Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2483

Peer-review started: July 31, 2014

First decision: August 15, 2014

Revised: September 14, 2014

Accepted: November 30, 2014

Article in press: December 1, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 212 Days and 23.9 Hours

AIM: To investigate the efficacy of premedication with pronase, a proteolytic enzyme, in improving image quality during magnifying endoscopy.

METHODS: The study was of a blinded, randomized, prospective design. Patients were assigned to groups administered oral premedication of either pronase and simethicone (Group A) or simethicone alone (Group B). First, the gastric mucosal visibility grade (1-4) was determined during conventional endoscopy, and then a magnifying endoscopic examination was conducted. The quality of images obtained by magnifying endoscopy at the stomach and the esophagus was scored from 1 to 3, with a lower score indicating better visibility. The endoscopist used water flushes as needed to obtain satisfactory magnifying endoscopic views. The main study outcomes were the visibility scores during magnifying endoscopy and the number of water flushes.

RESULTS: A total of 144 patients were enrolled, and data from 143 patients (M:F = 90:53, mean age 57.5 years) were analyzed. The visibility score was significantly higher in the stomach following premedication with pronase (73% with a score of 1 in Group A vs 49% in Group B, P < 0.05), but there was no difference in the esophagus visibility scores (67% with a score of 1 in Group A vs 58% in Group B). Fewer water flushes [mean 0.7 ± 0.9 times (range: 0-3 times) in Group A vs 1.9 ± 1.5 times (range: 0-6 times) in Group B, P < 0.05] in the pronase premedication group did not affect the endoscopic procedure times [mean 766 s (range: 647-866 s) for Group A vs 760 s (range: 678-854 s) for Group B, P = 0.88]. The total gastric mucosal visibility score was also lower in Group A (4.9 ± 1.5 vs 8.3 ± 1.8 in Group B, P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: The addition of pronase to simethicone premedication resulted in clearer images during magnifying endoscopy and reduced the need for water flushes.

Core tip: Magnifying endoscopy is typically used to detect and diagnose small upper gastrointestinal tract cancers. Premedication with the proteolytic enzyme pronase improved the quality of magnified endoscopic images and required fewer water flushes to achieve satisfactory endoscopic viewing. It is unclear if the use of pronase will influence cancer detection rates or patient outcomes. However, pronase can be considered as a method of maximizing the diagnostic efficacy of high-resolution endoscopic techniques.

- Citation: Kim GH, Cho YK, Cha JM, Lee SY, Chung IK. Effect of pronase as mucolytic agent on imaging quality of magnifying endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(8): 2483-2489

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i8/2483.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2483

Narrow-band imaging (NBI) is an endoscopic imaging technique that enhances the visualization of microvascular architecture and the structure of the superficial mucosa[1-3]. Magnifying endoscopy with NBI has the capacity to visualize the microvascular and microsurface patterns of gastric mucosal lesions. Recent studies suggest that magnifying endoscopy with NBI has high accuracy in the diagnoses of early gastric cancer, gastric intestinal metaplasia and corpus gastritis[4-6]. Specifically, the microvascular pattern observed during magnifying endoscopy with NBI is clinically useful in distinguishing gastric cancerous from noncancerous lesions. Mucosal visibility during diagnostic endoscopy is paramount in detecting subtle mucosal abnormalities associated with early neoplasia. Mucosal visibility is especially important during magnifying endoscopy due to the time consuming and complicated nature of the procedure, which includes preparation with mucolytic agents, dye spraying and irrigation of the mucosal surface[7-10].

Pronase, a mixture of proteolytic enzymes, was isolated in 1962 from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces griseus, which was used as a raw material in the preparation of anti-inflammatory and digestive enzymes. Pronase has previously been used as a premedication to reduce mucus during radiographic upper gastrointestinal examination[11-13]. Gastric mucus disturbs the spraying of dye onto the gastric mucosa and is a frequent artifact source during endoscopic imaging. Several studies report that premedication with pronase improves endoscopic visualization during conventional endoscopy, chromoendoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)[14-16].

We investigated the efficacy of premedication with pronase in improving mucosal visibility and procedure times during magnifying endoscopy.

This study was designed as a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double blind study. Patients were enrolled at two hospitals. Patients between the ages of 18 to 70 years who were scheduled for upper gastrointestinal (GI) magnifying endoscopy or EUS with a diagnosis of upper GI tumor were enrolled. Patients with a history of gastrectomy, esophagectomy, stricture or active bleeding in the upper GI tract were excluded. Patients with a history of upper GI surgery, who had gastric malignancy or gastrointestinal bleeding or who were pregnant during the study period were also excluded from the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Catholic University of Korea and Pusan National University. Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to each procedure.

We planned to enroll the patients competitively in two hospitals. A random number was assigned in each hospital. Enrolled patients were randomly assigned to either the simethicone plus pronase group (Group A) or the simethicone alone group (Group B). Group A received 80 mg simethicone, 1 g sodium bicarbonate, and 20000 units pronase (Endonase, Pharmbio Korea, Seoul, South Korea) plus distilled water to 100 mL. Group B received 20 mL solution containing 80 mg simethicone.

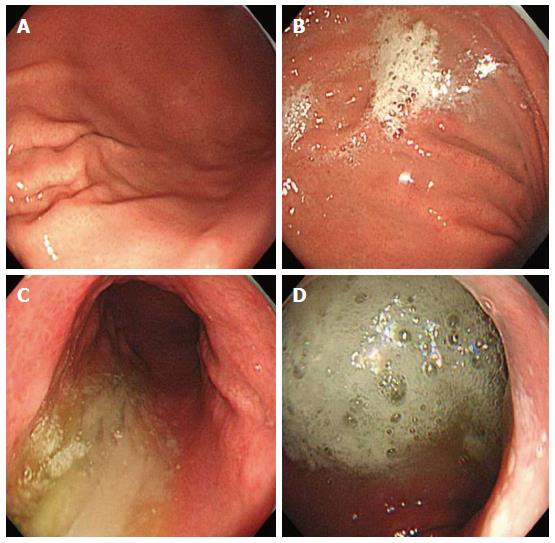

Study endoscopists were blinded to the premedication solution. The premedication solution was administered approximately 10 min before the start of the procedure, and each patient was asked to lie on their back then on their left and right sides. This position change was repeated five times before the patients underwent endoscopy. The following instruments were used in this study: a magnifying endoscope capable of magnification × 80 (GIF H260Z; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), a standard videoendoscopy system (EVIS LUCERA; Olympus) and a NBI system (Olympus). Each patient received a routine upper gastrointestinal tract survey using a magnifying endoscopy by two experienced endoscopists. Following the removal of excess gastric solution, separate gastric mucosal visibility grades were assigned for the gastric antrum, lower gastric body, upper gastric body, and fundus by each endoscopist. Mucosal visibility grades ranged from 1 to 4 (1, no adherent mucus; 2, mild mucus not obscuring vision; 3, a large amount of mucus obscuring vision and requiring < 30 mL water to clear; and 4, heavy adherent mucus requiring > 30 mL water to clear, Figure 1)[9]. We calculated the total gastric mucosal visibility grade by adding the scores from the four locations. To minimize bias within the scoring system, two experienced endoscopists, blinded to the premedication, assessed mucosal visibility scores. The mucosal visibility score at each of the four stomach locations was an average of the scores from the two endoscopists.

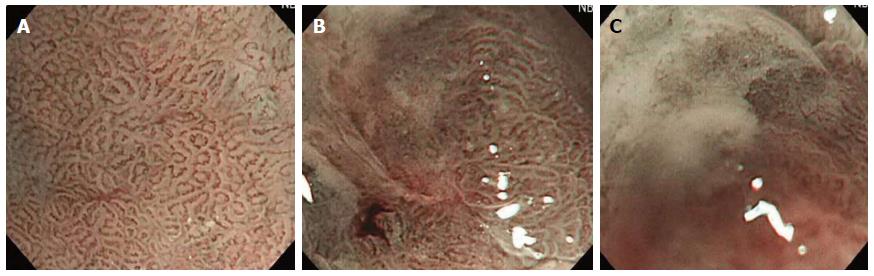

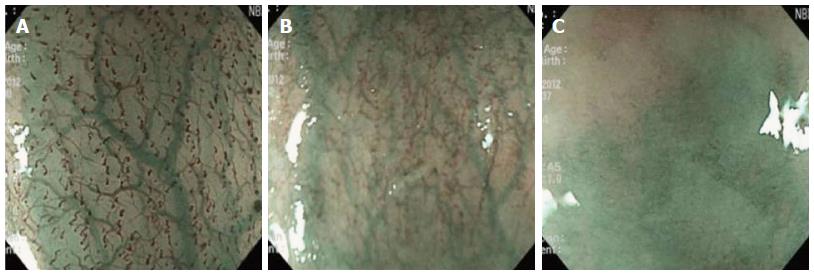

The quality of images obtained during magnifying endoscopy was expressed quantitatively as a visibility score. The visibility score was determined by the adherent mucus amount and the focus clarity and was scored from 1 to 3 as follows: 1, no adherent mucus with clear vision; 2, mild mucus not obscuring microvascularity; and 3, heavy adherent mucus obscuring microvascularity (Figures 2 and 3). For the esophagus, the score was an average of the scores in the mid and lower esophagus. For the stomach, scores were measured in the angle and lower body. The averaged scores became the esophageal and gastric mucosal visibility scores, respectively.

To produce a satisfactory view of stomach microvascularity during magnifying endoscopy, the endoscopist was free to use as many 30 mL water flushes as needed. Once all necessary flushes were performed, an extra photograph was taken of those areas. A record was kept of the total procedure time (from intubation to extubation) and the number of water flushes required.

Primary study parameters included the visibility score during magnifying endoscopy and the number of water flushes used. Secondary parameters included the mucosal visibility grade during conventional endoscopy and the total procedure time.

The sample size calculations indicated that 40 participants were required for each treatment group (80 patients overall) to detect esophageal mucosa with a visibility grade < 2 (large amount of mucus which would obscure vision), since pronase premedication was expected to decrease the mucosal visibility grade by 25%, and a power of 80%. Descriptive statistics for continuous data were calculated and reported as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were described using frequency distributions and were reported as percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Patient characteristics and gastric mucosal surface visibility scores were assessed using a χ2 test or one-way ANOVA. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

From June 2012 through October 2012, we randomly enrolled 144 patients with a diagnosis of early stage esophageal or stomach tumor who were scheduled for EUS or endoscopy. Patient diagnoses included esophageal or gastric submucosal tumor, early or gastric cancer, gastric adenoma and gastric maltoma. One patient was excluded from the study because of remnant food in his stomach at the time of endoscopy. Therefore, the results from 143 patients were available for analysis. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups in terms of age, gender, location of lesion or indication for the procedure.

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B |

| n | 71 | 72 |

| Age (yr) | 57.5 | 60.2 |

| Gender (M:F) | 44:27 | 46:26 |

| Indication | ||

| Early esophageal cancer | 3 | 1 |

| Early gastric cancer. | 39 | 36 |

| Gastric adenoma | 10 | 15 |

| Gastric maltoma | 3 | 1 |

| Gastric/duodenal subepithelial lesion | 14 | 14 |

| Gastric polyp or erosion | 3 | 4 |

| Location of lesion | ||

| Esophagus | 3 | 1 |

| Gastric cardia | 0 | 1 |

| Stomach upper body | 13 | 8 |

| Stomach midbody | 0 | 1 |

| Stomach lower body | 17 | 19 |

| Gastric angle | 7 | 14 |

| Gastric antrum | 32 | 27 |

The visibility score during magnifying endoscopy of the stomach was 1 in 73% of patients in Group A (pronase group) and 49% in Group B. In the esophagus, 67% of Group A and 58% of Group B patients had a visibility score of 1. The visibility score in the stomach was significantly improved in Group A (median visibility score 1 in group A vs 2 in Group B, P < 0.01), but there was no difference in visibility scores in the esophagus between the groups (Table 2).

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

| Stomach | |||

| G1 | 52 (73) | 35 (48.6) | < 0.01 |

| G2 | 16 (23) | 27 (37.5) | |

| G3 | 3 (4) | 10 (14) | |

| Esophagus | |||

| G1 | 48 (67.6) | 42 (58.3) | < 0.01 |

| G2 | 17 (23.9) | 18 (25) | |

| G3 | 6 (8.4) | 12 (16.7) | |

| Number of water flush | |||

| Mean (median, range) | 0.7 ± 0.9 (0, 0-3) | 1.9 ± 1.5 (1, 0-6) | < 0.01 |

| 0-1 | 57 (80) | 38 (53) | |

| 2-3 | 14 (20) | 28 (39) | |

| 4-6 | 0 | 6 (8) | |

| Time taken to be completed examination (s), median (25%-75%) | 766 (647-866) | 760 (678-854) | 0.87 |

The median number of 30 mL water flushed needed for satisfactory observation of the stomach microvascularity was 0 (range: 0-3) in Group A and 1 (range: 0-6) in Group B. Fewer flushes were used during the procedures done in patients of Group A, who received pronase, than in Group B (P < 0.05). However, all patients in Group A and 92% of patients in Group B required less than four water flushes to obtain clear images. Reducing the number of water flushes did not result in decreased endoscopy procedure time (Table 2).

There were significant differences in gastric mucosal visibility grades in all four stomach locations, especially in the fundus and upper body (Table 3).

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

| Fundus | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | < 0.01 |

| Upper body | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | < 0.01 |

| Lower body | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | < 0.01 |

| Antrum | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | < 0.01 |

| Total | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | < 0.01 |

There were no complications in either group. In particular, there were no clinically detectable cases of pulmonary aspiration.

Clear mucosal visibility during upper GI endoscopy is necessary to identify small malignant lesions, particularly when using newer diagnostic methods, such as magnifying endoscopy. Clear mucosal visibility can reduce the need for additional manipulation, such as extra washings, and can shorten total procedure time. Foam and mucus within the stomach often obstruct endoscopic visibility. The use of bubble-bursting agents and mucolytics improved mucosal visibility in previous trials. Simethicone is a silicone-based non-absorbable material that causes gas bubbles to burst by reducing their surface tension[17,18]. Mucolytic agents, such as N-acetyl cysteine or pronase, disrupt the surface mucosal gel layer of the stomach and, in some countries, are commonly used as a premedication in combination with simethicone[19-21]. In Japan, mucous-clearing medication is a standard pretreatment for endoscopy[22]. Pronase is commonly used to digest esophageal mucus before chromoendoscopy using methylene blue to detect Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer.

In this study we investigated the effect of pronase premedication on image clarity during magnifying endoscopy. The addition of pronase to a simethicone premedication mixture resulted in an effective pretreatment that improved mucosal visibility during magnifying endoscopy of the stomach and reduced the number of water flushes needed to clear the mucosa. However, premedication with pronase did not decrease the total procedure time. Endoscopic examination lasted an average of 10 min, and therefore the relatively short time needed to flush water did not impact the total procedure time. In addition, the median number of 30-mL water flushes was 0 in Group A and 1 in Group B. This indicated that the microsurface of the mucosa can be observed in more than half of all patients requiring either no or only one 30-mL water flush. The difference in the number of water flushes used between the two treatment groups was due to the 8% of patients in the simethicone-only group (Group B) who needed additional water flushes. This may not be a clinically significant difference.

The visual field in the esophagus is narrower than that in the stomach due to its smaller caliber. Therefore, it may be easier to obtain high resolution images in the esophagus than in the stomach. Additionally, there is usually less foam covering the esophageal mucosa than the stomach mucosa. These differences may explain why there was no difference in visibility scores between the treatment groups in the esophagus.

The ability to focus on a lesion is necessary to obtain optimal visibility during magnifying endoscopy. The clearing of mucus may be less important than focus when using a high resolution, high quality endoscope. The purpose of this study was to determine if clearing mucus by premedication with pronase prior to high resolution endoscopy would produce a significant effect and warrant a change in clinical practice. It is possible that the clinical advantage of mucolytics observed using conventional endoscopy, where stomach visibility can be largely influenced by mucus and foam, does not translate to magnifying endoscopy. In addition to the mucosal clearing effect of pronase, medication cost, patient compliance and ease of premedication preparation for clinical use should also be considered[23]. There were no issues with safety and patient compliance in the present study, but it may be inconvenient to maintain maximal mucolysis by mixing sodium bicarbonate.

The addition of pronase during premedication produced clearer endoscopic views during conventional endoscopy, similar to previous studies. The greatest difference in mucosal visibility grades during conventional endoscopy was observed in the fundus and upper body of the stomach. Endoscopists must carefully observe the high body of the stomach, because it has the lowest mucosal visibility off all groups. With or without mucolytic agents, endoscopic visibility depends on premedication, the volume of the premedication solution, optimal timing and optimal administration. This has been demonstrated in multiple studies. Woo et al[24] reported that optimal visibility is achieved 10-30 min prior to the endoscopic procedure. Lee et al[25] assessed the effect of a 100-mL liquid premedication of dimethylpolysiloxane, pronase, and sodium bicarbonate 10 or 20 min prior to endoscopy[25,26].

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, this trial was conducted at two centers with data collected by two endoscopists. Therefore, intra-observer variability may exist. To minimize this limitation, frequent study meetings were held where the endoscopists were provided with standardized images to aid in the assessment of gastric mucosal visibility grades. In addition, the same numbers of group A and group B patients were enrolled at each hospital. When we reanalyzed the data separately for each hospital, the results were similar to the combined results. The only large difference was in procedure time, which can depend on the endoscopist. We expressed procedure time as the median value. Second, the three-grade scoring system used to evaluate the quality of magnifying endoscopic images (visibility score) has not been validated; this scoring system could potentially over- or underestimate the visibility of the mucosa microsurface. To overcome this limitation, the number of water flushes was measured as an additional parameter required for satisfactory viewing during magnifying endoscopy. Third, endoscopic flushing of the lesion during magnifying observation is a better method to confine its effect on magnifying endoscopy. However, we used pre-endoscopic drinking after considering a previous report[22] that endoscopic flushing of mucolytics to the targeted area was not as effective as pre-endoscopic drinking. Therefore, it is possible that its effect on conventional observation could reach that of magnifying observation, even though most of the flushed water was suctioned before switching to magnifying observation.

In conclusion, premedication with the proteolytic enzyme pronase improved the quality of magnifying endoscopic images and required fewer water flushes to achieve satisfactory endoscopic viewing. Magnifying endoscopy is typically used to detect and diagnose small upper GI tract cancers, and it is unclear if the use of pronase will influence cancer detection rates or patient outcomes. However, pronase can be considered as a method to maximize the diagnostic efficacy of high resolution endoscopic techniques.

Mucosal visibility during diagnostic endoscopy is paramount in detecting subtle mucosal abnormalities associated with early neoplasia. Mucosal visibility is especially important during magnifying endoscopy due to the time-consuming and complicated nature of the procedure, which includes preparation with mucolytic agents, dye spraying, and irrigation of the mucosal surface.

Pronase, a mixture of proteolytic enzymes, has previously been used as a premedication to reduce mucus during endoscopic examinations. Several studies report that premedication with pronase improves endoscopic visualization during conventional endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasonography. Data regarding the efficacy of pronase in visualization during magnifying endoscopy are lacking.

The addition of pronase to simethicone premedication resulted in clearer images during magnifying endoscopy as well as conventional endoscopy. It also reduced the need for water flushes for a satisfactory view most effectively during magnifying endoscopy.

Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI) has the capacity to visualize the microvascular and microsurface patterns of the mucosa. It is typically used to detect and diagnose small intestinal metaplasia, premalignant lesions, and cancer of the esophagus and stomach. It is unclear if the use of pronase will influence cancer detection rates or patient outcomes. However, pronase can be considered a method of maximizing the diagnostic efficacy of high-resolution endoscopic techniques.

A NBI system uses an image-based diagnostic technique in which narrowing of the band of an optical filter in a frame-sequential type electronic endoscope is achieved by shifting the band to the short wavelength side and by reducing the invasion depth of light in the living body. The NBI system can be used to examine microvascular architecture and the structure of the superficial mucosa.

The paper is well-written, the tables and figures are of high quality, and the study is a well-designed randomized controlled trial. There may be controversy in terms of intra-observer variation considering that it is a multicenter trial, but the authors attempted to minimize this. The results are presented clearly.

| 1. | Li HY, Dai J, Xue HB, Zhao YJ, Chen XY, Gao YJ, Song Y, Ge ZZ, Li XB. Application of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging in diagnosing gastric lesions: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1124-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Uedo N, Ishihara R, Iishi H, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, Yamada T, Imanaka K, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishiguro S. A new method of diagnosing gastric intestinal metaplasia: narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:819-824. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Singh R, Lee SY, Vijay N, Sharma P, Uedo N. Update on narrow band imaging in disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:144-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yao K, Iwashita A, Kikuchi Y, Yao T, Matsui T, Tanabe H, Nagahama T, Sou S. Novel zoom endoscopy technique for visualizing the microvascular architecture in gastric mucosa. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S23-S26. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yao K, Iwashita A, Tanabe H, Nagahama T, Matsui T, Ueki T, Sou S, Kikuchi Y, Yorioka M. Novel zoom endoscopy technique for diagnosis of small flat gastric cancer: a prospective, blind study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:869-878. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tahara T, Shibata T, Nakamura M, Okubo M, Yoshioka D, Arisawa T, Hirata I. The mucosal pattern in the non-neoplastic gastric mucosa by using magnifying narrow-band imaging endoscopy significantly correlates with gastric cancer risk. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:429-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujii T, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Hirasawa R, Uedo N, Hifumi K, Omori M. Effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during gastroendoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:382-387. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kuo CH, Sheu BS, Kao AW, Wu CH, Chuang CH. A defoaming agent should be used with pronase premedication to improve visibility in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2002;34:531-534. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chen MJ, Wang HY, Chang CW, Hu KC, Hung CY, Chen CJ, Shih SC. The add-on N-acetylcysteine is more effective than dimethicone alone to eliminate mucus during narrow-band imaging endoscopy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang WK, Yeh MK, Hsu HC, Chen HW, Hu MK. Efficacy of simethicone and N-acetylcysteine as premedication in improving visibility during upper endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:769-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McDonald GB, O’Leary R, Stratton C. Pre-endoscopic use of oral simethicone. Gastrointest Endosc. 1978;24:283. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Keeratichananont S, Sobhonslidsuk A, Kitiyakara T, Achalanan N, Soonthornpun S. The role of liquid simethicone in enhancing endoscopic visibility prior to esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): A prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93:892-897. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wu L, Cao Y, Liao C, Huang J, Gao F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of Simethicone for gastrointestinal endoscopic visibility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:227-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 14. | Sakai N, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Nakaizumi A. Pre-medication with pronase reduces artefacts during endoscopic ultrasonography. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:327-332. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Han JP, Hong SJ, Moon JH, Lee GH, Byun JM, Kim HJ, Choi HJ, Ko BM, Lee MS. Benefit of pronase in image quality during EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1230-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yiengpruksawan A, Lightdale CJ, Gerdes H, Botet JF. Mucolytic-antifoam solution for reduction of artifacts during endoscopic ultrasonography: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:543-546. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Bertoni G, Gumina C, Conigliaro R, Ricci E, Staffetti J, Mortilla MG, Pacchione D. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of oral liquid simethicone prior to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1992;24:268-270. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Banerjee B, Parker J, Waits W, Davis B. Effectiveness of preprocedure simethicone drink in improving visibility during esophagogastroduodenoscopy: a double-blind, randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:264-265. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Asl SM, Sivandzadeh GR. Efficacy of premedication with activated Dimethicone or N-acetylcysteine in improving visibility during upper endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4213-4217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chang CC, Chen SH, Lin CP, Hsieh CR, Lou HY, Suk FM, Pan S, Wu MS, Chen JN, Chen YF. Premedication with pronase or N-acetylcysteine improves visibility during gastroendoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:444-447. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Neale JR, James S, Callaghan J, Patel P. Premedication with N-acetylcysteine and simethicone improves mucosal visualization during gastroscopy: a randomized, controlled, endoscopist-blinded study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:778-783. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bhandari P, Green S, Hamanaka H, Nakajima T, Matsuda T, Saito Y, Oda I, Gotoda T. Use of Gascon and Pronase either as a pre-endoscopic drink or as targeted endoscopic flushes to improve visibility during gastroscopy: a prospective, randomized, controlled, blinded trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:357-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cha JM, Won KY, Chung IK, Kim GH, Lee SY, Cho YK. Effect of pronase premedication on narrow-band imaging endoscopy in patients with precancerous conditions of stomach. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2735-2741. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Woo JG, Kim TO, Kim HJ, Shin BC, Seo EH, Heo NY, Park J, Park SH, Yang SY, Moon YS. Determination of the optimal time for premedication with pronase, dimethylpolysiloxane, and sodium bicarbonate for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:389-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee GJ, Park SJ, Kim SJ, Kim HH, Park MI, Moon W. Effectiveness of Premedication with Pronase for Visualization of the Mucosa during Endoscopy: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:161-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Choi IJ. Gastric preparation for upper endoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:113-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Koulaouzidis A, Konishi K S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH