Published online Aug 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5986

Peer-review started: April 12, 2017

First decision: May 16, 2017

Revised: June 10, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: August 28, 2017

Processing time: 138 Days and 4.3 Hours

To compare the efficacy of fixed-time split dose and split dose of an oral sodium picosulfate for bowel preparation.

This is study was prospective, randomized controlled study performed at a single Institution (2013-058). A total of 204 subjects were assigned to receive one of two sodium picosulfate regimens (i.e., fixed-time split or split) prior to colonoscopy. Main outcome measurements were bowel preparation quality and subject tolerability.

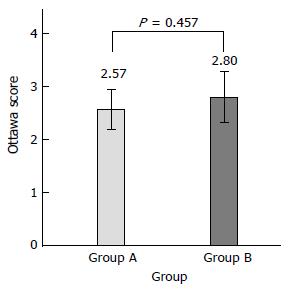

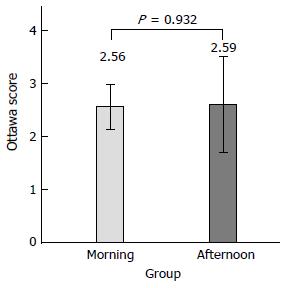

There was no statistical difference between the fixed-time split dose regimen group and the split dose regimen group (Ottawa score mean 2.57 ± 1.91 vs 2.80 ± 2.51, P = 0.457). Cecal intubation time and physician’s satisfaction of inspection were not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.428, P = 0.489). On subgroup analysis, for afternoon procedures, the fixed-time split dose regimen was equally effective as compared with the split dose regimen (Ottawa score mean 2.56 ± 1.78 vs 2.59 ± 2.27, P = 0.932). There was no difference in tolerability or compliance between the two groups. Nausea was 21.2% in the fixed-time split dose group and 14.3% in the split dose group (P = 0.136). Vomiting was 7.1% and 2.9% (P = 0.164), abdominal discomfort 7.1% and 4.8% (P = 0.484), dizziness 1% and 4.8% (P = 0.113), cold sweating 1% and 0% (P = 0.302) and palpitation 0% and 1% (P = 0.330), respectively. Sleep disturbance was two (2%) patients in the fixed-time split dose group and zero (0%) patient in the split dose preparation (P = 0.143) group.

A fixed-time split dose regimen with sodium picosulfate is not inferior to a split dose regimen for bowel preparation and equally effective for afternoon colonoscopy.

Core tip: Fixed-time split dose bowel preparation was not inferior to a split dose regimen in bowel cleansing using the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale. The average score using the Ottawa Scale was 2.57 ± 1.91 in the fixed-time split dose group and 2.80 ± 2.51 in the split dose group (P = 0.457). There was no statistical difference in mean Ottawa score between the two groups when the procedure was performed in the morning or afternoon (2.56 ± 1.78 vs 2.59 ± 2.27, P = 0.932). Therefore fixed-time split dosing with soduim picosulfate is as effective as split dosing for subjects scheduled for colonoscopy in the afternoon.

- Citation: Jun JH, Han KH, Park JK, Seo HI, Kim YD, Lee SJ, Jun BG, Hwang MS, Park YK, Kim MJ, Cheon GJ. Randomized clinical trial comparing fixed-time split dosing and split dosing of oral Picosulfate regimen for bowel preparation. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(32): 5986-5993

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i32/5986.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5986

Currently, colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in the world and its incidence is rapidly increasing in Asian countries[1]. Colonoscopy is an indispensable procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of various colon diseases[2]. Colonoscopy also prevents colorectal cancer by detecting and eliminating precancerous lesions[3-5]. For an accurate colonoscopy, however, it is necessary to perform an appropriate colon preparation[6-8]. Unfortunately, about 20% to 25% of colonoscopies have been reported to occur following inadequate bowel preparation[5-7]. In 27% of patients who had poor bowel preparation, more than 10 mm of polyps were not observed on the first colonoscopy. Therefore the importance of bowel preparation was further emphasized[3].

A variety of bowel preparation agents have been developed to reduce the large amount of fluid consumption and bad taste that can occur during bowel preparation for colonoscopy[9,10]. One a mixture of sodium picosulfate and magnesium citrate, available in Korea (Picolight® powder, Pharmbio Korea Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea), is low-volume bowel cleansing agent with low toxicity in children and adults[11]. This formulation is widely used because of its good compliance with dosage, and excellent bowel cleansing effect[12]. According to the latest guidelines, sodium picosulfate can be taken with only 2 liters of water, which can increase patient compliance[13,14]. The original cleansing protocol entailed two sachets of sodium picosulfate, one at 5 pm and one at 10 pm on the day before colonoscopy. However, a two-day split dose of one sachet at 7 pm on the day prior to colonoscopy and a second sachet four hours before colonoscopy, is also reported as a good regimen for bowel preparation and is nearly equivalent to the use of a polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution[15,16]. In addition, according to a recent report, it is most effective to finish the bowel cleansing three-to-four hours before the scheduled time of the procedure[12].

However as this regimen is based on western diet and lifestyle, it is not necessarily the right method for Koreans, who typically eat more high fiber vegetables than westerners. In the case of Gangneung Asan Hospital located in Gangwon Province, the accessibility of patients is deteriorated by the surrounding mountainous environment. Therefore, it is difficult for some patients to adjust their preparation to colonoscopy time. For the medical staff (doctor, nurse, pharmacist), it is also inconvenient to explain the proper regimen for effective bowel preparation. Additionally, in patients who have to undergo abdominal ultrasound and esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the same time, the results may not be accurate.

We hypothesized that sufficient water intake and effective low residue diet, combined with a fixed-time split dose intake of two, or plus one sachets of sodium picosulfate would result in non- inferior bowel preparation and patient compliance to the split dose regimen. We compared the efficacy of bowel cleansing between the split dose group (last split dose of sodium picosulfate was assigned four hours prior to the colonoscopy) and the fixed-time split dose group (last split dose of picosulfate was assigned at 5:00 am in cases in which the colonoscopy was performed in the morning (09:30 to 11:30 h) and at 6:00 am in cases in which the colonoscopy was performed in the afternoon (13:00 to 15:00 h) using the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale[8]. Colonoscopies are often scheduled in the afternoon, and the split dose may not leave a clean colon by then. Therefore, we further compared the bowel cleansing effect between the morning and afternoon examination groups. We also assessed patient compliance and tolerability to the two bowel preparation regimens.

This study was designed as a prospective single center, single blind, randomized control study of ambulatory outpatients at the Gangneung Asan Hospital, Republic of Korea.

From August 2014 to November 2015, a total of 240 consecutive patients, between the ages of 18 and 76 years who were scheduled to undergo colonoscopy were included. The indications for colonoscopy included colon cancer screening; a family history of colorectal cancer or lower GI symptoms such as constipation or change of bowel habits.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) pregnant women; (2) acute abdomen; (3) history of dehydration and /or drug allergy; (4) congestive heart failure; (5) chronic liver disease or renal insufficiency; (6) history of colon resection or abdominal surgery within six months; and (7) participation in other clinical studies within four weeks prior to randomization. Patients who refused to provide informed consent were also excluded. Following agreement to participate, patients were randomized by computer-generated random numbers to assign them to one of the two preparation regimens. All patients were provided written instructions by the clinical staff. A total of two expert endoscopists who reviewed the Ottawa Bowel preparation Scale and who were blinded to the method of bowel preparation participated in the study. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Gangneung Asan Hospital (IRB: 2013-058), and all participating patients, or their regal guardian provided informed written consents prior to study enrollment.

Patients were randomized to the fixed-time split dose and split dose of the sodium picosulate group. Each group received three sachets of sodium picosulfate (Picolight® powder, Pharmbio Korea Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea), each containing sodium picosulfate hydrate 10 mg, magnesium oxide 3.5 g, and citric acid 12 g. On the third day prior to the colonoscopy, the patients were advised to ingest a low residue diet by doctor and nurse. In the fixed-time split dose group, patients who scheduled to undergo colonoscopy in the morning (9:30-11:30 am) were instructed to dissolve one sachet of sodium picosulfate in 250 mL of water and drink it at 7:00 pm on the day before colonoscopy and at 5:00 am on the day of colonoscopy. Each time, they were to drink 1.25 L of water successively. The patients who scheduled in the afternoon (13:00-15:00), were instructed to take their first dose at 8:00 pm on the day before colonoscopy and their second dose at 6:00 am on the day of colonoscopy in the same method. In the split dose group, the patients were instructed to take the first sachet of sodium picosulfate at 7 pm on the day before colonoscopy and then four hours before the colonoscopy on the day of procedure, in the same method. In both groups, in case of any signs of incomplete bowel preparation (i.e., stool residue or unclear fluid was noted after defecation) observed one hour after the second dose of sodium picosulfate, they also instructed to take an additional one sachet of sodium picosulfate dissolved in 250 mL of water and successive 0.75 L of water.

Colonoscopies were performed with the patients under conscious sedation by a consultant gastroenterologist. All colonoscopies were performed between 9:30 am and 3:00 pm (morning session between 9:30 and 11:30 am, and afternoon session between 1:00 pm and 3:00 pm). Intravenous midazolam 2 mg was used for sedation in patients in whom there was no contraindication; half of that dose was used in patients over the age of 60 years.

Additional sedation was used if required and permissible. Pulse, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation were measured in all patients before, during, and after the procedure.

Before the colonoscopy, a questionnaire survey was conducted on the compliance of the subjects and side effects of the sodium picosulfate. We evaluated the compliance with dosing time and regimen, and the degree of discomfort felt by the patients was recorded separately as sleep disorder, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, dizziness, cold sweating, and/or palpitation. We also evaluated the amount of consumed water. Colonoscopy was performed by two endoscopists who did not know the used regimen. The Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale was used to evaluate the degree of bowel preparation[8]. This scale assesses cleanliness and volume state, separately. Cleanliness was assessed further separately for the right colon (cecum - ascending colon), mid-colon (transverse - descending colon), and rectosigmoid colon on a five-point scale (no liquid = 0, minimal liquid, no suctioning required = 1, suction required to see mucosa = 2, wash and suction = 3, solid stool, not washable = 4). The degree of residual fluid in the entire colon was classified from 0 to 2. A score of 0 indicates excellent bowel preparation, and a score of 14 indicates that colonoscopy is impossible[8,17]. The cecal intubation time was also measured and compared. Starting and cecal intubation time was recorded. After the colonoscopy, the bowel preparation quality and satisfaction of the procedure (via a 10-point physician’s satisfaction of inspection) was rated by two investigators who were blinded to the type of preparation. The results were recorded on a standardized form.

In this study, the level of significance was assumed to be 5% with regards to the number of effective subjects. The second type error was 0.2, the power was maintained at 80%, and the effect size was 10%. The total number of subjects necessitated at least 91 subjects in each group. A total of 240 subjects (120 subjects per group) were required for a follow-up loss of about 30%.

This study was designed as a one-sided χ2 test for non-inferiority. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS ver. 23.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). The variables expressed as percentages (characteristics of the study subject, adverse effects) were used in χ2 test (Fisher’s exact test). The means of the two groups (Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale value, satisfaction, insertion time, and degree of disgust) was used in Student’s t-test.

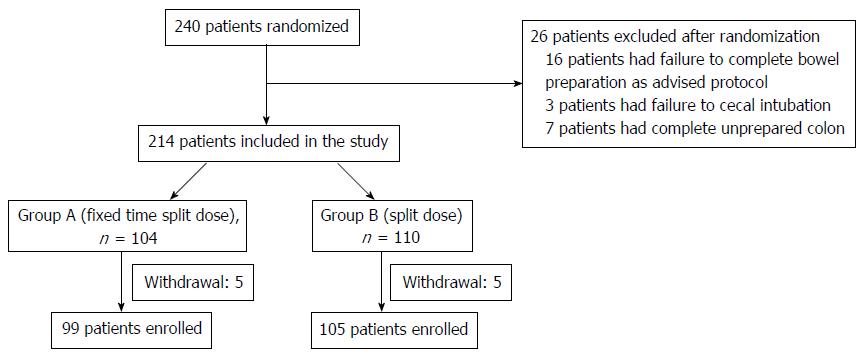

In this prospective, randomized, investigator-blinded study, we enrolled 240 patients between August 2014 and November 2015. Of the 240 patients randomized, 36 were excluded due to the following: failure to complete bowel preparation as advised (n = 16); failure to cecal intubation due to abdominal pain or vomiting, colon cancer (n = 3); withdrawal of consent (n = 10, fixed-time split dose group; 5, split dose group; 5); and a completely unprepared colon (n = 7, fixed-time split dose group; 4, split dose group; 3). Ultimately, 99 patients in the fixed-time split dose group and 105 in the split dose group completed the study and were analyzed (Figure 1). The characteristics of the patients in the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical difference between the two groups with respect to gender, height, weight, mean age, BMI, and/or history of abdominal surgery and DM (Table 1).

| Group A ( fixed time split dose preparation) n = 99 | Group B (split dose preparation) n = 105 | P value | |

| Male: Female | 61:38 | 57:48 | NS |

| Mean age, r | 54.6 ± 11.5 | 54.3 ± 9.4 | NS |

| Age ≥ 65 | 20 (20.2) | 16 (15.2) | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 64.7 ± 11.7 | 65.4 ± 11.3 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 3.05 | 24.2 ± 2.88 | NS |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 4 (4) | 4 (3.8) | NS |

| History of abdominal surgery | 7 (7.1) | 7 (6.7) | NS |

| History of Diabetus mellitus | 8 (8.1) | 12 (11.4) | NS |

Using the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale, the mean Ottawa score was 2.57 ± 1.91 in the fixed-time split dose preparation and 2.80 ± 2.51 in the split dose preparation (P = 0.457)(Figure 2).

Cecal intubation time and physician’s satisfaction of the inspection were not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.428, P = 0.489)(Table 2).

| Group A (fixed time split dose preparation) n = 99 | Group B (split dose preparation) n = 105 | P value | |

| Mean total Ottawa preparation score1 | 2.57 ± 1.91 | 2.80 ± 2.51 | 0.457 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 3.40 ± 2.03 | 3.38 ± 2.98 | 0.976 |

| Right colon, mean (0-4) | 0.92 ± 0.71 | 0.96 ± 0.82 | 0.692 |

| Mid colon, mean (0-4) | 0.76 ± 0.74 | 0.76 ± 0.83 | 0.969 |

| Rectosigmoid colon, mean (0-4) | 0.73 ± 0.68 | 0.74 ± 0.85 | 0.886 |

| Residual fluid, mean (0-2) | 0.17 ± 0.43 | 0.33 ± 0.56 | 0.023 |

| Adverse GI symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Nausea | 21 (21.2) | 14 (13.3) | 0.136 |

| Vomiting | 7 (7.1) | 3 (2.9) | 0.164 |

| Sleep disturbance | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.143 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 7 (7.1) | 5 (4.8) | 0.484 |

| Dizziness | 1 (1) | 5 (4.8) | 0.113 |

| Cold sweating | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.302 |

| Palpitation | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.330 |

| Mean cecal intubation time, min ± SD | 5.02 ± 3.42 | 4.70 ± 2.27 | 0.428 |

| Physician's satisfaction of inspection | 8.17 ± 1.21 | 8.04 ± 1.51 | 0.489 |

On subgroup analysis of fixed-time split dose preparation, there was no difference of mean Ottawa score between the morning colonoscopy (9:30 to 11:30 am) and the afternoon (1:00-3:00 pm) colonoscopy groups (2.56 ± 1.78 vs 2.59 ± 2.27, P = 0.932) (Figure 3).

Nausea was complained of in 21.2% of the patients with the fixed-time split dose preparation and in 14.3% with split dose preparation (P = 0.136). Vomiting was reported by 7.1% and 2.9% (P = 0.164), abdominal discomfort by 7.1% and 4.8% (P = 0.484), dizziness by 1% and 4.8% (P = 0.113), cold sweating by 1% and 0% (P = 0.302) and palpitation by 0% and 1% (P = 0.330), respectively. Sleep was disturbed in two (2%) patients in the fixed-time split dose preparation and zero (0%) patients in the split dose preparation (P = 0.143) groups (Table 2).

Colonoscopy is the most effective tool for diagnosing colon diseases, including inflammation bowel disease and colorectal cancers. Good quality of bowel preparation can lead to good colonoscopy results, while incomplete bowel preparations decreases cecal intubation and adenoma detection rates[18]. It also increases patient’s discomfort and procedure costs[5]. Sodium picosulfate is safe and effective for bowel preparation with good tolerability and fewer side effects than the standard 4L PEG solution[15,19-21]. It is known from a meta-analysis of 29 studies that the use of a split dose on the day before and on the day of the procedure can induce more effective bowel preparations than a dosing regimen on the day before the procedure[7]. Recently, the use of a split dose regimen of sodium picosulfate was reported more superior than a previous-day regimen and the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale score was the lowest at three-to-four hours after the last cleansing[12].

Although sodium picosulfate is a low-volume agent for bowel preparation that has been available in Korea since December 2011, we often experienced indications that this agent showed limited bowel preparation capacity. It is often inconvenient for medical staff members to explain the effective bowel preparation time to the patients because each patient has a different examination time. In addition, in patients with poor compliance, such as elderly patients or those who live far away from the hospital due to their local characteristics, it is often difficult to maintain the effective bowel cleansing time and thus the bowel cleansing often becomes inadequate. Therefore, we hypothesized that if the patient has adequate dietary control and water intake before colonoscopy, it is possible to obtain effective bowel preparations by instructing them regarding a fixed dosing time varied according to a morning or afternoon test time.

First, we compared the Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale score in the fixed-time split dose group and the split dose group to confirm the appropriate bowel preparations. There was no significant difference between the two groups (Table 2 and Figure 2). Additionally Ottawa scores according to each segment were no significantly different between the experimental group and the control group (Table 2).

Sixty-seven patients (68% of fixed-time split dose group) and 70 patients (67% of split dose group) completed bowel preparation with two sachets of sodium picosulfate (Table 3). We think these results are due to the Korean life style and high fiber diet, which include foods such as “Kimchi” and seaweed, and two sachets of sodium picosulfate are insufficient for bowel preparation. Therefore we recommend three sachets of sodium picosulfate and adequate modification of water intake.

| Group A (fixed time split dose preparation) n = 99 | Group B (split dose preparation) n = 105 | P value | |

| Sodium picosulfate | |||

| 2 sachets | 2.43 ± 1.90 (n = 67) | 3.00 ± 2.68 (n = 70) | 0.158 |

| 3 sachets | 2.84 ± 1.95 (n = 32) | 2.40 ± 2.10 (n = 35) | 0.375 |

| 2 or 3 sachets | 2.57 ± 1.91 (n = 99) | 2.80 ± 2.51 (n = 105) | 0.457 |

The prospected randomized clinical trials to compare the preference and efficacy of sodium picosulfate in Korea proved that three sachets of sodium picosulfate regimen were as effective as conventional high volume PEG solution. And sodium picosulfate groups reported superior palatability and tolerability[22-24].

But patients with renal insufficiency, uncontrolled cardiovascular problems, liver disease, metabolic disease and admitted patients were excluded from this study. Therefore, these results are inapplicable to high-risk or admitted patients and additional studies are warranted.

Second, we compared the bowel cleansing effects of the sodium picosulfate between the morning colonoscopy and afternoon colonoscopy groups. There was no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 3). According to this results, fixed-time dosing regimen may be convenient for patients for bowel preparation who are undergoing other procedures, such as abdominal ultrasound and esophagogastroduodenoscopy on the same day. However, this result is in conflict with a previous study that shows the lowest Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale score when endoscopy was performed three-to-four hours after the completion of bowel preparation[12,17,25-27]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy also recommends that the last preparation to colonoscopy interval should be minimized and should be no longer than four hours. In cases of the afternoon colonoscopy group, the gap between last dosing and colonoscopy time was six to nine hours.

We believe that there are several reasons for these result. In this study, we suggests that if the patients has an accurate understanding of bowel cleansing time and method, that this may be more important than other additional factors. Considering the Korean life style and diet pattern, we emphasized that patients should take relatively more water (3 L to 4 L) than typical, and should consume low residue diet starting three days before colonoscopy. The second consideration is that the previous study was mainly focused PEG solution rather than sodium picosulfate, so the bowel cleansing result of sodium picosulfate observed in this study may be different from that in the previous study[17]. In addition, previous studies conducted with sodium picosulfate were mainly performed involving westerners, and these individuals may consume diets different from that of an Asian’s diet, therefore further studies on Asians are needed[12,28].

Our study has several limitations. First, because all enrolled patients were Koreans who eat a more high-fiber diet than most westerners do, our protocol consisted of recommending a relatively large amount of fluid (3 L to 4 L) intake and suggesting low residue diet three days before colonoscopy. Therefore this study’s results may differ from western data due to the inclusion of different dietary patterns and other ethnic groups.

Second, although there was no difference in bowel preparation between the morning colonoscopy and the afternoon colonoscopy groups (Figure 3), the number of patients enrolled in the afternoon group was smaller (74 vs 25). To obtain more accurate results, analysis of a larger number of patients is needed.

Lastly, the lower success rate for bowel preparation with two sachets of sodium picosulfate and 3L of water intake (68% of the fixed-time split dose group), led us to recommend three sachets of sodium picosulfate and adequate water intake (Table 3). Because dietary factors and amount of water intake can greatly affect the success of bowel preparation, to find the optimal conditions for effective bowel preparation, further studies on these factors are needed.

In conclusion, the fixed-time split dose bowel preparation is equally effective as compared with the conventional split dose bowel preparation. This method is also convenient for medical staffs (i.e., doctors, nurses and pharmacists) as a means to simplify explaining the bowel cleansing protocol to patients, and may possibly increase the compliance of patients in bowel preparation.

The authors thank Pharmbio Korea Co., Ltd. for providing Picolight®.

Sodium picosulfate is a widely used bowel cleansing agent, but there is no standard recommendation for the adequate bowel cleansing time. Studies have shown that the split preparation is better than the conventional previous evening preparation for bowel preparation quality and patient’s compliance. The split dose option is also endorsed by the American College of Gastroenterology and is considered an optimal choice for colonoscopy. Previous studies have proven that the bowel cleansing effect is the best when taking the sodium picosulfate three to four hours before colonoscopy. However, this regimen is based on data from western countries, which have different dietary patterns from that of many Asians including Koreans. Additionally, this protocol is not easy to ensure in patients who have low accessibility to hospitals. Patients who are scheduled to undergoing ultrasound and esophagogastroduodenoscopy on the morning of the same day morning also may have inaccurate results. Considering the Korean high fiber dietary pattern, the authors compared the quality of bowel preparation between a fixed -time split dose group and split group after training them to intake a sufficient amount of water and consume a low residue diet beginning three days before colonoscopy. The primary endpoint was the quality of bowel preparation.

The quality of bowel preparation and optimal time of colonoscopy is important for successful colonoscopy. Compliance of patients is also considered modifiable factor for good results. Various studies are being conducted to determine the optimal time of colonoscopy after last dose of bowel preparation.

This is the first randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of fixed-time split dosing of oral picosulfate for bowel preparation. In this study there was no statistical difference in the quality of bowel preparation between the fixed-time split dose bowel preparation and the split dose bowel preparation. Therefore, fixed-time split dose bowel preparation can be an alternative regimen for successful colonoscopy.

This study would be used to improve compliance for colonoscopy and convenience for the medical staff in instructing patients on the regimen of bowel cleansing agents.

Fixed-time bowel preparation: the patients take the last split dose of laxative at a set time according to the morning and afternoon colonoscopy.

This article presents an important issue. This is the first study to compare the bowel cleansing effect when the last split dosing time was fixed. Methods and study population are adequate, and conclusions are reasonable and of possible practical use. Overall this study is timely and interesting to the readership.

| 1. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in RCA: 11886] [Article Influence: 792.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8988] [Article Influence: 642.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Richard Boland C, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1528-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rex DK. Optimal bowel preparation--a practical guide for clinicians. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [PubMed] |

| 6. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, Early DS, Muthusamy VR, Khashab MA, Chathadi KV, Fanelli RD, Chandrasekhara V, Lightdale JR, Fonkalsrud L, Shergill AK, Hwang JH, Decker GA, Jue TL, Sharaf R, Fisher DA, Evans JA, Foley K, Shaukat A, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Wang A, Acosta RD. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:781-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Bucci C, Rotondano G, Hassan C, Rea M, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L, Ciacci C, Marmo R. Optimal bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: split the dose! A series of meta-analyses of controlled studies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:566-576.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:482-486. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | ASGE Technology Committee, Mamula P, Adler DG, Conway JD, Diehl DL, Farraye FA, Kantsevoy SV, Kaul V, Kethu SR, Kwon RS, Rodriguez SA, Tierney WM. Colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1201-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Turner D, Benchimol EI, Dunn H, Griffiths AM, Frost K, Scaini V, Avolio J, Ling SC. Pico-Salax versus polyethylene glycol for bowel cleanout before colonoscopy in children: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Prieto-Frías C, Muñoz-Navas M, Betés MT, Angós R, De la Riva S, Carretero C, Herraiz MT, Alzina A, López L. Split-dose sodium picosulfate-magnesium citrate colonoscopy preparation achieves lower residual gastric volume with higher cleansing effectiveness than a previous-day regimen. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:566-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rex DK, Katz PO, Bertiger G, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Alderfer V, Joseph RE. Split-dose administration of a dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser for colonoscopy: the SEE CLEAR I study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:132-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Katz PO, Rex DK, Epstein M, Grandhi NK, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Alderfer V, Joseph RE. A dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser administered the day before colonoscopy: results from the SEE CLEAR II study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Regev A, Fraser G, Delpre G, Leiser A, Neeman A, Maoz E, Anikin V, Niv Y. Comparison of two bowel preparations for colonoscopy: sodium picosulphate with magnesium citrate versus sulphate-free polyethylene glycol lavage solution. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1478-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Flemming JA, Vanner SJ, Hookey LC. Split-dose picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid solution markedly enhances colon cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:537-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Seo EH, Kim TO, Park MJ, Joo HR, Heo NY, Park J, Park SH, Yang SY, Moon YS. Optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval in split-dose PEG bowel preparation determines satisfactory bowel preparation quality: an observational prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bernstein C, Thorn M, Monsees K, Spell R, O’Connor JB. A prospective study of factors that determine cecal intubation time at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:72-75. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Schmidt LM, Williams P, King D, Perera D. Picoprep-3 is a superior colonoscopy preparation to Fleet: a randomized, controlled trial comparing the two bowel preparations. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:238-242. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Love J, Bernard EJ, Cockeram A, Cohen L, Fishman M, Gray J, Morgan D. A multicentre, observational study of sodium picosulfate and magnesium citrate as a precolonoscopy bowel preparation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:706-710. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hookey LC, Vanner SJ. Pico-salax plus two-day bisacodyl is superior to pico-salax alone or oral sodium phosphate for colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:703-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Song KH, Suh WS, Jeong JS, Kim DS, Kim SW, Kwak DM, Hwang JS, Kim HJ, Park MW, Shim MC. Effectiveness of Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Citrate (PICO) for Colonoscopy Preparation. Ann Coloproctol. 2014;30:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim ES, Lee WJ, Jeen YT, Choi HS, Keum B, Seo YS, Chun HJ, Lee HS, Um SH, Kim CD. A randomized, endoscopist-blinded, prospective trial to compare the preference and efficacy of four bowel-cleansing regimens for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:871-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 24. | Jeon SR, Kim HG, Lee JS, Kim JO, Lee TH, Cho JH, Kim YH, Cho JY, Lee JS. Randomized controlled trial of low-volume bowel preparation agents for colonic bowel preparation: 2-L polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid versus sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:251-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas-Perez D, Gimeno-Garcia A, Grosso B, Jimenez A, Ortega J, Quintero E. The timing of bowel preparation before colonoscopy determines the quality of cleansing, and is a significant factor contributing to the detection of flat lesions: a randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6161-6166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Eun CS, Han DS, Hyun YS, Bae JH, Park HS, Kim TY, Jeon YC, Sohn JH. The timing of bowel preparation is more important than the timing of colonoscopy in determining the quality of bowel cleansing. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:539-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, Cryer B, Davila R, Cipher D, Harford WV. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:700-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Manes G, Repici A, Hassan C; MAGIC-P study group. Randomized controlled trial comparing efficacy and acceptability of split- and standard-dose sodium picosulfate plus magnesium citrate for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014;46:662-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): E

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Castro FJ, Facciorusso A, Lorenzo-Zuniga V, Matsuda A, Senates E S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF