Published online Nov 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9229

Peer-review started: June 3, 2016

First decision: July 12, 2016

Revised: June 21, 2016

Accepted: August 23, 2016

Article in press: August 23, 2016

Published online: November 7, 2016

Processing time: 156 Days and 22.1 Hours

Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) with concurrent occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) of the liver is very rare. Only 8 cases have been reported in the literature. Concurrent occurrence of HCC and NEC in the liver is classified as combined type or collision type by histological distributional patterns; only 2 cases have been reported. Herein, we report a case of collision type concurrent occurrence of HCC and NEC, in which primary hepatic NEC was in only a small portion of the nodule, which is different from the 2 previously reported cases. A 72-year-old male with chronic hepatitis C was admitted to our hospital for a hepatic mass detected by liver computed tomography (CT) at another clinic. Because the nodule was in hepatic segment 3 and had proper radiologic findings for diagnosis of HCC, including enhancement in the arterial phase and wash-out in the portal and delay phases, the patient was treated with laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy. The pathology demonstrated that the nodule was 2.5 cm and was moderately differentiated HCC. However, a 3 mm-sized focal neuroendocrine carcinoma was also detected on the capsule of the nodule. The tumor was concluded to be a collision type with HCC and primary hepatic NEC. After the surgery, for follow-up, the patient underwent a liver CT every 3 mo. Five multiple nodules were found in the right hepatic lobe on the follow-up liver CT 6 mo post-operatively. As the features of the nodules in the liver CT and MRI were different from that of HCC, a liver biopsy was performed. Intrahepatic recurrent NEC was proven after the liver biopsy, which showed the same pathologic features with the specimen obtained 6 mo ago. Palliative chemotherapy with a combination of etoposide and cisplatin has been administered for 4 months, showing partial response.

Core tip: Only 2 cases of collision tumor of hepatocellular carcinoma and primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma involving the liver have been reported in the literature. This case shows different clinical characteristics from the previous cases. And we analyzed total 8 previous cases reported as concurrent occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma. This report will be helpful to elucidate the features of collision tumors.

- Citation: Choi GH, Ann SY, Lee SI, Kim SB, Song IH. Collision tumor of hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma involving the liver: Case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(41): 9229-9234

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i41/9229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9229

Although the liver is the most common metastatic lesion of NEC, primary NEC is very rare[1]. The concurrent occurrence of NEC and HCC in the liver is extremely rare with only 8 cases reported[2-9]. They are classified as combined type or collision type based on the presentation of histological distribution. Only 2 cases of the collision type have been reported. Here, we report a rare case of a NEC and HCC collision tumor in the liver of a chronic hepatitis C patient, and we discuss the previous 8 cases.

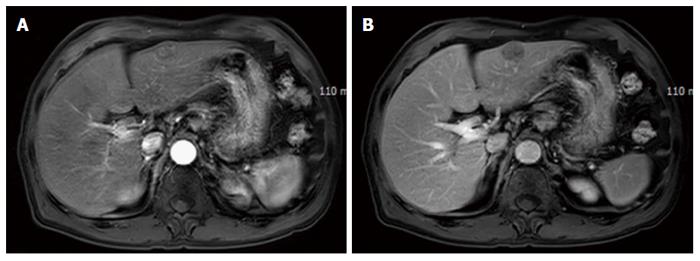

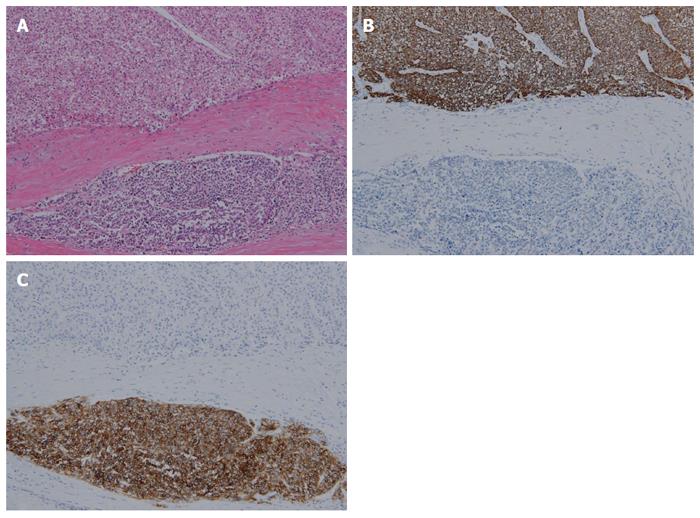

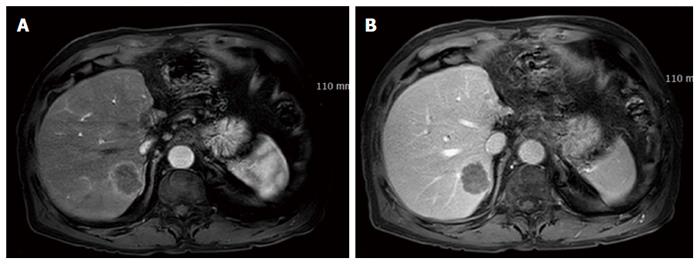

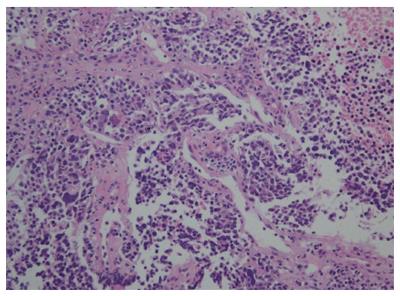

A 72-year-old man presented with a hepatic mass that had been detected by liver computed tomography (CT) at another clinic. The patient had a 3-year history of chronic hepatitis C without treatment but with regular check-ups. His initial vital signs were stable. He had no specific symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, body weight loss, or jaundice. A complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 3310/μL, hemoglobin of 16.0 g/dL, and a platelet count of 191000 /μL. Serum chemistry test results showed normal ranges of total protein 7.4 g/dL, albumin 4.2 g/dL, and total bilirubin 0.65 mg/dL. However, the levels of serum aspartate transaminase (AST) 141 IU/L and alanine transaminase (ALT) 140 IU/L were elevated. A coagulation test was within normal limits, including international normalized ratio (INR) 0.92. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was 3.8 ng/mL, but protein induced by vitamin K antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) was very high at 1059 mAU/mL. Viral markers showed negative serum hepatitis B surface antigen/antibody (HBsAg/anti-HBs) and positive serum hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV). His serum HCV RNA titer was 77464503 IU/mL with 1b genotype. The prior liver CT revealed a 2.2 cm × 2.0 cm sized nodule in hepatic segment 3, which featured mild external protrusion. It also showed slight enhancement compared to the surrounding liver parenchyma with a subtle border in the arterial phase, and low density with clear border in the portal and delayed phases after wash-out of the contrast medium. Additional dynamic liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed greater enhancement than the CT scan in the arterial phase, and low density after wash-out of the contrast medium, similar to the CT scan in the portal and delay phases (Figure 1). Therefore, the patient proceeded to undergo laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy under a diagnosis of HCC. The actual size of the nodule was 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm. Pathology demonstrated that the nodule was mostly moderately differentiated HCC with clear cytoplasm and positive immunohistochemical staining for hepatocyte paraffin-1, CD31, and CD34. A 3 mm-sized focal neuroendocrine differentiation was also detected and was separated by a fibrous band within one nodule. Cells obtained from this portion featured little cytoplasm, a high nucleus/cytoplasm (N/C) ratio, and salt and pepper chromatin in their nuclei (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry and special staining were negative for hepatocyte paraffin-1, CD31, and CD34 but positive for CD56 (Figure 2B and C). The mitotic count was 20 mitoses per 10 high power fields (20/10 HPF), so high grade NEC was diagnosed. After the surgery, the patient was followed-up with a liver CT every 3 mo. Five multiple nodules were found in the right hepatic lobe in a follow-up liver CT 6 months post-operatively. The nodules were presumed not to be HCC but another different tumor, as the largest one was 3.3 cm in size with rim enhancement and no other enhancement on liver CT and on liver MRI (Figure 3). Fine-needle aspiration guided by ultrasound revealed the lesion to be consistent with high grade NEC, and it showed the same pathologic features with the specimen obtained 6 mo ago (Figure 4). To exclude metastatic NEC from other organs, gastrofibroscopy, colonoscopy and chest CT were performed; there was no evidence of another origin site in the examinations. Eventually, recurrent NEC was proven after collision tumor of HCC and primary hepatic NEC surgery. Palliative chemotherapy with a combination of etoposide and cisplatin has been administered for 4 mo, showing partial response.

Concurrent occurrence of two different tumors in the liver is classified as combined type or collision type by histological distribution. It can present as a combined tumor in which components of both tumors intermingle and cannot be clearly separated in the transitional area within a single tumor nodule. A collision tumor shows two histologically distinct tumors involving the same organ with no histologic admixture. They co-exist with distance or adherence, in which the tumors are separated by a fibrous band. The combined type of HCC plus cholangiocarcinoma is most common, representing 2.0% to 3.6% of all primary hepatic malignancies[10].

In contrast to the HCC plus cholangiocarcinoma type in the liver, the concurrent occurrence of HCC and NEC is rarer because the incidence of primary hepatic NEC is very rare in contrast to occasional intrahepatic metastasis of NEC. Only 8 cases have been reported in the literature (Table 1)[2-9]. The 8 cases include 6 cases of the combined type and 2 cases of the collision type. In the present case, it was difficult to classify the tumor as a combined or collision type. The collision type is definitively distinguished by a fibrous band without a transition zone. In comparison with other collision types in which each tumor has some volume, the volume of the NEC portion in the present case was small (only 3 mm). However, it is still reasonable to consider collision type rather than combined type because of the presence of a fibrous band between the two tumors without a transition zone.

| Ref. | Age/sex | Clinical manifestations | Underlying liver disease | Tumor size | Type | Treatment | Survival |

| Barsky/1984[4] | 43/M | RUQ swelling | Hepatitis B | Huge1 | Combined | Chemotherapy | 26 mo |

| Artopoulos/1994[5] | 69/M | RUQ pain | Hepatitis B | 10 cm | Combined | Operation | NM |

| Vora/1999[6] | 63/M | Abdominal pain and jaundice | Liver cirrhosis | 10 cm | Combined | Operation | Died during admission |

| Ishida/2003[3] | 72/M | No symptom | Hepatitis C | 3 cm, 1.5 cm | Collision | Operation | NM |

| Yamaguchi/2004[7] | 71/M | No symptom | Hepatitis C | 4.1 cm2, 4.5 cm3 | Combined | Operation | NM |

| Garcia/2006[2] | 50/M | No symptom | Hepatitis C | 5 cm | Collision | Operation and chemotherapy | NM |

| Yang/2009[8] | 65/M | Epigastric pain | Hepatitis B | 7.5 cm | Combined | Operation | Died after 1 yr |

| Aboelenen/2014[9] | 51/M | Abdominal pain | Hepatitis C | 7.5 cm | Combined | Operation | No recurrence up to 6 mo |

The present case involved a patient with chronic hepatitis C, as did the other 2 reported cases of the collision type. Garcia et al[2] reported a case of collision type tumor with HCC and primary hepatic NEC in a 50-year-old male patient. The tumor was 5 cm in size. The tumor was 70% NEC and 30% HCC, which differed from the present case. A similarity was the division of the tumors by a fibrous band in microscopic examination[2]. On the other hand, the case reported by Ishida et al[3] showed different features from the other cases in that the collision type tumor occurred in other hepatic segments: the 3 cm NEC and the 1.5 cm HCC were in segment 8 and segment 5, respectively.

With both the combined and collision type, it is important to make a clear distinction between primary intrahepatic NEC and metastatic NEC from extrahepatic organs because the incidence of primary intrahepatic NEC is rare. Surveys and evaluations to rule out metastatic NEC were essential in the case reported by Garcia et al[2] because the tumors developed in different hepatic segments. On the other hand, in the present case, it was difficult to consider the NEC as a metastatic lesion because the HCC and NEC regions existed within the same capsule separated only by a fibrous band.

The previous 8 cases of concurrent HCC and primary hepatic NEC all featured male patients with underlying liver disease, involving chronic hepatitis C in 4 cases, chronic hepatitis B in 3 cases, and cirrhosis of unknown cause in one case. The age distribution included the 40 s (one case), 50 s (2 cases), 60 s (3 cases), and 70 s (3 cases). More frequent diagnosis with age is evident. Surgery was performed after the diagnosis in 7 cases (Table 1).

The histogenesis of primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) is unclear. There are two theories. One is that such tumors originate from neuroendocrine cells in the intrahepatic bile duct epithelium. The other is that stem cell precursors of malignant cells from another hepatic malignant tumor differentiate into a neuroendocrine tumor[11,12]. The first theory can explain the histogenesis when there is no other malignant tumor in the liver but only for primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors. The second theory is more convincing in the case of concurrent occurrence of HCC and primary hepatic NET, whether combined or collision type. The combined type is more amenable to the second theory because the two types of malignant cells mingle in the transition zone.

There has been no established treatment for the combined and collision types because few cases have been reported. Although it is difficult to find out which tumor (HCC or NEC) determines the poor prognosis of the disease, previous cases and our case implicate NEC in the poor prognosis due to its aggressive course, which can include metastasis. Another reason for the association of NEC with poor prognosis is the relatively short survival time of patients, even with regular liver ultrasonography or liver CT for surveillance of their underlying liver disease, such as chronic viral hepatitis, and early surgical management. Consequently, when the pathologic grade of NEC is high, adjuvant chemotherapy is needed to increase life expectancy whereas NEC was small as in this case.

In summary, we experienced a case of concurrent occurrence of HCC and NEC collision type in a chronic hepatitis C patient with multiple intrahepatic metastases 6 mo after the surgical procedure in spite of the very small size of the NEC, which had been completely removed. In consideration of the present case and previous cases, aggressive chemotherapy is necessary in concurrent occurrence of HCC and NEC. More cases need to be documented to better define treatment.

Neuroendocrine carcinoma recurred at 6 mo after operation for collision tumor of hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor in 72-year-old man with chronic hepatitis C.

A few hepatic masses that was detected by liver computed tomography during follow-up after operation.

Hepatocellular carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, hepatic metastasis of other malignancy.

There was no specific laboratory findings for recurred neuroendocrine carcinoma.

The largest mass was 3.3 cm in size with rim enhancement and no other enhancement on the liver CT and the liver MRI.

The pathology showed little cytoplasm, high nucleus/cytoplasm (N/C) ratio, and salt and pepper chromatins in their nuclei with positive for CD56.

Chemotherapy with a combination of etoposide and cisplatin.

The concurrent occurrence of NEC and hepatocellular carcinoma in the liver are classified as combined type and collision type. Only 2 cases of the collision type and 6 cased of combined type have been reported.

Combined type -components of both tumors intermingle and cannot be clearly separated in the transitional area within a single tumor nodule.

Please summarize experiences and lessons learnt from the case in one sentence. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be done for collision or combined tumor of hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma although the portion of neuroendocrine carcinoma is very small.

Good job. Very rare case actually.

| 1. | Kaya G, Pasche C, Osterheld MC, Chaubert P, Fontolliet C. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the liver: an autopsy case. Pathol Int. 2001;51:874-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Garcia MT, Bejarano PA, Yssa M, Buitrago E, Livingstone A. Tumor of the liver (hepatocellular and high grade neuroendocrine carcinoma): a case report and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ishida M, Seki K, Tatsuzawa A, Katayama K, Hirose K, Azuma T, Imamura Y, Abraham A, Yamaguchi A. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma coexisting with hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C liver cirrhosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:214-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Barsky SH, Linnoila I, Triche TJ, Costa J. Hepatocellular carcinoma with carcinoid features. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:892-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Artopoulos JG, Destuni C. Primary mixed hepatocellular carcinoma with carcinoid characteristics. A case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:442-444. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Vora IM, Amarapurkar AD, Rege JD, Mathur SK. Neuroendocrine differentiation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:37-38 [PMID 10659491]. |

| 7. | Yamaguchi R, Nakashima O, Ogata T, Hanada K, Kumabe T, Kojiro M. Hepatocellular carcinoma with an unusual neuroendocrine component. Pathol Int. 2004;54:861-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang CS, Wen MC, Jan YJ, Wang J, Wu CC. Combined primary neuroendocrine carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma of the liver. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:430-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aboelenen A, El-Hawary AK, Megahed N, Zalata KR, El-Salk EM, Fattah MA, Sorogy ME, Shehta A. Right hepatectomy for combined primary neuroendocrine and hepatocellular carcinoma. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jarnagin WR, Weber S, Tickoo SK, Koea JB, Obiekwe S, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Blumgart LH, Klimstra D. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: demographic, clinical, and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2002;94:2040-2046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pilichowska M, Kimura N, Ouchi A, Lin H, Mizuno Y, Nagura H. Primary hepatic carcinoid and neuroendocrine carcinoma: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of five cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gould VE, Banner BF, Baerwaldt M. Neuroendocrine neoplasms in unusual primary sites. Diagn Histopathol. 1981;4:263-277. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Sirin G, Wang GY S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH