Published online Aug 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5994

Peer-review started: May 28, 2017

First decision: June 23, 2017

Revised: June 29, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: August 28, 2017

Processing time: 93 Days and 13.5 Hours

To performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine any possible differences in terms of effectiveness, safety and tolerability between existing colon-cleansing products in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Systematic searches were performed (January 1980-September 2016) using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, CENTRAL and ISI Web of knowledge for randomized trials assessing preparations with or without adjuvants, given in split and non-split dosing, and in high (> 3 L) or low-volume (2 L or less) regimens. Bowel cleansing quality was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included patient willingness-to-repeat the procedure and side effects/complications.

Out of 439 citations, 4 trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria (n = 449 patients). One trial assessed the impact of adding simethicone to polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4 L with no effect on bowel cleansing quality, but a better tolerance. Another trial compared senna to castor oil, again without any differences in term of bowel cleansing. Two trials compared the efficacy of PEG high-volume vs PEG low-volume associated to an adjuvant in split-dose regimens: PEG low-dose efficacy was not different to PEG high-dose; OR = 0.84 (0.37-1.92). A higher proportion of patients were willing to repeat low-volume preparations vs high-volume; OR = 5.11 (1.31-20.0).

In inflammatory bowel disease population, PEG low-volume regimen seems not inferior to PEG high-volume to clean the colon, and yields improved willingness-to-repeat. Further additional research is urgently required to compare contemporary products in this population.

Core tip: This is the first meta-analysis addressing the issue of bowel preparations in Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients aiming to determine any differences in terms of effectiveness, safety and tolerability between existing colon-cleansing products. This work is especially timely considering that colonoscopy is used frequently in IBD patients for both diagnosis and surveillance, and that recommendation on how to prepare these patients prior to colonoscopy are based mostly on expert opinion. The results suggest that low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) preparation with adjuvants in split-dosing may represent a valid alternative to standard high-volume PEG with at least a similar efficacy and better acceptability.

- Citation: Restellini S, Kherad O, Bessissow T, Ménard C, Martel M, Taheri Tanjani M, Lakatos PL, Barkun AN. Systematic review and meta-analysis of colon cleansing preparations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(32): 5994-6002

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i32/5994.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5994

Adequacy of the bowel preparation is one of the most important predictors of colonoscopic quality[1]. Recent guidelines in bowel preparations strongly endorse the use of split-dose regimens, irrespective of the type of product, as this regimen results in greater proportions of patients with adequate preparation[2]. However, many specific clinical situations need to be explored as some patients requiring specific considerations are often excluded in clinical trials because of safety concerns.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), consisting of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), is an increasingly prevalent intestinal disorder with significant co-morbidities[3]. Colonoscopy is used frequently in this patient population for both diagnosis and surveillance as patients with UC and extensive colonic CD, are at a higher risk of developing colonic malignancy after 8-10 years of disease[4].

Safety is also a major concern in this population as bowel-preparation-induced mucosal inflammation has been reported[5]. This risk seems higher with sodium phosphate (Nap) and picosulfate (PICO) than with polyethylene glycol (PEG)[6]. Erosions, aphthoid lesions (ulcer < 5 mm), and ulcers (> 5 mm) as result of the preparation are often multiple[7]. Some UC patients have also reported flare symptoms after colonoscopy[8]. Furthermore, IBD patients with inadequate levels of bowel cleansing may need examinations rescheduled which may increase anxiety and interfere with follow-up that is critical in their clinical management[9]. Some publications have found that IBD patients reported low satisfaction from the bowel preparation compared to other patients, while personal and anecdotal experiences suggests increased difficulty with bowel preparation in some patients with IBD[10].

Unfortunately, only few data exist on colonoscopy preparations in IBD patients[11-13]; the recommendations of how to prepare these patients prior to colonoscopy are thus based mostly on expert opinions[4,14-17]. The aim of this systematic review was to summarize available evidence in order to determine any existing differences in effectiveness, willingness-to-repeat, and safety between contemporary colon-cleansing products in the IBD population.

Systematic searches were performed (January 1980-September 2016) using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, CENTRAL and ISI Web of knowledge. Citation selection utilized a highly sensitive search strategy identifying randomized trials[18] with MeSH headings relating to (1) colonoscopy; (2) gastrointestinal agents; (3) bowel preparation; (4) generic and brand names; and (5) IBD (Annex 1). Recursive searches, cross-referencing and subsequent hand-searches were completed.

All fully published randomized trials in French or English with at least one arm administering a product as defined as PEG, NAP, PICO, or OSS (oral sulfate sodium) in a study population made up exclusively of IBD patients were included. Trials comprising pediatric and in-patients were also included. Authors of unpublished abstracts were contacted in order to access the full paper.

The primary outcome measure was bowel cleanliness defined as the proportion of patients with an adequate preparation. Secondary outcomes were patient willingness-to-repeat the preparation, as a proxy for patient tolerance and satisfaction, as well as polyp or adenoma detection rates and side effects or complications (flare of disease, increase in SCALL score, ulceration).

Two investigators assessed citation eligibility with discrepancies resolved by an independent reviewer. Quality of trials were graded using the Cochrane risk bias tool and Jadad score[19] (with, one extra point for reported a priori sample size calculations).

Possible sources of clinical heterogeneity were noted across trials in keeping with pre-planned sensitivity or subgroup analyses. Identification and handling of statistical heterogeneity is described below.

For each outcome and in every comparison, effect size was calculated as odds ratios for categorical variables and weighted mean differences (WMDs) for continuous variables. The Mantel-Haenszel method for fixed effect models determined corresponding overall effect sizes with confidence intervals, except when statistical heterogeneity was noted in which case a random-effects model was used according to the DerSimonian and Laird method[20]. WMDs were manipulated using the inverse variance approach. Statistical heterogeneity across studies was defined using a χ2 test of homogeneity with 0.10 significance level. The Higgins I2 statistic was calculated to quantify the proportion of variation in treatment effects attributable to between-study heterogeneity[21].

Values for intention-to-treat (ITT) were preferred to per protocol when both were presented. We included non-compliant patients or withdrawals in the ITT analysis to minimize bias[22]. Publication bias was evaluated by assessing the funnel plots, if more than 3 studies were to be included in the meta-analysis.

All percentages of outcomes reported in the trials were converted to absolute numbers and no attempt at determining extractable values from graphics or figures was undertaken to avoid possible subjectivity.

All statistical analyses were completed using Meta package in R version 2.13.0, (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2008) and Review Manager Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

We adopted the terminology of no difference purposefully rather than using possibly misleading or statistically incorrect terminologies such as non-inferiority or equivalence.

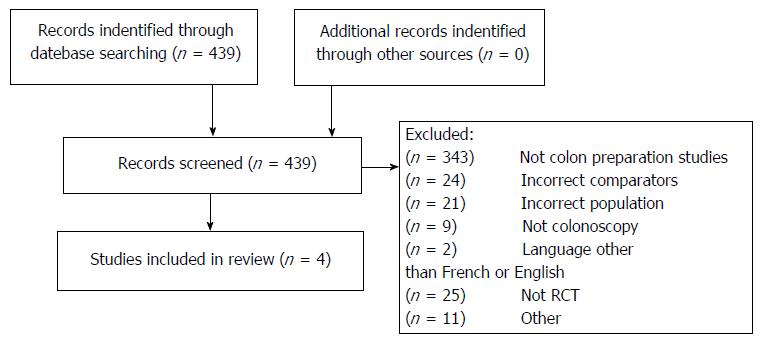

Out of 43 citations, 4 trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria (n = 449 patients)[12,13,23,24] (Figure 1 and Table 1). Twenty-five citations were excluded as they were not randomized controlled trials; 352 did not assess colonoscopy or bowel preparations, 24 had incorrect comparators, 21 an incorrect patient population, 2 were published in another language than French or English and 11 for other reasons such as one was not fully published and the abstract’s authors did not respond to our query[25].

| Ref. | Arm1 | Arm 2 | Overall IBD type | Time of endoscopy |

| Time to FD and LD to endoscopy | Time to FD and LD to endoscopy | |||

| Gould et al[23] 1982 (United Kingdom) | Castor oil 30 min (n = 23) | Senna 75 mg (n = 23) | RCH = 46 | - |

| outpatient elective | LD: 24 h before | LD: 24 h before | CD = 0 | |

| Score: 3 | Active disease = 7 | |||

| Lazzaroni et al[12] 1993 (Italy) | PEG 4 L + placebo (n = 56) | PEG 4 L + simethicone 120 mg (n = 59) | RCH = 61 | - |

| outpatient elective | FD: 2 L afternoon before | FD: 2L afternoon before | CD = 44 | |

| Score: 4 | LD: 2 L 6 am day of | LD: 2L 6 am day of | Active disease = 0 | |

| Manes et al[13] 2015 (Italy) | PEG 4 L (n = 108) | PEG 2 L + bisacodyl 10 mg (n = 108) | RCH = 216 | Between 8 am and 2 pm |

| outpatient elective | Whole dose (n = 48) | Whole dose (n = 35) | CD = 0 | |

| Score: 5 | FD: 4 pm day before | FD: 4 pm day before | Active disease = 116 | |

| Split dose (n = 60) | Split dose (n = 73) | |||

| FD: 2 L day before | FD: 2 L day before | |||

| LD: 2 L between 5 am and 7 am day of | LD: 2 L between 5 am and 7 am day of | |||

| Kim et al[24] 2017 (Korea) | PEG 4 L (n = 55) | PEG 2 L + ascorbate (n = 57) | RCH = 112 | Between 9 am and 5 pm |

| outpatient elective | FD: 2 L 8 pm day before; LD: 2 L morning day of | FD: 2 L 8 pm day before, LD: 2 L morning day of | CD = 0 | |

| Score: 5 | If colonoscopy scheduled in the afternoon, 4 L between 6 am and 8 am | If colonoscopy scheduled in the afternoon, 4 L between 6 am and 8 am | Active disease = 0 |

Moderate to strong heterogeneity was noted for the main outcome analyses. Publication bias was observed across the main outcome analyses.

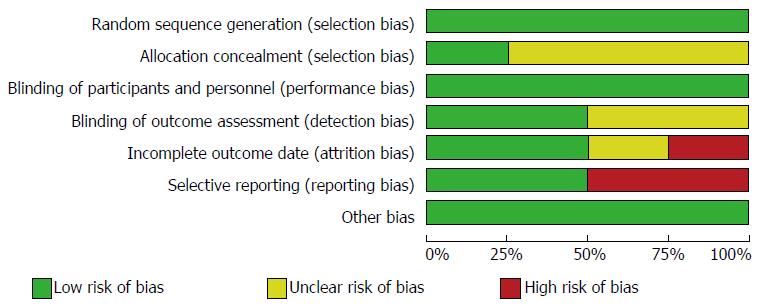

The Jadad modified quality scores ranged from 0 to 6 points (mean of 4.3 ± 1.0). The Cochrane risk bias tool revealed a low potential for selection bias across studies for detection, attrition, reporting and other bias. Selection bias was unclear for several trials as the random sequence generation and allocation concealment was not described. Performance bias was high as the majority of the trials were single blinded (the endoscopist) (Figure 2).

All four trials (n = 449) assessed the bowel cleanliness specifically in an IBD population (Table 2). One trial[12] assessed the impact of the addition of Simethicone to PEG 4 L with no effect on bowel cleansing quality. However, the addition of simethicone showed a significant reduction in the formation of bubbles. Gould et al[23] 1982 compared the efficacy of the equivalent of 75 mg of senna to castor oil with no difference demonstrated between the two preparations.

| Numbers of studies | ITT patients | OR (95%CI) | Heterogeneity P value | I2 | |

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Bowel cleanliness | 2 | 325 | 1.19 (0.52-2.71) | 0.27 | 19% |

| Secondary outcome | |||||

| Willingness to repeat | 2 | 320 | 5.11 (1.31-20.00) | 0.03 | 78% |

| Procedure related outcome | |||||

| Rates of cecal intubation | 2 | 320 | 0.91 (0.32-2.53) | 0.54 | 0% |

| Mayo endoscopic score = 0 | 2 | 320 | 1.09 (0.69-1.70) | 0.38 | 0% |

| Mayo endoscopic score = 1 | 2 | 320 | 0.84 (0.54-1.33) | 0.61 | 0% |

| Mayo endoscopic score = 2 | 1 | 109 | 1.17 (0.46-3.00) | - | - |

| Mayo endoscopic score = 3 | 2 | 320 | 2.89 (0.30-28.24) | 1.00 | 0% |

| Side effects or complications | |||||

| Flare of disease | 1 | 109 | 0.62 (0.10-3.85) | - | - |

| Increase SCAII score | 1 | 109 | 1.14 (0.47-2.75) | - | - |

| Dizziness | 1 | 109 | 1.44 (0.23-9.00) | - | - |

| Abdominal pain/cramps | 1 | 109 | 0.30 (0.03-3.01) | - | - |

| Bloating | 1 | 109 | 0.72 (0.26-1.98) | - | - |

| Nausea | 1 | 109 | 0.39 (0.16-0.94) | - | - |

| Vomiting | 1 | 109 | 0.55 (0.17-1.81) | - | - |

| Insomnia | 1 | 109 | 1.72 (0.70-4.23) | - | - |

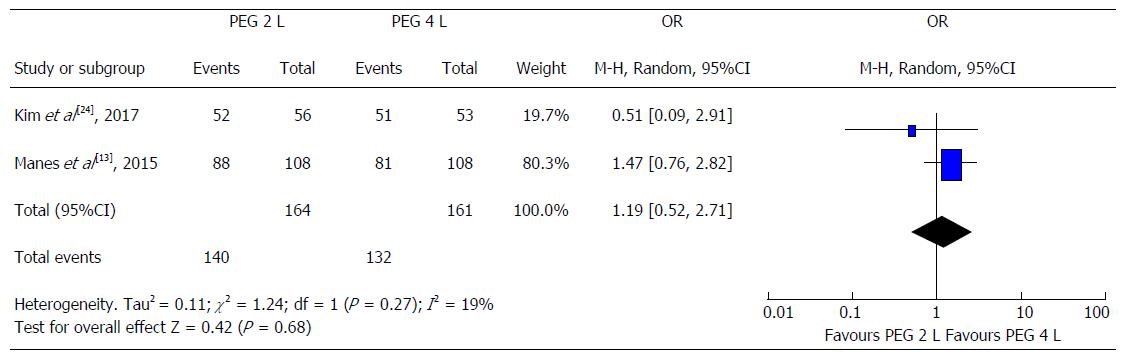

Two studies compared the efficacy of PEG high-volume (4 L) vs PEG low-volume (2 L) with an adjuvant, both mainly in split regimens. Manes et al[13] 2015 assessed the efficacy of a low-dose iso-osmotic preparation based on low-dose PEG (2 L) associated to bisacodyl vs a PEG high-volume (4 L) preparation alone. The quality of colon cleansing was similar in the two groups (83% vs 75%, P = 0.37). Of note, simethicone was added to PEG low-volume with bisacodyl. Kim et al[24] 2017 compared 4 L PEG with 2 L PEG plus ascorbic acid in terms of efficacy in patients with inactive UC. Successful cleansing was equally achieved in most patients from both groups with no significant differences noted (96.2% vs 92.9%, P = 0.67)[24]. In an analysis restricted to a comparison between PEG high-volume to PEG low-volume with adjuvant in split dose regimens, there was no clinically relevant difference in bowel preparation irrespective of the type of adjuvant used [OR = 0.84 (0.37-1.92)] (Figure 3).

Three studies reported the willingness-to-repeat the same preparation as a proxy of acceptance with only two studies with analyzable data (n = 320)[13,24]. The drug combination of PEG with simethicone induced a significantly better acceptance among patients when compared with the use of PEG plus placebo[12]. Manes et al[13] 2015 reported that willingness to repeat the same preparation in case of a new endoscopy was higher in PEG low-volume plus bisacodyl vs PEG high-volume alone (94.3% vs 61.9%, P < 0.001). In the study of Kim et al[24]. 2017, participants in the PEG low-volume with ascorbate group reported that they were more willing to repeat bowel preparation with the same agent for the future colonoscopy than those in the PEG high-volume (4 L) group (82.1% vs 64.2%, respectively, P = 0.034)[24].

In a pooled analysis restricted to comparison between PEG high-volume vs PEG low-volume, a significant higher proportion of patients were willing to repeat low-volume preparations with adjuvants vs high-volume; OR 5.11 (1.31-20.0).

Side effects were reported in all studies but with different patterns and classifications, precluding meta-analysis. Globally, severe side effects such as flare of disease in IBD patients undergoing colonoscopy were very uncommon without significant differences between different preparations as reported in the 4 studies. Gould et al[23] 1982 failed to incriminate castor oil as a more likely cause of exacerbation of colitis than an equally effective dose of senna. On the contrary, bowel disturbances were more common following senna than castor oil (48% vs 26%). Of note, authors used high doses of senna (equivalent of 75 mg). Lazzaroni et al[12] 1993 reported significantly better results for patients treated with the drug combination of PEG plus simethicone regarding reduction of general malaise (19% vs 44%, P = 0.01) and sleep disturbances (19% vs 44%, P = 0.01). Manes et al[13] 2015 noted that PEG low-volume (2 L) with bisacodyl was better tolerated than PEG high-volume (4 L) as evidenced by a significantly higher number of patients who described no or mild discomfort (83% vs 44.8%, P < 0.001). No severe adverse events were reported in the 2 groups. In the study by Kim et al[24]. 2017, overall adverse events during preparation were observed more frequently in the PEG high-volume group than in the PEG low-dose plus ascorbate, although the difference was not statistically significant (50.9% vs 36.4%, respectively, P = 0.127). However, patients in the PEG high-volume group reported significantly more nausea than those in the PEG low-volume plus ascorbate (35.8% vs 17.9%, respectively, P = 0.034). Finally, no study reported the polyp or adenoma detection rates or dysplasia findings.

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize existing evidence on bowel cleansing, specifically in IBD patients. Surprisingly, only four randomized controlled studies specifically addressed bowel cleansing in this important patient population, precluding any firm conclusions. The main results suggest that PEG-based preparations appear safe in IBD patients, with equivalent efficacy when comparing PEG low-volume vs PEG high-volume in split and non-split regimens, yielding improved tolerance for the former. Adjuvant therapies (osmotic and stimulant laxatives) were systematically associated to low-volume preparation without safety concerns. Severe side effects such as flare of the disease or preparation-induced ulcerations occurred in less than < 6%[23,24].

The majority of included studies utilized PEG-based preparations, reflecting current practice guidelines that support the use of this safe solution for bowel cleansing in patients with IBD[4,14,16,17]. Indeed, PEG preparations that are non-absorbable iso-osmotic solutions, minimizing the water and electrolytes imbalance, have long been proven to be well tolerated even in frail populations such as the elderly or patients with chronic kidney disease[26,27]. Interestingly, none of the existing society recommendations provide any guidance about the use of low-volume preparations in an IBD population[14,16,17]. In a general population undergoing colonoscopy, low-volume PEG preparations have been introduced to improve tolerability and acceptability before colonoscopy[2]. The pooled analysis in this current study meta-analysis in IBD patients that includes the two most recently published studies on the topic suggests that PEG low-volume preparations are equivalent to PEG high-volume when associated to an adjuvant [OR = 0.84 (0.37-1.92)], while yielding improved tolerance as patient were more willing to repeat the low-volume preparation OR 5.11 (1.31-20.0). Of note, the majority of patients in these two studies took the preparations in a split-dose regimen with a better efficacy on bowel cleansing. Professional guidelines addressing the IBD population recommend the use of split-dose preparations based on the overwhelming evidence in non IBD populations[2,17]. However, caution is advised in patients with partial bowel obstruction, gastroparesis, or known delayed intestinal motility, because of an increased risk for gastric retention and aspiration[17].

Furthermore, PEG low-volume preparations were systematically associated with an adjuvant. They were based on the combination of 2-L PEG with a stimulant laxative (bisacodyl), or an osmotically active agent (ascorbic acid). The impact of adjuvants on bowel preparations remains debated, with differing US and European society recommendations, but a recent meta-analysis suggests that adjuvants may improve tolerance when used with low-volume PEG preparations[28]. PEG low-dose associated to either bisacodyl or ascorbate may thus represent a potentially ideal low-volume cleansing product for patients with IBD[16]. Furthermore, simethicone remains an interesting adjuvant, decreasing luminal bubbles as reported by Lazzaroni et al[12] 1993 in IBD patients mirroring same results in overall population[12,29]. Society guidelines are disparate on this topic[14,16] but a recent meta-analysis suggest the addition of simethicone may further improve bowel preparation quality[28].

There is always a trade-off between cleansing efficacy and tolerance, especially when comparing high- to low-dose preparations[30]. In general population, PEG high-volume leads to cleaner preparations compared to PEG low-volume with an adjuvant when restricting the analysis to split-dosing, but with a lower tolerance[28]. Compliance may be limited by the inability of patients to ingest such a large volume of solution. Tolerability and compliance with bowel preparations are however both crucial particularly in patients with IBD. Indeed, IBD patients require repeated colonoscopies throughout their lifetime, so that a bad experience with the preparation may affect the acceptability and uptake of future colonoscopy, particularly in IBD surveillance protocols[17]. Conversely, mucosal findings in IBD such as dysplastic and non-polypoid flat lesions may be very subtle and can be detected only in a perfectly prepared colon[4], with the assistance of chromoendoscopy[31]. Further studies comparing high-volume vs low-volume preparations in split-dosing, including more contemporary one such as PICO are urgently needed. Meanwhile, clinicians should probably engage the discussion with the patient in a shared decision process in order to choose between an effective high-volume preparation or a more acceptable low-volume on a case-by-case basis.

Safety is also an important issue to be considered when prescribing a preparation for colonoscopy in IBD. Indeed, some procedures are performed in patients suffering from severe symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal pain with possible preexisting electrolytic imbalances. Patients with IBD may develop complications either from the colonoscopy or from the cleansing procedure[13]. These patients experience significantly more embarrassment and burden during the preparation when compared with patients undergoing colonoscopy for other indications[9]. Furthermore, clinicians periodically express concern that bowel preparation may precipitate a relapse of colitis, based on personal experience[17]. Additionally the preparation may cause ulcerations that can mimic IBD-related mucosal lesions, interfering with correct disease diagnosis and staging[17]. Bowel preparations may indeed induce colonic mucosal damage through crypt cell apoptosis and increased oxidative stress[32,33]. Reassuringly, side effects reported in this systematic review were not more frequent than in the general population, and were severe in < 6%[23,24]. Relapse of colitis of flare of the disease requiring corticosteroid therapy occurred after colonoscopy in 2% to 4% and is often self-limited[24]. This inconvenient side effect was mostly reported with Nap that has been removed from market anyway due to rare but significant renal toxicity, particularly in patients with kidney failure[34]. Nap was indeed significantly associated with colonic mucosal inflammation suggesting it may have a transient role in provoking relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis[32,33] and causing IBD-like mucosal damage[17].

The limited number of published randomized controlled studies represents a critical issue precluding firm conclusions from this meta-analysis. The lack of research in bowel preparation in inflammatory colonic conditions is surprising, as colonoscopy plays a key role in the management of IBD patients. Furthermore, it should be noted that the majority patients included in these studies had quiescent or relatively inactive colitis and that colonoscopies were usually undertaken electively in the context of cancer screening. Furthermore, patients with CD were almost absent in these studies, including fistulizing or stenotic diseases, limiting the generalizability of results to this subgroup population. It remains unclear whether PEG-based preparations can be administered to patients with more active disease in whom tap water enemas may represent an alternative for what is often a partially empty colon[35] .

Notwithstanding the limited published data, our results confirm that PEG preparations can be used in a safe manner in patients with UC. Side effects were not more frequent than in the general population. In patients without contraindications, low-volume PEG preparation with adjuvants in split-dosing may represent a valid alternative to standard high-volume PEG with at least a similar efficacy and a better acceptability. Further research is required comparing low-dose contemporary products in this specific patient population, particularly patients with CD, so that the most adequate preparation can be chosen and authoritative recommendations can be confidently issued, based on best evidence.

Adequacy of the bowel preparation is one of the most important predictors of colonoscopic quality. Colonoscopy is performed frequently in an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient population for both diagnosis and surveillance as these patients are at higher risk of developing a colonic malignancy. Recommendations on how to prepare these patients prior to colonoscopy are based mostly on expert opinion.

Recent guidelines endorse the use of split-dose regimens preparations before colonoscopy, but only few data are available in IBD patients who are often excluded from trials for safety concerns.

This is the first meta-analysis addressing the issue of bowel preparations in IBD patients aiming to determine any differences in terms of effectiveness, safety and tolerability between existing colon-cleansing products.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) preparation with adjuvants in split-dosing may represent a valid alternative to standard high-volume PEG with at least similar efficacy and better acceptability. However, the limited number of published randomized controlled studies precludes firm conclusions and further research is required comparing low-dose contemporary products in an IBD population, so that the most adequate preparation can be chosen and authoritative recommendations can be confidently issued, based on best evidence.

Split dose refers to administration of half of the preparation the evening prior the colonoscopy and the second half the morning of the colonoscopy.

This is an interesting article that the authors made a study to review and meta-analyze colon cleansing preparations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease IBD. They concluded that in patients without contraindications, low-volume PEG preparation with adjuvants in split-dosing may represent a valid alternative to standard high-volume PEG with at least a similar efficacy and a better acceptability.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lee HC, Tang Y, Specchia ML S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797-1802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Martel M, Barkun AN, Menard C, Restellini S, Kherad O, Vanasse A. Split-Dose Preparations Are Superior to Day-Before Bowel Cleansing Regimens: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:79-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Chao CY, Battat R, Al Khoury A, Restellini S, Sebastiani G, Bessissow T. Co-existence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease: A review article. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7727-7734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 4. | American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee, Shergill AK, Lightdale JR, Bruining DH, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fonkalsrud L, Foley K, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Sharaf R, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1101-1121.e1-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Thoreson R, Cullen JJ. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:575-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lawrance IC, Willert RP, Murray K. Bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: prospective randomized assessment of efficacy and of induced mucosal abnormality with three preparation agents. Endoscopy. 2011;43:412-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rejchrt S, Bures J, Siroký M, Kopácová M, Slezák L, Langr F. A prospective, observational study of colonic mucosal abnormalities associated with orally administered sodium phosphate for colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:651-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Menees S, Higgins P, Korsnes S, Elta G. Does colonoscopy cause increased ulcerative colitis symptoms? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bessissow T, Van Keerberghen CA, Van Oudenhove L, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G. Anxiety is associated with impaired tolerance of colonoscopy preparation in inflammatory bowel disease and controls. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e580-e587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Denters MJ, Schreuder M, Depla AC, Mallant-Hent RC, van Kouwen MC, Deutekom M, Bossuyt PM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Patients’ perception of colonoscopy: patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome experience the largest burden. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:964-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Terheggen G, Lanyi B, Schanz S, Hoffmann RM, Böhm SK, Leifeld L, Pohl C, Kruis W. Safety, feasibility, and tolerability of ileocolonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2008;40:656-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lazzaroni M, Petrillo M, Desideri S, Bianchi Porro G. Efficacy and tolerability of polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage solution with and without simethicone in the preparation of patients with inflammatory bowel disease for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:655-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Manes G, Fontana P, de Nucci G, Radaelli F, Hassan C, Ardizzone S. Colon Cleansing for Colonoscopy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Efficacy and Acceptability of a 2-L PEG Plus Bisacodyl Versus 4-L PEG. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2137-2144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Boland CR, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:903-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, Orchard T, Rutter M, Younge L. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1045] [Cited by in RCA: 965] [Article Influence: 64.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Polkowski M, Rembacken B, Saunders B, Benamouzig R, Holme O, Green S, Kuiper T. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Nett A, Velayos F, McQuaid K. Quality bowel preparation for surveillance colonoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is a must. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:379-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309:1286-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1668] [Cited by in RCA: 1409] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 13031] [Article Influence: 434.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 20. | Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5737] [Cited by in RCA: 5090] [Article Influence: 118.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 26901] [Article Influence: 1120.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:670-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1512] [Cited by in RCA: 1480] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gould SR, Williams CB. Castor oil or senna preparation before colonoscopy for inactive chronic ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1982;28:6-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim ES, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim EY, Lee YJ, Lee HS, Jeon SW, Kim HJ, Kim SK; Crohn’s and Colitis Association in Daegu-Gyeongbuk (CCAiD). Comparison of 4-L Polyethylene Glycol and 2-L Polyethylene Glycol Plus Ascorbic Acid in Patients with Inactive Ulcerative Colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kato S, Kani K, Kobayashi T, Yamamoto R, Nagoshi S, Yakabi K. SU 1538 The Safety and Feasibility Study of Bowel Cleaning Agents MoviPrep Versus Niflec for the Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Undergoing Colonoscopy and Balloon Enteroscopy: a Single Center Randomized Controlled Trial. In: Endosc G, editor DDW, 2015. . |

| 26. | DiPalma JA, Brady CE 3rd, Pierson WP. Colon cleansing: acceptance by older patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:652-655. [PubMed] |

| 27. | DiPalma JA, Brady CE 3rd, Stewart DL, Karlin DA, McKinney MK, Clement DJ, Coleman TW, Pierson WP. Comparison of colon cleansing methods in preparation for colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:856-860. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Restellini S, Kherad O, Menard C, Martel M, Barkun AN. Do adjuvants add to the efficacy and tolerance of bowel preparations? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2017; Epub ahead of print. |

| 29. | Wu L, Cao Y, Liao C, Huang J, Gao F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of Simethicone for gastrointestinal endoscopic visibility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:227-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 30. | Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, Tierney A, Fennerty MB. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1225-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, McQuaid KR, Subramanian V, Soetikno R; SCENIC Guideline Development Panel. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:489-501.e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Watts DA, Lessells AM, Penman ID, Ghosh S. Endoscopic and histologic features of sodium phosphate bowel preparation-induced colonic ulceration: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:584-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Atkinson RJ, Save V, Hunter JO. Colonic ulceration after sodium phosphate bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2603-2605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hookey LC, Depew WT, Vanner S. The safety profile of oral sodium phosphate for colonic cleansing before colonoscopy in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:895-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Parra-Blanco A, Ruiz A, Alvarez-Lobos M, Amorós A, Gana JC, Ibáñez P, Ono A, Fujii T. Achieving the best bowel preparation for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17709-17726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |