Published online Mar 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.3038

Peer-review started: March 20, 2015

First decision: June 2, 2015

Revised: June 12, 2015

Accepted: November 13, 2015

Article in press: November 13, 2015

Published online: March 14, 2016

Processing time: 351 Days and 7.9 Hours

AIM: To identify the prognostic value of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

METHODS: A search was performed for relevant publications in PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science databases. The pooled effects were calculated from the available information to identify the relationship between HBV or HCV infection and the prognosis and clinicopathological features. The χ2 and I2 tests were used to evaluate heterogeneity between studies. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by a fixed-effects model, if no heterogeneity existed. If there was heterogeneity, a random-effects model was applied.

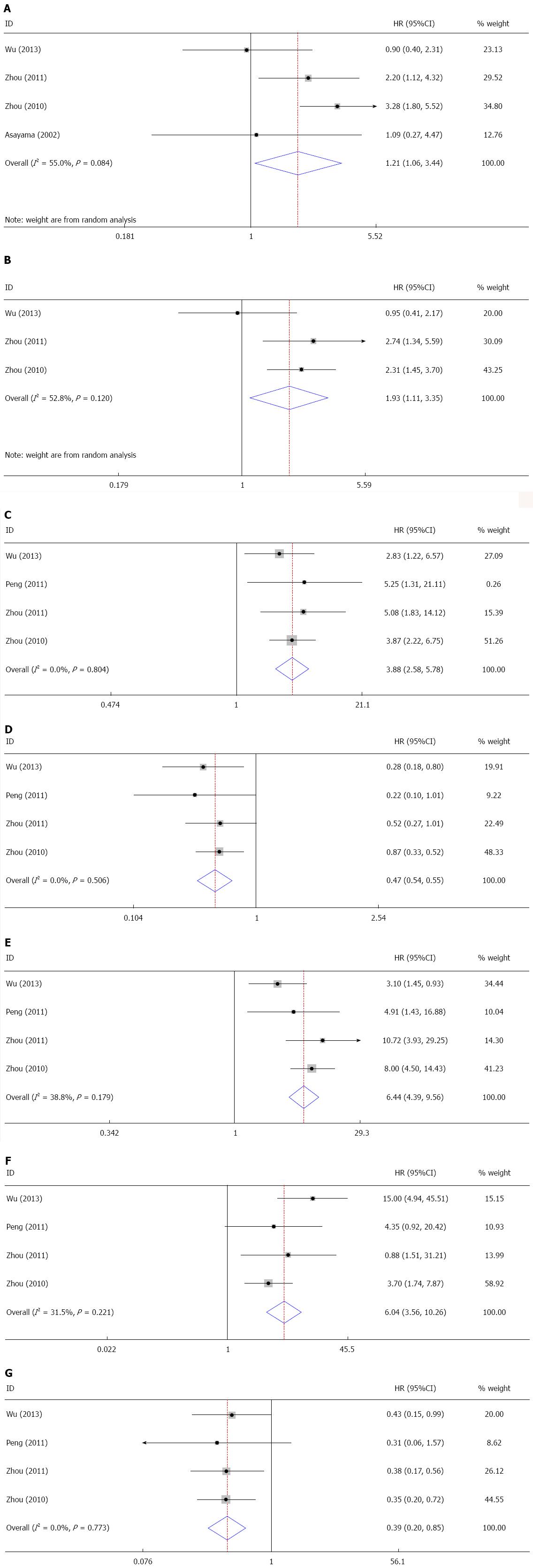

RESULTS: In total, 14 studies involving 2842 cases were enrolled in this meta-analysis. The patients with HBV infection presented better overall and disease-free survival, and the pooled HRs were significant at 0.76 (95%CI: 0.70-0.83) and 0.78 (95%CI: 0.66-0.94), respectively. Additionally, our study revealed that HCV infection was correlated with shortened overall survival in comparison with the control group (HR = 2.64, 95%CI: 1.77-3.93). We also found that HBV infection occurred more frequently in male patients [odds ratio (OR) = 1.91, 95%CI: 1.06-3.44] and was correlated with higher levels of serum aspartate transaminase (AST) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (OR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.11-3.35; OR = 3.86, 95%CI: 2.58-5.78) and a lower level of serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) (OR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.34-0.65). Moreover, HBV infection was associated with cirrhosis (OR = 6.44, 95%CI: 4.33-9.56), a higher proportion of capsule formation (OR = 6.04, 95%CI: 3.56-10.26), and a lower rate of lymph node metastasis (OR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.25-0.58). No significant publication bias was seen in any of the enrolled studies.

CONCLUSION: HBV infection may indicate a favorable prognosis in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, while HCV infection suggests a poor prognosis.

Core tip: This research is the first comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review to identify the prognostic significance of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. According to this study, HBV infection predicted a favorable prognosis; however, HCV infection was correlated with shortened overall survival. These findings will provide useful information for clinical decision-making in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

- Citation: Wang Z, Sheng YY, Dong QZ, Qin LX. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus play different prognostic roles in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(10): 3038-3051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i10/3038.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.3038

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is one of the common hepatic malignancies, especially in China[1]. The incidence and mortality rates of ICC have been increasing globally in recent decades[2-4]. Despite advancements in diagnostic methods and surgical approaches, the survival rates for ICC patients remain unfavorable[5,6]. The peak incidence for ICC occurs between 55 and 75 years old. Unlike hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is more prevalent in men, ICC appears to have only a slight male predominance[7]. Surgical treatment remains the only cure for ICC; unfortunately, most patients present with an advanced stage of disease.

Apart from classic risk factors, such as liver flukes, researchers have reported other risk factors, including alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatitis viruses, tobacco and metabolic diseases[4]. Hepatitis viruses, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), are the causative agents for HCC. Recent studies also revealed that both HBV and HCV infections are the causative agents for ICC[8,9], which may help explain the increasing incidence of ICC.

ICC has a worse prognosis than HCC; this is mainly due to several clinicopathological features, such as frequent lymph node invasion and a low proportion of capsule formation, which are more frequent in HBV-infected ICC cases[10]. Recently, studies in China have demonstrated that HBV infection could be used as a predictive marker of favorable prognosis[11,12]; however, several researchers have reported that hepatitis virus infection has no impact on prognosis after hepatectomy[13,14]. Thus, the prognostic significance of HBV and HCV infections in ICC patients remains controversial.

In this research, a meta-analysis of correlative publications was performed to identify the prognostic value of HBV or HCV infection in ICC cases.

This study was performed according to PRISMA guidelines[15]. PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science databases were searched comprehensively for relevant publications before January 1, 2015. We used the following terminologies in all possible combinations without restrictions: “hepatitis B virus”, “hepatitis C virus”, “HBV”, “HCV”, “intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma”, “ICC”, “prognosis”, “prognostic”, “survival”, “clinical”, and “clinicopathological.” We scanned the reference lists of relevant publications for additional available researches.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) articles were written in English; (2) patients were diagnosed with ICC by pathology; (3) HBV or HCV infection was detected; and (4) sufficient information about HBV or HCV infection, overall survival (OS) or disease-free survival (DFS) and other clinicopathological parameters was given directly or could be calculated indirectly.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) non-English articles; (2) reviews, letters, case studies and conference records; and (3) duplicated data of previous research.

Two reviewers assessed the quality of the retrieved studies independently in accordance with the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS)[16]. The NOS is composed of three dimensions: selection, comparability, and outcome. The publication was not included in our review if its quality score was too low.

Two reviewers independently scanned the eligible publications and extracted the original information from the included papers. All publications were double-checked and disagreements were settled by discussion. For each research, the following data were recorded: (1) the first author name and year of publication; (2) the number of cases; (3) the study design; (4) the clinical parameters, including age, gender, clinical stage, treatment and other clinicopathological features; (5) the markers detected for HBV and HCV infections; and (6) the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of HBC or HCV infection for OS and DFS. If the HR was unavailable, we used the total number of deaths and the total number of cases to calculate the HR. If the information was only available in Kaplan-Meier curves, we obtained the HR with Engauge Digitizer according to Parmar et al[17].

The statistical software Stata version 12.0 was used to synthesize the outcomes of the enrolled studies. The HR and 95%CI from each paper were applied for calculating pooled HR. The χ2 and I2 tests were used to evaluate heterogeneity between the studies, and P < 0.05 was defined as statistical significance. If there was no heterogeneity (P≥ 0.05), a fixed-effects model was used, and a random-effects model was applied if there was heterogeneity (P < 0.05). Egger’s test and Begg’s funnel plot were applied to assess publication bias.

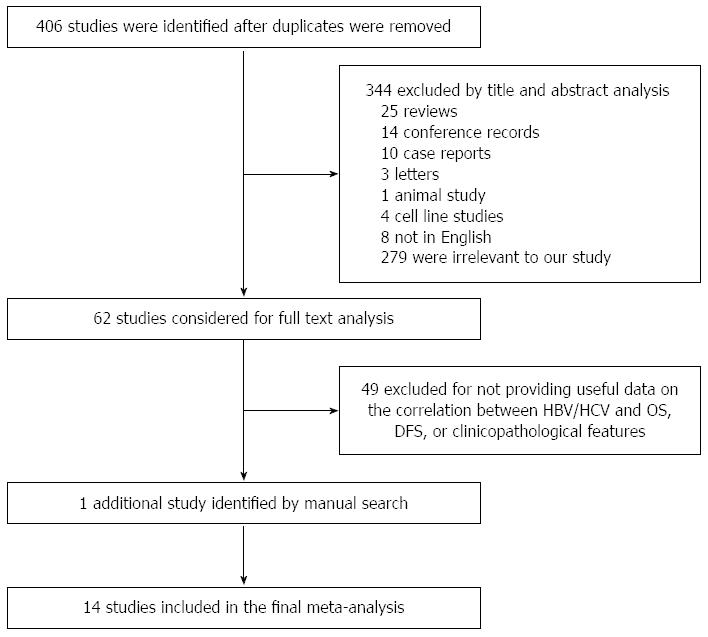

A flowchart demonstrating the publication search and selection process is shown in Figure 1. Four hundred and six potentially eligible papers were retrieved in the initial search. According to the titles and abstracts, 344 publications (25 reviews, 14 conference records, 10 case reports, 3 letters, 1 animal study, 4 cell line studies, 8 non-English publications and 279 papers that had no relationship with our study) were excluded. Sixty-two full articles were captured, among which 49 were finally excluded due to the paucity of sufficient information on HBV/HCV and OS, DFS, or clinicopathological features. One additional paper was identified by manual search. Ultimately, our review enrolled a total of 14 studies. Of these publications chosen for further assessment, 13 investigated the correlation between HBV and specific parameters, and 5 studied the relationship between HCV and survival and clinicopathological features.

The main characteristics of each enrolled publication are shown in Table 1. In total, 14 studies involving 2842 cases were enrolled in the present research. The papers included in our study were published between 2002 and 2014. Eight papers enrolled less than 100 cases, and six papers enrolled more than 100 cases. The mean age of the enrolled patients ranged from 51.0 to 62.0 years in these studies. One study was prospective, and the other 13 were well-designed, retrospective studies.

| Study | Study region | n | Mean age | Gender (M/F) | Clinical stage | Study design | Tumor type | Marker detection | Clinicopathological features | HR | Outcome | Quality assessment |

| Li et al[26], 2014 | China | 283 | 55.0 (18.0–79.0) | 174/109 | I-IV | Prospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg | NR | R | OS | 8 |

| Luo et al[27], 2014 | China | 1333 | 54.1 ± 10.9 | 912/421 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF | HBsAg/anti-HCV | NR | R | OS | 9 |

| Uenishi et al[28], 2014 | Japan | 90 | NR | 61/29 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF | HBsAg/anti-HCV | G | R | OS | 9 |

| Zhang et al[29], 2014 | China | 127 | 55.5 ± 11.8 | 102/25 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg/anti-HCV | NR | R | OS/DFS | 9 |

| Liu et al[30], 2013 | China | 81 | 59.0 (30.0-76.0) | 48/33 | NR | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg/HBcAb | NR | R | OS | 9 |

| Wu et al[31], 2013 | China | 138 | 55 | 107/31 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg/HBcAb | G, ALT, AST, TB, γ-GT, AFP, CA19-9, C, CF, D, TN, TS, LNM, VI | E | OS | 8 |

| Jiang et al[32], 2011 | China | 76 | 51.0 (40.0–60.0) | 53/23 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg | NR | R | OS | 9 |

| Peng et al[33], 2011 | China | 62 | NR | NR | NR | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg/HBcAb | AFP, CA19-9, C, CF, D, TL, TN, TS, LNM, VI | NR | NR | 8 |

| Uenishi et al[34], 2011 | Japan | 35 | 61.0 (35.0-83.0) | 11/24 | II-IV | Retrospective | MF | HBsAg/anti-HCV | NR | E | OS | 8 |

| Zhou et al[11], 2011 | China | 155 | 55.0 ± 10.7 (27.0-76.0) | 102/53 | NR | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg | G, ALT, AST, TB, γ-GT, AFP, CA19-9, C, CF, D, TL, TN, TS, LNM, VI | R | OS/DFS | 9 |

| Zhang et al[12], 2010 | China | 40 | 56.0 (34.0-74.0) | 24/16 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg/HBcAb | NR | E | OS | 8 |

| Zhou et al[10], 2010 | China | 317 | 53.1 ± 10.5 | 223/94 | NR | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg | G, ALT, AST, TB, γ-GT, AFP, CA19-9, C, CF, D, TL, TN, LNM, VI | NR | NR | 8 |

| Hai et al[13], 2005 | Japan | 38 | NR | 23/15 | I-IV | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | anti-HCV | G | E | OS | 8 |

| Asayama et al[35], 2002 | Japan | 67 | 62.0 (33.0-83.0) | 36/31 | NR | Retrospective | MF/PI/IG | HBsAg/anti-HCV | G | E | OS | 8 |

Each of the included studies in our review was evaluated in accordance with the NOS standard. A study with a quality value of 6 stars or more was of high quality. According to the NOS, all publications enrolled in our study were high-quality studies (Table 1).

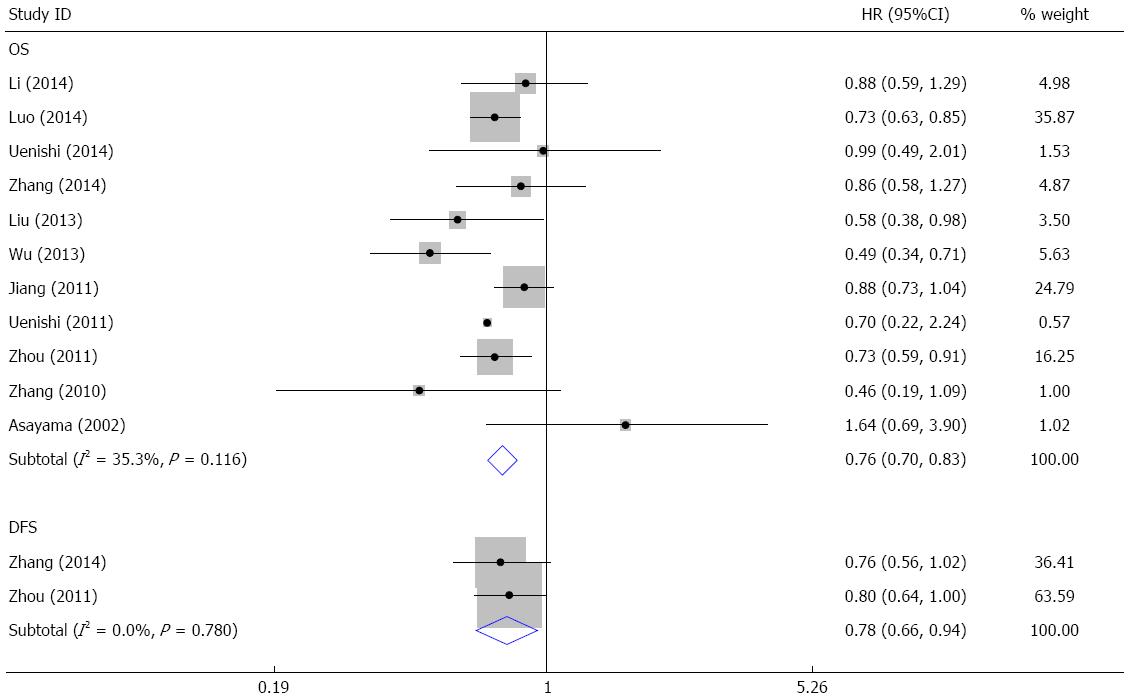

The meta-analysis evaluating the relationship between HBV infection and OS was performed on 11 studies. The pooled HR was 0.76 (95%CI: 0.70-0.83, Z = 6.14, P = 0.000) (Figure 2), and no heterogeneity existed (I2 = 35.3%, P = 0.116). Two studies assessed the association of HBV infection with DFS; the pooled HR was 0.78 (95%CI: 0.66-0.94, Z = 2.67, P = 0.008) (Figure 2) without heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.780). These results indicated that patients with HBV infection had longer OS and DFS.

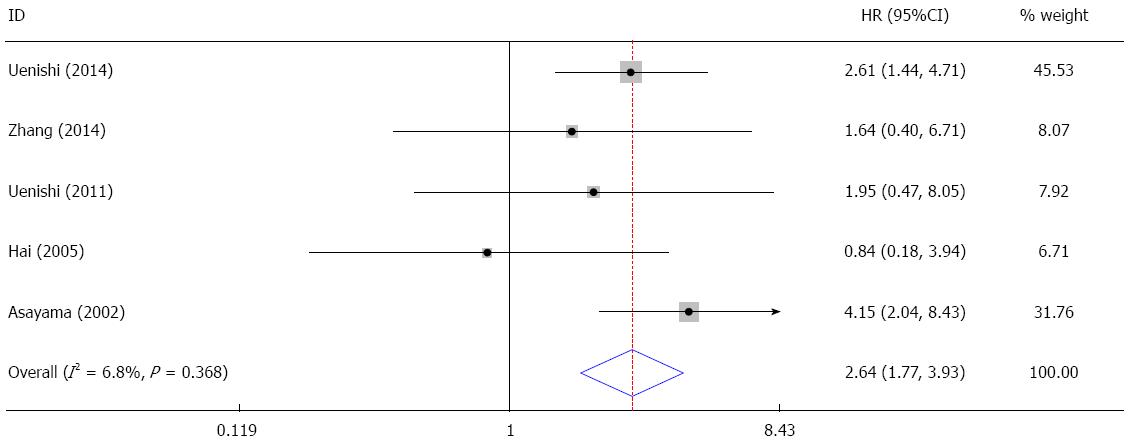

In the five studies evaluating the correlation between HCV infection and OS, no significant heterogeneity was found (I2 = 6.8%, P = 0.368). The pooled HR was 2.64 (95%CI: 1.77-3.93, Z = 4.76, P = 0.000), suggesting that patients with HCV infection had a poorer prognosis (Figure 3).

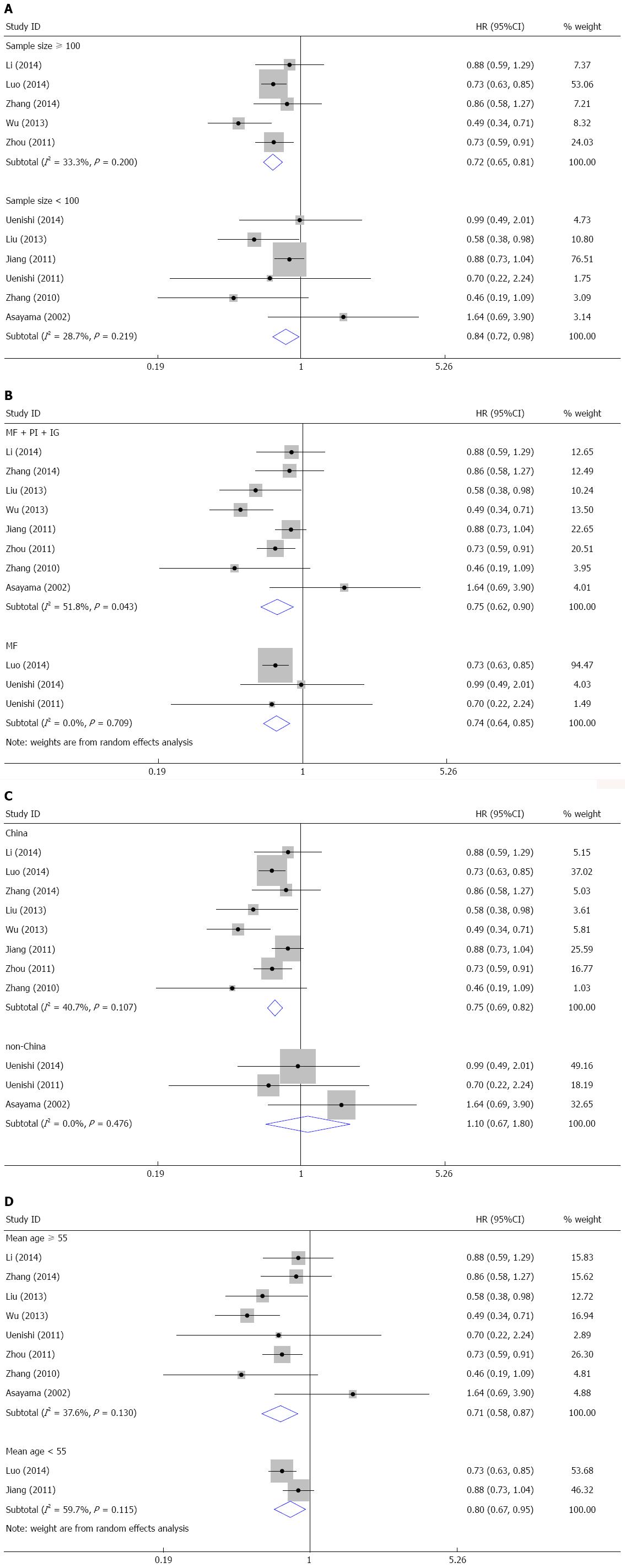

The subgroup meta-analysis was carried out for the relationship between HBV infection and OS (Table 2). When stratified by sample size, the pooled HRs were 0.72 (95%CI: 0.65-0.81) for studies with more than 100 subjects and 0.84 (95%CI: 0.72-0.98) for studies with less than 100 subjects (Figure 4A). This finding indicated that HBV infection was a favorable prognostic marker regardless of sample size. When stratified by tumor type, HBV infection was a favorable prognostic marker for mass-forming ICC (HR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.62-0.90) and ICC without tumor-type restriction (HR = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.64-0.85) (Figure 4B). When stratified by study region, HBV infection was a favorable predictor for Chinese patients (HR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.69-0.82), but not for patients in other countries (HR = 1.10, 95%CI: 0.67-1.80) (Figure 4C). In the subgroup analysis by mean age, the pooled HRs were 0.71 (95%CI: 0.58-0.87) for patients with a mean age more than 55 and 0.80 (95%CI: 0.67-0.95) for patients with a mean age less than 55 (Figure 4D). These results suggest that HBV infection indicates a favorable prognosis regardless of patient age.

| Subgroup | n | Analytical model | HR | 95%CI | Heterogeneity | |

| I2(%) | P value | |||||

| Sample size | ||||||

| Sample size ≥ 100 | 5 | FEM | 0.72 | 0.65-0.81 | 33.3 | 0.200 |

| Sample size < 100 | 6 | FEM | 0.84 | 0.72-0.98 | 28.7 | 0.219 |

| Tumor type | ||||||

| MF, PI or IG | 8 | REM | 0.75 | 0.62-0.90 | 51.8 | 0.043 |

| MF only | 3 | FEM | 0.74 | 0.64-0.85 | 0.00 | 0.709 |

| Study region | ||||||

| China | 8 | FEM | 0.75 | 0.69-0.82 | 40.7 | 0.107 |

| Non-China | 3 | FEM | 1.10 | 0.67-1.80 | 0.00 | 0.476 |

| Mean age | ||||||

| Mean age ≥ 55 | 8 | FEM | 0.71 | 0.62-0.82 | 37.6 | 0.130 |

| Mean age < 55 | 2 | REM | 0.80 | 0.67-0.95 | 59.7 | 0.115 |

An analysis of the pooled data revealed that HBV infection in ICC patients was associated with specific clinicopathological features (Table 3). Four of the studies assessed the association of HBV infection with gender and the pooled OR was 1.91 (95%CI: 1.06-3.44) (Figure 5A). This finding suggests that HBV infection occurs more commonly in male patients. Three studies evaluated the correlation between HBV infection and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels. The pooled OR (1.93, 95%CI: 1.11-3.35) showed that HBV infection was associated with elevated AST (Figure 5B). Four of the studies investigated the relationship between HBV infection and tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9). The results demonstrate that HBV-infected cases had a higher level of AFP (OR = 3.86, 95%CI: 2.58-5.78) and a lower incidence of CA19-9 (OR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.34-0.65) compared to the control group (Figure 5C, D). Additionally, four publications identified an association between HBV infection and cirrhosis; the pooled OR was 6.44 (95%CI: 4.33-9.56), which indicates that HBV infection was correlated with cirrhosis (Figure 5E). When performing a meta-analysis of HBV infection and tumor capsule formation, we found that HBV infection was correlated with a higher proportion of capsule formation (OR = 6.04, 95%CI: 3.56-10.26) (Figure 5F). Moreover, it was found that lymph node metastasis occurred less in patients (OR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.25-0.58) (Figure 5G).

| Clinicopathological features | n | Cases | Analytical model | OR | 95%CI | Heterogeneity | |

| I2(%) | P value | ||||||

| Gender (male vs female) | 4 | 677 | REM | 1.91 | 1.06-3.44 | 55.0 | 0.084 |

| ALT (≥ 42 U/L vs < 42 U/L) | 3 | 610 | REM | 1.23 | 0.64-2.35 | 63.3 | 0.066 |

| AST (≥ 37 U/L vs < 37 U/L) | 3 | 610 | REM | 1.93 | 1.11-3.35 | 52.8 | 0.120 |

| TBIL(≥ 20 μmol/L vs < 20 μmol/L) | 3 | 610 | FEM | 0.91 | 0.62-1.33 | 0.00 | 0.979 |

| γ-GT (≥ 64 U/L vs < 64 U/L) | 3 | 610 | REM | 0.77 | 0.43-1.38 | 61.7 | 0.074 |

| AFP (≥ 20 ng/mL vs < 20 ng/mL) | 4 | 669 | FEM | 3.86 | 2.58-5.78 | 0.00 | 0.804 |

| CA19-9 (≥ 37 U/mL vs < 37 U/mL) | 4 | 668 | FEM | 0.47 | 0.34-0.65 | 0.00 | 0.806 |

| Cirrhosis (yes vs no) | 4 | 672 | FEM | 6.44 | 4.33-9.56 | 38.8 | 0.179 |

| Capsule formation (yes vs no) | 4 | 672 | FEM | 6.04 | 3.56-10.26 | 31.9 | 0.221 |

| Differentiation (well/moderate vs poor) | 4 | 672 | REM | 0.86 | 0.41-1.80 | 73.5 | 0.010 |

| Tumor location (both lobes vs one lobe) | 3 | 534 | FEM | 0.76 | 0.31-1.87 | 0.00 | 0.995 |

| Tumor number (multiple vs single) | 4 | 672 | FEM | 0.91 | 0.57-1.46 | 0.00 | 0.983 |

| Tumor size (≥ 5 cm vs < 5 cm) | 3 | 355 | FEM | 0.72 | 0.46-1.14 | 37.9 | 0.200 |

| Lymph node metastasis (yes vs no) | 4 | 672 | FEM | 0.39 | 0.25-0.58 | 0.00 | 0.990 |

| Vascular invasion(yes vs no) | 4 | 672 | REM | 1.10 | 0.49-2.43 | 69.0 | 0.021 |

We also found that HBV infection had no relation to ALT level, TBIL level, γ-GT level, tumor differentiation, tumor location, tumor number, tumor size or vascular invasion. The pooled ORs were 1.23 (95%CI: 0.64-2.35), 0.91 (95%CI: 0.62-1.33), 0.77 (95%CI: 0.43-1.38), 0.86 (95%CI: 0.41-1.80), 0.76 (95%CI: 0.31-1.87), 0.91 (95%CI: 0.57-1.46), 0.72 (95%CI: 0.46-1.14) and 1.10 (95%CI: 0.49-2.43), respectively (Table 3).

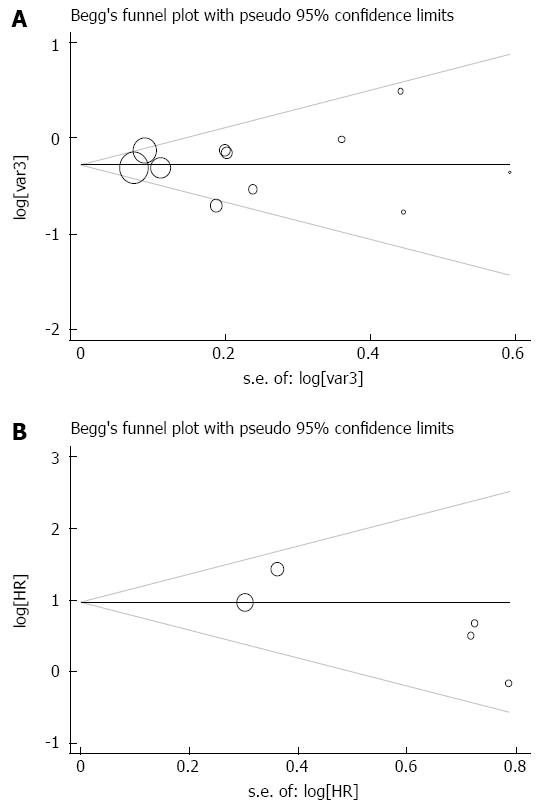

There was no publication bias for the meta-analysis of the impact of HBV infection on patient survival (Begg’s test, P = 0.938; Egger’s test, P = 0.923) (Figure 6A). Additionally, no publication bias existed for studies regarding HCV infection and overall survival in this research (Begg’s test, P = 0.142; Egger’s test, P = 0.157) (Figure 6B).

Because surgical operation remains the only cure for ICC, it is vital to identify the potential prognostic predictors; however, it remains unclear whether HBV and HCV infections, believed to be the causative agents for ICC[8], increase the risk of cancer recurrence and death. This meta-analysis is the first comprehensive and detailed research to identify the correlation of HBV/HCV infections with patient survival and clinicopathological features. Our study suggests that HBV infection predicts a favorable prognosis in ICC patients, and infection with HCV indicates a poorer prognosis. In accordance with our findings, we believe that this meta-analysis will provide beneficial information for clinical decision-making in ICC cases.

The presence of lymph node invasion is believed as an important prognostic marker in ICC patients that underwent hepatic operation[18,19]. Our study found that lymph node metastasis occurred less frequently in patients with HBV infection, which partially explains why HBV infection was a favorable prognostic predictor for ICC. We also found that patients with HBV infection had a higher incidence of AFP elevation and a lower rate of CA19-9 elevation. Recent studies have reported that viral-associated ICC shares a similar tumor process to HCC. Furthermore, both cancers originate from hepatic progenitor cells (HPC), which have the ability to produce alpha-fetoprotein[10,20]. Several studies have also suggested that serum CA19-9 is correlated with tumor burden and predicts the high probability of tumor recurrence and shorter overall survival in ICC[21-23]. Therefore, we believe that virus-associated ICC, unlike ICCs caused by other risk factors, shares more common clinicopathological features with virus-associated HCC, which accounts for the prognostic difference between patients with and without hepatitis virus infection. In addition, our study shows that HBV infection was correlated with a higher prevalence of AST levels and cirrhosis, which could be interpreted as HBV causing hepatic damage and leading to liver cirrhosis.

Our results demonstrate that HCV infection is an adverse prognostic marker for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The first possible explanation for this result is the high frequency of synchronous HCC in ICC cases[24]. The second possible reason is that the operation risk and perioperative mortality in HCV-infected cases are higher than those without infection. Third, some patient deaths may be caused by HCV-related chronic hepatic disease, not by tumor malignancy.

Furthermore, we performed a subgroup analysis for the correlation between HBV infection and overall survival in ICC patients. The results showed that HBV infection predicted a favorable outcome, regardless of sample size, tumor type or patient age, which makes this prognostic predictor and surveillance marker more applicable. We also found that HBV infection was a more favorable prognostic indicator in Chinese patients than in patients from other countries. Because the incidence of hepatitis virus infection and ICC varies between countries, we expect that multi-center trials will be needed to clarify the relationship between HBV/HCV infections and the prognosis of ICC.

The NOS scale was applied to assess the quality of the enrolled publications. Only high-quality studies (NOS scale ≥ 6 points) were included to avoid the potential impact of reports without sufficient information on the reliability of our meta-analysis. Moreover, all the patients enrolled in our review were diagnosed by pathology and had at least a 3-year follow-up, which could make reporting more convincing. In addition, significant publication bias was not shown in our selected studies. Thus, our meta-analysis provides valid data and solid evidence for the clinical procedure of ICC cases.

Although we comprehensively evaluated the relationship between HBV/HCV infections and patient survival in ICC, limitations exist in this study. First, cohort studies are difficult to control for confounders, which could influence the authentic prognostic value of HBV/HCV infections in ICC. Second, most of the cases enrolled in our review were from eastern Asia, which could result in a sample bias. Considering that the incidence of ICC is much higher in eastern Asia than in the rest of the world[25], we believe that the patients enrolled in our study are representative of ICC patients. Third, a potential language bias may exist in this meta-analysis, because non-English publications were not included; however, the risk of language bias would not result in significant bias in the evaluation of interventional effectiveness.

To conclude, our research shows that HBV infection is associated with a favorable prognosis and certain clinical features in ICC, while HCV infection markedly shortens OS in ICC patients. Thus, HBV and HCV infections could be useful prognostic markers for ICC. We expect that more well-designed studies will be performed to further confirm and establish the prognostic value of HBV/HCV infections in ICC patients.

The incidence and mortality rates of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) have been increasing globally in recent decades. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are correlated with the increasing incidence rate of ICC; however, the prognostic significance of HBV and HCV infections in ICC patients remains unknown.

In this research, a meta-analysis was performed to identify the prognostic value of HBV and HCV infections in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

This research is the first comprehensive meta-analysis to identify the correlation of HBV and HCV infections with survival and clinical parameters in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

This study shows that HBV infection is related with a better prognosis and certain clinical features in ICC patients, while HCV infection is correlated with shortened overall survival in ICC patients. Thus, HBV and HCV infections could be useful prognostic markers for ICC.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is one of the common hepatic malignancies. Pathologically, it consists of altered epithelial cells which originate from the biliary system in the liver.

This is a well-performed meta-analysis of currently available studies on the prognostic role of HBV and HCV infections in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The results are interesting and suggest a favorable prognosis of ICC associated with HBV infection in comparison with HCV infection.

| 1. | Aljiffry M, Abdulelah A, Walsh M, Peltekian K, Alwayn I, Molinari M. Evidence-based approach to cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review of the current literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:134-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 804] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khan SA, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas HC. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J Hepatol. 2002;37:806-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Okuda K, Nakanuma Y, Miyazaki M. Cholangiocarcinoma: recent progress. Part 1: epidemiology and etiology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1049-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2005;366:1303-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 872] [Cited by in RCA: 908] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brown KM, Parmar AD, Geller DA. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23:231-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? J Hepatol. 2004;40:472-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 546] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Zhou Y, Zhao Y, Li B, Huang J, Wu L, Xu D, Yang J, He J. Hepatitis viruses infection and risk of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matsumoto K, Onoyama T, Kawata S, Takeda Y, Harada K, Ikebuchi Y, Ueki M, Miura N, Yashima K, Koda M. Hepatitis B and C virus infection is a risk factor for the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Intern Med. 2014;53:651-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhou H, Wang H, Zhou D, Wang H, Wang Q, Zou S, Tu Q, Wu M, Hu H. Hepatitis B virus-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma may hold common disease process for carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1056-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhou HB, Wang H, Li YQ, Li SX, Wang H, Zhou DX, Tu QQ, Wang Q, Zou SS, Wu MC. Hepatitis B virus infection: a favorable prognostic factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1292-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang L, Cai JQ, Zhao JJ, Bi XY, Tan XG, Yan T, Li C, Zhao P. Impact of hepatitis B virus infection on outcome following resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:233-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hai S, Kubo S, Yamamoto S, Uenishi T, Tanaka H, Shuto T, Takemura S, Yamazaki O, Hirohashi K. Clinicopathologic characteristics of hepatitis C virus-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Surg. 2005;22:432-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Horino K, Beppu T, Komori H, Masuda T, Hayashi H, Okabe H, Takamori H, Baba H. Evaluation of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with viral hepatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1217-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9207] [Cited by in RCA: 8359] [Article Influence: 522.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 13624] [Article Influence: 851.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815-2834. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Farges O, Fuks D, Boleslawski E, Le Treut YP, Castaing D, Laurent A, Ducerf C, Rivoire M, Bachellier P, Chiche L. Influence of surgical margins on outcome in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicenter study by the AFC-IHCC-2009 study group. Ann Surg. 2011;254:824-829; discussion 830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ribero D, Pinna AD, Guglielmi A, Ponti A, Nuzzo G, Giulini SM, Aldrighetti L, Calise F, Gerunda GE, Tomatis M. Surgical Approach for Long-term Survival of Patients With Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Multi-institutional Analysis of 434 Patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1107-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee CH, Chang CJ, Lin YJ, Yeh CN, Chen MF, Hsieh SY. Viral hepatitis-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma shares common disease processes with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1765-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Patel AH, Harnois DM, Klee GG, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:204-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Miwa S, Miyagawa S, Kobayashi A, Akahane Y, Nakata T, Mihara M, Kusama K, Soeda J, Ogawa S. Predictive factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma recurrence in the liver following surgery. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:893-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shen WF, Zhong W, Xu F, Kan T, Geng L, Xie F, Sui CJ, Yang JM. Clinicopathological and prognostic analysis of 429 patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5976-5982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Welzel TM, Graubard BI, El-Serag HB, Shaib YH, Hsing AW, Davila JA, McGlynn KA. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1221-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:115-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 839] [Cited by in RCA: 855] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li T, Qin LX, Zhou J, Sun HC, Qiu SJ, Ye QH, Wang L, Tang ZY, Fan J. Staging, prognostic factors and adjuvant therapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection. Liver Int. 2014;34:953-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Luo X, Yuan L, Wang Y, Ge R, Sun Y, Wei G. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical therapy for all potentially resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a large single-center cohort study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:562-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Uenishi T, Nagano H, Marubashi S, Hayashi M, Hirokawa F, Kaibori M, Matsui K, Kubo S. The long-term outcomes after curative resection for mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with hepatitis C viral infection: a multicenter analysis by Osaka Hepatic Surgery Study Group. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:176-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang GW, Lin JH, Qian JP, Zhou J. Identification of risk and prognostic factors for patients with clonorchiasis-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3628-3637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Liu RQ, Shen SJ, Hu XF, Liu J, Chen LJ, Li XY. Prognosis of the intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after resection: hepatitis B virus infection and adjuvant chemotherapy are favorable prognosis factors. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu ZF, Yang N, Li DY, Zhang HB, Yang GS. Characteristics of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatitis B virus infection: clinicopathologic study of resected tumours. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jiang BG, Ge RL, Sun LL, Zong M, Wei GT, Zhang YJ. Clinical parameters predicting survival duration after hepatectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:603-608. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Peng NF, Li LQ, Qin X, Guo Y, Peng T, Xiao KY, Chen XG, Yang YF, Su ZX, Chen B. Evaluation of risk factors and clinicopathologic features for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Southern China: a possible role of hepatitis B virus. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1258-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Uenishi T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Yamamoto T, Yamazaki O, Kinoshita H. Clinicopathological factors predicting outcome after resection of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:969-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Asayama Y, Aishima S, Taguchi K, Sugimachi K, Matsuura S, Masuda K, Tsuneyoshi M. Coexpression of neural cell adhesion molecules and bcl-2 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma originated from viral hepatitis: relationship to atypical reactive bile ductule. Pathol Int. 2002;52:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Rezaee-Zavareh MS S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM