non-specialized physicians and high costs). Based on a survey from Manitoba, the majority of persons would be receptive to options other than ED visit when experiencing IBD related symptoms: 77% and 75% of the participants expressed to likely use a phone contact with a specialized IBD nurse, or a gastroenterologist, and 71% would use a walk-in gastroenterology clinic service[17]. In a previous study, our group evaluated results from patient satisfaction surveys at the MUHC IBD center, using the “Quality of Care Through the Patient's Eyes - Inflammatory Bowel Disease” questionnaire[9]. Results showed that “accessibility” especially in case of acute situation was one of the lowest rated aspects of perceived quality of care. These findings also strengthen the importance of establishing a new route of patient access to IBD specific care.

Our study is the first to comparatively evaluate the performance of RAC and ED care pathways, including utilization of diagnostic tests and consulting services. Our results confirm that objective and rapid evaluation was performed at the RAC, including high rates of CRP and FCAL testing (frequently coupled with Clostridium difficile and stool cultures), and careful use of fast-track endoscopies in line with a “treat-to-target” framework and objective, timely disease monitoring[5,6]. Cross sectional imaging was reserved for suspicion of complicated disease behavior and/or emergency situations, and mainly for CD patients.

In contrast, diagnostic test and service utilization by the ED was significantly different, including a very high utilization of cross-sectional imaging. More than two thirds of the patients underwent CT imaging who presented to the ED, while in the RAC CT was performed in 6% of the IBD patients. The wide use of abdomino-pelvic CT in ED is of concern for radiation exposure and costs. Yarur et al[18] found in a cross-sectional study that the rate of clinically actionable finding with abdomin-pelvic CT was moderate for CD patients (32.1%) but minimal for UC (12.8%) patients who visited the ED in the United States. For comparison, in the present study, 47.3% of patients underwent CT in the ED even in UC. FCAL test was performed only in 10.4% of the ED visits in the present study. The high frequency of urgent/same day hospitalizations and relatively long in-hospital stay [5 d, (IQR 3-10 d)] by the ED is also an important aspect of excessive resource utilizations.

Of note, 10% of the RAC patients underwent abdominal ultrasound (US) examination as part of their evaluation. US was the preferred method of choice against CT or MRI imaging in patients with the appropriate disease phenotype. Transabdominal US was reported to have comparable overall sensitivity and specificity to MRI and CT imaging in diagnosing ileal CD[19,20]. The evolution of US equipment, growing expertise, rapid access and relatively low costs lead to a growing use of intestinal US in the clinical assessment of IBD patients, especially in countries where the use of abdominal ultrasonography has a traditional role in everyday gastroenterology practice, e.g., Germany, Italy[21]. A recent study showed that point of care US examinations could play a significant role in guiding therapeutic ma-nagement in CD, although the proper characterization of disease specific lesions requires training and expertise[22]. Another study group reported initial experience of a rapid access US imaging clinic in IBD from the United Kingdom, demonstrating that a combined clinic-radiological approach using fast-track US offers the opportunity for urgent treatment changes and more proper triage of follow up appointment scheduling[23].

Our results also confirm that the therapeutic decisions and optimization of medical therapy were significantly different in the case of RAC vs ED visit. Fewer cases of steroid initiation/dose adjustment were performed by IBD specialist physicians in contrast to the ED. In addition, optimization of biologicals and immunosuppressive was more frequent out in RAC settings.

An important outcome parameter is the need for ED visits following a RAC visit, and need for hospital admission and surgery rates within the next 30 or 90 d following the RAC or ED visits. Only 4.1% of patients needed an ED visit following a RAC visit, while the number of those patients who were not granted a RAC visit with a physician and reported to the ED anyway was even less (1.8%). A significant proportion of the ED visits following the RAC appointment reflected ongoing disease activity. Same day hospitalization rates were much higher following a regular ED visit. Hospital admissions in the next 30 d after a RAC visit was low (4.5%), this was also higher after an ED visit (8.1%). The requirement of urgent surgical interventions was also lower in patients presenting for the RAC [1.3% (n = 5) vs 5.9% (n = 8)].

Finally, ED visits - frequently used by IBD patients - are associated with a known economic burden, thus decreasing ED access offers the potential for cost savings. ED visits contribute to approximately 10% of all ambulatory medical care visits in the United States[24,25]. Ballou et al[15] reported that the frequency of IBD-ED visits increased by 51.8% during an 8 year period (2006-2014) in parallel by a 102.5% rise in the per patient costs and a 207.5% increase in the aggregate national cost of IBD-ED visits, based on the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample database from the United States. The mean total charge of a single ED visit for IBD was $4342 in 2014[15]. To our knowledge, our study is the first in the North American region to compare costs and resource utilization between IBD patients seen in a RAC service and those who presented to ED. Based on the RAMQ reimbursement plan data for procedures and services, and the number of patients included in our observation period we estimated the per-patient costs of one RAC visit at $403.30 CAD, whereas the per-patient cost incurred during an ED averaged at $1885.50 CAD. The main cost drivers of the ED visit were emergency service facility fees ($716 CAD per patient), interdisciplinary consults ($337 CAD per patient) and cross sectional CT imaging ($447 CAD per patient). These estimates, however, do not include inpatient costs. Of note, > 60% of patients attending an ED visit had a median 5 night of hospital admission, which adds $15715 CAD ($3143 CAD/d) additional cost per patient. Implementation of a RAC service in IBD would thus alleviate an already saturated acute care pathway and reduce health care costs, as similar outcomes are achievable with an optimized resource utilization.

Nevertheless, the concept of RAC may be less transmissible to community gastroenterology services given differences in IBD patient load and the potential lack of resources, however this strategy was shown clearly beneficial in our high-volume academic tertiary care IBD center. There are other examples of alternative follow-up options/rapid access pathways for IBD patients. A pediatric study by Dykes et al[26] showed that increasing the availability of IBD specialists and specialized nurses via telemedicine (e-visit/e-messaging model) can also decrease the frequency of IBD related ED visits. Another large-scale quality improvement project at a tertiary IBD centre in the UK reported results on the stratification of adult IBD outpatients by risk and disease activity to achieve a more optimal setting for outpatient monitoring. Patients in long-standing remission with a low risk of complications were transferred to a nurse-led telephone clinic monitoring service, with high non-inferior satisfaction rates being reported compared with existing face-to-face clinics. In parallel, the authors reported positive satisfaction results in establishing IBD referral hotlines and RACs, providing a responsive service for patients requiring urgent specialist attention. The median waiting time to a RAC visit was 6.5 d[27].

The strengths of the present study include the single center design in a specialized tertiary care IBD center staffed with specialized IBD clinicians leading to harmonized care and less variation in treatment decisions, and consecutive, prospective patient inclusion with a large cohort size. The study provides a comprehensive and comparative analysis of two acute-care management pathways for IBD patients, including evaluation of patient access, resource utilization, costs and disease outcome parameters. A limitation to our study is that the IBD patient populations attending the RAC and ED services in real-life setting are not fully similar. The two populations had differences in disease characteristics, pointing to the more complex phenotype of the ED cohort. Providing easy access could have potentially boosted patient contact to the RAC clinic, and not all patients would have presented at ED. This is a potential confounder we are not able to fully control for. It may be hypothesized though, that the majority of those patients, who were seen in the RAC clinic would have alternatively presented to the ER (only 14.1% of the requests were deemed inappropriate as triaged by an IBD specialist or nurse). We believe that the differences in resource utilization, treatment decisions, outcomes and costs between the RAC and the ED are straightforward and show a clear benefit of this alterative rapid care pathway for IBD. Thus, the RAC may have accounted for approximately two thirds of potential ED IBD visits in 2018, where RAC and ED visits were monitored prospectively and in parallel. Of note, we could not calculate the exact change in the ED exposure by IBD patients before and after the creation of the RAC, since we did not track ED IBD visit counts before the initiation of the RAC.

In conclusion, results from the present study demonstrate that implementation of a RAC care pathway improved healthcare delivery by facilitating easier access, optimizing resource utilization for patient evaluation and treatment decisions to IBD specific medical care in urgent situations, thus preventing unnecessary ED visits. Patients, who underwent fast-track evaluation by an IBD specialist had low rates of further ED visits and hospital admissions. In addition, RAC pathway was associated with a significant cost reduction compared to ED services.

Emergency department (ED) attendance in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients put significant burden on the healthcare system.

We theorize that a large proportion of IBD patients presenting with urgent IBD specific complaints could potentially be managed in alternative care settings, thus avoiding unnecessary ED visits.

To report a comprehensive analysis of patient access and resource utilization after the implementation of the new rapid access clinic (RAC) service at a tertiary IBD center, compared to usual ED visits in IBD patients.

Patient access, resource utilization and outcome parameters were collected from consecutive patients contacting the RAC in a two year period. Comparative analysis of resource utilization and healthcare costs were carried out evaluating ED visits of IBD patients with no access to RAC services.

Creating a RAC for IBD patients is associated with quick patient access, optimized and specific use of diagnostic procedures and services, with similar outcome parameters and lower resource utilization and overall costs compared to regular ED visits for IBD patients.

Implementation of a RAC facilitated easier access to IBD specific medical care, with optimized resource utilization and helped avoiding potential ED visits and subsequent hospitalisations.

A RAC is ideal for providing IBD specific medical care in urgent situations, reducing burden to both the healthcare system and patients.

| 1. | Le Berre C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Danese S, Singh S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease Have Similar Burden and Goals for Treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:14-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Danese S, Semeraro S, Papa A, Roberto I, Scaldaferri F, Fedeli G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7227-7236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Nugent Z, Singh H, Targownik LE, Strome T, Snider C, Bernstein CN. Predictors of Emergency Department Use by Persons with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Population-based Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2907-2916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997-2007. JAMA. 2010;304:664-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, D'Haens G, Dotan I, Dubinsky M, Feagan B, Fiorino G, Gearry R, Krishnareddy S, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV, Marteau P, Munkholm P, Murdoch TB, Ordás I, Panaccione R, Riddell RH, Ruel J, Rubin DT, Samaan M, Siegel CA, Silverberg MS, Stoker J, Schreiber S, Travis S, Van Assche G, Danese S, Panes J, Bouguen G, O'Donnell S, Pariente B, Winer S, Hanauer S, Colombel JF. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 1470] [Article Influence: 133.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (116)] |

| 6. | Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, Lukas M, Baert F, Vaňásek T, Danalioglu A, Novacek G, Armuzzi A, Hébuterne X, Travis S, Danese S, Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Hommes D, Schreiber S, Neimark E, Huang B, Zhou Q, Mendez P, Petersson J, Wallace K, Robinson AM, Thakkar RB, D'Haens G. Effect of tight control management on Crohn's disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;390:2779-2789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 714] [Article Influence: 79.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Bitton A, Vutcovici M, Lytvyak E, Kachan N, Bressler B, Jones J, Lakatos PL, Sewitch M, El-Matary W, Melmed G, Nguyen G; QI consensus group; Promoting Access and Care through Centers of Excellence-PACE program). Selection of Quality Indicators in IBD: Integrating Physician and Patient Perspectives. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vasudevan A, Arachchi A, van Langenberg DR. Assessing patient satisfaction in inflammatory bowel disease using the QUOTE-IBD survey: a small step for clinicians, a potentially large step for improving quality of care. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e367-e374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gonczi L, Kurti Z, Verdon C, Reinglas J, Kohen R, Morin I, Chavez K, Bessissow T, Afif W, Wild G, Seidman E, Bitton A, Lakatos PL. Perceived Quality of Care is Associated with Disease Activity, Quality of Life, Work Productivity, and Gender, but not Disease Phenotype: A Prospective Study in a High-volume IBD Centre. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1138-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bond K, Ospina MB, Blitz S, Afilalo M, Campbell SG, Bullard M, Innes G, Holroyd B, Curry G, Schull M, Rowe BH. Frequency, determinants and impact of overcrowding in emergency departments in Canada: a national survey. Healthc Q. 2007;10:32-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Newlyn N, McGrath RT, Fulcher GR. Evaluation of the performance and outcomes for the first year of a diabetes rapid access clinic. Med J Aust. 2016;205:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Klimis H, Thiagalingam A, Altman M, Atkins E, Figtree G, Lowe H, Cheung NW, Kovoor P, Denniss AR, Chow CK. Rapid-access cardiology services: can these reduce the burden of acute chest pain on Australian and New Zealand health services? Intern Med J. 2017;47:986-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Reinglas J, Restellini S, Gonczi L, Kurti Z, Verdon C, Nene S, Kohen R, Afif W, Bessissow T, Wild G, Seidman E, Bitton A, Lakatos PL. Harmonization of quality of care in an IBD center impacts disease outcomes: Importance of structure, process indicators and rapid access clinic. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:340-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Répertoire Québécois et système de mesure des procedures de biologie médicale 2018-2019. Direction de la biovigilance et de la biologie médicale Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Available from: http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2017/17-922-06W.pdf. |

| 15. | Ballou S, Hirsch W, Singh P, Rangan V, Nee J, Iturrino J, Sommers T, Zubiago J, Sengupta N, Bollom A, Jones M, Moss AC, Flier SN, Cheifetz AS, Lembo A. Emergency department utilisation for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States from 2006 to 2014. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:913-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pant C, Deshpande A, Fraga-Lovejoy C, O'Connor J, Gilroy R, Olyaee M. Emergency Department Visits Related to Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results From Nationwide Emergency Department Sample. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:282-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bernstein MT, Walker JR, Chhibba T, Ivekovic M, Singh H, Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Health Care Services in IBD: Factors Associated with Service Utilization and Preferences for Service Options for Routine and Urgent Care. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1461-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yarur AJ, Mandalia AB, Dauer RM, Czul F, Deshpande AR, Kerman DH, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. Predictive factors for clinically actionable computed tomography findings in inflammatory bowel disease patients seen in the emergency department with acute gastrointestinal symptoms. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:504-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Panés J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, García-Sánchez V, Gisbert JP, Martínez de Guereñu B, Mendoza JL, Paredes JM, Quiroga S, Ripollés T, Rimola J. Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:125-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cullen GJ, Daperno M, Kucharzik T, Rieder F, Almer S, Armuzzi A, Harbord M, Langhorst J, Sans M, Chowers Y, Fiorino G, Juillerat P, Mantzaris GJ, Rizzello F, Vavricka S, Gionchetti P; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1585] [Cited by in RCA: 1510] [Article Influence: 167.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kucharzik T, Wittig BM, Helwig U, Börner N, Rössler A, Rath S, Maaser C; TRUST study group. Use of Intestinal Ultrasound to Monitor Crohn's Disease Activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:535-542.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Novak K, Tanyingoh D, Petersen F, Kucharzik T, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Kaplan GG, Wilson A, Kannengiesser K, Maaser C. Clinic-based Point of Care Transabdominal Ultrasound for Monitoring Crohn's Disease: Impact on Clinical Decision Making. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:795-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Grunshaw N, Egbuonu F, Harrison W, DaviesInitial A. Initial experience of a rapid access ultrasound imaging clinic in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2018;67 Suppl 1:A1-A304. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Clancy CM. Emergency departments in crisis: opportunities for research. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:xiii-xixx. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, Ollendorf DA, Sandler RS, Galanko JA, Finkelstein JA. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907-1913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dykes D, Williams E, Margolis P, Ruschman J, Bick J, Saeed S, Opipari L. Improving pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) follow-up. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fofaria RK, Barber S, Adeleke Y, Woodcock T, Kamperidis N, Mohamed A, Misra R, Shah A, Bailey-Fee S, Bluston H, Robinson D, Tyrrell T, Arebi N. Stratification of inflammatory bowel disease outpatients by disease activity and risk of complications to guide out-of-hospital monitoring: a patient-centred quality improvement project. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P-Reviewer: Bassotti G, Dai YC S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL