Published online Apr 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i16.1803

Peer-review started: February 26, 2018

First decision: March 9, 2018

Revised: March 12, 2018

Accepted: March 25, 2018

Article in press: March 25, 2018

Published online: April 28, 2018

Processing time: 60 Days and 4.1 Hours

To compare the cannulation success, biochemical profile, and complications of the papillary fistulotomy technique vs catheter and guidewire standard access.

From July 2010 to May 2017, patients were prospectively randomized into two groups: Cannulation with a catheter and guidewire (Group I) and papillary fistulotomy (Group II). Amylase, lipase and C-reactive protein at T0, as well as 12 h and 24 h after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and complications (pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation) were recorded.

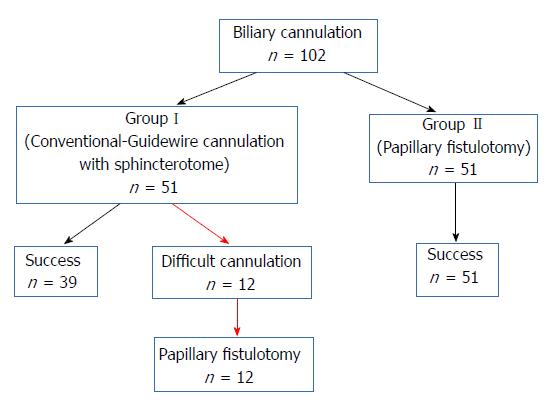

We included 102 patients (66 females and 36 males, mean age 59.11 ± 18.7 years). Group I and Group II had 51 patients each. The successful cannulation rates were 76.5% and 100%, respectively (P = 0.0002). Twelve patients (23.5%) in Group I had a difficult cannulation and underwent fistulotomy, which led to successful secondary biliary access (Failure Group). The complication rate was 13.7% (2 perforations and 5 mild pancreatitis) vs 2.0% (1 patient with perforation and pancreatitis) in Groups I and II, respectively (P = 0.0597).

Papillary fistulotomy was more effective than guidewire cannulation, and it was associated with a lower profile of amylase and lipase. Complications were similar in both groups.

Core tip: Biliary cannulation is the first step of therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and can determine several complications. There are small numbers of papers regarding comparison between conventional cannulation vs fistulotomy. Our study is a well-designed approach in its matter. In fact, we compare the cannulation success, biochemical profile and complications of the papillary fistulotomy technique versus catheter and guidewire standard access. Papillary fistulotomy was more effective than guidewire cannulation, and it was associated with a lower profile of amylase and lipase, as the routine endoscopic access to the biliary tree, including difficult cases. Complications were similar in both groups.

- Citation: Furuya CK, Sakai P, Marinho FRT, Otoch JP, Cheng S, Prudencio LL, de Moura EGH, Artifon ELA. Papillary fistulotomy vs conventional cannulation for endoscopic biliary access: A prospective randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(16): 1803-1811

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i16/1803.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i16.1803

Biliary tract cannulation is the critical step in diagnosis and treatment of biliopancreatic diseases during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Catheter introduction through the papillary ostium fails in 5% to 20% of the patients[1,2]. Several alternatives can be used for difficult cases, such as double-guidewire, pancreatic stent, rendezvous, precut papillotomy, transpancreatic sphincterotomy and papillary fistulotomy (PF) techniques. Acute pancreatitis after ERCP is the most feared complication. It is also one of the most frequent, with an incidence of 1% up to 10% or more, and a mortality of 0.1%-1%[3].

Selective cannulation of the biliary tract, thereby avoiding the pancreatic duct, can curb the mechanisms that trigger pancreatitis, and therefore prevent its occurrence. The precut sphincterotomy has been identified as an independent risk factor of postERCP pancreatitis (PEP). It is unclear whether prolonged cannulation attempts, or precut incisions are to blame. Studies suggest that an early precut is a protective factor, compared to persistent attempts at cannulation[4,5]. However, all protocols that found a lower risk of PEP with a precut technique were performed at specialized centers, and the use of pancreatic stents was limited and inconsistent.

There are few investigations in which the precut and PF techniques were initially employed, to access the biliary tract[6-8]. The PF technique is based on accessing the bile duct far from the pancreatic duct, by sectioning the papilla proximally, and thus avoiding the ostium (proximal half of the papilla). PF was initially described by Osnes et al[9]. These authors observed a spontaneous choledochoduodenal fistula during ERCP. Contrast injection through the fistula detected bile duct stones. After enlargement of the fistula with a diathermic snare, the patients were observed for a few days with the spontaneous exit of the stones. Sakai et al[10] reported a pancreatitis occurrence rate of 7.6% in 2001, particularly in the setting of previous manipulation of the papilla, and trauma to the pancreatic duct, after several frustrated attempts at biliary tract cannulation.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the success of the PF technique, in the cannulation of the biliary tract. The secondary objective was to assess the enzyme profile and ensuing complications, in comparison with direct cannulation.

From July 2010 to May 2017, candidates for ERCP due to choledocolithiasis were recruited at Ana Costa Santos Hospital and the Endoscopy Unit of the Clinical Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sao Paulo. Enrolled patients were randomized for conventional cannulation with a catheter and guidewire (Group I) and PF (Group II).

Inclusion criteria were adult (both sexes) with choledocholithiasis and diagnosis by abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), cholangio resonance, or intraoperative cholangiography. Exclusion criteria were Billroth II gastrectomy, duodenal obstruction, coagulopathy or anticoagulant use, pregnancy or lactation, acute pancreatitis, myocardial infarction in the last 6 mo, previous papillotomy, or refusal to participate in the study.

The protocol was approved by the institutional Ethical Committee, and also registered as a randomized trial at the University of Sao Paulo Registry-MA3: 014/2010 and 0671/09. Informed consent was signed by all participants. Side-view endoscopes (Pentax ED-3670TK, Olympus TJF-160, or Fujinon ED-250XT5) were used during the ERCP. WEM SS-200E, Erbe ICC 200 and ValleyLab Force FX electrosurgical units were employed.

Group I

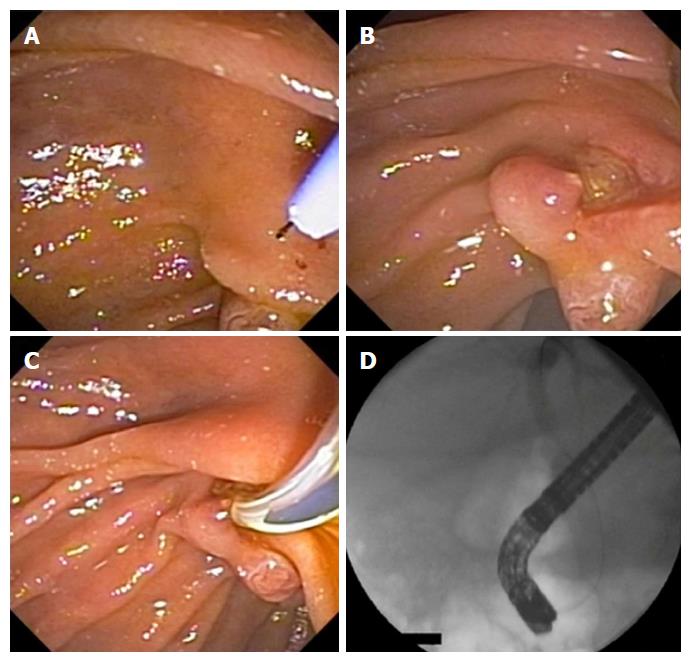

Cannulation of the papillary ostium was performed using a 4.4 Fr sphincterotome (TRUEtome; Boston Scientific) with a 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire; Boston Scientific). A pure cut current (50 watts), applied in short-duration pulses, was adopted to perform papillotomy. A 30-watt pure cut current was indicated for intradiverticular papillae, and the complementation of fistulotomies (Figures 1 and 2).

A difficult cannulation was recognized if it took > 10 min, required > 5 cannulation attempts, or when > 2 pancreatic duct penetrations occurred. Difficult cases were referred to PF. Pancreatic plastic stents were placed in case of prolonged procedure.

Group II

Incision was made on the mucosa, using a needle-knife catheter (MicroKnife XL; Boston Scientific), in distal to proximal direction, aiming at the papillary apex. It involved the proximal two-thirds of the papillary protuberance, and above the papillary orifice (approximately 5 mm far from the ostium). A pure cutting current (30 watts) was used to section the mucosa and the choledochal sphincter. The dissection was stopped when biliary secretion, open bile duct mucosa, or bulging of the bile duct mucosa was identified. The fistula was cannulated into the bile duct with a guidewire and sphincterotome, and it was enlarged by cutting the sphincter, to the limit of the transverse mucosal fold.

The PF procedure was stopped when there were signs of perforation, false route, major bleeding, loss of anatomy, or if cannulation of the bile duct was not achieved within 15 min. In these cases, the procedure was repeated after 5 to 7 d.

Enzymatic abnormalities (serum amylase and lipase) were documented up to 24 h before the examination (T0), as well as 12 h and 24 h after the endoscopic procedure. The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was based on persistent or worsening abdominal pain 24 h following ERCP and abnormal laboratory data, complemented by imaging methods. An amylase or lipase concentration of more than three times the upper limit of normal was considered diagnostic[11].

Hyperamylasemia was defined as amylase and/or lipase 3 times the upper limit of normal (> 300 U/L), without clinical features of pancreatitis. Inflammatory changes were monitored by serum C-reactive protein, collected at the same times.

A duodenal perforation was defined as gas or contrast accumulation in the retroperitoneum detected by simple X-ray of the abdomen. Endoscopic evidence, and clinical-laboratory findings consistent with bleeding were carefully monitored. These included bloody vomit or stools. Whenever the problem was suspected, hemoglobin concentration was serially measured, starting at 12 h after the intervention, and compared with preprocedure values, with hemoglobin drop of 2 g/dL.

Patients were admitted for 24 h after the endoscopic procedure and under fasting condition. Asymptomatic patients without laboratorial or radiological signs of pancreatitis or other complications were discharged after 24 h and contacted by phone call 36 h and 48 h after discharge to ensure there were no symptoms. Any symptomatic patient would be referred to the hospital for clinical and laboratorial assessment. If a complication occurred, the patient remained hospitalized until complete recovery was observed. All complications were managed using a multidisciplinary approach and according to international guidelines, with consensus between the Endoscopist and Surgeon.

Calculations were based on similar studies, reporting a biliary cannulation failure rate of 5% to 20%[1,2]. Adopting a 95% confidence interval of 3.65, a total population of 90 patients, and a minimum method failure rate of 2% (total ERCP success of 98% as maximum), 35 patients were deemed necessary per group. For safety, 51 patients were allocated to each group.

Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS for Windows version 20.0. The significance level was 5%. Randomization employed sealed envelopes, and descriptive statistics comprised mean ± SD as well as median, minimum and maximum, whenever appropriate. Student’s t test and Mann-Whitney test were used for comparisons, depending on initial normality assessment. Qualitative characteristics were informed as absolute and relative frequencies, and compared by means of chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, and likelihood ratio test[12]. Pancreatic enzyme curves were compared by generalized estimating equations (GEE), with gamma marginal distribution and identity link function, within a first order autoregressive correlation matrix between the evaluation times.

A total of 102 patients were selected and randomized into Group I (51 patients) and Group II (51 patients). There were no post hoc exclusions. Table 1 demonstrates that the demographic and preliminary clinical findings were comparable (P > 0.05).

| Variable | Group I, n = 51 | Group II, n = 51 | Total, n = 102 | P value |

| Age in yr | 0.3431 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 57.4 ± 19.3 | 60.9 ± 18.1 | 59.1 ± 18.7 | |

| Median (min; max) | 56 (19; 91) | 64 (22; 95) | 58 (19; 95) | |

| Sex, n (%) | > 0.9992 | |||

| Female | 33 (64.7) | 33 (64.7) | 66 (64.7) | |

| Male | 18 (35.3) | 18 (35.3) | 36 (35.3) | |

| AST | 0.680 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 116.3 ± 143.4 | 124.3 ± 168.3 | 120.1 ± 155.1 | |

| Median (min; max) | 44 (8; 691) | 60 (13; 762) | 50 (8; 762) | |

| ALT | 0.873 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 163.6 ± 191.6 | 154.1 ± 169.3 | 159 ± 180.4 | |

| Median (min; max) | 83 (9; 776) | 104 (11; 662) | 90 (9; 776) | |

| AP | 0.585 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 267.8 ± 329.7 | 301.9 ± 320.4 | 284.3 ± 323.9 | |

| Median (min; max) | 153.5 (8; 1567) | 173 (32; 1320) | 162 (8; 1567) | |

| GGT | 0.821 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 532 ± 454.3 | 543.4 ± 578.2 | 537.5 ± 515.1 | |

| Median (min; max) | 466.5 (39; 1684) | 284 (11; 2269) | 382 (11; 2269) | |

| Total bilirubin | 0.994 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 4.1 ± 4.9 | 5.3 ± 7.5 | 4.7 ± 6.3 | |

| Median (min; max) | 2 (0.1; 23.4) | 2.1 (0.2; 29.2) | 2.1 (0.1; 29.2) | |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.683 | |||

| Mean ± σ | 3.6 ± 4.4 | 4.2 ± 6.3 | 3.9 ± 5.4 | |

| Median (min; max) | 1.6 (0.1; 20.9) | 1.1 (0.1; 22.4) | 1.5 (0.1; 22.4) |

As informed in Table 2, choledocholithiasis was confirmed in 80.4% and 62.7% of Groups I and II, respectively (P = 0.048). The success rate for biliary duct cannulation was higher in Group II (100%) than in Group I (76.48%) (P = 0.0002). PF was performed in a single session. Dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, and placement of biliary stents, were not different between the groups (P > 0.05). No difference in the risk of pancreatitis could be accounted to either intrahepatic or extrahepatic dilatation.

| Variable | Group I, n = 51 | Group II, n = 51 | Total, n = 102 | P value |

| Choledocolithiasis | 0.048 | |||

| No | 10 (19.6) | 19 (37.3) | 29 (28.4) | |

| Yes | 41 (80.4) | 32 (62.7) | 73 (71.6) | |

| Intrahepatic dilatation | 0.6572 | |||

| No | 36 (70.6) | 38 (74.5) | 74 (72.6) | |

| Yes | 15 (29.4) | 13 (25.5) | 28 (27.4) | |

| Extrahepatic dilatation | 0.5512 | |||

| No | 25 (49.02) | 22 (43.1) | 47 (46.1) | |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (3.9) | 1 (1.9)) | 3 (2.9) | 11 |

| Yes | 26 (50.98) | 29 (56.9) | 55 (53.9) | |

| Pancreatitis | 3 | 0 | 3 (2.9) | 0.09911 |

| Intra- or peridiverticular papilla | 0.046 | |||

| No | 43 (84.3) | 49 (96.1) | 92 (90.2) | |

| Yes | 8 (15.7) | 2 (3.9) | 10 (9.8) | |

| Prosthesis | 0.236 | |||

| No | 42 (82.4) | 37 (72.6) | 79 (77.5) | |

| Yes | 9 (17.6) | 14 (27.4) | 23 (22.5) | |

| Biliary prosthesis | 0.463 | |||

| No | 42 (82.4) | 39 (76.5) | 81(79.4) | |

| Yes | 9 (17.6) | 12 (23.5) | 21 (20.6) | |

| Cholangitis | 0.6781 | |||

| No | 49 (96.1) | 47 (92.2) | 96 (94.1) | |

| Yes | 2 (3.9) | 4 (7.9) | 6 (5.9) | |

| Biliary access | ||||

| No | 12 (23.5) | 0 | 0.00021 | |

| Yes | 39 (76.5) | 51 (100) | ||

| Complications,pancreatitis, bleeding or perforation | 0.05371 | |||

| No | 44 (86.3) | 50 (98) | 94 (92.2) | |

| Yes | 7 (13.7) | 1 (2) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Pancreatitis | 5 | 1 | ||

| Perforation | 2 | 1 | ||

| Bleeding | 0 | 0 |

Intra- or peridiverticular papillae were observed in 15.7% and 3.9% of the populations, respectively (P = 0.046). Twelve cannulations (23.5%) were classified as difficult, thus migrating to the PF technique (Figure 3). Groups I and II had complication rates of 13.7% and 2.0%, respectively, which barely failed to reach significance (P = 0.0597). Two perforations and five cases of pancreatitis were observed in the first group, compared to a single case of retroperitoneal perforation and pancreatitis in the second one.

Table 3 reveals that the number of cannulations, as expected, was significantly different in the difficult cannulation group (P < 0.001), unlike ERCP findings, stent placement or complications (P > 0.05).

| Variable | Groups | Total, n = 102 | P value | ||

| Group I, n = 51 | Group II, n = 51 | ||||

| GWC, n = 39 | Difficult cannulation, n = 12 | ||||

| Complications, pancreatitis, bleeding or perforation | 0.062 | ||||

| No | 34 (87.2) | 10 (83.3) | 50 (98) | 94 (92.2) | |

| Yes | 5 (12.8) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (2) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Number of cannulations | < 0.0011 | ||||

| Mean ± σ | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 2.8 | 4.3 ± 2.8 | ||

| Median (min.; max.) | 3 (1; 10) | 8.5 (3; 10) | 3 (1; 10) | ||

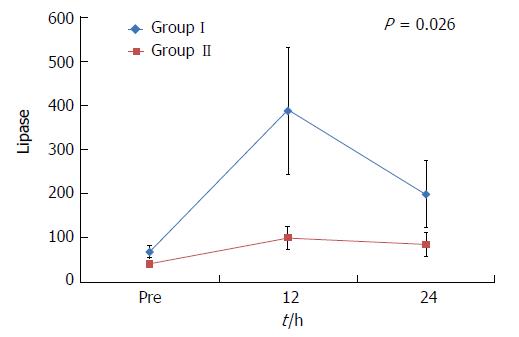

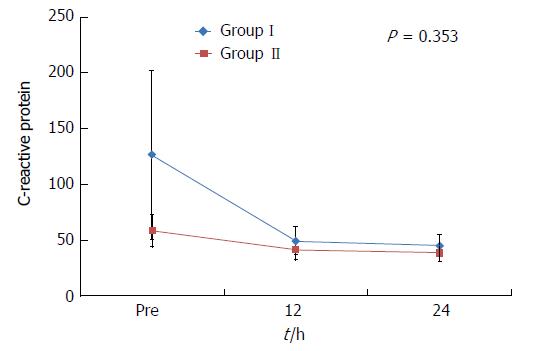

In Table 4 it can be appreciated that both lipase and amylase differed between the groups and over time (P = 0.026 and P = 0.013, respectively). In contrast, no discrepancy for C-reactive protein was detected regarding groups (P = 0.189) or time (P = 0.07).

| Variable | Group I, n = 51 | Group II, n = 51 | P value | P valuefor time | P value forinteraction | ||||

| Pre | 12 h | 24 h | Pre | 12 h | 24 h | ||||

| Lipase | 0.006 | < 0.001 | 0.026 | ||||||

| mean ± | 69.4 ± 102.1 | 439.0 ± 1064.8 | 199.5 ± 528.3 | 41.4 ± 37.2 | 100.6 ± 183.3 | 85.2 ± 189.1 | |||

| median (min; max) | 38 (9; 611) | 52 (10; 5014) | 48 (8; 3000) | 32 (0; 239) | 42.5 (8; 968) | 40 (5; 1334) | |||

| Amylase | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.013 | ||||||

| mean ± | 76.4 ± 57.8 | 453.5 ± 1287.4 | 304.0 ± 979.3 | 59.6 ± 36.2 | 98.1 ± 94.3 | 85.8 ± 102.6 | |||

| median (min; max) | 59 (12; 310) | 80 (14; 7900) | 70 (13; 6721) | 50 (14; 236) | 69 (21; 624) | 67.5 (12; 732) | |||

| C-reactive protein | 0.189 | 0.070 | 0.353 | ||||||

| mean ± | 126.6 ± 539.7 | 49.5 ± 89.7 | 45.4 ± 70.5 | 58.6 ± 104.8 | 41.4 ± 62.0 | 38.8 ± 52.9 | |||

| median (min; max) | 11.1 (0.1; 3813) | 15.5 (0.3; 486.1) | 19.16 (0.5; 340.9) | 12 (0.2; 549) | 13.8 (0.3; 271) | 16.6 (0.5; 223.1) | |||

Figures 4-6 depict the amylase and lipase elevations in Group I patients. C-reactive protein, as alluded to, failed to exhibit discriminant patterns.

Pancreatitis is the most frequent complication of ERCP, occurring in as many as 15.1% of the patients[6-8,13,14]. It is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Precut techniques have been associated with a high risk of PEP in previous studies[7,8,15-17].

A difficult cannulation is an independent risk factor[18,19]. The failure rate of primary biliary tract cannulation, with the use of a sphincterotome, was calculated as 2.5%-24% without a guidewire[20-23] and 1.5%-10%[21,23,24] adopting the wire. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy benchmark for cannulation success during ERCP procedures of low to moderate complexity is > 90% for all indications[25].

In this study, the primary success rate was 76.5%, with 9.8% of PEP. Difficult cannulation occurred in 12 patients, yet access was achieved via PF in all these individuals. The high failure rate (23.5%) may be explained by the participation of fellows, who are less experienced, thus making additional attempts by endoscopists with greater expertise required. Nevertheless, papillary trauma eventually inflicted during the first intervention may hinder subsequent access, thus compromising the overall success rate.

Common bile duct stones were not found in all cases during ERCP, possibly on account of the long period that had elapsed since the original diagnosis in the primary care institution. It is important to mention that per protocol, PF was conducted directly, without prior manipulation by conventional techniques. Cannulation of the bile duct using PF was accomplished in all patients in Group II. Three previous studies with a similar design displayed 89.3%-96.5% success rates for fistulotomy[26-28]. In the control group (conventional technique), the corresponding values were 70.6% and 88%[26-28].

The mean diameter of the common bile duct in this experience was 8.7 mm (5-18.2 mm). Sakai et al[10] in 2001, suggested that PF be reserved mainly for patients with a dilated common bile duct. Jin et al[27] concluded in 2016, based on 55 interventions, that a bile duct < 9 mm was a risk factor. Yet Khatibian et al[26] reported in 2008 that the diameter of the common bile duct was not relevant for need of PF.

In the current series, PF (Group II and Failures) was performed in 28 of 63 patients (44.4%; P = 0.834); for each, being performed through the common bile duct without dilatation. No difference in the risk of pancreatitis emerged when considering the caliber of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tracts. Bile duct stones could not be removed in the first attempt in 20.8% of the cases, due to large size; therefore, in these cases, a biliary stent was placed.

Hyperamylasemia was observed in 2 patients in Group I (P = 0.49). Transient asymptomatic elevations in amylase, lipase, or both, range from 0 to 64% in the literature[29-31]. Asymptomatic hyperamylasemia, defined as amylase levels > 5 times the upper limit at 24 h after ERCP, has been reported in approximately 27% of the cases[32].

In our study, the number of cannulation attempts significantly correlated with increased lipase and amylase levels, at 12 h and 24 h after the procedure. In a series of 907 patients, the rates of PEP were 0.6%, 3.1%, 6.1% and 11.9% following one, two, three to four, and more than five primary cannulation attempts that led to success, respectively. PEP risk increased to 11.5% if the primary cannulation method failed[19]. In our study, PEP occurred following the guidewire cannulation (GWC) technique in 5 patients (9.8%), of which 2 (3.9%) exhibited a difficult papillary access, which was only achieved by means of PF.

No significant increase in pancreatic enzymes was observed, and the incidence of PEP was not greater in the group that underwent PF as the initial procedure; neither did the 12 patients with PF as a rescue procedure exhibit a different pattern. This demonstrates the safety of PF, whenever performed or supervised by experienced physicians. In 2016, Zagalsky et al[33] compared early precut (PCP) techniques and use of a pancreatic duct stent in 101 patients who suffered difficult cannulations. The success rates of biliary cannulation (98% and 96%), and the occurrence of PEP (4% and 3.92%) were similar between the early PCP and stent groups, respectively. Two perforations and bleeds occurred in the early PCP group, which also demonstrates the safety of the procedure compared to standard PEP prevention technique after a failed GWC.

Other recent studies have shown that precut techniques lead to an increased rate of successful deep biliary tract access and that their early use by experienced endoscopists results in a decrease in PEP[4,27,34]. Weerth et al[2] compared primary PCP and GWC for bile duct access and reported a success rate at the first attempt of 100% and 71%, respectively. They observed mild to moderate PEP in 2.1% and 2.9% (P > 0.05), after primary PCP or GWC, respectively. Only 1 patient (in the GWC group) suffered from postpapillotomy bleeding. In our experience, a single patient presented a retroperitoneal perforation and pancreatitis in Group II, both of which were conservatively managed.

There were two perforations (3.9%) in Group I, and the one (1.9%) in Group II already alluded to, which were always conservatively treated. No bleeding was observed. The negligible incidence of bleeding is consistent with previous precut studies (0-3.4%)[2,17,26,28,35]. In regards to perforation (0-1.8%), our results are also quite acceptable[2,17,26,28,35].

In conclusion, PF was more effective than GWC, and it was associated with a lower profile of amylase and lipase, as the routine endoscopic access to the biliary tree, including difficult cases. Complications were similar in both groups.

Successfully cannulating the biliary tract is important in the diagnosis and treatment of biliopancreatic diseases with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), but it can be associated with severe complications and mortality.

The number of papers regarding comparison between conventional cannulation versus fistulotomy is small. Our study is a well-designed approach in its matter.

To compare the cannulation success, biochemical profile, and complications of the papillary fistulotomy technique versus catheter and guidewire standard access.

Patients were prospectively randomized into two groups: cannulation with a catheter and guidewire (Group I) and papillary fistulotomy (Group II). Amylase, lipase and C-reactive protein at T0 as well as 12 h and 24 h after ERCP, and complications (pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation) were recorded. Comparison was made of the cannulation success, biochemical profile and complications of the papillary fistulotomy technique vs catheter and guidewire standard access.

We included 102 patients, and Groups I and II had 51 patients each. The successful cannulation rates were 76.5% and 100%, respectively (P = 0.0002). Twelve patients (23.5%) in GroupI had a difficult cannulation and underwent fistulotomy, which led to successful secondary biliary access (Failure Group). The complication rate was 13.7% (2 perforations and 5 mild pancreatitis) in Group I versus 2.0% (1 patient with perforation and pancreatitis) in Group II (P = 0.0597).

Papillary fistulotomy was more effective than guidewire cannulation, and it was associated with a lower profile of amylase and lipase. Complications were similar in both groups.

The fistulotomy demonstrated safety similar to conventional cannulation and less local trauma into the ampulla, according to the levels of the amylase, lipase and C-reactive protein.

| 1. | Abu-Hamda EM, Baron TH, Simmons DT, Petersen BT. A retrospective comparison of outcomes using three different precut needle knife techniques for biliary cannulation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:717-721. [PubMed] |

| 2. | de Weerth A, Seitz U, Zhong Y, Groth S, Omar S, Papageorgiou C, Bohnacker S, Seewald S, Seifert H, Binmoeller KF. Primary precutting versus conventional over-the-wire sphincterotomy for bile duct access: a prospective randomized study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1235-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sundaralingam P, Masson P, Bourke MJ. Early Precut Sphincterotomy Does Not Increase Risk During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Patients With Difficult Biliary Access: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1722-1729.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mariani A, Di Leo M, Giardullo N, Giussani A, Marini M, Buffoli F, Cipolletta L, Radaelli F, Ravelli P, Lombardi G. Early precut sphincterotomy for difficult biliary access to reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2016;48:530-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1703] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Mavrogiannis C, Liatsos C, Romanos A, Petoumenos C, Nakos A, Karvountzis G. Needle-knife fistulotomy versus needle-knife precut papillotomy for the treatment of common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:334-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhou W, Li Y, Zhang Q, Li X, Meng W, Zhang L, Zhang H, Zhu K, Zhu X. Risk factors for postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a retrospective analysis of 7,168 cases. Pancreatology. 2011;11:399-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Osnes M, Kahrs T. Endoscopic choledochoduodenostomy for choledocholithiasis through choledochoduodenal fistula. Endoscopy. 1977;9:162-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sakai P, Artifon ELA, Maluf Filho F. Fistulopapilotomia Endoscópica: Uma Alternativa à Papila de Difícil Cateterização. GED. 2001;20:208-212. |

| 11. | Lerch MM. Classifying an unpredictable disease: the revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2013;62:2-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kirkwood B, JAC S. Essential Medical Statistics. Massachusetts, United States: Blackwell Science; 2006; . |

| 13. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bailey AA, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Walsh PR, Murray MA, Lee EY, Kwan V, Lynch PM. A prospective randomized trial of cannulation technique in ERCP: effects on technical success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2008;40:296-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bailey AA, Bourke MJ, Kaffes AJ, Byth K, Lee EY, Williams SJ. Needle-knife sphincterotomy: factors predicting its use and the relationship with post-ERCP pancreatitis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Halttunen J, Keränen I, Udd M, Kylänpää L. Pancreatic sphincterotomy versus needle knife precut in difficult biliary cannulation. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:745-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | O'Connor HJ, Bhutta AS, Redmond PL, Carruthers DA. Suprapapillary fistulosphincterotomy at ERCP: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 1997;29:266-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 852] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Halttunen J, Meisner S, Aabakken L, Arnelo U, Grönroos J, Hauge T, Kleveland PM, Nordblad Schmidt P, Saarela A, Swahn F. Difficult cannulation as defined by a prospective study of the Scandinavian Association for Digestive Endoscopy (SADE) in 907 ERCPs. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:752-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Laasch HU, Tringali A, Wilbraham L, Marriott A, England RE, Mutignani M, Perri V, Costamagna G, Martin DF. Comparison of standard and steerable catheters for bile duct cannulation in ERCP. Endoscopy. 2003;35:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lella F, Bagnolo F, Colombo E, Bonassi U. A simple way of avoiding post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:830-834. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Schwacha H, Allgaier HP, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Allgaier U, Blum HE. A sphincterotome-based technique for selective transpapillary common bile duct cannulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Artifon EL, Sakai P, Cunha JE, Halwan B, Ishioka S, Kumar A. Guidewire cannulation reduces risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis and facilitates bile duct cannulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2147-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Gao WD, He GJ, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Qin XY. Application of needle-knife in difficult biliary cannulation for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:590-594. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Adler DG, Lieb JG 2nd, Cohen J, Pike IM, Park WG, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Scheiman JM, Shaheen NJ, Sherman S, Wani S. Quality indicators for ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:54-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Khatibian M, Sotoudehmanesh R, Ali-Asgari A, Movahedi Z, Kolahdoozan S. Needle-knife fistulotomy versus standard method for cannulation of common bile duct: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11:16-20. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Jin YJ, Jeong S, Lee DH. Utility of needle-knife fistulotomy as an initial method of biliary cannulation to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in a highly selected at-risk group: a single-arm prospective feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:808-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ayoubi M, Sansoè G, Leone N, Castellino F. Comparison between needle-knife fistulotomy and standard cannulation in ERCP. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:398-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tanaka R, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Tsuji S, Ishii K, Ikeuchi N, Umeda J. Is the double-guidewire technique superior to the pancreatic duct guidewire technique in cases of pancreatic duct opacification? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1787-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nishino T, Toki F, Oyama H, Shiratori K. More accurate prediction of post-ercp pancreatitis by 4-h serum lipase levels than amylase levels. Dig Endosc. 2008;20:169-177. |

| 31. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Cremer M. A new method of achieving deep cannulation of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Testoni PA, Testoni S, Giussani A. Difficult biliary cannulation during ERCP: how to facilitate biliary access and minimize the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:596-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zagalsky D, Guidi MA, Curvale C, Lasa J, de Maria J, Ianniccillo H, Hwang HJ, Matano R. Early precut is as efficient as pancreatic stent in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk subjects - A randomized study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:258-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can early precut implementation reduce endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complication risk? Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2010;42:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Huibregtse K, Katon RM, Tytgat GN. Precut papillotomy via fine-needle knife papillotome: a safe and effective technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:403-405. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kahraman A, Ker CG S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y