Published online Apr 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i14.1550

Peer-review started: December 1, 2017

First decision: December 13, 2017

Revised: February 6, 2018

Accepted: March 7, 2018

Article in press: March 6, 2018

Published online: April 14, 2018

Processing time: 131 Days and 12.8 Hours

To compare vonoprazan 10 and 20 mg vs lansoprazole 15 mg as maintenance therapy in healed erosive esophagitis (EE).

A total of 607 patients aged ≥ 20 years, with endoscopically-confirmed healed EE following 8 wk of treatment with vonoprazan 20 mg once daily, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive lansoprazole 15 mg (n = 201), vonoprazan 10 mg (n = 202), or vonoprazan 20 mg (n = 204), once daily. The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of endoscopically-confirmed EE recurrence during a 24-wk maintenance period. The secondary endpoint was the EE recurrence rate at Week 12 during maintenance treatment. Additional efficacy endpoints included the incidence of heartburn and acid reflux, and the EE healing rate 4 wk after the initiation of maintenance treatment. Safety endpoints comprised adverse events (AEs), vital signs, electrocardiogram findings, clinical laboratory results, serum gastrin and pepsinogen I/II levels, and gastric mucosa histopathology results.

Rates of EE recurrence during the 24-wk maintenance period were 16.8%, 5.1%, and 2.0% with lansoprazole 15 mg, vonoprazan 10 mg, and vonoprazan 20 mg, respectively. Vonoprazan was shown to be non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg (P < 0.0001 for both doses). In a post-hoc analysis, EE recurrence at Week 24 was significantly reduced with vonoprazan at both the 10 mg and the 20 mg dose vs lansoprazole 15 mg (5.1% vs 16.8%, P = 0.0002, and 2.0% vs 16.8%, P < 0.0001, respectively); by contrast, the EE recurrence rate did not differ significantly between the two doses of vonoprazan (P = 0.1090). The safety profiles of vonoprazan 10 and 20 mg were similar to that of lansoprazole 15 mg in patients with healed EE. Treatment-related AEs were reported in 11.4%, 10.4%, and 10.3% of patients in the lansoprazole 15 mg, vonoprazan 10 mg, and vonoprazan 20 mg arms, respectively.

Our findings confirm the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 10 and 20 mg to lansoprazole 15 mg as maintenance therapy for patients with healed EE.

Core tip: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), including lansoprazole, are widely used to maintain healing of erosive esophagitis (EE) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease; however, symptoms of reflux persist in significant numbers of patients treated with PPIs. We compared two doses of the novel potassium-competitive acid blocker vonoprazan (10 and 20 mg once daily) with lansoprazole at its approved dose of 15 mg once daily as maintenance therapy for healed EE in 607 Japanese patients. Vonoprazan was shown to be non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg at both investigated doses, while demonstrating a similar safety profile.

- Citation: Ashida K, Iwakiri K, Hiramatsu N, Sakurai Y, Hori T, Kudou K, Nishimura A, Umegaki E. Maintenance for healed erosive esophagitis: Phase III comparison of vonoprazan with lansoprazole. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(14): 1550-1561

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i14/1550.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i14.1550

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common gastric acid-related disorder that is characterized by heartburn and/or acid regurgitation caused by the reflux of gastric contents[1]. The spectrum of GERD ranges from non-erosive to erosive or complicated disease (ulcer, columnar metaplasia, and stricture), each of which is thought likely to progress if either left untreated or not treated adequately[2]. The main goals for the clinical management of GERD consist of symptom relief, healing of erosive esophagitis (EE), prevention of recurrences and complications, and overall improvement of patients’ quality of life[1,3].

Owing to their superior ability to inhibit gastric acid secretion compared with H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the mainstay of long-term therapy for GERD[1,3-5]. However, resolution of GERD symptoms with PPIs appears to have a less predictable outcome than esophageal mucosal inflammation[4-6], with reflux symptoms persisting in up to 60% of patients treated with PPIs in randomized controlled clinical trials[7] and observational studies[5]. Proposed underlying mechanisms for PPI failure include drug- and patient-related factors, such as low bioavailability, nocturnal acid breakthrough, rapid metabolism (CYP2C19 extensive metabolizer genotype), and poor compliance with the prescribed regimen[6]. The slow cumulative onset of PPI action at therapeutic doses may also be a contributing factor[8-10]. These limitations have led to a renewed interest in alternative treatment modalities for the management of patients with GERD[1,4].

Discovered and developed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Japan, vonoprazan fumarate (TAK-438) belongs to a novel class of acid suppressants known as potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs)[11]. Like PPIs, vonoprazan inhibits gastric H+, K+-ATPase, an enzyme that catalyzes the final step in the acid secretion pathway. However, unlike PPIs, vonoprazan inhibits the enzyme in a K+-competitive and reversible manner[12], with its inhibitory effects (pKa 9.4) on gastric acid secretion largely unaffected by ambient pH, as it accumulates in parietal cells under both acidic and resting conditions[12,13]. In animal studies, vonoprazan produced more potent and sustained suppression of gastric acid secretion than lansoprazole[11-14]. In healthy volunteers, single doses of vonoprazan 1-120 mg were well tolerated, and produced rapid, prolonged, and dose-related suppression of 24-h gastric acid secretion[15]. In another study in healthy volunteers, these effects were maintained with multiple dosing (10-40 mg once daily) over 7 d, and were also dose-related[16].

Lansoprazole 30 mg once daily is the recommended dosage for healing EE, while its step-down dose of 15 mg once daily is recommended for the maintenance treatment of healed EE, providing well-balanced efficacy and safety over the long term[17]. The current study aimed to demonstrate that vonoprazan 20 mg and its step-down dose of 10 mg once daily were non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg once daily in preventing EE recurrence during a 24-wk maintenance period in Japanese patients who achieve EE healing after 2, 4, or 8 wk treatment with vonoprazan 20 mg.

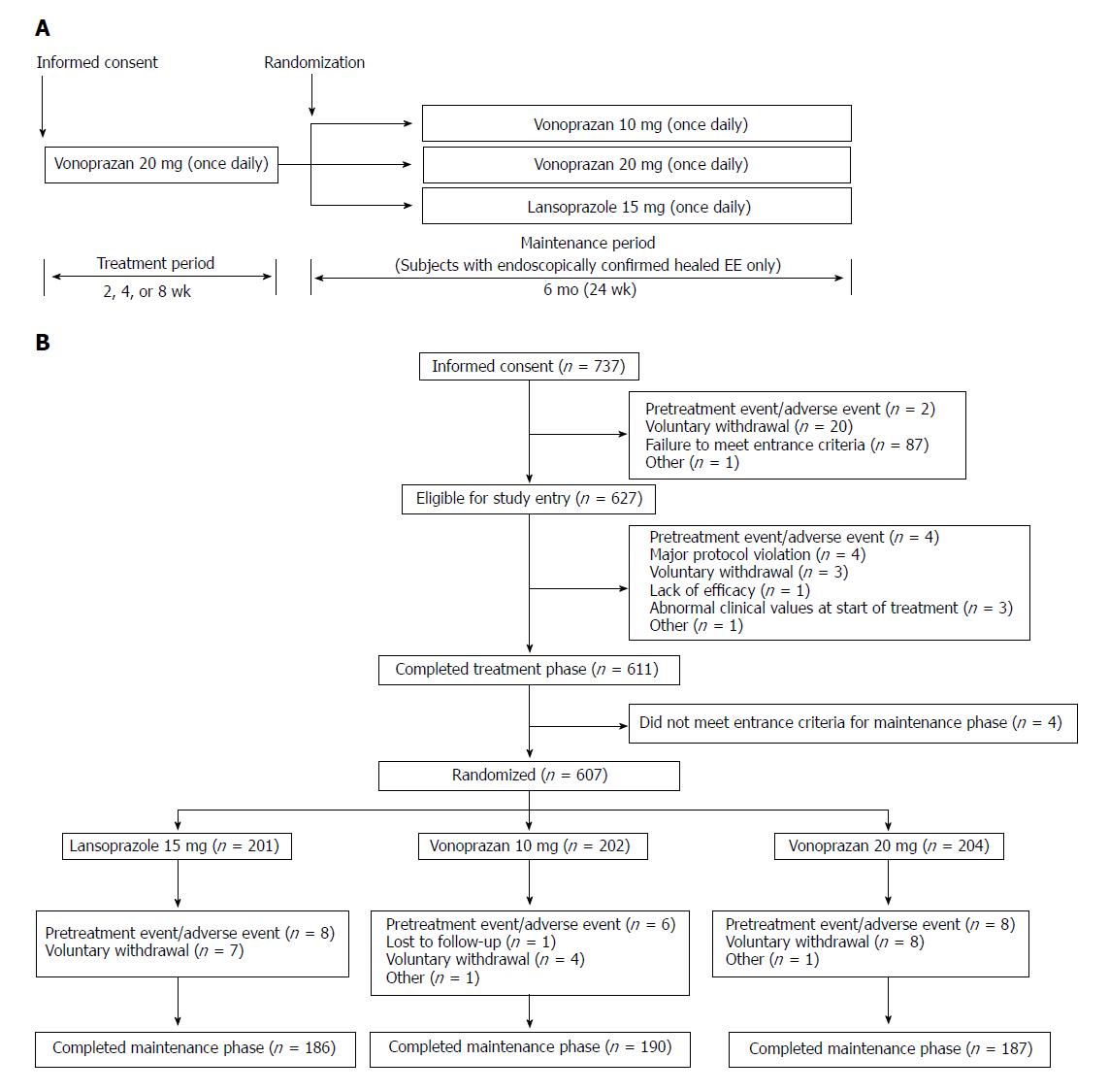

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase III clinical study, which was designed and conducted to demonstrate the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 20 and 10 mg to lansoprazole 15 mg as maintenance therapy in Japanese patients with healed EE. During the initial treatment period, patients with EE Los Angeles (LA) Classification grades A to D received vonoprazan 20 mg once daily for up to 8 wk. All patients in whom endoscopic healing of EE was confirmed 2, 4, or 8 wk after the start of the study medication were immediately stratified by baseline endoscopic LA Classification grade (A/B or C/D), and subsequently randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive maintenance therapy with vonoprazan 10 mg, vonoprazan 20 mg, or lansoprazole 15 mg given once daily after breakfast for 24 wk. All patients in whom endoscopic healing of EE was not confirmed at Week 8 completed the study without entering the maintenance phase. All patients in whom EE recurrence was endoscopically confirmed during maintenance treatment were withdrawn from the study and handled as ‘completed cases’.

Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT01459367, the study was conducted at 55 sites in Japan between November 2011 and March 2013. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study site, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and Japanese regulatory requirements. All patients provided written informed consent prior to undergoing any study procedures.

Male or female outpatients aged ≥ 20 years, who presented with endoscopically-confirmed healed EE (no mucosal breaks) after up to 8 wk of treatment with vonoprazan 20 mg once daily, entered the maintenance phase of the study. Main exclusion criteria included: esophageal complications (e.g., eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal varices, scleroderma, infection, esophageal stenosis); acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding; gastric or duodenal ulcer characterized by mucosal defects; hypersecretion disorders, such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; serious neurologic, cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) > 2.5 × the upper limit of normal (ULN)], renal (serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL), metabolic, gastrointestinal, urologic, endocrinologic, or hematologic disorders; need for surgery; history of drug (including alcohol) abuse; HIV or hepatitis; history of malignancy; and pregnancy or lactation in females. Any sexually active female of childbearing potential was required to use adequate contraceptive measures. Excluded concomitant medications included PPIs, H2RAs, muscarinic M3 receptor antagonists, gastrointestinal motility stimulants, anticholinergic drugs, prostaglandins, acid suppressants, anti-gastrin drugs, mucosal protective agents, H. pylori eradication therapies, atazanavir sulfate, and any other investigational drug. As the exclusion of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) would have been difficult for patients eligible for inclusion in this study, their use was permitted; however, changes to NSAID regimens during the study were prohibited.

Patients were randomized to treatment groups in a 1:1:1 ratio according to a computer-generated randomization schedule prepared by independent randomization personnel. The independent randomization personnel managed the randomization process, and stored the randomization schedule in a secure area. The randomization schedule incorporated LA Classification grades as a stratification factor (A/B or C/D), to ensure that treatment groups were balanced with respect to disease severity. A double-dummy method, using matched vonoprazan placebo tablets and lansoprazole placebo capsules, was employed to ensure that the double-blind conditions were maintained throughout the study.

Maintenance treatment was initiated on the day of randomization. Clinic visits were scheduled at Weeks 4, 12, and 24, or upon early withdrawal from the study (discontinuation/recurrence). Endoscopic examinations were performed at Weeks 12 and 24. A central adjudication committee (CAC), composed of independent experts, was established to perform standardized and consistent reviews of endoscopic EE grading by investigators, while all decisions about patient eligibility and withdrawal owing to EE recurrence were made by the investigators, irrespective of the CAC’s assessment. Safety assessments were conducted at Weeks 4, 12, and 24. Histopathologic examinations of the gastric mucosa were performed at the start of treatment (baseline) and at Week 24 for subjects enrolled at designated study sites only. All biopsy specimens were full mucosal layer samples taken from the greater curvature of the upper gastric corpus during endoscopic procedures. Samples were fixed in 20% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Five slices were taken from each paraffin block, and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Grimelius, chromogranin, synaptophysin, and Ki-67 (MIB-1). For the CYP2C19 genotyping, a single 2 mL blood sample was collected at Week 4, and was analyzed to obtain information on genotypes that affect the pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole. G681A (*2) and G636A (*3) of CYP2C19 were detected using an Invader® assay. Both the histopathologic testing and CYP2C19 genotyping were carried out by Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan. The gastric mucosa histopathology findings reported by the company were reviewed by an independent assessment committee, which assessed specimens for distribution patterns of Grimelius-positive cells, chromogranin A-positive cells, synaptophysin-positive cells, and Ki-67-positive cells. Treatment compliance was assessed in all patients on the basis of returned tablet/capsule counts at each study site visit.

Although no evidence has been reported of vonoprazan-associated liver function test abnormalities[18], drug-related hepatic changes have previously been reported with another member of the P-CAB drug class[19]. Liver function abnormalities (ALT or AST > 3 × ULN, or total bilirubin > 2 × ULN in two consecutive measurements) were therefore classified as special-interest adverse events (SIAEs) in the present study, and were monitored throughout.

The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrence of endoscopically-confirmed EE at Week 24 of the maintenance period. The secondary endpoint was the rate of EE recurrence at Week 12 of the maintenance period. Safety endpoints included adverse events (AEs), vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, clinical laboratory test values (hematology, serum chemistry, and urinalysis), serum gastrin and pepsinogen I/II levels, and gastric mucosa histopathologic findings.

A double-blind, controlled study of lansoprazole as maintenance therapy for patients with healed EE reported EE recurrence rates of 30% and 14% with lansoprazole 15 mg and 30 mg, respectively, over 24 wk[20]. It was therefore assumed that the endoscopic EE recurrence rate with vonoprazan 20 mg in the present study would be 14%, while the EE recurrence rate with vonoprazan 10 mg would be 22% - that is, halfway between the rates observed with lansoprazole 15 mg and 30 mg in the study mentioned above. It was assumed that the EE recurrence rate with lansoprazole 15 mg would again be 30%. Based on these assumptions, a sample size of 148 patients per treatment group would provide > 90% power to confirm the non-inferiority of the two vonoprazan doses to lansoprazole, with respect to the EE recurrence rate at Week 24, with a non-inferiority margin of 10% utilizing a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI). Assuming a dropout rate of 15% during maintenance therapy, 174 randomized patients would be required for each treatment group. We therefore set the randomization target at 200 patients per treatment group, to enable evaluation of the long-term safety of vonoprazan in a sufficient number of patients.

For the primary endpoint of EE recurrence rate at Week 24 of maintenance treatment, frequency, point estimates, and corresponding 95%CIs were calculated by treatment group for the full analysis set (FAS), defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug during the maintenance period. Vonoprazan 10 mg and 20 mg were evaluated for non-inferiority to lansoprazole 15 mg using the Farrington and Manning test[21] with a non-inferiority margin of 10%. The same analyses were performed for the secondary endpoint.

AEs (including their frequency, severity, investigator-assessed causality, and seriousness) and concomitant medications were monitored throughout the study. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 16.0. All TEAEs were summarized descriptively by treatment group, time of onset, and severity, and were categorized by System Organ Class and Preferred Term. All drug-related TEAEs were summarized by severity, while TEAEs leading to study discontinuation and serious TEAEs were summarized by treatment group.

The statistical methods of this study were prepared and conducted by Kentarou Kudou of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and were reviewed and approved by Takamasa Hashimoto of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Osaka, Japan.

In total, 737 patients signed the informed consent form. Of these 737 patients, 627 were enrolled into the treatment phase, with 611 patients completing up to 8 wk treatment for EE with vonoprazan 20 mg. Of the 611 who completed treatment, 607, who represented both the FAS and the safety analysis set (SAS), were randomized to maintenance therapy with lansoprazole 15 mg (n = 201), vonoprazan 10 mg (n = 202), or vonoprazan 20 mg (n = 204) (Figure 1). Five hundred sixty-three patients (92.8%) completed maintenance treatment. The main reasons for premature study discontinuation were pretreatment events/AEs (n = 22) and voluntary withdrawals (n = 19). The first informed consent form was signed on 21 November 2011, and the last follow-up visit took place on 7 March 2013.

The three maintenance groups were well matched in terms of demographic and other baseline characteristics (Table 1), and had similar baseline EE severities and medical histories. The mean treatment compliance rate was > 97% in each treatment group.

| Characteristic | LPZ 15 mg (n = 201) | VPZ 10 mg (n = 202) | VPZ 20 mg (n = 204) |

| Age, yr | 57.8 ± 12.9 | 55.5 ± 13.8 | 56.8 ± 13.6 |

| Gender, male | 140 (69.7) | 160 (79.2) | 160 (78.4) |

| Height, cm | 163.5 ± 10.2 | 165.5 ± 9.3 | 165.6 ± 9.3 |

| Weight, kg | 67.0 ± 13.4 | 68.2 ± 12.3 | 69.0 ± 13.1 |

| Erosive esophagitis grade, investigator-assessed | |||

| LA Grade A/B | 160 (79.6) | 162 (80.2) | 161 (78.9) |

| LA Grade C/D | 41 (20.4) | 40 (19.8) | 43 (21.1) |

| Esophageal hiatal hernia | |||

| ≥ 2 cm | 31 (15.4) | 45 (22.3) | 46 (22.5) |

| < 2 cm | 105 (52.2) | 100 (49.5) | 113 (55.4) |

| None | 65 (32.3) | 57 (28.2) | 44 (21.6) |

| H. pylori infection status | |||

| Positive | 29 (14.4) | 37 (18.3) | 23 (11.3) |

| Negative | 172 (85.6) | 165 (81.7) | 181 (88.7) |

| CYP2C19 genotype | |||

| Extensive metabolizers | 162 (80.6) | 169 (84.1) | 169 (83.3) |

| Poor metabolizers | 39 (19.4) | 32 (15.9) | 34 (16.7) |

The rate of EE recurrence at 24 wk of maintenance therapy (primary endpoint) was 16.8%, 5.1%, and 2.0% with lansoprazole 15 mg, vonoprazan 10 mg, and vonoprazan 20 mg, respectively. Point estimates of differences in EE recurrence between the maintenance treatment groups and 95%CIs are shown in Table 2. Vonoprazan 10 mg and 20 mg were both found to be non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg in the FAS (both P < 0.0001), with the upper limits of 95%CIs for the differences between vonoprazan 10 mg or 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg being < 0, thus indicating a statistically significant difference. In a post-hoc analysis performed using the Fisher exact test, a statistically significant difference in the rate of EE recurrence was demonstrated between vonoprazan 10 mg or 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg (P = 0.0002 and P < 0.0001, respectively, vs lansoprazole 15 mg), but not between the two vonoprazan doses (P = 0.1090).

| Endpoint | LPZ 15 mg | VPZ 10 mg | VPZ 20 mg | |

| Week 24 (primary endpoint)1 | 16.8% (33/196) | 5.1% (10/197) | 2.0% (4/201) | |

| Week 12 (secondary endpoint)1 | 12.2% (24/196) | 2.5% (5/197) | 1.0% (2/201) | |

| Comparison | Difference and 95%CI (%) | Non-inferiority, P value | Fisher exact test, P value2 | |

| Week 24 (primary endpoint) | ||||

| VPZ 10 mg vs LPZ 15 mg | -11.8 [-17.83, -5.69] | < 0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| VPZ 20 mg vs LPZ 15 mg | -14.8 [-20.43, -9.26] | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| VPZ 10 mg vs VPZ 20 mg | -3.1 [-6.71, 0.54] | N/A | 0.1090 | |

| Week 12 (secondary endpoint) | ||||

| VPZ 10 mg vs LPZ 15 mg | -9.7 [-14.80, -4.62] | < 0.0001 | N/A | |

| VPZ 20 mg vs LPZ 15 mg | -11.2 [-16.04, -6.46] | < 0.0001 | N/A | |

| VPZ 10 mg vs VPZ 20 mg | -1.5 [-4.13, 1.05] | N/A | N/A | |

The intergroup differences in EE recurrence rate at Week 12 of the maintenance period (secondary endpoint) are shown in Table 2. Vonoprazan 10 mg and 20 mg were both shown to be non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg in the FAS; the upper limits of 95%CIs for the differences between vonoprazan 10 mg or 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg were < 0, thus consistently indicating a statistical difference.

Subgroup analyses were conducted on the EE recurrence rates during the 24-wk maintenance period according to age, sex, smoking classification, disease severity, extent of CYP2C19 metabolism, and H. pylori infection status. Post-hoc analyses confirmed that the differences in recurrence rates following treatment with vonoprazan 10 mg or 20 mg versus lansoprazole 15 mg were significant among: patients who were: aged < 65 years; of either sex; never smokers; had any LA classification grade; CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers; or H. pylori-negative (Table 3).

| LPZ 15 mg | VPZ 10 mg | VPZ 20 mg | |||||

| Estimate (%)1 | Estimate (%)1 | Difference2 and 95%CI (%) | Fisher exact test, P value3 | Estimate (%)1 | Difference2 and 95%CI (%) | Fisher exact test, P value3 | |

| Age (yr) | |||||||

| < 65 | 14.4 (19/132) | 4.3 (6/139) | -10.1 [-16.95, -3.20] | 0.0056 | 0.0 (0/136) | -14.4 [-20.38, -8.41] | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 65 to < 75 | 21.7 (10/46) | 7.0 (3/43) | -14.8 [-28.91, -0.62] | 0.0711 | 7.0 (3/43) | -14.8 [-28.91, -0.62] | 0.0711 |

| ≥ 75 | 22.2 (4/18) | 6.7 (1/15) | -15.6 [-38.54, 7.43] | 0.3457 | 4.5 (1/22) | -17.7 [-38.76, 3.41] | 0.1554 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 13.9 (19/137) | 6.3 (10/159) | -7.6 [-14.49, -0.67] | 0.0321 | 1.3 (2/159) | -12.6 [-18.65, -6.57] | < 0.0001 |

| Female | 23.7 (14/59) | 0.0 (0/38) | -23.7 [-34.58, -12.87] | 0.0007 | 4.8 (2/42) | -19.0 [-31.59, -6.35] | 0.0120 |

| Smoking classification | |||||||

| Never smoked | 22.4 (17/76) | 1.9 (1/54) | -20.5 [-30.55, -10.48] | 0.0006 | 5.0 (3/60) | -17.4 [-28.24, -6.50] | 0.0062 |

| Current smoker | 20.0 (8/40) | 6.6 (4/61) | -13.4 [-27.31, 0.42] | 0.0588 | 0.0 (0/57) | -20.0 [-32.40, -7.60] | 0.0005 |

| Ex-smoker | 10.0 (8/80) | 6.1 (5/82) | -3.9 [-12.27, 4.47] | 0.3998 | 1.2 (1/84) | -8.8 [-15.78, -1.84] | 0.0160 |

| Erosive esophagitis grade4 | |||||||

| LA Grade A/B | 11.0 (17/155) | 3.1 (5/159) | -7.8 [-13.44, -2.21] | 0.0075 | 1.3 (2/158) | -9.7 [-14.92, -4.48] | 0.0002 |

| LA Grade C/D | 39.0 (16/41) | 13.2 (5/38) | -25.9 [-44.26, -7.47] | 0.0114 | 4.7 (2/43) | -34.4 [-50.58, -18.17] | 0.0001 |

| CYP2C19 genotype | |||||||

| Extensive metabolizers | 19.6 (31/158) | 5.4 (9/166) | -14.2 [-21.28, -7.11] | 0.0001 | 1.8 (3/168) | -17.8 [-24.34, -11.33] | < 0.0001 |

| Poor metabolizers | 5.3 (2/38) | 3.2 (1/31) | -2.0 [-11.48, 7.40] | 1.0000 | 3.0 (1/33) | -2.2 [-11.43, 6.97] | 1.0000 |

| H. pylori infection status | |||||||

| Positive | 3.7 (1/27) | 2.7 (1/37) | -1.0 [-9.84, 7.83] | 1.0000 | 0.0 (0/27) | -3.7 [-10.83, 3.42] | 1.0000 |

| Negative | 18.9 (32/169) | 5.6 (9/160) | -13.3 [-20.21, -6.41] | 0.0003 | 2.2 (4/179) | -16.7 [-22.99. -10.41] | < 0.0001 |

The incidence of TEAEs during the 24-wk maintenance period was comparable between the maintenance treatment groups (Table 4). All-cause TEAEs during maintenance therapy were reported in 51.2%, 54.0%, and 58.8% of patients treated with lansoprazole 15 mg, vonoprazan 10 mg, and vonoprazan 20 mg, respectively. Nasopharyngitis was the most commonly reported TEAE in each treatment group (13.9%, 16.8%, and 13.2%, respectively; 14.7% of patients overall). The only other TEAE occurring in > 5% of patients in any treatment group was diarrhea, which was reported in 5.5% of those treated with lansoprazole 15 mg. TEAEs were mostly mild in severity. The incidence of drug-related TEAEs was 11.4%, 10.4%, and 10.3% with lansoprazole 15 mg, vonoprazan 10 mg and vonoprazan 20 mg, respectively. Very few serious TEAEs were reported with lansoprazole 15 mg, vonoprazan 10 mg, or vonoprazan 20 mg (4, 5, and 4 TEAEs, respectively); of the TEAEs reported, one case of atrial fibrillation and abnormal liver function test [elevated ALT and AST (303 U/L and 228 U/L, respectively)] in the vonoprazan 20 mg group were considered to be possibly related to the study drug. The abnormal liver function test was reported in a patient with a prior history of alcoholic hepatic steatosis, and led to his premature withdrawal from the study. As no specific cause was identified, a possible causal relationship with the study drug could not be ruled out.

| LPZ 15 mg (n = 201) | VPZ 10 mg (n = 202) | VPZ 20 mg (n = 204) | ||||

| Events | Patients | Events | Patients | Events | Patients | |

| Any TEAE | 166 | 103 (51.2) | 220 | 109 (54.0) | 212 | 120 (58.8) |

| Drug-related TEAE | 30 | 23 (11.4) | 26 | 21 (10.4) | 23 | 21 (10.3) |

| TEAE leading to study discontinuation | 10 | 8 (4.0) | 5 | 5 (2.5) | 8 | 8 (3.9) |

| Any serious TEAE | 4 | 4 (2.0) | 5 | 5 (2.5) | 4 | 4 (2.0) |

| Death | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) |

| TEAEs reported in ≥ 2% of patients in any group, irrespective of causal relationship to study medication, during maintenance treatment. | ||||||

| TEAE (preferred term) | LPZ 15 mg | VPZ 10 mg | VPZ 20 mg | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 28 (13.9) | 34 (16.8) | 27 (13.2) | |||

| Diarrhea | 11 (5.5) | 6 (3.0) | 5 (2.5) | |||

| Upper respiratory tract inflammation | 3 (1.5) | 8 (4.0) | 4 (2.0) | |||

| Elevated blood creatinine phosphokinase | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) | 6 (2.9) | |||

| Elevated blood triglycerides | 6 (3.0) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.5) | |||

| Fall | 1 (0.5) | 8 (4.0) | 2 (1.0) | |||

| Gastroenteritis | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.5) | 5 (2.5) | |||

| Back pain | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.5) | |||

| Constipation | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | |||

| Elevated ALT1 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | |||

| Contusion | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | |||

| Seasonal allergy | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | |||

| Bronchitis | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Dizziness | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | |||

| Abnormal liver function test2 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) | |||

| Abnormal hepatic function2 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | |||

| Periodontitis | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | |||

With regard to SIAEs, one case each of abnormal liver function test [elevated ALT (179 IU/L) and AST (209 IU/L) owing to fenofibrate treatment for dyslipidemia and elevated ALT (137 IU/L), which was not associated with any symptoms and was considered possibly related to the study medication] were reported in the lansoprazole 15 mg group, while two cases of abnormal liver function test were reported in the vonoprazan 10 mg group [elevated ALT (467 IU/L) and AST (571 IU/L) in one patient, which were considered possibly related to the study medication; and elevated ALT (326 IU/L) and AST (127 IU/L) that occurred in a patient with concurrent hepatic steatosis and were considered unrelated to the study drug]. In the vonoprazan 20 mg group, elevated ALT (86 IU/L) and AST (47 IU/L) were reported at the final study visit in a patient with concurrent hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis. Having completed the study, the patient began to receive lansoprazole as maintenance treatment for EE. Four weeks after the patient had completed the study, a further ALT elevation (139 IU/L) was reported, which qualified as a SIAE. Two days later, dark urine and itching were reported. The patient’s condition remained unresolved 2 mo later but, owing to the invasive nature of blood sampling, the investigator decided that further follow-up was unnecessary, and that the patient should receive routine medical care and further treatment as required. As the initial ALT and AST elevations had occurred during the maintenance period of the study, the possibility of a causal relationship with the study medication could not be ruled out. Also in the vonoprazan 20 mg group, elevated ALT (138 IU/L, which was considered to have been caused by pre-existing hepatic steatosis) was reported in one patient, and two cases of abnormal liver function test were noted; the first in a patient with ALT elevated to 161 IU/L following the consumption of a large quantity of alcohol, and the second being the case that is described above as a serious TEAE. All the SIAEs were considered resolved or resolving, with the exception of the case of abnormal hepatic function in the vonoprazan 20 mg group. This patient was followed up with routine medical care and treated as required.

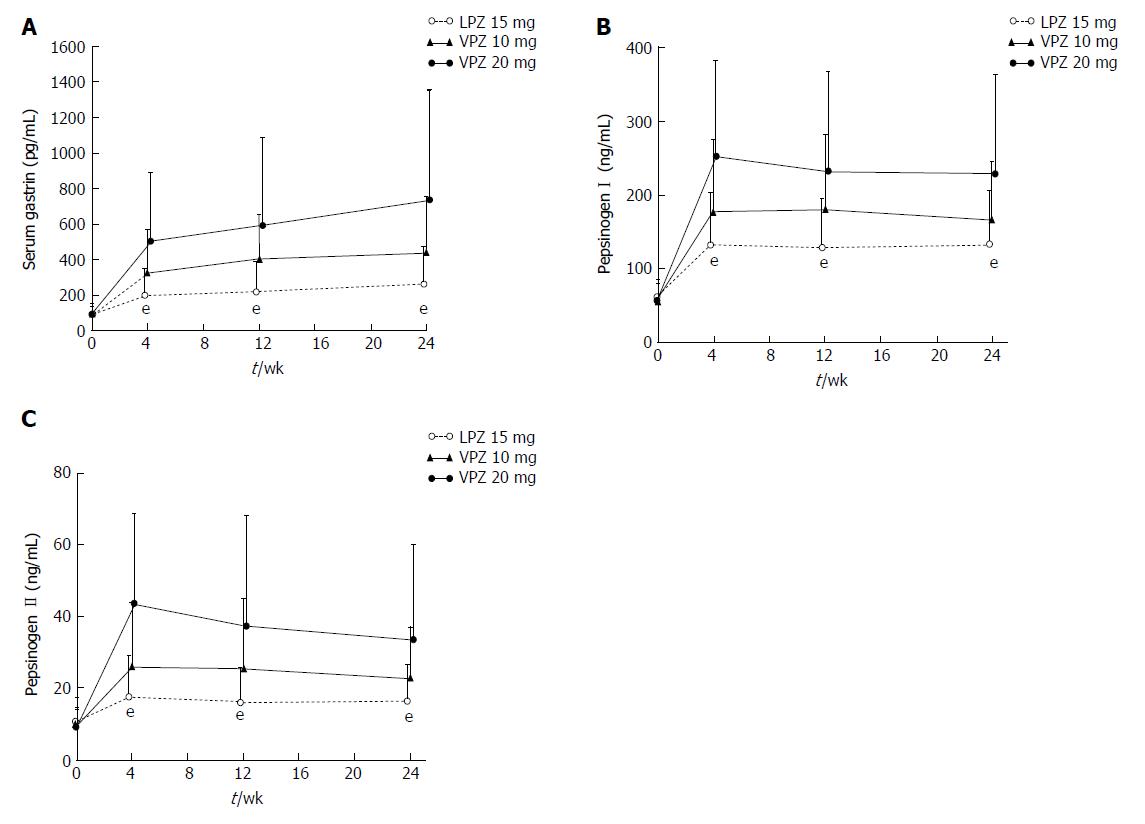

Mean levels of serum gastrin, pepsinogen I, and pepsinogen II increased in all three groups after the start of maintenance therapy; as shown in Figure 2, the increases were greatest with vonoprazan 20 mg and least with lansoprazole 15 mg. Histopathologic examinations showed that the observed increases in serum gastrin were not associated with clinically significant effects on the gastric mucosa. Similar slight increases in the number and density of Grimelius-positive cells were observed from baseline to Week 24 in all treatment groups (Table 5), leading to increased ratios of Grimelius-positive cells to epithelial cells. No clinically significant treatment-related changes were noted in gastric mucosal cell density, or in the percentage and density of chromogranin A-, synaptophysin-, and Ki-67-positive cells (Table 5).

| LPZ 15 mg | VPZ 10 mg | VPZ 20 mg | ||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Epithelial cells (× 103) | ||||||

| Baseline | 28 | 1.58 (0.4831) | 29 | 1.82 (0.3188) | 28 | 1.74 (0.3943) |

| Week 24 | 24 | 1.63 (0.2689) | 26 | 1.71 (0.4304) | 28 | 1.54 (0.4744) |

| Grimelius-positive cells (× 102) | ||||||

| Baseline | 28 | 0.716 (0.3997) | 29 | 0.705 (0.5562) | 28 | 0.656 (0.3778) |

| Week 24 | 24 | 1.06 (0.2676) | 26 | 1.07 (0.3858) | 28 | 0.943 (0.4260) |

| Chromogranin A-positive cells (× 102) | ||||||

| Baseline | 28 | 1.35 (0.6625) | 29 | 1.25 (0.7250) | 28 | 1.35 (0.7073) |

| Week 24 | 24 | 1.35 (0.2962) | 26 | 1.31 (0.4595) | 28 | 1.20 (0.5041) |

| Synaptophysin-positive cells (× 102) | ||||||

| Baseline | 28 | 1.73 (0.7005) | 29 | 1.73 (0.8123) | 28 | 1.83 (0.9076) |

| Week 24 | 24 | 1.58 (0.3716) | 26 | 1.55 (0.4490) | 28 | 1.45 (0.6173) |

| Ki-67-positive cells (× 102) | ||||||

| Baseline | 28 | 1.44 (0.8192) | 29 | 1.10 (0.6624) | 28 | 1.32 (0.5513) |

| Week 24 | 24 | 1.14 (0.5037) | 26 | 1.09 (0.4075) | 28 | 1.05 (0.4853) |

No clinically significant changes were observed in clinical laboratory test values, vital signs, or ECG findings in any group during maintenance treatment.

The findings of this study demonstrate the non-inferiority of once-daily maintenance therapy with vonoprazan 10 mg or 20 mg to lansoprazole 15 mg for the prevention of EE recurrence in Japanese patients with healed EE. The upper limits of 95%CI for the differences in EE recurrence rate between vonoprazan 10 mg or 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg at 24 wk of maintenance treatment were below 0, indicating a statistically significant difference.

The prevalence of EE has increased in Japan over the past few decades, owing to factors such as the adoption of a westernized lifestyle, the aging of the population, and the decreasing incidence of H. pylori infection[22]. Moreover, endoscopic EE remission rates after healing following PPI treatment have been shown to be markedly lower in patients with more severe (LA grades C/D) vs milder disease[23]. In the current study, recurrence rates in patients with baseline LA grade C/D EE were significantly reduced with vonoprazan 10 mg (13.2%) and 20 mg (4.7%) vs lansoprazole 15 mg (39.0%) (P = 0.0114 and P = 0.0001, respectively). In addition, treatment with both vonoprazan 10 mg and 20 mg reduced recurrence rates compared with lansoprazole 15 mg among CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers (5.4% and 1.8%, respectively, vs 19.6%). These findings support the hypothesis that vonoprazan provides clinical benefits through potent and sustained gastric suppression in difficult-to-treat EE subgroups with more severe disease, as well as in those with milder disease.

The doses of vonoprazan and lansoprazole selected for evaluation in this study were consistent with the doses of acid suppressants commonly used for the maintenance of healed EE. PPIs are well-established in this indication, typically being approved for administration at either the same or half the dose approved for the healing of EE[24-26]. As vonoprazan is an acid suppressant, we decided to evaluate both the clinically recommended dose for EE healing and half that dose as maintenance regimens in this study. Our group previously carried out a phase II dose-ranging study of vonoprazan in 732 Japanese patients with EE[27]. Vonoprazan, administered at once-daily doses of 5-40 mg, was found to be non-inferior to lansoprazole 30 mg once daily with respect to the rate of endoscopically-confirmed EE healing after 4 wk of treatment. Moreover, the rate of EE healing in patients with LA grade C/D EE was > 95% with vonoprazan doses of ≥ 20 mg, vs 87% with lansoprazole 30 mg. The safety profile of vonoprazan at all administered doses was similar to that of lansoprazole 30 mg. On the basis of these findings, 20 mg once daily was established as the clinically recommended dose of vonoprazan for the treatment of EE[27]. Therefore, the doses of vonoprazan evaluated as maintenance therapy in the present study were 20 and 10 mg once daily - representing the clinically recommended dose for the treatment of EE and half that dose. Lansoprazole was evaluated at the 15 mg dose that is approved for the maintenance of healed EE[26].

Vonoprazan 10 and 20 mg demonstrated similar safety profiles to lansoprazole 15 mg during the 24-wk maintenance period. All three investigated maintenance regimens were well tolerated overall, with only a small number of TEAE-related withdrawals reported in each group. No new safety signals were identified for vonoprazan during the study. The increase in serum gastrin that we observed was not associated with clinically significant effects on the gastric mucosa. This, as well as the observed increases in pepsinogen I and II, were likely a negative feedback effect caused by the increase in intragastric pH that resulted from treatment with lansoprazole or vonoprazan. Histopathology of the gastric mucosa revealed no notable effects of the study drugs on neuroendocrine cells between baseline and Week 24, although the study was too short to rule out the possibility of clinically significant histopathologic changes occurring in the gastric mucosa over the long term. Thus, longer-term studies (> 1 year) are required to monitor any potential effects of vonoprazan on gastric mucosa.

This study was limited by its relatively short duration; nevertheless, the findings reported in this paper build on those from prior studies by our group, which investigated the efficacy and safety of vonoprazan in patients with acid-related disorders. In addition to the aforementioned phase II dose-ranging study, which demonstrated the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 5-40 mg once daily to lansoprazole 30 mg once daily in terms of rates of EE healing over 4 wk[27], a recent phase III trial confirmed the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 20 mg to lansoprazole 30 mg in the same indication within an 8-wk period[18]. Vonoprazan was found to be highly effective even among CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers and patients with baseline EE of LA Classification grade C/D. Other studies have also shown promising results with vonoprazan in the treatment of gastric or duodenal ulcers[28], and in the prevention of recurrent ulcers of these types in patients receiving low-dose aspirin or NSAIDs (ClinicalTrials.gov. identifiers NCT01452763, NCT01456247, NCT01452750, and NCT01456260).

While the primary objective of the present study was to verify the non-inferiority of vonoprazan to lansoprazole, the two-sided 95%CI for the difference between each vonoprazan group and the lansoprazole group were calculated as pre-planned for the primary analysis. A post-hoc Fisher’s exact test was also performed as a sensitivity analysis to further support the results of the primary assessment using the CIs. These analyses confirmed that vonoprazan provided more consistent maintenance of EE healing at doses of 10 mg and 20 mg than lansoprazole 15 mg, even among CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers and patients with LA grade C/D EE. These findings suggest that vonoprazan may represent a viable alternative to PPIs in maintaining EE healing, with two doses being available for physicians to choose from.

In conclusion, this phase III trial confirmed the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 10 mg and 20 mg to lansoprazole 15 mg once daily in preventing EE recurrence during 24 wk of maintenance treatment in Japanese patients. The safety profile of vonoprazan at the administered doses was similar to that of lansoprazole 15 mg.

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as lansoprazole are widely accepted as the treatment of choice for acid-related disorders, including erosive esophagitis (EE). Nevertheless, agents of this class are associated with notable shortcomings, which include: significant inter-individual variability in the time to onset of action; reduced night-time efficacy in preventing acid regurgitation, leading to nocturnal acid breakthrough; and differences in plasma concentrations and acid-inhibitory effects in extensive versus poor CYP2C19 metabolizers.

Vonoprazan fumarate (TAK-438) belongs to a relatively new class of acid suppressants known as potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs), which, by virtue of their novel mechanism of action, offer a number of potential advantages over PPIs in the treatment of acid-related disorders. In animal studies, vonoprazan provided more potent and sustained suppression of gastric acid secretion than lansoprazole, while studies in healthy human volunteers demonstrated rapid, sustained, and dose-related suppression of 24-h gastric acid secretion. The present study adds to these earlier findings by confirming that vonoprazan is non-inferior to lansoprazole in preventing EE recurrence in Japanese patients with healed EE.

As a result of the increasingly widespread adoption of a westernized lifestyle and the general aging of the population, EE is now the most common acid-related disorder in Japan. Typical symptoms of EE include heartburn, acid reflux, difficulty swallowing, and sore throat, which can negatively impact patients’ quality of life. In Japan, as elsewhere, PPIs remain the mainstay of treatment for EE and other acid-related disorders; however, in view of the limitations of PPIs mentioned above, there is a need for new treatment modalities that offer greater efficacy and more consistent outcomes. Any treatments that improve outcomes in EE may also be beneficial in gastroesophageal reflux disease, duodenal ulcer, and other acid-related disorders, and could become the focus of a new area of research.

The main objective of the research described in this paper was to demonstrate that the efficacy of vonoprazan in preventing EE recurrence is comparable to that of lansoprazole at its established maintenance dose. This objective was realized, with the results obtained confirming that vonoprazan, at doses of 10 and 20 mg once daily, is non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg once daily as maintenance therapy for healed EE. In addition, the safety profile of vonoprazan was shown to be similar to that of lansoprazole at the doses investigated. These findings suggest that vonoprazan may be a viable alternative to PPIs in the maintenance of EE healing, and provide a basis for future clinical trials to establish the optimal positioning of this new agent in the treatment of acid-related disorders.

To establish the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 10 and 20 mg to lansoprazole 15 mg as maintenance therapy in Japanese patients with endoscopically-confirmed healed EE, we designed and conducted a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, phase III clinical trial. Eligible patients received vonoprazan 10 or 20 mg, or lansoprazole 15 mg, once daily for 24 wk. The primary and secondary endpoints were the rate of EE recurrence at Weeks 24 and 12, respectively; safety outcomes were also evaluated. Based on EE recurrence rates in previous studies, it was calculated that 174 patients per treatment group would be required to provide > 90% power to confirm the non-inferiority of vonoprazan 10 and 20 mg to lansoprazole 15 mg.

We found that vonoprazan, administered at a dose of 10 or 20 mg once daily, is non-inferior to lansoprazole 15 mg once daily in maintaining EE healing in Japanese patients over a period of 24 wk, and demonstrates a comparable safety profile. Post-hoc analyses also confirmed that both doses of vonoprazan investigated provide more consistent EE healing than lansoprazole, even in patients who are CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers and those with severe (Los Angeles grade C/D) EE. These results add to our previous findings that vonoprazan 5-40 mg once daily is non-inferior to lansoprazole 30 mg once daily in terms of EE healing rates over a 4-wk period, and that vonoprazan 20 mg once daily is non-inferior to lansoprazole 30 mg once daily in terms of 8-wk EE healing rates. As the maintenance period in this study was relatively short, further studies are needed to establish the long-term efficacy and safety characteristics of vonoprazan in the maintenance of EE healing.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to confirm that vonoprazan is non-inferior to lansoprazole once daily in maintaining EE healing in Japanese patients. Importantly, it is also the first to show that vonoprazan is more consistent in maintaining EE healing, even in extensive CYP2C19 metabolizers and patients with more severe disease. These findings appear to confirm that the novel mechanism of action of vonoprazan is associated with advantages versus PPIs in the treatment of acid-related disorders, and suggest that vonoprazan could be an important new addition to the range of treatment options available to clinicians.

This study confirms that vonoprazan demonstrates efficacy comparable with that of lansoprazole not only in healing EE, but also in maintaining the healing of EE over 24 wk. Future research should focus on evaluating the longer-term efficacy and safety of vonoprazan in this indication. In addition to randomized controlled trials, observational studies should be undertaken to gather valuable real-life data and inform decisions regarding the optimal positioning of vonoprazan in the management of EE.

The authors acknowledge all participating patients and their families, as well as all staff at the 55 investigational sites. The authors also acknowledge Sandralee Lewis PhD, working on behalf of FireKite (an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc), who provided medical writing assistance during the development of this manuscript, which was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited and complied with Good Publication Practice 3 ethical guidelines (Battisti et al. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 461-4 [PMID: 26259067]). The results of the study were previously presented at the Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2014, and at the Japanese Digestive Disease Week (JDDW) 2014.

| 1. | Maradey-Romero C, Fass R. New and future drug development for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:6-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Pace F, Tonini M, Pallotta S, Molteni P, Porro GB. Systematic review: maintenance treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease with proton pump inhibitors taken ‘on-demand’. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:195-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Hershcovici T, Fass R. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: beyond proton pump inhibitor therapy. Drugs. 2011;71:2381-2389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Fass R. Alternative therapeutic approaches to chronic proton pump inhibitor treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:338-345; quiz e39-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Hungin AP, Hill C, Molloy-Bland M, Raghunath A. Systematic review: Patterns of proton pump inhibitor use and adherence in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R, Sewell J. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--where next? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | El-Serag H, Becher A, Jones R. Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:720-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (40)] |

| 8. | Andersson K, Carlsson E. Potassium-competitive acid blockade: a new therapeutic strategy in acid-related diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:294-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Cederberg C, Lind T, Röhss K, Olbe L. Comparison of once-daily intravenous and oral omeprazole on pentagastrin-stimulated acid secretion in duodenal ulcer patients. Digestion. 1992;53:171-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Dammann HG, Burkhardt F. Pantoprazole versus omeprazole: influence on meal-stimulated gastric acid secretion. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1277-1282. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Shin JM, Inatomi N, Munson K, Strugatsky D, Tokhtaeva E, Vagin O, Sachs G. Characterization of a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker of the gastric H,K-ATPase, 1-[5-(2-fluorophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]-N-methylmethanamine monofumarate (TAK-438). J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:412-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Hori Y, Imanishi A, Matsukawa J, Tsukimi Y, Nishida H, Arikawa Y, Hirase K, Kajino M, Inatomi N. 1-[5-(2-Fluorophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]-N-methylmethanamine monofumarate (TAK-438), a novel and potent potassium-competitive acid blocker for the treatment of acid-related diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:231-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Matsukawa J, Hori Y, Nishida H, Kajino M, Inatomi N. A comparative study on the modes of action of TAK-438, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, and lansoprazole in primary cultured rabbit gastric glands. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:1145-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Hori Y, Matsukawa J, Takeuchi T, Nishida H, Kajino M, Inatomi N. A study comparing the antisecretory effect of TAK-438, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, with lansoprazole in animals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:797-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, Kennedy G, Hibberd M, Jenkins R, Okamoto H, Yoneyama T, Jenkins H, Ashida K, Irie S. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of Single Rising TAK-438 (Vonoprazan) Doses in Healthy Male Japanese/non-Japanese Subjects. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Jenkins H, Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, Okamoto H, Hibberd M, Jenkins R, Yoneyama T, Ashida K, Ogama Y, Warrington S. Randomised clinical trial: safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of repeated doses of TAK-438 (vonoprazan), a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:636-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Lauritsen K, Devière J, Bigard MA, Bayerdörffer E, Mózsik G, Murray F, Kristjánsdóttir S, Savarino V, Vetvik K, De Freitas D. Esomeprazole 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg in maintaining healed reflux oesophagitis: Metropole study results. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17 Suppl 1:24; discussion 25-24; discussion 27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Ashida K, Sakurai Y, Hori T, Kudou K, Nishimura A, Hiramatsu N, Umegaki E, Iwakiri K. Randomised clinical trial: vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, vs. lansoprazole for the healing of erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:240-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Kahrilas PJ, Dent J, Lauritsen K, Malfertheiner P, Denison H, Franzén S, Hasselgren G. A randomized, comparative study of three doses of AZD0865 and esomeprazole for healing of reflux esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1385-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Endo M, Sugihara K. [Long-term maintenance treatment of reflux esophagitis resistant to H2-RA with PPI (lansoprazole)]. Nihon Rinsho. 2000;58:1865-1870. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Farrington CP, Manning G. Test statistics and sample size formulae for comparative binomial trials with null hypothesis of non-zero risk difference or non-unity relative risk. Stat Med. 1990;9:1447-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 486] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:518-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Higuchi K, Joh T, Nakada K, Haruma K. Is proton pump inhibitor therapy for reflux esophagitis sufficient?: a large real-world survey of Japanese patients. Intern Med. 2013;52:1447-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | AstraZeneca Company. NEXIUM prescribing information. Accessed July 12. 2017; Available from: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/pack/2329028F1023_1_28/. |

| 25. | Eisai Company Limited. Pariet prescribing information. Accessed July 12. 2017; Available from: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/pack/2329029M1027_1_09/. |

| 26. | Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Takepron prescribing information. Accessed July 12. 2017; Available from: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/pack/2329023M1020_1_23/. |

| 27. | Ashida K, Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, Kudou K, Hiramatsu N, Umegaki E, Iwakiri K, Chiba T. Randomised clinical trial: a dose-ranging study of vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, vs. lansoprazole for the treatment of erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:685-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Miwa H, Uedo N, Watari J, Mori Y, Sakurai Y, Takanami Y, Nishimura A, Tatsumi T, Sakaki N. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy and safety of vonoprazan vs. lansoprazole in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers - results from two phase 3, non-inferiority randomised controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:240-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Data-sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chiba T, Esmat S, Kim GH, Jonaitis LV, Shimatani T S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y