Published online Jan 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.328

Peer-review started: August 9, 2016

First decision: September 20, 2016

Revised: October 19, 2016

Accepted: November 13, 2016

Article in press: November 13, 2016

Published online: January 14, 2017

Processing time: 156 Days and 21.1 Hours

To compare the efficacy and safety of cold snare polypectomy (CSP) and hot forceps biopsy (HFB) for diminutive colorectal polyps.

This prospective, randomized single-center clinical trial included consecutive patients ≥ 20 years of age with diminutive colorectal polyps 3-5 mm from December 2014 to October 2015. The primary outcome measures were en-bloc resection (endoscopic evaluation) and complete resection rates (pathological evaluation). The secondary outcome measures were the immediate bleeding or immediate perforation rate after polypectomy, delayed bleeding or delayed perforation rate after polypectomy, use of clipping for bleeding or perforation, and polyp retrieval rate. Prophylactic clipping after polyp removal wasn’t routinely performed.

Two hundred eight patients were randomized into the CSP (102), HFB (106) and 283 polyps were evaluated (CSP: 148, HFB: 135). The en-bloc resection rate was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB [99.3% (147/148) vs 80.0% (108/135), P < 0.0001]. The complete resection rate was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB [80.4% (119/148) vs 47.4% (64/135), P < 0.0001]. The immediate bleeding rate was similar between the groups [8.6% (13/148) vs 8.1% (11/135), P = 1.000], and endoscopic hemostasis with hemoclips was successful in all cases. No cases of perforation or delayed bleeding occurred. The rate of severe tissue injury to the pathological specimen was higher HFB than CSP [52.6% (71/135) vs 1.3% (2/148), P < 0.0001]. Polyp retrieval failure was encountered CSP (7), HFB (2).

CSP is more effective than HFB for resecting diminutive polyps. Further long-term follow-up study is required.

Core tip: Cold snare polypectomy (CSP) is more effective in terms of both endoscopic en-bloc resection rate and pathological complete resection rate than hot forceps biopsy (HFB) for resecting diminutive polyps. Moreover, CSP and HFB did not result in any serious adverse events such as delayed bleeding and perforation.

- Citation: Komeda Y, Kashida H, Sakurai T, Tribonias G, Okamoto K, Kono M, Yamada M, Adachi T, Mine H, Nagai T, Asakuma Y, Hagiwara S, Matsui S, Watanabe T, Kitano M, Chikugo T, Chiba Y, Kudo M. Removal of diminutive colorectal polyps: A prospective randomized clinical trial between cold snare polypectomy and hot forceps biopsy. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(2): 328-335

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i2/328.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.328

The United States National Polyp Study demonstrated that a clean colon (i.e., a colon in which all adenomatous polyps have been eliminated) significantly decreases the mortality rate for colorectal cancer[1]. Accordingly, there is a need to consider the resection of neoplastic polyps, including diminutive polyps, when performing colonoscopy. Cold snare polypectomy (CSP) is becoming a common method for resecting small or diminutive polyps without using submucosal injections or electrocautery, and it is regarded as a safe treatment in Western countries[2]. Recently, it has also gradually gained popularity in Japan[3-5]. The advantages of CSP are that electrocautery-related damages to the submucosal vascular tissue are prevented and there are fewer restrictions on patients’ postoperative activity or diet. Low rates of postoperative bleeding and perforation can also be expected, because electrocautery is not used during CSP.

Hot forceps biopsy (HFB) is another method used to remove diminutive polyps; it has been widely used in Japan, because it is comparatively easy to use. Although the HFB approach is advantageous in that possible adenomatous remnants are fulgurated and the blood vessels are coagulated, it also has disadvantages associated with electrocautery, such as perforation and delayed bleeding[6,7]. To our knowledge, CSP and HFB have not been directly compared. We hypothesized that CSP would be more effective than HFB for resecting diminutive polyps 3-5 mm. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of CSP and HFB for removing colorectal polyps measuring 3-5 mm.

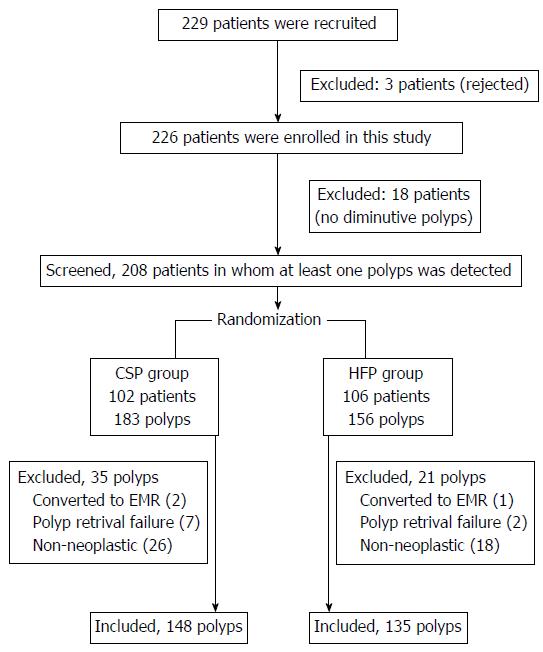

This prospective, randomized, single-center comparison study was conducted from December 2014 to October 2015. The inclusion criteria were consecutive patients over 20 years old and those who were scheduled to undergo the removal of colorectal polyps measuring 3-5 mm. The preoperative exclusion criteria were patients with inflammatory bowel disease, polyposis, polyps suggestive of cancer, and hyperplastic polyps measuring less than 5 mm in the distal colon. Similar to hyperplastic polyps less than 5 mm, typical hyperplastic polyps featuring white, flat protrusions with a diameter of 5 mm or less, which are frequently observed in the distal colon (rectum and sigmoid colon), reportedly exhibit no relationship with adenoma onset in the future, and guidelines state that no proactive action is required. The intra-operative exclusion criteria were patients converted to endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), those with polyp retrieval failure, and patients with non-neoplastic polyps. Patients presenting with diminutive polyps were assigned to either the CSP or HFB group using computer-generated random sequencing. The polyp size was estimated on the basis of the maximum width of the opened snare or HFB. Endoscopic and pathological images obtained during the tests were de-identified, and they were used to make diagnoses on the basis of the findings. No limit was set for the number of polyps removed per patient. Each polypectomy was considered independent of the others.

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (registration number 26-180; date: Dec 2 2014), and it was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN ID: 000015016; date of registration: Sep 1, 2014). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The primary outcome measures were as follows: the en-bloc resection rate (endoscopic evaluation was used to confirm the tumor-free cut margin with magnified endoscopic view) and complete resection rate (pathological evaluation was used to confirm the tumor-free cut margin in microscopic view). The secondary outcome measures were as follows: the immediate bleeding or immediate perforation rate after polypectomy, delayed bleeding or delayed perforation rate after polypectomy, use of clipping for bleeding or perforation, and polyp retrieval rate.

Immediate bleeding was defined as spurting or oozing blood that continued for more than 1 min following resection that was stopped with hemoclips. Delayed bleeding was clinically defined as evident hematochezia after the patient was removed from the endoscopic room; this was confirmed by a questionnaire at the time of the patient’s next hospital visit (7-10 d after treatment). Prophylactic clipping after polyp removal was not routinely performed, except in patients with immediate bleeding or in those with a high risk for perforation, patients with a bleeding tendency, those taking antithrombotic agents, etc.

All colonoscopic procedures were performed by six experienced endoscopists (H.K., T.S., Y.A., Y.K., T.N., and H.M.) who had each performed more than 1000 polypectomies before. No colonoscopist had performed CSP before this trial. High-definition endoscopes (PCF-Q260AZI, CF-H260AZI, CF-HQ290I; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) were used in this study. Patients drank a polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution (Ajinomoto Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) for bowel preparation. Two types of snares were used for CSP: the Profile snare and Captivator-II Snare (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States), both of which are approved for cold polypectomy in Japan. Each endoscopist chose which snare they preferred. In addition, the FD-1U-1 forceps (Olympus) was used to perform HFB. The respective maximum widths of the FD-1U-1 forceps, Profile snare, and Captivator-II Snare were 7, 10, and 11 mm.

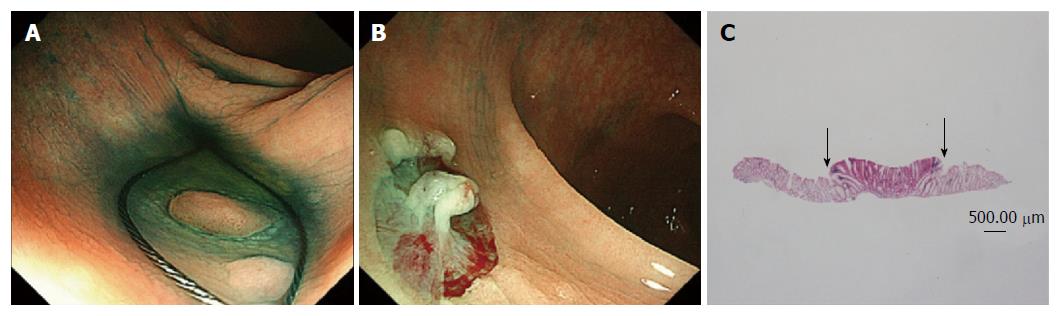

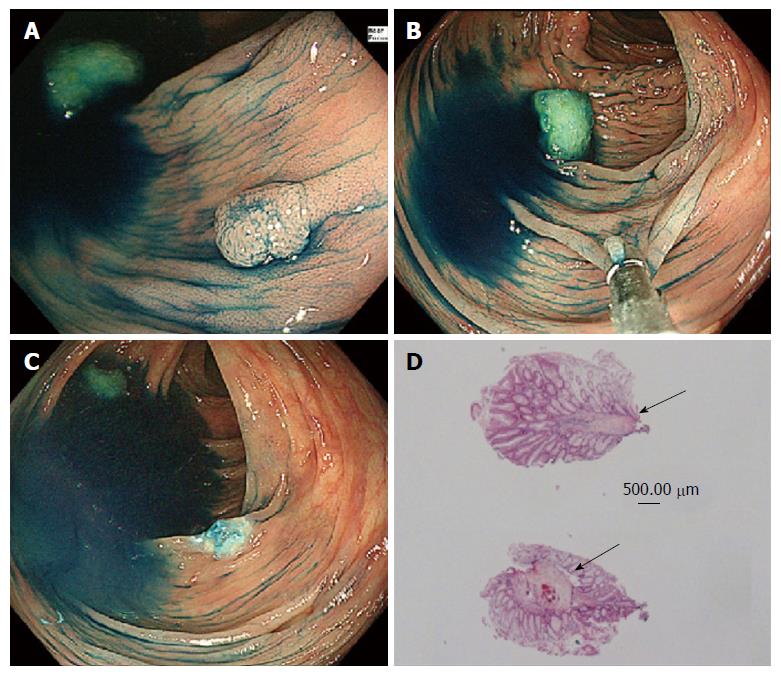

During CSP, the polyps were resected without injection or electrocautery, and some of the surrounding normal mucosa was removed (Figure 1). The transected polyps in the CSP group were vacuumed into a trap and were collected (Figure 2). During HFB, an electrocautery with coagulating current at 25-30 W in the setting of the electrosurgical unit VIO300D (Erbe Elektromedizin, Tuebingen, Germany) was applied to the polyp until the white coagulum was seen at the polyp base (Figure 3)[8], and then the polyp was removed by gently pulling it from the mucosa. The resected polyps in the HFB group were collected in the cup of the forceps.

All tissue specimens were examined by an experienced pathologist (T.T.) who was blinded to the clinical information concerning the patient and polyp, and to how the polyp was resected. The vertical and lateral cut margins and tissue damage were evaluated with a hematoxylin and eosin stain.

The sample size was calculated on the basis of the overall estimated complete resection rate. We assumed that it would be 95% in the CSP group and 80% in the HFB group according to the results of previous reports (93% and 83%, respectively)[9,10]. Thus, the needed sample size was 150 polyps per group with a significance level of 5% (two-tailed) and power of 80% when the Fisher exact test was used to confirm superiority of CSP to HFB. We assumed a dropout rate of 10%; thus, we determined that the sample size should be 165 polyps per group.

Categorical variables were compared with the Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared with the t-test. To determine predictive factors of complete resection, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analysis with the resection method (CSP or HFB) and polyp characteristics (location, shape, and histology) as explanatory variables.

We performed a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. In our modified ITT analysis, we considered polyps converted to EMR and polyp retrieval failure as incomplete en-bloc resection and pathological resection. We excluded the non-neoplastic polyps from ITT analysis because endoscopic/pathological evaluation of these polyps could not originally be performed. The target of modified ITT analysis was 157 polyps in CSP and 138 polyps in HFB.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

Two hundred eight patients were enrolled in the study [mean ± SD: age 69.0 ± 8.0 years (range 35-87 years), 31% women], and we excluded 3 patients who were rejected (the rejection rate for inclusion in the trial was 1.3%: 3/229) and 18 patients who had no diminutive polyps (7.9%: 18/229). After randomization was performed, 102 patients were allocated to the CSP group, and 106 were allocated to the HFB group. A flowchart of the study enrollment is shown in Figure 1. The mean ages were 69.4 ± 9.4 in the CSP group and 68.9 ± 7.9 in the HFB group. The mean number of resected polyps per patient was 1.5 in the CSP group and 1.3 in the HFB group. Finally, 283 polyps (CSP group: 148 polyps, HFB group: 135 polyps) were evaluated after excluding some polyps (polyps removed with EMR, polyps that could not be retrieved, and non-neoplastic polyps). There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to the characteristics of the patients and polyps (Tables 1 and 2). According to the pathological diagnosis, tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia accounted for 83.4% of polyps in the CSP group and 93.3% in the HFB group.

| CSP group (n = 102) | HFB group (n = 106) | P value | |

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 69.4 (8.0) | 68.9 (7.9) | 0.60 |

| Female sex | 32 (31.3) | 31 (29.2) | 0.76 |

| Use of antithrombotic agents | 4 (3.9) | 3 (2.8) | 0.72 |

The en-bloc resection rate was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB [99.3% (147/148) vs 80.0% (108/135), P < 0.0001]. The complete resection rate was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB [80.4% (119/148) vs 47.4% (64/135), P < 0.0001]; however, there were 6 polyps in the CSP group that broke into pieces during retrieval by aspiration (Table 3). The immediate bleeding rate was similar between the two groups [CSP group: 8.8% (13/148) vs HFB group: 8.1% (11/135), P = 1.000]. Endoscopic hemostasis with hemoclips was successful in cases of immediate bleeding. Serious adverse events such as perforation or delayed bleeding did not occur in any case, although prophylactic clipping after polyp removal was not routinely performed, except in cases of immediate bleeding or in those with a high risk of bleeding.

| CSP group (95%CI) | HFB group (95%CI) | P value | |

| Endoscopic evaluation | 147/148 = 99.3% | 108/135 = 80.0% | < 0.0001 |

| En-bloc resection rate with free cut-margin | (92.3%-100.0%) | (72.3%-86.4%) | |

| Pathologic evaluation | 119/148 = 80.4% | 64/135 = 47.4% | < 0.0001 |

| Complete resection rate with free cut-margin | (73.1%-86.5%) | (38.8%-56.2%) | |

| Histological tissue injury | 2/148 = 1.3% | 71/135 = 52.6% | < 0.0001 |

| (0.2%-4.8%) | (43.8%-61.2%) | ||

| Adverse event | |||

| Immediate bleeding | 13/148 = 8.8% | 11/135 = 8.1% | 1.00 |

| (4.8%-14.6%) | (4.1%-14.1%) | ||

| Delayed bleeding | 0 | 0 | |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 | |

The rate of tissue injury according to the pathologic specimen was higher in the HFB group than in the CSP group [52.6% (71/135) vs 1.3% (2/148), P < 0.0001]. The frequency of polyp retrieval failure was higher in the CSP group than in the HFB group (7/148 vs 2/135). There was no significant difference between the Profile snare and Captivator II Snare for CSP in terms of all the factors (Table 4).

| Profile snare (95%CI) | Captivator-II snare (95%CI) | P value | |

| Endoscopic evaluation | 88/88 = 100% | 59/60 = 98.3% | 0.41 |

| En-bloc resection rate with free cut-margin | (95.9%-100.0%) | (91.2%-100.0%) | |

| Pathologic evaluation | 75/88 = 85.2% | 44/60 = 73.3% | 0.09 |

| Complete resection rate with free cut-margin | (76.1%-91.9%) | (60.3%-83.9%) | |

| Histological tissue injury | 0/88 = 0% | 2/60 = 3.3% | 0.16 |

| (0.0%-4.1%) | (0.4%-11.5%) | ||

| Adverse event | |||

| Immediate bleeding | 9/88 = 10.2% | 4/60 = 6.7% | 0.56 |

| (4.8%-18.5%) | (1.8%-16.2%) | ||

| Delayed bleeding | 0 | 0 | |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 |

The results of this modified ITT analysis were that the en-bloc resection rate was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB [87.9% (138/157) vs 76.0% (105/138), P < 0.0001]. The complete resection rate was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB [70.1% (110/157) vs 44.2% (61/138), P < 0.0001]. There was no significant difference between the original data and modified ITT analysis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the resection method (CSP vs HFB) was the strongest predictive factor for complete resection (Table 5).

We demonstrated that CSP is more effective than HFB for resecting diminutive polyps 3-5 mm. Recently, in a randomized controlled trial at a single center, Lee et al[9] reported that CSP was superior to CFP for removing small polyps ≤ 5 mm (93% vs 76%, P = 0.009). Kim et al[11] also demonstrated that the overall complete resection rate was significantly higher in the CSP group than in the CFP (96.6% vs 82.6%, P = 0.01) for polyps ≤ 7 mm. Authors of a pilot study conducted in Japan reported that the rate of complete resection after CSP for polyps < 10 mm was 60%[3]. The present study’s findings showed that the overall complete resection rate for polyps 3-5 mm was significantly higher with CSP than with HFB, although six polyps in the CSP group could not be evaluated because they broke into pieces in the working channel of the scope during aspiration. In 19.6% of patients in the CSP group, the resected free cut-margin was very close to the lesion, thus it was considered unclear (i.e., tumor involvement of the horizontal margin could not be determined).

In the present study, the HFB group had a low complete resection rate of 47.4%, significantly low rate 80.0% with en-bloc resection, and substantial tissue damage due to electric resection. It is concerning that HFB caused so much thermal damage to the specimen that it made the pathological diagnosis difficult.

The current study also demonstrated similar immediate bleeding rates in both groups, and endoscopic hemostasis with hemoclips was successful in these cases. Horiuchi et al[12] reported that CSP was used safely even in patients taking antiplatelet agents and in those in which therapeutic levels of anticoagulation were achieved, although the sample size was small.

In our study, no perforation or delayed bleeding occurred in any case. The first author previously reported on an animal experiment conducted in pigs at another institution, and no perforation occurred with CSP for large polyps exceeding 1 cm[13]. In the present study, two polyps could not be resected with CSP because there was too much resistance during snaring; therefore, they were converted with conventional EMR using an injection and electrical current was used. These cases were excluded from further evaluation. Accordingly, a very low incidence of perforation can be expected in CSP. The change in the resection method may have contributed to the low rate perforation.

A previous study reported a perforation rate of 0.05% after HFB, including one case of death[14]. In the present study, no serious adverse events (delayed bleeding, perforation, or post-coagulation syndrome) were observed in HFB group. Although Williams reported a rate of 95% for specimens with interpretable histological features[8], our study demonstrated that the rate of severe histological tissue injury was higher in the HFB group than in the CSP group.

Polyp retrieval failure occurred in seven patients in the CSP group and two patients in the HFB group. This corresponds with a previously reported result that specimen retrieval is more difficult when the polyp size is ≤ 5 mm[15].

There were some limitations to this study. It was performed at a single university hospital. We only used the two types of snares that are approved for cold resection in Japan; thus, our results may not be applicable to other snares. In this study, we did not assess the amount of time required using each of the two techniques for complete polyp resection in each colonoscopy because the time for polypectomy did not differ between cold forceps polypectomy as almost same technique of HFB and CSP in a previous study[16]. We did not compare the two procedures. Lastly, the study did not include long-term follow-up after resection.

In conclusion, our results showed that CSP is more effective than HFB for resecting diminutive polyps. The endoscopic en-bloc resection rate and pathologic complete resection rate were lower with HFB, as histological evaluation in the HFB group was difficult due to tissue injury. Serious adverse events such as delayed bleeding and perforation did not occur in either group. Further study with long-term follow-up is required.

The advantages of cold snare polypectomy (CSP) are that electrocautery-related damage to the submucosal vascular tissue is prevented, and there are fewer restrictions on patients’ postoperative activity and diet. Low rates of postoperative bleeding and perforation can also be expected, because electrocautery is not used during CSP. Hot forceps biopsy (HFB) is another method used to remove diminutive polyps because it is comparatively easy to use. CSP and HFB have not previously been directly compared.

A few human studies in the West have suggested that CSP is a safe treatment without electrocautery-related damages and HFB has disadvantages associated with electrocautery, such as perforation and delayed bleeding.

This is the first randomized controlled prospective study to compare the efficacy of CSP and HFB. CSP is more effective in terms of both endoscopic en-bloc resection rate and pathological complete resection rate than HFB for resecting diminutive polyps, as histological evaluation with HFB was difficult due to tissue injury.

CSP is preferable under the removal of colorectal diminutive polyps without polyps suggestive of cancer, and hyperplastic polyps measuring less than 5 mm in the distal colon.

CSP is a method for resecting diminutive polyps without using submucosal injections or electrocautery. HFB captures the polyp in the cup of the forceps and gently pulls it from the mucosa with electrocautery.

This study showed a topic of interest in clinical practice.

| 1. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3107] [Cited by in RCA: 3181] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Repici A, Hassan C, Vitetta E, Ferrara E, Manes G, Gullotti G, Princiotta A, Dulbecco P, Gaffuri N, Bettoni E. Safety of cold polypectomy for & lt; 10mm polyps at colonoscopy: a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Takeuchi Y, Yamashina T, Matsuura N, Ito T, Fujii M, Nagai K, Matsui F, Akasaka T, Hanaoka N, Higashino K. Feasibility of cold snare polypectomy in Japan: A pilot study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:1250-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Hewett DG, Rex DK. Colonoscopy and diminutive polyps: hot or cold biopsy or snare? Do I send to pathology? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Uraoka T, Ramberan H, Matsuda T, Fujii T, Yahagi N. Cold polypectomy techniques for diminutive polyps in the colorectum. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Gilbert DA, DiMarino AJ, Jensen DM, Katon RM, Kimmey MB, Laine LA, MacFaydyen BV, Michaletz-Onody PA, Zuckerman G. Status evaluation: biliary stents. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Technology Assessment Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:750-752. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Metz AJ, Moss A, McLeod D, Tran K, Godfrey C, Chandra A, Bourke MJ. A blinded comparison of the safety and efficacy of hot biopsy forceps electrocauterization and conventional snare polypectomy for diminutive colonic polypectomy in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Waye JD. Techniques of polypectomy: hot biopsy forceps and snare polypectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:615-618. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lee CK, Shim JJ, Jang JY. Cold snare polypectomy vs. Cold forceps polypectomy using double-biopsy technique for removal of diminutive colorectal polyps: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1593-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vanagunas A, Jacob P, Vakil N. Adequacy of “hot biopsy” for the treatment of diminutive polyps: a prospective randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:383-385. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kim JS, Lee BI, Choi H, Jun SY, Park ES, Park JM, Lee IS, Kim BW, Kim SW, Choi MG. Cold snare polypectomy versus cold forceps polypectomy for diminutive and small colorectal polyps: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:741-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M, Tanaka N, Sano K, Graham DY. Removal of small colorectal polyps in anticoagulated patients: a prospective randomized comparison of cold snare and conventional polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tribonias G, Komeda Y, Voudoukis E, Bassioukas S, Viazis N, Manola ME, Giannikaki E, Papalois A, Paraskeva K, Karamanolis D. Cold snare polypectomy with pull technique of flat colonic polyps up to 12 mm: a porcine model. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:141-143. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Wadas DD, Sanowski RA. Complications of the hot biopsy forceps technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:32-37. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Komeda Y, Suzuki N, Sarah M, Thomas-Gibson S, Vance M, Fraser C, Patel K, Saunders BP. Factors associated with failed polyp retrieval at screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:395-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park SK, Ko BM, Han JP, Hong SJ, Lee MS. A prospective randomized comparative study of cold forceps polypectomy by using narrow-band imaging endoscopy versus cold snare polypectomy in patients with diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:527-532.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): C

Grade C (Good): D

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Koker IH, Mori Y, Saligram S S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF