Published online Mar 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i10.1259

Peer-review started: January 14, 2019

First decision: January 23, 2019

Revised: January 29, 2019

Accepted: January 30, 2019

Article in press: January 30, 2019

Published online: March 14, 2019

Processing time: 61 Days and 16.9 Hours

Local endoscopic resection is an effective method for the treatment of small rectal carcinoid tumors, but remnant tumor at the margin after resection remains to be an issue.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of resection of small rectal carcinoid tumors by endoloop ligation after cap-endoscopic mucosal resection (LC-EMR) using a transparent cap.

Thirty-four patients with rectal carcinoid tumors of less than 10 mm in diameter were treated by LC-EMR (n = 22) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) (n = 12) between January 2016 and December 2017. Demographic data, complete resection rates, pathologically complete resection rates, operation duration, and postoperative complications were collected. All cases were followed for 6 to 30 mo.

A total of 22 LC-EMR cases and 12 ESD cases were enrolled. The average age was 48.18 ± 12.31 and 46.17 ± 12.57 years old, and the tumor size was 7.23 ± 1.63 mm and 7.50 ± 1.38 mm, respectively, for the LC-EMR and ESD groups. Resection time in the ESD group was longer than that in the LC-EMR group (15.67 ± 2.15 min vs 5.91 ± 0.87 min; P < 0.001). All lesions were completely resected at one time. No perforation or delayed bleeding was observed in either group. Pathologically complete resection (P-CR) rate was 86.36% (19/22) and 91.67% (11/12) in the LC-EMR and ESD groups (P = 0.646), respectively. Two of the three cases with a positive margin in the LC-EMR group received transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) and tumor cells were not identified in the postoperative specimens. The other case with a positive margin chose follow-up without further operation. One case with remnant tumor after ESD received further local ligation treatment. Neither local recurrence nor lymph node metastasis was found during the follow-up period.

LC-EMR appears to be an efficient and simple method for the treatment of small rectal carcinoid tumors, which can effectively avoid margin remnant tumors.

Core tip: Rectal carcinoid is a common clinical submucosal tumor of the digestive tract. Small rectal carcinoids rarely have lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis, and local endoscopic resection is an effective method for the treatment of small rectal carcinoid tumors, but remnant tumor at the margin after resection remains to be an issue. Endoloop ligation after cap-endoscopic mucosal resection using a transparent cap appears to be an efficient and simple method for the treatment of small rectal carcinoid tumors, which can effectively avoid margin remnant tumors.

- Citation: Zhang DG, Luo S, Xiong F, Xu ZL, Li YX, Yao J, Wang LS. Endoloop ligation after endoscopic mucosal resection using a transparent cap: A novel method to treat small rectal carcinoid tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(10): 1259-1265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i10/1259.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i10.1259

Rectal carcinoid tumor is one of the most common neuroendocrine tumors in the digestive tract. Most of them have no clinical symptoms and are unintentionally discovered by colonoscopy[1]. The risk of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis for rectal carcinoid with a diameter less than 10 mm is small. Thus, microscopic local excision is currently the commonly used method for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors[2]. However, because most of these tumors are located in the submucosal layer of the rectal wall in the lower rectum[3], traditional endoscopic resection methods do not ensure complete removal of the tumor, leading to a positive margin of resection, which often requires further surgical intervention. Recently, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is considered to be an effective method for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors, but its technical requirements and the associated complications are relatively high[4]. Nylon endoloop ligation method has been proved to be an effective treatment for submucosal lesions of the upper digestive tract. For subepithelial tumors derived from the muscularis propria, the nylon endoloop used after resection can automatically fall off to achieve “let it go” effect[5,6]. Few studies have evaluated the use of nylon ligation in the treatment of rectal carcinoma after endoscopic resection of rectal carcinoid tumor. Therefore, this study compared the efficacy of ESD and ligation after cap-endoscopic mucosal resection (LC-EMR) in the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors by retrospective analysis. We also evaluated the advantages of LC-EMR in the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors.

We retrospectively analyzed the cases diagnosed as rectal carcinoid tumors and treated by LC-EMR or ESD in the gastroenterology unit of Shenzhen People’s Hospital between January 2016 and December 2017. The studied cohort was selected based on the following criteria: (1) rectal carcinoid tumors confirmed by histological diagnosis; (2) lesions ≤ 10 mm by EUS; (3) carcinoid syndrome without symptoms; and (4) no pararectal lymph node or distant metastasis as determined by pelvic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) before the procedure. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital and all patients gave their informed consent before the procedures. “Complete resection” refers to the absence of any visible residual tumor under endoscopy after tumor resection. A pathologically complete resection (P-CR) was defined as an en bloc resection with no lateral or deep margins of the tumor.

LC-EMR procedure: A wide (14.9 mm-diameter), soft, straight, transparent cap with an inside rim (D-201-11802, Olympus) was fitted onto the tip of a standard single-channel endoscope (GIF-260, Olympus). A ligating device with a 20mm maximum detachable nylon loop (MAJ-339, Olympus) was inserted into the accessory channel of the endoscope. Other devices include Dual knife, injection needles, snares, and hot biopsy forceps from Olympus, as well as a high-frequency generator (ICC-200, ERBE).

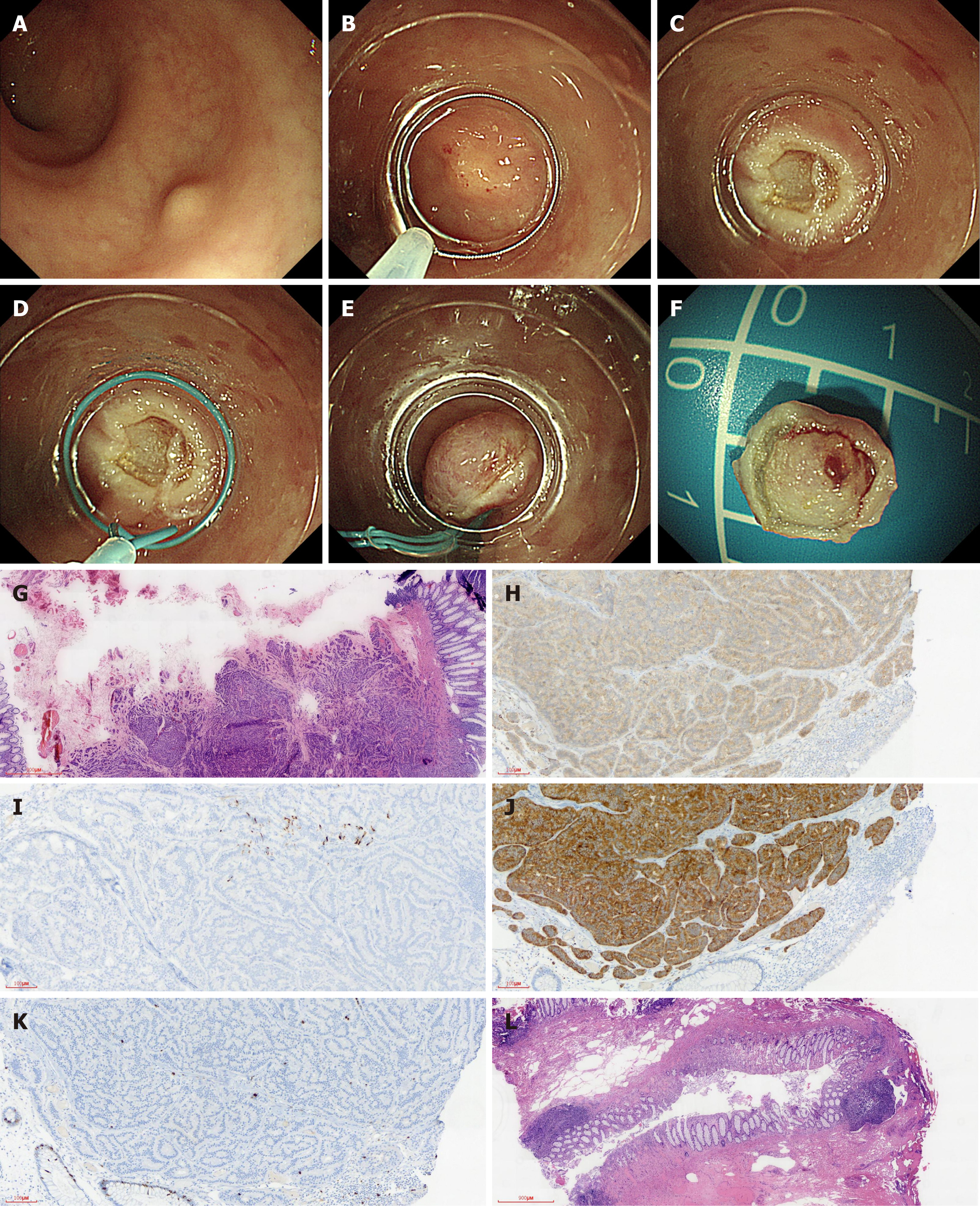

There were four steps in LC-EMR. The first step was to loop the crescent-shaped snare around the rim of the transparent cap. The second step was aspiration and ligation of the lesion with a high-frequency electrosurgical snare. The third step was the resection of the lesion via electrocautery. The fourth step was the aspiration of the lesion into the ligator device, followed by deployment of the endoloop (Figure 1A-F).

ESD procedure: ESD was performed using a single-channel endoscope with a short transparent cap that was attached to the tip of endoscope. First, the submucosal solution was injected and the circumferential mucosa of the lesion was incised using a dual knife. Then, according to the method reported in the literature[5], circumferential incision, submucosal dissection, and treatment of wounds were performed. All procedures were conducted by two skilled endoscopists (Zhang DG and Wang LS). Pathological examination included identification of histopathologic type, invasion depth, lateral and vertical resection margins, lymphovascular involvement, as well as immunohistochemical testing, and grades were determined by mitotic count and Ki-67 labeling index. All patients were routinely fasted for 1 d after surgery and discharged if there were no any significant complications.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc, United States). Continuous variables are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical data are showed as number (n) and percentage (%).

A total of 34 patients including 24 males and 10 females with an average of 19-79 (47.47 ± 12.25) years participated in the study. The LC-EMR group had 22 cases and the ESD group had 12 cases. The mean ages of the ESD and LC-EMR groups were 48.18 ± 12.31 and 46.17 ± 12.57, respectively. Tumor size of the ESD and LC-EMR groups was 7.23 ± 1.63 mm and 7.50 ± 1.38 mm, respectively. The resection time (including resection and closure time) of the ESD group was longer than that of the LC-EMR group (15.67 ± 2.15 min vs 5.91 ± 0.87 min, P < 0.001). All lesions had one-time complete resection. No perforation or delayed bleeding was observed in either group. P-CR was 86.36% (19/22) and 91.67% (11/12) in the LC-EMR group and ESD group (P = 0.646), respectively. Pathology diagnosis was confirmed as G1. Two of the three cases with a positive margin in the LC-EMR group received transanal rectal tumor resection and tumor cells were not identified in the postoperative specimens (Figure 1G-L). The other case with a positive margin chose follow-up without further operation. One case with remnant tumor after ESD received further local ligation treatment. Generally, colonoscopy was performed and postoperative scar and recurrence were observed 6 months after resection, and then at an interval of 1 to 2 years. For the two patients with remnant tumor after LC-EMR or ESD who did not choose further surgery, colonoscopy was performed and postoperative scar and recurrence were observed 3 mo after resection, and then repeat colonoscopy and abdominal CT scan were performed at an interval of 1 year. Neither local recurrence nor lymph node metastasis was found during the follow-up period (Tables 1-3).

| LC-EMR (n = 22) | ESD (n = 12) | P-value | |

| Age (yr) | 48.18 ± 12.31 | 46.17 ± 12.57 | 0.907 |

| Sex (M/F) | 17/5 | 7/5 | 0.016 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 7.23 ± 1.63 | 7.50 ± 1.38 | 0.531 |

| Distance from anal verge (cm) | 6.27 ± 0.98 | 6.75 ± 1.48 | 0.281 |

| LC-EMR (n = 22) | ESD (n = 12) | P-value | |

| Endoscopic complete resection | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 1.000 |

| Pathologically complete resection | 19 (86.36) | 11 (91.67) | 0.646 |

| Histological margin involvement | |||

| Lateral | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Vertical | 3 (13.64) | 1 (8.33) | 0.646 |

| Resection time (min, ± SD) | 5.91 ± 0.87 | 15.67 ± 2.15 | 0.001 |

| Recurrence follow-up | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| LC-EMR (n = 3) | ESD (n = 1) | |

| TEM (n) | 2 | 0 |

| Religation (n) | 0 | 1 |

| Histological after surgery or endoscopy | Negative | Negative |

| Recurrence follow-up (n) | 0 | 0 |

Rectal carcinoid tumors were restricted to the submucosa and had a lower risk of metastasis when the tumor was less than 10 mm in diameter without lymphoid or vascular infiltration[2,4]. Local or endoscopic excision is considered curative for these tumors[7]. However, it is difficult to completely resect carcinoid tumors of the rectum by conventional EMR, because about 75% of the tumors have extended into the submucosa[8]. Compared with EMR, ESD is considered a better method for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors, but it requires higher technical means and is relatively time consuming and has more complications[7]. Other improved EMR methods, such as endoscopic double snare polypectomy (EDSP)[9], EMR with a ligation device (ESMR-L)[10], EMR with double ligation (ESMR-DL)[11], or EMR after circumferential pre-cutting (EMR-P)[12], can remove deeper layers of the tumor without significant complications for small rectal carcinoids. However, the edge remnant is always the problem that needs to be solved for local endoscopic resection. Recent studies have shown that the treatment method is the only independent factor affecting the P-CR rate of rectal carcinoid tumors. Wang et al[13] compared the therapeutic effects of EMR-C (30 cases) and ESD (25 cases) for rectal carcinoids < 16 mm in diameter, and the results showed that nine cases in the EMR-C group had positive basal margins. During the 18 mo of follow-up, five cases in the EMR-C group had local recurrence, while no recurrence was found in the ESD group. Chen et al[14] conducted a retrospective study of 66 patients with rectal carcinoids less than 15 mm in diameter, and the results showed that P-CR was 96.43% and 93.94% for ESD and circumferential incision before EMR (CI-EMR) groups, respectively. For smaller rectal carcinoid tumors, if residual lesions appear after endoscopic resection, more of them were vertical resection margin positive. Theoretically, ligation after endoscopic resection can reduce the incidence of residual tumor, so this study selected LC-EMR and ESD for comparison and further evaluated the effect of LC-EMR in the treatment of small rectal carcinoid.

Our study showed that although there were three positive margins in the LC-EMR group and two of them underwent further surgical local resection, no tumor invasion was found in the surgical specimens. We speculated that this is because local endoloop ligation after EMR-C led to ischemic necrosis, which further achieved the effect of clearing local lesions, similar to the effect of “let it go” in the treatment of SET by endoloop as reported in the previous literature[6]. This might also be the reason that the other LC-EMR patient who chose follow-up did not have recurrence. Compared to ESD, LC-EMR is easier and less time consuming. Furthermore, endoloop ligation after EMR-C helps prevent wound bleeding and seal wounds.

Compared with band ligation, endoloop ligation can achieve more robust ligation even if there is local scarring[15]. Another ESD patient with a positive margin refused further surgery. In spite of wound fibrosis, we chose to perform local endoloop ligation 1 wk after resection. In the follow-up period, no tumor recurrence or metastasis was found, and no tumor cells were found in the local biopsy at 3 mo after resection.

The study had some limitations. First, this study is a single-center retrospective study with limited sample size. In addition, considering that rectal carcinoid is a slow-growing tumor, long-term follow-up is necessary to determine the efficacy of LC-EMR. However, LC-EMR appears to be an efficient and simple method for the treatment for small rectal carcinoid tumors less than 10 mm, which can effectively prevent remnant tumors at the resection margin, especially in case of absence of ESD availability.

Rectal carcinoid tumor is a clinically common submucosal tumor of the digestive tract. Lymph node metastasis risk of rectal carcinoid tumors less than 1 cm is low. Endoscopic local resection is currently the main treatment method, of which endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is the first choice. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is also a commonly used treatment method for digestive tract mucosal lesions, with low technical requirements and relatively easy to grasp. Previous studies have shown that EMR also has a good effect on rectal carcinoids, but there is a residual risk of basal tumors, even with improved EMR (such as EMR-cap, EMR-P, C-EMR and so on). Therefore, it is of certain clinical value to explore a simple and effective method to treat small rectal carcinoids on the basis of EMR.

This study aimed to explore a simple and effective endoscopic resection method for the treatment of small rectal carcinoids, especially when ESD is not available.

The clinical application of ligation assisted endoscopic resection is extensive, especially for gastrointestinal submucosal tumors, and even the tumors less than 2 cm derived from the muscularis propria also can achieve satisfactory results. For some submucosal tumors that may have residual tumor in the basal part after endoscopic resection, the ligation method after endoscopic resection can lead to the final ischemic necrosis of the residual tumor and achieve the purpose of complete resection. The purpose of this study was to explore the efficacy of transparent cap assisted endoscopic mucosal resection combined with postoperative endoloop ligation in the treatment of rectal carcinoids.

This study retrospectively analyzed the cases diagnosed as rectal carcinoid tumors and treated by ligation after cap (LC)-EMR or ESD in the gastroenterology unit of Shenzhen People’s Hospital between January 2016 and Decemeber 2017. Patients' demographic data, the complete resection rates, operation duration, and postoperative complications were collected.

A total of 34 patients including 24 males and 10 females with an average of 19-79 (47.47 ± 12.25) years participated in the study. The mean ages, tumor size, resection time, and pathologically complete resection (P-CR) rates of the ESD (n = 12) and LC-EMR (n = 22) groups were 48.18 ± 12.31 years vs 46.17 ± 12.57 years, 7.23 ± 1.63 mm vs 7.50 ± 1.38 mm, 15.67 ± 2.15 min vs 5.91 ± 0.87 min, and 91.67% (11/12) vs 86.36% (19/22), respectively. No perforation or delayed bleeding was observed in either group. Pathology diagnosis was confirmed as G1. Two of the three cases with a positive margin in the LC-EMR group received transanal rectal tumor resection and tumor cells were not identified in the postoperative specimens. The other case with a positive margin chose follow-up without further operation. One case with remnant tumor after ESD received further local ligation treatment. Neither local recurrence nor lymph node metastasis was found during the follow-up period. Both LC-EMR and ESD were effective methods to treat small rectal carcinoid tumors.

LC-EMR appears to be an efficient and simple method for the treatment for small rectal carcinoid tumors less than 10 mm, especially when ESD is not available. LC-EMR can effectively prevent remnant tumors at the resection margin. Considering rectal carcinoid is a slow-growing tumor, long-term follow-up is necessary to determine the long- term efficacy of LC-EMR.

To avoid local tumor residue after endoscopic resection, it is necessary to perform postoperative prophylactic endoloop ligation, even after ESD.

| 1. | Koura AN, Giacco GG, Curley SA, Skibber JM, Feig BW, Ellis LM. Carcinoid tumors of the rectum: effect of size, histopathology, and surgical treatment on metastasis free survival. Cancer. 1997;79:1294-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shields CJ, Tiret E, Winter DC; International Rectal Carcinoid Study Group. Carcinoid tumors of the rectum: a multi-institutional international collaboration. Ann Surg. 2010;252:750-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yoshikane H, Goto H, Niwa Y, Matsui M, Ohashi S, Suzuki T, Hamajima E, Hayakawa T. Endoscopic resection of small duodenal carcinoid tumors with strip biopsy technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:466-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee DS, Jeon SW, Park SY, Jung MK, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK. The feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors: comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2010;42:647-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang D, Lin Q, Shi R, Wang L, Yao J, Tian Y. Ligation-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection with apical mucosal incision to treat gastric subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria. Endoscopy. 2018;50:1180-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yague AS, Shah JN, Nguyentang T, Soetikno R, Binmoeller KF. Simplified treatment of gastric GISTs by endolooping without resection: “loop-and-let-go”. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB174-AB175. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Qin XY, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Chen WF, Ma LL, Zhang YQ, Qin WZ, Cai MY, Ji Y. Advantages of endoscopic submucosal dissection with needle-knife over endoscopic mucosal resection for small rectal carcinoid tumors: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2607-2612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Matsumoto T, Iida M, Suekane H, Tominaga M, Yao T, Fujishima M. Endoscopic ultrasonography in rectal carcinoid tumors: contribution to selection of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:539-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koyama N, Yoshida H, Nihei M, Sakonji M, Wachi E. Endoscopic Resection of Rectal Carcinoids Using Double Snare Polypectomy Technique. Dig Endosc. 1998;10:42-45. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ono A, Fujii T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Lee DT, Gotoda T, Saito D. Endoscopic submucosal resection of rectal carcinoid tumors with a ligation device. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:583-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moon JH, Kim JH, Park CH, Jung JO, Shin WG, Kim JP, Kim KO, Hahn T, Yoo KS, Park SH, Park CK. Endoscopic submucosal resection with double ligation technique for treatment of small rectal carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2006;38:511-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee HJ, Kim SB, Shin CM, Seo AY, Lee DH, Kim N, Park YS, Yoon H. A comparison of endoscopic treatments in rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3491-3498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang X, Xiang L, Li A, Han Z, Li Y, Wang Y, Guo Y, Zuang K, Yan Q, Zhong J, Xiong J, Yang H, Liu S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors 7-16 mm in diameter. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:375-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen R, Liu X, Sun S, Wang S, Ge N, Wang G, Guo J. Comparison of Endoscopic Mucosal Resection With Circumferential Incision and Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Rectal Carcinoid Tumor. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:e56-e61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang D, Shi R, Yao J, Zhang R, Xu Z, Wang L. Treatment of massive esophageal variceal bleeding by Sengstaken-Blackmore tube compression and intensive endoscopic detachable mini- loop ligation: a retrospective study in 83 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2015;62:77-81. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P- Reviewer: Chiba H, Eleftheriadis NP, Sato Y S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Yin SY